Overcoming Biomass Logistics and Storage Challenges: A Strategic Guide for Sustainable Supply Chains

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the complex challenges in biomass logistics and storage, offering actionable strategies for researchers and scientists.

Overcoming Biomass Logistics and Storage Challenges: A Strategic Guide for Sustainable Supply Chains

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the complex challenges in biomass logistics and storage, offering actionable strategies for researchers and scientists. It explores the foundational bottlenecks of feedstock variability and supply chain inefficiencies, details cutting-edge methodological advances in AI optimization and densification technologies, and presents robust frameworks for troubleshooting operational hurdles. With a focus on validation, it further examines protocols for ensuring sustainability, economic viability, and compliance with global standards, serving as an essential resource for professionals dedicated to building resilient and scalable biomass supply chains for a sustainable bioeconomy.

Understanding the Core Bottlenecks in Biomass Supply Chains

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary biomass storage methods and how do they impact downstream processing? The two primary methods are dry storage (e.g., baling) and anaerobic wet storage (ensilage). Dry storage risks significant dry matter loss (7.4-22.0%) and microbial degradation if moisture is present, while proper ensilage can minimize dry matter loss to 0.2-0.9% [1]. Furthermore, ensilage produces organic acids that lower pH, which may reduce acid requirements in subsequent pretreatment processes and decrease biomass recalcitrance through partial hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose [1].

Q2: What specific safety hazards are associated with storing and handling biomass? Key hazards include combustible dust from processed biomass (e.g., wood chips, pellets), which can pose explosion risks [2]. Off-gassing of toxic and flammable gases like methane and hydrogen sulfide occurs during organic decomposition [2]. Biomass piles are also prone to self-heating, which can lead to spontaneous combustion [3].

Q3: How do biomass harvesting practices affect ecological sustainability? Increased removal of forest residuals for biomass can impact site nutrients, reduce wildlife habitat, and decrease ground cover, potentially increasing erosion and impairing water quality [4]. To mitigate this, Biomass Harvesting Guidelines (BHGs) often recommend retaining a portion of residual material (e.g., 33%) on-site post-harvest to protect biodiversity and soil/water resources [4].

Q4: What are the major economic bottlenecks in scaling up biomass logistics? The low energy density and high moisture content of raw biomass lead to high harvesting and transportation costs per unit of energy [5] [4]. The capital investment required for processing machinery (chippers, grinders) is significant, and operations focused solely on residue removal are often only profitable when integrated with conventional harvesting [4]. Furthermore, the economic viability is sensitive to volatile fossil fuel prices and often depends on government subsidies and policy incentives [5].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental & Operational Challenges

Problem 1: High Dry Matter Loss During Biomass Storage

- Symptoms: Noticeable decrease in solid mass after storage; presence of mold; increased temperature in storage piles.

- Root Cause: Aerobic microbial activity due to insufficient anaerobic conditions or moisture ingress [1] [3].

- Solutions:

- Switch to Anaerobic Storage: Implement ensilage techniques by compacting biomass and using oxygen-barrier tarps or silos to create an anaerobic environment [1].

- Monitor Moisture Content: For dry storage, ensure biomass is adequately field-dried before baling and protect bales from rain and humidity [1].

- Use Silage Inoculants: Apply microbial inoculants to dominate the fermentation process, rapidly lowering pH and preserving carbohydrates [1].

Problem 2: Combustible Dust Accumulation

- Symptoms: Visible layers of fine dust on surfaces; dust clouds generated during material handling.

- Root Cause: Grinding and handling of dry biomass generates fine, explosive dust [2].

- Solutions:

- Implement a Dust Hazard Analysis (DHA): As required by standards like NFPA 652, conduct a DHA to identify and assess risks [2].

- Install Engineering Controls: Use dust collection systems, local exhaust ventilation, and explosion venting equipment [2].

- Enforce Rigorous Housekeeping: Establish regular cleaning schedules to prevent dust accumulation using methods that do not generate sparks [2].

Problem 3: Inconsistent Analytical Results from Stored Biomass

- Symptoms: High variability in measurements of fiber content (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) and Water Soluble Carbohydrates (WSC) between samples.

- Root Cause: Inconsistent pre-analytical sample preparation, including particle size and pre-storage handling [1].

- Solutions:

- Standardize Particle Size: For laboratory ensilage studies, use a medium particle size (<10 mm) to ensure representative and homogenous samples [1].

- Use Fresh or Properly Preserved Biomass: For the most accurate results, use freshly harvested biomass. If storage is necessary, freezing is preferable to drying or refrigeration, as it preserves characteristics closer to fresh material [1].

- Employ Validated Analytical Methods: Use the modified phenol-sulfuric method for WSC analysis, as it provides appropriate results and better resolution [1].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Laboratory-Scale Ensilage for Storage Stability Studies

This protocol evaluates the efficacy of ensilage as a storage method for lignocellulosic biomass, based on established research methods [1].

- Objective: To assess the impact of different pre-storage conditions and ensilage on biomass quality and preservability.

- Materials:

- Biomass Sample: Corn stover (stalks, leaves, husks).

- Reactor Vessels: 1-L wide-mouth mason jars or similar airtight containers.

- Equipment: Oven, balance, mill/grinder, pH meter.

- Procedure:

- Harvest and Pre-treatment: Harvest biomass and immediately determine initial moisture content by oven-drying a representative sample at 105°C until constant weight [1].

- Experimental Treatment Groups:

- Group A (Fresh): Ensile freshly harvested biomass immediately.

- Group B (Frozen): Freeze biomass, then thaw and adjust moisture before ensiling.

- Group C (Dried): Air-dry biomass, then remoisten to target moisture before ensiling.

