Strategic Pathways to Reduce Biomass Supply Chain Costs for a Sustainable Bioeconomy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to reduce costs and enhance the economic viability of biomass supply chains (BSCs).

Strategic Pathways to Reduce Biomass Supply Chain Costs for a Sustainable Bioeconomy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to reduce costs and enhance the economic viability of biomass supply chains (BSCs). It explores the fundamental structure and economic challenges of BSCs, presents advanced methodological approaches like computer simulation and digital solutions for cost optimization, and addresses key troubleshooting areas such as feedstock degradation and logistical bottlenecks. The content also examines the validation of strategies through global case studies and policy frameworks, with critical insights for researchers, scientists, and professionals engaged in developing sustainable biomass-derived products and energy.

Understanding Biomass Supply Chains: Structure, Cost Drivers, and Economic Challenges

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common operational challenges in a biomass supply chain? The biomass supply chain faces several recurrent operational hurdles that can impact cost and reliability. A primary issue is feedstock variability, where differences in moisture content, particle size, and chemical composition lead to feeding and handling problems, causing stoppages and reduced conversion efficiency [1] [2]. Furthermore, the low bulk density of many biomass feedstocks makes transportation inefficient and increases costs [3]. During storage, biomass is susceptible to degradation and self-heating, resulting in dry matter loss and potential spoilage [2]. Finally, handling cohesive and interlocking materials often leads to flow obstructions in hoppers and feeders, creating bottlenecks in the process [4] [3].

2. How does feedstock quality impact biorefinery operations? Inconsistent feedstock quality directly affects a biorefinery's ability to operate at its designed capacity. Variations can cause feeding system blockages, erratic flow, and equipment wear, which force unplanned downtime and increase maintenance costs [2] [4]. For conversion processes, inconsistent particle size or moisture content can lead to incomplete reactions, reduced yields of biofuels or chemicals, and challenges in meeting final product specifications [1] [4]. A shift toward a "quality-by-design" approach in the supply chain, which may include fractionation and targeted preprocessing, is seen as key to stabilizing feedstock quality and improving overall biorefinery performance [2].

3. What strategies can reduce costs across the biomass supply chain? Cost reduction requires an integrated, optimized approach. Key strategies include logistics optimization, such as the strategic siting of preprocessing depots to minimize transportation distances [1] [5]. Advanced preprocessing techniques, like torrefaction or pelletization, increase the energy density of biomass, thereby lowering transportation costs and improving handling properties [1] [5]. Implementing a multi-product biorefinery model that valorizes all biomass fractions (e.g., converting lignin into co-products alongside biofuels) significantly improves economic viability [6]. Finally, employing systematic modeling and multi-objective optimization during supply chain design helps balance economic, environmental, and operational goals [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Biomass Flowability and Bridging in Hoppers

Problem: Biomass feedstock fails to flow consistently from storage hoppers or silos, forming stable arches (bridges) or rat holes that obstruct discharge and disrupt continuous operation [4] [3].

Investigation & Diagnosis:

- Step 1: Visual Inspection. Safely observe the flow pattern during discharge. A "rat hole" is indicated if material empties only directly above the outlet, leaving a cylindrical channel, while a "bridge" is a stable arch of material over the outlet [4].

- Step 2: Material Property Analysis. Measure the key flow properties of your biomass feedstock, including:

- Cohesive Strength: The internal strength of the biomass material.

- Wall Friction Angle: The friction between the biomass and the hopper wall surface.

- Moisture Content: High moisture often increases cohesion [4].

- Step 3: Hopper Design Review. Compare the hopper's outlet size and wall slope (angle) against the flow properties measured in Step 2. The design is likely insufficient if the outlet is smaller than the critical "no-flow" dimension derived from cohesive strength tests [4].

Solutions:

- Short-Term Fixes:

- Long-Term & Design Solutions:

- Retrofit the Hopper: Modify the hopper to have a steeper wall slope and a larger outlet size based on the measured flow properties of the biomass [3].

- Use a Liner: Install a low-friction liner on the hopper walls to reduce wall friction and promote mass flow (where all material moves downward together) [4].

- Control Feedstock Properties: Implement preprocessing steps, such as drying or size reduction, to reduce the feedstock's cohesiveness and improve its inherent flowability [2] [4].

Table: Key Properties Affecting Biomass Flowability [4]

| Property | Description | Impact on Flow |

|---|---|---|

| Cohesive Strength | Internal shear strength of the biomass mass. | Higher cohesion promotes bridging and rat-holing. |

| Moisture Content | Amount of water present in the biomass. | Increased moisture generally increases cohesion. |

| Particle Size & Shape | Distribution and geometry of biomass particles. | Stringy, elongated particles can interlock; fines can increase cohesion. |

| Wall Friction | Friction between biomass and hopper wall material. | High friction encourages funnel flow and stagnant zones. |

| Bulk Density | Mass per unit volume of the bulk material. | Low density can correlate with poor flow and handling challenges. |

Guide 2: Mitigating Feedstock Quality Degradation During Storage

Problem: Biomass loses dry matter, self-heats, or experiences chemical changes during storage, leading to reduced mass yield, lower energy content, and potential conversion inhibitors [2] [5].

Investigation & Diagnosis:

- Step 1: Monitor Storage Conditions. Track temperature profiles within storage piles or bales using temperature probes. A rising temperature indicates active microbial respiration or chemical oxidation [2].

- Step 2: Pre- and Post-Storage Analysis. Collect representative samples of biomass upon entry to and exit from storage. Analyze key parameters, including:

- Dry Matter Mass: To quantify total mass loss.

- Moisture Content: To assess drying or rewetting.

- Sugar Content (for biochemical conversion): To measure the loss of fermentable sugars [2].

- Step 3: Identify Contamination. Check for visible mold growth or a musty odor, which signal microbial spoilage [2].

Solutions:

- Pre-Storage Preparation:

- Storage Management:

- Implement Covering: Use tarps or breathable membranes to protect biomass from precipitation while allowing some moisture release.

- Manage Stock Rotation: Adopt a first-in, first-out (FIFO) inventory system to minimize storage duration [5].

- Consider Advanced Storage Formats: Explore compacted, oxygen-limited storage systems designed to stabilize biomass and preserve quality [2].

Guide 3: Managing Feedstock Variability for Consistent Conversion

Problem: Incoming biomass feedstock has high variability in physical and chemical properties, causing fluctuations in conversion process efficiency, yield, and product quality [1] [2].

Investigation & Diagnosis:

- Step 1: Establish a Quality Dashboard. Implement a rapid characterization protocol for incoming feedstock loads. Key metrics should include particle size distribution, moisture content, and ash content [2].

- Step 2: Correlate with Performance. Use statistical process control to link variations in feedstock quality metrics with key performance indicators (KPIs) of the conversion process, such as reaction yield, throughput, or catalyst life [1].

- Step 3: Source Analysis. Track quality data back to specific suppliers, harvest dates, or geographic regions to identify the root causes of variability [1].

Solutions:

- Feedstock Blending: Mix different lots of feedstock in a controlled manner to create a more consistent and homogeneous blend for the conversion process [5].

- Advanced Preprocessing: Invest in preprocessing facilities that can actively control and adjust feedstock properties. A "quality-by-design" approach using fractionation can separate biomass into more uniform streams tailored for specific conversion pathways or products [2] [6].

- Supplier Contracts & Specifications: Develop and enforce clear feedstock quality specifications in supplier agreements, with incentives for consistent quality delivery [5].

Experimental Protocols for Supply Chain Research

Protocol 1: Quantifying Biomass Flow Properties Using a Ring Shear Tester

Objective: To determine the cohesive strength and wall friction properties of a biomass feedstock for the purpose of designing reliable hoppers and feeders [4].

Materials:

- Ring Shear Tester (e.g., Jenike shear cell)

- Biomass sample (representative of feedstock, preconditioned to target moisture content)

- Hopper wall material sample (e.g., stainless steel, carbon steel)

- Laboratory balance

- Drying oven

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the biomass sample according to your standard preprocessing protocol. Determine the initial moisture content using a drying oven. The test can be repeated at different moisture levels to understand its impact.

- Cell Filling: Fill the shear cell with the biomass sample in a standardized, consistent manner to ensure a uniform initial bulk density.

