Strategic Approaches to Minimize Transportation Costs for Low-Density Biomass

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to overcome the critical economic challenge of transporting low-density biomass, a key barrier in the bioenergy and biorefining sectors.

Strategic Approaches to Minimize Transportation Costs for Low-Density Biomass

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to overcome the critical economic challenge of transporting low-density biomass, a key barrier in the bioenergy and biorefining sectors. It details the fundamental physical and economic constraints of biomass logistics, explores proven and emerging preprocessing technologies like densification and torrefaction, and evaluates optimization models and transportation modes. Through case studies and comparative cost analyses, the article offers a validated framework for researchers and industry professionals to design cost-effective, resilient biomass supply chains, ultimately enhancing the viability of biomass as a renewable carbon source.

The Core Challenge: Understanding the Economic and Physical Constraints of Biomass Logistics

The Impact of Low Bulk Density on Transportation Efficiency and Cost

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Challenges in Low-Density Biomass Transport

This guide addresses frequent issues encountered when handling and transporting low-bulk-density biomass, a critical factor in minimizing costs for biomass research and application.

1. Problem: Low Load Factor Leading to High Transport Costs

- Question: Why does transporting low-density biomass result in disproportionately high costs per unit of energy?

- Explanation: Biomass often has a low weight per unit volume (low bulk density). This means transport vehicles reach volume capacity long before reaching their weight capacity, leading to inefficient fuel use and higher costs per ton of biomass transported [1].

- Solution: Focus on increasing the load factor. Research indicates that improving the load factor is one of the most significant levers for reducing total transportation costs, accounting for a major portion of cost variation [1]. Pre-processing biomass through densification methods like pelleting or briquetting can dramatically increase load capacity per trip.

2. Problem: Material Bridging, Ratholing, and Inconsistent Flow

- Question: Why does my biomass feedstock block or flow unevenly from hoppers and storage containers?

- Explanation: Low-density materials, especially those with fine particles or irregular shapes, are prone to interlocking (bridging) or forming stable cavities (ratholing) above discharge points. This disrupts material flow, causes operational delays, and leads to inconsistent feed rates for experiments or processing [2] [3].

- Solution:

- Equipment Selection: Use hoppers with specialized liners or aeration devices to promote mass flow [3].

- Material Testing: Conduct flowability tests, such as permeability and wall friction analysis, to design equipment that matches your biomass's specific characteristics [3].

- Handling Practices: Avoid over-compacting the material and use equipment that provides gentle agitation to maintain flow without degrading the biomass [4].

3. Problem: Excessive Dust Generation and Material Loss During Handling

- Question: How can I reduce product loss and safety hazards from dust during transfer operations?

- Explanation: The handling of low-density, friable biomass can generate significant dust. This represents a direct loss of material, compromises experimental accuracy, and poses explosion risks or respiratory hazards [5].

- Solution:

- Containment: Use totally enclosed conveying systems like cable drag or aero-mechanical conveyors instead of open belt conveyors [2].

- Dust Control: Integrate bag spout sealing systems with dedicated dust collection at transfer points [2].

- Material Pre-treatment: Control moisture levels to reduce dustiness, but avoid levels that cause clumping [4].

4. Problem: Rapid Equipment Wear and Tear

- Question: Why does my conveying and handling equipment require frequent maintenance when processing certain biomass types?

- Explanation: Some biomass feedstocks can be highly abrasive, accelerating the wear of screws, conveyor liners, and other components. This leads to costly downtime, maintenance, and potential contamination of research materials [3] [5].

- Solution:

- Compatible Materials: Specify equipment with hardened steel components, polymer coatings, or ceramic liners designed for abrasive materials [3].

- System Design: Select conveyor types that minimize the speed and force of impact. For highly abrasive materials, a cable drag conveyor can be more durable than a high-speed screw conveyor [2].

5. Problem: Inaccurate Dosing and Batching for Experiments

- Question: How can I ensure consistent and accurate amounts of biomass are delivered to my reactor or processing unit?

- Explanation: The variable flowability and low density of biomass make it difficult to achieve precise volumetric feeding, which can skew experimental results and process yields [2].

- Solution: Integrate weighing systems with automated controls. Semi-automatic bulk bag unloaders and fillers equipped with load cells and Programmable Logic Controllers (PLCs) can provide highly accurate dosing and batching, ensuring reproducibility in your research [2].

Key Quantitative Data on Transportation Cost Factors

The table below summarizes the influence of key variables on biomass road transport costs, as identified by machine learning analysis. Understanding these factors allows for targeted cost-reduction strategies [1].

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Biomass Road Transportation Costs

| Factor | Influence on Cost Variation (Multiple Linear Regression) | Influence on Cost Variation (Random Forest Model) | Explanation & Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Type | 31% | 31% | Specialized versus standard trailers impact efficiency and capacity utilization. |

| Distance | Minimal | 25% | While fixed costs are spread over distance, it remains a major variable cost driver. |

| Load Factor | 37% | 12% | The weight of biomass carried as a percentage of maximum capacity is critical. A low load factor is the primary cost driver for low-density materials. |

Experimental Protocols for Biomass Characterization

To design efficient transport and handling systems, researchers must first characterize the physical properties of their biomass. Below are standardized protocols for key tests.

Protocol 1: Determining Bulk Density

- Objective: To measure the mass of biomass per unit volume (e.g., kg/m³), which directly impacts transportation vehicle capacity and cost.

- Materials:

- A standardized container of known volume (V).

- Analytical balance.

- Biomass sample.

- Funnel or scoop.

- Methodology:

- Tare the weight of the empty container.

- Gently fill the container from a set height (e.g., 15 cm) using a funnel, without compacting the material.

- Strike off the excess biomass level with the top of the container using a straight edge.

- Weigh the filled container (M_full).

- Calculate the "loose" bulk density: (Mfull - Mcontainer) / V.

- For "tapped" density, tap or vibrate the container a specified number of times, refill, and re-weigh. This provides insight into consolidation behavior during transport.

- Data Interpretation: A lower bulk density confirms the challenge of low transport efficiency. Comparing loose and tapped density helps assess compressibility.

Protocol 2: Assessing Flowability Through Permeability Testing

- Objective: To evaluate how easily air passes through a bed of biomass, which predicts its potential for flooding, fluidization, or ratholing in hoppers.

- Materials:

- Permeameter (a cylinder with a porous base plate and air supply).

- Pressure gauge and flow meter.

- Biomass sample.

- Methodology:

- Fill the permeameter with a known mass and height of biomass.

- Subject the biomass to a consolidating stress to simulate conditions in a storage vessel.

- Pass a controlled, low-velocity air stream upward through the biomass bed.

- Measure the pressure drop across the bed and the air flow rate.

- Data Interpretation: A high pressure drop indicates low permeability, meaning the material is cohesive and likely to have poor flow characteristics (e.g., bridging). This data is essential for designing aeration systems for hoppers.

