Predicting Biomass Particle Residence Time: A Machine Learning & CFD Fusion Guide for Pharmaceutical Researchers

This article explores the integrated application of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and Machine Learning (ML) to predict the residence time of biomass particles, a critical parameter in pharmaceutical process development.

Predicting Biomass Particle Residence Time: A Machine Learning & CFD Fusion Guide for Pharmaceutical Researchers

Abstract

This article explores the integrated application of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and Machine Learning (ML) to predict the residence time of biomass particles, a critical parameter in pharmaceutical process development. We provide a comprehensive guide covering foundational theory, methodological implementation of ML-CFD workflows, optimization strategies for model accuracy, and comparative validation against traditional methods. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this resource bridges advanced simulation techniques with data-driven prediction to enhance the design and optimization of bioreactors, drying processes, and other unit operations involving particulate biomass.

Understanding Residence Time: The Critical Link Between CFD, Biomass, and Pharmaceutical Process Efficacy

Defining Biomass Particle Residence Time and Its Impact on Drug Product Quality

Biomass particle residence time (BPRT) in bioreactors is a critical process parameter in the manufacturing of biologics and advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs). It directly influences cell viability, metabolic productivity, and the consistency of critical quality attributes (CQAs) such as glycosylation patterns and aggregate formation. This Application Note details protocols for measuring BPRT, analyzes its impact on drug quality, and frames the discussion within a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and Machine Learning (ML) predictive modeling research thesis.

BPRT is defined as the distribution of time that cell aggregates, microcarriers, or encapsulated cell clusters spend within different zones of a bioreactor vessel. Heterogeneous residence time distributions can lead to sub-populations of cells experiencing varying degrees of nutrient deprivation, shear stress, and waste accumulation, ultimately impacting product titer and quality.

Quantitative Data on BPRT Impact

Table 1: Impact of BPRT Heterogeneity on Key Process and Product Metrics

| Process Parameter | Low/Uniform BPRT Regime | High/Variable BPRT Regime | Measured Impact on CQA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific Productivity | Consistent, High | Reduced, Variable | ±10-25% in titer |

| Viability & Apoptosis | >95% viability | Can drop to <80% | Increased host cell protein (HCP) levels |

| Glycosylation Profile | Consistent macro-/micro-heterogeneity | Increased fucosylation, reduced galactosylation | Altered Fc effector function & PK/PD |

| Aggregate Formation | Minimal (<2%) | Elevated (5-15%) | Impacts immunogenicity risk |

| Lactate Metabolism | Efficient, low steady-state | Accumulation, overflow metabolism | Alters pH dynamics & cell health |

Table 2: Common Methods for BPRT Estimation & Measurement

| Method | Principle | Typical Resolution | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tracer Particle Tracking (CFD) | Simulated particle trajectories | High (theoretical) | Requires validation; computational cost |

| Image-Based Inline Probe | Direct observation of particle flow | Medium (local) | Fouling risk; limited field of view |

| Radioactive/PIT Tagging | Physical tracking of tagged particles | Low (bulk distribution) | Regulatory & safety hurdles |

| ML Surrogate Model | Predicts RTD from sensor data (pH, pO2, etc.) | Medium to High | Demands extensive training dataset |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Empirical BPRT Distribution Using Tracer Microcarriers

Objective: To experimentally determine the residence time distribution of biomass particles in a stirred-tank bioreactor.

Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Tracer Preparation: Fluorescently tag a representative sample (e.g., 5% of total) of microcarriers or synthetic biomass mimics (alginate beads) with a stable, biocompatible fluorophore (e.g., CellTracker Red).

- Pulse Injection: At time t=0, introduce the tagged tracer particles as a discrete pulse into the operating bioreactor with an established, representative cell culture.

- Sampling & Detection: Using a validated, automated sampling loop coupled to a flow-through fluorometer, measure the fluorescence intensity at the reactor outlet or a designated sampling port every 30 seconds for 3-5 reactor volume turnovers.

- Data Analysis: Plot normalized fluorescence intensity (C/C₀) vs. time. Calculate the mean residence time (τ) and the variance (σ²) of the distribution. Fit data to tank-in-series or dispersion models to characterize mixing.

Protocol 2: Correlating Local BPRT to Product Quality Attributes

Objective: To isolate sub-populations of cells based on inferred residence time and analyze their product. Procedure:

- Zonal Sampling: Employ a multi-port bioreactor or CFD-guided sampling to withdraw culture from predicted high-shear (impeller) and low-shear (surface, baffle) zones.

- Rapid Cell Sorting: Immediately separate cells/particles from each zone via low-g centrifugation. Isolate secreted product from each zone supernatant via magnetic bead-based capture.

- CQA Analysis: Analyze zone-specific product samples via:

- HPLC-SEC: For aggregate and fragment levels.

- HILIC/UPLC: For N-glycan profiling.

- Mass Spectrometry: For charge variant analysis.

- Correlation: Statistically correlate CQA data with CFD-predicted shear stress and nutrient exposure times for each sampled zone.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for BPRT Research

| Item & Example Product | Function in BPRT Studies |

|---|---|

| Functionalized Microcarriers (Cytodex 3, SoloHill) | Biomass mimics; can be tagged for tracer studies. |

| Biocompatible Fluorophores (CellTracker dyes) | Label particles/cells for visual and spectroscopic tracking. |

| Inline Particle Analyzer (Microsensor GmbH) | Real-time, image-based particle size and count monitoring. |

| CFD Software (ANSYS Fluent, COMSOL) | Model fluid flow and predict particle trajectories. |

| ML Framework (TensorFlow, PyTorch) | Build surrogate models to predict RTD from process data. |

| Multi-Port Bioreactor Vessel (Applikon, Sartorius) | Enables spatially resolved sampling for zone-specific analysis. |

| Rapid Product Capture Beads (Protein A/G Magnetic Beads) | Isolate product quickly from small volume zone samples. |

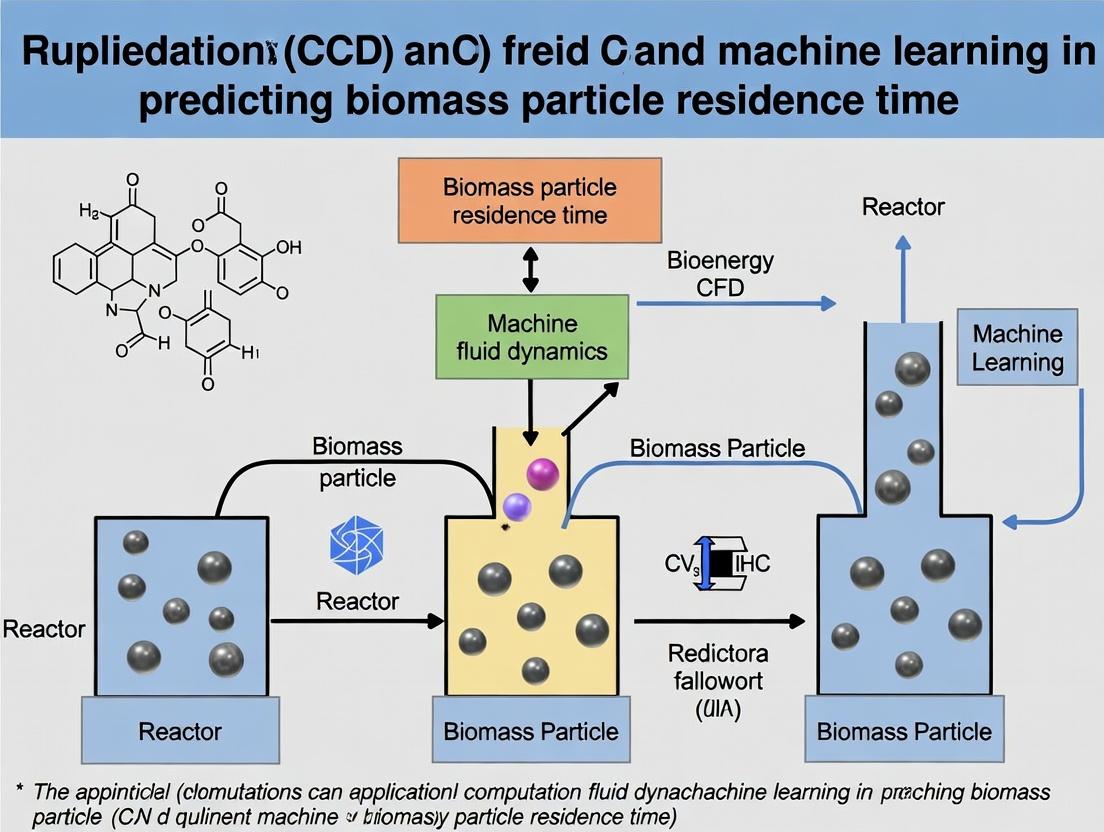

Visualizing the Integrated CFD-ML Workflow for BPRT Prediction

Diagram Title: CFD-ML Workflow for BPRT Prediction & Quality Control

Diagram Title: BPRT Impact Pathway on Drug Product CQAs

Accurately defining and controlling BPRT is paramount for robust bioprocess scale-up and consistent drug quality. The integration of high-fidelity CFD simulations to generate physical insights, coupled with ML models that learn from both simulated and experimental data, presents a powerful thesis research direction. This hybrid approach can lead to the development of real-time, predictive digital twins for bioreactors, enabling proactive control of BPRT and ensuring that all biomass particles reside in an optimal environment for producing therapeutics with the desired quality profile.

