Navigating Uncertainty: Strategies for Resilient and Economically Viable Biofuel Supply Chains

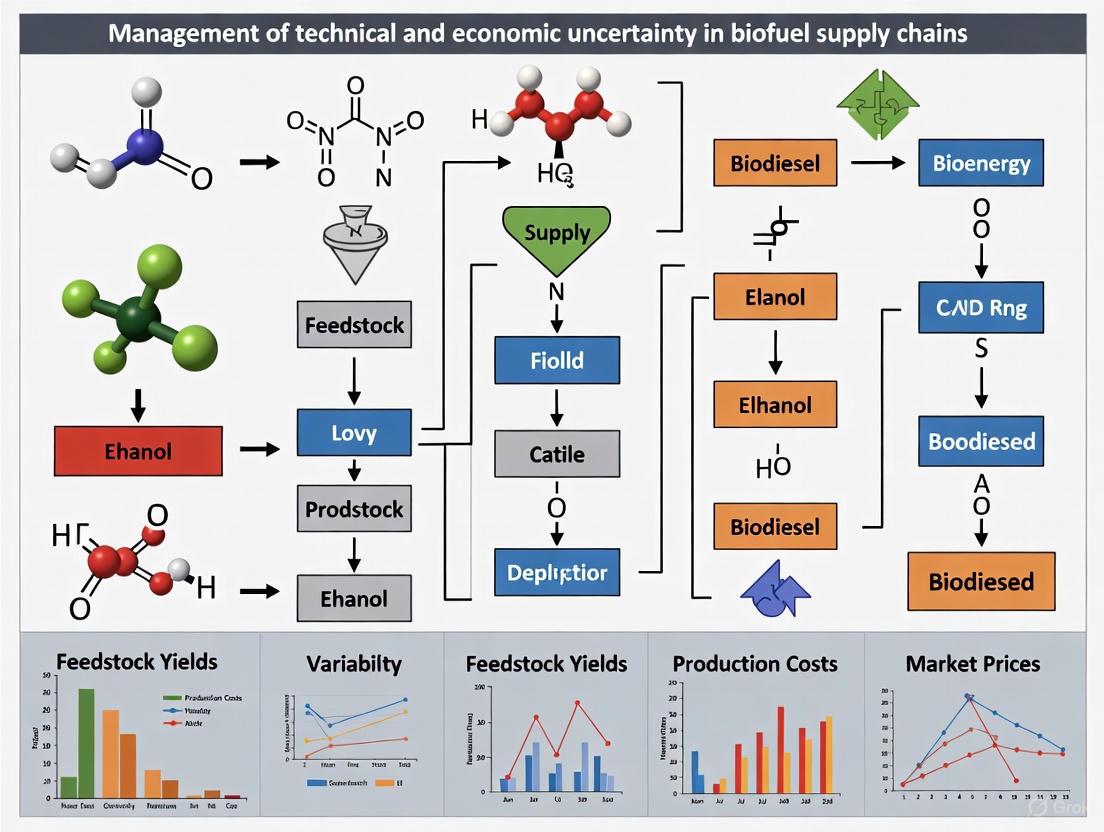

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the technical and economic uncertainties inherent in biofuel supply chains (BSCs), from feedstock production to final distribution.

Navigating Uncertainty: Strategies for Resilient and Economically Viable Biofuel Supply Chains

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the technical and economic uncertainties inherent in biofuel supply chains (BSCs), from feedstock production to final distribution. Aimed at researchers and industry professionals, it explores the foundational sources of risk, reviews advanced methodological frameworks for uncertainty modeling—including stochastic programming, robust optimization, and hybrid AI approaches—and presents practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for real-world operations. Through validation and comparative analysis of case studies, the article synthesizes effective practices for enhancing supply chain resilience, economic viability, and sustainability, offering a forward-looking perspective on the role of biofuels in the broader energy and bio-based product landscape.

Understanding the Landscape: Core Sources of Technical and Economic Uncertainty in Biofuel Production

Defining Biofuel Supply Chain Generations and Their Unique Risk Profiles

Biofuel supply chains (BSCs) are complex networks that encompass all operations from biomass production and pre-treatment to storage, transfer to bio-refineries, and final distribution to end-users [1]. These chains are typically categorized into four distinct generations, defined primarily by the type of feedstock utilized in the production process [1] [2]. Understanding these generations is crucial for researchers and industry professionals, as each presents a unique profile of technical and economic uncertainties that can significantly impact the viability and resilience of biofuel production systems.

The transition across generations represents an evolution from food-based feedstocks toward more sustainable, non-food alternatives, with each step introducing new technological challenges and risk factors. First-generation biofuels, derived from edible biomass, currently dominate production but raise significant concerns regarding food security competition. Second-generation technologies utilize non-edible lignocellulosic biomass to overcome this limitation, while third and fourth generations employ microalgae and genetically engineered microorganisms, respectively [1]. This progression introduces increasingly complex supply chain considerations, from biomass variability to conversion process stability and market acceptance.

Biofuel Generation Classifications and Characteristics

Table 1: Biofuel Generation Classifications, Feedstocks, and Key Characteristics

| Generation | Feedstock Examples | Technical Advantages | Sustainability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Generation | Corn, wheat, barley, sugarcane, edible oils | Established conversion technology, high TRL (Technology Readiness Level) | Food vs. fuel competition, agricultural land use change |

| Second Generation | Corn stover, switchgrass, woody crops, agricultural residues, non-edible plants | Non-competition with food supply, utilization of waste biomass | Higher preprocessing requirements, logistical complexity for dispersed biomass |

| Third Generation | Microalgae biomass | Fast growth rates, minimal land requirement, wastewater utilization | High water and nutrient inputs, sensitive cultivation parameters, downstream processing challenges |

| Fourth Generation | Genetically modified microalgae | Enhanced carbon capture capabilities, improved biofuel yields | Early-stage technology, regulatory uncertainties for genetically modified organisms |

The classification of biofuel generations reflects a strategic response to the limitations of previous approaches, particularly regarding sustainability and resource competition. First-generation biofuels, while technologically mature, face significant social acceptance challenges due to their impact on global food markets and land use patterns [1]. Second-generation biofuels overcome the food security dilemma but introduce substantial logistical complexities in biomass handling, storage, and transportation due to the dispersed nature and variable characteristics of lignocellulosic feedstocks [1] [3].

Third and fourth-generation biofuels represent more technologically advanced pathways with potentially superior environmental profiles, particularly in carbon capture and land use efficiency [1]. However, these pathways remain at earlier stages of commercial development and introduce unique vulnerabilities related to biological system stability, process control, and scale-up challenges. The progression through generations also reflects a shift in the geographic distribution of production facilities, with later generations potentially enabling more decentralized models due to reduced feedstock transportation constraints.

Biofuel Generations and Primary Risk Relationships

Risk Assessment Methodologies for Biofuel Supply Chains

Technical and Economic Uncertainty Analysis

Table 2: Quantitative Risk Assessment Methodologies for Biofuel Supply Chains

| Methodology | Application in BSC Research | Key Input Variables | Output Metrics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) with Monte Carlo Simulation | Financial viability assessment under uncertainty | Feedstock prices, conversion rates, capital investment, discount rates, labor costs, loan terms | Probability distributions of Minimum Fuel Selling Price (MFSP), Net Present Value (NPV) | [4] [5] [6] |

| Machine Learning-Facilitated TEA | Rapid uncertainty estimation for multiple production pathways | Financial, technical, and supply chain parameters at various scales | Predictive MFSP estimates, identification of key uncertainty drivers | [4] [5] |

| Dynamic Bayesian Network (DBN) | Dynamic risk assessment for external disruptions (e.g., pandemic impacts) | Feedstock gate availability, labor disruptions, market price fluctuations, policy changes | Recovery timeline projections, probabilistic risk assessments | [7] |

| Multi-Objective Optimization under Carbon Policies | Sustainable BSC design considering environmental regulations | Carbon cap, carbon tax, carbon trade, and carbon offset parameters | Network configuration, total cost, emission reduction, social impact | [3] |

Stochastic techno-economic analysis (TEA) has emerged as a pivotal methodology for assessing financial viability and risks inherent in biofuel production processes [4] [5]. Traditional Monte Carlo approaches involve random sampling of input variables and multiple runs of TEA models to create probability distributions of economic metrics like Minimum Fuel Selling Price (MFSP) and Net Present Value (NPV) [4] [6]. However, these traditional methods are computationally intensive and time-consuming when reliant on iterative process simulation calls.

