Thermochemical Conversion of Glycerol for Hydrogen Production: Pathways, Catalysts, and Sustainable Integration

This article provides a comprehensive review of thermochemical pathways for converting glycerol, a major by-product of biodiesel production, into hydrogen.

Thermochemical Conversion of Glycerol for Hydrogen Production: Pathways, Catalysts, and Sustainable Integration

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of thermochemical pathways for converting glycerol, a major by-product of biodiesel production, into hydrogen. It explores foundational concepts like steam reforming and pyrolysis, delves into advanced catalytic strategies and process optimization, and offers a comparative analysis of different methodologies. Aimed at researchers and scientists, the content critically examines the integration of this process within a circular bioeconomy, addressing technical challenges, economic feasibility, and future research directions for sustainable hydrogen production.

Glycerol as a Sustainable Feedstock: Foundations for Hydrogen Production

The global push for renewable energy has positioned biodiesel as a key alternative to fossil diesel. However, a defining characteristic of its production process is the generation of a significant glycerol surplus. The transesterification reaction, the primary method for biodiesel production, yields biodiesel and glycerol at a volumetric ratio of approximately 10:1; for every 10 cubic meters of biodiesel produced, about 1 cubic meter of crude glycerol is generated [1]. With global biodiesel production reaching 30.8 million cubic meters in 2016 and projected to grow annually by about 4.5%, the volume of concomitant crude glycerol poses a substantial market and environmental challenge [1]. This surplus has historically depressed glycerol prices, threatening the economic sustainability of the entire biodiesel value chain [1] [2]. Consequently, developing value-added applications for crude glycerol, particularly in sustainable technologies like thermochemical conversion for hydrogen production, is imperative to ensure the long-term viability of biodiesel as a renewable fuel.

Market Dynamics of Glycerol

Global Supply, Demand, and Price Trends

The glycerol market is intrinsically linked to the biodiesel industry, as its supply is a function of biodiesel production levels rather than direct demand for glycerol itself [3]. This dynamic decouples glycerol supply from its price, leading to inherent market volatility. Recent market data indicates significant price surges, driven by a complex interplay of factors.

Table 1: Recent Glycerol Price Trends and Forecasts (2024-2025)

| Region/Type | Price Point | Value | Trend & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| East China (99.5%) | Nov 2025 (Forecast) | ¥9,200-9,400/ton | Cooling from a peak of ~¥11,000/ton in early Nov 2025 [4]. |

| Europe | Oct 2025 | US$1.01/KG | Year-on-year increase of 28% compared to Oct 2024 [3] [5]. |

| CIF China (Import) | Late Q3 2025 | ~$1,170/ton | Increase of ~28.5% from June 2025 levels [4]. |

| Global Forecast | H2 2025 | Price softening expected | Amid ample supply, softer demand, and stable palm oil prices [6]. |

Table 2: Key Global Glycerol Traders and Market Size

| Category | Details | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Top Exporting Countries | Indonesia ($461M), Germany ($270M), Malaysia ($243M) [5]. | 2020 Trade Data |

| Top Importing Countries | China ($423M), United States ($118M), Netherlands ($117M) [5]. | 2020 Trade Data |

| Global Market Size | Valued at USD 5.6 billion in 2024; projected to reach USD 11.9 billion by 2034 [7]. | Market Analysis |

The recent price pressure, particularly evident in East Asia, is attributed to a confluence of factors. On the supply side, policy changes in Indonesia—the world's largest exporter—such as export levies on crude glycerin have reduced global availability of this raw material [4] [3]. Furthermore, palm oil production disruptions and its increased diversion to meet biodiesel mandates (e.g., Indonesia's B40 program) have tightened supply [8]. On the demand side, the largest downstream sector in China, epichlorohydrin (ECH) production, has faced financial unviability due to high glycerol feedstock costs, leading to pushback and weakened demand [4]. This demonstrates the market's self-correcting mechanism, where high prices eventually suppress demand.

The Shift in Global Trade Flows

Global trade flows for glycerol have undergone a significant transformation. Indonesia has emerged as the dominant exporter, with its shipments projected to reach nearly 500 thousand tons to China alone in 2025, a dramatic increase from 64 thousand tons in 2017 [3]. This shift is driven by Indonesian policies promoting biodiesel production from palm oil to support agricultural incomes [3]. Concurrently, this has created a new global benchmark for glycerol pricing, with Chinese import prices now leading and European prices following with a delay of a few months [3].

Established and Emerging Applications for Crude Glycerol

The need to absorb the glycerol surplus has spurred extensive research into value-added applications, which can be broadly categorized as follows:

Table 3: Value-Added Applications for Crude Glycerol

| Application Category | Specific Use | Key Function/Role |

|---|---|---|

| Animal Feed | Component in diets for swine, poultry, and ruminants [2]. | High-value energy source (Metabolizable Energy ~13.9-14.7 MJ/kg) [2]. |

| Biological Conversion | Production of 1,3-Propanediol (1,3-PDO) [1] [2]. | Fermentation by microorganisms like Klebsiella pneumoniae [2]. |

| Chemical Synthesis | Feedstock for epichlorohydrin, acrylic acid, and propylene glycol [1]. | Renewable raw material for green chemistry [1]. |

| Biohydrogen Production | Feedstock for steam reforming [9]. | Renewable source for sustainable hydrogen gas [9]. |

Among these, thermochemical conversion routes like steam reforming are particularly promising within the context of a sustainable energy economy, as they transform a low-value by-product into biohydrogen, a high-value energy carrier.

Application Note: Glycerol-to-Hydrogen via Steam Reforming

Protocol for Glycerol Steam Reforming (GSR) with Ni-based Catalysts

This protocol details the experimental methodology for converting crude glycerol to hydrogen-rich syngas via steam reforming, with a focus on the influence of catalytic support.

4.1.1 Principle

Glycerol Steam Reforming (GSR) is an endothermic process that converts glycerol and water into hydrogen-rich synthesis gas at elevated temperatures in the presence of a catalyst. The overall reaction is:

C3H8O3 (g) + 3H2O (g) 3CO2 (g) + 7H2 (g) [9].

The process involves complex reaction pathways, including glycerol decomposition and the water-gas shift reaction, to maximize hydrogen yield [9].

4.1.2 Materials and Reagents Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Glycerol Steam Reforming

| Item | Specification / Function | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| Crude Glycerol | By-product from homogeneous alkaline-catalyzed biodiesel production [2]. | Primary feedstock. |

| Catalytic Supports | Alumina (Al2O3), Dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2), Zeolite [9]. | Provide high surface area, porosity, and active sites for the metal catalyst. |

| Active Metal Catalyst | Nickel Nitrate Hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O) [9]. | Precursor for the active Ni metal, which cleaves C-C and C-H bonds. |

| Water | Deionized / Ultra-high purity. | Source of steam (reactant) and for preparing aqueous catalyst precursors. |

| Gases | High-purity Nitrogen (N2), Air (Zero grade). | Used for reactor purging, catalyst pre-treatment (calcination), and as a carrier gas. |

4.1.3 Equipment and Instrumentation

- Fixed-Bed Tubular Reactor: Constructed from quartz or Inconel, capable of operating at temperatures up to 900°C.

- Furnace: Three-zone tube furnace for precise and uniform temperature control.

- Catalyst Preparation Setup: Lab glassware (beakers, flasks), drying oven, and muffle furnace for catalyst calcination.

- Feed Delivery System: High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) pump for precise glycerol-water solution feed, and a vaporizer unit.

- Gas Analysis: Online Gas Chromatograph (GC) equipped with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) for monitoring H2, CO2, CO, and CH4 concentrations in the outlet gas stream.

4.1.4 Experimental Procedure

- Catalyst Synthesis (Wet Impregnation): a. Prepare an aqueous solution of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O with a concentration calculated to achieve the desired Ni loading (e.g., 5-15 wt%) on the support [9]. b. Add the catalytic support (e.g., Alumina, Dolomite) to the solution under continuous stirring for 4 hours to ensure homogeneous dispersion. c. Remove water by evaporating the mixture at 90°C under constant stirring. d. Dry the resulting solid in an oven at 110°C for 12 hours. e. Calcine the catalyst in a muffle furnace at 500°C for 3 hours in a static air atmosphere to decompose the nitrate and form the metal oxide.

Reaction Setup and Catalyst Activation: a. Load the calcined catalyst into the center of the tubular reactor, plugging the ends with quartz wool. b. Prior to the reaction, reduce the catalyst in situ by flowing a mixture of H2 (10% in N2) at a flow rate of 50 mL/min while ramping the temperature to 700°C and holding for 2 hours.

Glycerol Steam Reforming: a. After reduction, purge the system with N2 and set the reactor temperature to the target reforming temperature (e.g., 850°C) [9]. b. Feed an aqueous glycerol solution (e.g., 10-20 wt% glycerol in water) at a predetermined flow rate using the HPLC pump. The solution is vaporized before entering the catalytic bed. c. Maintain a constant steam-to-carbon (S/C) molar ratio, typically between 3 and 9, to suppress coke formation and enhance the water-gas shift reaction. d. Allow the system to stabilize for 60 minutes before beginning data collection.

Product Analysis and Data Collection: a. Analyze the composition of the outlet gas stream (H2, CO2, CO, CH4) at regular intervals (e.g., every 15 minutes) using the online GC-TCD. b. Continue the reaction for a set duration (e.g., 3-5 hours) to assess initial catalyst performance and stability. c. Calculate key performance metrics: - Hydrogen Yield (%):

(Moles of H2 produced) / (Theoretical moles of H2 from Eq. 1) * 100- H2 Selectivity (%):(Moles of H2) / (Total moles of all gaseous products) * 100

4.1.5 Safety Considerations

- Perform catalyst reduction and reactor operation inside a fume hood.