- Consolidation: Apply a series of predetermined normal loads (stresses) to the sample to simulate the consolidation pressures experienced in a full-scale hopper.

- Shearing: For each consolidation stress, shear the sample to failure to measure the shear stress required. This data is used to establish the Yield Locus, which defines the material's flow function.

- Wall Friction Test: Repeat the shearing procedure with the wall material sample placed in the base of the shear cell. This determines the wall friction angle.

- Data Analysis: Using the yield locus data, calculate the unconfined yield strength (fc) and major principal stress (σ1) at various consolidation levels. The flow function is a plot of fc vs. σ1. A lower f_c indicates a more free-flowing material.

Application: The resulting flow function and wall friction data are used in established hopper design calculations (e.g., Jenike method) to determine the minimum outlet size and hopper slope angles required to prevent arching and ensure reliable flow [4].

Protocol 2: Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) of a Novel Preprocessing Pathway

Objective: To evaluate the economic viability and identify major cost drivers of integrating a new preprocessing technology (e.g., torrefaction, CELF pretreatment) into a biomass supply chain [6] [7].

Materials:

- Process modeling software (e.g., Aspen Plus, SuperPro Designer)

- Cost data for equipment, feedstock, utilities, and labor

- Operational data (yields, energy consumption, throughput)

Methodology:

- Process Simulation: Develop a detailed model of the integrated supply chain and conversion process, including the new preprocessing unit. The model should be based on mass and energy balances.

- Capital Cost Estimation (CAPEX): Estimate the total installed cost of all new equipment, including the preprocessing unit, storage, and handling systems.

- Operating Cost Estimation (OPEX): Estimate annual costs for feedstock, utilities, labor, maintenance, and overhead.

- Revenue Estimation: Project revenue from the sale of all main products and co-products (e.g., biofuels, chemicals, power). For novel co-products, market research may be required.

- Financial Modeling: Calculate key economic indicators such as Minimum Fuel Selling Price (MFSP), Net Present Value (NPV), and Internal Rate of Return (IRR) [6] [7].

- Sensitivity Analysis: Identify which parameters (e.g., feedstock cost, conversion yield, product price) have the greatest impact on the project's economics by varying them within a plausible range.

Application: This protocol allows for the quantitative comparison of different supply chain configurations. For instance, it can demonstrate whether a more expensive preprocessing step that improves feedstock quality and conversion yield ultimately leads to a lower overall biofuel cost, as seen in CELF biorefinery models [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Analytical Methods for Biomass Supply Chain Research

| Item / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Ring Shear Tester | Measures fundamental powder flow properties (cohesive strength, internal friction) critical for designing storage and handling equipment to prevent flow stoppages [4]. |

| Torrefaction Reactor | A laboratory-scale reactor used to study the effects of mild pyrolysis on biomass, improving its grindability, hydrophobicity, and energy density for more efficient transport and storage [5]. |

| Mechanical Preprocessing Unit (e.g., Knife Mill, Hammer Mill) | Used to standardize and study the effect of particle size and shape distribution on downstream handling, flowability, and conversion efficiency [2] [4]. |

| Process Modeling Software (e.g., Aspen Plus) | Enables the simulation of integrated biomass supply chains and conversion processes for techno-economic analysis (TEA) and life cycle assessment (LCA) before pilot-scale implementation [1] [7]. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectrometer | Provides rapid, non-destructive analysis of biomass properties (e.g., moisture, lignin, cellulose content) for real-time quality control and feedstock blending optimization [2]. |

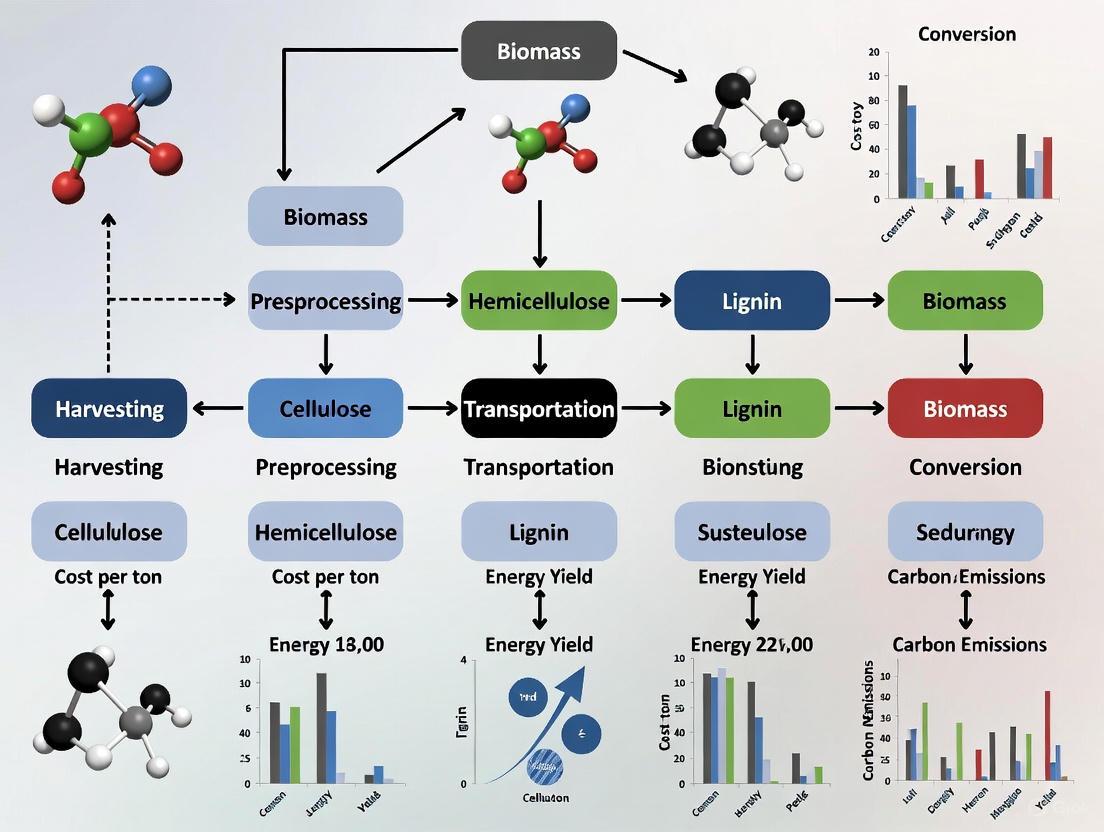

The core components of a biomass supply chain form an integrated system to move organic material from its origin to a biorefinery. The diagram below illustrates the key stages and the critical material flow and information feedback required for optimization. A central tenet of modern supply chain strategy is the move from simple, uniform-format feedstocks to a "quality-by-design" system that uses fractionation and multiple pathways to maximize value and ensure consistency for the biorefinery [1] [2].

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the most significant capital costs when establishing a biomass energy facility? The initial capital investment for a biomass power plant is substantial. For a standard 50-megawatt (MW) plant, total startup costs typically range from $236.5 million to $364 million [8]. The largest cost components are plant construction and engineering ($125-$175 million) and biomass conversion technology and equipment ($100-$140 million) [8]. These figures do not include operational costs or working capital, though initial project financing must account for them. Leveraging government subsidies, such as the Investment Tax Credit (ITC), can offset up to 30% of these initial capital expenditures [8].

FAQ 2: How do feedstock costs impact overall project viability? Feedstock expenses represent 40% to 60% of the total operating budget for a typical biomass plant, translating to annual fuel expenditures of $15 million to $25 million for a 50 MW facility [8]. This volatility directly affects profitability; a 10% increase in feedstock cost can reduce a project's internal rate of return (IRR) by 15-25 percentage points [8]. Securing stable, low-cost feedstock supply chains is therefore critical for financial viability. Creative sourcing strategies, such as utilizing waste algae from wastewater treatment plants, can provide feedstock for free or even at negative cost (e.g., being paid $341 per ton to haul it away) [9].

FAQ 3: What logistical factors most significantly influence biomass transportation costs? Transportation constitutes a substantial portion of total delivered feedstock cost, particularly for low-cost or residue-based biomass [10]. Machine learning analyses identify vehicle type (31% impact), transport distance (25% impact), and load factor (12% impact) as the most significant predictors of final transportation cost [10]. Unlike conventional wisdom, the impact of distance alone was found to be minimal compared to these other factors. Optimization of these parameters through advanced algorithms can significantly reduce overall biofuel production expenses [10].