Within a broader thesis on CFD-Machine Learning Prediction of Biomass Particle Residence Time, selecting an appropriate multiphase modeling approach is critical. Residence time, a key parameter for conversion efficiency in reactors like fluidized beds or pyrolysis units, is governed by complex particle-fluid interactions. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) provides the framework to model these multiphase flows, primarily through Eulerian and Lagrangian paradigms, whose accurate implementation directly impacts the quality of training data for subsequent machine learning models.

Core Theoretical Approaches: Eulerian vs. Lagrangian

Conceptual Foundations

Eulerian Approach: Treats both fluid and dispersed phases (e.g., particles, droplets) as interpenetrating continua. Phases are described by volume fractions and solved using averaged Navier-Stokes equations. Lagrangian Approach: Tracks the motion of individual discrete particles (or parcels representing many particles) through the continuous fluid phase by solving Newton's second law.

Comparative Analysis: Application to Biomass Particle Flows

The choice between methods involves trade-offs in computational cost, detail, and applicability, as summarized below.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Eulerian and Lagrangian Methods for Biomass Flow Modeling

| Aspect | Eulerian-Eulerian (Two-Fluid Model) | Eulerian-Lagrangian (Discrete Particle Model/DPM) |

|---|---|---|

| Phase Treatment | All phases as continua. | Fluid as continuum; particles as discrete entities. |

| Typical Volume Fraction | High (>10%). | Low to moderate (<10-12% for uncoupled, higher with MP-PIC). |

| Interphase Momentum Exchange | Modeled via drag laws (e.g., Gidaspow, Syamlal-O'Brien). | Calculated for each particle/parcel; drag laws applied locally. |

| Particle-Size Distribution | Requires multiple solid phases (e.g., Kinetic Theory of Granular Flows). | Inherently handles distribution. |

| Inter-Particle Collisions | Modeled via granular viscosity/pressure (KTGF). | Modeled via Discrete Element Method (DEM) or stochastic collision models. |

| Computational Cost | Lower, scales with mesh count. | Higher, scales with particle count and trajectory integration. |

| Primary Output for Residence Time | Statistical distribution from phase fraction fields. | Direct, individual particle trajectories and histories. |

| Ideal for Thesis Context | Dense, fast fluidized beds. | Sparser flows, detailed particle history for ML feature engineering. |

Application Notes for Biomass Residence Time Prediction

Key Considerations

- Particle Shape & Complexity: Biomass particles are non-spherical and porous. Both approaches require model adjustments (e.g., shape factors, custom drag models).

- Reactive Flows: Pyrolysis or gasification introduces mass and energy exchange. Eulerian methods use reaction rates per phase; Lagrangian methods assign reactions to particles.

- Data for Machine Learning: Lagrangian methods naturally generate high-dimensional training data (trajectory, velocity, local conditions). Eulerian data requires extraction from field statistics.

Protocol: Generating Lagrangian Particle Data for ML Training

This protocol outlines steps to create a dataset of synthetic particle residence times using CFD.

Aim: To simulate the injection and tracking of biomass particles in a pilot-scale fluidized bed reactor to generate trajectory data for ML model training.

Software: ANSYS Fluent / OpenFOAM / MFiX with DPM/DDPM/MP-PIC capability.

Procedure:

- Single-Phase Fluid Solution: Establish a converged, steady-state solution for the continuous gas phase (air/steam) in the reactor geometry.

- Particle Property Definition: Define biomass particle properties (density: ~500-800 kg/m³, diameter distribution: 100-1000 µm, shape factor: 0.6-0.9). Use a non-spherical drag model if available.

- Injection Setup: Define injection points (e.g., fuel feed port). Specify particle initial velocity, temperature, and mass flow rate.

- Coupling & Physics: Enable two-way coupling. Select appropriate force models (drag, lift, virtual mass). For dense flows, use the MP-PIC or DEM-coupled model to handle particle collisions.

- Tracking & Data Extraction: Run transient simulation. Configure tracking to record for each particle/parcel:

Particle ID,Time,Position (X,Y,Z),Velocity,Local Gas Velocity,Temperature,Diameter,Drag Force. - Residence Time Calculation: Post-process to determine the time elapsed between injection and exit at a defined outlet boundary. Filter data for particles that fully convert (if reactive).

- Dataset Assembly: Compile all particle histories into a structured table (e.g., CSV, HDF5). Each row represents a particle, with features (mean velocity, max temperature, path length, etc.) and the target variable:

Residence Time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Key CFD Modeling "Reagents" for Multiphase Biomass Flows

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| OpenFOAM | Open-source CFD toolbox; offers flexible solvers for multiphase flows (e.g., reactingMultiphaseEulerFoam, coalChemistryFoam, DPMFoam). |

Critical for customizable, research-grade simulations. |

| ANSYS Fluent | Commercial CFD software with robust Eulerian-Eulerian and DPM/Lagrangian solvers. | User-friendly interface for complex physics setup. |

| MFiX | Open-source suite from NETL specialized for multiphase reacting flows. | Includes powerful DEM and MP-PIC methods for granular flows. |

| Gidaspow Drag Model | Blends Wen & Yu and Ergun equations for fluid-particle momentum exchange. | Standard for dense fluidized bed Eulerian simulations. |

| Schiller-Naumann Drag Model | Model for drag on spherical particles. | Common baseline in Lagrangian simulations. |

| Kinetic Theory of Granular Flows (KTGF) | Framework modeling particle-phase stresses and viscosity in Eulerian approach. | Provides closure for solid-phase rheology. |

| Discrete Element Method (DEM) | Models collision forces between individual Lagrangian particles. | Computationally expensive but high-fidelity. |

| Multiphase Particle-In-Cell (MP-PIC) | Hybrid method using Lagrangian parcels mapped to an Eulerian grid for collisions. | Efficient for very large numbers of particles. |

| Paraview / Tecplot | High-performance visualization and data analysis tools. | Essential for analyzing flow fields and particle datasets. |

Visualized Workflows

Title: CFD Approach Selection for Biomass Particle Flows

Title: Lagrangian Particle Tracking Data Generation Protocol

Within computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and machine learning (ML) research aimed at predicting biomass particle residence time in thermochemical reactors (e.g., fluidized beds, entrained flow gasifiers), four key particle properties critically determine trajectory and, consequently, conversion efficiency. Accurate prediction mandates high-fidelity experimental data on these properties for both model input and validation. This application note details standardized protocols for their characterization.

Table 1: Typical Ranges and Trajectory Impact of Key Biomass Particle Properties

| Property | Typical Range | Primary Impact on Trajectory & Residence Time | Relevance to CFD-ML Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size (Equivalent Diameter) | 50 µm - 6 mm | Dictates drag force. Larger particles have higher inertia, may penetrate deeper into reactor or segregate. | Critical input parameter for discrete phase models (DPM). ML features often include size distributions. |

| Density (Particle Density) | 500 - 1400 kg/m³ | Influences gravitational settling and centrifugal forces. Directly affects terminal velocity. | Required for force balance equations in CFD. Often coupled with size as a combined feature (e.g., mass). |

| Shape (Sphericity, Aspect Ratio) | Sphericity: 0.5 (flakes) - 0.9 (granular) | Alters drag coefficient (Cd). Non-spherical shapes increase drag, reducing settling velocity. | Sphericity is a correction factor in drag models. Shape descriptors are complex but valuable ML inputs. |

| Moisture Content (MC) | 5% - 50% (wt. wet basis) | Affects particle mass, density, and particle-gas interactions (e.g., drying, steam generation). Can cause agglomeration. | Impacts initial conditions and introduces coupled heat/mass transfer phenomena, adding complexity to ML prediction. |

Table 2: Measured Property Data for Common Biomass Types

| Biomass Type | Mean Particle Size (mm) | Particle Density (kg/m³) | Sphericity (-) | Moisture Content (% w.b.) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine Wood Chips | 2.5 ± 1.1 | 720 ± 50 | 0.65 ± 0.15 | 12.5 ± 3.0 | NREL 2023 |

| Wheat Straw (Chopped) | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 580 ± 70 | 0.55 ± 0.20 | 8.2 ± 2.5 | Bioresource Tech. 2024 |

| Corn Stover (Milled) | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 640 ± 60 | 0.70 ± 0.10 | 10.1 ± 2.0 | Biomass & Bioenergy 2023 |

| Miscanthus (Pelletized) | 6.0 ± 0.5 | 1150 ± 100 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 7.5 ± 1.5 | Fuel 2024 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Particle Size and Shape Characterization via Dynamic Image Analysis

Objective: To determine particle size distribution (PSD) and shape descriptors (e.g., sphericity, aspect ratio). Principle: Particles are dispersed and conveyed past a high-resolution camera. Software analyzes projected 2D images to calculate size and shape parameters based on equivalent diameters. Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Obtain a representative sample (>500 particles). For cohesive materials, use a dry dispersing unit.

