Optimizing Biomass Energy Conversion: Advanced Strategies for Enhanced Efficiency and Sustainability in 2025

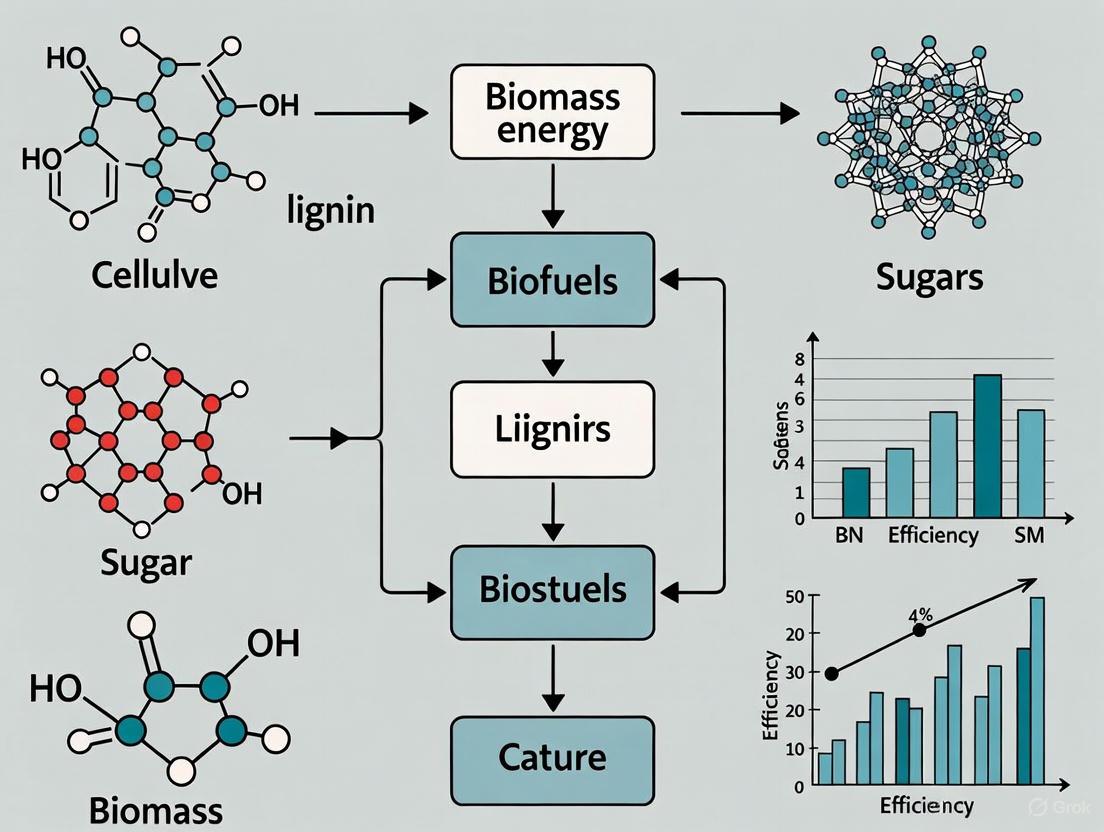

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current strategies and technological innovations aimed at improving biomass energy conversion efficiency.

Optimizing Biomass Energy Conversion: Advanced Strategies for Enhanced Efficiency and Sustainability in 2025

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of current strategies and technological innovations aimed at improving biomass energy conversion efficiency. Tailored for researchers and scientists in renewable energy and related fields, it explores the foundational challenges of biomass utilization, details cutting-edge conversion methodologies, addresses critical operational issues like slagging and supply chain logistics, and presents validation frameworks through techno-economic and life-cycle assessments. Synthesizing the latest research from 2025, the review outlines a roadmap for achieving higher efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability in biomass energy systems, highlighting the pivotal role of digitalization, hybrid models, and advanced materials in advancing the global bioeconomy.

Understanding Biomass Conversion: Core Challenges and Efficiency Fundamentals

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Biomass Conversion Efficiency

Q1: What is Biomass Conversion Efficiency and why is it a critical metric? Biomass Conversion Efficiency is a fundamental metric that quantifies the effectiveness of a process in converting the energy stored in biomass into a usable form of energy, such as heat, electricity, or fuel [1]. It is calculated as the ratio of energy output to energy input, expressed as a percentage [1]. This indicator is crucial because it directly impacts the economic viability, operational efficiency, and environmental footprint of bioenergy systems. A higher efficiency signifies better resource utilization, lower operational costs, and reduced waste, making it a central focus for research and development [2] [1].

Q2: My gasification process is yielding a low-quality syngas with high tar content. What operational parameters should I investigate? Low-quality syngas in downdraft gasifiers is often linked to suboptimal geometric and feedstock parameters. Your investigation should focus on:

- Fuel Fraction Size (SVR): The ratio of the fuel particle's surface area to its volume (SVR) is critical. Research on willow biomass gasification found that a specific SVR of 0.7–0.72 mm⁻¹ resulted in the maximum carbon monoxide (CO) concentration in the syngas, indicating higher gas quality and process efficiency [3].

- Reduction Zone Geometry (H/D Ratio): The ratio of the height to the diameter (H/D) of the gasifier's reduction zone significantly influences gas quality. The same study identified an optimal H/D range of 0.5–0.6 for maximizing CO production [3].

- Equivalence Ratio (ER): Ensure the air supply maintains an appropriate Equivalence Ratio, typically between 0.3–0.35 for downdraft gasifiers, to support efficient gasification reactions [3].

Q3: Our biomass feeding system is experiencing frequent blockages (bridging and ratholing), leading to inconsistent feed and process downtime. How can this be resolved? Bridging and ratholing are common flow problems caused by the cohesive nature and variable particle size of biomass [4]. To mitigate these issues:

- Material Characterization: Conduct a thorough analysis of your biomass feedstock's properties, including moisture content, particle size distribution, and density [4].

- Equipment Design: Invest in hoppers and feeders designed for mass flow, which promote uniform material movement and prevent the formation of stable ratholes and bridges [4].

- Pre-Processing: Implement pre-processing steps such as drying to reduce moisture, and size reduction (e.g., chipping, pelleting) to create a more homogeneous feedstock, thereby improving flowability [4].

Q4: What are the typical efficiency ranges I should target for different biomass conversion pathways? Conversion efficiency varies significantly by technology and feedstock. The following table summarizes reported efficiency ranges from literature:

| Conversion Technology | Feedstock | Efficiency Metric | Reported Efficiency | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gasification [5] | Woodchips | Thermal Conversion Efficiency | ~80% | Fuel properties, reactor pressure |

| Gasification [5] | Arundo Donax (100%) | Thermal Conversion Efficiency | 42-48% | Fuel properties, reactor pressure |

| Gasification [3] | Fast-Growing Willow | Electric Power Output (from syngas) | 2.4 kW (37.5% lower than gasoline) | Fuel fraction size (SVR), H/D ratio of reduction zone |

| Fischer-Tropsch (Bio-FT) [6] | Various Biomasses | Overall Energy Conversion Efficiency | 16.5% to 53.5% | Gasification technique, process configuration, definition of efficiency metric |

| Benchmark KPI [2] | Various | Biomass Utilization Rate | >80% (Excellent) | Process optimization, technology, staff training |

Q5: Why is there such a wide range of reported efficiencies for Fischer-Tropsch synthesis, and how can I ensure my results are comparable? The wide range for Bio-FT efficiencies (16.5%–53.5%) stems from a lack of standardization in definitions and accounting methods [6]. To ensure comparability:

- Define the Indicator Clearly: Specify whether you are calculating "overall efficiency" (biomass-to-fuel) or "biomass-to-fuel efficiency" (which excludes auxiliary inputs) [6].

- State the Energy Basis: Explicitly declare if you are using the Lower Heating Value (LHV) or Higher Heating Value (HHV) of inputs and outputs, as this significantly impacts the result [6].

- Report System Boundaries: Detail what energy inputs (e.g., biomass, electricity for compression, heat) and outputs are included in your calculation [6].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Challenge 1: Inconsistent Feedstock Leading to Variable Conversion Rates

Problem: Fluctuations in the composition, moisture content, or particle size of biomass feedstock cause unpredictable conversion efficiency. Solution:

- Standardize Pre-Processing: Establish a strict protocol for feedstock drying, grinding, and sieving to achieve a consistent particle size distribution before experiments [4].

- Implement Real-Time Monitoring: Use near-infrared (NIR) sensors or other rapid analysis tools to characterize the feedstock's moisture and composition in real-time, allowing for process adjustments.

- Create Blended Feedstocks: Blend different batches of feedstock to create a larger, more homogeneous material pool for your experiments, reducing batch-to-batch variability.