Recent advancements have integrated machine learning frameworks to streamline conventional simulation processes by automating dataset generation and model training [4] [5]. These trained models enable rapid predictions of economic metrics at any scale, accommodating randomized input variables based on their defined distributions. This approach has proven particularly effective in identifying primary factors influencing uncertainties in minimum selling prices and exploring synergistic effects of pathway inputs across diverse biofuel production scenarios [4].

Experimental Protocol: Machine Learning-Enabled TEA

Protocol Title: Machine Learning-Facilitated Stochastic Techno-Economic Analysis for Biofuel Production Pathways

Objective: To rapidly assess techno-economic uncertainty and identify key drivers of financial viability in biofuel production pathways using machine learning methods.

Materials and Equipment:

- Process simulation software (e.g., Aspen Plus, SuperPro Designer)

- Machine learning platform (Python scikit-learn, TensorFlow, or PyTorch)

- Monte Carlo simulation environment

- Historical data on feedstock prices, conversion rates, and capital costs

Procedure:

- Dataset Generation: Automate the generation of training datasets by running multiple process simulations across defined ranges of input variables including feedstock costs, conversion efficiencies, energy inputs, and financial parameters.

- Model Training: Train machine learning models (e.g., neural networks, random forests) using the generated dataset to establish relationships between input variables and economic outputs such as MFSP.

- Uncertainty Propagation: Implement Monte Carlo sampling from probability distributions of key input variables based on their documented uncertainties and market volatility.

- Predictive Analysis: Use trained ML models to rapidly predict MFSP distributions for randomized input variables, bypassing computationally intensive process simulations.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Identify primary factors influencing uncertainties in minimum selling prices by analyzing the trained model's feature importance metrics.

- Validation: Compare ML-predicted MFSP distributions with traditional Monte Carlo TEA results for validation.

Expected Output: Probability distributions of MFSP, identification of key uncertainty drivers, and assessment of how price variability is impacted by financial, technical, and supply chain factors [4] [5].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions: Managing BSC Uncertainties

Q1: What are the most significant sources of uncertainty in second-generation biofuel supply chains compared to first-generation?

A: Second-generation BSCs face substantially different uncertainty profiles compared to first-generation. While first-generation chains primarily contend with food-fuel competition and agricultural commodity price volatility, second-generation chains exhibit greater logistical complexity due to the dispersed nature and seasonal availability of lignocellulosic biomass [1]. Additionally, second-generation feedstocks demonstrate more significant variability in physical and chemical composition, creating challenges in preprocessing and conversion stability. The primary uncertainty sources include: (1) Feedstock availability - substantial fluctuations in biomass quality, quantity, and timelines; (2) Logistical challenges - transportation density variations and geographical dispersion of feedstock; (3) Conversion process stability - inconsistent feedstock characteristics affecting conversion rates; and (4) Market interlinkages - biofuel prices heavily reliant on ever-changing crude oil prices [1] [2].

Q2: How can researchers effectively model the impact of extreme weather events on biofuel supply chain resilience?

A: Climate risk management for BSCs requires integrated approaches that account for increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events. Recommended methodologies include: (1) Dynamic Bayesian Networks (DBN) - allowing for temporal modeling of disruption and recovery trajectories, as demonstrated in COVID-19 impact studies that projected 1-year recovery from maximum damage but 5-year full recovery [7]; (2) Scenario-based robust optimization - incorporating climate projection data to test network resilience under various climate scenarios [8]; (3) Agent-based simulation - modeling interactions across supply chain nodes under disruption scenarios to evaluate resilient policies [1]. Particular attention should be paid to perennial biomass crops and their regional vulnerability to projected climate hazards, with adaptation strategies including diversified feedstock sourcing, distributed preprocessing infrastructure, and flexible logistics planning [8].

Q3: What computational methods are most effective for addressing price volatility in biofuel techno-economic analysis?

A: Traditional deterministic TEA methods are insufficient for capturing the profound effects of market price volatility observed in biofuel systems [6]. Superior approaches include: (1) Stochastic TEA with Monte Carlo simulation - specifically quantifying the effects of uncertainty and volatility of critical variables including biofuel, biochar and feedstock prices, discount rate, and capital investment [6]; (2) Machine learning-enabled TEA - harnessing ML methods to rapidly estimate techno-economic uncertainty without iterative process simulation calls [4] [5]; (3) Real options analysis - incorporating flexibility in investment decisions to respond to market price movements. Research indicates that market prices for biofuel and co-products have the largest impact on net present value of any variable considered, due in part to the high levels of uncertainty associated with future prices [6].

Q4: How do carbon policies introduce uncertainty in biofuel supply chain design, and how can these be incorporated into optimization models?

A: Carbon policies represent significant regulatory uncertainties that profoundly influence BSC configurations and economic viability [3]. Four primary policies must be considered: (1) Carbon cap - limiting total allowable emissions; (2) Carbon tax - establishing a penalty per unit of carbon emitted; (3) Carbon trade - creating markets for buying/selling emission allowances; and (4) Carbon offset - allowing purchase of additional carbon allowances [3]. Effective modeling approaches include: (1) Multi-objective optimization - simultaneously addressing economic, environmental, and social dimensions under different policy scenarios; (2) Fuzzy interactive programming - handling imprecise parameters in policy implementation; (3) Scenario-based robust optimization - developing solutions that perform well across various policy realities. Empirical studies indicate that implementing carbon trade policy can reduce emissions by more than 30% while increasing total profit by about 27% in optimized supply chains [3].

Technical Support: Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Inaccurate Minimum Fuel Selling Price (MFSP) Estimates in Techno-Economic Analysis

Symptoms: Large discrepancies between projected and actual biofuel production costs; inability to explain variance in financial outcomes across similar facilities; underestimation of capital and operational expenses.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Input Parameter Distributions: Ensure stochastic TEA incorporates appropriate probability distributions for all key input variables, with particular attention to feedstock prices and conversion efficiencies which demonstrate high volatility [6].

- Implement Machine Learning Facilitation: Adopt ML-enabled TEA frameworks to rapidly generate probability distributions of MFSP across thousands of scenarios, identifying key drivers of uncertainty through feature importance analysis [4] [5].

- Incorporate Policy Risk Premium: Include "changing policy or regulatory framework" as a key risk variable, which research identifies as the most important cause of risk in biofuel supply chains [9].

- Validate with Historical Data: Compare model projections against operational data from existing facilities, adjusting input distributions to reflect observed variances in financial performance.

Root Cause Analysis: Traditional deterministic TEA approaches fail to capture the high levels of uncertainty and volatility inherent in biofuel markets, particularly for novel production pathways without established operational history [6]. Optimism bias in the biofuel industry leads to unrealistic expectations from complex technologies and dubious claims about resource availability [9].

Issue 2: Unanticipated Supply Chain Disruptions from External Shocks

Symptoms: Sudden feedstock shortages; logistics network failures; labor availability constraints; rapid demand fluctuations.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Develop Dynamic Risk Models: Implement Dynamic Bayesian Networks (DBN) to model temporal evolution of disruption and recovery processes, as demonstrated in pandemic impact studies [7].

- Establish Redundancy Mechanisms: Design supply chains with multiple feedstock sourcing options, flexible transportation modes, and distributed preprocessing capabilities to enhance resilience.

- Monitor Leading Indicators: Track economic, policy, and environmental indicators that provide early warning of potential disruptions, such as policy announcements, commodity price trends, and climate patterns [8].

- Implement Adaptive Control Policies: Develop response protocols for various disruption scenarios, including inventory adjustment, production rescheduling, and logistics rerouting.