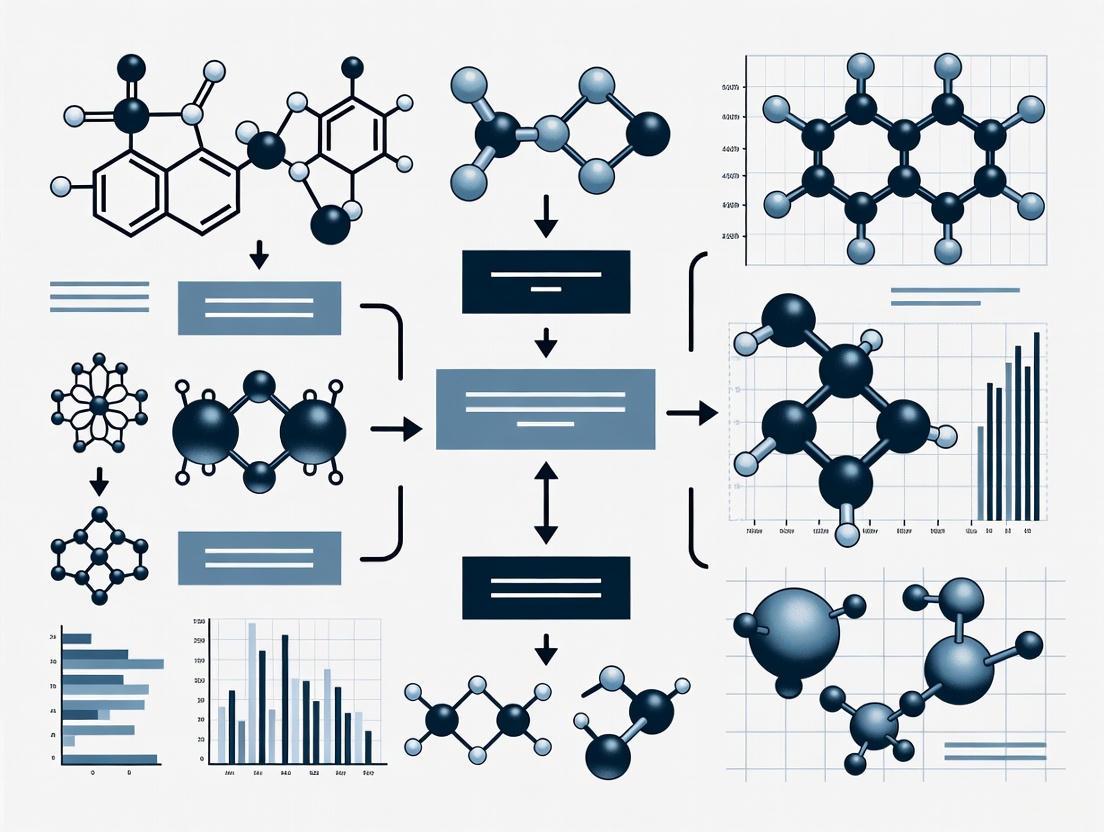

The following workflow outlines the systematic approach from material characterization to solution implementation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key equipment and technologies crucial for addressing low bulk density challenges in a research context.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Equipment for Biomass Handling Research

| Item | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk Density Tester | Precisely measures the mass per unit volume of biomass samples. | Fundamental for calculating transport efficiency and designing experiments. |

| Permeability Tester (Permeameter) | Quantifies how easily air flows through a biomass sample under consolidation. | Diagnoses potential flow problems (e.g., ratholing) in storage and feeding systems. |

| Particle Size Analyzer | Determines the particle size distribution of a milled or processed biomass. | Helps predict dust generation, flowability, and optimal densification methods. |

| Densification Press (Lab-Scale) | Compacts biomass into pellets or briquettes of a controlled density and size. | Used to test hypotheses on how pre-processing can improve load factors and reduce transport costs. |

| Flexible Screw Conveyor (Lab-Scale) | A versatile and economical method for moving small batches of biomass between process steps. | Useful for designing and testing material handling workflows in a controlled lab environment. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most impactful factor for reducing biomass transportation costs? A1: Improving the load factor is critically important. For low-cost, low-density biomass, transportation can dominate the total delivered cost. Increasing the load factor was identified as the most influential variable in one cost model, responsible for 37% of the variation in cost. This highlights the immense value of densification through pelleting or briquetting [1].

Q2: My biomass is cohesive and bridges in the hopper. What type of conveyor should I consider? A2: For cohesive materials, fully enclosed conveyors that actively induce flow are preferable. Cable drag conveyors are ideal for moving fragile, cohesive materials gently over long distances. Aero-mechanical conveyors are another hybrid option that offers high-speed, enclosed transfer without the complex air systems of pneumatic conveyors [2].

Q3: Are there any "green" benefits to optimizing transport for low-density biomass beyond cost? A3: Yes, significantly. Efficient transport directly reduces diesel consumption and associated CO₂ emissions per ton of biomass delivered [5]. Furthermore, the industry is exploring electric and biofuel-powered vehicles for transport, and optimizing load factors makes the use of these alternative vehicles more economically viable [6] [5].

Q4: We are planning a new pilot plant. Why is material testing so important? A4: Testing your specific biomass samples in a dedicated lab (like the one described in [3]) before finalizing equipment selection is crucial. It allows engineers to design systems based on your material's specific adhesiveness, cohesiveness, abrasiveness, and bulk density. This upfront investment prevents costly operational problems like blockages, excessive wear, or material degradation, ensuring higher uptime and more reliable data from your pilot studies [2] [3].

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

Q1: Why is moisture content a critical factor in minimizing biomass transportation costs? Moisture content directly impacts transportation efficiency, which constitutes 25–40% of total biomass supply chain costs [7]. High moisture increases weight without adding energy value, as a significant portion of the load becomes water instead of combustible material. This reduces the net energy density of the biomass, making transport less efficient and more costly per unit of delivered energy [8].

Q2: How does moisture content affect the heating value of biomass? There is a direct and strong inverse relationship between moisture content and calorific value. Higher moisture requires substantial energy to evaporate water during combustion, reducing overall system efficiency and combustion temperature. One study suggests an increase in moisture content from 0% to 40% can decrease the heating value (in MJ/kg) by approximately 66% [9].

Q3: What storage problems are caused by high moisture content? Storing high-moisture biomass carries significant risks:

- Composting and Biological Activity: Accelerated microbial growth leads to dry matter loss and generates heat [8].

- Mould and Mildew: Relative humidity above 75% promotes mould growth, which can damage organic cargo and pose health risks [10].

- Fire Risk: Biological activity can cause elevated temperatures, creating a potential for spontaneous combustion [8].

- Caking and Agglomeration: Increased cohesion and compressibility of powdered biomass can lead to bridging and difficult discharge from silos [11].

Q4: My biomass samples show inconsistent moisture readings. What are common pitfalls? Accurate moisture measurement is complex. Common issues include:

- Sample Heterogeneity: Variations in composition, granule size, or density within a batch cause inconsistent results. Proper homogenization through grinding or mixing is crucial [12].

- Environmental Factors: Ambient humidity and temperature can affect readings. Samples can reabsorb moisture after drying if the lab air is humid [12].

- Condensation: In sampling systems or storage containers, condensation invalidates the process by changing the water vapor content [13].

- Volatile Compounds: In oven-drying methods, other volatile organic compounds may evaporate with water, artificially inflating the moisture reading [12].

Q5: What is "container rain" and how does it relate to moisture damage during transport? "Container rain" or "container sweat" occurs when warm, moist air inside a shipping container hits colder surfaces (like the ceiling or walls), causing moisture to condense and "rain" onto the cargo. This is a major cause of moisture damage during transit, leading to mould, corrosion, caking, and ruined goods [14]. Real-time condition monitoring of humidity and temperature can help predict and mitigate this risk [14].

Table 1: Impact of Moisture Content on Biomass Properties and Costs

| Parameter | Impact of High Moisture Content | Quantitative Effect / Range | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transport Cost Share | Increases cost per unit of energy delivered | 25-40% of total supply chain cost | [7] |

| Heating Value | Decreases calorific value | ~66% decrease when going from 0% to 40% moisture | [9] |

| Dewatering Energy | Increases energy consumption for drying | Thermal evaporation: 700-1000 kWh/m³ water; Mechanical press: 30-50 kWh/m³ water | [15] |

| Combustion Efficiency | Reduces system efficiency and temperature | Must be driven off before combustion, using energy | [8] |

| Flowability (Storage) | Increases cohesion and adhesion | Deteriorates, leading to silo overhangs and discharge problems | [11] |

Table 2: Common Moisture Measurement Techniques

| Method | Typical Applications | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravimetric | Food, pharma, textiles (lab-based) | High accuracy; universal standard | Time-consuming; can lose other volatiles | [12] |

| Spectroscopic (NIR) | Food, pharma, textiles (on-line) | Non-contact; real-time data | Requires calibration; high initial cost | [9] |

| Karl Fischer Titration | Pharma, chemicals (lab-based) | High precision at low moisture levels | Involves hazardous chemicals; slower | [12] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining the Effect of Moisture on Mechanical Flow Properties

This protocol, adapted from a study on powdered biomass, details how to measure the effect of moisture content on flowability, which is critical for designing silos and handling systems [11].

I. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Jenike Shear Tester | The apparatus used to determine powder flowability under consolidation, simulating silo conditions. |

| V-Type Hopper Mixer | Used to homogenize and consistently humidify biomass samples to target moisture levels. |

| Convection Oven | For drying biomass samples to achieve a 0% moisture baseline. |

| Moisture Analyzer (e.g., RADWAG MA.R) | To accurately determine the moisture content of prepared samples via the gravimetric method. |

| Humid Air Stream System | A system that generates air with controlled humidity (e.g., RH 99%) to remoisturize dried samples. |

II. Methodology

- Sample Preparation:

- Comminute the biomass feedstock into a powder form.

- Obtain a 0% moisture content baseline by drying the material in a convection oven at 60°C.

- For other moisture levels, place the 0% sample in a V-type mixer. Humidify it using a stream of air at RH 99%, while the mixer rotates at 15 rpm.

- Determine humidification time via preliminary tests. Verify the final moisture content of sub-samples using the moisture analyzer (drying at 110°C to constant weight) [11].

Shear Testing:

- Place a prepared sample with a specific moisture content into the Jenike shear cell.

- Consolidate the sample under a defined normal stress (e.g., simulating the pressure in a silo).

- Shear the sample until failure, measuring the shear stress required.

- Repeat the shearing process under different normal stresses to generate a yield locus for that specific moisture content [11].

Data Analysis:

- Plot the yield locus (shear stress vs. normal stress) for each moisture level.

- Parameters like cohesion and internal friction angle can be derived from these plots. An increase in these values indicates poorer flowability.

The workflow for this experiment is summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol: Optimizing the Drying Process for Energy Efficiency

This protocol outlines steps to compare dewatering methods, which is essential for reducing the energy costs of moisture removal prior to transport.

I. Methodology

- Baseline Measurement:

- Determine the initial moisture content of the "green" biomass (e.g., wood chips with ~55-60% water) using a standard oven-dry method [15].

Mechanical Dewatering:

- Process a known mass of biomass through a high-pressure mechanical press.

- Weigh the biomass after pressing and calculate the new moisture content.

- Record the energy consumption of the press per cubic meter of water removed. Expected output moisture is ~38-40% for wood chips [15].

Thermal Drying:

- Split the biomass: dry one batch using only a thermal dryer (e.g., belt dryer), and dry the mechanically pre-treated batch in the same dryer to the same target moisture content.

- Precisely measure the energy consumption of the thermal dryer for both scenarios.

Analysis:

- Compare the total energy consumption (mechanical + thermal vs. thermal-only) to achieve the target moisture.

- Calculate the reduction in dryer load and the associated energy and cost savings.

The logical relationship and efficiency gains of a combined system are shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Biomass Moisture Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Moisture Sensor | Provides non-contact, real-time moisture monitoring on a production line, enabling immediate process adjustments and closed-loop control [9]. |

| Jenike Shear Tester | The industry-standard apparatus for characterizing the flow properties of powdered biomass under static loads, critical for silo and hopper design [11]. |

| Laboratory Moisture Analyzer | Provides fast and accurate gravimetric moisture content determination for small samples, used for calibration and validation of other methods. |

| High-Pressure Mechanical Press | Used for pre-treatment to remove loosely bound water from biomass mechanically, drastically reducing the energy load on subsequent thermal dryers [15]. |

| Karl Fischer Titration Apparatus | The gold-standard method for determining trace levels of moisture (down to 0.01%) with high precision, especially in sensitive applications [12]. |

| Real-Time Cargo Monitoring Sensors | IoT-enabled sensors that monitor temperature and humidity inside shipping containers, providing data to prevent "container rain" and moisture damage during transport [14]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Biomass Handling and Conversion

This guide addresses frequent challenges researchers face when working with lignocellulosic biomass, providing solutions to improve experimental consistency and efficiency.

1. Problem: Inconsistent Biomass Feedstock Quality

- Symptoms: Variable conversion yields, unstable process conditions, and irregular feed rates during experiments.

- Causes: Biomass fuels such as wood chips, sawdust, or pellets can vary significantly in size and moisture content [16]. This natural variability affects the stable operation and performance of conversion systems.

- Solutions:

- Material Characterization: Prior to experiments, determine critical properties including moisture content, particle size distribution, and bulk density [17].

- Pre-Processing: Implement drying, size reduction (milling/grinding), and sieving to achieve homogenized feedstock [16] [17].

- Supplier Selection: Source biomass from reliable suppliers who provide consistently sized and dry materials [16].

2. Problem: Biomass Flow Obstructions During Handling

- Symptoms: Bridging (arching) over hopper outlets, ratholing (channeling), complete blockages, and inconsistent feed rates to reactors.

- Causes: The inherent variability in the composition, moisture content, and particle size of biomass materials leads to several common flow issues [17].

- Solutions:

- Equipment Design: Utilize mass flow hoppers and specialized feeders designed specifically for biomass handling to promote uniform flow and reduce the risk of bridging and ratholing [17].

- Process Adjustment: For high-moisture biomass, implement pre-processing drying steps to improve flowability [17].

- Operational Protocol: Establish a proactive maintenance and monitoring program to identify potential flow issues before they cause significant disruptions [17].

3. Problem: Low Biomethane Yield from Anaerobic Digestion

- Symptoms: Methane production significantly below theoretical yields (e.g., below 330 mL CH₄/g volatile solids for many lignocellulosic feedstocks) and slow digestion rates [18].

- Causes: The recalcitrance of native lignocellulosic biomass, primarily due to the robust lignin structure, makes it resistant to microbial hydrolysis [18]. This is the rate-limiting step that reduces bioconversion efficiency.

- Solutions:

- Pretreatment Application: Apply chemical, physical, or biological pretreatment methods to disrupt the lignin seal and improve enzymatic accessibility [18].

- Biomass Selection: Select naturally less recalcitrant biomass varieties or genetically modified feedstocks where available and appropriate for the research [19].

- Process Optimization: Optimize digestion parameters (e.g., temperature, pH, solid-to-liquid ratio) specifically for the pretreated feedstock [18].

4. Problem: Reduced Thermal Conversion Efficiency

- Symptoms: Inefficient combustion, higher energy consumption, increased emissions of pollutants, and ash-related problems.

- Causes:

- Fuel Inconsistency: Variations in fuel quality lead to an unstable and inefficient combustion process [16].

- Ash Buildup: Ash from biomass combustion can accumulate on heat exchanger surfaces, obstructing heat transfer and reducing overall efficiency [16]. Furthermore, biomass ash often contains high concentrations of alkali and heavy metals, which can lead to corrosion of boiler piping [16].

- Solutions:

- Fuel Standardization: As with Issue #1, ensure consistent fuel quality through characterization and pre-processing.

- Maintenance Schedule: Implement regular cleaning schedules to remove ash deposits and prevent buildup on critical components [16].

- Corrosion Monitoring: Regularly inspect and maintain boiler piping to manage the effects of corrosive compounds [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is "biomass recalcitrance" and why is it a fundamental problem in bioenergy research? A1: Biomass recalcitrance is the natural resistance of plant cell walls to being broken down into their constituent sugars [20]. This robustness is due to the complex structure of the plant cell wall, a composite material primarily consisting of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which are interwoven and cross-linked [18] [20]. This structure, essential for plant survival, presents a major barrier because it limits the efficient and cost-effective release of sugars for fermentation into biofuels, making conversion processes more difficult and expensive than those for fossil fuels [1] [20].

Q2: How does biomass recalcitrance directly impact transportation and logistics costs? A2: Recalcitrance indirectly influences the entire supply chain. Biomass has a low bulk density, meaning it is bulky and light, leading to high transportation costs relative to its energy content [21]. Furthermore, the need for pretreatment to overcome recalcitrance often necessitates additional processing steps that can occur at different facilities. This potentially creates extra transportation legs for pre-processed material or requires a more complex, optimized supply chain to minimize total cost, which includes both transportation and conversion expenses [1].

Q3: Beyond the three main polymers, what other factors influence biomass recalcitrance? A3: The recalcitrance of a specific biomass sample is not determined by composition alone. Key influencing factors include:

- Plant Species and Genetics: Different species and even varieties have vastly different cell wall structures and lignin contents [19] [20].

- Anatomical Structure: The physical arrangement of vascular bundles, sclerenchyma, and parenchyma cells creates a complex 3D structure that hinders mass transport [22].

