Optimizing Hybrid Renewable Systems: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Bioenergy Integration for a Sustainable Energy Future

This article provides a systematic evaluation of bioenergy system integration with complementary renewable energy sources, addressing critical gaps in current renewable energy research.

Optimizing Hybrid Renewable Systems: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Bioenergy Integration for a Sustainable Energy Future

Abstract

This article provides a systematic evaluation of bioenergy system integration with complementary renewable energy sources, addressing critical gaps in current renewable energy research. For researchers and scientists in drug development and biomedical fields, it explores how stable, bio-based power can enhance energy resilience for sensitive facilities. The analysis progresses from fundamental concepts and global status to methodological frameworks for system design, including AI-driven optimization and sequential modeling approaches. It addresses key technical and economic challenges in biomass supply chains, conversion technologies, and hybrid system operation, while presenting validation through techno-economic analysis and comparative case studies of real-world implementations. The synthesis offers actionable insights for developing reliable, integrated renewable energy systems capable of supporting energy-intensive research operations while advancing sustainability goals.

The Strategic Role of Bioenergy in the Global Renewable Ecosystem

Current Global Status and Deployment Trends of Bioenergy

Bioenergy, derived from organic materials, is a cornerstone of the global renewable energy landscape, playing a critical role in power generation, heat production, and transportation. As nations intensify efforts to meet carbon reduction targets and ensure energy security, understanding the current status and deployment trends of bioenergy systems is essential for researchers and scientists evaluating its integration with other renewable sources. This guide provides a comparative analysis of bioenergy technologies, supported by quantitative data and experimental methodologies, to inform strategic research and development in the field. The recent Belém 4x pledge by 23 countries at COP30 to quadruple sustainable fuel production and use by 2035 underscores the growing global commitment to scaling these technologies [1].

The bioenergy market has demonstrated robust growth, evolving from a niche renewable source to a significant component of the global energy portfolio. This expansion is driven by ambitious carbon reduction targets, increasing environmental concerns, and continuous advancements in conversion technologies [2] [3].

Table 1: Global Bioenergy Market Size and Growth Trends

| Metric | 2024 Status | 2025 Forecast | 2029 Forecast | CAGR (2025-2029) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Value | $296.09 billion [2] [3] | $320.81 - $323.44 billion [2] [3] | $465.22 - $473.49 billion [2] [3] | 9.7% - 10% [2] [3] |

| Biopower Capacity | 151 GW [4] | |||

| Bioelectricity Generation | 698 TWh [4] | |||

| Liquid Biofuel Production | ~192 billion liters [4] | |||

| Global Biogas Production | 1.76 EJ (2023) [4] |

The market is segmented by type, technology, and application, each with distinct characteristics and growth trajectories:

- By Type: The market comprises Biomass and Renewable Municipal Waste, Biogas, and Liquid Biofuels. Liquid biofuels, including bioethanol, biodiesel, and bio-jet fuel, dominated the transportation segment, accounting for 90% of renewable energy in transport and 4% of total transport energy use in 2024 [4] [2].

- By Technology: Key conversion technologies include Gasification, Fast Pyrolysis, and Fermentation. Technological advancements are focused on improving efficiency, yield, and sustainability [2] [3].

- By Application: Bioenergy is utilized for Power Generation, Heat Generation, and Transportation. In the heat sector, bioenergy is particularly dominant, accounting for 73% of global renewable heat production [4].

Regional Deployment Trends

Bioenergy adoption and growth potential vary significantly across regions, influenced by local resources, policy frameworks, and investment patterns.

Table 2: Regional Bioenergy Deployment and Focus Areas

| Region | Market Position & Growth | Key Focus Areas & Leaders |

|---|---|---|

| North America | Largest market in 2024 [2] [3] | Expansion in U.S. Midwest and Southeast integrating carbon capture [5]. |

| Asia-Pacific | Fastest-growing region [2] [3] | Biopower leadership by China (30% global output); Major investments in China, India, Japan [4]. |

| Europe | Mature market | Bioheat leader (75% global output); 60% global biogas investment in 2024 [4]. |

| Brazil & Latin America | Key emerging market [2] | Biofuels leadership (ethanol, biodiesel); COP30 host pushing global clean fuels pledge [4] [1]. |

Regional trends indicate a shift towards integrated systems and geographical expansion. Countries like India and China are scaling existing efforts, while other regions in Europe and Latin America are adopting more ambitious bioenergy programs [5].

Comparative Analysis of Bioenergy Pathways

Different bioenergy pathways offer distinct advantages and face unique challenges. A comparative analysis is crucial for evaluating their suitability for integration with other renewables.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Major Bioenergy Pathways

| Bioenergy Pathway | Technology Readiness & Typical Feedstock | Key Advantages | Primary Challenges | Sample Experimental Output/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biopower | Commercial / Biomass, Waste [2] | Grid stability; Baseload power [6] | Feedstock supply chain competition [5] | 698 TWh global generation (2024) [4] |

| Bioheat | Commercial / Biomass, Biogas [2] | High renewable heat share (73%) [4] | Dominates renewable heat (73% global share) [4] | |

| Liquid Biofuels (e.g., Biodiesel, SAF) | Commercial to Demonstration / Energy crops, Waste oils [2] [1] | High energy density; Drop-in for existing engines [1] | Cost premium; Feedstock sustainability [1] | 192B liters produced (2024); 90% renewable transport energy [4] |

| Biogas/Biomethane | Commercial / Organic waste, Agricultural residues [2] | Waste management; Grid injection [4] | 1.76 EJ production (2023); 4% capacity growth (2023) [4] | |

| BECCS (Bioenergy with Carbon Capture & Storage) | Demonstration / Biomass with CCS [6] [5] | Carbon-negative potential; Carbon credits [5] | High cost; System complexity [6] [5] |

Key Experimental Workflow for Bioenergy System Integration

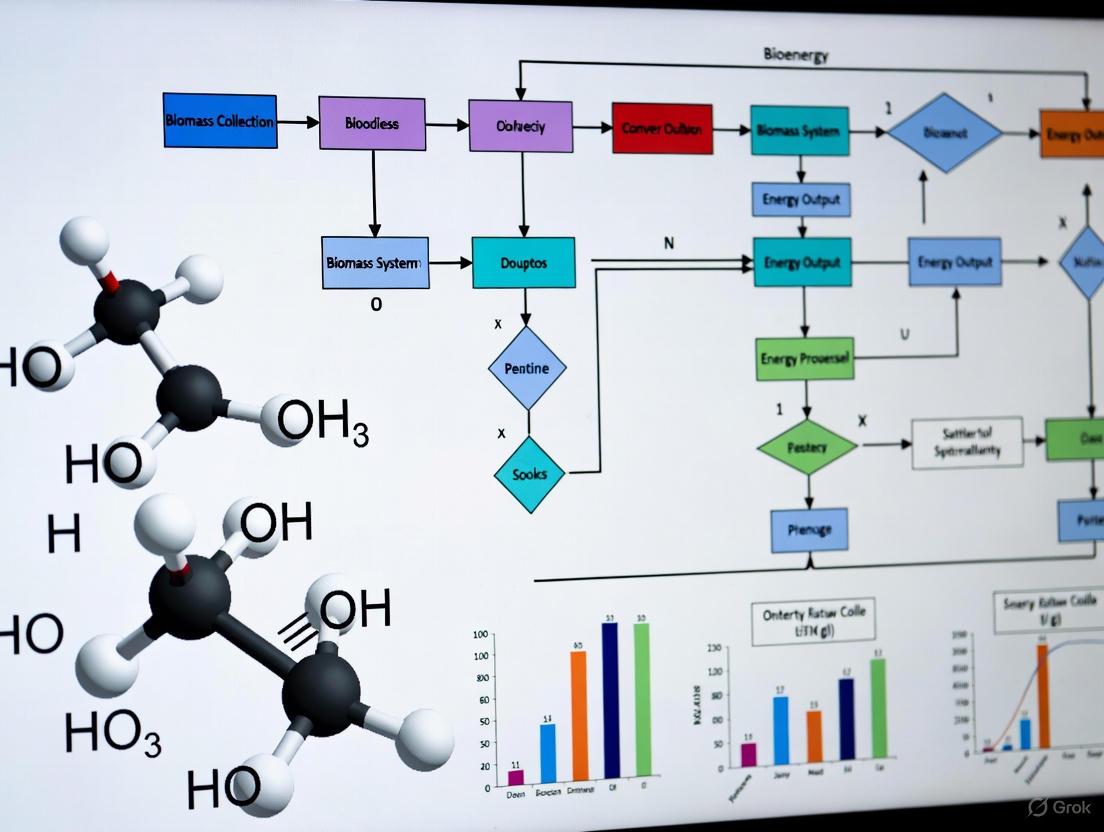

Evaluating bioenergy systems, particularly their integration with other renewables, requires a structured experimental and analytical workflow. The following diagram outlines a standard methodology for assessing technical and environmental performance.

