Strategic Economic Viability Analysis of Biomass Power Projects: Costs, Feasibility, and Future Outlook

This article provides a comprehensive economic viability analysis of biomass power generation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and technical professionals.

Strategic Economic Viability Analysis of Biomass Power Projects: Costs, Feasibility, and Future Outlook

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive economic viability analysis of biomass power generation, tailored for researchers, scientists, and technical professionals. It explores the foundational economic drivers and market trends fueling global growth, delves into core methodologies for financial feasibility assessment, and addresses critical challenges with actionable optimization strategies. By validating performance through comparative Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) benchmarks and environmental impact assessments, this analysis offers a robust framework for evaluating biomass as a sustainable and dispatchable renewable energy source, crucial for informed decision-making in energy research and project development.

The Economic Landscape and Drivers of Biomass Power

Global Market Trajectory and Policy Tailwinds

Biomass power generation has emerged as a critical component of the global renewable energy portfolio, offering a sustainable solution for electricity production while addressing waste management challenges. As governments and industries intensify their decarbonization efforts, biomass power presents a unique value proposition: dispatchable renewable energy that can complement variable sources like wind and solar. The global market for biomass power generation is on a steady growth trajectory, valued at US$90.8 billion in 2024 and projected to reach US$116.6 billion by 2030, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.3% [1] [2]. This analysis compares the economic and performance characteristics of biomass power against other renewable alternatives, providing researchers with a framework for evaluating its viability within the broader energy system.

Market Performance Comparison

The economic viability of biomass power projects is best understood through comparative analysis with other renewable energy technologies. The following tables summarize key performance metrics, market data, and regional growth patterns.

Table 1: Global Market Size and Growth Projections for Biomass Power (2024-2034)

| Market Segment | 2024 Benchmark | 2030 Projection | CAGR | Source/Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Power Generation | US$ 90.8 Billion | US$ 116.6 Billion | 4.3% | Research and Markets [1] |

| Biomass Electricity | US$ 55.43 Billion | US$ 72.78 Billion (2029) | 5.7% | The Business Research Company [3] |

| Biomass Power Market | US$ 141.29 Billion | US$ 251.60 Billion (2034) | 5.95% | Precedence Research [4] |

| Biomass Energy Generator | ~US$ 55,000 Million (2025) | N/A | 12.5% (2025-2033) | Market Report Analytics [5] |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Renewable Energy Attributes

| Performance Characteristic | Biomass Power | Solar PV | Wind Power | Hydropower |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dispatchability | High (Firm, dispatchable) | Low (Intermittent) | Low (Intermittent) | Medium-High (Often dispatchable) |

| Land Use Impact | Medium | High | Low-Medium | Very High |

| Feedstock Cost Volatility | Medium-High | None | None | None |

| Grid Services Value | High (Provides stability) | Low | Low | High |

| Waste Reduction Benefit | Yes (Waste-to-energy) | No | No | No |

| Technology Maturity | High | High | High | Very High |

Experimental & Analytical Protocols for Viability Assessment

For researchers evaluating the economic viability of biomass power, the following methodologies provide a framework for rigorous analysis.

Energy System Modeling for Biomass Allocation

- Objective: To determine the cost-optimal allocation of limited biomass resources across the energy system (power, heat, transport fuels, carbon source) to meet emissions targets [6].

- Protocol: Employ a sector-coupled energy system model (e.g., PyPSA-Eur-Sec) with high spatial and temporal resolution.

- Key Parameters:

- Model a full year with hourly time-steps to capture seasonal energy demand and variable renewable energy (VRE) generation patterns.

- Incorporate a comprehensive portfolio of biomass conversion technologies, including combustion, gasification, anaerobic digestion, and pathways combined with carbon capture (BECCUS) [6].

- Define system constraints, including CO2 emissions targets (e.g., net-zero, net-negative), carbon sequestration capacity, and biomass feedstock availability (prioritizing residues and waste) [6].

- Conduct a near-optimal solution space analysis, accepting a small cost increase (e.g., 1-5%) above the cost-optimal solution to identify a diverse set of resilient technology pathways [6].

Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) for Project Feasibility

- Objective: To evaluate the financial viability and identify the cost drivers of a specific biomass power plant project [7].

- Protocol: Develop a detailed project model encompassing all capital and operational expenditures.

- Key Parameters:

- Capital Costs (CapEx): Model costs for land, site development, plant machinery (e.g., boilers, turbines, gasifiers), and infrastructure [7].

- Operational Costs (OpEx): Model costs for biomass feedstock (e.g., wood pellets, agricultural residues), transportation, utility consumption, and labor [7].

- Revenue Streams: Project income from electricity sales, renewable energy certificates (RECs), and by-products (e.g., heat in CHP systems, biochar) [1] [7].

- Financial Analysis: Calculate key viability metrics: Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE), Net Present Value (NPV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and payback period, incorporating the impact of government subsidies and carbon pricing [1] [7].

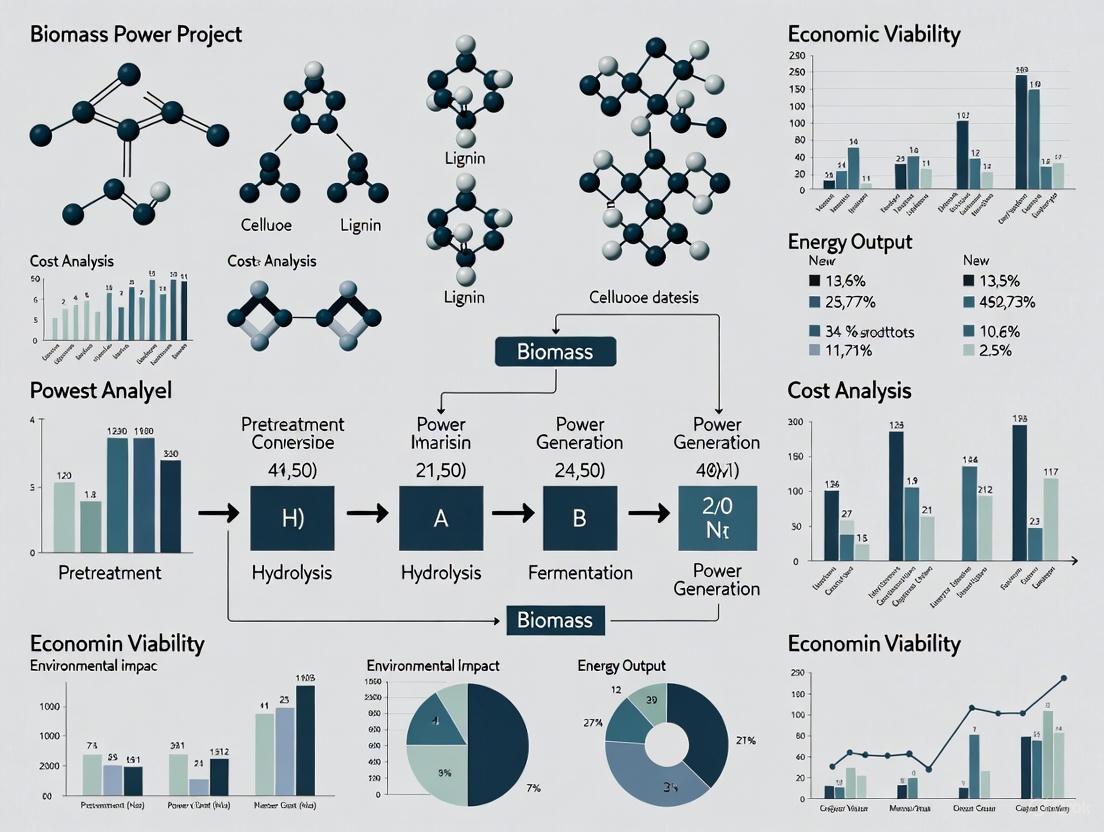

Visualizing Biomass Pathways and System Integration

The following diagrams illustrate the decision-making workflow for biomass allocation and its integrative role in a decarbonized energy system, based on energy modeling methodologies [6].

Diagram 1: Biomass utilization pathway decision workflow for maximizing economic and environmental value in a constrained system.

