Life Cycle Assessment of Wood-Based Electricity: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research Sustainability

This article provides a comprehensive Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) framework for wood-based electricity generation, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields.

Life Cycle Assessment of Wood-Based Electricity: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research Sustainability

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) framework for wood-based electricity generation, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical fields. It explores the foundational principles of LCA, detailed methodology for biomass power, key environmental impact categories, and strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing assessments. By applying a rigorous, multi-intent framework, this guide enables scientific professionals to critically evaluate the environmental footprint of their energy-intensive research activities, such as clinical trials, and supports informed decision-making for enhancing sustainability in biomedical operations.

Understanding Life Cycle Assessment and Woody Biomass Power Fundamentals

What is Life Cycle Assessment? Defining the ISO 14040/14044 Framework

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with a product, process, or service throughout its entire life cycle, from raw material extraction to final disposal [1] [2]. This "cradle-to-grave" analysis provides a comprehensive view, enabling researchers, businesses, and policymakers to make more informed, environmentally conscious decisions [3] [1]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) provides the globally recognized framework for conducting LCA through the ISO 14040 and 14044 standards, which ensure studies are conducted with rigor, consistency, and credibility [3] [4] [5].

The Four Phases of an LCA According to ISO 14040/14044

The ISO framework structures LCA into four interconnected phases [3] [6]. The relationship between these phases is dynamic, with interpretation occurring throughout the process to refine the assessment.

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

This foundational phase establishes the study's purpose, intended application, and audience [3] [5]. It defines the functional unit, which quantifies the performance of the product system, ensuring comparisons are made on a common basis [3] [1]. The system boundaries are also delineated, specifying which processes and life cycle stages are included in the assessment [3]. For wood-based electricity research, a typical functional unit could be 1 Gigajoule (GJ) of exergy, allowing for fair comparison between different energy generation systems [7].

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory Analysis (LCI)

The LCI phase involves compiling and quantifying all relevant inputs (e.g., energy, water, resources) and outputs (e.g., emissions, wastes) for the product system within the defined boundaries [3] [1]. This data collection is one of the most resource-intensive steps and requires decisions on methods for handling data gaps or multifunctional processes, such as allocation [3] [8].

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

In the LCIA phase, the inventory data is translated into potential environmental impacts [1]. This involves selecting impact categories, classifying LCI results into these categories, and using characterization models to quantify the magnitude of contribution to each impact [3]. Common impact categories relevant to energy research are listed in the table below.

Phase 4: Interpretation

Interpretation is the final phase where results from the LCI and LCIA are evaluated against the goal and scope [3]. This involves identifying significant issues, checking the completeness and sensitivity of the data, and drawing conclusions with actionable recommendations [3] [5]. It ensures the assessment is robust and its findings are reliable.

Application in Wood-Based Electricity Generation Research

LCA is instrumental for quantifying the environmental profile of energy generated from wood resources, such as waste wood and forest residues [7]. This is critical for supporting the transition to a wood-based bioeconomy and for validating the sustainability claims of bioenergy [8].

Key Environmental Impact Categories for Energy Systems

The following table summarizes common impact categories used to evaluate wood-based electricity systems, as exemplified in recent studies [7].

| Impact Category | Indicator & Common Unit | Relevance to Wood-Based Energy |

|---|---|---|

| Climate Change | Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂-equivalent) | Measures greenhouse gas emissions over the life cycle, crucial for climate policy [7]. |

| Acidification | Acidification Potential (kg SO₂-equivalent) | Assesses emissions that contribute to acid rain, which can damage ecosystems [1] [7]. |

| Particulate Matter | Particulate Matter Formation (kg PM2.5-equivalent) | Evaluates impacts on human health from fine particle emissions [7]. |

| Eutrophication | Freshwater Eutrophication Potential (kg P-equivalent) | Quantifies nutrient pollution leading to algal blooms in water bodies [1] [7]. |

| Resource Depletion | Cumulative Energy Demand (MJ) | Tracks total (fossil, nuclear, renewable) energy demand across the life cycle [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Consequential LCA with Additives

A 2020 study used a consequential LCA approach to assess the effect of resource-efficient additives (e.g., gypsum waste, halloysite, coal fly ash) in the combustion of waste wood at four European energy plants [7]. The methodology below can serve as a protocol for similar research.

1. Goal and Scope:

- Goal: To understand the environmental impacts of using additives to reduce operational problems (slagging, fouling, corrosion) and improve efficiency in waste wood combustion [7].

- Functional Unit: 1 GJ of exergy, enabling cross-comparison of heat and power generated from different plants [7].

- System Model: Consequential modeling was used to identify the marginal technologies affected by changes in the system (e.g., the avoided electricity mix due to increased efficiency) [7].

2. Life Cycle Inventory:

- Data Collection: Primary operational data (e.g., fuel mix, direct emissions, energy outputs) were collected directly from plant operators for a baseline scenario without additives [7].

- Additive Scenarios: Emission data for scenarios with additives were collected from on-site measurements at the plants [7].

3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment:

- The study calculated impacts for the categories listed in the table above. The LCIA results showed that the use of certain additives could decrease most environmental impacts by an average of 12%, primarily as a consequence of increasing energy generation efficiency, which avoids the use of more polluting marginal energy technologies [7].

4. Interpretation and Sensitivity Analysis:

- A sensitivity analysis was conducted on the expected increase in energy efficiency, testing the robustness of the conclusions [7]. The study found that impacts on acidification could increase significantly (up to 120%) in the absence of appropriate flue gas cleaning systems, highlighting a critical trade-off for researchers and engineers to manage [7].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Concepts and Emerging Methods

Prospective LCA for Emerging Technologies

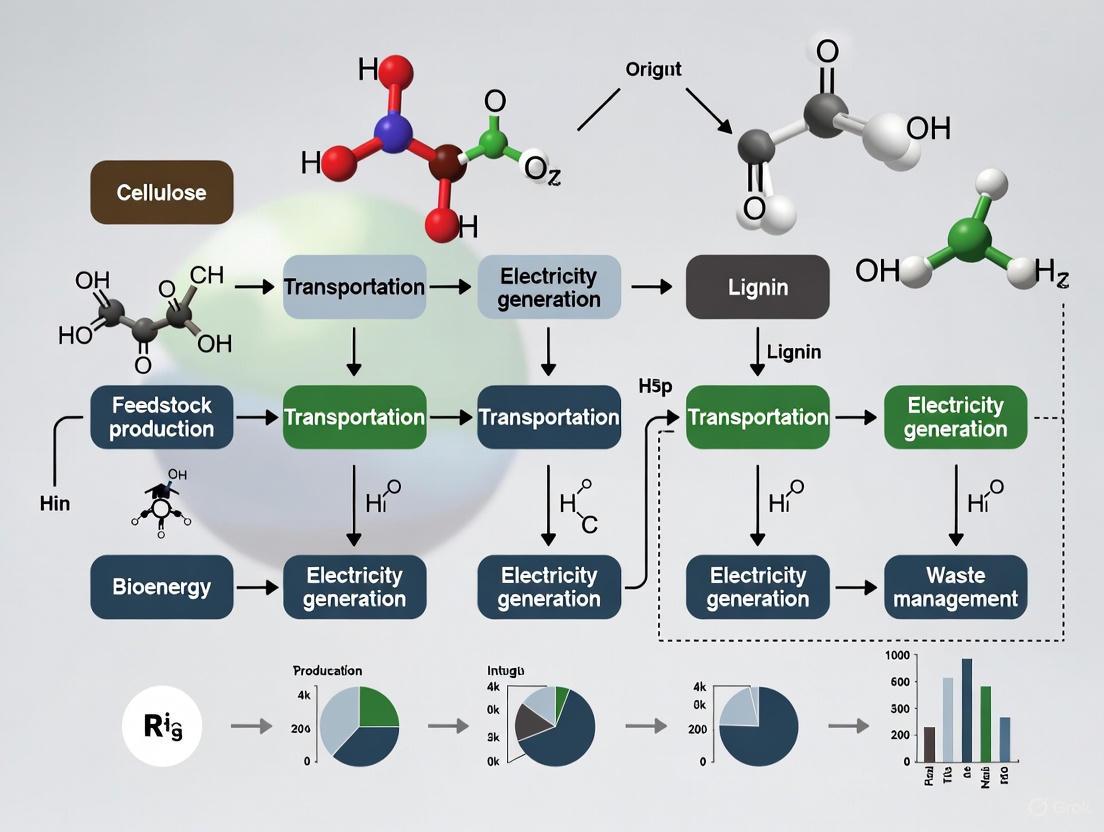

For emerging wood-based technologies (e.g., lignin-based adhesives, novel biofuels), a prospective LCA is used to assess future environmental performance. This involves iterative LCA cycles to handle uncertainties associated with scaling up from laboratory to industrial production [8]. The following diagram illustrates this iterative approach.