FAQ 4: What strategies can mitigate seasonal variations in biomass supply? Seasonality directly affects biomass supply chain cost and efficacy [11]. Effective management requires:

- Strategic storage planning to balance supply and demand fluctuations

- Supply chain coordination across collection, transportation, storage, and processing operations

- Advanced optimization techniques including linear programming, genetic algorithms, and tabu search to manage seasonal inventory [11] These approaches help maintain consistent biomass quality and availability despite seasonal variations in feedstock production.

FAQ 5: How can facility location decisions reduce production costs and emissions? Strategic facility siting offers significant cost and emission reduction opportunities. Building biocrude facilities next to existing refineries instead of closer to biomass sources can lower emissions by up to 150% through shared infrastructure [9]. Co-location enables:

- Utilization of byproducts (heat, steam) locally, replacing fossil fuels

- Collection and use of low-emission hydrogen released during biomass conversion

- Reduced transportation needs for intermediate products [9] These design decisions yield substantial energy savings and corresponding emission reductions.

Table 1: Biomass Facility Capital Investment Breakdown (50 MW Plant)

| Cost Component | Minimum Estimate | Maximum Estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Construction & Engineering | $125 million | $175 million |

| Biomass Conversion Technology & Equipment | $100 million | $140 million |

| Land Securement & Site Preparation | $1 million | $5 million |

| Grid Interconnection & Transmission Upgrades | $2 million | $15 million |

| Long-term Fuel Supply Contracts | $2 million | $10 million |

| Permitting, Licensing & Legal Fees | $1.5 million | $4 million |

| Initial Working Capital | $5 million | $15 million |

| Total Startup Costs | $236.5 million | $364 million |

Table 2: Financial Performance Metrics for Biomass Energy Production

| Metric | Typical Range | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|

| EBITDA Margin | 20% - 40% | Feedstock costs, electricity pricing, operational efficiency |

| Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) | $0.08 - $0.12 per kWh | Technology choice, feedstock cost, facility scale |

| Feedstock Cost Share of Operating Budget | 40% - 60% | Feedstock type, sourcing strategy, transportation distance |

| Impact of 10% Feedstock Cost Increase on IRR | 15-25 percentage point reduction | Project leverage, PPA terms, operational flexibility |

Table 3: Feedstock Sourcing Cost Comparisons

| Feedstock Source | Cost per Ton | Notes & Context |

|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Baseline | Conventional biomass reference point |

| Algal Biomass (traditional) | Up to 9x lignocellulosic | Requires dedicated algae farms |

| Wastewater Treatment Algae | -$341 (negative cost) | Facilities may pay for removal |

| Harmful Algae Blooms | $21 (with credits) | With government environmental credits |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) for Biofuel Projects

Purpose: To evaluate the fiscal viability of biomass energy projects by integrating process engineering with economic analysis.

Methodology:

- Process Modeling: Develop detailed process flow diagrams capturing all conversion steps from feedstock to final product

- Capital Cost Estimation: Calculate equipment costs using factored estimation methods (±30% accuracy) for preliminary assessment

- Operating Cost Estimation: Quantify fixed and variable costs, with particular emphasis on feedstock logistics

- Financial Modeling: Compute key performance indicators including Internal Rate of Return (IRR), Net Present Value (NPV), and Minimum Selling Price

Key Parameters:

- Plant capacity and availability (typically ≥90% for bioenergy)

- Feedstock composition, cost, and seasonal variability

- Conversion process yields and efficiencies

- Co-product credits and values

- Financing structure (debt/equity ratio, interest rates, loan term)

Application: TEA helps identify cost bottlenecks, particularly in the supply chain, and enables comparison of technology alternatives [9].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Based Transportation Cost Optimization

Purpose: To accurately predict and optimize biomass transportation costs using advanced algorithms.

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Compile historical data on biomass transportation across fifteen independent variables including vehicle type, distance, and load factor

- Model Selection: Compare multiple linear regression, random forests, and artificial neural networks for predictive accuracy

- Model Training: Implement k-fold cross-validation to prevent overfitting

- Feature Importance Analysis: Quantify the relative contribution of each variable to total transportation cost

Expected Outcomes:

- Random forest models typically achieve R-squared values of 97.4% with root mean square error of 165

- Identification of vehicle type (31% impact), distance (25% impact), and load factor (12% impact) as primary cost drivers [10]

Protocol 3: Supply Chain Resilience Testing

Purpose: To evaluate biomass supply chain robustness under disruptive scenarios such as feedstock shortages, price volatility, and transportation disruptions.

Methodology:

- Scenario Development: Create plausible disruption scenarios including seasonal availability fluctuations, supplier failures, and demand spikes

- Model Implementation: Apply linear programming, genetic algorithms, or tabu search optimization techniques

- Resilience Metric Calculation: Quantify performance using cost-to-serve, service level, and inventory turnover metrics

- Mitigation Strategy Evaluation: Test interventions including diversified sourcing, strategic storage, and flexible transportation modes

Key Considerations:

- Account for biomass quality degradation during storage

- Model multi-modal transportation options

- Evaluate impact of regional biomass availability constraints [11]

Visualization: Biomass Supply Chain Cost Optimization Framework

Biomass Supply Chain Cost Framework

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Analytical Tools for Biomass Supply Chain Research

| Tool/Model | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| POLYSYS Modeling Framework | Generates biomass supply curves with price as a function of availability and demand over time | National-level biomass assessment excluding soy and corn; projects supply to 2030 [12] |

| Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) | Integrates process engineering with economic analysis to evaluate project viability | Assessing fiscal returns of biofuel ventures; identifying cost bottlenecks [9] |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | Quantifies environmental impacts across the entire biomass value chain | Evaluating net carbon emissions of biofuel production and use [9] |

| Random Forest Algorithm | Machine learning approach for predicting transportation costs with high accuracy | Transportation logistics optimization; achieves R-squared values of 97.4% [10] |

| Stochastic Energy Deployment System (SEDS) | Models biomass price as a function of demand across multiple sectors (electricity, biofuels, hydrogen) | Estimating maximum biomass supply at various price points; sectoral allocation [12] |

| Genetic Algorithms (GA) | Optimization technique for complex logistical problems with multiple constraints | Solving supply chain network design; route optimization [11] |

The Critical Challenge of Economic Viability in Bioenergy Projects

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the primary cost drivers in a biomass supply chain? The primary costs are associated with feedstock procurement, transportation, storage, and pre-processing. Transportation is particularly dynamic and costly due to factors like fuel prices, distance, and road conditions. Storage losses and feedstock degradation also significantly impact final costs [13] [5].

How can I reduce the risk of costly errors when modifying my supply chain? Computer simulation is a low-risk method to test different supply chain configurations. It allows for modeling an entire supply chain—from raw material supply to distribution—to see the impact of changes on cost and operational efficiency before implementing them in the real world [14].

My project uses agricultural residue. How can I ensure consistent feedstock quality? Inconsistent quality from agricultural residues can be tackled through pre-processing steps like torrefaction, which improves energy density and storage properties. Implementing feedstock blending strategies at the biorefinery can also help manage variability [5] [15].

Are there tools to help select the most cost-effective biomass suppliers? Yes, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN)-based models are now being developed to optimize supplier selection. These tools integrate economic, technical, and geographic data to recommend suppliers that meet cost and quality requirements, even with incomplete market data [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Feedstock Logistics Costs

Issue: The cost of transporting biomass from the field or forest to the conversion facility is making the project economically unviable.

Diagnosis & Solutions:

- Diagnosis 1: Inefficient transport routes and logistics.

- Solution: Implement an AI-based Biomass Delivery Management (BDM) model.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Data Collection: Gather historical data on biomass type, supplier locations, unit prices, transport distances, and fuel consumption [13].

- Model Development: Develop a modular Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model. This model should learn the complex, non-linear relationships between the input variables (e.g., distance, feedstock type) and output costs [13].

- Model Validation: Evaluate the model's predictive accuracy using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Squared Error (MSE). A validated model from a case study achieved an MAE of 0.16 and an R² value of 0.99 [13].