Problem: The measured energy content of your biofuel or syngas is lower than theoretical predictions. Solution:

- Optimize Key Parameters: For gasification, systematically test the H/D ratio and fuel fraction size (SVR) to find the optimum for your specific reactor and feedstock [3].

- Analyze Energy Losses: Conduct an energy balance to identify major loss points, which could be in the form of heat, unreacted char, or tar. Employ insulation, improve reactor design, or optimize the equivalence ratio to minimize these losses [1] [3].

- Consider Co-Product Recovery: The overall energy and economic efficiency can be improved by capturing and utilizing co-products. For example, the bio-char produced from pyrolysis can be used as a soil amendment or for carbon sequestration, adding value to the process [1].

Experimental Protocol: Determining Gasification Efficiency

Objective: To determine the thermal conversion efficiency of a specific biomass feedstock using a downdraft gasification system.

Principle: The thermal conversion efficiency is calculated by comparing the energy content of the produced syngas to the energy content of the biomass feedstock consumed [5] [1]. The workflow for this experiment is outlined below.

Materials and Equipment:

- Downdraft gasifier with an adjustable reduction zone

- Biomass feedstock (e.g., woodchips, energy grass)

- Drying oven and milling/sieving equipment

- Analytical balance

- Air flow meter and controller

- Gas chromatograph (GC) or similar gas analysis system

- Syngas flow meter

- Calorimeter for determining heating values

Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: Dry the biomass feedstock to a constant weight. Process it (chip, grind) to achieve a specific Surface-to-Volume Ratio (SVR), targeting a range of 0.7–0.72 mm⁻¹ as a starting point [3]. Determine the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of the prepared feedstock using a calorimeter.

- Reactor Configuration: Set the height-to-diameter (H/D) ratio of the gasifier's reduction zone to a value within the 0.5–0.6 range [3].

- Process Operation:

- Weigh and record the mass of the biomass feedstock to be loaded into the gasifier.

- Start the gasifier and initiate air flow. Maintain an Equivalence Ratio (ER) of approximately 0.3–0.35 by controlling the air flow rate [3].

- Allow the system to reach a stable operating temperature before proceeding.

- Data Collection:

- Measure the volumetric flow rate of the produced syngas.

- Use the gas chromatograph to analyze the composition of the syngas (primarily the concentrations of CO, H₂, and CH₄) at multiple time points.

- After a predetermined run time, stop the process and weigh any remaining ungasified char.

- Efficiency Calculation:

- Calculate the heating value of the syngas (HHV~syngas~) based on its composition and known heating values of its combustible components.

- Calculate the total energy output in the syngas:

Energy_out = Syngas_Flow_Rate * HHV_syngas * Time. - Calculate the total energy input from the biomass:

Energy_in = Mass_of_Biomass_Consumed * HHV_biomass. - Compute the thermal conversion efficiency:

Efficiency (%) = (Energy_out / Energy_in) * 100%[1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials and equipment essential for conducting rigorous biomass conversion efficiency research.

| Item | Function / Relevance in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Downdraft Gasifier | A common reactor for small to medium-scale thermochemical conversion research, known for lower tar production [3]. | Lab-scale systems with adjustable reaction zones (e.g., modifiable H/D ratio) [3]. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Used for precise quantitative analysis of syngas composition (CO, H₂, CH₄, CO₂), which is critical for calculating energy output [5] [3]. | System equipped with Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) and appropriate columns for permanent gas separation. |

| Calorimeter | Determines the Higher Heating Value (HHV) or Lower Heating Value (LHV) of both solid biomass feedstock and liquid/gaseous bio-fuels, a fundamental input for any efficiency calculation [6] [1]. | Bomb calorimeter for solid feedstocks; gas calorimeter for syngas. |

| Feedstock (SVR Parameter) | The Surface-to-Volume Ratio (SVR) of the fuel fraction is a key parameter influencing gasification kinetics and efficiency, not just particle size [3]. | Prepared biomass with a characterized SVR (e.g., 0.7–0.72 mm⁻¹ for optimal willow gasification) [3]. |

| Mass Flow Hopper | Specialized equipment designed to promote uniform flow of biomass, mitigating bridging and ratholing, thus ensuring consistent feedstock supply for accurate data [4]. | Hoppers designed for mass flow principles, often with specific wall surface finishes and geometry. |

Technical Support Center: Frequently Asked Questions

Why does my biomass feedstock yield high levels of inhibitory compounds during pretreatment, and how can I mitigate this?

The formation of inhibitors is highly dependent on the chemical structure of your biomass components and the pretreatment method used.

- Hemicellulose-Rich Feedstocks: Under high heat and acidic conditions, hemicellulose readily decomposes into furfural and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF), which are potent microbial inhibitors [7]. To mitigate, consider switching to milder alkaline or ionic liquid pretreatments, which are more effective at delignification with less sugar degradation [8].

- Lignin-Derived Inhibitors: Harsh thermal treatments can break down lignin into phenolic compounds, which disrupt microbial cell membranes. Solution: Incorporate a detoxification step post-pretreatment, such as overlining (pH adjustment) or the use of activated charcoal to adsorb inhibitors before fermentation [8].

My enzymatic hydrolysis yields for cellulose are consistently low. What factors should I investigate?

Low cellulose conversion is often a symptom of insufficient biomass deconstruction. The recalcitrant lignin network physically blocks enzyme access to cellulose fibers [9].

- Assess Lignin Content and Structure: Feedstocks with high lignin content (e.g., softwoods) are particularly challenging. Ensure your pretreatment method is specifically designed for delignification. Methods like oxidative pretreatment or using deep eutectic solvents (DESs) have shown significant potential in disrupting lignin structures [8].

- Evaluate Pretreatment Efficiency: A successful pretreatment should significantly alter the biomass morphology. Use microscopy (SEM) or compositional analysis to confirm the removal of hemicellulose and lignin, thereby increasing cellulose accessibility [8].

- Optimize Enzyme Cocktail: Use advanced cellulolytic enzymes tailored to your specific feedstock. The inclusion of lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs) can enhance the breakdown of crystalline cellulose [8].

How does the variable composition of biomass feedstocks impact my conversion process stability?

Variability in the cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin ratios is a major hurdle for consistent biorefinery operation [7].

- Problem: Fluctuations in sugar release rates and inhibitor formation make fermentation unpredictable.

- Strategy: Implement a robust Feedstock Blending protocol. Mix feedstocks to create a more consistent composite material. For example, blending a high-cellulose material (like corn stover) with a high-lignin material (like wood chips) can balance the conversion dynamics [8]. Advanced process control systems can also be programmed to adjust pretreatment severity in real-time based on incoming feedstock characterization.

I am not achieving the expected biofuel yields from hemicellulose-derived sugars. What could be the issue?

This is a common issue related to the microbial strains used in fermentation.

- The C5 Sugar Challenge: Native yeast strains used in ethanol production (e.g., S. cerevisiae) cannot metabolize pentose sugars (like xylose and arabinose) from hemicellulose [8].

- Solution: Employ genetically engineered microorganisms that have been specifically designed to co-ferment both hexose (C6) and pentose (C5) sugars. Consolidated bioprocessing (CBP) strains, which combine enzyme production, saccharification, and fermentation, are a leading area of research to address this yield gap [8].

Quantitative Data on Biomass Components

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and challenges of the three main lignocellulosic components, providing a quick reference for troubleshooting conversion issues.

Table 1: Biomass Component Characteristics and Conversion Challenges

| Component | Typical Composition (Dry Mass %) | Primary Conversion Challenge | Key Inhibitors or By-Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | 40 - 50% [8] | Recalcitrant crystalline structure; requires specific pretreatment and enzymes for breakdown into glucose [8]. | None directly, but inaccessible without effective pretreatment. |

| Hemicellulose | 20 - 30% [8] | Amorphous but heteropolymer; yields mixed sugars (C5 & C6) that require specialized microbes for fermentation [7] [8]. | Furfural, 5-HMF (from dehydration of pentose and hexose sugars) [7]. |

| Lignin | 15 - 30% [8] | Robust, aromatic polymer that protects cellulose; its breakdown is a major hurdle and can produce fermentation inhibitors [9] [8]. | Phenolic compounds (from breakdown of aromatic rings) [7]. |

The following table compares the gas-phase products generated from the pyrolysis of each component, highlighting their distinct thermal behaviors.

Table 2: Characteristic Pyrolysis Gas Yields by Biomass Component [7]

| Biomass Component | Highest CO₂ Yield | Highest CH₄ Yield | Highest CO Yield (at high temperature) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | Above 550°C | ||

| Hemicellulose | ✓ | ||

| Lignin | ✓ |

Standard Experimental Protocols for Deconstruction Analysis

Protocol 1: Two-Stage Acid-Alkaline Pretreatment for Enhanced Sugar Release

This protocol is designed to sequentially target hemicellulose and lignin for a more complete deconstruction of the biomass matrix.

