Benchmarking Bioenergy Systems: Strategies for Optimizing Reliability and Energy Output in 2025

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking the reliability and energy output of modern bioenergy systems.

Benchmarking Bioenergy Systems: Strategies for Optimizing Reliability and Energy Output in 2025

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for benchmarking the reliability and energy output of modern bioenergy systems. Tailored for researchers and energy development professionals, it explores foundational concepts, advanced optimization methodologies, common operational challenges, and comparative validation techniques. By synthesizing current research and real-world applications, this review serves as a strategic guide for enhancing the performance, economic viability, and integration of biomass energy within the broader renewable energy landscape, supporting informed decision-making for sustainable energy projects.

Defining Reliability and Output in Modern Bioenergy Systems

Reliability is a cornerstone for the commercial viability and widespread adoption of bioenergy systems. For researchers and scientists developing these technologies, a clear framework for benchmarking reliability is essential. This guide objectively compares the performance of different bioenergy system components based on three core reliability factors: Feedstock Stability, Conversion Technology, and System Maintenance. Performance is evaluated through the lens of energy output consistency, operational continuity, and technical maturity, synthesizing data from current experimental and commercial studies to provide a standardized comparison for drug development professionals and research scientists engaged in sustainable energy solutions.

Feedstock Stability Comparison

Feedstock stability—encompassing consistent availability, predictable composition, and resistance to degradation—is a primary determinant of bioenergy system reliability. Variations in feedstock properties can significantly impact conversion efficiency and lead to undesirable fluctuations in energy output [1]. The table below compares key feedstock types based on critical reliability metrics.

Table 1: Reliability and Performance Comparison of Common Bioenergy Feedstocks

| Feedstock Type | Composition Variability | Energy Density (MJ/kg, approximate) | Pre-processing Requirements | Key Reliability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woody Biomass (e.g., forest residues) [1] [2] | Low | 18-20 [2] | Drying, sizing | High stability; consistent composition; suitable for long-term storage [1]. |

| Agricultural Residues (e.g., corn stover, straw) [3] [4] | Moderate to High | 15-17 | Collection, densification, drying | Seasonal availability; variable moisture and ash content; logistics can be complex [5]. |

| Energy Crops (e.g., switchgrass) [3] [2] | Low | 17-19 | Harvesting, drying | Cultivated for consistent properties; high yield per acre [2]. |

| Municipal Solid Waste [3] [1] | Very High | 8-11 | Sorting, removal of contaminants | High variability in composition and moisture; requires robust pre-processing [1]. |

| Used Cooking Oils & Fats [3] [6] | Moderate | 35-37 [6] | Filtration, dewatering | High energy density; consistent core composition but variable contamination [6]. |

Experimental Data on Feedstock Impact

The critical influence of feedstock stability on final energy output is demonstrated by research into biodiesel quality. The cloud point and oxidative stability of the final fuel—key indicators of performance and reliability—are directly determined by the feedstock used [6]. For instance, experimental data shows that biodiesel produced from Yellow Grease exhibits a more favorable (lower) cloud point compared to many other feedstocks, making it a more reliable fuel in colder temperatures [6]. Furthermore, the carbon intensity of the resulting biofuel, a key metric in life-cycle assessments and regulatory incentives, is heavily dependent on the feedstock, with waste-based feedstocks typically achieving lower carbon intensities and higher economic incentives [6].

Conversion Technology Reliability

The conversion technology is the engine of the bioenergy system, and its reliability is a function of technological maturity, conversion efficiency, and flexibility in handling different feedstocks. The following table benchmarks the primary conversion pathways.

Table 2: Reliability and Performance Comparison of Bioenergy Conversion Technologies

| Conversion Technology | Technology Readiness Level | Typical Conversion Efficiency | Feedstock Flexibility | Key Reliability Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Combustion [5] [7] | High (Commercial) | 20-30% (Electricity) [5] | Low to Moderate | Simple operation; high maturity; but can produce emissions affecting operational continuity [2]. |

| Anaerobic Digestion [3] [4] | High (Commercial) | 40-60% (Biogas) [4] | Moderate (best for wet feedstocks) | Robust biological process; handles high-moisture waste; continuous operation possible [3]. |

| Gasification [3] [7] | Medium to High | 60-80% (Syngas) [7] | High | Produces versatile syngas; shorter reaction time than biochemical routes; sensitive to feedstock moisture content [7]. |

| Fast Pyrolysis [4] [7] | Medium (Demonstration) | 60-75% (Bio-oil) [7] | High | High conversion efficiency; produces unstable bio-oil that requires upgrading [4]. |

| Microbial Fuel Cells [3] | Low (R&D) | 30-50% (Electricity) [3] | Low (specific substrates) | Direct electricity generation; simultaneous waste treatment; currently low power density and high costs [3]. |

Experimental Protocol for Technology Benchmarking

To objectively compare the reliability and performance of different conversion technologies, researchers can employ the following standardized experimental protocol, adapted from systematic review methodologies [8]:

- System Boundary Definition: Delineate the scope of the assessment, typically from feedstock reception to final energy carrier production (e.g., syngas, biogas, electricity).

- Feedstock Standardization: Use a common, characterized feedstock (e.g., a specific woody biomass) across all technologies to isolate technology performance from feedstock variability.

- Data Acquisition: Monitor key operational parameters for a continuous 500-hour run, including:

- Temperature and pressure profiles within the reactor.

- Feedstock throughput (kg/h).

- Output yield (e.g., Nm³ of syngas, m³ of biogas, liters of bio-oil).

- Energy content of the output product (e.g., using bomb calorimetry).

- Downtime events and their causes (e.g., catalyst deactivation, slagging, microbial inhibition).

- Efficiency Calculation: Calculate the net conversion efficiency for each technology using the formula: (Energy in useful outputs / Energy in feedstock) × 100%.

- Reliability Metrics Calculation: Determine key reliability indicators:

- Availability: (Total operational hours / Total test period) × 100%.

- Mean Time Between Failures: Total operational hours / Number of unplanned shutdowns.

This protocol enables a head-to-head comparison of technologies based on empirical data for efficiency, operational stability, and required intervention.

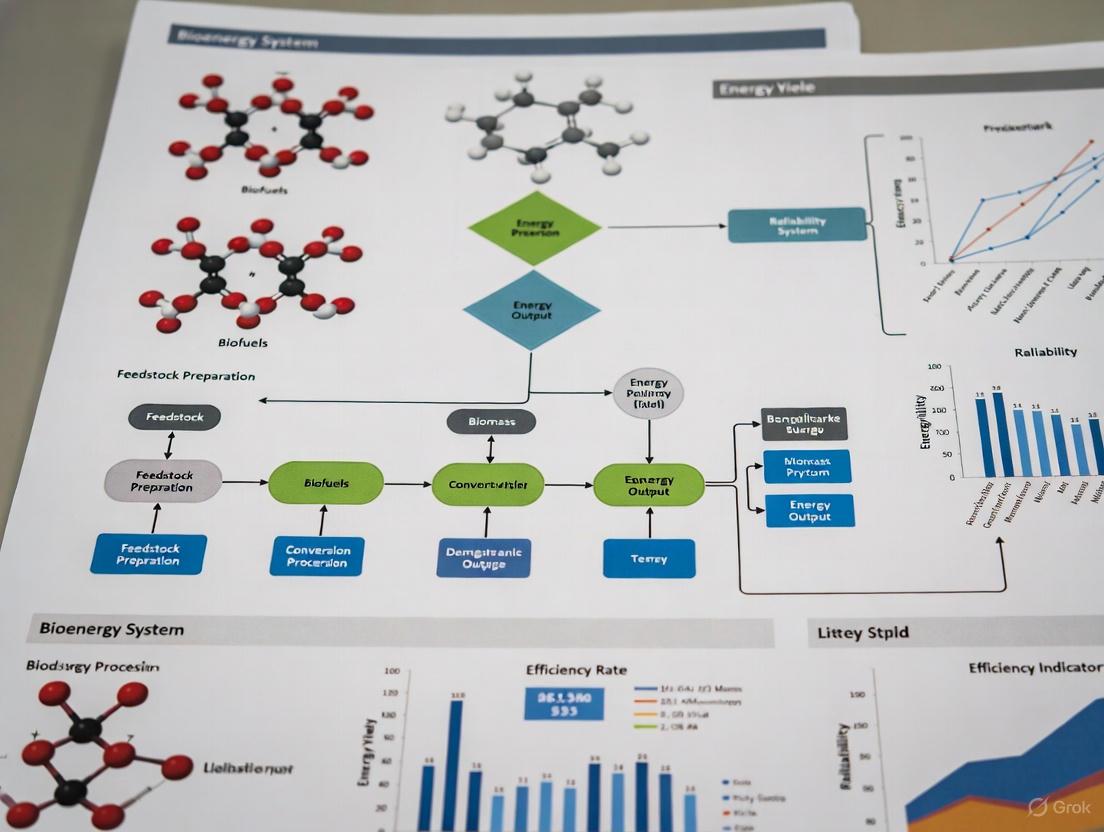

Diagram 1: Bioenergy conversion technology pathways.