Diagram 2: The integrative role of biomass power in supporting a renewable-heavy electricity grid by providing dispatchable power and grid stability.

For scientists and development professionals conducting economic viability analysis, the following tools and data sources are essential.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions for Biomass Viability Analysis

| Tool/Solution | Function in Analysis | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Sector-Coupled Energy System Models | Models the interaction between power, heat, transport, and industrial sectors to find cost-optimal biomass use [6]. | Critical for understanding system-level value beyond standalone project economics. |

| Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) Software | Spreadsheet-based models to calculate LCOE, NPV, and IRR for specific project configurations [7]. | Sensitivity analysis on feedstock price and policy incentives is crucial. |

| Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) Databases | Quantifies the carbon footprint and environmental impact of different biomass feedstocks and conversion pathways. | Upstream emissions of biomass feedstock are a key sensitivity parameter [6]. |

| Policy & Subsidy Datasets | Data on feed-in tariffs, renewable energy credits, and carbon tax exemptions that impact project revenue [1] [3]. | A major growth driver; changes directly affect financial models. |

| Biomass Feedstock Cost Indices | Tracks price volatility of key feedstocks like wood pellets, agricultural residues, and municipal waste. | A primary source of financial risk and a key variable in OpEx modeling [7]. |

Regional Policy and Investment Landscape

Policy support and regional market dynamics are pivotal tailwinds for the biomass power sector.

- Europe: The largest market, with a 39% share in 2024 [4]. The EU's Green Deal and Climate Law, aiming for carbon neutrality by 2050, are key drivers. Policies like the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) in Germany provide financial incentives for decentralized biomass generation [4].

- North America: A significant market driven by the U.S. and Canada, supported by renewable portfolio standards and decarbonization mechanisms that incentivize utilities to use biomass as a reliable baseload energy source [4].

- Asia-Pacific: The fastest-growing region, with China as the dominant market. Growth is fueled by targets to address agricultural waste management and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060, supported by public-private partnerships and feed-in tariffs [4]. India is also a key growth market, with government subsidies for biogas plants and international collaborations to fund green energy projects [3] [4].

The comparative analysis confirms that biomass power holds a distinct, albeit complex, position in the renewable energy landscape. Its primary competitive advantage lies not merely in energy generation but in its multi-attribute value proposition: providing dispatchable renewable power, enabling negative emissions via BECCS, managing waste, and supplying renewable carbon for hard-to-electrify sectors [6]. The experimental protocols for energy system modeling and techno-economic analysis provide researchers with robust methodologies to quantify this value.

For scientists and developers, the critical research focus should be on optimizing the allocation of a limited biomass resource. As evidenced, system costs can increase by 20% if biomass is excluded from a net-negative emissions system [6]. Therefore, the economic viability of future biomass power projects will be maximized by integrating them with carbon capture technologies and strategically deploying them in sectors where alternatives are scarce and their system value is highest.

Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) Breakdown for Biomass Plants

Capital Expenditure (CAPEX) is a critical determinant in the economic viability of biomass power projects, representing the total investment required to achieve commercial operation. For biomass plants, this encompasses all costs associated with technology selection, plant construction, engineering, and commissioning before the facility generates revenue. Understanding the breakdown of these costs is essential for researchers and project developers conducting economic feasibility studies and for accurately modeling the financial performance of renewable energy investments.

The CAPEX for biomass power plants is influenced by multiple factors, including the chosen conversion technology, plant capacity, location, feedstock characteristics, and environmental compliance requirements. Biomass power generation utilizes organic materials such as wood chips, agricultural residues, and dedicated energy crops, converting them into electricity through various technological pathways including direct combustion, gasification, and anaerobic digestion. Each pathway carries distinct capital investment profiles and economic implications that must be carefully evaluated within the context of broader renewable energy portfolios and decarbonization strategies.

Comparative CAPEX Analysis of Biomass Technologies

Biomass power generation technologies convert organic feedstocks into electricity through different processes, each with unique capital cost structures. The most common technologies include:

- Direct Combustion: Biomass is burned to produce steam that drives a turbine generator. This is the most mature and widely deployed technology.

- Gasification: Biomass is converted into a synthetic gas (syngas) through a high-temperature process, which is then used to power engines or turbines.

- Anaerobic Digestion: Organic matter is broken down by microorganisms in the absence of oxygen to produce biogas, which is used for power generation.

- Cofiring: Biomass is combusted alongside coal in existing coal-fired power plants, requiring modifications to fuel handling and combustion systems.

Each technology offers different advantages in terms of efficiency, scalability, and environmental performance, with corresponding variations in capital investment requirements.

Comprehensive CAPEX Comparison Table

Table 1: Comparative CAPEX Breakdown for Biomass Power Technologies

| Technology Type | Total Plant Cost (USD/kW) | Construction & Engineering Share | Equipment Share | Key Cost Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dedicated Biomass Plant | $3,827 - $4,750 [8] [9] | 50-60% [9] | 20-30% | Plant scale, feedstock handling requirements, emission control systems |

| Direct Combustion | $2,500 - $3,500 [9] | 50-60% | 25-35% | Boiler technology, steam cycle parameters, fuel preparation systems |

| Gasification | 15-25% higher than direct combustion [9] | 45-55% | 30-40% | Gasifier type, gas cleaning systems, syngas utilization technology |

| Cofiring with Coal | $4,013 - $4,184 [8] | 40-50% | 20-30% | Existing plant configuration, biomass preparation systems, injection system modifications |

Table 2: CAPEX Range by Plant Capacity

| Plant Capacity | Total Capital Investment | Key Cost Components | Economies of Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Small-scale (1-5 MW) | $10 - $30 million [9] | Higher per-kW costs, simplified systems | Limited, higher specific cost ($5,000-8,000/kW) |

| Medium-scale (25-50 MW) | $125 - $237.5 million [9] | Balanced investment across systems | Moderate ($4,000-5,000/kW) |

| Utility-scale (50-100 MW) | $236.5 - $364 million [9] | Complex feedstock handling, advanced controls | Significant ($3,500-4,500/kW) |

The data reveals substantial variation in capital costs across different biomass power generation technologies. Dedicated biomass plants represent the baseline investment, with direct combustion systems typically at the lower end of the cost spectrum due to their technological maturity. Gasification technologies command a 15-25% premium over direct combustion systems, reflecting more complex equipment requirements and less mature commercialization status [9]. Cofiring applications demonstrate context-specific economics, with retrofit costs heavily dependent on the configuration and condition of existing coal plant infrastructure.

CAPEX Component Breakdown and Allocation

Detailed Capital Cost Categorization

Table 3: Detailed CAPEX Component Breakdown for a 50 MW Biomass Plant

| CAPEX Component | Investment Range | Percentage of Total CAPEX | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Construction & Engineering | $125 - $175 million [9] | 50-60% | Site conditions, local labor costs, engineering complexity |

| Biomass Conversion Equipment | $100 - $140 million [9] | 20-30% | Technology selection (combustion vs. gasification), plant capacity |

| Land & Site Preparation | $1 - $5 million [9] | 1-2% | Site location, topography, previous land use |

| Grid Interconnection & Transmission | $2 - $15 million [9] | 3-8% | Distance to grid, required upgrades, interconnection studies |

| Feedstock Supply Infrastructure | $2 - $10 million [9] | 2-5% | Feedstock type, transportation distance, storage requirements |

| Permitting, Licensing & Legal | $1.5 - $4 million [9] | 1-2% | Regulatory environment, community engagement requirements |

| Initial Working Capital | $5 - $15 million [9] | 3-6% | Pre-operational expenses, initial feedstock inventory |

The allocation of capital expenditure across different components reveals distinct patterns essential for financial planning and cost optimization strategies. Plant construction and engineering costs represent the largest share of total CAPEX (50-60%), encompassing civil works, structural engineering, and project management. Biomass conversion equipment constitutes the second major cost center (20-30%), with technology selection significantly influencing both the initial investment and long-term operational efficiency. Notably, grid interconnection costs demonstrate the highest variability relative to their proportion of total CAPEX, reflecting the site-specific nature of electrical infrastructure requirements.

