Breaking the Barriers: A Technical Roadmap to Scalable Fourth-Generation Biodiesel Production

This article provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the primary challenges hindering the scale-up of fourth-generation biodiesel production, which utilizes genetically engineered microalgae and other microbial platforms.

Breaking the Barriers: A Technical Roadmap to Scalable Fourth-Generation Biodiesel Production

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive technical analysis of the primary challenges hindering the scale-up of fourth-generation biodiesel production, which utilizes genetically engineered microalgae and other microbial platforms. Targeting researchers and industry professionals, we explore the foundational science, current methodologies, and critical optimization strategies needed to overcome hurdles in strain engineering, cultivation, lipid extraction, and fuel conversion. We present comparative analyses of emerging technologies and validation frameworks, aiming to chart a path from lab-scale innovation to commercially viable biofuel production with implications for sustainable energy and biomedical applications.

From Feedstock to Fuel: Defining the Core Challenges in 4th Gen Biodiesel

Technical Support Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting

Q1: Our engineered Yarrowia lipolytica strain shows poor lipid titer despite high sugar consumption. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A: This is commonly due to metabolic flux imbalance. Key troubleshooting steps:

- Check Precursor Drain: Measure acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA levels. Drain towards TCA cycle or amino acid synthesis reduces lipid yield.

- Solution: Overexpress ATP-citrate lyase (ACL) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) to enhance precursor pool. Consider knocking down competing pathways (e.g., glycogen synthesis).

- Verify Regulation: Ensure lipid droplet proteins (e.g., LDP1) and DGAT enzymes are correctly expressed. Use proteomics to confirm.

Q2: Our non-canonical microbial host (e.g., Pseudomonas putida) exhibits cytotoxicity when engineered for high terpenoid-derived biodiesel precursor production. How can this be mitigated?

A: Cytotoxicity often stems from membrane disruption or redox imbalance.

- Immediate Action: Induce pathway expression only at high cell density and use a weaker promoter.

- Long-term Engineering: Implement a product export system (e.g., efflux pumps). Co-express stress-response genes (e.g., soxR, katG). Consider two-phase fermentation with an organic overlay for continuous extraction.

Q3: Electrofuel production via engineered Clostridium shows inconsistent yield between batch reactors. What critical parameters must be standardized?

A: Electrofuel production is highly sensitive to electrochemistry and electron flux.

- Key Parameters to Control:

- Cathode Potential: Must be precisely maintained (typically -0.4 to -0.6 V vs. SHE for C. ljungdahlii).

- Medium Conductivity: Keep consistent >20 mS/cm.

- Stirring Rate: Optimize for H₂ gas transfer if using indirect electron transfer.

- Protocol: Always pre-reduce medium with cysteine and use identical anode material (e.g., graphite felt) across experiments.

Q4: During continuous fermentation, our strain loses its engineered plasmid or production phenotype. How can strain stability be improved?

A: This indicates high metabolic burden or genetic instability.

- Strategies:

- Genomic Integration: Use CRISPR/Cas9 or transposons to integrate pathway genes into the chromosome with strong, constitutive promoters.

- Post-Segregational Kill Switches: Employ toxin-antitoxin systems on the plasmid for maintenance.

- Essential Gene Complementation: Place an essential gene (e.g., for amino acid synthesis) on the plasmid under selective pressure.

Experimental Protocol: CRISPRi-Mediated Dynamic Pathway Regulation inE. colifor Fatty Acid Optimization

Objective: To dynamically downregulate competing β-oxidation (fadD) during the lipid production phase using aCRISPR interference (CRISPRi).

Materials: See Research Reagent Solutions table.

Methodology:

- Strain Preparation: Transform production strain with plasmid pCRISPRi-fadD (dCas9 + sgRNA targeting fadD promoter).

- Fermentation: Inoculate M9 minimal medium + 2% glucose + appropriate antibiotics.

- Induction: At OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.6, add 100 µM IPTG to induce dCas9 expression and sgRNA transcription.

- Sampling & Analysis: Harvest cells at 2, 4, 6, 8, and 24h post-induction.

- qPCR: Measure fadD mRNA levels.

- GC-MS: Quantify extracellular fatty acids (C12-C18).

- Flow Cytometry: Monitor single-cell fluorescence if using a GFP-reporter for promoter knockdown efficiency.

- Control: Run parallel fermentation with a non-targeting sgRNA plasmid.

Table 1: Common Microbial Hosts & Performance Metrics (Theoretical vs. Recent Max)

| Host Organism | Primary Feedstock | Target Product | Max Theoretical Yield (g/g) | Recent Titer Reported (g/L) | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Glucose | Triacylglycerols (TAG) | 0.27 | >100 | Oxygen transfer, scale-up |

| Escherichia coli | Glucose | Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters (FAEE) | 0.28 | 1.5 | Cytotoxicity, low storage |

| Rhodococcus opacus | Lignocellulosic Sugars | TAG | 0.31 | 50 | Slow growth rate |

| Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | CO₂, Light | Free Fatty Acids (FFA) | N/A | 0.20 | Low productivity, light penetration |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Matrix: Low Product Yield

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Assay | Suggested Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| High substrate, low product | Metabolic bottleneck | Metabolomics (LC-MS) for intermediates | Overexpress rate-limiting enzyme; tune promoter strength. |

| Product degradation | Native host metabolism | RT-qPCR for degradation genes | Knock out β-oxidation or hydrolysis genes (e.g., fadD, tesB). |

| Growth inhibition | Precursor or product toxicity | Growth curve with/without induction | Implement dynamic control; engineer exporter proteins. |

| Genetic drift | Plasmid loss or mutation | Colony PCR; sequencing | Switch to genomic integration; use antibiotic selection. |

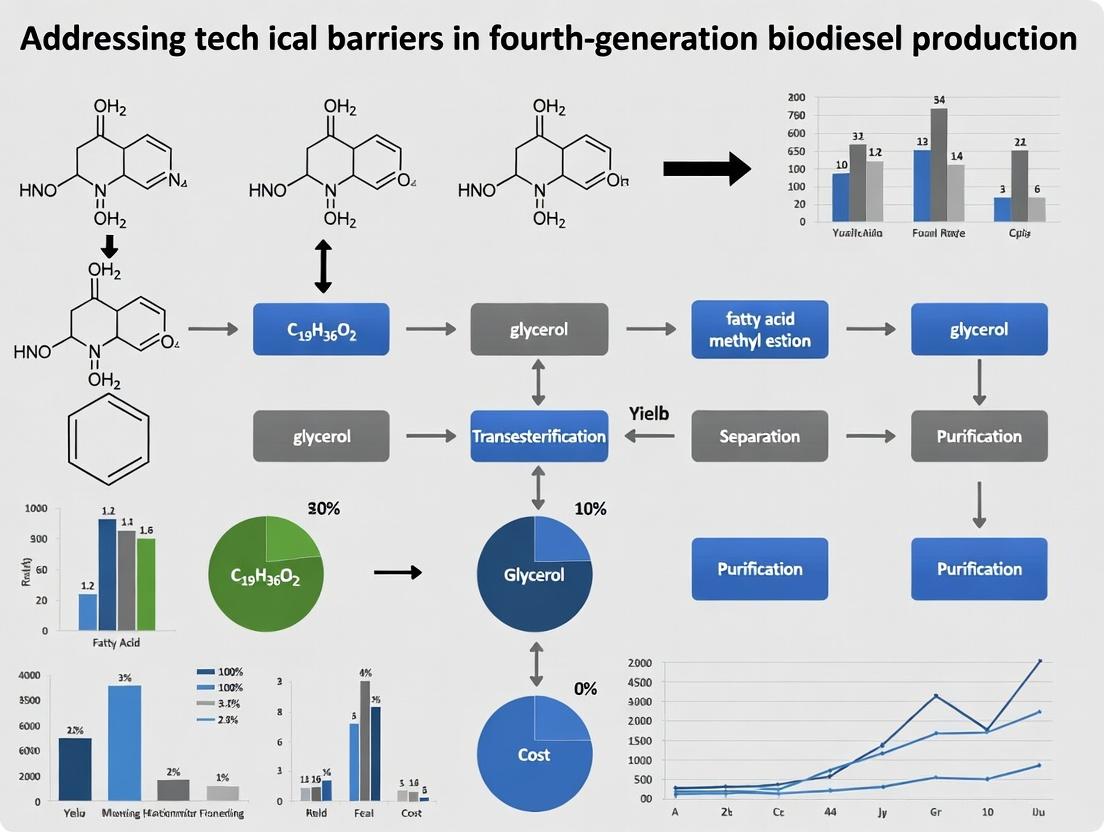

Diagrams

Title: Metabolic Flow & Bottlenecks in 4th Gen Biofuel Microbes

Title: Core R&D Workflow for Engineered Microbial Factories

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example/Catalog Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 Expression Plasmid | CRISPRi/a base tool for gene repression/activation. | pDawn, pCRISPRi series. Ensure host-compatible origin & resistance. |

| sgRNA Cloning Kit | For rapid construction of target-specific guide RNA vectors. | Addgene Kit #1000000059 or domestic assembly via BsaI sites. |

| GC-MS Standard Mix (C8-C30 FAMEs) | Quantification and identification of biodiesel-profile fatty acid esters. | Supelco 37 Component FAME Mix. Include internal standard (e.g., C17:0). |

| Acetyl-CoA Assay Kit | Fluorometric measurement of key metabolic precursor pool. | Abcam ab87546 or Sigma MAK039. Critical for flux analysis. |

| Cytometry Viability Stain | Distinguish live/dead cells during toxicity screening. | Propidium Iodide (PI) or SYTOX Green. Use with appropriate filter sets. |

| Electroporation Cuvettes (1mm) | Transformation of non-model microbial hosts (e.g., Rhodococcus). | Ensure sterile, pyrogen-free. Use optimized voltage (e.g., 1.8 kV for E. coli). |

| Anaerobic Chamber Gloves | Maintain strict anoxic conditions for electrofuel research. | Butyl rubber gloves (0.4mm thick). Regularly check for integrity/pinholes. |

| Luxury Bioreactor Control Software | For precise regulation of pH, DO, and feed during scale-up. | DASware, BioXpert, or LabVIEW custom scripts. Enable data logging. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our engineered microalgal strain shows a significant drop in lipid productivity after 15-20 sequential batch cultures. What are the likely causes and corrective actions?