System Maintenance and Operational Demands

Maintenance requirements directly influence the long-term reliability, economic viability, and operational burden of a bioenergy system. These demands vary significantly by technology.

Table 3: Maintenance and Operational Demands of Bioenergy Systems

| System Component / Process | Maintenance Intensity | Critical Maintenance Tasks | Impact on Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Combustion Boilers [5] [2] | High | Ash removal, heat exchanger cleaning, emission control system checks [2]. | Ash slagging can cause corrosion and downtime; requires regular shutdowns [5]. |

| Gasification Systems [7] | High | Tar removal from filters and reactors, catalyst replacement, refractory lining inspection. | Tar accumulation is a major cause of blockages and system failure [7]. |

| Anaerobic Digesters [3] [2] | Medium | Mixer and pump maintenance, monitoring of microbial health, digestate removal. | Imbalance in microbial consortium can halt gas production; mechanical mixing is a common point of failure. |

| Fuel Handling & Storage [2] | Low to Medium | Fuel quality monitoring, equipment lubrication, moisture control in storage. | Biomass degradation in storage directly lowers energy output and can cause feeding system jams. |

Quantitative Maintenance Impact Analysis

The financial and temporal costs of maintenance are non-trivial. For residential-scale systems, a typical biomass boiler requires annual servicing costing $200–$400, plus chimney cleaning at $150–$300 annually [2]. Projected over a 25-year system lifespan, cumulative maintenance costs can reach $15,000–$25,000, a figure that must be factored into techno-economic analyses and lifecycle assessments [2]. Furthermore, operational data indicates that wood heating systems can demand 4–8 hours of labor monthly for fuel handling, loading, and ash removal, representing a significant operational burden that impacts perceived reliability [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

For researchers designing experiments to probe the reliability factors discussed, the following reagents and materials are essential.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioenergy Reliability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Research |

|---|---|

| Lignocellulolytic Enzymes | Catalyze the hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars; used to assess biochemical conversion potential and feedstock reactivity [4]. |

| Metal Oxide Catalysts | Accelerate thermochemical reactions (e.g., in gasification, pyrolysis); used to study tar cracking efficiency and syngas quality improvement [4]. |

| Electrogenic Bacteria | Serve as biocatalysts in Microbial Fuel Cells (MFCs) for direct electricity generation from organic substrates; critical for studying bioelectrochemical system stability [3]. |

| Anaerobic Digestion Inoculum | Provides a consortium of microorganisms to initiate and sustain biogas production; essential for biochemical methane potential assays [3]. |

| Standard Gas Mixtures | Used for calibrating gas analyzers (e.g., for CO, H₂, CH₄, CO₂) to ensure accurate measurement of gasification and digestion outputs [7]. |

Diagram 2: Experimental protocol for technology benchmarking.

This comparison guide provides a systematic benchmarking of global bioenergy systems, focusing on their reliability and energy output as of 2025. As nations intensify efforts to decarbonize energy systems, bioenergy has solidified its role as a critical renewable source, providing dispatchable power and renewable heat alongside intermittent solar and wind resources. The analysis that follows objectively compares technological pathways, regional market developments, and performance metrics across the bioenergy sector, supporting researchers and energy professionals in evaluating system reliability and output efficiency. Based on the most current data available, this snapshot captures the state of technological advancement, investment patterns, and sustainability considerations that define the contemporary bioenergy landscape.

- Market Growth: The global biomass power generation market was valued at $90.8 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $116.6 billion by 2030, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.3% [9].

- Power Generation: Global bioenergy electricity generation peaked at 698 TWh in 2024, representing a 3% year-on-year growth, with Asia leading this expansion [10].

- Capacity Installations: Global biopower capacity reached 151 GW in 2024, with Asia's capacity nearly tripling since 2015 [10].

- Transport Biofuels: Liquid biofuels production reached approximately 192 billion liters in 2024, representing 90% of renewable energy in transport and 4% of total transport energy use [10].

- Investment Trends: The International Energy Agency (IEA) predicts a 13% increase in bioenergy investments for 2025, with Europe comprising 60% of global biogas investment in 2024 [10] [11].

Global Bioenergy Capacity Analysis

Regional Capacity Distribution

Bioenergy capacity development shows distinct geographic patterns influenced by resource availability, policy frameworks, and energy security priorities. The table below summarizes the regional distribution of bioenergy capacity and key growth drivers.

Table 1: Regional Bioenergy Capacity and Growth Drivers (2024-2025)

| Region | Biopower Capacity | Key Growth Countries | Primary Feedstocks | Investment Trends |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | Leading global capacity (66 GW in 2020); nearly tripled since 2015 [10] [12] | China (30% of global output), India, Japan [10] [12] | Agricultural residues, municipal solid waste [12] | Major investments in biopower facilities; China accounts for 30% of global output [10] |

| Europe | 32 GW (2020); 75% of global bioheat output [10] [12] | Germany, UK, Sweden, Italy, Poland, Netherlands [12] [13] | Wood pellets, forestry residues, agricultural waste [10] | 60% of global biogas investment (2024); strong policy support [10] |

| North America | 18 GW (2020) [12] | United States, Canada [12] [14] | Corn (ethanol), vegetable oils, animal fats (biodiesel) [14] | Significant investments in liquid biofuels; 15.4B gal ethanol (2022) [14] |

| Emerging Regions | Increasing capacity | Brazil, other Latin American countries [10] | Sugarcane (ethanol), agricultural residues [10] | Rising investments in biogas and ethanol; Brazil as key market [10] |

Technology-Specific Capacity

Bioenergy technologies have evolved along multiple pathways, each with distinct technology readiness levels and conversion efficiencies. The current market includes established first-generation technologies and advancing second-generation systems.

Table 2: Bioenergy Technology Capacity and Conversion Efficiency

| Technology Pathway | Global Production/Capacity | Overall Energetic Efficiency Range | Stage of Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biopower (Combustion) | 151 GW (2024) [10] | 60-80% (with CHP) [13] | Commercial/Established |

| Biopower (Gasification-ICE) | Growing capacity | 50-75% (with CHP) [13] | Demonstration/Commercialization |

| Bioethanol | 15.4 billion gallons (U.S., 2022) [14] | 35-45% (corn), 50-60% (sugarcane) [15] | Commercial/Established |

| Biodiesel/Renewable Diesel | 3.1 billion gallons (U.S., 2022) [14] | 55-65% [15] | Commercial/Established |

| Biomethane/Biogas | 1.76 EJ (2023); 4% generation capacity increase (2023) [10] | 60-75% (upgraded) [15] | Commercial/Expanding |

| Hydrotreated Vegetable Oils (HVO) | Growing production | 65-75% [15] | Commercial/Expanding |

| Lignocellulosic Biofuels | Limited commercial capacity | 40-50% (projected) [15] | Demonstration/R&D |

Market Trends and Investment Landscape

Current Market Valuation and Projections

The biomass power generation market continues to demonstrate robust growth, valued at $90.8 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $116.6 billion by 2030 with a CAGR of 4.3% [9]. This growth trajectory is underpinned by several key factors:

- Policy Support: Government policies supporting renewable energy adoption, including carbon pricing mechanisms and emission reduction targets, are incentivizing industries to shift toward biomass-based power generation [9].

- Technological Advancement: Significant progress in biomass conversion technologies is improving efficiency and reducing costs. Key advancements include advanced gasification processes, torrefaction technology, and integrated carbon capture and storage solutions [9].

- Waste-to-Energy Expansion: Increasing investment in biomass-based waste-to-energy plants addresses growing waste management challenges while generating electricity, aligning with circular economy principles [9].

Investment Patterns

Investment in bioenergy is rising globally, with distinct regional priorities and technology focus areas:

- Liquid Biofuels Leadership: Investments in liquid biofuels are particularly strong, with Brazil and the United States as key markets [10].

- European Biogas Dominance: In 2024, Europe comprised 60% of global biogas investment, reflecting strong policy support and established supply chains [10].

- Overall Investment Growth: The IEA predicts a 13% increase in bioenergy investments for 2025, signaling continued confidence in the sector's growth potential [11].

