Advanced Strategies for Addressing Slagging and Fouling in Biomass Boilers: Mechanisms, Mitigation, and Modeling

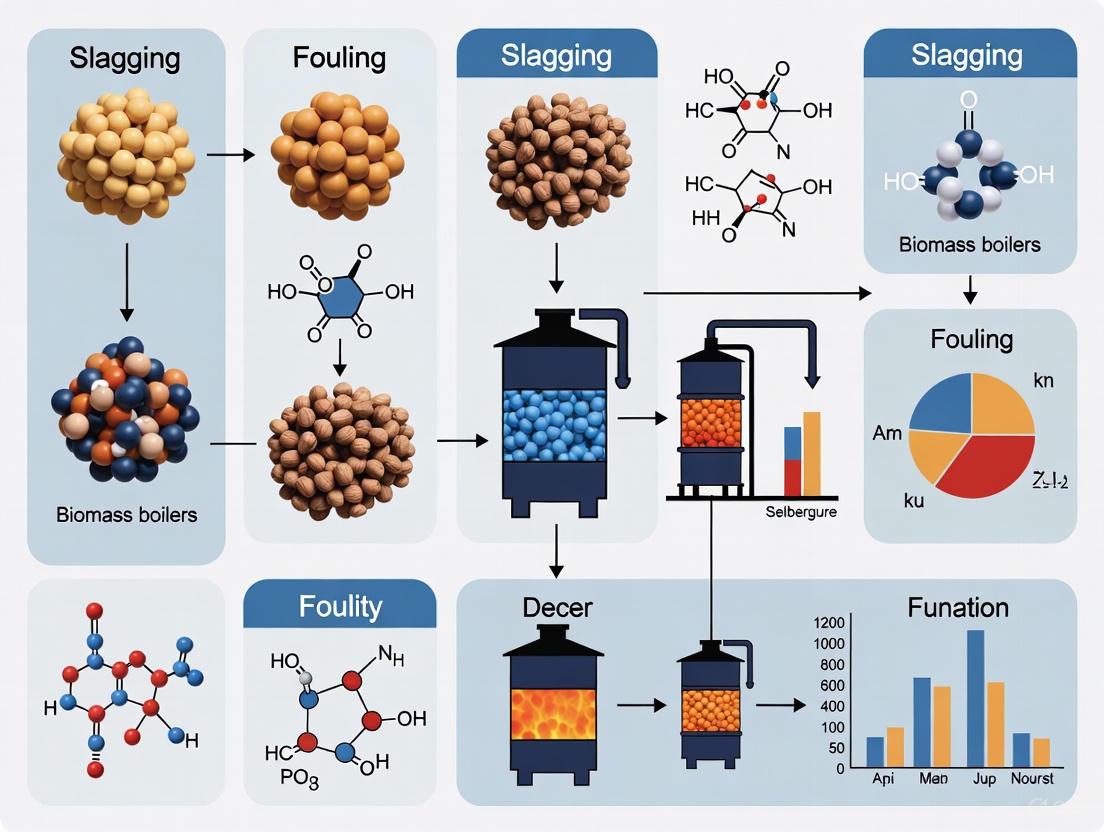

This comprehensive review addresses the persistent operational challenges of slagging and fouling in biomass boilers, which compromise combustion efficiency and system reliability.

Advanced Strategies for Addressing Slagging and Fouling in Biomass Boilers: Mechanisms, Mitigation, and Modeling

Abstract

This comprehensive review addresses the persistent operational challenges of slagging and fouling in biomass boilers, which compromise combustion efficiency and system reliability. We systematically examine the fundamental thermochemical mechanisms governing ash deposition, focusing on alkali metal, chlorine, and sulfur interactions. The article evaluates practical mitigation methodologies including fuel preprocessing, aluminosilicate additives, and advanced control systems. Through comparative analysis of predictive indices, computational modeling approaches, and real-world case studies, we provide researchers and engineers with validated frameworks for optimizing boiler performance and durability. The synthesis of current research highlights emerging trends in hybrid mitigation strategies and intelligent control systems for sustainable biomass energy integration.

Understanding Ash Transformation Mechanisms: The Science Behind Slagging and Fouling

For researchers investigating slagging and fouling in biomass boilers, understanding ash composition is not merely a preliminary step but the foundation of predictive and mitigation strategies. Biomass ash is a complex inorganic-organic mixture with extremely variable composition, directly influencing deposition behavior, corrosion potential, and overall boiler efficiency [1]. This technical resource provides targeted methodologies and data to support your experimental work in characterizing ash properties and addressing the technological challenges associated with different biomass fuel types.

FAQ: Understanding Biomass Ash Fundamentals

What defines the basic chemical composition of biomass ash?

Biomass ash is primarily composed of major elements including silicon (Si), calcium (Ca), potassium (K), phosphorus (P), aluminum (Al), magnesium (Mg), and iron (Fe), along with minor elements and heavy metals [1] [2] [3]. These elements are typically expressed and analyzed as their oxide forms (e.g., SiO₂, CaO, K₂O, P₂O₅) after complete combustion [2]. The composition is highly variable, but when recalculated on a dry ash-free basis, many characteristics show relatively narrow ranges [3].

Why does biomass ash composition vary so significantly across different fuel types?

The variability stems from multiple factors, including the biological origin of the biomass (woody, agricultural, animal waste), cultivation conditions (soil type, fertilizers), climate, and contamination during harvesting or processing [2] [4]. Agricultural residues and animal-origin biomass typically contain significantly higher ash content with different elemental distributions compared to clean woody biomass [2].

How is biomass ash classified based on its chemical composition?

Researchers often classify biomass ashes using identified systematic chemical associations [1] [5]. A widely used classification system defines four main types:

- S-type: Rich in Si, with significant Al, Fe, Na, and Ti (mostly glass, silicates, and oxyhydroxides)

- C-type: Dominated by Ca, with Mg and Mn (commonly carbonates, oxyhydroxides, and silicates)

- K-type: Rich in K, with P, S, and Cl (typically phosphates, sulphates, chlorides, and glass)

- CK-type: Contains characteristics of both C and K types [5]

Experimental Protocols for Ash Analysis

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Ash Composition Analysis

Purpose: To determine the elemental composition of biomass ash for slagging and fouling prediction.

Materials and Methods:

- Sample Preparation: Dry biomass samples at 105°C until constant weight is achieved. Pulverize to a fine powder (<250 μm) to ensure homogeneity [6].

- Ashing: Convert biomass to ash using a standardized procedure (e.g., ASTM D3174) in a muffle furnace at 575±25°C [7].

- Elemental Analysis:

- X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF): Prepare pressed powder pellets of the ash and analyze using XRF spectroscopy to determine major oxide compositions (SiO₂, Al₂O₃, Fe₂O₃, CaO, MgO, K₂O, etc.) [7].

- Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) Techniques: For higher sensitivity analysis of trace elements, digest ash samples with acid and analyze using ICP-OES or ICP-MS [7].

- Mineral Phase Analysis:

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Identify crystalline mineral phases in the ash using XRD with Cu-Kα radiation. Scan typically from 5° to 80° 2θ [7].

- SEM-EDS: Examine ash morphology and perform semi-quantitative microanalysis using Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy [7] [6].

Protocol 2: Ash Fusion Temperature Determination

Purpose: To evaluate the melting behavior of biomass ash, which directly correlates with slagging propensity.

Materials and Methods:

- Ash Preparation: Create ash pyramids from the prepared biomass ash according to standard methods (e.g., ASTM D1857) [6].

- Instrumentation: Use an ash fusion analyzer equipped with a camera and image processing software.

- Testing Procedure: Heat ash pyramids in both oxidizing (air) and reducing (60% CO, 40% CO₂) atmospheres at a controlled rate to a maximum of 1500°C [6].

- Key Temperature Measurements: Record four critical temperatures through image analysis:

- Initial Deformation Temperature (DT): First rounding of ash pyramid edges.

- Softening Temperature (ST): Ash pyramid height equals width (ash fusion temperature).

- Hemispherical Temperature (HT): Ash forms a hemisphere (height = ½ width).

- Fluid Temperature (FT): Ash spreads out in a layer (height ≤ 1.6 mm) [6].

Protocol 3: Drop-Tube Furnace Combustion for Slagging/Fouling Simulation

Purpose: To simulate ash deposition behavior under controlled laboratory conditions that mimic industrial boilers.

Materials and Methods:

- Fuel Preparation: Dry and pulverize biomass fuels to particle sizes below 250μm [7] [6].

- Combustion System: Utilize a laboratory-scale drop-tube furnace (DTF) with controlled temperature zones (typically 1050-1300°C) and a cooled probe to simulate heat exchanger tubes [7] [6].

- Deposit Collection: Introduce pulverized fuel into the DTF at a controlled feed rate (e.g., 0.3 g/min). Collect ash deposits on the temperature-controlled probe over a specified duration [7].

- Deposit Analysis: Quantify deposit weight, then analyze morphology (SEM), composition (EDS), and mineralogy (XRD) to understand deposition mechanisms [7] [6].