A: This indicates a classic strain instability issue, common in engineered strains under continuous cultivation pressure.

- Primary Cause: Genetic reversion, plasmid loss, or metabolic burden leading to the selection of non-productive subpopulations.

- Corrective Actions:

- Implement Selective Pressure: Maintain antibiotic or auxotrophic selection in the media if the modification relies on episomal vectors.

- Genomic Integration: Transition key metabolic pathway genes (e.g., DGAT1, ACC) from plasmids to stable genomic loci via CRISPR-Cas9 or homologous recombination.

- Regular Re-isolation: Periodically re-isolate single cell clones and screen for high lipid producers to re-establish a clonal population.

- Monitor Genetic Drift: Use qPCR to regularly check copy numbers of introduced genes.

Q2: We observe lipid accumulation plateauing prematurely under nitrogen starvation. How can we push the theoretical yield closer to the strain's maximum?

A: This suggests a bottleneck in the lipogenesis pathway or co-factor limitation.

- Diagnostic Protocol: Perform a targeted metabolomics analysis at the mid-point of the accumulation phase. Key metabolites to quantify: Acetyl-CoA, Malonyl-CoA, NADPH, and intermediates in the TAG synthesis pathway.

- Solutions:

- Overexpress Malic Enzyme (ME): To enhance NADPH supply. Use a strong, inducible promoter (e.g., P_{NR}) to express ME concurrently with nitrogen depletion.

- Engineer a "Push-Pull" Pathway: Simultaneously overexpress Acetyl-CoA Carboxylase (ACC, "push") and Diacylglycerol Acyltransferase (DGAT2, "pull") to reduce intermediate feedback inhibition.

- Co-factor Supplementation: In bench-scale experiments, supplement minimal media with 0.5 mM NaHCO₃ to provide additional carbon for carboxylation reactions.

Q3: Our lab-scale photobioreactor (PBR) achieves 90% of theoretical lipid yield, but productivity drops by over 60% when scaling to a 500L pilot system. What are the key scaling parameters we failed to translate?

A: This is a scalability failure, typically due to light, nutrient, or gas transfer limitations.

- Key Scaling Parameters & Solutions:

| Parameter | Lab-Scale (10L) | Pilot-Scale (500L) | Issue & Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Path / Areal Density | < 10 cm light path, high surface-to-volume | > 30 cm light path, internal shading | Issue: Severe light attenuation. Solution: Implement internal light guides or a cascading PBR design with thinner channels. |

| Mixing / Shear Stress | Gentle magnetic stirring, low shear | Impeller-driven, high shear stress | Issue: Cell damage or stress response. Solution: Shift to airlift- or bubble column PBR design; optimize sparging rate (e.g., 0.2-0.5 vvm). |

| CO₂ Delivery & pH Control | Fine bubble diffuser, manual pH | Sparse pipe, localized acidification | Issue: Inefficient carbon delivery and pH gradients. Solution: Use inline static mixers post-CO₂ injection and implement multiple, distributed pH probes with feedback loops. |

| Nutrient Feeding | Batch or fed-batch | Attempted batch | Issue: Nutrient depletion/toxicity. Solution: Shift to continuous or semi-continuous cultivation with automated feedback from biomass sensors. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Genetic Stability of Engineered Strains Title: Serial Passage and Stability Quantification Assay

- Cultivation: Inoculate the engineered strain in selective medium. Grow to late exponential phase.

- Passaging: Dilute culture to a standardized OD₇₅₀ (e.g., 0.1) into fresh medium with and without selective agent. Repeat for 50+ generations.

- Sampling: Every 5 generations, harvest 1 mL of culture.

- Analysis:

- Plasmid Retention: Perform colony PCR on plated cells using primers for the engineered gene.

- Phenotypic Stability: Measure lipid content via Nile Red fluorescence or GC-FAME for sampled generations.

- Calculation: Determine the percentage of cells retaining the high-lipid phenotype over time.

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Lipid Productivity Screen Title: Microplate-Based Lipid Induction & Quantification

- Pre-culture: Grow strains in 96-deep-well plates in nutrient-replete medium for 48h.

- Induction: Centrifuge plates, resuspend biomass in nitrogen-depleted (-N) medium.

- Staining: At 0, 24, 48, 72h post-induction, add Nile Red dye (final conc. 1 µg/mL from a 1 mg/mL stock in DMSO) to wells.

- Incubation: Shake in dark for 15 min.

- Measurement: Use a plate reader with fluorescence detection (Ex/Em: 530/575 nm for neutral lipids). Normalize to biomass (OD₆₈₀).

- Calibration: Correlate fluorescence units to absolute lipid weight (mg/L) using a standard curve from a strain with known GC-FAME data.

Visualizations

Title: Strategies for Microbial Strain Stabilization

Title: Push-Pull Pathway Engineering for Lipid Yield

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in 4G Biofuel Research | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Nile Red Dye | Fluorescent stain for rapid, quantitative neutral lipid detection in live cells. Must be dissolved in DMSO for stock solution. | Sigma-Aldrich, 72485-1MG. Prepare 1 mg/mL stock in DMSO, store at -20°C. |

| Nitrogen-Depleted (-N) Medium | Standardized medium for inducing lipid accumulation (usually by omitting nitrate, e.g., NaNO₃). Essential for productivity assays. | BG-11₀ medium (BG-11 without sodium nitrate). Can be purchased as a custom mix from algal research suppliers (e.g., UTEX). |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System (Algal-optimized) | For stable genomic integration of pathway genes. Includes Cas9 enzyme and gRNA expression cassettes compatible with the host's codon bias. | Kit from companies like ToolGen or based on published vectors (e.g., pKSI-Cas9 for Chlamydomonas). |

| Inducible Promoter Plasmids | To control gene expression timing, reducing metabolic burden during growth. Common promoters are Nitrate Reductase (P_NR) or Copper Response (P_CA). | Available from algal molecular biology repositories (e.g., Chlamy Collection, Phytozome). |

| GC-FAME Standards | Quantitative calibration standards for Gas Chromatography analysis of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters. Required for absolute lipid quantification. | Supelco 37 Component FAME Mix (CRM47885). |

| Silicone Antifoam Emulsion | Critical for scaled-up bioreactor runs to prevent foam-over from high aeration and cell lysis products. | Sigma-Aldrich, Antifoam 204. Use at 0.01-0.1% (v/v). |

| Dissolved Oxygen & pH Probes | For real-time monitoring of culture health and scalability parameters (kLa, pH gradients). Requires in-line, autoclavable sensors. | Mettler Toledo InPro 6800 series (DO) and InPro 3250i (pH). |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: Our engineered Yarrowia lipolytica strain shows a severe growth defect after introducing the heterologous fatty acid synthase (FAS) pathway, despite successful plasmid integration confirmed by PCR. What are the primary causes and solutions?

- A: This is a classic metabolic burden issue. The overexpression of a resource-intensive pathway like FAS can drain cellular pools of acetyl-CoA, ATP, and NADPH, crippling central metabolism.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Analyze Precursor Drain: Measure intracellular acetyl-CoA and NADPH levels in the engineered strain vs. wild-type (see Protocol 1).

- Check Energy Status: Perform an ATP assay.

- Implement a Solution: Introduce a dynamic regulatory circuit. Replace the constitutive promoter driving the FAS genes with a fatty acid-responsive promoter (e.g., derived from FAS1 or PEX10). This decouples pathway expression from growth phase.

- Protocol 1: Measurement of Intracellular Acetyl-CoA and NADPH.

- Materials: Quenching solution (60% methanol, -40°C), Extraction buffer (100% methanol with 0.1 M formic acid), LC-MS system.

- Method:

- Culture cells to mid-log phase (OD600 ~10).

- Rapidly quench 1 mL culture in 4 mL of -40°C quenching solution. Centrifuge at 5000xg, -20°C.

- Extract metabolites from pellet with 1 mL ice-cold extraction buffer. Vortex, sonicate on ice for 10 min.

- Centrifuge at 15,000xg, 4°C for 10 min. Transfer supernatant for LC-MS analysis using a HILIC column.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Q2: Our oleaginous yeast produces the desired free fatty acids (FFAs) in small-scale fermentation but yield collapses when scaled to a 5L bioreactor using lignocellulosic hydrolysate. What parameters should we investigate?

- A: This points to feedstock-derived inhibitors and inadequate process control. Lignocellulosic hydrolysates contain fermentation inhibitors (furfurals, phenolics, organic acids) whose effects are magnified in high-density bioreactor cultures.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Profile the Feedstock: Quantify key inhibitors (5-HMF, furfural, acetic acid) in your hydrolysate batch using HPLC (see Protocol 2).

- Map Inhibition Kinetics: Perform a microtiter plate assay linking inhibitor concentration to growth lag time and FFA titer.

- Implement a Solution: (a) Pre-treat hydrolysate with activated charcoal or anionic exchange resins. (b) Engineer inhibitor tolerance by overexpressing aldose reductases (e.g., GRE3) and phenolic decarboxylases.

- Protocol 2: HPLC Analysis of Common Hydrolysate Inhibitors.

- Materials: Aminex HPX-87H column, 5 mM H2SO4 mobile phase, UV/RI detectors.