Research Reagent Solutions for Techno-Economic Analysis

Table 4: Essential Analytical Tools for Biomass CAPEX Research

| Research Tool / Method | Application in CAPEX Analysis | Key Function |

|---|---|---|

| Aspen Plus Simulation | Process modeling and equipment sizing [10] | Models thermodynamic processes to optimize plant design and specify equipment requirements |

| Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) | Environmental impact quantification [11] | Evaluates environmental impacts across the entire lifecycle, informing technology selection |

| Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) | Integrated cost and performance assessment [10] | Combines technical and economic parameters to calculate financial metrics like NPV and IRR |

| Geographic Information Systems (GIS) | Spatial resource and logistics planning [11] | Analyzes spatial distribution of biomass resources to optimize plant siting and logistics costs |

| Monte Carlo Simulation | Uncertainty and risk analysis [9] | Models financial risk by simulating impact of cost and performance uncertainties on project economics |

These research tools enable comprehensive assessment of biomass plant CAPEX through different methodological approaches. Aspen Plus provides high-fidelity process modeling capabilities essential for accurate equipment specification and costing. Life-cycle assessment methodologies integrate environmental externalities into economic decision-making, particularly relevant for projects targeting sustainability certifications or carbon credits. Techno-economic analysis frameworks combine process modeling with financial analysis to generate holistic viability assessments, while GIS-based approaches optimize one of the most variable CAPEX components: feedstock logistics and related infrastructure.

Methodological Framework for CAPEX Assessment

Experimental Protocol for Techno-Economic Analysis

The methodological approach for comprehensive CAPEX assessment of biomass power plants involves a structured multi-stage process:

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

- Define functional unit (typically $/kW or $/annual MWh) and system boundaries

- Establish spatial and temporal parameters for the assessment

- Identify target financial metrics (NPV, IRR, payback period)

Phase 2: Inventory Analysis

- Collect primary data on equipment costs, labor rates, and material prices

- Compile secondary data from literature, databases, and equipment suppliers

- Document all cost assumptions, sources, and estimation methodologies

Phase 3: Cost Modeling

- Develop process flow diagrams and equipment lists

- Apply scaling factors for different plant capacities

- Calculate total installed costs using factored estimation methods

Phase 4: Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis

- Identify key cost drivers and performance parameters

- Perform sensitivity analysis on critical variables (e.g., feedstock costs, capacity factors)

- Conduct Monte Carlo simulations to quantify financial risk

This experimental protocol enables systematic comparison of different biomass technology configurations and provides a standardized framework for evaluating the economic viability of proposed projects. The methodology emphasizes transparency in assumptions, comprehensive boundary definition, and rigorous treatment of uncertainty—all essential elements for research-quality CAPEX assessment.

CAPEX Assessment Workflow Diagram

Biomass CAPEX Assessment Workflow

The methodology for biomass plant CAPEX assessment follows a structured four-phase approach that progresses from initial scoping through detailed analysis. The workflow begins with clear definition of assessment parameters and financial metrics, proceeds through systematic data collection and cost modeling, and culminates in comprehensive uncertainty analysis. This rigorous methodological framework ensures consistent, comparable results across different technology options and plant configurations, providing researchers with a standardized approach for economic viability assessment of biomass power projects.

Regional and Temporal Variations in CAPEX

Geographic Influences on Capital Costs

Capital expenditures for biomass plants exhibit significant regional variation due to differences in labor costs, regulatory requirements, infrastructure availability, and local material prices. Research by [11] demonstrates that development suitability indexes—incorporating factors such as biomass resource availability, electricity consumption patterns, and air quality compliance rates—significantly influence the optimal technology selection and associated capital costs across different regions.

Areas with abundant biomass resources and established agricultural or forestry industries typically benefit from lower feedstock-related infrastructure costs. Regions with stringent air quality regulations may require additional emissions control systems, increasing capital expenditures. The proximity to grid interconnection points and the capacity of existing electrical infrastructure also substantially impact balance of plant costs, which can vary by 20-30% depending on location-specific factors.

Temporal Trends and Future Projections

Biomass power CAPEX has demonstrated relative stability compared to other renewable technologies like solar and wind, though gradual efficiency improvements and standardization of project development processes have yielded modest cost reductions. The maturity of core conversion technologies like direct combustion limits the potential for dramatic cost reductions, though emerging technologies such as advanced gasification and integrated biorefineries continue to evolve.

Future capital cost trajectories are influenced by competing factors: standardization and learning effects may reduce costs, while increasingly stringent environmental regulations and carbon capture integration may increase capital requirements. Research into calcium looping (CaL) and other carbon capture technologies indicates potential for efficient integration with biomass power plants, though with associated increases in capital intensity [10]. The economic viability of such advanced configurations will depend on both technological progress and carbon policy frameworks.

The comprehensive analysis of capital expenditure breakdown for biomass power plants reveals several critical insights for researchers and project developers. First, the substantial upfront investment required—typically ranging from $3,800 to $4,750 per kW for dedicated plants—positions biomass as a capital-intensive renewable energy option [8] [9]. Second, the distribution of costs across major components shows consistent patterns, with plant construction and engineering representing the largest share (50-60%) of total CAPEX, followed by biomass conversion equipment (20-30%).

The methodological framework presented enables standardized assessment and comparison of different biomass technology configurations, incorporating both conventional financial metrics and emerging considerations such as carbon capture integration. For researchers pursuing economic viability analysis of biomass power projects, these findings highlight the importance of context-specific assessment that accounts for regional resource availability, policy frameworks, and technology readiness levels. Future research directions should focus on optimizing capital efficiency through modular designs, exploring integrated biorefinery concepts that diversify revenue streams, and developing advanced carbon capture configurations that enhance environmental performance without prohibitive cost increases.

Core Revenue Streams and Profitability Indicators

For researchers and scientists analyzing the economic viability of energy projects, biomass power generation presents a complex case study in renewable energy economics. The economic profile of a biomass power plant is multifaceted, shaped by a combination of traditional energy revenue, environmental commodity markets, and significant operational cost structures [12]. Understanding the core revenue streams and precise profitability indicators is fundamental for accurate economic modeling and comparative assessment against other renewable and conventional energy technologies.

This guide provides a systematic comparison of biomass power economics, detailing primary revenue sources, essential financial and operational key performance indicators (KPIs), and standardized methodologies for their experimental determination. The analysis is contextualized within the broader framework of economic viability research for energy infrastructure projects.

Core Revenue Streams

The revenue architecture for a biomass power plant is diversified beyond simple energy sales. The following table summarizes the primary revenue streams and their characteristics, which must be collectively modeled for a comprehensive economic assessment.

Table 1: Core Revenue Streams for Biomass Power Plants

| Revenue Stream | Description | Key Market Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity Sales | Revenue from selling generated power to the grid or through direct contracts [12]. | Sold via long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) or wholesale spot markets. PPA prices typically range from $70–$120/MWh [12]. Spot market sales can be strategic during peak demand, with prices potentially exceeding $200/MWh [12]. |

| Byproduct Sales | Income from selling process residues and co-products [12]. | Includes ash (for construction or agriculture) and steam/hot water for district heating or industrial processes (in Combined Heat and Power configurations). Biochar can command $100–$500 per ton [12]. |

| Environmental Credits | Revenue from policies that create market value for renewable energy's environmental attributes [12]. | Includes Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) and Carbon Credits/Offsets. Carbon credit prices vary significantly ($15–$50 per metric ton of CO₂), with a typical 50 MW plant potentially generating $1–3 million annually [12]. |

| Government Incentives | Direct subsidies, tax credits, or favorable tariff schemes designed to support renewable energy deployment [12] [2]. | Examples include the federal Production Tax Credit (PTC) in the U.S. and feed-in tariffs [12] [13]. These are often crucial for initial project viability. |

Profitability Indicators and Experimental Assessment

A robust economic viability analysis relies on a set of standardized profitability indicators, categorized here as financial and operational. The experimental protocols for determining these indicators are critical for ensuring comparability across studies.

Financial Indicators

Financial KPIs evaluate the overarching economic performance and attractiveness of a biomass power project to investors and lenders.