Benchmarking Bioenergy System Performance

Experimental Framework for System Reliability Assessment

Research into bioenergy system reliability employs standardized experimental protocols and assessment methodologies to enable cross-technology comparisons. The experimental framework typically includes:

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Methodology: Following ISO standards (ISO 14040:2006, ISO 14044:2006), LCA provides a holistic approach for environmental comparison of alternative technologies through four phases: goal and scope definition, life cycle inventory, life cycle impact assessment, and interpretation of results [13].

- System Boundary Definition: Assessments typically include biomass provision (cultivation, harvesting, processing, transportation), biomass conversion (thermochemical or biochemical processes), and cooling systems where applicable [13].

- Functional Unit Standardization: Analyses are normalized to 1 MWh of primary energy product (PEP) to enable equitable comparisons across different system configurations [13].

- Impact Assessment Categories: Multiple environmental impact categories are evaluated, including global warming potential, acidification, eutrophication, and resource depletion [13].

Comparative Technical Performance of Conversion Technologies

The reliability and energy output of bioenergy systems vary significantly based on conversion technology, feedstock characteristics, and system configuration.

Table 3: Performance Benchmarking of Bioenergy Conversion Technologies

| Technology | Electrical Efficiency | Overall Efficiency (with CHP) | Key Reliability Factors | Technology Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Combustion (ORC) | 10-20% [13] | 60-80% [13] | Stable feedstock supply, regular maintenance [12] | Commercial (9) |

| Biomass Gasification-ICE | 20-30% [13] | 50-75% [13] | Gas cleaning system maintenance, feedstock quality control [13] | Demonstration/Commercialization (7-8) |

| Anaerobic Digestion | 30-40% (electrical from CHP) [15] | 75-85% (with thermal use) [15] | Temperature control, feedstock consistency [12] | Commercial (9) |

| Bioethanol Fermentation | N/A | 35-60% (fuel energy output) [15] | Microbial culture health, contamination prevention [15] | Commercial (9) |

Environmental Performance Benchmarking

Comprehensive environmental analysis using Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodology reveals significant variations in environmental impacts across different bioenergy pathways. A comparative LCA of different small-scale biomass-fueled Combined Cooling, Heating, and Power (CCHP) systems shows that:

- The biomass conversion phase (gasification and ORC) contributes most significantly (46-94%) to all environmental impact categories per 1 MWh of primary energy product, followed by the biomass provision phase [13].

- Cooling systems entail only minor environmental burdens (0-22%) across impact categories [13].

- When benchmarked against fossil alternatives, biomass CCHP systems demonstrate significant advantages in climate change impact categories, though they may exhibit higher impacts in other categories such as acidification and eutrophication potential depending on system configuration and feedstock [13].

The following diagram illustrates the systematic benchmarking approach for evaluating bioenergy system reliability and environmental performance:

Research Reagents and Analytical Tools

Standardized analytical procedures and research tools are essential for ensuring comparable results across bioenergy research. The following table details key research solutions used in advanced bioenergy studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Tools for Bioenergy Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application in Bioenergy Research |

|---|---|---|

| NREL Laboratory Analytical Procedures [16] | Standardized methods for biomass composition analysis | Determining cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content in feedstocks |

| CatCost Catalyst Cost-Estimating Tool [16] | Economic evaluation of catalytic processes | Comparing cost-effectiveness of different conversion catalysts |

| ALFABET (Bond Dissociation Energies Estimator) [16] | Prediction of thermodynamics of chemical reactions | Screening potential biomass conversion pathways |

| Bioenergy Scenario Model (BSM) [16] | Policy analysis and scenario modeling | Evaluating impacts of bioenergy policies on market development |

| JEDI Biofuels Models [16] | Economic impact assessment of biofuel plants | Estimating job creation and economic benefits of bioenergy facilities |

| BioFuels Atlas [16] | Geospatial analysis of biomass resources | Mapping biomass availability and optimal plant locations |

| Life Cycle Inventory Databases [13] | Environmental impact data repository | Calculating carbon footprint and other environmental metrics |

Emerging Innovations and Future Outlook

Technological Advancements

Several technological innovations are poised to enhance the reliability and efficiency of bioenergy systems:

- Hybrid Renewable Systems: Integration of biomass with other renewable sources, particularly solar and wind, can provide consistent energy supply when intermittent resources are unavailable [12].

- Advanced Gasification Technologies: Improved gasification processes coupled with efficient gas cleaning systems enhance the viability of biomass gasification for power generation [9] [13].

- Torrefaction Technology: This thermal pretreatment process enhances the energy density and storage capabilities of biomass fuels, producing a material with properties similar to coal [9].

- Artificial Intelligence Applications: AI and machine learning are being deployed to optimize biomass supply chains, predict conversion efficiency, and enhance system reliability [12] [9].

Addressing Research Challenges

Despite substantial advancements, several research challenges persist in bioenergy system optimization:

- Supply Chain Complexity: Effectively utilizing biomass while managing supply chain costs remains a significant challenge, with factors including feedstock availability, transportation expenses, and logistical systems impacting overall efficiency [12].

- Conversion Efficiency Limitations: Current conversion technologies face efficiency barriers, with biochemical routes typically offering lower energy recovery rates compared to thermochemical pathways [12] [15].

- System Integration Challenges: Integrating variable bioenergy sources with existing energy infrastructure requires sophisticated grid management solutions [12].

- Sustainability Measurement: Comprehensive sustainability assessment requires integration of economic, environmental, and social dimensions, with current research often prioritizing economic objectives [12].

The following workflow illustrates the experimental protocol for assessing bioenergy system reliability and environmental performance:

This 2025 snapshot of global bioenergy capacity and market trends demonstrates a sector in transition, balancing established first-generation technologies with emerging advanced bioenergy pathways. With Asia leading capacity growth and Europe dominating investment in biogas, regional specialization reflects local resources, policy priorities, and market structures. The benchmarking analysis reveals significant variations in system reliability and energy output across technological pathways, with gasification-ICE systems generally offering higher electrical efficiency but lower overall efficiency compared to ORC systems when thermal utilization is optimized.

For researchers and industry professionals, these findings highlight several critical considerations. First, technology selection must align with local energy demand patterns—systems with high thermal utilization potential benefit from CHP configurations, while electricity-focused applications may prioritize gasification pathways. Second, sustainability assessments must extend beyond greenhouse gas emissions to include broader environmental impacts and social dimensions. Finally, ongoing innovation in supply chain optimization, conversion efficiency, and system integration will be essential for enhancing bioenergy's contribution to global renewable energy portfolios.

As bioenergy continues to evolve within the broader renewable energy landscape, its unique capacity to provide dispatchable power, utilize diverse feedstocks (including waste streams), and support circular economy principles positions it as a valuable component of comprehensive decarbonization strategies. Future research priorities should focus on enhancing system reliability, reducing costs through technological innovation, and developing integrated sustainability metrics that capture the full spectrum of environmental, economic, and social impacts.

The global transition to a sustainable, low-carbon energy system has positioned biomass energy as a critical renewable resource. The biomass supply chain (BSC) encompasses the integrated processes of sourcing, transporting, processing, and converting organic materials into usable energy products. For researchers and industry professionals, optimizing this supply chain presents complex challenges involving feedstock variability, logistical efficiency, conversion technology selection, and sustainability balancing. The global biomass energy market, valued at $99 billion in 2024, is projected to grow to $160 billion by 2035, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.46% [17]. Parallel growth is observed in specific sectors, with the biomass industrial fuel market expected to expand from $1,856 million in 2025 to $3,316 million by 2031, demonstrating a more robust CAGR of 10.3% [18].

Benchmarking the performance and reliability of these systems requires standardized methodologies for comparing diverse biomass pathways against consistent criteria. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison framework focused on quantitative performance metrics, experimental validation protocols, and systematic analysis of the technological and logistical components that constitute modern bioenergy systems. The critical importance of optimized biomass supply chains is underscored by research indicating that effective utilization must manage costs while addressing feedstock availability, quality, transportation expenses, and complex logistical systems [12].

Biomass Feedstock Profiles and Characteristics

Biomass feedstocks are broadly categorized by origin, composition, and suitability for various conversion pathways. Each feedstock type possesses distinct physical and chemical properties that directly influence energy content, processing requirements, and ultimately, the choice of conversion technology and final energy product.

- Agricultural Residues: This category includes materials such as straw, corn stover, rice husks, and bagasse. They are characterized by their seasonal availability, dispersed geographical distribution, and lower bulk density, which complicates collection and transport. A significant research focus involves optimizing collection systems to avoid conflict with food production and soil health.