For researchers conducting LCAs on bioenergy systems, the following table details key "reagents" or data inputs required to build a robust life cycle model.

| Item / Reagent | Function in the LCA | Example Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Process Data | Provides foreground system data specific to the operation under study. | Direct measurements from pilot or industrial plants, lab experiments, engineering models [7] [8]. |

| Background Database | Provides generic data for upstream/downstream processes (e.g., electricity mix, transport, material production). | Commercial databases (e.g., ecoinvent, GaBi), government data, scientific literature [8]. |

| Impact Assessment Method | Provides the characterization factors that convert LCI data into environmental impact scores. | Methods such as ReCiPe, CML, TRACI, which define the impact categories and calculation rules [3] [7]. |

| Allocation Procedure | Partitions environmental loads when a process produces multiple products. | ISO 14044 provides hierarchy (physical, economic); crucial for biorefineries [3] [4] [8]. |

| Scenario & Sensitivity Tools | Tests how the LCA results are affected by uncertainties in key parameters. | Monte Carlo simulation, local sensitivity analysis on parameters like energy demand and allocation factors [8]. |

In conclusion, the ISO 14040/14044 framework provides the indispensable, rigorous foundation for conducting Life Cycle Assessments. Its structured, four-phase approach ensures that assessments of wood-based electricity generation and other emerging technologies are scientifically sound, transparent, and yield actionable insights for driving genuine environmental improvements.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with a product, process, or service throughout its entire existence [9]. As a scientific tool, LCA enables researchers and sustainability professionals to quantify environmental loads, from resource extraction to final disposal, providing a comprehensive framework for identifying improvement opportunities and avoiding burden shifting between life cycle stages [10] [11]. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) provides the foundational framework for LCA in standards 14040 and 14044, which define the four iterative phases of any LCA study: goal and scope definition, life cycle inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation [6] [11] [9].

The concept of "system boundaries" is fundamental to LCA, determining which life cycle stages are included in the assessment [9]. Different life cycle models represent varying system boundaries, with cradle-to-grave and cradle-to-cradle representing two distinct approaches to conceptualizing a product's environmental journey [10] [12]. For researchers investigating wood-based electricity generation, selecting the appropriate life cycle model is critical for ensuring the comprehensiveness and applicability of their findings to policy and investment decisions in sustainable bioenergy systems [13].

Comparative Analysis of LCA Methodologies

Cradle-to-Grave: The Linear Model

The cradle-to-grave approach represents a comprehensive assessment model that tracks a product's environmental impacts across all five traditional life cycle stages in our linear economy [10] [6]. This methodology begins with raw material extraction (the "cradle"), progresses through manufacturing, transportation, and use phases, and concludes with waste disposal (the "grave") [10]. For energy systems such as woody biomass electricity generation, this would encompass everything from forest management and feedstock collection through processing, electricity generation, and ultimately decommissioning and waste management of the facility [13].

The principal advantage of cradle-to-grave analysis lies in its ability to provide a complete picture of a product's environmental footprint, enabling identification of impact hotspots across the entire value chain [10] [12]. This comprehensive perspective helps eliminate the risk that environmental "improvements" in one stage simply shift burdens to other unassessed phases [10]. For instance, a biomass processing method that reduces energy consumption during manufacturing but produces toxic emissions when incinerated would only reveal this trade-off through a cradle-to-grave assessment. The methodology's main limitations include greater complexity, resource intensity, and challenges in obtaining accurate data for downstream phases, particularly product use and end-of-life treatment [12].

Cradle-to-Cradle: The Circular Model

Cradle-to-cradle represents an innovative life cycle model that exchanges the waste disposal stage with processes that make materials reusable for another product, essentially "closing the loop" in a circular economy approach [10] [6] [12]. Unlike traditional linear models, cradle-to-cradle design emphasizes waste-as-nutrient, where products are conceived to either safely biodegrade and return to biological cycles or become technical nutrients that circulate indefinitely in industrial systems [12] [9].

This approach transforms the conventional LCA framework by considering multiple product life cycles rather than a single journey from creation to disposal. In the context of biomass energy, this might involve assessing how waste streams from electricity generation (such as ash) can be repurposed as agricultural amendments or how production facilities can be designed for material recovery at end-of-life [13]. The certification system for cradle-to-cradle products evaluates multiple criteria including material health, material reuse, renewable energy use, water stewardship, and social fairness [9]. A significant distinction between cradle-to-cradle and traditional LCA is that while the former uses qualitative visions and storytelling to inspire sustainable design, the latter relies on quantitative data to measure environmental impacts [9].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of LCA Methodologies

| Aspect | Cradle-to-Grave | Cradle-to-Cradle |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Foundation | Linear economy | Circular economy |

| End-of-Life Focus | Waste disposal (landfill, incineration) | Recycling/upcycling for new product life cycles |

| Primary Applications | Comprehensive environmental footprinting; Impact hotspot identification | Sustainable product design; Closed-loop system development |

| Key Advantages | Complete environmental profile; Prevents burden shifting | Promotes waste minimization; Enhances resource efficiency |

| Methodological Challenges | Data-intensive; Complex modeling of use and disposal phases | Often more complex and costly; Requires innovative design strategies |

LCA Application in Woody Biomass Electricity Generation

Experimental Data from Recent Research

Recent scientific investigations into woody biomass electricity generation provide compelling quantitative data for comparing different life cycle approaches. A 2025 study published in Biomass and Bioenergy evaluated three distinct woody biomass-based combined heat and power (CHP) scenarios in Türkiye using cradle-to-grave LCA methodology [13]. The researchers assessed global warming potential (GWP) across these systems, with remarkable findings:

Table 2: Environmental Performance of Woody Biomass CHP Systems [13]

| Scenario | Feedstock & Process Description | GWP (g CO₂eq/kWhe) |

|---|---|---|

| Case A | Sawmill residues dried using recovered CHP heat, then pelletized | -15 |

| Case B | Sawmill residues dried using natural gas before pelletization | 74.4 |

| Case C | Direct use of forest residue wood chips without further processing | -78.63 |

The negative GWP values observed in Cases A and C demonstrate the significant greenhouse gas mitigation potential of optimized woody biomass systems, particularly when incorporating heat recovery to improve overall environmental performance [13]. These systems emit far less GHG than fossil-based electricity generation, with Case C showing the most favorable results due to minimal processing and transportation requirements [13].

Methodological Protocols for Biomass LCA

The standardized LCA protocol applied in woody biomass electricity research follows the established ISO 14040/14044 framework, with specific adaptations for bioenergy systems [13] [11]. The goal and scope definition phase must clearly specify the functional unit (e.g., 1 kWh of electricity delivered), system boundaries, and impact categories assessed [11]. For comparative studies, the ISO standards mandate application of identical functional units, system boundaries, allocation procedures, data quality standards, and life cycle impact assessment methods to ensure valid "apples-to-apples" comparisons [11].