Table 2: Key Financial Profitability Indicators

| Indicator | Description | Experimental Calculation & Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) | The average net present cost of electricity generation over the plant's lifetime [12] [14]. | Calculation Protocol:1. Calculate the total lifetime cost (capital, fuel, O&M, financing).2. Calculate the total lifetime electricity generation (MWh).3. LCOE = Total Lifetime Cost / Total Lifetime Generation.Benchmark: $80–$150/MWh for biomass plants. A lower LCOE indicates higher competitiveness [12]. |

| Net Present Value (NPV) | The sum of the present values of all cash inflows and outflows over the project's life [14]. | Calculation Protocol:1. Project annual free cash flows (Revenue - Operating Costs - Taxes - Capital Expenditures).2. Determine the discount rate (Weighted Average Cost of Capital - WACC).3. NPV = Σ [Cash Flowₜ / (1 + discount rate)ᵗ] - Initial Investment.Benchmark: A positive NPV indicates a profitable project that meets or exceeds the required rate of return [14]. |

| Internal Rate of Return (IRR) | The discount rate that makes the NPV of all cash flows from a project equal to zero [12] [14]. | Calculation Protocol: Found iteratively by solving for "r" in: 0 = Σ [Cash Flowₜ / (1 + r)ᵗ] - Initial Investment. It is typically calculated using financial software or solver functions.Benchmark: A projected IRR of 10–15% is often critical for attracting capital. The project is viable if IRR exceeds the WACC [12]. |

| Net Profit Margin | The percentage of revenue remaining after all operating expenses, interest, taxes, and preferred stock dividends have been deducted [12]. | Calculation Protocol: Net Profit Margin = (Net Profit / Total Revenue) x 100%.Benchmark: Well-managed biomass facilities target net profit margins of 8% to 15% [12]. |

| Operating Expense Ratio (OER) | A measure of operational efficiency, comparing operating expenses to revenue [12]. | Calculation Protocol: OER = (Operating Expenses / Total Revenue) x 100%.Benchmark: An OER below 80% is considered healthy, indicating effective cost control relative to income [12]. |

Operational Indicators

Operational KPIs directly measure the plant's technical performance, which in turn drives financial results.

Table 3: Key Operational Profitability Indicators

| Indicator | Description | Experimental Calculation & Benchmark |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Availability Factor | The percentage of time the plant is physically available to generate electricity, regardless of market dispatch [12]. | Calculation Protocol: Availability Factor = (Total Hours in Period - Forced & Planned Outage Hours) / Total Hours in Period.Benchmark: Top-performing plants achieve rates >90%. Each percentage point of lost availability can represent over $300,000 in lost annual revenue for a 50 MW plant [12]. |

| Capacity Factor | The ratio of the plant's actual output over a period to its potential output if operated at full nameplate capacity continuously [12]. | Calculation Protocol: Capacity Factor = (Actual Energy Output over Period) / (Nameplate Capacity × Hours in Period).Benchmark: Biomass plants are valued for high capacity factors, typically 80% to 90%, significantly higher than intermittent sources like solar [12]. |

| Net Electrical Efficiency | The ratio of net electrical output to the total energy input from biomass fuel [12]. | Calculation Protocol: Net Efficiency = (Net Electrical Output (MWh) / Total Fuel Energy Input (MWh)) x 100%.Benchmark: Typical values range from 20–35%. Improving efficiency from 22% to 24% reduces fuel consumption by nearly 10%, directly cutting costs [12]. |

| Feedstock Cost per MWh | The cost of biomass fuel required to produce one unit of electricity [12]. | Calculation Protocol: Feedstock Cost per MWh = Total Feedstock Cost / Total Net Electricity Generated.Benchmark: Typically $40–$70/MWh. As fuel can constitute 40–60% of operating costs, this is a primary cost-control lever [12]. |

Advanced Economic Metrics

Progressive research is incorporating market dynamics into profitability analysis. The Profitability Factor is a novel metric that integrates hourly electricity market price data with a plant's generation profile to assess its true market competitiveness beyond the LCOE [15] [16]. This involves coupling techno-economic models with historical day-ahead market price series (e.g., from MIBEL) to simulate real-world trading revenues [16].

Diagram 1: Advanced Profitability Assessment Workflow.

Comparative Economic Analysis

Biomass vs. Other Generation Technologies

The economic competitiveness of biomass power is best understood in comparison with alternatives.

Table 4: Cross-Technology Economic Comparison

| Technology | Typical LCOE (USD/MWh) | Typical Capacity Factor | Key Economic Differentiators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Power | $80 - $150 [12] | 80% - 90% [12] | High capacity factor & dispatchability; high fuel cost share (40-60%); revenue diversification via byproducts/credits. |

| Solar PV | ~$40 - $60 (lower) | 15% - 25% [12] | Low variable costs; intermittent generation requires grid storage or backup, adding to system cost. |

| Wind Onshore | ~$30 - $60 (lower) | 25% - 45% (varies) | Low variable costs; highly intermittent; subject to specific site conditions. |

| Natural Gas (CCGT) | ~$40 - $80 (lower) | Varies with dispatch | Low capital cost, high fuel price volatility; emits CO₂, potentially facing carbon costs. |

| Coal (conventional) | ~$60 - $140 | High | Facing rising carbon prices and environmental regulations, increasing operating costs. |

Market Context and Profitability Challenges

Despite a favorable policy environment in many regions, the industry faces profitability challenges. The U.S. biomass power sector was estimated at $988.1 million in 2025, with revenue declining at a CAGR of 2.3% over the preceding five years, reflecting rising operational costs and competition from other renewables [13]. A mathematical modeling approach for forest biomass concluded that such plants can be unprofitable without strategic intervention, highlighting the impact of transportation costs and the need for supportive policies [17]. Conversely, a global market size of $141.29 billion in 2024 projected to grow to $251.60 billion by 2034 (CAGR of 5.95%) indicates underlying long-term growth potential driven by decarbonization efforts [4].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 5: Essential Analytical Tools and Data Sources for Economic Viability Research

| Tool / Data Source | Function in Analysis | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Techno-Economic Model (TEM) | Integrates technical performance parameters with cost data to calculate base-case economics (LCOE, NPV) [14]. | Modeling the impact of a 1% efficiency gain on the IRR of a 50 MW plant [12]. |

| Monte Carlo Simulation Software | Performs stochastic analysis to understand the impact of uncertainty in input variables (e.g., fuel cost, electricity price) on profitability metrics [16]. | Assessing the probability distribution of the Profitability Factor for a hybrid CSP-biomass plant under market price volatility [16]. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Database | Provides data on emissions and resource use for different biomass feedstocks and processes, essential for calculating carbon credit potential. | Quantifying the CO₂ savings from co-firing biomass with peat to model revenue from carbon credits [18]. |

| Electricity Market Price Datasets | Historical hourly or half-hourly price data from power exchanges (e.g., MIBEL, PJM, Nord Pool) [16]. | Used in advanced metrics like the Profitability Factor to simulate realistic trading revenues instead of relying on flat PPA rates [15]. |

| Financial Analysis Functions (NPV, IRR) | Standard functions in spreadsheet software (Excel, Google Sheets) or programming languages (Python, R) for core profitability calculations [14]. | Building a project finance model to determine the minimum PPA price required for a positive NPV. |

The economic viability of biomass power projects is fundamentally linked to the selection and management of feedstock sources. Feedstock economics encompasses the complete analysis of costs, from initial harvest or collection through transportation, storage, and eventual conversion to energy. Within the broader context of renewable energy development, understanding the economic trade-offs between different feedstock types—primarily agricultural residues and purpose-grown energy crops—is critical for researchers, project developers, and policymakers aiming to design sustainable and cost-effective bioenergy systems [19] [20]. The drive to reduce carbon emissions and enhance energy security has positioned biomass as a significant component of the global renewable energy landscape, with its market value projected to grow substantially in the coming decade [20].

The economic analysis of these feedstocks is not merely a comparison of purchase prices. It requires a holistic view of the entire supply chain, accounting for factors such as logistical complexity, seasonal availability, biomass quality, and opportunity costs related to land use. This guide provides a systematic, data-driven comparison of agricultural residues and energy crops, drawing on current techno-economic research and experimental data to inform the development of economically viable biomass power projects.