- Deployment: Use the model to simulate different procurement strategies, optimize transport routes in real-time, and inform fuel blending strategies to reduce overall costs [13].

- Diagnosis 2: High costs due to low energy density of raw biomass.

- Solution: Integrate pre-processing technologies to upgrade biomass.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Technology Selection: Evaluate technologies like pelleting, briquetting, or torrefaction. Torrefaction, a mild pyrolysis process, is particularly effective as it produces a coal-like material with higher energy density and better water resistance [16] [15].

- Supply Chain Integration: Establish "conceptual depots" where raw biomass can be converted into a stable, high-energy-density bioenergy carrier [5].

- Logistics Optimization: Leverage existing infrastructure (e.g., coal handling systems) for transporting the upgraded biomass, significantly reducing transport costs per unit of energy [5].

Problem: Low Economic Resilience to Market Fluctuations

Issue: Project economics are sensitive to changes in feedstock prices, policy adjustments, or energy market prices.

Diagnosis & Solutions:

- Diagnosis: Over-reliance on a single feedstock or operational configuration.

- Solution: Use discrete-event simulation to model and enhance supply chain flexibility.

- Experimental Protocol:

- System Mapping: Create a computational model of your entire supply chain, including procurement, transportation, storage, production, and distribution. Incorporate key variables like time, cost, and resource constraints [14].

- Scenario Testing: Run multiple "what-if" scenarios in the simulation environment. Examples include:

- Switching the fuel used in drying processes (e.g., from sawdust to bark, which achieved a 1.5% cost reduction in a case study) [14].

- Testing different feedstock blends (e.g., blending 10% bark for lower-quality pellets, which yielded 4.75% raw material savings) [14].

- Modeling the impact of changes in policy mandates or feedstock availability.

- Analysis and Implementation: Identify the scenarios that most improve cost-efficiency and operational resilience. Implement these changes in the actual supply chain, monitoring key performance indicators to validate the model's predictions [14].

Data Presentation

| Metric | 2023/2024 Status | 2034 Projection & Key Trends | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Biofuel Production | 175.2 billion litres (2023) | Projected to grow at 0.9% p.a.; significant growth in India, Indonesia, and Brazil. | [17] [18] |

| Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) Production | 1.8 billion litres (2024) | Rapid growth sector (200% increase from 2023); driven by new mandates in India, South Korea, and Indonesia. | [17] |

| Global Biopower Capacity | 150.8 GW (2024) | Steady growth, with a record increase of 4.6 GW in 2024. Key growth in China and France. | [17] |

| Biomass Power Generation Market Value | US$90.8 Billion (2024) | Projected to reach US$116.6 Billion by 2030, a CAGR of 4.3%. | [16] |

| EU Solid Biomass Electricity | 78.4 TWh (2023) | Down 11.3%; a continuing trend of decline in several EU nations. | [17] |

| Strategy | Experimental Methodology | Key Quantitative Outcome | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| AI/ANN Supply Chain Optimization | Develop a modular ANN model to optimize supplier selection, transport routes, and blending. | High predictive accuracy (MAE = 0.16, R² = 0.99); potential for 20-30% reduction in transport costs. | [13] |

| Computer Simulation & Scenario Testing | Discrete-event simulation of the entire supply chain to test operational changes virtually. | 1.5% cost reduction by changing drying fuel; 4.75% raw material savings from feedstock blending. | [14] |

| Feedstock Pre-processing (Torrefaction) | Thermal treatment to improve biomass properties. Enables use of existing coal infrastructure. | Increases energy density, reduces degradation, and lowers transport costs per unit of energy. | [16] [5] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Bioenergy Research |

|---|---|

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) Models | A computational tool used to model complex, non-linear biomass supply chains, predict costs, and optimize logistics based on historical data [13]. |

| Discrete-Event Simulation Software | Software that creates a virtual model of a biomass supply chain to test different operational scenarios and quantify their impact on cost and efficiency without real-world risk [14]. |

| Torrefaction Reactor | A device for the mild pyrolysis of biomass, which produces a dry, hydrophobic, and energy-dense solid biofuel that is more suitable for storage and long-distance transport [16] [15]. |

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | A system that integrates spatial data (e.g., supplier locations, road networks) to analyze and optimize transport routes and biomass procurement strategies [13]. |

Experimental Workflow and Strategic Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected strategies for diagnosing and improving the economic viability of bioenergy projects, from initial data collection to implementation and monitoring.

Global Market Dynamics and Growth Projections for Biomass Industrial Fuels

The global biomass industrial fuel market is a cornerstone of the renewable energy sector, experiencing significant growth driven by the worldwide shift towards sustainable energy. Biomass industrial fuel refers to renewable energy sources derived from organic materials such as wood, agricultural residues, palm kernel shells, and rice husks [19]. These combustible solid fuels serve as sustainable alternatives to fossil fuels like coal and are primarily used in industrial boilers, kilns, and steam generators [19]. The adoption of biomass fuels supports carbon neutrality goals because they release only the CO₂ absorbed during plant growth, creating a closed carbon cycle, and further promote circular economy principles by converting waste into valuable energy resources [19].

Table 1: Global Biomass Market Size and Growth Projections

| Market Segment | 2024/2025 Base Value | 2031/2035 Projected Value | CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) | Source / Scope |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Industrial Fuel Market | USD 1,856 million (2025) [19] | USD 3,316 million (2031) [19] | 10.3% (2025-2031) [19] | Intel Market Research |

| Overall Biomass Fuel Market | USD 51.65 Billion (2025) [20] | USD 78.18 Billion (2032) [19] | 6.1% (2025-2032) [20] | Coherent Market Insights |

| Overall Biomass Market | USD 79.26 Billion (2025) [21] | USD 157.38 Billion (2035) [21] | 7.1% (2026-2035) [21] | Research Nester |

| Biomass Energy Market | USD 99 Billion (2024) [22] | USD 160 Billion (2035) [22] | 4.46% (2025-2035) [22] | Spherical Insights |

The market expansion is propelled by a confluence of factors, including tightening environmental regulations, corporate sustainability initiatives, and technological advancements in fuel processing [19]. Supportive government policies, such as subsidies, tax incentives, and renewable portfolio standards, are primary catalysts for growth, compelling a transition away from fossil fuels [23]. Furthermore, the increasing demand for sustainable waste management solutions positions biomass as an attractive option for converting organic waste into valuable energy, thereby addressing waste disposal challenges and contributing to a circular bioeconomy [21] [22].

Regional Market Dynamics

The global biomass market exhibits distinct regional characteristics shaped by local feedstock availability, policy landscapes, and energy demands.

Table 2: Regional Market Share and Growth Drivers

| Region | Projected Market Share (2025) | Key Growth Drivers | Leading Countries/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia-Pacific | 44.5% [20] | Escalating energy demand, abundant agricultural residues, supportive government policies for waste-to-energy initiatives. [20] [23] | China (leads in APAC), India, Japan. Rapid industrialization and urbanization. [20] |

| Europe | 27.69% [23] | Stringent carbon emission regulations, EU Green Deal, ambitious renewable energy targets (e.g., RED II). [20] [23] | Germany, United Kingdom, France. Leader in adoption due to stringent emission norms. [19] [23] |

| North America | 22.8% [20] | Strong governmental support (e.g., U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard), abundant natural resources, well-established energy grid. [20] | United States (market leader), Canada. The fastest-growing region. [20] |

| South America | 8.07% [23] | Vast and productive agricultural sector providing ample feedstock (e.g., sugarcane bagasse). [23] | Brazil (dominates the region), Argentina. [23] |

| Africa | 6.37% [23] | Urgent need for decentralized and off-grid energy solutions to improve energy access. [23] | Nigeria, South Africa. Characterized by traditional biomass use and emerging modern projects. [23] |

Key Application Segments and Feedstock

The application of biomass fuels spans multiple sectors, with power generation, residential heating, and industrial uses being the most prominent. The primary feedstock includes wood and agricultural residues, which dominate due to their widespread availability and cost-effectiveness [20].

- Power Generation: This segment is projected to hold a 37.8% share of the biomass fuel market in 2025 [20]. The growth is driven by the global demand for clean and renewable electricity. Biomass power plants offer a key advantage by providing dispatchable electricity, which can operate continuously unlike intermittent sources like solar and wind, thereby ensuring grid stability [20].