Root Cause Analysis: Biofuel supply chains are particularly vulnerable to external disruptions due to their complex interdependencies, biological components, and policy dependence [1] [7]. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that biomass feedstock gate availability could drop to as low as 2% under lockdown conditions, requiring up to five years for full recovery [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for BSC Uncertainty Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for BSC Uncertainty Research

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Functionality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Simulation Software | Aspen Plus, SuperPro Designer, CHEMCAD | Techno-economic model development | Detailed process modeling, mass and energy balances, capital and operating cost estimation |

| Machine Learning Libraries | scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch, XGBoost | ML-enabled TEA, uncertainty quantification | Rapid prediction of economic metrics, feature importance analysis, pattern recognition in complex datasets |

| Optimization Frameworks | GAMS, AMPL, AIMMS, Python Pyomo | Supply chain design under uncertainty | Multi-objective optimization, stochastic programming, resilience modeling |

| Risk Analysis Platforms | @RISK, Palo Alto, ModelRisk | Stochastic Monte Carlo simulation | Probability distribution modeling, risk quantification, scenario analysis |

| Supply Chain Modeling Tools | AnyLogistix, Supply Chain Guru, Llamasoft | BSC network design and simulation | Network optimization, disruption scenario testing, resilience metric calculation |

| Sustainability Assessment | OpenLCA, GaBi, SimaPro | Environmental impact quantification | Life cycle assessment, carbon footprint calculation, sustainability metric integration |

The research reagents and computational tools outlined in Table 3 represent essential infrastructure for investigating and managing uncertainties across biofuel supply chain generations. Process simulation software forms the foundation for techno-economic assessment, enabling researchers to model complex conversion processes and estimate baseline economic performance [4]. Machine learning libraries have emerged as critical components for advancing beyond traditional stochastic analysis, dramatically decreasing the time required to estimate uncertainty of key metrics like MFSP while improving understanding of synergistic effects between input variables [4] [5].

Specialized risk analysis platforms facilitate robust Monte Carlo simulation, allowing researchers to quantify the effects of uncertainty and volatility in critical variables including feedstock prices, conversion rates, and policy impacts [6]. When integrated with supply chain modeling tools, these platforms enable comprehensive resilience testing across network configurations, transportation modes, and facility locations. Sustainability assessment software provides essential capabilities for evaluating environmental dimensions across biofuel generations, particularly important when assessing trade-offs between different feedstock options and processing pathways [3].

Methodological Framework for BSC Uncertainty Analysis

The systematic examination of biofuel supply chain generations reveals distinct risk profiles that require tailored methodological approaches for effective uncertainty management. First-generation chains primarily face socioeconomic uncertainties related to food-fuel competition, while subsequent generations introduce increasingly complex technical and logistical challenges. Across all generations, market price volatility and policy instability represent consistent sources of uncertainty that can profoundly impact financial viability.

Advanced computational methods including machine learning-enabled TEA, dynamic Bayesian networks, and multi-objective optimization under policy constraints provide powerful approaches for quantifying and managing these uncertainties. The integration of these methodologies into cohesive research frameworks enables more resilient biofuel supply chain design capable of withstanding disruptions while maintaining economic and environmental performance. As the bioenergy industry continues to evolve, further development of these analytical approaches will be essential for supporting the sustainable deployment of advanced biofuel technologies across the generational spectrum.

Foundational Knowledge: Understanding Biomass Variability

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary sources of uncertainty in biomass feedstocks? Uncertainty in biomass feedstocks arises from numerous sources, which can be categorized as follows [10]:

- Inherent Biological Variation: Chemical composition (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, ash content) varies significantly between biomass types (e.g., woody vs. herbaceous) and even within the same species due to genetic differences [10].

- Environmental and Agricultural Factors: Weather conditions, soil type, water availability, and seasonal harvest times cause major fluctuations in yield and moisture content from year to year and season to season [11] [12].

- Logistical and Handling Factors: Harvesting practices, storage conditions, and transportation methods can lead to physical variability (particle size, density) and issues like spoilage or contamination [13] [10].

- Technical Factors: Different analytical methods and techniques for measuring the same biomass property (e.g., composition, heating value) can report different values, adding a layer of apparent variability [10].

How does biomass variability impact different biofuel conversion processes? The impact is process-dependent, as summarized in the table below [10]:

| Conversion Process | Impact of Variability |

|---|---|

| Fermentation | High lignin/ash can inhibit reactions; variable carbohydrate content alters ethanol yield [10]. |

| Pyrolysis | High ash content reduces bio-oil yield; variable moisture requires more pre-processing energy [10]. |

| Hydrothermal Liquefaction | High moisture content is less detrimental, but ash can foul reactors [10]. |

| Direct Combustion | Inconsistent moisture and ash lower efficiency, increase slagging/fouling, and raise emissions [10]. |

Can the risks from seasonal biomass availability be quantified? Yes. Research analyzing a 20-year timeframe for agricultural residues in the Peace River region of Canada revealed extreme year-to-year volatility [12]. In some years, biomass availability could drop to less than 10% of average levels [12]. This "boom or bust" supply pattern poses a major risk for any facility requiring a consistent feedstock supply and necessitates strategic planning for feedstock diversification or storage [12].

Troubleshooting Common Biomass Handling Problems

Flowability Issues in Storage and Handling Systems

Problem: My biomass feedstock is bridging, ratholing, or segregating in the hopper, causing an inconsistent feed to the reactor.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Bridging (Material forms an arch over the outlet) | Cohesive strength from moisture or particle interlocking [13]. | ► Implement pre-processing like drying or size reduction [13]. ► Redesign equipment with steeper hopper walls or mass flow design to promote uniform flow [13]. |

| Ratholing (Material forms a stable channel, leaving stagnant zones) | Cohesive arching that does not collapse [13]. | ► Use bin activators or air blasters to disrupt stable channels [13]. ► The most effective long-term solution is to redesign the storage vessel for mass flow [13]. |

| Segregation (Particles separate by size/density, causing inconsistent feed) | Handling methods (e.g., pouring) that allow particles to separate [13]. | ► Modify transfer points to minimize free-fall and dust generation [13]. ► Use a split-inlet for filling bins to distribute different particles evenly [13]. |

| Caking (Material forms hard lumps) | Moisture absorption and compaction under storage pressure [13]. | ► Control storage humidity and temperature [13]. ► Reduce storage time and implement first-in, first-out inventory management [13]. |

Recommended Protocol: Material Characterization Before designing or modifying equipment, conduct a formal material characterization study [13]. This involves measuring key properties like moisture content, particle size distribution, bulk density, and cohesive strength. This data is critical for engineers to design bins, hoppers, and feeders that will function reliably with your specific biomass feedstock [13].

Variability in Experimental & Analytical Results

Problem: My microbial biomass composition measurements are inconsistent between sequencing runs or sample dilutions.

Diagnosis and Solution: This is a classic issue in microbiomics and bioengineering, often related to technical variation and low input biomass [14].

- Cause 1: Low Input Biomass. When analyzing low-biomass samples, stochastic variation during PCR amplification can make estimates of relative abundance unreliable [14].

- Solution: Ensure your input DNA exceeds the critical threshold. Studies suggest estimates become unreliable below approximately 100 copies of the 16S rRNA gene per microliter [14]. Use qPCR to measure absolute gene copy number prior to sequencing.

- Cause 2: Inter-Assay Variation. Technical differences between sequencing runs (reagent lots, machine calibration) can introduce batch effects [14].

- Solution: Include a standardized mock community (a known mix of bacterial strains) in every sequencing run. This allows you to quantify the technical variation (intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation) and correct for it in your data analysis [14].

Recommended Protocol: Standardized GC/MS for Biomass Composition For consistent quantification of microbial biomass components (protein, RNA, lipids, glycogen), adopt a single-platform method using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) with isotope ratio analysis [15].

- Generate Internal Standard: Grow your microorganism (e.g., E. coli) on fully 13C-labeled glucose to create "fully labeled" biomass [15].

- Sample Preparation: Mix a known amount of your unlabeled experimental biomass with a known amount of the fully 13C-labeled internal standard [15].

- Derivatization and Analysis:

- Amino Acids: Hydrolyze with HCl, derivative with MTBSTFA, and analyze by GC/MS [15].

- RNA & Glycogen: Hydrolyze with HCl, prepare aldonitrile propionate derivatives, and analyze for ribose (from RNA) and glucose (from glycogen) [15].

- Fatty Acids: Perform methanolysis to create Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs) and analyze by GC/MS [15].

- Quantification: Use isotope ratio analysis to compare the unlabeled (M0) and fully labeled (M+n) peaks for each analyte. This internal standard corrects for losses during preparation, ensuring high accuracy and precision [15].