Biomass feedstocks are broadly categorized into waste streams, such as agricultural and forestry residues, and dedicated energy crops. Agricultural residues, including corn stover and wheat straw, are byproducts of existing food production systems. Their use for energy presents an opportunity to valorize waste, but their availability is inherently linked to primary crop production and they exhibit significant geographical and seasonal variation [21]. In contrast, energy crops, such as miscanthus, switchgrass, and short-rotation coppice (SRC) willow, are cultivated specifically for bioenergy production. These crops often provide higher and more reliable biomass yields but require dedicated land, incurring establishment costs and longer payback periods [22].

The biomass power generation market is on a robust growth trajectory, valued at an estimated $51.7 billion in 2025 and projected to reach $83 billion by 2033, registering a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.09% [20]. Another analysis focusing on the equipment market indicates even more aggressive growth, with a CAGR of 12.97% from 2026 to 2033 [23]. This expanding market is driven by global decarbonization efforts, supportive government policies, and technological advancements in conversion processes like gasification and anaerobic digestion [19] [20]. This growth underscores the importance of making informed, economically sound decisions regarding feedstock selection to ensure the long-term sustainability and profitability of biomass power projects.

Comparative Economic Analysis of Feedstocks

A detailed, quantitative comparison of key economic parameters is essential for evaluating the feasibility of different feedstocks. The following tables summarize critical data on costs, financial performance, and underlying characteristics.

Table 1: Direct Cost and Financial Comparison of Feedstocks

| Parameter | Agricultural Residues (e.g., Corn Stover) | Energy Crops (e.g., Miscanthus) | Energy Crops (e.g., Switchgrass) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Delivered Cost | $48 - $111 per ton [21] | $71 - $126 per ton (for switchgrass) [21] | Information Missing |

| Grower's Payment & Nutrient Replacement | $9 - $24 per ton [21] | Included in delivered cost | Information Missing |

| Annual Gross Margin | Not Typically Applicable | £382 per hectare (~$480 USD est.) [22] | £87 per hectare (~$109 USD est.) [22] |

| Payback Period | Not Typically Applicable | 2.93 - 3.75 years (for biogas systems) [24] | Information Missing |

| Key Economic Characteristic | Lower direct feedstock cost but high logistics cost | Higher feedstock cost, requires dedicated land and establishment time | Lower profitability vs. other land uses, more suitable for lower quality land [22] |

Table 2: Technical and Logistical Characteristics

| Characteristic | Agricultural Residues | Energy Crops |

|---|---|---|

| Harvest Window | Short, post-harvest of primary crop [21] | Flexible, often single annual harvest [21] |

| Bulk Density | Low, increasing transport costs [21] | Low, increasing transport costs [21] |

| Storage Losses (Dry Matter) | 5-7% (with tarp cover) [21] | Similar to agricultural residues |

| Primary Logistics Format | Large rectangular bales [21] | Large rectangular bales [21] |

| Supply Chain Maturity | Well-established in many regions | Emerging, requires new infrastructure and knowledge [22] |

| Compatibility with Co-firing | High, particularly solid biofuels [19] | High, can be processed into pellets [19] |

The data reveals a classic trade-off. Agricultural residues appear to have a lower direct cost, but their delivered cost is highly variable and can be significantly inflated by logistical challenges such as a short harvest window and low bulk density [21]. The nutrient replacement cost is a critical, often overlooked factor that compensates for the removal of soil nutrients when residues are collected.

Energy crops like miscanthus can offer better financial returns for the farmer on a per-hectare basis and a relatively fast payback period for conversion facilities, as shown in a Bangladeshi study of biogas systems [24] [22]. However, their establishment requires high upfront investment from growers, and income is delayed until the first harvest, which can be several years after planting, creating a significant cash flow barrier [22]. As the Scottish research notes, this financial risk and uncertainty about market demand are major hindrances to widespread adoption [22].

Experimental Assessment of Feedstock Performance

Beyond upfront costs, the performance of a feedstock in conversion processes is a major determinant of its overall economic value. Techno-economic analysis (TEA) and life-cycle assessment (LCA) are the primary methodologies used to evaluate this performance holistically.

Techno-Economic and Life-Cycle Analysis Protocols

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate and compare the economic viability and environmental sustainability of different biomass feedstocks for power generation, incorporating all steps from the field to final energy product.

Methodology:

- System Boundary Definition: The analysis must encompass the entire supply chain: feedstock cultivation/harvesting, collection, transportation, preprocessing, conversion (e.g., gasification, combustion), and distribution of power [21].

- Data Collection: Key parameters are gathered for the defined system boundary. This includes:

- Feedstock Yield: Tons per hectare per year [22].

- Feedstock Cost: Grower payment, nutrient replacement (for residues), and harvest cost [21].

- Logistics Cost: Baling, transportation, and storage costs [21].

- Conversion Performance: Efficiency, throughput, and product yield (e.g., syngas composition, electricity output) [25].

- Capital & Operating Costs: For the conversion facility [19].

- Environmental Flows: Greenhouse gas emissions from cultivation, transport, and conversion [25].

- Modeling and Analysis:

- Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA): A process model is developed to calculate the overall efficiency and the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE). The U.S. National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has demonstrated this approach, identifying forest residues and miscanthus as particularly cost-effective feedstocks for fuel production via gasification [25].

- Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA): The collected environmental data is used to calculate the total lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions, often compared to fossil fuel alternatives. The same NREL study found forest residues to be the most environmentally benign option [25].

Output: The primary outputs are the LCOE (in $/kWh) and the lifecycle GHG emissions (in g CO₂-eq/kWh), enabling a direct comparison of the economic and environmental performance of different feedstock options.

Gasification Performance Analysis Protocol

Objective: To experimentally determine the impact of different feedstock biochemical compositions on the yield and quality of syngas, a key intermediate for power and fuel production.

Methodology:

- Feedstock Selection and Preparation: Select diverse feedstocks representing varying levels of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. For example, wheat straw (high hemicellulose/lignin) and pine sawdust (high cellulose) [26]. Feedstocks are dried and milled to a consistent particle size.

- Bench-Scale Gasification: Gasification is performed in a controlled, bench-scale reactor (e.g., a fluidized bed or fixed-bed gasifier) under consistent operating conditions (temperature, gasifying agent like air, flow rate). As done in co-gasification studies, this can include both individual feedstocks and custom blends [26] [25].

- Product Analysis and Synergy Assessment:

- Syngas Analysis: The composition (vol% of H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, CnHm) of the produced syngas is analyzed using gas chromatography [26].

- Yield Quantification: The yields of solid char and liquid tar are measured gravimetrically.

- Synergy Identification: For blends, the experimental results are compared to a linear combination of the results from the individual components. Significant deviations indicate synergistic interactions, which can be positive (e.g., increased H₂ yield) or negative [26].

Output: Quantitative data on gas composition and product yields, providing insights into which feedstocks or blends are optimal for maximizing syngas quality and minimizing undesirable byproducts like tar. Research has shown that feedstocks with higher lignin content (e.g., wheat straw) can generate more hydrogen, while the type of plastic in co-gasification with biomass has a marginal effect compared to the biomass type itself [26].

Research Workflow for Feedstock Economic Viability

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental and analytical workflow for assessing feedstock viability, from initial selection to final recommendation.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental assessment of feedstocks relies on a suite of analytical tools and reagents. The following table details key items essential for conducting the protocols outlined in this guide.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Feedstock Analysis

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Determines the thermal stability and compositional breakdown (moisture, volatiles, fixed carbon, ash) of a feedstock sample under controlled temperature programs [26]. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Separates and quantifies the components of syngas produced from gasification experiments (e.g., H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) [26]. |

| Bench-Scale Fluidized Bed Gasifier | A small-scale reactor that simulates the gasification process, allowing for the study of feedstock conversion efficiency and product yields under controlled conditions [26] [27]. |

| Standard Biomass Components (Cellulose, Xylan, Lignin) | Pure reference materials used to deconvolute the complex reactions of real biomass during co-gasification and TGA, helping to identify synergistic effects [26]. |

| Bioenergy Feedstock Library | A curated repository (e.g., managed by INL) that provides data on the chemical and physical properties of diverse feedstocks, enabling researchers to understand variability and its impact on conversion [28]. |

| Integrated Biomass Supply Analysis and Logistics Model (IBSAL) | A modeling and simulation platform used to analyze the costs and energy inputs of the complete biomass supply chain, from harvest to biorefinery gate [21]. |

Discussion and Synthesis of Findings

The experimental and economic data converge on several key points. First, the biochemical composition of biomass (specifically the ratios of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin) directly influences conversion performance and product distribution, making it a critical parameter for selection beyond mere cost-per-ton [26]. Second, supply chain logistics often constitute a significant portion of the total delivered cost, particularly for low-density materials like agricultural residues [21]. This makes feedstock selection a deeply regional endeavor, where the optimal choice depends on local agricultural practices, available infrastructure, and transportation distances.