Data Tables: Composition and Properties Across Biomass Types

Table 1: Inorganic Element Distribution in Major Biomass Categories

Table summarizing the typical ash content and major oxide composition ranges for different biomass categories, based on peer-reviewed data compilation [1] [2] [3].

| Biomass Category | Ash Content (% dry basis) | SiO₂ (%) | CaO (%) | K₂O (%) | P₂O₅ (%) | Cl (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woody Biomass (wood chips, pellets) | 0.5 - 2 | 15 - 40 | 15 - 40 | 5 - 15 | 2 - 10 | 500 - 2000 |

| Agricultural Residues (straw, rice husk) | 4 - 20 | 40 - 80 | 2 - 10 | 10 - 30 | 1 - 5 | 2000 - 15000 |

| Animal Waste (poultry litter) | 10 - 60 | 10 - 25 | 15 - 35 | 10 - 25 | 10 - 25 | 5000 - 25000 |

| Sewage Sludge | 20 - 50 | 20 - 40 | 5 - 15 | 1 - 5 | 10 - 30 | 1000 - 10000 |

Table 2: Key Slagging and Fouling Indices for Biomass Ash Evaluation

Table of empirical indices used to predict ash-related problems from ash composition data [8] [6].

| Index Name | Formula | Interpretation Threshold | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base-to-Acid Ratio | (Fe₂O₃ + CaO + MgO + K₂O + Na₂O)/(SiO₂ + Al₂O₃ + TiO₂) | <0.5: Low slagging; 0.5-1.0: Medium; >1.0: High | Slagging propensity |

| Slagging Index | Rₛ = (B/A) × S (S=%S in dry ash) | <0.6: Low; 0.6-2.0: Medium; 2.0-2.6: High; >2.6: Severe | Slagging tendency |

| Fouling Index | R₍ = (B/A) × (Na₂O + K₂O) | <0.2: Low; 0.2-0.5: Medium; 0.5-1.0: High; >1.0: Severe | Fouling tendency |

| Bed Agglomeration Index | (K₂O + Na₂O)/(SiO₂ + Al₂O₃) | Higher values indicate increased agglomeration risk | Fluidized bed combustion |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomass Ash Analysis

Essential materials and their functions for experimental investigation of biomass ash properties.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Muffle Furnace | Controlled ashing of biomass samples | Standardized ash preparation for composition analysis |

| XRF Spectrometer | Quantitative elemental analysis of major oxides | Bulk ash composition determination |

| ICP-OES/MS | Trace element and heavy metal analysis | Environmental risk assessment and catalytic effect studies |

| XRD Diffractometer | Crystalline phase identification | Mineral transformation studies during combustion |

| SEM-EDS System | Morphological and micro-area compositional analysis | Ash deposit mechanism investigation |

| Ash Fusion Analyzer | Determination of ash melting behavior | Slagging propensity prediction |

| Drop-Tube Furnace (DTF) | Laboratory-scale simulation of combustion conditions | Controlled study of ash deposition mechanisms |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent ash fusion temperature results

- Potential Cause: Variations in ashing temperature or atmosphere during sample preparation.

- Solution: Strictly control ashing conditions (575±25°C) and use consistent pyramid preparation methods. Ensure proper atmosphere (oxidizing/reducing) during AFT testing [6].

Problem: Unexpectedly severe slagging in experimental combustion

- Potential Cause: High alkali metal content (especially K) combined with silica and low melting point eutectics.

- Solution: Pre-test using slagging indices. For high-risk fuels, consider blending with additives (e.g., kaolin, dolomite) or other biomass with high Si/Al content to increase ash fusion temperatures [7].

Problem: Rapid corrosion of experimental probes

- Potential Cause: High chlorine content in biomass leading to active oxidation.

- Solution: Select probe materials with higher corrosion resistance for high-Cl fuels. Implement surface temperature control to avoid condensation of alkali chlorides [6].

Problem: Poor reproducibility in drop-tube furnace deposition experiments

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent particle size distribution or feeding rate fluctuations.

- Solution: Standardize biomass grinding and sieving procedures. Use calibrated feeders and maintain constant feeding rates throughout experiments [7].

Biomass Ash Behavior and Research Methodology

This technical support resource synthesizes current research methodologies and data to assist in your investigation of biomass ash-related challenges. The provided protocols, classification systems, and troubleshooting guides are designed to enhance the reproducibility and effectiveness of your experimental work in addressing slagging and fouling in biomass boilers.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the primary mechanism through which potassium contributes to slag formation? During biomass combustion, potassium (K) is released as gaseous species (KCl, KOH, K₂SO₄). These vapors interact with silicon dioxide (SiO₂) present in the ash to form potassium silicates (e.g., K₂O·nSiO₂). These silicates have low melting points and form a sticky, molten phase that captures other ash particles, leading to the formation of compact and strong deposits on heat exchange surfaces [9] [10] [11].

How does the combustion temperature affect potassium-silicate slagging? Temperature directly influences the severity of slagging. At temperatures above 700°C, there is a significant formation of silicate eutectic compounds [10]. As the temperature increases from 1050°C to 1300°C, dystectic solid compounds are transformed into eutectic compounds with even lower melting points, intensifying ash slagging and deposition [7].

Are some biomass types more prone to potassium-silicate slagging? Yes, biomass with high potassium and silicon content is particularly prone. Agricultural residues (e.g., cotton stalk, straw) often have high potassium and chlorine contents, making them major contributors to this issue. These are classified as K-type biomass ash in ternary phase diagrams [10] [11] [7]. Woody biomass typically has lower slagging tendency compared to agricultural residues.

What are the most effective methods to mitigate potassium-silicate slagging? Effective mitigation strategies include:

- Using aluminosilicate additives (e.g., kaolin, coal fly ash) which capture gaseous potassium into high-melting-point compounds like kalsilite (KAlSiO₄) [9] [11].

- Fuel pre-treatment such as water leaching to remove soluble potassium and chlorine before combustion [10].

- Operational controls like limiting combustion temperature and using suitable excess air levels [7].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Severe Slagging and Fouling in Biomass Combustor

1. Initial Assessment and Symptom Identification

- Symptom: Rapid buildup of hard, sintered deposits on heat exchanger tubes or furnace walls.

- Symptom: Reduced thermal efficiency and increased pressure drop.

- Quick Check: Analyze your biomass fuel's ash composition. High K₂O and SiO₂ content indicates high risk [9] [11].

2. Diagnostic Procedure

Follow this logical workflow to diagnose the root cause of severe slagging.

3. Mitigation Strategies

Based on the diagnosed root cause, implement the following solutions.

| Root Cause | Primary Mitigation Strategy | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| High K/Si Fuel | Fuel Blending or Pre-treatment | Blend with low-K fuel (e.g., coal) or implement water leaching of raw biomass [10] [7]. |

| Excessive Temperature | Operational Adjustment | Lower combustion temperature to below 700°C if possible, to avoid intensive silicate eutectic formation [10] [7]. |

| Molten Silicate Deposition | Use of Additives | Introduce aluminosilicate additives (e.g., Kaolin) to capture potassium into high-melting KAlSiO₄ [9] [11]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Results in Slagging Experiments

1. Initial Assessment: Verify fuel and additive preparation protocols. Inconsistent fuel particle size, moisture content, or additive mixing can cause significant variance [12] [13].

2. Diagnostic Checklist:

- Fuel Preparation: Is biomass dried, pulverized, and sieved to a consistent particle size (e.g., <400 μm)? [9]

- Additive Mixing: Are additives (e.g., kaolin) thoroughly and homogenously blended with the fuel before feeding? [9]

- Probe Conditioning: Are deposition probes cleaned and conditioned consistently before each experimental run to ensure comparable surface characteristics?

3. Solution: Implement and strictly adhere to a standardized Fuel and Additive Preparation Protocol.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Laboratory-Scale Deposition Test Using a Drop-Tube Furnace

This method is suitable for simulating deposit formation and studying slagging tendencies under controlled conditions [7].

1. Objectives

- To simulate ash deposition behavior during biomass combustion.

- To collect and analyze deposits for composition and morphology.

2. Materials and Equipment

- Drop-tube furnace (DTF)

- Pulverized biomass fuel (sieved to <100 μm for biomass, <80 μm for coal if co-firing)

- Specimen probes (air-cooled or uncooled) for deposit collection

- Scanning Electron Microscope with Energy Dispersive X-ray (SEM-EDX)

- X-ray Diffractometer (XRD)

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1 (Fuel Prep): Dry biomass samples at 55°C for 3+ hours. Pulverize and sieve to desired particle size [7].

- Step 2 (Combustion): Feed the prepared fuel into the pre-heated DTF at a controlled rate (e.g., 0.3 g/min). Maintain desired combustion temperature (e.g., 1050-1300°C) and excess air coefficient [7].

- Step 3 (Deposit Collection): Insert a deposition probe into the hot flue gas stream for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-60 minutes) to collect ash deposits [9] [7].

