Biomass to Hydrogen: A Comparative Analysis of Production Methods, Costs, and Future Outlook

This comprehensive analysis examines biomass-based hydrogen production technologies as sustainable pathways for decarbonizing energy systems.

Biomass to Hydrogen: A Comparative Analysis of Production Methods, Costs, and Future Outlook

Abstract

This comprehensive analysis examines biomass-based hydrogen production technologies as sustainable pathways for decarbonizing energy systems. The article explores thermochemical, biological, and electrochemical conversion methods, comparing their efficiency, scalability, and commercial viability. Drawing on recent research and commercial developments, it provides detailed techno-economic assessment of production costs, energy efficiency, and environmental impacts. Special attention is given to optimization strategies, system integration opportunities, and the critical role of interdisciplinary collaboration in advancing biomass hydrogen toward commercial maturity. This review serves as a strategic resource for researchers, energy professionals, and policymakers navigating the transition to sustainable hydrogen economies.

The Foundation of Biomass Hydrogen: Principles, Pathways and Environmental Significance

Hydrogen is increasingly recognized as a pivotal clean energy carrier for decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors such as transportation and industry. Its sustainability, however, is intrinsically linked to its production method. While conventional steam methane reforming (SMR) dominates current hydrogen production, it carries a significant carbon footprint, emitting between 9 and 12 kg of CO₂ per kilogram of hydrogen produced [1]. In the quest for sustainable alternatives, biomass-derived hydrogen, or biohydrogen, presents a compelling pathway. Biomass, encompassing agricultural residues, forestry by-products, and organic municipal waste, serves as a renewable and widely available feedstock. Its utilization for hydrogen production offers a dual advantage: enabling a circular economy by repurposing waste and providing a stable, carbon-neutral—or even carbon-negative—energy source [1] [2]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of biomass-based hydrogen production, focusing on its availability and inherent storage advantages over other prominent renewable hydrogen pathways.

Biomass Feedstock Availability and Types

The viability of biomass as a hydrogen feedstock is rooted in the diversity and abundance of its sources. Unlike solar and wind energy, which are intermittent, biomass is a storable and stable resource, mitigating issues related to energy output fluctuations [3]. The primary biomass sources can be categorized as follows:

- Agricultural Residues: This category includes materials like rice husks, wheat straw, and other crop leftovers. These are particularly attractive feedstocks as their use for energy does not compete directly with food production. In regions like India and China, where agricultural waste is abundant, gasification of these residues has demonstrated carbon savings of up to 85% compared to conventional methods [1].

- Forestry By-products: Wood chips, sawdust, and other waste from forestry operations represent a significant source of lignocellulosic biomass.

- Energy Crops: Plants specifically grown for energy production, though their use requires careful management of land resources.

- Organic Municipal Waste: The organic fraction of solid waste offers a solution for waste management while simultaneously producing energy.

The widespread availability of these feedstocks underscores the potential for localized hydrogen production, enhancing energy security and reducing transportation costs and associated emissions.

Comparative Analysis of Hydrogen Production Methods

Hydrogen can be produced from biomass through several technological pathways, primarily classified as thermochemical and biological processes. The following section details these methods and provides a data-driven comparison with other common hydrogen production routes.

Key Production Methods & Experimental Protocols

1. Biomass Gasification

- Experimental Protocol: Biomass gasification involves the thermal conversion of biomass in a controlled, oxygen-limited environment at high temperatures (700–1000 °C) [1]. The process begins with feedstock preparation, which includes drying and sizing. The biomass is then fed into a gasifier (e.g., a fluidized bed reactor), where it is converted into a mixture of gases known as syngas, primarily composed of hydrogen (H₂), carbon monoxide (CO), and carbon dioxide (CO₂). The syngas is subsequently cleaned to remove impurities like tars and particulate matter. The hydrogen yield is then enriched via a catalytic water-gas shift reaction, where CO reacts with steam (H₂O) to produce additional H₂ and CO₂ [4] [1]. Finally, hydrogen is separated and purified using techniques like pressure swing adsorption (PSA).

- Key Data: This process can achieve hydrogen yields of approximately 100 kg of hydrogen per ton of dry biomass, with an energy efficiency ranging from 40% to 70% (based on lower heating value) [4]. Advanced systems have increased the hydrogen content in syngas to over 60% [1].

2. Pyrolysis

- Experimental Protocol: Pyrolysis entails heating biomass to 400–800 °C in the complete absence of oxygen [1]. The process yields liquid bio-oil, solid biochar, and syngas. The syngas, containing up to 40% hydrogen, can be separated for use. Alternatively, the bio-oil can be upgraded via catalytic reforming to produce additional hydrogen. Dual-stage reactor designs are being developed to enhance hydrogen yields by 20–30% [1].

- Key Data: The syngas from pyrolysis typically contains up to 40% hydrogen. A significant co-benefit is the production of biochar, which can sequester up to 1 ton of CO₂ per ton of biomass processed [1].

3. Biological Hydrogen Production (Dark Fermentation)

- Experimental Protocol: Dark fermentation uses anaerobic bacteria to break down organic matter in biomass in the absence of light. The process requires a bioreactor maintained at specific temperature and pH conditions. The biomass feedstock is often pre-treated to hydrolyze complex carbohydrates into simpler sugars that the microbes can consume. The metabolic activity of the bacteria produces hydrogen and CO₂. Advances in metabolic engineering have been shown to increase hydrogen yields by up to 25% [1].

- Key Data: Dark fermentation has demonstrated hydrogen yields ranging from 1 to 3 mol H₂ per mol of glucose [1].

Quantitative Comparison of Production Pathways

The table below summarizes key performance indicators for biomass and other hydrogen production methods.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Hydrogen Production Methods

| Production Method | Feedstock | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) | Hydrogen Production Cost (USD/kg) | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) | Natural Gas | Very High (Commercial) | ~2-3 [4] | Cost-effective, high capacity | High CO₂ emissions (9-12 kg/kg H₂) [1] |

| Biomass Gasification | Biomass | Medium-High (TRL 5-7) [4] | ~3-4 (large-scale) [4] | Carbon-neutral/negative potential | Feedstock variability, tar formation [1] |

| Water Electrolysis (Renewable) | Water + Renewable Electricity | Medium-High | Competitive with biomass in many regions [4] | Very low operational emissions | High energy input, intermittent supply [5] |

| Biomass Pyrolysis | Biomass | Medium | N/A in results | Produces valuable biochar by-product | Lower hydrogen yield vs. gasification [1] |

| Dark Fermentation | Biomass (Organic Waste) | Low-Medium | N/A in results | Utilizes waste streams, low energy input | Low production rate, sensitivity to conditions [1] |

Table 2: Environmental Impact Profile (Well-to-Gate)

| Production Method | Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂-eq/kg H₂) | Water Usage | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMR (Gray Hydrogen) | 9 - 12 [1] | Moderate | Fossil-fuel dependent. |

| Biomass Gasification | -0.2 to 3.0 (with CCS) [1] | Moderate | Negative emissions achievable with CCS. |

| Renewable Electrolysis | 0.4 - 2.4 [1] | High (for ultra-pure water) | Highly dependent on electricity source. |

| Biomass Gasification (with CCS) | -15 to -22 kg CO₂eq per kg H₂ [4] | Moderate | One of the few pathways to negative emissions. |

Storage and Transportation Advantages

A critical challenge in the hydrogen economy is its storage and transportation. Biomass offers inherent logistical advantages in this domain.

- Solid-State Storage: Unlike gaseous hydrogen, which requires high-pressure compression (700 bar) consuming ~13% of its energy content, or liquid hydrogen, which incurs 30-40% energy losses during liquefaction, biomass is a solid at ambient conditions [1]. This allows for dense, stable, and safe storage without significant energy penalties.

- Simplified Logistics: The existing global infrastructure for harvesting, transporting, and storing biomass (e.g., using trucks, trains, and shipping) can be leveraged. This decentralized storage potential allows for production facilities to be located closer to the source of feedstock, reducing transportation costs for the final hydrogen product. Feedstock transportation can account for up to 40% of the total cost in decentralized systems, but this is often lower than the cost of building new hydrogen pipelines [1].

- Integration with Advanced Carriers: Biomass-derived hydrogen can be integrated with emerging storage technologies. For instance, the hydrogen produced can be bonded to Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers (LOHCs), which are safe to transport at ambient conditions. Furthermore, the biochar produced from pyrolysis can be considered a form of carbon storage, enhancing the overall negative emission potential of the pathway [1].