- System Calibration: Use a certified calibration target (e.g., NIST-traceable ruler).

- Measurement: Feed sample steadily through the analyzer (e.g., Retsch CAMSIZER, Microtrac MRB). Ensure proper illumination and focusing.

- Data Acquisition: Run until statistical validity is reached (typically >50k particle detections). Export PSD (d10, d50, d90) and shape data (sphericity Ψ, aspect ratio AR).

- Calculation of Sphericity: Ψ = (4πA/P²), where A is projected area and P is perimeter, averaged for particle population.

Protocol 2: Particle Density Measurement via Gas Pycnometry

Objective: To measure the true skeletal density of biomass particles, excluding open and closed pores. Principle: Boyle’s Law (P1V1 = P2V2). A known sample volume displaces gas within a calibrated chamber, allowing calculation of solid volume. Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Oven-dry particles at 105°C for 24h to remove moisture. Cool in a desiccator.

- Cell Volume Calibration: Perform a calibration run with an empty sample cell and a calibration sphere of known volume.

- Sample Measurement: Weigh the empty sample cell (mcell). Add a known mass of dried sample (msample). Seal and place in pycnometer.

- Analysis: Run the analysis using an inert gas (He or N2). The instrument calculates the solid volume (V_solid).

- Calculation: Particle Density (ρparticle) = msample / V_solid. Repeat in triplicate.

Protocol 3: Moisture Content Determination via Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Objective: To accurately determine the moisture content of biomass particles on a wet mass basis. Principle: Mass loss upon controlled heating is monitored. The mass loss in the ~100-110°C range is attributed to evaporation of free water. Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize biomass and immediately sub-sample into a TGA crucible.

- Baseline & Tare: Run an empty crucible through the temperature program to establish a baseline.

- Sample Loading: Precisely weigh the crucible with the fresh, undried sample (m_initial).

- Temperature Program: Heat from ambient to 105°C at 10°C/min under N2 purge (50 ml/min). Hold at 105°C until mass stabilization (typically 30-60 min).

- Data Analysis: Moisture Content (% wet basis) = [(minitial - mdry) / m_initial] * 100%.

Integration into CFD-ML Workflow

Diagram Title: Biomass Property Data Workflow for CFD-ML Integration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Biomass Particle Characterization

| Item | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Image Analyzer (e.g., CAMSIZER, PartAn) | High-throughput measurement of particle size and shape distribution. | Essential for obtaining statistically significant shape data. Dry dispersion attachment recommended for biomass. |

| Gas Pycnometer (e.g., Micromeritics AccuPyc) | Measures absolute (skeletal) density of solid particles using gas displacement. | Use Helium for finest pores. Sample must be thoroughly pre-dried. |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Precisely measures moisture content and other volatile components via controlled heating. | Standard method for MC. Low heating rate during drying step prevents artefactual mass loss from decomposition. |

| Standard Sieve Set (ISO/ASMT) | For fractional sizing and obtaining narrow size cuts for controlled experiments. | Necessary for preparing monodisperse samples to isolate size effects in validation experiments. |

| Desiccator Cabinet | Stores dried samples prior to density or compositional analysis to prevent moisture re-absorption. | Use indicating silica gel desiccant. Critical for maintaining sample integrity post-drying. |

| Inert Purge Gas (N2 or He, high purity) | Used in TGA and pycnometry to provide an inert, moisture-free atmosphere. | Prevents oxidative decomposition during heating in TGA and ensures accurate volume measurement in pycnometry. |

| NIST-Traceable Calibration Standards | For verifying the accuracy of particle size analyzers and pycnometer cell volume. | Mandatory for ensuring data quality and cross-lab reproducibility. |

Application Notes

Pure Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) remains the gold standard for high-fidelity simulation of complex multiphase flows, such as those found in biomass conversion reactors (e.g., fluidized beds, entrained flow gasifiers). Within the thesis context of predicting biomass particle residence time—a critical parameter for reaction yield, product distribution, and catalyst deactivation in thermochemical biorefining and pharmaceutical precursor synthesis—pure CFD faces significant challenges.

Primary Challenge (Computational Cost): Resolving the Lagrangian tracking of thousands of discrete biomass particles coupled with turbulent, reactive fluid phases demands exorbitant computational resources. A single representative simulation can span weeks on high-performance computing (HPC) clusters, rendering parametric studies and design optimization prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

Proposed Solution (Predictive Acceleration): Machine Learning (ML)-accelerated frameworks offer a paradigm shift. The core thesis investigates developing hybrid CFD-ML surrogate models. These models are trained on a strategically sampled set of high-fidelity CFD simulations. Once trained, they can predict particle residence time distributions (RTDs) for new operating conditions (e.g., inlet velocity, particle shape/size distribution, temperature) in near-real-time, bypassing the need for a full CFD solve.

Key Quantitative Data on Computational Cost:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Simulation Methods for Biomass Particle RTD Prediction

| Method | Spatial Resolution | Typical Particle Count | Wall-clock Time (per simulation) | Primary Cost Driver |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure CFD (LES-DEM) | ~10-50 million cells | 100,000 - 1,000,000 | 1-4 weeks (HPC) | Coupled fluid-particle solve, small timesteps |

| Pure CFD (RANS-DPM) | ~1-5 million cells | 10,000 - 100,000 | 2-7 days (HPC) | Turbulence closure, particle coupling |

| ML Surrogate (Trained) | N/A (Data-driven) | N/A (Encoded in model) | Seconds to Minutes (Workstation) | Forward model inference |

| Hybrid Data Generation (CFD for ML Training) | ~5-10 million cells | 50,000 - 200,000 | 3-10 days per case (HPC) | Initial dataset creation |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Generation of High-Fidelity CFD Training Data for ML Model Objective: To produce a high-quality, diverse dataset of biomass particle trajectories and residence times for training a machine learning surrogate model. Methodology:

- Case Parameterization: Define the design space: fluidization velocity (1.5 - 3.0 m/s), particle sphericity (0.7 - 1.0), particle diameter distribution (200 - 1000 µm), biomass particle density (500 - 800 kg/m³), and reactor temperature (800 - 1100 K).

- CFD Setup (ANSYS Fluent/OpenFOAM): a. Solver: Use a transient pressure-based coupled solver. b. Turbulence: Employ a Scale-Resolving Simulation (SRS) model such as Stress-Blended Eddy Simulation (SBES). c. Multiphase Model: Use the Discrete Element Method (DEM) coupled with a Eulerian fluid phase. d. Drag Model: Apply the Gidaspow drag model. e. Boundary Conditions: Set inlet as velocity inlet, outlet as pressure outlet, walls with no-slip and appropriate restitution coefficients for particles.

- Particle Injection & Tracking: Inject Lagrangian particles stochastically at the reactor inlet over the first 0.5 seconds of physical simulation time. Record the full trajectory (position, velocity) and residence time for each particle.

- Data Extraction: Export time-series data of global parameters (pressure drop, voidage) and all individual particle data. Assemble into a structured database with inputs (operating conditions, particle properties) and outputs (residence time, exit location).

Protocol 2.2: Development and Training of a Graph Neural Network (GNN) Surrogate Objective: To create an ML model that predicts particle-level residence time from system parameters and particle initial conditions. Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize all input features. Structure data as a graph where nodes represent particles with features (diameter, sphericity, injection location), and edges represent inferred spatial proximity within the reactor flow field.

- Model Architecture: Implement a Message-Passing Graph Neural Network (MPNN). The model will consist of: a. Encoder: A dense network for initial node feature embedding. b. Processor: 4-6 message-passing layers that aggregate neighbor information to model particle-particle and particle-flow interactions. c. Decoder: A final multilayer perceptron (MLP) that maps the updated node embeddings to a scalar residence time prediction.

- Training: Use 80% of the CFD-generated data for training. Employ Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss on residence time, optimized with the AdamW optimizer. Validate on the remaining 20% to prevent overfitting.

- Validation: Benchmark the GNN's predictions against a hold-out set of pure CFD results not used in training, comparing both mean residence time and full residence time distribution (RTD).