The life cycle inventory analysis for biomass energy systems must account for all material and energy flows, including:

- Feedstock Production: Forest management practices, residue collection, transportation

- Processing: Chipping, pelletization, drying methods (natural gas vs. waste heat recovery)

- Conversion: CHP plant efficiency, emission control systems

- Distribution: Electricity transmission infrastructure

- End-of-Life: Waste stream management, byproduct utilization [13]

The impact assessment phase translates these inventory data into environmental impact categories, with global warming potential being particularly relevant for biomass energy studies due to climate change mitigation policies [13]. The interpretation phase involves critical review of data quality, sensitivity analysis, and identification of significant environmental issues [11] [9].

LCA Methodological Framework

Research Reagents and Tools for LCA Implementation

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Life Cycle Assessment

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software Platforms | Ecochain, SimaPro | Systematic modeling and analysis of complex life cycles; Impact quantification across all stages [10] [9] |

| Data Sources | National statistics, Supplier data, Industry averages | Inventory development for raw materials, energy use, transportation, and waste management [10] |

| Impact Assessment Methods | Global Warming Potential (GWP), CML, ReCiPe | Translation of inventory data into environmental impact categories [13] [11] |

| Standardization Frameworks | ISO 14040/14044, ISO 14067, GHG Protocol | Ensuring methodological rigor, transparency, and comparability between studies [14] [11] [9] |

Biomass Energy Life Cycle Models

The selection between cradle-to-grave and cradle-to-cradle approaches depends fundamentally on research objectives, data availability, and intended applications of findings. For comprehensive environmental footprinting of existing woody biomass electricity systems, cradle-to-grave assessment provides the complete picture necessary for identifying impact hotspots and avoiding burden shifting across the value chain [10] [15]. When pursuing innovative bioenergy system designs aligned with circular economy principles, the cradle-to-cradle framework offers the conceptual foundation for creating closed-loop systems that maximize resource efficiency [12] [9].

For the biomass energy research community, both approaches offer complementary insights. Cradle-to-grave assessments of wood-based electricity generation have demonstrated significant GHG advantages over fossil fuel alternatives, particularly when incorporating waste heat recovery and minimizing preprocessing energy requirements [13]. Meanwhile, cradle-to-cradle thinking encourages researchers to conceptualize how biomass residues can be continually repurposed across multiple product systems, potentially enhancing the sustainability credentials of wood-based electricity in a carbon-constrained world.

The global woody biomass power generation market is experiencing significant growth, propelled by the worldwide push for renewable energy and decarbonization. This sector converts organic materials like wood pellets, wood chips, and other forest residues into electricity, providing a dispatchable and sustainable alternative to fossil fuels.

Global Market Size and Projections

The market demonstrates robust growth trajectories, though reported figures vary based on measurement scope (e.g., equipment value vs. total revenue). Table 1 summarizes key market projections.

Table 1: Global Woody Biomass Power Generation Market Outlook

| Base Year | Market Size in Base Year | Projected Market Size | Forecast Period | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Source of Projection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2024 | $90.8 Billion | $116.6 Billion by 2030 | 2024-2030 | 4.3% | Strategic Business Report [16] |

| 2024 | $18.5 Billion | $32.1 Billion by 2034 | 2024-2034 | 5.5% | Emergen Research [17] |

| 2024 | N/A | $134 Million by 2025 | 2025-2033 | 9.2% | Archive Market Research [18] |

Key Market Drivers and Challenges

Several interconnected factors are driving market expansion, while certain restraints pose challenges to industry players.

- Renewable Energy Policies: Government incentives, including production tax credits, feed-in tariffs, and renewable portfolio standards, are primary growth catalysts [18] [16] [19]. For instance, the European Union's Renewable Energy Directive and net-zero targets create a supportive policy framework [17].

- Technological Advancements: Innovations in conversion technologies like gasification and anaerobic digestion are enhancing efficiency, reducing costs, and lowering emissions, making biomass power more competitive [18] [20] [17].

- Energy Security and Waste Management: The drive to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and diversify energy mixes is a significant driver. Concurrently, the use of woody biomass supports waste-to-energy initiatives, aligning with circular economy principles by utilizing forestry and agricultural residues [16] [17].

Conversely, the industry faces headwinds from:

- Supply Chain and Logistics: Ensuring a consistent, cost-effective supply of feedstock is challenging. Transportation alone can constitute up to 30% of total supply chain costs, impacting economic viability [17].

- Regulatory Hurdles and Competition: Adhering to varying sustainability criteria and emissions standards across regions creates complexity. Furthermore, biomass power competes with other renewables like wind and solar, which have seen dramatic cost reductions [17] [19].

- High Capital Costs: The initial investment required for biomass power plants remains substantial, potentially deterring new entrants [18].

Technology Comparison and Performance Data

The performance of woody biomass power generation depends heavily on the conversion technology employed. Each technology offers distinct advantages and trade-offs in terms of efficiency, complexity, and application.

Core Conversion Technologies

The primary pathways for converting woody biomass into energy include combustion, gasification, co-firing, and anaerobic digestion.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Woody Biomass Power Generation Technologies

| Technology | Process Description | Electrical Efficiency | Key Advantages | Key Challenges | Commercial Maturity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combustion | Direct burning of biomass to produce steam that drives a turbine. | ~20-40% [19] | - Technologically mature- Wide fuel flexibility- Reliable base-load power | - Lower efficiency compared to advanced systems- Higher emission levels requiring control | High [20] |

| Gasification | Thermochemical conversion of biomass into a synthetic gas (syngas: CO, H₂, CH₄), which is then used to generate power. | Can exceed 80% for syngas conversion [17] | - Higher overall efficiency- Lower emissions- Syngas can be used for biofuels/chemicals | - Higher capital cost- Complex operation and sensitive to feedstock quality | Medium to High [20] |

| Co-firing & CHP | Co-firing: Blending biomass with coal in existing power plants. CHP: Using the heat from power generation for industrial or district heating. | CHP systems can reach >80% overall energy efficiency [16] | - Leverages existing infrastructure- Cost-effective pathway to reduce emissions- CHP maximizes energy utilization | - Biomass feedstock pre-processing required- Limited by coal plant availability and policies | High for Co-firing; Growing for CHP [20] |

| Anaerobic Digestion | Biological breakdown of organic matter by microbes in the absence of oxygen, producing biogas. | Primarily used for wet feedstocks; efficiency depends on biogas yield. | - Suitable for specific biomass types- Produces biogas and digestate | - Less suitable for dry woody biomass- Slow process, requires careful management | Medium (More common for agri-waste) [18] |

Methodologies for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) in Biomass Energy Research

Life Cycle Assessment is a fundamental methodology for evaluating the environmental impact of woody biomass power generation, from feedstock procurement to energy production. The "resource–supply chain–demand–optimization" spatial operational logic provides a robust framework for structuring this research [21].

Experimental Protocol: Resource Potential and Supply Chain Analysis

This protocol assesses the availability and logistical feasibility of woody biomass feedstocks.

- Objective: To quantify the spatially explicit potential of woody biomass resources and model the associated supply chain costs and emissions.

- Methodology:

- Resource Potential Assessment:

- Data Collection: Gather data on forest cover, growth rates, and residue yields using national forestry inventories, satellite imagery (e.g., LiDAR for canopy height and biomass estimation [22]), and agricultural statistics.

- GIS Mapping: Employ Geographic Information System (GIS) software to map biomass availability, accounting for environmental constraints and sustainable harvest rates [21].

- Supply Chain Modeling:

- Cost Analysis: Model the costs of collection, processing (e.g., chipping, pelletizing), transportation (accounting for up to 30% of costs [17]), and storage.

- Emissions Inventory: Calculate greenhouse gas emissions from each stage, including machinery fuel use and transportation emissions.

- Resource Potential Assessment:

- Data Analysis: Integrate resource and supply chain models to identify optimal locations for collection points and bioenergy plants, minimizing cost and environmental impact.

Experimental Protocol: Technology-Specific Environmental Impact Assessment

This protocol evaluates the environmental performance of different conversion technologies.

- Objective: To compare the energy balance and emission profiles of different biomass conversion technologies (e.g., Combustion vs. Gasification) using a cradle-to-gate LCA.

- Methodology:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Define the functional unit (e.g., 1 MWh of electricity delivered) and system boundaries (feedstock production, transport, conversion, and waste handling).