- Method:

- Filter hydrolysate through a 0.22 µm membrane.

- Set column temperature to 60°C, flow rate to 0.6 mL/min.

- Detect furfurals and phenolics at 280 nm, organic acids by RI.

- Quantify against standard curves for furfural, 5-HMF, acetic acid, vanillin.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Q3: We attempted to increase lipid titer by knocking out the beta-oxidation pathway (POX1-6 genes) in our engineered microbe, but observe an accumulation of toxic intermediates and no yield improvement. What went wrong?

- A: Complete blockage of beta-oxidation can lead to the accumulation of acyl-CoAs and reactive oxygen species (ROS), causing cytotoxicity. The strategy requires a more nuanced approach.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm Intermediate Accumulation: Analyze acyl-CoA profiles via LC-MS.

- Measure ROS: Use a cell-permeable fluorescent probe like H2DCFDA.

- Implement a Solution: Use a partial, titratable knockdown (e.g., with CRISPRi) rather than a complete knockout. Alternatively, couple the POX knockout with the overexpression of a trans-enoyl-CoA isomerase to shunt substrates back into lipid synthesis.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Q4: Our high-lipid-producing cyanobacterium strain is unstable, rapidly reverting to a low-yield phenotype after ~40 generations, even under selective pressure. How can we improve genetic stability?

- A: This indicates reliance on unstable plasmid-based expression or selection of compensatory mutations. Chromosomal integration and removal of unnecessary selection markers are key.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Determine Cause: Isolate revertants and sequence both the engineered pathway and global regulatory genes (e.g., sigE, ntcA in cyanobacteria).

- Implement a Solution: Use a dual strategy: (a) Integrate the entire pathway into a neutral genomic site (e.g., glgA locus) using CRISPR-Cas9. (b) Remove antibiotic resistance genes after integration via FLP/FRT recombination to reduce metabolic burden.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Table 1: Performance of Recent Engineered Microbial Platforms for Advanced Biofuels (2022-2024)

| Organism | Engineering Target | Feedstock | Max Titer (g/L) | Max Yield (g/g Substrate) | Key Challenge Addressed | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yarrowia lipolytica | Malonyl-CoA overproduction; FAS overexpression | Glucose | 102.5 (Lipids) | 0.22 | Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) bottleneck | Liu et al., 2023 |

| Rhodococcus opacus | CRISPRi knockdown of triacylglycerol lipase | Lignocellulosic sugars | 78.4 (TAG) | 0.19 | Lipid turnover during stationary phase | Park et al., 2022 |

| Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 | ΔglgA + alkane biosynthesis pathway (ols) | CO₂ | 1.2 (Alkanes) | Not Applicable | Carbon partitioning to biofuels | Wang et al., 2024 |

| E. coli | Re-routing carbon to malonyl-CoA via "push-pull" | Fatty Alcohols | 2.1 (Fatty Acids) | 0.28* | Redox cofactor imbalance | Zhang et al., 2023 |

*Yield calculated on a molar basis from fed fatty alcohol.

Table 2: Inhibitor Tolerance Levels in Engineered Oleaginous Yeasts

| Inhibitor Compound | Typical Conc. in Hydrolysate (g/L) | Wild-type Y. lipolytica IC50 (g/L) | Engineered Strain (Modification) | Improved IC50 (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetic Acid | 1.0 - 8.0 | 3.5 | ADH2 overexpression (acetaldehyde dehydrogenase) | 6.8 |

| Furfural | 0.5 - 3.0 | 1.2 | ALD6 overexpression (aldehyde dehydrogenase) | 2.5 |

| Vanillin | 0.1 - 1.5 | 0.8 | VRE1 overexpression (vanillyl alcohol oxidase) | 1.9 |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Dynamic Regulation Circuit for FAS

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Workflow for Scale-Up Failure

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas12a (Cpf1) System | Genome editing in GC-rich oleaginous yeasts (e.g., R. toruloides). Prefers T-rich PAM, simplifying multiplexed knockouts. | Higher fidelity than SpCas9 in some hosts, but requires optimization of guide RNA design. |

| HILIC-MS Columns (e.g., Acquity UPLC BEH Amide) | Separation and quantification of central metabolites (acyl-CoAs, NADPH, organic acids). Critical for metabolic flux analysis. | Requires specific mobile phases (high acetonitrile). Sensitive to column temperature. |

| Fatty Acid-Responsive Biosensor Plasmids (e.g., pFAS1-GFP) | Real-time, single-cell monitoring of fatty acid pool dynamics without cell lysis. Used for promoter characterization and high-throughput screening. | Response curve must be calibrated for each new host chassis. |

| Lignocellulosic Inhibitor Standard Kits | Pre-mixed analytical standards for furfural, 5-HMF, syringaldehyde, vanillic acid, etc. Essential for quantifying feedstock toxicity. | Standards are light-sensitive and require -20°C storage in the dark. |

| Metabolic Burden Assay Kit | Fluorometric measurement of translational capacity (e.g., via uncharged tRNA accumulation) and ATP levels to quantify stress from pathway expression. | Provides a more direct measure of burden than growth rate alone. |

Understanding Metabolic Pathways for Enhanced Lipid Biosynthesis

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues in Metabolic Engineering for Lipid Biosynthesis

Issue 1: Low Lipid Titer in Recombinant Microbial Strain

- Problem: Engineered Yarrowia lipolytica or Saccharomyces cerevisiae shows poor lipid accumulation despite genetic modifications.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause A: Precursor imbalance (Acetyl-CoA/NADPH limitation).

- Solution: Overexpress cytosolic acetyl-CoA pathways (e.g., ATP-citrate lyase, acetyl-CoA synthase) and NADPH-generating enzymes (e.g., glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, malic enzyme). Monitor cofactor ratios via metabolomics.

- Cause B: Feedback inhibition or competitive pathways.

- Solution: Knock out β-oxidation genes (e.g., POX1-6 in Y. lipolytica) and use lipid-tagging promoters (e.g., EXP1 promoter) to decouple growth and production phases.

- Cause C: Toxicity from lipid intermediates.

- Solution: Implement dynamic regulation to control flux and use two-phase bioreactor systems with in-situ extraction.

- Cause A: Precursor imbalance (Acetyl-CoA/NADPH limitation).

Issue 2: Inefficient Carbon Flux Toward Fatty Acid Synthesis

- Problem: Glucose is primarily directed toward cell growth/glycolysis, not lipogenesis.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Strong glycolytic flux outcompeting acetyl-CoA production for TCA cycle.

- Solution:

- Use CRISPRi to downregulate key glycolytic enzymes (e.g., Pfk, Pyk) during production phase.

- Introduce heterologous phosphoketolase (PHK) pathway to bypass glycolysis, directly converting G6P/X5P to Acetyl-P.

- Supplement culture with acetate or oleic acid as auxiliary carbon sources to bypass endogenous regulation.

Issue 3: Poor Genetic Tool Efficacy in Non-Model Oleaginous Hosts

- Problem: Low transformation efficiency, unstable expression, or poor CRISPR editing efficiency in non-model hosts like Rhodotorula toruloides.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause A: Restriction-Modification systems degrading foreign DNA.

- Solution: Co-express host-specific methyltransferases or use plasmid DNA isolated from a dam+/dcm+ E. coli strain.

- Cause B: Weak or incompatible promoters/terminators.

- Solution: Use native promoters/terminators (e.g., TEF1, GPD) identified via RNA-seq. Construct a library of synthetic hybrid promoters.

- Cause A: Restriction-Modification systems degrading foreign DNA.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most effective strategies to boost NADPH supply for fatty acid biosynthesis in yeast? A: The primary methods are: 1) Overexpressing the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) enzymes (G6PD, 6PGD). 2) Introducing the soluble transhydrogenase (UdhA) from E. coli to recycle NADH to NADPH. 3) Expressing a malic enzyme (ME) variant with high NADPH specificity. Recent data (2024) suggests a combined PPP + UdhA approach yields a ~40% increase in NADPH/NADP+ ratio and a corresponding 25% increase in lipid yield in S. cerevisiae.

Q2: How can I accurately measure the intracellular flux through the glyoxylate shunt versus the TCA cycle? A: Perform 13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA). Use [1-13C] or [U-13C] glucose as a tracer. Measure labeling patterns in proteinogenic amino acids via GC-MS. The key metabolites to track are succinate and malate labeling, which distinctly differ between the two pathways. A simplified protocol is provided in the Experimental Protocols section below.

Q3: Which inducible promoter system is recommended for controlling toxic gene expression in lipid-overproducing Yarrowia lipolytica? A: The E. coli-derived rhamnose-inducible (RhaR-P_{RHA}) system is highly effective due to its tight repression and low basal expression in lipid-producing conditions. Recent studies show >95% induction efficiency with 0.2% w/v rhamnose and negligible leakiness, making it superior to traditional oleic acid-responsive promoters in defined media.

