Spatial Intelligence: How GIS is Revolutionizing Biomass Analysis for Sustainable Energy and Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in biomass spatial analysis, a critical field for sustainable energy and environmental research.

Spatial Intelligence: How GIS is Revolutionizing Biomass Analysis for Sustainable Energy and Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) in biomass spatial analysis, a critical field for sustainable energy and environmental research. It covers foundational concepts, including the 'resource-supply chain-demand-optimization' operational logic and the theory of energy landscapes. The content details advanced methodological approaches like Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) and Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP) for site selection and logistics optimization. It further addresses troubleshooting for computational challenges and data heterogeneity, and offers validation techniques through sensitivity analysis and comparative performance evaluation of machine learning models like XGBoost and Random Forest. Tailored for researchers and scientists, this guide synthesizes current trends and practical applications to empower professionals in leveraging spatial data for informed decision-making in biomass resource management.

Understanding the GIS and Biomass Nexus: Core Concepts and Spatial Operational Logic

Defining Biomass Energy Spatial Planning and its Role in Carbon Neutrality Goals

Biomass Energy Spatial Planning is a geospatial analytical process that identifies optimal locations for biomass feedstock production and bioenergy facility siting to maximize carbon sequestration and emission reduction, directly supporting regional and national carbon neutrality goals. This planning integrates Geographic Information Systems to analyze spatial variables including biomass availability, transportation networks, carbon sink zones, and existing land use, creating a structured framework for aligning bioenergy development with the "dual carbon" targets of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality [1] [2]. The foundational principle recognizes land as the primary carrier of carbon sources and sinks, where strategic spatial organization of biomass resources can significantly influence regional carbon budgets [1].

The Qinba Mountain region case study demonstrates this approach, implementing a carbon neutral spatial zoning framework that considers natural, economic, ecological, and land resource factors across 81 county-level units [1]. This integration of spatiotemporal carbon dynamics with multi-scenario predictions enables planners to designate zones for carbon sink functionality, low-carbon development, and carbon source optimization, providing a replicable model for regional carbon neutrality planning [1].

Key Concepts and Analytical Framework

Core Principles

Biomass spatial planning operates on several interconnected principles essential for carbon neutrality:

- Spatial Autocorrelation of Resources: Following Tobler's First Law of Geography, biomass resources and carbon dynamics exhibit spatial dependence where near things are more related than distant things, necessitating spatial autocorrelation analysis through indices like Moran's I, Geary's C, and Getis' G [3].

- Land Use Carbon Equilibrium: Planning must balance carbon emissions from anthropogenic activities with carbon sequestration through natural sinks, achieving net-zero carbon emission through strategic spatial allocation of land uses [1].

- Circular Bioeconomy Integration: Effective planning transforms residual biomass materials (agricultural residues, used cooking oils, forestry waste) into renewable fuels within a circular economy framework, reducing waste and fossil fuel dependence [3].

Quantitative Carbon Metrics

Table 1: Core Carbon Assessment Metrics for Biomass Spatial Planning

| Metric | Calculation Formula | Application in Spatial Planning |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Emission | CE = Σ(EC × EF) where EC is energy consumption and EF is emission factor [1] | Identifies high-emission zones requiring intervention and optimal locations for emission reduction projects |

| Carbon Sequestration | CS = Σ(LA × CF) where LA is land area and CF is carbon sequestration factor [1] | Maps natural carbon sink areas for protection and identifies potential areas for sink enhancement |

| Net Carbon Emission | NCE = CE - CS [1] | Determines regional carbon balance status and guides zoning decisions based on surplus/deficit |

| Carbon Footprint | Cf = CE / CS [1] | Measures ecological pressure and identifies regions exceeding carrying capacity |

| Carbon Emission Potential | CEP = f(industrial structure, population, wealth, technology) [1] | Predicts future emission scenarios and informs long-term spatial strategy development |

Application Notes: Implementation Framework

Data Requirements and Processing

Successful biomass spatial planning requires integrating multiple data domains:

- Biomass Resource Data: Spatial distribution of agricultural residues, forestry biomass, and organic wastes quantified in metric tons per year with seasonal variations [2] [3]. The assessment of Chinese biomass potential at 1 km resolution provides a model for comprehensive resource mapping [2].

- Carbon Flux Data: Direct measurements and proxy indicators of carbon emissions and sequestration across land use types, often derived from remote sensing platforms [1].

- Anthropogenic Factor Data: Population density, energy consumption patterns, industrial activities, and transportation networks that influence carbon emission patterns [1].

- Environmental Constraints: Protected areas, water sources, steep slopes, and other features limiting development possibilities [2].

Spatial Zoning Protocol

The Qinba Mountain case study established a replicable zoning framework categorizing regions into five distinct functional zones [1]:

- Carbon Sink Functional Zone: Areas with high carbon sequestration capacity where protection and enhancement of natural ecosystems is prioritized.

- Low-Carbon Development Zone: Regions suitable for controlled development with integrated carbon mitigation measures.

- Net-Carbon Stabilization Zone: Transitional areas maintaining balance between emission and sequestration.

- High-Carbon Control Zone: Regions with excessive emissions requiring strict regulation and reduction measures.

- Carbon Source Optimization Zone: Areas where existing carbon sources can be optimized through technology and process improvements.

Technology Integration Framework

Advanced biomass conversion technologies significantly influence spatial planning decisions:

- Solar-Enhanced Char-Cycling Biomass Pyrolysis: Integrates concentrated solar power with traditional pyrolysis, reducing operational GHG emissions while enhancing energy efficiency and resource recovery [2]. This technology requires co-location of high biomass availability areas with strong direct normal irradiance levels.

- Catalytic Biofuel Production: Utilizes natural mineral catalysts like palygorskite for greener biofuel production from waste cooking oils and lignocellulosic biomass [3].

- Distributed Processing Models: For geographically dispersed biomass resources, mobile pyrolysis units can convert biomass to bio-oil in situ, reducing transportation emissions and costs [3].

Experimental Protocols

GIS-Based Biomass Carbon Assessment Protocol

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for GIS Biomass Analysis

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| QGIS | Cross-platform, open-source desktop GIS for spatial analysis and visualization [2] | Primary platform for spatial data integration, analysis, and map production |

| GeoDA | Open-source software for spatial autocorrelation analysis [3] | Calculating global and local indices of spatial autocorrelation (Moran's I, Geary's C) |

| R Programming | Statistical computing and graphics for advanced spatial analysis [3] | Implementing custom spatial statistical models and generating advanced visualizations |

| CLUE-s/FLUS/PLUS Models | Cellular Automata models for predicting land use changes under various scenarios [1] | Projecting future land use patterns and associated carbon implications |

| STIRPAT Model | Stochastic Impacts by Regression on Population, Affluence and Technology [1] | Predicting future carbon emissions under different development scenarios |

Protocol 1: Spatial Carbon Budget Assessment

Objective: Quantify spatial patterns of carbon emissions and sequestration across a study region.

Workflow:

- Land Use Classification: Reclassify land use types into standardized categories (cropland, shrubland, forest, grassland, water area, urban land, unused land) compatible with carbon coefficient databases [1].

- Carbon Emission Inventory: Calculate emissions from agricultural production (fertilizer, pesticide, agricultural plastic film, irrigation) and urban energy consumption using established emission factors [1].

- Carbon Sequestration Mapping: Estimate carbon sequestration potential by vegetation type using remote sensing-derived vegetation indices and field validation plots [1].

- Net Carbon Emission Calculation: Compute spatial balance between emission and sequestration at appropriate administrative or grid units.

- Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis: Apply global and local indices to identify clusters of high/low carbon emissions and sequestration [3].

Biomass Facility Siting Protocol

Protocol 2: Optimal Location Analysis for Solar-Biomass Integration

Objective: Identify suitable locations for solar-enhanced biomass pyrolysis facilities based on resource availability and technical constraints.

Workflow:

- Biomass Resource Assessment: Map spatial distribution of agricultural and forestry residues using statistical data and remote sensing [2] [3].

- Solar Resource Evaluation: Analyze direct normal irradiance levels using satellite data and apply threshold criteria (e.g., DNI > 1400 kWh/m²) [2].

- Constraint Mapping: Identify excluded areas including protected zones, steep slopes, water bodies, and urban centers [2].

- Transportation Cost Analysis: Calculate biomass collection radii based on road networks and transportation economics.