- Feedstock Preparation: Mill biomass to a particle size of 0.5-2 mm. Determine initial moisture content.

- Stage 1 - Acid Hydrolysis (Hemicellulose Solubilization):

- Prepare a 1-3% (w/w) dilute sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) solution.

- Mix biomass with the acid solution at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10.

- React in a pressurized vessel at 140-160°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Cool and filter to separate the solid residue (now enriched in cellulose and lignin) from the liquid hydrolysate containing C5 sugars.

- Stage 2 - Alkaline Treatment (Delignification):

- Treat the solid residue from Stage 1 with a 2-4% (w/w) sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution.

- Maintain a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10.

- React at 80-121°C for 30-90 minutes.

- Filter and wash the solid pellet, which is now the pretreated biomass enriched with accessible cellulose.

- Analysis: The final solid is highly amenable to enzymatic hydrolysis. The liquid streams should be analyzed for sugar content (HPLC) and inhibitor concentration (e.g., furans, phenolics) [8].

Protocol 2: Enzymatic Hydrolysis Efficiency Assay

This protocol standardizes the measurement of sugar yield from your pretreated biomass.

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a 2% (w/v) suspension of your pretreated biomass in a suitable buffer (e.g., sodium citrate, pH 4.8-5.0).

- Add a commercial cellulase enzyme cocktail (e.g., CTec3) at a loading of 10-20 mg protein per gram of dry biomass.

- Include a negative control (buffer and biomass, no enzymes) and a positive control (a standard cellulose like Avicel).

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture in a shaking incubator at 50°C for 72 hours to maintain enzyme activity and ensure good mixing.

- Sampling and Analysis:

- Withdraw samples at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours.

- Immediately heat samples to 95°C for 10 minutes to denature enzymes and stop the reaction.

- Centrifuge and analyze the supernatant for glucose and xylose concentration using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with a refractive index detector [8].

- Calculation: Calculate the cellulose conversion efficiency as (Glucose released / Potential glucose in pretreated biomass) × 100%.

Biomass Analysis Workflow and Composition Hurdles

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for analyzing biomass and the specific hurdles imposed by its composition.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential reagents and materials critical for experiments focused on overcoming the biomass composition hurdle.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biomass Conversion Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate) | Powerful solvent for pretreatment; effectively dissolves cellulose and lignin, reducing biomass recalcitrance [8]. | High cost and need for near-complete recycling for process viability. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DESs) | Greener alternative to ionic liquids; effective for selective delignification with lower toxicity and cost [8]. | Solvent design and recovery are active research areas. |

| Advanced Enzyme Cocktails (e.g., CTec3, HTec3) | Multi-enzyme mixtures for hydrolyzing cellulose (cellulases) and hemicellulose (hemicellulases) into fermentable sugars [8]. | Optimizing the ratio of different enzyme activities (e.g., endoglucanase, exoglucanase, β-glucosidase) for specific feedstocks is crucial. |

| Genetically Engineered Microbes (e.g., S. cerevisiae, Z. mobilis) | Strains engineered to co-ferment both C6 (glucose) and C5 (xylose) sugars, maximizing biofuel yield from the entire biomass [8]. | Genetic stability and inhibitor tolerance under industrial conditions are key performance metrics. |

| Synthetic Lignin (Dehydrogenation Polymers) | Model compound for studying lignin structure, depolymerization pathways, and catalyst development without feedstock variability [7]. | May not fully replicate the complex native lignin structure in plant cell walls. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the primary causes of slagging and fouling in biomass combustion systems? Slagging and fouling are primarily caused by the inorganic components in biomass fuels, particularly alkali metals (Potassium and Sodium) and their interactions with chlorine (Cl) and sulfur (S). During combustion, alkali metals can form compounds with low melting points, such as alkali silicates, sulfates, and chlorides. These compounds either melt and form slag on heat exchanger surfaces (slagging) or condense from the vapor phase onto cooler surfaces like superheater tubes (fouling) [10] [11]. The specific nature of the biomass dictates the severity; agricultural residues (e.g., cotton stalk, rice husk) are often more problematic due to higher alkali metal content compared to woody biomass [12] [13].

2. How does the potassium-to-chlorine (K:Cl) ratio in my fuel influence these problems? The K:Cl molar ratio is a critical indicator. If the ratio is greater than one, significant potassium is available to react with fly ash particles (e.g., silica) to form potassium silicates, which are major contributors to slagging. If the ratio is less than one, most potassium will form gaseous KCl, which contributes to fouling through condensation on cooler heat exchanger surfaces and can also lead to high-temperature corrosion [10]. Controlling this ratio through fuel blending or pre-treatment is a key mitigation strategy.

3. What operational conditions can I adjust to minimize deposition during my co-combustion experiments? Experimental research on a drop-tube furnace indicates that several operational parameters can be optimized:

- Combustion Temperature: Maintaining a lower combustion temperature (e.g., 1050°C vs. 1300°C) helps prevent the transformation of solid compounds into low-melting-point eutectic mixtures [12].

- Biomass Blending Ratio: Limiting the proportion of high-alkali biomass (e.g., agricultural residues like cotton stalk) in the fuel blend reduces the total alkali metal input and mitigates severe slagging [12].

- Excess Air Coefficient: While increasing excess air can accelerate sulfur reactions, it has been shown not to relieve heavy sintering and may not be a reliable standalone solution [12].

4. Are there effective chemical additives to prevent slagging and fouling? Yes, the use of aluminosilicate additives, such as kaolin, has been proven effective. Kaolin reacts with alkali metals in the combustion zone to form refractory compounds like kalsilite (KAlSiO₄), which have high melting points (>1300°C). This sequesters potassium in a solid, non-sticky form, preventing it from forming low-melting-point silicates or condensing as corrosive vapors [13].

5. What is the mechanism behind alkali-induced high-temperature corrosion? High-temperature corrosion is initiated by chlorine. Gaseous alkali chlorides (KCl, NaCl) condense on metal surfaces (e.g., superheater tubes). These deposits destroy the protective oxide layer on the metal. Once this layer is compromised, the underlying metal becomes susceptible to direct oxidation, leading to rapid material degradation [13].

Key Experimental Data and Indicators

Table 1: Common Slagging and Fouling Indices Based on Ash Composition [11]

| Index Name | Formula / Basis | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Base-to-Acid Ratio | (Fe₂O₃ + CaO + MgO + K₂O + Na₂O) / (SiO₂ + TiO₂ + Al₂O₃) | High ratio indicates greater slagging propensity. |

| Alkali Index | (kg K₂O + Na₂O) per GJ of fuel | >0.17 kg/GJ likely fouling; >0.34 kg/GJ certain fouling. |

| Bed Agglomeration Index | (K₂O + Na₂O) / (SiO₂ + CaO + MgO) | Used to predict agglomeration in fluidized beds. |

Table 2: Effect of Combustion Parameters on Slagging Severity [12]

| Parameter | Condition | Observed Effect on Ash |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Type | Cotton Stalk vs. Sawdust | Cotton stalk (high K) caused severe agglomeration; sawdust caused less. |

| Blending Ratio | 10% vs. 30% biomass | Higher proportion of biomass led to more serious slagging. |

| Combustion Temperature | 1050°C vs. 1300°C | Higher temperature promoted formation of low-melting eutectic compounds. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Assessing Slagging Propensity via Chemical Fractionation and Thermodynamic Modeling

This protocol is based on the thermodynamic approach used to assess slagging and fouling, allowing for alkali/ash reactions [10].

Objective: To determine the reactive fraction of inorganic matter in a biomass fuel and model its slagging behavior under combustion conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Pulverized biomass fuel sample (particle size < 100 µm)

- Sequential leaching solvents: Purified water, 1 M Ammonium Acetate (NH₄Ac), 1 M Hydrochloric Acid (HCl)

- Laboratory glassware (beakers, filtration setup)

- Oven (55°C for drying)

- Software for thermodynamic equilibrium calculations (e.g., FactSage, Aspen Plus)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dry the biomass sample at 55°C for 3 hours to remove moisture. Record the initial mass.

- Successive Leaching (Chemical Fractionation):

- Water Leaching: Leach the sample with purified water for 1 hour. Filter and collect the residue. This step dissolves highly soluble ionic salts (alkali chlorides, sulfates).

- Acetate Leaching: Leach the water-insoluble residue with 1 M NH₄Ac for 2 hours. Filter and collect the residue. This step dissolves salts associated with organic structures (e.g., alkali oxalates).

- Acid Leaching: Leach the acetate-insoluble residue with 1 M HCl for 3 hours. Filter and collect the final residue. This step dissolves carbonates and some silicates. The remaining final residue is considered the inert, non-reactive fraction (mainly silicates).