Standard Operating Procedures & Methodologies

Workflow for Characterizing Biomass Chemical Composition

The diagram below outlines a standard workflow for the proximate and ultimate analysis of biomass, a cornerstone for understanding its quality and energy potential.

Key Considerations:

- High Variability: Biomass chemical composition is highly variable. When data is recalculated to a dry, ash-free basis, the characteristics show narrower ranges, highlighting the importance of moisture and ash control [16].

- Ash Significance: The content and composition of ash (inorganics) are critical, as they can cause slagging, fouling, and corrosion during thermochemical conversion processes [16] [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents for conducting rigorous biomass composition analysis, particularly following the GC/MS protocol described above [15].

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| [U-13C]Glucose | Generation of uniformly 13C-labeled internal standard biomass for accurate isotope ratio quantification [15]. |

| Custom Bacterial Mock Community | A defined mix of bacterial strains used to quantify technical variation (precision and accuracy) in 16S rRNA gene sequencing runs [14]. |

| MTBSTFA + 1% TBDMCS | Derivatization agent used to prepare tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) derivatives of amino acids for GC/MS analysis [15]. |

| Hydroxylamine Hydrochloride in Pyridine | Used in the preparation of aldonitrile propionate derivatives of sugars (e.g., ribose, glucose) for GC/MS analysis [15]. |

| Propionic Anhydride | Acylating agent used in conjunction with hydroxylamine hydrochloride for sugar derivative formation [15]. |

| Standardized Biomass Reference Materials | Well-characterized biomass samples from organizations like NIST used for method validation and cross-laboratory comparison [10]. |

Advanced Strategic Planning

Modeling Supply Chain Resilience

To manage the profound uncertainty in biomass supply chains, researchers are increasingly moving beyond deterministic models. A review of 205 papers highlights the following strategic approaches [1]:

- Embrace Stochastic Modeling: Use optimization under uncertainty (e.g., two-stage stochastic programming) to design supply chains that are resilient to fluctuations in feedstock quantity, quality, and cost [1].

- Explore Machine Learning: Machine learning techniques show high potential for risk identification, demand prediction, and parameter estimation, but are currently underutilized in the field [1].

- Develop Resilient Policies: Use agent-based simulation to analyze and test various policies (e.g., multi-sourcing, pre-positioned inventory) for their ability to help the biofuel supply chain adapt to and recover from disruptions [1].

The following diagram illustrates the core operations of a biofuel supply chain and the primary sources of uncertainty that must be managed at each stage to ensure resilience [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common sources of uncertainty in biofuel production and conversion? Uncertainties are typically categorized by their origin in the supply chain. The table below summarizes the primary sources and their impacts.

Table: Major Sources of Uncertainty in Biofuel Production and Conversion

| Uncertainty Category | Specific Examples | Potential Impact on the Supply Chain |

|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Supply & Yield | Biomass yield fluctuations due to pests, weather, fires, and climate change [17] [1] [18]. | Reduced biomass availability, increased purchasing costs, disruption to production plans [17] [18]. |

| Operational & Conversion | Disruptions in pretreatment, enzyme hydrolysis, and microbial fermentation processes; technological failures [1] [19]. | Lower conversion efficiency, reduced biofuel yield, increased production costs, and facility downtime [19]. |

| Demand & Market | Fluctuations in biofuel demand and price; changing crude oil prices [20] [1]. | Revenue instability, challenges in planning and budgeting, investment uncertainty [20] [21]. |

| Logistical & Infrastructural | Transportation uncertainties; variability in biomass quality and moisture content [20] [18]. | Increased logistics costs, scheduling difficulties, and potential bottlenecks in feedstock delivery [22] [18]. |

| Policy & Regulatory | Changing policy or regulatory frameworks, such as tax implications and sustainability standards [9] [21] [23]. | Creates market ambiguity, can render operations non-compliant or economically unviable [21] [23]. |

Q2: What mathematical modeling approaches are best suited for managing these uncertainties? The choice of model depends on data availability and the decision-maker's risk tolerance. The following table compares three prominent approaches.

Table: Mathematical Modeling Approaches for Biofuel Supply Chain Uncertainty

| Modeling Approach | Key Principle | Data Requirement | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Programming | A risk-neutral approach that optimizes the expected performance across a set of possible future scenarios [17]. | Requires sufficient historical data to estimate the probability distributions of uncertain parameters [17]. | Planners with access to reliable data who wish to optimize average performance [17]. |

| Robust Optimization | A risk-averse approach that seeks a solution that remains feasible and near-optimal for all, or most, realizations of uncertainty within a defined set [17]. | Does not require precise probability distributions; uses uncertainty sets [17]. | Situations with limited historical data or a need to protect against worst-case scenarios [17]. |

| Simulation-Optimization | Combines optimization to generate plans with simulation (e.g., Discrete-Event Simulation) to test those plans under various disruptive scenarios [18]. | Can incorporate historical data and expert knowledge to model system dynamics and disruptions [18]. | Analyzing complex system behavior, performing "what-if" analysis, and evaluating resilience of different strategies [18]. |

The workflow for selecting and applying these models can be summarized as follows:

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Managing Biomass Yield Fluctuations and Supply Disruptions

Background: Biomass yield is highly susceptible to disruptions like wildfires, pests, and extreme weather, which are low-probability but high-impact events [17] [18]. These can cause a sudden and significant drop in available feedstock.

Methodology: A Simulation-Optimization Framework for Disruption Planning This integrated methodology helps create resilient operational plans [18].

Develop a Base Optimization Model:

- Objective: Minimize total system cost (e.g., biomass purchase, transportation, storage).

- Decision Variables: Determine optimal biomass flow from supply nodes to storage terminals and biorefineries; allocate resources.

- Constraints: Include biomass availability at each node, storage terminal capacity, and meeting demand at the biorefinery [18].

Generate Disruption Scenarios:

- Model specific disruptive events (e.g., a wildfire reducing biomass yield in a key supply region by 50-80%) [18].

- Define the timing and duration of the disruption within the planning horizon.

Simulate and Re-plan:

- Use Discrete-Event Simulation (DES) to run the disruption scenarios on the system.

- Use the optimization model as a re-planning tool once a disruption occurs. Re-optimize resource allocation and transportation routes based on the new, reduced biomass availability [18].

Evaluate Key Performance Indicators (KPIs):

- Monitor costs, demand fulfillment rates, and resource utilization.

- Compare KPIs from the disrupted scenario with the base plan to quantify the impact and the effectiveness of the re-planning strategy [18].

Corrective Actions:

- Strategic: Diversify biomass sourcing locations to reduce dependency on a single region [17].

- Tactical: Utilize intermediate storage terminals to build strategic inventory buffers for critical supply nodes [18].

- Operational: Implement the simulation-optimization DSS for real-time re-routing and re-allocation of biomass during a disruption [18].

Issue: Overcoming Operational Disruptions in the Conversion Process

Background: The biochemical conversion of lignocellulosic biomass involves complex steps like pretreatment, hydrolysis, and fermentation, which are prone to technical failures, inefficiencies, and variability in output [19].

Methodology: Robust Process Design and Tech Qualification This protocol focuses on ensuring operational reliability and securing support for new technologies.

Technology Screening and Piloting:

- Action: For new pretreatment or hydrolysis technologies, move beyond lab-scale validation.

- Procedure: Conduct larger pilot tests to generate performance data (e.g., conversion efficiency, catalyst life, downtime) under conditions that mimic full-scale operation [23].

Data Collection for Insurance and Risk Transfer:

- Action: Systematically document the pilot performance data.

- Procedure: Create a robust portfolio of technical references and performance guarantees from technology providers. This portfolio is critical for communicating with insurance markets and demonstrating that the technology is a known and manageable risk [23].

Process Integration and Layout Optimization:

- Action: Model the physical layout of the biorefinery to mitigate cascading failures.

- Procedure: Use data and analytics to model the impact of an incident (e.g., a release from a vessel). Optimize the spacing of equipment during the design phase to reduce risk exposure [23].

Corrective Actions:

- For Novel Technologies: Engage with insurance markets early, providing pilot data to build confidence and secure coverage for costly investments [23].

- For Process Stability: Invest in advanced process control systems and robust catalyst management to maintain consistent conversion yields [19].