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI):

- Data Collection: Collect primary data from pilot or commercial plants, or use secondary data from literature and databases. Key inventory data includes:

- Feedstock consumption per MWh

- Auxiliary energy and chemical inputs

- Air emissions (CO₂, CH₄, N₂O, SOₓ, NOₓ, particulate matter)

- Ash and waste generation

- Technology Comparison: Ensure data is normalized per functional unit for a fair comparison between technologies [23].

- Data Collection: Collect primary data from pilot or commercial plants, or use secondary data from literature and databases. Key inventory data includes:

- Impact Assessment: Use LCA software (e.g., OpenLCA, SimaPro) to convert LCI data into impact categories such as Global Warming Potential (GWP), Acidification Potential, and Eutrophication Potential.

- Key Insights: Advanced technologies like gasification typically show a better environmental performance due to higher efficiency and lower air emissions, which must be balanced against their higher initial embodied energy [20].

The workflow below illustrates the logical progression of a comprehensive LCA study for woody biomass power generation.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful research and implementation in woody biomass power generation rely on a suite of analytical tools, software, and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Primary Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | Spatial mapping and analysis for resource assessment and facility siting. | Mapping woody biomass availability and identifying optimal locations for power plants to minimize transport costs [21]. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Software | Modeling and quantifying environmental impacts across the entire value chain. | Conducting a cradle-to-grave analysis to compare the carbon footprint of different biomass conversion technologies [21]. |

| LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) | Remote sensing technology for precise measurement of forest structure and biomass. | Estimating above-ground carbon storage in forests and assessing feedstock availability [22]. |

| Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS) | Analytical instrument for separating and identifying chemical compounds. | Analyzing the composition of syngas produced from biomass gasification to determine its quality and energy content. |

| Process Simulation Software | Modeling and optimizing the thermodynamics and economics of conversion processes. | Simulating a gasification process to maximize syngas yield and overall plant efficiency. |

| Sustainably Sourced Wood Pellets/Chips | Standardized feedstock for experimental trials and pilot-scale testing. | Used as a controlled fuel source in combustion and gasification experiments to ensure consistent and reproducible results [17]. |

Emerging Trends and Future Research Directions

The field of woody biomass power generation is dynamically evolving, with several key trends shaping its future as a critical component of a sustainable energy landscape.

- Integration with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS): Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage is a pivotal emerging technology. It captures CO₂ emissions from biomass power plants for permanent storage, potentially generating carbon-negative energy and playing a vital role in climate change mitigation strategies [18] [16].

- Digitalization and Advanced Analytics: The integration of smart technologies, including IoT sensors, data analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI), is transforming the industry. These tools optimize biomass supply chains, predict maintenance needs, and improve the operational efficiency and grid integration of power plants [16] [17].

- Spatial Planning and Optimization: Future research emphasizes the integration of energy planning with territorial spatial planning. This involves using GIS and spatial analysis to align biomass supply, logistics, and conversion facilities with local energy demand, thereby minimizing environmental impact and maximizing economic and social benefits [21].

- Advanced Bio-products and Circular Economy: Research is increasingly focused on biorefinery concepts that co-produce electricity, advanced biofuels (for transportation), and high-value bio-products like biochar—a soil amendment that sequesters carbon [18]. This aligns with circular economy principles, enhancing the overall sustainability and economic viability of the biomass sector.

While the carbon neutrality of biomass energy is a subject of extensive debate, a comprehensive environmental evaluation must extend far beyond global warming potential to include a broader set of impact categories. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a structured methodology for quantifying these diverse environmental effects across the entire biomass value chain—from feedstock cultivation to energy conversion and end-of-life. For researchers and scientists engaged in developing sustainable energy systems, understanding these multifaceted impacts is crucial for accurate technology assessment and guiding development toward truly sustainable outcomes. This guide examines the core environmental impact categories essential for evaluating wood-based electricity generation, supported by experimental data and comparative analysis of conversion pathways.

Core Environmental Impact Categories in LCA

Life Cycle Assessment evaluates environmental impacts across multiple categories that capture diverse effects on ecosystems and human health. For biomass energy systems, key impact categories beyond climate change include those affecting air quality, soil health, water resources, and ecosystem integrity.

Table 1: Core Environmental Impact Categories for Biomass Energy Systems

| Impact Category | Primary Contributing Flows | Key Significance for Biomass Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Terrestrial Acidification | Emissions of sulfur oxides (SOx), nitrogen oxides (NOx), ammonia (NH3) [24] | Acidification of soils and forests from combustion emissions and fertilizer use; can affect forest health and biomass regrowth. |

| Human Toxicity | Emissions of heavy metals, particulate matter, and organic pollutants to air and water [24] | Health impacts on local populations from direct combustion emissions or releases from chemical processing of feedstocks. |

| Land Use | Land transformation, occupation, and changes in soil organic carbon [8] | Measures direct and indirect land use change impacts; critical for assessing biodiversity loss and carbon stock changes from feedstock cultivation. |

| Particulate Matter Formation | Direct particulate emissions (PM2.5, PM10) and secondary aerosol precursors (SOx, NOx, NH3) [25] | Respiratory and cardiovascular health effects from biomass combustion; significantly higher in obsolete combustion technologies. |

These impact categories are influenced by decisions across the biomass life cycle. The choice of biomass feedstock—whether agricultural residues, dedicated energy crops, or forestry products—significantly affects the resultant impact profile due to differing cultivation requirements, chemical compositions, and conversion efficiencies [26].

Quantitative Impact Comparison of Biomass Technologies

Impact Variation Across Conversion Pathways

Different technological pathways for converting biomass to energy yield distinct environmental profiles. Quantitative LCA results enable direct comparison between these pathways.

Table 2: Comparative LCA Results for Different Biomass Conversion Systems

| Technology / Process | Global Warming Potential (GWP) | Terrestrial Acidification | Human Toxicity | Key Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Pyrolysis (Optimal Parameters) | Varies with parameters (temp, feedstock) [27] | Not specified in results | Not specified in results | Pyrolysis temperature (300–400°C), steam-to-carbon ratio (1.2–1.6), plant capacity [28] |

| Transparent Wood Production (Alkali + Epoxy) | Baseline (24% less than alternative method) [24] | 15% less than NaClO2 + PMMA [24] | 97% less at industrial scale [24] | Delignification chemicals, polymer infiltration type, production scale |

| Biogas to Electricity (Engine) | 120 kgCO2,eq savings/MWh biogas [29] | Not specified in results | Not specified in results | Electricity carbon intensity, heat recovery utilization (increases savings) |

| Biogas to Biomethane (Grid Injection) | 152 kgCO2,eq savings/MWh biogas [29] | Not specified in results | Not specified in results | Natural gas carbon intensity, upgrading efficiency, upstream emissions |

The data demonstrates that optimal design parameters shift significantly depending on which environmental impact category is prioritized [28]. For instance, maximizing energy efficiency in pyrolysis requires different parameters (400°C) than minimizing global warming potential (350°C) or terrestrial acidification (300°C).

Scale and Technology Advancement Effects

The scale of production and technological maturity dramatically influence environmental performance, with industrial-scale processes typically exhibiting superior efficiency and lower unit impacts due to optimized energy and material flows.

Table 3: Scale Effect on Environmental Impacts in Biomass Processing

| Impact Category | Laboratory Scale | Industrial Scale | Reduction Achieved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity Consumption | Baseline | 98.8% less [24] | Near elimination through process optimization |

| Global Warming Potential | Baseline | 28% less [24] | Significant reduction through energy efficiency |

| Human Toxicity | Baseline | 97% less [24] | Dramatic reduction at commercial scale |

Industrial-scale transparent wood production consumes significantly less electricity (by 98.8%) and generates lower environmental impacts than laboratory-scale production (28% less global warming potential and approximately 97% less human toxicity) [24]. This scale effect underscores the importance of prospective LCA modeling that accounts for commercial-scale operations rather than relying solely on pilot-scale data.