- Forestry Residues and Wood Products: This group comprises logging residues (branches, tops), sawdust, and wood pellets from dedicated energy crops. Wood pellets, for instance, are engineered for higher energy density and improved transport efficiency, making them suitable for international markets and co-firing in coal power plants [18] [17].

- Energy Crops: These are plants specifically cultivated for bioenergy production, including fast-growing trees (e.g., willow, poplar) and grasses (e.g., miscanthus, switchgrass). Their key characteristic is higher sustainable yield per hectare, but they require dedicated land and agricultural inputs.

- Organic Wastes: This diverse category encompasses municipal solid waste (MSW), animal manure, and used cooking oil (UCO). Utilizing these feedstocks aligns with waste-to-energy and circular economy principles, reducing landfill use and generating energy from waste streams. The average price of UCO in July 2025 was reported at approximately $1,206 per metric ton, highlighting the economic value of these waste streams [19].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Primary Biomass Feedstocks

| Feedstock Category | Key Examples | Average Energy Density (GJ/ton) | Major Advantages | Major Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Residues | Rice husks, Straw, Corn stover [12] | 12-15 | Abundant, low cost, avoids land-use change | Seasonal, low bulk density, high collection cost |

| Woody Biomass | Wood chips, Pellets, Forestry residues [18] [17] | 16-19 | Higher energy density, established supply chains | Logistics cost, sustainable forestry management |

| Energy Crops | Switchgrass, Miscanthus | 17-19 | High yield potential, dedicated supply | Land use competition, requires agricultural inputs |

| Organic Wastes | MSW, Manure, Used Cooking Oil (UCO) [19] | 10-18 | Waste management benefits, circular economy | Contaminants, heterogeneous composition |

Biomass Conversion Pathways and Performance Metrics

The conversion of raw biomass into final energy products occurs through several distinct technological pathways, each with unique operational parameters, efficiency benchmarks, and suitable applications. The selection of a conversion pathway is a critical decision that depends on feedstock type, desired energy product (e.g., power, heat, liquid fuel), and economic and environmental constraints.

Thermochemical Conversion Pathways

Thermochemical processes use heat and chemical reactions to convert biomass into energy-dense fuels.

- Combustion: This is the most direct and mature method, involving the burning of biomass to produce heat, which can be used directly or to generate electricity via steam turbines. It is widely used in biomass power plants, but its relative simplicity comes with lower conversion efficiency compared to advanced methods.

- Gasification: This process converts biomass into a synthetic gas ("syngas")—a mixture of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and methane—by reacting the feedstock at high temperatures with a controlled amount of oxygen. The syngas can be used to generate electricity in engines or turbines, or it can be cleaned and further processed into liquid biofuels or chemicals. Technological advancements are continuously improving the thermal conversion efficiency of gasification systems [9].

- Pyrolysis: In this pathway, biomass is thermally decomposed in the absence of oxygen to produce liquid bio-oil, solid biochar, and gaseous products. Fast pyrolysis is optimized to maximize the yield of bio-oil, which can be upgraded into heating oil or, with further treatment, into transportation fuels. Innovations in pyrolysis are focused on improving the quality and stability of the bio-oil produced [9].

Biochemical Conversion Pathways

Biochemical processes utilize enzymes and microorganisms to break down biomass.

- Anaerobic Digestion: This process uses microbes in an oxygen-free environment to decompose wet organic materials (e.g., manure, food waste) into biogas (primarily methane and CO2) and digestate. The biogas can be combusted for heat and power or upgraded to biomethane (Renewable Natural Gas) for injection into the gas grid or use as a vehicle fuel. Growth in anaerobic digestion projects is fueling synergies with broader biomass energy systems [9].

- Fermentation: Primarily used for biomass high in sugars or starches (e.g., sugarcane, corn), fermentation employs yeast to produce bioethanol. Second-generation fermentation technologies are being deployed to convert cellulosic biomass into ethanol, overcoming the food-vs-fuel dilemma associated with first-generation biofuels [20].

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking of Biomass Conversion Technologies

| Conversion Technology | Primary Energy Product(s) | Typical Conversion Efficiency | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) | Scale & Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combustion [9] | Heat, Electricity | 20-35% (Power) | 9 (Mature) | Large-scale power plants, industrial heat |

| Gasification [9] | Syngas, Electricity, Biofuels | 30-40% (Power) | 7-9 (Commercial) | Medium-large scale, power & CHP |

| Pyrolysis [9] | Bio-oil, Biochar | 60-75% (Liquid Yield) | 6-8 (Demonstration) | Distributed / centralized bio-oil production |

| Anaerobic Digestion [9] [20] | Biogas (Biomethane) | 40-60% (Biogas Yield) | 9 (Mature) | Farm-scale, wastewater treatment, organic waste |

| Fermentation [20] | Bioethanol | 75-85% (Theoretical Sugar) | 9 (Mature) | Large-scale biofuel production |

Experimental Protocols for Biomass System Analysis

To ensure the reliability and comparability of data used for benchmarking bioenergy systems, researchers must adhere to standardized experimental protocols. These methodologies allow for the objective assessment of feedstock quality, conversion process efficiency, and final fuel properties.

Protocol A: Feedstock Proximate and Ultimate Analysis

Objective: To determine the fundamental composition and energy content of a biomass feedstock sample, which are critical parameters for predicting conversion performance. Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: The biomass sample is air-dried, milled, and sieved to a standardized particle size (e.g., < 1 mm) to ensure homogeneity.

- Proximate Analysis:

- Moisture Content: Measure mass loss after drying at 105°C until constant weight.

- Volatile Matter: Measure mass loss after heating to 950°C in a covered crucible for a set time in the absence of air.

- Ash Content: Measure residual mass after combustion in a muffle furnace at 575°C or 750°C.

- Fixed Carbon: Calculated by difference: 100% - (%Moisture + %Volatile Matter + %Ash).

- Ultimate Analysis: Using specialized instrumentation (e.g., CHNS/O elemental analyzer) to determine the weight percentage of Carbon, Hydrogen, Nitrogen, Sulfur, and Oxygen (by difference).

- Calorific Value: Measure the Higher Heating Value (HHV) using an Isoperibol Oxygen Bomb Calorimeter, following ASTM D5865 or equivalent standard.

Protocol B: Biomass Gasification Efficiency and Syngas Quality Assessment

Objective: To quantify the performance of a gasification process and analyze the composition of the produced syngas. Workflow:

- Reactor Setup: Load a precisely measured mass of prepared feedstock into a fixed-bed or fluidized-bed gasification reactor.

- Process Parameter Control: Set and maintain critical operational parameters: temperature (e.g., 700-900°C), agent (air, steam, or oxygen), and feed rate.

- Syngas Sampling and Analysis: After the reactor reaches steady-state conditions, collect syngas samples. Use Gas Chromatography (GC) with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) to quantify the concentrations of H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, and N₂.

- Data Calculation:

- Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE): Calculate as: (Chemical energy in syngas / Chemical energy in biomass feedstock) × 100%.

- Carbon Conversion Efficiency (CCE): Calculate as: (Carbon in syngas / Carbon in biomass feedstock) × 100%.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and data flow for this experimental protocol.

Experimental Workflow for Gasification Analysis

Quantitative Benchmarking of Final Energy Products

The final products of the biomass supply chain must meet specific quality standards to be viable in the energy market. The table below provides a comparative overview of key biomass-derived energy carriers, benchmarking them against conventional fossil fuels and each other based on key energy and economic metrics.