- Cell Wall Architecture: Features such as the crystallinity of cellulose, the specific chemical bonds between lignin and hemicellulose (e.g., lignin-carbohydrate complexes), and the pore surface area available for enzymes to access are critical [18] [22].

Q4: When should I consider hiring a professional service for my biomass research system? A4: Professional services should be engaged for tasks requiring specialized expertise or equipment that is not available in-house. This includes conducting a thorough and accurate assessment of equipment performance, designing custom biomass handling systems to resolve persistent flow issues, and performing advanced structural characterization of biomass (e.g., using synchrotron-based phase-contrast tomography to analyze 3D cell wall organization) [16] [22].

Quantitative Data on Biomass Recalcitrance and Conversion

Table 1: Methane Production from Various Lignocellulosic Feedstocks via Anaerobic Digestion [18]

| Biomass Type | Pretreatment Method | Methane Yield (mL CH₄/g VS) |

|---|---|---|

| Rice Straw | Fungal pretreatment | 152 - 263 |

| Miscanthus | None | 285 - 333 |

| Switchgrass (Summer) | Mulched and Alkalinization | 256.6 ± 8.2 |

| Wheat Straw | Laccase/peroxidase | 250.5 |

| Barley | None | 314.8 |

| Spruce | Not specified | Typically lower due to high lignin |

Table 2: Key Parameters Influencing Biomass Transportation Costs [1] This data, derived from a machine learning model (Random Forest), shows the relative importance of factors in predicting road transport costs.

| Parameter | Relative Influence (%) | Impact Description |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Type | 31% | The choice of truck and trailer configuration is the most significant factor. |

| Distance | 25% | Travel distance from feedstock source to processing facility. |

| Load Factor | 12% | The utilization of the vehicle's capacity; underloading increases cost per unit. |

| Other Factors | 32% | Includes fuel prices, labor, route topography, and operational overhead. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol 1: Assessing Biomass Recalcitrance via Enzymatic Hydrolysis Objective: To quantitatively determine the saccharification potential (sugar release) of a biomass sample, a key indicator of its recalcitrance. Materials:

- Milled and sieved biomass sample (e.g., 40-60 mesh particle size)

- Commercial cellulase enzyme cocktail (e.g., CTec2)

- Buffer solution (e.g., 0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 4.8)

- Water bath or incubator shaker

- Centrifuge

- HPLC or glucose assay kit for sugar quantification

Methodology:

- Biomass Preparation: Accurately weigh 100 mg of dry biomass (in triplicate) into screw-cap tubes.

- Reaction Setup: Add appropriate buffer and a standardized amount of cellulase enzymes to each tube. Include controls with inactivated enzymes.

- Incubation: Incubate the tubes at 50°C with constant agitation for 24-72 hours.

- Termination and Separation: Stop the reaction by heating the tubes to 100°C for 10 minutes. Centrifuge to separate the solid residue from the hydrolysate.

- Analysis: Analyze the supernatant for glucose and xylose content using HPLC or a colorimetric assay.

- Calculation: Calculate the percentage of glucan (or xylan) conversion based on the initial carbohydrate content of the biomass.

Protocol 2: Biomass Flowability Testing Using a Shear Cell Tester Objective: To characterize the flow properties of biomass powders and identify potential handling issues like bridging and ratholing. Materials:

- Jenike shear cell tester or ring shear tester

- Dried and milled biomass sample

- Controlled humidity chamber

Methodology:

- Sample Conditioning: Condition the biomass sample at a standardized relative humidity to ensure consistent moisture content.

- Cell Preparation: Carefully fill the shear cell with the sample, ensuring a consistent and reproducible packing procedure.

- Pre-Consolidation: Apply a specific normal load to consolidate the sample, simulating storage conditions in a bin or hopper.

- Shearing: Shear the sample under a series of lower normal loads to determine the yield locus (a plot of shear stress vs. normal stress).

- Data Analysis: From the yield locus, calculate key flow properties such as the unconfined yield strength, major principal stress, and flow function. These values are used to design hoppers and feeders that will ensure reliable, mass flow.

Visualization of Biomass Recalcitrance and Conversion Workflow

Biomass Recalcitrance Impact & Solution Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Biomass Recalcitrance Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Cellulase Cocktails | Enzyme mixtures containing cellulases, hemicellulases, and β-glucosidases to hydrolyze polysaccharides. | Standardized enzymatic saccharification assays to quantify sugar release from pretreated biomass [18]. |

| Lignin-Degrading Enzymes | Enzymes like laccases and peroxidases that target the lignin polymer. | Studying selective lignin removal or as a biological pretreatment method to reduce recalcitrance [18]. |

| Anaerobic Digestion Inoculum | A consortium of microorganisms (e.g., from sewage sludge or anaerobic digestate) for biomethane production. | Evaluating the ultimate biodegradability and biomethane potential (BMP) of biomass feedstocks in batch experiments [18]. |

| Chemical Pretreatment Agents | Alkalis (e.g., NaOH, NH₃) and acids (e.g., H₂SO₄) for chemical pretreatment. | Investigating the effect of delignification (alkali) or hemicellulose solubilization (acid) on deconstruction efficiency [18]. |

| Synchrotron Radiation Source | High-intensity X-ray source for advanced imaging techniques like Phase-Contrast Tomography (PCT). | Non-invasive 3D characterization of the cellular organization, pore structure, and surface area of biomass at high resolution [22]. |

Transportation constitutes a pivotal and often dominant component of the total delivered cost of biomass feedstocks in biofuel production. For low-cost or residue-based biomass, transportation expenses can represent a substantial portion of the total delivered price, frequently determining the overall economic viability of biofuel operations [1]. This technical support center provides researchers and scientists with targeted methodologies to analyze, troubleshoot, and optimize these critical logistics costs within their biofuel research and development projects.

The inherent challenge of biomass logistics stems from the low bulk density and dispersed geographical availability of raw biomass materials, which creates significant economic barriers to cost-competitive biofuel production [23]. Unlike fossil fuel feedstocks with concentrated extraction points and established infrastructure, biomass often requires complex collection, handling, and transportation systems from numerous distributed sources to biorefinery gates. Understanding and controlling these logistics parameters is therefore essential for advancing biofuel research toward commercial scalability.

Key Quantitative Data on Biomass Transportation Costs

Factor Contribution to Transportation Costs

Table 1: Relative Influence of Key Parameters on Biomass Transportation Costs

| Factor | Contribution in MLR Model | Contribution in Random Forest Model |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Type | 31% | 31% |

| Distance | Minimal Impact | 25% |

| Load Factor | 37% | 12% |

| Other Factors | 32% | 32% |

Data derived from machine learning analysis of global biomass road transport data [1]

Transportation Mode Characteristics

Table 2: Biomass Transportation System Efficiency Indicators

| Logistics Factor | Typical Range/Value | Research Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Shipping Distance | Highly variable based on logistics conditions | No universal optimal distance; system-specific analysis required [24] |

| Truck Transportation Efficiency | Higher for smaller plants | Appropriate for pilot-scale research facilities [24] |

| Large Plant Logistics | Less researched | Significant knowledge gap for commercial scaling [24] |

| System Efficiency Focus | Improving existing truck systems | Incremental optimization opportunities identified [24] |

Frequently Asked Questions: Biomass Logistics Troubleshooting

Q1: Why does transportation represent such a high cost component for low-density biomass?

Transportation costs dominate for low-density biomass due to fundamental material properties and supply chain structures. Raw biomass in its native state has low bulk density, meaning you're essentially transporting "air" in terms of energy content per unit volume. This is compounded by the geographically dispersed nature of biomass sources, which requires collection from multiple small-scale locations rather than centralized extraction points. The resulting logistics complexity involves numerous handling steps, high vehicle utilization challenges, and significant transportation distances that collectively inflate costs relative to the final delivered value of the material [1] [23].

Q2: What are the most influential factors we should prioritize in transportation cost modeling?

Based on comprehensive machine learning analysis of global biomass transport data, vehicle type emerges as the most consistent predictor (31% contribution in both MLR and random forest models), followed by transportation distance (25% contribution in the superior random forest model). Load factor shows variable importance depending on modeling approach (37% in MLR vs. 12% in random forest), suggesting context-dependent effects. Researchers should prioritize accurate characterization of these three parameters in their experimental designs and cost models, with particular attention to vehicle-specific cost structures and the non-linear relationship between distance and total costs [1].