Methodological Framework for Biomass LCA

Standardized LCA Workflow

A systematic, iterative approach to LCA ensures comprehensive coverage of all life cycle stages and robust accounting of temporal and technological uncertainties. The following workflow diagram outlines key phases in biomass LCA.

LCA Workflow for Biomass Energy Systems

Key Experimental Protocols

Prospective LCA with Iteration

Prospective LCA incorporates future technological developments and changing background systems (e.g., electricity grid decarbonization). The refined stepwise approach involves two LCA iterations to manage uncertainty and model future conditions effectively [8]:

First Iteration (Preliminary Prospective LCA): Conduct an initial assessment using current data to identify the most influential parameters through uncertainty and sensitivity analysis. This screening step reduces complexity by narrowing numerous uncertain parameters (e.g., from 25 to 4 in the lignin-based adhesive case study) to those with significant influence on results [8].

Second Iteration (Final Prospective LCA): Develop future scenarios based on the identified influential parameters. These scenarios model industrial-scale production (rather than pilot-scale) and incorporate expected changes in background systems, such as increased renewable energy share in electricity grids [8].

System Boundary Definition for Carbon Neutrality Assessment

Accurate carbon accounting for biomass energy requires careful system boundary definition to avoid misleading claims of carbon neutrality:

Temporal Boundaries: Account for the time lag between carbon release during combustion and re-sequestration during regrowth (carbon debt), which can span decades depending on biomass type and management practices [26].

Spatial Boundaries: Include direct and indirect land use changes (LUC/iLUC) that may occur locally or displaced to other regions when agricultural land is converted to energy crops [26].

Technical Boundaries: Incorporate emissions from all life cycle stages: cultivation (fertilizer production and application), harvesting (machinery), transportation (fuel), processing (drying, pelletizing), and combustion (conversion efficiency) [26].

Research Toolkit for Biomass LCA

Essential Analytical Tools and Databases

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Tools for Biomass LCA

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in Biomass LCA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Process Modeling Software | Aspen Plus [28] | Simulates mass and energy balances for biomass conversion processes under varying parameters. |

| LCA Database & Methodologies | Well-to-Tank (WTT), Well-to-Wheel (WTW) approaches [28] | Provides standardized frameworks for assessing transportation fuel pathways from feedstock production to end-use. |

| Multi-criteria Decision Tools | Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) [28] | Ranks alternative biomass process designs based on multiple environmental and energy criteria. |

| Delignification Chemicals | Sodium hydroxide, sodium sulfite, hydrogen peroxide (NaOH + Na₂SO₃ + H₂O₂) [24] | Removes lignin from wood with lower environmental impacts (GWP, acidification) than chlorine-based methods. |

| Polymer Infiltration Media | Epoxy, Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) [24] | Enhances transparent wood properties; epoxy shows lower environmental impacts than PMMA infiltration. |

Critical Parameters for Experimental Design

When designing biomass LCA studies, researchers should prioritize these highly influential parameters identified through sensitivity analysis:

- Total energy demand for manufacturing emerging wood-based products is the dominant parameter for climate change impacts [8].

- Renewable energy share in both foreground (manufacturing) and background (electricity grid) systems significantly influences GWP results [8].

- Allocation methods for partitioning environmental burdens between co-products (e.g., determining whether emissions are allocated to energy production or other wood products) dramatically affect land use impact results [8].

- Pyrolysis temperature and steam-to-carbon ratio are key optimizable parameters for thermochemical conversion processes, with optimal values shifting based on whether energy efficiency or environmental impacts are prioritized [28].

Comprehensive environmental assessment of biomass energy requires moving beyond a singular focus on carbon emissions to include multiple impact categories such as terrestrial acidification, human toxicity, particulate matter formation, and land use. The quantitative data presented in this guide demonstrates that the environmental profile of biomass energy systems varies significantly with technology choice, scale of operation, and specific process parameters. For researchers in wood-based electricity generation, employing rigorous, prospective LCA methodologies that account for future technological developments and changing background systems is essential for accurate sustainability assessment. The experimental protocols and research tools detailed here provide a foundation for designing studies that can effectively identify and promote truly sustainable biomass energy pathways with minimized trade-offs across multiple environmental dimensions.

Conducting an LCA for Woody Biomass Electricity: A Step-by-Step Methodology

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts of a product or system across its entire life cycle, from raw material acquisition to final disposal [13]. For researchers and scientists in bioenergy, conducting a rigorous LCA is crucial for quantifying the sustainability benefits of wood-based electricity generation and for providing a credible comparison against fossil-based and other renewable alternatives. The initial phase of any LCA—Goal and Scope Definition—sets the critical foundation for the entire study. This phase dictates the reliability and interpretability of the results by explicitly defining the assessment's purpose, the system under investigation, and the specific rules for its execution. Two of the most pivotal elements defined in this phase are the functional unit and the system boundary, which ensure that subsequent comparisons are equitable and scientifically sound.

Defining the Functional Unit

The functional unit provides a quantified reference to which all inputs and outputs of the system are normalized, enabling fair comparisons between different products or systems that fulfill the same function [30]. In the context of electricity generation, the primary function is to deliver electrical energy. Therefore, the most common and appropriate functional unit is a unit of electrical output.

Common Functional Units in Practice

Research and industry practices show a strong consensus on the functional units used for comparing electricity generation pathways. The table below summarizes the standard functional units and their applications.

Table 1: Common Functional Units in LCA Studies of Wood-Based Electricity Generation

| Functional Unit | Typical Application | Key Advantage | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity | Comparing different power generation technologies (e.g., biomass vs. coal vs. solar) [13] [30]. | Directly reflects the service provided (electricity), facilitating cross-technology comparison. | GWP values of -15 to 74.4 g CO₂eq/kWh for different woody biomass CHP scenarios [13]. |

| 1 Megajoule (MJ) of electricity | Detailed process analysis within a specific conversion technology [30]. | Useful for energy balance studies and analyses focused on the conversion efficiency stage. | Environmental impact comparison of generating 1 MJ of electricity from different pretreated wood pellets [30]. |

| 1 kilogram (kg) of fuel | "Cradle-to-gate" studies focusing on fuel production processes, such as pelletization [30]. | Isolates and highlights the environmental footprint of the fuel production stage itself. | Comparison of environmental impact per 1 kg of producing untreated, steam-exploded, and torrefied pellets [30]. |

For a thesis focusing on the comparative performance of wood-based electricity systems against other alternatives, using 1 kWh of electricity as the functional unit is the most appropriate and widely accepted choice.

Setting the System Boundary

The system boundary defines which unit processes (e.g., extraction, manufacturing, transportation, use, disposal) are included within the LCA. For wood-based electricity, defining this boundary involves deciding which stages of the biomass supply chain and energy conversion process are accounted for. The common approach is a "cradle-to-grave" analysis, though "cradle-to-gate" is also used for specific purposes.

Key Stages in the Wood-Based Electricity Life Cycle

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive, cradle-to-grave system boundary for a typical wood-based electricity generation system, highlighting the interconnected stages and key flows.

Comparative System Boundaries in Research

The scope of published studies varies, which can significantly influence the final results. The table below compares different system boundaries used in recent research on woody biomass energy.

Table 2: Comparison of System Boundaries in Woody Biomass LCA Studies

| Study Focus | Defined System Boundary | Included Stages | Excluded Stages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pellet Production [30] | Gate-to-Gate | Pellet production process (drying, grinding, pressing). | Feedstock production/collection, transportation of raw materials, final use of pellets. |

| Electricity from Pellets [30] | Gate-to-Gate | Electricity generation from received feedstock (pellets). | Feedstock production/collection, pellet manufacturing, transportation of pellets to plant. |

| Woody Biomass CHP [13] | Cradle-to-Grave | Forest residue collection, chipping, transport, CHP electricity generation, heat credit allocation. | End-of-life of infrastructure (e.g., power plant buildings). |

| Bioenergy Pathways [31] | Cradle-to-Grave (with Circular View) | Includes cascading use, recycling, and valorization of end-of-life biomass. | N/A |

A critical aspect of setting the system boundary, especially for Combined Heat and Power (CHP) plants, is allocation. Since CHP plants produce both electricity and useful heat, the environmental burdens must be allocated between these two co-products. The preferred method, as employed in modern studies, is system expansion, which avoids allocation by expanding the system to include the avoided impacts of producing the heat by conventional means [13] [30]. This approach gives a more accurate picture of the environmental performance of the electricity generation function.