- Use personal protective equipment (PPE) including heat-resistant gloves and safety glasses.

- Hydrogen is highly flammable; ensure all connections are leak-proof and the area is well-ventilated.

- High-temperature operations require careful handling to prevent burns.

Results and Data Analysis: The Critical Role of Catalytic Support

Experimental data confirms that the choice of catalytic support is a critical parameter determining hydrogen purity and yield.

Table 5: Influence of Catalytic Support on Hydrogen Purity in GSR (at 850°C)

| Catalytic Support | Active Catalyst | Average Hâ‚‚ Purity (%) | Key Observations and Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zeolite | None | ~51% | Suffers from amorphization at high temperatures; limited effectiveness [9]. |

| Alumina (Al2O3) | Ni (5-15 wt%) | ~70% | Common support; performance improves with Ni loading but prone to coke deposition [9]. |

| Dolomite | Ni (5-15 wt%) | ~90% | Superior porosity and in-situ COâ‚‚ capture (via CaO recarbonation) shifts equilibrium, enhancing Hâ‚‚ yield [9]. |

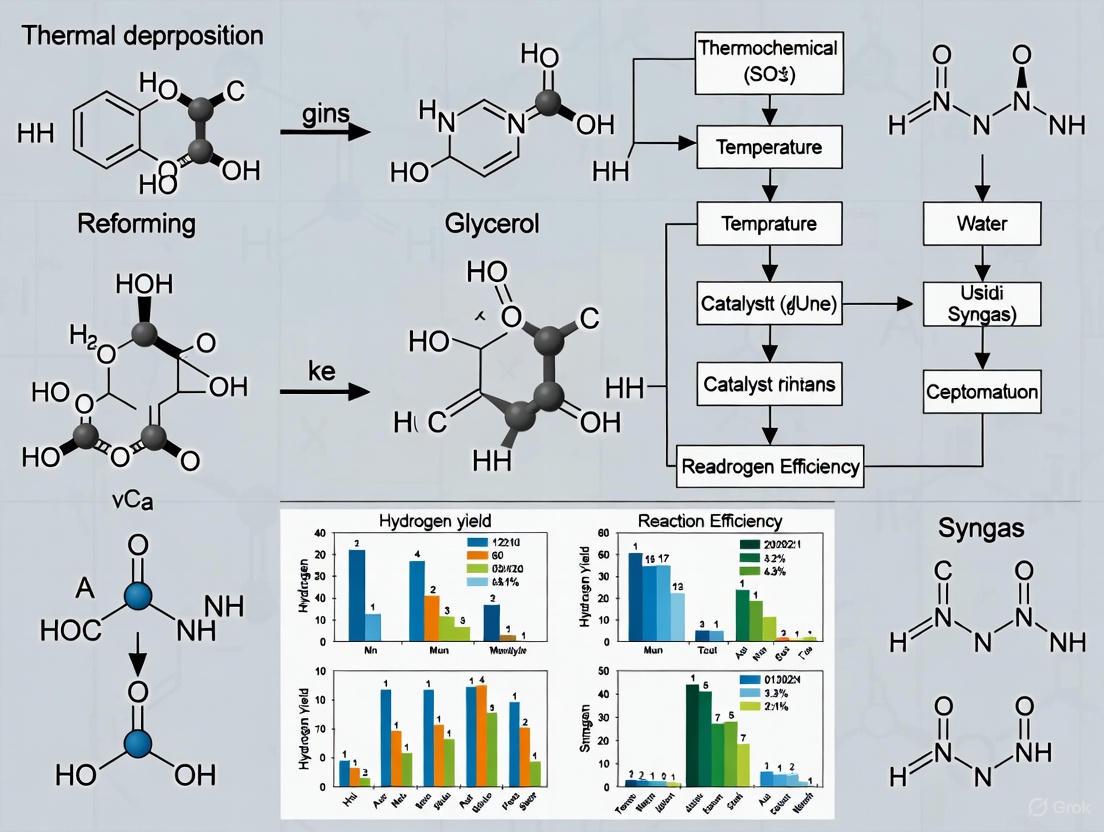

The following workflow diagram summarizes the entire experimental process from catalyst preparation to result analysis.

Experimental Workflow for Glycerol Steam Reforming

The superior performance of Ni/Dolomite catalysts can be attributed to a synergistic mechanism involving the nickel active sites and the basic dolomite support, as illustrated below.

Catalyst Support Role in GSR Mechanism

The glycerol surplus, a direct consequence of global biodiesel policies, presents a dual challenge of waste management and economic viability. Market dynamics are characterized by volatility, with prices heavily influenced by biodiesel feedstock policies, particularly in Southeast Asia, and demand patterns from major importers like China. Within this context, thermochemical conversion pathways, especially catalytic steam reforming, offer a promising route to valorize this surplus into renewable biohydrogen. Experimental evidence highlights that the strategic selection of catalytic materials, such as Ni on dolomite, is crucial for achieving high hydrogen purity (up to 90%), making the process more efficient and economically attractive. Future research should focus on optimizing catalyst formulations for enhanced stability and resistance to coke formation, scaling up the reforming process, and conducting thorough techno-economic analyses to accelerate the integration of glycerol-to-hydrogen technology into the broader bio-refinery framework.

Why Glycerol for Hydrogen? Analyzing Hydrogen Content and Process Thermodynamics

The thermochemical conversion of glycerol into hydrogen represents a promising pathway to enhance the sustainability and economic viability of the biodiesel industry. Glycerol (C₃H₈O₃) is a major byproduct of biodiesel production, with approximately 10 kg of glycerol generated for every 100 kg of biodiesel produced [10]. This has led to market saturation and declining prices, creating an urgent need for valorization strategies [11] [12]. Steam reforming of glycerol has emerged as a technologically favorable approach for producing hydrogen-rich syngas, aligning with circular economy principles and clean energy goals. This analysis examines the fundamental thermodynamic considerations and hydrogen content of glycerol that make it an attractive feedstock for hydrogen production, providing detailed experimental protocols for researchers investigating this promising pathway.

Glycerol as a Feedstock for Hydrogen Production

The Glycerol Opportunity

The dramatic growth in biodiesel production has created a global surplus of glycerol, depressing its market value and transforming it from a valuable chemical commodity to a waste management challenge [11] [10]. This market shift has stimulated research into alternative uses for glycerol, with hydrogen production emerging as one of the most promising valorization pathways due to glycerol's favorable chemical properties and the growing importance of hydrogen as a clean energy carrier [12] [13].

Hydrogen Content and Theoretical Yield

Glycerol's molecular structure provides a high hydrogen-to-carbon ratio, making it theoretically suitable for efficient hydrogen production through steam reforming. The overall stoichiometric reaction for glycerol steam reforming is:

C₃H₈O₃(g) + 3H₂O(g) → 3CO₂(g) + 7H₂(g) [11]

This equation indicates that one mole of glycerol can theoretically yield seven moles of hydrogen gas. However, this maximum theoretical yield is never achieved in practice due to competing reactions, thermodynamic limitations, and kinetic constraints that lead to the formation of byproducts such as methane, carbon monoxide, and solid carbon [11] [14].

Comparative Advantages

The utilization of glycerol as a hydrogen source offers several distinct advantages:

- Abundance and Cost-effectiveness: As an inevitable byproduct of biodiesel manufacturing, glycerol is readily available at low cost [12]

- Renewable Nature: Derived from biomass, glycerol's use supports circular economy principles and sustainable resource utilization [12]

- Favorable Hydrogen Content: The molecular structure of glycerol offers a high hydrogen-to-carbon ratio [12]

- Process Integration Potential: Glycerol valorization can be integrated with existing biodiesel production infrastructure [12]

- Environmental Benefits: Utilizing glycerol addresses waste management issues while contributing to clean energy production [12]

Thermodynamic Analysis of Glycerol Steam Reforming

Fundamental Thermodynamics

The steam reforming of glycerol is highly endothermic, with a standard enthalpy change of ΔH° = 123 kJ/mol for the complete reforming reaction [14]. This significant energy requirement necessitates high-temperature operation for favorable equilibrium conversion. The process involves complex reaction networks including glycerol decomposition, water-gas shift reaction, and methane formation, which compete simultaneously and affect the final hydrogen yield and product distribution [11] [14].

Effect of Process Parameters

Thermodynamic equilibrium calculations using Gibbs free energy minimization reveal how key process parameters affect hydrogen production efficiency:

Table 1: Effect of Process Parameters on Hydrogen Yield from Glycerol Steam Reforming [11]

| Parameter | Condition | Effect on Hydrogen Production | Optimal Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 573-1073 K | Increases significantly with temperature | >900 K |

| Pressure | 1-5 atm | Decreases with increasing pressure | 1 atm |

| Water:Glycerol Feed Ratio (WGFR) | 1:1 to 9:1 | Increases with higher WGFR | 9:1 (molar) |

| Glycerol Conversion | 600-1000 K | >99.99% across all conditions | N/A |

Carbon Formation Thermodynamics

A critical challenge in glycerol steam reforming is carbon deposition, which deactivates catalysts through coking. Thermodynamic analysis identifies conditions that promote or inhibit carbon formation through reactions such as:

Boudouard reaction: 2CO C + COâ‚‚ [14] Methane decomposition: CHâ‚„ C + 2Hâ‚‚ [14]

Carbon formation is minimized at high temperatures (>900 K), high water-to-glycerol ratios (>9:1), and low pressures (1 atm) [11]. Understanding these thermodynamic boundaries is essential for designing stable reforming processes that minimize catalyst deactivation.