- Residential Heating: The residential segment is expected to account for a 39.8% share in 2025 [20]. This is driven by the escalating demand for sustainable and economical heating options, particularly in rural and peri-urban areas. Homeowners are increasingly turning to biomass boilers and stoves as cost-effective and eco-friendly alternatives to volatile traditional heating fuels [20] [21].

- Wood and Agricultural Residues: This feedstock segment is expected to account for 42.7% of the market share in 2025 [20]. These residues represent a vast portion of biomass resources, stemming from forestry operations and agricultural harvests. Their abundance ensures a reliable and continuous feedstock supply, while their utilization provides an effective means of waste management [20].

Technical Support: Troubleshooting Supply Chain Challenges

Efficient supply chain management is critical for reducing costs and ensuring the reliability of biomass industrial fuels. Below are common challenges and research-supported mitigation strategies presented in a troubleshooting format.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most significant challenges in the biomass supply chain? The primary challenges involve inherent uncertainties and variability. These include fluctuations in the quantity and quality of raw materials at supply nodes, seasonal availability of feedstock, geographical dispersion of resources, and susceptibility to disruptive events like wildfires [24]. Additionally, logistics related to collecting, transporting, and storing bulky biomass can be complex and costly, representing a significant portion of the total supply chain cost [24] [23].

FAQ 2: How can the cost of biomass feedstock production be reduced? Research indicates that optimization of machinery fleet management and advanced harvesting techniques can lead to substantial cost reductions. For instance, studies on corn stover production have demonstrated a 40% reduction in production costs compared to initial benchmarks through improved logistics and machinery efficiency [25]. Furthermore, optimizing transportation routes and scheduling can lower operational costs associated with vehicle idle time [24].

FAQ 3: How can biomass quality and year-round supply be ensured for a biorefinery? Developing best management practices for biomass storage is crucial to maximize long-term quality and ensure year-round operation of conversion facilities [25]. Implementing a decision support system (DSS) that combines simulation and optimization can help plan and replan operations under disruptive scenarios, ensuring a consistent feedstock supply to the plant gate [24] [25].

Experimental Protocols for Supply Chain Optimization

Protocol 1: Simulation-Optimization Framework for Resilient Supply Chain Design

This methodology supports decision-making for efficient operations management and enhances the design process of a biomass supply chain under uncertainty [24].

- System Definition and Data Collection: Map the entire biomass supply chain architecture, including key stages: feedstock production, harvesting, transportation, storage at intermediate terminals, processing (e.g., chipping), and final delivery to the energy plant [24]. Collect data on biomass availability, costs, transportation modes, and facility capacities.

- Develop an Optimization Model: Formulate a resource allocation optimization model (mixed-integer linear programming is common). This model should generate initial plans to minimize total cost or maximize efficiency by deciding on optimal transportation routes, feedstock sourcing, and storage terminal utilization [24].

- Build a Simulation Model: Create a discrete-event simulation (DES) model that replicates the operations and dynamic flows of the physical supply chain. This model incorporates the variability and uncertainties identified in Step 1, such as fluctuations in raw material quantity and disruptive events like wildfires [24].

- Scenario Generation and Analysis: Generate different disruptive scenarios (e.g., 10%, 50%, 80% loss of biomass at a key supply node) to test the resilience of the initial optimization plan [24]. Run these scenarios through the simulation model.

- Re-planning and Evaluation: Use the optimization model as a re-planning tool to devise new operational plans that mitigate the impacts of the disruption simulated in Step 4. Evaluate the performance using Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) such as total cost, demand fulfillment rate, and resource utilization [24].

- Validation and Implementation: Validate the simulation-optimization framework against historical data if available. The final output is a Decision Support System (DSS) that allows planners to anticipate impacts and make more informed, resilient decisions [24].

Protocol 2: Best Management Practices for Biomass Storage and Quality Preservation

This protocol aims to maintain biomass quality between harvest and conversion, which is critical for energy yield and operational continuity.

- Feedstock Characterization: Analyze the initial moisture content, particle size, and chemical composition of the biomass feedstock (e.g., corn stover, wood chips) [25].

- Storage Method Selection: Establish different storage testing facilities, including open-air piles, covered storage, and enclosed silos, to compare efficacy [25].

- Monitoring: Instrument the storage facilities to monitor internal temperature, moisture levels, and relative humidity over a defined period (e.g., 6-12 months) [25].

- Quality Assessment: At regular intervals, take core samples from the storage piles. Analyze the samples for key quality metrics, including dry matter loss, changes in moisture content, and ash content. A key research goal is to reduce ash content, as a 35% reduction has been achieved through machinery development [25].

- Data Analysis and Protocol Development: Correlate the storage conditions with the quality metrics to identify best practices that maximize quality preservation. Document these as best management practices for specific feedstock types [25].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Supply Chain Research

Table 3: Key Analytical Tools and Solutions for Biomass Supply Chain Research

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Discrete-Event Simulation (DES) Software | Models the operation of a real-world system as a discrete sequence of events over time, allowing "what-if" analysis of supply chain dynamics. [24] | Simulating the impact of a truck breakdown or a wildfire on the daily feedstock delivery to a biorefinery. [24] |

| Resource Allocation Optimization Model | A mathematical model (e.g., Mixed-Integer Linear Programming) that generates plans to minimize cost or maximize efficiency by allocating limited resources. [24] | Determining the optimal number of trucks, chipping schedules, and which feedstock sites to use to meet weekly demand. [24] |

| High-Capacity Biomass Analysis Lab | Provides instrumentation for analyzing the chemical and physical properties of biomass feedstocks. [25] | Measuring moisture content, calorific value, and ash composition of stored wood pellets to ensure quality standards. [25] |

| Industrial-Quality Storage-Testing Facilities | Controlled environments to test and validate different biomass storage techniques. [25] | Comparing dry matter loss in corn stover stored under tarps versus in an open-air pile over a 9-month period. [25] |

| Data Analytics and GIS Tools | Platforms for analyzing large datasets and visualizing the geographical dispersion of biomass resources. [25] [26] | Mapping the spatial distribution of agricultural residues to determine the optimal location for a new pellet plant. [26] |

Biomass Supply Chain Decision Support Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated simulation-optimization framework for managing the biomass supply chain and mitigating disruptions, as described in the experimental protocols.

The Impact of Seasonal Variability and Feedstock Geodistribution on Costs

Troubleshooting Guide: Seasonal and Geographical Feedstock Challenges

This guide addresses common experimental and operational challenges related to seasonal variability and feedstock geodistribution in biomass supply chains for biofuel and biopower production.

FAQ 1: How does seasonal weather variability impact feedstock quality and subsequent conversion efficiency in our laboratory experiments?

- Problem: Inconsistent experimental results in biochemical conversion pathways between batches.

- Diagnosis: Seasonal weather conditions during biomass growth (e.g., drought, excessive rainfall) can alter the structural composition of feedstocks, such as the lignin-to-cellulose ratio, directly impacting enzymatic hydrolysis efficiency and fermentation yields in biochemical processes like fermentation and hydrolysis [27] [28].

- Solution:

- Pre-Screening: Implement a rigorous feedstock pre-screening protocol using the Vegetation Health Index (VHI) or similar remote sensing data to identify and exclude batches from growing seasons with anomalous weather [27].

- Compositional Analysis: Perform standard compositional analysis (e.g., using NREL laboratory analytical procedures) on every received batch to establish a baseline.

- Blending: Strategically blend feedstock batches from different seasons or regions to achieve a more consistent compositional profile for your experiments [5].

FAQ 2: Our supply chain cost models are highly sensitive to feedstock price volatility. What is the primary driver of this, and how can we account for it?

- Problem: Unpredictable spikes in model input costs, leading to unreliable techno-economic analysis (TEA).

- Diagnosis: Price volatility is intrinsically linked to growing-season weather across major global production regions. Poor weather conditions, indicated by low VHI, can create anticipations of reduced future supply, affecting not only the primary crop market but also the prices of substitute feedstocks [27]. Furthermore, policy changes, such as carbon intensity standards, can suddenly alter demand for certain feedstocks, exacerbating price swings [29].