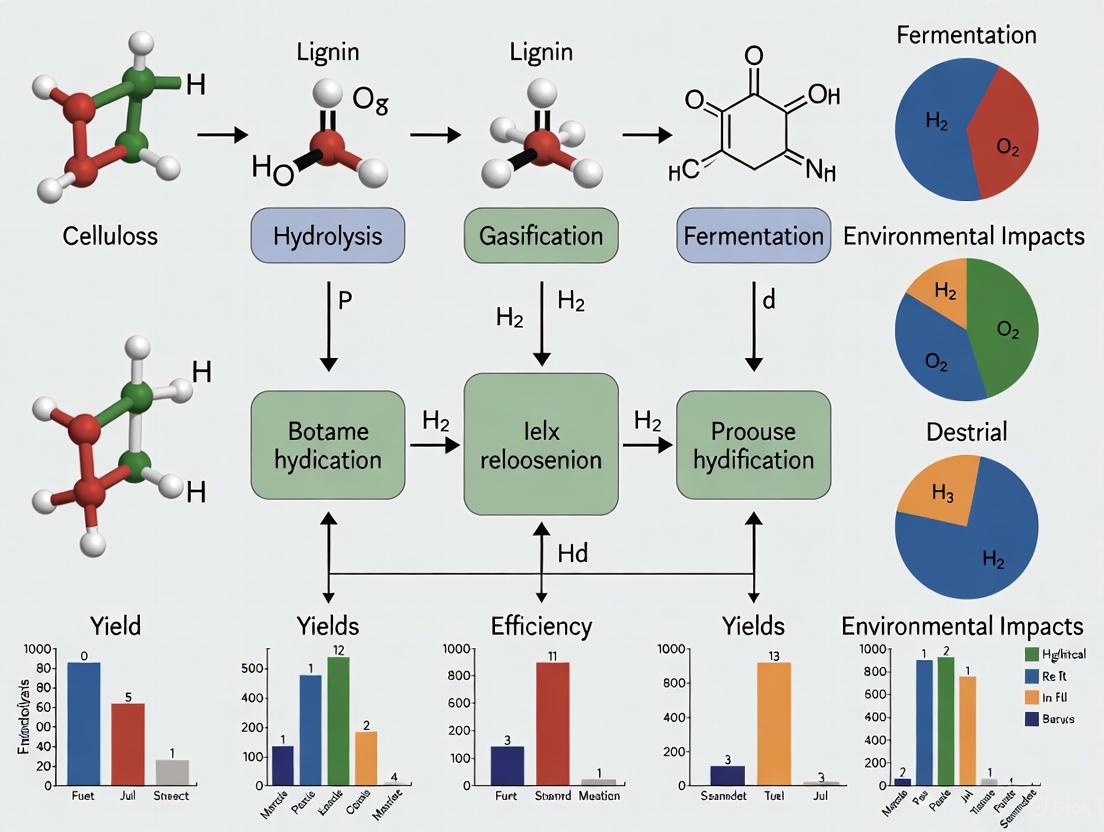

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow from biomass feedstock to stored hydrogen, highlighting key advantages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Research and development in biomass-to-hydrogen conversion rely on a range of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Iron Nanoparticles (encapsulated) | Act as a catalyst to disrupt and reform chemical bonds during biogas production, increasing efficiency. | Used in disruptive technological solutions for biogas sector transformation [6]. |

| Metal Oxide Catalysts (e.g., Fe₂O₃) | Serve as oxygen carriers in chemical looping gasification, enhancing syngas purity and hydrogen yield. | Manganese-doped Fe₂O₃ is used for chemical looping gasification to produce hydrogen-rich syngas [7]. |

| Anaerobic Bacterial Strains | Microorganisms that consume biomass and produce hydrogen as a metabolic by-product in fermentation. | Genetically engineered strains are used in dark fermentation to optimize hydrogen yields [1] [2]. |

| Nanoparticles (e.g., metal oxides) | Enhance electron transfer processes in microbial electrochemical systems, boosting biohydrogen production rates. | Added to dark fermentation or microbial electrolysis cells to improve metabolic activity and hydrogen yield [2]. |

| Metal Hydrides | Provide a solid-state, high-density medium for storing hydrogen gas post-production. | Evaluated in R&D for stationary storage applications with volumetric densities up to 150 kg/m³ [1]. |

Biomass stands out as a sustainable feedstock for hydrogen production due to its dual role in waste management and renewable energy generation. Its key advantages include widespread availability, carbon neutrality, and the potential for carbon-negative hydrogen when coupled with CCS. While technical challenges such as feedstock variability and process efficiency remain, advancements in gasification, pyrolysis, and biological methods, supported by machine learning and nanoparticle catalysts, are rapidly progressing [2]. Compared to other renewable pathways, biomass offers a unique combination of stable, storable feedstock and the potential for simplified, decentralized logistics. For researchers and policymakers, investing in cross-disciplinary collaboration between the biomass and hydrogen energy domains is essential to fully realize the innovative potential of biomass-based hydrogen and accelerate the transition to a sustainable hydrogen economy [3].

The global effort to limit temperature rise to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels requires not only deep decarbonization but also active removal of historical carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere [8]. In this context, hydrogen produced from biomass with carbon capture and storage (CCS) emerges as a uniquely promising technology. Unlike other hydrogen production pathways that aim for carbon neutrality, biomass hydrogen with CCS offers a genuine carbon-negative proposition, actively reducing atmospheric CO₂ concentrations [4]. This capability makes it an essential component in the portfolio of negative emission technologies (NETs) needed to achieve climate targets, particularly for decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors such as heavy industry and aviation [8].

The fundamental mechanism enabling carbon negativity is the closed carbon cycle of biomass. Plants absorb CO₂ from the atmosphere as they grow, and when this biomass is converted to hydrogen with permanent geological carbon storage, the net effect is permanent carbon removal [4]. This review provides a comparative analysis of biomass-based hydrogen production with CCS against other prominent hydrogen production methods, evaluating technological pathways, carbon footprints, economic viability, and research priorities within the broader context of carbon-negative energy systems.

Comparative Analysis of Hydrogen Production Pathways

Hydrogen production technologies are commonly categorized using a color spectrum that reflects their carbon intensity and production methodology. Grey hydrogen from fossil fuels without capture dominates current production but generates approximately 9 kg of CO₂ per kg of hydrogen [9]. Blue hydrogen applies carbon capture to fossil-based processes, reducing emissions by up to 90% [9]. Green hydrogen, produced via renewable-powered electrolysis, offers near-zero operational emissions but remains capital-intensive [10]. Bio-hydrogen with CCS represents a distinct category that combines biogenic carbon capture with permanent storage, achieving net-negative emissions when considering the full lifecycle [4].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Major Hydrogen Production Technologies

| Production Method | Feedstock | Primary Process | Carbon Intensity (kg CO₂/kg H₂) | TRL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grey Hydrogen | Natural Gas | Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) | ~8.5-9 [10] | 9 (Commercial) |

| Blue Hydrogen | Natural Gas | SMR with CCS | ~0.9-1.7 (90% capture) [9] | 7-8 (Demonstration) |

| Green Hydrogen | Water | Solar/Wind Electrolysis | 0-1 (operational) [11] | 7-8 (Commercial scaling) |

| Biomass Hydrogen with CCS | Biomass | Gasification with CCS | -15 to -22 kg CO₂eq [4] | 5-7 [4] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Lifecycle assessment (LCA) provides the most comprehensive evaluation of environmental performance across hydrogen production pathways. The carbon-negative signature of biomass hydrogen with CCS is clearly demonstrated in comparative LCA studies.

Table 2: Lifecycle Carbon Dioxide Emissions and Key Performance Indicators

| Production Method | Typical CO₂ Emissions (kg CO₂eq/kg H₂) | Energy Efficiency (%) | Production Cost ($/kg H₂) | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal Gasification | 20-25 [11] | 40-60% | 1.5-2.5 | Without CCS |

| Natural Gas SMR | 8.5-12 [10] | 70-85% | 0.67-1.31 [10] | Without CCS |

| Grid Electrolysis | Varies widely: 33.26 in Beijing [11] | 55-80% [10] | 2.5-5+ | Highly grid-dependent |

| Renewable Electrolysis | <1 (operational) [9] | 55-80% [10] | 2.28-7.39 [10] | Solar/Wind powered |

| Biomass Gasification | -15 to -22 with CCS [4] | 40-70% [4] | ~4.0 (3.0 with improvements) [4] | Large-scale plant, biomass at 20€/MWh |

The data reveal biomass hydrogen with CCS's unique position, with a net-negative carbon footprint of -15 to -22 kg CO₂eq per kg of hydrogen produced [4]. This contrasts sharply with fossil-based alternatives and even green hydrogen, which achieves carbon neutrality at best. The hydrogen yield from biomass gasification is approximately 100 kg of hydrogen per ton of dry biomass, with process energy efficiency typically ranging from 40-70% based on lower heating value [4].

Biomass Hydrogen Production: Mechanisms and Methodologies

Fundamental Process Description

Biomass gasification for hydrogen production converts organic feedstocks through thermochemical processes into a hydrogen-rich syngas. The technology operates in a controlled environment with limited oxygen at high temperatures (800–1,000°C), enabling partial oxidation that breaks down the complex hydrocarbon structure of biomass into simpler gaseous components [9]. The resulting syngas, primarily containing hydrogen, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and methane, undergoes subsequent purification and processing steps to isolate high-purity hydrogen.