The economic promise of energy crops is tempered by significant non-economic barriers. A primary challenge is farmer and land-manager unfamiliarity with these crops and their associated risks, including uncertain market demand and the need for new skills and equipment [22]. Furthermore, the cash flow profile of energy crops, with high upfront costs and delayed revenue, is misaligned with traditional annual farming cycles, creating a adoption hurdle even when long-term gross margins appear favorable [22].

Therefore, the most economically viable biomass power projects will likely be those that strategically integrate multiple feedstock types to mitigate supply and price risk. For instance, a base supply of lower-cost agricultural residues can be supplemented with dedicated energy crops to ensure consistent annual throughput and to capitalize on the superior performance characteristics of specific feedstocks for a given conversion technology.

Financial Modeling and Feasibility Assessment Frameworks

For researchers and scientists engaged in the development of renewable energy technologies, assessing economic viability is a critical component of the research and development lifecycle. Two metrics form the cornerstone of this financial analysis: the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) and the Internal Rate of Return (IRR). Within the specific context of biomass power projects, these metrics enable an objective comparison of technological alternatives under consistent financial parameters. The LCOE represents the lifetime cost of energy production per unit, serving as a fundamental measure of competitiveness against other generation sources [29]. Conversely, the IRR calculates the projected percentage return on investment, providing a clear benchmark for investment attractiveness and capital allocation decisions [30] [31].

The application of these metrics is particularly salient for biomass power, where typical LCOE values range from $0.08 to $0.12 per kilowatt-hour (kWh) and target IRR hurdles for project investors often fall between 15% and 20% [30] [9]. A thorough grasp of both the calculation methodology and practical interpretation of these values is indispensable for research professionals aiming to translate technological innovation into commercially viable energy solutions.

Metric Comparison: LCOE vs. IRR

The following table provides a structured, side-by-side comparison of LCOE and IRR, detailing their core functions, formulas, and applications specific to energy project analysis.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of LCOE and IRR for Energy Projects

| Feature | Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) | Internal Rate of Return (IRR) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Function | Measures the lifetime cost of generating a unit of energy; used to compare cost-competitiveness of different technologies [29]. | Estimates the annualized percentage return generated by a project over its lifetime; used to assess investment attractiveness [31]. |

| Primary Question Answered | What is the minimum price per unit of electricity at which the project breaks even? | What is the projected compound annual growth rate of the invested capital? |

| Key Input Variables | Overnight capital cost, fixed & variable O&M costs, fuel cost, heat rate, capacity factor, project lifetime, discount rate [29]. | Initial investment cost, timing and magnitude of all future cash inflows and outflows [30]. |

| Interpretation Rule | A project is more cost-competitive when its LCOE is lower than that of alternatives or the market price. | A project is financially attractive if its IRR is higher than the investor's required hurdle rate (cost of capital) [31]. |

| Typical Range for Biomass | $0.08 - $0.12 /kWh [9] | Target of 15% - 20% for commercial projects [30]. |

| Key Strengths | Provides a simple, standardized cost metric for technology comparison. Facilitates assessment of grid parity. | Considers the time value of money and the entire cash flow profile. Allows for comparison against a clear financial benchmark. |

| Key Limitations | Does not account for revenue variations in electricity markets. Sensitive to assumed capacity factor and discount rate [15]. | Can be misleading for projects with unconventional cash flow timing. Does not indicate the absolute dollar value of the return [31]. |

Calculation Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Calculating the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE)

The standard methodology for calculating LCOE involves a discounted cash flow analysis, which aligns all costs and energy production over the project's lifetime to their present value. The most common formula, as documented by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), is [29]:

sLCOE = { (overnight capital cost * capital recovery factor + fixed O&M cost ) / (8760 * capacity factor) } + (fuel cost * heat rate) + variable O&M cost

The procedural workflow for this calculation is outlined below:

Diagram 1: LCOE Calculation Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Data Acquisition: Gather all required input data. Capital costs for a biomass power plant can range from $125 million to $175 million for a ~50 MW facility. Fixed O&M, variable O&M, and projected fuel costs must also be sourced from vendor quotes and market studies [9].

- Capital Recovery Factor (CRF) Calculation: Compute the CRF using the formula

CRF = [i(1+i)^n] / [(1+i)^n - 1], whereiis the real discount rate andnis the project economic life. This factor converts the present value of the capital cost into an equivalent annual expense [29]. - Annual Cost Calculation: Calculate the annualized capital cost by multiplying the overnight capital cost by the CRF. Add the annual fixed O&M cost to this value.

- Energy Production Calculation: Determine the annual energy output in kilowatt-hours (kWh) by multiplying the total hours in a year (8,760) by the plant's capacity factor.

- Levelization: The simple LCOE is calculated by dividing the total annualized costs (from Step 3) by the annual energy production (from Step 4), then adding the variable O&M and fuel costs, if not already included in the annualized figure [29].

Protocol for Calculating the Internal Rate of Return (IRR)

The IRR is the discount rate that makes the Net Present Value (NPV) of all cash flows from a project equal to zero. The formula is solved iteratively for the rate r [30] [31]:

0 = CF₀ + [CF₁ / (1 + r)] + [CF₂ / (1 + r)²] + ... + [CF_n / (1 + r)^n]

Where CF₀ is the initial investment (negative cash flow), and CF₁ to CF_n are the future cash flows (positive or negative).

The procedural workflow for this calculation is outlined below:

Diagram 2: IRR Calculation and Decision Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Cash Flow Projection: Construct a detailed, year-by-year projection of all cash inflows and outflows over the project's lifetime. For a biomass plant, outflows include the initial capital investment and ongoing operational expenses (e.g., feedstock, which can be 40-60% of operating costs). Inflows primarily consist of electricity sales revenue, often secured via a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA), and any renewable energy credits or other incentives [9].

- Equation Setup: The NPV equation is established with the projected cash flows, with the discount rate

ras the variable to be solved for. - Iterative Solving: The IRR is typically calculated using computational tools, as solving for

ralgebraically is complex. The most accurate method in spreadsheet software is the XIRR function, which accounts for the specific dates of each cash flow, unlike the IRR function which assumes regular periods [30]. - Decision Analysis: The calculated IRR is compared to the project's hurdle rate. If the IRR exceeds this minimum acceptable return, the project is considered financially viable.

Essential Research Toolkit for Economic Analysis

For researchers modeling the economics of biomass power projects, the following table lists key inputs and reagents required for robust LCOE and IRR analysis.