- Solution: Integrate long-term weather and climate data (e.g., VHI historical data) and policy monitoring into your TEA models. Employ econometric frameworks like GARCH (Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity) to model and forecast this volatility, providing a more robust range of cost scenarios [27].

FAQ 3: Why does the geographical source of our feedstock significantly impact our sustainability metrics and compliance with regulations like the EU's Deforestation-free Regulation?

- Problem: The same feedstock type from different regions yields vastly different carbon intensity (CI) scores and sustainability certifications.

- Diagnosis: The geodistribution of feedstock production is directly tied to its environmental footprint. Land-use changes, agricultural practices, and transportation logistics vary significantly by region. For instance, EU imports of commodities like soy and palm oil are linked to deforestation, drastically increasing their CI score [30]. Regional ecosystem health also affects sustainability; over half of the EU's agricultural ecosystems are not in good condition, impacting long-term viability [30].

- Solution:

- Provenance Tracking: Implement a robust system for tracking feedstock provenance.

- Certification Schemes: Prioritize feedstocks certified under recognized sustainability schemes that verify sustainable land management and low CI [5] [30].

- Regional Selection: Favor feedstocks from regions with policies that maintain ecosystem health, such as those promoting regenerative agricultural practices or sustainable forest management [30].

FAQ 4: We are experiencing unpredictable feedstock degradation and quality inconsistencies during storage, affecting experimental reproducibility. How can this be mitigated?

- Problem: Biomass degrades between harvest and use, leading to losses and inconsistent quality.

- Diagnosis: This is a common issue in supply chains where a time lag exists between harvest and processing. Factors like moisture content, microbial activity, and storage conditions cause degradation [5].

- Solution:

- Pre-processing: Utilize in-field pre-processing steps like torrefaction, which creates a more stable, water-resistant bioenergy carrier that is less prone to degradation and easier to store and transport [5] [16].

- Advanced Storage: Investigate alternate storage designs (e.g., controlled atmosphere) to minimize biological activity.

- Stabilization: For lipid-rich feedstocks like UCO and animal fats, assess stabilization methods to prevent oxidation and acidification during storage.

Quantitative Data on Biomass and Bio-Feedstock Markets

Table 1: Global Market Overview for Biomass Power and Bio-Feedstocks

| Market Segment | Market Size (2024) | Projected Market Size (2030/2035) | Projected CAGR | Key Feedstocks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Power Generation [16] | US$90.8 Billion | US$116.6 Billion (2030) | 4.3% | Forest waste, agricultural residue, municipal solid waste |

| Biomass Power Generation Fuel [31] | USD 1.01 Billion | USD 2.04 Billion (2031) | 10.7% | Wood chips, agricultural residues, palm kernel shells |

| Bio-Feedstock (General) [28] | USD 115.0 Billion | USD 224.9 Billion (2035) | 6.3% | Agricultural residues, waste oils, energy crops |

Table 2: Impact of Policy and Region on Feedstock Selection and Cost

| Factor | Impact on Feedstock Market | Example / Effect on Cost |

|---|---|---|

| US Clean Fuel Production Credit (CFPC) [29] | Shifts demand towards low-CI feedstocks. Feedstocks with CI >50 kg CO2/MMBtu (e.g., soybean oil) do not qualify. | Increases competition and cost for eligible waste oils (UCO, tallow). |

| EU Deforestation-free Regulation [30] | Restricts imports of commodities linked to deforestation (e.g., soy, palm oil). | Increases due diligence costs and may limit supply sources, potentially increasing prices for compliant feedstocks. |

| Regional Ecosystem Health [30] | Poor ecosystem conditions (23% of EU agricultural land is in poor condition) threaten long-term biomass viability. | Necessitates investment in regenerative practices, which may increase short-term costs but ensure long-term supply. |

| Tariffs and Trade Policy [29] | Can redirect global flows of feedstocks (e.g., potential US tariffs on Chinese UCO). | Creates regional price disparities and supply chain reconfiguration costs. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Cost Reduction Research

Protocol 1: Assessing the Impact of Seasonal Weather on Feedstock Quality and Conversion Yield

Objective: To quantitatively link seasonal growing conditions to feedstock compositional properties and biochemical conversion efficiency.

Methodology:

- Feedstock Sourcing & Weather Data Correlation: Source multiple batches of a single feedstock type (e.g., corn stover) from the same geographical region but from harvests following different growing seasons (e.g., drought year vs. typical year). Obtain historical weather data and Vegetation Health Index (VHI) data for the growing season for each batch [27].

- Compositional Analysis: For each batch, perform a standard compositional analysis to determine the percentages of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and ash [28].

- Biochemical Conversion: Subject each batch to standardized laboratory-scale biochemical conversion, including:

- Pre-treatment: Apply a consistent dilute-acid pre-treatment protocol.

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis: Use a standard enzyme cocktail and measure sugar release over time.

- Fermentation: Ferment the hydrolysate using a standard strain of S. cerevisiae and measure ethanol yield (or other relevant product) [28].

- Data Analysis: Correlate the VHI data and specific weather variables with compositional data and final product yield using statistical regression analysis. This will quantify the impact of seasonal variability on process efficiency.

Protocol 2: Modeling the Effect of Geodistribution on Supply Chain Costs and Carbon Intensity

Objective: To develop a geospatial model that optimizes feedstock sourcing based on total cost and CI.

Methodology:

- Define System Boundaries: Define the scope of the supply chain from the field to the biorefinery "throat" [5].

- GIS Data Collection: Collect geospatial data for potential feedstock sources, including:

- Yield: Average annual feedstock yield.

- Logistics Cost: Cost of collection, pre-processing (e.g., torrefaction), and transportation to a central hub or biorefinery. Note that transport costs can be "very significant" for remote resources [5].

- Sustainability Metrics: CI score associated with production in that region, leveraging tools for supply chain GHG emission calculations [5]. Include data on ecosystem status (e.g., from JRC reports) [30].

- Policy Factors: Note regional policies (e.g., deforestation-free status, carbon farming schemes) [30].

- Model Formulation: Build a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model to minimize total cost or CI. The model should include constraints for biorefinery demand, feedstock availability, and sustainability criteria.

- Scenario Analysis: Run the model under different scenarios (e.g., with/without a CI constraint, changes in transportation fuel costs) to identify robust sourcing strategies and key cost drivers.

Visualized Workflows and Relationships

Feedstock Supply Chain Cost Optimization

Weather Impact on Biofuel Markets

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for Biomass Supply Chain Research

| Item / Tool | Function / Application | Relevance to Thesis Context |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetation Health Index (VHI) | A remote sensing indicator used to assess crop health and anticipate future supply shocks based on growing-season weather [27]. | A critical data input for modeling the impact of seasonal variability on feedstock availability and price volatility. |

| GARCH-MIDAS-DCC Framework | An advanced econometric modeling framework. Isolates the impact of slow-moving variables (e.g., annual VHI) on daily price volatilities and correlations between commodities [27]. | Essential for developing sophisticated, predictive cost models that incorporate long-term climate and supply trends. |

| Torrefaction Reactor | A pre-processing unit that thermally converts biomass into a coal-like, water-resistant material with higher energy density and improved stability [5] [16]. | Key experimental apparatus for studying solutions to feedstock degradation during storage and for reducing transport costs. |

| Supply Chain GHG Emission Calculator | A tool (often software-based) to calculate the carbon intensity of a fuel pathway from feedstock origin to final use, complying with sustainability criteria [5]. | Required for quantifying the "geodistribution" cost in terms of sustainability and for compliance with regulations like CFPC. |

| Sustainability Certification Standards | Schemes (e.g., RSB, ISCC) that provide verified, audited assurances that feedstocks are produced sustainably, addressing issues like deforestation [5] [30]. | Provides a binary (certified/uncertified) variable for sourcing models to ensure compliance with environmental goals and regulations. |

Advanced Methodologies for Cost Modeling and Supply Chain Optimization

Leveraging Computer Simulation to Model and De-risk Supply Chain Configurations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary computer simulation methodologies used for biomass supply chain modeling? The primary methodologies are multimethod simulation modeling, which combines discrete-event, agent-based, and system dynamics modeling to overcome the limitations of single-method approaches [32]. For optimization, techniques like Multi-Objective Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (MOAOA), Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP), and other multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods are prevalent [33]. These help balance competing objectives such as cost and carbon emissions.

FAQ 2: How can real-time data be integrated into a simulation model for a more accurate digital twin? Efficient real-time data exchange is achieved using lightweight communication protocols like Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) [32]. This protocol is ideal for streaming live data from IoT sensors and machines directly into the simulation environment, allowing the digital twin to sync with real-world assets and respond instantly to changing conditions [32].

FAQ 3: What are the best practices for validating and maintaining a supply chain simulation model? Validation requires a multi-layered approach: checking input data for outliers, running sensitivity analysis, and testing model results against known historical periods [34]. Maintenance is an ongoing process due to model drift. It's essential to have monitoring systems that track performance over time, use version control for model updates, and maintain clear communication protocols when models change [34].

FAQ 4: What common data quality issues disrupt simulation accuracy, and how can they be mitigated? Common issues include using over-aggregated data from standard reports, which loses the variability crucial for simulations, and failing to account for external factors like weather or seasonal adjustments [34]. Mitigation involves using raw transactional data from data lakes, performing rigorous data validation checks, and incorporating a wide range of influencing variables [34].

FAQ 5: How can cloud computing enhance simulation capabilities? Cloud-based solutions, such as AnyLogic Cloud, eliminate hardware constraints by providing scalable computing power [32]. They enable efficient running of complex models, facilitate multi-user access and real-time collaboration, and allow teams to build, edit, and run models directly from a web browser [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Model Produces Unrealistic or Highly Variable Outcomes

Problem: The simulation outputs are erratic, do not align with known historical results, or show extreme sensitivity to minor input changes.

Solution:

- Check Input Data Fidelity: Ensure the model uses granular, raw data instead of aggregated reports. Verify for missing values, outliers, or changes in data distribution over time [34].

- Perform Sensitivity Analysis: Systematically measure how changes in key inputs (e.g., customer demand, supplier lead times) alter the outputs. This helps identify which variables have an disproportionate impact and require more accurate calibration [34].

- Validate Against History: Compare the simulation's results for a specific historical period against the actual, known outcomes from that period to validate the underlying model logic [34].

- Review Model Scope and Assumptions: Confirm that the model includes all critical stages of your specific biomass supply chain (e.g., collection, transportation, preprocessing) and that the assumptions (e.g., transportation modes, emission factors) are correctly documented and applied [33].

Issue 2: Inability to Balance Economic and Environmental Objectives

Problem: The optimization process consistently favors cost reduction at the expense of carbon emissions, or vice versa, failing to find a balanced solution.

Solution:

- Implement a Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm: Use a dedicated multi-objective algorithm like MOAOA, MOPSO, or NSGA-II. These are specifically designed to find a Pareto front of optimal solutions that represent the best possible trade-offs between conflicting goals like cost and emissions [33].

- Formulate a Clear Dual-Objective Model: Ensure your mathematical model explicitly includes both objectives. For example:

- Conduct Scenario Analysis: Run the optimization under different scenarios (e.g., varying carbon tax rates, different fuel prices) to understand the interplay between economic and environmental factors and to identify robust solutions [33].

Issue 3: Simulation Model Suffers from Long Run Times and Poor Performance

Problem: The model takes too long to execute, making it unsuitable for interactive analysis or frequent decision-making.

Solution:

- Leverage Cloud Auto-Scaling: Utilize cloud-based computing resources that can automatically scale up during simulation runs and scale back down upon completion, providing substantial computational power without maintaining expensive permanent infrastructure [32] [34].

- Use Approximation Methods or Pre-Computed Results: For frequent, interactive use, consider developing simplified models or pre-computing a library of common scenarios to speed up delivery of results [34].

- Optimize Model Complexity: Evaluate the level of detail in your model. A sweet spot exists between accuracy and computational speed. For many strategic decisions, a less granular model may be sufficient and much faster [34].

- Modular Design: Build your supply chain simulation in modular components. This allows you to run simplified, high-level models for strategic planning and more detailed modules only for specific operational analyses [34].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm Performance in a Biomass Supply Chain Case Study [33]

| Algorithm | Total Economic Cost (Million USD) | Total Carbon Emissions (Tons CO₂-eq) | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOAOA (Multi-Objective Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm) | 3.21 | 185,400 | Best overall performance in reducing both cost and emissions |

| MOPSO (Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization) | 3.45 | 192,100 | Effective search capability in complex spaces |

| NSGA-II (Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II) | 3.58 | 201,300 | Well-established and provides a good spread of solutions |

Table 2: Impact of Logistics Strategies on Biomass Supply Chain KPIs [33] [35]

| Strategy / Configuration | Estimated Cost Reduction | Estimated Emission Reduction | Implementation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integrating Portable Preprocessing Depots (PDs) | Up to 26.94% | Significant secondary benefit | Forest residue supply; reduces transport distance from collection points [35] |

| Strategic Allocation of Storage Point Supply Quantities | Quantified reduction vs. baseline | Quantified reduction vs. baseline | Agricultural biomass (e.g., corn straw) in a three-stage supply chain [33] |

| Synchromodal Transportation | Mitigates disruption costs | Potential through optimized routing | Freight industry; relies on real-time data on cost, time, and emissions [36] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Objective Optimization of Agricultural Biomass Supply

Objective: To determine the optimal supply quantities at centralized storage points to simultaneously minimize total economic cost and total carbon emissions.

Methodology:

- System Definition: Model the biomass supply chain as a three-stage process:

- Stage 1: Collection and transport from fields to storage points using small agricultural tractors.

- Stage 2: Transport from storage points to preprocessing densification facilities using heavy trucks.

- Stage 3: Transport of solid biofuel from preprocessing facilities to conversion plants using heavy trucks [33].

- Model Formulation: Develop a mathematical model with two objective functions.

- Objective 1 (Cost):

Minimize Z1 = C_transport (Stage1 + Stage2 + Stage3) + C_processing + C_facility - Objective 2 (Emissions):

Minimize Z2 = E_transport (Stage1 + Stage2 + Stage3) + E_processing[33]

- Objective 1 (Cost):

- Algorithm Execution: Implement a Multi-Objective Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (MOAOA) using Python programming. The algorithm should be run for a sufficient number of iterations to achieve a stable Pareto front [33].

- Validation: Compare the results obtained from MOAOA against those from other established algorithms like MOPSO and NSGA-II to verify performance [33].

Protocol 2: Developing a Digital Twin with Real-Time Data Integration

Objective: To create a live, simulation-based digital twin of a biomass supply chain that updates based on real-time IoT data.

Methodology:

- Data Source Identification: Equip key assets (e.g., transportation vehicles, storage silos, processing equipment) with IoT sensors to collect data on location, capacity, temperature, and operational status [32].

- Communication Protocol Setup: Implement an MQTT broker (e.g., Eclipse Mosquitto) to handle the lightweight, real-time data streaming from the IoT devices to the simulation model [32].

- Model Integration: Configure the simulation software (e.g., AnyLogic) to subscribe to the MQTT data streams. Map the incoming live data to the corresponding parameters and variables within the simulation model [32].

- Live Synchronization: Run the digital twin in a live operational mode, where the state of the simulated entities (e.g., truck positions, inventory levels) is continuously updated by the incoming MQTT messages, providing a real-time representation of the physical system [32].