Diagram 1: A generalized experimental workflow for bioenergy integration research.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducible and comparable results in bioenergy research, adherence to detailed experimental protocols is critical. The following methodologies are commonly employed across different bioenergy pathways.

Protocol for Biomass Gasification and Syngas Analysis

Objective: To convert solid biomass into syngas and evaluate its quality for power generation or biofuel synthesis [2].

- Feedstock Preparation:

- Drying: Reduce moisture content to below 15% using an oven at 105°C.

- Size Reduction: Mill biomass to a particle size of 0.5-2.0 mm to ensure efficient gasification.

- Proximate & Ultimate Analysis: Determine composition (volatiles, fixed carbon, ash) and elemental makeup (C, H, N, S) [2].

- Gasification Setup:

- Use a fluidized-bed or downdraft gasifier reactor.

- Set reactor temperature to 700-900°C, optimized for the specific feedstock.

- Introduce a controlled flow of gasifying agent (air, steam, or oxygen).

- Syngas Cleaning & Conditioning:

- Pass raw syngas through a cyclone for particulate removal.

- Utilize a series of scrubbers (e.g., water, organic) to remove tars and contaminants.

- Syngas Analysis:

- Analyze composition (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) using Gas Chromatography with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (GC-TCD).

- Calculate Lower Heating Value (LHV) of the syngas based on compositional data.

Protocol for Anaerobic Digestion and Biogas Yield Evaluation

Objective: To determine biogas and methane yield from organic waste via anaerobic digestion [2].

- Inoculum and Substrate Preparation:

- Acquire active anaerobic inoculum from an operational digester.

- Characterize substrate (e.g., food waste, agricultural residue) for total solids (TS) and volatile solids (VS).

- Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Test:

- Use multiple serum bottles (e.g., 500 mL) as batch reactors.

- Maintain a defined inoculum-to-substrate ratio (e.g., 2:1 on a VS basis).

- Flush headspace with nitrogen gas to ensure anaerobic conditions.

- Incubate bottles at mesophilic temperature (35±2°C) for 30-40 days.

- Biogas Monitoring and Measurement:

- Measure daily biogas production by water displacement or pressure sensors.

- Periodically analyze biogas composition for methane (CH₄) and carbon dioxide (CO₂) content using a gas chromatograph.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate cumulative methane yield (L CH₄/kg VS added).

- Compare experimental yields to theoretical BMP values.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful experimentation in bioenergy research relies on a suite of specialized reagents, catalysts, and materials.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioenergy Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Common Specification/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Inoculum | Provides microbial consortium for biogas production from organic matter. | Sourced from active wastewater or agricultural digesters [2]. |

| Enzymes (Cellulases, Hemicellulases) | Catalyzes hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars. | Novozymes products; Specific activity: ≥ 500 U/g [2]. |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts (e.g., Zeolites, Ni-based) | Accelerates thermochemical reactions (e.g., cracking, reforming) to improve bio-oil yield/quality. | Sigma-Aldrich; ZSM-5 zeolite, Ni/Al₂O₃ [2]. |

| Analytical Standards (for GC/MS) | Enables identification and quantification of compounds in bio-oils, syngas, and biogas. | Supelco; Mixed alcohol standard, Syngas standard mix [2]. |

| Nutrient Media for Fermentation | Supports growth of microbes (eyeast, bacteria) for biofuel production (e.g., ethanol). | Yeast Extract-Peptone-Dextrose (YPD) for yeast [2]. |

Emerging Trends and Future Research Directions

The bioenergy landscape is rapidly evolving, shaped by technological innovation and strategic policy drivers. Several key trends are defining the future research agenda for system integration.

Key Innovation Trends

- Integration with Carbon Capture (BECCS): There is a significant push towards coupling bioenergy facilities with carbon capture and storage. This creates a carbon-negative energy system, which is increasingly valued in carbon credit markets and is a focus for new projects in the U.S. Midwest and Southeast [5].

- Diversification of Feedstock: To meet rising demand and address sustainability concerns, research is expanding into non-traditional biomass sources. These include landscaping waste, municipal solid waste, and industrial byproducts, which help create a circular economy for waste materials [5].

- Advanced Biofuel Production: Major companies are launching new biofuel products, such as Be8 BeVant, which serve as "drop-in" solutions for decarbonizing transport without requiring new infrastructure [2] [3]. Furthermore, the Belém 4x pledge from COP30 is accelerating global momentum for Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) and other clean fuels [1].

- Hybrid Renewable Systems: Bioenergy is no longer operating in isolation. A major trend is its integration into interconnected systems that combine stable biomass power with variable sources like solar and wind. This hybrid approach ensures a reliable and affordable energy supply [5].

- Technological Advancements: Continuous innovation is improving the efficiency and economics of bioenergy. Key areas include advanced gasification techniques, the development of biorefineries for producing multiple value-added products, and the use of AI and digital twin technology for optimizing plant operations and grid management [2] [6].

System Integration Logic

The future of energy systems lies in the seamless integration of various renewable sources. The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of an integrated bioenergy hybrid system, highlighting the role of bioenergy in providing stability and carbon management.

Diagram 2: The logic of a hybrid renewable energy system integrating bioenergy with carbon management.

Bioenergy remains a vital and dynamically evolving component of the global renewable energy portfolio. Its unique ability to provide dispatchable power, renewable heat, and liquid fuels for hard-to-electrify sectors makes it indispensable for a comprehensive energy transition. Current trends point towards greater integration—both with other renewables like solar and wind to form more resilient hybrid systems, and with carbon capture technologies to deliver carbon-negative energy solutions. For researchers and scientists, the focus must now be on innovating to reduce costs, expanding sustainable feedstock bases, and developing sophisticated system-level models that optimize the role of bioenergy within a fully decarbonized energy system. The strong global policy momentum, exemplified by the COP30 pledge, ensures that bioenergy will continue to be a critical area for research, investment, and deployment in the coming decade.

The global transition towards renewable energy is fundamentally challenging the operation and stability of power grids. Traditional grids were designed around large, centralized fossil fuel and nuclear power plants, which provide inherent stability through the synchronous rotation of their massive turbines and generators. This mechanical inertia dampens frequency fluctuations, ensuring a steady 50/60 Hz alternating current [7]. However, the increasing dominance of variable renewable energy (VRE) sources like solar and wind, which are inverter-based resources (IBRs), is reducing this system inertia. Solar and wind power are inherently non-dispatchable; their output depends on weather conditions and cannot be reliably summoned to meet demand peaks. This intermittency can lead to grid instability, voltage fluctuations, and frequency deviations, necessitating a critical search for renewable solutions that can provide dispatchable power—electricity that can be supplied on demand [8].

Within this context, bioenergy's unique value proposition comes to the fore. Unlike other mainstream renewables, bioenergy derived from biomass (organic material such as wood, agricultural residues, and waste) can offer dispatchability and grid-supporting services, positioning it as a crucial stabilizer for future high-renewable grids. This guide objectively compares bioenergy's technical performance against other renewable alternatives, providing researchers and scientists with experimental data and methodologies to evaluate its role in integrated renewable energy systems.