Experimental Protocols for Key LCA Investigations

To ensure reproducibility and credibility, detailing the experimental or computational protocols is essential. Below are generalized methodologies for key experiments cited in the literature.

Protocol 1: Comparative LCA of Biomass Pretreatment Pathways

This protocol is based on studies that evaluate the environmental impact of different biomass pretreatment methods, such as torrefaction and steam explosion, prior to pelletization and combustion [30].

- Goal Definition: To compare the global warming potential (GWP) of electricity generated from wood sawdust pellets subjected to different pretreatment pathways.

- Scope Definition:

- Functional Unit: 1 Megajoule (MJ) of electricity delivered to the grid.

- System Boundary: Cradle-to-gate, encompassing biomass feedstock transport to the pellet mill, pellet production (including pretreatment), transport of pellets to the power plant, and electricity generation.

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI):

- Data Collection: Collect primary data on energy (electricity, natural gas) and material consumption for each pretreatment process (torrefaction at 230°C for 45 min; steam explosion at 180°C for 9 min). Collect data on biomass feedstock consumption, pellet yields, and the efficiency of electricity generation for each pellet type.

- Background Data: Use secondary LCI databases (e.g., Ecoinvent) for inputs like grid electricity, natural gas, and transportation.

- Impact Assessment: Calculate the GWP for each pathway using a recognized life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) method, such as the IPCC's characterization factors. The study noted that system expansion reduced environmental loads [30].

- Interpretation: Compare the GWP results across the different pretreatment pathways. The cited study concluded that torrefied pellets were more beneficial for climate change and resource depletion than steam-exploded pellets [30].

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of System Boundaries and Allocation in CHP

This protocol outlines the method for evaluating how system boundaries and co-product allocation choices influence the LCA results of a woody biomass CHP plant [13].

- Goal Definition: To quantify the difference in the calculated GWP of electricity from a woody biomass CHP plant when using a cradle-to-gate boundary versus a cradle-to-grave boundary with system expansion for heat allocation.

- Scope Definition:

- Functional Unit: 1 kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity.

- System Boundary Scenarios:

- Scenario A (Cradle-to-Gate): Includes only processes from biomass acquisition to the production of electricity at the plant boundary. Heat is considered a waste product.

- Scenario B (Cradle-to-Grave with System Expansion): Includes the same processes as Scenario A but expands the system to credit the avoided emissions from a conventional natural gas heating system that is displaced by the CHP's useful heat.

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI):

- Model the biomass supply chain (forest operations, chipping, transport).

- Model the CHP operation, recording inputs (biomass fuel) and outputs (electricity, heat).

- For Scenario B, model the natural gas system and quantity of heat that would have been required.

- Impact Assessment: Calculate the GWP (g CO₂eq/kWh) for both scenarios. The study highlighted that the inclusion of heat credits significantly improved the environmental performance of the systems [13].

- Interpretation: Analyze the percentage difference in GWP results between the two scenarios. This highlights the critical importance of transparently defining the system boundary and allocation method.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for LCA Studies

Conducting an LCA for wood-based electricity generation relies on a combination of physical research materials and sophisticated analytical tools. The following table details key resources essential for experimental and computational work in this field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Wood-Based Energy LCA

| Item / Solution | Function / Application in LCA Research |

|---|---|

| Woody Feedstocks (e.g., Forest Residues, Sawmill Sawdust) | Serves as the primary raw material for experimental pelletization, gasification, and combustion trials to generate primary data on conversion efficiency and emissions [13] [30]. |

| LCA Software (e.g., GREET, SimaPro, OpenLCA) | Provides the computational framework for modeling product systems, managing life cycle inventory data, and calculating environmental impact categories [13]. |

| LCI (Life Cycle Inventory) Databases (e.g., Ecoinvent) | Provides pre-compiled, background data on material and energy flows for common processes (e.g., grid electricity, diesel production, transportation) which are linked to the specific foreground data of the study [30]. |

| Standardized Impact Assessment Methods (e.g., IPCC 2021 GWP, ReCiPe) | A set of characterized factors that translate inventory data (e.g., kg of CH₄ emitted) into environmental impact scores (e.g., kg CO₂eq for Climate Change), allowing for standardized quantification and comparison [13] [30]. |

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) phase is a critical component of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) that involves the systematic collection and validation of data for all inputs and outputs associated with a product system throughout its life cycle. For biomass supply chains supporting electricity generation, this encompasses data collection from feedstock production through conversion to final power delivery. The quality and completeness of LCI data directly determine the reliability of sustainability assessments for biomass energy systems, enabling researchers to compare environmental performance across different technological pathways and feedstock alternatives [32]. As national energy strategies increasingly incorporate bioenergy to meet carbon neutrality targets, robust LCI methodologies provide the foundational data needed to avoid burden shifting across sustainability dimensions and support informed decision-making aligned with multiple Sustainable Development Goals [32].

Comparative Analysis of Biomass Feedstocks and Technologies

Quantitative Environmental Performance Indicators

Table 1: Comparative LCI Data for Selected Biomass Electricity Pathways

| Biomass Pathway | Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂ eq/MWh) | Feedstock Consumption | Key Emission Drivers | Technology Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-SNG (Base Case) | 41 [33] | Wood chips | Direct process emissions, electricity consumption [33] | Pilot to demonstration |

| Bio-SNG with Wind Power | 25 [33] | Wood chips | Wood chip preparation [33] | Early commercial |

| Natural Gas (Reference) | 16 [33] | Fossil methane | Supply chain methane leakage [33] | Mature |

| Grate Furnace System | Social impacts: 15-19% higher than fluidized-bed [32] | Forest biomass | Conversion efficiency [32] | Mature |

| Fluidized-Bed Furnace | Lower social risks across most categories [32] | Forest biomass | Conversion efficiency [32] | Commercial |

Table 2: Biomass Production and Conversion Data from Recent Market Reports

| Parameter | U.S. Production (July 2025) | U.S. Sales (July 2025) | U.S. Export (August 2025) | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Densified Biomass Fuel | 950,000 tons [34] | 970,000 tons [34] | 894,320.3 metric tons [34] | +15.3% from August 2024 [34] |

Interpretation of Comparative Results

The quantitative data reveals significant variations in environmental performance across different biomass pathways. The Bio-SNG scenario demonstrates that emissions drivers extend beyond direct combustion to include substantial contributions from wood chip preparation and electricity consumption for processing [33]. This highlights the importance of expanding LCI boundaries to encompass all upstream processes in biomass supply chains. The 15-19% higher social impacts associated with grate furnace technology compared to fluidized-bed systems [32] further illustrate how technological selection influences social sustainability dimensions, particularly in indicators such as gender wage gap and health expenditure.

The market data showing increased woody biomass consumption and rising exports [34] reflects growing international demand for biomass resources, which LCI practitioners must account for in modeling global supply chains. This trend underscores the need for region-specific data collection in LCI studies, as feedstock origin significantly influences environmental impact profiles [35].

Experimental Protocols for LCI Data Collection

Standardized LCI Data Collection Framework

LCI Data Collection Workflow

The experimental protocol for LCI data collection in biomass supply chains follows a systematic workflow encompassing eight critical stages from goal definition through final documentation. This structured approach ensures comprehensive coverage of all relevant inventory data while maintaining methodological consistency across studies.

Methodological Approaches for Specific Data Categories

Social LCI Methodology: The Social LCA framework adapted from UNEP guidelines involves four interrelated phases: (1) goal and scope definition with functional unit specification; (2) social life cycle inventory analysis using country- and sector-specific data; (3) social life cycle impact assessment evaluating potential social impacts; and (4) interpretation integrating social, environmental, and economic dimensions [32]. Working hours per functional unit serve as activity variables to measure social impact intensity, with particular attention to social indicators including child labor, forced labor, gender wage gap, women in the sectoral labor force, health expenditure, and contribution to economic development [32].