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram Title: Thesis Workflow: From CFD Challenge to ML-Accelerated Solution

Diagram Title: GNN Surrogate Model Architecture for Particle-Level Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for Hybrid CFD-ML Research on Particle Residence Time

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Runs the foundational high-fidelity CFD simulations for data generation. Requires significant CPU/GPU cores and RAM. | Linux cluster with >1000 cores, >256 GB RAM per node, high-speed interconnect (InfiniBand). |

| Commercial/Open-Source CFD Solver | The engine for performing the pure CFD simulations. Must support coupled Lagrangian-Eulerian methods. | ANSYS Fluent, STAR-CCM+, OpenFOAM (open-source). |

| Machine Learning Framework | Provides libraries for building, training, and validating the surrogate ML models. | PyTorch (preferred for GNNs), TensorFlow, JAX. |

| Graph Neural Network Library | Specialized toolkit for constructing and training GNN architectures on particle data graphs. | PyTorch Geometric (PyG), Deep Graph Library (DGL). |

| Biomass Particle Property Database | Curated source of realistic input parameters for simulations (density, shape, size distribution). | NREL Biomass Feedstock Database, experimental characterization data. |

| Scientific Data Management Platform | Manages the large, complex dataset of CFD inputs and outputs for versioning and reproducibility. | TensorFlow Data Validation, DVC (Data Version Control), custom HDF5/ParaView pipelines. |

| High-Fidelity Validation Data | Experimental results from a well-characterized test reactor (e.g., PIV, particle tracking). | Critical for final validation of the hybrid CFD-ML framework's predictions. |

Application Notes

The integration of Machine Learning (ML) as a surrogate for Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) addresses the critical computational bottleneck in high-fidelity simulations, particularly relevant for complex, multiphase systems like biomass particle flow. Within the thesis context of predicting biomass particle residence time in bioreactors, CFD-ML surrogates enable rapid, iterative design and optimization, which is crucial for scaling bioprocesses in pharmaceutical and biofuel production.

Key Advantages:

- Speed: ML models reduce prediction time from hours/days (full CFD) to milliseconds.

- Cost: Drastically lowers computational resource requirements.

- Optimization: Enables feasible high-dimensional parameter sweeps for reactor design.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Certain ML frameworks (e.g., Gaussian Processes) provide built-in uncertainty estimates for predictions.

Primary Challenges:

- Data Fidelity: Surrogate model accuracy is intrinsically tied to the quality and scope of the training data generated by high-fidelity CFD.

- Generalization: Models can struggle to extrapolate beyond the design space of the training dataset (e.g., novel particle geometries or extreme flow regimes).

- Dynamic Systems: Capturing transient residence time distributions requires careful formulation of the ML task (e.g., using time-series networks or labeling with integral parameters).

Table 1: Comparison of CFD Simulation vs. ML Surrogate Model Performance for a Canonical Fluidized Bed Case (Biomass Particles)

| Metric | High-Fidelity CFD (Discrete Element Method + CFD) | ML Surrogate (Trained on CFD Data) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. Simulation Wall-clock Time | ~72-120 hours | < 1 second | For a single operational condition. CFD time scales with particle count. |

| Avg. Absolute Error in Residence Time | Baseline (Ground Truth) | 2.5 - 4.1% | Error on test dataset (unseen conditions). |

| Memory Requirement (Per Run) | ~50-100 GB | ~100 MB | ML model size post-training. |

| Typical Training Data Requirement | Not Applicable | 500 - 5,000 CFD runs | Varies with model complexity & system nonlinearity. |

| Suitability for Real-Time Control | No | Yes | ML inference speed supports real-time applications. |

Table 2: Common ML Algorithms for CFD Surrogates in Particle Systems

| Algorithm | Typical Architecture/Type | Best For | Residence Time Prediction Accuracy (Reported R² Range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Connected Neural Network (FCNN) | Deep, dense layers (3-10 layers). | Mapping static inputs (inlet velocity, particle size) to scalar outputs (mean residence time). | 0.88 - 0.97 |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | 2D/3D convolutional layers. | Learning from spatial flow field snapshots (e.g., velocity contours) to predict distributions. | 0.91 - 0.98* |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | Message-passing networks on graph structures. | Systems where particle-particle interactions are dominant; direct handling of discrete particles. | 0.93 - 0.99 |

| Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) | Non-parametric probabilistic model. | Data-efficient learning, uncertainty quantification, and smaller parameter studies. | 0.85 - 0.95 |

*Accuracy for predicting full residence time distribution curves.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Generating the Training Dataset from High-Fidelity CFD

Objective: To produce a high-quality, labeled dataset for training an ML surrogate model to predict biomass particle residence time distribution (RTD).

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Procedure:

- Define the Design Space: Identify key input parameters (e.g., inlet gas velocity

U_g(0.5 - 2.5 m/s), biomass particle diameterd_p(500 - 2000 µm), particle densityρ_p(700 - 1200 kg/m³), reactor geometry ratioH/D). - Design of Experiments (DoE): Use a space-filling sampling method (e.g., Latin Hypercube Sampling) to generate

N(e.g., 1000) unique sets of input parameters within the defined bounds. - CFD Simulation Setup:

a. For each parameter set from the DoE, configure the multiphase CFD model (e.g., Eulerian-Lagrangian with DEM coupling).

b. Define the reactor geometry (e.g., fluidized bed) in the simulation pre-processor. Mesh independence must be verified prior to production runs.

c. Set physical models: turbulence (k-ε or LES), drag law (Gidaspow), and particle-wall boundary conditions.

d. Implement a particle injection and tracking protocol. Inject a pulse of

M(e.g., 10,000) computationally labeled biomass particles at the inlet. - Execution & Monitoring: Run the transient CFD simulation until all injected particles exit the domain. Monitor for numerical stability.

- Data Extraction (Labeling):

a. For each simulated particle, record its exit time

t_exit. Calculate the system's Residence Time Distribution (RTD) and key summary statistics: mean residence time (τ), variance (σ²), and dimensionless Peclet number (Pe). b. Extract relevant flow field features at steady-state (before particle injection), such as averaged velocity magnitude, volume fraction, or turbulent kinetic energy in predefined control volumes. c. Package the data: Each DoE sampleibecomes one data point:Inputs = [U_g, d_p, ρ_p, H/D, ... flow features];Outputs = [τ, σ², Pe, (or full RTD curve)]. - Dataset Curation: Split the compiled dataset into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets. Apply feature scaling (e.g., StandardScaler from scikit-learn).

Protocol: Training and Validating the ML Surrogate Model

Objective: To develop a calibrated ML model that accurately maps input parameters to residence time predictions.

Procedure:

- Model Selection & Initialization: Choose an algorithm (see Table 2). Initialize the model with heuristic or literature-based hyperparameters (e.g., number of layers, learning rate).

- Training Loop:

a. Pass training input data through the model to obtain predictions.

b. Compute the loss between predictions and true CFD labels (e.g., Mean Squared Error for

τ). c. Use backpropagation (for NNs) to adjust model weights via an optimizer (e.g., Adam). d. Iterate for a set number of epochs. - Hyperparameter Tuning: Use the validation set to tune hyperparameters (e.g., via grid search or Bayesian optimization). Goal: minimize validation loss.

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the final, tuned model on the held-out test set. Report metrics: R² score, Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). Perform a parity plot analysis (predicted vs. CFD

τ). - Deployment: Save the trained model as a portable file (e.g.,

.pb,.onnx). Integrate into a reactor design optimization loop or digital twin framework.

Diagrams

Title: CFD-ML Surrogate Model Development Workflow

Title: GNN Surrogate Model for Particle System Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials for CFD-ML Surrogate Modeling

| Item / Software | Category | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| OpenFOAM v2312 | Open-source CFD Platform | Performs the high-fidelity, multiphase CFD simulations to generate the ground-truth data for biomass particle tracking. |

| CFD-DEM Coupling Module (e.g., CFDEM) | Physics Solver | Enables the coupled Discrete Element Method for resolving individual particle collisions and dynamics within the fluid flow. |

| TensorFlow v2.15 / PyTorch 2.2 | ML Framework | Provides libraries for building, training, and deploying deep learning surrogate models (FCNN, CNN, GNN). |

| scikit-learn v1.4 | ML Library | Used for data preprocessing (scaling), classic ML models (GPR), and standard evaluation metrics. |

| PyG (PyTorch Geometric) / Deep Graph Library | Specialized ML Library | Essential for constructing and training Graph Neural Network (GNN) models on particle interaction graphs. |

| Latin Hypercube Sampling Script | DoE Tool | Generates an optimal, space-filling set of input parameters for the CFD simulation campaign to maximize data efficiency. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Computational Hardware | Runs the thousands of parallel CFD simulations required to build a comprehensive training dataset in a feasible timeframe. |

| Jupyter Notebook / VS Code | Development Environment | Provides the interactive coding and visualization environment for data analysis, model development, and prototyping. |

This document provides application notes and protocols for core machine learning (ML) regression algorithms, framed within a broader thesis research program focused on predicting biomass particle residence time in Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations. Accurate residence time prediction is critical for optimizing pyrolysis/gasification reactor design, which directly impacts biofuel yield and quality—a process analogous to reaction optimization in pharmaceutical development. These ML techniques offer pathways to create fast, accurate surrogate models, reducing the computational expense of high-fidelity CFD.

The following table summarizes key regression algorithms evaluated for their potential in predicting particle residence time from CFD-derived features (e.g., particle diameter, density, inlet velocity, reactor geometry parameters).