Experimental Protocols for Glycerol Steam Reforming

Catalyst Synthesis and Characterization

Protocol 1: Preparation of Ni-Cu/MgO Catalyst

Principle: Bimetallic Ni-Cu catalysts on MgO support demonstrate enhanced activity and reduced coking compared to monometallic nickel catalysts [14]. The addition of copper modifies the nickel electronic properties, while MgO's basicity helps suppress carbon deposition.

Materials:

- Nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) - Nickel source

- Copper nitrate trihydrate (Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O) - Copper promoter

- Magnesium oxide (MgO) - Catalyst support

- Deionized water - Solvent

Procedure:

- Dissolve appropriate amounts of Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O in deionized water to achieve target metal loading (typically 10 wt% Ni, 2-5 wt% Cu)

- Add MgO support to the solution and stir for 4 hours at room temperature using magnetic stirrer

- Remove water slowly using rotary evaporator at 70°C under reduced pressure

- Dry the solid residue overnight at 110°C in oven

- Calcine the catalyst at 500°C for 4 hours in muffle furnace

- Reduce the catalyst in flowing hydrogen (50 mL/min) at 600°C for 2 hours before reaction

Characterization:

- Determine metal dispersion using Hâ‚‚ chemisorption

- Analyze crystal structure with X-ray diffraction (XRD)

- Examine surface area and porosity using Nâ‚‚ physisorption (BET method)

- Assess reduction behavior with temperature-programmed reduction (TPR)

Kinetic Measurement Protocol

Protocol 2: Fixed-Bed Reactor Studies for Reaction Kinetics

Principle: Determining kinetic parameters provides fundamental understanding of reaction rates and mechanisms, enabling reactor design and process optimization [14].

Materials:

- Fixed-bed tubular reactor (typically quartz or stainless steel, 10-15 mm ID)

- Mass flow controllers for gases

- HPLC pump for liquid feed

- Temperature-controlled furnace

- Online gas chromatograph with TCD and FID detectors

Procedure:

- Load reduced catalyst (0.2-0.5 g) into reactor between quartz wool plugs

- Set reactor temperature to desired value (600-800°C)

- Prepare glycerol-water mixture at target molar ratio (typically 1:9 to 1:12)

- Feed mixture using HPLC pump at weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 0.5-2.0 hâ»Â¹

- Use nitrogen as carrier gas at 20-50 mL/min

- Allow system to stabilize for 1-2 hours at each condition

- Analyze effluent stream using online GC every 30 minutes

- Collect data at minimum of five different temperatures for activation energy calculation

- Vary glycerol partial pressure by changing feed concentration or flow rate

Data Analysis:

- Calculate glycerol conversion: X = (Fᵢₙ - Fₒᵤₜ)/Fᵢₙ × 100%

- Determine hydrogen yield: YHâ‚‚ = FHâ‚‚/(7 × F_glyâ‚ᵢₙ₎)

- Estimate reaction rates from conversion data at different space velocities

- Fit power-law or Langmuir-Hinshelwood models to determine kinetic parameters

- Calculate activation energy from Arrhenius plot

Table 2: Typical Kinetic Parameters for Glycerol Steam Reforming [14]

| Catalyst | Temperature Range (°C) | Reaction Order (Glycerol) | Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | Rate Expression Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ru/Al₂O₃ | 350-500 | 1.0 | 21.2 | Power Law |

| Ni/CeOâ‚‚ | 600-650 | 0.233 | 103.4 | Power Law |

| Ni-Cu/MgO | 480-580 | - | - | Langmuir-Hinshelwood |

Thermodynamic Equilibrium Calculations

Protocol 3: Gibbs Free Energy Minimization for Equilibrium Composition

Principle: The equilibrium composition of complex reforming reactions can be determined by minimizing the total Gibbs free energy of the system, providing theoretical maximum yields and guiding experimental conditions [11].

Computational Procedure:

- Define the system containing C, H, and O atoms based on glycerol-water feed

- Identify all possible product species: Hâ‚‚, CO, COâ‚‚, CHâ‚„, Hâ‚‚O, C(s)

- Obtain thermodynamic data (ΔGf°, ΔHf°, C_p) for all species from databases

- Formulate the Gibbs free energy minimization problem:

Min G = Σni[Gi° + RT ln(y_iP)] for i = 1 to N species

Subject to atomic balances: Σaij ni = A_j for j = C, H, O

- Solve the constrained minimization problem using Lagrange multipliers or sequential quadratic programming

- Repeat calculations across temperature range (600-1000 K) and pressure range (1-5 atm)

- Validate model by comparing with experimental data at selected conditions

Reaction Pathways and Process Visualization

Glycerol Steam Reforming Reaction Network

The steam reforming of glycerol proceeds through a complex network of parallel and series reactions, which can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Glycerol Steam Reforming Reaction Network [14]

This network illustrates the competing pathways that determine final product distribution, including desirable hydrogen-producing routes and undesirable coke-forming reactions.

Thermodynamic Parameter Relationships

The effects of key process parameters on hydrogen yield can be visualized through the following relationship diagram:

Diagram 2: Parameter Effects on Hydrogen Yield and Carbon Formation [11]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Glycerol Steam Reforming Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Typical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Glycerol | Feedstock | ≥99.5% purity, anhydrous |

| Nickel Nitrate | Catalyst precursor | Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, ≥98.5% |

| Magnesium Oxide | Catalyst support | High surface area (>50 m²/g) |

| Alumina Support | Alternative catalyst support | γ-Al₂O₃, 100-200 m²/g |

| Ruthenium Chloride | Noble metal catalyst precursor | RuCl₃·xH₂O, ≥99.9% |

| Cerium Nitrate | Redox promoter | Ce(NO₃)₃·6H₂O, ≥99% |

| Quartz Reactor | Reaction vessel | 10-15 mm ID, high temperature |

| Mass Flow Controllers | Gas flow regulation | 0-100 mL/min, ±1% accuracy |

| Online GC-TCD | Product analysis | Porapak Q & Molecular Sieve columns |

| Safinamide-d4 | Safinamide-d4, MF:C17H19FN2O2, MW:306.37 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| SN50 | SN50, MF:C129H230N36O29S, MW:2781.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Glycerol represents a promising renewable feedstock for hydrogen production due to its favorable hydrogen content, renewability, and increasing availability as a biodiesel byproduct. Thermodynamic analysis reveals that high temperatures (>900 K), low pressures (1 atm), and high water-to-glycerol feed ratios (9:1) maximize hydrogen yield while minimizing carbon formation. Experimental protocols for catalyst preparation, kinetic studies, and thermodynamic calculations provide researchers with essential methodologies for investigating glycerol steam reforming. The integration of glycerol reforming into biodiesel production facilities offers significant potential for enhancing the sustainability and economic viability of both processes, contributing to the development of a circular bioeconomy.

The global energy sector is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by the increasing demand for sustainable and clean energy sources. Hydrogen, as a carbon-free energy carrier, is poised to play a vital role in this transition, supporting the decarbonization of hard-to-abate industrial sectors and the integration of intermittent renewable resources [15]. Thermochemical conversion pathways—pyrolysis, gasification, and reforming—present viable methods for producing hydrogen and other valuable products from renewable feedstocks. Within this context, glycerol, a major byproduct of biodiesel production, has emerged as a promising bio-derived feedstock for hydrogen production [10]. This article details the application notes and experimental protocols for these three core thermochemical conversion pathways, with specific emphasis on their application to glycerol.

Process Fundamentals and Quantitative Comparison

Thermochemical conversion technologies decompose biomass and waste feedstocks through thermal energy into solid, liquid, and gaseous products. The table below summarizes the fundamental operating parameters and primary products for pyrolysis, gasification, and reforming.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Thermochemical Conversion Processes

| Process | Operating Temperature Range (°C) | Operating Atmosphere | Primary Solid Product | Primary Liquid Product | Primary Gaseous Product |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyrolysis | 250 - 700 [16] | Absence of oxygen [15] | Biochar [15] [17] | Bio-oil [15] [17] | Pyrogas (CO, COâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚, CHâ‚„) [15] |

| Gasification | 600 - 1,500 [15] [18] | Limited oxidant (air, Oâ‚‚, steam) [16] | Ash [18] | Tar [18] | Syngas (CO, Hâ‚‚, CHâ‚„) [18] [16] |

| Reforming | >500 (Steam) [15] [10] | Steam, COâ‚‚ | - | - | Hâ‚‚, CO, COâ‚‚ [10] |

The composition and yield of products are highly dependent on the process parameters and feedstock composition. For instance, in gasification, the choice of gasifying agent significantly impacts the heating value of the syngas; using air typically yields a gas with 4-7 MJ/Nm³, while using oxygen and steam can produce a gas with 10-18 MJ/Nm³ [16]. In pyrolysis, the process can be classified as slow, intermediate, or fast based on the heating rate, which influences whether the main product is biochar, bio-oil, or gas [15] [17].

Detailed Process Pathways and Workflows

Pyrolysis Pathway

Pyrolysis is the thermal decomposition of biomass in the complete absence of oxygen. The following diagram illustrates the general pathway from feedstock to products, highlighting the influence of key process conditions.

Gasification Pathway

Gasification converts carbonaceous materials into a primarily gaseous product through partial oxidation. The process occurs in multiple stages, as shown below.

Glycerol Reforming for Hydrogen Production

Steam reforming is a key catalytic process for converting glycerol into hydrogen-rich syngas. The general reaction is represented as C₃H₈O₃ + 3H₂O → 3CO₂ + 7H₂. The experimental workflow for conducting glycerol steam reforming is detailed below.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Catalytic Steam Reforming of Glycerol in a Fixed-Bed Reactor

This protocol describes a methodology for producing hydrogen via catalytic steam reforming of glycerol.