Uncertainty Analysis Protocol: Managing uncertainty in LCI follows a probabilistic approach incorporating: (1) evaluation of input quality using origin matrices; (2) assessment of result reliability; and (3) quantification of uncertainty using Monte Carlo methods [36]. This approach expresses results as environmental impact ranges rather than single values, with data quality indicators addressing parameter uncertainty, model uncertainty, and uncertainty due to choices [36] [37]. The Monte Carlo simulation is particularly valuable for propagating uncertainty through complex biomass supply chain models, though it requires substantial computational resources [36].

Advanced Methodological Considerations

Uncertainty Management in LCI Studies

Uncertainty in LCA arises from multiple sources including parameter uncertainty (database variability), model uncertainty (representativeness), statistical measurement error, uncertainty due to methodological choices, and uncertainty from changes in future physical systems [37]. For biomass supply chains, particular attention must be paid to temporal and spatial variability in feedstock characteristics, conversion technology performance, and supply chain logistics. Quantitative uncertainty analysis using Monte Carlo simulation provides a robust approach for characterizing these uncertainties, though semi-quantitative methods using data quality indicators offer practical alternatives when data limitations exist [36].

The management of uncertainty follows a structured procedure involving accuracy evaluation (similarity to real values) and precision assessment (result repeatability) [36]. For biomass systems, the uncertainty of biogenic carbon accounting presents special challenges, particularly when considering soil organic carbon sequestration and varying time horizons for global warming potential calculations [35].

Social Life Cycle Inventory Framework

Social LCI expands traditional environmental LCA to address socioeconomic dimensions of biomass supply chains. The methodology employs a multi-tier structure for supply chain definition that identifies representative countries of origin for all unit processes, enabling detection of social risks that might remain opaque in aggregated data [32]. This approach is particularly relevant for global biomass supply chains where feedstocks may originate from regions with different labor practices and social conditions.

Data collection for social LCI prioritizes country- and sector-specific statistics on social indicators, with normalization based on working hours per functional unit [32]. This facilitates comparison across different biomass systems and technologies while highlighting social hotspots in complex supply chains.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Methodological Tools for Biomass LCI Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Approach | Application in Biomass LCI | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Database Resources | USDA Foreign Agricultural Service wood pellet data | Tracking international biomass flows and market trends [34] | U.S. EIA Monthly Densified Biomass Fuels Report |

| Software Solutions | Monte Carlo simulation software | Quantifying uncertainty in LCI results [36] [37] | Various commercial and open-source LCA packages |

| Methodological Frameworks | UNEP S-LCA Guidelines | Assessing social impacts in biomass supply chains [32] | UNEP (2020) updated guidelines |

| Data Quality Assessment | Data Quality Indicators (DQI) | Semi-quantitative evaluation of input data reliability [36] | Multiple LCA methodology studies |

| Impact Assessment | IPCC 2021 methodology | Calculating global warming potential of biomass systems [33] | IPCC climate change reports |

Comprehensive Life Cycle Inventory data collection for biomass supply chains requires integration of multiple methodological approaches addressing environmental, social, and economic dimensions. The comparative analysis presented demonstrates significant variability in performance across different biomass pathways and technologies, emphasizing the importance of technology selection and system configuration in determining sustainability outcomes. Standardized experimental protocols for data collection, coupled with robust uncertainty analysis and social inventory methods, provide researchers with validated approaches for generating reliable LCI data. As biomass continues to play a pivotal role in decarbonization strategies, the continued refinement of LCI methodologies will remain essential for accurately quantifying the sustainability implications of bioenergy systems and supporting evidence-based policy and technology decisions.

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) - Applying Impact Categories to Biomass

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) represents a critical phase within the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) framework, where inventory data on material and energy flows are translated into potential environmental impacts. For biomass-to-energy systems, this translation provides crucial insights into their environmental performance compared to conventional fossil-based alternatives. The LCIA phase follows standardized principles outlined in ISO 14040 and ISO 14044, ensuring systematic and comparable assessments across different product systems [38]. When applied to wood-based electricity generation, LCIA helps researchers and policymakers identify environmental trade-offs and improvement opportunities across the entire value chain—from biomass cultivation or collection to final energy conversion and end-of-life management.

The fundamental purpose of LCIA in biomass systems is to quantify the magnitude of potential environmental consequences arising from the interconnected processes of feedstock production, transportation, conversion technologies, and waste management. This assessment moves beyond simple carbon accounting to encompass a multidimensional perspective that includes impacts on ecosystem health, resource availability, and human well-being. For emerging bioenergy technologies, conducting a thorough LCIA is particularly valuable during early development stages, as it identifies environmental hotspots before large-scale investments are made, enabling designers to prioritize interventions for maximum environmental benefit [8].

Methodological Framework for Biomass LCIA

Core LCIA Structure and Impact Categories

The LCIA process systematically converts Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) outputs—detailed records of all inputs, outputs, and emissions—into defined environmental impact category indicators. This structured approach consists of mandatory elements including selection of impact categories, classification (assigning LCI results to impact categories), and characterization (calculating category indicator results) [38]. For biomass systems, this translation is essential to understand how emissions like CO₂, CH₄, and NOx, along with resource consumption patterns, collectively contribute to broader environmental concerns such as climate change, acidification, and eutrophication.

Biomass LCIA typically evaluates multiple impact categories beyond global warming potential. Table 1 summarizes the key impact categories relevant to wood-based electricity generation systems, their indicators, and primary contributing flows from biomass operations.

Table 1: Key Impact Categories in Biomass LCIA

| Impact Category | Impact Indicator | Primary Contributing Flows from Biomass Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Global Warming | Global Warming Potential (GWP) in kg CO₂-eq | CO₂ (biogenic & fossil), CH₄, N₂O from combustion and decomposition [39] |

| Land Use | Land Use (area-time) | Land transformation for dedicated crops, forest management practices [39] |

| Acidification | Acidification Potential (AP) in kg SO₂-eq | SOₓ, NOₓ emissions from combustion processes [38] |

| Eutrophication | Eutrophication Potential (EP) in kg PO₄-eq | Nitrogen, phosphorus leaching from fertilizer use; nutrient runoff [38] |

| Photochemical Oxidant Formation | Photochemical Ozone Formation Potential (POFP) in kg NMVOC-eq | CO, NOₓ, volatile organic compounds from incomplete combustion [38] |

| Particulate Matter Formation | Particulate Matter Formation Potential (PMFP) in kg PM2.5-eq | Particulate emissions from harvesting, transport, and combustion [38] |

| Human Toxicity | Human Toxicity Potential (HTP) in kg 1,4-DCB-eq | Heavy metals, dioxins, furans from combustion and chemical applications [38] |

| Ecotoxicity | Ecotoxicity Potential (ETP) in kg 1,4-DCB-eq | Pesticides, herbicides, heavy metals affecting aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems [38] |

Special Considerations for Biomass Systems

Biomass systems present unique methodological considerations that significantly influence LCIA outcomes. The treatment of biogenic carbon is particularly crucial, as standards vary in their accounting approaches. Most standards follow the "-1/+1" method, where carbon absorption during biomass growth is recorded as a negative flow (removal from atmosphere), and carbon release during combustion or decomposition is recorded as a positive flow (addition to atmosphere) [40]. However, differences exist in how standards handle carbon storage duration and end-of-life scenarios, requiring careful alignment between the chosen methodology and study goals.

Allocation procedures present another critical consideration when a single process yields multiple products (e.g., sawmill producing lumber and sawdust for bioenergy). The ISO standard hierarchy recommends solving this multifunctionality first through subdivision, then system expansion, and finally allocation based on physical or economic relationships [38]. For instance, an LCA of pelletized biomass from sawmill residues might allocate environmental burdens between the primary lumber product and the energy-valued sawdust based on mass, energy content, or economic value [13] [41].