- Ensilage: Grind biomass to a particle size of <10 mm. Load into reactor vessels, compact to expel air, and seal anaerobically. Incubate at room temperature (e.g., 25-30°C) for a set period (e.g., 30-60 days) [1].

- Post-Ensilage Analysis:

- Measure final pH.

- Analyze for fiber content (e.g., using Van Soest method) and Water Soluble Carbohydrates (WSC).

- Assess dry matter loss.

Protocol 2: Supply Chain Configuration Analysis for Scalability

This methodology assesses the economic and logistical feasibility of different biomass supply chain models.

- Objective: To compare the cost structures and efficiency of centralized versus decentralized (regional) biomass pre-processing.

- Materials: GIS software, logistics and cost modeling software, regional biomass production data.

- Procedure:

- Define System Boundaries: Map the entire supply chain from harvest to conversion facility, including transport, storage, and pre-processing (e.g., chipping, torrefaction, pelletizing) [5] [4].

- Model Centralized System: Model a system where raw biomass is transported long distances to a large, centralized processing plant. Key metrics to calculate include:

- Transportation cost per ton-mile.

- Total energy input for transport.

- Dry matter losses during transit and storage.

- Model Decentralized System: Model a system with smaller, distributed regional pre-processing centers that convert raw biomass into higher-density intermediates (e.g., wood pellets, torrefied biomass). Calculate the same metrics, adding the capital and operating costs of the pre-processing centers [5] [4].

- Comparative Analysis: Compare the total delivered cost per unit of energy (e.g., $/GJ) for both models. Perform a sensitivity analysis on key variables like fuel prices, transportation distance, and feedstock availability.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Biomass Storage Methods and Impacts

| Storage Method | Dry Matter Loss | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages | Impact on Downstream Processing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Storage (Baling) | 7.4 - 22.0% (if moist) [1] | Lower weight for transport, simple technology | High loss if not dry; fire risk; pore collapse increases recalcitrance [1] | Potential for reduced sugar yield due to increased recalcitrance |

| Anaerobic Ensilage | 0.2 - 0.9% [1] | Low dry matter loss; produces preservative acids; may reduce pretreatment acid need [1] | Requires anaerobic conditions; management intensive | Partial hydrolysis during storage may decrease biomass recalcitrance [1] |

Table 2: Scalability Analysis of Supply Chain Configurations

| Configuration | Description | Typical Transport Distance | Cost Drivers | Scalability Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centralized Processing | Raw biomass transported to large, single plant | Long-haul (>100 km) [5] | High transportation cost; significant dry matter loss [5] [4] | Feedstock geographic limitation; high transport emissions; infrastructure strain |

| Decentralized Pre-processing | Distributed hubs create energy-dense intermediates (pellets) | Shorter to hub; long-haul for intermediate [4] | High capital cost for multiple hubs; pre-processing energy input [5] | Requires significant upfront investment; coordination of complex network |

Visualizations

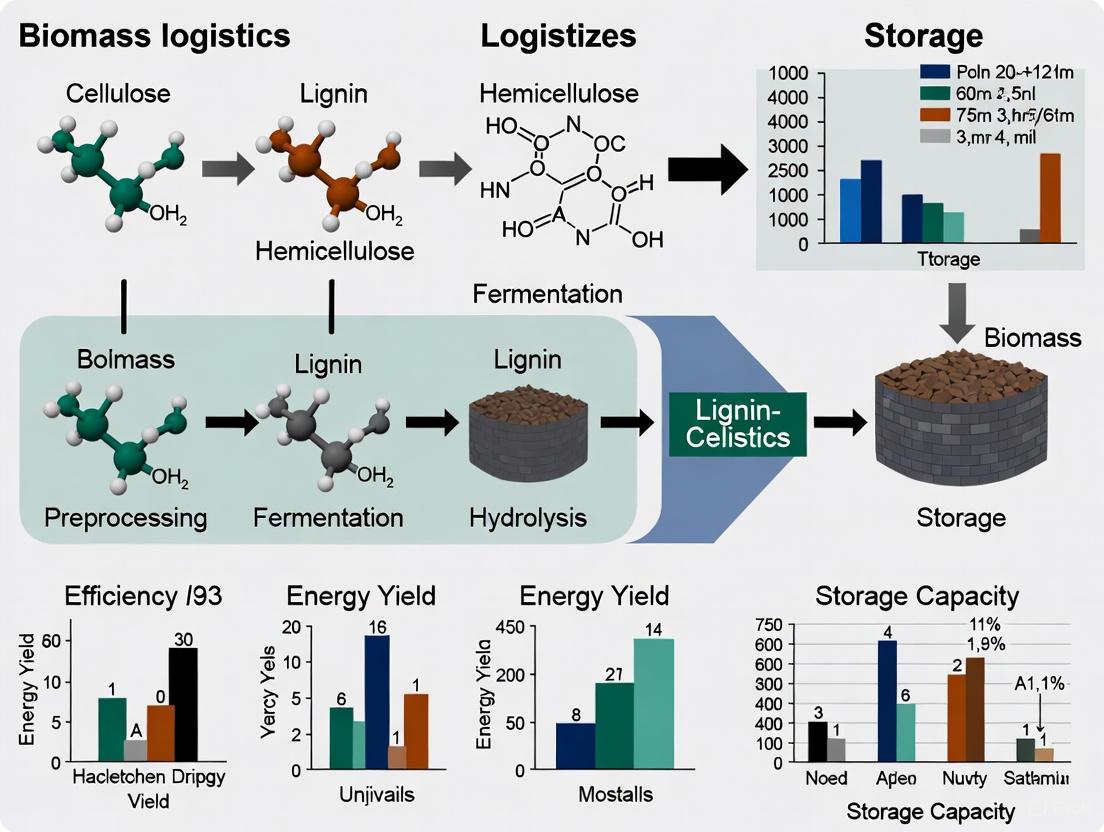

Diagram 1: Biomass Logistics Scalability Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Laboratory Ensilage Experimental Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Biomass Logistics Research | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Microbial Silage Inoculants | Dominates fermentation in ensilage, rapidly acidifying the environment to preserve biomass quality [1]. | Used in laboratory and pilot-scale ensilage experiments to study controlled storage and reduce dry matter loss. |

