Bioenergy Performance and Innovation: A 2025 Assessment of Efficiency, Challenges, and Future Pathways

This article provides a comprehensive techno-economic performance assessment of bioenergy innovation and efficiency, tailored for researchers and scientists in energy development.

Bioenergy Performance and Innovation: A 2025 Assessment of Efficiency, Challenges, and Future Pathways

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive techno-economic performance assessment of bioenergy innovation and efficiency, tailored for researchers and scientists in energy development. It explores the current global status and foundational role of bioenergy in the renewable landscape, delves into advanced methodological frameworks for system optimization and application, analyzes prevalent challenges and optimization strategies for scaling production, and offers a validation of progress through comparative analysis of technologies and regional benchmarks. Synthesizing the latest data and research from 2024-2025, this review aims to inform strategic R&D and investment decisions to overcome existing hurdles and fully realize bioenergy's potential in the global energy transition.

The Foundational Role of Bioenergy: Global Status and Innovation Drivers in 2025

As global economies strive to meet climate targets and transition toward sustainable energy systems, understanding the precise contribution of various renewable technologies becomes paramount. Among these technologies, bioenergy—derived from organic materials such as plants, agricultural residues, and waste—represents a critical and versatile component of the renewable energy landscape. Its ability to provide dispatchable power, heat, and liquid fuels for hard-to-decarbonize sectors like aviation and shipping distinguishes it from variable renewables such as solar and wind. This guide provides a performance assessment of bioenergy, objectively comparing its current footprint and innovative pathways against other renewable alternatives. Framed within a broader thesis on bioenergy innovation and efficiency, this analysis synthesizes the most current global data and research trends to serve researchers, scientists, and technology developers engaged in the advanced bioeconomy.

Bioenergy constitutes a significant portion of the global renewable energy mix, characterized by its diverse applications across power, heat, and transport sectors. Current statistics reveal its foundational role and trajectory for growth.

- Overall Energy Supply: In 2022, modern bioenergy accounted for 5.8% of global Total Final Energy Consumption (TFEC), a increase from 5.7% in 2021 [1]. This underscores its status as a major modern renewable source, beyond traditional biomass use.

- Electricity Generation (Biopower): Global biopower generation reached a new peak in 2024, with capacity hitting 150.8 Gigawatts (GW) after a record annual increase of 4.6 GW [1]. In 2024, bioenergy electricity generation was 698 Terawatt-hours (TWh), marking a 3% year-on-year growth [2].

- Transportation Biofuels: Liquid biofuels are the dominant renewable energy source in transport, representing approximately 90% of renewable energy in that sector and about 4% of total transport energy use [2]. Production in 2023 reached 175.2 billion litres, a 7% increase from the previous year [1].

- Heat Sector (Bioheat): Bioenergy remains the cornerstone of renewable heat, contributing to 73% of global renewable heat production [2]. Solid bioenergy made up 8.3% of global heat consumption in 2023 [1].

Table 1: Global Bioenergy Key Statistics (2023-2024)

| Metric | 2023-2024 Value | Trend & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Share of Total Final Energy Consumption | 5.8% (2022) [1] | Steady growth from 5.7% in 2021 [1]. |

| Global Biopower Capacity | 150.8 GW (2024) [1] | Record annual increase of 4.6 GW in 2024 [1]. |

| Global Biopower Generation | 698 TWh (2024) [2] | 3% growth year-on-year [2]. |

| Liquid Biofuel Production | 175.2 billion litres (2023) [1] | 7% annual increase; 90% of renewable transport energy [1] [2]. |

| Share of Global Renewable Heat | 73% [2] | Dominant renewable source for heat applications [2]. |

| Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) Production | 1.8 billion litres (2024) [1] | 200% increase from 2023; meets ~0.53% of aviation fuel demand [1]. |

The geographical distribution of bioenergy development is uneven, reflecting regional resource availability and policy support. Asia has emerged as the fastest-growing region, with China alone accounting for 30% of global bioelectricity output and nearly half of Asia's bioheat production [2]. China's biopower capacity grew at an annual rate of 4% in 2024, while Japan's capacity reached 6 GW, doubling since 2019 [1]. Europe remains a leader in bioheat, producing 75% of the global output, with countries like France expanding biopower capacity by 60% in 2024 [1] [2]. In the Americas, the United States is a top producer of bioelectricity and ethanol, while Brazil is a global leader in biodiesel and ethanol, leveraging its extensive biomass resources [1] [3].

Comparative Performance Analysis Against Other Renewables

Bioenergy's performance profile is distinct from other renewable energy sources. Its value proposition lies in its versatility and reliability, though it faces different challenges regarding cost, scalability, and environmental impact.

Table 2: Bioenergy Performance Comparison with Other Renewable Energy Sources

| Feature | Bioenergy | Solar PV | Wind Power | Hydropower |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dispatchability | High (Provides on-demand power) [4] | Low (Intermittent) [5] | Low (Intermittent) [5] | Medium (Often dispatchable) |

| Energy Carrier Output | Electricity, heat, liquid & gaseous fuels [5] | Electricity only [5] | Electricity only [5] | Electricity primarily |

| Technology Maturity | Mature for combustion/gasification; R&D ongoing for advanced biofuels [3] | Mature and rapidly evolving [5] | Mature [5] | Very Mature |

| Land Use Considerations | High (Feedstock production) [6] [5] | Low to Medium [5] | Low [5] | High (for reservoirs) |

| Key Challenge | Feedstock supply chain & cost competition with fossils [6] [3] | Intermittency & grid integration [5] | Intermittency & grid integration [5] | Geographic & environmental constraints |

| Carbon Management | Enables BECCS for negative emissions [4] | Zero operational emissions | Zero operational emissions | Zero operational emissions |

A critical performance advantage of bioenergy is its role in providing grid reliability. As energy systems become increasingly dependent on variable solar and wind, dispatchable bioelectricity can cover around 1% of total electricity generation to strengthen supply reliability, particularly during periods of low VRE (Variable Renewable Energy) output [4]. Furthermore, biomass can be combined with carbon capture technologies to create Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), generating negative emissions—a feature not available to solar, wind, or hydropower [4]. This makes biomass a unique source of renewable carbon, vital for producing sustainable aviation fuel, plastics, and chemicals where direct electrification is challenging [4].

Innovative Pathways and Experimental Focus in Bioenergy Research

Research and development are focused on overcoming key challenges in bioenergy, particularly improving the efficiency of conversion processes and expanding the sustainable feedstock base.

Biomass Conversion Pathways to Useful Energy

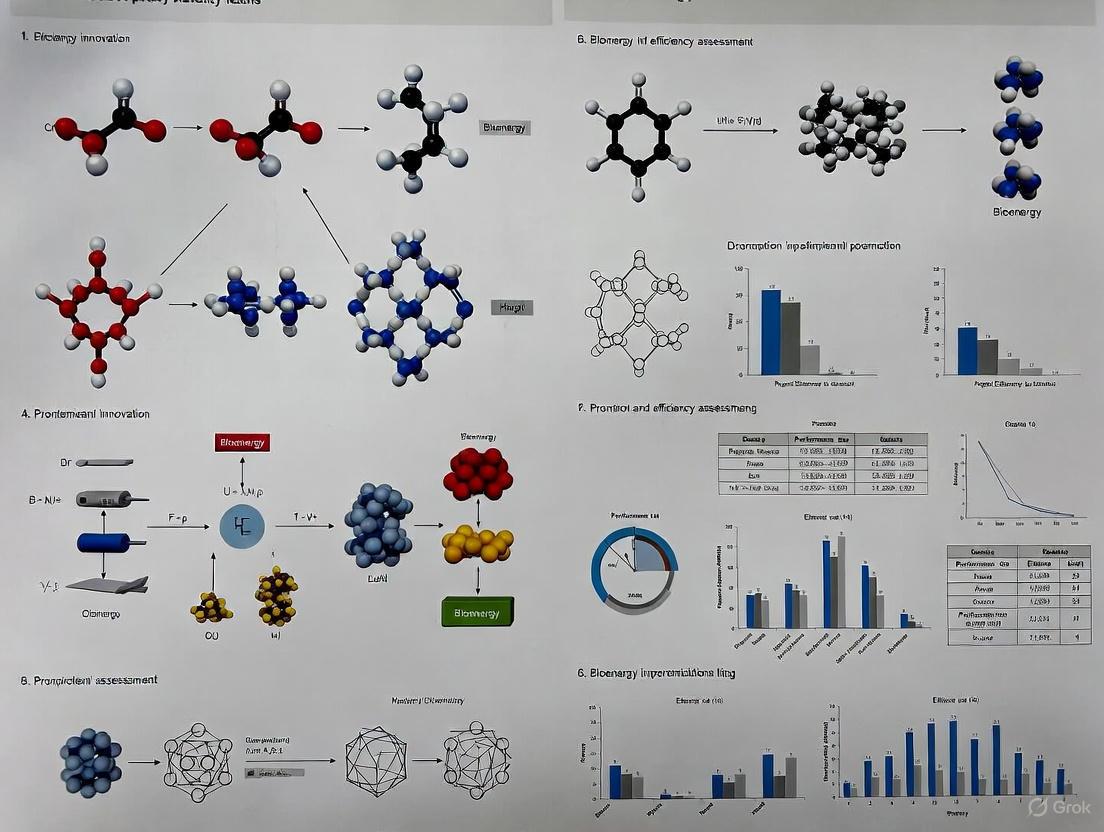

Biomass can be converted into various energy forms and products through multiple technological pathways, each with its own operational principles and outputs. The following diagram outlines the primary conversion routes.