- Step 4 (Sample Analysis):

Protocol 2: Evaluating Mitigation Effectiveness of Additives

This protocol assesses the performance of slagging mitigation additives like kaolin.

1. Objectives

- To determine the effectiveness of an additive in reducing deposit formation.

- To analyze changes in deposit chemistry and morphology.

2. Materials and Equipment

- Same as Protocol 1, plus the selected additive (e.g., kaolin, coal fly ash).

3. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 1 (Blend Preparation): Homogeneously mix the biomass fuel with a predetermined proportion of additive (e.g., 1-5% by weight) [9].

- Step 2 (Combustion & Deposition): Follow the same combustion and deposit collection steps as in Protocol 1, using the fuel-additive blend.

- Step 3 (Comparative Analysis): Compare the mass, tenacity, composition, and morphology of deposits from tests with and without the additive. Effective additives will change deposit morphology from molten to particulate and reduce the concentration of problematic potassium chlorides/silicates [9].

The following table consolidates critical data from research on alkali metal interactions and slagging.

| Parameter / Parameter | Key Finding / Value | Impact on Slagging |

|---|---|---|

| Critical Temperature | >700°C [10] | Formation of low-temperature silicate eutectics intensifies. |

| K₂O in Problematic Ash | High concentration (Significant component) [9] [10] | Primary driver for potassium silicate formation. |

| Additive Effectiveness | Kaolin captures K as KAlSiO₄ (kalsilite) [9] [11] | Increases ash fusion temperature beyond 1300°C. |

| Water Leaching Efficacy | Ash yield reduction up to 55.58% [10] | Significantly inhibits ash formation and slagging tendency. |

| SiO₂/K₂O Ratio in Ash | Low ratio (e.g., in K-type ash) [11] [14] | Indicates high slagging potential due to excess reactive K. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Kaolin (Al₂Si₂O₅(OH)₄) | Aluminosilicate additive; captures gaseous K species to form high-melting KAlSiO₄ & KAlSi₂O₆ [9] [11] | Transforms to meta-kaolin upon dehydroxylation; effective at >900°C. |

| Coal Fly Ash | Alternative aluminosilicate additive; provides SiO₂ and Al₂O₃ to react with potassium [9] | Abundant by-product; cost-effective. |

| Simulated Biomass Fuels | Model fuels with controlled K, Cl, Si content for systematic study [9] [7] | Enables isolation of specific variable impacts. |

| Deionized Water | For water leaching pre-treatment of biomass to remove soluble K and Cl [10] | Reduces initial alkali and chlorine content in fuel. |

For researchers and scientists dedicated to advancing biomass combustion, the challenges of slagging and fouling are significant barriers to efficient and reliable system operation. These phenomena are primarily governed by the complex thermochemical behavior of inorganic elements, particularly chlorine and sulfur, present in biomass fuels. During combustion, these elements undergo intricate volatilization-condensation cycles, transforming from solid fuel constituents into gaseous compounds that subsequently condense on heat exchanger surfaces, leading to the formation of problematic deposits [11]. The core issue lies in the interaction of alkali metals (K, Na) with chlorine and sulfur, forming compounds with depressed melting points that facilitate ash deposition, reduce heat transfer efficiency, and accelerate high-temperature corrosion [7] [11]. A mechanistic understanding of these pathways is therefore fundamental to developing effective mitigation strategies for biomass combustion systems.

Fundamental Pathways: Chlorine and Sulfur Chemistry

The Chlorine-Driven Slagging Pathway

Chlorine plays a pivotal role in the initial release and transport of alkali metals. In biomass combustion, potassium (K) and sodium (Na) are frequently present as water-soluble chloride salts (e.g., KCl, NaCl) within the fuel matrix [15] [11].

- Volatilization: Upon combustion, these alkali chlorides exhibit high volatility, vaporizing at temperatures above 700°C. They are released into the flue gas stream as gaseous KCl(g) and NaCl(g) [15] [11].

- Condensation and Deposit Formation: As the flue gas cools upon contact with heat exchanger surfaces (e.g., superheaters), these gaseous alkali chlorides condense directly onto metal surfaces or onto the surface of entrained fly ash particles. This condensation forms a sticky layer that captures incoming ash particles, initiating deposit growth [11].

- Corrosion Initiation: The condensed chlorides react with the protective oxide layer (e.g., Fe₂O₃) on superheater metals, leading to active oxidation and severe high-temperature corrosion [11].

The Sulfur Interaction and Transformation Pathway

Sulfur's behavior is complex, existing in both organic and inorganic forms within biomass. Its pathway interacts critically with the chlorine cycle, influencing the final deposit chemistry.

- Volatilization: During pyrolysis and combustion, organic sulfur is released at lower temperatures (<500°C), while inorganic sulfur decomposes at higher temperatures. A significant portion of sulfur is released into the gas phase as SO₂, and to a lesser extent, H₂S and COS [15].

- Sulfation Reaction: A key mitigating reaction occurs when gaseous SO₂ interacts with condensed alkali chlorides on deposit surfaces. This sulfation reaction converts KCl (and NaCl) into alkali sulfates (K₂SO₄, Na₂SO₄), releasing gaseous HCl [11].

- Impact on Deposit Properties: This transformation is crucial because alkali sulfates have higher melting points and are less sticky and corrosive than their chloride counterparts. Therefore, the presence of sufficient sulfur can, to some extent, alleviate the severe slagging and corrosion caused by alkali chlorides [11].

The interplay of these pathways is summarized in the following diagram, which illustrates the sequential volatilization, condensation, and transformation processes that govern deposit formation.

Experimental Data and Slagging Indices

Empirical research has quantified the impact of fuel composition and operating conditions on slagging severity. The following table synthesizes key experimental findings from drop-tube furnace studies and compositional analysis, providing a reference for researchers to assess slagging propensity.

Table 1: Experimental Data on Fuel Composition and Slagging Behavior

| Fuel / Condition | Key Parameter | Observed Effect on Slagging/Deposition | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cotton Stalk | High K & Cl content | Most severe agglomeration vs. rice husk/sawdust | [7] |

| Cotton Stalk Blend | Increased proportion (10% to 30%) | K in ash increased; agglomeration became more serious | [7] |

| Combustion Temperature | Increase (1050°C to 1300°C) | Transformation to eutectic compounds with lower m.p. | [7] |

| Agricultural Residues | Inorganic Cl (as KCl) | Chlorine only partly released during pyrolysis | [15] |

| Colza Straw Char | S association with Ca | Sulfur found as CaSO₄/CaS in char | [15] |

| Kaolin Additive | Aluminosilicate addition | Ash Fusion Temp elevated beyond 1300°C | [11] |

Beyond specific experiments, the field relies on predictive indices derived from ash composition to estimate a fuel's slagging and fouling propensity. These indices offer a convenient preliminary assessment tool for researchers [8].

Table 2: Common Predictive Indices for Slagging and Fouling Propensity

| Index Name | Basis of Calculation | General Interpretation | Applicability to Biomass |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base-to-Acid Ratio (B/A) | (Fe₂O₃ + CaO + MgO + K₂O + Na₂O) / (SiO₂ + Al₂O₃ + TiO₂) | Higher ratio indicates greater slagging propensity | Requires careful translation from coal |

| Alkali Index | (Kg K₂O + Na₂O) per GJ of fuel | >0.3 indicates high fouling/firing risk | Directly relevant for biomass |

| Silica Ratio | SiO₂ / (SiO₂ + Fe₂O₃ + CaO + MgO + Na₂O) | Lower ratio suggests higher slagging tendency | Applicable, but thresholds may differ |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Analytical Methods

To effectively study these pathways, a standard set of analytical techniques and reagents is required. The following toolkit outlines the critical components for experimental research in this domain.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item / Reagent | Function in Experimentation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Drop-Tube Furnace (DTF) | Simulates high-temp combustion conditions & particle time-temperature history | Validating deposition models; studying initial ash formation [16] [7] |

| Kaolin (Al₂Si₂O₅(OH)₄) | Aluminosilicate additive that captures volatile K via KAlSiO₄ formation | Mitigating slagging by elevating AFT and sequestering alkali vapors [11] |

| X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) | Identifies crystalline mineral phases in ash and deposits | Determining if K is present as KCl, K₂SO₄, or K-silicates [7] |

| SEM-EDX | Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-ray analysis | Visualizing deposit morphology and mapping elemental composition [7] |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) | Quantitative analysis of major inorganic elements in fuel and ash | Precise measurement of K, Na, Ca, Mg, Al, Si, P concentrations [7] [15] |

| Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA) | Measures ash shrinkage as a function of temperature, indicating softening | Predicting particle stickiness for CFD deposition models [16] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: In our co-combustion experiments, why does adding a small proportion (20%) of agricultural residue like cotton stalk to coal dramatically increase deposition rates, even though the overall ash content is lower? This occurs due to the synergistic interaction between coal and biomass ash. Biomass ash is often rich in volatile alkali chlorides (KCl), while coal ash typically contains higher levels of silica and alumina. Upon co-combustion, the gaseous KCl can condense and react with the aluminosilicates from the coal ash to form low-temperature eutectic mixtures (e.g., K-aluminosilicates), which have melting points significantly lower than those of the individual components from either fuel alone. This phenomenon means that slagging propensity is not a linear function of blend ratio and can be severe even at low biomass blending percentages [7].