| Supplemental Enzymes (e.g., Cellulase, Xylanase) | Acts as a biocatalyst during storage to partially hydrolyze structural polysaccharides, potentially reducing biomass recalcitrance for downstream processing [1]. | Investigated as a pre-treatment additive during ensilage to improve subsequent sugar release. |

| Torrefaction Reactor | Thermochemically converts biomass into a coal-like, energy-dense material with improved hydrophobicity and grindability [6]. | Used in pre-processing research to mitigate challenges associated with low bulk density and biodegradability during storage and transport. |

| Dust Hazard Analysis (DHA) Tools | Identifies and assesses explosion risks from combustible dust generated during biomass processing [2]. | Critical for ensuring safety in pilot plants and scaling operations where biomass is handled in powdered or fine particulate form. |

The diagram below illustrates the interconnected nature of the three core challenges—variability, seasonality, and degradation—and their collective impact on research outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Feedstock Variability

Q1: How can we maintain consistent experimental results when our biomass feedstock comes from different sources (e.g., agricultural residues, municipal solid waste)?

Variability in biomass composition is a primary source of experimental inconsistency. Different feedstocks have varying proportions of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, as well as differing micro-element content (such as Potassium, Calcium, and Magnesium), which directly impacts conversion efficiency and product yields [7].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Characterize Incoming Feedstock: Implement a mandatory protocol for proximate and ultimate analysis for every batch received. Measure moisture, ash, volatile matter, fixed carbon, and elemental composition.

- Implement Blending: Create a homogenized feedstock blend by mixing different biomass types to achieve a consistent average composition. This can mitigate the extremes of any single source [7].

- Adapt Processes: Correlate your key process parameters (e.g., pyrolysis temperature, pretreatment severity) with feedstock properties. Develop different operational "recipes" for distinct feedstock blends.

- Establish Tolerances: Define acceptable ranges for key feedstock properties and reject batches falling outside these specifications to maintain experimental integrity.

Seasonality & Supply

Q2: Our research is hampered by the seasonal unavailability of specific agricultural residues. How can we ensure a year-round, consistent supply?

Seasonal variation results in fluctuating biomass availability and price, making it difficult to maintain continuous research operations [7] [8]. An inefficient supply chain can lead to feedstock unavailability [7].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Diversify Feedstock Portfolio: Identify and qualify multiple, complementary biomass types with different harvest windows. For example, combine corn stover (autumn) with woody residues from forestry operations (potentially year-round).

- Secure Strategic Storage: Invest in adequate, proper storage infrastructure (see Q4) to stockpile feedstock during peak harvest season for use during off-months.

- Develop Long-term Contracts: Move beyond spot purchasing. Establish formal agreements with suppliers or aggregators to guarantee a consistent supply of feedstock at a pre-determined quality [9].

Physical & Biological Degradation

Q3: During storage, our biomass feedstock loses mass and heating value. What are the best practices to prevent this biodegradation?

Biomass is susceptible to microbial degradation, which leads to dry matter loss, reduced energy density, and potential self-heating hazards [7]. This biodegradation is a major logistical challenge [7].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Reduce Moisture Content: The single most important factor. Dry biomass to below 20% moisture content immediately after harvest/collection to significantly inhibit microbial activity.

- Implement Proper Storage Geometry: For loose biomass, compact piles to reduce oxygen penetration. For durable forms like pellets, use sealed silos or containers.

- Apply Preservatives: For long-term storage, consider using organic acid-based preservatives (e.g., propionic acid) to inhibit mold and fungal growth.

- Monitor Pile Temperature: Install temperature sensors within storage piles. A rising temperature indicates active biodegradation and necessitates turning the pile or using it immediately.

Q4: What are the most effective storage and pre-processing methods to mitigate degradation and enhance logistics?

The low bulk density and energy density of fresh biomass make storage costly and transportation inefficient [7]. Preprocessing is crucial to address these issues [7].

Comparative Analysis of Storage & Pre-processing Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Impact on Degradation | Impact on Energy Density | Best for Feedstock Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelletization | Compaction into dense, uniform pellets | Significantly reduces biodegradation by lowering moisture and limiting O₂ exposure [7] | Dramatically increases bulk and energy density, improving transport economics [7] | Forestry residues, agricultural residues, uniform wastes |

| Ensiling | Anaerobic fermentation in airtight conditions (e.g., bale silage) | Preserves biomass; acids produced during fermentation inhibit spoilage | Minimal direct impact on density, but preserves original energy content | High-moisture herbaceous biomass (e.g., grass, corn stover) |

| First-stage Chipping | Size reduction in the field/forest | Increases surface area, which can speed up drying but also potential degradation if not managed | Improves bulk density compared to loose biomass, enhancing transportation efficiency [7] | Woody biomass, forestry residues |

| Covered Storage | Protection from rain and snow with tarps or sheds | Prevents re-wetting and removes a primary driver of decomposition | Prevents losses, thereby preserving original energy density | All feedstock types, particularly post-drying |

Experimental Protocols for Challenge Analysis

Protocol 1: Quantifying Dry Matter Loss During Storage

Objective: To empirically determine the degradation rate of a specific biomass feedstock under defined storage conditions.