Table 2: Essential Inputs for Biomass Project Financial Modeling

| Research Input | Function in Economic Analysis | Typical Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Overnight Capital Cost | Represents the total capital expenditure required to construct the plant, excluding financing charges. Serves as the primary cost input for LCOE and the initial cash outflow for IRR. | Vendor quotes, engineering procurement and construction (EPC) contracts, literature databases (e.g., NREL reports). |

| Biomass Feedstock Cost | The cost of fuel, a major variable operating expense. Critical for both LCOE sensitivity analysis and projecting annual cash outflows for IRR. A 10% increase can reduce IRR by 15-25% [9]. | Local biomass supplier quotes, agricultural/forestry residue market studies, long-term supply contract templates. |

| Capacity Factor | Indicates the actual energy output as a fraction of its maximum potential. Directly impacts the denominator in the LCOE calculation and the annual revenue for IRR. | Performance data from pilot plants, technical simulation models, grid dispatch analysis. |

| Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) Price | The contracted price for sold electricity. The primary driver of cash inflows for IRR calculations and the key benchmark against which LCOE is compared for profitability. | Historical PPA data, utility tender results, market price forecasts. |

| Discount Rate / Hurdle Rate | Reflects the cost of capital and project risk. The central discounting factor in LCOE and the critical benchmark for IRR acceptability. | Corporate finance models, weighted average cost of capital (WACC) calculations, investor return expectations. |

| Government Incentive Data | Details on tax credits (e.g., Investment Tax Credit), grants, or premium tariffs. Can significantly improve both LCOE and IRR by reducing net costs or increasing revenues [9]. | Government energy agency publications, legal and regulatory databases. |

The concurrent application of LCOE and IRR provides a multi-dimensional view of a biomass power project's economic profile. While LCOE offers a pure measure of generation cost competitiveness, IRR delivers the decisive investment perspective by incorporating revenue and the time value of money. For researchers, a rigorous sensitivity analysis on key variables—particularly feedstock cost and PPA pricing—is non-negotiable. As the energy sector evolves, integrating these standard metrics with analysis of market price volatility, as seen in studies of CSP-biomass hybrids, represents the frontier of economic viability research [15]. Mastering these tools enables scientists and developers to not only advance technology but also to build the compelling financial cases necessary to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy.

The global push for renewable energy has significantly increased interest in biomass power generation, with the biomass power generation fuel market projected to grow from USD 1.01 billion in 2024 to USD 2.04 billion by 2031, exhibiting a compound annual growth rate of 10.7% [32]. Within this expanding market, three primary technological pathways—combustion, gasification, and anaerobic digestion—compete for economic and operational viability in converting organic materials into useful energy. Each technology represents a distinct approach with unique economic considerations, performance characteristics, and optimal application domains, making the selection process critical for researchers, project developers, and policy makers focused on sustainable energy solutions.

The economic analysis of biomass power projects requires a nuanced understanding of how these technologies perform across different feedstock types, operational scales, and energy output requirements. While government incentives such as production tax credits and renewable portfolio standards have supported biomass power producers, the industry faces challenges from rising operational costs and increasing competition from other renewable sources like wind and solar [13]. In this complex landscape, a comprehensive comparison of these three core technologies provides essential insights for strategic decision-making in biomass energy investments and research directions, particularly as technological advancements continue to reshape their economic profiles and performance parameters.

Fundamental Process Mechanisms

Combustion represents the most straightforward approach to biomass energy conversion, involving the direct burning of organic materials in a controlled environment to produce high-pressure steam that drives turbines for electricity generation. This direct-fired approach accounts for roughly half of all biomass energy production, with most biomass power plants utilizing this method [13]. The process typically operates at temperatures ranging from 800°C to 1000°C and involves complete oxidation of the biomass feedstock, resulting in the production of heat, carbon dioxide, and water vapor, along with ash residues that require appropriate disposal or utilization.

Gasification employs a thermochemical conversion process that heats biomass materials to high temperatures (typically 400-800°C) in a controlled, oxygen-limited environment [33] [34]. This partial oxidation process converts materials into a mixture of combustible gases known as syngas, primarily composed of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and carbon dioxide [33]. The resulting syngas is a versatile energy carrier that can be utilized for electricity generation in gas turbines or engines, converted into liquid fuels, or used as a chemical feedstock for industrial processes. This technology can process a broader range of feedstocks compared to anaerobic digestion, including biomass, coal, and municipal solid waste [33].

Anaerobic Digestion utilizes microbial processes to break down organic material in the absence of oxygen through a series of biochemical reactions including hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis [33]. This biological process occurs at relatively low temperatures (typically 37°C for mesophilic digestion) and produces biogas primarily composed of methane (50-60%) and carbon dioxide (40-50%), along with a nutrient-rich digestate that can be utilized as organic fertilizer [33] [35]. The process is particularly effective for high-moisture content organic wastes such as agricultural residues, food waste, and animal manure [33].

Technical Performance Comparison

Table 1: Technical Performance Parameters of Biomass Conversion Technologies

| Parameter | Combustion | Gasification | Anaerobic Digestion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Temperature | 800-1000°C | 400-800°C [34] | 37-55°C (mesophilic/thermophilic) [36] |

| Conversion Efficiency | 20-40% (electric) | 35-50% (electric, combined cycle) | 30-45% (biogas to electric) [35] |

| Primary Output | Steam, Electricity | Syngas (H₂, CO, CO₂) [33] | Biogas (CH₄, CO₂), Digestate [33] |

| Typical Capacity | 10-100 MW | 5-50 MW | 50 kW-10 MW |

| Feedstock Flexibility | Moderate | High [33] | Limited to organic wastes [33] |

| By-products | Ash, Flue gas | Slag, Tar | Digestate (fertilizer) [33] |

| Water Requirement | Low | Low | High (for maintaining moisture) |

Table 2: Economic Comparison of Biomass Conversion Technologies

| Economic Factor | Combustion | Gasification | Anaerobic Digestion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Cost ($/kW) | 2,000-3,500 | 2,500-4,000 | 3,000-5,000 (small scale) |

| Operational Costs | Moderate | Moderate-High | Low-Moderate |

| Feedstock Cost Sensitivity | High | Moderate | Low (often uses waste) |

| Technology Maturity | Commercial | Demonstration/Commercial | Commercial |

| Scale Dependence | Large scale preferred | Medium to large scale | Small to medium scale |

| Maintenance Requirements | Moderate | High (gas cleaning) | Low-Moderate |

Experimental data from recent studies demonstrates the performance variations among these technologies. Anaerobic digestion systems have shown biogas production rates of approximately 170 liters per day with methane content of 53% and a conversion efficiency of 84 kg of methane per ton of organic matter [35]. Temperature sensitivity analysis revealed that biogas production increases by 1.2 liters per hour for each additional 1°C internal temperature [35]. For gasification, research on digestate-derived chars shows that pyrolysis treatment (400-800°C) increased the calorific value of the material by 34.7%, effectively reclassifying the fuel from biomass to coal-grade [34]. Combustion performance varies significantly based on feedstock characteristics, with direct-fired systems facing challenges related to fuel consistency and emissions control.

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Anaerobic Digestion Experimental Protocol

Objective: To evaluate methane production potential from different feedstock mixtures and optimize process parameters for maximum biogas yield.

Materials and Methods: The experimental setup utilizes semi-continuous reactors operated under controlled conditions for extended periods (typically 30+ days). Feedstocks are prepared by mixing different organic substrates in varying ratios. A recent study examining co-digestion of Ulva lactuca (seaweed) and cow manure employed three different algae-to-manure ratios (1:1, 2:1, and 3:1) to assess synergistic effects [37]. The reactors are maintained at mesophilic temperatures (37°C) with regular feeding schedules and continuous monitoring of operational parameters.

Data Collection and Analysis: Biogas production volume is measured daily using gas meters, while composition (methane, CO₂, trace gases) is analyzed via gas chromatography. The kinetic evaluation of biogas production employs multiple mathematical models including first-order, logistic, transference, and modified Gompertz models to represent experimental data. In recent studies, the modified Gompertz model demonstrated the highest coefficient of determination (R² = 0.999), indicating excellent fit with experimental observations [37]. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is applied to determine the significance of factors such as fermentation time and substrate ratio on methane production.

Key Findings: Experimental results from co-digestion studies show that a 2:1 ratio of Ulva lactuca to cow manure achieved the maximum methane yield of 325.75 mL per g volatile solids [37]. Temperature optimization studies demonstrate that thermal insulation coupled with solar heating can increase biogas production by up to 69% in temperate climates, highlighting the critical importance of temperature management in anaerobic digestion systems [35].

Gasification Experimental Protocol

Objective: To characterize syngas production from different feedstocks and evaluate the impact of process parameters on gas quality and yield.

Materials and Methods: The experimental system consists of a gasification reactor, feedstock preparation and feeding system, gas cleaning units, and analytical instrumentation. Feedstocks are typically dried to reduce moisture content (improving efficiency) and sized to appropriate dimensions for consistent feeding. The process involves four key stages: drying (moisture removal), pyrolysis (thermal decomposition in absence of oxygen), combustion (partial oxidation to provide process heat), and reduction (chemical reactions producing syngas) [33].