- Data Analysis for Modeling:

- The reactive fraction of the fuel is defined as the sum of the material dissolved in the water and acetate leaching steps. This fraction is assumed to reach equilibrium during combustion.

- For a more comprehensive model, a portion (e.g., 10%) of the HCl-soluble and residue fraction can be included to simulate the interaction of reactive layers on fly ash particles.

- Thermodynamic Equilibrium Calculation:

- Input the composition of the reactive fraction (from step 3) into the thermodynamic software.

- Run equilibrium calculations over a temperature range simulating the combustion system (e.g., from 1600°C down to 600°C).

- Key outputs to analyze include:

- The percentage of melt phase in the condensed matter.

- The distribution of potassium between the gas phase (KCl, KOH) and condensed phases (silicates).

Interpretation of Results:

- A high percentage of melt phase in the high-temperature zone (e.g., 1600–1300°C) indicates a high risk of slagging.

- The presence of gaseous KCl and KOH at high temperatures and their subsequent condensation at lower temperatures indicates a propensity for fouling and corrosion [10].

Process Visualization: Alkali Metal Transformation Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the key transformation pathways of alkali metals during biomass combustion, leading to operational challenges.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Slagging/Fouling Experiments

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Kaolin (Aluminosilicate Additive) | Mitigation agent; reacts with gaseous potassium to form high-melting-point kalsilite (KAlSiO₄), reducing slagging and fouling [13]. |

| Ammonium Acetate (1M Solution) | Chemical fractionation reagent; used to leach biomass samples and dissolve alkali metals associated with organic structures [10]. |

| Drop-Tube Furnace (DTF) | Laboratory-scale reactor for simulating combustion conditions and studying ash deposition behavior under controlled temperature and atmosphere [12]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope with Energy Dispersive X-Ray (SEM-EDX) | Analytical technique for determining the morphology and elemental composition of ash deposits and agglomerates [12]. |

| X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) | Analytical technique for identifying the crystalline mineral phases present in ash and deposits, crucial for understanding slag formation [12]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Biomass Supply Chain Challenges

| Problem Area | Specific Challenge | Impact on Research & Experiments | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Logistics | Low bulk energy density of raw biomass (e.g., straw, wood chips) [14]. | Increases transportation costs and frequency; complicates storage space planning for experiments; can lead to inconsistent bulk volumes in pre-processing. | Densification: Process raw biomass into pellets or briquettes to increase energy density per unit volume, reducing logistical footprint [14]. |

| Seasonal availability of agricultural residues (e.g., corn stover, rice husks) [15]. | Disrupts continuous, year-round research operations; forces frequent recalibration of conversion processes due to feedstock switches. | Multi-Feedstock Stockpiling: Create preserved stockpiles (e.g., ensiled, dried) of key seasonal feedstocks. Develop flexible experimental protocols tolerant of multiple feedstock types [15]. | |

| Supply Chain Coordination | Lack of organized collection and inconsistent supply chains in developing regions [16]. | Introduces uncertainty in feedstock procurement; leads to delays in experiments and potential quality degradation of materials received. | Supplier Qualification & Mapping: Conduct local biomass mapping to identify and qualify reliable suppliers. Establish clear quality specifications and contracts for research-grade feedstock [15]. |

| Feedstock Quality | High moisture content and biodegradability during storage [14]. | Causes variation in experimental results due to fluctuating moisture; risk of microbial spoilage alters feedstock composition and energy content. | Pre-Storage Preprocessing: Implement drying (solar, thermal) and proper storage (covered, aerated) protocols. Monitor moisture content upon receipt and before use [14]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How does the low energy density of biomass directly impact the economic viability of our research-scale conversion process? Low energy density significantly increases the cost and logistical complexity of supplying your lab with sufficient feedstock for continuous experiments. The high volume and weight of raw biomass require more frequent deliveries and larger storage facilities, increasing the operational cost per unit of energy produced in your trials. This can skew techno-economic analyses if not properly accounted for. Densification into pellets can mitigate this by reducing volume and improving handling, but it adds an upfront processing cost [14].

FAQ 2: What are the best practices for managing seasonal variability in biomass feedstock to ensure consistent year-round experiments? The most effective strategy is strategic stockpiling and pre-processing of seasonal feedstocks. This involves:

- Preservation: For wet feedstocks like some agricultural residues, ensiling is an effective method to preserve them for months.

- Drying and Storage: For dry residues, ensuring they are dried to a safe moisture level and stored in covered, aerated facilities prevents degradation.

- Blending: Developing protocols for blending different seasonal feedstocks (e.g., agricultural residues in harvest season with more consistent forest waste) can help maintain a consistent overall feedstock quality for your conversion processes [15].

FAQ 3: Beyond cost, what are the critical experimental variables most affected by seasonal feedstock variability? Seasonal shifts can significantly alter key feedstock properties, which in turn affect conversion efficiency and output. Critical variables to monitor include:

- Moisture Content: Affects energy balance in thermochemical processes (e.g., gasification, pyrolysis) and microbial activity in biochemical processes (e.g., anaerobic digestion).

- Biochemical Composition: The ratios of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin can vary with harvest time and crop variety, directly impacting sugar yields for biofuel production or syngas composition in gasification.

- Ash Content and Composition: This can vary seasonally and affect slagging behavior in thermochemical converters and act as a catalyst poison [14].

FAQ 4: Our research indicates that supply chains for agricultural biomass are fragmented. How can we secure a reliable supply for our pilot-scale project? Building a resilient supply chain requires proactive engagement. Recommendations from industry workshops include:

- Supply Chain Mapping: Actively map local biomass availability and engage with aggregators or agricultural cooperatives.

- Direct Relationships: Establish direct, long-term relationships with growers or major waste producers, offering them a stable offtake for their residues.

- Clear Specifications: Provide clear technical specifications for the biomass you require (e.g., moisture, contamination levels) to ensure quality and consistency [15].

Experimental Protocols for Analyzing Feedstock Impact

Protocol 1: Quantifying the Impact of Biomass Densification on Energy Density and Handling Properties

1. Objective: To empirically determine the improvement in energy density and flowability achieved by pelleting loose biomass.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Loose biomass sample (e.g., straw, sawdust)

- Laboratory-scale pellet mill

- Calorimeter (for Higher Heating Value measurement)

- Analytical balance

- Standard volume container (e.g., 1-liter cylinder)

- Tapped density tester (optional)

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Baseline Measurement. Weigh a known volume of loose biomass to determine its bulk density (

Mass/Volume). Measure its Higher Heating Value (HHV) using a calorimeter. - Step 2: Densification. Process the loose biomass through the pellet mill under standardized conditions (e.g., die temperature, pressure).

- Step 3: Pelletized Measurement. Weigh a known volume of pellets to determine the new, higher bulk density. Measure the HHV of the pellets.

- Step 4: Data Analysis. Calculate the percentage increase in bulk density. Compare the HHV values to confirm no significant degradation during pelleting. The energy density (

HHV * Bulk Density) of the pelleted form will be significantly higher.

4. Visualization of Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for Protocol 1.

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Seasonal Variability on Conversion Efficiency

1. Objective: To evaluate how biochemical composition changes in seasonally harvested biomass affect sugar yield from enzymatic hydrolysis.

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Biomass samples harvested in different seasons (e.g., spring, summer, autumn)

- Standardized cellulase and hemicellulase enzyme cocktails

- Laboratory reactors or sealed incubation vials

- pH meter and buffer solutions

- Autoclave

- HPLC (High-Performance Liquid Chromatography) system for sugar analysis

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Feedstock Characterization. For each seasonal sample, perform compositional analysis to determine the percentages of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin.

- Step 2: Standardized Pre-treatment. Apply a consistent pre-treatment (e.g., dilute acid) to all samples to make the cellulose accessible.

- Step 3: Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Subject a fixed mass of each pre-treated sample to enzymatic hydrolysis under controlled conditions (pH, temperature, duration, enzyme loading).

- Step 4: Product Analysis. Use HPLC to quantify the glucose and xylose concentrations in the hydrolysate from each sample.

- Step 5: Data Analysis. Calculate the sugar yield for each seasonal sample. Correlate the yields with the initial compositional data to identify which compositional factors (e.g., lignin content) most significantly impact seasonal variability.