Q2: What is the most effective method to mitigate chlorine-induced slagging and high-temperature corrosion: using a high-sulfur fuel blend or introducing an aluminosilicate additive? While both methods can be effective, introducing an aluminosilicate additive (e.g., kaolin) is generally considered superior. The sulfation reaction (where SO₂ converts KCl to the less problematic K₂SO₄) is limited by gas-solid contact and kinetics, and it still produces deposits (albeit less sticky ones). Kaolin actively captures potassium vapor in the gas phase or on particle surfaces through a chemical reaction that forms refractory kalsilite (KAlSiO₄), effectively removing the alkali from the volatilization-condensation cycle and elevating the ash fusion temperature beyond 1300°C [11].

Q3: During our pyrolysis experiments, why is a significant fraction of chlorine from agricultural residues (e.g., colza straw) retained in the char, while it is almost completely released from materials like PVC? The release mechanism is dictated by the initial chemical form of chlorine in the feedstock. In PVC, chlorine is present as organic chlorine (C-Cl bonds), which is thermally unstable and readily released as HCl gas at relatively low temperatures. In agricultural residues, chlorine is primarily present as inorganic chloride salts like KCl. These salts have higher vaporization temperatures and can be trapped within the char matrix or interact with other inorganic elements (e.g., K⁺ association with the organic structure), leading to only partial release during pyrolysis [15].

Q4: Our computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model for deposit formation is inaccurate. What is a critical input parameter we might be overlooking? A common oversight is using an oversimplified model for particle stickiness. Rather than assuming a fixed capture efficiency, integrate a stickiness criterion based on thermomechanical analysis (TMA) data or the melt fraction of the ash particles. The TMA shrinkage curve, which can be fitted to a function of temperature, provides a more accurate representation of the particle's softening behavior upon impact. Implementing this via a User-Defined Function (UDF) can significantly improve the prediction of deposition rates and locations in CFD simulations [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Ash Fusion Temperature (AFT) Depression and why is it a critical issue in biomass combustion?

AFT depression refers to the significant lowering of the temperature at which biomass ash begins to melt and form slag, compared to coal ash. This occurs primarily due to the high concentration of alkali metals (Potassium - K, and Sodium - Na) and other fluxing elements in biomass [17] [18]. These elements form low-melting point eutectic mixtures during combustion. For instance, the presence of potassium can lead to the formation of compounds like potassium aluminosilicates which melt at temperatures as low as 764°C, far below typical furnace operating temperatures [18] [19]. This is a critical operational problem because it leads to slagging on furnace walls and fouling on heat exchanger surfaces, which reduces boiler efficiency, increases maintenance costs, and can cause unscheduled shutdowns [18].

2. Which biomass components have the greatest influence on lowering the Ash Fusion Temperature?

The key components that depress AFT are alkali oxides (K₂O, Na₂O) and alkaline earth metal oxides (CaO, MgO), which act as fluxing agents. Conversely, acidic oxides such as SiO₂ and Al₂O³ tend to increase the ash melting temperature [20]. The base-to-acid ratio (Rb/a) is a crucial indicator, where a higher ratio generally predicts a lower AFT [20]. The synergistic effect between alkali metals in biomass (e.g., K) and other elements like chlorine (Cl), sulfur (S), silicon (Si), and aluminum (Al) from coal during co-firing further accelerates the formation of sticky, low-melting-point deposits [19].

3. What are the standard methods for determining Ash Fusion Temperature, and what do the different measured points signify?

The standard ash fusion test involves heating a prepared ash cone under specific atmospheric conditions (either oxidizing or reducing) and visually determining four characteristic temperatures [6] [21]:

- Initial Deformation Temperature (IDT or DT): The temperature at which the first signs of rounding of the cone's edges occur.

- Softening Temperature (ST): The temperature at which the cone fuses and its height becomes equal to its width.

- Hemispherical Temperature (HT): The temperature at which the cone forms a hemisphere (height equals half the base width).

- Flow Temperature (FT): The temperature at which the ash spreads out into a flat layer.

For biomass ashes, the Initial Deformation Temperature (IDT) is often considered the most critical performance metric [21].

4. How can the slagging and fouling propensity of a biomass fuel be predicted from its ash composition?

Researchers use several empirical indices derived from the fuel's ash composition to predict slagging and fouling tendencies. The following table summarizes key indices and their interpretations [6]:

Table 1: Empirical Indices for Predicting Slagging and Fouling

| Index Name | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Base-to-Acid Ratio (Rb/a) | (Fe₂O₃ + CaO + MgO + Na₂O + K₂O) / (SiO₂ + Al₂O₃ + TiO₂) | A higher ratio (>0.5) indicates a higher tendency for slagging and fouling. |

| Silica Ratio | SiO₂ / (SiO₂ + Fe₂O₃ + CaO + MgO) | A lower ratio suggests a higher slagging propensity. |

| Alkali Index | (kg K₂O + Na₂O) / GJ fuel | An index > 0.3 indicates a high probability of fouling. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Low Ash Fusion Temperature in Herbaceous Biomass

Problem: During combustion tests of herbaceous biomass (e.g., kenaf, straw, rice husks), severe slagging is observed at unexpectedly low temperatures, damaging the experimental setup.

Investigation Procedure:

- Confirm Ash Composition: Perform X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis on the biomass ash. Check for high concentrations of Potassium (K) and Silicon (Si). Herbaceous biomass often has high K₂O and SiO₂ content [18].

- Check for Chlorine: Analyze the fuel's chlorine content. High chlorine facilitates the vaporization of alkali metals, which subsequently condense on cooler heat exchanger surfaces as chlorides and sulfates, initiating fouling [18] [19].

- Calculate Empirical Indices: Use the ash composition data to calculate the Base-to-Acid Ratio (Rb/a) and Alkali Index. Compare them against the thresholds in Table 1.

- Identify Low-Melting Phases: Use X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) on ash deposits to identify specific low-melting-point minerals. Look for phases like KalSi₃O₈ (Potassium Aluminum Silicate) or Ca(Al₂Si₂O₈) (Calcium Aluminum Silicate), which can form from the reaction of biomass alkali with Si and Al, potentially from coal or soil contamination [19].

Solution: Consider pre-treating the biomass fuel. Ashless biomass technology, which involves leaching the raw biomass with mild acid or water, can effectively extract alkali metals and chlorine, thereby increasing the AFT and reducing slagging and fouling propensity [17].

Guide 2: Addressing Ash Deposition During Co-firing Experiments

Problem: When co-firing coal with biomass in a drop tube furnace (DTF), rapid ash deposition occurs on the probe, simulating fouling on superheater tubes.

Investigation Procedure:

- Analyze Deposit Morphology and Composition: Use Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS) on the deposited ash. Look for:

- Melted and Sintered Particles: Indicate temperatures exceeded the ash melting point.

- Fine Particles Acting as "Glue": In coal-dominated combustion, fine particles can cement larger particles to the surface [22].

- Key Elements: High concentrations of K, Cl, S, and Ca in the deposits suggest they are key drivers [19].

- Vary Blending Ratio: Systematically test different biomass-coal blending ratios. Co-firing can sometimes inhibit deposit formation, but high biomass ratios (>50%) may aggravate it, especially under oxy-fuel conditions [22].

- Determine Capture Efficiency (CE): Calculate the CE from the deposition mass in the DTF. A high CE indicates a strong tendency for ash deposition [17].

Solution:

- Optimize Blend Ratio: Find a biomass co-firing ratio that minimizes deposition propensity for your specific fuel combination.

- Use Additives: Incorporate high-alumina additives like kaolin into the fuel mix. Kaolin reacts with gaseous potassium compounds to form high-melting-point potassium aluminosilicates, capturing problematic alkalis and reducing deposition [18].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Drop Tube Furnace (DTF) Testing for Slagging and Fouling Propensity

Objective: To simulate the combustion and ash deposition behavior of a solid fuel in a pulverized-fuel boiler and collect ash deposits for analysis.

Materials:

- Drop Tube Furnace (DTF) system

- Water-cooled suction probe

- Pulverized fuel sample (particle size < 250 µm)

- Scanning Electron Microscope with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (SEM-EDS)

- X-Ray Diffractometer (XRD)

Methodology:

- Preparation: Pulverize the biomass or coal-biomass blend to a fine powder (≤250 µm) and dry it at 60°C for 1 hour [6].

- Combustion: Feed the pulverized fuel into the DTF at a controlled rate. Maintain a furnace temperature of 1300°C to simulate boiler conditions [22].

- Deposit Collection: Insert a water-cooled probe into the hot zone of the DTF to simulate a heat exchanger tube. The temperature difference causes ash particles to condense and deposit on the probe surface.