4.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Glycerol Reforming Experiments

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Glycerol Feedstock | Crude or pure glycerol (≥99%) | Primary reactant for hydrogen production. |

| Catalyst | Nickel-based (e.g., Ni/Al₂O₃), Pt, Rh | Lowers activation energy, promotes C-C bond cleavage and water-gas shift reaction. |

| Diluent/Support | Al₂O₃, SiO₂, ZrO₂ | Provides high surface area for catalyst dispersion and stability. |

| Water | Deionized water | Steam source for the reforming reaction. |

| Carrier Gas | Nitrogen (Nâ‚‚), Argon (Ar) | Inert atmosphere for reactor purging and process initialization. |

4.1.2 Procedure

Catalyst Preparation and Loading:

- Synthesize or procure a supported metal catalyst (e.g., 10-15 wt% Ni on γ-Al₂O₃).

- Sieve the catalyst to a specific particle size range (e.g., 150-300 μm).

- Load the catalyst into the isothermal zone of a fixed-bed tubular reactor (typically quartz or stainless steel). Use an inert material like quartz wool to hold the catalyst bed in place.

System Preparation and Leak Check:

- Connect all gas lines and the water feed system. Ensure the reactor is equipped with a temperature-controlled furnace.

- Pressurize the system with an inert gas (Nâ‚‚) to a pressure slightly above the intended operating pressure and check for leaks.

Catalyst Pre-Treatment (Reduction):

- Purge the system with an inert gas.

- Heat the reactor to the catalyst reduction temperature (e.g., 500-700°C for Ni-based catalysts) at a controlled heating rate (e.g., 5-10°C/min) under a flow of hydrogen (e.g., 10-50% H₂ in N₂) for a specified duration (e.g., 2-4 hours).

Glycerol-Water Feed Preparation and Vaporization:

- Prepare an aqueous glycerol solution at the desired steam-to-carbon (S/C) molar ratio. A typical S/C ratio ranges from 3 to 12 [10].

- Use a high-pressure liquid pump to feed the solution into a vaporization chamber maintained at a temperature above the boiling point of the mixture (e.g., 200-300°C) before it enters the catalytic reactor.

Reaction and Data Collection:

- Once the reactor reaches the target reforming temperature (typically >500°C), switch the feed from the inert gas to the vaporized glycerol-water mixture.

- Maintain steady-state conditions for a period sufficient to collect performance data (e.g., 2-6 hours).

- The product gas stream exiting the reactor should be condensed to remove liquids (water and unconverted organics), and the non-condensable gases should be directed to an online gas analyzer (e.g., Gas Chromatograph) for composition analysis.

Product Analysis and Performance Calculation:

- Analyze the composition of the dry gas product to determine the concentrations of Hâ‚‚, CO, COâ‚‚, and CHâ‚„.

- Calculate key performance metrics:

- Glycerol Conversion (%):

(1 - [moles of carbon in outlet liquids / moles of carbon in inlet glycerol]) * 100 - Hâ‚‚ Yield (mol Hâ‚‚/mol glycerolfed):

(Total moles of Hâ‚‚ produced) / (Moles of glycerol fed) - Hâ‚‚ Selectivity (%):

(Moles of Hâ‚‚ produced) / (Theoretical maximum moles of Hâ‚‚ based on converted glycerol) * 100

- Glycerol Conversion (%):

Protocol: Two-Stage Pyrolysis and Reforming of Biomass

This protocol involves pyrolysis of biomass to produce volatile pyrolysis gases (pyrogas), followed by the catalytic reforming of these vapors to enhance hydrogen yield [15].

First Stage - Biomass Pyrolysis:

- Load a biomass feedstock (e.g., pine sawdust, ground to <1 mm) into the first reactor.

- Conduct slow or fast pyrolysis under an inert atmosphere (N₂) at a temperature between 400-600°C. The volatile gases and vapors produced are carried directly into the second reactor.

Second Stage - Catalytic Reforming:

- Direct the hot pyrolysis vapors from the first reactor into a second reformer reactor containing a suitable catalyst (e.g., Ni-based, dolomite, or noble metal catalysts).

- Operate the reformer at a higher temperature, typically between 700-900°C [15]. Introduce steam directly into the reformer if steam reforming is desired.

- The catalyst facilitates the cracking of heavy tars and the reforming of light hydrocarbons, thereby increasing the yield of hydrogen and syngas.

Product Collection and Analysis:

- After the reformer, the gas stream is cooled to condense any remaining liquids.

- The volume and composition of the final gas product are measured, and the condensed liquids are analyzed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Analytical Methods

To accurately evaluate process efficiency and product quality, researchers should employ the following analytical techniques:

- Gas Chromatography (GC): Equipped with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) for permanent gases (Hâ‚‚, CO, COâ‚‚, CHâ‚„) and a Flame Ionization Detector (FID) for light hydrocarbons. Essential for determining gas yield and composition [10].

- Reflectance Spectrophotometry: Used for colorimetric analysis in material science applications, such as measuring color changes in thermochromic materials, which can be relevant for temperature-sensing applications in reactors [19].

- Proximate and Ultimate Analysis: Standard methods for characterizing solid feedstocks and products like biochar. Proximate analysis determines moisture, volatile matter, fixed carbon, and ash content. Ultimate analysis provides the elemental composition (C, H, N, S, O) [17].

- Calorimetry: Used to determine the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of solid and liquid fuels.

Pyrolysis, gasification, and steam reforming represent a suite of versatile thermochemical technologies for converting diverse feedstocks, including waste biomass and glycerol, into clean energy carriers like hydrogen. The successful application and optimization of these technologies rely on a deep understanding of the intricate relationships between feedstock properties, process parameters, catalyst selection, and reactor design. The protocols and guidelines provided herein offer a foundation for researchers to conduct rigorous experiments, gather reproducible data, and contribute to the advancement of sustainable hydrogen production, ultimately supporting the transition to a circular and low-carbon energy economy.

The transition towards a sustainable energy future has positioned hydrogen as a crucial energy carrier due to its high energy density and zero-carbon emissions upon combustion. Catalytic reforming of renewable feedstocks presents a viable pathway for sustainable hydrogen production. Among these feedstocks, glycerol—a major byproduct of biodiesel production—has garnered significant research interest for its potential valorization through thermochemical conversion processes [10]. This review examines three prominent catalytic reforming technologies for hydrogen production from glycerol: Steam Reforming (SR), Aqueous Phase Reforming (APR), and Supercritical Water Reforming (SCWR). Each method offers distinct mechanisms, operational requirements, and catalytic considerations, which are detailed herein to guide researchers in selecting and optimizing these technologies for specific applications.

Process Fundamentals and Comparative Analysis

Theoretical Foundations and Reaction Mechanisms

The catalytic reforming of glycerol aims to break chemical bonds and facilitate reactions that maximize hydrogen yield while minimizing undesirable byproducts.

Aqueous Phase Reforming (APR): This process occurs in the liquid phase at relatively low temperatures (200-250°C) and high pressures (20-60 bar) [20] [21]. The overall reaction can be represented as:

C₃H₈O₃ (l) + 3H₂O (l) → 3CO₂ + 7H₂(ΔH° = +348.1 kJ/mol) [20] The mechanism proceeds through two key steps: initial decomposition of glycerol into CO and H₂, followed by the water-gas shift (WGS) reaction that consumes CO with water to produce additional H₂ and CO₂ [21] [22]. An ideal APR catalyst must effectively cleave C-C bonds while minimizing C-O bond scission to prevent alkane formation and promote the WGS reaction [20] [21].Steam Reforming (SR): Operating at higher temperatures (480-900°C) and typically at atmospheric pressure, SR is highly endothermic [14] [23]. The overall SR reaction is:

C₃H₈O₃ (g) + 3H₂O (g) → 3CO₂ + 7H₂(ΔH° = +123 kJ/mol) [14] The process likely occurs through glycerol decomposition followed by the WGS reaction [23]. The high temperatures often lead to undesirable side reactions, including glycerol pyrolysis and methanation, which consume hydrogen and form coke [14].Supercritical Water Reforming (SCWR): This process utilizes water above its critical point (T > 374°C, P > 221 bar) as the reaction medium [24] [25]. Under these conditions, water exhibits unique properties—low dielectric constant, high diffusivity, and excellent solubility for organic compounds—that facilitate efficient gasification of wet biomass without energy-intensive drying [24]. SCWR can achieve high hydrogen production rates, particularly with catalytic enhancement.

Comparative Process Characteristics

Table 1: Comparative analysis of glycerol reforming processes.

| Parameter | Aqueous Phase Reforming (APR) | Steam Reforming (SR) | Supercritical Water Reforming (SCWR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Range | 200-250°C [20] | 480-900°C [14] [23] | >374°C (typically 400-700°C) [24] [25] |

| Pressure Range | 20-60 bar [20] | Atmospheric [23] | >221 bar (typically 250-300 bar) [24] [25] |

| Phase of Reactants | Liquid [21] | Gas [14] | Supercritical fluid [24] |

| Energy Requirements | Lower (no vaporization needed) [22] | Higher (high T required) [14] | Moderate to high (high P required) [24] |

| Hydrogen Yield | Moderate | High | High [24] |

| Key Challenges | Catalyst leaching, competing reactions | Coke formation, sintering | Reactor corrosion, salt precipitation [25] |

| IAA65 | IAA65, MF:C16H13F6NO2, MW:365.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Thioridazine | Thioridazine, CAS:130-61-0; 50-52-2, MF:C21H26N2S2, MW:370.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Process Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting an appropriate reforming technology based on feedstock characteristics and research objectives:

Catalyst Systems and Performance

Catalyst Formulations and Support Materials

Catalyst design is crucial for optimizing hydrogen yield and process efficiency across all reforming technologies.