- For Economic Viability: Develop a portfolio of co-products (e.g., chemical precursors, animal feed) to improve the economic resilience of the biorefinery against operational upsets [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Methodologies for Managing Production and Conversion Uncertainty

| Tool / Methodology | Function in Uncertainty Management |

|---|---|

| Stochastic Programming Models | Provides a framework for optimizing biofuel supply chain design (e.g., facility location, capacity) under parameter uncertainty, minimizing expected cost [17]. |

| Robust Optimization Models | Used to design a supply chain configuration that is protected against the worst-case realization of uncertainties, such as severe disruptions [17]. |

| Discrete-Event Simulation (DES) | Models the operation of a biorefinery or supply chain as a discrete sequence of events over time, allowing researchers to test the impact of disruptions and operational variability [18]. |

| Benders Decomposition Algorithm | An exact solution algorithm used to solve large-scale, complex optimization models (like those for supply chain design) within a reasonable timeframe [17]. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | A methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts of biofuel production, which is crucial for complying with sustainability regulations and assessing the true ecological footprint [24] [22]. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and methodologies for researchers managing economic and market uncertainties within biofuel supply chains (BSCs). The content is structured to support the experimental and strategic planning phases of biofuel research and development.

Frequently Asked Questions: Managing Economic and Market Uncertainty

What are the primary economic risks in a biofuel supply chain? Economic risks are predominantly categorized as price volatility, demand shifts, and policy impacts. Key uncertainties include fluctuating feedstock and biofuel prices, evolving biofuel demand driven by blending mandates, and changes in trade policies or credit structures that can reshape market dynamics abruptly [25] [20] [1].

How can we model feedstock price volatility in our techno-economic analysis? Incorporate stochastic modeling or scenario analysis to handle price volatility. For instance, global vegetable oil prices, driven by biofuel demand, can be modeled using historical data and forecasts. As of late 2025, soybean oil faced downward pressure, while palm oil prices were boosted by policy changes in Indonesia [25] [26]. The table below provides a quantitative snapshot of key feedstocks.

Our research involves second-generation feedstocks. How do their supply uncertainties differ? Second-generation (lignocellulosic) biomass supply faces different uncertainties compared to first-generation (edible) feedstocks. These include greater seasonal yield variation, logistical challenges due to biomass bulkiness, and quality fluctuations [1]. Modeling these requires specific parameters for harvest windows, storage losses, and transportation costs.

What methodologies can improve the resilience of our biofuel supply chain model? Beyond traditional stochastic programming, explore machine learning techniques for more accurate demand prediction and risk identification. Additionally, agent-based simulation can be used to analyze resilient policies and evaluate the impact of emerging technologies on BSC resilience [1].

How do recent policy shifts in the US and EU affect near-term biofuel demand? Both regions are undergoing significant policy updates. In Europe, RED III implementation is driving higher renewable fuel demand, with 2026 targets forcing countries to scale up quickly [25]. In the US, new regulatory announcements are affecting domestic and international compliance credit structures, influencing demand patterns for specific biofuel pathways [25].

Troubleshooting Guides: Data and Protocol Support

Guide 1: Quantifying Price Volatility and Policy Impacts

Issue: Researcher needs validated, recent price data and policy benchmarks for economic modeling.

Objective: Integrate current market data and policy targets into techno-economic models to improve forecasting accuracy under uncertainty.

Experimental Protocol & Data: This protocol utilizes publicly available data from industry reports and price benchmarks.

- Step 1: Data Acquisition - Source historical and forecast price data for key feedstocks and biofuels from relevant commodity insights platforms and organizational reports [26].

- Step 2: Policy Benchmarking - Compile current and announced blending mandates from official government sources and trackers for key regions [25] [27].

- Step 3: Model Integration - Input the collected data into a stochastic or scenario-based model to test the economic resilience of your biofuel process or supply chain under various market conditions.

Structured Data for Modeling:

Table 1: Selected Biofuel Feedstock Price Indicators (Late 2025)

| Feedstock | Indicator / Location | Price | Note / Trend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Palm Oil | FOB Indonesia (CPO) | $1,065/mt (Nov loading) |

Supported by Indonesia's 2026 mandate hike [26] |

| Soybean Oil | CBOT Futures (Dec) | 51.10 cents/lb |

Downward pressure in 2025, potential 2026 rebound [25] [26] |

| Soybean Oil | FOB Paranagua (Dec) | Increased (Nov 11) | Firm demand from Brazil and US biofuel sectors [26] |

Table 2: Key Biofuel Policy Drivers and Demand Outlook

| Region | Policy / Mandate | Impact on Demand & Key Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| European Union | RED III Implementation | Aggressive targets forcing rapid scale-up of renewable fuels; substantial demand pressure expected in 2026 [25] |

| Indonesia | Biodiesel Blending Increase | Planned increase in mandate for 2026 is tightening palm oil market and supporting prices [26] |

| Argentina | Biodiesel Blending Mandate | Temporarily reduced from 7.5% to 7% due to soaring soybean oil costs [26] |

| United States | New Regulatory Announcements | Creating broad implications for domestic and international compliance credit structures [25] |

Guide 2: Mapping Supply Chain Uncertainty for Resilience Planning

Issue: Modeling the complex, interconnected nature of uncertainties across the biofuel supply chain.

Objective: To visually map and understand the major sources of uncertainty and their interconnections to prioritize resilience strategies in research and planning.

Experimental Protocol: This methodology involves a systematic literature review and qualitative system mapping to identify risk nodes.

- Step 1: System Decomposition - Break down the Biofuel Supply Chain (BSC) into its core operational modules: Biomass Production, Harvest/Pre-treatment, Storage, Transportation, Conversion, and Distribution [1].

- Step 2: Uncertainty Identification - For each module, identify specific uncertainties (e.g., raw material supply, production yield, demand, price, logistics) [20] [1].

- Step 3: Interconnection Mapping - Diagram how uncertainties in one node (e.g., feedstock supply) propagate to others (e.g., conversion plant utilization), creating ripple effects [1].

Visualization of Biofuel Supply Chain Uncertainties:

Uncertainty Propagation in Biofuel Supply Chain - This diagram shows how uncertainties (yellow) affect core BSC modules (blue) and create ripple effects (green dashed lines).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools for Biofuel Supply Chain Research

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Programming Models | Incorporates uncertainties (e.g., yield, price) into optimization models for strategic/tactical planning [20] [1]. | Determining optimal biorefinery locations and capacity under feedstock supply uncertainty. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Identifies risks, predicts demand, and estimates model parameters from complex datasets [1]. | Forecasting regional biofuel demand based on economic indicators and policy announcements. |

| Agent-Based Simulation | Models interactions between supply chain actors (farmers, refiners) to analyze policy impacts and emergent resilience [1]. | Evaluating the impact of a new carbon credit system on feedstock sourcing strategies. |

| Fundamentals-Based Market Services | Provides long-term supply, demand, and price forecasts to guide strategic assumptions [27]. | Sourcing data for scenario analysis in techno-economic assessment (TEA) and life-cycle assessment (LCA). |

| Geospatial Information Systems (GIS) | Analyzes optimal locations for biomass collection, storage, and biorefineries based on spatial data. | Minimizing transportation costs and logistical complexity in supply chain network design. |

Logistical and Environmental Challenges in Transportation and Storage

For researchers and scientists developing next-generation biofuels, managing the technical and economic uncertainties within the supply chain is a critical component of successful technology deployment. The journey from laboratory-scale innovation to commercial viability is fraught with challenges, particularly in the logistics of transporting diverse feedstocks and the complexities of storing unstable fuel products. These challenges are not merely operational; they represent significant sources of risk that can determine the feasibility and environmental footprint of entire biofuel pathways. This technical support center provides targeted guidance to address these specific experimental and planning hurdles, framed within the broader research context of creating resilient and sustainable biofuel systems. The inherent uncertainties in biofuel supply chains—from feedstock seasonality and policy shifts to the material compatibility of storage systems—require methodical troubleshooting and robust experimental protocols, which are detailed in the following sections.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary logistical bottlenecks when scaling biofuel production from pilot to commercial scale? The transition from pilot to commercial scale introduces several critical logistical bottlenecks. Feedstock Availability and Sourcing presents a major challenge, as consistent, high-volume supply of biomass (e.g., agricultural residues, energy crops) must be secured, often in the face of seasonal variability and geographic dispersion [1]. Transportation Infrastructure is another key bottleneck; biofuels and their feedstocks rely on existing chemical tanker and trucking networks, which are facing capacity constraints and volatile freight rates, making reliable shipping complex and costly [28]. Finally, Policy and Economic Uncertainty, such as the expiration of tax credits like the Blender's Tax Credit or delays in Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) announcements, creates market instability that can stifle investment in the necessary logistics infrastructure [29] [30].

