Biomass Conversion Optimization: Advanced Strategies for Enhancing Biorefinery Efficiency

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern strategies for improving biomass conversion efficiency in biorefineries, targeting researchers and bioprocess development professionals.

Biomass Conversion Optimization: Advanced Strategies for Enhancing Biorefinery Efficiency

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern strategies for improving biomass conversion efficiency in biorefineries, targeting researchers and bioprocess development professionals. We explore the fundamental bottlenecks in lignocellulosic biomass deconstruction, detail cutting-edge pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis methodologies, and address common operational challenges. A comparative evaluation of emerging technologies, including consolidated bioprocessing and AI-driven process control, highlights pathways to maximize yield, reduce costs, and accelerate the development of sustainable bio-based products and pharmaceuticals.

Understanding the Bottlenecks: Key Challenges in Lignocellulosic Biomass Conversion

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs for Biomass Conversion Experiments

This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges in lignocellulosic biomass conversion research, framed within the thesis context of improving conversion efficiency in biorefineries.

FAQ 1: Why is my enzymatic hydrolysis yield consistently low despite using a standard pretreatment protocol?

Answer: Low saccharification yields often stem from inadequate lignin removal or redistribution, residual hemicellulose, or cellulose crystallinity. First, verify your pretreatment severity. For dilute acid pretreatment, ensure the combined severity factor (log R₀) is calculated correctly: CSF = log(t * exp[(T-100)/14.75]) - pH. Target a CSF between 1.5 and 2.5 for hardwoods. If the CSF is correct, analyze the solid residue for acid-insoluble lignin (AIL) content via TAPPI T222 om-02. AIL should be below 20% for effective hydrolysis. If AIL is high, consider incorporating a sulfonation agent (e.g., Na₂SO₃) during pretreatment to modify lignin. Also, check for pseudo-lignin formation—a recondensed lignin-like material that can coat cellulose fibers—via FT-IR peaks at 1510 and 1660 cm⁻¹.

Experimental Protocol: Quantification of Pretreatment Severity and Compositional Analysis

- Calculate Combined Severity Factor (CSF): Record exact pretreatment temperature (T in °C), time (t in minutes), and initial pH of the acid solution.

- Compute Severity Factor (log R₀): R₀ = t * exp[(T-100)/14.75].

- Final CSF: CSF = log(R₀) - pH.

- Analyze Pretreated Solids:

- Dry biomass at 45°C until constant weight.

- Perform NREL/TP-510-42618 protocol for structural carbohydrates and lignin.

- For quick lignin check, use the Klason lignin method: hydrolyze with 72% H₂SO₄ for 1 hr at 30°C, dilute to 4%, autoclave at 121°C for 1 hr, filter, and weigh the acid-insoluble residue.

FAQ 2: How can I differentiate between recalcitrance caused by lignin versus hemicellulose acetylation?

Answer: A two-tiered diagnostic experiment is required. First, perform a selective deacetylation step on a portion of your pretreated biomass using a mild alkaline treatment (e.g., 0.1M NaOH at 25°C for 6 hours). Then, subject both the original and deacetylated samples to identical enzymatic hydrolysis. If the hydrolysis yield increases significantly (e.g., >15% relative increase) after deacetylation, acetyl groups are a major barrier. If the yield remains low, lignin is likely the primary culprit. Confirm by measuring the adsorption of cellulases (e.g., using a Bradford assay on supernatant before and after incubation with biomass). Lignin-rich residues typically adsorb >60% of added protein, severely limiting enzyme availability.

Experimental Protocol: Diagnostic for Acetyl vs. Lignin Recalcitrance

- Split Pretreated Biomass: Create two 1.0g (dry basis) samples.

- Sample A (Deacetylation): Treat with 50 mL of 0.1M NaOH. Shake gently at 25°C for 6 hours. Neutralize with HCl, wash thoroughly with DI water, and dry.

- Sample B (Control): Wash with pH 5.0 buffer and dry.

- Parallel Hydrolysis: Run enzymatic hydrolysis on both samples (15 FPU cellulase/g glucan, 50°C, pH 4.8, 72 hrs).

- Analyze: Measure glucose release at 24, 48, 72 hrs via HPLC or glucose analyzer.

- Calculate: % Yield Increase = [(Glucose from Sample A - Glucose from Sample B) / Glucose from Sample B] * 100.

FAQ 3: My cellulose accessibility measurements (e.g., Simons' stain) do not correlate with hydrolysis rates. What could be wrong?

Answer: Simons' stain relies on the differential adsorption of two dyed dextrans (Direct Orange and Direct Blue). A lack of correlation often indicates issues with dye purity, molecular weight calibration, or the presence of non-productive binding sites (e.g., in reprecipitated lignin). Ensure the Direct Orange 15 dye is purified via membrane filtration (10 kDa cutoff) to isolate the high molecular weight fraction. Furthermore, combine Simons' stain with a direct probe like the cellulose-binding module (CBM) based assay. Use a fluorescent-tagged CBM (e.g., from Clostridium thermocellum) to visualize accessible cellulose surfaces via confocal microscopy, which is less affected by lignin.

Experimental Protocol: Refined Simons' Staining with CBM Validation

- Dye Purification: Dissolve Direct Orange 15 in DI water, filter through a 10 kDa MWCO membrane, and recover the retentate. Verify molecular weight distribution via SEC.

- Staining: Follow the standard protocol (Chandra et al., 2015): incubate 0.1g biomass with serial dilutions of orange and blue dyes for 24h. Measure supernatant absorbance at 455 nm and 620 nm.

- CBM Binding: In parallel, incubate 0.05g biomass with 50 µg of Fluorescein-labeled CBM3a in 5 mL buffer (pH 6.0) for 1 hr.

- Analysis: Wash biomass extensively. Analyze fluorescence intensity of the solid residue using a plate reader or visualize via confocal microscopy. Plot CBM fluorescence intensity vs. Orange dye adsorption for a more robust correlation.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of Pretreatment Severity on Composition and Hydrolysis Yield (Miscanthus Example)

| Pretreatment Method | Combined Severity Factor (CSF) | Glucan Content (%) | Xylan Removed (%) | Lignin Removed (%) | 72-h Glucose Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 0.0 | 42.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 |

| Dilute Acid (160°C) | 1.8 | 58.7 | 75.2 | 18.3 | 68.4 |

| Dilute Acid (175°C) | 2.3 | 62.5 | 89.1 | 25.6 | 78.9 |

| Alkaline (NaOH, 120°C) | n/a* | 59.8 | 23.4 | 52.1 | 72.1 |

| Steam Explosion | 3.5 | 55.2 | 80.5 | 15.8 | 65.7 |

*Alkaline severity is measured by molarity-time (e.g., 0.1M-hr).

Table 2: Diagnostic Results for Recalcitrance Sources

| Biomass Type | Post-Pretreatment AIL (%) | Hydrolysis Yield Base (%) | Hydrolysis Yield Post-DeAc (%) | Protein Adsorption (%) | Primary Recalcitrance Identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn Stover (Dilute Acid) | 22.4 | 65.2 | 81.7 (+16.5) | 45.3 | Acetylation |

| Poplar (SPORL) | 28.9 | 51.8 | 54.1 (+2.3) | 71.2 | Lignin Adsorption |

| Switchgrass (AFEX) | 18.2 | 85.1 | 85.3 (+0.2) | 22.5 | Crystallinity/Other |

Visualizations

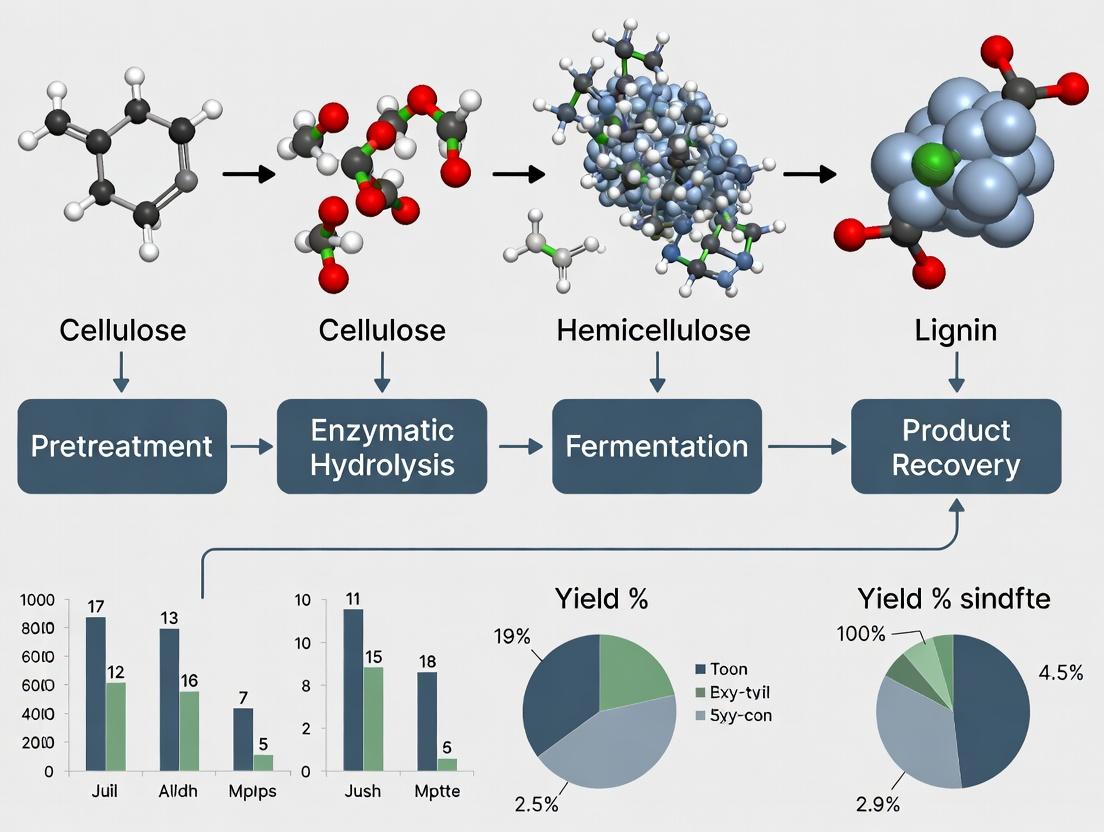

Diagram 1: Diagnostic Workflow for Recalcitrance

Diagram 2: Key Recalcitrance Barriers & Conversion Steps

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Recalcitrance Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Cellulase Cocktail (e.g., CTec3, HTec3) | Standardized enzyme mix for hydrolysis assays. Contains cellulases, β-glucosidase, and hemicellulases. | Always report loading in Filter Paper Units (FPU)/g glucan for reproducibility. |