4. Visualization of Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for Protocol 2.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function in Research | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory-Scale Pellet Mill | Increases the energy density of loose, low-bulk-density biomass for more consistent handling and experimentation [14]. | Essential for pre-processing logistics studies and standardizing feedstock for conversion experiments. |

| Calorimeter | Measures the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of biomass samples, a critical parameter for calculating energy density and conversion efficiency [14]. | Used for feedstock characterization and quality control before and after pre-processing steps. |

| Cellulase & Hemicellulase Enzyme Cocktails | Catalyze the breakdown of cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars during biochemical conversion studies [14]. | Key reagent for assessing the saccharification potential of different feedstocks, especially when evaluating seasonal variability. |

| Anaerobic Digester Setup | A controlled bioreactor system for studying the production of biogas (methane) from wet organic waste via anaerobic digestion [17] [14]. | Used for waste-to-energy conversion research and evaluating the impact of feedstock composition on methane yield. |

| Laboratory Gasification Unit | A small-scale reactor for thermochemical conversion of solid biomass into syngas (a mixture of CO, H₂, CH₄) [17] [18]. | Critical for researching advanced conversion pathways and the impact of feedstock properties on syngas quality and tar formation. |

Biomass power generation, the process of converting organic materials into electricity, has become a critical component of the global renewable energy mix. It offers a sustainable solution for reducing carbon emissions and enhancing energy security by utilizing resources like wood pellets, agricultural residues, and municipal solid waste. [17] [19] The global market, valued at US$90.8 billion in 2024, is projected to grow steadily, reaching US$116.6 billion by 2030 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.3%. [17] [19] This growth is primarily driven by global decarbonization efforts, supportive government policies, and technological advancements that are improving the efficiency and cost-competitiveness of biomass conversion technologies. [17] [19] [20] For researchers, optimizing the efficiency of this energy conversion is paramount to maximizing the economic and environmental returns of biomass power.

The biomass power market demonstrates robust growth globally, though projections vary slightly between sources due to different segmentation and methodologies. The common trend across all analyses points towards significant expansion over the next decade.

Global Market Size and Forecast

Table 1: Global Biomass Power Generation Market Size Projections

| Report Source | Base Year/Value | Projection Year/Value | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Research and Markets [17] [19] | 2024: US$90.8 Billion | 2030: US$116.6 Billion | 4.3% (2024-2030) |

| Coherent Market Insights [20] | 2025: USD 146.58 Billion | 2032: USD 211.96 Billion | 5.4% (2025-2032) |

| Precedence Research [21] | 2024: USD 141.29 Billion | 2034: USD 251.60 Billion | 5.95% (2025-2034) |

| Research and Markets (Alternate Report) [22] | 2025: USD 51.7 Billion | 2033: USD 83 Billion | 6.1% (2025-2033) |

Regional Market Dynamics

The market is not uniform, with different regions leading in adoption and growth due to varying resource availability and policy landscapes.

Table 2: Key Regional Biomass Power Market Trends (2024-2025)

| Region | Market Status & Share | Key Contributing Countries & Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Europe | Dominant region, holding 39% share in 2024. [21] | Germany, France, Sweden, Finland. Driven by EU's carbon neutrality goal (European Green Deal) and strong policy support (e.g., Germany's Renewable Energy Sources Act). [23] [21] |

| North America | Significant market share, led by the U.S. [21] | United States, Canada. Abundant forestry resources, renewable portfolio standards, and decarbonization mechanisms. [17] [21] |

| Asia-Pacific | Fastest-growing regional market. [20] [21] | China, India, Japan, Thailand. Driven by rising energy demand, waste management needs, and strong government targets (e.g., China's carbon neutrality by 2060). [20] [23] [21] |

Key Policy Drivers and Regulatory Frameworks

Government policies are the primary catalysts for biomass power development, creating a stable investment environment and incentivizing technological innovation.

- Renewable Energy Mandates and Incentives: Many countries have implemented Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) that mandate a certain percentage of power from renewable sources, including biomass. [20] Direct financial incentives such as feed-in tariffs, renewable energy credits, tax credits, and carbon tax exemptions are crucial for improving the economic viability of biomass power projects. [17] [19] [20]

- Carbon Pricing and Emission Reduction Targets: The implementation of carbon pricing mechanisms and strict emission reduction targets under international agreements like the Paris Agreement is a powerful driver. Biomass is often considered carbon-neutral, and when combined with carbon capture and storage (CCS), it can achieve carbon-negative emissions, making it highly attractive for decarbonizing the power sector. [17] [19] [24]

- Blending Mandates for Biofuels: Policies specifically targeting the transport sector, such as blending mandates for biodiesel and ethanol, indirectly support the broader bioenergy sector. In 2024, Indonesia fully implemented its B35 (35% biodiesel) mandate, Brazil enacted the Fuel of the Future law targeting B20 by 2030, and India pursued an E20 (20% ethanol blending) goal. [23] These policies stimulate feedstock supply chains and conversion technology development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) for Researchers

Table 3: Frequently Asked Questions on Biomass Conversion Efficiency

| Question Category | Specific Question | Evidence-Based Insight & Troubleshooting Tip |

|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Selection | Why does my gasification process yield inconsistent syngas quality? | Troubleshooting Tip: Feedstock properties (moisture, ash content, particle size) critically impact output. Solution: Implement strict feedstock preprocessing (drying, shredding) to ensure homogeneity. Torrefaction can enhance energy density and stabilize feedstock. [17] [20] |

| Feedstock Selection | Which feedstock is most promising for high-energy output? | Research Context: Thermochemical pathways (e.g., gasification) using solid biofuels like forestry residues yield the highest energy output (0.1–15.8 MJ/kg), but with greater GHG emissions and cost compared to biochemical pathways. [25] [20] [21] |

| Technology & Process | How can I improve the overall efficiency of my biomass power system? | Research Focus: Integrate Combined Heat and Power (CHP) systems. This maximizes energy efficiency by utilizing waste heat for industrial or residential applications, significantly boosting the total useful energy output from the same amount of feedstock. [17] [22] |

| Technology & Process | What is the potential of biomass for hydrogen production? | Experimental Insight: Biomass gasification is a competitive pathway for low-emission hydrogen. The process can yield ~100 kg H₂ per ton of dry biomass with 40-70% efficiency (LHV). When integrated with CCS, it can achieve negative emissions of -15 to -22 kg CO₂eq per kg H₂. [24] |

| Policy & Economics | How do policies directly impact my research on conversion efficiency? | Grant/Funding Context: Supportive policies (tax credits, green bonds) de-risk investment in advanced, high-efficiency technologies like gasification and CHP. Your research into cost-reduction and efficiency gains is critical for biomass to compete with other renewables, as current costs can be several times higher. [17] [25] |

| Policy & Economics | My techno-economic model shows high costs. How can they be reduced? | Modeling Parameter: Explore co-firing biomass with coal in existing plants as a transitional, cost-effective strategy. It reduces capital expenditure and can lower lifecycle emissions by over 70%. [20] |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Efficiency Research

Protocol 1: Biomass Gasification for Syngas/Hydrogen Production

Principle: Thermochemical conversion of biomass into a synthetic gas (syngas) rich in hydrogen and carbon monoxide in a controlled, oxygen-limited environment. [24]

Workflow Diagram: Biomass Gasification Process

Methodology:

- Feedstock Preparation: Dry biomass feedstock to moisture content below 15%. Reduce particle size to a uniform range (e.g., 1-5 mm) to ensure consistent reaction kinetics. [24]

- Gasification: Load the preprocessed biomass into a fluidized-bed or entrained-flow gasifier. Maintain a temperature between 700-900°C. Introduce a controlled flow of gasifying agent (air, oxygen, or steam). The use of pure oxygen or steam as an agent is key for producing a higher quality, nitrogen-free syngas suitable for hydrogen production. [24]

- Syngas Cleaning: Pass the raw syngas through a series of cleanup units: cyclones (particulate removal), scrubbers (tar removal), and filters. This step is critical for protecting downstream equipment and catalysts.

- Hydrogen Enrichment (Water-Gas Shift): Direct the cleaned syngas to a catalytic water-gas shift reactor. Here, carbon monoxide (CO) reacts with steam (H₂O) over a catalyst (e.g., iron oxide) to produce additional hydrogen (H₂) and carbon dioxide (CO₂). [24]

- Gas Separation/Purification: Separate hydrogen from other gases (primarily CO₂) using pressure swing adsorption (PSA) or membrane technologies. The captured CO₂ stream can be stored or utilized (CCS/S). [24]

Protocol 2: Anaerobic Digestion for Biogas Production

Principle: Biochemical conversion of organic matter by microbial consortia in the absence of oxygen to produce biogas (primarily methane and CO₂). [17] [20]

Workflow Diagram: Anaerobic Digestion Process

Methodology:

- Inoculum and Substrate Preparation: Mix the biomass substrate (e.g., animal manure, municipal food waste) with an active anaerobic inoculum (e.g., from an existing digester) in a defined ratio to ensure a viable microbial population. [23]

- Digester Operation: Load the mixture into a temperature-controlled batch or continuous digester. Maintain a strict mesophilic (~35°C) or thermophilic (~55°C) temperature regime, as methanogenic archaea are highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations.

- pH and Agitation Monitoring: Continuously monitor and control the pH within the optimal range for methanogenesis (6.5-7.5). Provide gentle, continuous agitation to maintain homogeneity and enhance mass transfer without shearing the microbial communities.