- Analysis:

- Mass Measurement: Weigh the deposited ash to determine the total deposition mass and calculate the Capture Efficiency (CE) [17].

- Visual Inspection: Photograph the probe to observe the extent and physical nature of the deposits.

- Material Characterization: Analyze the deposit's microstructure and composition using SEM-EDS and identify the crystalline phases present using XRD [19] [6].

Diagram 1: DTF Ash Deposition Analysis Workflow.

Protocol 2: Determination of Ash Fusion Temperature (AFT)

Objective: To determine the four characteristic melting temperatures of fuel ash under standardized conditions.

Materials:

- Muffle Furnace

- Ash Fusion Determinator (e.g., model FTS-02)

- Dextrin solution (as a binder)

- Ash mould

Methodology:

- Ash Preparation: Place the raw biomass in a muffle furnace. Heat to 750°C - 815°C and hold for 90 minutes to ensure complete ashing [21]. Allow the ash to cool.

- Cone Preparation: Mix the resulting ash with a dextrin solution to a moldable consistency. Transfer it to an ash mould to form a triangular cone. Carefully remove and dry the cone at 60°C [21].

- Fusion Test: Place the dried ash cone on a ceramic slab inside the ash fusion determinator furnace.

- Heating and Observation: Heat the furnace at a controlled rate to a maximum of 1500°C - 1600°C in a defined atmosphere (e.g., reducing atmosphere: 60% CO, 40% CO₂) [6]. Use a built-in camera and image processing software to record the cone's shape changes.

- Data Recording: Identify and record the four key temperatures: Deformation (DT), Softening (ST), Hemispherical (HT), and Flow (FT) [21].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for AFT and Slagging Experiments

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Kaolin | An additive that captures gaseous alkali compounds by forming high-melting-point potassium aluminosilicates, thereby reducing slagging [18]. |

| Mild Acid Solutions | Used in "ashless biomass" pre-treatment to leach and remove alkali metals and chlorine from the raw biomass, improving its combustion properties [17]. |

| Dextrin Solution | A binder used to prepare stable ash cones from powdery ash for the standard Ash Fusion Temperature test [21]. |

| Certified Gas Mixtures | Specific CO/CO₂ or air mixtures are required to create standardized oxidizing or reducing atmospheres during the AFT test, which significantly impacts the results [6]. |

Thermochemical Pathways to Low-Melting Point Phases

The depression of AFT is primarily due to the formation of low-melting point eutectic mixtures from the interactions of various ash components. The following diagram illustrates the key chemical pathways leading to these problematic phases.

Diagram 2: Thermochemical Pathways to Slagging and Fouling.

FAQ: Fundamental Ash Characteristics

What is the primary chemical difference between the ashes of agricultural residues and woody biomass?

The primary difference lies in the concentration of alkali metals (Potassium - K, Sodium - Na) and chlorine (Cl). Agricultural residues are typically rich in these elements, which leads to the formation of low-temperature melting compounds that drive slagging and fouling. In contrast, woody biomass ashes generally have higher concentrations of calcium (Ca) and silicon (Si) and lower levels of problematic alkalis, resulting in higher ash fusion temperatures and reduced slagging propensity [11] [2].

Table 1: Characteristic Ash Composition of Biomass Types

| Biomass Category | Typical Ash Content (% dry mass) | Key Slagging Elements | Key Inert/Refractory Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Residues (e.g., straw, olive cake) | 4% - 20% [2] | High K, Cl, S [23] [11] | Variable Si |

| Woody Biomass (e.g., forest residues) | <1% - 5% [2] | Low to Moderate K, Na | High Ca, Si [2] |

| Animal Waste & Sewage Sludge | Can be up to 60% [2] | High P, potentially high heavy metals [2] | - |

Why does agricultural residue ash cause more severe slagging in boilers?

Slagging is primarily caused by the formation of sticky, low-melting-point deposits on heat-exchange surfaces. In agricultural residues, volatile alkali salts, particularly potassium chloride (KCl), vaporize during combustion. These vapors then condense on cooler heat exchanger surfaces, forming a sticky layer that captures incoming ash particles through inertial impaction, leading to rapid deposit growth [23] [11]. This mechanism is dominant in high-chlorine feedstocks.

How does fuel moisture content exacerbate ash-related problems?

While not directly related to ash chemistry, high moisture content is an operational factor that intensifies slagging issues. Wet fuel (e.g., 50% moisture) lowers the combustion temperature, leading to incomplete combustion and higher production of unburned carbon and particulates. This results in thicker ash deposits, fouling, and a significant drop in boiler efficiency, which can be as much as 20-30% [24].

FAQ: Advanced Analysis & Mitigation

What are the key experimental methods for analyzing slagging tendency?

The following methodologies are crucial for characterizing ash behavior and predicting slagging in a research setting [25]:

- X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF): Used for determining the elemental composition of ash (e.g., K, Ca, Si, Cl). This data is the foundation for calculating various slagging indices.

- X-Ray Diffraction (XRD): Identifies the crystalline phases and minerals present in the ash and deposits (e.g., identifying the formation of potassium silicates or muscovite), which is critical for understanding the chemical mechanisms of slag formation.

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM): Reveals the morphology, size, and degree of sintering/adhesion of ash particles, providing visual evidence of slagging severity.

What strategies can mitigate slagging from agricultural residues?

Several pre-treatment and in-furnace strategies have been developed:

- Fuel Leaching: Washing biomass with water or dilute acid to remove water-soluble K and Cl components before combustion [23] [11].

- Use of Additives: Introducing aluminosilicate additives (e.g., kaolin) during combustion. These additives react with alkali metals to form high-melting-point compounds like kalsilite (KAlSiO4), effectively capturing problematic elements in the bottom ash and raising the ash fusion temperature beyond 1300°C [11].

- Co-firing: Blending high-risk agricultural biomass with woody biomass or coal can dilute the concentration of alkali metals and improve the overall ash melting behavior [25].

- AI-Optimized Combustion: Advanced control systems using deep learning (e.g., RNN-LSTM networks) can optimize combustion parameters in real-time, such as fuel-air ratios, to minimize conditions that promote slagging [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental and Operational Challenges

Problem: Inconsistent slagging evaluation results for a blended biomass fuel.

- Potential Cause: Traditional single slagging indices can give conflicting results when applied to complex fuel mixtures [25].

- Solution: Employ a multi-criteria decision analysis like the E-TOPSIS model. This method synthesizes multiple slagging predictive indices (e.g., RB/A, RS/A) using an objective entropy weight (EW) method, providing a more accurate and unified evaluation of slagging tendency that aligns with experimental observations [25].

Problem: Rapid fouling of heat exchangers during combustion trials with a new agricultural fuel.

- Potential Cause: High chlorine and potassium content leading to vapor condensation and inertial impaction of ash particles, especially at nominal load [23].

- Solution:

- Conduct ultimate and ash composition analysis to confirm K and Cl levels.

- Consider pre-treatment via water leaching.

- Evaluate the use of kaolin additives in a lab-scale reactor to quantify their effectiveness in raising the ash fusion temperature before scaling up.

Problem: Boiler efficiency is lower than calculated based on fuel calorific value.

- Potential Cause: High fuel moisture content, which is not an ash property but a critical fuel characteristic. Excess moisture wastefully consumes energy for evaporation, lowers combustion temperature and causes incomplete combustion [24].

- Solution: Implement fuel drying protocols to maintain moisture content within the optimal range of 10-20% for most boiler types [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Slagging and Fouling Research

| Item | Function/Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Kaolin | An aluminosilicate additive used to mitigate slagging by reacting with gaseous potassium to form refractory KAlSiO4, thereby increasing ash fusion temperature [11]. |

| XRF Standards | Certified reference materials used for calibrating X-ray fluorescence spectrometers to ensure accurate elemental analysis of ash samples. |

| Quartz Wool/Tubes | Used in lab-scale tube furnaces for ash preparation and deposit sampling under controlled temperature and atmosphere. |

| SEM Stubs & Sputter Coater | For preparing non-conductive ash samples for morphological and micro-analytical investigation via Scanning Electron Microscopy. |

| Dataset of Flame Images | Used for training Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) to predict potassium content and slagging tendency in real-time from combustion flame characteristics [26]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Slagging Tendency via Ash Composition and the E-TOPSIS Model

Objective: To quantitatively determine the slagging tendency of a biomass fuel or fuel blend.

Methodology Summary: This protocol involves preparing standard ash samples from fuel, analyzing their chemical composition, and applying a multi-index evaluation model to predict slagging severity [25].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- Dry the biomass fuel at 105°C for 10 hours to remove moisture.

- Pulverize the dried fuel to a fine particle size (<200 μm) to ensure homogeneity and complete ashing.

Ash Preparation:

- Create ash samples in a muffle furnace at a standardized temperature (e.g., 815°C) as per ASTM or other relevant standards.