Comparative Analysis of Renewable Energy Attributes

The following table provides a high-level comparison of key attributes across different renewable energy technologies, highlighting bioenergy's distinct characteristics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Renewable Energy Technologies for Grid Integration

| Technology | Dispatchability | Inherent Grid Stability Services | Typical Capacity Factor | Role in Grid Management |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solar PV (Utility-scale) | Non-dispatchable (Intermittent) | Limited (requires advanced inverters for synthetic inertia) [7] | 15-25% | Energy generation during daylight hours |

| Wind Power | Non-dispatchable (Intermittent) | Limited (semi-dispatchable with storage; can provide synthetic inertia) [7] | 30-50% | Energy generation, often at night |

| Hydropower | Dispatchable (with reservoir) | High (provides inertia, frequency regulation) [8] | 40-60% | Baseload, peak power, and frequency control |

| Biomass Power | Fully Dispatchable [8] | High (synchronous generator can provide inertia, frequency regulation) | 70-85% [9] | Baseload or peaking power, grid stability |

| Biogas & Bioenergy with Storage | Fully Dispatchable & Flexible | Very High (can mimic conventional plants; fast-responding) | >80% | On-demand power, ancillary services, black start capability |

A second critical dimension for comparison is the economic and environmental performance, which is vital for system planning and lifecycle analysis.

Table 2: Economic and Environmental Performance Metrics

| Parameter | Solar PV | Wind | Biomass Gasification | Notes & Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) | ~$0.03-0.06/kWh | ~$0.02-0.05/kWh | ~$0.07-0.14/kWh [9] | Costs are highly location-specific. |

| Carbon Emissions (kg CO₂eq/GJ) | ~0 (operational) | ~0 (operational) | 30-50 [9] | Biomass is often considered carbon-neutral over its lifecycle. |

| Conversion Efficiency | 15-22% | 30-45% | 70-85% (Gasification) [9] | Biomass efficiency varies significantly by technology. |

| Land Use Impact | High | Medium | Medium | Biomass requires land for feedstock production. |

| Key Grid Benefit | Low-cost energy | Low-cost energy | Dispatchability & Stability |

Experimental Validation: Methodologies and Data

Robust experimental data is essential to validate the performance claims of integrated bioenergy systems. The following protocols and results from field studies provide evidence for bioenergy's role in grid stability.

Case Study 1: Hybrid System Performance on Pelee Island

A comprehensive study on Pelee Island, Canada, designed and optimized a Hybrid Energy System (HES) for a remote community with an unreliable grid [10].

- Experimental Protocol: Researchers modeled a system integrating photovoltaic (PV) arrays with tracking, a biogas gasifier, a diesel generator, lithium-ion battery storage, and a grid connection. The system was simulated under two distinct dispatch strategies: Load Following (LF), where generation matches the real-time load, and Cycle Charging (CC), where generators run at full capacity to charge batteries when load is low. Eight different configurations were analyzed based on key performance metrics.

- Key Performance Metrics (KPIs):

- Net Present Cost (NPC): The total cost of installing and operating the system over its lifetime.

- Cost of Electricity (COE): The per-unit cost of the generated electricity.

- Renewable Fraction (RF): The percentage of energy derived from renewable sources.

- Annual Unmet Load: The total energy demand not served by the system.

- Results and Analysis: The optimal configuration was a CC-based system with VCA tracking, comprising a 776 kW PV array and 73 battery units. It achieved an NPC of $1.6 million, a COE of $0.083/kWh, and a high Renewable Fraction of 78.7%, with a nearly negligible unmet load of 54.3 kWh per year [10]. A competing LF strategy achieved an even higher RF of 86.3% and lower emissions, but at a higher NPC, demonstrating the trade-offs in system design. This experiment conclusively showed that a bioenergy (biogas)-hybrid system can reliably meet nearly all of a community's energy needs with a high penetration of renewables, with bioenergy providing the dispatchable backbone.

While not exclusively about bioenergy, a landmark field study by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) demonstrated that inverter-based resources can provide critical grid-stability services traditionally supplied by conventional thermal plants [7].

- Experimental Protocol: NREL, in collaboration with First Solar, equipped the 141-MW Luz del Norte solar power plant in Chile with advanced grid-forming inverter controls. The objective was to enable the plant to participate in Chile's ancillary services market by providing frequency regulation and fast-response reserves. A key challenge was accurately predicting the plant's available power, which was solved using a real-time estimation formula that used a subset of the plant's inverters as a reference [7].

- Key Findings: The successful implementation allowed the Luz del Norte plant to become the first known utility-scale solar plant to participate in the full range of fast-response grid reliability services [7]. This proves that with the correct control algorithms, renewable plants can be active participants in grid stability. For bioenergy, this is equally significant. A biomass plant equipped with similar advanced inverters can not only provide the inherent inertia of its synchronous generator but can also enhance its response with synthetic inertia, making it a doubly potent tool for grid operators.

The logical relationship and workflow between different renewable technologies and the grid's stability needs can be summarized in the following diagram:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

For scientists developing and testing advanced bioenergy systems, particularly those focused on conversion efficiency and integration, the following reagents, catalysts, and materials are critical.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced Bioenergy Systems

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nanocatalysts (e.g., ZnO, TiO₂, Ni) | Enhance the efficiency and yield of biofuel production processes like gasification and pyrolysis by lowering activation energies and improving selectivity [9]. | Cutting-edge research into reducing energy input and improving the quality of syngas and biofuels. |

| Nanomembranes | Used in biogas upgrading and purification processes to selectively separate CO₂ and other contaminants from methane, improving fuel quality [9]. | Critical for producing pipeline-quality renewable natural gas (RNG) from anaerobic digestion. |

| Advanced Gasification Systems | Core conversion technology that thermochemically transforms biomass into syngas (CO+H₂) for power generation or biofuel synthesis [11] [9]. | The focus of efforts to achieve high conversion efficiencies (70-85%) and low emissions. |

| Lithium-Ion Battery Storage | Provides short-duration energy storage to manage instantaneous fluctuations, often paired with bioenergy for a complete dispatchable solution [10]. | A key component in hybrid renewable energy systems (HRES) for balancing intra-hour variability. |

| Grid-Forming Inverters (I³) | Advanced power electronics that allow renewable resources to set grid voltage and frequency, rather than just following it [7]. | Enables bioenergy and other IBRs to operate in grids with very low or no conventional inertia. |

The experimental data and comparative analysis confirm that bioenergy's unique value proposition in a renewable-heavy grid is unequivocally its dispatchability and capacity to enhance grid stability. While solar and wind provide the least-cost energy, their intermittency poses integration challenges. Bioenergy, particularly through technologies like gasification and when configured in hybrid systems with storage, provides a reliable, flexible, and firm power source that can operate as baseload or be ramped to meet peak demand.

For researchers and policymakers, the imperative is clear: future energy system models and real-world deployments must leverage the complementary strengths of different renewables. The path forward involves:

- Optimizing Hybrid Systems: Further research into control strategies, like the Cycle Charging and Load Following models, is needed to optimally manage multi-technology systems comprising bioenergy, solar, wind, and storage [10].

- Advancing Catalysts and Digestion Processes: Continuous improvement of nanocatalysts and anaerobic digestion efficiency is vital to boost bioenergy's economic competitiveness and sustainability profile [9].

- Developing Market Structures: As demonstrated in Chile, electricity markets must be reformed to value and compensate dispatchability and ancillary services from renewable sources like bioenergy, encouraging investment in these critical attributes [7].

In conclusion, bioenergy is not merely an alternative source of electrons but a foundational pillar for building a resilient, secure, and 100% renewable energy grid.

The global transition to renewable energy is fundamentally challenged by the variable and intermittent nature of dominant sources like solar and wind power. Solar energy generation is limited to daylight hours and adversely affected by weather conditions, while wind power fluctuates with changing wind speeds and patterns [12] [13]. This intermittency disrupts conventional grid operation methods designed for controllable generators, creating obstacles for maintaining the precise balance between electricity supply and demand required for grid stability [12]. As renewable penetration increases globally, developing effective solutions to manage this variability becomes increasingly critical for deep decarbonization of power systems.

Bioenergy, derived from organic biomass sources, presents a unique solution within the renewable portfolio through its inherent dispatchability. Unlike solar and wind resources which are dependent on weather conditions, bioenergy can be generated on-demand, making it a controllable and reliable power source [13]. This complementary attribute allows bioenergy to compensate for the gaps in solar and wind generation, thereby ensuring a more stable and consistent electricity supply. Within a diversified renewable energy system, bioenergy serves as a flexible backbone that can be ramped up during periods of low solar and wind availability, effectively supporting higher penetration of variable renewables while maintaining grid reliability [14].