The integration of carbon capture systems enables the separation of CO₂ from process streams for permanent geological storage. When this captured biogenic carbon is sequestered, the overall process achieves net-negative emissions because the carbon originally absorbed from the atmosphere by biomass during growth is permanently removed from the natural carbon cycle [4].

Experimental Protocols and Process Parameters

Research-scale and commercial biomass gasification protocols typically involve several critical steps with specific operational parameters:

Feedstock Preparation: Biomass (e.g., wood chips, agricultural residues, energy crops) is dried to moisture content below 15-20% and sized to 2-5 cm particles to ensure efficient gasification. Feedstock composition is characterized for proximate and ultimate analysis (moisture, volatile matter, fixed carbon, ash content, and elemental composition) [4].

Gasification Process: The prepared biomass is fed into the gasifier reactor operating at 800-1000°C. Different reactor configurations (fluidized bed, entrained flow, fixed bed) employ specific gasifying agents (air, oxygen, steam) with equivalence ratios (actual oxygen-to-biomass ratio relative to stoichiometric) typically between 0.2-0.4. Steam-to-biomass ratios range from 0.5-1.5 for optimized hydrogen production [4].

Syngas Cleaning and Conditioning: Raw syngas passes through cyclones and filters for particulate removal, then through scrubbers for tar and alkali removal. The clean syngas undergoes water-gas shift reaction (at 200-400°C with appropriate catalysts) to convert CO to additional H₂ and CO₂ [4].

Hydrogen Purification and Carbon Capture: Pressure Swing Adsorption (PSA) units separate high-purity hydrogen (99.99%) from CO₂, which is simultaneously captured for storage. Alternative approaches include membrane separation or physical/chemical absorption systems [4].

Carbon Storage Integration: Captured CO₂ is compressed, dehydrated, and transported via pipeline for permanent geological storage in depleted oil/gas reservoirs or deep saline aquifers, with continuous monitoring to ensure long-term integrity [8].

Diagram: Biomass to Hydrogen with CCS Process Flow

Carbon Flow and Negative Emissions Mechanism

The carbon-negative proposition of biomass hydrogen with CCS stems from its unique carbon flow pattern that creates a net transfer of carbon from the atmosphere to geological reservoirs.

Diagram: Carbon Flow in Biomass H2 with CCS

This diagram illustrates the fundamental mechanism enabling carbon negativity: atmospheric CO₂ is fixed by biomass growth, processed, and the carbon is permanently sequestered geologically, resulting in net carbon removal.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Analytical Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Analytical Methods

| Reagent/Equipment | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Gas Chromatography Systems | Syngas composition analysis | Quantifying H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄ concentrations in product streams |

| Pressure Swing Adsorption Units | Hydrogen purification and separation | isolating high-purity H₂ from gas mixtures; CO₂ capture integration |

| Water-Gas Shift Catalysts | Enhancing hydrogen yield | Converting CO to additional H₂ in shift reactors; typically iron-based or copper-zinc catalysts |

| Lifecycle Assessment Software | Environmental impact quantification | Calculating net carbon emissions using standardized methodologies (e.g., ISO 14040) |

| Gasifier Reactor Configurations | Process optimization | Testing different designs (fluidized bed, entrained flow) for specific feedstocks |

Integration with Broader Climate Strategy

The significance of biomass hydrogen with CCS extends beyond the energy sector to broader climate mitigation strategies. According to integrated assessment models used by the IPCC, limiting global warming to 1.5°C will require carbon removal on the order of 6 gigatons per year by 2050 [8]. Biomass hydrogen with CCS represents one of the few technologically plausible pathways to achieve this scale of carbon removal while simultaneously producing clean energy carriers.

This technology aligns with multiple UN Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 13 (Climate Action), and SDG 15 (Life on Land) [8]. When deployed using sustainable biomass feedstocks that avoid competition with food production or biodiversity loss, it can support a circular bioeconomy while providing essential carbon removal services [12].

Challenges and Research Frontiers

Despite its promise, biomass hydrogen with CCS faces several technical and economic challenges that represent active research frontiers. The technology currently stands at TRL 5-7, requiring demonstration of integrated operation at relevant scale to advance toward commercial maturity [4]. Key research priorities include:

- Feedstock Flexibility: Developing gasification systems that efficiently handle diverse biomass feedstocks with varying composition and moisture content [4]

- Impurity Management: Understanding and mitigating the effects of trace elements and impurities from biomass on downstream processes and fuel cell applications [4]

- System Integration: Optimizing the integration of CCS with gasification processes to maximize carbon capture efficiency while minimizing energy penalties [10]

- Cost Reduction: Advancing process improvements to reduce production costs from current estimates of ~$4/kg H₂ to below $3/kg H₂ [4]

The policy landscape also presents challenges, particularly regarding carbon accounting methodologies, monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) protocols for stored carbon, and economic incentives that properly value carbon-negative outcomes [8].

Biomass hydrogen production with carbon capture and storage represents a technologically viable pathway for achieving carbon-negative energy production. With a demonstrated lifecycle carbon intensity of -15 to -22 kg CO₂eq per kg of hydrogen [4], it offers a unique proposition in the portfolio of hydrogen production technologies. While current costs and technological maturity present barriers to immediate widespread deployment, its potential contribution to necessary carbon removal targets makes it an essential component of comprehensive climate mitigation strategies.

For researchers and industry professionals, priorities include advancing integrated system demonstrations, optimizing feedstock-to-hydrogen conversion efficiencies, developing robust MRV frameworks for carbon storage, and establishing policy support that recognizes the unique value of carbon-negative energy carriers. As climate models increasingly confirm the necessity of large-scale carbon removal, biomass hydrogen with CCS stands as one of the few technologies capable of delivering both clean energy and verifiable atmospheric carbon reduction.

Hydrogen is a versatile energy carrier with the highest energy density per unit mass among all fuels (approximately 120 MJ/kg) and produces zero carbon emissions during use, making it a cornerstone for decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors like heavy industry and long-haul transport [13] [14] [15]. While most hydrogen is currently produced from fossil fuels, sustainable hydrogen production from biomass offers a promising pathway for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and utilizing organic waste streams [16] [17]. Biomass resources, including agricultural residues, forestry waste, food waste, and dedicated energy crops, can be converted to hydrogen through three primary pathways: thermochemical, biological, and electrochemical processes [18] [16]. This review provides a comparative analysis of these conversion methodologies, examining their operational mechanisms, efficiency, technological readiness, and environmental impacts to inform research and development in sustainable hydrogen production.

Thermochemical Conversion Pathways

Thermochemical processes use heat and chemical reactions to convert biomass into hydrogen-rich syngas. These processes are generally characterized by high reaction rates and higher hydrogen yields compared to biological methods [17]. The main thermochemical pathways include gasification, pyrolysis, and steam reforming.

Gasification

Biomass gasification is a partial oxidation process occurring at temperatures between 600°C and 1500°C, using agents such as steam, oxygen, or air to produce syngas containing H₂, CO, CO₂, and CH₄ [13]. The process involves multiple complex reactions, including steam reforming and water-gas shift reactions, which enhance hydrogen yield [13]. Using steam as a gasification agent typically results in a higher hydrogen concentration in the syngas [13]. Gasification is considered one of the most developed thermochemical pathways, with research occurring at laboratory, bench, and pilot scales [13] [17].

Table 1: Summary of Hydrogen Yield from Biomass Gasification

| Feedstock | Gasification Agent | Temperature (°C) | H₂ Yield | Scale | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pine Sawdust | Steam | 900 | 7.3 wt% | Laboratory | [17] |

| Waste Wood | Steam | 900 | 5.9 wt% | Bench (2.5 kg/h) | [17] |

| Pine Wood Pellets | Steam | 800 | 1.8 wt% | Pilot Plant | [17] |

A specialized form of gasification, Supercritical Water Gasification (SCWG), is particularly suitable for high-moisture biomass (e.g., food waste, sewage sludge) as it eliminates the need for energy-intensive drying [19]. SCWG occurs in water above its critical point (374°C, 22.1 MPa), where unique properties facilitate efficient conversion of wet feedstocks into hydrogen-rich gas [19]. Reaction conditions, catalysts, and reactor design significantly influence process efficiency and H₂ yield [19].

Pyrolysis and Pyrolysis-Reforming

Pyrolysis is the thermal decomposition of biomass in the complete absence of oxygen at temperatures typically ranging from 300°C to 700°C, producing liquid bio-oil, solid biochar, and non-condensable gases [17]. The hydrogen content in the raw pyrogas from a single pyrolysis step is often limited [17].