Table 3: Benchmarking of Biomass-Derived Fuels Against Conventional Alternatives

| Energy Product | Feedstock Origin | Energy Density (MJ/L) | Approx. Price Premium vs Fossil Fuel | Key Applications | Notable Producers/Players |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel Ethanol [20] | Corn, Sugarcane | 23.4 | ~0-50% | Gasoline blending, flex-fuel vehicles | Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Valero, Raízen |

| Biodiesel (FAME) [20] | Vegetable Oils, UCO | 33.0 | ~50-150% | Diesel blending, commercial fleets | Renewable Energy Group (REG), Neste |

| Renewable Diesel (HVO) [20] | Vegetable Oils, Waste Fats | ~34.0 | ~100-200% | Drop-in replacement for diesel | Neste, Valero (Diamond Green) |

| Biomethane / RNG [20] | Landfill, Manure, Waste | 35.8 (as CNG) | ~50-150% | Pipeline gas, heavy-duty transport | Archaea Energy, Aemetis, Brightmark |

| Wood Pellets [18] [17] | Forest Residues, Wood | ~17-18 (MJ/kg) | Varies by market | Power generation (co-firing), heating | Enviva, Pinnacle, Graanul Invest |

| Conventional Gasoline | Crude Oil | 34.2 | (Baseline) | Light-duty vehicles | - |

| Conventional Diesel | Crude Oil | 38.6 | (Baseline) | Heavy-duty transport, machinery | - |

The data reveals significant trends and challenges. For instance, bio-naphtha, a byproduct of renewable diesel and Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) production, maintained a price premium of $800-$900/mt over fossil naphtha in the second half of 2025 [19]. Similarly, bio-olefins like bio-ethylene and bio-propylene can be priced at two to three times their fossil-based equivalents, constraining their use to niche, high-value applications [19]. These premiums highlight the critical challenge of economic competitiveness faced by many biomass-derived products in the absence of strong regulatory mandates or carbon pricing mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Research and development in biomass supply chains and conversion technologies rely on a suite of specialized reagents, catalysts, and analytical materials. The following table details essential items for a laboratory focused on bioenergy system optimization.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioenergy Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Typical Specification/Purity |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymes (Cellulase, Hemicellulase) | Catalyze the hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars in biochemical pathways. | ≥ 90% activity, filtered |

| Methanogenic Inoculum | Provides the microbial consortium for initiating and maintaining anaerobic digestion processes. | Active digestate from a stable biogas reactor |

| Gasification Agent (O₂, Steam) | The reactive medium in a gasifier; determines syngas composition (e.g., O₂ for higher CO/H₂, steam for higher H₂). | Industrial grade (O₂), Ultra-pure (Steam) |

| Catalysts (Zeolites, Ni-based) | Accelerate chemical reactions in thermochemical processes (e.g., cracking, reforming) to improve bio-oil quality or syngas composition. | Varies (e.g., ZSM-5, Ni/Al₂O₃), >98% |

| Analytical Gases (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) | Used for calibration of Gas Chromatographs (GC) and other analyzers for accurate quantification of gas composition. | Certified calibration standard mixes |

| Solvents (Dichloromethane, Acetone) | Used for extraction of bio-oil components, cleaning reactor systems, and sample preparation for analysis. | HPLC Grade, >99.9% purity |

| Elemental Analysis Standards | Certified reference materials for calibrating CHNS/O analyzers to ensure accurate elemental composition data. | Certified, traceable to NIST |

Integrated Biomass Supply Chain Workflow

A holistic view of the biomass supply chain is essential for identifying optimization points and bottlenecks. The entire process, from biomass cultivation to the delivery of the final energy product, involves multiple interconnected stages, each with its own technological choices and logistical requirements. The integration of digital technologies and AI is emerging as a key trend to optimize logistics, feedstock matching, and overall supply chain efficiency [21] [17].

Integrated Biomass to Energy Workflow

This guide has provided a structured framework for benchmarking biomass supply chains, from diverse feedstocks to a variety of final energy products. The quantitative data, experimental protocols, and comparative tables presented allow researchers and industry professionals to objectively assess the performance, reliability, and economic viability of different bioenergy pathways. The steady market growth and ongoing technological innovations, particularly in areas like Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), advanced biofuels, and AI-driven logistics optimization, underscore the dynamic nature of this field [17].

The key to advancing bioenergy lies in addressing persistent challenges such as feedstock supply chain consistency, conversion efficiency, and the high cost premiums of many bio-products. Future research must continue to focus on integrated optimization approaches that enhance the economic, environmental, and social sustainability of the entire biomass energy system, solidifying its role in the global transition to a clean energy future.

The pursuit of sustainable and reliable bioenergy systems necessitates a critical evaluation of the raw materials at its foundation: biomass feedstocks. The characteristics of these feedstocks—ranging from their chemical composition to their physical properties—profoundly influence the efficiency, yield, and environmental footprint of energy conversion processes. Within the context of benchmarking bioenergy system reliability and energy output, selecting the appropriate feedstock is not merely a preliminary step but a determinant factor in the technological and economic viability of the entire energy production chain. This guide provides an objective comparison of key biomass feedstocks, focusing on their inherent properties and their resultant impact on energy conversion performance, supported by quantitative data and standardized experimental protocols. As the global biomass power generation market progresses, projected to grow from US$90.8 billion in 2024 to US$116.6 billion by 2030, such a comparative analysis becomes indispensable for researchers and industry professionals aiming to optimize bioenergy systems [22].

Feedstock Classification and Key Characteristics

Biomass feedstocks can be broadly categorized based on their origin and suitability for different generations of biofuel production. First-generation feedstocks, primarily food crops like maize and sugarcane, have faced criticism for creating a "food-versus-fuel" dilemma [23]. Consequently, research has pivoted towards advanced, non-food based feedstocks. Second-generation feedstocks, derived from lignocellulosic materials such as agricultural residues (e.g., corn stover, wheat straw), forestry residues, and dedicated energy crops (e.g., switchgrass, miscanthus), are characterized by their abundance and non-competition with food supply chains [23] [24]. Third-generation feedstocks primarily encompass algae, noted for their high lipid content and rapid growth rates without requiring arable land [23] [24]. A emerging category, sometimes termed fourth-generation, involves genetically modified feedstocks or processes designed for carbon-negative bioenergy through integrated carbon capture [23].

The suitability of a feedstock for a specific conversion pathway is largely dictated by its biochemical and physical composition. Key characteristics include:

- Lignocellulosic Content: The proportions of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin determine the recalcitrance of the biomass to biochemical breakdown and its suitability for thermochemical processes [23].

- Moisture Content: High moisture content favors biochemical pathways like anaerobic digestion, while thermochemical processes like combustion and gasification require drier feedstocks [24].

- Energy Density: This affects the overall energy output and logistics; for instance, torrefaction and pelletization are pre-treatment methods used to enhance energy density [22] [24].

- Ash Content and Composition: High ash content can lead to slagging and fouling in thermal conversion systems, reducing efficiency and increasing maintenance [24].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between major feedstock categories and their primary conversion pathways, highlighting the diversity of usage routes in the bioenergy landscape.

Comparative Analysis of Feedstock Performance

A critical step in benchmarking bioenergy systems is the direct comparison of feedstock performance across standardized metrics. The following tables synthesize experimental data on energy output, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and utilization costs associated with different feedstock categories and conversion technologies. This data, derived from life cycle assessment (LCA) and techno-economic analysis (TEA) studies, provides a foundation for objective evaluation [25] [24].

Table 1: Energy Output and GHG Performance by Feedstock Category and Conversion Technology

| Feedstock Category | Specific Example | Conversion Technology | Energy Output (MJ/kg feedstock) | GHG Emissions (kg CO₂eq/MJ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crop Residue | Corn Stover | Gasification | 10.5 - 15.8 | 0.010 - 0.025 |

| Forest Residue | Pine Bark | Combustion | 12.0 - 14.5 | 0.008 - 0.020 |

| Animal Manure | Cattle Manure | Anaerobic Digestion | 0.1 - 0.5 | 0.015 - 0.035 |

| Municipal Food Waste | Organic Fraction MSW | Anaerobic Digestion | 0.5 - 1.2 | 0.020 - 0.045 |

| Woody Biomass | Wood Chips | Pyrolysis | 15.0 - 18.0 | 0.005 - 0.015 |

| Algae | Microalgae (Lipid-extracted) | Hydrothermal Liquefaction | 8.0 - 12.0 | 0.050 - 0.100 |

Table 2: Economic and Operational Metrics for Selected Feedstocks

| Feedstock | Estimated Pre-treatment Cost (USD/ton) | Utilization Cost (USD/MJ) | Technology Readiness Level (TRL) | Key Operational Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood Chips | 20 - 40 | 0.01 - 0.03 | 9 (Mature) | High moisture variability |

| Corn Stover | 30 - 60 | 0.02 - 0.04 | 7-8 (Demonstration) | Low bulk density, collection logistics |

| Animal Manure | 10 - 25 | 0.03 - 0.06 | 9 (Mature) | High moisture, low energy density |

| Municipal Food Waste | 40 - 80 | 0.04 - 0.08 | 8 (Commercial) | Feedstock contamination, variability |

| Switchgrass | 25 - 50 | 0.02 - 0.05 | 7-8 (Demonstration) | Seasonal harvesting, storage losses |

| Algae | 100 - 300 | 0.08 - 0.15 | 5-6 (Pilot) | High capital and operational costs |

Data in Table 1 indicates that thermochemical pathways like gasification and pyrolysis generally yield higher energy output per kilogram of feedstock compared to biochemical pathways like anaerobic digestion [25]. However, biochemical pathways can be more suitable for wet feedstocks like manure and food waste. Table 2 highlights the economic trade-offs, showing that while mature technologies like wood chip combustion have lower costs, emerging feedstocks like algae face significant economic hurdles [25] [24]. A key insight from recent European energy system modeling is that the value of biogenic carbon for negative emissions (via BECCS) or as a feedstock for e-fuels can be higher than its value for pure bioenergy provision, which can reshape feedstock prioritization [26].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure the reliability and reproducibility of biomass conversion data, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following sections outline detailed methodologies for two key types of analyses used in benchmarking feedstock performance.