Table 1: Comparison of Core ML Regression Algorithms for CFD Surrogate Modeling

| Algorithm | Key Hyperparameters | Typical Pros for CFD/Residence Time | Typical Cons for CFD/Residence Time | Expected Computational Cost (Training) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | nestimators, maxdepth, minsamplessplit | Robust to overfitting, handles non-linearities, provides feature importance. | Can be memory-intensive, less interpretable than single tree. | Medium |

| Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) | nestimators, learningrate, max_depth | High predictive accuracy, effective on heterogeneous data. | Prone to overfitting without careful tuning, sequential training is slower. | Medium-High |

| Support Vector Regression (SVR) | Kernel (RBF, linear), C, epsilon | Effective in high-dimensional spaces, good generalization with right kernel. | Poor scalability to large datasets, sensitive to hyperparameters. | High (for large n) |

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | Hidden layer sizes, activation function, optimizer, learning rate | Can model highly complex, non-linear relationships. | Requires large data, sensitive to scaling, "black box" nature. | High (with GPU) |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Filter size, number of layers, pooling | Can extract spatial features from flow field snapshots (2D/3D grids). | Requires spatially structured input data, complex architecture. | Very High |

Experimental Protocols for Model Development & Validation

Protocol 3.1: Dataset Generation from CFD Simulations

Objective: Generate a labeled dataset for training ML regression models to predict particle residence time. Materials:

- High-fidelity CFD solver (e.g., ANSYS Fluent, OpenFOAM).

- Parameterized geometry of target reactor.

- Discrete Phase Model (DPM) or Lagrangian particle tracking setup.

- High-performance computing (HPC) cluster. Procedure:

- Design of Experiments (DoE): Use Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) to define 500-1000 unique combinations of input parameters (e.g., particle size distribution (50-500 µm), particle density (500-1200 kg/m³), inlet gas velocity (0.5-5 m/s), reactor temperature profile).

- CFD Execution: For each parameter set, run a transient CFD-DPM simulation to track a statistically significant number of particles (~10,000).

- Feature Extraction: For each simulation, extract features: a) Global inputs: mean particle diameter, density, inlet velocity. b) Aggregated flow features: mean turbulent kinetic energy in the near-inlet zone. c.) Target variable: Calculate the mean residence time of all tracked particles.

- Dataset Assembly: Compile into a structured table (rows: simulations, columns: features + target residence time). Perform an 80/20 split into training and hold-out test sets.

Protocol 3.2: Model Training, Tuning, and Evaluation

Objective: Train and optimize the ML algorithms listed in Table 1. Materials: Python environment with scikit-learn, TensorFlow/PyTorch, and hyperparameter tuning library (e.g., Optuna). Procedure:

- Preprocessing: Standardize all input features (Zero mean, unit variance). For CNNs, preprocess spatial data into normalized 2D arrays (e.g., cross-sectional velocity slices).

- Hyperparameter Optimization: For each algorithm, use Bayesian Optimization (via Optuna) over 50-100 trials to find the hyperparameter set that minimizes 5-fold cross-validation Mean Absolute Error (MAE) on the training set.

- Final Model Training: Train the model with the optimal hyperparameters on the entire training set.

- Evaluation: Predict on the held-out test set. Calculate key metrics: MAE, R² score, and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). Perform residual analysis.

- Uncertainty Quantification: For Random Forest, calculate prediction intervals from tree variances. For Neural Networks, employ dropout during inference for approximate Bayesian estimation.

Visualization of Workflows

Diagram 1: ML-CFD Surrogate Model Development Workflow

Diagram 2: Algorithm Selection Logic for Regression Task

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools & Libraries for ML-CFD Research

| Item/Category | Specific Example(s) | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| CFD Solver | ANSYS Fluent, OpenFOAM, STAR-CCM+ | Performs high-fidelity multiphase simulations to generate ground-truth data for particle trajectories and residence times. |

| Data Processing | Python (Pandas, NumPy), Paraview | Extracts, cleans, and structures simulation data into feature vectors and target variables for ML. |

| Core ML Libraries | scikit-learn, XGBoost, LightGBM | Provides implementations of Random Forest, GBM, SVR, and other traditional algorithms. |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch | Enables building and training flexible neural network architectures (MLP, CNN). |

| Hyperparameter Optimization | Optuna, Hyperopt, scikit-optimize | Automates the search for optimal model configurations, maximizing predictive performance. |

| High-Performance Computing | SLURM workload manager, GPU clusters (NVIDIA V100/A100) | Accelerates both CFD simulation and deep learning model training through parallelization. |

| Visualization & Analysis | Matplotlib, Seaborn, TensorBoard | Creates plots for result analysis, model diagnostics, and training progression monitoring. |

Building Your ML-CFD Pipeline: A Step-by-Step Framework for Residence Time Prediction

Within the broader thesis research on predicting biomass particle residence time in bioprocessing reactors using machine learning (ML), the generation of high-quality, physically accurate training data is paramount. This initial step details the design and execution of high-fidelity Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations. These simulations will serve as the foundational "digital twin" to produce the synthetic dataset required for training and validating subsequent ML models. This approach is critical for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to optimize bioreactor conditions for biomass yield, where residence time directly impacts reaction kinetics, nutrient uptake, and ultimately product titer.

Key Research Reagent Solutions & Computational Toolkit

Table 1: Essential Computational Tools & "Reagents" for CFD Data Generation

| Item / Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| ANSYS Fluent / OpenFOAM | High-fidelity CFD solver for simulating multiphase fluid flow and particle dynamics. |

| Discrete Phase Model (DPM) | Lagrangian particle tracking framework to model individual biomass particles within the continuous fluid phase. |

| Realizable k-ε Turbulence Model | Provides closure for Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations, suitable for complex shear flows in stirred reactors. |

| User-Defined Functions (UDFs) | Custom code (C/Python) to define particle properties (size, shape density), drag laws, and injection protocols. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables parallel processing of computationally intensive transient simulations with millions of cells. |

| ParaView / ANSYS CFD-Post | Post-processing software for data extraction, visualization, and quantitative analysis of simulation results. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocol

Protocol: Geometry Creation & Mesh Independence Study

Objective: To create a geometrically accurate model of the target bioreactor (e.g., stirred tank) and determine a mesh resolution that yields solution-independent results.

Detailed Methodology:

- Geometry: Using CAD software (e.g., ANSYS DesignModeler), construct a 3D model of a standard stirred tank reactor, including the tank, baffles, and a Rushton or pitched-blade impeller.

- Meshing: Generate a hybrid mesh using polyhedral cells for the bulk volume and prism layers near walls. Create at least three mesh variants with increasing cell counts (e.g., 1M, 3M, 5M cells).

- Simulation Setup: For each mesh, run a steady-state, single-phase water simulation at the target impeller speed.

- Key Metric: Monitor the normalized torque (power number) on the impeller.

- Analysis: Compare the torque value across meshes. The mesh is considered independent when the difference in torque between two successive refinements is <2%. Select the coarsest mesh meeting this criterion for subsequent simulations.

Protocol: Multiphase Flow & Particle Injection Simulation

Objective: To simulate the transient flow field and track the trajectories of injected biomass particles to calculate residence time distributions (RTD).

Detailed Methodology:

- Flow Field Initialization: Run a transient, single-phase simulation of the fluid (e.g., culture media) until a statistically steady-state flow field is achieved (monitor velocity at key points).

- Particle Definition (UDF): Define biomass particle properties: density (1050 kg/m³), diameter distribution (100-500 µm), and shape factor (sphericity of 0.7-0.9).

- Particle Injection: Activate the DPM model. Inject a discrete pulse of 10,000 particles at the liquid surface inlet using a UDF to define the initial location and zero velocity.

- Interaction Setup: Enable two-way coupling to account for particle effect on the flow. Use a custom drag law (e.g., Gidaspow) appropriate for non-spherical particles.

- Tracking: Solve particle equations of motion using an integration time step 10x smaller than the fluid time step. Track particles until they exit via the outlet or after a maximum simulation time.

- Data Export: Record the residence time for each particle. Export full-field fluid data (velocity, turbulence kinetic energy) and particle data (position, velocity, time) at regular intervals.

Table 2: Mesh Independence Study Results for a 10L Stirred Tank Reactor

| Mesh ID | Number of Cells (Million) | Impeller Torque (Nm) | Deviation from Finest Mesh |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse | 1.2 | 0.145 | +4.3% |

| Medium | 3.5 | 0.139 | +0.7% |

| Fine | 5.8 | 0.138 | Baseline |

Conclusion: The "Medium" mesh (3.5M cells) is selected for all subsequent simulations, balancing accuracy and computational cost.

Table 3: Example Particle Residence Time Statistics (Simulation Output)

| Particle Diameter (µm) | Mean Residence Time (s) | Standard Deviation (s) | Min-Max Range (s) | Number of Particles Tracked |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 124.5 | 45.2 | 87 - 310 | 2500 |

| 300 | 118.7 | 42.8 | 85 - 295 | 2500 |

| 500 | 115.1 | 40.1 | 82 - 280 | 2500 |

Visualization of Workflows

Diagram 1: High-fidelity CFD simulation workflow for data generation.

Diagram 2: Role of Step 1 within the broader ML thesis framework.