To enhance hydrogen production, a two-step process involving pyrolysis followed by catalytic reforming of the volatile pyrolysis products (pyrogas/bio-oil) has been developed [17]. In the reforming step, volatiles react with steam over a catalyst (e.g., nickel-based catalysts) at high temperatures, which significantly increases hydrogen yield by breaking down heavier hydrocarbons [17]. This method offers advantages over direct gasification, such as avoiding catalyst deactivation by sintering and enabling optimized conditions in separate reactors [17]. Key factors influencing hydrogen yield include reforming temperature, steam-to-biomass ratio, and the type of catalyst used [17].

Table 2: Key Operational Parameters for Enhanced Hydrogen Production via Pyrolysis-Reforming

| Parameter | Influence on Hydrogen Yield | Optimal Trend |

|---|---|---|

| Reforming Temperature | Increases H₂ yield by promoting endothermic reforming reactions | Higher (e.g., >800°C) |

| Steam-to-Biomass Ratio | More steam favors water-gas shift reaction, boosting H₂ production | Higher ratio |

| Catalyst Type | Metal-based catalysts (e.g., Ni) are highly effective for C-C bond cleavage and reforming | Nickel-based, other metals |

Experimental Protocol: Catalytic Steam Reforming of Pyrolysis Volatiles

Objective: To determine the hydrogen yield from biomass via a two-step pyrolysis and catalytic steam reforming process.

Materials and Equipment:

- Feedstock: Dry, powdered biomass (e.g., pine sawdust, particle size ~0.5-1.0 mm).

- Reactor System: A two-stage reactor system comprising a pyrolysis unit (e.g., fluidized bed) connected in-series to a fixed-bed catalytic reformer.

- Catalyst: Nickel-based catalyst (e.g., Ni/Al₂O₃), crushed and sieved to 0.3-0.5 mm particles.

- Gas Supply: Nitrogen (N₂) as carrier gas and a steam generator.

- Analytical Equipment: Online Gas Chromatograph (GC) with TCD detector for syngas analysis, condensers for liquid collection, gas flow meters.

Methodology:

- Preparation: Load the catalyst into the fixed-bed reformer. Set the pyrolysis and reforming reactors to the desired temperatures (e.g., 500°C and 800°C, respectively).

- Initiation: Purge the system with N₂ to ensure an inert atmosphere. Start the steam generator to achieve the target steam-to-biomass ratio.

- Pyrolysis: Introduce the biomass feedstock into the pyrolysis reactor at a controlled feed rate. The biomass volatilizes, and the resulting vapors, gases, and carrier gas are transported to the reformer.

- Reforming: The pyrolysis volatiles contact the hot catalyst in the presence of steam. The catalytic reactions (steam reforming, water-gas shift) convert the volatiles into H₂, CO, and CO₂.

- Product Collection and Analysis: The gaseous effluent passes through condensers to trap any residual liquids. The non-condensable gas volume is measured, and its composition is analyzed in real-time by the GC to quantify H₂ yield.

- Calculation: Hydrogen yield is calculated based on the gas composition, flow rate, and the mass of biomass feedstock used.

Biological Conversion Pathways

Biological processes use microorganisms to convert biomass into hydrogen under mild temperatures and pressures. These pathways are typically robust and technologically mature but often have lower hydrogen yields and slower reaction rates than thermochemical processes [16] [17].

Dark Fermentation

Dark fermentation is an anaerobic process where fermentative bacteria break down complex organic compounds in biowaste (e.g., carbohydrates in food waste) to produce hydrogen, along with volatile fatty acids (VFAs) and CO₂ [16]. It does not require light and is considered one of the most promising biological methods for treating high organic content waste streams [16]. The process can achieve a hydrogen yield of 80-100 m³ per tonne of food waste, making it particularly suitable for wet feedstocks [16].

Photofermentation

Photofermentation uses photosynthetic bacteria (e.g., purple non-sulfur bacteria) to convert the volatile fatty acids produced in dark fermentation into hydrogen, using light as an energy source [16]. This process can be coupled with dark fermentation in a sequential system to significantly increase the overall hydrogen yield from the original substrate [16].

Experimental Protocol: Dark Fermentation of Food Waste

Objective: To evaluate biohydrogen production from food waste via dark fermentation.

Materials and Equipment:

- Inoculum: Mixed anaerobic consortia (e.g., from anaerobic digester sludge), pre-treated to inhibit hydrogen-consuming methanogens.

- Substrate: Food waste, homogenized and characterized for total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), and carbohydrate content.

- Reactor: Batch-scale anaerobic bioreactor with pH control, temperature control, and gas collection system.

- Media: Nutrient solution containing nitrogen, phosphorus, and micronutrients.

- Analytical Equipment: Gas Bag, Gas Chromatograph (GC) for H₂ analysis, HPLC for VFA analysis.

Methodology:

- Preparation: The bioreactor is loaded with the substrate (food waste), inoculum, and nutrient media in a defined ratio. The initial pH is adjusted to an optimal range (e.g., 5.5-6.0).

- Initiation: The reactor headspace is purged with an inert gas (e.g., N₂) to ensure anaerobic conditions. The reactor is then placed in a temperature-controlled environment (e.g., 35°C).

- Fermentation: The reaction is allowed to proceed for several days. The pH is automatically controlled, and the mixture is continuously agitated.

- Monitoring and Analysis: The volume of biogas produced is measured daily using the gas collection system. The hydrogen content in the biogas is analyzed by GC. Liquid samples are taken periodically to analyze VFA concentration via HPLC, indicating process efficiency and metabolic pathways.

- Calculation: Cumulative hydrogen production and the specific hydrogen yield (e.g., mL H₂/g VS added) are calculated.

Electrochemical Conversion Pathways

Electrochemical methods involve using electrical energy to facilitate hydrogen production from biomass-derived compounds, primarily in Microbial Electrolysis Cells (MECs).

Microbial Electrolysis Cells (MECs)

In MECs, electroactive bacteria on the anode oxidize organic matter in biowaste, releasing electrons and protons. The application of an external voltage (typically >0.2 V) drives these electrons through an external circuit to the cathode, where they combine with protons to form hydrogen gas [16]. This process can achieve higher hydrogen recovery from the substrate compared to fermentation alone and is effective for wastewater and other liquid organic waste streams [16].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow and logical relationship between the three primary biomass-to-hydrogen conversion pathways and their respective sub-processes.

Comparative Analysis of Pathways

The selection of an optimal biomass-to-hydrogen pathway depends on multiple factors, including feedstock characteristics, desired hydrogen yield, technological maturity, and economic and environmental considerations.

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Biomass-to-Hydrogen Conversion Pathways

| Parameter | Gasification | Pyrolysis-Reforming | Supercritical Water Gasification (SCWG) | Dark Fermentation | Microbial Electrolysis Cell (MEC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Feedstock | Dry biomass (agricultural, forestry residues) [13] | Dry biomass [17] | High-moisture biomass (food waste, sludge) [19] | Wet biowaste (food waste) [16] | Liquid waste streams [16] |

| Typical H₂ Yield | 1.8 - 7.3 wt% [17] | Can be significantly improved with catalysts [17] | Varies with conditions & catalysts [19] | ~80 m³/tonne food waste [16] | Higher recovery than fermentation [16] |

| Operating Conditions | 600-1500°C, various pressures [13] | Pyrolysis: 300-700°C; Reforming: >800°C [17] | >374°C, >22.1 MPa [19] | 35-37°C, ambient pressure [16] | Ambient conditions, external voltage ~0.2-0.8 V [16] |

| Technology Readiness Level (TRL) | Relatively high (lab to pilot) [13] [17] | Laboratory and pilot scales [17] | Research and development phase [19] | Technologically mature [17] | Research and development phase [16] |

| Key Advantages | High efficiency, scalable [13] | High H₂ yield, avoids catalyst sintering [17] | No drying needed, efficient for wet feedstocks [19] | Low energy input, waste treatment [16] | High efficiency, wastewater treatment [16] |

| Key Challenges/Disadvantages | Requires dry feedstock, tar formation [13] [17] | Multi-step process, catalyst cost/deactivation [17] | High-pressure operation, corrosion [19] | Lower H₂ yield, slow process [17] | Requires power input, system scaling [16] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This section details essential reagents, catalysts, and materials commonly used in experimental research for the featured hydrogen production pathways.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biomass Hydrogen Production Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel-based Catalyst (e.g., Ni/Al₂O₃) | Catalyzes steam reforming and water-gas shift reactions to enhance H₂ production. | Thermochemical processes, especially pyrolysis-reforming and gasification [17]. |

| Mixed Anaerobic Consortia | A community of microorganisms that ferment organic matter to produce hydrogen. | Dark Fermentation (requires pre-treatment to inhibit methanogens) [16]. |

| Purple Non-Sulfur Bacteria (e.g., Rhodobacter sphaeroides) | Photosynthetic bacteria that consume volatile fatty acids to produce H₂ using light energy. | Photofermentation, often in a sequential system following dark fermentation [16]. |

| Electroactive Bacteria (e.g., Geobacter spp.) | Form biofilms on anodes and oxidize organic compounds, releasing electrons. | Microbial Electrolysis Cells (MECs) [16]. |

| Supercritical Water (H₂O) | Serves as both reaction medium and reactant in a unique, dense fluid state. | Supercritical Water Gasification (SCWG) of wet biomass [19]. |

Thermochemical, biological, and electrochemical pathways each offer distinct mechanisms and potential for producing hydrogen from biomass. Thermochemical methods like gasification and pyrolysis-reforming generally provide higher hydrogen yields and are suitable for drier feedstocks, while biological methods like dark fermentation offer a lower-energy route for wet waste valorization. Emerging electrochemical methods like MECs promise high efficiency but require further development. The optimal pathway is highly dependent on feedstock type, desired scale, and technological maturity. Future research should focus on integrating these processes, developing more robust and cost-effective catalysts, and conducting comprehensive life-cycle assessments to guide the commercial-scale implementation of sustainable biomass-to-hydrogen technologies.