Materials:

- Biomass sample (e.g., wood chips, corn stover)

- Forced-air oven

- Analytical balance (±0.01 g)

- Insulated containers or meshed bags for simulated storage

- Temperature and humidity data loggers

Methodology:

- Initial Characterization: Triplicate samples of the biomass are weighed (wet weight) and then dried in an oven at 105°C until constant weight to determine initial dry matter (DM) content.

- Storage Simulation: Place a known quantity (e.g., 5 kg) of biomass into storage containers. Store replicates under different conditions (e.g., open air, covered, pelletized).

- Monitoring: Record ambient temperature and relative humidity at the storage site weekly using data loggers.

- Final Measurement: After a pre-defined period (e.g., 30, 60, 90 days), retrieve samples, weigh them, and determine the final dry matter content.

- Calculation: Calculate dry matter loss using the formula:

- % Dry Matter Loss = [ (Initial DM weight - Final DM weight) / Initial DM weight ] x 100

Protocol 2: Assessing Compositional Variability Across Feedstock Batches

Objective: To profile the biochemical composition of different biomass batches to understand variability.

Materials:

- Ball mill

- Soxhlet extraction apparatus

- Fiber analyzer (e.g., ANKOM, Van Soest) or access to NIR spectroscopy

- Standard solvents (e.g., ethanol, benzene)

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Mill representative samples from each biomass batch to a fine, homogeneous powder (<1 mm particle size).

- Extractives Content: Determine extractives content by Soxhlet extraction using a suitable solvent. This removes non-structural components.

- Structural Analysis: Perform a standardized fiber analysis (e.g., Van Soest method or NREL/TP-510-42618) on the extractive-free sample to quantify:

- Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF): Hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin.

- Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF): Cellulose and lignin.

- Acid Detergent Lignin (ADL): Lignin.

- Data Integration: Calculate cellulose (ADF - ADL), hemicellulose (NDF - ADF), and lignin (ADL) percentages. Use this data to create a compositional profile for each batch and identify outliers.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Material Solutions

| Item | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Biochar Stability Standards | Certified reference materials used to calibrate and validate methods for measuring biochar decomposition rates and carbon sequestration durability [10]. | Essential for accurate MRV (Measurement, Reporting, and Verification) in carbon removal studies. |

| Carbon-14 Isotope Testing | Analytical method to distinguish and verify the split of biogenic CO₂ from fossil-based CO₂ in emissions or products, crucial for accurate carbon accounting [10]. | Waste-to-Energy (WtE) with CCS, life cycle assessment (LCA). |

| In-situ Gas Sensors | Devices for real-time monitoring of methane (CH₄) and CO₂ in biomass storage environments to detect and quantify sealing integrity failures and microbial degradation [10]. | Storage optimization studies, degradation rate analysis. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Software | Tools (e.g., using the GREET model) to conduct cradle-to-grave environmental impact analyses, including emissions from feedstock transport and processing [10] [11]. | Sustainability impact studies, carbon footprint calculation. |

| GIS & Biomass Mapping Tools | Geographic Information Systems used to model and analyze biomass availability, logistics networks, and optimal facility siting based on spatial data [12]. | Supply chain feasibility, sourcing strategy research. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What makes logistics the primary cost driver in biomass utilization?

Logistical costs often determine the economic feasibility of using residual biomass. The supply chain involves numerous complex and costly unit operations, including collection, transportation, storage, and preprocessing, to move biomass from its scattered sources to conversion facilities. Transportation costs alone constitute the majority of the total supply chain costs for biomass energy production. The inherent challenges of biomass—such as its high moisture content, low calorific value, and dispersed availability—further amplify these costs. [13]

What are the most common storage-related challenges that impact costs and quality?

Storage is a critical, yet often problematic, part of the biomass supply chain. Improper storage leads to:

- Quality Degradation: Aerobic respiration (rotting) during storage reduces the mass and quality of the biomass. [14]

- Chemical Composition Changes: Variations in moisture and ash content can occur, negatively impacting the fuel's value and processability. [14]

- Combustible Dust: Stored and handled biomass generates fine dust, which settles on surfaces and poses a significant fire and explosion hazard, requiring rigorous safety controls. [2]

What advanced methodologies are used to optimize the biomass supply chain?

Researchers use sophisticated modeling and optimization techniques to manage the complexity and uncertainty in biomass supply chains. The following table summarizes the primary methods identified in recent literature: [13] [15]

| Methodology | Primary Application | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Programming | Strategic supply chain design and planning | Provides a foundational model for optimizing resource allocation under constraints. |

| Genetic Algorithms (GA) | Solving complex, non-linear optimization problems | Effective at finding good solutions in large, complex search spaces. |

| Tabu Search (TS) | Routing and scheduling problems | Helps avoid local optima and explore new solutions by using memory structures. |

| Hybrid Simulation-Optimization | Integrated strategic-tactical-operational planning | Combines the forecasting power of simulation with the decision-making power of optimization; ideal for managing uncertainties. |

| Discrete Event Simulation | Analyzing the flow of biomass through the entire supply chain | Models sequential operations to identify bottlenecks and test scenarios. |

How can I troubleshoot low pellet quality in biomass densification processes?

Low pellet quality often stems from issues in raw material preparation and machine operation. Here are common problems and their solutions: [16]

| Problem | Possible Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Pellet Durability | Incorrect moisture content (too wet or too dry) | Adjust moisture to the ideal 10-15% range. |

| Lack of pre-conditioning | Implement a conditioning stage to soften fibrous material. | |

| Improper cooling after production | Ensure a dedicated cooling stage to harden pellets. | |

| Rapid Equipment Wear | Lack of pre-cleaning | Remove dust, sand, and metal fragments from feedstock before pelleting. |

| Pellet Mill Jamming | Incorrect raw material sizing | Reduce particle size to the ideal 3-5 mm range. |

| Overfeeding the mill | Use a controlled feeder to regulate material input. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Managing Combustible Dust in Biomass Facilities

Combustible dust is a major safety and operational risk in biomass handling. This guide outlines a systematic approach to risk management based on the NFPA 652 standard. [2]

Workflow: Combustible Dust Management

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Perform a Dust Hazard Analysis (DHA): This is a mandatory first step per NFPA 652. Systematically identify all areas where combustible dust accumulates, such as on conveyor belts, in silos, and on elevated surfaces. [2]

- Implement Engineering Controls: This is the most effective line of defense.