Ash Composition Analysis:

- Analyze the prepared ash using X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) to determine the weight percentages of major oxides (SiO₂, Al₂O₃, Fe₂O₃, CaO, MgO, K₂O, Na₂O, SO₃, P₂O₅).

Calculate Single Slagging Indices:

- Using the XRF data, calculate a set of common predictive indices. These often include:

- Base-to-Acid ratio (RB/A): (Fe₂O₃ + CaO + MgO + K₂O + Na₂O) / (SiO₂ + Al₂O₃ + TiO₂)

- Silica Ratio (RS/A): SiO₂ / (SiO₂ + Fe₂O₃ + CaO + MgO + Na₂O)

- Other relevant indices (e.g., Fu index, Sintering Index, etc.).

- Using the XRF data, calculate a set of common predictive indices. These often include:

Apply the E-TOPSIS Evaluation Model:

- Determine Weights: Use the Entropy Weight (EW) method to assign objective weights to each of the calculated slagging indices based on their data variability and informational content.

- Model Slagging: Input the weighted indices into the TOPSIS method, which ranks the slagging tendency by comparing the similarity of your fuel's ash profile to both a "severe slagging" ideal and a "non-slagging" ideal.

- The result is a composite score that provides a more reliable slagging prediction than any single index alone.

Mitigation Technologies: From Laboratory Research to Industrial Implementation

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Biomass Preprocessing

FAQ 1: What is the most effective single pretreatment to reduce slagging and fouling?

Water leaching is highly effective for directly reducing slagging and fouling. It works by removing the water-soluble alkali metals (Potassium - K, Sodium - Na) and chlorine (Cl) that are primary contributors to these issues [27] [28]. The process can eliminate 25-80% of the ash content and significantly improves ash melting temperatures [27] [29]. One study noted that while leaching alone greatly improves ash sintering, it typically results in only a slight increase in the fuel's heating value [29].

FAQ 2: How does torrefaction change biomass to improve its combustion properties?

Torrefaction, a mild pyrolysis process at 200-300°C in an oxygen-deficient atmosphere, improves biomass properties in several ways [30]. It enhances energy density, grindability, and storage stability [31] [30]. Regarding slagging and fouling, torrefaction can remove portions of chlorine (Cl) and sulfur (S), which are elements that contribute to corrosive deposits and fouling [31]. However, its effectiveness in removing alkali metals is generally lower than leaching, and it can sometimes lead to a relative enrichment of ash content in the torrefied material [31] [29].

FAQ 3: Is it better to leach before or after torrefaction?

Research indicates that leaching before torrefaction is the more effective sequence [29] [32]. This sequence allows for the more effective removal of troublesome inorganic elements from the raw biomass before the thermal treatment. The studies show that the "leaching then torrefaction" sequence results in a solid biofuel with a higher heating value, lower ash content, and improved ash melting characteristics compared to the reverse order [29].

FAQ 4: Can I just mix my problematic biomass with another fuel instead of preprocessing it?

Yes, blending or co-firing a problematic herbaceous biomass (e.g., straw) with a cleaner fuel like coal or woody biomass is a valid and common strategy [31] [33]. This approach can dilute the concentration of alkali metals and chlorine, thereby reducing the overall slagging and fouling tendency of the fuel mix [33]. Co-combustion with coal has been shown to inhibit the formation of certain types of fouling deposits [31].

FAQ 5: Why is my biomass still causing problems after torrefaction?

This is a known issue. Torrefaction primarily removes chlorine and sulfur, but a significant portion of alkali metals may be retained in the char [31] [29]. These retained alkalis can still participate in the formation of problematic aluminosilicates during combustion, which contribute to fouling [31]. For biomass with very high alkali content, torrefaction alone may be insufficient, and a combined treatment with leaching is recommended.

Preprocessing Technique Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Biomass Preprocessing Techniques for Slagging and Fouling Mitigation

| Technique | Key Mechanism | Impact on Slagging/Fouling | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaching | Removes water-soluble alkali metals (K, Na) and Cl [27] [28]. | High effectiveness; can reduce ash content by 25-80% and raise ash melting point [27] [29]. | Simple operation, highly efficient at removing alkali elements, inexpensive [27]. | Slight increase in heating value; requires wastewater handling; does not improve energy density [29]. |

| Torrefaction | Removes Cl and S; decomposes hemicellulose [31] [30]. | Moderate/Variable; can reduce chlorides/sulfates-induced fouling but may concentrate some ash components [31]. | Improves grindability, energy density, and hydrophobicity [31] [30]. | Limited removal of alkalis; can sometimes increase fouling tendency of residual ash [31] [29]. |

| Blending | Dilutes concentration of problematic inorganic elements in the fuel blend [31] [33]. | Moderate effectiveness; depends on the co-fuel's properties [31]. | Simple to implement, no preprocessing equipment needed, can reduce overall emissions [33]. | Does not remove inorganics; requires a supply of clean co-fuel; potential for deposit formation remains. |

| Leaching + Torrefaction | Leaching removes alkalis & Cl; Torrefaction removes Cl & S and improves fuel properties [29] [32]. | Very high effectiveness; addresses limitations of single treatments [29]. | Produces high-quality solid biofuel with high heating value and high ash melting temperature [29]. | More complex process with multiple steps; higher operational costs. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Water Leaching for Alkali Removal

This protocol is based on methods used in multiple studies to reduce alkali content [29] [32].

- Principle: Water-soluble inorganic species, particularly alkali chlorides, are dissolved and removed from the biomass.

- Materials: Raw biomass (e.g., straw, wood chips), deionized water, filtration setup (e.g., vacuum filter), drying oven.

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Oven-dry raw biomass at 105°C for 24 hours to determine baseline moisture content [29].

- Leaching: Mix the dried biomass with deionized water in a ratio of approximately 50 g biomass to 0.5 L water [32]. Stir the mixture constantly for 1 hour at ambient temperature.

- Filtration: Separate the leached biomass from the water using vacuum filtration. Rinse the biomass with a small amount of fresh deionized water.

- Repeat (Optional): For higher removal efficiency, a second leaching cycle can be performed [32].

- Drying: Dry the leached biomass in an oven at 105°C for 24 hours or until constant mass is achieved [32].

- Success Metrics: Measure the reduction in ash content and the removal efficiency of key elements (K, Na, Cl) via ultimate analysis.

Protocol 2: Torrefaction for Fuel Upgrading

This protocol outlines a standard dry torrefaction process [31] [32].

- Principle: Thermal decomposition of biomass in an inert atmosphere at 200-300°C, leading to devolatilization and decomposition of hemicellulose.

- Materials: Reactor (e.g., fixed bed, tubular furnace), inert gas supply (N₂ or Ar), raw or leached biomass.

- Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Place the biomass sample in the reactor and purge the system with an inert gas (e.g., N₂) to establish an oxygen-free environment.

- Torrefaction: Heat the reactor to a target temperature between 250-300°C at a heating rate of <50°C/min [31] [30]. Maintain the temperature for a residence time of approximately 1 hour [30].

- Cooling & Collection: After the residence time, stop the heating and allow the reactor to cool under a continuous inert gas flow. Collect the solid product (torrefied biomass).

- Success Metrics: Calculate mass yield and energy yield. Analyze the solid for changes in elemental composition (especially Cl and S) and higher heating value (HHV).

Protocol 3: Combined Leaching and Torrefaction

This integrated protocol is designed to maximize fuel quality and minimize ash-related problems [29].

- Principle: Leaching first removes problematic inorganics, and subsequent torrefaction further upgrades the fuel properties.

- Materials: As in Protocols 1 and 2.

- Procedure:

- First Stage - Leaching: Subject the raw biomass to the Water Leaching protocol described above.

- Intermediate Drying: Completely dry the leached biomass.

- Second Stage - Torrefaction: Subject the leached and dried biomass to the Torrefaction protocol described above.

- Success Metrics: Evaluate the combined product for HHV, ash content, and ash fusion temperature. Compare results against individually pretreated samples.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application in Preprocessing Research |

|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Feedstock for experiments; common types include empty fruit bunch (EFB), rice husk, wheat straw, wood chips, and fast-growing timber species [27] [29]. |

| Deionized Water | Primary leaching agent for removing water-soluble alkali salts and chlorine [27] [32]. |

| Acetic Acid (Dilute) | Mild organic acid leaching agent; more effective than water for removing some non-water-soluble inorganic elements [29]. |

| Inert Gas (N₂, Ar) | Creates an oxygen-deficient atmosphere during torrefaction to prevent combustion [31] [32]. |

| Muffle Furnace | Used for ashing samples to determine ash content and for ash fusion tests [29]. |

| Bomb Calorimeter | Instrument for measuring the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of raw and processed biomass fuels. |

| X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) | Analytical technique for determining the elemental composition of biomass and ash [31]. |

Process Selection and Experimental Workflows

Experimental Workflow for Combined Treatment

FAQs: Kaolin for Slagging and Fouling Mitigation

Q1: What is the primary mechanism by which kaolin reduces slagging in biomass combustion?