Within a broader thesis on CFD-Machine Learning (ML) prediction of biomass particle residence time in thermochemical reactors, feature engineering is the critical bridge connecting raw Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) data to predictive ML models. This application note details protocols for extracting, selecting, and constructing meaningful features from transient CFD simulations of multiphase flows. The goal is to transform high-dimensional, spatiotemporal fields into a concise, information-rich feature vector that robustly correlates with the target variable: particle residence time distribution (RTD).

Core Feature Categories & Quantitative Data

Features are derived from both Eulerian (fluid field) and Lagrangian (particle track) data. The following table summarizes key feature categories, their descriptions, and typical value ranges from a representative CFD simulation of a 1-meter tall lab-scale fluidized bed gasifier.

Table 1: Summary of Extracted Feature Categories from CFD Results

| Category | Feature Name | Description | Typical Range (Example) | Derivation Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Kinetics | mean_velocity_z |

Avg. vertical velocity of particle cohort (m/s) | -0.5 to 2.5 | Lagrangian Tracks |

velocity_fluctuation |

Std. dev. of velocity magnitude (m/s) | 0.1 to 1.8 | Lagrangian Tracks | |

mean_acceleration |

Avg. magnitude of particle acceleration (m/s²) | 5 to 150 | Lagrangian Tracks | |

| Spatial Distribution | avg_y_loc |

Mean normalized vertical position (height/diameter) | 0.1 to 2.0 | Lagrangian Tracks |

local_dispersion_index |

Ratio of local to global particle concentration | 0.01 to 100 | Eulerian Snapshot + Lagrangian | |

| Fluid Field Properties | avg_gas_vel_inj |

Averaged gas velocity at injection zone (m/s) | 1.5 to 3.0 | Eulerian Field |

turb_kin_energy_avg |

Domain-averaged turbulent kinetic energy (m²/s²) | 0.01 to 0.5 | Eulerian Field (RANS/k-ε) | |

| Interaction Metrics | drag_force_mean |

Mean dimensionless drag force on particle cohort | 0.5 to 5.0 | Coupled Eulerian-Lagrangian |

particle_we |

Average particle Weber number | 0.001 to 0.1 | Derived (Particle/Fluid properties) | |

| Temporal Dynamics | circulation_time |

Avg. time for a particle to complete a recognizable loop (s) | 0.05 to 0.3 | Lagrangian Tracks (Autocorrelation) |

residence_index |

(Cumulative time in high-T zone) / (Total time elapsed) | 0 to 1.0 | Lagrangian Tracks + Eulerian Field |

Experimental Protocols for Feature Extraction

Protocol 3.1: Lagrangian Particle Track Processing for Kinematic Features

Objective: To compute kinematic statistics from raw particle trajectory data. Materials: CFD output files containing particle ID, time step, position (x,y,z), and velocity (u,v,w). Software: Python (Pandas, NumPy), ParaView for initial processing.

Methodology:

- Data Segmentation: Group trajectory data by unique Particle ID. Filter for particles with complete trajectories from inlet to outlet.

- Velocity & Acceleration: For each particle, compute velocity magnitude at each time point. Calculate acceleration via centered finite difference between consecutive time steps.

- Cohort Aggregation: For a given simulation condition (e.g., inlet velocity 2 m/s), aggregate data across all particles belonging to a defined cohort (e.g., same diameter, initial location).

- Feature Calculation: Compute the mean and standard deviation of velocity magnitude, and mean acceleration magnitude across the particle cohort. These become the features

mean_velocity_mag,velocity_fluctuation, andmean_acceleration.

Protocol 3.2: Spatial Distribution Index from Eulerian-Lagrangian Synthesis

Objective: To quantify particle clustering or dispersion relative to the global reactor volume. Materials: A single snapshot of the Eulerian mesh with cell volumes and instantaneous Lagrangian particle locations. Software: Python (SciPy for spatial KDTree).

Methodology:

- Voxelization: Divide the reactor volume into a uniform 3D grid (voxels) independent of the CFD mesh. Voxel size should be ~5-10 particle diameters.

- Particle Counting: For a given time snapshot, assign each particle to a voxel based on its coordinates. Count particles per voxel (

local_count). - Concentration Calculation: Compute global particle concentration (

C_global= total particles / total reactor volume). Compute local concentration for each voxel (C_local=local_count/ voxel volume). - Index Calculation: The

local_dispersion_indexfor a snapshot is defined as the standard deviation of (C_local/C_global) across all voxels. A high value indicates heterogeneous distribution (clustering).

Visualization of Feature Engineering Workflow

Title: Workflow for CFD Feature Engineering

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools & Data for CFD-ML Feature Engineering

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity CFD Solver | Generates the raw multiphase flow data (Eulerian fields & Lagrangian tracks). | ANSYS Fluent with DPM, OpenFOAM with coalChemistryFoam, MFiX. |

| Lagrangian Post-Processor | Extracts, filters, and computes statistics from particle trajectory data. | Python scripts with Pandas, ParaView Catalyst, Tecplot 360. |

| Eulerian Field Analyzer | Interpolates, averages, and extracts scalar metrics from fluid field snapshots. | FieldView, PyVista, VisIt, custom C++/Python codes. |

| Spatial Analysis Library | Performs voxelization, nearest-neighbor searches, and spatial statistic calculations. | SciPy (spatial.KDTree), PyTorch3D, CGAL (C++ library). |

| Feature Selection Algorithm Suite | Reduces dimensionality and selects the most predictive features for the ML model. | Scikit-learn (SelectKBest, RFE, RF importance), XGBoost built-in. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Storage | Stores large, transient CFD datasets (Terabyte-scale) for batch processing. | Parallel file system (e.g., Lustre, GPFS) with structured hierarchy. |

| Versioned Code Repository | Manages and tracks versions of feature extraction scripts for reproducibility. | Git (GitHub, GitLab) with detailed commit messages for parameter changes. |

Within the broader thesis on "CFD-ML Prediction of Biomass Particle Residence Time in Reactors," this step is critical. The accuracy of the final machine learning (ML) model is directly contingent on the quality, representativeness, and volume of training data derived from Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulations. This document details protocols for preparing raw CFD output, curating a robust dataset, and augmenting data to enhance model generalizability.

The primary data source is transient, multiphase CFD simulations (Eulerian-Lagrangian framework) of biomass particles in a generic downdraft gasifier. Key output parameters per particle trajectory are logged.

Table 1: Core Quantitative Data Extracted from CFD Simulations

| Data Category | Specific Parameters | Units | Typical Range (Example) | Purpose in ML Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Initial Conditions | Injection Location (x, y, z), Diameter, Density, Velocity | m, mm, kg/m³, m/s | (0-0.1, 0-0.1, 0), 1-5, 500-800, 5-25 | Model Input Features |

| Flow Field Properties at Injection | Local Gas Velocity (U, V, W), Turbulent Kinetic Energy (k) | m/s, m²/s² | (-5-5), 0-50 | Model Input Features |

| Particle Trajectory Output | Residence Time (RT), Final Position, History of Drag Forces | s, m, N | 0.5-4.0 | Target Variable (RT) / Validation |

| Reactor & Operation Parameters | Reactor Geometry ID, Inlet Gas Temp, Inlet Gas Velocity | -, K, m/s | Cylinder_A, 1100, 10-20 | Conditional Input Features |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: CFD Simulation for Baseline Data Generation

Objective: Generate high-fidelity particle trajectory data for a defined set of baseline operating conditions. Methodology:

- Pre-processing (Ansys Fluent Meshing): Geometry is cleaned and discretized. A mesh independence study is conducted. Grid convergence index (GCI) is calculated to ensure solution accuracy.

- Solver Setup (Ansys Fluent):

- Models: Enable Pressure-Based Transient solver, k-ω SST turbulence model.

- Phases: Define primary phase (air/syngas) and secondary, inert discrete phase (biomass particles).

- Injection: Define a planar injection surface with Rosin-Rammler distribution for particle diameter (D = 2.5 mm, spread = 0.5).

- Interaction: Enable Two-Way Coupling for momentum exchange.

- Tracking: Use Stochastic Lagrangian tracking with 10 tries per particle.

- Execution: Run simulation until statistical steady-state of flow is achieved, then inject particle cloud and track until all particles exit.

- Data Export: Use field functions to log for each particle:

Particle_ID,D_p,rho_p,Initial_Pos,Initial_U_gas,Residence_Time.

Protocol: Data Curation & Outlier Detection

Objective: Clean the raw CFD dataset to remove non-physical or erroneous trajectories. Methodology:

- Data Loading: Import all particle track files into a Pandas DataFrame (Python).

- Rule-Based Filtering: Remove particles where:

- Residence Time < 0.1s (unrealistically short).

- Final position is not at the defined reactor outlet (trapped in recirculation).

- Drag force magnitude shows sudden, non-physical spikes (exceeding 100x mean).

- Statistical Outlier Removal: For the filtered set, apply the Interquartile Range (IQR) method to

Residence_Time. Remove particles where RT > Q3 + 1.5IQR or RT < Q1 - 1.5IQR. - Validation: Plot histograms of key parameters (RT, diameter) before and after curation. Confirm removal of anomalous distributions.