Q3: How can we mitigate transportation costs for distributed biomass feedstocks?

Several strategies show promise for mitigating transportation costs:

- Preprocessing at Collection Points: Implementing grinding, drying, or densification at depots or collection points to increase biomass density before long-haul transportation [23]

- Optimal Facility Sizing: Matching biorefinery capacity to the economically viable collection radius, acknowledging the trade-offs between economies of scale and transportation distances [24]

- Load Factor Optimization: Maximizing vehicle utilization through improved scheduling, packaging, and route planning to address the significant cost impact of load efficiency [1]

- Modal Integration: Exploring rail or water transport alternatives for appropriate geographical contexts and scale [23]

Q4: What are the critical biomass attributes that impact transportation and handling costs?

The most impactful biomass attributes include:

- Moisture Content: Affects weight, degradation during storage, and energy density [23]

- Bulk Density: Directly influences transportation efficiency and vehicle payload utilization [23]

- Particle Size and Uniformity: Impacts handling characteristics and flowability [23]

- Aerobic Stability: Determines storage duration limits and potential losses [23]

- Chemical Composition Consistency: Affects conversion process efficiency and feedstock valuation [23]

Q5: Why do different modeling approaches yield conflicting results about factors like distance impact?

Different statistical approaches capture distinct aspects of the underlying cost relationships. Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) assumes linear relationships and independence of factors, which often poorly represents the complex, interactive nature of biomass transportation systems. Machine learning approaches like Random Forests can capture non-linear relationships and factor interactions, providing more accurate representations of real-world behavior. The minimal distance impact in MLR versus substantial (25%) impact in Random Forest models suggests that distance interacts with other factors like vehicle type, road conditions, and backhaul opportunities in ways that simple linear models cannot detect [1].

Experimental Protocols for Transportation Cost Analysis

Machine Learning-Based Cost Prediction Protocol

This protocol enables researchers to develop accurate transportation cost models using machine learning approaches, which have demonstrated superior performance (R-squared = 97.4%) compared to traditional regression methods [1].

Step 1: Data Collection Parameters

- Collect minimum 15 independent variables including: vehicle type, load factor, distance, feedstock type, road conditions, labor costs, fuel prices, maintenance factors, climate conditions, and regulatory environment

- Ensure data spans adequate operational range for each parameter to avoid extrapolation

- Include both financial (costs) and operational (time, distance, weight) metrics

Step 2: Data Preprocessing

- Normalize all financial data to consistent currency and year values

- Handle missing data through appropriate imputation methods

- Encode categorical variables (e.g., vehicle type) using one-hot encoding

- Split dataset into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) subsets

Step 3: Model Training

- Implement Random Forest algorithm with minimum 100 trees

- Tune hyperparameters including maximum depth, minimum samples per leaf, and feature subset size

- Train comparative Artificial Neural Network with minimum one hidden layer

- Validate model performance using k-fold cross-validation

Step 4: Factor Importance Analysis

- Calculate permutation importance for each independent variable

- Generate partial dependence plots to visualize factor relationships

- Quantify relative percentage contribution of each factor to cost variation

Step 5: Model Validation

- Test predictive accuracy on withheld test dataset

- Compare Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and R-squared values against null models

- Validate with operational data from actual biomass transportation operations

Biomass Preprocessing Impact Assessment Protocol

This methodology evaluates how preprocessing interventions affect transportation economics through density improvement and handling characteristic enhancement.

Step 1: Baseline Characterization

- Measure initial bulk density, moisture content, and particle size distribution

- Document handling requirements (manual vs. mechanical)

- Quantify aerobicity through respiration rate measurements

- Establish degradation rate under standardized storage conditions

Step 2: Preprocessing Intervention

- Apply comminution (grinding, chipping) to achieve target particle sizes

- Implement mechanical drying to reduce moisture content to economic optimum

- Conduct densification (pelletization, briquetting) with and without binders

- Apply chemical or biological stabilization treatments as relevant

Step 3: Transportation Simulation

- Measure improved bulk density and flow characteristics

- Quantify vehicle payload improvement potential

- Assess loading/unloading time requirements

- Evaluate storage stability and loss rates

Step 4: Economic Analysis

- Calculate preprocessing cost increments

- Quantify transportation cost reductions

- Determine net economic benefit under various distance scenarios

- Model breakeven distances for preprocessing implementation

Biomass Logistics System Visualization

Biomass Logistics Cost Factors Flow

This diagram illustrates the sequential stages of biomass logistics with critical cost influencers and loss pathways identified from research. The visualization highlights where the most significant cost factors (vehicle type, distance, load factor) exert their influence within the supply chain [1] [23].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Biomass Logistics Research

Table 3: Key Analytical Tools for Biomass Logistics Research

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forest Algorithm | Predictive cost modeling | Accurately predicts transportation costs (R² = 97.4%) capturing non-linear relationships [1] |

| Bulk Density Analyzer | Material characterization | Quantifies biomass compaction potential and transportation efficiency [23] |

| Moisture Meter | Quality control | Determines weight impacts and storage stability during logistics [23] |

| Aerobic Respiration Monitor | Degradation assessment | Measures biomass losses during storage phases of logistics [23] |

| GIS Mapping Software | Spatial analysis | Optimizes collection routes and facility siting based on biomass distribution [24] |

| Life Cycle Assessment Tool | Environmental impact quantification | Evaluates net emissions of logistics operations including transportation [25] |

Advanced Methodologies: Integrating Waste-Derived Biofuels

Food System Waste Conversion Protocol

This protocol enables researchers to quantify the potential of waste-derived biofuels specifically for decarbonizing transportation, creating an internal loop within food systems [25].

Step 1: Waste Inventory Assessment

- Quantify Used Cooking Oil (UCO) availability from food service operations

- Calculate Crop Residue (CR) availability using residue-to-product ratios

- Map geographical distribution of waste sources relative to biorefinery location

- Assess collection infrastructure requirements and costs

Step 2: Conversion Pathway Selection

- Implement esterification-hydrogenation for UCO to biodiesel production

- Apply HEFA (Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids) technology for aviation fuel

- Utilize fast pyrolysis for crop residue conversion to bio-oil

- Employ gasification-Fischer-Tropsch synthesis for premium liquid fuels from residues

Step 3: Transportation Application Testing

- Validate fuel performance in appropriate engines

- Measure emissions profiles compared to conventional fuels

- Assess blending compatibility and stability

- Conduct lifecycle carbon accounting

Step 4: System Integration Analysis

- Model complete food system internal loop efficiency

- Calculate net carbon reduction potential

- Determine infrastructure requirements for scale-up

- Evaluate economic competitiveness with policy support

The research findings consolidated in this technical support center demonstrate that transportation logistics represent not merely an operational detail but a fundamental determinant of biofuel economic viability. The most promising research directions emerging from current literature include:

- Advanced Modeling Approaches: Leveraging machine learning techniques that capture the non-linear relationships and factor interactions in biomass transportation, moving beyond traditional regression limitations [1]

- Integrated Preprocessing Strategies: Developing decentralized preprocessing technologies that transform biomass properties before long-haul transportation to dramatically improve load factors and reduce costs [23]

- Waste-to-Biofuel Pathways: Exploiting food system waste streams (UCO, crop residues) that offer dual benefits of waste management and biofuel production while potentially creating internal loops within regional food systems [25]

- Holistic System Design: Designing biofuel production systems that explicitly acknowledge and optimize transportation logistics as a primary design parameter rather than secondary consideration

By focusing research efforts on these strategic priorities, researchers and scientists can significantly advance the economic competitiveness of biofuels relative to conventional fossil fuels, ultimately contributing to broader adoption of these renewable resources and transition toward more sustainable logistics practices [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most critical factors influencing biomass transportation costs? Research indicates that transportation costs are a pivotal and substantial component of the total delivered cost of low-density biomass. The key factors influencing these costs have been rigorously analyzed. A machine learning study identified vehicle type, transport distance, and load factor as the most significant predictors, contributing 31%, 25%, and 12% to the overall cost variation, respectively [1]. Another review emphasized that transportation accounts for a considerable portion of value chain costs and can be optimized through mechanisms like resource sharing and improved planning [26].