Noble Metal Catalysts: Pt, Ru, and Rh-based catalysts demonstrate high activity and excellent coke resistance but suffer from high cost and limited availability [21] [14]. For SR, Ru/Al₂O₃ has been extensively studied, with reported activation energies of approximately 19-21 kJ/mol [26] [14].

Non-Noble Transition Metal Catalysts: Ni-based catalysts are widely investigated due to their exceptional C-C bond cleavage capability and cost-effectiveness [20] [14] [22]. However, Ni catalysts are prone to deactivation via coke deposition and sintering [14]. The incorporation of promoters such as Co, Cu, Mg, Ca, La, or Ce enhances catalytic performance by improving metal dispersion, reducing acidity, and increasing resistance to carbon formation [20] [14] [22].

Support Materials: The support significantly influences metal dispersion, stability, and catalytic activity. γ-Al₂O₃ is commonly used due to its high surface area, but it can undergo phase transformation under reaction conditions [20]. Support modification with basic oxides (MgO, CaO, CeO₂) or lanthanides (La, Ce) neutralizes acidic sites, suppresses coke formation, and promotes the WGS reaction [20] [21] [22].

Catalytic Performance Metrics

Table 2: Catalyst performance in glycerol reforming processes.

| Process | Catalyst | Optimal Conditions | Hydrogen Yield/Production | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APR | Ni-Co/γ-Al₂O³ [20] | 238°C, 37 bar | Improved H₂ production with La, Ce, Ca, Mg promoters | Support modification with lanthanides and alkaline earth metals enhanced H₂ yield |

| APR | Ni/Al-Ca [22] | 238°C, 37 bar | 188 mg H₂/mol C fed | Basic sites from Ca improved performance with refined crude glycerol |

| APR | Pt-Ni/γ-Al₂O₃ [21] | ~240°C | Higher activity than monometallic catalysts | Bimetallic catalysts showed improved performance |

| SR | Ni-Cu/MgO [14] | 480-580°C, atmospheric | Power law kinetics studied | Cu addition mitigated coke formation; MgO basicity beneficial |

| SR | Ni-promoted metallurgical residue [23] | 480-580°C, atmospheric | Activation energy: 66.1 kJ/mol | Waste-derived catalyst showed promising activity |

| SCWR | Co-based catalysts [24] | 400°C, 45 min | Enhanced H₂ production in glycerol-methanol-water mixture | Effective for wet microalgae biomass gasification |

| SCWR | Ru/TiO₂, Ni/Al₂O₃, K₂CO₃ [24] | 400-700°C | Complete gasification at 700°C with Ru/TiO₂ | Catalysts improved gasification efficiency and H₂ yield |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Catalyst Synthesis Protocols

This synthesis method aims to achieve high metal dispersion and strong metal-support interaction.

- Materials: γ-Al₂O₃ support (35-80 mesh), Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, urea (all ACS reagents), glycerol (99.5%)

- Procedure:

- Support Pretreatment: Thermally stabilize γ-Al₂O₃ at 600°C for 2 hours

- Impregnation Solution: Prepare aqueous solution containing Ni nitrate, Co nitrate, and urea in appropriate ratios

- Incipient Wetness Impregnation: Add solution dropwise to stabilized support until pore saturation

- Controlled Combustion: Heat impregnated material gradually to 450°C at 5°C/min, hold for 30 minutes

- Reduction: Reduce catalyst under H₂ flow (100 mL/min) at 500°C for 1 hour before reaction testing

- Key Considerations: Controlled heating rate prevents rapid temperature spikes, preserving support texture and enhancing metal anchoring

- Procedure:

- Prepare aqueous solutions of Ni, Al, and Ca nitrate precursors

- Simultaneously add solutions to precipitating vessel under constant stirring

- Maintain pH constant using alkaline precipitating agent (e.g., Na₂CO₃)

- Age precipitate for several hours, then filter and wash thoroughly

- Dry at 100-120°C, then calcine at 675°C for 4 hours

Catalytic Testing Protocols

- Reactor Setup: High-pressure fixed-bed reactor (typically tubular, stainless steel)

- Standard Conditions:

- Temperature: 238°C

- Pressure: 37-39 bar

- Glycerol concentration: 5 wt% in deionized water

- Catalyst mass: Varies to achieve weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 2.45-4.90 hâ»Â¹

- Procedure:

- Load catalyst into reactor (typical bed volume: 2-5 mL)

- Pressurize system with inert gas (Nâ‚‚) and heat to reaction temperature

- Feed glycerol solution using high-pressure liquid pump

- Maintain steady-state for 3+ hours before product analysis

- Analyze gaseous products by online GC-TCD, liquid products by GC-MS or HPLC

- Product Analysis:

- Gas composition: Hâ‚‚, COâ‚‚, CO, CHâ‚„ quantified by GC-TCD

- Liquid phase: Analyze for unconverted glycerol, intermediate oxygenates

- Reactor Setup: Fixed-bed quartz reactor at atmospheric pressure

- Standard Conditions:

- Temperature: 480-580°C

- Catalyst mass: 0.1-0.5 g

- Glycerol solution feed: 0.05-0.11 mL/min (10-25 wt% in water)

- Carrier gas: Nâ‚‚ or He (20-50 mL/min)

- Procedure:

- Pre-reduce catalyst in situ under H₂ flow at 500-600°C

- Vary temperature and feed rate for kinetic data collection

- Analyze effluent gases by online GC

- Determine glycerol conversion and product selectivities

- Kinetic Analysis:

- Apply power-law or Langmuir-Hinshelwood models

- Calculate activation energies from Arrhenius plots

Catalyst Characterization Techniques

A comprehensive characterization protocol is essential for understanding structure-activity relationships.

- Textural Properties: Nâ‚‚ physisorption for surface area, pore volume, and pore size distribution (BET method)

- Crystalline Structure: X-ray diffraction (XRD) for phase identification, crystallite size calculation (Scherrer equation)

- Metal Dispersion: Hâ‚‚ temperature-programmed reduction (Hâ‚‚-TPR) for reducibility and metal-support interactions

- Surface Acidity/Basicity: NH₃/CO₂ temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) for acid/base site strength and distribution

- Morphology: Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) for elemental mapping

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for glycerol reforming studies.

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Precursors | Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O [20] [27] | Source of active metals | High purity (>99%) to avoid impurities affecting performance |

| Support Materials | γ-Al₂O₃ (spheres/powder) [20] [27] | High surface area support | Specific surface area ~210 m²/g, controlled pore size distribution |

| Promoters | La(NO₃)₃·6H₂O, Ce(NO₃)₃·6H₂O, Ca(NO₃)₂·4H₂O, Mg(NO₃)₂·6H₂O [20] | Enhance stability/selectivity | Modify acid-base properties, improve metal dispersion |

| Organic Fuels | Urea (>98%) [27] | Combustion synthesis fuel | Creates nano-structured catalysts with high surface area |

| Feedstock | Glycerol (>99.5%) [22] [27] | Reactant for reforming processes | High purity for baseline studies; crude glycerol for application tests |

| Reference Catalysts | Pt/γ-Al₂O₃, Ru/Al₂O₃ [21] [26] | Benchmark performance | Noble metal benchmarks for comparison with transition metal catalysts |

| Oxprenolol | Oxprenolol, CAS:6452-71-7; 6452-73-9, MF:C15H23NO3, MW:265.35 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| BAY 3389934 | BAY 3389934, MF:C26H30ClN5O7S2, MW:624.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Reaction Kinetics and Mechanism Elucidation

Kinetic Modeling Approaches

Kinetic studies are fundamental for reactor design and process scale-up, with different models applied across the reforming processes.

Power Law Models: Empirical models frequently used for SR kinetics, expressing reaction rate as

r = k·[Glycerol]^nwhere n is the reaction order (typically 0.6-1.1 for SR) [14] [23]. Activation energies for SR range widely from 19 kJ/mol for Ru/Al₂O₃ to 103 kJ/mol for Ni/CeO₂, reflecting differences in rate-determining steps and catalyst properties [26] [14].Langmuir-Hinshelwood-Hougen-Watson (LHHW) Models: Mechanistic models based on adsorbed surface intermediates. For SR, proposed mechanisms include dual-site molecular adsorption of glycerol and steam, with glycerol dehydrogenation as the potential rate-determining step [14] [23].

Eley-Rideal Models: Assume reaction between adsorbed glycerol and gaseous water molecules, sometimes reduced to power lawå½¢å¼ at low glycerol partial pressures [26].

Process Integration and Reactor Design Considerations

Advanced reactor configurations can enhance process efficiency and hydrogen yields.

Membrane Reactors: Pd-based membrane reactors for SR simultaneously extract high-purity hydrogen and shift equilibrium toward increased conversion and hydrogen yield by product removal [10].

Sorption-Enhanced Reactors: Incorporate COâ‚‚ sorbents to remove carbon dioxide in situ, driving equilibrium toward hydrogen production and enabling lower operating temperatures [23].

Continuous-Flow Systems: Fixed-bed reactors are standard for continuous APR and SR operations, requiring careful attention to catalyst bed design, heat transfer, and pressure control [20] [22].

The catalytic reforming of glycerol presents a promising route for sustainable hydrogen production while adding value to biodiesel industry byproducts. Each technology—APR, SR, and SCWR—offers distinct advantages and limitations, with the optimal choice dependent on specific research objectives, feedstock characteristics, and available resources. APR operates at energetically favorable low temperatures but faces challenges with catalyst leaching and competing reactions. SR provides high hydrogen yields but requires significant energy input and suffers from catalyst deactivation. SCWR efficiently processes high-moisture feedstocks but demands specialized high-pressure equipment. Future research directions should focus on developing cost-effective, stable catalyst systems with enhanced resistance to deactivation; optimizing reactor configurations and process integration strategies; advancing kinetic understanding and mechanistic studies; and exploring the utilization of crude glycerol feedstocks with minimal purification.