The transition to a sustainable energy system has positioned hydrogen as a crucial energy carrier and chemical feedstock. Biomass-based hydrogen production presents a promising route for utilizing renewable organic resources to achieve carbon-neutral energy solutions. Among the various technological pathways, thermochemical processes like gasification and pyrolysis, alongside biological processes such as fermentation, represent fundamental approaches with distinct operating principles, reaction mechanisms, and scalability potential. Understanding these core processes is essential for advancing research and development in renewable hydrogen production. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these foundational methods, examining their key chemical reactions, operational principles, and experimental data to inform researchers and industry professionals in the field of sustainable energy.

Fundamental Principles and Reaction Chemistry

Gasification

Biomass gasification is a thermochemical process conducted at high temperatures (600–1200°C) with a controlled amount of an oxidizing agent (air, oxygen, or steam) [20] [17]. The process sequentially undergoes drying (below 150°C), pyrolysis (250–700°C), oxidation (700–1500°C), and reduction (800–1100°C) stages [21] [20]. The primary outcome is syngas, mainly containing H₂, CO, CO₂, and CH₄ [20] [17].

The key heterogeneous and homogeneous reactions governing the process are detailed in Table 1 [20].

Table 1: Key Gasification Reactions and Thermodynamics

| Reaction Name | Chemical Equation | Enthalpy Change, ΔH₂₉₈ (kJ mol⁻¹) | Reaction Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Char Combustion | C + 0.5O₂ → CO | -111 | Exothermic |

| Boudouard | C + CO₂ → 2CO | +172 | Endothermic |

| Water-Gas | C + H₂O → CO + H₂ | +131 | Endothermic |

| Methanation | C + 2H₂ → CH₄ | -75 | Exothermic |

| Water-Gas Shift | CO + H₂O → CO₂ + H₂ | -41 | Exothermic |

| Methane Oxidation | CH₄ + 2O₂ → CO₂ + 2H₂O | -283 | Exothermic |

The water-gas shift reaction (WGS) is particularly crucial for hydrogen production, as it converts CO and H₂O into additional H₂ and CO₂ [20]. Gasification efficiency is highly temperature-dependent, with stable syngas yields reaching up to 90% at elevated temperatures [21]. Cold gas efficiency (CGE) typically ranges between 63% and 76%, varying with feedstock [21].

Pyrolysis

Pyrolysis is the thermal decomposition of biomass occurring in the complete absence of oxygen at temperatures ranging from 300°C to 700°C [17] [20]. The process converts biomass into three primary product streams: bio-oil (condensable vapors), biochar (solid carbonaceous residue), and non-condensable gases (including H₂, CO, CO₂, and CH₄) [17].

The fundamental reaction is summarized as: Biomass → Char + Tar + H₂O + Light Gas (CO + H₂ + CO₂ + CH₄ + C₂+) This global reaction is overall endothermic [20].

The yield distribution and gas composition are strongly influenced by operational parameters. Heating rate classifies pyrolysis as slow, intermediate, or fast [17]. Key operational parameters include temperature, residence time, and pressure [17]. The complex breakdown of primary biomass components (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) occurs at distinct temperature ranges: hemicellulose (200–327°C), cellulose (327–450°C), and lignin (200–550°C) [17]. Hydrogen and methane are primary gaseous products from lignin decomposition [17].

To enhance hydrogen yield, a two-stage process involving the catalytic reforming of pyrolysis volatiles (pyrogases) is often employed. This approach can avoid challenges associated with direct biomass gasification, such as catalyst deactivation by sintering [17].

Fermentation

Biological hydrogen production via fermentation utilizes microbial consortia to metabolize biomass-derived sugars in anaerobic conditions. The two primary methods are dark fermentation (DF) and photo-fermentation [22].

Dark fermentation involves anaerobic bacteria (e.g., Clostridium species) that break down carbohydrate-rich substrates, producing H₂, CO₂, and volatile fatty acids (VFAs) as byproducts. The metabolic pathway can be summarized as: C₆H₁₂O₆ + 2H₂O → 2CH₃COOH + 2CO₂ + 4H₂ This reaction is exothermic and occurs at moderate temperatures (typically 30–40°C) and atmospheric pressure [22].

Photo-fermentation employs photosynthetic bacteria (e.g., Rhodobacter species) that utilize light energy to convert VFAs from dark fermentation into additional H₂ and CO₂, overcoming the thermodynamic limitations of dark fermentation and improving overall yield [22].

Fermentation processes generally occur at lower temperatures and pressures compared to thermochemical routes, making them technologically robust and mature, though typically yielding hydrogen at a slower rate [17].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 2 provides a comparative summary of key performance indicators, operational conditions, and outputs for gasification, pyrolysis, and fermentation.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Hydrogen Production Pathways

| Parameter | Gasification | Pyrolysis | Fermentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Thermochemical partial oxidation | Thermochemical decomposition in absence of oxygen | Biological anaerobic digestion |

| Temperature Range | 600–1200°C [17] | 300–700°C [17] | 30–40°C (DF) [22] |

| Operating Pressure | Atmospheric to elevated [21] | Atmospheric [17] | Atmospheric |

| Primary Feedstock | Wood, agricultural residues, MSW [21] [20] | Energy crops, agricultural residues [17] | Carbohydrate-rich biomass, organic wastes |

| Main Hydrogen Carrier in Output | Syngas (H₂ + CO) | Pyrogas (H₂, CH₄, CO) | Biogas (H₂, CO₂) |

| Typical H₂ Yield | Up to 7.3 wt% (from pine sawdust at 900°C) [17] | Varies with catalysis & reforming [17] | Lower than thermochemical routes [17] |

| By-products | Biochar, tar, CO₂ | Bio-oil, biochar | Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs), CO₂, alcohols |

| Key Challenge | Tar management, high capital cost | Catalyst deactivation, product separation | Low yield, slow reaction rate, substrate pre-treatment |

| Technology Readiness Level (TRL) | High (Commercial scale) [22] | Medium (Lab/Pilot scale) [17] | Medium-High (Pilot/Demonstration) [22] |

| Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE) | 63% - 76% [21] | Not typically specified | Not Applicable |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Experimental Setup for Catalytic Steam Gasification

Objective: To produce hydrogen-rich syngas from biomass and evaluate the effects of temperature and catalyst on yield and composition [21] [20].

Materials and Equipment:

- Feedstock Preparation: Biomass (e.g., pine sawdust, wood pellets) dried and crushed to a particle size of 0.5-1.0 mm.

- Reactor System: Fluidized-bed or fixed-bed gasifier, equipped with a temperature controller and steam generator.

- Gasifying Agent: Steam and/or oxygen.

- Catalyst: Nickel-based catalyst or alkali metals (e.g., K₂CO₃) for tar reforming and yield enhancement.

- Analytical Instruments: Gas Chromatograph (GC) with TCD and FID detectors for syngas composition analysis, online gas flow meters.

Procedure:

- Loading: Place a predetermined amount of biomass feedstock (and catalyst, if used) into the reactor.

- Inert Atmosphere: Purge the reactor with an inert gas (e.g., N₂) to ensure an oxygen-free environment.

- Heating: Raise the reactor temperature to the target set point (e.g., 800–900°C) at a controlled heating rate.

- Steam Injection: Introduce superheated steam at a controlled steam-to-biomass ratio (e.g., 1.0–2.0).

- Reaction and Data Collection: Maintain at reaction conditions for a specified residence time. Continuously sample and analyze the produced syngas using GC at regular intervals to determine the composition (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) and flow rate.

- Calculation: Calculate hydrogen yield (wt%) and cold gas efficiency (CGE) based on the data.

Gasification Experimental Workflow

Two-Stage Pyrolysis-Reforming for Hydrogen Production

Objective: To maximize hydrogen yield by pyrolyzing biomass and subsequently catalytically reforming the volatile pyrogases [17].

Materials and Equipment:

- Feedstock: Dried and sieved biomass (e.g., agricultural residues).

- Reactor System: Two interconnected units: a pyrolysis reactor and a catalytic reformer.