Data Collection and Analysis: Syngas composition is continuously monitored using online gas analyzers to determine concentrations of H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, and other hydrocarbons. Gas heating value, production rate, and cold gas efficiency are calculated from this compositional data. Tar content in the syngas is measured using standardized sampling and analysis methods, as this parameter significantly impacts downstream applications.

Advanced Characterization: Researchers employ techniques such as Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), Raman Spectroscopy, and X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to analyze structural composition and surface properties of chars produced during gasification [34]. These analyses help understand the relationship between material properties and combustion behavior, providing insights for process optimization.

Combustion Characterization Experimental Protocol

Objective: To evaluate the combustion characteristics of different biomass fuels and their processed derivatives (chars) under controlled conditions.

Materials and Methods: Biomass samples are prepared through size reduction and drying to ensure consistent feeding. For char production, two main thermochemical treatment methods are employed: Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC) conducted at 200-260°C under subcritical water conditions, and pyrolysis performed at 400-800°C in an inert atmosphere [34]. The resulting chars are then subjected to comprehensive analysis including proximate analysis (volatile matter, fixed carbon, ash content) and ultimate analysis (C, H, O, N, S content).

Performance Testing: Combustion characteristics are evaluated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), where samples are heated under controlled conditions while monitoring mass loss and thermal behavior. Key parameters determined include ignition temperature, burnout temperature, maximum combustion rate, and comprehensive combustion performance index.

Key Findings: Research comparing hydrochar and pyrochar derived from biomass digestate shows significant differences in combustion behavior. Hydrochar exhibits higher content of oxygen (18.4-32.05%) and hydrogen (2.93-3.98%), along with greater abundance of active functional groups including sp², sp³ carbon, C-O, and C=O [34]. These characteristics contribute to enhanced combustion reactivity compared to pyrochar, which undergoes more extensive carbonization and loses reactive functional groups during high-temperature processing.

Visualization of Technology Processes

The diagram above illustrates the fundamental processes for each biomass conversion technology, highlighting the distinct pathways from raw biomass to final energy products. Combustion follows a direct thermochemical route, gasification employs staged thermochemical conversion, while anaerobic digestion utilizes a multi-stage biological approach.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Analytical Tools for Biomass Technology Evaluation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Digestion Inoculum | Microbial starter culture for biogas production | Acclimated mixed culture from operating digesters; Maintained at 37°C |

| Gas Standards | Calibration of gas analyzers for composition analysis | Certified mixtures of CH₄, CO₂, H₂, CO in N₂ balance; Various concentration ranges |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Combustion behavior characterization | Temperature range: RT-1000°C; Atmosphere: Air/N₂; Heating rate: 5-20°C/min |

| Gas Chromatograph | Biogas/Syngas composition analysis | TCD/FID detectors; Columns: Porapak Q, Molecular Sieve 5A |

| Salix Varieties | Dedicated energy crop for biogas/combustion | Commercial varieties: 'Björn', 'Tordis', 'Tora'; 2-5 year growth cycles [36] |

| SO₂ Catalyst | Steam explosion pretreatment | SO₂ concentration: 2-3% w/w; Temperature: 185°C; Time: 4 minutes [36] |

Economic Viability Analysis

The economic assessment of biomass conversion technologies must consider both capital and operational expenditures within the context of market conditions and policy frameworks. The U.S. biomass power industry has experienced challenges with revenue declining at a compound annual growth rate of 2.3% over the past five years to an estimated $988.1 million in 2025, despite government incentives such as production tax credits [13]. This underscores the importance of technology selection based on economic viability rather than technical feasibility alone.

Capital Investment Considerations: Combustion systems typically represent the lowest capital cost option at $2,000-3,500 per kW installed capacity, making them attractive for large-scale applications where feedstock costs are favorable. Gasification requires higher capital investment ($2,500-4,000 per kW) but offers greater feedstock flexibility and potentially higher efficiency in combined cycle configurations [33]. Anaerobic digestion systems command the highest specific capital costs ($3,000-5,000 per kW), particularly at smaller scales, but can achieve favorable economics when leveraging waste feedstocks with negative costs and producing multiple revenue streams from both energy and digestate [7].

Operational Economics: The economic performance of each technology is heavily influenced by feedstock availability and cost structures. Combustion systems are highly sensitive to feedstock costs, requiring low-cost biomass supplies to remain competitive. Gasification offers more flexibility in feedstock selection but faces challenges with operational complexity and maintenance requirements. Anaerobic digestion benefits from the ability to utilize high-moisture waste streams that may have negative costs (tipping fees), significantly improving economics [33]. Additionally, AD produces digestate that can be sold as organic fertilizer, creating a secondary revenue stream.

Scale Considerations: Technology economics vary significantly with project scale. Combustion technologies achieve optimal economics at larger scales (typically 10-100 MW), while anaerobic digestion remains viable at smaller scales (50 kW-10 MW), making it suitable for distributed energy applications and agricultural operations [35]. Gasification technologies occupy an intermediate position, with optimal scales typically between 5-50 MW.

The comparative analysis of combustion, gasification, and anaerobic digestion technologies reveals a complex landscape where no single solution dominates across all applications. Instead, the optimal technology selection depends on specific project conditions including feedstock characteristics, scale requirements, energy product preferences, and local economic factors. Combustion remains the most mature and widely implemented technology, particularly for large-scale power generation from woody biomass. Gasification offers superior feedstock flexibility and potential for higher efficiency applications but faces challenges related to operational complexity and syngas cleaning requirements. Anaerobic digestion provides an optimal pathway for high-moisture organic wastes, with the added benefits of nutrient management and continuous operation.

Future research should focus on hybrid systems that integrate multiple conversion technologies to maximize energy recovery and economic returns. As noted in recent analyses, "the future answer will undoubtedly be, for many wastes, to use both [anaerobic digestion and gasification] in hybrid systems" [33]. Additional priorities include advancing pretreatment technologies to enhance conversion efficiency, developing improved catalysts for tar cracking in gasification systems, and optimizing microbial consortia for anaerobic digestion of diverse feedstocks. The integration of artificial intelligence and advanced process control represents another promising direction for optimizing operational parameters and improving economic viability across all technology pathways.

For researchers and project developers, the technology selection process must balance technical maturity, capital requirements, operational complexity, and feedstock considerations within the context of local energy markets and policy frameworks. As the biomass power industry evolves amid increasing competition from other renewable sources, the economic viability of projects will increasingly depend on selecting the appropriate conversion technology matched to specific resource conditions and market opportunities.

The Impact of Government Incentives on Financial Models

The economic viability of biomass power projects is critically influenced by government incentives, which directly alter their financial models. These incentives are designed to bridge the cost gap between conventional fossil fuel-based power generation and renewable alternatives, making biomass projects more attractive to investors and developers. For researchers and scientists analyzing the economic sustainability of these projects, understanding the mechanics, eligibility, and quantitative impact of these incentives is fundamental. Financial models for biomass power incorporate projections of revenue, operating expenses, capital recovery, and risk, all of which are substantially modified by the inclusion of various government support mechanisms. This analysis provides a comparative guide to the predominant incentive structures, their integration into financial modeling, and the associated experimental protocols for assessing economic viability.

The core financial challenge for biomass power generation is its high initial capital cost compared to traditional coal power plants, coupled with significant costs for collecting, transporting, and storing biomass, which can account for 60–70% of the total cost of biomass power generation [38]. Government incentives aim to mitigate these financial hurdles, making the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) from biomass competitive. The type of incentive—whether a production-linked subsidy, an investment-based tax credit, or a phased rebate—shapes the project's revenue stream and risk profile, forming a key variable in any techno-economic assessment [39].

Comparative Analysis of Government Incentives

Government incentives for biomass power can be broadly categorized into two groups: those that subsidize the production of energy and those that subsidize the initial investment. The structural differences between these mechanisms have distinct implications for a project's cash flow, investor returns, and long-term financial sustainability.

Subsidy-Based Incentives

Subsidies that directly support operational revenue are common in the biomass sector. They are typically tied to the amount of energy produced or the quantity of biomass feedstock utilized.

Table 1: Comparison of Production and Investment-Based Incentives

| Incentive Type | Mechanism | Key Financial Model Impact | Representative Example |