Experimental Protocol: Investigating Microbial Toxicity in Advanced Biofuel Fermentation

A significant research frontier involves overcoming biological inefficiencies in biochemical conversion. A key challenge in fermentative production of advanced biofuels like butanol is that the alcohol product is toxic to the production microbes, self-limiting the yield [7]. The following workflow details a protocol from a recent investigation into this phenomenon.

Title: Biofuel Toxicity Analysis Workflow

Objective: To elucidate the biophysical mechanism by which bio-derived butanol induces toxicity in Clostridium strains during fermentation, thereby identifying potential targets for strain engineering to improve yield and efficiency [7].

Methodology Details:

- Fermentation Setup: Cultivate Clostridium strains in a bioreactor with a standardized lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysate as the carbon source under anaerobic conditions [7].

- Process Monitoring: Track butanol production and microbial growth kinetics over 72 hours. Collect samples at defined intervals (e.g., every 12 hours) for subsequent analysis.

- Neutron Scattering Analysis: Utilize small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) at a national laboratory facility (e.g., Oak Ridge National Laboratory). This technique probes the structural changes in the microbial cell membranes and organelles at a nanoscale resolution in response to accumulating butanol, without damaging the cells [7].

- Computational Simulation: Perform all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Model the interaction of butanol molecules with a simulated bacterial lipid bilayer to understand the molecular-level disruptive effects on membrane integrity and protein function [7].

- Data Integration: Correlate the physical structural data from SANS with the molecular interaction data from MD simulations and the physiological data from fermentation. This triangulation validates the hypothesis of membrane disruption as a primary toxicity mechanism.

Expected Outcome: A validated biophysical model demonstrating that butanol integration into the cell membrane causes loss of integrity and function, thereby providing a concrete target for genetic modification to develop more robust microbial production strains [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Advanced Biofuel Fermentation Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Biofuel Production

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Clostridium Strains | Model fermentative microorganisms (e.g., C. acetobutylicum) known for the Acetone-Butanol-Ethanol (ABE) fermentation pathway. |

| Lignocellulosic Hydrolysate | The pretreated and enzymatically digested feedstock from agricultural residues (e.g., corn stover, wheat straw), providing fermentable sugars (C5 and C6). |

| Anaerobic Growth Media | A chemically defined or complex broth (e.g., Reinforced Clostridial Medium) designed to support robust microbial growth in the absence of oxygen. |

| Small-Angle Neutron Scattering (SANS) Instrument | A facility-scale instrument used to probe the nanoscale structure of microbial cell membranes in situ under the influence of biofuel toxins [7]. |

| Deuterated Solvents | Used in SANS to manipulate the scattering contrast, allowing for clear resolution of specific biological components within the complex cellular milieu. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Software suites (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD) used to simulate and analyze the dynamic interactions between butanol molecules and lipid bilayers at an atomic level [7]. |

Discussion and Future Research Directions

The data confirms that bioenergy is an established, significant contributor to the global renewable energy mix, with particular dominance in heat and renewable transport fuels. Its unique value proposition lies in its versatility and dispatchability. However, for bioenergy to expand its footprint sustainably, innovation must focus on overcoming feedstock mobilization challenges and improving process efficiencies [6] [3].

Future research should prioritize:

- Advanced Feedstocks: Developing high-yield, low-input energy crops and optimizing the supply chain logistics for agricultural and forestry residues to ensure sustainable and economical feedstock supply [6] [8].

- Circular Bioeconomy Integration: Embedding bioenergy within broader waste management and industrial symbiosis strategies to maximize resource efficiency and minimize environmental impact, as outlined in circular economy principles [5].

- Carbon-Negative Systems: Accelerating the commercialization of BECCS and BECCU technologies. As studies indicate, the provision of biogenic carbon for negative emissions often has a higher system value than the energy provision alone, making this a critical research avenue for achieving net-zero targets [4].

- Overcoming Biological Limits: As exemplified by the experimental protocol, leveraging advanced biophysical tools and synthetic biology to engineer more efficient and robust microbial systems for biofuel production is essential for breaking through current yield ceilings [7].

In conclusion, while bioenergy already plays a substantial role, its future growth and optimization depend on continued research and development across the entire value chain—from sustainable feedstock production to efficient conversion into power, heat, and advanced biofuels. This will solidify its indispensable role in a fully decarbonized, resilient, and sustainable global energy system.

Performance Comparison of Bioenergy Sectors

The bioenergy landscape is characterized by distinct growth trajectories and technological maturity across its key sectors. The table below provides a comparative performance assessment of liquid biofuels, biopower, and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) based on current market data and research trends.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Assessment of Key Bioenergy Sectors

| Performance Metric | Liquid Biofuels | Biopower | Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size & Stature | Market valued at USD 95.07 billion (2025); Global production: 175.2B liters (2023) [1] [9] | Global capacity: 150.8 GW (2024); 3% of global electricity generation [1] | Market size: USD 2.06 billion (2025); Production: 1.8B liters (2024) [1] [10] |

| Growth Rate (CAGR/Recent) | CAGR: 6.6% (2025-2032 forecast) [9] | Record capacity growth of 4.6 GW in 2024 [1] | Exponential CAGR of 65.5% (2025-2030 forecast) [10] |

| Key Growth Drivers | Transportation fuel blending mandates (e.g., Brazil B35, E20); Policy support (RFS, RED II) [1] [9] | Strong investment; Technological improvements; Waste-to-energy solutions [1] | Stringent environmental mandates (ReFuelEU); Airline decarbonization goals; HEFA technology maturity [10] |

| Primary Feedstocks | Sugarcane, corn, vegetable oils, used cooking oil (UCO) [1] [9] | Solid biomass, wood pellets, agricultural byproducts, municipal solid waste (MSW) [1] | Waste oils, animal fats, agricultural residues; Transition to non-food feedstocks [10] [11] |

| Technology Readiness | Mature (1st Gen); Growing (2nd/3rd Gen) [11] [12] | Mature and established [1] | HEFA is commercially viable; Emerging pathways (FT, ATJ) gaining traction [10] |

| Major Challenges | High production costs; Feedstock availability; Food vs. fuel debate [9] [12] | Feedstock supply chain; Competition with other biomass uses [1] | Very high production costs; Inadequate infrastructure; Feedstock scarcity [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Technology Assessment

A critical component of performance assessment in bioenergy involves standardized experimental protocols to evaluate the efficiency and scalability of new processes.

Protocol for Assessing Advanced Biofuel Biorefineries

Objective: To evaluate the economic and energy performance of advanced biofuels produced from organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW) in a demonstration-scale biorefinery [13].

- Feedstock Preparation: OFMSW is collected and subjected to mechanical pre-treatment to remove inorganic contaminants. The organic fraction is milled to a particle size of <2mm to increase surface area for hydrolysis [13].

- Biochemical Conversion:

- Hydrolysis: The prepared feedstock undergoes enzymatic hydrolysis using a customized cellulase and hemicellulase cocktail to break down lignocellulosic structures into fermentable sugars (C5 and C6).

- Fermentation: Hydrolysate is transferred to a fermenter, and a genetically engineered strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is inoculated. The process occurs under controlled pH (5.0) and temperature (30°C) for 72 hours [9].

- Product Separation & Analysis: Bioethanol is separated via distillation and dehydration. Co-products, such as extracted fats and oils, are quantified. The Energy Return on Investment (EROI) is calculated as the ratio of the energy content of the biofuels produced to the total non-renewable energy input required for the entire process [13].