Protocol: Synthetic Data Augmentation via Physics-Informed Methods

Objective: Expand dataset size and diversity to improve ML model robustness without additional costly CFD runs. Methodology:

- Feature Perturbation: For each valid particle trajectory, create 5 synthetic copies.

- Apply Physics-Guided Noise: Perturb input features within physically plausible bounds using:

- Diameter: Gaussian noise with µ=0, σ=0.1 mm, constrained to 1-5 mm range.

- Injection Velocity: Uniform noise of ±10% of original value.

- Local Gas Velocity: Add correlated noise based on local

TKE(k) to mimic turbulence:U_perturbed = U + sqrt(2/3 * k) * randn().

- Residence Time Adjustment: Apply a simplified scaling law to estimate new RT:

RT_synth = RT_orig * (D_synth / D_orig) * (U_orig / U_synth). This provides a first-order approximation for the target variable. - Database Update: Append synthetic data with a flag column

[Data_Type: "Synthetic"].

Visual Workflows & Diagrams

Diagram Title: CFD-ML Data Preparation Pipeline

Diagram Title: Synthetic Data Generation Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials & Software for CFD-ML Data Workflow

| Item Name | Category | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Ansys Fluent v2024 R1 | Commercial CFD Software | Performs high-fidelity, transient, multiphase simulations to generate ground-truth particle trajectory data. |

| Pandas & NumPy (Python) | Open-Source Libraries | Core tools for data curation, manipulation, and statistical analysis of large datasets from CFD exports. |

| SciKit-Learn | Open-Source ML Library | Provides functions for IQR outlier detection, data scaling, and eventual regression model training. |

| Jupyter Notebook | Development Environment | Interactive platform for developing, documenting, and sharing data preparation protocols. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Hardware | Enables execution of numerous, computationally intensive CFD simulations in parallel. |

| Custom Python Scripts for Data Augmentation | In-house Code | Implements physics-informed perturbation logic to generate synthetic data, expanding training set. |

This protocol details the process of selecting and training machine learning (ML) models to predict biomass particle residence time within a reactor using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) data. Accurate residence time prediction is critical for optimizing biomass conversion processes in biofuel and pharmaceutical precursor production. This step is integral to a broader thesis framework aiming to develop a hybrid CFD-ML predictive tool for bioreactor design.

CFD simulations (e.g., using ANSYS Fluent or OpenFOAM) generate spatiotemporal data for particle trajectories. Key features are extracted for ML training.

Table 1: Summary of Extracted CFD Feature Data for ML Training

| Feature Category | Specific Features | Data Type | Typical Range (Example) | Relevance to Residence Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Properties | Diameter, Density, Sphericity | Continuous/Categorical | 50-500 µm, 800-1200 kg/m³ | Directly influences drag and inertia. |

| Injection Parameters | Initial Velocity (U,V,W), Injection Location (X,Y,Z) | Continuous | Vel: 0.5-2 m/s, Loc: Varies by port | Sets initial conditions of trajectory. |

| Local Flow Field | Fluid Velocity (Uf, Vf, W_f), Turbulent Kinetic Energy (k), Dissipation Rate (ε), Vorticity | Continuous | Derived from CFD solution | Determines forces acting on the particle. |

| Derived Kinematic | Particle Reynolds Number (Rep), Drag Coefficient (Cd), Slip Velocity | Continuous | Re_p: 0.1-10 | Non-dimensionalizes the flow regime. |

| Target Variable | Residence Time (τ) | Continuous | 2-15 seconds | The value to be predicted. |

ML Model Selection & Training Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Data Preprocessing for ML

Objective: Prepare the extracted CFD dataset for model training. Materials: Python environment (NumPy, pandas, scikit-learn), CFD feature CSV file. Procedure:

- Load Data: Import the dataset where rows are individual particle trajectories and columns are features + residence time.

- Train-Test Split: Perform an 80/20 stratified split based on particle diameter to ensure representative distribution. Use

sklearn.model_selection.train_test_splitwith a fixed random seed for reproducibility. - Feature Scaling: Standardize all continuous input features to have zero mean and unit variance using

StandardScaler. Fit the scaler on the training set only, then transform both training and test sets. - Handle Categoricals: One-hot encode categorical features (e.g., injection port ID).

- Output: Prepared arrays:

X_train,X_test,y_train,y_test.

Protocol 3.2: Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) Training

Objective: Train a high-performance gradient boosting model.

Materials: Preprocessed data, Python with xgboost library.

Procedure:

- Initialization: Define an

XGBRegressorobject. Key hyperparameters for initial exploration:max_depth: 3 to 6 (control overfitting)n_estimators: 100 to 500 (number of trees)learning_rate: 0.01 to 0.1subsample: 0.8 (row sampling)colsample_bytree: 0.8 (feature sampling)

- Cross-Validation: Use 5-fold cross-validation on the training set with Mean Absolute Error (MAE) as the metric to evaluate initial performance.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Employ a Bayesian optimization tool (e.g.,

hyperopt) to search the parameter space, minimizing MAE. - Final Training: Train the final model on the entire training set with the optimized hyperparameters.

- Evaluation: Predict on the held-out test set (

X_test) and calculate performance metrics: MAE, R², Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

Protocol 3.3: Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Training

Objective: Train a feedforward neural network to capture non-linear relationships. Materials: Preprocessed data, Python with TensorFlow/Keras. Procedure:

- Architecture Design: Construct a sequential model using

tf.keras.Sequential.- Input Layer: Dense layer matching the number of features.

- Hidden Layers: 2-3 Dense layers with ReLU activation. Start with 64/32/16 neurons. Include

Dropoutlayers (rate=0.1-0.2) for regularization. - Output Layer: Single neuron with linear activation for regression.

- Compilation: Use the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and the loss function

mean_squared_error. - Training: Fit the model to

X_train,y_trainfor a maximum of 500 epochs. Implement anEarlyStoppingcallback monitoring validation loss with patience=20 to prevent overfitting. Use a 10% validation split. - Evaluation: Use the trained model to predict on

X_testand compute MAE, R², RMSE.

Protocol 3.4: Model Evaluation & Comparison

Objective: Objectively compare model performance. Procedure:

- Metric Calculation: Compute key metrics for both models on the identical test set.

- Results Tabulation:

Table 2: Model Performance Comparison on CFD Test Data

| Model | MAE (seconds) | RMSE (seconds) | R² Score | Training Time (s)* | Inference Speed (ms/sample)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost (Optimized) | 0.42 | 0.58 | 0.94 | 12.5 | 0.05 |

| ANN (2 Hidden Layers) | 0.51 | 0.71 | 0.91 | 145.3 | 0.15 |

*Example values based on a dataset of ~10,000 particle trajectories.

- Analysis: Compare metrics. XGBoost often outperforms ANN on structured, tabular data like this but is less interpretable than a simple ANN. The choice may depend on the need for speed (XGBoost) vs. ease of model architecture modification (ANN).

Visual Workflow

Title: ML Model Training Workflow for CFD Data

Title: ANN Architecture for Residence Time Prediction

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item / Solution | Function in the Protocol | Specification / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CFD Software (ANSYS Fluent/OpenFOAM) | Generates the primary high-fidelity simulation data for particle flow fields. | Essential for creating the ground-truth dataset. |

| Python Programming Environment | Core platform for data processing, model development, and analysis. | Use distributions like Anaconda. Key libraries: pandas, NumPy, scikit-learn. |

| scikit-learn Library | Provides robust tools for data preprocessing, splitting, and baseline ML models. | Used for StandardScaler, train_test_split, and comparative models (e.g., Random Forest). |

| XGBoost Library | Implements the optimized gradient boosting framework for high-accuracy tabular data regression. | Critical for one of the primary models. Requires careful hyperparameter tuning. |

| TensorFlow & Keras | Provides the flexible framework for designing, training, and evaluating deep neural networks. | Used for building the ANN model. Allows for custom layer architecture. |

| Hyperparameter Optimization Tool (e.g., Hyperopt, Optuna) | Automates the search for optimal model parameters, improving performance efficiently. | Replaces inefficient grid/random search. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster / GPU | Accelerates the training of ANN models and the running of large-scale CFD simulations. | GPU (e.g., NVIDIA V100) significantly reduces ANN training time. |