- Site Suitability Modeling: Apply multi-criteria decision analysis integrating biomass availability, solar resources, infrastructure access, and environmental constraints.

Case Study Implementation

Chinese Provincial-Scale Assessment

A comprehensive assessment of Solar-Enhanced Char-Cycling Biomass Pyrosis potential across China demonstrates the real-world application of biomass spatial planning principles [2]:

Table 3: GIS Assessment Results for SCCP Implementation in China

| Parameter | Low DNI Threshold (1400 kWh/m²) | Medium DNI Threshold (1600 kWh/m²) | High DNI Threshold (1800 kWh/m²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suitable Area | 12.25% of national territory | 5.32% of national territory | 2.14% of national territory |

| Biomass Availability | 25.68 million tons/year | 18.79 million tons/year | 9.46 million tons/year |

| Biofuel Production Potential | 4.02 billion liters/year | 2.94 billion liters/year | 1.48 billion liters/year |

| CO₂ Reduction Potential | 6.74 million tons/year | 4.93 million tons/year | 2.48 million tons/year |

| Key Provinces | Xinjiang, Tibet, Gansu, Qinghai | Xinjiang, Tibet, Qinghai | Xinjiang, Tibet |

Greek Residual Biomass Utilization

Research in Greece demonstrates spatial planning approaches for diverse biomass feedstocks [3]:

- Waste Cooking Oils: Significant quantities (163.17 million L/year) concentrated in urban and tourist areas, suitable for centralized collection and processing [3].

- Lignocellulosic Biomass: Substantial resources (4.5 million tons/year) but geographically fragmented, necessitating decentralized mobile processing solutions [3].

- Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis: Revealed strong correlation (r = 0.87) between WCO production and per capita income, informing targeted collection strategies [3].

Biomass Energy Spatial Planning represents a critical methodology for achieving carbon neutrality goals through systematic, data-driven spatial organization of bioenergy systems. By integrating GIS-based resource assessment, carbon flux analysis, and multi-criteria decision support, this approach enables regions to strategically deploy biomass resources to maximize carbon mitigation while supporting sustainable development objectives. The experimental protocols and case studies presented provide researchers and planners with replicable methodologies for implementing this approach across varied geographical contexts, contributing to the global effort to combat climate change through optimized spatial management of carbon cycles.

Resource-Supply Chain-Demand-Optimization Spatial Operational Logic

Application Notes: Conceptual Framework and Quantitative Foundations

The Resource-Supply Chain-Demand-Optimization spatial operational logic provides a integrated framework for managing biomass from residual resources to final energy product delivery. This logic is critical for overcoming the inherent challenges of biomass, including its geographical dispersion, low density, and variable availability, which directly impact the economic viability and environmental sustainability of biofuel production [3] [4]. The framework strategically connects resource assessment, supply chain design, demand location, and mathematical optimization to enable a circular economy for energy production.

Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and spatial analysis form the backbone of the resource assessment phase. In the Greek case study, GIS was used to record and analyze quantities of Waste Cooking Oils (WCOs), Household Oils (HOs), and lignocellulosic biomass across 325 municipal units [3]. Spatial autocorrelation techniques, including Moran's I, Geary's C, and Getis's G indices, were applied to identify significant spatial clustering of these resources [3]. This analysis revealed that WCO production was strongly correlated with per capita income (r = 0.87) and was concentrated in large urban and tourist areas [3]. Conversely, lignocellulosic biomass, while significant in total quantity, exhibited geographical fragmentation and heterogeneity, making centralized collection economically challenging [3].

The operational logic dictates different collection and processing strategies based on the spatial characteristics of the resource. For concentrated resources like WCOs, a centralized model with small autonomous collection units and central processing plants is feasible. For widely dispersed resources like agricultural residues, the logic suggests decentralized approaches, such as small mobile collection units that perform initial conversion (e.g., to bio-oil via rapid pyrolysis) directly at the source to reduce transport costs [3]. This approach was also validated in a study on citrus biomass in Sicily, where GIS and habitat modeling identified 47,706 hectares suitable for cultivation, estimating a potential 184,340 tonnes of biomass for energy production [5].

Optimization models are employed to mathematically define the most efficient supply chain configuration. These are often formulated as Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) problems aiming to maximize the system's Net Present Value (NPV) [4]. The optimization determines the optimal locations for storage and conversion facilities, transportation links, and operational parameters for the conversion process itself, such as a Steam Rankine Cycle for combined heat and power generation [4].

Table 1: Quantitative Biomass Potential from Regional Case Studies

| Region | Biomass Type | Total Quantity | Energy/Biofuel Potential | Key Spatial Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greece [3] | Waste Cooking Oils (WCOs) | 163.17 million L/year | Green Diesel | Concentration in urban & tourist areas |

| Greece [3] | Lignocellulosic Biomass | 4.5 million tons/year | Bio-oil via pyrolysis | Geographically fragmented & heterogeneous |

| Sicily, Italy [5] | Citrus Cultivation Biomass | 184,340 tons | 16,461,520 Nm³ of Biogas | Northern & eastern regions show highest potential |

| Slovenia [4] | Forest & Agricultural Biomass | Not Specified | ~4 MW Electricity, 65 MW Heat | Model for a small region, maximizing NPV |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GIS-Based Resource Assessment and Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

This protocol details the methodology for mapping biomass resources and analyzing their spatial distribution patterns.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- Software: R programming language (v4.4.1 or higher), QGIS (v3.40 or higher), GeoDA (v1.22 or higher) [3].

- Data Sources: National statistical services (e.g., Hellenic Statistical Authority - ELSTAT), open government GIS data portals, data from biomass collection companies, and scientific literature for estimation factors [3].

II. Methodology

Data Collection and Geographic Database Creation:

- Collect data on biomass quantities (e.g., WCOs, agricultural residues) at the highest possible spatial resolution (e.g., municipal level) [3].

- Integrate data from on-site recordings, sampling, and open sources. For missing data, use proxy variables like population or per capita income for estimation, documenting the associated uncertainty [3].

- Create a unified geographic database linking each administrative unit's spatial boundary with its descriptive biomass data.

Data Visualization and Preliminary Analysis:

Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis:

- Objective: To statistically determine if biomass resources are clustered, dispersed, or randomly distributed in space.

- Calculate global spatial autocorrelation indices:

- Global Moran's I: Assesses overall clustering across the entire study area. A positive value indicates clustering, a negative value indicates dispersion, and near-zero suggests randomness [3].

- Geary's C: Another global index, inversely related to Moran's I.

- Calculate local spatial autocorrelation indices (LISA):

- Local Moran's I or Getis's G: Identifies specific locations of statistically significant hot spots (high-value clusters) and cold spots (low-value clusters) of biomass resources [3].

- Interpret the results to inform supply chain strategy (e.g., centralized collection in hot spots, decentralized in cold spots).

Protocol 2: Biomass Supply Chain and Process Optimization Modeling

This protocol outlines the steps for developing an integrated optimization model for the biomass supply network and conversion process.

I. Research Reagent Solutions

- Software: Optimization software compatible with MINLP/MILP solvers (e.g., GAMS, AMPL, or Python with Pyomo).

- Model Inputs: Georeferenced biomass data from Protocol 1, economic parameters (feedstock cost, product prices, investment costs), transportation costs, and techno-economic parameters for the conversion process (e.g., Steam Rankine Cycle efficiency) [4].

II. Methodology

Problem Scoping and Data Preparation:

- Define the spatial scope of the supply chain (e.g., regional, national).

- Define the objective, typically to maximize Net Present Value (NPV) [4].

- Structure the supply chain into layers: biomass supply zones, storage locations, and conversion plants [4].

- Gather all relevant cost, price, and technical efficiency data.

Model Formulation:

- Formulate the problem as an MINLP to simultaneously optimize strategic (facility location) and operational (biomass flow, process conditions) decisions [4].

- Decision Variables: Include binary variables for facility location, continuous variables for biomass flows, and process variables (e.g., steam pressure, temperature) [4].

- Constraints: Incorporate biomass availability, capacity limits, mass and energy balances, and demand requirements.

- Objective Function: Define as the NPV, accounting for capital and operational expenditures (CAPEX/OPEX) and revenue from product sales [4].

Model Solving and Sensitivity Analysis:

- Solve the MINLP using an appropriate algorithm (e.g., Branch and Bound).

- Perform sensitivity analysis on key parameters (e.g., biomass supply uncertainty, fluctuations in electricity prices, feedstock costs) to test the robustness of the optimal solution [4].