Protocol for SAF Conversion Pathway Analysis (HEFA)

Objective: To determine the yield and quality of Sustainable Aviation Fuel produced via the Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids (HEFA) pathway [10] [11].

- Feedstock Pre-treatment: Waste oils (e.g., Used Cooking Oil) are filtered and pre-treated to remove water, gums, and free fatty acids.

- Hydroprocessing:

- The pre-treated oil is fed into a hydrotreater reactor alongside hydrogen at elevated temperatures (300-450°C) and pressure (50-150 bar) over a catalyst (typically nickel-molybdenum or cobalt-molybdenum). This reaction deoxygenates the triglycerides, producing linear paraffins and propane [11].

- Isomerization & Cracking: The product stream is passed through an isomerization reactor, where linear paraffins are branched over a zeolite catalyst to improve cold-flow properties, essential for aviation fuel.

- Fractionation: The final synthetic crude is distilled in a fractionation column to separate the various hydrocarbon fractions, including naphtha, sustainable aviation fuel (synthetic paraffinic kerosene), and renewable diesel [11]. The yield and compliance of the SAF fraction with ASTM D7566 are measured [10].

Workflow Visualization of Bioenergy Research and Development

The following diagram illustrates the integrated research and development workflow for advancing bioenergy technologies, from foundational research to commercial deployment.

Figure 1: Integrated R&D workflow for bioenergy technologies, demonstrating the iterative cycle from resource assessment to commercial deployment [14].

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) Production Pathways

The production of Sustainable Aviation Fuel involves multiple technological pathways, each with distinct process flows. The HEFA pathway, being the most commercially mature, is detailed below.

Figure 2: HEFA process flow for SAF production, the dominant commercial pathway [10] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced Biofuel Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research & Development |

|---|---|

| Genetically Enhanced Microbes (e.g., specialized yeasts) | Optimized through genetic engineering for high-yield conversion of fermentable sugars (from sugarcane, corn) or cellulosic sugars into alcohols (ethanol, butanol) [9]. |

| Enzyme Cocktails (Cellulases, Hemicellulases) | Catalyze the hydrolysis of complex lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., agricultural residues, OFMSW) into simple, fermentable sugars for advanced biofuels [13]. |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts (e.g., Ni-Mo, Zeolites) | Critical for hydroprocessing (HEFA) to remove oxygen and isomerize hydrocarbons, and for thermochemical pathways (Fischer-Tropsch) to produce drop-in hydrocarbon fuels [10] [11]. |

| Analytical Standards (e.g., for ASTM D7566) | Certified reference materials used to validate the purity, composition, and compliance of final fuel products, such as SAF, against international quality standards [10]. |

| Model Feedstock Blends | Representative, consistent mixtures of waste oils, fats, or lignocellulosic materials used to reliably test and optimize conversion processes at bench and pilot scales [13]. |

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into biomass logistics and the development of multi-product biorefineries represent the dual frontier of innovation in the bioeconomy. AI technologies are demonstrating transformative potential by optimizing complex biomass supply chains, achieving cost reductions of 20-30% and enhancing predictive accuracy with R² values up to 0.99 in operational models [15]. Concurrently, integrated biorefineries are evolving beyond single-fuel production to co-generate diverse product portfolios including biofuels, biochemicals, and biopower, with certain configurations achieving internal rates of return (IRR) exceeding 20% [16]. This comparative guide objectively evaluates the performance of these technological approaches against conventional alternatives, providing researchers and industry professionals with experimental data and methodological frameworks for assessing bioenergy innovation and efficiency.

Experimental and Analytical Framework for Bioenergy Research

Core Performance Metrics in Bioenergy Systems

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators for Bioenergy Innovation Assessment

| Metric Category | Specific Indicators | Measurement Approaches | Industry Benchmarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic Viability | Internal Rate of Return (IRR), Capital Expenditure, Operating Costs, Payback Period | Techno-economic Analysis (TEA), Life Cycle Costing | IRR > 15% for project viability [16] |

| Environmental Impact | Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, Carbon Intensity, Energy Balance | Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Carbon Accounting | GHG reductions of 50-90% vs. fossil benchmarks [1] |

| Technical Efficiency | Conversion Efficiency, Yield, Purity, Capacity Factor | Process Simulation, Laboratory Analysis, Continuous Monitoring | Biochemical conversion: 70-90% theoretical yield [16] |

| Supply Chain Performance | Transportation Costs, Biomass Quality Consistency, Delivery Reliability | AI Modeling, GIS Analysis, Operational Data Tracking | 20-30% logistics cost reduction via AI optimization [15] |

| Social Impact | Job Creation, Rural Development, Health Outcomes | Social Life Cycle Assessment (sLCA), Multi-criteria Decision Analysis | Employment factors: 0.5-2 jobs per GWh/year [17] |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Bioenergy Innovation

| Research Area | Essential Materials/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Characterization | Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF), Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF) Reagents | Lignocellulosic composition analysis | Feedstock quality assessment for conversion pathways [16] |

| Conversion Processes | Cellulase Enzymes, SO₂ Catalyst, Tetrahydrofuran (THF) Solvent | Biomass pretreatment and fractionation | Steam explosion pretreatment, furfural production [16] |

| AI and Data Analytics | Python (TensorFlow, Scikit-learn), R, MATLAB | Machine learning model development | ANN-based biomass delivery optimization [15] |

| Process Simulation | Aspen Plus, SuperPro Designer | Techno-economic modeling and process optimization | Integrated biorefinery design and simulation [16] |

| Environmental Assessment | GaBi Software, OpenLCA, SimaPro | Life Cycle Inventory and Impact Assessment | Sustainability metrics calculation [16] |

AI in Biomass Logistics: Comparative Performance Analysis

Methodological Protocols for AI Implementation

The experimental protocol for implementing AI in biomass logistics follows a structured approach as demonstrated in recent research [15]. The methodology begins with data acquisition from multiple sources including historical supplier records, biomass quality parameters (moisture content, calorific value), transportation logistics (distance, routes, vehicle types), and economic factors (fuel prices, feedstock costs). The second phase involves data preprocessing where raw data undergoes cleaning, normalization, and feature selection to prepare it for model training. The core implementation utilizes Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) with modular architecture capable of handling the dynamic, nonlinear nature of biomass supply chains. The model is trained using historical operational data from a combined heat and power (CHP) plant, with validation performed through k-fold cross-validation and testing on withheld datasets. Performance metrics including Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), and coefficient of determination (R²) are calculated to quantify predictive accuracy.

Comparative Performance Data: AI vs. Conventional Methods

Table 3: Performance Comparison: AI-Optimized vs. Conventional Biomass Logistics

| Performance Metric | AI-Optimized System | Conventional Methods | Improvement Percentage | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport Cost Reduction | 20-30% lower | Baseline | 20-30% | Polish CHP plant case study [15] |

| Predictive Accuracy (R²) | 0.99 | 0.75-0.85 (typical regression) | ~25% improvement | ANN model vs. traditional statistical models [15] |

| Model Error Rate (MAE) | 0.16 | 0.35-0.50 (typical) | 54-68% reduction | Based on biomass delivery prediction [15] |

| Decision Support Capability | Real-time adaptive recommendations | Static, historical-based planning | Significant enhancement in responsiveness | Dynamic supplier selection under changing conditions [15] |

| Data Handling Capacity | Effective with incomplete datasets | Requires complete data for reliable output | Superior performance in real-world conditions | Demonstration with typical biomass market data gaps [15] |

The experimental results demonstrate that AI-driven approaches, particularly Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), significantly outperform conventional logistics optimization methods. In operational case studies, the ANN-based Biomass Delivery Management model achieved a predictive accuracy of R²=0.99 with minimal error rates (MAE=0.16, MSE=0.02), substantially exceeding the performance of traditional optimization techniques that struggle with the dynamic, nonlinear nature of biomass supply chains [15]. The AI system's capability to handle incomplete datasets typical of biomass markets represents a particular advantage over conventional methods that require comprehensive data for reliable planning. This capability was demonstrated through the model's effective generalization of supplier recommendations based on limited input variables including biomass type, unit price, and annual demand.