FAQ 2: How do spatial disparities affect the local biomass supply chain? Spatial disparities—inequalities in the distribution of geographic and socioeconomic factors like forest cover, income, education, and infrastructure—fundamentally alter the determinants of biomass supply. Research in Benin showed that intentions to supply forestry residues for clean energy were driven by different factors (e.g., attitudes, subjective norms, environmental concern) in the less-urbanized, higher-poverty northern region compared to the more urbanized south [27]. This means that strategies to secure biomass supply must be tailored to specific regional contexts to be effective.

FAQ 3: What logistical strategies can improve transportation efficiency? A systematic review of biomass transportation identified seven key Efficiency Mechanisms (EMs) for improving planning, especially at the operational level [26]:

- Resource sharing: Pooling transportation assets across different value chains.

- Joint decision making: Coordinating decisions across different parts of the supply chain.

- Multimodal integration: Using multiple modes of transport (e.g., road and rail).

- Transit preparation: Pre-processing biomass (e.g., densification) before transport.

- Financial agreements: Structuring contracts to share costs and benefits.

- Information sharing: Enhancing data flow on feedstock availability and quality.

- Local feedstock integration: Sourcing biomass from local suppliers to reduce distance.

FAQ 4: What is the role of system-level optimization in managing biomass supply chains? For a supply chain to be economically viable, an integrated optimization approach is crucial. This involves simultaneously designing the supply network (sourcing, storage, transport) and optimizing the conversion process parameters. One study formulated this as a Mixed Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) problem to maximize the Net Present Value (NPV) of the system. This approach ensures that the entire chain, from farm to final energy product, is configured for maximum efficiency and cost-effectiveness [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High and Unpredictable Transportation Costs

Symptoms:

- Transportation costs represent a dominant portion of your total feedstock cost.

- Inability to accurately forecast logistics expenses for project planning.

- Cost volatility due to fluctuating biomass availability across regions.

Solutions:

- Implement Predictive Modeling: Move beyond traditional regression analysis. Employ machine learning models, such as Random Forests, which have demonstrated superior performance (R-squared value of 97.4%) in predicting transportation costs by accounting for complex, non-linear interactions between factors like vehicle type, distance, and load factor [1].

- Optimize Load Factors: Prioritize achieving a high load factor, as it is a major cost driver. This may involve investing in compaction or densification technologies to increase the biomass density transported per trip [1].

- Explore Resource Sharing: At an operational level, investigate sharing transportation resources (e.g., trucks, rail cars) with other nearby bioenergy plants or even other industries to reduce idle time and increase utilization [26].

Problem 2: Inefficient Supply Chain Network Design

Symptoms:

- Long and costly transportation routes from scattered biomass sources.

- Uncertainty in the optimal location and capacity for storage facilities and biorefineries.

- Inability to adapt to fluctuations in biomass availability and energy demand.

Solutions:

- Apply Integrated Optimization Frameworks: Use an MINLP model to co-optimize your supply chain network and conversion process. The model should determine the optimal selection of biomass supply zones, storage locations, transportation links, and plant operating conditions to maximize economic viability [28].

- Conduct Spatial Mapping: Launch a mapping effort to identify and quantify biomass availability and suitability across different regions. This data is essential for linking growers with processing facilities and building a resilient supply chain [29].

- Design for Flexibility: Incorporate flexibility into your supply chain design from the start to ensure adaptability to variable feedstock availability and market conditions [28].

Problem 3: Regional Resistance or Lack of Biomass Supply

Symptoms:

- Low willingness among landowners or farmers in a specific region to supply biomass.

- Ineffective "one-size-fits-all" policies for encouraging biomass supply.

Solutions:

- Conduct Regionalized Social Analysis: Use a methodological framework like Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB). This helps identify the key psychological, social, and economic factors (e.g., attitudes, environmental concern, knowledge, subjective norms) that drive supply intentions in a specific region [27].

- Develop Tailored Policies: Based on the SEM/TPB analysis, create region-specific initiatives. For example, in a region with low environmental awareness, educational campaigns might be key. In a region with high social influence, programs involving community leaders could be more effective [27].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Predicting Transportation Costs with Machine Learning

This methodology is adapted from a study demonstrating the superiority of Random Forests over multiple linear regression for this task [1].

1. Data Collection: Gather global data on completed biomass transport operations. The key independent variables to include are:

- Vehicle Type (e.g., truck with specific trailer)

- Distance Traveled (km)

- Load Factor (% of vehicle capacity utilized)

- Biomass Type (e.g., wood chips, straw)

- Road Type (e.g., highway, rural)

- Fuel Price

- Season

2. Data Pre-processing:

- Clean the data to handle missing values and outliers.

- Encode categorical variables (like Vehicle Type) numerically.

- Normalize or scale numerical variables if required by the algorithm.

3. Model Training and Validation:

- Split the dataset into a training set (e.g., 80%) and a testing set (e.g., 20%).

- Train a Random Forest Regressor model on the training set. This model creates multiple decision trees and aggregates their results for a more accurate prediction.

- Validate the model's performance on the withheld testing set using metrics like R-squared and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

4. Interpretation:

- Use the trained model's feature importance attribute to rank the impact of each variable (e.g., Vehicle Type, Distance, Load Factor) on the final transportation cost.

Protocol 2: Optimizing the Supply Chain using MINLP

This protocol is based on an integrated optimization framework for a biomass supply network and energy conversion process [28].

1. Problem Formulation:

- Objective Function: Define the goal, typically to maximize the system's Net Present Value (NPV) over the project lifetime. The NPV calculation includes revenues from energy sales, minus capital and operational expenditures (CAPEX/OPEX), which include transportation costs.

- Decision Variables: These include both binary/integer choices (e.g., whether to select a supply zone, the location of facilities) and continuous choices (e.g., biomass flow quantities, process operating conditions).

- Constraints: Define all physical and operational limits, such as biomass availability in each zone, storage capacities, conversion plant capacity, and energy demand.

2. Model Implementation:

- Formulate the problem as a Mixed Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) model in a suitable optimization software environment.

- The model should integrate the supply chain with the process model (e.g., a Steam Rankine Cycle for heat and power generation) to allow for simultaneous optimization.

3. Model Solving and Analysis:

- Use an appropriate solver algorithm (e.g., Branch and Bound) to find the optimal solution.

- Perform sensitivity analysis on key uncertain parameters, such as biomass feedstock cost, electricity price, and biofuel demand, to understand their impact on the optimal supply chain configuration and economic viability.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated optimization framework and the key factors it must consider.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2772390925000514 https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11081-024-09930-3

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Biomass Transportation Costs

| Factor | Influence on Cost | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Type | High | Most significant predictor in Random Forest model (31% contribution) [1]. |

| Transport Distance | Medium-High | Second most significant predictor in Random Forest model (25% contribution) [1]. |

| Load Factor | High | A dominant factor in multiple linear regression models (37% contribution) [1]. |

| Spatial Disparities | Variable | Alters the fundamental determinants of local biomass supply intention, requiring tailored policies [27]. |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | Models the spatial distribution of biomass resources and calculates transport routes and distances for network optimization [28]. |

| Random Forest Algorithm | A machine learning method used to build highly accurate predictive models for transportation costs, outperforming traditional regression [1]. |

| Mixed Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) Solver | Computational tool used to solve the integrated optimization problem of supply chain design and process operation to maximize NPV [28]. |

| Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Software | Analyzes complex relationships and mediation effects between psychological, social, and economic factors influencing biomass supply intentions in different regions [27]. |

| Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) Framework | A social psychology framework used to design surveys and models to understand the determinants of stakeholders' intentions to supply biomass [27]. |

Proven Solutions and Technologies: From Densification to Preprocessing

Technical Specifications and Performance Data

The table below summarizes key properties of raw and densified biomass forms, which are critical for assessing their impact on transportation logistics.