Q4: What are common bottlenecks after overexpressing the core fatty acid synthase (FAS) complex? A: Post-FAS bottlenecks often include: 1) Acyl-CoA pool limitation – address by overexpressing acyl-CoA synthetases. 2) Acyltransferase capacity – overexpress DGAT1 and PDAT enzymes for triacylglycerol (TAG) assembly. 3) Lipid droplet (LD) surface area – co-express LD scaffolding proteins like perilipins to prevent cytosolic lipotoxicity. Data indicates DGAT overexpression is often the most critical single step.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Genetic Modifications on Lipid Yield in Yeast (2023-2024 Studies)

| Engineered Pathway/Module | Host Organism | Baseline Lipid Titer (g/L) | Final Lipid Titer (g/L) | % Increase | Key Enzymes Overexpressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-CoA & NADPH Supply | Y. lipolytica | 8.5 | 15.2 | 78.8% | ACL, ME, G6PD |

| TAG Assembly & Storage | S. cerevisiae | 1.8 | 4.1 | 127.8% | DGA1, LRO1, SEI1 |

| Phosphoketolase (PHK) Bypass | R. toruloides | 10.1 | 18.7 | 85.1% | Xpk, Pta |

| Dynamic Downregulation of β-oxidation | Y. lipolytica | 9.2 | 16.5 | 79.3% | CRISPRi targeting POX3, POX6 |

Table 2: Performance of Inducible Promoters for Metabolic Engineering

| Promoter System | Host | Inducer | Induction Ratio | Basal Leakiness | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pTEF1 (constitutive) | Y. lipolytica | N/A | N/A | High | Non-toxic, high-level expression |

| pEXP1 (oleic acid) | Y. lipolytica | Oleic Acid (0.1%) | ~120x | Low | Lipid production phase |

| pRHA (rhamnose) | Y. lipolytica | L-Rhamnose (0.2%) | ~200x | Very Low | Toxic gene expression |

| pCuRE (copper) | S. cerevisiae | CuSO4 (50 µM) | ~80x | Medium | Low-cost, scalable induction |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: 13C-MFA for Flux Determination in Oleaginous Yeast

- Culture & Labeling: Grow pre-culture in unlabeled YPD. Inoculate main culture in defined minimal medium with [U-13C] glucose (99% atom purity) as sole carbon source. Harvest cells at mid-lipogenic phase (OD600 ~25-30).

- Hydrolysis & Derivatization: Quench metabolism rapidly in -40°C methanol. Pellet cells, hydrolyze proteins in 6M HCl at 105°C for 24h. Derivatize released amino acids to N(tert-butyldimethylsilyl) derivatives using MTBSTFA.

- GC-MS Analysis: Analyze derivatives on GC-MS system. Use a DB-5MS column. Monitor mass isotopomer distributions (MIDs) of key fragments (e.g., alanine [m/z 260], valine [m/z 288]).

- Flux Calculation: Input MIDs into flux analysis software (e.g., INCA, OpenFlux). Constrain model with measured uptake/secretion rates. Use least-squares regression to estimate net fluxes through glyoxylate shunt, TCA, and PPP.

Protocol 2: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Multiplex Gene Knockout in R. toruloides

- gRNA Design & Expression Cassette Assembly: Design three 20-nt gRNAs targeting FAA1, FAA4, and POX1 using host-specific genomic data. Clone each into the pCRISPR-RT plasmid under individual tRNA-gRNA promoters.

- Donor DNA Preparation: Synthesize ~1kb homology arms flanking each target gene. Use these as templates for PCR to generate linear double-stranded donor DNA with stop codons and frame shifts.

- Transformation: Use electroporation (2.0 kV, 5 ms) to co-transform 5 µg of pCRISPR-RT and 1 µg of each donor DNA into competent R. toruloides cells.

- Screening: Plate on hygromycin-containing media. Screen colonies via diagnostic PCR and Sanger sequencing of the target loci.

Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Metabolic Pathway Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Function | Critical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1-13C] Glucose | Cambridge Isotope Labs, Sigma-Aldrich | Tracer for metabolic flux analysis (13C-MFA). | Quantifying flux through PPP vs. glycolysis in vivo. |

| Nile Red / BODIPY 493/503 | Thermo Fisher, Invitrogen | Fluorescent lipophilic dyes for lipid droplet staining. | Rapid, quantitative screening of lipid-accumulating clones via flow cytometry. |

| YPD / Yeast Nitrogen Base (YNB) | Difco, Formedium | Standard rich and defined media for yeast cultivation. | Maintaining and selecting transformed yeast strains. |

| MTBSTFA (Derivatization Reagent) | Regis Technologies, Sigma-Aldrich | Silylating agent for GC-MS sample preparation. | Derivatizing amino acids and organic acids for isotopomer analysis. |

| Hygromycin B / Nourseothricin | Corning, Jena Bioscience | Antibiotics for selection of resistant transformants. | Maintaining plasmid and selectable marker stability in engineered yeasts. |

| Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Thermo Fisher, NEB | High-fidelity PCR enzyme for genetic construct assembly. | Cloning large gene fragments and fusion constructs with minimal errors. |

| Cas9 Protein (Alt-R S.p.) | Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) | Purified Cas9 nuclease for in vitro RNP complex formation. | CRISPR-Cas9 editing in protoplasts of non-model yeast. |

The Economic and Energetic Bottlenecks of Current Photobioreactor Designs

To support research framed within the thesis of Addressing technical barriers in fourth-generation biodiesel production research, this technical center provides targeted troubleshooting for common PBR operational challenges.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: Our tubular PBR experiences rapid pH increase and dissolved oxygen (DO) accumulation beyond 400% saturation, followed by culture crash. What is the cause and solution? A: This indicates insufficient gas exchange (CO₂ delivery and O₂ stripping) due to low linear flow velocity (<0.3 m/s). High O₂ causes photoinhibition, while CO₂ depletion raises pH.

- Protocol for Diagnosis & Mitigation:

- Measure: Install in-line DO and pH probes at the reactor outlet.

- Calculate: Determine actual fluid velocity (V = flow rate / cross-sectional area).

- Act: Increase pumping rate to achieve V > 0.4 m/s. If using a degassing column, ensure its headspace is actively vented. Consider injecting pure CO₂ (at 1-5% v/v in air) on-demand via a feedback loop with pH setpoint (e.g., pH 8.0).

- Validate: Monitor culture stability over 24 hours post-adjustment.

Q2: We observe severe biofilm formation on internal glass/plexiglass surfaces, blocking light and contaminating cultures. How can we prevent this? A: Biofilms are a major source of contamination and reduced light penetration.

- Protocol for Cleaning & Prevention:

- Immediate Cleaning: Drain system and circulate 2% (v/v) phosphoric acid for 1 hour to dissolve mineral scales, followed by a 0.5% (w/v) sodium hypochlorite solution for 2 hours for biofilm sterilization. Rinse thoroughly with sterile water.

- Preventive Measure: Implement a "clean-in-place" (CIP) cycle every 10-14 days using 0.1% (v/v) hydrogen peroxide or 0.01% (w/v) peracetic acid. For ongoing prevention, ensure system has no dead zones by verifying flow uniformity (e.g., via tracer studies).

Q3: The energy input for mixing and cooling in our flat-panel PBR is unsustainable, contributing to a negative energy balance. How can we optimize? A: This is a core economic bottleneck. Focus on reducing mixing power and passive cooling.

- Protocol for Energy Audit and Reduction:

- Quantify: Measure power (kW) to air pumps/impellers and chiller. Calculate total kWh per cultivation day.

- Optimize Mixing: For airlift systems, reduce aeration rate to the minimum required for cell suspension (typically 0.1-0.3 vvm). Test by gradually lowering rate until settling is observed, then increase by 20%.

- Implement Passive Cooling: For outdoor panels, use a radiative cooling white paint on the rear surface and install a water-jacket with evaporative cooling (a thin water film dripping down the exterior). Monitor temperature stability during peak solar irradiance.

Q4: How do we accurately scale biomass productivity from lab-scale to pilot-scale PBRs? Our yields drop significantly. A: Scale-up failure often stems from light regime changes and nutrient gradient formation.

- Protocol for Predictive Scale-Up:

- Characterize Light Path: At lab scale, measure biomass density (g/L) vs. incident light (μmol/m²/s) to establish the light saturation parameter (Ik).

- Design Constraint: Ensure the optical path length (panel depth or tube diameter) at pilot scale does not exceed the depth where light attenuates to < Ik at your target biomass concentration. Use the Beer-Lambert law for estimation.

- Maintain Mixing: Scale mixing based on power input per unit volume (W/m³). Keep this constant between scales to minimize nutrient gradients.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Common PBR Design Bottlenecks & Mitigations

| PBR Type | Primary Economic Bottleneck | Primary Energetic Bottleneck | Typical Biomass Productivity (g/L/day) | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tubular (Horizontal) | High land area, cleaning/maintenance labor | Pumping power for mixing & cooling | 0.8 - 1.5 | Use larger diameter manifolds to reduce pressure drop; deploy on non-arable land. |

| Flat-Panel (Vertical) | Material cost (transparent facing), biofilm control | Temperature control (cooling fans/chillers) | 1.2 - 2.0 | Adopt durable, low-cost polymer films; implement passive evaporative cooling. |

| Airlift/Bubble Column | Gas compression and sterilization cost | Aeration/compression energy | 0.5 - 1.2 | Optimize sparger design for smaller bubbles; utilize waste CO₂ streams from industry. |

| Thin-Layer Cascade | Water loss due to evaporation, precise engineering | Pumping for recirculation | 1.5 - 3.0 | Install condensing covers; use gravity-fed designs where terrain allows. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining the Critical Light Path for Scale-Up Objective: To determine the maximum allowable culture depth/diameter to prevent light limitation at scale. Materials: Lab-scale PBR (1-5L), spectrophotometer, bench-top centrifuge, PAR (Photosynthetically Active Radiation) sensor. Method:

- Grow target strain (e.g., Nannochloropsis sp.) to mid-exponential phase.

- Take a culture sample. Measure optical density at 750 nm (OD₇₅₀) and dry cell weight (DCW) via filtration and drying (105°C, 24h) to establish an OD-DCW standard curve.

- Dilute culture to a series of biomass concentrations (e.g., 0.2, 0.5, 1.0 g/L).

- Fill thin, rectangular cuvettes with these dilutions. Measure PAR intensity incident on the front surface (I₀) and transmitted through the sample (I).

- Calculate the light extinction coefficient (ε) using Beer-Lambert's Law: I = I₀ * e^(-ε * X * L), where X is biomass conc. (g/L) and L is path length (m).