Table: Fundamental Characteristics of Renewable Energy Sources

| Energy Source | Intermittency/Dispatchability | Capacity Factor | Key Variability Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solar PV | Intermittent (Variable) | 10-30% [13] | Diurnal cycle, weather conditions, seasonality |

| Wind Power | Intermittent (Variable) | 25-50% [13] | Weather patterns, wind speed, time of day |

| Bioenergy | Dispatchable (Controllable) | High (can operate as baseload) [13] | Biomass feedstock availability and supply chain |

| Hydropower | Dispatchable (with reservoir) [13] | Varies by site and design | Seasonal water availability, precipitation patterns |

Technical Comparison: Operational Attributes Across Renewable Technologies

The operational characteristics of renewable energy technologies largely determine their role within an integrated energy system. Variable Renewable Energy (VRE) sources like solar and wind are non-dispatchable due to their fluctuating nature, making them challenging to integrate at high penetration levels without complementary technologies [13]. In contrast, bioenergy systems utilizing biomass, biogas, or biofuels are classified as dispatchable renewables because they incorporate stored potential energy in the form of biomass feedstocks, enabling power generation on demand rather than being dependent on weather conditions [13].

This fundamental distinction in dispatchability gives bioenergy several complementary advantages for grid integration. Bioenergy can provide firm capacity guaranteed to be available during commitment periods, unlike solar and wind which require capacity credit calculations that decrease as their concentration on the grid rises [13]. While solar and wind generation profiles are determined by environmental conditions, bioenergy plants can be operated according to grid demand patterns, making them particularly valuable for load-following and peak shaving applications when combined with storage technologies [14].

The predictability profile of each technology further highlights their complementary nature. Solar power exhibits predictable diurnal patterns but remains vulnerable to short-term variability from cloud cover, while wind power, though increasingly forecastable, still presents significant prediction challenges, especially across single-region grids [13]. Bioenergy faces no such weather-dependent unpredictability, though its reliability depends on feedstock supply chains and conversion technology availability [14]. When combined in hybrid systems, these technologies create a more resilient and reliable renewable energy portfolio that mitigates the limitations of individual components.

Table: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Renewable Energy Technologies

| Performance Metric | Solar PV | Wind Power | Bioenergy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Annual Capacity Factor | 10-20% (fixed), up to 30% (tracking) [13] | 25-50% (higher offshore) [13] | Can exceed 80% (comparable to conventional fuels) |

| Dispatchability | Non-dispatchable (can be curtailed) [13] | Non-dispatchable (can be curtailed) [13] | Fully dispatchable [13] |

| Capacity Credit at Low Penetration | Approximately equal to capacity factor [13] | Approximately equal to capacity factor [13] | High (near nameplate capacity) |

| Primary Variability Factors | Diurnal cycle, cloud cover, seasonality | Weather systems, diurnal patterns, turbulence | Feedstock availability, conversion technology reliability |

Hybridization Mechanisms: System Integration and Operational Synergies

The integration of bioenergy with solar and wind resources creates hybrid systems that deliver enhanced reliability and performance through multiple complementary mechanisms. These hybridization strategies leverage the respective strengths of each technology to overcome individual limitations, particularly addressing the intermittency challenges of solar and wind power.

Direct Hybrid Renewable-Biomass Systems

The most straightforward approach combines bioenergy with photovoltaic solar or wind energy in integrated facilities [14]. In these configurations, renewable sources generate electricity when weather conditions are favorable, while biomass serves as backup during periods of low renewable output [14]. This arrangement is particularly valuable in isolated grids or areas with limited transmission infrastructure, as it ensures a continuous power supply without relying on fossil fuels. The biomass component can utilize local organic waste as feedstock, enhancing sustainability while providing dispatchable power that compensates for solar and wind intermittency.

Sector Coupling and Storage Integration

Beyond direct electrical generation, bioenergy enables sector coupling through green hydrogen production and thermal energy storage. During periods of high solar and wind generation, surplus electricity can be used to produce green hydrogen via electrolysis [14]. This hydrogen can subsequently be used in combination with biomass systems or stored for later power generation. Additionally, concentrated solar power (CSP) hybridized with biomass can utilize molten salt thermal storage systems to extend operational hours and ensure continuous electricity production [14]. These integrated storage approaches significantly enhance the utilization rate of variable renewable resources while maintaining grid stability.

Grid-Scale Firming and Balancing

At the grid level, bioenergy provides essential firming capacity that enables higher penetration of variable renewables. Bioenergy power plants can operate as flexible dispatchable resources that ramp up during net demand peaks when solar and wind generation is insufficient [13]. This capability reduces the need for curtailment during periods of excess VRE generation while ensuring reliability during periods of low renewable availability. The 2025 Biomass Energy Innovation & Development Forum highlighted that bioenergy must "evolve beyond traditional uses into multi-sectoral applications" through "systemic integration of bioenergy with other renewables" to meet climate goals [15]. This grid-stabilizing function makes bioenergy particularly valuable as regions work toward achieving high renewable penetration targets.

Experimental Framework: Methodologies for Assessing Hybrid System Performance

Research on bioenergy integration with variable renewables employs specialized methodologies to quantify complementarity benefits and system performance. These experimental approaches combine modeling, optimization, and empirical analysis to evaluate how bioenergy compensates for solar and wind intermittency across different contexts.

Multi-Objective Optimization Framework

Advanced research employs multi-objective optimization frameworks to identify cost-effective integration strategies that balance investment costs, renewable penetration, and power curtailment [16]. This methodology typically involves developing models that simultaneously optimize multiple variables including solar-wind deployment ratios, storage capacity sizing, and bioenergy dispatch schedules. The approach uses high-resolution spatial (e.g., 500-meter) and temporal (e.g., hourly) data to comprehensively evaluate resource potential based on exploitability, accessibility, and interconnectability criteria [16]. These models typically minimize total system costs while meeting reliability constraints, often revealing that strategic bioenergy deployment reduces storage requirements and transmission upgrades compared to solar-wind-only systems.

Resource Complementarity Analysis

Complementarity between energy sources is quantified using statistical approaches that assess both energy potential and intermittency patterns. Research methodologies analyze historical weather data (often 30-year hourly reanalysis datasets) to identify locations where bioenergy availability negatively correlates with solar and wind resources [17]. This involves calculating complementarity indices that consider both the amplitude and timing of resource availability, going beyond simple correlation coefficients to capture the relationship between variability and energy output [17]. The analysis produces Pareto-front solutions that identify optimal site combinations where bioenergy naturally compensates for solar and wind intermittency, significantly improving overall system reliability.

Hybrid System Modeling and Simulation

Performance evaluation of specific hybrid configurations utilizes detailed simulation models that replicate the operational dynamics of combined bioenergy-solar-wind systems. These models incorporate:

- Resource variability at high temporal resolution (hourly or sub-hourly)

- Technology-specific performance parameters (conversion efficiencies, ramp rates, minimum operating levels)

- Load profiles representing different demand patterns

- Storage system dynamics for both electrical and thermal storage

- Economic parameters including capital and operational expenditures

Simulations typically compare key performance indicators like reliability metrics (loss of load probability, equivalent availability factor), economic viability (levelized cost of energy, net present value), and renewability penetration (percentage of demand met by renewables) between hybrid systems and single-resource scenarios [17] [16]. This methodology provides quantitative evidence of how bioenergy integration improves system performance while reducing costs associated with intermittency management.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Hybrid Renewable-Bioenergy Systems

| Research Tool/Resource | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Resolution Weather Reanalysis Data | Provides historical solar irradiance, wind speed, and temperature data for complementarity analysis and system modeling | 30-year hourly data at 500-meter spatial resolution [16] |

| Resource Assessment Software | Evaluates solar, wind, and biomass potential based on geographical and technical constraints | Spatial filtering capabilities incorporating land use, environmental constraints, and infrastructure availability [16] |

| Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithms | Identifies optimal hybrid system configurations balancing cost, reliability, and renewable penetration | Pareto-front optimization using median (energy) and median absolute difference (intermittency) metrics [17] |

| Power System Simulation Platforms | Models hourly system operation under various generation and demand scenarios | Integration of unit commitment, economic dispatch, and storage operation algorithms with renewable generation profiles [16] |

| Life Cycle Assessment Tools | Quantifies environmental impacts of hybrid systems including carbon footprint and resource utilization | Database incorporating biomass feedstock emissions, manufacturing impacts, and land use changes [14] |

The integration of bioenergy with solar and wind resources represents a critical strategy for achieving high renewable penetration while maintaining grid reliability. Bioenergy's dispatchable nature directly compensates for the inherent intermittency of solar and wind power, creating complementary systems that enhance overall energy security and sustainability [13] [14]. This hybridization approach maximizes the utilization of existing infrastructure, reduces curtailment of variable renewables, and provides a pathway for decarbonizing sectors that are difficult to electrify directly [15] [14].