- Catalyst: Metal-based catalysts (e.g., Ni, Pt) on Al₂O₃ or CeO₂ supports in the reformer.

- Carrier Gas: High-purity N₂.

- Analytical Instruments: GC/TCD for permanent gas analysis, GC/MS for tar speciation, condenser for bio-oil collection.

Procedure:

- Pyrolysis Stage: Feed biomass into the first reactor under a continuous N₂ flow. Heat to pyrolysis temperature (e.g., 500–600°C) to devolatilize the biomass, producing pyrogas, vapors, and leaving biochar.

- Volatile Transfer: Direct the hot pyrogas and vapors (excluding biochar) immediately into the second-stage reformer.

- Reforming Stage: Pass the volatiles through a bed of catalyst in the reformer, maintained at a higher temperature (e.g., 700–900°C). Steam may be co-fed to enhance the reforming reactions.

- Product Separation and Analysis: Condense any remaining heavy tars or liquids after the reformer. Route the non-condensable gas to a GC for composition analysis. Measure the total gas volume.

- Data Analysis: Determine the hydrogen concentration and total yield, evaluating the impact of catalyst type and reforming temperature.

Two-Stage Pyrolysis-Reforming Workflow

Dark Fermentation Hydrogen Production Protocol

Objective: To produce hydrogen from organic substrates using anaerobic bacteria and quantify the yield under defined conditions [22].

Materials and Equipment:

- Inoculum: Anaerobic sludge from wastewater treatment or pure cultures (e.g., Clostridium).

- Substrate: Synthetic media with glucose or real biomass hydrolysate.

- Reactor System: Anaerobic batch reactors (e.g., serum bottles) placed in a temperature-controlled incubator/shaker.

- Anaerobic Chamber: For oxygen-free preparation.

- Analytical Instruments: GC/TCD for biogas composition (H₂, CO₂), pH meter, spectrophotometer for substrate concentration.

Procedure:

- Media Preparation: Prepare a nutrient medium containing carbon source (e.g., glucose), macronutrients (N, P), and micronutrients.

- Inoculum Pre-treatment: Heat-treat the inoculum (e.g., 90°C for 15 min) to suppress hydrogen-consuming methanogens.

- Reactor Setup: In an anaerobic chamber, transfer media and inoculum to sealed serum bottles. Flush the headspace with inert gas (e.g., N₂) to ensure anaerobiosis.

- Incubation: Place reactors in an incubator at optimal temperature (e.g., 35°C) with constant shaking.

- Gas Sampling and Analysis: Periodically sample the headspace gas using a pressure-lock syringe. Analyze H₂ and CO₂ content via GC/TCD. Measure the volume of accumulated biogas by water displacement or using a pressure sensor.

- Liquid Analysis: Measure substrate degradation and volatile fatty acid (VFA) production (e.g., acetate, butyrate) via HPLC or GC.

- Calculation: Calculate cumulative hydrogen production and yield (mol H₂/mol glucose consumed).

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3 lists key reagents, catalysts, and materials essential for experimental research in biomass-based hydrogen production.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nickel-Based Catalyst | Catalytic tar reforming & syngas enhancement in gasification/pyrolysis | Ni/Al₂O₃, Ni/Olivine; Promotes water-gas shift & methane reforming [21] [17] |

| Alkali Metal Catalysts | In-bed catalyst for gasification, reduces tar | K₂CO₃, Na₂CO₃; Enhances carbon conversion efficiency [20] |

| Biomass Model Compounds | Simplified feedstock for fundamental reaction studies | Cellulose, Lignin, Xylan (Hemicellulose) [17] |

| Anaerobic Consortia | Biological hydrogen producer in fermentation | Heat-treated anaerobic sludge, Clostridium species [22] |

| High-Purity Gases | Create controlled atmospheres, act as gasifying agents | N₂ (inerting), O₂ (oxidation), Steam (gasification) [21] [20] |

| Supported Metal Catalysts | Reforming of pyrolysis volatiles to increase H₂ yield | Pt/Al₂O₃, Ni/CeO₂; Used in second-stage reformer [17] |

| Synthetic Nutrient Media | Support microbial growth in fermentation studies | Defined media with carbohydrates, nitrogen, phosphorus, micronutrients [22] |

This comparison elucidates the fundamental principles, reaction pathways, and experimental approaches for the three primary biomass-to-hydrogen production methods. Gasification operates as a high-temperature partial oxidation process, producing a syngas whose composition is governed by equilibria of reactions like water-gas shift and Boudouard. Pyrolysis relies on anaerobic thermal decomposition, with hydrogen yield significantly boosted by integrated catalytic reforming of volatiles. Fermentation utilizes microbial metabolism under mild conditions, though yields are generally lower than those from thermochemical routes.

The choice of technology depends on the specific feedstock, desired scale, and target product slate. Gasification currently demonstrates higher technology readiness for large-scale implementation, while pyrolysis-reforming and advanced fermentation processes show significant potential for future development. Cross-disciplinary collaboration between biomass and hydrogen energy domains is essential to address existing challenges, optimize reaction conditions, and drive innovation for a sustainable hydrogen economy.

Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) are a systematic metric used to assess the maturity level of a particular technology. Developed by NASA in the 1970s, the TRL scale ranges from 1 to 9, with TRL 1 being the lowest (basic principles observed) and TRL 9 the highest (actual system proven in successful mission operations) [23] [24]. This measurement system enables consistent, uniform discussions of technical maturity across different types of technology, allowing researchers, funding agencies, and policymakers to evaluate development progress and manage risks effectively [23] [25]. The methodology has since been adopted worldwide by organizations including the U.S. Department of Defense, European Space Agency, and European Commission for Horizon 2020 research programs [24].

For researchers and professionals in the hydrogen energy sector, understanding TRLs is crucial for making informed decisions about technology funding, development priorities, and commercialization pathways. The TRL framework provides a common language for comparing diverse technological approaches and identifying those most ready for commercial deployment [25]. This article applies the TRL framework to assess biomass-based hydrogen production methods within the broader context of a comparative analysis of renewable hydrogen technologies, providing researchers with critical data on commercial maturity across different production pathways.

TRL Scale and Definitions

The standard TRL scale consists of nine distinct levels, each representing a specific stage of technological development. The following table summarizes the official definitions from NASA and the European Union, which have been widely adopted across multiple sectors including energy technologies [23] [24].

Table 1: Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) Definitions

| TRL | NASA Definition | European Union Definition |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Basic principles observed and reported | Basic principles observed |

| 2 | Technology concept and/or application formulated | Technology concept formulated |

| 3 | Analytical and experimental critical function and/or characteristic proof-of-concept | Experimental proof of concept |

| 4 | Component and/or breadboard validation in laboratory environment | Technology validated in lab |

| 5 | Component and/or breadboard validation in relevant environment | Technology validated in relevant environment |

| 6 | System/subsystem model or prototype demonstration in a relevant environment | Technology demonstrated in relevant environment |

| 7 | System prototype demonstration in a space environment | System prototype demonstration in operational environment |

| 8 | Actual system completed and "flight qualified" through test and demonstration | System complete and qualified |

| 9 | Actual system "flight proven" through successful mission operations | Actual system proven in operational environment |

The progression through TRL stages represents a technology's journey from basic research (TRL 1-3) through technology development (TRL 4-6) and finally to system demonstration and deployment (TRL 7-9) [23]. For energy technologies like hydrogen production methods, reaching TRL 7-9 indicates readiness for commercial implementation, while technologies at TRL 4-6 may require further development and pilot-scale demonstration before being considered for full-scale deployment [26] [4].

TRL Assessment Methodology for Hydrogen Production Technologies

Standardized TRL Assessment Protocol

Assessing TRLs for hydrogen production technologies requires a structured methodology to ensure consistent evaluation across different processes. The following experimental protocol outlines the standardized approach for TRL determination:

Technology Characterization: Document the fundamental scientific principles, process configuration, and key performance parameters of the hydrogen production method [23] [26].

Development Milestone Mapping: Identify and verify specific achievements against TRL criteria, including laboratory experiments, prototype development, pilot demonstrations, and commercial deployments [4] [27].

Environment Relevance Evaluation: Assess the operational environment where the technology has been tested, distinguishing between laboratory, simulated relevant, and fully operational conditions [23] [24].

System Integration Assessment: Evaluate the level of integration of all subsystem components and their performance as a complete system [26] [4].

Performance Data Validation: Review operational data on efficiency, reliability, durability, and economic performance under relevant operating conditions [7] [5].

Independent Verification: Corroborate findings through multiple sources including peer-reviewed literature, patent analysis, and industry demonstration reports [7] [3].

This methodology enables objective comparison of diverse hydrogen production pathways and identification of specific development gaps that must be addressed to advance to higher TRL levels.