Table 2: Key Components of a Biomass Supply Chain Optimization Model

| Model Component | Description | Example Parameters/Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Objective Function [4] | The goal to be achieved, typically economic. | Maximize Net Present Value (NPV). |

| Decision Variables [4] | Choices the model can make. | Facility location (binary), biomass flows (continuous), process conditions. |

| Constraints [4] | Limitations the model must respect. | Biomass availability, facility capacity, technology conversion efficiency. |

| Uncertainty Analysis [4] | Testing model robustness to change. | Sensitivity of NPV to biomass supply, product prices, and policy changes. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Biomass Spatial Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| QGIS / GeoDA [3] | Software | Open-source GIS platforms for spatial data management, visualization, and basic spatial analysis. |

| R Programming Language [3] | Software | Statistical computing and graphics; used for advanced spatial statistics and autocorrelation calculations. |

| MINLP Solver [4] | Software / Algorithm | Solves complex optimization problems integrating discrete facility location and continuous process variables. |

| Global Moran's I [3] | Statistical Index | Measures global spatial autocorrelation to determine if a resource dataset is clustered, dispersed, or random. |

| Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) [3] | Statistical Method | Identifies local clusters (hotspots and coldspots) of high or low values within a spatial dataset. |

| Steam Rankine Cycle (SRC) Model [4] | Process Model | Simulates the thermodynamic cycle for converting biomass heat into electricity and power in optimization. |

| APCA Contrast Calculator [6] | Design Tool | An advanced algorithm for checking color contrast in visualizations to ensure accessibility for all users. |

The concept of an "energy landscape" provides a critical framework for understanding the spatial distribution, planning, and management of energy systems within a geographical context. When applied to biomass energy, this concept encompasses the analysis of feedstock availability, conversion facility siting, logistics, and the integration of renewable energy systems into existing landscapes. The fundamental principle, as captured by Tobler's First Law of Geography, states that "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant ones" [3]. This law establishes the theoretical foundation for spatial analysis in biomass research, emphasizing that geographic proximity profoundly influences the economic viability and environmental impact of biomass supply chains.

The energy landscape approach integrates spatial planning with energy modeling to address key challenges in biomass utilization, including the high spatial footprint of biomass compared to other renewable carriers and the temporal and spatial variability of resources [7]. This methodology enables researchers and planners to identify optimal locations for biomass facilities, assess resource potentials, and understand the complex interactions between energy infrastructure and environmental systems, thereby supporting the transition to sustainable energy systems.

Core Theoretical Frameworks

Spatial Autocorrelation in Biomass Distribution

Spatial autocorrelation is a core statistical theory applied to energy landscape analysis, measuring the degree to which similar values for a variable are clustered in space. For biomass research, this reveals whether areas of high biomass potential are geographically concentrated or dispersed.

- Global Indices: Moran's I, Geary's C, and Getis' G are primary indices used to assess overall clustering patterns across an entire study region. A positive Moran's I value indicates clustering of similar values, while a negative value suggests dispersion.

- Local Indices: Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) identify specific clusters or spatial outliers, such as "hot spots" of high biomass availability or "cold spots" of scarcity [3].

Application of these indices to waste cooking oil (WCO) distribution in Greece revealed significant spatial clustering, with strong positive correlation (r = 0.87) between WCO quantities and per capita income across municipalities, demonstrating how socio-economic factors shape the biomass energy landscape [3].

Multicriteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) for Facility Siting

Multicriteria Decision Analysis provides a structured framework for evaluating potential biomass facility locations against multiple, often competing criteria. The weighted overlay method, implemented through GIS, allows researchers to integrate diverse spatial factors into a unified suitability model [8].

Key criteria incorporated in biomass MCDA include:

- Biomass Availability: Crop areas, forest residues, shrub/grasslands

- Infrastructure Factors: Distance from water sources, road accessibility

- Geophysical Constraints: Topography (slope), aspect, and land use/land cover (LULC)

- Economic Considerations: Proximity to energy demand centers and transportation networks

A study in Nigeria successfully applied this methodology, identifying the most suitable areas for biomass plants in northern regions including Niger, Zamfara, and Kano States based on the synthesis of these criteria [8].

Application Notes: Quantitative Biomass Potential Assessments

Regional Biomass Energy Potentials

Table 1: Theoretical, Technical, and Economic Biomass Potentials by Region in Nigeria (PJ/yr) [8]

| Region | Crop Residues Theoretical | Crop Residues Technical | Crop Residues Economical | Forest Residues Theoretical | Forest Residues Technical | Forest Residues Economical |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North-East | 1,163.32 | 399.73 | 110.56 | - | - | - |

| South-East | 52.36 | 17.99 | 4.98 | 1.79 | 1.08 | 0.30 |

| North-West | - | - | - | 260.18 | 156.11 | 43.18 |

Global Biomass Market Outlook

Table 2: Global Biomass Energy Market Projections, 2024-2035 [9] [10]

| Parameter | 2024 Baseline | 2035 Projection | CAGR | Key Market Trends |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size (USD) | $99-120 Billion | $160-211.51 Billion | 4.46%-6.5% | BECCS, Advanced Biofuels, Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) |

| Regional Leadership | Asia-Pacific (Highest Demand) | Europe (Fastest Growth) | - | Stringent EU carbon regulations, Asia-Pacific energy demand growth |

| Primary Applications | Power Generation, Commercial Heating, Industrial Applications | Expansion into circular bioeconomy, co-firing with coal |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GIS-Based Biomass Potential Assessment

Objective: To quantify theoretical, technical, and economical biomass energy potentials at regional levels using GIS and remote sensing data.

Workflow:

Methodology Details:

Data Collection and Integration

- Acquire multi-temporal Landsat imagery for Land Use Land Cover (LULC) classification

- Collect Digital Elevation Model (DEM) data for topographic analysis

- Gather GPS field survey data stored in .GPX format

- Integrate statistical data from government sources on agricultural production and forest inventories [8]

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) Analysis

- Calculate NDVI using the formula: NDVI = (NIR - RED) / (NIR + RED)

- Values range from -1 to +1, with dense green vegetation typically showing values >0.6

- Analyze vegetation density and health as a proxy for biomass productivity [8]

Spatial Analysis and Potential Calculation

- Theoretical Potential: Calculate total biomass availability from all sources without constraints

- Technical Potential: Apply constraints of accessibility, technology efficiency, and land use restrictions

- Economic Potential: Factor in collection, transportation, and conversion costs to determine commercially viable biomass [8]

Objective: To identify spatial clustering patterns in biomass distribution using global and local indices of spatial autocorrelation.

Workflow:

Methodology Details:

Data Preparation

- Compile biomass quantity data by geographical units (municipalities, districts)

- Create spatial weights matrix defining neighborhood relationships between geographical units

- Ensure data completeness through estimation methods for missing values, with uncertainty analysis [3]

Global Spatial Autocorrelation

- Calculate Moran's I index: Values range from -1 (perfect dispersion) to +1 (perfect clustering)

- Compute Geary's C: Values range from 0 (positive autocorrelation) to >1 (negative autocorrelation)

- Determine Getis' G: Identifies concentration of high or low values [3]

Local Spatial Autocorrelation (LISA)

- Identify local clusters of high values (hot spots) surrounded by high values

- Identify local clusters of low values (cold spots) surrounded by low values

- Detect spatial outliers: high values surrounded by low values, or low values surrounded by high values

Interpretation and Strategy Development

- Correlate spatial patterns with socio-economic factors (e.g., per capita income, tourism activity)

- Design optimized collection strategies based on clustering analysis

- For clustered resources: Implement centralized collection systems

- For dispersed resources: Develop decentralized, mobile collection units [3]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential GIS and Spatial Analysis Tools for Biomass Energy Research

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Tool | Primary Function in Biomass Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIS Platforms | ArcGIS, QGIS | Spatial data integration, analysis, and visualization | Multicriteria site suitability analysis for biomass plants [8] |

| Remote Sensing Tools | Landsat Imagery, NDVI Analysis | Biomass quantification, land cover classification | Crop residue estimation using vegetation indices [8] |

| Spatial Analysis Software | GeoDA, R Programming | Spatial autocorrelation analysis, statistical modeling | Identifying biomass clustering patterns using Moran's I [3] |

| Data Sources | National Statistics, GPS Surveys, Municipal Data | Primary data collection and validation | Waste cooking oil quantification through field surveys [3] |

| Color Palette Tools | ColorBrewer 2.0, Viz Palette | Accessible color scheme creation for data visualization | Designing colorblind-safe maps for biomass potential [11] [12] |