Future research should focus on optimizing hybrid system configurations for specific regional contexts, developing advanced control strategies for seamless integration, and improving the economic viability of bioenergy through technological innovation and supply chain optimization. As the global energy transition accelerates, leveraging the complementary attributes of diverse renewable sources will be essential for building resilient, low-carbon energy systems capable of meeting future electricity demands while addressing the urgent challenges of climate change [16].

Biomass resources, derived from organic materials, are pivotal in the global transition to sustainable energy systems. As the world seeks to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and fossil fuel dependence, biomass offers a renewable alternative for power generation, heat, and transportation fuels [18]. The integration of bioenergy with other renewable sources is critical for developing resilient, low-carbon energy grids. This guide focuses on three principal biomass categories, as defined by the U.S. Department of Energy: agricultural residues, forestry waste, and dedicated energy crops [19] [20]. These feedstocks are characterized as abundant, domestic resources that can be converted into biofuels, biopower, and bioproducts, thereby supporting energy security and agricultural and forest-product industries [20]. Evaluating their comparative performance is essential for optimizing bioenergy system integration within a broader renewable energy framework.

Resource Characteristics and Global Potential

The three key biomass resources possess distinct physical and chemical properties, cultivation requirements, and spatial distribution patterns, which directly influence their suitability for various energy conversion pathways and their overall potential for system integration.

Agricultural Residues: These are the non-edible parts of crops left after harvest, such as corn stover (stalks, leaves, husks), wheat straw, oat straw, barley straw, sorghum stubble, and rice straw [19]. They are abundant, widely distributed, and represent a low-cost feedstock without competing directly with food production. A global assessment estimates the current sustainable energy potential from agricultural residues at nearly 50 EJ per year, with significant potential for growth [21]. Specific studies, such as one on Chad, highlight the concentration of potential in specific residues like sorghum stalks (56.50%), rice (17.72%), and maize stalks (13.31%), with a total calculated energy potential of approximately 252.5 terajoules (TJ) from about 18.1 kilotons of residues [22].

Forestry Waste: This category includes forest residues left after timber harvesting (limbs, tops, culled trees) and wood processing residues (sawdust, bark) [19]. Utilizing this biomass aids in wildfire prevention, habitat restoration, and reduces the catastrophic effects of wildfires by removing excess woody biomass from forest floors [23]. The U.S. government's Billion Ton Report underscores the vast potential of waste forestry biomass as a substantial bioenergy source [23]. The global potential from forestry residues is a major component of the overall 50 EJ per year from all residues [21].

Dedicated Energy Crops: These are non-food crops grown specifically for bioenergy production on marginal land unsuitable for traditional agriculture. They are categorized as:

- Herbaceous energy crops: Perennial grasses like switchgrass and miscanthus, harvested annually after taking 2-3 years to reach full productivity [19].

- Short-rotation woody crops: Fast-growing hardwood trees such as hybrid poplar and hybrid willow, harvested within 5 to 8 years of planting [19]. These crops can improve soil and water quality, enhance wildlife habitat, and diversify farm income [19]. Their cultivation is a long-term strategy for biomass supply, with potential to significantly contribute to the projected global biomass market, which is expected to exceed USD 210.5 billion by 2030 [18].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Biomass Feedstocks

| Characteristic | Agricultural Residues | Forestry Waste | Dedicated Energy Crops |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Examples | Corn stover, wheat straw, rice straw [19] | Logging residues, sawdust, bark [19] | Switchgrass, miscanthus, hybrid poplar [19] |

| Key Advantage | Abundant byproduct, no dedicated land need [19] | Wildfire risk reduction, waste valorization [23] | High yield potential, grown on marginal land [19] |

| Supply Chain Model | Distributed, seasonal collection | Centralized at processing mills or dispersed in forests [19] | Dedicated cultivation, scheduled harvests |

| Global Energy Potential (Current) | Major component of ~50 EJ/yr from residues [21] | Major component of ~50 EJ/yr from residues [21] | Expanding role in future supply [19] |

| Notable Regional Potential | Chad: 252.5 TJ from major crops [22]; U.S., China, India are top producers [21] | U.S. (Billion Ton Report), California for wildfire management [23] | Global, suited for marginal lands in many regions [19] |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

A objective comparison of biomass resources requires evaluating their energy conversion efficiency, environmental impact, and economic viability. These performance metrics are critical for researchers to assess integration strategies and technology pathways.

Conversion Efficiency and Economic Metrics

The efficiency of converting raw biomass into usable energy varies significantly based on the feedstock properties and conversion technology. Advanced thermochemical processes like gasification can achieve higher efficiencies. Economically, the costs are influenced by feedstock availability, pre-processing needs, and transportation logistics. The capital intensity of the industry remains a barrier to rapid development, prompting a search for innovative, data-driven pathways to improve financial outcomes [23].

Table 2: Energy Conversion and Economic Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | Agricultural Residues | Forestry Waste | Dedicated Energy Crops | Experimental Context & Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conversion Efficiency | Varies with technology: Anaerobic Digestion with CHP: 30-40% [24] | Varies with technology: Direct combustion: 20-25%; Advanced gasification: up to 40% [24] | Varies with technology; generally high due to uniform properties | Efficiency ranges for different conversion pathways [24]. |

| Installation Cost (Utility Scale) | N/A | ~$3-4 per watt [24] | N/A | Comparative cost analysis for power generation [24]. |

| Operating Cost | N/A | $0.02-0.05 per kWh [24] | N/A | Fuel, transport, and labor costs for biomass plants [24]. |

| Key Cost Driver | Collection, transport, and storage logistics [18] | Harvesting, transport, and processing [23] [18] | Cultivation, land, and water use [24] | Supply chain and feedstock management costs [23] [18]. |

Environmental Impact and Sustainability

The environmental profile of biomass energy is a subject of extensive research, particularly regarding lifecycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and other air pollutants. The carbon neutrality of biomass is debated due to the "carbon debt" from harvesting and the time required for regrowth to reabsorb emitted CO₂ [24].

Table 3: Environmental Impact and Sustainability Indicators

| Environmental Metric | Agricultural Residues | Forestry Waste | Dedicated Energy Crops | Experimental Context & Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifecycle GHG Emissions | Lower when sourced sustainably | 230-350 g CO₂eq/kWh [24] | Highly variable; can be low | IPCC AR6 data on biomass emissions from combustion [24]. |

| Air Pollutant Concerns | Particulate matter from open burning | PM2.5, Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) from combustion [24] | Generally lower from dedicated conversion | Emissions from combustion processes [24]. |

| Primary Sustainability Challenge | Soil health and nutrient balance | Forest ecosystem management and carbon debt [24] | Land-use change and water consumption | Key challenges in biomass energy optimization [18] [24]. |

| Co-benefits | Waste management, additional farmer income [19] | Wildfire prevention, forest restoration [23] | Soil improvement, biodiversity on marginal land [19] | Ecosystem services beyond energy production [23] [19]. |

Experimental Protocols for Biomass Analysis

For researchers to replicate studies and validate data, standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for key analyses relevant to biomass feedstock evaluation.

Protocol for Determining Calorific Value

The Higher Heating Value (HHV) is a critical parameter for assessing the energy content of biomass.

- Sample Preparation: Feedstock is air-dried, ground to a particle size of <0.5 mm, and oven-dried at 105°C until constant mass to determine moisture content.

- Instrumentation: Use an isoperibol oxygen bomb calorimeter (e.g., Parr 6100), calibrated with a certified benzoic acid standard.