- Biogas Collection and Analysis: Collect the produced biogas in a gas bag or holder. Regularly analyze its composition (CH₄, CO₂, H₂S) using gas chromatography to monitor process stability and conversion efficiency.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials and Analytical Tools for Biomass Conversion Research

| Category | Item | Specific Function in Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Samples | Woody Biomass (e.g., Forest Residues, Wood Pellets) | High-energy density solid biofuel; ideal for thermochemical studies (combustion, gasification). [17] [20] [21] |

| Agricultural Residues (e.g., Straw, Bagasse) | Abundant, low-cost feedstock; research focuses on efficient preprocessing and overcoming high ash/silica content. [17] [25] [20] | |

| Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) / Food Waste | Key for waste-to-energy (WTE) research; challenges include feedstock heterogeneity and contamination. [17] [25] | |

| Catalysts & Reagents | Gasification Agent (Oxygen, Steam) | Controls the gasification reaction; pure oxygen/steam produces medium-heating-value syngas for hydrogen production. [24] |

| Nickel-Based Catalysts | Used in tar reforming and water-gas shift reactions during gasification to increase hydrogen yield. [24] | |

| Anaerobic Digestion Inoculum | A mature microbial sludge source essential for initiating and accelerating the anaerobic digestion process in experiments. [23] | |

| Analytical & Monitoring Tools | Gas Chromatograph (GC) with TCD/FID | For precise quantification of gas composition (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) in syngas or biogas. Critical for calculating conversion efficiency. |

| Calorimeter (Bomb) | Measures the higher heating value (HHV) of raw biomass and solid residues, determining the energy content of the feedstock. | |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Studies the thermal decomposition behavior (kinetics, mass loss) of biomass under different atmospheres. | |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Software | Evaluates the environmental footprint (e.g., GHG emissions: 0.003–1.2 kg CO₂/MJ) of the conversion technology. [25] |

Advanced Conversion Technologies and Process Intensification Strategies

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the primary causes of low syngas quality and yield in biomass gasification, and how can they be mitigated?

Low syngas quality, characterized by low heating value and high tar content, often results from suboptimal operational parameters. Key factors include incorrect temperature settings, unsuitable gasifying agents, and inadequate reactor configuration.

- Temperature Control: Syngas yield increases with temperature, with stable production yields reaching up to approximately 90% at elevated operating temperatures (800–1100°C is typical for the reduction stage) [26]. Ensure your system maintains the appropriate temperature range for the desired reactions.

- Gasifying Agent Selection: The choice of gasifying agent (e.g., air, oxygen, steam, or CO2) directly influences syngas composition and heating value. Using air typically produces a low heating value gas (4–7 MJ/Nm³), while O2 and steam can yield a medium heating value syngas (10–18 MJ/Nm³) [26].

- Tar Reduction: Tar formation is a major challenge. Advanced reactor designs like fluidized-bed gasifiers and the use of specific catalysts during the process can significantly reduce tar content and improve syngas purity [26].

FAQ 2: How do I select the appropriate pyrolysis regime to maximize the yield of my target product (bio-oil, biochar, or syngas)?

The distribution of pyrolysis products is highly sensitive to operational parameters, primarily temperature and heating rate [27]. The table below summarizes how to optimize for each primary product.

- Product Yield Optimization:

| Target Product | Recommended Regime | Typical Temperature Range | Key Operational Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biochar | Slow Pyrolysis | 300-500°C | Low heating rate, long solid residence time [27]. |

| Bio-oil | Fast Pyrolysis | 400-600°C | High heating rate, short vapor residence time [27]. |

| Syngas | Flash Pyrolysis | >700°C | Very high heating rate and temperature [27]. |

- Reaction Atmosphere: Modifying the reaction atmosphere can further enhance yields. For example, a CO2 atmosphere can increase gas formation and biochar surface area, while steam can enhance bio-oil yield [27].

FAQ 3: What are the common reasons for low cold gas efficiency (CGE) in a gasifier, and what steps can be taken for improvement?

Cold gas efficiency (CGE) is a key performance indicator, representing the fraction of the chemical energy in the feedstock converted into chemical energy in the syngas. Typical CGE ranges between 63% and 76%, depending on the feedstock and technology [26].

- Feedstock Preparation: The composition and physical properties of the biomass feedstock highly influence gasification reactivity [26]. Ensure consistent feedstock size and low moisture content to promote efficient conversion.

- Carbon Conversion: Low CGE is often linked to incomplete carbon conversion. Optimizing the equivalence ratio (the ratio of actual oxidizer to the stoichiometric oxidizer) and ensuring good mixing of feedstock and the gasifying agent can improve carbon conversion efficiency [26].

- Reactor Choice: Different gasifiers have inherent efficiency ceilings. For instance, while fixed-bed gasifiers are simple, fluidized-bed and entrained-flow gasifiers often provide better mixing and higher efficiency [26].

FAQ 4: Which modeling approach is most suitable for predicting gas composition and optimizing process parameters in gasification?

The choice of model depends on the specific goal, the available computational resources, and the required accuracy [26].

- For initial design and rapid estimation: Thermodynamic equilibrium models are widely used (approximately 60% of studies) and are effective for predicting maximum possible yields and gas composition without delving into reactor-specific kinetics [26].

- For detailed reactor design and analysis: Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) models provide powerful insights by solving conservation equations for mass, heat, and momentum, offering detailed profiles of fluid dynamics and heat transfer within the gasifier [26].

- For data-rich and predictive control applications: Data-driven models, such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), have proven very accurate for predicting syngas production and composition, especially when trained on experimental data from a specific system [26].

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue: Rapid Catalyst Deactivation in Catalytic Pyrolysis or Gasification

- Problem: Catalyst deactivation leads to a decline in product yield and selectivity over time, increasing operational costs.

- Investigation Protocol:

- Check for Carbon Fouling (Coking): This is a common cause. Analyze used catalyst for carbon deposits. Mitigation strategies include adjusting the steam-to-fuel ratio or incorporating periodic catalyst regeneration cycles with air or oxygen to burn off the carbon.

- Analyze for Thermal Sintering: Exposure to excessive temperatures can cause catalyst particles to fuse, reducing surface area. Verify that operational temperatures are within the catalyst's specified limits and that there are no localized hot spots in the reactor.

- Test for Chemical Poisoning: Certain elements in the biomass ash (e.g., sulfur, chlorine, alkali metals) can poison catalysts. Perform ultimate and proximate analysis of your feedstock to identify potential contaminants. Consider pre-treatment of the feedstock or using a poison-resistant catalyst formulation.

Issue: Inconsistent Feedstock and Bridging in Reactor Hoppers

- Problem: Variations in feedstock particle size, shape, and moisture content can cause poor flow, bridging (blockages), and uneven conversion in the reactor.

- Investigation Protocol:

- Implement Pre-Processing: Establish a standardized pre-processing protocol including drying (to below 15-20% moisture), shredding, and sieving to achieve a consistent particle size distribution.

- Evaluate Feed System Design: Ensure the hopper design has adequate angles and may require the integration of mechanical aids like vibrators or screw feeders to ensure consistent and reliable feedstock flow into the reactor.

This table provides a high-level comparison of the key performance metrics for thermochemical pathways based on the search results.

| Performance Metric | Gasification | Pyrolysis (Fast) | Pyrolysis (Slow) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Output Range | 0.1 - 15.8 MJ/kg [25] | Primary product is Bio-oil | Primary product is Biochar |

| Typical GHG Emissions | 0.003 - 1.2 kg CO2/MJ [25] | Data not specified | Data not specified |

| Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE) | 63% - 76% [26] | Not Applicable | Not Applicable |

| Primary Product | Syngas (H2, CO, CH4) | Bio-oil (liquid) | Biochar (solid) |

This table summarizes how critical process parameters affect the yields of biochar, bio-oil, and syngas during pyrolysis.

| Process Parameter | Impact on Biochar Yield | Impact on Bio-oil Yield | Impact on Syngas Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increased Temperature | Decreases | Increases (to a point, then decreases) | Increases |

| Faster Heating Rate | Decreases | Increases | Increases |

| Longer Vapor Residence Time | Decreases | Decreases (due to cracking) | Increases |

| Use of CO2 Atmosphere | Increases surface area, may decrease yield | Can decrease yield | Increases |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Gasification Performance and Syngas Quality

Objective: To evaluate the performance of a biomass gasification process by measuring cold gas efficiency (CGE), carbon conversion efficiency (CCE), and syngas composition.

- Feedstock Preparation: Reduce biomass feedstock to a consistent particle size (e.g., 1-2 mm). Dry in an oven at 105°C for 24 hours to achieve a moisture content below 10%.

- Reactor Setup and Instrumentation:

- Use a fluidized-bed or downdraft gasifier system.