Implementation Framework and Best Practices

Data Visualization Standards for Biomass Mapping

Effective visualization of biomass energy landscapes requires adherence to established cartographic principles:

- Sequential Color Schemes: Use single-hue or multi-hue gradients with light colors for low values and dark colors for high values to represent continuous data like biomass density [13] [12]

- Categorical Color Schemes: Employ distinct hues without inherent ordering for categorical data like land use classification, limiting categories to 4-6 for optimal differentiation [12]

- Accessibility Compliance: Ensure minimum contrast ratios of 4.5:1 for text elements and use colorblind-safe combinations (blue-orange instead of red-green) with tools like Color Oracle for verification [11] [12]

- Diverging Color Schemes: Implement contrasting colors on opposite ends of a scale with neutral midpoints to highlight deviation from baseline values, such as biomass availability compared to regional averages [12]

Optimization Strategies for Biomass Collection

Based on spatial analysis findings, tailored collection strategies emerge:

- For Clustered Resources (e.g., waste cooking oils in urban/tourist areas): Develop fixed infrastructure with centralized processing plants serving regional units [3]

- For Dispersed Resources (e.g., lignocellulosic biomass across rural areas): Implement decentralized mobile collection units with potential in-situ pre-processing (e.g., mobile pyrolysis units) to reduce transportation costs [3]

- Integrated Spatial Modeling: Combine biomass availability data with transportation networks, topography, and existing infrastructure to minimize logistics costs and environmental impacts [8]

Essential Geospatial Data Types for Biomass Assessment (e.g., ESA CCI AGB, Soil Data, Land Use)

Accurate biomass assessment is fundamental to understanding global carbon cycles and informing climate policy. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) enable the integration and analysis of diverse geospatial data types to model and map biomass at various scales. This application note details the essential geospatial datasets, with a focus on European Space Agency Climate Change Initiative (ESA CCI) products, that form the cornerstone of robust biomass spatial analysis for climate science and environmental research. The integration of above-ground biomass (AGB) maps, land cover classifications, and soil moisture data provides a multi-dimensional view of ecosystem dynamics, allowing researchers to move beyond simple inventory to process-based understanding. These datasets are particularly powerful when combined with field observations, such as the USDA Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data used in the United States, to create and validate spatially explicit biomass prediction models [14].

Essential Geospatial Data Types

For a comprehensive biomass assessment, researchers should integrate several core geospatial data types, each contributing unique information about the ecosystem. The following table summarizes the key datasets, their primary sources, and specific applications in biomass research.

Table 1: Essential Geospatial Data Types for Biomass Assessment

| Data Type | Key Product/Example | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Coverage | Primary Application in Biomass Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Above-Ground Biomass (AGB) | ESA CCI Biomass (v6.0) [15] | 100 m | 2007, 2010, 2015-2022 | Direct quantification of carbon stocks; monitoring biomass change over time. |

| Land Cover/Land Use | ESA CCI Land Cover [16] | 300 m | 1992-2020 | Contextualizes biomass data; provides basis for stratification and Plant Functional Type (PFT) conversion. |

| Soil Moisture | ESA CCI Soil Moisture (v09.1) [17] [18] | ~25 km | 1978-2023 | Indicates ecosystem water stress; informs models on decomposition rates and soil carbon dynamics. |

| Burned Area | ESA Fire CCI (e.g., FireCCI51) [19] [20] | 250 m - 300 m | 1982-2024 (varies by product) | Quantifies biomass loss from wildfires; essential for disturbance and emissions accounting. |

| Active Fire & Thermal Anomalies | Integrated within Fire CCI products [19] | Varies by sensor | Varies by product | Supports near-real-time detection of fires and validation of burned area maps. |

Experimental Protocols for Biomass Assessment

Protocol 1: Multi-Scale Above-Ground Biomass Mapping and Change Analysis

Objective: To generate a spatially continuous map of above-ground biomass and quantify its change over a defined period using ESA CCI products.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Data Sources for AGB Mapping

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Protocol | Source/Access |

|---|---|---|

| ESA CCI AGB Maps (v6.0) | Primary data layer providing per-pixel biomass estimates (Mg/ha) and associated uncertainty. | ESA CCI Open Data Portal [15] |

| ESA CCI AGB Change Maps | Provides pre-calculated change products for specific intervals (e.g., 2022-2021, 2020-2010). | ESA CCI Open Data Portal [15] |

| ESA CCI Land Cover Maps | Used to mask non-forested areas and stratify analysis by biome or vegetation type. | ESA CCI Open Data Portal [16] |

| QGIS / ArcGIS / Python Environment | Software platforms for data integration, spatial analysis, and visualization. | Open Source / Commercial |

Python esa_cci_sm Package |

Specialized package for reading and processing CCI data files in NetCDF format. | GitHub Repository [17] [18] |

Workflow:

- Data Acquisition and Preparation: Download the suite of global AGB maps (2007, 2010, 2015-2022) and corresponding uncertainty layers from the ESA CCI Biomass data portal [15]. Simultaneously, download the land cover map for your target year.

- Data Preprocessing: Reproject all datasets to a consistent coordinate system and spatial resolution. Use the land cover map to create a forest mask, isolating pixels for analysis. The AGB data is typically analyzed at its native 100m resolution, but aggregated products (1km, 10km, etc.) are also available for coarse-scale studies [15].

- Change Calculation: Calculate biomass change between two time points (e.g., T1 and T2) using the formula:

AGB_Change = AGB_T2 - AGB_T1. Alternatively, use the pre-generated AGB change maps for specific consecutive years or decadal intervals [15]. - Uncertainty Propagation: Propagate the standard deviation of the AGB estimates through the change calculation to quantify the uncertainty in the observed biomass change.

- Validation (Ground-Truthing): Validate the AGB and AGB change maps using independent field data, such as national forest inventory plots. This step is critical for assessing map accuracy and should report metrics like Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [14].

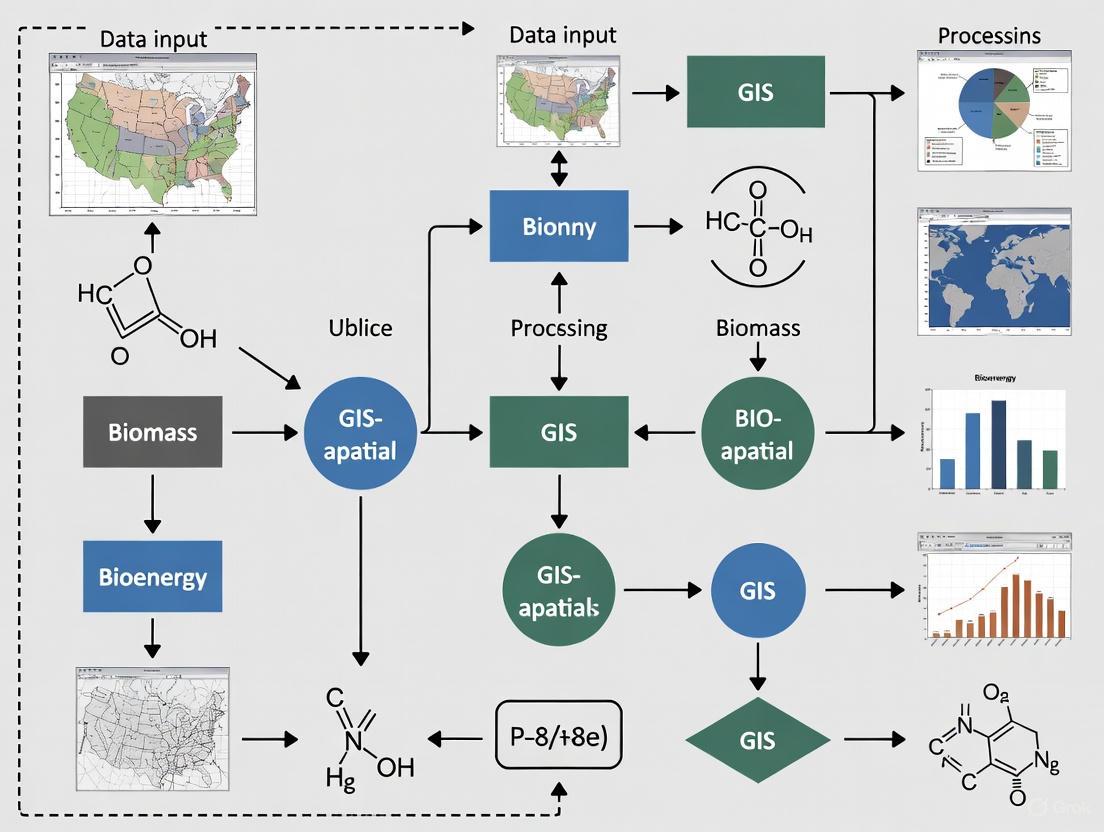

Figure 1: Workflow for AGB mapping and change analysis.