TRL Assessment Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the structured workflow for conducting TRL assessments of hydrogen production technologies:

Diagram 1: TRL Assessment Workflow

Comparative TRL Analysis of Hydrogen Production Methods

TRL Comparison Across Hydrogen Production Pathways

Hydrogen production technologies exhibit significant variation in their technology readiness levels, reflecting different stages of development and commercialization. The following table provides a comprehensive comparison of TRLs for major hydrogen production methods, with particular emphasis on biomass-based pathways:

Table 2: Technology Readiness Levels for Hydrogen Production Methods

| Production Method | Technology Description | TRL | Key Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steam Methane Reforming (SMR) | Conventional hydrogen production from natural gas | 9 | Widespread commercial deployment globally; mature technology with well-established supply chains [5] [27] |

| Alkaline Water Electrolysis | Electrochemical water splitting using alkaline electrolyte | 8-9 | Commercial systems available from multiple suppliers; proven operation at multi-MW scale [7] [5] |

| Biomass Gasification | Thermochemical conversion of biomass to syngas followed by hydrogen purification | 5-7 | Pilot and demonstration plants operating; main sub-processes mature but integrated operation at commercial scale needs further demonstration [4] [27] |

| Supercritical Water Gasification | Biomass gasification in supercritical water conditions | 4-5 | Laboratory and small pilot scale validation; technical challenges in pre-treatment and corrosion management [26] [21] |

| Biomass Pyrolysis with Reforming | Thermal decomposition of biomass followed by catalytic reforming of bio-oil | 4-6 | Laboratory validation to small pilot plants; process integration and catalyst durability require further development [27] |

| Dark Fermentation | Biological hydrogen production by microorganisms in absence of light | 3-4 | Experimental proof-of-concept and laboratory validation; low efficiencies and productivity limitations [27] |

| Photo-fermentation | Biological hydrogen production using photosynthetic bacteria | 2-3 | Basic principles observed and experimental proof-of-concept; significant research challenges in efficiency and scalability [27] |

| Integrated Solar Gasification | Hybrid system using solar thermal energy for biomass gasification | 2-3 | Basic technology research stage; concept validation in laboratory settings [26] |

Detailed Analysis of Biomass-Based Hydrogen Production TRLs

Biomass gasification for hydrogen production represents one of the most developed biomass-based pathways, with TRL estimates ranging from 5 to 7 depending on the specific technology configuration and assessment methodology [4]. The IEA Bioenergy Task 33 assessment indicates that while all main sub-processes have high technological maturity, there remains a need to demonstrate integrated operation of the complete hydrogen production chain at relevant scale to achieve higher TRL scores [4]. This technology offers the significant advantage of producing hydrogen with potential negative carbon emissions when combined with carbon capture and storage (CCS), with lifecycle assessments showing greenhouse gas emissions as low as -15 to -22 kg CO₂eq per kg of hydrogen produced [4].

Biomass pyrolysis pathways typically range from TRL 4-6, with fast pyrolysis systems generally at higher readiness levels than other variants [27]. The integration of pyrolysis with catalytic reforming of bio-oil represents a promising pathway, though challenges remain in catalyst durability and process integration at commercial scale.

Biological hydrogen production methods, including dark fermentation and photo-fermentation, generally exhibit lower TRLs (2-4) due to limitations in conversion efficiency, hydrogen productivity, and system scalability [27]. These pathways are characterized by lower operating temperatures and pressures compared to thermochemical routes but require significant research breakthroughs to improve efficiency and economic viability.

Emerging hybrid systems such as integrated solar gasification and supercritical water gasification remain at earlier development stages (TRL 2-5), facing specific technical challenges related to reactor design, materials compatibility, and process intensification [26] [21].

Experimental Protocols for TRL Advancement in Hydrogen Technologies

Standardized Testing Protocol for Biomass Gasification Systems

Advancing the TRL of biomass-based hydrogen production technologies requires rigorous experimental protocols at various development stages. The following standardized testing methodology provides a framework for systematic TRL progression:

Laboratory-Scale Validation (TRL 3-4)

- Reactor Configuration: Employ bench-scale fluidized bed or downdraft gasifier systems (0.5-5 kg/h biomass capacity)

- Process Parameters: Systematically vary temperature (700-900°C), pressure (1-20 bar), steam-to-biomass ratio (0.5-2.0), and residence time

- Performance Metrics: Measure hydrogen concentration in syngas, carbon conversion efficiency, cold gas efficiency, and tar content

- Analysis Methods: Gas chromatography for syngas composition, gravimetric analysis for tar quantification, standardized protocols for catalyst characterization

Relevant Environment Testing (TRL 5-6)

- System Configuration: Integrated pilot plant including biomass pretreatment, gasification, gas cleaning, and hydrogen purification subsystems

- Testing Duration: Minimum 500 hours of continuous operation to assess system stability and catalyst lifetime

- Feedstock Variety: Test with at least 3 different biomass feedstocks (agricultural residues, energy crops, woody biomass)

- Performance Validation: Verify hydrogen production efficiency (>40% LHV basis), purity (>99.5% for fuel cell applications), and system reliability (>90% availability)

Operational Environment Demonstration (TRL 7-8)

- Scale: Demonstration unit at commercial representative scale (>50 kg/h biomass input)

- Environment: Real-world industrial setting with actual biomass supply chain and hydrogen utilization pathway

- Testing Scope: Minimum 4,000 hours of cumulative operation addressing seasonal biomass variations

- Economic Data Collection: Comprehensive monitoring of capital and operating costs, maintenance requirements, and hydrogen production costs

This standardized protocol enables consistent comparison across different technology configurations and provides verifiable data for TRL assessment.

Technology Validation Parameters and Metrics

Table 3: Key Performance Indicators for Hydrogen Production TRL Assessment

| Validation Parameter | Laboratory Scale (TRL 4) | Pilot Scale (TRL 6) | Demonstration Scale (TRL 8) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Purity | >95% | >99.0% | >99.95% (fuel cell grade) |

| Cold Gas Efficiency | >50% | >60% | >65% |

| Carbon Conversion | >85% | >90% | >95% |

| Continuous Operation | 100 hours | 500 hours | >2,000 hours |

| Tar Content | <100 mg/Nm³ | <50 mg/Nm³ | <10 mg/Nm³ |

| System Availability | N/A | >85% | >92% |

| Hydrogen Production Cost | Conceptual estimate | ±30% accuracy | ±15% accuracy |

Research Reagents and Materials for Hydrogen Production Experiments

The experimental investigation and development of hydrogen production technologies require specific research reagents and specialized materials. The following table details essential components for conducting research across different TRL stages:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Hydrogen Production R&D

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Primary Function | TRL Application Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel-Based Catalysts | 15-25% Ni on Al₂O₃, MgO, or ZrO₂ supports; promoted with Ce, La | Steam reforming of methane and tar compounds; water-gas shift reaction | TRL 3-8 |

| Biomass Feedstocks | Characterized proximate/ultimate analysis; controlled particle size (0.5-5 mm) | Gasification/pyrolysis feedstock; standardized testing | TRL 3-8 |

| Alkaline Electrolyte | 25-30% KOH solution; semiconductor grade purity | Electrolyte for alkaline water electrolysis systems | TRL 3-9 |

| Specialized Alloys | Inconel 600/800; Hastelloy C276; SS316L | High-temperature reactor construction; corrosion resistance | TRL 4-9 |

| Pressure Swing Adsorbents | Zeolite 5A, 13X; activated carbon | Hydrogen purification from syngas streams | TRL 5-9 |

| Anion Exchange Membranes | Quaternary ammonium functionalized polymers; >50 μm thickness | Membrane for advanced electrolysis systems | TRL 3-7 |

| Metabolic Substrates | Glucose, sucrose, glycerol; analytical grade | Carbon source for biological hydrogen production | TRL 2-5 |

| Rare-Earth Oxide Catalysts | CeO₂-ZrO₂ mixed oxides; perovskite structures | Chemical looping catalysts; advanced reforming applications | TRL 2-6 |

The assessment of technology readiness levels across hydrogen production methods reveals a diverse landscape of technological maturity. While conventional methods like steam methane reforming and alkaline electrolysis have reached high TRLs (8-9), biomass-based pathways typically range from TRL 2-7, with gasification representing the most developed biomass conversion route [4] [27].

The TRL analysis identifies significant opportunities for advancing biomass-based hydrogen production through targeted research and development. Priority areas include integrated system demonstration to advance from TRL 5-7 to TRL 8-9, development of impurity management strategies for biomass-derived syngas, optimization of carbon capture integration for negative emissions hydrogen, and reduction of capital costs through process intensification [4] [21].

For researchers and policymakers, this TRL assessment provides a critical framework for strategic research planning and resource allocation. Cross-disciplinary collaboration between biomass and hydrogen energy domains, as identified in bibliometric studies, will be essential to address technical challenges and accelerate the commercial deployment of sustainable biomass-based hydrogen production [3]. Future research should focus on bridging the identified TRL gaps through integrated pilot demonstrations, advanced materials development, and systematic scale-up of the most promising biomass-to-hydrogen pathways.