Q2: How does feedstock type influence storage and transportation requirements? Feedstock type directly dictates the logistical strategy. First-generation feedstocks (e.g., corn, soybeans) and their derived fuels (ethanol, biodiesel) have well-established but resource-intensive handling protocols [31]. Second-generation feedstocks, such as agricultural residues (corn stover) and woody biomass, are often bulky, geographically dispersed, and can degrade during storage, requiring pre-processing (e.g., pelleting, torrefaction) to improve energy density and stability for transport [1]. Third-generation feedstocks like microalgae pose unique challenges, requiring controlled, often temperature-regulated, transportation and storage to prevent spoilage and maintain viability, which introduces significant cost and complexity [1].

Q3: What are the key environmental trade-offs of expanding biofuel logistics networks? Expanding logistics networks introduces several environmental trade-offs that must be quantified in lifecycle assessments. A primary concern is Carbon Footprint from Land Use Change, where converting forests or grasslands to grow feedstock crops releases massive stored carbon, potentially making the carbon footprint of some crop-based biofuels worse than gasoline [31]. Furthermore, Upstream Agricultural Impacts are significant; increased fertilizer use for feedstock crops leads to water pollution and nitrate contamination in groundwater, while extensive water use for irrigation in drought-prone areas depletes critical aquifers [31]. Finally, logistics expansion can lead to Biodiversity Loss and Ecosystem Damage, as land conversion for monoculture feedstock plantations destroys habitats and reduces landscape carbon storage capacity [31] [32].

Q4: Which analytical techniques are critical for assessing fuel stability and contamination during storage? Ensuring fuel integrity during storage requires a suite of analytical techniques. Chromatography (Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry or GC-MS) is essential for monitoring chemical composition, detecting the formation of degradation products like peroxides or acids, and identifying microbial contaminants. Spectroscopy (Fourier-Transform Infrared or FTIR spectroscopy) is used to track changes in chemical bonds and functional groups, indicating oxidation or the presence of water. Finally, standard Wet Chemical Methods for measuring acidity (Total Acid Number - TAN), water content (Karl Fischer titration), and sediment levels are fundamental for assessing overall fuel quality and predicting stability over time.

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Storage Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Biofuel Storage Stability

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidation & Degradation | Exposure to oxygen, elevated temperatures, or trace metals leading to formation of gums and sediments. | Pass storage tank headspace with an inert gas (e.g., Nitrogen). Use metal deactivators. | Add antioxidant additives upon production. Store in sealed, temperature-controlled environments. |

| Water Contamination | Condensation from temperature cycles, ingress from rain or faulty seals. | Use coalescing filters to separate free water. | Use desiccant breathers on tank vents. Ensure all seals and hatches are watertight. |

| Microbial Growth | Presence of water at the fuel-water interface, providing a medium for bacteria and fungi. | Apply biocides approved for fuel systems. Circulate and filter the fuel. | Strictly control water ingress. Regularly drain water bottoms from storage tanks. |

| Sediment Formation | Oxidation products, microbial biomass, or inorganic contaminants aggregating into particulates. | Filtration of the fuel to remove suspended solids. | Maintain chemical stability (prevent oxidation). Control microbial growth. Use stabilizer additives. |

Transportation and Handling Challenges

Table 2: Addressing Transportation and Handling Challenges

| Challenge | Impact on Experiment/Operation | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Quality Variability | Inconsistent composition leads to unpredictable conversion yields and unreliable experimental data. | Implement strict feedstock specifications and a Certificate of Analysis (CoA). Pre-process (dry, mill) to a standardized form. |

| Material Incompatibility | Biofuels (especially certain biodiesels) can degrade polymers, elastomers, and certain metals in transport and storage systems. | Conduct compatibility tests with all wetted materials (seals, hoses, tank linings). Specify compatible materials like fluoropolymers or stainless steel. |

| Shipping Capacity Constraints | Inability to secure timely transport, leading to experimental delays or feedstock spoilage; higher freight costs. | Develop long-term freight strategies, including potential charters. Explore flexible logistics partners and diversify shipping routes [28]. |

| Regulatory Uncertainty | Sudden policy shifts (e.g., tariff changes, mandate revisions) can alter feedstock costs and disrupt supply chains mid-research [30]. | Build flexible logistics plans. Stay apprised of policy developments and model their potential impact on your supply chain. |

Quantitative Data and Comparisons

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Biofuel Emissions and Land Use (2025 Projections)

| Fuel Type | Estimated CO₂ Emissions per Liter (kg CO₂e/L) * | Feedstock Land Requirement (hectares per TJ energy) | Estimated Emission Reduction vs. Fossil Fuels (%) * | Key Environmental Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn Ethanol | 0.8 - 1.3 [33] | Very High [31] | 50-70% (Disputed, can be lower or negative [31]) | High fertilizer use, water pollution, potential for indirect land-use change. |

| Sugarcane Ethanol | Lower than corn ethanol [33] | High | 50-70% [33] | More efficient growth profile, but still competes with food production. |

| Biodiesel (Soy) | Data not available | Very High [31] | Data not available | Large land footprint; ~40% of U.S. soybean oil used for biofuel supplies <1% of transport fuel [31]. |

| Advanced Biofuels (e.g., Cellulosic) | Significantly lower (Projected) | Low to Medium (on marginal land) | 70%+ (Projected) | Avoids food competition; potential for improved soil carbon with residue management. |

| Fossil Gasoline | 2.5 - 3.2 [33] | Not Applicable | Baseline | Releases geologically sequestered carbon, high lifecycle GHG emissions. |

Note: Emissions are highly dependent on feedstock, production process, and methodology of lifecycle assessment (e.g., inclusion of land-use change).

Experimental Protocols for Supply Chain Research

Protocol: Accelerated Stability Testing for Biofuels

Objective: To predict the long-term storage stability of a biofuel sample by subjecting it to elevated temperatures and monitoring key degradation indicators.

- Sample Preparation: Filter the biofuel sample to remove any pre-existing particulates. Divide into aliquots in clean, clear glass containers (e.g., 100-200 mL).

- Additive Introduction (Optional): To test the efficacy of stabilizers, add different antioxidants or biocides to separate aliquots at recommended concentrations. Include an untreated control.

- Accelerated Aging: Place sealed sample containers in a forced-air oven pre-heated to a controlled temperature (e.g., 43°C or 90°C, as per modified ASTM D7545). Maintain for a defined period (e.g., 4, 8, 12 weeks).

- Periodic Sampling & Analysis: At predetermined intervals, remove samples in triplicate and analyze:

- Peroxide Value (PV): Quantifies primary oxidation products.

- Total Acid Number (TAN): Tracks the formation of acidic degradation products.

- Sediment & Gum Content: Measures insoluble oxidation products via filtration (e.g., ASTM D2274).

- Visual Inspection: Note color changes and clarity.

- Data Interpretation: Plot changes in PV, TAN, and sediment over time. A sharp increase in these parameters indicates poor oxidative stability. Compare treated and untreated samples to evaluate additive performance.

Protocol: Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) of Logistics Footprint

Objective: To quantify the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and energy input associated with the transportation and storage of a biofuel feedstock or product.

- Goal and Scope Definition: Define the functional unit (e.g., 1 MJ of delivered fuel) and system boundaries (cradle-to-gate or well-to-wheels). Include all logistics stages: feedstock transport to biorefinary, biofuel production, storage, and distribution to point of use.

- Lifecycle Inventory (LCI): Collect quantitative data for all inputs and outputs within the system boundaries. Critical data points include:

- Transportation: Distances, modes (truck, rail, ship), and fuel efficiency for each leg.

- Storage: Energy consumption for pumping, heating/cooling, and tank ventilation.