Protocol for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Biomass Feedstocks

1. Goal and Scope Definition:

- Objective: To quantify and compare the environmental impacts of different biomass feedstocks from cradle-to-grave.

- Functional Unit: Define a basis for comparison, typically 1 Megajoule (MJ) of net energy output or 1 kilogram of biofuel produced [24].

- System Boundaries: Include all stages: feedstock cultivation/harvesting, transportation, pre-processing, conversion to energy, and end-use. Emissions from land-use change must be considered if applicable.

2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI):

- Data Collection: Compile quantitative data on all energy and material inputs and environmental releases for each stage within the system boundary.

- Feedstock Production: Document inputs like fertilizers, pesticides, water, and diesel fuel for agricultural operations. For residues, use allocation methods to partition impacts from the primary product.

- Conversion Process: Use mass and energy balance data from pilot or commercial-scale plants. Key parameters include conversion efficiency, catalyst consumption, and emissions of CO2, CH4, N2O, SOx, NOx, and particulates.

3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA):

- Impact Categories: Calculate the potential impacts in selected categories, most critically Global Warming Potential (GWP) over a 100-year horizon, expressed in kg CO2-equivalent per functional unit [25].

- Calculation: Apply standardized characterization factors (e.g., from the IPCC) to the LCI data to aggregate emissions into impact category scores.

4. Interpretation:

- Sensitivity Analysis: Identify the most influential parameters (e.g., feedstock yield, conversion efficiency, transport distance) and assess the robustness of the results by varying these parameters [24].

- Uncertainty Analysis: Evaluate the uncertainty in the final results to provide a confidence interval for the comparisons.

Protocol for Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) of Conversion Pathways

1. Process Modeling and Design:

- Basis: Develop a detailed process flow diagram for the biomass conversion pathway (e.g., gasification + Fischer-Tropsch synthesis).

- Mass and Energy Balance: Use simulation software (e.g., Aspen Plus) or engineering calculations to model the complete process, ensuring mass and energy conservation. This yields key performance data such as overall energy efficiency and product yields.

2. Capital Cost Estimation:

- Equipment Costs: Estimate the purchase cost of all major equipment (reactors, pumps, turbines, etc.).

- Total Capital Investment (TCI): Calculate the TCI by summing the installed equipment costs (using installation factors) and adding costs for indirect capital, land, and working capital.

3. Operating Cost Estimation:

- Fixed Operating Costs: Include labor, maintenance, overhead, and insurance.

- Variable Operating Costs: The most significant is typically the feedstock cost. Also include costs for catalysts, utilities (water, electricity), and waste disposal [24].

4. Economic Analysis:

- Minimum Selling Price (MSP): Calculate the MSP of the bioenergy product (e.g., USD per liter of biofuel or USD per MWh of electricity) required for the project to achieve a specified rate of return (e.g., 10%) over its lifetime.

- Uncertainty and Risk Analysis: Perform a Monte Carlo analysis or sensitivity analysis on key variables (e.g., feedstock price, product value, capital cost) to understand the economic risks and drivers of the project's viability [24].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental benchmarking of biomass feedstocks relies on a suite of specialized reagents, analytical standards, and software tools. The following table details key items essential for researchers in this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Biomass Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NREL LAPs | Provides standardized laboratory analytical procedures for biomass composition (e.g., determining structural carbohydrates and lignin). | Essential for ensuring reproducible quantification of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content [23]. |

| ANSI/ASABE S593 | Standard for defining and classifying solid biofuels, including terminology and specifications. | Critical for consistent reporting of feedstock physical properties like particle size and moisture content. |

| LCA Software (e.g., OpenLCA, SimaPro) | Software platforms used to model life cycle inventory data and calculate environmental impact assessments. | Enables systematic and standardized comparison of the environmental footprint of different feedstocks and pathways [24]. |

| Process Simulation Software (e.g., Aspen Plus) | Used for rigorous process modeling, mass/energy balancing, and preliminary techno-economic analysis of conversion pathways. | Allows for in-silico optimization of process parameters before pilot-scale testing. |

| Syngas Analysis Standards | Certified gas mixtures (CO, H₂, CO₂, CH₄, N₂) for calibrating analyzers (e.g., GC-TCD) during gasification experiments. | Ensures accurate measurement of syngas composition and yield, key metrics for process efficiency. |

| Lipid Extraction Solvents | Chloroform-methanol mixtures used in standardized methods (e.g., Bligh & Dyer) for quantifying lipid content in algal biomass. | Vital for assessing the biofuel potential of third-generation algal feedstocks [24]. |

| Anaerobic Digestion Inoculum | A metabolically active consortium of microorganisms used to initiate and maintain the anaerobic digestion process in biochemical methane potential tests. | The source and activity of the inoculum must be standardized to ensure comparable results across different labs. |

The Role of Bioenergy in Achieving Net-Zero Emissions and Grid Stability

Bioenergy, derived from organic materials known as biomass, is a cornerstone of global strategies to achieve net-zero emissions and enhance grid stability. As a renewable and versatile energy source, it directly supports the decarbonization of energy systems and provides a reliable, dispatchable power supply that complements variable renewables like solar and wind [12] [23]. The modern bioenergy sector has experienced significant growth; in 2022, it accounted for 5.8% of global total final energy consumption (TFEC), with notable increases in the transport and industrial sectors [27]. Projections suggest the global biomass market will expand from USD 134.76 billion in 2022 to exceed USD 210.5 billion by 2030 [12].

This guide objectively compares the performance of different bioenergy pathways—including solid biomass, liquid biofuels, and biogas—against conventional fossil fuels and other renewable alternatives. The analysis is framed within a broader thesis on benchmarking bioenergy system reliability and energy output, providing researchers and scientists with quantitative data, standardized experimental protocols, and essential toolkits for evaluating bioenergy systems.

Bioenergy Pathways and Technology Comparison

Bioenergy can be produced from a diverse range of feedstocks and converted into various forms of energy through multiple technological pathways. Second-generation feedstocks, such as agricultural residues (e.g., straw, husks) and forestry by-products (e.g., wood chips, sawdust), are particularly advantageous as they do not compete with food production and promote waste valorization in a circular economy [23]. Third-generation feedstocks, primarily algae, offer high photosynthetic efficiency and carbon capture capabilities, while emerging fourth-generation approaches aim for carbon-negative bioenergy through integrated carbon capture and storage (BECCS) [28] [23].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Bioenergy Conversion Pathways and Outputs

| Conversion Pathway | Feedstock Examples | Primary Energy Outputs | Key Process Parameters | Typical Energy Yield/ Efficiency | Grid Stability Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical (Anaerobic Digestion) | Animal manure, organic waste, energy crops | Biogas (CH₄, CO₂) | Temperature (35-55°C), pH (6.5-7.5), retention time (20-40 days) | ~50-60% conversion efficiency [23] | High (Dispatchable baseload) |

| Thermochemical (Combustion/Gasification) | Wood chips, agricultural residues, biocoal | Heat, Electricity, Syngas (CO, H₂) | Gasification temp: 800-1200°C; Equivalence ratio: 0.2-0.3 [23] | Electrical efficiency: 20-35% [12] | High (Dispatchable, schedulable) |

| Biochemical (Fermentation) | Sugarcane, corn, lignocellulosic biomass | Bioethanol, Biohydrogen | Temperature (30-35°C), specific microorganism strains (e.g., S. cerevisiae) | Bioethanol: ~400 L/ton dry biomass [23] | Medium (Liquid fuel for storage) |

| Thermochemical (Pyrolysis) | Algal biomass, wood waste | Bio-oil, Biochar, Syngas | Pyrolysis temp: 400-600°C; heating rate: 10-100°C/s [28] | Bio-oil yield: 50-75 wt% [28] | Medium (Energy densification) |

| Algae-Based CCUS | Microalgae (e.g., Chlorella, Spirulina) | Biodiesel, Biogas, Bioethanol | Light intensity: 150-200 µmol/m²/s; CO₂ concentration: 5-15% [28] [29] | CO₂ fixation: 0.3-1.2 g/L/day [29] | Variable with integration |