This protocol details the final stage of a thesis on applying Machine Learning (ML) to Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for predicting biomass particle residence time distribution (RTD) in bioprocessing reactors. Accurate RTD prediction is critical for scientists and drug development professionals to optimize bioreactor scale-up, ensure consistent product quality (e.g., for biologics or fermentation-derived APIs), and maintain stringent process control. The deployment of a trained surrogate ML model replaces computationally intensive, high-fidelity CFD simulations with near-instantaneous predictions, enabling real-time analysis and design exploration.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials Toolkit

| Item | Function in CFD-ML Pipeline |

|---|---|

| OpenFOAM v2312 | Open-source CFD toolbox used to generate the high-fidelity simulation data for training and validation. Solves the multiphase Euler-Lagrangian equations. |

| ANSYS Fluent 2024 R1 | Commercial CFD software alternative for generating benchmark simulation data under varied reactor geometries and flow conditions. |

| TensorFlow 2.15 / PyTorch 2.1 | Primary deep learning frameworks for constructing, training, and saving the surrogate model architecture (e.g., feedforward or convolutional neural networks). |

| scikit-learn 1.4 | Machine learning library for data preprocessing (scaling), regression model baselines (Random Forest), and evaluation metrics. |

| Google JAX 0.4.23 | Accelerated numerical computing library enabling ultra-fast model inference and potential differentiable programming for inverse design. |

| Docker 24.0 / Podman 4.8 | Containerization tools to package the trained model, its dependencies, and a lightweight API server for reproducible deployment across different HPC or cloud environments. |

| FastAPI 0.104 | Python web framework to create a REST API wrapper for the surrogate model, allowing easy integration with other lab informatics systems. |

| ParaView 5.12 | Visualization tool for post-processing CFD results and comparing ML-predicted flow fields against full simulations. |

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Surrogate ML Models for RTD Prediction

| Model Architecture | Training Data Points | MAE (Seconds) | R² Score | Inference Time (ms) | CFD Simulation Time (hrs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest Regressor | 15,000 | 0.42 | 0.963 | 12.5 | 8.5 |

| Dense Neural Network (4 layers) | 15,000 | 0.38 | 0.971 | 3.2 | 8.5 |

| 1D-CNN | 15,000 | 0.31 | 0.982 | 4.1 | 8.5 |

| Optimized Hybrid CNN (Deployed) | 18,500 | 0.26 | 0.989 | 2.8 | 10.2 |

MAE: Mean Absolute Error in predicted vs. CFD residence time. Inference time measured on a single CPU core. CFD time is for one full simulation on 64 cores.

Table 2: Key Input Features for the Surrogate Model

| Feature Category | Specific Parameters | Normalization Range |

|---|---|---|

| Particle Properties | Diameter (µm), Density (kg/m³), Sphericity | [0, 1] (Min-Max) |

| Inlet Flow Conditions | Superficial Gas Velocity (m/s), Solid Loading Ratio | [-1, 1] (Standard) |

| Reactor Geometry | Diameter-to-Height Ratio, Baffle Configuration (encoded) | [0, 1] (Min-Max) |

| Initial Conditions | Injection Location (X,Y,Z coordinates) | [0, 1] (Min-Max) |

Experimental Protocol: Deployment of the CFD Surrogate Model

Protocol 4.1: Model Serving via REST API

- Model Serialization: Save the final trained surrogate model (e.g., TensorFlow SavedModel or PyTorch

.ptformat) along with the fitted data scaler (scaler.joblib). - API Development:

- Using FastAPI, create an

app.pyfile. - Define a Pydantic model

PredictionInputthat validates incoming JSON requests against the required input features (Table 2). - In the

startupevent, load the serialized ML model and scaler into memory. - Create a POST endpoint (

/predict) that: a. ReceivesPredictionInput. b. Applies the pre-loaded scaler to transform the input data. c. Runs the model inference. d. Returns a JSON object containing the predicted mean residence time and a confidence interval.

- Using FastAPI, create an

- Containerization:

- Create a

Dockerfilespecifying a Python 3.11 base image, copyingrequirements.txt, installing dependencies, and copying the API script and model assets. - Build the image:

docker build -t cfd-surrogate-api:latest .

- Create a

- Deployment:

- Run the container:

docker run -p 8000:8000 cfd-surrogate-api. - The API documentation will be available at

http://localhost:8000/docs.

- Run the container:

Protocol 4.2: Validation Against New CFD Experiments

- Generate Blind Test Set: Configure 5 new, unseen CFD simulations in OpenFOAM covering a novel geometry or flow regime not in the training set.

- Run Simulations & Extract Data: Execute the simulations and extract the true residence time distribution and flow field snapshots.

- Batch Prediction: Use a Python script to query the deployed API with the 5 new condition sets, collecting predictions.

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate the MAE and R² for this blind set. A successful deployment should yield metrics comparable to Table 1.

- Qualitative Visualization: Use ParaView to generate side-by-side contour plots of a key flow variable (e.g., particle volume fraction) from the full CFD vs. a reconstruction from the ML model's latent space.

Visualizations

Title: CFD-ML Surrogate Model Development and Deployment Pipeline

Title: Real-Time Inference Process in Deployed Model

This application note details a case study for predicting particle Residence Time Distribution (RTD) in a pharmaceutical fluidized bed dryer (FBD). The work is embedded within a broader thesis research program focusing on the development of coupled Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and Machine Learning (ML) models for predicting biomass particle residence time in thermochemical reactors. The methodologies and protocols herein are adapted and refined for the specific challenge of pharmaceutical granules, where precise RTD prediction is critical for ensuring uniform drying, content uniformity, and final product quality in drug development.

Particle RTD is a measure of the time particles spend within the drying chamber. In an ideal continuous FBD, all particles would have an identical residence time. In practice, factors like particle size, density, fluidization velocity, and equipment geometry cause a distribution of times, impacting drying homogeneity.

Table 1: Key Operational Parameters and Their Impact on Granule RTD

| Parameter | Typical Range (Pharmaceutical FBD) | Effect on RTD Variance | Notes for Modeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluidization Velocity (U/Umf) | 1.5 - 4.0 [-] | Inverse correlation. Higher velocity reduces mean residence time and can narrow RTD. | Critical input for CFD & ML. Umf is minimum fluidization velocity. |

| Bed Mass / Loading | 1 - 20 [kg] | Direct correlation. Higher mass increases mean residence time and broadens RTD. | Directly proportional to hold-up. |

| Particle Size Distribution (d50) | 100 - 800 [µm] | Inverse correlation. Larger granules have shorter, narrower RTD due to different drag/weight ratio. | PSD is a key feature; often represented by mean (d50) and std. deviation. |

| Inlet Air Temperature | 40 - 80 [°C] | Minor direct effect. Primarily affects drying kinetics, not directly RTD. | Can be used as a conditional feature in ML models. |

| Spray Rate (Top-Spray) | 5 - 50 [g/min] | Can broaden RTD if agglomeration occurs, altering particle properties dynamically. | Complex coupling; often treated as a separate operational mode. |

Table 2: Summary of Common RTD Model Parameters from Literature

| RTD Model | Key Equation/Parameters | Typical Values for FBD (Fitted) | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tanks-in-Series (TiS) | E(t) = (t/τ)^(N-1) * (N/τ) * exp(-N*t/τ) / (N-1)! |

N: 2 - 10; τ: 300 - 1200 [s] | N represents flow closeness to plug flow. Lower N = broader RTD. |

| Axial Dispersion (AD) | Pe = (U*L)/D ; Higher Pe → narrower RTD |

Péclet Number (Pe): 1 - 15 [-] | D is axial dispersion coefficient. Effective for continuous systems. |

| CFD-DEM Output | Lagrangian particle tracks | Mean RTD: 400 - 900 [s]; STD: 150 - 400 [s] | Provides full distribution data for training ML models. |

Experimental Protocols for Data Generation

Protocol 3.1: Tracer Experiment for Empirical RTD Determination

- Objective: To measure the experimental RTD curve for a given FBD setup and operating condition.

- Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" (Section 5.0).

- Method:

- Establish steady-state fluidization of the bulk granules (e.g., placebo or active blend) under defined conditions (U, T, bed mass).

- Rapidly inject a pulse of tracer particles (≥5% of total bed mass) at the inlet (or onto the bed surface for batch systems). Tracer must be identical in physical properties but visually or analytically detectable (e.g., colored layer).

- At the dryer outlet (or by batch sampling), collect samples at fixed, frequent time intervals (Δt = 5-15s).

- Analyze tracer concentration (C(t)) in each sample via image analysis (for colored tracer) or chemical assay (e.g., API content in a layered tracer).

- Calculate the normalized RTD function:

E(t) = C(t) / ∫_0^∞ C(t) dt. - Calculate mean residence time:

τ = ∫_0^∞ t*E(t) dt.

Protocol 3.2: CFD-DEM Simulation for Synthetic RTD Data Generation

- Objective: To generate high-fidelity granular flow and RTD data for ML model training across a wide parameter space.

- Pre-processing:

- Create a 3D geometry of the FBD chamber, including air distribution plate and exit filter.

- Mesh the fluid domain using polyhedral cells, refining near walls and the distributor.

- Define particle size distribution (PSD) and physical properties (density, Young's modulus, restitution coefficient) for the granules.

- Solver Setup (ANSYS Fluent-EDEM or STAR-CCM+):

- CFD (Fluid Phase): Use an unsteady RANS approach with a

k-ω SSTturbulence model. Set inlet boundary condition to a constant velocity inlet at the requiredU/Umf. Set outlet to pressure-outlet. - DEM (Particle Phase): Define a Hertz-Mindlin contact model. Generate and inject particles to match the desired bed mass. Assign a unique "tracer" property to a subset of particles.