Diagrams

Simulation-Based Digital Twin Workflow

Biomass Supply Chain Optimization Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Components for Biomass Supply Chain Simulation Modeling

| Item / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Multimethod Simulation Software (e.g., AnyLogic) | Provides a flexible modeling environment that supports discrete-event, agent-based, and system dynamics paradigms, either alone or combined, to accurately represent complex biomass systems [32]. |

| Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm (e.g., MOAOA, NSGA-II) | Computational core for solving problems with conflicting objectives; identifies the set of non-dominated solutions (Pareto front) to facilitate trade-off analysis between cost and emissions [33]. |

| Cloud Computing Platform (e.g., AnyLogic Cloud) | Offers scalable computational resources to run complex, resource-intensive simulation models without hardware constraints, enabling collaboration and web-based access [32]. |

| MQTT Broker (e.g., Eclipse Mosquitto) | Enables the integration of real-time data from IoT sensors into the simulation model, a critical component for building and operating a live, accurate digital twin [32]. |

| Digital Twin Framework | A digital replica of the physical biomass supply chain used for analysis, monitoring, and predictive simulation to de-risk configurations and improve decision-making [32] [36]. |

Implementing Digital Solutions and Business Models for Enhanced Transparency and Efficiency

The escalating climate crisis necessitates an urgent shift towards sustainable business models, with the bioeconomy offering a promising alternative through its "Biomass-to-X" strategy for converting biological resources into value-added products [37]. However, the adoption of this approach remains scarce, highlighting the critical need to leverage digital technologies to enhance its feasibility and address persistent cost challenges [37]. Biomass supply chains face significant logistical expenses that often render recovery operations unprofitable, particularly due to lack of coordination and transparency between stakeholders [38] [5]. For researchers and scientists focused on supply chain cost reduction, implementing digital solutions becomes not merely an option but a fundamental requirement for achieving economic viability alongside sustainability goals. This technical support center provides essential guidance for navigating the digital implementation challenges within biomass research contexts, offering troubleshooting and methodological support to accelerate your experimental workflows.

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Digital Implementation Issues

Data Integration and System Performance

Q: Our biomass tracking system is experiencing slow performance when processing real-time sensor data from multiple feedstock sources. What troubleshooting steps should we follow?

A: Slow system performance during multi-source data integration commonly stems from insufficient computational resources or inefficient data handling protocols [39].

- Verify Resource Allocation: Check whether your system meets the minimum computational requirements for handling IoT sensor data streams. Inadequate RAM or storage capacity frequently causes bottlenecks when processing real-time biomass quality metrics (moisture content, composition analysis) [39].

- Optimize Data Processing: Implement data filtering at the collection point to reduce network load. For biomass quality monitoring, configure sensors to transmit only exception data (readings outside predetermined parameters) rather than continuous streams [40].

- Update Integration Protocols: Ensure middleware connecting laboratory instruments, field sensors, and blockchain platforms is running the latest versions. Outdated drivers between analytical equipment and data platforms create performance degradation [39].

Table: Technical Specifications for Biomass Data Integration Platforms

| Component | Minimum Specification | Recommended Specification | Key Biomass Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAM | 8GB | 16GB or higher | Real-time processing of feedstock quality data |

| Storage | 256GB SSD | 1TB NVMe SSD | Storage of historical biomass provenance records |

| Processor | Intel i5 or equivalent | Intel i7/Ryzen 7 or higher | Running blockchain consensus algorithms |

| Network Interface | 1Gbps Ethernet | 10Gbps Ethernet or higher | Handling multiple IoT sensor data streams |

| OS Compatibility | Windows 10/Linux | Windows 11/Linux LTS | Support for biomass management platforms |

Blockchain and Traceability Implementation

Q: We're encountering connectivity issues between IoT devices on biomass containers and our blockchain ledger. How can we diagnose and resolve these problems?

A: Connectivity failures in blockchain-based traceability systems typically originate from either network issues or device configuration problems [40].

- Verify Network Infrastructure: Ensure continuous network coverage along the biomass supply chain route, especially in remote agricultural or forest areas where signal loss may occur [39]. Implement network boosters or satellite backups for critical tracking points.

- Check Device Configuration: Confirm that IoT sensors are properly configured to communicate with your blockchain infrastructure. Update device firmware to ensure compatibility with distributed ledger protocols [40].

- Validate Smart Contracts: Test smart contracts with sample biomass shipment data to identify potential execution failures before full deployment. Ensure contracts properly execute when predefined conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity thresholds) are met [40].

Q: How can we resolve synchronization delays in our distributed ledger for international biomass shipments?

A: Ledger synchronization issues in international biomass supply chains often relate to latency across geographical nodes and consensus mechanism inefficiencies.

- Node Optimization: Position validation nodes at strategic points along major biomass shipping routes to reduce latency [5] [40].

- Consensus Configuration: Adjust consensus parameters (e.g., proof-of-work difficulty) to balance security needs with transaction speed for time-sensitive biomass quality data [40].

- Data Prioritization: Implement a tiered data recording system where critical biomass quality parameters receive blockchain confirmation priority over less time-sensitive information.

Sensor and Peripheral Device Issues

Q: Our biomass quality sensors (moisture, composition) are not being recognized by the data collection system. What steps should we take?

A: Unrecognized sensors severely impact biomass quality monitoring and require systematic troubleshooting [39].

- Inspect Physical Connections: Check USB ports and cables for damage, especially in field deployment environments where equipment faces weather exposure [39].

- Update Device Drivers: Ensure compatible drivers are installed for your specific sensor models. Contact sensor manufacturers for specialized drivers tailored to biomass measurement applications.

- Test on Alternate Systems: Verify sensor functionality on different devices to isolate whether the issue originates from the sensors themselves or the host data collection system [39].

Essential Experimental Protocols for Digital Solution Testing

Protocol 1: Blockchain Transparency Implementation

Objective: To quantitatively assess the impact of blockchain implementation on supply chain transparency metrics in biomass-to-energy pathways.

Materials:

- Distributed ledger platform (e.g., Hyperledger Fabric, Ethereum)

- IoT sensors for biomass quality parameters (moisture, composition)

- Data analytics software (Python/R with appropriate libraries)

- Biomass samples from multiple feedstock sources

Methodology:

- System Configuration: Deploy a permissioned blockchain network with nodes representing key stakeholders (farmers, processors, transporters) [40].

- Data Integration: Configure API connections between existing biomass tracking systems and the blockchain infrastructure [40].

- Smart Contract Development: Code and deploy smart contracts that automatically execute upon verification of predefined biomass quality parameters [40].

- Testing Protocol: Introduce simulated biomass shipments with varying quality parameters and track transparency metrics.

- Data Collection: Record transaction transparency scores, data immutability verification times, and stakeholder access patterns.

Validation Metrics:

- Time to trace biomass origin

- Reduction in documentation errors

- Stakeholder transparency satisfaction scores

Protocol 2: Digital Tool Integration for Fire Risk Mitigation

Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of a digital coordination platform in reducing wildfire risk through improved biomass recovery rates.

Materials:

- Digital biomass mapping platform

- GIS software and satellite imagery

- Residual biomass availability datasets

- Fire risk assessment models

Methodology:

- Baseline Assessment: Map current residual biomass accumulation in high-fire-risk areas using satellite data and field verification [38].

- Platform Deployment: Implement a digital tool connecting biomass producers, collectors, and end-users to facilitate coordination [38].

- Monitoring Framework: Track biomass recovery rates before and after platform implementation across selected test regions.

- Fire Risk Analysis: Calculate changes in fire risk indices based on reduced biomass fuel loads using standardized fire risk models [38].

- Economic Assessment: Document cost reductions achieved through improved logistics coordination and reduced fire management expenses.

Digital Protocol for Fire Risk Mitigation

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Digital Infrastructure

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Digital Biomass Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blockchain Platforms | Hyperledger Fabric, Ethereum, Corda | Supply chain transparency | Creates immutable records of biomass transactions and quality data [40] |

| IoT Sensors | Moisture meters, GPS trackers, Composition analyzers | Real-time biomass monitoring | Collects field data on biomass location, quality parameters, and environmental conditions [40] [38] |

| Data Analytics | Python (Pandas, NumPy), R, TensorFlow | Biomass pattern analysis | Processes large datasets to identify optimization opportunities in supply chains [37] |

| Digital Twins | 3D biomass process modeling, Simulation software | System optimization testing | Creates virtual replicas of physical biomass supply chains for risk-free experimentation [37] |

| Remote Support Tools | Remote desktop software, VPN systems | Technical troubleshooting | Enables remote diagnosis and resolution of technical issues across distributed research teams [39] |

Advanced Technical Support: Specialized Research Scenarios

Interoperability Framework Development

Q: How can we establish seamless data exchange between legacy laboratory equipment and new blockchain platforms without compromising security?

A: Creating interoperability between legacy systems and modern platforms requires a layered security approach.

- API Gateway Implementation: Develop RESTful APIs with robust authentication protocols to bridge equipment data formats with blockchain requirements [40].

- Data Standardization: Convert diverse biomass measurement outputs (from various analytical instruments) into standardized formats (e.g., JSON-LD) for consistent blockchain recording [37] [40].