- Inputs: Fertilizer, water, and electricity used in feedstock production.

- Emissions: Direct emissions from machinery and indirect emissions from electricity generation.

- Lifecycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Use specialized software (e.g., OpenLCA, SimaPro) and databases (e.g., Ecoinvent) to convert LCI data into environmental impact categories, most importantly Global Warming Potential (GWP in kg CO₂e).

- Interpretation & Sensitivity Analysis: Analyze the results to identify logistical "hotspots." Conduct sensitivity analyses on key parameters (e.g., transport distance, storage duration) to understand their influence on the overall carbon footprint and to model the impact of potential efficiency improvements.

System Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Biofuel Supply Chain Uncertainty Map

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biofuel Stability and Logistics Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use-Case in Supply Chain Research |

|---|---|---|

| Antioxidants (e.g., BHT, TBHQ) | Inhibit oxidative degradation of biofuels during storage. | Added to biodiesel samples in accelerated aging studies to determine optimal dosage for extending shelf-life. |

| Biocides | Control microbial growth in fuel storage tanks and transportation systems. | Used in experiments to test efficacy against fungal and bacterial contaminants in fuel-water systems. |

| Metal Deactivators | Chelate trace metals (e.g., copper) that catalyze oxidation reactions. | Investigated as an additive to prevent fuel degradation caused by contact with metal shipping components. |

| Analytical Standards (e.g., for FAME, Peroxides, Acids) | Calibrate instruments for precise quantification of fuel components and degradation products. | Essential for GC-MS analysis to monitor chemical changes in fuels subjected to different storage conditions. |

| Desiccant Breathers | Attach to tank vents to prevent moisture ingress from air during storage tank breathing cycles. | Tested in controlled storage experiments to measure their effectiveness in reducing water contamination. |

| Compatibility Test Coupons (Polymers, Elastomers, Metals) | Assess material degradation upon exposure to biofuels. | Used in immersion tests to screen and specify compatible materials for seals, hoses, and storage tank linings. |

Analytical Frameworks: Quantitative Models and AI for Uncertainty Management

Stochastic Programming for Strategic Design Under Uncertainty

Frequently Asked Questions: Troubleshooting Your Stochastic Programming Experiments

FAQ 1: My two-stage stochastic model becomes computationally intractable when I increase the number of scenarios. How can I improve its solvability?

- Problem: The number of constraints and variables in a two-stage stochastic mixed-integer linear program grows linearly with the number of scenarios, leading to long solve times or memory issues for large-scale biofuel supply chain problems [34].

- Solution: Implement a decomposition algorithm. The L-Shaped method, a standard technique for two-stage stochastic programs, can significantly accelerate convergence by breaking the problem into a master problem and multiple sub-problems [35]. For problems considering facility disruptions, an exact Benders Decomposition algorithm with an acceleration technique has been proven effective [17].

- Recommended Experiment: Compare the solve time of your monolithic model solved with a standard solver (e.g., CPLEX in GAMS) against the L-Shaped method for a case study with 50, 100, and 200 scenarios. Expect exponentially increasing solve times for the monolithic model [17].

FAQ 2: What is the practical difference between a risk-neutral and a risk-averse model, and how do I choose?

- Problem: A risk-neutral two-stage stochastic program minimizes expected total cost but may yield solutions that are highly vulnerable to worst-case scenarios, such as severe biomass supply disruptions [36] [34].

- Solution: Integrate a risk measure into your objective function. Conditional Value at Risk (CVaR) is a common coherent risk measure that can be incorporated to obtain robust, risk-averse solutions. It helps control the expected loss in the worst-case tail of the cost distribution, making your supply chain design more resilient [36] [37].

- Experimental Protocol:

- Formulate your base model as a risk-neutral two-stage stochastic program minimizing expected cost.

- Reformulate the objective to a weighted function:

Minimize (1-λ)*Expected_Cost + λ*CVaR. - Solve the model for different values of the risk-aversion parameter

λ(from 0 to 1). - Analyze the Pareto curve of expected cost vs. CVaR to support decision-making [36].

FAQ 3: How can I model the impact of facility disruptions in my biofuel supply chain network?

- Problem: Traditional stochastic models handle operational uncertainties (e.g., demand fluctuations) but not high-impact, low-probability disruption events like biorefinery shutdowns [38] [17].

- Solution: Use a Node Disruption Impact Index within a two-stage stochastic programming framework. This index, which can be adjusted with parameters, quantifies the impact on the total supply chain cost if a specific node (e.g., a biorefinery) is disrupted. This allows you to identify high-risk nodes and design a resilient network that includes mechanisms to mitigate potential disruptions [38].

- Validation: Apply your model to a case study, such as a biofuel supply chain in Guangdong Province. The results should demonstrate that your proposed resilient model maintains a higher market delivery rate at a lower cost compared to traditional models when high-risk nodes are interrupted [38].

FAQ 4: Biomass quality is highly variable. How can I integrate this uncertainty into my logistics network design?

- Problem: Key biomass properties like moisture content and ash content significantly impact conversion yields, equipment maintenance costs, and overall biofuel production efficiency. Ignoring this variability leads to suboptimal and unrealistic supply chain designs [35].

- Solution: Develop a stochastic hub-and-spoke model that explicitly introduces variability in biomass quality parameters. This model should account for the fact that different biomass batches will have different qualities, affecting transportation costs, preprocessing decisions, and final biofuel output [35].

- Expected Outcome: Research shows that incorporating moisture and ash content variability can impact the total investment and operation cost by approximately 8.31% and lead to a different optimal supply chain configuration, including a 44.44% increase in the number of required preprocessing depots to densify biomass and manage quality-related costs effectively [35].

The table below consolidates critical quantitative results from recent studies to guide your experimental design and benchmark your results.

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators and Model Outcomes from Biofuel Supply Chain Studies

| Aspect | Key Finding | Quantitative Impact | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Performance | Benders Decomposition with acceleration for a disruption model | Solved large-scale case study (Iran) efficiently; exact solution times not specified but noted as necessary for NP-hard problems | [17] |

| Biomass Quality Impact | Incorporating moisture/ash content variability in a hub-and-spoke model (Texas case study) | ~8.31% increase in investment & operation costs; different network configuration | [35] |

| Inventory & Quality | Modeling dry matter loss and seasonality (South-central US case study) | 44.44% more depots required in the optimal network | [35] |

| Risk-Averse Modeling | Applying CVaR in a two-stage stochastic model (Izmir case study) | Confirmed risk parameters significantly influence the objective function value; specific cost savings not quantified | [36] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing a Two-Stage Stochastic Programming Model with Risk Aversion

This protocol is foundational for designing a biofuel supply chain under uncertainty in parameters like demand and cost [36].

- Problem Definition: Define your biofuel supply chain network, including biomass suppliers, candidate biorefinery locations, and demand centers.

- Uncertainty Characterization: Identify key uncertain parameters (e.g., biomass yield, electricity demand, transportation costs). Generate a set of discrete scenarios

S, each with a probability of occurrencep_s[34]. - Model Formulation:

- First-Stage Variables: Define strategic "here-and-now" decisions made before uncertainty is realized. These are typically binary (

y ∈ {0,1}) and continuous variables that are scenario-independent. Examples include:y_j: Whether to build a biorefinery at locationj.x_j: Capacity of biorefineryj.

- Second-Stage Variables: Define tactical "wait-and-see" decisions made after a scenario

sis realized. These are usually continuous and scenario-dependent. Examples include:q_{ij}^s: Quantity of biomass transported from supplierito biorefineryjunder scenarios.w_{jm}^s: Amount of biofuel shipped from biorefineryjto demand centermunder scenarios.

- Objective Function: Minimize the sum of first-stage investment costs and the expected second-stage operational costs, potentially adjusted for risk.

- Risk-Neutral:

Min Total_Cost = FirstStage_Cost + Σ_s (p_s * SecondStage_Cost_s) - Risk-Averse with CVaR:

Min Total_Cost = (1-λ)*Expected_Cost + λ*CVaR[36]

- Risk-Neutral:

- First-Stage Variables: Define strategic "here-and-now" decisions made before uncertainty is realized. These are typically binary (

- Solution: Implement the model in an optimization environment like GAMS and solve using a suitable solver (e.g., CPLEX). For large-scale problems, implement the L-Shaped or Benders decomposition method [17] [35].