Protocol 2: Integrated Biomass Prediction Using Multi-Modal Remote Sensing

Objective: To develop a high-resolution, machine learning-based biomass prediction model by integrating multi-sensor remote sensing data with field inventory plots.

This protocol is based on a contemporary study that achieved an RMSE of 27.19 Mg ha⁻¹ and R² of 0.41 for a temperate forest [14].

Workflow:

- Predictor Variable Extraction: Acquire remote sensing data from multiple sources. For each field plot (e.g., FIA subplot), extract a suite of explanatory variables. The cited study used 67 variables from:

- Airborne LiDAR: For forest structural metrics (canopy height, vertical complexity).

- Sentinel-2 Satellite Imagery: For vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI) and spectral bands.

- Aerial Imagery (NAIP): For high-resolution texture metrics (e.g., Grey-Level Co-Occurrence Matrix - GLCM).

- Ancillary Spatial Data: Soil maps and forest cover type maps [14].

- Variable Selection and Model Tuning: Employ a feature selection method (e.g., Recursive Feature Elimination) to reduce collinearity and identify the most predictive variables. The referenced study narrowed 67 variables down to 28. Perform hyperparameter tuning for the Random Forest algorithm to optimize model performance [14].

- Model Training and Prediction: Train the tuned Random Forest model using the field-measured AGB as the response variable and the selected remote sensing metrics as predictors. Apply the trained model to the entire study area to generate a spatially continuous AGB map at the resolution of the finest input data (e.g., 15m) [14].

- Model Validation and Comparison: Validate the model using a held-out portion of the field data or via cross-validation. Compare the results, in terms of both accuracy (RMSE, R²) and spatial pattern, with existing coarser-resolution AGB products like the global ESA CCI AGB map [14].

Figure 2: Workflow for integrated biomass prediction using machine learning.

Protocol 3: Biomass Supply Chain and Biofuel Potential Analysis

Objective: To determine the optimal geographical scale and methodology for collecting and utilizing residual biomass for biofuel production within a circular economy framework.

Workflow:

- Residual Biomass Inventory: Compile a geographic database of residual biomass sources. Key data includes:

- Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis: Perform spatial analysis to understand the distribution pattern of biomass resources. Use global and local indices (e.g., Moran's I, Geary's C, Getis' G) to identify significant spatial clusters (hotspots) and outliers [3]. This tests Tobler's First Law of Geography, which states that "near things are more related than distant things."

- Collection Strategy Optimization: Based on the spatial analysis, design a cost-effective collection strategy.

- For highly clustered resources like WCOs in urban and tourist areas, establish small autonomous collection units feeding into central processing plants [3].

- For widely dispersed and geographically fragmented resources like lignocellulosic biomass, deploy small mobile collection units that perform in-situ pre-processing (e.g., rapid pyrolysis in a tanker vehicle) to reduce transport costs [3].

- GIS-Based Siting: Use GIS overlay analysis with factors like proximity to roads, existing refineries, and population centers to identify optimal locations for collection points and processing facilities.

Data Access and Operational Tools

Successful implementation of these protocols requires efficient access to data and specialized tools.

- Data Portals: The primary source for all ESA CCI data products, including AGB, Land Cover, Soil Moisture, and Fire, is the ESA CCI Open Data Portal [15] [19] [17].

- Python Tools: The

esa_cci_smPython package facilitates reading and processing the daily soil moisture data in NetCDF format [17] [18]. - User Tools: The CCI-LC User Tool is specifically designed for climate modelers to subset, resample, and convert land cover classes into Plant Functional Types (PFTs) using default or custom conversion tables [16].

The synergy of ESA CCI's long-term, globally consistent geospatial data products provides an unparalleled foundation for advanced biomass assessment. By following the structured protocols outlined in this document—from fundamental AGB change detection to sophisticated multi-sensor machine learning modeling and spatial supply chain optimization—researchers can generate robust, high-resolution insights into carbon stocks and their dynamics. This structured approach, firmly grounded in GIS principles, is essential for supporting evidence-based climate policy and sustainable bioeconomy development.

Global Research Trends and Collaboration Networks in Biomass Spatial Analysis

Application Notes: Core Analytical Frameworks in Biomass Spatial Analysis

The utilization of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and spatial analysis for biomass assessment has become a critical methodology for advancing renewable energy strategies, carbon stock management, and circular economy models. The following structured data summarizes key quantitative findings and analytical frameworks from contemporary research, highlighting the diverse applications and significant potentials of biomass resources.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Findings from Global Biomass Spatial Analysis Studies

| Study Region/ Focus | Biomass Type | Estimated Quantity | Spatial Analysis Method | Primary Application/Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greece [3] | Waste Cooking Oils (WCOs) | 163.17 million L/year | Global & local spatial autocorrelation (Moran's I, Geary's C, Getis' G) | Green diesel production; Collection strategy optimization for urban/tourist areas |

| Greece [3] | Residual Lignocellulosic Biomass | 4.5 million tons/year | Spatial autocorrelation & geographic distribution analysis | Bio-oil via pyrolysis; Strategy of small mobile in-situ conversion units |

| Nigeria [21] | Crop & Forest Residues | Not Specified | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) & GIS mapping | Combined Heat and Power (CHP) generation (2911 MW net power) |

| United States [22] | National Forest Biomass | 34.71 billion tons (new NSVB estimate) | National Scale Volume and Biomass (NSVB) modeling system | Carbon accounting and greenhouse gas inventory reporting |

| Australia [23] | Woody Vegetation | Model R²: 0.74, RMSE: 49.79 Mg/ha | Stacking ensemble model with multi-source remote sensing | High-resolution aboveground biomass (AGB) carbon stock mapping |

The application of these spatial analytical frameworks reveals several key trends. First, the move beyond simple resource quantification to the optimization of logistics and supply chains is evident, as demonstrated in Greece, where spatial autocorrelation directly informed cost-effective collection strategies for dispersed biomass resources [3]. Second, the integration of GIS with Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) is pivotal for site selection, ensuring that biomass plants are strategically located based on resource availability, economic viability, and environmental sustainability, a approach successfully applied in Nigeria and Australia [24] [21]. Finally, a major trend is the shift from regional to nationally consistent and high-resolution biomass assessment frameworks. The U.S. Forest Service's NSVB system, for instance, replaces older, inconsistent regional models with a unified national framework, increasing the national aboveground biomass estimate by 14.6% and enabling more accurate carbon policy and climate reporting [22].

Experimental Protocols in Biomass Spatial Analysis

Protocol: GIS-Based Site Suitability and Supply Chain Optimization for Biomass Energy Plants

This protocol outlines a spatially explicit framework for identifying optimal locations and configurations for biomass energy plants, integrating resource assessment, logistics, and economic factors [24] [21].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for GIS-Based Biomass Analysis

| Item/Tool | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| ArcGIS Software Suite | A proprietary GIS platform for spatial data management, analysis, and visualization. | Used for all core spatial operations, including network analysis, weighted overlay, and map production [24] [21]. |

| QGIS & GeoDA | Open-source GIS and spatial analysis software. | Provides an alternative for spatial autocorrelation analysis (e.g., Moran's I) and general GIS tasks, improving accessibility [3]. |

| R Programming Language | A language and environment for statistical computing and graphics. | Used for advanced statistical analysis, calculating spatial autocorrelation indices, and running machine learning models [3] [23]. |

| Remote Sensing Data (Landsat, GEDI) | Satellite imagery and derived products (e.g., NDVI, canopy height, biomass density). | Serves as key explanatory variables for modeling biomass distribution and land cover classification [25] [23]. |

| Digital Elevation Model (DEM) | A digital representation of topographic elevation. | Used to derive slope and aspect, which are critical criteria for suitability analysis and logistics planning [25] [21]. |

| Near-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy (NIRS) | A rapid, non-destructive technique for determining chemical constituents in biomass samples. | Used for analyzing forage quality metrics (e.g., crude protein, lignin) to assess biomass suitability for various applications [26]. |

Methodology

Data Acquisition and Preparation:

- Biomass Resource Data: Compile spatially explicit data on biomass availability (e.g., agricultural residues, forest waste, used cooking oils). Sources can include government statistics, industry reports, field surveys, and remote sensing products [3] [24]. Data should be georeferenced to administrative units or specific point locations.