- Calculation: For your target operational biomass (Xop), calculate the path length where light attenuates to the saturation intensity (Iₖ, species-specific, ~100-200 μmol/m²/s): Lcritical = -ln(Iₖ / I₀) / (ε * X_op).

Protocol: Systematic Cleaning-in-Place (CIP) for Biofilm Prevention Objective: To sterilize PBR and associated tubing without disassembly. Materials: Peristaltic pump, CIP reservoir, 0.5% (w/v) NaClO solution, 2% (v/v) food-grade phosphoric acid, neutralization tank. Method:

- Drain culture harvest completely.

- Rinse system with tap water for 5 minutes to remove debris.

- Circulate 2% phosphoric acid solution for 60 minutes at room temperature.

- Drain acid and rinse with water until effluent pH is neutral.

- Circulate 0.5% NaClO solution for 120 minutes.

- Drain bleach and rinse thoroughly with sterile water or culture medium until no chlorine odor is detected (test with potassium iodide strips).

- The system is now ready for inoculation.

Visualizations

PBR Troubleshooting Decision Pathway

Light Attenuation Defines PBR Scale-Up Limit

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Inline DO/pH Sensor (e.g., Hamilton, Mettler Toledo) | Provides real-time, sterile monitoring of two most critical parameters for culture health and gas exchange efficiency. |

| PAR Sensor & Datalogger (e.g., LI-COR Quantum Sensor) | Essential for quantifying the light environment (I₀) and establishing light response curves for strain selection and PBR design. |

| Peracetic Acid (PAA) 1-5% Solution | A highly effective, fast-acting sterilant for CIP that decomposes into harmless acetic acid and oxygen, reducing rinse water needs. |

| Silicone-based Antifoam (Food Grade) | Critical for controlling foam in high-aeration systems to prevent biomass loss and contamination via exhaust lines. |

| Trace Metal Chelator (e.g., EDTA, Citric Acid) | Prevents precipitation of essential micronutrients (Fe, Cu) in alkaline medium typical of high-CO₂ absorption cultures. |

| Polymer Film (e.g., ETFE, FEP) | Durable, low-cost, high-light-transmittance alternative to glass or plexiglass for panel/tube construction, reducing capital expense. |

| Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) | Automates control of pumps, valves, and lights based on sensor data (pH, T, DO), ensuring reproducibility and reducing labor. |

Engineering Solutions: Advanced Methodologies for Enhanced Production

CRISPR-Cas and Synthetic Biology Tools for Precise Metabolic Engineering

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting and FAQs

FAQ Section: Common Conceptual and Application Issues

Q1: When using CRISPR-Cas9 to knockout an acetyl-CoA competing pathway gene in Yarrowia lipolytica for lipid overproduction, I observe very low editing efficiency. What could be the cause? A: Low editing efficiency in oleaginous yeasts is frequently due to suboptimal gRNA design or poor Cas9 expression. First, verify your gRNA sequence for specificity and minimal off-target potential using current tools like CHOPCHOP or Benchling. Second, ensure your Cas9 is codon-optimized for your host organism. Third, consider the delivery method; for Y. lipolytica, lithium acetate transformation followed by homologous recombination is standard, but efficiency varies with strain and growth phase. Use a high-fidelity polymerase for repair template amplification to prevent unwanted mutations. Finally, include a positive control (e.g., a gRNA targeting a known essential gene with a non-lethal phenotype) to validate your system.

Q2: My CRISPRi system for downregulating a key enzyme in the β-oxidation pathway is showing inconsistent repression across my microbial culture. How can I improve uniformity? A: Inconsistent repression often stems from plasmid loss or variable dCas9 expression. Ensure your system is under tight, inducible control (e.g., using a tetracycline-inducible promoter) and include a selective antibiotic throughout the culturing period. For more stable repression, consider integrating the dCas9 and gRNA expression cassettes into the host genome. Also, verify the gRNA target site is within the early region of the gene's coding sequence for optimal steric hindrance. Monitor culture fluorescence if using a reporter, and sort for uniform population via FACS if necessary.

Q3: I am designing a synthetic pathway for fatty acid-derived biofuel (e.g., fatty ethyl esters) in E. coli. Metabolic flux analysis indicates a bottleneck at the fatty acyl-ACP step. Which synthetic biology tool is best to address this? A: To address a precise metabolic bottleneck, consider employing CRISPR-mediated transcriptional activation (CRISPRa) to upregulate the downstream enzyme (e.g., acyl-ACP thioesterase) or a tunable intergenic region (TIGR) library to optimize ribosomal binding sites and expression levels of multiple operon genes simultaneously. Alternatively, MAGE (Multiplex Automated Genome Engineering) can be used to create a library of promoter variants for the rate-limiting gene to screen for optimal flux. The choice depends on whether you need targeted upregulation (CRISPRa) or high-throughput screening of regulatory parts (TIGR or MAGE).

Q4: During the purification of microbially synthesized biodiesel precursors, I encounter high cellular toxicity of the intermediates. What genetic safeguards can be implemented? A: Implement a biosensor-responsive containment strategy. Design a circuit where a toxic intermediate activates a biosensor (e.g., a transcription factor) that subsequently induces the expression of (a) an efflux pump to export the compound, or (b) a dedicated detoxification enzyme. Alternatively, use dynamic pathway regulation: employ a CRISPRi system where the gRNA expression is controlled by a metabolite-responsive promoter, automatically downregulating the pathway once a toxic threshold is reached, balancing production and cell viability.

Troubleshooting Guide: Step-by-Step Experimental Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution | Verification Step |

|---|---|---|---|

| No colony growth after transformation with CRISPR plasmid. | 1. Cas9 toxicity.2. Ineffective double-strand break repair (no template).3. Antibiotic concentration too high. | 1. Use an inducible promoter for Cas9.2. Co-transform with a linear repair template with >50 bp homology arms.3. Titrate antibiotic to find minimum inhibitory concentration. | Plate on inducing vs. non-inducing media. Check for template presence via PCR on transformation mix. |

| High rate of undesired mutations (off-target effects). | gRNA with low specificity. | Re-design gRNA using updated algorithms. Use a high-fidelity Cas9 variant (e.g., SpCas9-HF1). Deliver as a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex for shorter activity window. | Perform whole-genome sequencing on 2-3 edited clones. |

| Poor performance of synthetic pathway after genome integration. | 1. Chromosomal position effect.2. Insufficient metabolic precursors. | 1. Target integration to a genomic "hotspot" known for stable expression (e.g., phiC31 or Bxb1 attB sites).2. Use CRISPRa to upregulate precursor-supplying pathways (e.g., Malonyl-CoA pathway). | qPCR to measure integrated gene copy number and expression. LC-MS to measure precursor pool sizes. |

| Biosensor for fatty acyl-CoAs shows low dynamic range. | Poor promoter sensitivity or high background. | Screen a mutant promoter library for the biosensor's transcription factor. Optimize the binding site copy number upstream of the reporter gene. | Calibrate with pure acyl-CoA standards. Flow cytometry to measure population distribution. |

Table 1: Comparison of Common CRISPR-Cas Systems for Metabolic Engineering

| System | Editing Type | Typical Efficiency in Yeast/Bacteria | Key Advantage | Primary Use in 4G Biodiesel |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 (Streptococcus pyogenes) | Knockout, Knock-in | 70-95% / 80-99% | High efficiency, well-characterized | Disrupting competing pathways (e.g., polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis). |

| CRISPR-dCas9 (i/a) | Transcriptional Inhibition/Activation | 50-80% repression / 10-50x activation | Tunable, reversible | Fine-tuning expression of fatty acid synthase complex. |

| CRISPR-Cas12a (Cpfl) | Multiplex editing | 40-70% / 60-90% | Simpler gRNA, creates sticky ends | Simultaneous knockout of multiple β-oxidation genes. |

| Base Editors (BE) | Point Mutation (C>T, A>G) | 10-50% / up to 100% | No double-strand break, no donor template | Precustation of enzyme active sites (e.g., thioesterase substrate specificity). |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Engineered Strains for Biodiesel Precursors

| Host Organism | Engineering Strategy | Key Product | Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g substrate) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yarrowia lipolytica | CRISPR-Cas9 KO of POX1-6, Multisite integration of DGA1 | Triacylglycerols (TAG) | ~120 | 0.22 | 2023 |

| Escherichia coli | CRISPR-MAGE to optimize T7 promoters, FadR deletion | Free Fatty Acids (FFA) | 15.5 | 0.21 | 2024 |

| Synechocystis sp. | CRISPRi repression of glycogen synthase, tesA overexpression | Fatty Acids | 1.2 (per g DW) | N/A (photoautotrophic) | 2023 |

| Aspergillus niger | CRISPR-Cas9 mediated mlcR overexpression | Malonyl-CoA | N/A | Pool increased by 8-fold | 2024 |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout in Yarrowia lipolytica for Lipid Accumulation Objective: Disrupt the GUT2 gene (glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) to redirect carbon flux towards lipid synthesis.

Materials:

- Y. lipolytica PO1f strain.

- pCRISPRyl plasmid (or similar Cas9/gRNA expression vector for Y. lipolytica).

- gRNA design: Oligonucleotides targeting GUT2.

- Repair Template: Double-stranded DNA fragment with 5' and 3' homology arms (80-100 bp) surrounding the GUT2 ORF.

- YPD media, Lithium Acetate transformation reagents, SD-URA plates.

Method:

- gRNA Cloning: Anneal and phosphorylate oligonucleotides. Ligate into the BsmBI-digested pCRISPRyl vector. Transform into E. coli, isolate, and sequence-verify plasmid.

- Strain Transformation: Grow Y. lipolytica to mid-log phase. Prepare competent cells using lithium acetate/PEG method. Co-transform 100 ng of the pCRISPRyl-GUT2_gRNA plasmid with 500 ng of the GUT2 repair template (which contains a stop codon insertion). Include a no-template control.