Table 1: Properties of Raw and Densified Biomass Forms

| Densification Form / Feedstock | Bulk Density (kg/m³) | Energy Density (MJ/m³) | Key Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loose Biomass (for comparison) | |||

| Wheat Straw [30] | 36.1 | 444 | Low density, highly inefficient for transport. |

| Corn Stover [30] | 52.1 | 900 | Loose format leads to high volumetric transport costs. |

| Forest Wood Residue [30] | 150 | 2,735 | |

| Baled Biomass | |||

| Wheat Straw Bales [30] | 115 - 130 | ~1,500 - 1,700 (estimated) | Efficient for initial collection and storage. |

| Densified Biomass | |||

| Wood Chips [30] | 220 - 265 | 2,693 - 3,244 | Size reduction improves density over loose residues. |

| Biomass Pellets [30] | 600 - 700 (typical) | ~10,000+ (estimated) | High density and excellent flowability for handling. |

| Biomass Briquettes [31] | Up to 964 | Varies with feedstock | High density; durability ranges from 61% to 96.6% [31]. |

| Torrefied Biomass [30] | Higher than pellets | Higher than raw biomass | Further increases energy density and hydrophobicity. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Pellet Press Failures and Solutions

Table 2: Troubleshooting a Flat Die Biomass Pellet Press [32]

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Production Capacity | 1. New die is not clean.2. Incorrect material moisture.3. Gap between roller and die is too large.4. Worn die or roller.5. Slipping triangle belt. | 1. Grind oil-based material for lubrication.2. Adjust material moisture content.3. Adjust the impacted bolt.4. Replace worn parts.5. Tighten or replace the belts. |

| Excessive Powder in Pellets | 1. Moisture content is too low.2. Die is overly worn or has a small reduction ratio. | 1. Slightly increase water content.2. Replace with a new die. |

| Rough Pellet Surface | 1. Moisture content is too high.2. Using a new die for the first time. | 1. Reduce the water content.2. Grind oil-based material repeatedly to condition. |

| Abnormal Noise | 1. Hard foreign objects in the machine.2. Damaged bearing.3. Loose components. | 1. Shut down and clear the foreign matter.2. Replace the bearing.3. Tighten all components. |

| Machine Stops Suddenly | 1. Excessive load.2. Foreign matter in the box.3. Low voltage/power. | 1. Enlarge the gap between roller and die.2. Shut down and clear the matter.3. Replace the power supply or motor. |

System-Level Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA)

Deviations in feedstock quality can cause failures across the entire preprocessing system, impacting final product quality and process efficiency [33]. The following diagram maps the cause-and-effect relationships of these failures.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Briquette Performance and Quality Evaluation

This protocol outlines methods to produce and characterize briquettes for energy applications, integrating procedures from multiple studies [34] [31].

1.0 Feedstock Preparation and Briquetting

- Raw Material Processing: Reduce biomass feedstock particle size using a hammer mill. Sieve the material into specific particle size distributions (e.g., <100 μm, 100–200 μm) for controlled experiments [35].

- Mixing: Combine the biomass with binders (e.g., starch, Arabic gum) and additives like clay using a mechanical mixer. The composition can be optimized using statistical methods like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) [34].

- Densification: Use a piston press, screw press, or roller press for briquetting. A typical hydraulic press can operate at pressures ranging from 50 to 150 MPa. Record the pressure and dwell time used [30] [31].

2.0 Physical and Mechanical Characterization

- Bulk Density: Measure the mass of a briquette and divide by its volume, calculated from its geometrical dimensions [31].

- Durability (Shatter Index): Test using a pellet durability tester (e.g., PDT-110, Seedburo Equipment). Tumble a 100g sample of briquettes for a set time (e.g., 10 minutes) at 50 rpm. The Shatter Index (SI) is the percentage of retained mass after tumbling [34].

SI = (Final Weight / Initial Weight) * 100. - Compressive Strength: Measure the maximum force (in Newtons, N) a briquette can withstand before failure using a universal testing machine. Compare to industry benchmarks (e.g., charcoal at ~1540 N) [35].

3.0 Chemical and Thermal Characterization

- Proximate Analysis: Determine moisture, volatile matter, fixed carbon, and ash content following standard ASTM methods [34].

- Ultimate Analysis: Measure the carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur content using an elemental analyzer. Low sulfur content (<0.1%) is a key advantage [34].

- Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA): Assess thermal stability by heating a small sample (~10 mg) from ambient temperature to 900°C in an inert (N₂) or air atmosphere. Identify key decomposition stages: drying (100–300°C), devolatilization (300–420°C), and char combustion (420–830°C) [34].

4.0 Performance Evaluation

- Water Boiling Test (WBT): Evaluate thermal efficiency by measuring the time and fuel mass required to boil a fixed volume of water. Efficiency can range from 36% to 72% depending on briquette composition [34].

- Ignition and Burning Time: Record the time required for initial ignition and the total duration of stable combustion [34].

Workflow: From Raw Biomass to Conversion-Ready Feedstock

The following diagram illustrates the complete preprocessing workflow to produce quality-controlled feedstock, minimizing risks that lead to increased costs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the single most critical factor to control for high-quality pelleting or briquetting? Moisture content is paramount. Even small variations impact pellet density, surface sheen, and durability [36]. Most systems require a moisture content between 6-18% for briquetting and 4-6% for pelletization [30] [32]. Excess moisture causes soft, rough-textured products, while insufficient moisture leads to excessive dust and poor binding [32].

Q2: How does particle size of the raw material affect the final densified product? Reducing particle size significantly improves the quality of densified products. Smaller particles rearrange more efficiently during compaction, filling voids and creating a denser structure. This leads to higher compressive strength, reduced surface cracks, and improved durability [35]. However, excessively fine particles can reduce porosity and negatively impact reactivity in some thermochemical applications [35].

Q3: From a cost perspective, why is densification crucial for minimizing biomass transportation costs? Biomass in its raw form has very low bulk density and energy density (see Table 1). Transporting loose biomass means paying to move mostly air, which is economically unviable. Densification (e.g., into pellets or briquettes) can increase bulk density by several-fold, dramatically increasing the amount of energy transported per truckload and reducing the frequency of trips [30] [37]. This directly lowers the cost per unit of energy delivered.

Q4: What are the primary functions of binders like Arabic gum and clay in briquette production? Binders serve distinct roles. Arabic gum acts as an organic binder, providing cohesion between biomass particles and enhancing the mechanical strength of the briquette [34]. Clay contributes significantly to the mechanical strength and structural integrity of the briquette, and can also influence ash content [34]. The optimal ratio of these components can be determined using optimization techniques like Response Surface Methodology (RSM).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Equipment for Biomass Densification Research

| Item | Function in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Arabic Gum | Natural binder to provide cohesion and improve mechanical strength of briquettes [34]. | Food-grade powder, used in optimized ratios with biomass and clay [34]. |

| Clay | Additive to enhance mechanical strength and structure of densified products [34]. | Can contribute to ash content; ratio requires optimization [34]. |

| Biomass Grinder | To reduce feedstock particle size for controlled experiments and improved binding. | Hammer mill with interchangeable sieve screens (e.g., 0.18-3 mm for pelleting) [35] [30]. |

| Flat-Die Pellet Press | Laboratory-scale machine for producing pellets for testing and evaluation. | Various models with different power; allows study of pressure, moisture, and feedstock effects [32]. |

| Pellet Durability Tester | Quantifies the resistance of densified products to abrasion and impact during handling. | e.g., PDT-110; provides Durability Index (%) [31]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Characterizes the thermal decomposition behavior and stability of biomass fuels. | Measures mass change vs. temperature/time; identifies ignition and burnout temperatures [34]. |

| Universal Testing Machine | Measures the mechanical strength (compressive strength) of individual briquettes or pellets. | Reports maximum load (in Newtons, N) before failure [35]. |

Torrefaction is a thermochemical pretreatment process used to upgrade the properties of raw biomass, making it a more suitable and efficient fuel source. The process involves the slow heating of biomass in an inert or oxygen-deficit environment to temperatures typically between 200°C and 300°C [38] [39]. During torrefaction, the biomass undergoes a series of physical and chemical transformations that significantly improve its energy density and handling properties, directly addressing the challenges of transporting low-density biomass [40].