Kaolin (Al₂Si₂O₅(OH)₄) primarily functions by capturing alkali metals like potassium (K) and sodium (Na) released during biomass combustion. It reacts with these volatile alkali species—particularly KCl and KOH—to form stable, high-melting-point aluminosilicates such as kalsilite (KAlSiO₄) and leucite (KAlSi₂O₆) [34] [35]. This chemical sequestration inhibits the formation of low-melting-point potassium silicates, which are a primary cause of slagging and ash deposition on heat exchange surfaces and in the combustion chamber [34] [36].

Q2: How does kaolin addition impact particulate matter (PM) emissions?

The addition of kaolin can lead to a significant reduction in fine and ultrafine particulate matter emissions. Studies in field-scale grate boilers have recorded PM reductions of 60-76% [37]. This occurs because kaolin captures alkali vapors that would otherwise condense to form fine PM. However, kaolin addition also increases the concentration of non-volatile oxides (SiO₂ and Al₂O₃) in the fly ash due to the adhesion and aggregation of airborne kaolin particles with the fine PM [37].

Q3: Under what conditions is kaolin most effective, and when should its use be avoided?

Kaolin is most effective for treating biomass fuels with high potassium and chlorine content and low inherent silica (SiO₂) levels [36]. Examples include many woody and herbaceous biomasses like straw, olive cake, and clean wood [35] [36]. Conversely, kaolin is unsuitable for biomasses already rich in silica (e.g., rice husks). In such cases, adding more silica via kaolin can worsen slagging by promoting the formation of low-temperature melts [36].

Q4: What is a common unintended consequence of kaolin addition, and how can it be managed?

A potential side effect is an increase in sintering and agglomeration in the bottom ash within the combustion chamber [34]. The same reactions that capture potassium in high-melting-point minerals can lead to a more sintered bottom ash structure. This can be managed by:

- Optimizing the kaolin dosage to the minimum required for effective alkali capture [34] [37].

- Ensuring proper fuel mixing and combustion control to prevent localized hotspots that exacerbate sintering.

Key Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the chemical mechanism of kaolin and a general experimental workflow for evaluating its effectiveness.

Quantitative Data on Kaolin Application

Table 1: Optimal Kaolin Dosage and Performance for Different Biomass Fuels

| Biomass Fuel Type | Optimal Kaolin Dosage (wt%) | Key Performance Outcomes | Experimental Scale | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virgin Wood (VW) / Recycled Wood (RW) | 1.55 - 2.5 | PM reduction: 60-76%; Deposition propensity reduced by ≥50% | 250 kW field-scale grate boiler | [34] [37] |

| Spruce & Short-Rotation Coppice Willow | 0.2 - 1.0 | Significant reduction in emitted particle mass; Decreased K-content in PM | 12 kW residential boiler | [35] |

| Herbaceous Biomass (e.g., Chamomile) | Specific dosage not given | Improved combustion parameters; Reduced CO emissions; Stabilized process | Low-power boilers | [38] |

| High-K, High-Cl Biomass (e.g., Olive Cake) | Effective at tested rates | Significantly improved ash flow properties; Eliminated severe sintering caused by KCl | Lab-scale viscosity/sintering tests | [36] |

Table 2: Key Analytical Methods for Evaluating Kaolin Effectiveness

| Method | Acronym | Parameter Measured | Function in Kaolin Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry | ICP-MS | Elemental composition of ash and PM | Quantifies partitioning of K, Al, Si, etc.; confirms alkali capture [34] |

| X-Ray Diffraction | XRD | Crystalline phase identification | Detects formation of kalsilite, leucite, etc. [34] |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy | SEM | Ash particle morphology and microstructure | Visualizes changes in ash structure; shows diminishment of KCl salts [37] |

| Ash Fusion Test | AFT | Deformation, Softening, Hemispherical, Flow temperatures | Determines improvement in ash melting behavior [39] [36] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Kaolin Studies

| Item | Function/Explanation | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Kaolin Powder | The primary aluminosilicate additive. High kaolinite content is crucial for effectiveness. | High-purity kaolin (Al₂Si₂O₅(OH)₄); Low iron content to avoid unwanted eutectics [36]. |

| Biomass Fuels | Representative feedstocks for testing. | Varied K, Cl, and Si content (e.g., woody, herbaceous, agricultural residues) [34] [35]. |

| Drop Tube Furnace (DTF) | Lab-scale reactor for controlled combustion experiments. | Allows for high heating rates and precise temperature control for initial screening [39]. |

| Pilot-Scale Grate Boiler | Field-scale reactor (e.g., 250 kW) for realistic testing. | Provides real-world conditions for slagging, fouling, and PM formation studies [34] [37]. |

| XRD Instrument | Identifies crystalline phases formed after kaolin addition. | Confirms the mechanism by detecting kalsilite, leucite, and other aluminosilicates [34]. |

| ICP-MS Instrument | Precisely measures elemental concentration in ash and PM. | Tracks the fate of alkali metals and the influx of Al and Si from the additive [34] [37]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when developing and testing advanced coatings for mitigating slagging and fouling in biomass boilers.

Weld Overlay

Q1: What are the primary causes of cracking in weld overlay claddings, and how can they be mitigated? Cracking in weld overlays is often due to high residual stresses and dilution, where the base material mixes with the clad material, altering its chemistry and properties [40]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Pre- and Post-Heat Treatment: This helps to relieve stresses formed during the high-heat welding process [41].

- Material Selection: Using filler metals with a compatible composition that is more resistant to cracking under stress [42].

- Controlled Deposition: Employing techniques like pulsed Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW) or Submerged Arc Welding (SAW) with a controlled heat input to minimize dilution and residual stress [42].

Q2: How can a researcher address uneven bead geometry during automated weld overlay experiments? Uneven bead geometry can compromise the protective quality of the overlay. To address this:

- Parameter Optimization: Systematically calibrate wire feed speed, oscillation settings, current, and voltage [42] [43].

- Seam Tracking: Implement automated seam tracking systems to maintain consistent torch positioning, especially on curved surfaces like boiler tubes [43].

- Fixture Review: Ensure the component is securely and properly fixtured to prevent movement during the deposition process [43].

High Velocity Thermal Spray (HVTS) Cladding

Q3: Our HVTS coatings show signs of premature failure in high-temperature environments. What could be the root cause? Premature failure often stems from two key factors:

- Permeability: Conventional thermal sprays can have microscopic pathways due to surface oxides, allowing corrosive media to penetrate and attack the substrate [40]. HVTS is specifically engineered to create a dense, low-permeability layer that prevents this [44].

- Coating Stress: High stress levels in thick coatings can lead to cracking. HVTS is a "low stress state" process, which reduces this propensity and is capable of withstanding temperatures over 500°C / 932°F [40] [41].

Q4: What are the critical parameters for optimizing HVTS coating adhesion in a lab setting? Achieving strong adhesion is critical for coating performance.

- Surface Preparation: The substrate must be thoroughly clean-blasted to a white metal finish to ensure mechanical bonding [40] [41].

- Adhesion Strength: HVTS processes should achieve adhesion strength exceeding 35 MPa, as verified by standardized pull-off tests [41].

- Process Control: Utilize precise control of gas flows, particle velocity, and standoff distance to create a dense, well-bonded coating structure [44].

Ceramic Protections

Q5: The ceramic coating on our test coupons is flaking off. What application errors might be responsible? Flaking typically indicates a bonding failure, often caused by:

- Inadequate Surface Preparation: Failure to properly clean, decontaminate, and roughen the substrate surface before application [45] [46].

- Incorrect Curing Environment: Application in direct sunlight or at temperatures outside the optimal range (e.g., 50-80°F) can prevent proper bonding and curing [45].

- Excessive Coating Thickness: Applying the coating too thickly can lead to an uneven surface texture and poor internal cohesion [46].

Q6: How can the lifespan of a ceramic coating in an aggressive boiler environment be experimentally validated? Validation requires accelerated testing that simulates operational conditions.

- High-Temperature Exposure: Test coated samples in a furnace at the boiler's operational temperatures to assess thermal stability and resistance to sintering.

- Corrosion Testing: Expose samples to environments rich in sulfur, chlorine, and other corrosive species found in biomass combustion to evaluate chemical resistance [44].

- Erosion Testing: Subject samples to particle-laden gas flows to simulate fly ash erosion and measure material loss over time [44].