Table 2: Global Production and Capacity Metrics for Key Bioenergy Types (2023-2024)

| Bioenergy Type | Global Production/Capacity | Key Countries/Regions | Remarks & Trends |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Biofuels | 175.2 billion litres (2023) | Brazil, USA, Indonesia, India | 7% increase from 2022; Blending mandates (e.g., B35 in Indonesia, E20 in India) driving growth [27] |

| Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) | 1.8 billion litres (2024) | USA, EU, Indonesia, South Korea | 200% increase from 2023; Still only 0.53% of aviation fuel demand [27] |

| Biopower Capacity | 150.8 GW (2024) | China, France, USA, Brazil | Record increase of 4.6 GW in 2024; China and France each added 1.3 GW [27] |

| Biogas | 15,789 ktoe (2023, EU) | Germany, Italy, France | 6% increase in Europe (2023); Germany leads with ~50% of EU production [27] |

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected pathways of bioenergy production from feedstock to final energy application, highlighting its role in carbon cycling and grid stability:

Bioenergy Production Pathways and Climate Benefits

Experimental Protocols for Bioenergy System Benchmarking

Protocol for Algal Biomass Carbon Sequestration Efficiency

Objective: Quantify CO₂ fixation rates and biomass yield of microalgae strains under controlled conditions.

Materials:

- Photobioreactors (e.g., 5 L tubular or flat-panel)

- Selected microalgae strains (Chlorella vulgaris, Scenedesmus obliquus)

- Air pumps with CO₂ mixing system (0.03-15% CO₂)

- Artificial lighting system (150-200 µmol/m²/s)

- Analytical equipment: pH meter, spectrophotometer, dry weight oven

Methodology:

- Inoculum Preparation: Grow algae in BG-11 medium to late exponential phase.

- System Setup: Fill reactors with 4 L sterilized medium; inoculate to initial optical density (OD680) of 0.1.

- Environmental Control: Maintain temperature at 25±2°C; provide continuous illumination; aerate with air mixture containing 5%, 10%, and 15% CO₂ (v/v) for test groups, with ambient air (0.04% CO₂) as control.

- Monitoring: Daily measurements of OD680 and pH. Sample (50 mL) collected every 48 hours for dry weight analysis.

- Analysis:

- Biomass concentration: Determine via dry weight (filter through pre-weighed 0.45µm membrane, dry at 105°C to constant weight).

- CO₂ fixation rate: Calculate using formula: ( R{CO₂} = (Xt - X0) \times Cc \times (M{CO₂}/MC) / t ) where ( Xt ) and ( X0 ) are final and initial biomass (g/L), ( C_c ) is carbon content (~50%), ( M ) is molar mass, and ( t ) is time [28] [29].

Protocol for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Bioenergy Systems

Objective: Evaluate environmental impact of bioenergy systems, focusing on global warming potential (GWP) and non-renewable energy demand.

Materials:

- LCA software (SimaPro, OpenLCA)

- Background databases (ecoinvent, Agri-footprint)

- Process inventory data (feedstock production, conversion, transport)

Methodology:

- Goal and Scope: Define functional unit (e.g., 1 MJ energy delivered, 1 km driven).

- System Boundaries: Include all stages from biomass cultivation to energy conversion and distribution (cradle-to-grave).

- Inventory Analysis: Collect data on material/energy inputs, emissions, and waste flows for each process.

- Impact Assessment: Calculate impact categories using standardized methods (e.g., ReCiPe 2016, IPCC GWP 100a).

- Interpretation: Identify hotspots and improvement opportunities through sensitivity analysis [30] [31].

Table 3: Key Inventory Data for LCA of Different Bioenergy Feedstocks

| Input/Output | Jatropha Biodiesel (per km driven) | Algae Biodiesel (per km driven) | Fossil Diesel (per km driven) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Inputs | Fertilizer: 0.02-0.05 g N/P/K; Water: 10-50 L (irrigated) | Fertilizer: 0.1-0.3 g N/P; Water: 15-25 L (closed system) | - |

| Direct Emissions | CO₂: 8-25 g (biogenic); NOx: 0.1-0.3 g; PM: 0.01-0.05 g | CO₂: 5-15 g (biogenic); NOx: 0.05-0.2 g; PM: 0.005-0.03 g | CO₂: 85-120 g (fossil); NOx: 0.3-0.6 g; PM: 0.02-0.08 g |

| Land Use | 0.5-2.0 m²a | 0.1-0.5 m²a (photobioreactor) | 0.05-0.2 m²a (infrastructure) |

| GWP (CO₂ eq.) | 15-50% reduction vs. fossil diesel [31] | 40-80% reduction vs. fossil diesel [28] | Baseline (100%) |

| Non-Renewable Energy Demand | 20-60% reduction vs. fossil diesel [31] | 30-70% reduction vs. fossil diesel [28] | Baseline (100%) |

Grid Integration and Stability Analysis

Bioenergy provides distinct advantages for grid stability through its dispatchability and reliability compared to variable renewable sources. In 2024, renewables met two-thirds of increased global power demand, but fossil fuels continued to fill gaps, pushing CO₂ emissions up by 0.8% [32]. Bioenergy's role in grid stability includes:

- Biomass power plants provide baseload and dispatchable generation, mitigating intermittency of solar and wind power. Global biopower capacity reached 150.8 GW in 2024, a record 4.6 GW increase from 2023 [27].

- Hybrid renewable systems combine biomass with solar/wind, using bioenergy as a controllable source when variable generation is low. Advanced smart grids employ demand response and energy storage for optimal integration [33].

- Biopower in developing regions enhances energy access and grid reliability. In sub-Saharan Africa, decentralized biomass systems provide electricity where grid access is limited (only 14% in rural Mali) [30].

The following diagram illustrates bioenergy's role in a stable, integrated renewable grid:

Bioenergy Integration in Renewable Electricity Systems

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bioenergy System Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algae Growth Media (BG-11) | Contains NaNO₃, K₂HPO₄, MgSO₄·7H₂O, CaCl₂·2H₂O, citric acid, microelements | Algal biomass cultivation for carbon capture and biofuel production | Provides essential macronutrients and micronutrients for optimized algae growth and lipid production [28] [29] |

| Arbuscular Mycorrhizal (AM) Fungi | Rhizophagus irregularis or similar species | Bioenergy crop cultivation trials | Forms mutualistic associations with plant roots, enhancing nutrient/water uptake and reducing fertilizer requirements [31] |

| Anaerobic Digestion Inoculum | Granular sludge from operational biogas plants | Biochemical methane potential tests | Provides microbial consortium (hydrolytic, acidogenic, acetogenic, methanogenic bacteria) for efficient biomass conversion to biogas [23] |

| Lipase Enzymes | Candida antarctica Lipase B (immobilized) | Biodiesel production via transesterification | Catalyzes conversion of algal/plant lipids to fatty acid methyl esters (biodiesel) under mild conditions [23] |

| Gas Chromatography System | Equipped with FID/TCD detectors, capillary columns | Biofuel composition and quality analysis | Quantifies and identifies volatile compounds in biofuels (e.g., fatty acid profiles in biodiesel, methane content in biogas) [31] |

Bioenergy systems present a viable pathway for achieving net-zero emissions and enhancing grid stability through multiple technological pathways. Quantitative benchmarking demonstrates significant life cycle advantages, including 40-80% GWP reduction for algae-based biofuels compared to fossil diesel and substantial contributions to dispatchable power capacity [28] [27]. However, challenges in supply chain optimization, conversion efficiency, and land-use impacts require continued research using the standardized protocols and tools outlined.

Future advancements hinge on integrating bioenergy with other renewables in smart grids, developing carbon-negative bioenergy through BECCS, and optimizing sustainable feedstock use. For researchers, focusing on algal carbon capture efficiency, LCA standardization, and hybrid renewable system modeling will be crucial for maximizing bioenergy's role in a comprehensive net-zero strategy.

Advanced Tools and Techniques for System Optimization

Mathematical Modeling for Biomass Supply Chain Optimization

Mathematical modeling is paramount for optimizing the complex, multi-stage logistics of biomass supply chains (BSCs), which are critical for advancing renewable bioenergy. This guide provides a comparative analysis of predominant modeling paradigms—from traditional operations research methods to emerging artificial intelligence (AI) techniques. It benchmarks their performance in addressing core optimization challenges, including cost minimization, logistical efficiency, and resilience to disruptions. Supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, this review serves as a strategic resource for researchers and industry professionals in selecting and deploying appropriate modeling frameworks for robust and economically viable bioenergy systems.