- Selection and Screening: Plate on SD-URA to select for plasmid retention. Incubate at 28°C for 3 days.

- Colony PCR: Screen 10-20 colonies via PCR using primers flanking the GUT2 target site. Compare amplicon size to wild-type.

- Curing the Plasmid: Grow positive clones in YPD without selection for 2-3 generations. Plate for single colonies on YPD, then replica-plate to SD-URA and YPD to identify uracil-prototrophs (plasmid-cured).

- Phenotypic Validation: Grow edited and WT strains in lipid-accumulation media (e.g., nitrogen-limited). Stain with Nile Red and quantify fluorescence or perform GC-MS analysis of lipids.

Protocol 2: Implementing a CRISPRi Fatty Acid Biosensor in E. coli Objective: Construct a feedback circuit where acyl-ACP levels repress fabI expression to reduce saturation.

Materials:

- E. coli MG1655.

- Plasmid with dCas9 (e.g., pdx-dCas9).

- gRNA expression plasmid with a metabolite-responsive promoter (e.g., PfabH).

- Fluorescent reporter plasmid with fabI promoter driving GFP.

Method:

- Circuit Assembly: Clone a gRNA sequence targeting the fabI RBS into a vector downstream of the PfabH promoter (activated by acyl-ACP). Transform the dCas9 plasmid, the biosensor-gRNA plasmid, and the PfabI-GFP reporter plasmid sequentially into E. coli.

- Calibration: Grow the strain in M9 minimal media supplemented with varying concentrations of exogenous fatty acids (e.g., oleic acid). Measure GFP fluorescence (reporter) and mCherry (if from dCas9 plasmid) via plate reader over 24h.

- Dynamic Response Test: Shift cultures from low to high fatty acid conditions. Take time-point samples for flow cytometry to assess single-cell fluorescence distribution and response time.

- Functional Validation: Measure fatty acid composition of strains with active vs. inactive (control gRNA) circuit using GC-FAME after growth in defined conditions.

Visualizations

(Diagram Title: CRISPR Metabolic Engineering Workflow)

(Diagram Title: Metabolic Pathway with Intervention Points)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Function in CRISPR/SynBio for Biodiesel |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Cas9 Nuclease (e.g., SpyFi) | Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), NEB | Reduces off-target effects during knockouts, critical for maintaining genome integrity in production strains. |

| dCas9-VPR Transcriptional Activator Plasmid | Addgene (various), ATCC | Enables CRISPRa for upregulating rate-limiting genes (e.g., acetyl-CoA carboxylase) without gene insertion. |

| Cytidine Base Editor (BE4max) System | Addgene (#112093), BEAT Bio | Allows precise C-to-T conversion to create stop codons in competitor genes or tune enzyme kinetics. |

| Nile Red Fluorescent Dye | Sigma-Aldrich, Thermo Fisher | Rapid, quantitative staining of intracellular lipid droplets for high-throughput screening of engineered strains. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | NEB, Thermo Fisher | Enables seamless, one-pot assembly of multiple DNA fragments (e.g., pathway operons) into a vector. |

| Lipidomic Standard Mix (e.g., FAME Mix C4-C24) | Sigma-Aldrich, Larodan | Essential internal standards for GC-MS quantification of fatty acid and biodiesel precursor profiles. |

| RNP Complex (Custom gRNA + Cas9) | Synthego, IDT | For transient, high-efficiency editing in hard-to-transform hosts, minimizing plasmid toxicity. |

| Bxb1 Integrase Kit | Lucigen, Takara | Enables stable, single-copy integration of large biosynthetic pathways into specific genomic "landing pads". |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue Category 1: Photobioreactor (PBR) Performance Decline

Q1: I am observing a sudden drop in biomass productivity in my tubular PBR. The culture appears less dense. What could be the cause and how can I resolve it?

A: A sudden drop in productivity often stems from light limitation, CO₂ starvation, or biofilm formation.

- Check Light Penetration: Measure PAR (Photosynthetically Active Radiation) at various depths. If light attenuation is >70% at the core, consider diluting the culture to an OD750 of 0.8-1.2.

- Inspect CO₂ Delivery: Verify the sparger integrity and CO₂ concentration in the inlet gas (should be 1-5% v/v). Calibrate your in-line pH sensor; a rising pH (>8.5) indicates CO₂ deficiency.

- Examine for Biofilms: Inspect tube interiors and baffles for slime formation. Implement a scheduled cleaning protocol with 1M NaOH, followed by thorough rinsing with sterile water.

Q2: My flat-panel PBR is experiencing overheating (>35°C) despite active cooling, leading to culture bleaching. What steps should I take?

A: Overheating is critical. Execute the following immediately:

- Emergency Protocol: Increase cooling water flow rate and reduce incident light intensity by 50% using neutral density filters or dimmers.

- Long-term Solution: Integrate a temperature-interlocked light control system. Consider using heat exchangers with higher BTU capacity. Data from recent studies (2023) shows that a temperature differential (Tculture - Tcoolant) of >10°C requires system recalibration.

Table 1: PBR Critical Parameter Thresholds

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Critical Threshold (Action Required) | Typical Sensor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 20-28°C | >35°C or <15°C | PT-100 Probe |

| pH | 7.0-8.2 | >8.5 or <6.8 | Electrochemical pH Sensor |

| Dissolved O₂ | 80-120% air saturation | >150% (Risk of photoxidation) | Optical DO Probe |

| PAR at Culture Surface | 200-500 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ | <100 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ | Quantum Sensor |

Issue Category 2: Heterotrophic Fermentation Contamination & Yield

Q3: My heterotrophic fermentation for lipid accumulation is consistently contaminated with yeast after 48 hours, despite an initial sterile inoculum. Where is the likely breach?

A: Late-stage contamination typically points to gas exchange or sampling ports.

- Protocol for Sterility Check: Replace all inlet air filters (0.2 µm hydrophobic PTFE). Pressure-test the vessel at 0.5 bar for 20 minutes. Seal all sampling ports with silicone sleeves and sterilize with 70% ethanol before each needle puncture.

- Medium Revision: Lower the initial pH of your medium to 5.5 for the first 24 hours to inhibit yeast, then adjust to optimal range (7.0) for bacterial/algal growth.

Q4: I am not achieving the reported high lipid titers (>10 g/L) during nitrogen-starvation phase in fermenters. What are the key controlling factors?

A: Lipid overproduction is tightly linked to nutrient stress and C/N ratio.

- Detailed Protocol - Nitrogen Starvation Induction:

- Grow culture to late-exponential phase in complete medium (e.g., BG-11 with glucose).

- Harvest cells via aseptic centrifugation (4000 x g, 10 min).

- Resuspend in medium with 10x the carbon source (e.g., 50 g/L glucose) but zero nitrogen (omit NaNO₃ or NH₄Cl).

- Maintain dissolved oxygen above 30% saturation via aggressive stirring (300-500 rpm) and aeration.

- Monitor lipid accumulation over 72-96h using Nile Red fluorescence or GC-MS.

Table 2: Heterotrophic Fermentation Optimization Parameters

| Factor | Target for High Lipid Yield | Common Pitfall |

|---|---|---|

| C/N Ratio | 40-60:1 (mol/mol) | Inconsistent carbon source feed |

| Dissolved O₂ | 30-50% air saturation | Oxygen limitation during stress phase |

| Induction Point | Late-exponential phase (OD ~12-15) | Induction during lag or early phase |

| Micronutrients | Adequate Fe³⁺, Mg²⁺, PO₄³⁻ | Precipitation of Fe in phosphate-rich media |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q5: What is the most effective sterilizing agent for PBR silicone tubing without causing degradation? A: Peracetic acid (0.1-0.2%) is highly effective for in-place sterilization of sensitive tubing. Follow with sterile water flush. Avoid prolonged exposure to chlorine-based agents which accelerate silicone cracking.

Q6: How do I scale lipid productivity from a 5L lab-scale fermenter to a 500L pilot system? A: Focus on maintaining constant kLa (volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient) and P/V (power per volume). Perform scale-up calculations based on these parameters, not just geometric similarity. Expect a 10-20% drop in titer during initial pilot runs.

Q7: Can I use waste carbon sources (e.g., glycerol, acetate) directly in heterotrophic fermentation? A: Yes, but pre-treatment is mandatory. Protocol: Filter through 0.2 µm, adjust to non-inhibitory concentrations (<50 g/L for crude glycerol), and supplement with a defined nitrogen source. Performance varies by strain; conduct a Design of Experiment (DoE) to optimize.

Q8: My PBR data shows diurnal pH swings. Is this normal? A: Yes, it indicates active photosynthesis (CO₂ consumption raises pH) and respiration (CO₂ production lowers pH). Automated control via pulsed CO₂ injection is recommended to keep pH within ±0.3 of setpoint.

Experimental Protocol: Comparative Lipid Yield in PBR vs. Fermentation

Objective: To quantify and compare lipid content and productivity of Chlorella vulgaris between autotrophic (PBR) and heterotrophic (Fermenter) cultivation under nitrogen-starvation.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below. Method:

- Inoculum Prep: Grow axenic C. vulgaris in 500 mL TAP medium for 72h.

- Photobioreactor Arm:

- Inoculate 10L tubular PBR (OD750 0.1) with N-replete medium.

- Maintain: 25°C, 150 µmol m⁻² s⁻¹ continuous light, 1% CO₂, pH 7.5.

- At OD750 2.0, switch to N-deplete medium. Continue for 96h.

- Sample daily for biomass (dry cell weight) and lipid analysis (Nile Red/GC-MS).

- Fermentation Arm:

- Inoculate 5L bioreactor with 3L TAP + 20 g/L glucose.