Advanced Reforming Techniques and Catalyst Design for Maximizing Hydrogen Yield

The steam reforming (SR) of glycerol represents a promising pathway for sustainable hydrogen production, aligning with global efforts to develop clean energy alternatives. This process utilizes glycerol, a major by-product of the biodiesel industry, transforming a waste product into a valuable energy carrier [12] [10]. For every 100 kg of biodiesel produced, approximately 10 kg of glycerol is generated, creating a plentiful and economically viable feedstock [10] [28]. The optimal use of glycerol not only promotes the sustainable development of the biodiesel industry but also addresses current environmental challenges, contributing to a circular economy [29] [12].

This analysis details the reaction mechanisms, stoichiometry, and experimental protocols for glycerol steam reforming (GSR), framed within broader research on the thermochemical conversion of glycerol for hydrogen production.

Reaction Network and Stoichiometry

The glycerol steam reforming process involves a complex network of simultaneous and competing reactions. The overall goal is to convert glycerol and steam into a hydrogen-rich syngas.

Primary Reactions

The process is primarily described by two key reactions:

Glycerol Decomposition (GD):

C3H8O3 3CO + 4H2(ΔH0 = +251 kJ/mol)[30] This endothermic reaction is the initial decomposition step of glycerol.Water-Gas Shift (WGS):

CO + H2O CO2 + H2(ΔH0 = -41 kJ/mol)[30] This slightly exothermic reaction consumes the CO produced from decomposition, generating additional H2 and converting steam to CO2.

The combination of these two reactions gives the overall, highly endothermic, steam reforming reaction [9] [30]:

- Overall Glycerol Steam Reforming (GSR):

C3H8O3 + 3H2O 3CO2 + 7H2(ΔH0 = +123 kJ/mol)

This stoichiometry indicates a maximum theoretical hydrogen yield of 7 moles of H2 per mole of glycerol consumed [31] [9].

Competing and Side Reactions

In practice, the theoretical yield is seldom achieved due to several competing side reactions that consume hydrogen or lead to catalyst deactivation. Key among these are:

Methanation Reactions:

CO + 3H2 CH4 + H2O[9] [30]CO2 + 4H2 CH4 + 2H2O[9] [30] These exothermic reactions reduce the overall H2 yield by converting syngas into methane.Coke Formation Reactions: Carbon deposition, or coking, is a primary cause of catalyst deactivation. It can occur through multiple pathways, including [9]:

2CO C + CO2(Boudouard Reaction)CO + H2 C + H2OCH4 C + 2H2(Methane Cracking)

The following diagram illustrates the core reaction network of glycerol steam reforming, highlighting the pathways to desired products and deactivating side reactions.

Quantitative Process Performance

The performance of GSR is highly dependent on process conditions and catalyst formulation. The tables below summarize key quantitative data from recent studies.

Table 1: Influence of Process Parameters on GSR Performance (Theoretical and Experimental)

| Parameter | Conditions | Hâ‚‚ Yield (mol Hâ‚‚/ mol Glycerol) | Hâ‚‚ Purity (%) | Key Observations | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Maximum | - | 7.0 | - | Based on full conversion & no side reactions. | [31] [9] |

| Temperature | 850 °C | - | ~70-90% | High temperature favors H₂ production and purity. | [9] [30] |

| Catalyst (12% NiO/5% La₂O₃) | 850 °C, S/C: 0.7 | - | - | Optimal conditions for continuous 9h operation in a pilot plant. | [30] |

| Sorption Enhanced Membrane Reactor | 800 K, WGFR: 9, 1 atm | 7.0 | ~100% | Simultaneous Hâ‚‚ & COâ‚‚ removal achieves theoretical max yield. | [31] |

Table 2: Performance of Different Catalyst Supports in GSR

| Catalyst Support | Active Metal | Hâ‚‚ Purity (%) | Key Advantages & Challenges | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dolomite | Ni | Up to 90% | High porosity and COâ‚‚ capture capacity (recarbonation of CaO) enhances Hâ‚‚ purity. | [9] |

| γ-Alumina (Al₂O₃) | Ni | ~70% | Common commercial support; prone to deactivation via coking and Ni sintering. | [29] [9] |

| Activated Carbon (AC) | Ni | - | Large surface area; popular as alternative support. | [29] |

| Carbon Nanofibers (CNF) | Ni (encapsulated) | - | Produces high-purity Hâ‚‚; suitable for co-production of carbon nanotubes. | [29] |

| Zeolite | None | 51% | Low performance due to amorphization at high temperatures. | [9] |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides a detailed methodology for conducting glycerol steam reforming experiments in a fixed-bed reactor system, a common setup for catalyst evaluation and kinetic studies.

Catalyst Preparation: Wet Impregnation of Ni/Al₂O₃ Catalyst

A typical procedure for preparing a supported Ni catalyst is as follows [29]:

- Support Preparation: Weigh the desired amount of γ-Al₂O₃ support. Calcine it in a muffle furnace at 500 °C for 4 hours to remove any volatile contaminants and stabilize the surface.

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve the required mass of nickel precursor, typically nickel nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), in deionized water to achieve a solution concentration that will yield the target metal loading (e.g., 10-12 wt.% Ni).

- Impregnation: Add the γ-Al₂O₃ support to the nickel nitrate solution under continuous stirring. Maintain the mixture at room temperature for 12 hours to allow for adequate immersion and adsorption of the metal precursor onto the support.

- Drying: Remove excess water by drying the impregnated solid in an oven at 100-120 °C for 10-12 hours.

- Calcination: Place the dried material in a furnace and calcine in air at 400-500 °C for 4-5 hours to decompose the nickel nitrate into nickel oxide (NiO).

- Reduction (Pre-reduction): Prior to the reaction, reduce the calcined catalyst in a reactor under a flow of hydrogen (e.g., 50 ml/min) at 600-700 °C for 2 hours to activate the catalyst by converting NiO to metallic Ni.

Glycerol Steam Reforming in a Fixed-Bed Reactor

The following protocol describes the experimental setup and procedure for evaluating catalyst performance [29] [30].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specification/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Glycerol Solution | Feedstock for the reforming reaction. | Aqueous solution, typically with a Water-to-Glycerol Feed Ratio (WGFR) of 6-9 [31] [30]. |

| Ni-based Catalyst | To catalyze the cleavage of C-C, O-H, C-H bonds and the water-gas shift reaction. | e.g., 10-12 wt.% Ni on Al₂O₃, dolomite, or other supports [29] [9] [30]. |

| Fixed-Bed Tubular Reactor | Vessel where the high-temperature reforming reaction takes place. | Typically made of quartz or stainless steel, placed inside a temperature-controlled furnace. |

| Carrier Gas | To maintain an inert atmosphere and assist in product gas transport. | Nitrogen (Nâ‚‚) or Argon [31]. |

| Temperature Controller | To provide and maintain the required reaction temperature. | High-temperature furnace capable of reaching 850 °C [30]. |

| Liquid Feed Pump | To deliver the glycerol-water feed solution at a precise and constant flow rate. | Syringe pump or HPLC pump [30]. |

| Vaporization Chamber | To instantly vaporize the liquid feed before it enters the catalytic bed. | Heated zone upstream of the reactor. |

| Gas Analysis System | To monitor the composition of the product gas in real-time. | Online Gas Chromatograph (GC) equipped with a TCD detector. |

Experimental Workflow:

The workflow for a standard GSR experiment is visualized below, from catalyst loading to data analysis.

Procedure:

- Reactor Loading and Sealing: Pack the reduced or pre-calcined catalyst (0.2 - 0.5 g) into the middle of the fixed-bed reactor, typically using quartz wool to hold the bed in place. Assemble and seal the reactor system.

- System Purge and Pressure Check: Purge the system with an inert gas (Nâ‚‚) to remove air. Conduct a pressure check to ensure the system is leak-free.

- Catalyst Activation (If not pre-reduced): Switch the gas flow to H₂ (e.g., 50 ml/min). Heat the reactor to the reduction temperature (600-700 °C) at a controlled heating rate (e.g., 5 °C/min) and hold for 2 hours to fully reduce the catalyst.

- System Stabilization: Switch the gas flow back to N₂ (carrier gas) and set the flow rate. Heat the reactor to the target reaction temperature (e.g., 600-850 °C). Simultaneously, pre-heat the vaporization chamber to a temperature sufficient to instantly vaporize the liquid feed (e.g., 300-400 °C).

- Initiating the Reaction: Once temperatures are stable, start the liquid feed pump to introduce the glycerol-water solution at the predetermined flow rate (e.g., 40 mL/min [30]) and WGFR (e.g., 0.7-9 [31] [30]).

- Product Analysis and Data Collection: The product gases (Hâ‚‚, COâ‚‚, CO, CHâ‚„) exit the reactor, pass through a condenser to remove any unreacted water and heavy compounds, and are then analyzed by an online Gas Chromatograph (GC). Data on gas composition and flow rate are recorded at regular intervals.

- Performance Calculation: Calculate key performance metrics from the GC data.