Multi-Sectoral Biorefineries: Technological Pathways and Performance

Methodological Framework for Biorefinery Performance Assessment

The experimental protocol for evaluating multi-product biorefinery systems integrates techno-economic analysis (TEA) with environmental life cycle assessment (LCA) to provide comprehensive performance metrics [16]. The methodology begins with process modeling using advanced simulation platforms (e.g., Aspen Plus) to define all key unit operations, equipment specifications, and utility requirements. For biochemical pathways, this includes detailed modeling of pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis, fermentation, and product recovery stages. For thermochemical routes, the modeling encompasses gasification, syngas conditioning, and catalytic synthesis processes. The second phase involves economic assessment calculating capital expenditures (CAPEX), operating expenditures (OPEX), and financial indicators such as Internal Rate of Return (IRR) and payback period. Concurrently, environmental impact assessment follows standardized LCA methodologies (ISO 14040) covering multiple impact categories including global warming potential, acidification, eutrophication, and resource depletion. The functional unit is typically defined as 1 ton of dry biomass input or 1 MJ of product output to enable cross-comparison between different biorefinery configurations.

Comparative Performance of Biorefinery Configurations

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Multi-Product Biorefinery Configurations

| Biorefinery Configuration | Economic Performance (IRR) | Key Product Yields | Environmental Performance | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol + Lactic Acid Co-production | 20.5% | Ethanol: 0.22-0.25 kg/kg biomass; Lactic acid: 0.15-0.18 kg/kg biomass | Moderate GHG reduction; Higher acidification potential | TRL 6-7 (pilot demonstration) [16] |

| Methanol Synthesis | 16.7% | Methanol: 0.35-0.40 kg/kg biomass | Superior environmental performance across multiple impact categories | TRL 7-8 (commercial demonstration) [16] |

| Fischer-Tropsch Syncrude | <15% | Syncrude: 0.25-0.30 kg/kg biomass; Electricity: surplus | Favorable GHG balance; High energy efficiency | TRL 6-7 (pilot demonstration) [16] |

| Ethanol + Furfural Co-production | <15% | Ethanol: 0.18-0.22 kg/kg biomass; Furfural: 0.10-0.12 kg/kg biomass | Inferior environmental performance due to solvent use | TRL 5-6 (lab to pilot scale) [16] |

| Standalone Bioethanol | 12-15% | Ethanol: 0.25-0.28 kg/kg biomass | Moderate environmental impact | TRL 8-9 (commercial) [18] |

Experimental data from techno-economic assessments reveals significant performance variations across different biorefinery configurations. The ethanol-lactic acid co-production pathway demonstrates superior economic returns (IRR 20.5%) with lower sensitivity to market price fluctuations compared to other scenarios [16]. In contrast, thermochemical routes such as methanol synthesis show environmental advantages across most impact categories, except for acidification and eutrophication where biochemical pathways perform better. The assessment identified that sugarcane cultivation remains the most significant contributor to environmental impacts in most scenarios, except for furfural production where the biphasic process with tetrahydrofuran solvent dominates the environmental footprint. These findings highlight the critical importance of integrated techno-economic and environmental assessment when evaluating biorefinery configurations.

Integrated Performance Benchmarking and Innovation Frontiers

Cross-Technology Performance Comparison

Table 5: Integrated Performance Matrix: AI Logistics vs. Biorefinery Innovations

| Innovation Domain | Capital Efficiency | Operational Flexibility | Sustainability Impact | Implementation Timeline | Scalability Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AI-Optimized Logistics | Medium-low investment | High flexibility | Moderate direct impact | Short-term (1-2 years) | Highly scalable across existing infrastructure |

| Biochemical Biorefineries | High capital requirements | Medium flexibility | High GHG reduction potential | Medium-term (3-5 years) | Moderate, feedstock-dependent |

| Thermochemical Biorefineries | Very high capital requirements | Low flexibility | Highest GHG reduction potential | Long-term (5+ years) | High, once demonstrated |

| Multi-Product Biorefineries | Highest capital requirements | Highest product flexibility | Medium-high sustainability profile | Long-term (5+ years) | Moderate, market-dependent |

Emerging Innovation Frontiers

The convergence of AI-driven logistics with multi-product biorefineries represents the next innovation frontier in the bioeconomy. Experimental research indicates that machine learning applications are expanding beyond supply chain optimization to include predictive maintenance of biorefinery operations, real-time process optimization, and product yield forecasting [19]. The most significant performance improvements are observed in integrated systems where AI algorithms optimize both feedstock logistics and conversion processes simultaneously. Second-generation lignocellulosic biorefineries demonstrate particularly strong potential for social impact enhancement, with methodologies like Social Life Cycle Assessment (sLCA) and multicriteria analysis showing greater consistency in evaluating social benefits including job creation and rural development [17].

Recent industry implementations validate these research findings, with companies like Eni achieving substantial operational improvements through biorefinery integration. Enilive reported a 35% year-over-year increase in adjusted EBIT, processing 315,000 metric tons of biofeedstock in Q3 2025 with biorefinery utilization rates climbing to 85% [20]. The company's expansion strategy targets 1.65 million mt/year of biorefinery capacity by year-end, with an additional 1 million mt/year under construction, demonstrating the commercial scalability of integrated biorefinery models.

For researchers and industry professionals, the experimental data and methodological frameworks presented provide robust tools for assessing bioenergy innovation performance. The comparative analysis demonstrates that while technological maturity varies across different approaches, the integration of AI-driven logistics with multi-product biorefineries offers the most promising pathway for enhancing both economic viability and sustainability in the evolving bioeconomy.

The global transition to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions represents one of the most significant challenges and opportunities in modern history. As of 2025, approximately 145 countries have announced or are considering net-zero targets, covering close to 77% of global emissions [21]. This unprecedented political alignment stems from clear scientific consensus: to limit global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels as outlined in the Paris Agreement, emissions must be reduced by 55% by 2035 and reach net zero by 2050 [22]. The policy landscape surrounding these targets serves as a critical catalyst, either accelerating or impeding progress toward climate stability.

For researchers and scientists working on bioenergy innovations, understanding this policy architecture is essential. Policy mandates create market signals, direct research funding, and establish the regulatory frameworks that determine which technologies can scale. This guide examines how current net-zero policies are shaping bioenergy research, with particular focus on experimental data comparing the performance of different bioenergy pathways. By objectively analyzing the intersection of policy mandates and technological performance, we provide a framework for assessing which bioenergy innovations show greatest promise in the context of evolving climate governance.

Global Policy Landscape: Targets, Gaps, and Governance Mechanisms

Current State of National Net-Zero Commitments

The architecture of global climate governance continues to evolve through Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), which outline each country's climate action plan through 2035. As of November 2025, over 100 countries representing more than 70% of global emissions have submitted new NDCs [23]. The table below summarizes key commitments from major emitters:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of 2035 Emissions-Reduction Targets Among Major Emitters

| Country/Region | Previous 2030 Target | New 2035 Target | Net-Zero Target Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 68% from 1990 levels | 81% from 1990 levels | 2050 |

| European Union | 55% from 1990 levels | 66.25%-72.5% from 1990 levels | 2050 |

| United States | 50%-52% from 2005 levels | 61%-66% from 2005 levels | 2050 |

| Japan | 46% from 2013 levels | 60% from 2013 levels | 2050 |

| China | Over 65% carbon intensity reduction below 2005 | 7%-10% from peak | 2060 |

| Canada | 40%-45% from 2005 levels | 45%-50% from 2005 levels | 2050 |

Despite this progress, a significant implementation gap remains. If fully implemented, current unconditional NDCs would reduce emissions by only an additional 3.2 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO₂e) by 2035 compared to 2030, leaving an emissions gap of 28 GtCO₂e to limit warming to 1.5°C [23]. When conditional commitments are included, the gap narrows to 24.4 GtCO₂e, but this still represents a substantial shortfall in required ambition.

Evaluating the Quality of Net-Zero Targets

The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) has developed a nuanced methodology to assess whether the scope, architecture, and transparency of national net-zero targets meet good practice standards [21]. Their evaluation of G20 countries and selected others reveals that most net-zero targets remain vaguely formulated and do not yet conform with good practice across different design elements. As of October 2025:

- Only 6 of 41 assessed countries (responsible for 8% of global GHG emissions) have net-zero targets rated as 'acceptable'

- 11 countries (covering 9% of global emissions) fall into the 'average' category

- Targets covering 63% of global emissions remain 'insufficient' in design [21]

This assessment framework is particularly relevant for bioenergy researchers, as higher-quality targets typically include detailed sectoral pathways, clear carbon accounting methodologies, and transparent plans for carbon dioxide removal (CDR) deployment—all factors that significantly impact bioenergy innovation priorities.