- Maintain: 25°C, 400 rpm, 1 vvm air, pH 6.8 (controlled with NH₄OH).

- At OD750 12-15, cease NH₄OH and add 50 g/L glucose bolus for N-starvation.

- Maintain DO >30% for 96h. Sample as in Step 2.

- Analysis: Calculate lipid productivity as (Lipid concentration (g/L) / time (days)).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Product/Catalog # |

|---|---|---|

| Nile Red Stain | Fluorescent dye for neutral lipid quantification in vivo. | Sigma-Aldrich, N3013 |

| BG-11 & TAP Media Kits | Defined culture media for cyanobacteria/microalgae. | UTEX Culture Media Kits |

| Hydrophobic PTFE Filter (0.2 µm) | Sterile venting and gas delivery for fermenters. | Millipore, SLFG05010 |

| Dissolved Oxygen Probe | Real-time monitoring of % air saturation in broth. | Mettler Toledo, InPro6800 |

| PAR (Quantum) Sensor | Measures photosynthetically active radiation in PBRs. | LI-COR, LI-190R |

| Peracetic Acid Solution | Effective, low-residue sterilant for sensitive components. | Sigma-Aldrich, 269336 |

| Fatty Acid Methyl Ester (FAME) Mix | GC standard for lipid profile identification and quantification. | Supelco, 47885-U |

Visualizations

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Thesis Context: This support content is designed to address common technical barriers in fourth-generation biodiesel production research, specifically related to enhancing lipid yields in oleaginous microorganisms via advanced induction strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: In nitrogen-stress induction, my culture shows negligible lipid accumulation despite stationary phase. What is the primary cause? A: The most common cause is an insufficient Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C/N) ratio. A true nitrogen limitation is required. Verify your initial nitrogen concentration. For Yarrowia lipolytica, a C/N ratio >100 is often necessary. Check your nitrogen source; some strains may utilize trace nitrogen from impurities or yeast extract. Switch to a defined synthetic medium and use ammonium sulfate for precise control. Monitor depletion with a colorimetric assay.

Q2: During two-stage cultivation, I observe cell lysis or viability loss after switching to the lipid-accumulation stage. How can I mitigate this? A: This indicates a severe metabolic shock. Implement a more gradual transition. Do not simply centrifuge and resuspend; instead, perform a fed-batch or partial media exchange. Ensure the induction stage medium maintains essential micronutrients (Mg²⁺, Ca²⁺, trace elements) and a pH buffer. Sudden osmotic pressure change from high sugar concentration can also cause stress; consider using a less metabolically reactive carbon source like glycerol for the initial induction phase.

Q3: The addition of chemical triggers (e.g., NaCl, FCCP) drastically inhibits growth and overall lipid productivity. What is the optimal approach? A: Chemical triggers are highly concentration-specific and strain-dependent. You are likely using a cytotoxic concentration. Perform a detailed dose-response curve for biomass and lipid content. Add the trigger in the early to mid-exponential phase, not at inoculation. For uncouplers like FCCP, start at sub-micromolar ranges (0.5-5 µM). Always run a viability assay (e.g., methylene blue staining) in parallel.

Q4: My lipid extraction yield from stressed cells is lower than expected despite high in vivo fluorescence (Nile Red) signals. Why? A: This is a known discrepancy. Nutrient stress can alter cell wall rigidity (e.g., chitin accumulation), impairing solvent access. Implement a mechanical disruption step (bead beating, sonication) prior to the Bligh & Dyer or Folch extraction. Alternatively, use a two-step enzymatic (lyticase) and chemical digestion protocol. Verify your extraction solvent ratio is adjusted for the high carbohydrate content common in stressed cells.

Q5: How do I choose between nitrogen, phosphorus, or sulfur starvation for my novel marine microalgae strain? A: This requires a preliminary screening. Phosphorus starvation often leads to the fastest lipid induction but can severely impact biomass. Sulfur limitation can be very effective for certain hydrocarbons. Design a microplate experiment with controlled omission of each nutrient, monitoring lipid content (via fluorescence) and biomass over 96 hours. Refer to Table 1 for comparative outcomes.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Lipid Induction Strategies in Model Oleaginous Microorganisms

| Strategy | Organism | Key Condition/Trigger | Lipid Content (% Dry Cell Weight) | Lipid Productivity (mg/L/day) | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen Stress | Yarrowia lipolytica | C/N = 120, Glucose | 45-55% | 350-450 | Precise N-depletion timing |

| Two-Stage Cultivation | Chlorella vulgaris | Stage 1: N-replete; Stage 2: N-deplete, High Light | 40-50% | 180-220 | Scale-up of stage transition |

| Chemical Trigger (Uncoupler) | Rhodotorula toruloides | 2 µM FCCP at OD₆₀₀=10 | 48% | 310 | Cytotoxicity, cost |

| Phosphorus Stress | Nannochloropsis oceanica | P < 10% of replete level | 35-45% | 150-190 | Irreversible growth arrest |

| Chemical Trigger (Osmotic) | Schizochytrium sp. | 3% (w/v) NaCl | 55-60% | 400-500 | High energy for downstream |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Two-Stage Cultivation for Microalgae Objective: To decouple growth and lipid accumulation phases.

- Stage 1 (Growth): Inoculate culture in complete BG-11 medium (1.5 g/L NaNO₃). Incubate under continuous light (100 µmol photons/m²/s) with 2% CO₂ at 25°C with agitation until late exponential phase (OD₇₅₀ ~ 2.0).

- Harvest: Centrifuge culture at 3000 x g for 10 min at 25°C.

- Stage 2 (Induction): Resuspend biomass in nitrogen-deficient BG-11 medium (NaNO₃ omitted). Adjust initial OD₇₅₀ to 1.0.

- Induction Conditions: Increase light intensity to 300 µmol photons/m²/s, maintain 5% CO₂, 25°C. Supplement with 2% (w/v) sodium acetate.

- Monitor: Sample at 0, 24, 48, 72h for biomass (dry weight) and lipid analysis (in situ fluorescence or GC-FID).

Protocol 2: Dose Optimization for Chemical Uncoupler (FCCP) Objective: To determine the sub-cytotoxic concentration of FCCP that maximizes lipid accumulation.

- Culture Preparation: Grow yeast (R. toruloides) in YPD to mid-exponential phase (OD₆₀₀ = 8.0).

- Trigger Addition: Prepare FCCP stock solution in ethanol. Add to cultures to achieve final concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10 µM. Include an ethanol-only vehicle control (≤0.1% v/v).

- Incubation: Continue incubation for 48h under standard conditions.

- Analysis: At 48h, measure final OD₆₀₀ (biomass). Harvest cells, wash, and perform lipid extraction via Bligh & Dyer method. Calculate lipid content gravimetrically.

- Calculation: Determine lipid productivity (mg/L) = Biomass (mg/L) * Lipid Content (%). The optimal dose maximizes this product.

Diagrams

Diagram 1: Nutrient Stress Signaling Pathways to Lipid Accumulation

Diagram 2: Two-Stage Cultivation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Lipid Induction Experiments

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example/Catalog Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Defined Synthetic Medium | Eliminates unknown nitrogen sources, enabling precise C/N ratio control. Essential for reproducible stress studies. | D.YM + 60g/L Glucose (for yeast); Modified BG-11 (for algae). |

| Nile Red or BODIPY 493/503 | Vital fluorescent dyes for rapid, in situ quantification of neutral lipid content via plate reader or microscopy. | N3013 (Sigma); D3922 (Thermo Fisher). Must be prepared in DMSO. |

| Carbon Source (High-Purity) | The carbon backbone for lipid synthesis. Purity is critical to avoid trace nutrient contamination. | >99.5% Glucose, Glycerol, or Sodium Acetate. |

| Chemical Triggers (Uncouplers) | Induces metabolic redirection by dissipating proton motive force, forcing excess carbon flux to lipids. | Carbonyl cyanide 4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone (FCCP). Handle with care, light-sensitive. |

| Bead Beater/Homogenizer | Mechanical cell disruption is necessary for efficient lipid extraction from stress-hardened cell walls. | FastPrep-24 (MP Biomedicals) with 0.5mm zirconia beads. |

| FAME Standards | For calibration and quantification of lipid composition via Gas Chromatography (GC). Key for biodiesel quality prediction. | Supelco 37 Component FAME Mix. |

| Inhibitors of Competing Pathways | To channel metabolites towards lipid synthesis (e.g., inhibit β-oxidation or phospholipid synthesis). | Cerulenin (fatty acid synthase inhibitor), 3-Bromopyruvate. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my chitosan-based flocculation of Nannochloropsis sp. yielding inconsistent recovery rates (<80%)?

- Answer: Inconsistent recovery with cationic biopolymers like chitosan is often due to variable zeta potential and organic release. Chitosan's efficacy is highly pH-dependent.

- Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Measure Zeta Potential: Confirm culture is in late exponential/early stationary phase. Dilute a sample and measure zeta potential. The optimal range for chitosan is between pH 6-7, where the cells are negatively charged and chitosan is positively charged.

- Chitosan Stock Preparation: Ensure chitosan is dissolved in a 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution and sterile-filtered (0.22 µm). Old stock solutions can hydrolyze; prepare fresh weekly.

- Jar Test: Perform a standard jar test. Add chitosan (final conc. 10-150 mg/L) to 200 mL aliquots. Stir rapidly (150 rpm) for 2 min, then slowly (50 rpm) for 15 min. Let settle for 30 min. Sample the top layer for optical density (OD680) measurement.

- Check for Contaminants: Bacterial contamination can consume released organics and alter flocculation dynamics. Check via microscopy.

FAQ 2: My dissolved air flotation (DAF) unit is producing large, unstable bubbles, leading to low lipid-rich biomass recovery.