The system boundary definition dramatically affects results, with "cradle-to-grave" assessments providing the most comprehensive picture by including all stages from biomass extraction to end-of-life management of by-products [39] [42]. The increasing incorporation of spatiotemporal aspects further enhances assessment accuracy by reflecting local environmental conditions and temporal variations in operations and impacts [43].

Experimental Protocols and Data Collection for Biomass LCIA

Standardized LCA Protocol for Woody Biomass Electricity

Implementing a robust, reproducible LCIA for biomass energy systems requires adherence to a structured experimental protocol. The following workflow outlines the key phases from goal definition through interpretation, with special emphasis on impact assessment considerations specific to biomass systems.

Diagram 1: LCIA Workflow for Biomass Systems. The diagram illustrates the four interconnected phases of an LCA according to ISO 14040/44 standards, with the LCIA phase detailed to show its core elements.

The experimental protocol begins with goal and scope definition, where the functional unit—a quantifiable measure of system performance—is established. For wood-based electricity generation, common functional units include "1 kWh of electricity delivered to the grid" or "1 MJ of delivered energy" [38] [13]. This phase also determines system boundaries (e.g., cradle-to-gate or cradle-to-grave) and defines impact categories relevant to biomass systems.

The life cycle inventory phase involves collecting quantitative data on all energy and material inputs, as well as emission outputs, for each process within the system boundaries. For a woody biomass CHP plant, this includes data on biomass feedstock production (including fertilizers, fuels), transportation distances and modes, electricity and heat generation efficiency, and by-product management [13] [42]. Primary data from direct measurements is preferred, though background data from databases like Ecoinvent is often used for upstream processes [42].

During the LCIA phase, the inventory data is processed through the selected impact assessment method (e.g., CML, ReCiPe). This involves calculating characterization factors that translate diverse emissions into common equivalents for each impact category (e.g., converting CH₄ and N₂O to CO₂-equivalents for climate change) [38]. The interpretation phase then analyzes these results to identify significant issues, assess robustness through sensitivity and uncertainty analyses, and draw conclusions aligned with the study's goal [8].

Advanced Prospective and Iterative LCA Approaches

For emerging biomass technologies still at development stages, prospective LCA approaches offer valuable frameworks for anticipating environmental impacts under future scale-up conditions. This involves iterative assessment cycles, beginning with a preliminary LCA to identify influential parameters, followed by a final prospective LCA that incorporates future scenarios based on these parameters [8].

A key element in this approach is defining the Technology Readiness Level (TRL), which helps contextualize data quality and uncertainty. For lower TRL technologies, scenario development and sensitivity analysis become crucial to account for potential performance improvements and scale-up effects. As noted in a study of emerging wood-based technologies, "prospective LCIA results for climate change depend mostly on the energy demand for the manufacture of emerging hardwood-based products" [8].

Comparative LCIA Results Across Biomass Conversion Pathways

Quantitative Impact Assessment of Woody Biomass Systems

Direct comparison of LCIA results across different biomass feedstocks and conversion technologies reveals significant variations in environmental performance. The following table synthesizes Global Warming Potential (GWP) findings from multiple studies, highlighting how feedstock selection and process configurations influence climate impact outcomes.

Table 2: Comparative GWP of Biomass Electricity Generation Pathways

| Biomass Feedstock & Technology | System Description | GWP (g CO₂-eq/kWh) | Key Contributing Processes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest Residues (Wood Chips) CHP | Direct use of wood chips from forest residues in CHP with heat recovery | -78.63 | Biogenic carbon sequestration, avoided fossil fuel emissions | [13] |

| Sawmill Residues (Pellets) CHP | Pellets from sawmill residues dried with CHP recovered heat | -15 | Heat recovery during pelletization, transportation | [13] |

| Sawmill Residues (Pellets) CHP | Pellets from sawmill residues dried with natural gas | 74.4 | Natural gas for drying, pelletization energy | [13] |

| Wood Biomass Gasification | Gasification of waste wood biomass for electricity and heat | -16 to -32 | Waste biomass sourcing, carbon sequestration in biochar | [42] |

| Wood Biomass Gasification | Gasification of wood from dedicated crops | 18 - 42 (break-even at <600 km transport) | Fertilizer inputs, land use change, transportation distance | [42] |

| Pelletized Rubberwood Sawdust | Steam production from rubberwood sawdust pellets | 320 - 480* | Energy-intensive pellet production, combustion emissions | [41] |

| Pelletized Corn Cobs | Steam production from corn cob pellets | 210 - 370* | Simpler pellet production, agricultural residue utilization | [41] |

| Conventional Fossil Reference | Natural gas combined cycle | 400 - 500 | Fossil carbon emissions, extraction & processing | [13] |

Note: *Values estimated from steam production data and converted to approximate kWh equivalents for comparison.

The data reveals that systems utilizing waste or residue feedstocks (forest residues, sawmill residues) generally achieve superior GWP performance compared to those relying on dedicated energy crops. This advantage stems primarily from avoiding the burdens associated with dedicated cultivation, including fertilizer production, irrigation, and direct land use changes [13] [42]. The significantly negative GWP values observed in several biomass pathways highlight the potential for carbon-negative electricity generation when systems effectively sequester biogenic carbon—either in forest growth cycles or through stable biochar applications [13] [42].

Impact Category Profiles Beyond Climate Change

While GWP often receives primary attention, comprehensive environmental evaluation requires assessing multiple impact categories. The following diagram illustrates the relative impact profiles across different biomass electricity pathways, demonstrating the importance of multi-criteria assessment to identify potential trade-offs.

Diagram 2: Comparative Impact Profiles of Biomass Electricity Pathways. This diagram provides a qualitative comparison of environmental performance across multiple impact categories for three representative biomass systems, based on synthesis of cited LCA studies.

The comparative analysis reveals several important patterns. While forest residue systems generally perform well across most categories, they may still generate medium levels of acidification and particulate matter from combustion processes [13]. Systems using dedicated energy crops typically show higher impacts in land use and eutrophication categories due to agricultural inputs and potential fertilizer runoff [42]. Pelletization processes, particularly when using fossil fuels for drying, can contribute significantly to particulate matter formation and other air emissions, offsetting some advantages in climate impact [13] [41].

These findings underscore the importance of comprehensive impact assessment beyond single-metric evaluations, as optimization for climate benefits may inadvertently increase other environmental burdens. The integration of combined heat and power (CHP) configurations consistently demonstrates improved environmental performance across multiple impact categories by increasing overall system efficiency and providing heat credits that displace fossil fuel combustion [13].

Research Toolkit for Biomass LCIA

Implementing a robust LCIA for biomass energy systems requires specialized methodological resources and accounting tools. The following table outlines key components of the researcher's toolkit for conducting scientifically sound assessments.

Table 3: Research Toolkit for Biomass LCIA

| Toolkit Component | Function/Description | Application in Biomass LCIA |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software Platforms (SimaPro, openLCA) | Modeling and calculation environments for building product systems and impact assessment | Manages complex biomass supply chains; links inventory data with impact assessment methods [42] [41] |

| Life Cycle Inventory Databases (Ecoinvent, Agri-footprint) | Secondary data sources for background processes (energy, transport, materials) | Provides data for upstream processes (fertilizer production, machinery) and downstream emissions [42] [41] |

| LCIA Methods (CML, ReCiPe, TRACI) | Sets of characterization factors for converting emissions to impact scores | Standardizes impact calculations; enables comparison across studies [41] |

| Biogenic Carbon Accounting Tools | Specialized calculation modules for tracking biogenic carbon flows | Manages temporal aspects of carbon sequestration and release; applies standard-specific rules [40] |

| Allocation Procedures (System expansion, Physical, Economic) | Methods for partitioning environmental burdens between co-products | Resolves multifunctionality in integrated systems (e.g., sawmills producing lumber and residues) [13] [38] |

| Uncertainty & Sensitivity Analysis (Monte Carlo, scenario analysis) | Techniques for assessing robustness of results against data variability | Addresses uncertainties in biomass yield, conversion efficiency, and emission factors [8] [41] |

Critical Impact Assessment Considerations