Policy-Driven Bioenergy Innovation: Comparative Performance Assessment

Bioenergy technologies represent a critical component of most net-zero pathways, particularly for hard-to-abate sectors like aviation, shipping, and industrial processes. However, their performance varies significantly based on feedstock, conversion process, and end-use application. The following section provides an experimental comparison of different bioenergy pathways, with particular focus on biodiesel production and engine performance.

Biodiesel Production Optimization: Conventional vs. Machine Learning Approaches

Recent research has demonstrated how machine learning algorithms can significantly optimize biodiesel production parameters compared to conventional experimental design approaches. The table below compares performance data from two methodological approaches:

Table 2: Comparison of Biodiesel Production Optimization Methodologies and Outcomes

| Parameter | Conventional RSM Optimization [24] | Machine Learning Optimization [25] |

|---|---|---|

| Feedstock | Soybean oil | Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) |

| Catalyst | Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | CaO derived from egg shells |

| Optimal Methanol-to-Oil Ratio | 6:1 | 6:1 |

| Optimal Catalyst Concentration | 1.35% | 3% |

| Optimal Reaction Temperature | 60°C (est.) | 80°C |

| Maximum Predicted/Actual Yield | 99.26% | 95% |

| Emission Reduction (CO) | Not specified | 26% lower than diesel |

| Model Performance | R² not specified | CatBoost: R² = 0.955, RMSE = 0.83 |

The machine learning approach employed four boosted algorithms (XGBoost, AdaBoost, Gradient Boosting Machine, and CatBoost) with hyperparameter tuning via grid search and validation through k-fold cross-validation (k=5) [25]. CatBoost emerged as the best-performing model, accurately predicting optimal parameters while identifying methanol-to-oil ratio and catalyst concentration as the most influential variables through feature importance analysis.

Engine Performance: Biodiesel vs. Conventional Diesel

The translation of biodiesel production methods into real-world engine performance is critical for assessing their practical viability. Research examining soybean biodiesel blends in variable compression ratio compression ignition engines revealed several key performance characteristics:

Table 3: Engine Performance Comparison of Biodiesel Blends vs. Conventional Diesel

| Performance Metric | Soybean Biodiesel (B05 Blend) [24] | Conventional Diesel [24] | CaO-based Biodiesel [25] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brake Power | 3 kW (at optimum parameters) | Comparable | Not specified |

| Specific Fuel Consumption | 0.39 kg/kWh | Lower | 4.31% higher than diesel |

| CO Emissions | 0.01% | Higher | 26% lower than diesel |

| NOx Emissions | 50 ppm | Lower | Not specified |

| Smoke Emissions | Not specified | Higher | 13% lower than diesel |

| Brake Thermal Efficiency | Not specified | Higher | 2.83% decline |

The optimization of engine parameters for biodiesel blends used Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with Box-Behnken design, identifying optimal parameters of 4.5 kg load, compression ratio of 18, and B05 fuel blend [24]. This approach generated a design of experiment that reduced the overall cost of experimental investigation while providing statistically validated results.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Bioenergy Performance Assessment

Catalyst Synthesis and Biodiesel Production Protocol

The experimental methodology for producing biodiesel from waste cooking oil using a biomass-derived CaO catalyst involves several precise steps [25]:

Catalyst Synthesis Protocol:

- Egg shells are thoroughly cleaned using distilled water in multiple stages to remove organic matter

- Cleaned shells are air-dried and placed in a furnace at 60°C for 12 hours

- Dried shells undergo mechanical comminution using planetary ball milling

- Powdered material is calcined at 600°C for 6 hours to convert CaCO₃ to CaO

- Final catalyst is stored in airtight containers to prevent hydration

Biodiesel Production Protocol:

- Waste cooking oil is filtered and heated to eliminate moisture

- Acid esterification is performed using H₂SO₄ to reduce Free Fatty Acid (FFA) content

- Transesterification proceeds with optimized parameters: 3% catalyst concentration, 80°C reaction temperature, 6:1 methanol-to-oil molar ratio

- Reactions are conducted in a closed system with reflux condenser to prevent methanol loss

- Biodiesel is separated from glycerol, washed with warm water, and dried

Machine Learning Optimization Protocol

The machine learning workflow for optimizing biodiesel production involves several systematic phases [25]:

- Data Generation: 16 experimental runs investigating effects of catalyst concentration, reaction temperature, and methanol-to-oil molar ratio on biodiesel yield

- Algorithm Selection: Four boosted ML algorithms (XGBoost, AdaBoost, GBM, and CatBoost) applied to model the process

- Model Training: Hyperparameter tuning via grid search with validation through k-fold cross-validation (k=5)

- Performance Validation: Residual plots and statistical metrics (R², RMSE, MSE, MAE) used to ensure reliability and mitigate overfitting

- Interpretation Analysis: Feature importance and partial dependence plots identify influential parameters

Diagram 1: Bioenergy research optimization workflow showing the relationship between policy frameworks, input parameters, optimization methods, and performance outputs

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Bioenergy Research

The experimental protocols for bioenergy innovation require specific reagents and materials with precise functions:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Advanced Biofuel Production Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Experimental Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| CaO derived from egg shells | Heterogeneous catalyst | Provides sustainable, reusable catalytic activity for transesterification; reduces environmental impact compared to homogeneous catalysts [25] |

| Waste Cooking Oil (WCO) | Feedstock | Low-cost raw material that eliminates food-versus-fuel competition; requires pre-treatment to reduce FFA content [25] |

| Methanol | Alcohol agent | Reacts with triglycerides in transesterification; optimal molar ratio critical for maximizing yield [25] [26] |

| H₂SO₄ | Acid catalyst | Pre-treatment agent for esterification to reduce Free Fatty Acid content in low-quality feedstocks [25] |

| Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) | Homogeneous catalyst | Conventional catalyst baseline for comparison with innovative heterogeneous catalysts [24] |

| Soybean oil | Reference feedstock | Standardized feedstock for comparative studies of biodiesel production methodologies [24] |

The interplay between climate policy and bioenergy research creates powerful synergies that can accelerate progress toward net-zero goals. As the data demonstrates, countries with robust, detailed net-zero targets provide clearer signals for research priorities and technology development [21]. Meanwhile, advancements in bioenergy production methods, particularly through machine learning optimization and sustainable catalyst development, offer viable pathways for reducing emissions in hard-to-abate sectors [25] [24].

For researchers and scientists, understanding this policy context is essential for directing innovation toward solutions with the greatest potential for real-world impact. The experimental protocols and performance comparisons outlined in this guide provide a framework for evaluating bioenergy technologies not just in laboratory settings, but within the broader ecosystem of climate governance, market dynamics, and implementation barriers. As the 2025 round of NDCs demonstrates, policy ambition continues to lag behind scientific necessity [23]. Bridging this gap will require both more ambitious policy mandates and more efficient, scalable bioenergy innovations—a challenge that demands continued collaboration between researchers, policymakers, and industry stakeholders.

Methodologies for Performance Assessment: Techno-Economic Analysis and System Optimization

Advanced Optimization Frameworks for Biomass Supply Chain and Logistics

The efficient design and operation of the biomass supply chain are critical to the economic viability and environmental sustainability of bioenergy. The inherent complexities of biomass—including its dispersed availability, seasonality, and low energy density—present significant logistical challenges that can determine the success or failure of bioenergy projects [27]. Advanced optimization frameworks have emerged as essential tools to address these challenges, enabling decision-makers to navigate the trade-offs between cost, efficiency, and sustainability across the entire supply network, from biomass sourcing to final energy delivery [28] [29]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of prevailing optimization methodologies, assessing their performance, applicability, and implementation requirements to inform researchers and industry professionals in selecting appropriate frameworks for specific bioenergy contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Frameworks

Biomass supply chain optimization frameworks can be broadly categorized by their mathematical foundations and approach to handling real-world uncertainties. Table 1 summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the primary methodological approaches identified in current research.