Quantitative Data Comparison of Coating Technologies

The table below summarizes key performance and application data for the three coating technologies, aiding in material selection for specific experimental parameters.

| Feature | Weld Overlay | HVTS Cladding | Ceramic Coating |

|---|---|---|---|

| Application Speed | Moderate | Fast (Up to 3x faster than weld overlay) [41] | Slow (Requires precise, controlled conditions) [45] |

| Application Temperature | Very High | High | Low to Moderate (cures at 50-80°F / 10-27°C) [45] |

| Maximum Service Temperature | Very High (Limited by alloy) | Very High (Up to 980°C / 1800°F) [44] | High (Varies by formulation) |

| Coating Thickness | Thick (mm+ range) | Thin to Moderate (Typically <50µm particles) [44] | Very Thin (Micron range) |

| Adhesion Strength | Metallurgical Bond (Very High) | High (>35 MPa) [41] | Mechanical/Chemical Bond (Moderate) |

| Residual Stress | High (Risk of distortion) | Low stress state [40] | Low (when correctly applied) |

| Permeability to Corrosives | Very Low | Very Low (Ultra-low permeability) [44] | Low (Non-porous when applied correctly) [44] |

| Key Advantage | Tough, thick repair | Fast, dense, no dilution | Anti-slagging, non-stick surface [44] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Applying a Weld Overlay Cladding for Erosion Resistance

This methodology outlines the steps for depositing a corrosion-resistant alloy (CRA) weld overlay on a boiler tube substrate.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Base Material Preparation:

- Cleaning: Mechanically clean the substrate surface (e.g., via grit blasting) to remove all contaminants, including rust, oil, grease, and existing oxide scales [42].

- Inspection: Visually inspect for surface defects like cracks or pits that could undermine coating integrity.

- Equipment Setup: Secure the boiler tube in a lathe or positioning system. Set up the automated welding system (e.g., Submerged Arc Welding or GMAW) with the chosen CRA wire (e.g., nickel-or cobalt-based alloy) [42] [43]. Integrate a wire feeder and oscillation equipment for even deposition [42].

- Pre-Heat: Heat the substrate to a specified temperature (e.g., 200-300°C, depending on base and clad material) to prevent hydrogen-induced cracking and reduce thermal stress [41].

- Cladding Deposition:

- Initiate the automated weld sequence, coordinating the part manipulation with the welding torch movement [43].

- Maintain controlled parameters: voltage, amperage, travel speed, and oscillation width to achieve a consistent bead with minimal dilution.

- Deposit the required number of layers to achieve the target clad thickness.

- Post-Process Heat Treatment: Apply a post-weld heat treatment (PWHT) according to the material specification to temper the microstructure and relieve residual stresses [41].

- Inspection and Testing:

- Dye Penetrant Testing (PT): Check the clad surface for surface-breaking defects.

- Ultrasonic Testing (UT): Verify the integrity of the bond and check for internal discontinuities.

Protocol 2: High Velocity Thermal Spray (HVTS) Cladding for Sulfidation Resistance

This protocol details the application of an HVTS alloy cladding designed for high-temperature corrosion protection.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Substrate Repair and Preparation:

- Welding Repair: Address any pre-existing surface damage or pitting corrosion by welding and grinding the surface smooth [40].

- Clean Blasting: Abrasively blast the substrate to a white metal finish (SA 2.5) to create an anchor profile and a perfectly clean surface for optimal mechanical adhesion [40].

- HVTS System Setup: Prepare the High Velocity Thermal Spray gun with the specified high-chromium alloy powder. Confirm gas supplies and powder feeder operation.

- Coating Application:

- Using a robotic manipulator for consistency, traverse the HVTS gun across the prepared surface at a defined standoff distance and speed.

- The process accelerates powder particles to high velocities within a heated gas stream, creating a dense, low-oxide coating upon impact with the substrate [44].

- Apply the coating to the specified thickness, typically in a single layer due to the process's efficiency [41].

- Quality Assurance:

- Conduct adhesion tests on witness samples sprayed alongside the component using a portable pull-off adhesion tester (target >35 MPa) [41].

- Perform holiday detection (porosity testing) at specified voltages to ensure the coating is free of interconnected porosity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for experiments in advanced boiler coatings.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Nickel-Based Alloy Wire | A common filler metal for weld overlay; provides excellent resistance to corrosion and high-temperature oxidation [42]. |

| Cobalt-Based Alloy Powder | Used in HVTS and some weld processes; offers superior wear and heat resistance, ideal for critical components like turbine blades [42]. |

| High-Chromium HVTS Powder | Engineered specifically for sulfidation resistance; forms a dense, stable oxide layer that protects against aggressive sulfur compounds in combustion environments [44]. |

| Specialized Ceramic Coating Formulation | A non-porous, non-wetting ceramic material that prevents molten slags from bonding to boiler tube surfaces, reducing slag accumulation [44]. |

| Granular Flux (for SAW) | Used in Submerged Arc Welding to shield the molten weld pool from atmospheric gases, prevent spatter, and stabilize the arc [42]. |

| Abrasive Grit (for Blasting) | Critical for surface preparation; creates a clean, roughened surface profile (anchor pattern) to maximize the mechanical adhesion of thermal spray coatings. |

Experimental Workflow and Coating Selection Diagrams

Coating Technology Selection Workflow

HVTS Coating Application Process

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Slagging and Fouling

Problem: Ash deposits (slagging and fouling) are forming on heat exchanger surfaces, reducing efficiency and increasing maintenance.

Primary Causes & Solutions:

Cause 1: Suboptimal Air Distribution Low furnace excess oxygen and air/fuel imbalances create localized reducing atmospheres that lower ash fusion temperatures and promote slagging [47]. Staged air distribution can also lead to incomplete combustion if not properly tuned [48].

- Solution:

- Measure and Balance: Use a water-cooled high-velocity thermocouple (HVT) probe to measure furnace exit gas temperature (FEGT) and oxygen profiles. Ensure all points are oxidizing, preferably above 3% excess oxygen [47].

- Optimize Air Modes: Implement a rear-enhanced or refined-staged primary air distribution. This expands the combustion zone, improves burnout, and can reduce NOx and CO concentrations, leading to more uniform temperatures and less slagging [49] [48].

- Inspect Hardware: Check for burner damage, pulverizer performance issues, and ensure coal fineness meets guidelines [47].

- Solution:

Cause 2: Excessive Furnace Temperature Operating with a furnace exit gas temperature (FEGT) too close to or above the ash softening temperature causes ash to become sticky and adhere to surfaces [47]. Biomass boilers can have internal temperatures from 500°C to 1200°C, making management critical [50].

- Solution:

- Determine Ash Softening Temperature: Conduct laboratory ash fusion tests (e.g., ASTM D1857) on your fuel [47] [8].

- Control FEGT: Maintain the FEGT approximately 100°F to 150°F (55°C to 85°C) below the ash softening temperature [47].

- Utilize Data: Implement closed-loop combustion optimization systems that use in-furnace laser measurements (O2, CO, temperature) to automatically adjust air and fuel settings, keeping operations within a non-slagging "optimum zone" [51].

- Solution:

Cause 3: High Alkali Content and Condensation in Biomass Fuels Biomass fuels often contain high levels of alkali metals (e.g., potassium). During combustion, alkali vapors (especially KCl) can condense on cooler superheater tubes, forming a viscous initial layer that captures fly ash particles and accelerates deposition [52] [8].

- Solution:

- Fuel Selection/Blending: Use biomass fuels with higher ash fusion temperatures or blend high-alkali fuels with cleaner woody biomass [53].

- Wall Temperature Management: For medium-temperature superheaters, moderate increases in wall temperature can inhibit condensation, though this may be offset by increased deposit viscosity [52].

- Apply Predictive Models: Use integrated slagging models that account for condensation fouling and ash viscous deposition to predict and mitigate deposition in specific boiler areas [52].

- Solution:

Guide 2: Addressing High CO Emissions and Low Combustion Efficiency

Problem: High carbon monoxide (CO) emissions and low combustion efficiency indicate incomplete combustion.

Primary Causes & Solutions:

Cause 1: Insufficient Combustion Air or Poor Mixing Inadequate air supply, or poor mixing of air with volatile gases, prevents complete combustion [54].

- Solution:

- Tune Secondary Air: Optimize the injection angle and velocity of secondary air to ensure proper turbulence and mixing in the freeboard [48].

- Adjust for Fuel Moisture: For high-moisture fuels, increase primary air in the drying zone and optimize secondary air to promote burnout and reduce CO [54].

- Apply Optimizer: Automated combustion optimizers can manipulate air control settings in closed-loop to maintain low CO without drifting into high-NOx or slagging conditions [51].

- Solution:

Cause 2: High Fuel Moisture Content High moisture absorbs combustion heat to evaporate water, reducing flame temperature and leading to incomplete combustion [53] [54].

Cause 3: Incorrect Primary Air (PA) Distribution A uniform PA distribution may not provide optimal conditions for all stages of fuel conversion on the grate, leading to high CO at the furnace outlet [48].

- Solution: Shift from a uniform to a refined-staged PA distribution. This strategy supplies air according to the combustion needs of different zones on the grate, significantly improving char burnout and reducing CO concentration [48].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical air distribution parameters to control for minimizing slagging? The most critical parameters are furnace excess oxygen levels and the primary air distribution profile along the grate. Maintaining sufficient oxygen (e.g., >3%) in the burner belt prevents secondary combustion and reducing atmospheres that lower ash fusion temperatures [47]. Optimizing the primary air distribution (e.g., using a rear-enhanced mode) ensures complete combustion and avoids localized high-temperature zones that initiate slagging [49] [48].