The biomass supply chain encompasses a sequence of interconnected activities, from the collection of raw materials like forestry residues and agricultural waste to their transportation, storage, preprocessing, conversion into energy or biofuels, and final distribution [34] [35]. The inherent complexities of these chains, such as biomass seasonality, geographical dispersion of resources, and quality variations, present significant technical and economic challenges. Logistical costs, particularly for transportation, can constitute the majority of the total supply chain expense, often determining the economic feasibility of biomass exploitation [35] [36].

Mathematical modeling provides a structured framework to navigate this complexity, enabling stakeholders to make informed strategic and tactical decisions. The primary objectives of BSC optimization models include maximizing profit, minimizing total cost, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and enhancing supply chain resilience against disruptions [34] [36]. Over the years, the modeling landscape has evolved from deterministic linear programming to sophisticated techniques that handle uncertainty, non-linearity, and the integration of real-time data, including the recent adoption of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) [37] [38].

Comparative Analysis of Modeling Approaches

This section benchmarks the performance of different modeling methodologies used in biomass supply chain optimization. The comparison is structured based on the models' objectives, solution methods, and their ability to handle real-world constraints.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Optimization Approaches

| Modeling Approach | Primary Objective | Key Strengths | Typical Computational Complexity | Reported Cost Reduction/ Efficiency Gain | Handling of Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | Profit maximization, cost minimization [39] | High solution quality for well-defined problems; clear optimality gaps [39] | High for large-scale instances [39] | Used for strategic network design [39] | Requires robust or stochastic extensions [36] |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Maximizing profit from energy sales [36] | Effective for complex, non-linear problems [35] | Moderate to High [36] | Outperformed SA with 2.9% better deviation in a case study [36] | Heuristic search can handle parameter variability |

| Simulated Annealing (SA) | Maximizing profit from energy sales [36] | Good convergence properties; avoids local optima [35] | Moderate to High [36] | Effective for large-scale problems [36] | Heuristic search can handle parameter variability |

| Tabu Search (TS) | Logistics cost optimization [35] | Effective for combinatorial routing problems [35] | Moderate | Applied to minimize operational costs in an integrated manner [35] | Can incorporate memory to avoid cycling |

Table 2: Comparison of AI and Integrated Modeling Approaches

| Modeling Approach | Primary Application | Key Strengths | Reported Predictive Accuracy / Performance | Data Requirements | Handling of Uncertainty |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) | Biomass delivery prediction, supplier selection [38] | Handles dynamic, non-linear, and incomplete data [38] | High predictive accuracy (MAE=0.16, MSE=0.02, R²=0.99) [38] | Can function with incomplete datasets [38] | Highly adaptable to dynamic market conditions [38] |

| Modular ANN for Biomass Delivery | Procurement and supply optimization for CHP plants [38] | Integrates technical, economic, and geographic parameters [38] | Identified cost-effective and quality-compliant sources [38] | Robust to data scarcity in biomass markets [38] | Supports real-time logistics decisions [38] |

| Matheuristic (Fix-and-Optimize) | MILP model for demand selection & supply chain planning [39] | Significantly reduces computational time while preserving solution quality [39] | Validated on a real-world case study [39] | Based on MILP model requirements | Improves planning under uncertainty [39] |

| Multi-stage Stochastic Programming | Design of resilient supply chain networks [36] | Explicitly models and mitigates disruption risks [36] | Improved network resilience [36] | High (requires probability distributions of disruptions) | Core feature of the methodology |

Key Performance Insights from Experimental Data

- AI vs. Traditional Methods: A case study on a Polish CHP plant demonstrated that an ANN-based Biomass Delivery Management model achieved a high predictive accuracy with a mean absolute error of 0.16 and an R² of 0.99, effectively optimizing supplier selection and transport routes with incomplete data [38].

- Heuristic Performance: In a supply chain design problem considering disruptions, a direct comparison showed that a Genetic Algorithm provided better solutions than Simulated Annealing, with a 2.9% lower deviation from the optimal benchmark [36].

- Computational Efficiency: For complex MILP models incorporating demand selection, a fix-and-optimize matheuristic strategy was shown to drastically reduce computational time while maintaining high solution quality, making it practical for real-world applications [39].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for benchmarking, this section outlines the standard experimental protocols for developing and validating the discussed models.

Protocol for Developing AI-Based Predictive Models (e.g., ANN)

This protocol is based on the methodology described for the ANN-based Biomass Delivery Management model [38].

- Data Collection and Preprocessing: Gather historical operational data from a biomass-fired CHP plant. Key input variables include biomass type, supplier location, unit price, moisture content, calorific value, transport distance, and annual demand.

- Model Architecture Design: Design a modular artificial neural network. The structure typically includes an input layer, one or more hidden layers with non-linear activation functions, and an output layer predicting metrics like delivery cost or quality compliance.

- Model Training and Validation: Split the dataset into training and testing subsets. Train the ANN using algorithms like backpropagation. Validate the model's predictive performance against the test set using metrics such as Mean Absolute Error, Mean Squared Error, and the R-squared coefficient.

- Model Deployment and Decision Support: Integrate the trained model into a decision-support system. Use it for real-time tasks such as supplier selection, route optimization, and inventory planning based on dynamic input parameters.

ANN Development Workflow

Protocol for Multi-Objective Resilient Supply Chain Design

This protocol is derived from models that incorporate sustainability and disruption risks [36].

- Problem Scoping and Parameter Definition: Define the supply chain network, including biomass fields, collection hubs, biorefineries, and demand points. Identify potential disruption scenarios and sustainability criteria.

- Mathematical Model Formulation: Develop a multi-objective Mixed-Integer Linear Programming model. The objective functions typically aim to maximize total profit while minimizing environmental impact and accounting for disruption risks.

- Algorithm Selection and Solution: Employ metaheuristics such as Genetic Algorithms or Simulated Annealing to solve the complex model. Tune the algorithm parameters for optimal performance.

- Scenario Analysis and Validation: Test the model with various problem sizes and disruption scenarios. Compare algorithm performance using deviation metrics and validate the solution's robustness and economic viability.

Resilient Supply Chain Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

In the context of mathematical modeling for BSCs, "research reagents" refer to the core computational tools, software, and data resources essential for building, testing, and validating optimization models.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Biomass Supply Chain Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Category | Primary Function in BSC Modeling | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Digestion Model No. 1 (ADM1) | Biochemical Process Model | Simulates complex biochemical reactions in anaerobic digesters to predict biogas output [40]. | Modeling biogas production from manure; estimating electricity and heat generation potential [40]. |

| Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) Solver | Optimization Software | Solves complex optimization problems with discrete and continuous variables to find optimal network designs [39]. | Strategic facility location, transportation planning, and demand selection [39]. |

| Genetic Algorithm & Simulated Annealing | Metaheuristic Framework | Finds high-quality solutions for complex, non-linear, or NP-hard problems where exact methods are infeasible [36]. | Solving large-scale, multi-objective supply chain models under disruption [36]. |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Library | Machine Learning Tool | Builds predictive models that learn from data to forecast costs, optimize routes, and manage inventory [38]. | Biomass delivery management, supplier selection, and real-time logistics decision support [38]. |

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | Spatial Analysis Tool | Integrates real-time spatial data for route optimization and facility location analysis [38]. | Analyzing biomass availability, transport routes, and optimal placement of collection hubs. |

| Techno-Economic Databases | Data Resource | Provides reliable cost, efficiency, and performance parameters for energy technologies [41]. | Informing model parameters for economic feasibility studies and life-cycle assessments. |

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for Strategic Biomass Logistics

The strategic logistics of biomass feedstock present a formidable challenge for the bioenergy sector, directly influencing system reliability, energy output, and economic viability. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) have emerged as a critical technology for optimizing these complex supply chains, integrating spatial data on resource availability, transportation networks, and infrastructure placement. Within the context of benchmarking bioenergy system reliability, GIS provides the spatial intelligence necessary to transform dispersed, variable biomass resources into predictable, consistent energy feedstocks. This guide objectively compares the performance of various GIS-based methodological frameworks and their alternatives for biomass logistics planning, providing researchers and scientists with validated experimental data and protocols to inform their bioenergy system designs.

Comparative Analysis of GIS Methodologies for Biomass Assessment

Different GIS methodological approaches offer varying advantages for specific biomass logistics challenges. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, performance metrics, and optimal use cases for several prominent approaches documented in recent scientific literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of GIS-Based Methodologies for Biomass Logistics

| Methodology | Spatial Analysis Technique | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Data Requirements | Optimal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|