- Calibrate all sensors: thermocouples along the reactor height, mass flow controllers for the gasifying agent (air/steam), and pressure transducers.

- Connect a gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) and a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) to the syngas output line for real-time analysis of H2, CO, CO2, CH4, and N2.

- Experimental Run:

- Load the reactor with a known mass of feedstock (M_feed).

- Initiate the gasification process by introducing the pre-heated gasifying agent at a controlled flow rate. Maintain the target bed temperature (e.g., 800°C).

- Operate the system until steady-state is reached (constant temperature and gas composition).

- Data Collection and Analysis:

- Syngas Composition: Record the volumetric percentages of H2, CO, CO2, and CH4 from the GC at steady state.

- Syngas Flow Rate: Measure the volumetric flow rate of the produced syngas using a gas meter.

- Solid Residue: After the run, collect and weigh the solid residue (ash and unreacted carbon, M_residue).

- Calculations:

- Carbon Conversion Efficiency (CCE): Calculate based on the carbon content in the feedstock and the solid residue.

- Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE): CGE = (Energy in syngas / Energy in biomass feedstock) × 100%. The energy in syngas is calculated from its flow rate, composition, and respective heating values of the gas components [26].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Bio-Oil Yield via Fast Pyrolysis

Objective: To determine the optimal temperature and vapor residence time for maximizing bio-oil yield from a lignocellulosic biomass in a fast pyrolysis system.

- Reactor Configuration: Employ a fluidized-bed pyrolysis reactor with an electrostatic precipitator or a condenser system for bio-oil collection.

- Parameter Screening:

- Independent Variables: Temperature (450°C, 500°C, 550°C) and Vapor Residence Time (0.5s, 1.0s, 2.0s).

- Constant Parameters: Maintain a consistent biomass particle size (~1mm) and a high heating rate (>100°C/s).

- Experimental Procedure:

- For each experimental run, load a precise mass of dry feedstock (e.g., 100g).

- Bring the reactor to the target temperature under an inert N2 atmosphere.

- Introduce the feedstock and record the process conditions. The vapor residence time is controlled by adjusting the carrier gas flow rate and the reactor's hot zone volume.

- Collect the condensed bio-oil in the cooling system and weigh it (Moil). Collect the non-condensable gases and measure their volume. Weigh the remaining biochar (Mchar).

- Yield Calculation:

- Bio-oil Yield (wt%) = (Moil / Mfeed) × 100%

- Biochar Yield (wt%) = (Mchar / Mfeed) × 100%

- Gas Yield (wt%) = 100% - Bio-oil Yield - Biochar Yield

- Analysis: Plot the yields of all three phases against temperature and residence time. The optimal condition for bio-oil production is typically where its yield is maximized, often at around 500°C with a short residence time (~1s) to minimize secondary cracking of vapors [27].

Process Visualization

Gasification Stages

Pyrolysis Parameter Impact

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Thermochemical Conversion Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Zeolite Catalysts (e.g., ZSM-5) | Catalytic upgrading of pyrolysis vapors to improve bio-oil quality and deoxygenation [27]. | Choice of zeolite SiO2/Al2O3 ratio affects selectivity and resistance to coking. |

| Nickel-Based Catalysts | Steam reforming of tars in gasification syngas to produce cleaner H2-rich gas [26]. | Susceptible to sulfur poisoning and coking; requires pre-cleaning of syngas. |

| Gasifying Agents (O2, Steam, CO2) | Mediate the thermochemical reactions. Influence syngas composition and heating value [26]. | High-purity O2 avoids N2 dilution. Steam-to-biomass ratio is a critical optimization parameter. |

| Lignocellulosic Model Compounds | Used in fundamental studies to deconvolute complex reaction mechanisms of real biomass [28]. | Common examples: Cellulose (Avicel), Xylan (Hemicellulose), Kraft Lignin. |

| Gas Calibration Standard | Essential for accurate quantification and calibration of Gas Chromatographs (GC) for syngas analysis [26]. | Contains known concentrations of H2, CO, CO2, CH4, C2H4, and N2 in a balance gas. |

| Data-Driven Modeling (ANN Tools) | For creating predictive models of gasification/pyrolysis outcomes based on input parameters [26] [28]. | Requires a substantial dataset for training; software like Python with TensorFlow/PyTorch is typical. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Anaerobic Digestion

Q1: Why has my biogas production significantly decreased? A decrease in biogas production often indicates an imbalance in the anaerobic digestion process. Key parameters to check include:

- Volatile Fatty Acids (VFA) Accumulation: A buildup of VFAs occurs when acid-producing bacteria outpace methane-producing archaea. Monitor VFA levels regularly; a consistent upward trend from a stable baseline (e.g., rising from 2,000 mg/L to 3,000-4,000 mg/L) signals a problem. This can be caused by organic overloading or inhibition of methanogens [29].

- Inhibition of Methanogens: Methanogens are sensitive to environmental shifts. Common inhibitors include:

- Ammonia (NH₃): Concentrations above 100 mg NH₃-N/L are significantly inhibitory [29].

- Temperature Fluctuations: Changes exceeding 1-2°C per day can disrupt microbial activity. Maintain optimal temperatures (e.g., 35-38°C for mesophilic, 55°C for thermophilic digestion) [30] [29].

- pH Levels: A drop in pH, often a consequence of VFA accumulation, further inhibits methanogens. The optimal pH range is typically 6.5-8.0 [30] [31].

- Nutrient Deficiencies: A lack of trace metals like cobalt, iron, nickel, and molybdenum can hamper microbial metabolism and biogas yield [29].

Q2: My digester is experiencing foaming and scum formation. What is the cause? Excessive foaming or scum can disrupt the process and reduce gas production. This is frequently caused by:

- Improper Mixing: Inadequate agitation leads to poor distribution of microorganisms and substrates, causing stratification and scum layer formation [31].

- Process Imbalance: An imbalance in the microbial consortium, often linked to organic overloading or feedstock variation, can trigger foaming [31] [29].

- Inert Solids Accumulation: The recycle of process streams (e.g., digestate water) can cause non-biodegradable colloidal solids to build up, contributing to foaming and occupying reactor volume [29].

Q3: How can I improve the stability and methane yield of my thermophilic anaerobic digester? Thermophilic Anaerobic Digestion (TAD) offers higher reaction rates and biogas yields but can be sensitive to operational changes [30].

- Employ a Two-Stage Temperature Shift Strategy: Acclimate mesophilic inoculum to thermophilic conditions gradually. A one-step shift to 50°C can enrich thermophilic hydrolytic bacteria, followed by a stepwise increase to the target temperature (e.g., 55°C) to protect and acclimate methanogens [30].

- Manage Organic Loading Rate (OLR) Carefully: Systematically increase the OLR while monitoring stability. Studies show TAD performance improves as OLR increases from 1.5 to 4.0 g VS/(L·d), but inhibition can occur at higher OLRs (e.g., 6.5 g VS/(L·d)) due to VFA accumulation and ammonia inhibition [30].

Performance Data & Optimization Strategies

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent research on enhancing anaerobic digestion performance.

Table 1: Experimental Performance Data for Yield Enhancement

| Parameter | Mesophilic Baseline (37°C) | Optimized Thermophilic (55°C) | Conditions & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily Biogas Yield | Baseline | 60.8% Higher than baseline [30] | Peak yield of 671.2 mL; OLR of 1.5 g VS/(L·d) [30]. |

| Peak Daily Biogas Yield | - | 2264.8 mL [30] | Achieved with sustained CH₄ content of 72–76% at OLR of 4 g VS/(L·d) [30]. |

| Methane (CH₄) Content | - | 72% - 76% [30] | Requires balanced microbial community and controlled OLR [30]. |

| Optimal OLR for TAD | - | Up to 4.0 g VS/(L·d) [30] | Tolerance is feedstock and system-dependent; higher OLRs (e.g., 5.0-6.5 g VS/(L·d)) risk process inhibition [30]. |

| Optimal C/N Ratio | 20:1 - 30:1 (General guideline) [30] | 20:1 (Used in experimental optimization) [30] | Prevents ammonia toxicity or nutrient deficiency [30]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Thermophilic Microbiome Acclimation

This protocol is adapted from a 2025 study that achieved a 60.8% increase in biogas yield through a two-stage temperature shift strategy [30].

Objective: To acclimate a mesophilic inoculum to thermophilic conditions for stable, high-yield anaerobic digestion of food waste.

Materials:

- Inoculum: Mesophilic anaerobic sludge (e.g., from a wastewater treatment plant), pre-incubated to deplete residual biodegradable matter [30].

- Substrate: Synthetic or actual food waste (FW). A formulated blend can include vegetables, cooked rice, potato peels, and meat, homogenized to a particle size of <5 mm [30].