The Role of Biomass Hydrogen in Global Decarbonization Strategies and Energy Security

The global pursuit of decarbonization has identified hydrogen as a critical energy carrier for transitioning hard-to-abate sectors away from fossil fuels. While much attention has focused on electrolytic hydrogen production, biomass-derived hydrogen (biohydrogen) presents a complementary pathway with distinct advantages for both emissions reduction and energy security. This comparative analysis examines biomass-based hydrogen production methods within the broader context of global decarbonization strategies, evaluating their technical maturity, economic viability, and environmental performance against competing alternatives. The analysis is particularly relevant as energy security concerns now drive decarbonization efforts alongside climate policy, creating new momentum for domestically sourced energy solutions [28].

Biomass hydrogen leverages organic feedstocks—including agricultural residues, forestry byproducts, and organic waste—to produce a clean fuel with potential carbon-neutral or even carbon-negative outcomes when coupled with carbon capture and storage (CCS). Unlike intermittent renewable sources, biomass can provide a stable, dispatchable feedstock for hydrogen production, enhancing energy security by reducing dependence on imported fuels and diversifying the domestic energy mix [4] [28]. This review systematically compares the technological pathways, applications, and strategic value of biomass hydrogen in the evolving global energy landscape.

Biomass Hydrogen Production Methods: A Comparative Technical Analysis

Several technological pathways exist for converting biomass into hydrogen, each with distinct operational principles, maturity levels, and performance characteristics. The primary methods include thermochemical processes (such as gasification and pyrolysis), biological approaches, and emerging integrated systems.

Thermochemical Conversion Pathways

Gasification represents the most technologically advanced pathway for biomass-to-hydrogen production. This process involves heating biomass at high temperatures (typically 800-900°C) in a controlled oxygen-starved environment to produce syngas (a mixture of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, and methane), followed by catalytic reforming and shifting to enhance hydrogen yield [4] [2].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biomass Hydrogen Production Methods

| Production Method | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) | Hydrogen Yield (kg H₂/ton dry biomass) | Energy Efficiency (LHV Basis) | Estimated Production Cost (€/kg H₂) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Gasification (Current) | 5-7 | ~100 | 40-70% | ~4.00 |

| Biomass Gasification with CCS | 5-7 | ~90-95 | 35-65% | <3.00 |

| Biomass Pyrolysis | 4-6 | 50-80 | 40-60% | 4.50-6.00 |

| Dark Fermentation | 3-5 | 5-20 | 20-35% | 6.00-10.00 |

| Microbial Electrolysis | 2-4 | 10-30 | 30-50% | 7.00-12.00 |

Table 2: Environmental Impact Assessment of Hydrogen Production Pathways

| Production Pathway | GHG Emissions (kg CO₂eq/kg H₂) | Carbon Sequestration Potential | Feedstock Flexibility | Water Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Gasification | 1.5-3.0 | Low | High | Medium |

| Biomass Gasification with CCS | -15 to -22 | High | High | Medium |

| Grid Electrolysis | 10-35 (varies with grid) | None | Low | High |

| Solar Electrolysis | 0.3-4.0 | None | Low | Medium-High |

| Wind Electrolysis | 0.2-2.5 | None | Low | Medium-High |

| Steam Methane Reforming | 10-14 | Low (without CCS) | Low | Low |

The integration of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) with biomass gasification enables negative carbon emissions, with lifecycle assessments showing greenhouse gas emissions as low as -15 to -22 kg CO₂eq per kg of produced hydrogen [4]. This positions biomass gasification with CCS as one of the few hydrogen production pathways that can actively remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere while producing energy.

Experimental Protocols for Biomass Gasification

Standardized Protocol for Laboratory-Scale Biomass Gasification

Objective: To determine hydrogen yield and syngas composition from various biomass feedstocks through controlled gasification experiments.

Materials and Equipment:

- Feedstock Preparation: Biomass feedstock (e.g., wood chips, agricultural residues) dried to ≤10% moisture content and sized to 1-5 mm particles

- Reactor System: Fluidized-bed gasifier with temperature control capability up to 1000°C

- Gas Analysis: Online gas chromatograph with TCD detector for H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄ quantification

- Feed System: Screw feeder with inert gas purge to prevent oxygen ingress

- Gas Cleaning Train: Cyclone separator, ceramic filters, and cooling system for particulate removal

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Calibrate all instruments, load biomass feedstock into feed hopper, verify inert gas flow

- Reactor Heating: Heat gasifier to target temperature (800-900°C) using external heaters under continuous inert gas flow

- Steam Introduction: Introduce superheated steam at controlled steam-to-biomass ratio (typically 0.5-1.5 w/w)

- Biomass Feeding: Initiate biomass feeding at predetermined rate (1-5 kg/h depending on reactor scale)

- Data Collection: After system stabilization (typically 30-45 minutes), collect gas composition data at 10-minute intervals for minimum 2 hours

- Product Analysis: Calculate hydrogen yield based on gas composition, flow rate, and biomass feed rate

- Char Collection: Quantify and characterize solid residues for carbon conversion calculations

Data Analysis:

- Hydrogen Yield (Y_H₂) = (Volumetric H₂ flow rate × Density of H₂) / Biomass feed rate

- Carbon Conversion Efficiency = (Carbon in gas products / Carbon in biomass) × 100%

- Cold Gas Efficiency = (Heating value of product gas / Heating value of biomass) × 100%

This protocol enables standardized comparison of hydrogen production potential across different biomass feedstocks and operating conditions, providing critical data for techno-economic assessments and scale-up calculations [4] [2].

Biomass Hydrogen in the Global Decarbonization Landscape

Strategic Role in Hard-to-Abate Sectors

Biomass hydrogen offers particular strategic value in sectors where direct electrification faces technical or economic barriers:

Industrial Applications: For high-temperature industrial heat, chemical production (ammonia, methanol), and metallurgical processes, biomass hydrogen provides a drop-in replacement for fossil fuel-derived hydrogen without requiring complete process overhaul [4] [29]. The existing infrastructure for hydrogen handling can be leveraged, reducing transition costs.

Transportation Fuels: Heavy-duty transport, shipping, and aviation represent challenging decarbonization sectors where biomass-derived hydrogen (either as pure H₂ or converted to synthetic fuels) offers energy density advantages over battery storage [30] [28]. Biohydrogen can be processed into sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) or marine fuels that integrate with existing distribution systems.

Power Generation: Hydrogen from biomass can provide dispatchable, clean power generation to complement intermittent renewables, enhancing grid stability and resource diversity [31] [28]. This is particularly valuable for regions with abundant biomass resources but limited renewable potential.

Energy Security Implications

The energy security dimension of biomass hydrogen has gained prominence following recent geopolitical events that disrupted global energy markets. According to DNV's Energy Transition Outlook 2025, energy security concerns are now reducing global emissions by 1-2% per year, outpacing the effects of traditional climate-focused regulations [28].

Biomass hydrogen enhances energy security through several mechanisms:

Domestic Resource Utilization: Countries with significant agricultural or forestry sectors can leverage domestic biomass resources for hydrogen production, reducing dependence on imported fossil fuels [4] [28].

Supply Stability: Unlike weather-dependent renewables, biomass can be stored and dispatched to provide consistent hydrogen production, offering reliability advantages for strategic energy applications [4].

Infrastructure Compatibility: Biomass hydrogen can utilize existing gas infrastructure for storage and distribution, reducing transition costs and maintaining flexibility in energy systems [28].

Rural Economic Development: Biohydrogen value chains can stimulate rural economies through biomass cultivation, collection, and processing activities, creating distributed energy production centers [2].

Comparative Analysis with Alternative Decarbonization Pathways

Biomass Hydrogen vs. Electrolytic Hydrogen

While electrolytic hydrogen production has dominated decarbonization discussions, biomass hydrogen presents complementary advantages:

Table 3: Systematic Comparison of Hydrogen Production Pathways

| Parameter | Biomass Gasification with CCS | Solar Electrolysis | Wind Electrolysis | Grid Electrolysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Cost | Medium-High | Medium | Medium-High | Low-Medium |

| Operating Cost | Medium (feedstock dependent) | Low (after commissioning) | Low (after commissioning) | High (electricity cost) |

| Capacity Factor | High (80-90%) | 15-25% | 25-45% | 50-90% |

| Land Use | Medium | High | High | Low |

| Intermittency | Low | High | High | Low |

| Carbon Intensity | Negative to Low | Low | Very Low | Medium to High |

| Energy Security Value | High | Medium | Medium | Low to Medium |

The optimal application of each hydrogen production method depends on regional resources, existing infrastructure, and specific end-use requirements. A diversified hydrogen strategy that includes both biomass and electrolytic pathways typically offers the most resilient approach to decarbonization [32] [31].

Integration with Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems

Research indicates that biomass hydrogen achieves maximum economic and environmental performance when integrated with other renewable technologies in hybrid systems [31]: