Biochemical vs Thermochemical Conversion: A Comparative Analysis for Sustainable Biomass Valorization

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of biochemical and thermochemical conversion pathways for researchers, scientists, and professionals in bioenergy and sustainable technology development.

Biochemical vs Thermochemical Conversion: A Comparative Analysis for Sustainable Biomass Valorization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of biochemical and thermochemical conversion pathways for researchers, scientists, and professionals in bioenergy and sustainable technology development. It explores the fundamental principles, operational mechanisms, and specific applications of each method, addressing key technological bottlenecks and optimization strategies. The analysis synthesizes current research to evaluate the energy and environmental performance of these pathways, offering a validated framework for selecting appropriate conversion technologies based on feedstock characteristics and desired end-products. By integrating techno-economic and life-cycle assessments, this review serves as a critical resource for advancing biomass conversion strategies within a circular bioeconomy context.

Understanding Biomass Conversion Pathways: Core Principles and Feedstock Fundamentals

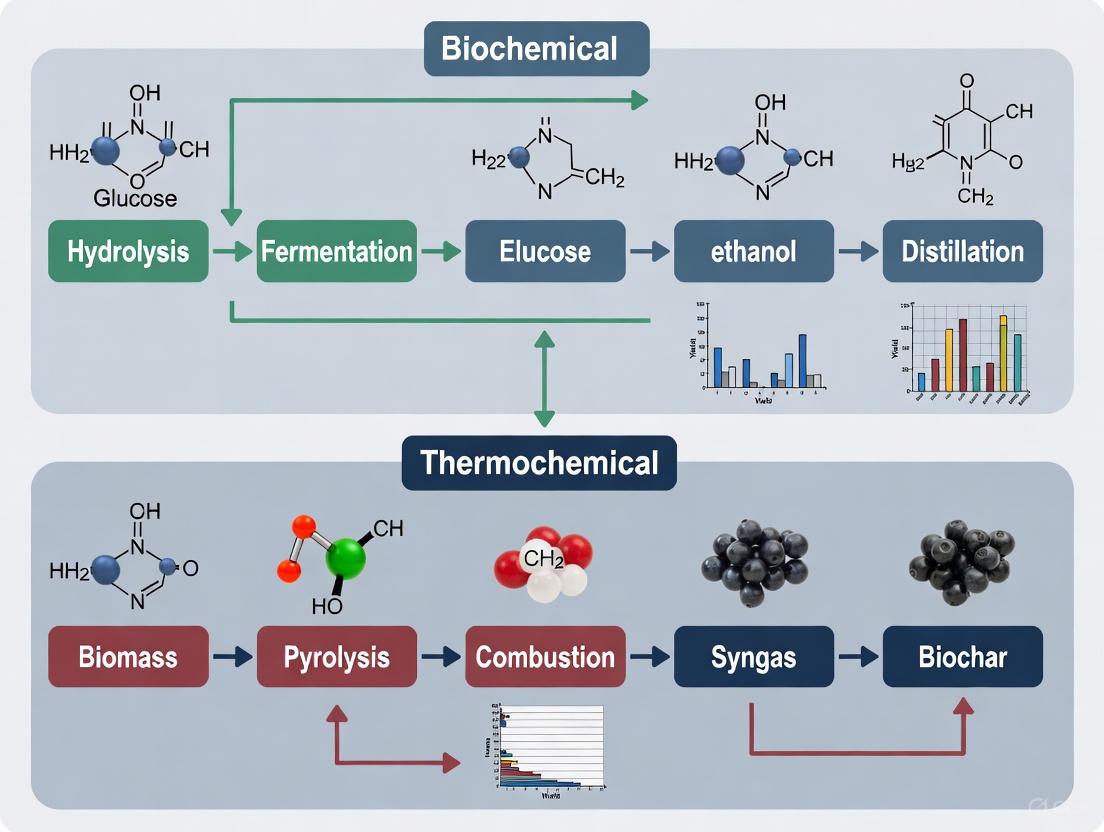

Defining Biochemical and Thermochemical Conversion Paradigms

The transition toward a sustainable, bio-based economy necessitates efficient methods for converting renewable biomass into fuels, chemicals, and power. Two dominant technological paradigms have emerged for this transformation: biochemical conversion and thermochemical conversion. These pathways represent fundamentally different approaches to valorizing biomass, each with distinct operational parameters, product slates, and optimal applications. Biochemical conversion employs biological catalysts like enzymes and microorganisms to break down biomass typically at low temperatures and pressures, while thermochemical conversion utilizes heat and chemical catalysts to decompose biomass at elevated temperatures [1]. Understanding the technical specifications, experimental parameters, and performance metrics of these paradigms is crucial for researchers and industry professionals selecting appropriate technologies for specific feedstocks and desired products within integrated biorefinery frameworks.

The growing strategic importance of these pathways is reflected in market projections. The global biorefinery market, valued at USD 212.05 billion in 2024, is expected to reach USD 468.51 billion by 2034, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.25% [2]. Similarly, the biomass power generation market is projected to grow from US$90.8 billion in 2024 to US$116.6 billion by 2030 [3]. This analysis provides a structured comparison of these core conversion paradigms, presenting key experimental data, methodological protocols, and technical visualizations to inform research and development activities.

Core Principles and Process Mechanisms

Biochemical Conversion Fundamentals

Biochemical conversion relies on biological catalysts to deconstruct biomass into simpler molecules through controlled biological processes. This paradigm operates under mild temperature and pressure conditions, typically ranging from 20°C to 60°C and at or near atmospheric pressure [1]. The primary mechanisms include:

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Specialized enzymes (cellulases, hemicellulases) catalyze the breakdown of complex carbohydrates in lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars like glucose and xylose.

- Fermentation: Microorganisms (yeast, bacteria) metabolize sugars to produce target molecules such as ethanol, organic acids, or biogas. This can occur via submerged fermentation or solid-state fermentation systems.

- Anaerobic Digestion: Microbial consortia in oxygen-free environments progressively convert organic matter into biogas (primarily methane and carbon dioxide) through stages of hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis.

The biochemical pathway is particularly suitable for starch-rich, sugar-rich, or moist biomass feedstocks and enables high selectivity for specific target molecules with minimal energy input for temperature control.

Thermochemical Conversion Fundamentals

Thermochemical conversion utilizes thermal energy and chemical reactions to transform biomass, operating at significantly higher temperatures (300-1500°C) and often at elevated pressures [1]. The principal technologies include:

- Pyrolysis: Thermal decomposition of biomass in the complete absence of oxygen at temperatures typically between 300-600°C to produce bio-oil, biochar, and syngas. Catalytic pyrolysis employing catalysts like copper oxide (CuO) or titanium dioxide (TiO₂) enhances bio-oil quality by boosting yields of valuable compounds like furfural and levoglucosan [4].

- Gasification: Partial oxidation of biomass at high temperatures (800-1500°C) to produce syngas (primarily CO and H₂), which can be catalytically upgraded to fuels and chemicals.

- Combustion: Complete oxidation of biomass with excess air to generate heat and power, typically used in direct firing systems or co-firing applications.

Thermochemical processes excel at handling heterogeneous, dry, and lignocellulosic biomass with high throughput and conversion rates, though they may require more sophisticated emission control systems.

Table 1: Fundamental Operational Parameters of Conversion Pathways

| Parameter | Biochemical Conversion | Thermochemical Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Temperature | 20-60°C (mesophilic) [1] | 300-1500°C [1] [4] |

| Operating Pressure | Near atmospheric [1] | Often elevated (process-dependent) |

| Primary Catalysts | Enzymes, microorganisms [1] | Chemical catalysts (e.g., CuO, TiO₂) [4] |

| Reaction Environment | Aqueous, controlled pH | High-temperature, oxidative/reductive |

| Dominant Mechanisms | Hydrolysis, fermentation, digestion | Pyrolysis, gasification, combustion |

Process Workflow and Pathway Logic

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision pathways for selecting and implementing biochemical versus thermochemical conversion processes, highlighting key decision points and product outcomes.

Experimental Data and Performance Metrics

Conversion Efficiency and Product Yields

Rigorous experimental studies provide critical performance data for comparing conversion pathway efficiencies. Optimized refuse-derived fuel pyrolysis can yield up to 67.9 wt% liquid oil, while gasification produces syngas with heating values up to 10.9 MJ m⁻³ [5]. In cement kiln applications, thermochemical co-processing achieves thermal substitution rates of 50-60% in rotary kilns and 80-100% in calciners [5]. For biochemical systems, agricultural biomass converted to biochar and hydrochar demonstrates significant crop yield improvements of 19.9–36.9% when applied to soil [6].

Machine learning-optimized biochar production can achieve specific surface areas up to 400.0 m²/g, with remarkable environmental remediation capabilities: heavy metal immobilization in soils with efficiencies exceeding 90.0% and contaminant removal from wastewater with efficiencies of 84.0–90.0% for heavy metals and 96.5% for organic pollutants [6]. These metrics highlight the technical capabilities of advanced thermochemical processes.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Conversion Pathways

| Performance Metric | Biochemical Conversion | Thermochemical Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Fuel Yield | Ethanol: ~70-90% theoretical [7] | Bio-oil: Up to 67.9 wt% [5] |

| Byproduct Generation | Stillage, CO₂ | Biochar, ash, syngas |

| Process Efficiency | ~40-60% (energy basis) | ~60-80% (energy basis) [5] |

| Carbon Conversion | ~60-80% | ~75-95% [5] |

| Scale (Typical) | Demonstration to Commercial | Pilot to Commercial |

| Reaction Time | Hours to days | Seconds to minutes |

Economic and Environmental Impact Indicators

Techno-economic and life cycle assessment studies provide crucial data for comparing the sustainability and economic viability of conversion pathways. Thermochemical biochar production shows promising environmental metrics, with greenhouse gas emission reductions of 1.5 to 3.5 tCO₂-eq per ton and production costs as low as $116.0/ton for biochar and $30.0/ton for hydrochar [6]. However, bio-based intermediates face significant economic challenges, with bionaphtha maintaining premiums of $800-$900/mt over fossil naphtha as of H2 2025 [8].

A comparative study of lignocellulosic ethanol conversion processes found that biochemical and thermochemical processes have "very comparable yields, economics, and environmental impacts" when standardized assumptions are applied [7]. This suggests that feedstock availability, local infrastructure, and policy frameworks may be more significant determinants of pathway selection than inherent technical superiority.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Thermochemical Conversion Experimental Protocol: Catalytic Pyrolysis

The following detailed methodology outlines a representative experimental approach for catalytic pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass, adapted from recent research [4]:

Feedstock Preparation and Characterization:

- Collect biomass samples (e.g., coffee straw, eucalyptus residues).

- Dry at 105°C for 24 hours to reduce moisture content below 10%.

- Mill and sieve to achieve uniform particle size (typically 0.5-1.0 mm).

- Perform proximate analysis (moisture, volatile matter, fixed carbon, ash) and ultimate analysis (C, H, N, S, O) following standard ASTM methods.

- Conduct compositional analysis to determine cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content.

Catalyst Preparation:

- Select appropriate catalysts (e.g., copper oxide-CuO, titanium dioxide-TiO₂).

- Prepare catalyst solutions at specified concentrations.

- Employ impregnation method: mix biomass with catalyst solution, stir continuously for 4-6 hours, then dry at 105°C for 12 hours.

- Calculate catalyst loading percentage based on dry biomass weight.

Pyrolysis Experimental Setup:

- Utilize a pyrolyzer coupled with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) for analytical pyrolysis.

- For bench-scale systems: employ a fixed-bed reactor with temperature control, inert gas (N₂) supply, and condensation system.

- Calibrate temperature sensors and flow controllers before experimentation.

Experimental Operation:

- Load catalyst-impregnated biomass sample into the reactor.

- Purge the system with inert gas (N₂) at 100-200 mL/min for 15-20 minutes to ensure oxygen-free environment.

- Heat the reactor to target temperatures (typically 300, 400, 500, and 600°C) at a controlled heating rate (10-50°C/min).

- Maintain at target temperature for 15-30 minutes to complete reactions.

- Collect condensable vapors in cooling traps maintained at 0-4°C to obtain bio-oil.

- Measure non-condensable gases using gas bags or online analyzers.

- Quantify solid residue (biochar) after reactor cooling.

Product Analysis and Characterization:

- Weigh bio-oil, biochar, and gas fractions to determine mass balance.

- Analyze bio-oil composition using GC/MS with appropriate column and temperature program.

- Quantify major compounds (acetic acid, furfural, levoglucosan) using calibration curves with standards.

- Characterize biochar for proximate analysis, surface area (BET method), and heating value.

Biochemical Conversion Experimental Protocol: Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste

This protocol details the methodology for biochemical conversion of food waste through anaerobic digestion, based on current research [9]:

Feedstock Collection and Preparation:

- Collect representative food waste samples from targeted sources (e.g., dairy, cafeteria, processing facilities).

- Homogenize using a mechanical grinder to achieve uniform particle size (<2 mm).

- Characterize physicochemical properties: pH, total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), chemical oxygen demand (COD), and elemental composition.

- Determine carbohydrate, protein, and fat content using standard methods.

Inoculum Acclimation:

- Source anaerobic sludge from operating digesters treating similar waste streams.

- Acclimate inoculum by gradual exposure to food waste over 2-3 weeks.

- Monitor biogas production and volatile fatty acid (VFA) profiles during acclimation.

Experimental Setup:

- Use batch reactors (e.g., 500 mL-1L serum bottles) with rubber septa and aluminum crimps.

- Maintain mesophilic (35±2°C) or thermophilic (55±2°C) conditions in temperature-controlled incubators.

- Include controls with inoculum only to account for background gas production.

- Set up triplicate reactors for each experimental condition.

Process Operation and Monitoring:

- Load reactors with predetermined substrate-to-inoculum ratios (typically 0.5-2.0 gVS/gVS).

- Add necessary nutrients and micronutrients based on feedstock characteristics.

- Adjust initial pH to 6.8-7.2 using buffer solutions if needed.

- Flush headspace with nitrogen gas for 2 minutes to ensure anaerobic conditions.

- Monitor daily biogas production using water displacement or pressure transducers.

- Sample periodically for pH, VFA, and COD analysis.

Analytical Methods:

- Analyze biogas composition (CH₄, CO₂, H₂S) using gas chromatography with thermal conductivity detector.

- Determine VFA profile (C2-C6) using gas chromatography with flame ionization detector.

- Calculate methane yield based on VS added and removed.

- Perform kinetic modeling of methane production using first-order or modified Gompertz models.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details key research reagents, catalysts, and essential materials required for experimental investigations in biomass conversion pathways.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Conversion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specifications & Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Copper Oxide (CuO) | Catalyst for thermochemical processes; enhances furfural yield in pyrolysis [4] | Purity >99%, nanopowder available; Alternatives: Zeolites (ZSM-5), Ni-based catalysts |

| Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) | Catalyst for pyrolysis; improves bio-oil quality [4] | Anatase or rutile phase; Purity >99%; Can be doped with metals |

| Cellulase Enzymes | Hydrolyzes cellulose to glucose in biochemical conversion | From Trichoderma reesei; Activity >500 U/mg; Commercial blends available |

| Methanogenic Inoculum | Microbial consortium for anaerobic digestion | From operating anaerobic digesters; Pre-acclimated to substrate |

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Primary feedstock for conversion processes | Standard reference materials available; Characterized for composition |

| Analytical Standards | Quantification of products (GC/MS, HPLC) | Furfural, levoglucosan, VFA mix, methane |

| Buffer Solutions | pH control in biochemical processes | Phosphate, carbonate buffers; pH indicators |

| Inert Gases | Create anaerobic environments for biochemical and thermochemical processes | Nitrogen (N₂), argon (Ar); High purity (>99.99%) |

Process Integration and Comparative Analysis

Pathway Integration in Biorefinery Systems

Modern biorefineries increasingly integrate both biochemical and thermochemical pathways to maximize resource utilization and product diversification. The lignocellulosic biomass segment held a 38% market share in 2024 for biorefineries, driven by innovations in pretreatment technologies [2]. By technology, the biochemical conversion segment dominated with 44% market share in 2024, while the thermochemical segment is projected to expand rapidly in coming years [2]. This integrated approach allows for cascading biomass utilization where, for example, sugar components are diverted to biochemical processes while lignin-rich residues are directed to thermochemical conversion.

Artificial intelligence is increasingly optimizing these integrated systems. By 2025, AI tools assist in predicting process outcomes, optimizing reaction conditions, and managing resource allocation within dynamic biomass conversion systems [2]. AI-driven digital twins enable real-time control of fermentation, purification, and separation units, allowing operators to adjust parameters preemptively [2]. In thermochemical conversion, machine learning algorithms optimize biochar production parameters to achieve specific surface areas up to 400.0 m²/g and heavy metal immobilization efficiencies exceeding 90% [6].

Comparative Techno-Economic Assessment

A rigorous comparison of lignocellulosic ethanol conversion processes using standardized assumptions found that biochemical and thermochemical approaches have "very comparable yields, economics, and environmental impacts" [7]. This suggests that regional factors, including feedstock availability, policy frameworks, and existing infrastructure, often determine the optimal pathway selection rather than fundamental technical superiority.

The integration of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies with biomass conversion systems is creating new opportunities for carbon-negative energy systems. When combined with CCS, biomass power generation can transition from carbon-neutral to carbon-negative, removing CO₂ from the atmosphere while producing energy [3]. This positions both conversion pathways as critical technologies in climate change mitigation strategies, particularly for hard-to-decarbonize sectors like aviation and heavy industry where bio-based fuels and chemicals offer drop-in replacements for their fossil counterparts.

Lignocellulosic biomass, the most abundant renewable carbon source on Earth, presents a pivotal opportunity for sustainable biofuel and biochemical production. Its recalcitrant nature, governed by the complex interplay of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, poses significant challenges for conversion into valuable products. This guide objectively compares the two primary conversion pathways—biochemical and thermochemical—framed within ongoing research to overcome these compositional hurdles.

Comparison of Conversion Pathways

The following table summarizes the core performance metrics of biochemical and thermochemical conversion, based on consolidated experimental data from recent peer-reviewed studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Biochemical vs. Thermochemical Conversion

| Parameter | Biochemical Conversion | Thermochemical Conversion (Fast Pyrolysis) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Product | Fermentable Sugars (C6/C5) | Bio-Oil |

| Lignin Fate | Remains as solid residue, often unused | Partially depolymerized into bio-oil fractions |

| Hemicellulose Utilization | Requires specialized microbes for C5 fermentation | Decomposed; products contribute to bio-oil |

| Typical Sugar Yield | 70-90% (Cellulose); 50-80% (Hemicellulose)* | N/A (Sugars are degraded) |

| Energy Efficiency | Moderate (due to multiple steps) | High |

| Technology Readiness | Commercial (2G Ethanol Plants) | Pilot to Demonstration Scale |

| Key Challenge | Cost-effective pretreatment & enzyme loading | Bio-oil instability and high oxygen content |

*Yields are highly dependent on the pretreatment severity and biomass source.

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Dilute Acid Pretreatment for Biochemical Conversion This protocol details a standard method for hemicellulose hydrolysis and lignin redistribution to enhance enzymatic cellulose digestibility.

- Biomass Milling: Reduce biomass (e.g., corn stover, switchgrass) to a particle size of 0.5-2 mm using a Wiley mill.

- Reaction Setup: Load 10g (dry weight) of biomass into a 500 mL pressurized batch reactor.

- Acid Impregnation: Add 100 mL of a 1.0% (w/w) sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄) solution to achieve a 10:1 liquid-to-solid ratio.

- Pretreatment: Heat the reactor to 160°C and maintain for 30 minutes under constant agitation (150 rpm).

- Quenching & Separation: Rapidly cool the reactor. Separate the solid fraction (cellulose-rich) from the liquid hydrolysate (containing hemicellulose-derived sugars and solubilized lignin) via vacuum filtration.

- Neutralization & Analysis: Wash the solid residue with deionized water until neutral pH. Analyze the solid for glucan content and the liquid for xylose and inhibitor (furfural, HMF) concentrations using HPLC.

Protocol 2: Fast Pyrolysis for Thermochemical Conversion This protocol outlines the process for rapid thermal decomposition of biomass into a liquid bio-oil.

- Biomass Preparation: Dry and mill biomass to <1 mm particles to ensure rapid heat transfer.

- Reactor Loading: Continuously feed 100 g/hr of dried biomass into a fluidized bed reactor pre-heated to 500°C.

- Inert Atmosphere: Maintain a nitrogen (N₂) gas flow (1-2 L/min) as the fluidizing agent to ensure an oxygen-free environment.

- Pyrolysis & Vapor Quenching: The biomass undergoes rapid heating (<2 seconds). The resulting hot vapors are immediately quenched and condensed using a series of condensers maintained at 0-4°C.

- Product Collection: Collect the condensed liquid as bio-oil. Separate and measure non-condensable gases and solid char.

- Bio-Oil Analysis: Characterize the bio-oil for water content (Karl Fischer titration), chemical composition (GC-MS), and higher heating value (bomb calorimeter).

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Biochemical Conversion Workflow

Thermochemical Conversion Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Cellulase Enzyme Cocktail | A mixture of enzymes (endoglucanases, exoglucanases, β-glucosidases) that synergistically hydrolyze cellulose into glucose. |

| Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | A common catalyst in dilute-acid pretreatment to solubilize hemicellulose and disrupt lignin structure. |

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [EMIM][OAc]) | Advanced solvents for biomass pretreatment that effectively dissolve cellulose and lignin with high potential for recovery. |

| ZSM-5 Zeolite Catalyst | A microporous catalyst used in catalytic fast pyrolysis to deoxygenate pyrolysis vapors, improving bio-oil quality. |

| S. cerevisiae (Engineered Yeast) | A workhorse microbial host for ethanol fermentation; engineered strains can co-ferment C5 and C6 sugars. |

| Nitrogen (N₂) Gas | Creates an inert atmosphere during thermochemical processes to prevent combustion and control reaction pathways. |

The decomposition of complex substances into simpler compounds is a fundamental process in chemistry, biology, and environmental engineering. Two fundamentally distinct pathways—microbial catalysis and thermal decomposition—enable the breakdown of materials through entirely different mechanisms. Microbial catalysis leverages the sophisticated machinery of living microorganisms and their enzymes to perform highly specific, energy-efficient decomposition under mild conditions [10]. In contrast, thermal decomposition employs elevated temperatures to drive chemical breakdown through kinetic energy transfer, often resulting in broader reaction profiles and different product distributions [11]. Understanding the fundamental distinctions between these processes is crucial for selecting appropriate technologies in applications ranging from waste valorization and biofuel production to environmental remediation and chemical synthesis. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these divergent approaches, supported by experimental data and methodological protocols to inform research and development across scientific disciplines.

Core Principles and Mechanistic Foundations

Microbial Catalysis: Biological Precision

Microbial catalysis encompasses decomposition processes mediated by living microorganisms or isolated enzymatic systems. These biological catalysts operate through specialized active sites that bind specific substrates and lower the activation energy for their transformation. A key advantage lies in their exceptional specificity, enabling selective transformation of target compounds within complex mixtures without affecting surrounding molecules [10]. For instance, specialized bacterial systems like the methylthio-alkane reductase (MAR) in Rhodospirillum rubrum perform reductive cleavage of carbon-sulfur bonds in volatile organic sulfur compounds with remarkable precision [12]. This enzymatic complex requires ATP as an energy source and functions under anaerobic conditions, showcasing how biological systems integrate decomposition with cellular energy metabolism.

Microbial decomposition typically occurs under ambient temperatures and pressures, making it inherently energy-efficient compared to thermal approaches. However, these systems can be sensitive to environmental conditions such as pH, temperature fluctuations, and the presence of inhibitory substances [13]. The kinetics of microbial catalysis are generally slower than thermal decomposition, following Michaelis-Menten kinetics rather than simple Arrhenius temperature dependence. Another distinctive feature is the capacity of microbial systems to catalyze challenging chemical transformations under mild conditions, such as the cleavage of strong carbon-fluorine bonds in per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—a remarkable feat given the exceptional bond strength of C-F bonds (approximately 485 kJ/mol) [14].

Thermal Decomposition: Energy-Driven Breakdown

Thermal decomposition relies on the application of heat to drive chemical breakdown through molecular excitation. As temperature increases, molecules gain vibrational energy, eventually exceeding the bond dissociation energy of the weakest chemical bonds [11]. This process follows fundamental chemical kinetics described by the Arrhenius equation, where reaction rates increase exponentially with temperature. Unlike biological systems, thermal decomposition typically lacks specificity, often resulting in multiple parallel and sequential reaction pathways that generate complex product distributions [15].

The thermal decomposition of biomass illustrates this mechanistic profile, where lignocellulosic components undergo distinct degradation pathways: hemicellulose decomposes first (200-260°C), followed by cellulose (240-350°C), and finally lignin (280-500°C) [11]. This differential decomposition arises from variations in bond strengths and structural stability within each polymer. Thermal processes offer advantages in processing throughput and speed, enabling rapid treatment of substantial material volumes. However, they typically require significant energy input and can produce undesirable byproducts through secondary reactions, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other recalcitrant compounds [13].

Table 1: Fundamental Mechanism Comparison

| Characteristic | Microbial Catalysis | Thermal Decomposition |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Source | Biochemical (ATP, reducing equivalents) | Thermal energy |

| Temperature Range | Ambient (20-45°C) | Elevated (200-1000°C) |

| Reaction Specificity | High (enzyme-substrate specificity) | Low (bond strength dependent) |

| Kinetic Profile | Michaelis-Menten saturation kinetics | Arrhenius temperature dependence |

| Primary Controls | Enzyme concentration, nutrient availability, pH | Temperature, residence time, heating rate |

| Common Applications | Wastewater treatment, soil bioremediation, biogas production | Pyrolysis, gasification, waste incineration, chemical synthesis |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Process Efficiency and Product Spectrum

The choice between microbial and thermal decomposition pathways significantly impacts process efficiency and product distributions, particularly in biomass valorization applications. Thermochemical conversion techniques like pyrolysis, gasification, and liquefaction operate at temperatures between 300°C and 1000°C, achieving rapid conversion within seconds to minutes [11]. Fast pyrolysis of agricultural waste at 450-550°C with short residence times (typically 1-2 seconds) can convert up to 75% of biomass into bio-oil, with the remainder forming biochar and syngas [11]. In contrast, biochemical conversion through anaerobic digestion proceeds at mesophilic temperatures (35-40°C) but requires retention times of 15-30 days to achieve substantial volatile solids destruction and biogas production [13].

The product spectrum also differs substantially between these pathways. Thermal decomposition of lignocellulosic biomass typically generates bio-oil, syngas (primarily H₂, CO, CO₂, and CH₄), and biochar in proportions determined by process conditions [11]. Microbial systems, particularly anaerobic digestion, predominantly produce biogas (CH₄ and CO₂) and digestate, with the potential for recovery of valuable biochemicals like organic acids and solvents through controlled fermentation processes [13]. For particularly recalcitrant compounds like PFAS, thermal methods can achieve high destruction efficiencies but often require extreme conditions—incineration at 1000-1200°C—with potential formation of degradation byproducts [14]. Microbial approaches offer a promising low-energy alternative but face challenges in achieving complete mineralization of these persistent contaminants.

Environmental Footprint and Economic Considerations

Life cycle assessment studies reveal distinct environmental footprints for these decomposition pathways. Thermal conversion processes, particularly combustion and gasification, achieve volume reduction exceeding 90% and can directly recover energy, offsetting their operational energy requirements [11]. However, they face challenges with emissions control, particularly for nitrogen oxides, sulfur compounds, and particulate matter, often requiring sophisticated air pollution control systems [13]. Microbial systems generally have lower greenhouse gas emissions and can operate effectively at smaller scales, but may produce waste biomass and odors requiring management [13].

Economic considerations reveal context-dependent advantages. Thermal systems typically have higher capital costs and require specialized materials resistant to high temperatures and corrosion, but offer faster treatment times and smaller physical footprints [11]. Microbial systems generally have lower operating costs, particularly for dilute waste streams, but may require larger land areas and more skilled operation to maintain biological activity [13]. The economic viability of both approaches is highly influenced by feedstock characteristics, with thermal methods generally more tolerant of heterogeneous or contaminated inputs, while microbial processes often require more consistent substrate composition to maintain process stability.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Biomass Conversion

| Performance Metric | Microbial Catalysis | Thermal Decomposition |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Conversion Time | Days to weeks | Seconds to minutes |

| Energy Efficiency | 30-50% (biochemical to biogas) | 50-80% (biomass to bio-oil) |

| Carbon Retention | 40-60% in biogas | 30-70% in bio-oil/biochar |

| Water Requirement | High (maintain aqueous environment) | Low (often dry processes) |

| Scale-up Considerations | Linear scaling common | Complex reactor design challenges |

| Byproduct Management | Digestate treatment, potential odors | Ash disposal, emissions control |

| Typical Conversion Efficiency | 40-60% volatile solids destruction | 70-90% mass conversion |

Experimental Methodologies

Protocol for Microbial Decomposition Studies

Objective: Evaluate the catalytic activity of microbial consortia or purified enzyme systems in decomposing target substrates.

Materials:

- Anaerobe Workstation: Creates oxygen-free environment for anaerobic microorganisms [12]

- Activity Assay Reagents: ATP, electron donors (dithiothreitol or NADPH), substrate solutions [12]

- Analytical Instruments: HPLC for substrate quantification, GC-MS for gaseous products, spectrophotometer for enzyme kinetics [12]

Methodology:

- Culture Preparation: Inoculate defined medium with microbial culture or purified enzyme preparation under appropriate environmental conditions (e.g., anaerobic chamber for strict anaerobes) [12].

- Reaction Setup: Combine culture/enzyme preparation with buffered substrate solution, electron donors, and essential cofactors in sealed reaction vessels.

- Process Monitoring: Periodically sample reaction mixture for substrate depletion and product formation using appropriate analytical methods (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS).

- Kinetic Analysis: Determine Michaelis-Menten parameters (Kₘ, Vₘₐₓ) from initial rate measurements at varying substrate concentrations.

- Control Experiments: Include heat-inactivated controls and no-substrate controls to account for abiotic degradation and background signals.

Data Interpretation: Microbial decomposition typically shows sigmoidal kinetics for allosteric enzymes or hyperbolic kinetics following Michaelis-Menten behavior. Temperature dependence follows a bell-shaped curve with optimal activity typically between 25-45°C for mesophilic organisms [13].

Protocol for Thermal Decomposition Analysis

Objective: Characterize the thermal degradation behavior and kinetic parameters of materials under controlled heating conditions.

Materials:

- Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA): Measures mass loss as a function of temperature and time [15]

- Pyrolysis Reactor: Bench-scale fixed-bed or fluidized-bed reactor with temperature control [11]

- Product Collection System: Condensers for bio-oil, gas bags or online analyzers for gaseous products [11]

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Grind and sieve material to uniform particle size (typically 100-500μm) to ensure heat transfer consistency.

- TGA Analysis: Heat sample (5-20mg) under controlled atmosphere (N₂ for pyrolysis, air for combustion) at multiple heating rates (5-50°C/min) to determine degradation profile.

- Kinetic Analysis: Apply model-free methods (e.g., Friedman, Flynn-Wall-Ozawa) or model-fitting approaches to determine apparent activation energy from TGA data.

- Product Characterization: Analyze condensed products (bio-oil) by GC-MS, FTIR; characterize gaseous products by GC-TCD/FID; analyze biochar by elemental analysis, surface area measurement.

- Mass Balance Closure: Quantify all product streams to achieve mass balance closures of 95-105%.

Data Interpretation: Thermal decomposition typically shows distinct mass loss regions corresponding to degradation of specific components. Kinetic analysis reveals apparent activation energies typically ranging from 100-250kJ/mol for biomass components [11].

Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: Fundamental pathways for microbial and thermal decomposition processes

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Their Applications

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme Preparations | Catalyze specific decomposition reactions with high selectivity | PpnN nucleosidase for nucleotide cleavage [16], MAR for C-S bond cleavage [12] |

| Defined Microbial Consortia | Provide diverse catalytic capabilities for complex substrates | PFAS-degrading bacteria, anaerobic digestate cultures [14] |

| ATP & Cofactor Solutions | Supply energy and electron transfer capabilities for enzymatic reactions | MAR activity assays, enzyme kinetic studies [12] |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer | Quantifies mass loss during thermal decomposition | Biomass pyrolysis kinetics, polymer degradation studies [15] |

| Bench-Scale Pyrolysis Reactors | Enable controlled thermal processing with product collection | Bio-oil production optimization, catalytic pyrolysis studies [11] |

| Anaerobic Chambers | Maintain oxygen-free environments for anaerobic microorganisms | Cultivation of strict anaerobes, oxygen-sensitive enzyme assays [12] |

Microbial catalysis and thermal decomposition represent fundamentally distinct approaches to molecular deconstruction, each with characteristic advantages and limitations. Microbial systems offer unparalleled specificity, energy efficiency, and operational under mild conditions but typically require longer processing times and can be sensitive to environmental conditions and inhibitors. Thermal methods provide rapid processing, high throughput, and tolerance to diverse feedstocks but demand substantial energy input and can produce complex product mixtures requiring further refinement.

The optimal choice between these pathways depends heavily on application-specific requirements including feedstock characteristics, desired products, scale considerations, and economic constraints. Emerging research continues to expand the capabilities of both approaches, from engineering enzymes with enhanced stability and novel catalytic functions to developing advanced thermal processes with improved energy integration and product control. Hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both biological and thermal processing represent a promising frontier for sustainable decomposition technologies across industrial, environmental, and energy applications.

The transition from fossil-based resources to renewable biomass is a cornerstone of the global strategy to mitigate climate change and enhance energy security. The success of this bio-based economy hinges on the efficient conversion of widely available feedstocks, primarily agricultural residues, forestry waste, and organic solid wastes, into fuels and chemicals. These feedstocks are not uniform; their physical and chemical characteristics vary significantly, influencing their suitability for different conversion pathways. The two primary technological routes for converting lignocellulosic biomass are biochemical conversion and thermochemical conversion. The selection between these pathways is critically dependent on the specific properties of the feedstock, impacting process economics, product yield, and environmental footprint [17] [18]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the suitability of different waste biomass categories for biochemical and thermochemical conversion processes, supporting informed decision-making for researchers and industry professionals.

Feedstock Composition and Key Attributes

The viability of a biomass feedstock for a given conversion pathway is largely determined by its composition. The three main structural polymers—cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—along with ash and moisture content, are the most critical indicators.

Cellulose, a linear polymer of glucose, is a primary source for fermentable sugars in biochemical processes and a contributor to bio-oil yields in thermochemical processes. Hemicellulose, a branched heteropolymer, is relatively easily hydrolyzed into sugars but can also lead to the formation of degradation inhibitors. Lignin, a complex, aromatic polymer, is largely unutilized in biochemical conversion but is a valuable energy-dense component in thermochemical processes [18] [13]. High ash content, particularly alkali metals, can cause catalytic poisoning, slagging, and equipment fouling in thermochemical reactors, making it a detrimental attribute for these systems [17].

The table below summarizes the typical compositional range of common feedstock categories, highlighting their inherent variability.

Table 1: Typical Compositional Range of Common Biomass Feedstocks

| Feedstock Category | Cellulose (% Dry Basis) | Hemicellulose (% Dry Basis) | Lignin (% Dry Basis) | Ash (% Dry Basis) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Residues (e.g., Corn Stover, Rice Straw) | 30-50 | 20-35 | 15-20 | 5-15 [17] [13] | High ash and seasonal variability. |

| Herbaceous Energy Crops (e.g., Switchgrass) | 30-50 | 20-35 | 15-20 | 5-10 [17] | Moderate ash content. |

| Forestry Waste (e.g., Wood Chips, Poplar) | 40-50 | 20-30 | 20-30 | 1-5 [17] [19] | Low ash, high lignin content. |

| Organic Solid Waste (e.g., Food Waste, MSW) | 5-30 | 10-25 | 5-20 | 5-30 [13] | Highly variable and heterogeneous. |

Biochemical Conversion Pathway

Biochemical conversion relies on biological catalysts, such as enzymes and microbes, to break down biomass into simple sugars, which are subsequently fermented into products like ethanol, biogas, or organic acids. The process typically involves pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis, and fermentation [17] [18].

Figure 1: Biochemical Conversion Process Workflow

Feedstock Suitability for Biochemical Conversion

This pathway is best suited for feedstocks with high cellulose and hemicellulose content, as these are the primary sources of fermentable sugars. The recalcitrance of the plant cell wall, largely due to lignin content and structure, is a major barrier. Therefore, feedstocks with lower lignin or those that respond well to pretreatment are preferred.

Table 2: Biochemical Conversion Feedstock Suitability and Yield Data

| Feedstock | Recommended Pretreatment | Key Experimental Findings | Reported Ethanol Yield (or equivalent) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn Stover | Dilute Acid [17] | Pretreatment effective in disrupting cell wall structure; high ash content can be mitigated by fractionation [17]. | Used as a benchmark in NREL models [7]. |

| Switchgrass | Ionic Liquid, Dilute Acid [17] | Continued development of pretreatment is required to achieve high sugar yields due to natural recalcitrance [17]. | Performance can be lower than woody feedstocks without optimized pretreatment [19]. |

| Sweet Sorghum | Milling, Dilute Alkali [13] | High fermentable sugar content leads to excellent financial and environmental performance in biochemical routes [19]. | Among the highest yields for biochemical processes [19]. |

| Pine | Steam Explosion [17] | High lignin content lowers conversion yields; lignin degradation during pretreatment can form inhibitors [17] [19]. | Lower financial performance due to low yield [19]. |

Thermochemical Conversion Pathway

Thermochemical conversion uses heat and chemical processes to break down biomass into intermediate gases, liquids, or solids. The primary technologies include pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) [18] [13]. These processes are generally less sensitive to lignin content and more sensitive to ash and moisture.

Figure 2: Thermochemical Conversion Process Workflow

Feedstock Suitability for Thermochemical Conversion

Thermochemical processes are more feedstock-flexible but have specific quality requirements. Low ash content, especially low alkali metal concentration, is critical to avoid catalyst poisoning and operational issues like slagging. High lignin content is favorable as it contributes to higher energy yields [17].

Table 3: Thermochemical Conversion Feedstock Suitability and Yield Data

| Feedstock | Conversion Process | Key Experimental Findings | Product Quality & Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pine | Gasification to Mixed Alcohols [19] | Low ash content and high lignin make it ideal; produced highest financial performance in NREL analysis [19]. | High syngas quality and high alcohol yield [19] [7]. |

| Switchgrass | Fast Pyrolysis, Gasification [17] | High ash content leads to decreased product yields and increased catalytic poisoning/slagging [17] [19]. | Lower financial and environmental performance due to ash [19]. |

| Forest Residues | Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) [17] | Woody biomass with low ash is favored for high yields and decreased equipment problems [17]. | Produces high yields of bio-crude oil [17]. |

| Municipal Solid Waste | Gasification, Pyrolysis [18] | Heterogeneity and contaminants are a challenge; pre-processing is essential [18]. | Potential for energy recovery but requires robust gas cleaning [18]. |

Direct Comparative Analysis: Biochemical vs. Thermochemical

A holistic comparison of the two pathways reveals distinct advantages, challenges, and trade-offs, heavily influenced by feedstock choice.

Table 4: Overall Comparison of Conversion Pathways

| Parameter | Biochemical Conversion | Thermochemical Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| Ideal Feedstock Traits | High cellulose/hemicellulose, low lignin, low ash [17]. | Low ash (esp. alkali metals), low moisture, high lignin [17]. |

| Feedstock Flexibility | Lower flexibility, sensitive to lignin and inhibitors [19]. | Higher flexibility, can process a wider range of feedstocks [19]. |

| Primary Products | Ethanol, biogas, butanol, organic acids [18]. | Syngas, bio-oil, biochar, electricity, FT-fuels [18] [13]. |

| Typical Conversion Time | Long (hours to days for fermentation) [13]. | Very fast (seconds in fast pyrolysis to minutes in gasification) [18] [13]. |

| Environmental Impact (LCA) | Slightly better on GHG emissions and fossil fuel consumption [20]. | Lower direct, indirect, and life cycle water consumption [20]. |

| Key Challenges | Long processing times, low product yields, inhibitor formation [17] [21]. | High processing costs, high temperatures, tar formation, catalyst poisoning [17] [18]. |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Advancing biomass conversion technologies requires a suite of specialized reagents and materials for process development and analysis.

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomass Conversion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids | Solvent for pretreating biomass; effectively disrupts lignin and cellulose crystallinity [17]. | Biochemical Pretreatment |

| Dilute Acid/Alkali | Chemical catalyst for pretreatment; hydrolyzes hemicellulose and disrupts lignin structure [17]. | Biochemical Pretreatment |

| Cellulase & Hemicellulase Enzymes | Biological catalysts for hydrolyzing cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars [18]. | Biochemical Hydrolysis |

| MoS₂ Catalyst | Catalyzes the conversion of cleaned syngas into mixed alcohols [19]. | Thermochemical Synthesis |

| Specialized Microbes | Genetically engineered organisms for fermenting C5 and C6 sugars to target products [18]. | Biochemical Fermentation |

| Gas Cleaning Adsorbents | Remove contaminants like tars, H₂S, and other catalyst poisons from raw syngas [18]. | Thermochemical Syngas Conditioning |

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The bio-feedstock market is projected to grow significantly, reaching USD 224.9 billion by 2035, driven by carbon regulations and circular economy policies [22] [23]. A key trend is the move away from standalone processes toward integrated biorefineries that combine thermochemical and biochemical methods to maximize resource efficiency and valorize all biomass components [21]. For instance, lignin-rich residues from biochemical processes can be converted into bio-oil via pyrolysis, while aqueous streams from thermochemical processes can be treated anaerobically [21]. Future progress depends on overcoming challenges related to feedstock pretreatment, catalyst development, and system optimization to improve the economic viability and environmental performance of both pathways [13].

The escalating global energy demand and the imperative to mitigate climate change have intensified the search for sustainable, carbon-neutral energy sources [24]. Biomass, derived from organic materials such as plants and agricultural residues, stands out as a critical renewable resource due to its unique ability to form a closed carbon cycle [24]. During growth, biomass absorbs atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) via photosynthesis; when converted to energy, it releases a similar amount of CO2, resulting in a net-neutral impact on atmospheric carbon over its lifecycle [24] [18]. This positions biomass utilization as an essential pathway for achieving carbon peaking and neutrality targets within global energy transition strategies [24].

The efficiency and sustainability of this carbon cycle are largely determined by the conversion technology employed. Biochemical and thermochemical pathways represent two distinct methodological approaches for transforming raw biomass into usable energy, fuels, and chemicals [1]. The selection between these pathways involves critical trade-offs concerning carbon conversion efficiency, process kinetics, product slate, and overall environmental impact [13] [25]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two technological families, focusing on their operational parameters, carbon neutrality potential, and practical implementation for researchers and scientists in the field.

Comparative Analysis: Biochemical vs. Thermochemical Conversion

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of biochemical and thermochemical conversion pathways, providing a foundational comparison for researchers.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Biomass Conversion Pathways

| Feature | Biochemical Conversion | Thermochemical Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Utilizes biological agents (enzymes, microorganisms) to break down biomass [1]. | Applies heat and chemical catalysts to decompose biomass [1]. |

| Primary Processes | Anaerobic Digestion (Biogas), Fermentation (Bioethanol) [13]. | Pyrolysis, Gasification, Hydrothermal Liquefaction, Combustion [24] [11]. |

| Typical Operating Conditions | Low temperatures and pressures; ambient or near-ambient [1]. | High temperatures (300°C–1000+°C), often with high pressure [1] [24]. |

| Key Product Spectrum | Biogas (CH₄, CO₂), Bioethanol, Butanol, Organic Acids [13]. | Bio-oil, Syngas (CO, H₂), Biochar, Bioheat [24] [11]. |

| Carbon Conversion Efficiency | Generally lower due to incomplete microbial digestion of lignin [13]. | Generally higher; can convert a larger fraction of biomass carbon, including lignin, into energy products [24]. |

| Process Duration | Slow (days to weeks for anaerobic digestion; hours for fermentation) [25]. | Fast (seconds to minutes for fast pyrolysis; minutes to hours for gasification/slow pyrolysis) [18] [25]. |

| Technology Readiness | High for first-gen biofuels; advanced processes (e.g., cellulosic ethanol) at commercial/pilot scale [26]. | High for combustion; advanced processes (e.g., catalytic pyrolysis, HTL) at pilot and demonstration scale [26]. |

Quantitative Performance and Environmental Impact

Life-cycle assessment (LCA) studies provide critical data for evaluating the carbon neutrality potential of different biorefinery pathways. The following table compiles experimental data and LCA results from recent research.

Table 2: Experimental Data and Environmental Impact Comparison of Select Biorefinery Pathways

| Pathway Description | Key Operational Parameters | Product Yield & Carbon Efficiency | Environmental Impact (WTW GHG Emissions)* & Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algae Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) - Pathway I [26] | • Feedstock: Wet algal biomass• Process: Hydrothermal Liquefaction• Avoids energy-intensive drying [26] | • Produces bio-crude for upgrading to renewable diesel [26]. | • Very low emissions; negative net emissions reported [26].• Superior resource efficiency and reduced carbon footprint. |

| Combined Algae Processing (CAP) - Pathway II [26] | • Feedstock: Algal biomass• Process: Integrates biochemical & thermochemical processes• Utilizes CO₂ as a feedstock [26] | • Produces renewable diesel and other products [26]. | • Very low emissions [26].• Shows high potential for sustainable fuel production. |

| Palm Fatty Acid Distillation (PFAD) - Pathway III [26] | • Feedstock: Palm fatty acid distillate (second-gen, non-food crop) [26]• Process: Esterification/Hydroprocessing | • Industrial-scale production of renewable diesel [26]. | • Highest emissions among the three pathways [26].• Raises concerns over land use and sustainability. |

| Lignocellulosic Biochemical Conversion [18] | • Feedstock: Agricultural residues (e.g., straw)• Process: Pretreatment, Enzymatic Hydrolysis, Fermentation | • Cellulosic ethanol yield varies with pretreatment efficiency [27]. | • Can reduce GHG emissions by up to 86% compared to fossil fuels [18].• Technical challenges in lignin depolymerization remain. |

| Refuse-Derived Fuel (RDF) Gasification [5] | • Feedstock: Processed municipal solid waste (RDF)• Process: Gasification | • Syngas with heating values up to 10.9 MJ m⁻³ [5]. | • Reduces waste volume and recovers energy, mitigating landfill methane emissions [5].• Emission control is critical for environmental performance. |

WTW: Well-to-Wheel, a system boundary that includes emissions from feedstock cultivation, fuel production, and transport [26].

Experimental Protocols for Key Conversion Pathways

Protocol for Biochemical Conversion: Anaerobic Digestion of Agricultural Waste

Objective: To produce biogas (methane and carbon dioxide) through the microbial digestion of agricultural waste under anaerobic conditions [13].

Materials:

- Feedstock: Chopped or ground agricultural residue (e.g., wheat straw, corn stover).

- Inoculum: Anaerobic sludge from an operational digester.

- Bioreactor: Batch or continuous-flow anaerobic digester with gas collection system.

- Analytical Equipment: Gas chromatograph (for CH₄, CO₂ analysis), pH meter, Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) apparatus.

Methodology:

- Pretreatment: Subject the biomass to a mild alkaline (e.g., NaOH) or physical (e.g., milling) pretreatment to disrupt the lignocellulosic structure and enhance biodegradability [13].

- Inoculation and Loading: Mix the pretreated feedstock with anaerobic inoculum in a predetermined ratio (e.g., based on volatile solids) inside the bioreactor.

- Anaerobic Incubation: Flush the headspace of the reactor with nitrogen to ensure anaerobic conditions. Seal the reactor and maintain it at a mesophilic temperature (35-37°C) [13].

- Monitoring and Analysis: Monitor biogas production daily using water displacement or a gas meter. Periodically analyze the biogas composition (CH₄/CO₂ ratio) via gas chromatography. Track pH and COD reduction throughout the process (typically 20-40 days) [13].

- Data Calculation: Calculate the ultimate methane yield (m³ CH₄ per kg of volatile solids added) and the organic removal efficiency.

Protocol for Thermochemical Conversion: Fast Pyrolysis for Bio-Oil Production

Objective: To convert lignocellulosic biomass into liquid bio-oil through rapid thermal decomposition in an inert atmosphere [24] [11].

Materials:

- Feedstock: Dried and finely ground biomass (e.g., sawdust, rice husk) with low moisture content (<10%).

- Reactor: Bench-scale fluidized bed pyrolysis reactor system.

- Carrier Gas: Nitrogen or another inert gas.

- Condensation System: A series of condensers cooled by a mixture of dry ice and ethanol.

- Analytical Equipment: Gas chromatograph, bio-oil characterization equipment (e.g., for water content, viscosity, heating value).

Methodology:

- Feedstock Preparation: Dry and sieve the biomass to a uniform particle size (typically < 2 mm) to ensure efficient heat transfer [24].

- Reactor Setup and Purging: Load the reactor with bed material (e.g., sand). Heat the reactor to the target temperature (typically 450-550°C) [24]. Initiate a flow of inert carrier gas to purge the system of oxygen.

- Pyrolysis Reaction: Continuously feed the prepared biomass into the hot reactor at a controlled rate. Maintain a very short vapor residence time (typically 1-2 seconds) to maximize liquid yield [24] [11].

- Product Collection: Direct the hot vapor and gas products through the condensation train, where the bio-oil condenses and is collected. Collect the non-condensable gases in a gas bag for analysis. The solid residue (biochar) remains in the reactor or is separated by a cyclone.

- Product Analysis: Weigh the collected bio-oil and biochar to determine mass yield. Analyze the bio-oil for its physicochemical properties and the gas for its composition (CO, CO₂, CH₄, H₂) [24].

Pathway Visualization and Logical Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points in selecting and implementing biomass conversion pathways, highlighting the distinct stages of biochemical and thermochemical processes.

Diagram 1: Biomass Conversion Pathways Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Biomass Conversion Research

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulolytic Enzymes (e.g., Cellulase, Hemicellulase) [27] | Hydrolyzes cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars during biochemical conversion. | Specific activity, thermostability, and resistance to inhibitors are critical performance parameters. |

| Anaerobic Sludge Inoculum [13] | Serves as a consortium of microorganisms for initiating and maintaining anaerobic digestion processes. | Source (e.g., wastewater plant, existing digester) and microbial diversity affect biogas yield and stability. |

| Zeolite & Metal-Oxide Catalysts (e.g., ZSM-5, Ni-based catalysts) [24] [11] | Used in catalytic pyrolysis and syngas reforming to upgrade bio-oil quality and enhance gas yields. | Key properties include acidity, pore size, and resistance to coking and sintering at high temperatures. |

| Lignocellulosic Standard (e.g., α-Cellulose, Xylan, Kraft Lignin) [18] | Used as model compounds for method development and calibration in analytical studies. | Provides a consistent and defined material for understanding the conversion of individual biomass components. |

| Inert Carrier Gas (e.g., High-Purity N₂, Ar) [24] | Creates an oxygen-free environment for thermochemical processes like pyrolysis and gasification. | High purity is essential to prevent unwanted oxidation reactions that can form tar and reduce product quality. |

The pursuit of carbon neutrality through biomass utilization is a complex endeavor with no single optimal solution. Both biochemical and thermochemical pathways offer distinct and viable routes for closing the carbon cycle, yet they present different profiles in terms of technology maturity, carbon conversion efficiency, and environmental performance.

Third-generation thermochemical pathways, such as algae hydrothermal liquefaction, demonstrate remarkable potential for achieving very low or even negative net emissions [26]. Thermochemical methods generally offer higher carbon conversion efficiency and faster processing times, making them suitable for a wider range of feedstocks, including lignin-rich materials [24] [25]. Conversely, advanced biochemical pathways, while facing challenges with recalcitrant feedstocks, can achieve significant GHG reductions—up to 86% for cellulosic ethanol—and benefit from continuous advancements in enzymatic and microbial technologies [18].

The choice between these pathways is highly context-dependent, influenced by factors such as feedstock type, desired end-products, and regional economic and policy frameworks. The integration of artificial intelligence for process optimization and the development of hybrid biorefinery concepts that combine the strengths of both pathways are promising frontiers for research [27] [11]. Future progress hinges on supportive policies, continued research into catalyst development and feedstock pretreatment, and collaboration across academia, industry, and government to firmly establish biomass as a cornerstone of a sustainable, carbon-neutral energy future [27] [24].

Operational Mechanisms and Product Spectrum: From Laboratory to Industrial Application

The transition toward a circular bioeconomy has intensified the focus on technologies that convert waste biomass into valuable energy and chemicals. Among these, biochemical conversion pathways—specifically anaerobic digestion (AD), fermentation, and syngas bioconversion—offer sustainable alternatives to fossil-based production. These processes leverage microbial consortia or pure cultures to transform organic materials found in agricultural waste, food waste, and livestock manure into biofuels and biochemicals. Anaerobic digestion is a well-established biological process where microorganisms break down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen, primarily producing biogas [28]. Syngas fermentation, a hybrid thermochemical-biochemical process, involves the biological conversion of synthesis gas (a mixture of CO, H₂, and CO₂) into products such as alcohols and volatile fatty acids (VFAs) [29] [30]. This guide provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of these biochemical pathways, focusing on their operational performance, microbial mechanisms, and industrial scalability to inform research and development strategies.

Biochemical conversion methods are distinguished by their operational principles, microbial pathways, and resultant product profiles. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of anaerobic digestion, conventional fermentation, and syngas bioconversion.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of key biochemical conversion pathways.

| Feature | Anaerobic Digestion (AD) | Syngas Fermentation | Conventional Fermentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Products | Biogas (CH₄, CO₂), Digestate [28] | Ethanol, Acetic Acid, H₂, VFAs [29] [30] | Ethanol, Butanol, Lactic Acid [13] |

| Core Microbial Process | Hydrolysis, Acidogenesis, Acetogenesis, Methanogenesis [28] | Wood-Ljungdahl Pathway, Biological Water-Gas Shift [29] [30] | Sugar fermentation by microorganisms (e.g., yeast, bacteria) [13] |

| Typical Feedstocks | Dairy cow manure, food waste, sewage sludge [31] [28] | Syngas from gasification of biomass (e.g., wood, MSW) or industrial off-gases [29] [32] [30] | Sugar-rich or starch-rich biomass (e.g., corn, sugarcane) [13] |

| Optimal Temperature | Mesophilic (~37°C) [28] | Mesophilic (~37°C) to Thermophilic [30] | Varies (e.g., ~30°C for yeast) [13] |

| Key Advantage | Waste stabilization, nutrient recovery in digestate [28] | Utilizes gaseous waste streams; high product flexibility [29] [30] | Established, high-volume production from simple sugars [13] |

| Key Limitation | Susceptible to inhibition (e.g., VFA, ammonia accumulation) [28] | Low gas-liquid mass transfer rate limits productivity and scalability [30] | Competition with food sources; often requires sterile conditions [30] |

The performance of these systems is highly dependent on operational parameters. For instance, in anaerobic digestion, the organic loading rate (OLR) is a critical factor. A study on co-digesting cattle manure with green grocery waste demonstrated that an OLR of 3 g VS L⁻¹ day⁻¹, combined with an applied voltage of 0.7 V in a microbial electrolysis cell (MEC) system, yielded a significantly higher biogas production compared to a conventional AD system [31]. Similarly, in syngas fermentation, parameters like gas composition, pH, and temperature are crucial for directing microbial "decision-making" toward desired products like hydrogen or VFAs [29].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Protocol for Enhanced Anaerobic Digestion with Microbial Electrolysis Cell (AD-MEC)

Objective: To overcome limitations of conventional AD (low biogas yield, long retention times) by integrating a Microbial Electrolysis Cell (MEC) to enhance methane production [31].

- 1. Reactor Setup: Configure a single-stage anaerobic reactor with an effective volume of 6 L. Include multiple electrode sets (e.g., 2E: one anode/cathode pair; 4E: two anode/cathode pairs) to increase the surface area for microbial biofilm formation. The control setup has no electrodes [31].

- 2. Feedstock Preparation: Collect and homogenize cattle manure and green grocery waste. Use these substrates in a co-digestion setup to ensure a balanced carbon-to-nitrogen ratio [31].

- 3. Operation: Maintain mesophilic conditions (37°C). Apply a low external voltage (e.g., 0.7 V) across the electrodes. The system is operated at various Organic Loading Rates (OLRs), with a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 10 days [31].

- 4. Data Collection: Monitor and record daily biogas production. Analyze the composition of the biogas (e.g., CH₄, CO₂) using gas chromatography. Measure the reduction in chemical oxygen demand (COD) to assess organic matter removal [31].

Table 2: Experimental data from AD-MEC study showing the impact of electrode configuration and OLR on biogas yield [31].

| Electrode Setup | OLR (g VS L⁻¹ day⁻¹) | Applied Voltage (V) | Biogas Yield | CH₄ Yield (NL/g VS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (No electrodes) | 3.0 | 0.0 | Baseline | Baseline |

| 2E (Single electrode pair) | 3.0 | 0.7 | Significantly higher than control | Significantly higher than control |

| 4E (Double electrode pairs) | 3.0 | 0.7 | Highest (significantly higher than 2E and control) | 0.232 (1.6x higher than single pair) |

Protocol for Syngas Fermentation for Hydrogen and VFA Production

Objective: To utilize syngas (CO, CO₂, H₂) as a feedstock for microbial consortia to produce high-value resources like hydrogen and volatile fatty acids (VFAs) [29] [30].

- 1. Inoculum and Conditioning: Source a natural microbial consortium from diverse anaerobic sludges (e.g., from wastewater treatment or food waste digesters). Condition the consortium by gradually exposing it to syngas to adapt the microbes and suppress methanogenic activity, thereby favoring the production of intermediates like H₂ and VFAs [29] [30].

- 2. Bioreactor Operation: Use a continuous stirred-tank reactor (CSTR) or a bubble column reactor designed to maximize gas-liquid mass transfer—a key challenge in syngas fermentation. Maintain strict anaerobic conditions [30].

- 3. Parameter Control: Control critical parameters to steer microbial pathways. pH is a primary lever; a pH below 5.0 typically inhibits methanogenesis and promotes acidogenesis. The H₂/CO ratio in the syngas feed also influences whether the biological water-gas shift reaction or the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway is favored, determining the end products [29].

- 4. Monitoring and Analysis: Monitor gas uptake rates (CO and H₂ consumption). Quantify liquid-phase products using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) for VFAs (e.g., acetic, propionic, butyric acids) and gas chromatography for H₂ and other gases in the headspace [29].

Microbial Pathways and Metabolic Networks

The core of these bioconversion processes lies in the complex metabolic networks of microorganisms. The following diagrams illustrate the key pathways for anaerobic digestion and syngas fermentation.

Diagram 1: Anaerobic digestion four-stage pathway.

Diagram 2: Syngas fermentation metabolic pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in biochemical conversion requires specific reagents and equipment. The following table details essential items for setting up and monitoring these bioprocesses.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions and materials for biochemical conversion experiments.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Sludge Consortium | Serves as the inoculum, providing a diverse microbial community to carry out the digestion or fermentation processes [29] [28]. | Sourced from wastewater treatment plants; used as the starting culture in both AD and syngas fermentation reactors [29]. |

| Stainless Steel Fermenter (SS316L) | The core bioreactor vessel; provides corrosion resistance and durability for sterile-grade operations [33]. | Used in pilot-scale and industrial-scale fermenters for syngas fermentation and other bioprocesses [33]. |

| In-line Fermentation Monitors (pH, DO) | Provides real-time, continuous monitoring of critical process parameters (pH, dissolved oxygen) without sampling interruption [34]. | Essential for maintaining optimal pH for acetogenesis in AD or for steering product spectrum in syngas fermentation [29] [34]. |

| Nutrient Media | A nutrient-rich growth medium supplying essential minerals, vitamins, and nutrients for microbial growth and product formation [33]. | Used in syngas fermentation to support the growth of acetogenic bacteria; composition can be optimized for specific products [33]. |

| Gas Chromatography (GC) System | Analyzes the composition of biogas (CH₄, CO₂, H₂) and syngas, providing quantitative data on process performance [31] [30]. | Used to measure methane yield in AD experiments and hydrogen production in syngas fermentation studies [31]. |

| HPLC System | Separates, identifies, and quantifies components in a liquid sample, crucial for measuring VFA and alcohol concentrations [29]. | Used to monitor VFA accumulation (e.g., acetic, propionic acid) in AD and syngas fermentation broths [29] [28]. |

Anaerobic digestion, syngas fermentation, and conventional fermentation each present distinct profiles of technical maturity, product versatility, and operational challenges. AD is a robust technology for waste management and renewable energy (biogas) production, with performance highly dependent on OLR and capable of enhancement through integration with MECs [31] [28]. Syngas fermentation offers a unique pathway to convert gaseous waste streams into a flexible array of high-value chemicals, though its scalability is currently constrained by gas-mass transfer limitations [29] [30]. The future of these biochemical pathways lies in integrated biorefinery approaches. Combining thermochemical processes like gasification with biochemical syngas fermentation can maximize resource recovery from complex biomass, creating a more circular and sustainable bioeconomy [18] [30]. Continued research in microbial strain selection, metabolic engineering, and advanced reactor design will be crucial to overcome existing bottlenecks and unlock the full potential of these technologies.

Thermochemical conversion represents a suite of technologies that utilize heat and chemical processes to transform biomass into valuable energy products, including biofuels, bio-oil, syngas, and biochar. These technologies stand in contrast to biochemical conversion methods, which rely on biological agents like enzymes and microorganisms to break down biomass at lower temperatures [1]. The thermochemical pathway is characterized by its ability to operate at very high temperatures and pressures, efficiently processing a wide range of feedstocks, including lignocellulosic biomass, agricultural residues, and organic wastes [1] [18]. The primary thermochemical technologies—pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL)—offer distinct advantages in terms of processing speed, feedstock flexibility, and product profiles, making them crucial components in the development of sustainable bioenergy systems and the transition toward a circular bioeconomy.

The fundamental principle underlying all thermochemical processes is the decomposition of complex organic polymers in biomass through the application of heat under controlled environments. This decomposition leads to the production of solid, liquid, and gaseous fuels, with the specific product distribution depending on the process parameters and the technology employed [13]. Compared to biochemical pathways, thermochemical methods generally offer higher energy output per unit of biomass, with studies indicating yields ranging from 0.1–15.8 MJ/kg depending on the feedstock and process conditions [35]. However, these processes also typically incur greater greenhouse gas emissions (0.003–1.2 kg CO₂/MJ) and higher costs (0.01–0.1 USD/MJ) than their biochemical counterparts, highlighting important trade-offs that must be considered in technology selection [35].

Comparative Analysis of Thermochemical Technologies

The following table provides a systematic comparison of the three major thermochemical conversion technologies across key technical and operational parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Thermochemical Conversion Technologies

| Parameter | Pyrolysis | Gasification | Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Definition | Thermal decomposition in the absence of oxygen [13] | Partial oxidation of carbonaceous feedstock [13] | Conversion of wet biomass in aqueous medium at high pressure and temperature [36] [37] |

| Typical Temperature Range | Varies by type: Fast (300-700°C), Slow (300-550°C) [18] | Typically above 700°C [18] | 220-350°C [36] [37] |

| Pressure Conditions | Atmospheric [18] | Atmospheric or elevated [18] | 6-20 MPa (high pressure) [37] |

| Primary Product | Bio-oil, Biochar, Syngas [13] | Syngas (H₂, CO, CH₄, CO₂) [13] | Biocrude (Bio-oil) [36] [38] |

| Feedstock Moisture Requirement | Low moisture required (<10-15%) [18] | Low to moderate moisture preferred [18] | Handles high moisture biomass (>50%); no drying needed [37] |

| Reaction Time | Fast: 3-5 seconds; Slow: 30-180 minutes [18] | Seconds to minutes (continuous process) | 15 minutes to 90 minutes [18] [37] |

| Key Advantages | High bio-oil yield (fast pyrolysis); Biochar production [18] | Syngas flexibility for power, fuels, chemicals [13] | Processes wet feedstocks directly; energy-efficient for high-moisture biomass [37] |

| Key Challenges | Requires dry feedstock; bio-oil requires upgrading [18] | Tar formation; syngas cleaning required [18] | High-pressure equipment; corrosion issues [18] |

Technology-Specific Operational Protocols

Pyrolysis

Pyrolysis involves the thermal decomposition of biomass in the complete absence of oxygen. The process can be categorized into slow, fast, and flash pyrolysis, with the primary differences being heating rate, temperature, and residence time, which ultimately determine the product distribution [18] [13].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Feedstock Preparation: Biomass feedstock (e.g., rice straw, wood chips) is dried to a moisture content below 10-15% and ground to particles of 1-2 mm size to ensure efficient heat transfer [18].

- Reactor Configuration: The processed feedstock is fed into a pyrolysis reactor (e.g., fluidized bed, fixed bed). An inert atmosphere is established and maintained by purging with nitrogen gas at a flow rate of 0.5-1 L/min.

- Process Conditions: The reactor is heated to the target temperature (300-700°C) at a defined heating rate (e.g., 10-100°C/min for slow pyrolysis; >1000°C/s for fast pyrolysis). Vapors are rapidly condensed in a condensation system maintained at 0-4°C.

- Product Collection: The condensed liquid is collected as bio-oil. Non-condensable gases (syngas) are collected in gas bags or vented. Solid residue (biochar) is collected after the reactor cools down [13].

Gasification

Gasification converts biomass into a combustible gas mixture (syngas) through a partial oxidation reaction at high temperatures [13].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Feedstock Preparation: Biomass is dried (moisture content ~10-15%) and sized to 1-5 cm particles to ensure uniform gas flow.

- Reactor Operation: Biomass is fed into a gasifier (e.g., fluidized bed, downdraft). A controlled amount of gasifying agent (air, oxygen, or steam) is introduced. For air gasification, an equivalence ratio (ER) of 0.2-0.4 is typically maintained.

- Process Conditions: The reactor operates at temperatures typically above 700°C. The residence time for solids ranges from minutes to hours, while gas residence time is on the order of seconds.

- Syngas Cleaning: The raw syngas containing contaminants like tar, particulates, and alkali compounds is passed through a series of cleaning units—cyclones, scrubbers, and filters—to produce clean syngas suitable for end-use applications [18].

Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL)

HTL is a thermochemical process specifically designed to convert high-moisture biomass into biocrude in a hot, pressurized water environment [36] [38] [37].

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Slurry Preparation: Wet biomass (e.g., microalgae, macroalgae, food waste) is homogenized with water to create a slurry with 10-20% solid content. No prior drying is required.

- Reactor Loading: The slurry is loaded into a high-pressure batch reactor (e.g., Parr reactor). The reactor is sealed and purged with an inert gas like nitrogen to remove oxygen.

- Process Conditions: The reactor is heated to a target temperature between 240-320°C while maintaining autogenous pressure, typically in the range of 15-30 MPa. The mixture is held at this condition for a reaction time of 15-90 minutes with continuous stirring [36] [37].

- Product Separation: After the reaction, the reactor is cooled to room temperature. The gas phase is vented and collected. The remaining products are separated by solvent extraction (e.g., using dichloromethane) or centrifugation into four phases: biocrude, aqueous phase, solid biochar, and gas [36].

Figure 1: Decision workflow for selecting thermochemical conversion technologies based on feedstock moisture and target products.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimental research in thermochemical conversion requires specific reagents, catalysts, and materials. The following table details key items and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Thermochemical Conversion Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Feedstocks | Raw material for conversion; composition affects yield and product quality. | Agricultural residues (rice straw, wheat straw) [13], Algal biomass (Chlorella, Nannochloropsis) [36], Forestry residues, Organic waste [37] |