- Reactor System: Stirred-tank reactors (e.g., 1 L volume) with working volume of 0.8 L, equipped for temperature control, mixing, and biogas collection [30].

- Analytical Equipment: pH meter, GC-TCD for biogas composition (CH₄, CO₂), HPLC or GC-FID for VFA analysis, equipment for TS/VS analysis [30].

Procedure:

- Start-up & One-Stage Temperature Shift: Inoculate the reactor with mesophilic sludge and substrate at an initial OLR of 1.5 g VS/(L·d). Purge the headspace with N₂ for 20 minutes to ensure anaerobic conditions. Increase the temperature directly to 50°C. Operate the reactor under these conditions to selectively enrich thermophilic hydrolytic and acidogenic bacteria [30].

- Stepwise Temperature Increase: After initial acclimation at 50°C, gradually increase the temperature to 55°C. This step is critical for the acclimation of temperature-sensitive methanogenic archaea without causing severe kinetic uncoupling [30].

- Microbial Community Analysis: Monitor the microbial community dynamics (e.g., via 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing) throughout the temperature transition. A successful acclimation will show an increased abundance of key thermophilic hydrolytic bacteria (e.g., Defluviitoga) and hydrogenotrophic methanogens (e.g., Methanoculleus) [30].

- OLR Optimization: Once a stable thermophilic community is established at 55°C, systematically increase the OLR from 1.5 g VS/(L·d) to 4.0 g VS/(L·d) in phases. Continuously monitor biogas production, CH₄ content, pH, and VFA levels to identify the system's maximum stable OLR [30].

Experimental Workflow and Inhibition Pathway

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for the thermophilic acclimation experiment and the key steps involved in troubleshooting acid inhibition.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Anaerobic Digestion Experiments

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Mesophilic Anaerobic Sludge | Serves as the starting inoculum for biogas experiments, providing a diverse microbial community. Often sourced from wastewater treatment plants [30]. |

| Synthetic Food Waste Blend | A standardized, homogenized substrate to ensure experimental reproducibility. A typical blend includes vegetables, cooked rice, potato peels, and meat in defined ratios, with C/N adjusted to ~20:1 [30]. |

| Trace Element Solution | Provides essential micronutrients (e.g., Co, Ni, Fe, Mo) that are co-factors for enzymatic activity in hydrolysis, acidogenesis, and methanogenesis, preventing nutrient deficiencies [29]. |

| Gas Chromatograph with TCD | For accurate measurement of biogas composition, specifically the percentages of methane (CH₄) and carbon dioxide (CO₂), which are key performance indicators [30]. |

| HPLC or GC System with FID | For quantifying concentrations of Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs—acetic, propionic, butyric acids), which are critical intermediates and key stability markers [30] [29]. |

| 16S rRNA Sequencing Reagents | For molecular analysis of microbial community structure and dynamics. Allows tracking of shifts in bacterial and archaeal populations in response to operational changes (e.g., temperature, OLR) [30] [32]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the significance of a two-stage temperature shift over a one-stage shift? A one-stage temperature shift can enrich for thermophilic bacteria but may severely impact mesophilic methanogens, leading to kinetic uncoupling and process instability. A two-stage (or stepwise) strategy fosters a more balanced microbial consortium by allowing for the gradual acclimation of methanogenic archaea, ultimately resulting in enhanced and more stable methane production [30].

Q2: How do recycle streams cause digester failure? Recycle streams, such as treated effluent or pressed digestate water, can lead to the accumulation of inhibitory substances that are not easily broken down. These include ammonia-nitrogen (TAN), salts (sodium, potassium, chloride), and inert colloidal solids. This accumulation can inhibit microbial activity, reduce treatment performance, and cause biological upsets [29].

Q3: What are the future research directions for enhancing biochemical routes in biomass energy? Future research is moving beyond energy production to integrate AD into the circular economy. Key directions include:

- Product Diversification: Optimizing the production of higher-value short- and medium-chain carboxylic acids from waste substrates [32].

- System Integration: Better integration of Power-to-X (P2X) technologies, such as the biomethanation of hydrogen and carbon dioxide [32].

- Pilot-Scale Validation: A critical need exists for more pilot-scale studies to bridge the gap between laboratory results and reliable commercial-scale application [32].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most effective hybrid renewable energy systems for reducing costs and emissions in biomass energy research? The most effective systems typically combine solar PV with biomass gasification, often incorporating energy storage. Research indicates that an optimized system using a 733.23 kW PV module and an 800 kW biomass generator can achieve a 100% renewable fraction and significant cost savings. The Levelized Cost of Energy (COE) for such a system can be as low as $0.0467 per kWh, with net present costs (NPC) around $1.97 million for a community-scale project [33]. These configurations successfully lower emissions to approximately 4.72 kg/h of CO₂ [33].

Q2: How does the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) improve the efficiency of biomass conversion processes? AI and machine learning models optimize biomass conversion by analyzing complex data patterns to predict and control key variables. Specific applications include:

- Predictive Modeling: Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs) can identify non-linear relationships in processes like anaerobic digestion and gasification, adjusting operational parameters to maximize fuel efficiency and product yield (e.g., methane, bio-oil) [34].

- Real-time Optimization: Backpropagation Neural Networks (BPNNs) enable real-time optimization of fuel consumption while minimizing emission output [34].

- Supply Chain and Process Management: AI enhances the entire biomass supply chain, from feedstock selection to conversion and waste management, improving logistical efficiency and reducing energy losses [35] [34].

Q3: What are the common causes of tar formation in biomass gasifiers and how can it be mitigated? Tar formation is a persistent challenge in biomass gasification, primarily caused by incomplete conversion of biomass during the thermochemical process. It can lead to blockages, corrosion, and engine damage [36]. Mitigation strategies focus on:

- Advanced Gasification Design: Optimizing reactor design and operating conditions (temperature, gasifying agent).

- Catalytic Cracking: Using advanced catalytic materials to break down tars into useful syngas components, thereby improving syngas quality and overall process efficiency [35] [36].

Q4: Why does my anaerobic digester show instability with low methane yield? Digester instability is often linked to the accumulation of volatile fatty acids (VFAs), which is frequently caused by an imbalance in the carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio of the feedstock [34]. This can be addressed by:

- Feedstock Co-digestion: Balancing the C:N ratio by mixing different substrates (e.g., animal manure with agricultural waste) to improve the buffering capacity and support a diverse microbial community [34].

- Parameter Control: Maintaining a stable temperature in the optimal range of 32–35 °C and adjusting pH levels to create a favorable environment for methanogenic bacteria [34].

- Pretreatment: Applying mechanical (e.g., bead milling) or ultrasonic pretreatment to the feedstock to decrease particle size and break down cell walls, which can increase methane yield by up to 28% [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Intermittency and Unreliable Power Output in Solar-Biomass Hybrid Systems

Symptoms: Fluctuating power supply, inability to meet consistent energy demand, especially during nighttime or periods of low solar irradiation.

Diagnosis and Solution: This is a fundamental challenge caused by the variable nature of solar energy [36] [37]. The solution lies in robust system design and advanced control strategies.

- System Sizing and Storage Integration: Use tools like HOMER Pro for techno-economic optimization. Integrate a sufficiently sized battery storage system (e.g., the ABB-M1 system identified in research) to store excess solar energy for use during non-sunny periods [33].

- Advanced Control Strategies: Implement an AI-enabled energy management system. These systems can forecast energy production and demand, dynamically switching between or blending solar and biomass-derived syngas to ensure a stable, continuous power supply [36].

- Biomass as a Baseload: Design the system so the biomass generator provides a reliable baseload power, while solar and storage handle peak loads and variations [33].

Problem: Low Hydrogen Content and Carbon Utilization in Syngas from Biomass Gasification

Symptoms: Production of syngas with a lower heating value than required for efficient fuel synthesis, leading to suboptimal yields of biofuels like methanol.

Diagnosis and Solution: Biomass inherently has low hydrogen content, which limits the efficiency of downstream carbon conversion into liquid fuels [38]. Solution: Integration of External Hydrogen. Enhance the syngas by supplementing it with hydrogen from an external low-carbon source.

- Recommended Protocol: Integration with Natural Gas Pyrolysis (NG-PS)

- Principle: Natural gas pyrolysis decomposes methane (CH₄) into hydrogen (H₂) and solid carbon, a lower-carbon alternative to steam methane reforming [38].

- Methodology:

- Gasification: Gasify biomass to produce syngas rich in carbon monoxide (CO).

- Pyrolysis: Simultaneously, decompose natural gas in a high-temperature, oxygen-free reactor to produce H₂.

- Syngas Enhancement and Synthesis: Mix the externally produced H₂ with the biomass-derived syngas. This adjusts the H₂/CO ratio to the optimal level (typically ~2:1) for catalytic synthesis into methanol or other liquid fuels via processes like Fischer-Tropsch [38].