| Direct Orange 15 (High MW Fraction) | Probe for accessible cellulose surface area (Simons' Stain). Binds to larger pores. | Must be membrane-purified (≥10 kDa) for consistent results. |

| Fluorescent-Tagged CBM (Cellulose-Binding Module) | Direct visualization of accessible cellulose via microscopy/fluorescence. | Use a well-characterized CBM (e.g., CBM3a from C. thermocellum). |

| Sulfonation Reagents (e.g., Na₂SO₃) | Additive during pretreatment to sulfonate lignin, reducing its inhibitory adsorption of enzymes. | Effective in sulfite-based pretreatments (e.g., SPORL) for woody biomass. |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [C₂mim][OAc]) | Powerful solvent for lignin and hemicellulose, effectively reducing crystallinity. | Requires meticulous recovery for cost-effectiveness; can inhibit enzymes if carryover occurs. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Surfactant added during hydrolysis to reduce non-productive enzyme binding to lignin. | Use a range of MWs (e.g., PEG 4000) to optimize for specific biomass types. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our lignocellulosic hydrolysis yield has dropped by >30% after switching to a new biomass supplier, despite using the same species. What are the primary diagnostic steps?

A: This is a classic symptom of feedstock variability. Follow this systematic diagnostic protocol:

- Immediate Pre-processing Check: Verify the moisture content of the new batch. High moisture (>15%) can dilute pretreatment chemicals. Dry a sub-sample to a standardized moisture level (e.g., 10%) and re-run a small-scale hydrolysis.

- Compositional Analysis: Perform a full NREL/TP-510-42618 compositional analysis on the old and new feedstock. Pay particular attention to:

- Acid-Insoluble Lignin (AIL): A increase can directly block enzyme access.

- Ash Content: High ash (especially silica or alkali metals) can inhibit enzymes and catalysts.

- Structural Carbohydrates: Variability in cellulose crystallinity and hemicellulose acetylation.

- Pretreatment Efficiency Test: Analyze the solid composition after your standard pretreatment but before hydrolysis. A successful pretreatment should significantly increase the accessibility of cellulose.

Diagnostic Workflow Diagram:

Title: Feedstock Failure Diagnostic Flow

Q2: How does particle size distribution from milling affect enzymatic saccharification yield, and what is the optimal range?

A: Particle size directly influences surface area, pretreatment reagent penetration, and enzyme accessibility. Excessively fine milling is energy-intensive with diminishing returns, while coarse particles limit conversion.

Table 1: Impact of Milled Particle Size on Saccharification Yield

| Feedstock (Poplar) | Mean Particle Size (µm) | Pretreatment | Glucose Yield (% Theoretical) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chip | >5000 | Dilute Acid | 45-55% | High energy for size reduction |

| Coarse | 1000-2000 | Dilute Acid | 65-72% | Practical balance for some systems |

| Fine | 150-500 | Dilute Acid | 78-85% | Common target for lab studies |

| Ultra-fine | <50 | Dilute Acid | 82-88% | High milling energy cost; may cause foaming/handling issues |

Recommended Protocol: Determining Optimal Particle Size

- Milling: Split a homogenized biomass sample. Mill using a knife-mill or vibratory ball mill to create 4 distinct size fractions (e.g., >1000µm, 500-1000µm, 150-500µm, <150µm). Sieve to verify.

- Standardized Pretreatment: Apply your standard dilute acid or alkaline pretreatment (e.g., 1% H₂SO₄, 160°C, 20 min) to identical masses of each fraction.

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Perform hydrolysis on the washed pretreated solids under controlled conditions (e.g., 15 FPU/g cellulose of CTec2, 50°C, pH 4.8, 72 hrs).

- Analysis: Measure glucose concentration via HPLC. Calculate yield as (glucose produced / potential glucose in raw biomass) x 100.

- Decision: Plot yield vs. milling energy input to identify the Pareto-optimal size.

Q3: We observe inconsistent fermentation inhibitor (furfural, HMF) formation across different biomass harvest seasons. How can we adjust pre-processing to mitigate this?

A: Inhibitor formation during pretreatment is highly dependent on biomass sugar and mineral content, which varies with harvest time (e.g., spring vs. fall). Mitigation is a function of pre-processing and pretreatment tuning.

Table 2: Inhibitor Mitigation Strategies Based on Feedstock Analysis

| Feedstock Profile | Observed Issue | Pre-processing Adjustment | Pretreatment Adjustment | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Pentosan (Spring Harvest) | High Furfural | Water Washing prior to pretreatment | Reduce Time/Temp during acid pretreatment | Furfural reduction by 40-60% |

| High Free Sugars (Frosted) | High HMF & Furfural | Drying & Storage to stabilize | Two-Stage: Mild Acid then Severity | Broad inhibitor reduction |

| High Ash (Agricultural Residue) | High Acetate, Alkali Salts | Leaching/Washing | Switch to Dilute Alkali Pretreatment | Lowers acetate, prevents neutralization |

Experimental Protocol: Water Washing for Inhibitor Reduction

- Sample Prep: Take 100g (dry weight equivalent) of the variable biomass.

- Washing: Add to 1L of deionized water at 50°C. Agitate for 30 minutes.

- Separation: Filter through a Büchner funnel. Retain both the solid and the washate.

- Analysis: Analyze the washate for water-soluble sugars, ash, and potential pre-formed inhibitors via HPLC/IC.

- Control: Compare pretreatment and hydrolysis of washed vs. unwashed solids. Monitor inhibitor profile in the pretreatment hydrolysate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Feedstock Variability Research

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| NREL Standardized Analytical Procedures (LAPs) | Provides the definitive, peer-reviewed methodology for compositional analysis (e.g., LAP "Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass"). Essential for generating comparable baseline data. |

| Commercial Enzyme Cocktails (e.g., CTec3, HTec3 from Novozymes) | Standardized, high-activity enzyme blends for saccharification experiments. Using a consistent cocktail removes enzyme variability as a factor, isolating the feedstock impact. |

| ANKOM Fiber Analyzer (or equivalent) | Enables rapid, semi-automated determination of Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF), Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF), and Acid Detergent Lignin (ADL). A quick screening tool for feedstock variability. |

| Standard Reference Biomasses (e.g., from NIST or NREL) | Corn stover, poplar, or pine samples with well-characterized composition. Critical as a control in every experiment batch to calibrate and validate your assay results. |

| Laboratory Ball Mill with Sieve Stack | Allows for the reproducible creation of specific, homogeneous particle size fractions. Key for decoupling the effects of physical vs. chemical variability. |

Feedstock Conversion Pathway Diagram

Title: Variability Introduction in Conversion Pathway

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ Category 1: Biomass Pre-treatment & Saccharification

Q1: Our enzymatic hydrolysis yields are consistently 15-20% below theoretical maximum. What are the primary troubleshooting steps?

- A: This is a common bottleneck. Follow this systematic guide:

- Inhibitant Analysis: Test hydrolysate for common inhibitors (furfurals, HMF, phenolics, organic acids) via HPLC. Compare concentrations to known inhibition thresholds (see Table 1).

- Enzyme Activity Assay: Perform a filter paper activity (FPA) assay on the enzyme cocktail post-reaction to check for deactivation.

- Biomass Characterization: Analyze pre-treated biomass for lignin content (via Klason method) and cellulose crystallinity (via XRD). High residual lignin or crystallinity reduces enzyme accessibility.

- Process Parameter Check: Verify and recalibrate pH, temperature, and mixing speed sensors. Even slight deviations (e.g., pH 4.8 vs 5.0) can significantly impact enzyme performance.

- A: This is a common bottleneck. Follow this systematic guide:

Q2: After switching to a new lignocellulosic feedstock, our pre-treatment energy consumption has spiked. How can we optimize this?

- A: Feedstock variability is a major economic hurdle. Implement the following:

- Conduct a compositional analysis (NREL/TP-510-42618) to determine the new feedstock's lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose ratios.

- Run a severity factor (Log R₀) optimization experiment. Systematically vary time and temperature to find the minimum severity needed for effective delignification.

- Consider a two-stage pre-treatment (e.g., mild acid followed by alkali) to selectively remove hemicellulose and lignin with lower combined energy input than a single severe stage.

- A: Feedstock variability is a major economic hurdle. Implement the following:

FAQ Category 2: Fermentation & Microbial Inhibition

Q3: Our fermentation titers and productivity drop significantly when using undetoxified hydrolysate versus pure sugar media. How do we diagnose the issue?