- Install dust collection systems and local exhaust ventilation at key transfer points.

- Use explosion venting equipment on processing units and storage silos to safely direct the force of an explosion outward.

- Integrate spark detection and suppression systems in conveyor ducts. [2]

- Establish Administrative Controls:

- Develop and enforce a rigorous housekeeping program using methods that do not generate dust clouds (e.g., specialized vacuum systems instead of compressed air).

- Establish standard operating procedures (SOPs) for equipment operation and maintenance in dust-prone areas. [2]

- Train Personnel:

- Train all relevant workers on the specific hazards of combustible dust.

- Ensure they understand the DHA findings, SOPs, and emergency procedures. [2]

Guide 2: Designing a Resilient Biomass Supply Chain

This guide provides a methodology for researchers and planners to design a supply chain that is both cost-effective and robust against disruptions and uncertainties, such as variations in biomass availability, weather, and market prices. [13] [15]

Workflow: Supply Chain Design & Optimization

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Problem Scoping and Data Collection:

- Define the System: Determine the geographic scope, types of biomass (e.g., agricultural, forestry), and the final product (e.g., pellets, electricity).

- Gather Data: Collect data on seasonal biomass availability, locations of sources and potential processing depots, transportation networks, and all associated costs (harvesting, transportation, preprocessing, storage). [13]

- Model Formulation:

- Select a Modeling Technique: Choose an approach based on the problem's complexity.

- Use Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) for designing the network structure (e.g., locating facilities).

- Apply Stochastic Modeling or Hybrid Simulation-Optimization to account for uncertainties in supply, demand, and costs. [15]

- Select a Modeling Technique: Choose an approach based on the problem's complexity.

- Scenario Analysis and Optimization:

- Implementation and Monitoring:

- Implement the chosen design and establish Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for cost, quality, and reliability.

- Use a feedback loop to continuously collect performance data and refine the model for future planning cycles. [13]

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Biomass Logistics

This table details key technologies and materials crucial for experimental and pilot-scale work in biomass logistics and preprocessing. [16] [17]

| Tool / Solution | Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Precision Moisture Analyzers | Accurately measure moisture content in biomass samples. | Critical for standardizing feedstock to the 10-15% moisture range required for pelleting and other thermochemical processes. [16] |

| Laboratory Pellet Mill | Small-scale production of biomass pellets for quality testing. | Used to test different feedstock mixes, die specifications (e.g., 6mm vs. 8mm), and process parameters without large-scale runs. [16] |

| Load Cells & Weighing Systems | Precisely measure force and weight in handling equipment. | Integrated into conveyor belts and hoppers to monitor biomass flow rates, optimize feed rates, and prevent overloading in experimental setups. [17] |

| Dust Hazard Analysis (DHA) Toolkit | Assess combustible dust risks in laboratory and pilot-scale handling systems. | Includes equipment for dust sampling, particle size analysis, and checklists for identifying hazardous locations, ensuring experimental safety. [2] |

| Torque Transducers | Monitor torque in rotating equipment. | Used in research on densification (e.g., pelleting, torrefaction) to understand energy input and optimize process control for consistent quality. [17] |

| Discrete Event Simulation Software | Model the flow of biomass through a series of operations. | Allows researchers to virtually test different supply chain configurations, identify bottlenecks, and assess the impact of uncertainties before physical implementation. [15] |

FAQs: Troubleshooting Biomass Logistics and Storage Challenges

This technical support guide addresses common challenges in biomass feedstock supply chains for researchers and scientists. The FAQs and solutions are framed within the broader context of overcoming biomass logistics and storage challenges.

1. FAQ: How can I prevent significant dry matter loss and quality degradation during long-term storage of biomass?

- Problem: Biomass feedstocks, particularly agricultural residues like corn stover, often require months of storage to enable year-round biorefinery operations. Uncontrolled microbial degradation leads to dry matter loss, self-heating, and increased recalcitrance [18] [19].

- Solutions & Protocols:

- Monitor Moisture Content: For aerobically stored biomass (e.g., in bales), ensure moisture content is below 36% (wet basis) to significantly reduce degradation rates. Conduct routine oven drying or infrared moisture analysis to monitor levels [18] [20].

- Utilize Anaerobic Storage (Ensiling): For high-moisture feedstocks, employ anaerobic storage through ensiling. This method preserves dry matter and maintains bioconversion potential, with only minor structural losses in carbohydrates [18].

- Consider Preconditioning: Preconditioning biomass through anaerobic storage before fractionation can help stabilize the material and isolate distinct fractions for multiple product applications [18].

- Blending Feedstocks: Blend difficult-to-preserve novel feedstocks (e.g., flower strips) with more stable materials like corn stover. This can improve overall silage quality and repress undesirable microbial activity [18].

2. FAQ: What are the primary strategies for reducing the high costs of biomass transportation?

- Problem: The low bulk and energy density of raw, dispersed biomass makes transportation energetically unfavorable and expensive, often undermining project viability [7] [13].

- Solutions & Protocols:

- Implement Densification: Process biomass into pellets or chips. This increases energy density, improves transport efficiency, reduces degradation during transit, and lowers costs [7].

- Apply Advanced Optimization Models: Use computational models to optimize collection routes and minimize transportation distances. Employ techniques like:

- Linear Programming (LP) for initial, simplified characterization of the supply chain.

- Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Tabu Search (TS) to handle complex, real-world variables and find near-optimal solutions for collection and transport logistics [13].

- Establish Regional Biomass Depots: Create localized preprocessing hubs for initial chipping or pelletizing. This reduces the transport volume of raw biomass from the source, addressing the challenge of scattered collection sites [18].

3. FAQ: How can I manage the high variability in biomass feedstock quality and composition?

- Problem: Inconsistent biomass quality—due to factors like feedstock type, seasonality, and storage conditions—causes feeding, flowability, and conversion challenges in biorefineries, leading to equipment downtime [19].

- Solutions & Protocols:

- Adopt a "Quality-by-Design" Supply System: Move beyond simple homogenization. Incorporate advanced preprocessing operations like fractionation and merchandising to produce feedstock fractions with specific qualities tailored to different conversion processes (e.g., biofuels vs. chemicals) [19].

- Perform Standardized Compositional Analysis: Use established laboratory analytical procedures (LAPs) to characterize biomass. Key steps include:

- Sample Preparation: Dry and mill samples through a 2-mm screen for uniform particle size [20].

- Extractives Analysis: Determine water-soluble materials to report composition on an "as-received" basis [20].

- Two-Step Acid Hydrolysis: Quantify structural carbohydrates and lignin in extractives-free biomass. Follow standard protocols for hydrolysis, filtration, and HPLC analysis of sugars [20].

- Utilize Rapid Analysis Techniques: Develop Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy calibration models correlated with wet chemical data for fast, non-destructive prediction of biomass composition [20].

4. FAQ: What logistical solutions exist for creating resilient, multi-feedstock supply chains?

- Problem: Reliance on a single, high-quality feedstock (like wood) can be expensive and unsustainable. Creating supply chains that can handle diverse and variable feedstocks (e.g., agricultural residues, municipal solid waste) is complex [7] [19].

- Solutions & Protocols:

- Feedstock Blending: Blend different biomass feedstocks to achieve a suitable average composition, mitigating the limitations of lower-quality residues (e.g., high ash content) [7].

- Multi-Feedstock Modeling: Apply sophisticated modeling frameworks such as Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) and agent-based modeling to design supply chains that integrate forestry, agricultural, and municipal solid waste resources, optimizing for cost, sustainability, and resilience [12].

- Invest in Flexible Biorefining Infrastructure: Advocate for and invest in regional biorefineries designed with flexible processing capabilities to handle a variety of feedstocks and produce multiple outputs, supporting a circular bioeconomy [21].

Quantitative Data on Biomass Feedstocks and Storage

Table 1: Global Biomass Power Generation Market Forecast (2024-2030)

| Metric | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Market Value in 2024 | US$90.8 Billion | Base year value [22] |

| Projected Value in 2030 | US$116.6 Billion | Forecasted value [22] |

| CAGR (2024-2030) | 4.3% | Compound Annual Growth Rate [22] |

| Forest Waste Segment (2030) | US$51 Billion | Projected value by 2030 [22] |

| Agriculture Waste Segment CAGR | 4.7% | Growth rate over the forecast period [22] |

Table 2: Critical Biomass Storage Parameters and Impacts

| Parameter | Threshold/Effect | Impact on Downstream Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture Content (Aerobic) | >36% (wet basis) leads to significant dry matter loss [18] | Increased recalcitrance; reduced sugar yields [18] |

| Storage Duration (Summer) | Higher dry matter loss vs. winter storage [18] | Can alter structural carbohydrates and increase hydrophilicity [18] |

| Anaerobic Storage (Ensiling) | Minimal structural carbohydrate loss [18] | Bioconversion requirements remain constant; may aid preprocessing via ultrastructural changes [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomass Analysis

Protocol 1: Determining Total Solids and Moisture Content in Biomass

Function: This is a fundamental first step to report all subsequent analytical data on a consistent dry-weight basis [20].

- Weighing: Obtain a representative sample. Weigh an moisture analyzer capsule or dish. Add the biomass sample and record the initial total weight.

- Drying: Dry the sample in a conventional oven at 105°C or using an automatic infrared moisture analyzer until a stable weight is achieved.

- Calculation: Calculate the percentage of total solids and moisture content using the dry weight and initial weight [20].

Protocol 2: Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass

Function: This quantitative wet chemical method is the standard for determining the core compositional elements of lignocellulosic biomass [20].

- Extractives Removal: Perform a preliminary extraction with water or ethanol to remove non-structural materials. Report compositions on an "as-received" basis [20].

- Two-Stage Acid Hydrolysis:

- Primary Hydrolysis: Incubate the extractives-free biomass with 72% sulfuric acid at 30°C for 1 hour, with continuous stirring.

- Secondary Hydrolysis: Dilute the acid to 4% concentration and autoclave the mixture at 121°C for 1 hour. This step hydrolyzes oligomers into monomeric sugars.

- Filtration and Quantification:

- Acid-Insoluble Lignin: Filter the hydrolysate using a crucible and vacuum filtration. The solid residue is dried and weighed as acid-insoluble lignin.

- Carbohydrates: Analyze the liquid hydrolysate (filtrate) via High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to quantify monomeric sugars (e.g., glucose, xylose). Use appropriate anhydro corrections to report as glucan, xylan, etc. [20].