- Procedure: Precisely weigh approximately 1.0 g of dried sample into a combustion capsule. Assemble the bomb with 30 atm of pure oxygen. Submerge the bomb in a known mass of water in the calorimeter jacket. Ignite the sample and record the maximum temperature change of the water.

- Calculation: The HHV (in MJ/kg) is calculated based on the temperature rise, the heat capacity of the system, and the sample mass, with corrections for fuse wire combustion and acid formation.

Protocol for Feedstock Flexibility in Gasification

This protocol tests the suitability of diverse feedstocks for thermochemical conversion.

- Feedstock Preparation: Multiple biomass types (e.g., wood chips, sugarcane leaf, corncob) are processed to a uniform particle size (e.g., 2-10 mm) and dried to a moisture content of <15%.

- Reactor System: A dual fluidized bed (DFB) gasification system, such as the 3.8 MWth prototype used in Nong Bua, Thailand, is utilized [25].

- Experimental Run: For each feedstock, the gasifier is operated at a steady state (e.g., 850°C). The produced syngas is sampled and analyzed for composition (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) using gas chromatography. Tar content is measured via standard tar protocols.

- Data Analysis: Key performance indicators include cold gas efficiency, carbon conversion rate, and syngas lower heating value, which are compared across the different feedstocks [25].

Diagram 1: Biomass Characterization Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key experimental steps for analyzing biomass properties, from sample preparation to final reporting.

Research Reagent and Material Solutions

A successful biomass research program relies on specialized reagents, materials, and analytical tools. The following table details essential components of the researcher's toolkit.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biomass Energy Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Bomb Calorimeter | Determines the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of solid biomass fuels. | Must be calibrated with certified benzoic acid standards for accurate results. |

| Dual Fluidized Bed (DFB) Gasifier | Converts solid biomass into syngas for flexibility and efficiency testing. | Pilot-scale systems (e.g., 3.8 MWth) allow for testing with various feedstocks like wood chips and agricultural residues [25]. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Analyzes the composition (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) of syngas produced from gasification or pyrolysis. | Equipped with thermal conductivity (TCD) and flame ionization (FID) detectors. |

| Anaerobic Digestion Setup | Produces biogas (methane) from wet feedstocks like manure and food waste through microbial action. | System includes temperature-controlled reactors and gas collection bags for yield measurement. |

| Fast Pyrolysis Unit | Converts biomass into pyrolysis oil (FPBO) for advanced biofuel production. | Commercial scale units (e.g., 25 MWth) can process ~5 t/h of wood [25]. |

Integration with Broader Renewable Energy Systems

The true potential of biomass is realized when it is strategically integrated with other renewable energy sources. Its unique ability to provide dispatchable, baseload power complements intermittent sources like solar and wind, enhancing grid stability and enabling deeper decarbonization [24] [25].

Diagram 2: Biomass Integration Pathway for Grid Stability. This diagram illustrates how biomass-derived energy carriers complement variable renewables to ensure a reliable energy supply.

Innovative best practices demonstrate this integration synergy. For instance, the Werlte e-gas plant in Germany uses CO₂ from biogas and renewable hydrogen (from solar/wind electrolysis) to produce synthetic natural gas, enabling seasonal energy storage [25]. Another example is the use of biomass hybrid dryers that combine solar collectors with heat pumps, flexibly switching between energy sources based on availability and cost [25]. Furthermore, biomass gasification produces syngas that can be flexibly upgraded into liquid fuels (e.g., e-methanol for shipping) or used for power generation, providing stability to grids with high renewable penetration [25]. These pathways position biomass not merely as a standalone energy source but as a foundational pillar for an integrated, resilient, and decarbonized energy system.

Policy Frameworks and Global Initiatives Driving Integrated Renewable Development

The global energy landscape is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from a paradigm where renewable energy was a peripheral contributor to one where it forms the central pillar of electricity generation. As of 2025, renewable energy has surpassed coal in global electricity generation for the first time, marking a crucial turning point for the global power system [26]. This milestone is not merely symbolic; it reflects a fundamental shift in the economic, technological, and policy foundations of the energy sector. The imperative for integrating diverse renewable sources—solar, wind, bioenergy, and others—is driven by the recognition that a diversified, resilient, and interconnected renewable energy system offers greater reliability, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability than any single technology alone.

Integrated renewable development refers to the strategic combination of multiple renewable energy technologies, supported by enabling infrastructure such as energy storage and modernized grids, to create systems that are more than the sum of their parts. This approach is essential for addressing the intermittency challenges inherent in individual variable renewables like solar and wind power. The business case for integration is stronger than ever, with 91% of new renewable power projects commissioned in 2024 proving more cost-effective than the cheapest fossil fuel alternatives [27]. Solar photovoltaics (PV) were, on average, 41% cheaper than the lowest-cost fossil fuel alternatives, while onshore wind projects were 53% cheaper, creating compelling economic arguments for policymakers and investors alike [27].

This comparison guide examines the policy frameworks and global initiatives that are accelerating the development of integrated renewable energy systems, with particular attention to research and implementation methodologies. By objectively analyzing the performance of various policy approaches and their impacts on system integration, we provide researchers and development professionals with the analytical tools needed to advance this critical field.

Global Policy Landscape and Renewable Energy Targets

International Commitments and Regional Initiatives

The international policy landscape for renewable energy is fundamentally shaped by the Paris Agreement and reinforced by subsequent commitments, including the historic agreement at COP28 to "transition away from fossil fuels" and triple global renewable energy capacity by 2030 [28]. This high-level ambition has catalyzed a wave of policy action at regional, national, and sub-national levels, creating a complex ecosystem of overlapping and mutually reinforcing initiatives.

The European Union has emerged as a particularly sophisticated regulatory environment through its "Fit for 55" package and REPowerEU plan, which are being actively implemented with the EU already surpassing key interim renewable energy milestones in 2024 [28]. A cornerstone of the EU's approach is the Revised Renewable Energy Directive, which includes provisions for simplifying permitting processes and designating "renewables acceleration areas" – specific zones where projects benefit from streamlined procedures while still respecting environmental standards [29]. These designations, required by February 2026, represent a strategic spatial planning approach to renewable energy deployment that balances acceleration with environmental considerations.

In Asia, China remains the undisputed leader in renewable capacity additions, while India, Japan, and South Korea are scaling up both utility-scale and distributed renewable projects through evolving legal frameworks [28]. The United States presents a more complex picture, where federal policy has become less predictable, though state-level initiatives and the residual effects of the Inflation Reduction Act continue to influence development [30]. This geographic diversity in policy approaches creates natural experiments from which researchers can draw valuable insights about what works, where, and why.

National Policy Frameworks Across Key Markets

Table 1: Renewable Energy Policy Frameworks in Major Markets (2025)

| Country/Region | Primary Policy Lever | Integration Focus | Notable Initiatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Union | Regulatory Streamlining | Cross-border grids & hybrid systems | Renewable Acceleration Areas, Revised RED, REPowerEU |

| China | Central Planning & Targets | Ultra-high voltage transmission | 14th Five-Year Plan, Renewable Portfolio Standard |

| India | Competitive Auctions | Solar-wind-storage hybrids | National Wind-Solar Hybrid Policy, Green Energy Corridor |

| United States | Tax Incentives (partial) | Technology innovation | Energy Earthshots, R-STEP program [31] |

| Japan | Feed-in Tariffs/Auctions | Offshore wind & hydrogen | Basic Energy Plan, Amendment of Renewable Energy Act |

| Australia | State-level Mechanisms | Grid modernization & DER | State-level FITs, Renewable Energy Target |

| Southeast Asia | Power Development Plans | Regional power trade | ASEAN Power Grid, National Renewable Energy Programs |

The "Asia Pacific Renewable Energy Policy Handbook 2025" provides comprehensive coverage of policy frameworks across 17 major countries in the region, revealing distinctive approaches to integration [32]. India has pioneered auctions for projects that combine solar, wind, and storage, driving integrated development through market mechanisms [33]. The National Wind-Solar Hybrid Policy explicitly encourages the combination of technologies to optimize utilization of transmission infrastructure and land resources [32].