This thermal treatment partly decomposes the biomass, releasing moisture and volatile organic compounds. The resulting solid product, often called torrefied biomass or "bio-coal," is a relatively dry, blackened material with superior fuel characteristics compared to the original feedstock [40] [39]. The process is mildly endothermic and is sometimes described as a form of mild pyrolysis, roasting, or high-temperature drying [41].

Key Properties and Benefits for Transportation Logistics

The primary motivation for torrefying biomass within a supply chain context is to overcome the inherent logistical challenges of raw biomass, which is often bulky, moist, and geographically dispersed. Torrefaction directly mitigates these issues by enhancing key fuel properties, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Property Changes in Biomass After Torrefaction and Their Impact on Logistics

| Property | Raw Biomass | Torrefied Biomass | Impact on Transportation & Handling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture Content | High (often >30%) | Very Low (1-3% wet basis) [38] | Reduces weight for transport; prevents biological degradation during storage [40] [42]. |

| Energy Density (Mass) | Lower Calorific Value (~18-19 MJ/kg) | Higher Calorific Value (~20-24 MJ/kg) [38] | More energy is transported per unit mass, improving freight efficiency [40]. |

| Energy Density (Volume) | ~10-11 GJ/m³ | ~18-20 GJ/m³ (when densified) [40] | Drives a 40-50% reduction in transportation costs per unit of energy [40]. |

| Hydrophobicity | Hydrophilic (absorbs water) | Hydrophobic (repels water) [40] [38] | Allows for open-air storage without significant moisture uptake, simplifying and reducing storage costs [40]. |

| Grindability | Fibrous and tough | Brittle [40] | Reduces energy required for grinding by 80-90%, lowering preprocessing costs [40] [42]. |

| Biological Activity | Subject to decay and rotting | All biological activity is stopped [40] | Eliminates risk of fire and decomposition during storage, enabling long-term logistics planning [40]. |

Experimental Protocol: Laboratory-Scale Torrefaction

This section provides a detailed methodology for conducting a standard torrefaction experiment, allowing researchers to generate reproducible results for analyzing the process's efficacy.

Objective

To torrefy a biomass feedstock at a specified temperature and residence time, and to evaluate the mass yield, energy yield, and changes in key physicochemical properties of the product.

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Equipment

| Item | Function/Description | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Feedstock | Raw material (e.g., wood chips, agricultural residues). | Particle size should be uniform; typically pre-dried to <10% moisture content for consistent results [38]. |

| Tube Furnace / Reactor | Provides controlled heating in an inert atmosphere. | Must maintain temperatures up to 300°C ± 5°C. Can be fixed bed, rotary drum, or fluidized bed [38]. |

| Inert Gas Supply | Creates an oxygen-free environment to prevent combustion. | High-purity Nitrogen (N₂) or Argon is typically used, with a continuous flow rate (e.g., 0.5-1 L/min) [39]. |

| Temperature Controller | Precisely regulates and programs the reactor heating rate and temperature. | Essential for controlling process severity (temperature and residence time) [38]. |

| Gas Washing System | Captures and treats volatile gases and condensable tars released during torrefaction. | Often uses a series of condensers and cold traps. |

| Analytical Equipment | For characterizing feedstock and products. | Includes calorimeter (for HHV), thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA), and elemental analyzer (CHNS-O) [41]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Feedstock Preparation: Reduce the biomass to a uniform particle size (e.g., 1-2 mm) using a mill or grinder. Determine the initial moisture content and gross calorific value.

- Reactor Loading: Place a known mass (e.g., 10-50 g) of the prepared biomass into the reactor crucible.

- Purging: Seal the reactor and purge it with an inert gas (N₂) for a sufficient time (e.g., 15-20 minutes) to ensure a complete oxygen-free environment.

- Heating/Torrefaction: Initiate the heating program. A standard protocol is:

- Cooling and Product Collection: After the desired residence time, turn off the furnace and allow the reactor to cool to near room temperature under a continuous flow of inert gas.

- Product Recovery: Carefully remove the torrefied solid product from the reactor. Weigh it to determine the mass yield.

- Analysis: Perform proximate, ultimate, and calorific value analysis on the torrefied biomass.

Data Analysis and Key Calculations

- Mass Yield (MY):

(Mass of torrefied biomass / Mass of raw biomass) × 100% - Energy Yield (EY):

Mass Yield × (HHV_torrefied / HHV_raw) × 100%[38]

Diagram 1: Torrefaction Experimental Workflow

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Q1: Our torrefied biomass product has a lower energy density than expected. What could be the cause?

- Cause A: Insufficient torrefaction severity. Low temperature or short residence time leads to incomplete devolatilization.

- Solution: Increase the reaction temperature within the 200-300°C range and/or extend the residence time. Monitor the mass yield, as a lower yield typically correlates with a higher energy density product.

- Cause B: Inert gas flow rate is too high. This can cause excessive cooling of the sample or sweep away heat too quickly, preventing the biomass from reaching the target temperature.

- Solution: Optimize the inert gas flow rate to be sufficient for maintaining an anaerobic environment but low enough to not interfere with heat transfer.

Q2: The torrefied material is not hydrophobic and gains moisture during storage. Why?

- Cause: The torrefaction process was too mild. The destruction of hydroxyl groups (-OH), which are responsible for water absorption, occurs more completely at higher severities, primarily through the decomposition of hemicellulose [38].

- Solution: Ensure the torrefaction temperature is adequate (typically above 250°C). Verify that the reactor is properly sealed and that the inert atmosphere is maintained throughout the process to prevent combustion, which can alter the chemical pathways.

Q3: We are experiencing significant clogging and tar formation in the reactor outlet and gas lines.

- Cause: Rapid release and condensation of volatiles. At higher torrefaction severities, more tars and condensable gases are produced. If the reactor off-gas system is not hot enough, these vapors will condense.

- Solution: Heat trace the outlet pipes and gas handling system to a temperature above the dew point of the torrefaction gases (typically above 150°C). Consider using a series of condensers and cold traps specifically designed to capture these tars for easier cleaning and analysis.

Q4: How do we select the right type of reactor for torrefaction research?

- Answer: The choice depends on the research focus. Common laboratory-scale reactors include:

- Fixed Bed Reactors: Simple, good for fundamental kinetics studies.

- Fluidized Bed Reactors: Excellent heat and mass transfer, providing very uniform temperature and product quality [38].

- Moving Bed Reactors: Good for continuous operation and scale-up studies, allowing for a uniform product with controlled residence time [38].

- Solution: For initial screening of biomass feedstocks, a fixed bed system is often sufficient. For process development and continuous operation, a fluidized bed or moving bed reactor is more appropriate.

Q5: The grindability of our torrefied product does not seem to have improved. What is the issue?

- Cause: Inadequate hemicellulose degradation and lignin transformation. Hemicellulose is the most reactive polymer and degrades first, making the biomass more brittle. Lignin also softens at torrefaction temperatures, and upon cooling, it resolidifies, contributing to brittleness [40] [38].

- Solution: Increase the torrefaction severity. Grindability improves significantly as the process temperature increases, especially above 275°C. Analyze the feedstock's lignocellulosic composition, as different biomasses (e.g., woody vs. herbaceous) respond differently.

Within biomass research, a primary challenge is the high cost of transporting raw, low-density materials. Efficient comminution—the process of reducing biomass size through chipping, grinding, or shredding—is a critical preprocessing step to overcome this. By increasing biomass bulk density and improving flowability, proper comminution directly minimizes transportation costs and enhances handling efficiency for subsequent processing [43] [44]. This guide addresses common operational challenges and provides optimized protocols to ensure these goals are met.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for Common Comminution Issues

FAQ 1: Why is my equipment experiencing rapid wear of cutting components?

The primary cause is abrasive inorganic particles (e.g., quartz) present in biomass feedstocks, introduced through soil contamination or contained within plant cells [45]. This abrasion leads to irregular particle size, increased power consumption, and frequent downtime [45].

Solutions:

- Material Selection: Use cutter materials with superior wear resistance. One study demonstrated that using cutters made of iron-borided D2 tool steel reduced wear by one order of magnitude compared to conventional D2 tool steel, while WC-Co inserts improved wear resistance by 8 times in knife mills [45].

- Pre-Cleaning: Implement a pre-cleaning stage to remove sand, dust, and metal fragments from the raw biomass, thereby reducing abrasive contact [46].