Protocol 2: Modeling Biomass Quality Variability in Logistics

This protocol extends the basic model to handle uncertainties in biomass quality, which is critical for realistic yield predictions [35].

- Data Collection: For each biomass type and source, collect historical data on key quality parameters: moisture content, ash content, and dry matter loss over time.

- Scenario Generation: Create scenarios that represent joint realizations of quality parameters (e.g., a scenario for "high moisture, low ash" biomass). The probability of each scenario can be derived from historical data.

- Model Integration:

- Introduce parameters for the quality of each biomass shipment in each scenario (e.g.,

moisture_{i,s}). - Modify the biofuel production constraints to be quality-dependent. The conversion yield at a biorefinery becomes a function of the average quality of the biomass input. For example:

Biofuel_Output_{j,s} = Σ_i (q_{ij}^s * Conversion_Rate * (1 - moisture_{i,s})). - Include costs associated with quality, such as extra energy required for drying high-moisture biomass or increased maintenance due to high ash content [35].

- Introduce parameters for the quality of each biomass shipment in each scenario (e.g.,

- Network Design Impact: The model will endogenously decide on the number and location of preprocessing depots needed to manage quality variability, leading to a more cost-effective and resilient network.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This table lists the essential computational and methodological "reagents" required for experiments in stochastic programming for biofuel supply chains.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Methodologies for Supply Chain Optimization

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in the Experiment | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Solver | Solves the mathematical programming model to find the optimal solution. | Commercial solvers like CPLEX (for MILP/LP) are standard in software like GAMS. Essential for prototyping and testing models [17]. |

| Modeling Environment | Provides a high-level language for formulating optimization models. | GAMS (General Algebraic Modeling System) is widely used in the cited research for implementing and solving stochastic models [39] [17]. |

| Risk Measure (CVaR) | Integrates risk aversion into the objective function to hedge against worst-case scenarios. | Conditional Value at Risk is a coherent risk measure. Its parameter, the confidence level α, must be chosen by the decision-maker [36] [37]. |

| Decomposition Algorithm | Breaks a large, complex problem into smaller, manageable sub-problems to reduce solve time. | The L-Shaped Method and Benders Decomposition are canonical for two-stage stochastic programs. Crucial for handling problems with a large number of scenarios [17] [35]. |

| Node Disruption Index | Quantifies the impact of a facility disruption to identify vulnerabilities and design for resilience. | An improved index based on cost changes, with adjustable parameters to trade off economic benefits and resilience [38]. |

| Scenario Generation Method | Creates a discrete set of possible futures to represent uncertainties in model parameters. | Methods range from simple sampling to sophisticated data-driven approaches for building scenario trees, which are foundational for stochastic programming [34]. |

Workflow Diagram: Stochastic Programming for Biofuel Supply Chain Design

The diagram below visualizes the standard workflow for designing a biofuel supply chain using a two-stage stochastic programming approach, integrating the key concepts from the FAQs and protocols.

Strategic Biofuel Supply Chain Optimization Workflow

Quality Variability Integration Logic

For researchers focusing on biomass quality, the following diagram details the logical process of integrating quality variability into the logistics network design, as described in FAQ 4 and Protocol 2.

Integrating Biomass Quality into Network Design

Robust Optimization and Possibilistic Programming for Data-Scarce Environments

The design and management of biofuel supply chains (BSCs) are inherently fraught with technical and economic uncertainties. These range from operational issues, such as fluctuating biomass yields and variable production costs, to disruptive risks, including transportation network failures and natural disasters [40]. In data-scarce environments, where precise probability distributions for these parameters are unavailable, traditional stochastic optimization models can be inadequate or misleading.

This technical support center is designed to equip researchers and scientists with robust optimization (RO) and possibilistic programming (PP) methodologies to effectively manage these uncertainties. RO protects against worst-case scenarios by ensuring solutions remain feasible for all realizations of uncertain parameters within a predefined uncertainty set [41]. PP, particularly useful with epistemic uncertainty, models imprecise parameters using fuzzy sets and membership functions [40]. The integration of these approaches, such as in Robust Possibilistic Flexible Programming (RPFP), provides a powerful framework for developing resilient and cost-efficient BSC networks, enabling your research to contribute to more commercially viable and sustainable biofuel systems [40].

Troubleshooting Guides for Optimization Experiments

Guide: Resolving Infeasible Robust Counterparts

- Problem Description: The robust optimization model returns an "infeasible" result, indicating no solution can satisfy all constraints under the defined uncertainty set.

- Potential Causes:

- Cause 1: The uncertainty set (e.g., budget of uncertainty, box set) is too conservative or large, making the constraints overly restrictive [41].

- Cause 2: The model does not adequately reflect the real-world system's inherent flexibility or capacity for adaptation.

- Solutions:

- Solution 1: Adjust the Uncertainty Set

- Description: Reduce the conservatism of the model by tuning the parameters that control the size of the uncertainty set.

- Step-by-Step Walkthrough:

- Identify the key uncertain parameters causing infeasibility via sensitivity analysis.

- If using a budget of uncertainty (Γ), gradually reduce its value and re-solve the model.

- If using a polyhedral or ellipsoidal set, scale down the set's size and monitor for feasibility.

- Solution 2: Implement Flexible Programming

- Description: Convert "hard" constraints that must be strictly satisfied into "soft" constraints that can be violated at a penalty cost, enhancing solution flexibility [40].

- Step-by-Step Walkthrough:

- Select the critical constraints that are likely causing infeasibility.

- Reformulate each selected constraint by introducing a non-negative deviation variable.

- Add a penalty term, weighted by a cost coefficient, for this deviation variable to the objective function.

- Solution 1: Adjust the Uncertainty Set

- Results: The model should become feasible, yielding a solution that is robust but less conservative, or one that minimizes the cost of inevitable constraint violations.

Guide: Handling Highly Volatile Objective Functions

- Problem Description: The objective function value (e.g., total supply chain cost) exhibits high sensitivity to small changes in the input parameters, making the solution unstable.

- Potential Causes:

- Cause 1: The model's objective is highly sensitive to a specific uncertain parameter.

- Cause 2: The solution is operating at a "knife-edge" point, where any perturbation significantly impacts performance.

- Solutions:

- Solution 1: Apply a Distributionally Robust Approach

- Description: Instead of considering a simple uncertainty set, optimize against a worst-case probability distribution from a family of distributions (an ambiguity set) [41].

- Step-by-Step Walkthrough:

- Define an ambiguity set that captures the limited information you have about the distributions (e.g., known mean and support).

- Reformulate the objective to minimize the expected cost under the worst-case distribution within this ambiguity set.

- Solution 2: Multi-Stage or Adjustable Robust Optimization

- Description: Model some decisions as "wait-and-see" decisions that can be made after some uncertainties are resolved, reducing the burden on the first-stage "here-and-now" decisions [41].

- Step-by-Step Walkthrough:

- Partition decision variables into stages based on the timeline of information revelation.

- Define the decision rules (e.g., linear or piecewise linear) for the adjustable variables.

- Solve the resulting (more complex) multi-stage robust problem.

- Solution 1: Apply a Distributionally Robust Approach

- Results: The resulting solution will be less sensitive to parameter fluctuations and exhibit more stable performance across various realizations of uncertainty.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between robust optimization and possibilistic programming?

- A1: Robust Optimization (RO) defines uncertainty using bounded sets and seeks solutions that are feasible for all realizations within this set, focusing on worst-case performance [41]. Possibilistic Programming (PP) uses fuzzy set theory, where parameters are defined by membership functions representing their degree of possibility, and goals are often to achieve a satisfactory solution with a high degree of possibility [40].

Q2: How do I choose an appropriate uncertainty set for my robust biofuel supply chain model?

- A2: The choice depends on your knowledge of the uncertainties and your risk tolerance. Common sets include:

- Box Set: Simple but can be overly conservative, used when uncertainties are independent.

- Ellipsoidal Set: Less conservative, suitable for capturing correlations between uncertainties.

- Budget of Uncertainty (Polyhedral) Set: Allows you to control the conservatism level by limiting the total scaled deviation of uncertain parameters from their nominal values. This is often a practical choice for BSC applications [41].