Table 1: Comparison of Biomass Supply Chain Optimization Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Approach | Key Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Programming | Models uncertainty through scenario-based optimization [28] | Handles supply/demand variability explicitly; Provides robust solutions [28] | Computational intensity increases with scenario count [28] | Small to medium problems with quantifiable uncertainty [28] |

| Simulation-Based Optimization | Integrates simulation with optimization algorithms [28] | Handles complex, dynamic systems; Practical computation time for large problems [28] | Does not guarantee optimality (0.59%-8.41% gap from optimal) [28] | Large-scale, complex supply chains with multiple variables [28] |

| Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | Optimizes discrete and continuous decisions simultaneously [30] [29] | Provides exact solutions; Well-established solution techniques [30] | Limited in handling nonlinear relationships directly [29] | Strategic network design, facility location [30] [29] |

| Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) | Incorporates nonlinear process relationships [29] | Simultaneously optimizes supply chain and conversion processes [29] | Computational complexity; Challenging to solve for large instances [29] | Integrated supply chain and process optimization [29] |

| Two-Stage Hybrid Frameworks | Combines predictive analytics with optimization [30] | Data-informed site selection; Addresses economic and environmental objectives [30] | Implementation complexity; Multiple components to integrate [30] | Multi-criteria decision-making under uncertainty [30] |

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The performance of optimization frameworks varies significantly based on problem scale, complexity, and computational resources. Table 2 presents experimental performance data from case studies implementing these methodologies.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Optimization Frameworks

| Methodology | Problem Scale | Solution Quality | Computational Efficiency | Case Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stochastic Programming | Small to medium | Optimal solutions guaranteed for defined scenarios [28] | Longer computation time; becomes impractical for large scenarios [28] | Vietnamese biomass supply chain with uncertain supply capacity [28] |

| Simulation-Based Optimization | Large | Near-optimal (gaps between 0.59% and 8.41% from optimal) [28] | Reasonable run times for large-scale problems [28] | Large Vietnamese biomass supply chain planning [28] |

| Parameter Search | Small | Optimal for parameter tuning [28] | Suitable only for small problems [28] | Small-scale biomass logistics optimization [28] |

| Integrated MINLP | Regional supply network | NPV of ~300 MEUR; 4 MW electricity, 65 MW heat [29] | Viable for regional optimization with process integration [29] | Slovenian regional biomass network with Steam Rankine Cycle [29] |

| Two-Stage Framework with Lagrangian Relaxation | Real-world case study | Cost reduction & minimized carbon emissions [30] | Enhanced computational efficiency while maintaining solution precision [30] | Biofuel supply chain with economic and environmental objectives [30] |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Framework-Specific Methodological Details

Stochastic Programming Implementation

Stochastic programming addresses uncertainties in biomass supply and energy demand through a scenario-based approach. The typical experimental protocol involves:

Scenario Generation: Identify and quantify uncertainty sources (e.g., biomass availability, moisture content, market prices) [28] [29]. Historical data is used to generate probability distributions for these parameters.

Model Formulation: Develop a two-stage stochastic programming model where first-stage decisions (facility locations, capacities) are made before uncertainty resolution, and second-stage decisions (transportation flows, inventory management) respond to realized scenarios [28].

Solution Algorithm: Apply decomposition techniques like Lagrangian relaxation or Benders decomposition to handle computational complexity [30]. The objective typically maximizes expected profit or minimizes expected cost across all scenarios [28].

Validation involves comparing stochastic solutions against deterministic approaches under multiple realizations, demonstrating superior performance when uncertainty is significant [28].

Simulation-Based Optimization Workflow

This methodology combines discrete-event simulation with optimization algorithms, particularly effective for dynamic biomass supply chains:

Simulation Model Development: Create a discrete-event simulation model capturing biomass supply chain processes (harvesting, transportation, storage, conversion) using platforms like Matlab Simulink or specialized simulation software [28].

Parameter Optimization: Utilize built-in optimization tools (e.g., parameter-setting in Matlab Simulink) to iteratively adjust decision variables (e.g., inventory policies, transportation routes) based on simulation outcomes [28].

Performance Evaluation: Run multiple replications for each parameter set to account for stochasticity, using statistical analysis to identify significantly better solutions [28].

The hybrid simulation-optimization approach enables analysis of complex interactions that cannot be easily captured in purely mathematical models [28].

Integrated MINLP for Supply Chain and Process Optimization

This advanced framework simultaneously optimizes supply chain design and conversion process parameters:

Problem Formulation: Develop an MINLP model that integrates strategic-tactical supply chain decisions (biomass sourcing, facility location, transportation) with operational process variables (conversion temperatures, pressures, flow rates) [29].

Objective Function Definition: Typically maximizes Net Present Value (NPV), incorporating capital investments, operational costs, and revenues from energy sales [29].

Solution Strategy: Employ specialized MINLP solvers or metaheuristics (e.g., Genetic Algorithms) to handle non-convexities, often with relaxation techniques to improve computational tractability [29].

Application to a Slovenian case study demonstrated viability with NPV of nearly 300 MEUR, generating 4 MW electricity and 65 MW heat [29].

Visualization of Framework Integration

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and workflow integration between the major optimization frameworks discussed:

Successful implementation of biomass supply chain optimization frameworks requires specialized computational tools and resources. Table 3 catalogues essential research reagents and their functions in developing and deploying these advanced frameworks.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomass Supply Chain Optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Optimization | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Optimization Software | MATLAB Optimization Toolbox, GAMS, CPLEX, Gurobi | Solves MILP, MINLP, and stochastic programming models [28] [29] | Academic licenses available; Performance varies by problem type |

| Simulation Platforms | MATLAB Simulink, AnyLogic, Arena | Models dynamic system behavior for simulation-based optimization [28] | Integration with optimization tools requires specialized scripting |

| Metaheuristic Algorithms | Genetic Algorithms, Tabu Search, Simulated Annealing [30] [27] | Solves complex problems where exact methods are computationally prohibitive [30] [27] | Parameters require careful tuning; No optimality guarantee |

| GIS Integration Tools | ArcGIS, QGIS, spatial analysis libraries | Geospatial data processing for biomass availability and transportation [29] | Essential for realistic case studies; Adds data preparation overhead |

| Data Analytics Components | Artificial Neural Networks, Predictive Analytics [30] | Site selection and parameter prediction in hybrid frameworks [30] | Requires historical data for training; Enhances decision quality |

The selection of an appropriate optimization framework for biomass supply chains depends critically on problem scale, uncertainty characteristics, and decision-making objectives. Stochastic programming provides robust solutions for small to medium problems with quantifiable uncertainties, while simulation-based optimization offers practical approaches for large-scale, dynamic systems despite not guaranteeing optimality [28]. Emerging hybrid frameworks that combine predictive analytics with multi-objective optimization represent promising directions for addressing both economic and environmental dimensions of sustainable bioenergy systems [30]. Future research should focus on enhancing computational efficiency for large-scale integrated models and improving methodological approaches to handle deep uncertainties in biomass availability and market conditions. As bioenergy continues to play a crucial role in renewable energy transitions [31], advanced optimization frameworks will remain essential tools for maximizing the economic viability and environmental benefits of biomass supply chains.

This guide provides an objective comparison of the techno-economic performance of predominant bioenergy pathways, with a focus on power generation. For researchers and scientists, especially those in drug development exploring energy solutions for large-scale facilities, this analysis synthesizes key metrics on cost, operational efficiency, and return on investment (ROI). The data, framed within a performance assessment of bioenergy innovation, reveals that while capital costs remain a significant hurdle, certain pathways like anaerobic digestion (AD) of integrated waste streams can achieve remarkable financial returns, with a payback period of under one year and an Internal Rate of Return (IRR) exceeding 85% in optimized scenarios [32].

Key Techno-Economic Performance Metrics for Bioenergy Pathways

| Metric | Direct Combustion | Gasification | Anaerobic Digestion (Agri-Waste) | Anaerobic Digestion (Integrated Process) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Market Share (2025) [33] | ~42.8% (Largest technology segment) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Typical Feedstock | Solid Biofuel (e.g., wood waste, agricultural residues) [33] | Solid Biofuel [33] | Single-source by-products (e.g., vinasse or stillage) [32] | Mixed waste streams (e.g., vinasse and stillage) [32] |

| Plant Cost (USD) | High capital cost relative to coal [33] | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Energy Output | Steam for turbine [34] | Syngas for combustion or biofuels [35] | Estimated 3.8 × 106 m³ CH₄/year [32] | 14.61 GWh electricity + 1.37 × 105 GJ thermal energy/year [32] |

| Operational Simplicity | High (Mature technology, fuel flexibility) [33] | Moderate (Advanced process) [35] | Moderate (Biological process management) [32] | Moderate (Integrated process management) [32] |

| ROI (Payback Period) | N/A | N/A | Positive NPV (Specifics N/A) [32] | 0.68 years [32] |

| IRR | N/A | N/A | N/A | 86.87% [32] |

| CO₂ Mitigation (ton CO₂eq/year) | Varies with feedstock and scale | Varies with feedstock and scale | N/A | Replacing fossil fuels: ~8,755 [32] |

Bioenergy, derived from organic materials, is a cornerstone of the global transition to a renewable energy mix [35]. Its role is considered "indispensable" for achieving net-zero emissions targets [36]. The techno-economic performance of bioenergy systems varies significantly based on the conversion technology, feedstock type, and plant configuration. Key pathways include:

- Combustion: The most established technology, involving the direct burning of solid biomass like wood pellets or agricultural waste to produce steam that drives a turbine for power generation [34] [33]. Its dominance is attributed to operational simplicity and maturity [33].

- Gasification: A process that converts organic feedstock into a cleaner syngas through a thermo-chemical process, which can then be used for power generation or biofuel production [35] [37]. Advancements are improving its thermal conversion efficiency [35].

- Anaerobic Digestion (AD): A biological process that breaks down organic matter, such as agricultural or municipal waste, in the absence of oxygen to produce biogas [37]. This biogas can be used for combined heat and power (CHP) generation [35].

Comparative Techno-Economic Analysis

Cost Structures and Capital Investment

The initial capital expenditure (CAPEX) is a critical differentiator among bioenergy technologies.

- Combustion & Gasification: These plants require high capital investment, which is often cited as a major market restraint. This includes costs for fuel collection, storage, preprocessing logistics, and the power generation infrastructure itself [33]. For context, the US biomass power industry, which primarily uses these technologies, has an annual revenue of approximately $988 million but is experiencing a decline in the number of producers due to rising operational costs [34].

- Anaerobic Digestion: While also capital-intensive, AD projects can be highly profitable under the right conditions. A techno-economic study of an integrated AD process for ethanol by-products demonstrated a net present value (NPV) of nearly $7.89 million, underscoring its potential financial viability [32].

Efficiency and Energy Output

The efficiency of a bioenergy pathway is measured by its conversion of raw feedstock into useful energy.

- Combustion leads in market share due to its reliability and fuel flexibility, but it may not always be the most efficient in terms of energy recovery [33].

- Advanced Gasification is driving efficiency improvements by producing a cleaner syngas, which enhances power output and can be integrated with CHP systems for superior overall energy efficiency [35].

- Anaerobic Digestion demonstrates strong performance in waste-to-energy applications. A study on co-digesting vinasse and stillage showed the potential to generate 14.61 GWh of electricity and a significant amount of thermal energy annually from waste streams, making it a highly efficient form of resource recovery [32].

Return on Investment (ROI) and Profitability

ROI metrics are paramount for assessing the commercial attractiveness of bioenergy projects.

- Market Context: Supportive government policies, such as production tax credits and renewable portfolio standards, are crucial for improving the ROI of biomass power projects, which face stiff competition from other renewables like wind and solar [34].

- Standout Performer: The aforementioned integrated AD scenario (Scenario 3) exhibits exceptional profitability, with an internal rate of return (IRR) of 86.87% and a payback period of just 0.68 years [32]. This highlights the profound impact of optimizing feedstock mix and process integration on financial returns. The study noted that profitability is highly sensitive to the selling prices of the electricity and thermal energy produced [32].

Experimental Protocols for Techno-Economic Assessment

To ensure the comparability and reliability of techno-economic data, researchers employ standardized evaluation methodologies. The following workflow, derived from a peer-reviewed study on bioenergy from ethanol by-products, outlines a robust protocol for such assessments [32].

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for the techno-economic evaluation of a bioenergy pathway.

Detailed Methodology

The workflow in Figure 1 can be broken down into the following detailed steps, as applied in a specific scientific study [32]:

- Scenario Definition: Establish distinct operational scenarios for comparison. For example:

- Scenario 1: Anaerobic digestion (AD) of a single feedstock (vinasse).

- Scenario 2: AD of a different single feedstock (stillage).

- Scenario 3: Integrated AD of multiple feedstocks (vinasse and stillage).

- Bioenergy Production Modeling: Use established scientific models and equations to predict key output metrics based on the feedstock composition and process parameters. The primary output for an AD process is methane production, which was estimated at 3.8 million m³ per year for the integrated scenario.

- Energy Output Quantification: Convert the primary bioenergy product (e.g., methane) into final energy outputs.

- Electricity Generation: Calculated based on the methane yield and the efficiency of a gas generator. The study output was 14.61 GWh per year.

- Thermal Energy Generation: Calculate the recoverable heat from the process, estimated at 1.37 × 10⁵ GJ per year.

- Environmental Impact Assessment: Calculate the carbon mitigation potential by determining how much CO₂ equivalent (CO₂eq) would be emitted by the fossil fuel sources (e.g., natural gas for heat, grid electricity) that the bioenergy displaces. The integrated process mitigated ~8,755 ton CO₂eq per year [32].

- Profitability Analysis: Core financial modeling to determine economic viability.

- Net Present Value (NPV): The difference between the present value of cash inflows and outflows. A positive NPV indicates profitability. The integrated process had an NPV of $7,890,407.44 [32].

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR): The annualized effective compounded return rate. The integrated process achieved an IRR of 86.87%.

- Payback Period: The time required to recover the initial investment. For the integrated process, this was 0.68 years.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Test the robustness of the economic model by varying key assumptions (e.g., a 10% increase or decrease in the selling price of electricity) to identify which parameters have the greatest impact on profitability. The cited study found project profitability to be highly dependent on energy selling prices [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers replicating or building upon these techno-economic assessments, particularly in a lab-scale setting, the following materials and tools are essential.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Bioenergy Research

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Feedstock Samples | Representative organic materials (e.g., wood chips, agricultural residues, municipal solid waste) used to characterize fuel properties and determine conversion yields [33]. |

| Anaerobic Digester (Lab-Scale) | A bioreactor system used to simulate the anaerobic digestion process, measure biogas production volume, and analyze composition (e.g., CH₄, CO₂ content) [32]. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | An analytical instrument essential for quantifying the percentage of methane (CH₄) in the produced biogas, a critical parameter for energy output calculations [32]. |

| Bomb Calorimeter | Used to determine the calorific value (higher heating value) of solid or liquid biomass feedstocks, which is fundamental to efficiency calculations [33]. |

| Process Modeling Software | Tools (e.g., Aspen Plus, MATLAB) for simulating mass/energy balances and optimizing process parameters like temperature and retention time [32]. |

| Financial Modeling Spreadsheet | A customized template for projecting cash flows, calculating capital and operational expenditures (CAPEX/OPEX), and deriving NPV and IRR [32]. |

This comparison guide objectively demonstrates that the techno-economic performance of bioenergy pathways is not uniform. While mature technologies like combustion offer reliability and market dominance, their growth is challenged by high capital costs and competition [34] [33]. In contrast, innovative and integrated applications of anaerobic digestion present a compelling case for high-efficiency waste valorization, capable of delivering exceptional financial returns and significant carbon mitigation, as evidenced by an IRR of 86.87% and a payback period of 0.68 years in a modeled scenario [32]. For the research community, these metrics underscore the importance of system optimization and strategic feedstock selection in advancing bioenergy as a sustainable and economically viable component of the global energy portfolio.

The global energy landscape is undergoing a significant transformation driven by the urgency to achieve carbon neutrality and sustainable development goals [38]. Among renewable alternatives, bioenergy has emerged as a promising solution due to its potential to provide sustainable low-carbon energy while simultaneously addressing waste management and resource efficiency challenges [38]. The sustainability and efficiency of bioenergy systems are intricately tied to the conversion technologies utilized for transforming biomass into valuable energy products. This review provides a comprehensive performance assessment of three fundamental biomass conversion pathways—thermochemical, biochemical, and physicochemical processes—focusing on their operational parameters, technological principles, efficiency metrics, and implementation prospects.

Biomass, particularly agricultural waste from crop residues, livestock operations, and food processing, represents an abundant renewable resource characterized by its content of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin [39]. Approximately 140 billion metric tons of agricultural waste biomass are generated worldwide annually, presenting a substantial feedstock reservoir for bioenergy production [39]. The efficient conversion of these lignocellulosic materials into solid, liquid, and gaseous fuels depends on selecting appropriate technological pathways matched to feedstock characteristics and desired end products. This assessment systematically compares these pathways within the context of performance optimization for bioenergy innovation and efficiency research.

Biomass Feedstock Composition and Pretreatment Requirements

The effectiveness of any conversion pathway fundamentally depends on biomass feedstock composition and necessary pretreatment steps. Lignocellulosic biomass consists primarily of three structural components: cellulose (30-50%), a linear polymer of glucose units; hemicellulose (20-30%), a branched heteropolysaccharide; and lignin (20-30%), a complex phenolic polymer that provides structural integrity [40]. The relative abundance of these components varies significantly across different agricultural waste materials, directly influencing their conversion efficiency and preferred processing route.

Table 1: Composition of Selected Agricultural Waste Feedstocks

| Feedstock Type | Cellulose (%) | Hemicellulose (%) | Lignin (%) | Notable Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wheat Straw | 30-40 | 20-30 | 15-20 | Abundant cereal residue |

| Corn Stover | 35-45 | 20-30 | 15-20 | High cellulose content |

| Sugarcane Bagasse | 40-45 | 25-30 | 20-25 | High sugar content |

| Rice Straw | 30-40 | 20-25 | 15-20 | High silica content |

| Animal Manure | 20-30 | 10-20 | 10-15 | Lower lignocellulose, high moisture |

The recalcitrance of lignocellulosic biomass, primarily due to lignin's complex structure and its protective matrix around cellulose and hemicellulose, necessitates pretreatment for most conversion pathways [39]. Various pretreatment methods—including physical (milling, grinding), chemical (dilute acid or alkaline hydrolysis), biological (fungal or enzymatic treatment), and combined approaches—aim to disrupt this structural integrity, improving accessibility to polysaccharides and enhancing overall conversion efficiency [39]. The optimal pretreatment strategy depends on both feedstock characteristics and the selected downstream conversion pathway, with significant implications for process economics and energy balance.

Thermochemical Conversion Pathways

Thermochemical conversion processes utilize heat and chemical agents to transform biomass into various energy forms, including biochar, bio-oil, and syngas [39]. These technologies are characterized by relatively short processing times ranging from seconds in fast pyrolysis to minutes in hydrothermal liquefaction, offering significant advantages in conversion speed compared to biological routes [40]. The principal thermochemical pathways include pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal liquefaction, each operating under distinct conditions and yielding different product distributions.

Table 2: Performance Parameters of Thermochemical Conversion Technologies

| Conversion Method | Temperature Range (°C) | Pressure Conditions | Process Duration | Primary Products | Typical Conversion Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast Pyrolysis | 400-600 | Atmospheric, inert atmosphere | 3-5 seconds | Bio-oil (60-75%), Biochar (15-25%), Syngas (10-20%) | 60-75% (liquid yield) |

| Slow Pyrolysis | 300-500 | Atmospheric, inert atmosphere | 30-180 minutes | Biochar (30-35%), Bio-oil (20-30%), Syngas (25-40%) | 70-80% (char yield) |

| Gasification | 800-1000 | Atmospheric, controlled oxygen | Seconds to minutes | Syngas (H₂, CO, CH₄, CO₂) | 70-85% (cold gas efficiency) |

| Hydrothermal Liquefaction | 250-370 | High pressure (5-20 MPa) | 90 minutes | Bio-crude (30-60%), Aqueous phase, Gases | 60-75% (bio-crude yield) |

Experimental Protocols for Thermochemical Conversion

Protocol for Fast Pyrolysis of Agricultural Residues:

- Feedstock Preparation: Feedstock is dried to less than 10% moisture content and ground to particles of 1-2 mm size to enhance heat transfer.

- Reactor System: A fluidized bed reactor is typically used, preheated to the target temperature (450-550°C) with an inert gas (N₂) flow maintaining an oxygen-free environment.

- Processing: Biomass is fed at a controlled rate (1-5 kg/h) with rapid heating rates (>100°C/s) and short vapor residence times (1-2 seconds).

- Product Collection: Vapors are rapidly quenched to condense bio-oil, while non-condensable gases are measured and char is collected from the reactor bottom.

- Analysis: Bio-oil is characterized for water content, pH, heating value, and chemical composition; gas composition is analyzed by GC; char is analyzed for proximate and ultimate composition.

Protocol for Gasification Performance Assessment:

- Feedstock Preparation: Biomass is dried (<15% moisture) and sized to appropriate particles (1-5 cm) to ensure proper flow in the gasifier.

- Gasifier Operation: A downdraft or fluidized bed gasifier is operated at 800-900°C with controlled air or oxygen flow (equivalence ratio 0.2-0.4).

- Gas Cleaning: Raw syngas passes through cyclones for particulate removal, then through tar removal systems (scrubbers, catalytic crackers).

- Gas Analysis: Clean syngas composition (H₂, CO, CH₄, CO₂) is quantified using gas chromatography; heating value is calculated.

- Efficiency Calculation: Cold gas efficiency is determined as (Heating value of syngas × Syngas flow rate) / (Heating value of biomass × Biomass feed rate) × 100%.

Biochemical Conversion Pathways

Biochemical conversion methods utilize microorganisms and enzymes to transform biomass into bioenergy through processes including anaerobic digestion and fermentation [39]. These pathways typically operate at mild temperatures (20-70°C) and near-atmospheric pressures, offering advantages in energy efficiency but requiring longer processing times (days to weeks) compared to thermochemical routes [40]. The primary biochemical pathways include anaerobic digestion for biogas production and fermentation for bioethanol and biobutanol production, each employing distinct microbial consortia and operational parameters.

Table 3: Performance Parameters of Biochemical Conversion Technologies

| Conversion Method | Temperature Range (°C) | pH Range | Hydraulic Retention Time | Primary Products | Typical Conversion Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Digestion | Mesophilic: 30-40Thermophilic: 50-60 | 6.5-7.8 | 15-30 days | Biogas (50-75% CH₄, 25-50% CO₂) | 45-60% (VS destruction) |

| Dark Fermentation | 30-37 | 5.0-6.5 | 2-6 days | Biohydrogen, Organic Acids | 60-80% (COD removal) |

| Ethanol Fermentation | 30-35 | 4.5-5.0 | 48-96 hours | Bioethanol, CO₂ | 75-90% (theoretical glucose yield) |

| ABE Fermentation | 30-37 | 5.5-7.0 | 48-120 hours | Acetone, Butanol, Ethanol | 25-35% (solvent yield) |

Experimental Protocols for Biochemical Conversion

Protocol for Anaerobic Digestion Performance Assessment:

- Inoculum Acclimation: Anaerobic sludge is acclimated to the specific feedstock over 2-3 weeks to establish an active microbial consortium.

- Reactor Setup: Batch or continuous reactors are maintained at mesophilic (35°C) or thermophilic (55°C) conditions with continuous mixing.

- Process Monitoring: pH, volatile fatty acids (VFA), alkalinity, and chemical oxygen demand (COD) are monitored regularly to assess process stability.

- Biogas Measurement: Daily biogas production is measured by water displacement or gas meters, with composition (CH₄, CO₂) analyzed by gas chromatography.

- Efficiency Calculation: Volatile solids destruction is calculated as (VSin - VSout) / VS_in × 100%; methane yield is expressed as L CH₄/g VS destroyed.

Protocol for Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Fermentation:

- Pretreatment: Biomass undergoes dilute acid (0.5-2% H₂SO₄, 140-180°C, 30-60 min) or alkaline (1-5% NaOH, 80-121°C, 30-90 min) pretreatment.

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Pretreated biomass is treated with cellulase enzymes (5-20 FPU/g biomass) in buffer (pH 4.8-5.0) at 50°C for 48-96 hours with shaking.

- Sugar Analysis: Liquid samples are analyzed for glucose, xylose, and inhibitor concentrations using HPLC.

- Fermentation: Hydrolysate is inoculated with yeast (S. cerevisiae) or bacteria (Z. mobilis) at 5-10% v/v and incubated anaerobically at 30-32°C for 48-72 hours.

- Product Quantification: Ethanol concentration is measured by HPLC or GC; yield is calculated as g ethanol per g fermentable sugar.

Comparative Performance Analysis

When evaluating conversion pathways for specific applications, researchers must consider multiple performance metrics including energy efficiency, product quality, environmental impact, and economic viability. The thermochemical and biochemical pathways each present distinct advantages and limitations that determine their suitability for different feedstock types and end-product requirements.

Table 4: Comparative Assessment of Conversion Pathways

| Performance Metric | Thermochemical Pathways | Biochemical Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| Conversion Rate | Fast (seconds to hours) | Slow (days to weeks) |

| Temperature Requirements | High (250-1000°C) | Low (20-70°C) |

| Energy Input | High | Low to moderate |

| Feedstock Flexibility | Broad, handles mixed waste | Specific, requires compatible substrates |

| Product Quality | Varies (may require upgrading) | Generally high purity |

| Scale-up Status | Commercial for some pathways | Commercial for AD, developing for others |

| Capital Cost | High | Moderate to high |

| Environmental Impact | Potential emissions, requires control | Lower emissions, waste stabilization |

| By-product Utilization | Biochar, heat | Digestate (fertilizer), CO₂ |