Biomass Supply Chain Optimization Workflow

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing common challenges in biomass supply chains, moving from problem identification to solution implementation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for Biomass Analysis

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄), 72% & 4% | Primary reagent for the two-step acid hydrolysis process to depolymerize structural carbohydrates into monomeric sugars for quantification [20]. |

| HPLC Standards (Glucose, Xylose, etc.) | Pure sugar standards used to calibrate the High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system for accurate identification and quantification of sugars in biomass hydrolysates [20]. |

| Deionized Water | Used for dilution in hydrolysis, rinsing of residues, and preparation of solutions to prevent interference from ions and contaminants [20]. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectrometer | Instrument for rapid, non-destructive prediction of biomass composition. Requires calibration models developed from correlating NIR spectra with wet chemical analysis data [20]. |

| Vacuum Filtration Apparatus | Setup including a flask, crucible holder, and filtration crucible used to separate acid-insoluble lignin from the liquid hydrolysate after the second-stage hydrolysis [20]. |

| Reference Biomass Materials | Homogenous, well-characterized biomass standards (e.g., from NIST) used to validate analytical methods and ensure accuracy and precision across measurements [20]. |

Implementing Advanced Technologies and Process Solutions

AI and Machine Learning for Predictive Logistics and Route Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core function of AI route optimization in a logistics context? AI route optimization determines the most cost-effective and efficient paths for vehicles by analyzing complex variables in real-time. Unlike static rule-based systems, it dynamically processes data such as live traffic, weather, vehicle capacity, and delivery windows to create and continuously adjust routes. This minimizes travel time, reduces fuel consumption, and ensures on-time deliveries [23] [24].

Q2: How can predictive logistics benefit biomass supply chain operations specifically? Predictive logistics uses AI and machine learning to forecast potential disruptions and demand patterns. For biomass logistics, this means anticipating delays at processing facilities, predicting the optimal amount of feedstock required to avoid shortages or spoilage, and proactively rerouting shipments around issues like road closures or adverse weather. This leads to more consistent feedstock supply, reduced material loss, and lower operational costs [25] [26].

Q3: What are the common data sources needed to implement an AI-driven logistics system? A successful implementation relies on ingesting data from multiple sources:

- Telematics and GPS: Provides real-time vehicle location, speed, and fuel levels [23].

- Traffic APIs (e.g., Google Maps): Deliver live updates on congestion, road closures, and accidents [23] [24].

- Historical Delivery Logs: Informs the system about patterns that typically cause delays [23].

- Inventory Management Systems: Provide data on feedstock and product availability [27].

- Weather Data: Allows the system to anticipate and plan for weather-related disruptions [23].

Q4: Our research involves sensitive experimental data. How is data security handled in these AI platforms? Many AI platforms, including no-code solutions, prioritize data security through robust measures. These include permission-based access control to ensure only authorized personnel can view or edit sensitive data, and the use of federated learning techniques that allow AI models to be trained on distributed datasets without exposing or moving the raw data itself, thus preserving privacy [27].

Q6: We have a limited budget for custom software development. Are there accessible options for researchers? Yes. No-code platforms are emerging as a viable solution, enabling researchers to build custom logistics tools and automate workflows without needing a team of developers. These platforms use drag-and-drop interfaces to create applications that can centralize data and integrate with AI for analysis and optimization, significantly lowering implementation costs [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Model Producing Inaccurate or Inefficient Routes

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete or Poor-Quality Input Data | 1. Verify all delivery locations have accurate coordinates.2. Check that vehicle capacity and service time parameters are correctly set.3. Validate that time windows for deliveries are logical and error-free. | Cleanse the input data. Ensure all necessary data fields are populated with accurate, real-world values. Implement data validation checks before running the optimization [24]. |

| Incorrectly Configured Constraints | 1. Review the system's constraint settings (e.g., driver working hours, vehicle weight limits).2. Compare configured constraints against actual operational rules. | Recalibrate the constraint solver within the AI system to accurately reflect all real-world operational and regulatory limitations [23]. |

| Lack of Real-Time Data Integration | 1. Confirm that APIs for live traffic and weather are connected and active.2. Check system logs for failures in data ingestion from these services. | Ensure seamless integration with real-time data feeds. The system must have access to dynamic external data to make informed routing decisions [23] [28]. |

Issue: System Failing to Adapt to Real-Time Disruptions

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Disabled Dynamic Rerouting | 1. Check the software settings to confirm that dynamic rerouting features are enabled.2. Review system alerts for any triggered but ignored rerouting suggestions. | Activate and configure the AI routing assistant or real-time decision engine to automatically propose and implement route changes when disruptions occur [23] [28]. |

| Poor Data Latency | 1. Measure the time delay between a real-world event (e.g., a road closure) and its appearance in the system.2. Test the connectivity and response time of integrated data APIs. | Switch to more reliable data providers or work with IT support to improve network connectivity and data processing speeds to minimize latency [26]. |

| Overridden AI Suggestions | 1. Audit the system's log to see how often and why manual user overrides occur. | Analyze the reasons for overrides. Use the system's intelligent route refinement feature to learn from manual adjustments, improving future automated suggestions and building user trust [28]. |

Table 1: AI Performance Metrics in Logistics Operations

| KPI | Impact of AI Implementation | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Logistics Costs | Reduced by 5-20% | [26] |

| Inventory Levels | Reduced by 20-30% | [23] |

| Fuel & Maintenance Costs | Reduced by 15% | [23] [24] |

| Delivery Accuracy | Improved by 30% | [24] |

| On-time Arrivals | Improved by 35% | [23] |

| Planning & Downtime | Predictive maintenance cuts downtime by 50% and breakdowns by 70% | [27] |

| Metric | Value (2024-2029) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Global Market Size (2024) | $4.01 Billion | [25] |

| Projected Market Size (2029) | $6.40 Billion | [25] |

| CAGR (2025-2029) | 9.7% | [25] |

| Key Service Types | Transportation, Storage, Handling, Inventory Management | Transportation is a primary service component [25] |

| Key Feedstock Types | Wood Pellets, Agricultural Residues, Forest Residues, Energy Crops | [25] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Implementing a Route Optimization API for Biomass Feedstock Transport

Objective: To integrate and validate an AI-driven route optimization API for planning efficient collection routes for agricultural residue biomass from multiple farms to a central processing facility.