- Answer: Large bubbles are inefficient for attaching to and lifting microalgal cells. This is typically a saturator pressure or nozzle issue.

- Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Verify Saturator Conditions: Ensure the saturator pressure is maintained at 400-600 kPa. Use a calibrated pressure gauge. The water temperature should be <25°C for optimal gas dissolution.

- Inspect Nozzle/Release Valve: Clean or replace the pressure release valve/nozzle to ensure it creates a fine, milky white cloud of microbubbles (target diameter 10-100 µm).

- Coagulant/Flocculant Pre-treatment: DAF often requires a pre-flocculation step. Add a low dose of cationic starch (5-20 mg/L) or aluminum sulfate (10-50 mg/L) during slow mixing before the DAF inlet to form small, bubble-attachable flocs.

- Measure Bubble Size: Capture a video of the bubble cloud and analyze using image analysis software (e.g., ImageJ) to confirm bubble size distribution.

FAQ 3: During electrochemical harvesting, I observe excessive water electrolysis and high energy consumption without improved biomass recovery.

- Answer: This indicates an inappropriate electrode potential or current density, driving water splitting instead of algal cell destabilization.

- Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Characterize Electrolyte: Measure the conductivity of your culture medium. Low conductivity (<1.5 mS/cm) increases voltage requirements. You may adjust minimally with inert salts (e.g., NaCl, ≤0.1 M).

- Optimize Current Density: Run a controlled experiment varying current density. Use an Al or Fe anode and a stainless-steel cathode at a fixed distance (e.g., 1 cm). Apply densities from 10 to 150 A/m² in 20 A/m² increments for 10 minutes. Measure recovery and calculate energy consumption (kWh/kg biomass).

- Monitor pH Shifts: Electrolysis can cause extreme local pH shifts. Use a pH probe near the anode. If pH drops below 4 or rises above 10, consider pulse or alternating current (AC) to mitigate.

- Electrode Passivation: If using aluminum anodes, the formation of an oxide layer reduces efficiency. Periodically reverse polarity or clean the electrode with a dilute HCl wash.

Data Presentation: Comparative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Featured Harvesting Techniques for Chlorella vulgaris

| Technique | Key Parameter | Optimal Value | Harvesting Efficiency (%) | Energy Demand (kWh/kg biomass) | Processing Time (min) | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flocculation (Chitosan) | pH, Dosage | pH 6.5, 40 mg/L | 85 - 92 | 0.05 - 0.1 | 45 - 60 | Sensitive to water chemistry |

| Flotation (DAF) | Saturation Pressure, Recycle Ratio | 500 kPa, 30% | 88 - 95 | 0.5 - 1.2 | 10 - 20 | High capital/maintenance cost |

| Electrochemical (Al anode) | Current Density, Conductivity | 75 A/m², 1.8 mS/cm | 90 - 98 | 0.8 - 2.0 | 10 - 30 | Electrode dissolution, pH control |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Jar Test for Flocculant Screening Objective: Determine optimal dose and pH for a given flocculant.

- Prepare 6 x 500 mL beakers with 200 mL of homogeneous algal culture.

- Adjust pH of each beaker to a target value (e.g., 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10) using 0.1M HCl or NaOH.

- Under rapid mixing (150 rpm), add different doses of flocculant stock solution (e.g., 0, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100 mg/L).

- Rapid mix for 2 min, then slow mix (50 rpm) for 15 min.

- Stop mixing, allow to settle for 30 min.

- Carefully extract a 5 mL sample from 2 cm below the surface. Measure OD680.

- Calculate harvesting efficiency: HE (%) = [(ODinitial - ODfinal) / OD_initial] * 100.

Protocol 2: Bench-Scale Dissolved Air Flotation (DAF) Unit Operation Objective: Harvest biomass using DAF.

- Saturation: Pump clean water or a portion of clarified effluent into the pressure saturator tank. Maintain at 500 kPa with compressed air for ≥15 min.

- Conditioning: In a separate mixing tank, add the algal culture and coagulant dose (e.g., 20 mg/L cationic polyacrylamide). Mix gently (50 rpm) for 5 min to form microflocs.

- Flotation: Pump the conditioned culture into the DAF tank inlet. Simultaneously, release the pressurized water through a needle valve into the tank, creating microbubbles.

- Collection: Allow the bubble-floc aggregates to rise and form a sludge blanket at the top for 10-15 min.

- Skimming: Manually or mechanically skim the sludge from the surface. The clarified water exits from the bottom outlet.

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram 1: Decision Workflow for Harvesting Method Selection

Diagram 2: Electrochemical Harvesting Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents & Materials for Harvesting Experiments

| Item | Function & Specification | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan (Medium MW) | Cationic biopolymer flocculant; Degree of deacetylation >75%. | Flocculation of marine microalgae at near-neutral pH. |

| Polyaluminum Chloride (PAC) | Inorganic pre-polymerized coagulant; Basicity 70%. | Pre-treatment for DAF to form strong, shear-resistant flocs. |

| Cationic Starch (Starch-g-PAM) | Grafted polymeric flocculant; Low environmental impact. | Flocculation of freshwater species where biopolymer residue is a concern. |

| Aluminum Electrode (Sheet) | Sacrificial anode for electro-coagulation; Purity 99.5%. | Electrochemical harvesting in batch reactors. |

| Zeta Potential Analyzer | Measures surface charge of algal cells in mV. | Determining optimal dosage and pH for any chemical flocculant. |

| Laboratory DAF Unit (Bench) | Small-scale flotation system with saturator tank. | Screening floatability of different algal strains/coagulants. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is my in-situ transesterification yield from wet microalgae biomass consistently below 50%?

- Answer: Low yields with wet biomass are commonly due to excessive water content interfering with the catalyst and reaction equilibrium. Water hydrolyzes triglycerides to free fatty acids (FFAs) and can deactivate acid/base catalysts. Please refer to the protocol below (Protocol A) for a standardized method using moisture-tolerant catalysts and co-solvents. Ensure biomass moisture is characterized first—aim for a controlled water content below 20% w/w for optimal results. Recent studies (2023) indicate that using sulfonated zirconia catalysts at 65°C with a 1:12 biomass-to-methanol ratio (v/w) and 5% dimethyl ether as a co-solvent can improve yields to ~78% with 15% water content.

FAQ 2: My solid acid catalyst shows rapid deactivation during repeated cycles. What are the primary causes and regeneration strategies?

- Answer: Catalyst deactivation in this context is typically from (a) pore blockage/adsorption by biomass residues (fouling), (b) leaching of active acidic sites (e.g., SO3H- groups), or (c) poisoning by inorganic salts (e.g., Na+, K+, Mg2+) present in the biomass. A stepwise troubleshooting protocol is recommended:

- Post-reaction Wash: Rinse the recovered catalyst sequentially with hexane, ethanol, and deionized water to remove non-polar, polar, and ionic adsorbates, respectively.

- Thermal Regeneration: Dry the washed catalyst at 110°C for 2 hours, followed by calcination at 400°C for 4 hours under an inert atmosphere to burn off carbonaceous deposits.

- Re-sulfonation: If leaching is suspected (confirmed by ICP-MS of the reaction mixture), re-functionalize the catalyst support via reflux in concentrated sulfuric acid or re-impregnation. Table 1 summarizes common deactivation modes and solutions.

FAQ 3: How do I effectively separate the FAMEs (biodiesel) from the reaction mixture containing residual biomass solids and catalyst?

- Answer: This is a key downstream processing challenge. Implement a multi-stage separation workflow (see Diagram 1):

- Primary Solids Removal: Centrifuge the crude mixture at 8000 x g for 15 minutes to pellet biomass solids and catalyst powders.

- Liquid-Liquid Separation: Transfer the supernatant to a separation funnel. Add a volume of warm (40°C) deionized water equal to the supernatant volume and shake gently. Allow phases to separate for 1-2 hours. The upper organic layer will contain FAMEs and unreacted methanol/co-solvent.

- FAME Purification: Wash the collected organic layer with 5% w/v sodium bicarbonate solution to neutralize any residual acids, then with brine to remove water. Dry over anhydrous sodium sulfate before rotary evaporation to recover pure FAMEs.

FAQ 4: What analytical methods are recommended for monitoring reaction progress and final product quality according to current standards?

- Answer: Standard monitoring requires a combination of chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques. For reaction kinetics, use Gas Chromatography (GC-FID) with an internal standard (e.g., methyl heptadecanoate) to quantify FAME yield at regular intervals. For catalyst characterization, use FT-IR to confirm functional groups and XRD for structural integrity. Final biodiesel must meet ASTM D6751 or EN 14214 standards. Key quality parameters and their test methods are in Table 2.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Standardized In-Situ Transesterification of Wet Oleaginous Yeast (Lipomyces starkeyi)

- Objective: To directly convert lipids within wet yeast biomass to Fatty Acid Methyl Esters (FAMEs).

- Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table.

- Method:

- Biomass Preparation: Harvest L. starkeyi culture by centrifugation (5000 x g, 10 min). Do not lyophilize. Determine wet weight and moisture content via loss on drying.

- Reaction Setup: In a 250 mL round-bottom flask, combine 10g of wet biomass (70% moisture), 120 mL of anhydrous methanol, and 0.5g of heterogeneous catalyst (e.g., TiO2-SO3H). Add a magnetic stir bar.

- Reaction: Fit the flask with a reflux condenser. Heat the mixture to 65°C with vigorous stirring (600 rpm) for 8 hours under an inert N2 atmosphere.

- Termination & Separation: Cool the mixture to room temperature. Filter through a Buchner funnel with Whatman No. 1 filter paper to remove solids. Transfer the filtrate to a separation funnel.

- Purification: Follow the separation steps outlined in FAQ 3 (above).

- Analysis: Weigh the final FAME product and analyze by GC-FID per ASTM D6584.