- Glycerol Conversion (%):

(1 - (moles of glycerol out / moles of glycerol in)) * 100 - Hâ‚‚ Yield (mol Hâ‚‚ / mol Glycerol in):

(Total moles of Hâ‚‚ produced) / (moles of glycerol fed) - Hâ‚‚ Selectivity (%):

(Moles of Hâ‚‚ produced) / (Total moles of all gaseous products) * 100

- Glycerol Conversion (%):

Glycerol steam reforming is a technologically viable process for producing renewable hydrogen. Its efficiency is governed by a complex reaction network where the main reforming and water-gas shift reactions compete with methanation and coking pathways. The choice of catalyst, particularly the support material, and precise control over operating parameters such as temperature and steam-to-carbon ratio are critical to maximizing hydrogen yield and purity while ensuring catalyst stability. The experimental protocols outlined provide a foundation for rigorous research and development in this field, contributing to the advancement of glycerol biorefining and sustainable hydrogen production.

The thermochemical conversion of glycerol for hydrogen production presents a sustainable pathway to valorize a major byproduct of the biodiesel industry. Among various catalytic systems, nickel-based catalysts have emerged as the most commercially viable option due to their high activity for C-C bond cleavage, affordability, and widespread availability. This document provides a detailed technical overview of nickel-based catalyst systems, focusing on the critical roles of promoters and support materials in enhancing catalytic performance, stability, and hydrogen selectivity for glycerol reforming processes.

Catalyst Design and Composition

The performance of nickel-based catalysts in glycerol reforming is governed by their structural and compositional properties. Key design parameters include the choice of support material, nickel precursor, calcination conditions, and the incorporation of promoters.

Support Materials

The support material significantly influences metal dispersion, stability, and catalytic activity. The following table summarizes the properties and performance of common support materials used in nickel-based glycerol reforming catalysts.

Table 1: Characteristics and Performance of Common Support Materials for Nickel-Based Catalysts in Glycerol Reforming

| Support Material | Key Characteristics | Reported Hâ‚‚ Purity/Performance | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alumina (Al₂O₃) | High surface area, acidic properties, common commercial support | ~70% H₂ purity at 850°C [9] | Good metal dispersion, widely available | Prone to coke deposition and Ni sintering [9] |

| Dolomite | High porosity, CO₂ capture capacity, basic properties | Up to 90% H₂ purity with Ni loading at 850°C [9] | Enhances purity via recarbonation, reduces coke | Less explored, structural stability at high T |

| Ceria (CeO₂) | Excellent redox properties, oxygen storage capacity, generates oxygen vacancies | 70% H₂ selectivity at 600°C [32] | Promotes water dissociation, removes carbon deposits, strong Ni-support interaction | Complex preparation methods often required |

| Silica-Carbon Composite (SiOâ‚‚-C) | Mesoporous structure, high thermal stability under hydrothermal conditions | High selectivity to 1,2-propylene glycol in hydrogenolysis [33] | Stable under reaction conditions, suitable for liquid-phase processes | Lower surface area (~200 m² gâ»Â¹) [33] |

| Carbon Nanofibers (CNF) | High surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, structural stability | Enables co-production of Hâ‚‚ and carbon nanotubes [29] | High stability, uniform metal distribution, facilitates electron transport | Specialized synthesis required (electrospinning) [34] |

| Zeolite | Natural material, crystalline structure | 51% H₂ concentration at 850°C [9] | Low cost | Amorphization at high temperatures, low effectiveness |

Promoters and Alloys

The incorporation of secondary metals as promoters or through alloy formation can significantly enhance the performance of nickel catalysts:

- Copper (Cu): Ni-Cu bimetallic catalysts are frequently employed to adjust activity, selectivity, and stability. The modification of reaction mechanisms by varying catalyst morphology and composition is crucial for directing product selectivity [35].

- Chromium (Cr): Ni-NiCr alloy nanoparticles incorporated into graphitic carbon nanofibers demonstrate exceptional electrocatalytic activity for glycerol oxidation, achieving current densities of 102.7 mA cmâ»Â² in alkaline media. Chromium enhances electronic properties and corrosion resistance [34].

- Manganese (Mn): Mn acts as a promoter in Ni/MgO catalysts for glycerol dry reforming, engineering Ni-oxygen vacancy interfaces to boost activity and reduce coking [36].

- Lanthanides and Alkaline Earth Metals: Metals such as La, Ce, Mg, and Ca are used to modify support basicity, which promotes COâ‚‚ activation and helps oxidize deposited coke [9].

Experimental Protocols

Catalyst Synthesis Methods

Incipient Wetness Impregnation of Ni/SiOâ‚‚-C Catalysts

- Principle: A precursor solution is added to a support until pore saturation is achieved, ensuring uniform distribution.

- Materials: SiO₂-C composite support, nickel precursors (NiCl₂·6H₂O, Ni(CH₃COO)₂·4H₂O, or Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), ethanol solvent.

- Procedure:

- Dissolve the selected Ni precursor in ethanol (volume equal to support pore volume).

- Gradually add the solution to the SC support under continuous stirring.

- Age the impregnated material for 24 hours at room temperature.

- Dry at 100°C for 12 hours.

- Calcinate at 300°C for 3 hours under controlled atmosphere (Ar, air, or N₂) [33].

Electrospinning of Ni-NiCr-Carbon Nanofibers

- Principle: Utilizing high voltage to create polymer fibers embedded with metal precursors, followed by thermal treatment to form alloy nanoparticles in a carbon matrix.

- Materials: Nickel(II) acetate tetrahydrate, chromium(II) acetate hydrate, poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA), deionized water.

- Procedure:

- Dissolve 1 g nickel acetate in 5 mL DI water and add chromium acetate (5-35 wt% relative to Ni).

- Mix with 15 mL of 10 wt% aqueous PVA solution. Stir at 50°C for 5 hours.

- Electrospin the solution at 20 kV, with a tip-to-collector distance of 15 cm and feed rate of 0.07 mL hâ»Â¹.

- Collect nanofiber mats on aluminum foil and vacuum-dry at 60°C overnight.

- Calcinate under vacuum at 850°C with a heating rate of 2°C minâ»Â¹ and a holding time of 5 hours [34].

Rapid Calcination of Ni/CeOâ‚‚ Catalysts

- Principle: Short-duration, high-temperature treatment to create structural defects and enhance metal-support interaction.

- Materials: Ce(NO₃)₃·6H₂O, Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, ethylene glycol, ethanol.

- Procedure:

- Synthesize CeO₂ support via hydrothermal method (150°C for 24 hours).

- Impregnate CeOâ‚‚ with Ni precursor (10 wt% Ni) using wet impregnation.

- For rapid calcination: place the catalyst in a preheated muffle furnace at 500°C for 10 minutes.

- For programmed calcination: heat from room temperature to 500°C at 2°C minâ»Â¹, hold for 3 hours [32].

Catalyst Characterization Techniques

Table 2: Essential Characterization Techniques for Nickel-Based Reforming Catalysts

| Technique | Acronym | Key Information Obtained | Experimental Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| N₂ Physisorption | BET | Specific surface area (Sвᴇт), pore volume, pore size distribution | Analysis at 77 K; degas at 300°C for 3 h [33] [32] |

| Temperature-Programmed Reduction | Hâ‚‚-TPR | Reducibility of metal species, metal-support interaction | 50 mg catalyst, 5% Hâ‚‚/Ar, 30 mL minâ»Â¹, 10°C minâ»Â¹ to 900°C [32] |

| X-Ray Diffraction | XRD | Crystalline structure, phase composition, alloy formation | Cu-Kα radiation (λ=1.5418 Å), 40 kV, 5 mA, 2θ range 5-80° [34] [37] |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy | SEM | Surface morphology, particle distribution, nanofiber structure | JEOL JSM-7610F; resolution ~1 nm [34] [29] |

| Transmission Electron Microscopy | TEM | Nanoparticle size, distribution, alloy formation | FEI Tecnai G2 F20, 200 kV [34] |

| Temperature-Programmed Desorption | COâ‚‚-TPD, NH₃-TPD | Surface basicity/acidity, site strength distribution | 50 mg catalyst, He flow, 10°C minâ»Â¹ to 900°C [37] |

Catalytic Performance Testing

Glycerol Steam Reforming (GSR) Protocol

- Reactor System: Fixed-bed reactor, typically quartz or stainless steel.

- Catalyst Loading: 0.1-0.5 g catalyst, diluted with inert quartz sand.

- Reaction Conditions:

- Product Analysis:

- Online gas analyzer for Hâ‚‚, COâ‚‚, CO, CHâ‚„

- Gas chromatography for detailed hydrocarbon analysis

- Calculation of glycerol conversion, Hâ‚‚ yield, and product selectivity

Glycerol Hydrogenolysis Protocol

- Reactor System: High-pressure batch reactor (Parr reactor).

- Catalyst Loading: 0.1-0.3 g catalyst.