- Explanatory Variables: Gather GIS layers for relevant factors. These typically include:

- Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI): Calculate NDVI from satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat) using the formula

NDVI = (NIR - Red) / (NIR + Red)to assess vegetation density and health, which correlates with biomass [21] [23].

Suitability Analysis via Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA):

- Reclassification: Standardize all GIS layers (criteria) to a common suitability scale (e.g., 1-9, with 9 being most suitable).

- Weight Assignment: Assign influence weights to each criterion based on expert judgment or analytical methods (e.g., Analytical Hierarchy Process). Weights must sum to 100%.

- Weighted Overlay: Use the Weighted Overlay tool in ArcGIS (or equivalent) to combine all reclassified layers according to their weights, generating a composite suitability map for plant locations [21].

Supply Chain Logistics Optimization:

- Network Analysis: Using the road network layer, perform a Location-Allocation analysis. The objective is to minimize the total weighted transportation cost from biomass source locations to potential plant sites identified in the suitability map [24].

- Model Application: Solve the problem using a solver like the

p-medianproblem to select the optimal number and location of plants that minimize total transport distance [24].

Validation and Uncertainty Analysis:

- Model Validation: Use

K-fold cross-validationto assess the predictive performance of the models, reporting R² and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values [23]. - Uncertainty Quantification: Employ methods like

Monte Carlo simulationto evaluate the uncertainty associated with biomass estimates and model parameters [23].

- Model Validation: Use

Protocol: Aboveground Biomass Estimation Using Multi-Source Remote Sensing and Ensemble Learning

This protocol details the process for creating large-scale, high-resolution aboveground biomass (AGB) maps by integrating field measurements with satellite data through advanced machine learning, as demonstrated in recent Australian research [23].

Methodology

Field Data Collection and Preparation:

- Plot Establishment: Establish representative sample plots (e.g., 30m x 30m) for the target vegetation types [27].

- Tree Census: Record species, Diameter at Breast Height (DBH), and height for all trees within the plot meeting a minimum DBH threshold (e.g., >1 cm) [27].

- Biomass Calculation: Calculate AGB for each tree using species-specific or generalized allometric equations. Aggregate to plot-level biomass density (Mg/ha) [23] [22].

- Data Screening: Remove outliers and plots with excessive error, and ensure a robust dataset that includes non-woody (zero-biomass) plots to prevent overestimation [23].

Predictor Variable Extraction from Remote Sensing:

- Lidar-derived Metrics: Extract vegetation height metrics from products like GEDI L4A (for AGBD samples) or other canopy height models [25] [23].

- Optical Satellite Imagery: Calculate spectral indices (e.g., NDVI, RVI) from platforms like Landsat [23].

- Topographic & Climate Data: Extract slope, aspect from DEMs, and incorporate climate variables like precipitation [23].

Model Training and Evaluation with Stacking Ensemble:

- Feature Selection: Use Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) to select the most important predictor variables, improving model efficiency and performance [23].

- Base and Meta-Learner Configuration:

- Base Learners: Train multiple diverse models (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, Support Vector Machines).

- Meta-Learner: Use a linear model (e.g., Linear Regression) to learn how to best combine the predictions from the base models.

- Model Validation: Perform

K-fold cross-validationon the entire stacking process. Compare the Stacking model's performance (R², RMSE) against individual models [23].

Biomass Mapping and Uncertainty Assessment:

- Spatial Prediction: Apply the trained Stacking model to the full set of predictor rasters to generate a continuous AGB map for the entire study area.

- Uncertainty Analysis: Use

Monte Carlo simulationto propagate errors and quantify uncertainty in the final biomass map [23].

Emerging Collaboration Networks and Data Integration Frameworks

A prominent trend in biomass spatial analysis is the formation of large-scale, open-access data consortiums that foster interdisciplinary collaboration. The Australian Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network (TERN) provides a prime example, integrating tree inventory data from federal and state governments, academia, and private industry into a unified biomass plot database for calibrating national-scale satellite products [23]. Similarly, the U.S. Forest Service's FIA program exemplifies long-term, nationally consistent monitoring, with its new NSVB model relying on a massive dataset of over 232,000 destructively sampled trees contributed by diverse stakeholders [22]. These networks are crucial for validating the remote sensing-based approaches described in the protocols.

The integration of multi-source data is now a methodological standard. Research consistently demonstrates that combining datasets—such as satellite lidar (GEDI) for structural information, optical imagery (Landsat) for spectral characteristics, and topographic data—effectively addresses the limitations of any single source and leads to more robust AGB estimates [25] [23]. This synergy between open data networks and advanced, integrated modeling frameworks is accelerating the development of accurate, high-resolution biomass maps, which are indispensable for global carbon accounting, climate change mitigation policies, and sustainable bioenergy planning.

From Data to Decisions: GIS Methodologies for Biomass Assessment and Facility Siting

GIS-Based Biomass Potential Assessment at High Spatial Resolution

High-resolution spatial assessment of biomass resources is a critical prerequisite for viable bioenergy development, enabling policymakers and industry developers to make strategic decisions regarding plant siting, logistics planning, and supply chain optimization [28] [29]. These assessments quantify the existing or potential biomass materials in a given area, which can include agricultural residues, dedicated energy crops, forestry products, animal wastes, and post-consumer residues [28]. The application of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) provides powerful spatial analytical and optimization capabilities for this purpose, allowing researchers to process spatial data on various socio-economic and environmental elements while optimizing biomass supply logistics under real-world scenarios [29]. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for conducting high-resolution biomass potential assessments, providing researchers with standardized methodologies for spatial biomass evaluation.

Data Acquisition and Preparation Protocols

Essential Spatial Datasets

The foundation of any high-resolution biomass assessment lies in the acquisition and processing of reliable spatial datasets. The table below summarizes the core data requirements and their specific applications in biomass potential calculations.

Table 1: Essential Spatial Datasets for High-Resolution Biomass Assessment

| Data Category | Specific Datasets | Spatial Resolution | Application in Biomass Assessment | Exemplary Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land Use/Land Cover | Land use maps, NDVI from Sentinel-2 | 10-30 m | Identify biomass source areas (crop, forest, grassland); exclude protected areas | Resource and Environment Science and Data Centre [30], Sentinel-2 SR [31] |

| Topography | Digital Elevation Model (SRTM) | 30 m | Calculate slope; exclude areas >25° for energy crops [30]; analyze transport accessibility | Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) [31] |

| Agricultural Statistics | Crop production yields, residue coefficients | Administrative units | Calculate agricultural residue potential; spatial allocation using proxies | National statistical offices, ELSTAT [3] |

| Climate/Vegetation | Net Primary Production (NPP), Rainfall data | 250-5000 m | Spatial proxy for statistical allocation; rainfall erosivity assessment [30] | MODIS [31], CHIRPS [31] |

| Protected Areas | Natural reserves, biodiversity zones | Variable | Exclude protected lands from energy crop cultivation [30] | Government databases [30] |

Data Pre-processing Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the sequential workflow for data acquisition and pre-processing, which establishes the foundation for all subsequent analysis:

Marginal Land Identification Protocol: For assessing energy crop potential, follow this standardized procedure: First, select grids based on land use types including shrub land, sparse land, various grassland types, and unused lands. Second, exclude grid cells falling within natural reserves, slopes exceeding 25 degrees, and critical pasture areas to ensure compliance with environmental protection principles [30]. This approach resolves conflicts between energy crop plantation, food security, and environmental pressures by focusing on areas with low agricultural productivity that are susceptible to degradation.

Biomass Assessment Methodologies

Biomass Potential Calculation Framework

The core of biomass assessment involves calculating theoretical, technical, and economic potentials using standardized formulas and region-specific parameters. The table below summarizes key findings from regional assessments conducted using these methodologies.