China's 14th Five-Year Plan continues to emphasize the development of an integrated renewable energy system, supported by ultra-high voltage transmission lines to connect resource-rich interior regions with coastal demand centers [32]. The implementation of a Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) creates compliance incentives for utilities to diversify their renewable portfolios beyond any single technology [32].

The evolving policy landscape reveals an important trend: the most effective frameworks are those that not only promote individual renewable technologies but explicitly encourage their integration through hybrid projects, shared infrastructure, and complementary technology combinations.

Quantitative Analysis of Renewable Energy Deployment and Costs

Global Investment Flows and Capacity Additions

The effectiveness of policy frameworks is ultimately reflected in investment patterns and deployment outcomes. Global investment in renewable energy continues to break records, reaching $386 billion in the first half of 2025 alone—a 10% increase from the same period in the previous year [33]. This investment surge demonstrates robust confidence in the sector despite policy uncertainties in some markets.

Table 2: Global Renewable Energy Investment and Cost Metrics (2024-2025)

| Metric | 2024 Status | 2025 Trends | Key Regional Variations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Renewable Investment (H1) | $351 billion (2024) | $386 billion (2025) | EU up 63%; US down 36% [33] |

| Solar PV Cost (avg. LCOE) | $0.043/kWh | Further reductions in Asia | 41% cheaper than fossils [27] |

| Onshore Wind Cost (avg. LCOE) | $0.034/kWh | Stable with slight declines | 53% cheaper than fossils [27] |

| Battery Storage Cost | $192/kWh (utility) | 93% decline since 2010 | Continued innovation driving costs down [27] |

| Small-scale Solar Investment | Significant growth | Surprise winner in H1 2025 | Outpacing utility-scale in some markets [33] |

| Fossil Fuel Avoidance | $467 billion (annual) | Similar scale expected | Result of existing renewable capacity [27] |

A notable shift in investment patterns emerged in 2025, with signs of capital reallocation from the US to Europe [33]. This movement appears responsive to policy signals, with US investment in renewables down 36% in the first half of the year compared to the second half of 2024, while EU-27 investment was up 63% over the same period [33]. These fluctuations highlight the sensitivity of renewable energy investment to stable and supportive policy environments.

Technology-specific investment trends reveal the growing importance of distributed energy resources, with small-scale solar emerging as a "surprise winner" in the first half of 2025 [33]. This trend reflects both the maturation of business models for distributed generation and policy support for consumer-led energy transitions, such as net metering and feed-in tariffs for small-scale systems.

Regional Performance and Emerging Leaders

The geographic distribution of renewable energy deployment reveals striking patterns of leadership and emergence. China added more renewable energy generation than the rest of the world combined, leading to a 2% drop in its use of fossil fuels in the first half of 2025 compared with the same period in 2024 [26]. This achievement reflects the effectiveness of China's comprehensive policy framework, which combines ambitious targets, substantial state investment, and manufacturing support.

India has emerged as a particularly impressive case study, growing its renewable energy by more than three times its electricity demand increase, causing coal and gas use to fall by 3.1% and 34% respectively in the first half of 2025 [26]. This demonstrates how proactive policy can decouple energy growth from fossil fuel consumption.

Regional variations in cost structures highlight the impact of financing conditions on project viability. While the physical installation costs for renewable projects are becoming increasingly consistent globally, the cost of capital varies dramatically—from as low as 3.8% in Europe to 12% in Africa [27]. This differential explains why similar technologies can produce significantly different levelized costs of electricity in different markets, pointing to the critical importance of de-risking instruments and supportive financial frameworks in developing economies.

Methodological Framework for Evaluating Integrated Renewable Energy Policies

Experimental Protocol for Policy Assessment

Evaluating the effectiveness of policy frameworks for integrated renewable energy development requires a systematic methodological approach. The following experimental protocol provides researchers with a standardized framework for comparative policy analysis:

Phase 1: Policy Mapping and Categorization

- Identify and catalog all renewable energy policies, regulations, and incentives in the target jurisdiction

- Categorize policies by type (regulatory, fiscal, informational), scope (national, regional, local), and technology specificity

- Map the policy ecosystem to identify synergies, gaps, and contradictions using network analysis techniques

- Document historical policy evolution to understand path dependencies and reform sequences

Phase 2: Metric Selection and Data Collection

- Select appropriate quantitative and qualitative metrics for evaluation, including:

- Capacity addition rates by technology

- Integration indicators (curtailment rates, hybrid project penetration)

- Cost metrics (LCOE, grid integration costs)

- Investment flows (source, destination, instrument type)

- Establish baseline measurements and control groups where possible

- Collect data from government reports, industry sources, and academic publications

Phase 3: Causal Analysis and Impact Assessment

- Employ statistical methods to isolate policy impacts from other factors

- Conduct comparative case studies across jurisdictions with different policy approaches

- Interview policymakers, industry participants, and other stakeholders to identify mechanism effectiveness

- Assess unintended consequences and distributional impacts across different stakeholder groups

Phase 4: Integration Effectiveness Evaluation

- Analyze how policies specifically enable or hinder technology integration

- Evaluate grid integration outcomes and system flexibility enhancements

- Assess the balance between technology-specific and technology-neutral policy approaches

- Document best practices and transferable policy design elements

This protocol enables systematic comparison across different policy regimes and generates actionable insights for policymakers and researchers. The framework emphasizes not just whether policies increase renewable deployment generically, but how effectively they promote the integration of diverse renewable sources into a coherent, reliable energy system.

Research Reagent Solutions: Analytical Tools for Policy Evaluation

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools for Renewable Integration Policy Research

| Research Tool Category | Specific Methodologies | Application in Policy Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Energy System Modeling | TIMES, MARKAL, OSeMOSYS | Assessing long-term policy impacts on energy system configuration |

| Power System Simulation | PSSE, PowerFactory, MATPOWER | Evaluating grid integration challenges and infrastructure requirements |

| Economic Analysis | Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE), Job Multipliers, Input-Output Models | Quantifying economic impacts and cost-effectiveness of policy interventions |

| Geospatial Analysis | GIS-based suitability mapping, Spatial econometrics | Identifying renewable acceleration areas and analyzing land-use impacts |

| Stakeholder Analysis | Q-methodology, Social Network Analysis, Delphi Method | Understanding policy acceptance and coalition-building opportunities |

| Investment Risk Assessment | Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) modeling, Monte Carlo simulation | Evaluating how policies affect investment risk and financing costs |

These "research reagents" represent the essential methodological toolkit for conducting rigorous evaluation of integrated renewable energy policies. Their application enables researchers to move beyond descriptive policy analysis to causal inference and impact forecasting.

Integration Metrics and Technology-Specific Policy Effectiveness

Bioenergy Integration in the Renewable Portfolio

Bioenergy occupies a distinctive niche in the renewable energy portfolio, offering dispatchable capacity that can complement variable renewables like solar and wind. The policy frameworks supporting bioenergy integration emphasize its role in providing grid stability, managing organic waste streams, and decarbonizing hard-to-electrify sectors like industrial heat and heavy transport.

Advanced bioenergy technologies, including gasification, pyrolysis, and torrefaction, have significantly improved conversion efficiencies and reduced emissions [34]. These technological advances enable more effective integration of bioenergy with other renewables by enhancing operational flexibility and creating valuable co-products like biochar, which can sequester carbon in soils while improving agricultural productivity [34].

The most effective policy frameworks for bioenergy integration address several unique challenges:

- Sustainable feedstock supply: Policies must balance bioenergy production with food security and environmental protection, often through sustainability certification and support for non-food biomass sources [34]

- Carbon accounting methodologies: Robust lifecycle assessment frameworks are needed to accurately quantify the carbon benefits of different bioenergy pathways

- Sector-coupling incentives: Policies that reward bioenergy for providing grid services or decarbonizing industrial processes encourage more integrated deployment

The EU's revised Renewable Energy Directive includes specific provisions for bioenergy sustainability criteria, creating a template that other jurisdictions are adapting to local conditions [29]. These frameworks are essential for ensuring that bioenergy integration contributes meaningfully to decarbonization goals without creating adverse environmental impacts.

System Integration Enablers: Storage, Grids, and Flexibility

The integration of high shares of renewable energy depends critically on enabling technologies and policies that provide system flexibility. Energy storage installations, particularly battery energy storage systems (BESS), surged in 2024, with costs declining by 93% since 2010 to reach $192/kWh for utility-scale systems [27]. This dramatic cost reduction has transformed the economic viability of storage-supported renewable integration.

Policy support for storage has evolved from generic research funding to targeted mechanisms that recognize the multiple values storage provides to the system. These include:

- Capacity mechanisms that compensate storage for availability

- Ancillary service markets that enable storage to provide frequency regulation and voltage support

- Investment tax credits specifically for storage paired with renewables

- Technical standards that ensure interoperability and safety

Grid infrastructure represents another critical enabler of integration. The EU's identification of renewables acceleration areas is complemented by parallel initiatives to streamline permitting for related grid infrastructure [29]. This recognizes that renewable generation and transmission development must proceed in tandem to avoid curtailment and congestion that undermine the economic and environmental value of renewable investments.

Policy Integration Pathway: This diagram illustrates how different policy instruments activate specific integration mechanisms to produce desired system outcomes.

Emerging Challenges and Research Directions

Despite significant progress, substantial challenges remain in optimizing policy frameworks for integrated renewable development. Grid congestion, permitting delays, and interconnection queues continue to constrain deployment in many markets [28]. These bottlenecks reflect the complex interplay between policy, infrastructure, and community engagement that characterizes modern energy system development.

Financing costs remain a decisive factor in determining project viability, with significant disparities between developed and developing economies. IRENA's analysis indicates that while physical installation costs for renewable projects are becoming more consistent globally, the cost of capital ranges from 3.8% in Europe to 12% in Africa [27]. This differential highlights the critical importance of de-risking instruments and supportive financial frameworks in emerging markets.

Future research should prioritize several key areas:

- Dynamic policy analysis: How policy sequences and interactions affect integration outcomes over time

- Distributional impacts: How integrated renewable development affects different communities and stakeholders

- Institutional innovation: New governance models for managing increasingly complex, decentralized energy systems

- Digitalization policies: How data governance, cybersecurity, and privacy regulations enable or constrain renewable integration

- Just transition mechanisms: Policies that ensure the benefits of integrated renewable development are widely shared

The policy landscape continues to evolve rapidly, with 2025 emerging as a potential inflection point where renewable generation has begun displacing fossil fuels at a global scale [26]. This milestone creates both opportunity and imperative for researchers to generate actionable insights that can guide the next phase of the energy transition toward increasingly integrated, efficient, and equitable renewable energy systems.

Frameworks and Technologies for Hybrid System Implementation

Sequential Optimization Models for Integrated Bioenergy and Solar Planning

The global imperative to transition towards sustainable energy systems has intensified the focus on renewable sources like bioenergy and solar power. However, planning these systems independently often leads to competition for critical, limited resources, most notably land. Sequential optimization models provide a sophisticated computational framework to address this challenge by systematically determining the optimal allocation of resources across different renewable energy technologies in a staged manner. This guide objectively compares the performance of these modeling approaches against alternative planning methods within the context of bioenergy system integration.

The core challenge in integrated energy planning lies in resolving conflicts such as the food-energy-land nexus, where the pursuit of one objective can inadvertently hamper another. Sequential optimization tackles this by structuring the complex problem into manageable, consecutive stages, thereby preventing the overestimation or underestimation of a technology's potential—a common pitfall of standalone analyses [35]. This is critical for researchers and policymakers aiming to develop robust, efficient, and secure renewable energy strategies.

Comparative Analysis of Planning Models

Evaluating different planning methodologies is essential for selecting the right tool for integrated energy analysis. The table below compares sequential optimization against two other common approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Renewable Energy Integration Planning Models

| Model Type | Core Approach | Advantages | Limitations | Suitability for Bioenergy-Solar Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Optimization | Solves the planning problem in consecutive, dependent stages (e.g., bioenergy first, then solar on residual land) [35]. | Prevents double-counting of resources; reflects real-world policy priorities and land-use constraints; more accurately estimates net energy potential [35]. | The sequence (e.g., bioenergy before solar) may introduce hierarchy that doesn't reflect true cost-effectiveness; solution is often a "good" approximation rather than a guaranteed global optimum. | High. Directly addresses the core conflict of land competition. |

| Fully Integrated Single-Stage Optimization | Models all energy technologies and resource constraints within a single, comprehensive model to find a simultaneous solution. | Theoretically finds the global optimum for the entire system; captures all interactions and trade-offs at once. | Computationally complex; can be infeasible for large-scale, detailed problems; requires high-quality, concurrent data for all subsystems. | Medium. Theoretically ideal but often difficult to implement at a system-wide level. |

| Independent Technology Assessment | Analyzes each renewable technology (bioenergy, solar) separately without considering interactions. | Simple to implement and understand; requires minimal data integration. | Severely overestimates total renewable potential by ignoring competition for shared resources like land and capital [35]. | Low. Fails to model the core integration challenge, leading to unrealistic plans. |

Performance Data from a Sequential Framework Application

A 2025 study on Taiwan's energy insecurity provides a compelling case with quantitative data on the performance of a two-stage sequential optimization framework for agrivoltaic planning [35].

Table 2: Quantitative Outputs from a Two-Stage Agrivoltaic Optimization Model [35]

| Performance Metric | Biopower Production (Stage 1) | Biofuel Production (Stage 1) | Solar Energy Potential (Stage 2) | Total Agrivoltaic Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Output | 5,816 - 1,640 GWh/year | 4.9 - 504 million liters/year | 811 - 1,041 GWh/year | Up to 6,855 GWh/year |

| CO₂ Emission Offset | 0.35 - 3.49 million tons (collective for bioresources) | " | 1.08 - 1.13 million tons | Up to 4.62 million tons (collective) |

Key Findings from the Data:

- Technological Transition: The model revealed that changes in emission prices can cause significant technological shifts and substantial land transfer between agricultural and energy uses [35].

- Land-Use Challenge: The study highlighted that land-use transfer is a critical and persistent challenge for the long-term viability of solar energy programs, a factor that sequential modeling is uniquely positioned to illuminate [35].

- Systemic Value: The combined agrivoltaic system was shown to provide substantial energy and emission savings, which would be overestimated without a integrated view [35].

Experimental Protocol for Sequential Model Implementation

The following workflow details the methodology for developing and applying a two-stage sequential optimization model, as referenced in the case study.

Detailed Methodological Steps

Stage 1: Bioenergy Sector Optimization

- Objective Function: Maximize social welfare of the combined agricultural and bioenergy sectors, balancing farmer revenue, energy production costs, and environmental benefits [35].

- Key Constraints:

- Land Availability: Total available cropland, including idle and active land.

- Food Security: Minimum production requirements for key food commodities.

- Resource Allocation: Limits on water, fertilizers, and other agricultural inputs.

- Technological Options: Inclusion of both conventional (e.g., bioethanol from crops) and advanced (e.g., cellulosic processes from crop residuals) bioenergy pathways [35].

- Outputs: Optimal allocation of land for food crops versus energy crops, biofuel and biopower production levels, and the quantity of land transferred from agricultural to non-agricultural uses [35].

Stage 2: Solar Energy Potential Assessment

- Objective Function: Maximize solar energy generation and its economic value, subject to the land constraints determined in Stage 1.

- Key Constraints:

- Land Input: Only the residual, non-agricultural land identified in Stage 1 is available for solar development [35].

- Regional Solar Capacity: Solar radiation strength and installation potential vary by region [35].

- Budget & Financing: Capital accessibility and the impact of financial instruments like green bonds are incorporated [35].

- Outputs: Regional solar energy capacity, total financial requirements, and the aggregate renewable energy production and emission offsets for the entire integrated system [35].

Hybridization Challenges & Advanced Strategies

While sequential optimization effectively resolves land competition, integrating the resulting bioenergy and solar systems presents further technical challenges that require advanced strategies.

Table 3: Key Hybridization Challenges and Research Solutions

| Challenge Category | Specific Issue | Emerging Research Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Technology-Specific | PV intermittency from weather dependence [36]. | Advanced forecasting models and hybrid system design. |

| Biomass gasification issues like tar formation and high operational costs [36]. | Improved gasification reactors and feedstock pre-processing. | |