- Reaction Conditions:

- Temperature: 180-250°C

- Hâ‚‚ Pressure: 2-8 MPa

- Reaction time: 4-10 hours

- Glycerol concentration: 10-50 wt% in water [33]

- Product Analysis:

- Liquid products analyzed by HPLC or GC

- Primary products: 1,2-propylene glycol, 1,3-propylene glycol, ethylene glycol, alcohols

Performance Data and Optimization

Effect of Nickel Precursor and Calcination Atmosphere

The choice of nickel precursor and calcination conditions significantly impacts catalyst performance in glycerol hydrogenolysis:

Table 3: Influence of Nickel Precursor and Calcination on Ni/SiOâ‚‚-C Catalyst Performance in Glycerol Hydrogenolysis [33]

| Nickel Precursor | Calcination Atmosphere | Ni Particle Size (nm) | Glycerol Conversion (%) | Selectivity to 1,2-PG (%) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NiCl₂·6H₂O | Ar | 9.0 | 57 | 44 | Forms NiO and Ni silicate species; lowest activity |

| Ni(CH₃COO)₂·4H₂O | Ar | 5.6 | 78 | 71 | Forms only NiO; intermediate performance |

| Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O | Ar | 4.5 | 92 | 84 | Forms only NiO; smallest particles, best performance |

| Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O | Air | 8.5 | 65 | 61 | Larger particles vs. Ar calcination, reduced activity |

| Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O | N₂ | 5.5 | 85 | 79 | Intermediate particles, good performance |

Support Effect on Hydrogen Production and Carbon Deposition

The support material profoundly influences both hydrogen yield and catalyst stability through carbon formation management:

Table 4: Support Effect on Hydrogen Production and Carbon Formation in Glycerol Steam Reforming [9] [29]

| Catalyst | Temperature (°C) | Glycerol Conversion (%) | H₂ Purity (%) | Carbon Deposition | Additional Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni/γ-Al₂O₃ | 850 | ~100 | ~70 | High | - |

| Ni/Dolomite | 850 | ~100 | Up to 90 | Reduced due to COâ‚‚ capture | - |

| Ni/CeOâ‚‚ | 600 | High | 70 (selectivity) | Low due to oxygen mobility | - |

| Ni@CNF | 600-700 | High | High | Directed to CNT growth | Carbon nanotubes |

| Ni/Zeolite | 850 | Moderate | 51 | High (due to amorphization) | - |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Key Reagents and Materials for Nickel-Based Glycerol Reforming Catalyst Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel Nitrate Hexahydrate | Primary Ni precursor | Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O, ≥98.5% [33] | Forms small NiO particles (4.5 nm) after calcination; optimal for high activity |

| Cerium Nitrate Hexahydrate | CeO₂ support precursor | Ce(NO₃)₃·6H₂O, ≥99.5% [32] | Creates redox-active support with oxygen storage capacity |

| Chromium Acetate Hydrate | Co-catalyst precursor | Cr(CH₃COO)₃·xH₂O, ≥99% [34] | Optimized at 15 wt% for Ni-NiCr alloys in electrospun CNFs |

| Poly(vinyl Alcohol) | Electrospinning polymer template | Mw 89,000-98,000, 99% hydrolyzed [34] | Forms continuous nanofibers for catalyst support |

| Carbon Nanofiber Supports | High-surface-area support | PAN-based, diameter 300-400 nm [29] | Enables nanoscale Ni dispersion and CNT co-production |

| Dolomite Support | Natural mineral support | High porosity, COâ‚‚ capture capacity [9] | Enhances Hâ‚‚ purity through in-situ COâ‚‚ removal |

| Nadolol-d9 | Nadolol-d9, MF:C17H27NO4, MW:318.46 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| BCATc Inhibitor 2 | BCATc Inhibitor 2, MF:C16H10ClF3N2O4S, MW:418.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Process Visualization and Workflows

Diagram 1: Catalyst Development Workflow. This workflow outlines the systematic approach to designing, preparing, and optimizing nickel-based catalysts for glycerol reforming.

Diagram 2: Glycerol Reforming Reaction Network and Catalyst Considerations. This diagram illustrates the multiple pathways for glycerol conversion and the key catalyst properties that influence product selectivity and process efficiency.

Nickel-based catalyst systems for glycerol reforming demonstrate remarkable versatility, with performance highly tunable through strategic selection of support materials, promoters, and synthesis conditions. The integration of advanced supports like CeOâ‚‚ for oxygen mobility, carbon composites for stability, and dolomite for COâ‚‚ capture, combined with optimized preparation protocols, enables researchers to design catalysts with enhanced activity, selectivity, and durability. The provided application notes and protocols offer a comprehensive foundation for developing effective nickel-based catalytic systems for sustainable hydrogen production from glycerol, contributing to the advancement of biorefinery concepts and renewable energy technologies.

Application Notes

This document details application notes and experimental protocols for the thermochemical conversion of glycerol into syngas and hydrogen, situating this research within a broader thesis on sustainable hydrogen production. The overproduction of glycerol, a byproduct of biodiesel manufacturing, presents a significant disposal challenge and an opportunity for valorization through pyrolysis and gasification routes [38] [39]. These processes transform low-value crude glycerol into high-value hydrogen or syngas, which are critical feedstocks for the chemical industry and clean energy applications [40].

Pyrolysis involves the thermal decomposition of glycerol in an inert atmosphere to produce a gas rich in syngas (a mixture of Hâ‚‚ and CO) [38]. Gasification, particularly using steam or COâ‚‚ as oxidants, promotes further reforming reactions, significantly enhancing hydrogen yield and adjusting the Hâ‚‚/CO ratio of the syngas for downstream applications like Fischer-Tropsch synthesis [40] [41]. The integration of catalysts is pivotal for improving process efficiency, minimizing carbon deposition, and maximizing gas yields [40] [41].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Glycerol Conversion Pathways

| Parameter | Pyrolysis | Steam Reforming (SR) | Dry Reforming (DR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Reaction | Thermal decomposition in an inert atmosphere | C₃H₈O₃ + 3H₂O → 3CO₂ + 7H₂ |

C₃H₈O₃ + CO₂ → 4CO + 3H₂ + H₂O [40] |

| Oxidant/Medium | None (Nâ‚‚ atmosphere) | Steam (Hâ‚‚O) | Carbon Dioxide (COâ‚‚) |

| Primary Product | Syngas (Hâ‚‚ + CO) & light hydrocarbons [38] | Hydrogen-rich syngas | Syngas with lower Hâ‚‚/CO ratio |

| Typical Catalyst | Non-catalytic or packing materials (Quartz, SiC) [38] | Ni-based (e.g., Ni/CeOâ‚‚) [41] | Ni-based with promoters (e.g., ReNi/CaO) [40] |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity of operation; produces medium heating value gas [39] | High hydrogen yield potential | Consumes COâ‚‚, a greenhouse gas |

Table 2: Quantitative Data from Glycerol Pyrolysis in a Fixed-Bed Reactor [38] [39]

| Temperature (°C) | N₂ Flow (mL/min) | Glycerol Conversion (%) | H₂ (mol%) | CO (mol%) | Syn Gas (mol%) | Product Gas Volume (L/g glycerol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 650 | 50 | 46.7 | 29.5 | 37.2 | 70.0 | 0.75 |

| 700 | 50 | 64.8 | 35.2 | 42.1 | 79.7 | 1.01 |

| 750 | 50 | 85.9 | 40.1 | 45.3 | 87.8 | 1.22 |

| 800 | 50 | ~100 | 44.2 | 49.3 | 93.5 | 1.32 |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Non-Catalytic Pyrolysis of Glycerol

This protocol describes the setup and procedure for pyrolyzing glycerol to produce syngas in a fixed-bed reactor, adapted from Valliyappan et al. (2008) [38] [39].

Materials and Equipment

- Reactor System: A continuous down-flow fixed-bed micro reactor (e.g., Inconel alloy tube, 500 mm length, 10.5 mm internal diameter) housed in a temperature-controlled furnace.

- Packing Material: Quartz wool, and particles of quartz, silicon carbide, or Ottawa sand (particle diameters 1-2 mm or 3-4 mm).

- Feed System: A syringe or HPLC pump for controlled glycerol feed.

- Gases: Nitrogen (Nâ‚‚), carrier grade.

- Glycerol: Pure glycerol (>99%).

- Product Analysis: Gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) for analyzing gas composition (Hâ‚‚, CO, COâ‚‚, CHâ‚„, Câ‚‚Hâ‚„).

Detailed Procedure

- Reactor Packing: Place a plug of quartz wool at the bottom of the vertical reactor tube. Fill the reactor tube with the selected packing material (e.g., 3-4 mm quartz particles) to a bed height of 70 mm.

- System Check: Pressurize the system with Nâ‚‚ to check for leaks. Purge the system with Nâ‚‚ at the desired flow rate (e.g., 30-70 mL/min) for at least 30 minutes to ensure an oxygen-free environment.

- Heating: Ramp the furnace temperature to the target pyrolysis temperature (650-800°C) under a continuous N₂ flow.

- Glycerol Feeding: Once the temperature stabilizes, initiate the continuous feed of glycerol. A typical feed concentration is 72 wt% glycerol in water, fed at a rate of 0.18 cm³/min.

- Reaction and Product Collection: Allow the reaction to proceed for a set residence time (e.g., 45 minutes). The gaseous products exit the reactor and pass through a condenser to remove any liquids or tars. Collect the non-condensable gas in a gas bag or online sampling port for analysis.

- Gas Analysis: Analyze the composition of the product gas using GC-TCD.

- Shutdown: Stop the glycerol feed. Continue the flow of Nâ‚‚ until the reactor cools to room temperature.

Protocol: Catalytic Dry Reforming of Glycerol (GDR)

This protocol outlines the catalyst synthesis and testing procedure for glycerol dry reforming using a Re-promoted Ni catalyst, based on the work of Arif et al. (2018) [40].

Materials and Equipment

- Catalyst Precursors: Nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O), Perrhenic acid (HReO₄), Calcium Oxide (CaO) support.

- Reactor System: A fixed-bed quartz reactor (e.g., 8 mm ID) in a tubular furnace.

- Gases: COâ‚‚, Nâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚ (for reduction), all high purity.

- Feed System: A syringe pump for glycerol-water mixture feed.

- Product Analysis: Online Micro-GC for gas composition analysis.

Detailed Procedure

A. Catalyst Preparation (Wet Impregnation)

- Support Preparation: Calcine the CaO support in air at 800°C for 6 hours.

- Impregnation: Prepare an aqueous solution containing the required amounts of HReO₄ and Ni(NO₃)₂·6H₂O to yield a final catalyst composition of 5% Re and 15% Ni by weight. Add the calcined CaO support to this solution.

- Mixing: Stir the mixture continuously for 3 hours at ambient temperature using a magnetic stirrer.