Table 2: Biomass Potential Estimates from Regional Case Studies

| Region | Biomass Types Assessed | Theoretical Potential | Technical Potential | Economic Potential | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Queensland, Australia [32] | Sugarcane, cotton, crops, manure, food waste | 19 Mt DM annually | 109 PJ/yr biomethane | 69 PJ/yr within 100 km of gas grid | 1 km² |

| Greece [3] | Used cooking oils, lignocellulosic biomass | 163.17 million L/year (WCO), 4.5 million tons/year (lignocellulosic) | Not specified | Varies by collection method | Municipalities |

| Nigeria [8] | Crop residues, forest residues | 1,163.32 PJ/yr (N.E. crops), 260.18 PJ/yr (N.W. forests) | 399.73 PJ/yr (crops), 156.11 PJ/yr (forests) | 110.56 PJ/yr (crops), 43.18 PJ/yr (forests) | Regional |

| China [30] | 9 agricultural residues, 11 forestry residues, 5 energy crops | Comprehensive national assessment | Techno-economic analysis under constraints | Multiple utilization scenarios | 1 km² |

Agricultural Residue Assessment Protocol:

- Data Collection: Gather crop production statistics for all major crops at the highest available administrative resolution (provincial, district, or municipal levels).

- Residue Coefficient Application: Multiply crop production data by crop-specific residue-to-product ratios (RPR) obtained from published literature or field measurements.

Spatial Allocation: Distribute statistical residue data geographically using spatial proxies such as Net Primary Production (NPP) data or crop-specific maps [30]. The general formula for agricultural residue potential is:

( ARP = \sum (Crop Productioni \times RPRi) )

Where ( ARP ) is Agricultural Residue Potential and ( RPR_i ) is the Residue-to-Product Ratio for crop i.

Livestock Waste Assessment Protocol:

- Population Data Collection: Compile livestock population statistics (cattle, pigs, poultry, etc.) from agricultural censuses.

- Waste Coefficient Application: Apply species-specific waste production coefficients (kg/animal/day) to calculate total manure availability.

- Methane Potential Calculation: Estimate biomethane potential using volatile solids content and methane yield parameters specific to each livestock type [29]. Note that mono-digestion of manure is often economically challenging due to low methane yields (typically 10-20 m³ methane/m³ of digested slurry), making co-digestion with higher-yield co-substrates necessary for viability [29].

Spatial Analysis Techniques

The application of spatial analysis techniques transforms raw biomass data into actionable intelligence for decision-making. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for spatial biomass assessment:

Spatial Autocorrelation Protocol:

- Global Indicator Calculation: Compute global spatial autocorrelation indices (Moran's I, Geary's C) to determine if biomass resources exhibit clustering, dispersion, or random patterns across the study area.

- Local Indicator Analysis: Apply local indicators of spatial association (LISA) to identify specific clusters of high-value (hot spots) and low-value (cold spots) biomass concentrations [3].

- Spatial Regimes Definition: Based on autocorrelation results, define spatial regimes for tailored collection strategies. For widely dispersed resources like lignocellulosic biomass in Greece, implement small mobile collection units, while concentrated resources like waste cooking oils in urban areas justify centralized processing plants [3].

Grid-Based Assessment Protocol:

- Study Area Rasterization: Divide the study area into a consistent grid (e.g., 1km² cells) using GIS software.

- Biomass Allocation: Allocate biomass potential to each grid cell based on underlying land use, crop distribution, and other spatial parameters.

- Aggregation Analysis: Analyze biomass potential within specified distances from infrastructure (e.g., 20, 50, 100 km from gas grids) to determine economically viable resources [32]. The Queensland study demonstrated this approach, finding that biomethane production potentials within these distances were 17, 40, and 69 PJ/yr respectively [32].

Biomethane Production and Grid Injection Assessment

For assessments focused on biogas and biomethane production, additional specialized protocols are required to evaluate the feasibility of grid injection and decarbonization of natural gas infrastructure.

Biomethane Potential Assessment Protocol:

- Feedstock Characterization: Analyze the carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio of biomass mixtures, with optimal anaerobic digestion typically occurring at C/N ratios between 20:1 and 30:1 [32]. The Queensland study reported an overall C/N ratio of 53:1 for total biomass, suggesting potential need for feedstock blending [32].

- Methane Yield Calculation: Apply feedstock-specific methane yield coefficients (m³ CH₄/ton volatile solids) to calculate biomethane potential.

- Grid Proximity Analysis: Calculate total biomethane potential within economically viable distances (e.g., 20-100 km) from existing gas grid infrastructure [32] [29].

- Decarbonization Potential: Compare biomethane potential with current natural gas consumption to determine replacement potential. The Queensland assessment concluded that 73% of the state's local gas consumption could be met with biomethane using existing biomass resources [32].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Analytical Tools

The table below catalogues essential software tools and analytical components required for implementing high-resolution GIS-based biomass assessments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GIS-Based Biomass Assessment

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Function in Biomass Assessment | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| GIS Software | ArcGIS (10.8.2, 10.2.2) [32] [31] | Spatial data processing, analysis, and map production | Queensland biomass assessment at 1km² resolution [32] |

| Open-Source GIS | QGIS (3.40) [3], GeoDA (1.22) [3] | Free alternative for spatial analysis and autocorrelation | Spatial autocorrelation of Greek biomass resources [3] |

| Cloud Computing Platforms | Google Earth Engine [31] | Processing large-scale geospatial data in the cloud | Soil erosion assessment for biomass sustainability [31] |

| Statistical Software | R Programming (4.4.1) [3] | Statistical analysis and spatial autocorrelation calculations | Calculating Moran's I and Getis' G indices [3] |

| Spatial Analysis Tools | Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) [8] [31] | Multicriteria decision analysis for site suitability | Biomass plant siting in Nigeria [8] |

| Resource Assessment Tools | NREL BioFuels Atlas [33] | Geospatial analysis of biomass resources and biofuels production | U.S. biomass resource assessment [33] |

High-resolution GIS-based biomass assessment provides an essential foundation for sustainable bioenergy development and natural gas grid decarbonization. The protocols outlined herein enable researchers to accurately quantify biomass resources while considering critical sustainability constraints and economic realities. The integration of spatial analysis techniques, particularly spatial autocorrelation and multicriteria decision analysis, transforms raw biomass data into actionable intelligence for optimal plant siting and supply chain design. Future methodological developments should focus on enhancing the temporal dimension of assessments, integrating dynamic biomass availability factors, and improving the optimization of entire supply chains rather than individual components. Standardization of these methodologies across regions will facilitate more accurate comparative analyses and support global efforts to transition toward renewable energy systems through informed biomass resource utilization.

Suitability Analysis and Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) for Optimal Plant Location

Suitability analysis supported by Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) provides a structured framework for identifying optimal locations for industrial plants, particularly within the biomass and renewable energy sectors. The integration of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) with MCDM methodologies enables researchers and planners to systematically evaluate diverse geographical, economic, and environmental factors, transforming complex spatial decision problems into transparent, reproducible processes [34] [35]. This approach is especially valuable for biomass facility siting, where optimal location is critical for economic viability, environmental sustainability, and community integration [36] [37].

The fundamental premise of GIS-based suitability analysis posits that every landscape possesses inherent characteristics that render it either suitable or unsuitable for specific activities [35]. By applying MCDM techniques, decision-makers can quantify these characteristics, weigh their relative importance, and synthesize them into comprehensive suitability maps that visually communicate optimal locations for development [34] [38]. This protocol details the application of these integrated methodologies for biomass plant location within the broader context of GIS for biomass spatial analysis research.

Foundational Methodologies and Weighting Approaches

Multiple MCDM methodologies can be integrated with GIS for suitability analysis, each with distinct strengths and applications. The Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) is particularly dominant in bioenergy and biomass sectors, using pairwise comparisons to derive criterion weights based on expert judgment [34] [38]. AHP employs a consistency ratio (CR) to validate the coherence of expert judgments, enhancing methodological rigor [39]. For problems involving significant uncertainty or imprecise expert judgments, the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP) incorporates fuzzy logic to handle linguistic variables and quantitative uncertainties [35] [40]. The Weighted Linear Combination (WLC) method offers a straightforward analytical approach for combining standardized criteria values, frequently applied alongside AHP [38].

Table 1: Comparison of MCDM Weighting Methods for GIS-Based Suitability Analysis

| Method | Key Characteristics | Best Application Context | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHP | Pairwise comparisons; consistency ratio validation; expert-driven weights | Scenarios with reliable expert availability and clear criteria [34] [39] | Structured judgment; consistency validation; intuitive process [39] | Subjective bias potential; limited uncertainty handling [34] |

| FAHP | Fuzzy membership functions; handles linguistic variables; accommodates uncertainty | Problems with imprecise data or expert judgments [35] [40] | Manages ambiguity; more robust with uncertainty [40] | Computationally intensive; technically complex [39] |

| WLC | Linear additive weighting; simple weighted sum; predefined weights | Straightforward problems with well-understood criterion importance [38] | Computational simplicity; easy implementation [38] | No inherent consistency checking; oversimplification risk [38] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: GIS-AHP Suitability Analysis for Community-Scale Biomass Power Plants

This protocol adapts methodologies from Thailand's Eastern Economic Corridor study, which identified optimal sites for community-scale biomass power plants (CSBPPs) using GIS-MCDM with AHP [34].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GIS Software | ArcGIS Pro (v3.0.2+) or QGIS with processing toolbox; Spatial Analyst extension | Primary platform for spatial data management, analysis, and visualization [34] [41] |

| Remote Sensing Data | Landsat 8/9 imagery (30 m resolution); Sentinel-2 (10 m resolution); DEM data (10-30 m resolution) | Land use/land cover classification; topographic analysis [41] [39] |

| AHP Computational Tool | Expert Choice desktop software; R 'ahp' package; Python 'pyAHP' library | Facilitates pairwise comparison matrix calculations and consistency validation [34] |

| Spatial Data Layers | Road networks; river systems; settlement areas; protected areas; biomass availability maps | Core criteria for suitability analysis [34] [41] |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Objective Definition and Study Area Delineation: Clearly define the biomass plant siting objectives within sustainability and technical constraints. Select the geographic boundary and acquire administrative boundary files [34] [38].

Spatial Data Collection and Preparation: Gather relevant spatial datasets, including:

- Topographic Data: Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) for slope derivation (e.g., 30 m resolution SRTM or ALOS) [36]

- Land Use/Land Cover (LULC): Recent classified satellite imagery (e.g., Landsat 8/9) [36] [39]

- Infrastructure Data: Road networks, power lines, and water bodies from national mapping agencies [34] [41]

- Biomass Resources: Spatial distribution of agricultural/forest residues from government statistics or remote sensing [34] [37]

- Environmental Constraints: Protected areas, ecological zones, and water resources [38]

Criteria Standardization: Convert all vector data to a common raster grid (e.g., 100 m resolution). Reclassify values to a uniform suitability scale (1-9 or 0-1) using linear transformation or fuzzy membership functions [34] [35].

AHP Weighting Process:

- Develop a hierarchical structure with goal, criteria, and sub-criteria levels [38]

- Conduct pairwise comparisons with domain experts using Saaty's 1-9 scale

- Compute criterion weights and validate consistency (Consistency Ratio < 0.1) [39]

- Example: Gambella region study assigned these weights: LULC (46.58%), solar radiation (20.42%), slope (15.52%), proximity to roads (8.26%), proximity to rivers (5.46%), proximity to towns (3.77%) [36]

Weighted Overlay Analysis: Implement the weighted linear combination in GIS using the raster calculator or weighted overlay tool:

Suitability Index = Σ(Weight_i × StandardizedCriterion_i)Suitability Classification and Validation: Classify output suitability index into categories (e.g., highly suitable, moderately suitable, unsuitable). Ground-truth potential sites through field verification and sensitivity analysis [34] [38].

Protocol 2: GIS-FAHP for Sustainable Fuel Production Facilities

This protocol implements the Fuzzy AHP approach for locating advanced biofuel facilities (BtX, PtX), addressing uncertainties in criterion measurement and expert judgment [35].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Fuzzy Logic Toolbox: MATLAB Fuzzy Logic Toolbox; Python 'scikit-fuzzy' package; R 'FuzzyAHP' package

- High-Resolution Spatial Data: Sentinel-2 (10 m); LiDAR derivatives (1-5 m DEM); specialized biomass mapping datasets

- Climate Data Resources: Solar radiation databases (NASA POWER); wind atlases; precipitation and temperature grids

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define Fuzzy Membership Functions: Select appropriate fuzzy membership functions (triangular, trapezoidal) for each criterion based on data characteristics and expert knowledge [35] [40].

Fuzzy Pairwise Comparisons: Experts provide fuzzy comparison matrices using linguistic terms (equally important, moderately more important, strongly more important) represented as fuzzy numbers [35].

Calculate Fuzzy Weights: Process fuzzy comparison matrices to derive fuzzy weights for each criterion using the extent analysis method or fuzzy linear programming approaches [35].

Defuzzification: Convert fuzzy weights to crisp values using Center of Area, Mean of Maximum, or other defuzzification methods suitable for the problem context [35].

Exclusion Analysis: Identify and mask out entirely unsuitable areas based on constraint criteria (protected areas, steep slopes >30%, urban centers, water bodies) [35] [39].

Final Suitability Mapping: Combine weighted criteria with exclusion masks to generate final suitability maps highlighting optimal locations on a 0-9 suitability scale [35].

Application Notes and Data Analysis

Criteria Selection and Weighting

Effective suitability analysis requires careful selection of criteria relevant to biomass facility siting. Studies consistently emphasize several key categories:

Table 3: Representative Criteria and Weights from Biomass Plant Siting Studies

| Criterion Category | Specific Criteria | Representative Weight | Study Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedstock Availability | Biomass residue density; Crop type distribution; Forest residue availability | 20-30% (often highest weighted) | Thailand EEC [34]; Nigeria [41] |

| Infrastructure & Access | Proximity to roads; Distance to grid connection; Site access | 15-25% | Gambella, Ethiopia [36]; Jordan [39] |

| Topographic Factors | Slope; Aspect; Elevation | 10-20% | Spain [38]; Turkey [42] |

| Environmental Considerations | Land use/land cover; Protected areas; Water body proximity | 15-25% | China [37]; Jordan [39] |

| Socio-Economic Factors | Proximity to settlements; Labor availability; Potential demand | 5-15% | Thailand [34]; Spain [38] |

Sensitivity Analysis and Validation

Robust suitability analysis requires sensitivity analysis to test output stability against variations in input weights and data uncertainties [38]. Implement one-at-a-time (OAT) sensitivity analysis by systematically varying criterion weights (±5-10%) and observing impacts on suitability classifications [38]. Validate results through comparison with existing facility locations, ground truthing of highly suitable areas, and stakeholder feedback [34] [39].

The integration of GIS with MCDM methodologies provides a powerful, replicable framework for optimal plant location analysis in biomass spatial research. The protocols detailed herein enable researchers to systematically evaluate complex spatial decision problems, incorporate expert knowledge through structured weighting processes, and generate transparent, defensible suitability maps. These methodologies support sustainable spatial planning and contribute to the development of efficient biomass supply chains, aligning with global sustainability goals and advancing renewable energy infrastructure development.

Integrating the Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP) for Complex Decision-Making

Application Note: Enhancing GIS-Based Biomass Facility Siting with FAHP

The integration of Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process (FAHP) with Geographic Information Systems (GIS) represents a methodological advancement for addressing complex spatial decision-making problems in biomass research. This approach is particularly valuable for site selection of biomass-to-liquid (BtL), power-to-liquid (PtL), and hybrid sustainable fuel production facilities, where decision-making involves multiple, often conflicting criteria with inherent uncertainties [43] [35]. FAHP enhances traditional AHP by incorporating fuzzy set theory to handle the imprecision and subjectivity inherent in expert judgments, providing a more robust framework for weighting criteria in spatial analysis [35] [44].

The core innovation lies in combining GIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) with fuzzy logic to manage the linguistic uncertainties and vague spatial relationships common in biomass resource assessment [35]. This integration allows researchers to systematically evaluate location suitability based on quantitative spatial data while accounting for the qualitative nature of decision-making preferences, ultimately generating more reliable suitability maps for biomass facility placement [43] [35].

Key Advantages for Biomass Spatial Analysis

- Handling Spatial Uncertainty: FAHP effectively manages uncertainties in biomass potential mapping, where resource distribution often exhibits geographical fragmentation and heterogeneity [35] [3]

- Expert Judgment Quantification: The method transforms subjective expert preferences into quantifiable weights using fuzzy pairwise comparison matrices, reducing bias in criteria weighting [35]

- Resource Optimization: For biomass resources with high collection and transportation costs, FAHP-driven site selection minimizes logistical challenges by identifying optimal locations [3]