- A: This indicates microbial inhibition. The protocol is:

- Dose-Response Assay: Grow your production microorganism (e.g., S. cerevisiae, E. coli) in media with increasing percentages (10%, 25%, 50%, 75%) of the undetoxified hydrolysate. Plot growth rate (OD600) and product formation against % hydrolysate.

- Inhibitor-Specific Testing: Supplement pure sugar media with suspected individual inhibitors (e.g., 1 g/L furfural, 2 g/L acetic acid) identified in Q1-A1. Identify the most toxic compound(s).

- Detoxification Trial: Test biological (enzyme laccase), physical (overliming, activated charcoal), or membrane-based detoxification methods. Compare cost and efficiency of each.

- A: This indicates microbial inhibition. The protocol is:

Q4: We are experiencing diauxic growth in our co-fermentation of C5 and C6 sugars, extending batch time. What genetic or process engineering solutions exist?

- A: Sequential sugar consumption is a key efficiency loss.

- Verify the Problem: Monitor sugar concentrations (Glucose, Xylose, Arabinose) hourly via HPLC. Confirm glucose is consumed first, causing a lag phase.

- Strain Selection/Engineering: If using native strains, screen for mutants with relieved carbon catabolite repression (CCR). For engineered strains (e.g., xylose-utilizing S. cerevisiae), ensure constitutive expression of xylose assimilation pathway genes.

- Process Optimization: Consider fed-batch operation where sugar concentrations are kept low and balanced to prevent CCR trigger.

- A: Sequential sugar consumption is a key efficiency loss.

FAQ Category 5: Analytics & Mass Balance Closure

- Q5: Our overall mass balance for the integrated process consistently closes at <85%. Where are the likely losses?

- A: Poor mass balance closure invalidates economic and energy analyses. Follow this audit:

- Account for Gaseous Products: Measure CO₂ evolution off-gas using a gas analyzer or mass flow meter. This is often a major unaccounted stream.

- Analyze Waste Streams: Quantify solids in waste water (filtration and drying) and characterize volatile compounds lost in evaporative steps (e.g., during pre-treatment).

- Calibrate All Sensors: Recalibrate pH, temperature, flow, and load cells. Weigh all input and output streams manually to verify automated system data.

- Check for Degradation Products: Run detailed GC-MS on process streams to identify and quantify volatile degradation products not captured by standard HPLC.

- A: Poor mass balance closure invalidates economic and energy analyses. Follow this audit:

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Inhibitors in Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates & Their Typical Inhibition Thresholds

| Inhibitor Class | Example Compound | Typical Inhibition Threshold* (for common fermentative microbes) | Common Detection Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Furan Derivatives | Furfural | 1 - 2 g/L | HPLC-UV |

| Furan Derivatives | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) | 2 - 5 g/L | HPLC-UV |

| Weak Organic Acids | Acetic Acid | 2 - 5 g/L (pH dependent) | HPLC-RI or IC |

| Phenolic Compounds | Vanillin, Syringaldehyde | 0.5 - 1.5 g/L | HPLC-MS |

| Inorganic Ions | Sodium, Chloride | Varies widely by microbe | ICP-MS |

*Thresholds are strain-dependent and can be synergistic. Always conduct dose-response assays.

Table 2: Comparative Energy Input of Common Pre-treatment Methods (Theoretical Ranges)

| Pre-treatment Method | Typical Temperature Range (°C) | Typical Pressure Range | Relative Energy Demand (Index) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilute Acid | 140 - 190 | 10 - 15 bar | High (1.0) | Effective hemicellulose removal |

| Steam Explosion | 160 - 230 | 10 - 35 bar | Medium-High (0.9) | No chemical catalyst required |

| Ammonia Fiber Expansion (AFEX) | 60 - 120 | 10 - 30 bar | Medium (0.7) | Low inhibitor formation |

| Liquid Hot Water | 170 - 230 | 10 - 50 bar | High (1.0) | Simple operation |

| Organosolv | 150 - 200 | 10 - 30 bar | Very High (1.3) | High-purity lignin co-product |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening for Inhibitor-Tolerant Microbial Strains Objective: Identify mutant or natural strains with enhanced resistance to hydrolysate inhibitors. Materials: 96-well microplate, multi-channel pipette, hydrolysate stock, YPD or defined media, target microbial strain library, plate reader. Methodology:

- Prepare a gradient of hydrolysate in media across the plate's columns (0%, 10%, 20%, ... 80% v/v).

- Inoculate each row with a different microbial strain from the library. Use a positive control (no hydrolysate) and negative control (no inoculum).

- Seal plates and incubate in a plate reader at 30°C (or optimal growth temp) with continuous orbital shaking.

- Monitor OD600 every 30 minutes for 48-72 hours.

- Calculate maximum growth rate (μmax) and lag time for each strain at each inhibitor concentration. Select strains with the smallest relative increase in lag time and highest μmax at elevated inhibitor levels.

Protocol 2: Detailed Mass and Energy Balance for a Batch Conversion Process Objective: Accurately close mass and energy balances around a bench-scale integrated biorefinery unit operation. Materials: Bench-scale reactor, calibrated load cells, condensers, gas collection bags, thermocouples, flow meters, analytical equipment (HPLC, GC, elemental analyzer). Methodology:

- Mass In: Precisely weigh all input biomass, chemicals, and water. Record initial conditions.

- Process Monitoring: Log all energy inputs (electrical for stirring, heating mantle power consumption) and outputs (cooling water flow/ΔT). Collect all output streams separately: solid residue, liquid hydrolysate, condensate from vapors, and non-condensable gases.

- Stream Analysis: Characterize each output stream (mass, composition, enthalpy where applicable).

- Calculation:

- Mass Closure: Σ(Output Masses) / Σ(Input Masses) x 100%.

- Energy Balance: Σ(Energy Inputs + Heats of Reaction) = Σ(Energy in Output Streams + Heat Losses). Use standard heats of formation for biomass components to estimate reaction enthalpies.

- Identify Discrepancies: Losses >5% warrant investigation into unmeasured streams (e.g., aerosols, volatile products, calibration error).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Biomass Conversion Research |

|---|---|

| Cellulase Cocktail (e.g., CTec2/3) | Multi-enzyme blend containing endoglucanases, exoglucanases, and β-glucosidases for hydrolyzing cellulose to glucose. |

| Laccase Enzymes | Used for biological detoxification of hydrolysates by polymerizing and removing phenolic inhibitors. |

| External Standard Mix (for HPLC) | Contains cellobiose, glucose, xylose, arabinose, furfural, HMF, acetic acid, etc., for quantifying sugars and inhibitors. |

| Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF) Kit | For sequential fiber analysis (NDF, ADF, ADL) to determine lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose content in biomass. |

| Yeast Nitrogen Base (YNB) | Defined medium component for constructing selective media for engineered auxotrophic yeast strains during fermentation. |

| Solid Acid Catalyst (e.g., Amberlyst-15) | Used in catalytic pre-treatment or conversion steps to avoid mineral acid corrosion and enable easier recycling. |

| Gas Collection Bag (Tedlar) | For capturing and analyzing non-condensable gaseous products (CO₂, H₂, CH₄) from fermentation or thermochemical processes. |

Visualizations

Title: Integrated Biorefinery Flow with Troubleshooting Nodes

Title: Microbial Inhibition Pathways and Mitigation Solutions

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: How can I improve a low conversion efficiency in my enzymatic hydrolysis process?

- Answer: Low conversion efficiency often stems from suboptimal reaction conditions or inhibitory effects.

- Check Substrate Accessibility: Ensure biomass pre-treatment (e.g., steam explosion, dilute acid) is sufficient to break down lignin and reduce cellulose crystallinity. Inadequate pre-treatment is a common cause.

- Optimize Enzyme Cocktail: Ensure the enzyme blend (cellulases, hemicellulases) is appropriate for your feedstock. Test different commercial formulations or ratios. Monitor and maintain optimal pH (typically 4.8-5.0) and temperature (45-50°C).

- Mitigate Inhibitors: Analyze pre-treatment hydrolysate for inhibitors like furfurals, phenolics, or organic acids. Consider detoxification steps (overliming, activated charcoal adsorption) or use inhibitor-tolerant enzyme/microbial strains.

- Protocol - Inhibitor Screening: Prepare dilutions of your pre-treatment liquor. Add to standard hydrolysis assays with your enzyme cocktail and a control cellulose substrate (e.g., Avicel). Measure sugar release over 72 hours to quantify inhibition.

FAQ 2: My fermentation yield is lower than theoretical. What are the primary culprits?

- Answer: Reduced yield indicates carbon loss to byproducts, maintenance energy, or non-target metabolism.

- Analyze Byproduct Spectrum: Use HPLC to profile fermentation broth for acetate, lactate, glycerol, or ethanol (in a target bioproduct process). Their presence indicates metabolic flux diversion.

- Check for Contamination: Perform gram stains and plate cultures on non-selective media. Microbial contaminants consume substrate and produce unwanted metabolites.

- Evaluate Nutrient Balance: Ensure the medium is not limited in critical nutrients (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus, trace metals) that force the organism into a maintenance state. Refer to the defined medium recipe in the toolkit below.

- Protocol - Carbon Balance Analysis: Ferment with known initial substrate (e.g., glucose) concentration. At endpoint, measure: 1) Product concentration, 2) Residual substrate, 3) Major byproduct concentrations (via HPLC), and 4) Cell biomass (via DCW). Account for all carbon to identify major losses.

FAQ 3: How do I address a sudden drop in titer during a scaled-up bioreactor run?

- Answer: Scale-up issues often relate to mass transfer, feeding strategies, or parameter control.

- Verify Oxygen Transfer (for aerobic processes): Calculate the kLa (volumetric oxygen transfer coefficient). Insufficient oxygen can cripple growth and production. Increase agitation or aeration rate if possible, while managing shear stress.

- Review Substrate Feeding: For fed-batch processes, a drop may coincide with the start of feeding. Ensure the feed concentration and rate are correct to avoid overflow metabolism or inhibition.

- Check for pH or Temperature Drifts: Calibrate bioreactor probes. A drift outside the optimal window can halt metabolism.

- Assess Mixing Homogeneity: Use a tracer or dye to check for dead zones where substrate or base/acid accumulates, creating local inhibitory conditions.

Table 1: Benchmark Ranges for Key Biorefining Metrics (Common Feedstocks)

| Metric | Typical Range (Corn Stover) | Typical Range (Sugarcane Bagasse) | Theoretical Maximum (Glucose to Product X) | Common Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conversion Efficiency | 75-90% (Enzymatic Glucose Release) | 70-88% (Enzymatic Glucose Release) | 100% | NREL LAP: "Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin" |

| Yield (Yp/s) | 0.35-0.45 g/g (e.g., Succinic Acid) | 0.30-0.40 g/g (e.g., Ethanol) | 0.72 g/g (Succinic Acid from Glucose) | HPLC analysis of product/substrate |

| Titer | 50-100 g/L (Succinic Acid in Fed-Batch) | 40-80 g/L (Ethanol in Batch) | N/A (Process Dependent) | HPLC or spectrophotometric assay |

Experimental Protocol: Determining Conversion Efficiency

Title: Standard Protocol for Enzymatic Saccharification Conversion Efficiency

Objective: To determine the percentage conversion of glucan in pre-treated biomass to glucose.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Method:

- Biomass Preparation: Mill pre-treated biomass to pass a 20-mesh screen. Precisely weigh 100 mg (dry weight equivalent) into a 10 mL pressure tube.

- Buffer Addition: Add 5.0 mL of 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.8).

- Enzyme Loading: Add a commercial cellulase cocktail at a standard loading of 20 filter paper units (FPU) per gram of biomass. Add β-glucosidase at 40 cellobiose units (CBU) per gram to prevent cellobiose inhibition.

- Incubation: Cap tubes and incubate in a shaking incubator at 50°C, 150 rpm, for 72 hours.

- Termination & Analysis: Heat samples to 95°C for 10 minutes to denature enzymes. Centrifuge and filter the supernatant. Analyze glucose concentration via HPLC equipped with a refractive index detector and an Aminex HPX-87H column.

- Calculation:

Conversion Efficiency (%) = (Glucose Released (g) × 0.9) / (Initial Glucan in Biomass (g)) × 100- The factor 0.9 accounts for the water addition during hydrolysis.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Biorefining Metric Calculation Workflow

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Low Yield Decision Tree

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biomass Conversion Experiments

| Item | Function | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Cellulase Cocktail | Hydrolyzes cellulose to cellobiose and glucose. | CTec3 or Cellic CTec2 (Novozymes) |

| β-Glucosidase | Converts cellobiose to glucose, relieving end-product inhibition. | Novozyme 188 (Sigma-Aldrich) |

| Aminex HPX-87H Column | HPLC column for separation and quantification of sugars, acids, and alcohols. | Bio-Rad Laboratories |

| NREL Standard Biomass | Analytical standard for method validation and comparison. | NREL-supplied control cellulose or biomass |

| Defined Mineral Salts Medium | Provides consistent, reproducible nutrients for fermentation studies. | Adapted from ATCC or DSMZ recipes for target organism |

| Inhibitor Standards | For calibrating HPLC to detect and quantify fermentation inhibitors. | Furfural, HMF, Acetic Acid, Syringaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) |

Cutting-Edge Techniques: Advanced Pretreatment and Saccharification Strategies

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

This support center is designed to assist researchers in overcoming common experimental challenges when applying next-generation pretreatment technologies within the context of Improving biomass conversion efficiency in biorefineries. All protocols and data are curated to support reproducible, high-yield biomass deconstruction.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My selected ionic liquid (IL) is not effectively dissolving lignocellulosic biomass. What could be the issue? A: This is often due to moisture content or IL purity. Most ILs, especially imidazolium-based ones like [C2mim][OAc], are highly hygroscopic. Absorbed water (>1-2% w/w) drastically reduces dissolution capacity. Ensure proper drying of both biomass (to <10% moisture) and IL (via vacuum drying at 70-80°C for 24h). Also, verify that your IL has not undergone decomposition or impurity introduction.

Q2: After pretreatment with a Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES), the recovery of cellulose solids yields a gummy, hard-to-handle material. How can I fix this? A: The gumminess indicates incomplete removal of the DES components (e.g., choline chloride, hydrogen bond donor). Increase the washing stringency. Use a sequence of warm water (50-60°C) washes followed by a final ethanol or acetone wash to effectively remove residual DES. A solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:20 (w/v) during washing is recommended.

Q3: My steam explosion pretreatment results in excessive degradation products (furfural, HMF) that inhibit downstream fermentation. How can I minimize this? A: Degradation is highly sensitive to temperature and time. Optimize severity factor (log R₀). Consider lowering the temperature (e.g., from 210°C to 190°C) and reducing residence time (e.g., from 10 min to 5 min). Introducing a mild acid catalyst (e.g., 0.5% w/w H₂SO₄) can allow you to use a lower temperature to achieve the same pretreatment effect while reducing inhibitor formation.

Q4: I am experiencing poor enzymatic hydrolysis yields after IL pretreatment, despite high delignification. What's the potential cause? A: IL retention on cellulose, even in trace amounts, can non-competitively inhibit cellulase enzymes. Implement a more rigorous anti-solvent precipitation and washing protocol. After regenerating cellulose with an anti-solvent like water, use a mixed solvent wash (e.g., water:ethanol in 1:1 ratio) and consider a mild thermal treatment (60°C) to evaporate last traces of solvent.

Q5: My DES system solidifies at room temperature, making it difficult to handle. How can I maintain its liquid state for pretreatment? A: Many DES have eutectic points above room temperature. Maintain the DES in a liquid state by using a heated vessel or water bath set at 10-15°C above its solidification point during handling and biomass mixing. For long-term storage, store at room temperature as a solid and re-liquefy gently before use.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Biomass Pretreatment with [C2mim][OAc] Ionic Liquid

- Dry: Dry 1.0 g of milled biomass (20-80 mesh) and 20 g of [C2mim][OAc] separately at 80°C under vacuum overnight.

- Dissolve: Combine biomass and IL in a dry flask under N₂ atmosphere. Heat to 120°C with stirring (300 rpm) for 3 hours.

- Regenerate: Add 40 mL of pre-heated (80°C) deionized water as an anti-solvent with vigorous stirring to precipitate cellulose.

- Wash: Collect solids via vacuum filtration. Wash sequentially with 100 mL hot water, 50 mL ethanol, and 50 mL acetone.

- Dry: Air-dry the solid fraction overnight, then oven-dry at 45°C for 24h. Store for analysis.

Protocol 2: Lignin Extraction Using Choline Chloride:Lactic Acid DES (1:2 Molar Ratio)

- Synthesize DES: Mix choline chloride and lactic acid in a 1:2 molar ratio at 80°C with stirring until a homogeneous, colorless liquid forms (~1 hour).

- Pretreat: Add 2.0 g of dry biomass to 20 g of DES in a round-bottom flask. React at 120°C for 4 hours with magnetic stirring.

- Separate: Add 40 mL of cold water to the mixture to precipitate the cellulose-rich solid. Filter using a Büchner funnel.

- Extract Lignin: Adjust the pH of the filtered liquor (containing dissolved lignin) to ~2.0 using 1M HCl to precipitate the lignin.

- Recover: Filter the precipitated lignin, wash with acidified water (pH 2), and freeze-dry.

Protocol 3: Steam Explosion of Herbaceous Biomass (e.g., Corn Stover)

- Load: Charge 100 g of moisture-adjusted biomass (50% moisture content) into the steam explosion reactor vessel.

- Impregnate: Introduce saturated steam to rapidly bring the system to the target temperature (e.g., 190°C) and pressure (~12 bar).

- React: Maintain the set temperature for the desired residence time (e.g., 5 minutes).

- Explode: Instantaneously release the pressure by opening the ball valve, explosively discharging the biomass into a cyclone collector.

- Collect & Wash: Collect the pretreated slurry. Wash a representative sample with water to remove inhibitors for downstream enzymatic hydrolysis.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Next-Gen Pretreatment Methods on Corn Stover

| Pretreatment Method | Conditions | Solid Recovery (%) | Delignification (%) | Cellulose Digestibility (72h, %) | Key Inhibitors Formed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquid | [C2mim][OAc], 120°C, 3h | 65-70 | 70-80 | 90-95 | Low (IL residues) |

| Deep Eutectic Solvent | ChCl:LA (1:2), 120°C, 4h | 55-65 | 60-75 | 85-92 | Low (Ch, LA) |

| Steam Explosion | 190°C, 5 min, no catalyst | 80-85 | 30-40 | 70-80 | High (Furfural, HMF) |

| Steam Explosion | 190°C, 5 min, 0.5% H₂SO₄ | 75-80 | 50-60 | 85-90 | Moderate |

Table 2: Severity Factor (log R₀) in Steam Explosion and Outcomes

| Temperature (°C) | Time (min) | log R₀* | Glucose Yield (%) | Furfural Conc. (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 170 | 15 | 3.2 | 65 | 0.2 |

| 190 | 5 | 3.5 | 78 | 0.8 |

| 210 | 5 | 4.2 | 82 | 2.5 |

| 210 | 15 | 4.5 | 75 | 4.1 |

*R₀ = t * exp[(T-100)/14.75], where t is time (min), T is temperature (°C).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Pretreatment |

|---|---|

| 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([C2mim][OAc]) | Prototypical IL; disrupts lignin and hemicellulose matrix via hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions. |

| Choline Chloride | Quaternary ammonium salt; common HBA for DES formation, low-cost and biodegradable. |

| Lactic Acid | Common HBD for DES; contributes to lignin solvation and esterification reactions. |

| Antisolvents (Water, Ethanol, Acetone) | Used to regenerate dissolved cellulose from IL/DES and wash residual solvents from solids. |

| Dilute Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | Catalyst in steam explosion to enhance hemicellulose hydrolysis and reduce required severity. |

Visualizations

Biomass Pretreatment and Saccharification Workflow

Steam Explosion Severity Factor Impact

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: Our enzyme cocktail shows high activity on model substrates like Avicel but performs poorly on our specific pretreated agricultural residue. What could be the cause? A: This is a common issue indicating a mismatch between the enzyme cocktail composition and the feedstock's unique polysaccharide architecture and accessibility. Model substrates are pure and accessible, while real feedstocks have complex lignin-carbohydrate complexes, varied crystallinity, and inhibitory compounds.

- Actionable Steps:

- Analyze Feedstock Composition: Perform a detailed compositional analysis (NREL/TP-510-42618) to quantify glucan, xylan, arabinan, lignin, and acetyl content.

- Profile Inhibition: Test for enzyme inhibitors (e.g., phenolic compounds from lignin degradation, furans) using assays like the Prussian blue method for phenolics.

- Reformulate Cocktail: Based on composition, increase the ratio of hemicellulases (e.g., xylanase, β-xylosidase) for grassy biomass or add auxiliary activities (AAs) like lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs) for highly crystalline cellulose.

Q2: We observe an initial burst of sugar release that plateaus rapidly. How can we improve conversion yield and kinetics? A: A rapid plateau often suggests enzyme deactivation, product inhibition, or the depletion of easily hydrolyzable fractions, leaving recalcitrant structures.

- Actionable Steps:

- Mitigate Product Inhibition: Supplement the reaction with β-glucosidase (for cellobiose accumulation) or xylan-debranching enzymes (for xylooligomers). Consider a fed-batch or continuous product removal setup.

- Enhance Synergy: Evaluate the synergy factor between core and accessory enzymes. A lack of plateau-breaking enzymes is likely.

- Optimize Process Parameters: Measure and adjust for shear-induced deactivation, temperature gradients, or pH drift during hydrolysis.

Q3: How do we quantitatively compare the performance and cost-effectiveness of two different enzyme cocktail formulations? A: Use standardized performance metrics and compile them into a comparative table. Key metrics include: * Total Protein Loading: mg enzyme / g glucan. * Hydrolysis Yield: % of theoretical glucose/xylose yield at a given time (e.g., 72h). * Hydrolysis Time: Time to reach 80% of the maximum yield. * Synergy Factor (SF): (Activity of cocktail) / (Sum of individual enzyme activities). * Cost Contribution: Estimated enzyme cost per kg of total sugars released.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cocktail A vs. B on Pretreated Corn Stover

| Performance Metric | Cocktail A (Commercial Blend) | Cocktail B (Tailored Cocktail) | Measurement Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Protein Load | 20 mg/g glucan | 15 mg/g glucan | Bradford/Lowry assay |

| Glucose Yield (72h) | 78% theoretical | 92% theoretical | HPLC-RID (NREL/TP-510-42623) |

| Xylose Yield (72h) | 45% theoretical | 85% theoretical | HPLC-RID (NREL/TP-510-42623) |

| Synergy Factor (SF) | 1.2 | 2.1 | See Protocol 1 below |

| Time to 80% Yield | 48 hours | 36 hours | Kinetic sampling every 12h |

Q4: What is a robust experimental protocol for formulating and testing a tailored enzyme cocktail? A: Follow this systematic workflow.

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Cocktail Formulation & Synergy Testing Objective: To identify synergistic interactions between core cellulases, hemicellulases, and accessory enzymes for a specific feedstock.

- Feedstock Preparation: Mill and sieve pretreated biomass to 20-80 mesh. Determine moisture content.

- Enzyme Stock Solutions: Prepare individual enzyme stocks (e.g., endoglucanase, cellobiohydrolase, β-glucosidase, xylanase, LPMO) in appropriate buffers. Determine protein concentration.

- Experimental Design: Use a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach (e.g., mixture design) to create cocktail formulations varying the proportion of each enzyme, keeping total protein load constant.

- Hydrolysis Reaction: Conduct reactions in 96-well deep-well plates. Per well: 0.1 g biomass (dry basis), 10 mL total volume in 50 mM citrate buffer (pH 4.8), 0.02% sodium azide. Add enzyme cocktail according to DoE. Incubate at 50°C with orbital shaking (250 rpm) for 72h.

- Sampling & Analysis: Quench samples at 0, 2, 24, 48, 72h. Analyze supernatant for sugar monomers (glucose, xylose) by HPLC or suitable biosensor.

- Data Analysis: Calculate yields and synergy factors. SF = (Sugar yield from cocktail) / (Sum of sugar yields from individual enzymes assayed alone at the same total protein load).

Diagram 1: Enzyme Cocktail Optimization Workflow

Diagram 2: Synergistic Hydrolysis of Biomass

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Enzyme Cocktail Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment | Example Vendor/Product |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Enzyme Premixes | Benchmarking baseline; source of core activities for deconstruction. | Cellic CTec3, HTec3 (Novozymes); Accellerase TRIO (DuPont) |

| Monocomponent Enzymes | For constructing tailored cocktails and mechanistic studies. | Megazyme (e.g., endo-1,4-β-xylanase); Nzytech (various cellulases) |

| Lytic Polysaccharide Monooxygenase (LPMO) | Auxiliary Activity for oxidative cleavage of crystalline cellulose. | Sigma-Aldrich (AA9 family LPMO); produced recombinantly in-house |

| Model Substrates | Activity assays for specific enzyme classes. | Avicel (microcrystalline cellulose), Beechwood xylan, pNPC (para-nitrophenyl glycosides) |

| Pretreated Biomass Standards | Consistent, well-characterized feedstock for comparative studies. | NIST Reference Materials (e.g., RM 8491, pretreated corn stover) |

| HPLC Columns for Sugar Analysis | Separation and quantification of sugar monomers and oligomers. | Bio-Rad Aminex HPX-87P (for glucose/cellobiose); HPX-87H (for mixed sugars) |

| 96-Deep Well Plate System | High-throughput hydrolysis screening with necessary agitation. | Avygen or Eppendorf plates with gas-permeable seals |

| DoE Software | Statistical design of formulation experiments and data modeling. | JMP, Minitab, or R (with DoE.base package) |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: Our CBP consortium shows stalled fermentation after 24 hours, with minimal ethanol production. What could be the cause?

A: This is often due to microbial inhibition or nutrient limitation. First, check for inhibitor accumulation from pretreatment.

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Sample Prep: Centrifuge a 10 mL culture sample at 10,000 x g for 5 min. Filter the supernatant through a 0.22 µm syringe filter.

- HPLC Analysis: Analyze the filtrate via HPLC (Aminex HPX-87H column, 5 mM H₂SO₄ mobile phase, 0.6 mL/min, 50°C) for organic acids (acetic, formic, levulinic), furans (HMF, furfural), and ethanol.

- Cell Viability: Perform a live/dead stain (e.g., using SYTO 9 and propidium iodide) on the pellet and count using fluorescence microscopy.

Common Thresholds & Mitigation: If inhibitor concentrations exceed critical thresholds, consider in-situ detoxification or process adaptation.

| Inhibitor Compound | Critical Concentration Range (CBP) | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Acetic Acid | > 5.0 g/L | Increase culture buffering capacity (e.g., CaCO₃ to 20-30 g/L) or adapt consortium via serial culturing. |

| Furfural | > 1.5 g/L | Pre-condition inoculum with sub-lethal doses (0.5-1.0 g/L) for 12 hours. |

| HMF | > 3.0 g/L | As for furfural. Consider genetic engineering for enhanced reductase activity. |

Q2: How do we optimize the enzyme-to-microbe ratio in a cellulolytic bacterium (e.g., Clostridium thermocellum) co-culture with a ethanologen (e.g., Thermoanaerobacterium saccharolyticum)?

A: The optimization balances hydrolysis rate with sugar consumption to prevent catabolite repression. A detailed chemostat-based protocol is recommended.

- Experimental Protocol: Dynamic Ratio Optimization

- Setup: Use two parallel bioreactors with identical conditions (pH 6.0, 60°C, anaerobic). Maintain a constant working volume of 1L with a defined medium containing 50 g/L Avicel (cellulose model compound).

- Inoculation: Reactor A: Inoculate with a pure culture of C. thermocellum at OD600 0.1. Reactor B: Inoculate with a pre-optimized ratio (e.g., 4:1) of C. thermocellum to T. saccharolyticum.

- Operation: Run in batch mode for 12h, then switch to continuous mode at a dilution rate (D) of 0.05 h⁻¹.

- Monitoring: Sample every 4h for 48h. Measure OD600, residual cellulose (via gravimetric analysis), and extracellular metabolites (HPLC).

- Analysis: Calculate the specific cellulose consumption rate for each condition. The optimal ratio minimizes residual soluble sugars while maximizing ethanol titer.

Q3: We observe poor substrate accessibility and low sugar yields when using real lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn stover) instead of model substrates. What steps should we take?

A: This typically points to physical barriers and lignin inhibition. A pre-processing and analytics workflow is essential.

- Diagnostic & Enhancement Protocol:

- Characterization: Perform compositional analysis (NREL/TP-510-42618) on your biomass to determine lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose percentages.

- Physical Pre-treatment: Mill biomass to a particle size of < 2 mm. Consider a mild hydrothermal pretreatment (e.g., 160°C for 20 min) to enhance porosity without generating severe inhibitors.

- Additive Screening: Test the addition of non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Tween 80 at 0.1-0.5% w/v) or lignin-blocking polymers (e.g., PEG 4000) to the CBP medium to reduce enzyme non-productive binding.

- Evaluation: Run parallel 100 mL CBP batches with pre-treated vs. untreated biomass. Measure sugar release kinetics and final ethanol yield.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

| Reagent / Material | Function in CBP Experiments | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Avicel PH-101 | Microcrystalline cellulose model substrate. | Standardized, reproducible substrate for benchmarking hydrolysis performance. |

| Alkaline Peroxide Pretreated Biomass | Standardized real substrate with reduced lignin content. | Provides a consistent, more digestible real-world feedstock for comparative studies. |

| SYTO 9 / Propidium Iodide Stain | Fluorescent viability assay for microbial consortia. | Critical for monitoring population dynamics and health in mixed cultures. |

| CaCO₃ (Calcium Carbonate) | Buffering agent to counteract acidification from acetate production. | Maintains pH stability, especially vital for non-pH-regulated batch systems. |

| Tween 80 | Non-ionic surfactant. | Reduces cellulase deactivation by preventing unspecific binding to lignin. |

| Anaerobic Chamber Gas Mix | (e.g., 80% N₂, 10% CO₂, 10% H₂). | Creates and maintains strict anaerobic conditions essential for most CBP organisms. |

| Custom Defined Medium | Minimal medium with trace metals and vitamins. | Eliminates variability from complex additives, enabling precise metabolic studies. |

Visualizations

CBP Integrated Bioprocess Workflow

Inhibition Pathways in CBP

Technical Support Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: In our continuous membrane bioreactor (CMBR) for lignocellulosic hydrolysate fermentation, we observe a sudden, sustained drop in product titer. What are the primary causes?

- A: This is typically indicative of membrane fouling or biocatalyst inhibition. First, check transmembrane pressure (TMP); a steady increase confirms fouling. Common foulants are microbial polysaccharides or lignin derivatives. Implement a standardized clean-in-place (CIP) protocol (see below). If TMP is stable, assess feed composition; inhibitors like furfurals or phenolics may have accumulated, requiring pre-treatment optimization or an in-line adsorption column.

Q2: Our continuous flow enzymatic reactor shows decreased conversion efficiency over 48 hours. How can we differentiate between enzyme denaturation and flow channeling?

- A: Perform two diagnostic tests. First, measure activity of a sampled enzyme aliquot under ideal batch conditions. Second, conduct a residence time distribution (RTD) analysis using a dye tracer. Compare the data.

- Diagnostic Data Table:

| Test | Method | Indicator of Denaturation | Indicator of Channeling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batch Activity Assay | Incubate reactor sample with fresh substrate at optimal pH/Temp. | >40% activity loss vs. fresh enzyme. | <10% activity loss. |

| RTD Analysis | Pulse-inject a conservative tracer (e.g., blue dextran) at inlet, monitor at outlet. | Normal, sharp peak. | Early tracer breakthrough with long tailing. |

- Q3: When integrating an upstream continuous flow chemistry module with a downstream MBR, how do we manage mismatched flow rates and reactor residence times?

- A: Implement a surge tank or a pulsed feed system between units. Use a feedback-controlled holding tank that accumulates the upstream output and feeds the MBR at its optimal rate. Equip the tank with an inert gas overlay (e.g., N₂) to prevent unwanted oxidation or microbial contamination during hold-up.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standardized Clean-In-Place (CIP) for Fouled Membrane Bioreactors

- Objective: Restore membrane flux after fouling during continuous fermentation.

- Materials: Peristaltic pump, CIP reservoir, 0.1M NaOH solution, 200ppm sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution, DI water, pH meter.

- Procedure:

- Drain the bioreactor and rinse the membrane module with 2 volumes of DI water at 25°C.

- Recirculate 0.1M NaOH at 40°C for 60 minutes at a cross-flow velocity of 1 m/s.

- Flush with DI water until rinse pH is neutral.

- Recirculate 200ppm NaOCl solution at 25°C for 30 minutes.

- Perform a final DI water flush (3 volumes).

- Conduct a water flux test at standard TMP; recovery should be >90% of initial clean water flux.

Protocol 2: Residence Time Distribution (RTD) Analysis for Continuous Flow Reactors

- Objective: Characterize flow behavior and identify dead zones or channeling.

- Materials: Continuous flow reactor system, tracer (e.g., 0.1% w/v Blue Dextran 2000 or NaCl), UV-Vis spectrophotometer or conductivity probe, data logger.

- Procedure:

- Establish steady-state operation at desired flow rate (Q).

- Rapidly pulse a small volume of tracer (Vtracer < 0.01*reactor volume) into the inlet stream.

- Continuously measure tracer concentration (C(t)) at the outlet.

- Normalize data to obtain the E(t) curve: E(t) = C(t) / ∫₀∞ C(t)dt.

- Calculate mean residence time: τ = ∫₀∞ t*E(t)dt. Compare τ to theoretical residence time (Vreactor / Q).

Visualizations

Troubleshooting Logic for CMBR Performance Drop

Integrated Continuous System with Buffer Control

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Process Intensification Research |

|---|---|

| Hollow Fiber Membrane Modules (PES, PVDF) | Provides high surface area for cell retention or product separation in MBRs, enabling high cell density and continuous operation. |

| Immobilized Enzyme Cartridges | Packed-bed reactors containing catalysts covalently bound to solid supports for continuous flow biocatalysis, enhancing stability and reusability. |

| Static Mixers | In-line mixing elements that ensure rapid, homogeneous mixing of substrates in continuous flow tubular reactors, improving mass/heat transfer. |

| In-line FTIR / HPLC Probes | Provides real-time monitoring of reaction conversion or product formation, enabling immediate feedback and control of continuous processes. |

| Gas-Liquid Membrane Contactors | Modules for efficient, continuous O₂ supply or CO₂ stripping in bioreactors without forming bubbles, preventing foam and improving mass transfer. |

| Cross-flow Filtration Cells | Lab-scale systems for simulating and optimizing membrane filtration conditions (shear, TMP) before scaling to full MBRs. |

Overcoming Operational Hurdles: Mitigating Inhibitors and Enhancing Catalyst Life

Identification and Detoxification of Microbial Growth Inhibitors (e.g., Furans, Phenolics).

Technical Support Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting

Q1: My fermentation yields are low after pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. I suspect microbial growth inhibitors are the cause. How do I confirm this and identify the main culprits? A: First, perform chemical analysis of your hydrolysate. Use High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to quantify common inhibitors like furfural, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), and phenolic compounds (e.g., vanillin, syringaldehyde). Compare concentrations to known inhibitory thresholds (see Table 1). For biological confirmation, conduct a microbial inhibition assay: serially dilute your hydrolysate in a defined medium and compare the growth (OD600) of your fermentative microorganism (e.g., Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Escherichia coli) against a control with pure sugars. A dose-dependent growth lag or decline confirms inhibitor presence.

Q2: I've identified high concentrations of furanic compounds (furfural, HMF). What are the most effective detoxification methods? A: The optimal method depends on your process scale and downstream requirements.

- Physical: Vacuum evaporation effectively removes volatile furans.

- Chemical: Overliming (raising pH to 10-12 with Ca(OH)₂, then re-neutralizing) precipitates inhibitors and degrades some furans. Adsorption using activated carbon (10-50 g/L) is highly effective for a broad inhibitor range.

- Biological: Employ an in-situ detoxification strategy using inhibitor-tolerant microbial strains or pre-culturing cells to induce stress-response enzymes like alcohol dehydrogenases (ADHs) that reduce furans to less inhibitory alcohols.

Q3: Phenolics are persistent in my stream. Which detoxification protocol is most suitable for phenolic compounds? A: Phenolics, being less volatile, are best removed by adsorption or enzymatic treatment.

- Adsorption: Use polymeric resins (e.g., XAD-4, Amberlite) or activated carbon. These have high affinity for aromatic rings. Note that resins may also adsorb sugars; optimize contact time and load to minimize loss.

- Enzymatic: Laccase and peroxidase enzymes from white-rot fungi polymerize phenolics, facilitating their precipitation. This is a specific, mild method ideal for sensitive processes.

Q4: My detoxification step is causing significant sugar loss. How can I mitigate this? A: Sugar loss is common with adsorption and overliming. To mitigate:

- Optimize Load: For adsorption, determine the minimum resin/charcoal amount needed for effective detoxification by creating adsorption isotherms.

- Sequential Elution: After adsorption, recover sugars by eluting the column with water or dilute acid before eluting the inhibitors with an organic solvent like ethanol.

- Alternative Methods: Consider membrane-based nanofiltration, which can separate low-molecular-weight inhibitors from sugars based on size and charge, often with higher sugar retention.

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantification of Inhibitors via HPLC

- Sample Prep: Filter hydrolysate through a 0.22 µm syringe filter.

- Column: Rezex ROA-Organic Acid H+ (8%) or equivalent.

- Mobile Phase: 5 mM H₂SO₄, isocratic.

- Flow Rate: 0.6 mL/min.

- Temperature: 60°C.

- Detection: Refractive Index (RI) for sugars, Diode Array Detector (DAD) at 210 nm (acids), 276 nm (furans), and 280 nm (phenolics).

- Calibration: Use external standards for quantitation.

Protocol 2: Microbial Inhibition Assay

- Prepare a defined mineral medium with pure glucose/xylose at your target concentration.

- Prepare test media by mixing the defined medium with filtered hydrolysate at ratios of 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% (v/v).

- Inoculate all media with a standardized inoculum (e.g., OD600 = 0.1) of your microbe from a fresh pre-culture.

- Incubate under standard conditions, monitoring OD600 every 2-4 hours.

- Calculate key parameters: Maximum growth rate (µmax), lag phase duration, and final biomass yield. Compare to the pure sugar control.

Protocol 3: Overliming Detoxification

- Measure the pH of the hydrolysate.

- Slowly add Ca(OH)₂ slurry with vigorous stirring until pH reaches 10.0.

- Maintain the pH at 10.0 (±0.1) for 30-60 minutes at 30-60°C with continuous stirring.

- Re-neutralize to pH 5.5-6.0 using concentrated H₂SO₄ or H₃PO₄.

- Allow precipitated gypsum (CaSO₄) to settle overnight at 4°C, then separate by centrifugation (10,000 x g, 15 min) and filter (0.45 µm).

- Analyze the supernatant for inhibitor removal and sugar recovery (HPLC).

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Microbial Growth Inhibitors in Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates

| Inhibitor Class | Example Compounds | Typical Source | Inhibitory Threshold* | Primary Detox Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Furans | Furfural, 5-HMF | Acid hydrolysis of pentoses/hexoses | 1-2 g/L (furfural) | Adsorption, Reduction |

| Weak Acids | Acetic, Formic Acid | Hemicellulose deacetylation | 5-10 g/L (acetate) | Extraction, pH Control |

| Phenolics | Vanillin, Syringaldehyde | Lignin degradation | 1-2 g/L (total) | Adsorption, Laccase |

| Aldehydes | Hydroxybenzaldehyde | Lignin fragmentation | Varies | Overliming, Reduction |

*Thresholds are microbe-dependent; values shown are for common fermentative yeasts.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Amberlite XAD-4 Resin | Hydrophobic polymeric adsorbent for removing phenolics and furans from hydrolysates. |

| Laccase from Trametes versicolor | Enzyme used to catalyze the oxidative polymerization of phenolic inhibitors. |

| Furfural & HMF Analytical Standards | Essential for accurate calibration and quantification in HPLC analysis. |

| Ca(OH)₂ (Slaked Lime) | Reagent for overliming detoxification; raises pH to precipitate inhibitors. |

| Activated Carbon (Powdered) | High-surface-area adsorbent for broad-spectrum inhibitor removal. |

| Yeast Extract Peptone Dextrose (YPD) | Rich medium for cultivating and maintaining inhibitor-tolerant S. cerevisiae strains. |

Visualizations

Workflow for Inhibitor Management in Biorefining

Microbial Enzymatic Detoxification Pathway

Strategies to Minimize Enzyme Deactivation and Product Inhibition

Technical Support Center

This support center provides troubleshooting guidance for common challenges in enzymatic biomass conversion, framed within the research context of Improving Biomass Conversion Efficiency in Biorefineries. The following FAQs address specific experimental issues related to enzyme stability and inhibition.

FAQ & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My cellulase activity drops precipitously after 2 hours of lignocellulosic hydrolysis. What are the primary causes and corrective strategies?

A: Rapid deactivation is often due to shear forces, thermal denaturation, or inhibitors from biomass pretreatment. Implement these steps:

- Check Pretreatment: Ensure thorough washing of solid biomass fractions to remove residual acids, furans (HMF, furfural), and phenolics. Quantify inhibitor levels.

- Modify Reactor Conditions: Reduce agitation speed to minimize shear. For continuous systems, verify feed consistency to prevent cavitation.

- Apply Stabilizers: Introduce non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Tween-80) or proteins like BSA. See Protocol 1.

Q2: I suspect strong product inhibition (e.g., by glucose or cellobiose) is limiting my saccharification yield. How can I confirm and mitigate this?

A: Product inhibition is common in hydrolytic enzymes. Conduct a dose-response assay with added product.

- Diagnostic Test: Run standard hydrolysis with spiked concentrations of the suspected inhibitor (e.g., 0-50 mM glucose). A sharp activity decline confirms inhibition.

- Mitigation Strategies: Employ Simultaneous Saccharification and Fermentation (SSF) where microbes immediately consume inhibitory sugars. Alternatively, use enzyme blends with enhanced product tolerance or implement in-situ product removal techniques.

Q3: What are the best practical methods to stabilize enzyme cocktails during long-term (>24h) bioprocessing?

A: Long-term stabilization requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Immobilization: Covalently bind enzymes to solid supports or use carrier-free cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs). This enhances stability and allows reuse. See Protocol 2.

- Process Engineering: Operate in fed-batch mode to maintain low substrate viscosity. Implement continuous reactors with enzyme recycle modules (e.g., ultrafiltration membranes).

- Medium Engineering: Optimize pH buffers for long-term hold. Include polyols (e.g., glycerol, sorbitol) at 10-20% w/v as stabilizing agents.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating Stabilizers for Enzyme Thermostability Objective: To test the protective effect of additives on enzyme half-life at process temperature.

- Prepare reaction buffer (e.g., 50 mM citrate, pH 4.8) with and without the stabilizer (e.g., 0.1% Tween-80, 1 mg/mL BSA, or 10% glycerol).

- Add a standardized amount of enzyme (e.g., cellulase cocktail). Incubate at the target process temperature (e.g., 50°C) in a thermal cycler or water bath.

- At defined time intervals (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24 h), withdraw aliquots and immediately place on ice.

- Measure residual activity using a standard assay (e.g., filter paper assay for cellulase).

- Calculate the half-life and deactivation rate constant from the activity decay profile.

Protocol 2: Preparation of Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) Objective: To immobilize enzymes via precipitation and cross-linking for enhanced stability and reusability.

- In a stirred vessel, bring the enzyme solution to 80% saturation with a precipitant (e.g., ammonium sulfate or cold acetone).

- Keep at 4°C for 1 hour to allow aggregate formation. Centrifuge (10,000 x g, 10 min) to collect aggregates.

- Re-suspend the aggregates in a small volume of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0-8.0).

- Add a cross-linker (e.g., glutaraldehyde to 50 mM final concentration). Stir gently for 2 hours at 4°C.

- Quench the reaction by adding excess lysine or glycine. Wash the CLEAs 3x with buffer. Store at 4°C in buffer.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Efficacy of Common Stabilizing Agents on Cellulase Half-life at 50°C

| Stabilizing Agent | Concentration | Half-life (h) | Relative Activity (%) at 24h | Primary Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (No additive) | - | 4.2 | 12 | Baseline |

| Glycerol | 10% (v/v) | 9.8 | 38 | Water activity reduction, conformational rigidity |

| Tween-80 | 0.1% (w/v) | 15.3 | 65 | Surfactant, prevents interfacial denaturation |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | 1 mg/mL | 11.5 | 52 | Competitive target for phenolics, surface protector |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG 4000) | 5% (w/v) | 8.1 | 30 | Crowding agent, stabilizes hydration shell |

Table 2: Impact of Product Inhibition on Hydrolytic Enzyme Kinetics

| Enzyme | Inhibiting Product | KI (mM)* | % Activity Reduction at 20mM Inhibitor | Recommended Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Glucosidase | Glucose | 5.8 | 78% | Use glucose-tolerant mutants or SSF |

| Cellobiohydrolase I | Cellobiose | 3.2 | 86% | Augment with excess β-glucosidase |

| Xylanase | Xylose | 45.0 | 30% | Generally low impact; fed-batch operation |

| KI = Inhibition Constant; Lower value indicates stronger inhibition. |

Visualizations

Title: Enzyme Deactivation Causes, Effects, and Solutions

Title: SSF Overcomes Product Inhibition Feedback Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Non-ionic Surfactants (Tween-80, PEG) | Reduces interfacial denaturation; prevents unproductive enzyme binding to lignin. | Use high-purity grades. Optimal concentration is enzyme-specific (typically 0.05-0.2%). |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Acts as a competitive adsorbent for hydrophobic inhibitors (e.g., phenolics); protects enzyme surface. | Can interfere with protein assays; use protease-free grade. |

| Polyols (Glycerol, Sorbitol) | Stabilizes enzyme conformation by altering solvent water activity; enhances thermostability. | High viscosity at >20% may impede mixing and mass transfer. |

| Cross-linkers (Glutaraldehyde) | Forms covalent bonds in enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) or between enzyme and support for immobilization. | Concentration and time must be optimized to avoid complete activity loss. |

| Ultrafiltration Membranes | Allows for continuous reactor operation with enzyme recycle and simultaneous product removal. | Select molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) carefully to retain enzyme while permeating product. |

| Immobilization Supports (Chitosan, Eupergit C, Silica) | Provides a solid matrix for enzyme attachment, facilitating reuse and improving stability. | Binding chemistry must not block active site; support should be inert and porous. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During enzymatic hydrolysis at high solids loading (>15% w/w), we observe severe mixing issues and a dramatic drop in conversion yield. What are the primary causes and solutions? A: This is a classic symptom of insufficient mass and heat transfer, coupled with increased inhibitor concentration. The high viscosity of the slurry limits enzyme accessibility.

- Solutions: Implement a fed-batch strategy where solids are added progressively. Incorporate a pre-hydrolysis step at lower solids. Use process additives or surfactants (e.g., Tween 80) to reduce viscosity and prevent non-productive enzyme binding. Ensure your impeller design is suitable for high-solids mixing (e.g., helical ribbon).

Q2: How does a small shift in pH outside the optimal range (e.g., from 5.0 to 4.5 or 5.5) critically impact cellulase enzyme cocktails? A: pH affects enzyme activity, stability, and synergy. A shift can denature key enzymes (e.g., β-glucosidase is often more sensitive than endoglucanase), alter substrate-enzyme binding, and change the ionization state of substrate functional groups.

- Troubleshooting: Always perform a pH profile experiment for your specific substrate-enzyme system. Use a robust buffer system (e.g., citrate) with adequate capacity. Continuously monitor and control pH throughout the reaction, as hydrolysis can release organic acids.

Q3: When scaling up a pretreatment process (e.g., dilute acid), temperature gradients lead to inconsistent sugar recovery. How can this be mitigated? A: Inconsistent temperature causes varying degrees of hemicellulose solubilization and inhibitor generation (furfural, HMF).

- Protocol: Ensure rapid heating to the target temperature. Validate reactor thermal uniformity using multiple calibrated sensors. For steam-based pretreatments, use live steam injection with vigorous mixing. Consider a smaller reactor aspect ratio (height/diameter) to improve thermal homogeneity.

Q4: We see unpredictable fermentation inhibition after optimizing pretreatment temperature and pH. Are these parameters linked to inhibitor formation? A: Absolutely. Temperature and pH are the two most critical drivers for generation of microbial inhibitors during pretreatment.

- Guide: Higher temperatures and lower (acidic) pH synergistically increase the degradation of pentoses (to furfural) and hexoses (to HMF). A post-pretreatment conditioning step (overliming, activated charcoal adsorption, or enzymatic detoxification) is often necessary. The optimal severity (a combined function of T, t, pH) must balance sugar release with inhibitor formation.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Impact of pH and Temperature on Cellulase Activity (Standard Avicel Assay)

| pH | Temperature (°C) | Relative Activity (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.5 | 50 | 85 | β-glucosidase activity typically reduced |

| 5.0 | 50 | 100 (Optimal) | Standard benchmark condition |

| 5.5 | 50 | 92 | Reduced endoglucanase binding |

| 5.0 | 45 | 75 | Slower reaction kinetics |

| 5.0 | 55 | 80 | Risk of rapid thermal denaturation |

Table 2: Sugar Yield vs. Solids Loading in Hydrolysis (72h)

| Solids Loading (% w/w) | Initial Glucose (g/L) | Final Glucose (g/L) | Conversion Yield (%) | Observed Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5% | 5.5 | 52.1 | 95.2 | None |

| 10% | 11.0 | 98.8 | 90.1 | Mild mixing |

| 15% | 16.5 | 132.0 | 80.0 | High viscosity, heat transfer |

| 20% | 22.0 | 149.6 | 68.0 | Severe product inhibition, mixing failure |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Optimal pH-Temperature Profile for Hydrolysis

- Prepare Substrate: Use a standardized substrate (e.g., 1% w/w Avicel PH-101 or pre-treated biomass) in 50mM buffer series: citrate (pH 4.0-5.5), phosphate (pH 6.0-7.0).

- Set Up Reactions: In parallel 2mL microreaction tubes, add 900μL buffered substrate. Pre-incubate at target temperatures (e.g., 45, 50, 55°C) in a thermomixer.

- Initiate Hydrolysis: Add 100μL of a standardized cellulase cocktail (e.g., 15 FPU/g substrate). Mix thoroughly.

- Sample & Analyze: Withdraw 100μL aliquots at 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48h. Immediately heat-inactivate at 95°C for 10 min. Centrifuge and analyze supernatants for reducing sugars via DNS or HPLC.

- Calculate: Plot reaction rate (glucose release per hour) against pH and temperature to identify the optimum.

Protocol 2: High-Solids Hydrolysis with Fed-Batch Operation

- Initial Charge: Load a high-shear mixer reactor with 10% (w/w) total solids of pre-treated biomass in appropriate buffer and enzyme (50% of total dose). Start mixing.

- Feeding Schedule: At 6, 12, and 24h, add a concentrated paste of pre-treated biomass mixed with the remaining enzyme, to increase total solids by 5% increments to a final 25%.

- Monitoring: Continuously monitor torque/power draw. Sample periodically, dilute samples immediately 10-fold to stop reaction, and analyze for sugars and inhibitors.

- Control: Run a parallel batch mode at 25% solids as a problematic control.

Visualizations

Title: High-Solids Hydrolysis Workflow

Title: pH & Temp Trade-off in Pretreatment

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Parameter Optimization

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Citrate-Phosphate Buffer (50-100mM) | Maintains precise pH control during hydrolysis; citrate can chelate metals that inhibit enzymes. |

| Cellulase Cocktail (e.g., CTec2, HTec2) | Commercial enzyme blend containing cellulases, hemicellulases, and β-glucosidase for complete biomass deconstruction. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) 4000 / Tween 80 | Surfactant additives that reduce non-productive enzyme binding to lignin, improving yield at high solids. |

| Sodium Azide (0.02% w/v) | Biocide added to hydrolysis assays to prevent microbial consumption of sugars during long experiments. |

| Enzymatic Detoxification Cocktail (e.g., laccase, peroxidase) | Used post-pretreatment to degrade phenolic inhibitors, mitigating fermentation toxicity. |

| Glucose Assay Kit (Glucose Oxidase-POD) | For specific, accurate measurement of glucose in complex hydrolysates, avoiding interference from other sugars. |

| Inhibitor Standards (Furfural, HMF, Acetic Acid) | HPLC standards essential for quantifying microbial inhibitors generated during pretreatment. |

AI and Machine Learning for Real-Time Process Control and Predictive Modeling

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting for Biomass Conversion Research

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My real-time sensor data stream for monitoring enzymatic hydrolysis is noisy, causing my ML model for viscosity prediction to perform poorly. How can I improve data quality? A: Noisy data from inline rheometers or NIR probes is common. Implement a two-step preprocessing pipeline in your real-time application.

- Anomaly Filtering: Use an unsupervised Isolation Forest algorithm to identify and tag spikes or dropouts caused by equipment bubbles or transient blockages.

- Smoothing: Apply a real-time Savitzky-Golay filter (window length=7, polynomial order=2) to smooth high-frequency noise while preserving the true signal trend. This can be deployed within your data ingestion layer (e.g., using Python's

scipy.signal.savgol_filteron a rolling window).

Q2: When training an LSTM model to predict inhibitor (furfural, HMF) formation in pretreatment, my model validation loss plateaus and fails to generalize to new biomass feedstocks. What should I check? A: This indicates potential overfitting or insufficient feature diversity.

- Action 1: Feature Expansion. Ensure your training set includes engineered features beyond raw sensor data. For pretreatment (e.g., steam explosion), key features are:

Feature Category Example Features Rationale Primary Sensor Temperature, Pressure, Time Direct process parameters. Biomass Property Lignin Content (% dry basis), Particle Size Distribution Critical for reaction kinetics. Derived Severity Factor (Log R₀), Heating Rate Composite metrics capturing process intensity. - Action 2: Regularization. Increase dropout rate (e.g., to 0.3) within LSTM layers and implement L2 weight regularization (lambda=0.001). Augment your dataset with synthetically generated samples for rare feedstock types using SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique).

Q3: My reinforcement learning (RL) agent for continuous cellulase dosing control converges on a suboptimal policy, leading to high enzyme costs. How can I improve the training? A: RL in bioreactors faces reward sparsity and high-dimensional state spaces.

- Protocol: Reward Shaping.

- Define Sparse Primary Reward:

R_primary = +100if sugar yield > target threshold at batch end; else0. - Shape with Dense Secondary Rewards: Add incremental rewards per control interval:

R_step = (ΔSugar_Yield * α) - (Enzyme_Used * β). Tune α and β to balance yield and cost. - State Normalization: Normalize all state inputs (e.g., pH, dissolved O₂, sugar concentration) to a zero mean and unit variance. This stabilizes gradient updates.

- Use a More Advanced Algorithm: Switch from basic DQN to Soft Actor-Critic (SAC), which is more sample-efficient and robust for continuous action spaces like dosing rates.

- Define Sparse Primary Reward:

Q4: The SHAP analysis for my predictive yield model is computationally expensive and cannot be run in real-time. Is there a faster alternative for model interpretability? A: For real-time interpretability, use LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) for individual predictions or switch to an inherently interpretable model like Gradient Boosting with Tree SHAP (which is faster than kernel SHAP for tree models). For a deployed deep learning model, consider training a simpler, surrogate "explainer model" on the inputs and outputs of your main model to approximate feature importance at high speed.

Q5: How do I validate a digital twin for a continuous fermentation process? A: Follow a structured validation protocol:

- Steady-State Validation: Run the physical bioreactor at a fixed setpoint until steady state (e.g., 3 residence times). Compare key digital twin predictions against physical sensor averages.