Materials:

- NextBillion.ai Route Optimization API (or equivalent) [24]

- List of farm locations (GPS coordinates)

- Vehicle fleet details (capacity, type, availability)

- Data on biomass availability at each location

Methodology:

- Data Setup:

- Define Jobs: Create a job for each farm location requiring a pickup. Specify the location (latitude/longitude), the estimated time required for loading, and any time windows for access [24].

- Define Shipments: For each job, specify the volume or weight of biomass to be picked up [24].

- Define Vehicles: Input the fleet's details, including unique vehicle IDs, load capacity, starting location (depot), and working hours [24].

- Define Depots: Specify the starting and ending points for the vehicles, typically the processing facility [24].

API Integration:

- Use the POST method to submit the complete dataset (Jobs, Shipments, Vehicles, Depots) to the optimization engine [24].

- The system will return a unique job ID for tracking the request.

Execution and Retrieval:

- Use the GET method with the assigned job ID to retrieve the optimized routes once processing is complete [24].

- The results will include the sequence of stops for each vehicle, assigned shipments, and estimated travel times.

Validation:

- Compare the AI-proposed routes against manually planned routes for the same day based on total distance, estimated fuel consumption, and total time to complete all pickups.

- Monitor real-world execution, tracking adherence to the plan and on-time performance at the processing facility.

Protocol: Developing a Predictive Model for Biomass Feedstock Demand Forecasting

Objective: To create a machine learning model that accurately forecasts short-term demand for biomass feedstock at a power generation plant, optimizing inventory management and logistics scheduling.

Materials:

- Historical data on biomass consumption at the plant

- Historical weather data (temperature, season)

- Calendar data (holidays, weekdays/weekends)

- Data on scheduled maintenance or outages at the plant

Methodology:

- Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Gather at least two years of historical daily biomass consumption data.

- Collect corresponding historical data for external factors: average daily temperature, public holidays, and plant operational status.

- Clean the data, handling missing values and outliers.

Feature Engineering:

- Create input features (X) from the external data, such as:

is_holiday(binary)season(categorical)temperature_range(categorical)plant_operational(binary)

- The target variable (y) is the daily biomass consumption.

- Create input features (X) from the external data, such as:

Model Training and Selection:

- Split the data into training and testing sets (e.g., 80/20 split).

- Train multiple regression models (e.g., Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) on the training set.

- Evaluate model performance on the test set using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). Select the best-performing model.

Deployment and Monitoring:

- Integrate the trained model into the plant's logistics planning system.

- The model takes forecasts for the next day's weather and plant status to predict biomass demand.

- This forecast is used to schedule feedstock deliveries from suppliers, optimizing storage capacity and reducing the risk of shortages or overstocking. The model's accuracy should be re-validated periodically [27].

System Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

AI Route Optimization Workflow

Biomass Logistics Chain

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential AI and Logistics Tools for Research

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research Context |

|---|---|

| Route Optimization API | Provides the core algorithm for calculating the most efficient paths for biomass transport under multiple constraints. Essential for experimental routing simulations [24]. |

| No-Code Platform (e.g., Noloco) | Allows researchers without deep programming expertise to build custom applications for data collection, workflow automation, and visualizing logistics data [27]. |

| Geographic Information System (GIS) | Critical for visualizing geographic data, analyzing spatial relationships of biomass sources and facilities, and enhancing the accuracy of route planning [24]. |

| Predictive Analytics Software | Used to build and train models for forecasting biomass demand, predicting potential supply chain disruptions, and optimizing inventory management [27] [26]. |

| IoT Sensors & Telematics | Provide real-world data on vehicle location, fuel consumption, and the condition of biomass during transit (e.g., temperature, humidity), feeding the AI with essential input data [23] [26]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between torrefaction and pelletization, and in which order should they be performed?

Torrefaction and pelletization are distinct but complementary processes. Torrefaction, also known as mild pyrolysis, is a thermal pretreatment where biomass is heated to 200–300 °C in an inert atmosphere. This process significantly reduces the oxygen and moisture content of the biomass while increasing its calorific value [29] [30]. For example, torrefaction can cause an oxygen content reduction of up to 39.71% and increase calorific value from 17.41 MJ/kg to 25.3 MJ/kg [29]. Pelletization is a densification process that compresses biomass into dense, uniform pellets, drastically reducing its volume and improving handling and transport efficiency [29] [31].

Research indicates that the sequence "torrefy first, then pelletize" is more effective for enhancing overall fuel quality. This method improves the pelletization efficiency of the torrefied material and produces pellets with higher energy density, better hydrophobicity, and superior mechanical strength [29].

FAQ 2: Our biomass pellets exhibit low mechanical strength and disintegrate during handling and storage. What are the primary factors we should optimize?

Low mechanical strength and poor durability are frequently traced to suboptimal process parameters and material composition. The key factors to investigate and control are:

- Process Parameters: Temperature and pressure during densification are critical. For instance, studies on materials like spent coffee grounds and corn stalk have shown that optimal pelletizing conditions typically fall within a temperature range of 100–150 °C and a pressure range of 10–30 MPa [29]. A robust statistical approach like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) can be used to find the precise combination that maximizes density and strength for your specific feedstock [29].

- Use of Binders: Organic binders can dramatically improve pellet cohesion and strength. These binders, such as lignosulfonate (LS), carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), and carboxymethyl starch (CMS), act by forming chemical adsorption through carboxyl groups and hydrogen bonding through hydroxyl groups with the biomass particles [32]. They are particularly valuable for feedstocks that are inherently difficult to bind.

FAQ 3: How does torrefaction specifically improve the gasification performance of biomass for syngas production?

Torrefaction pretreatment enhances the properties of biomass in ways that directly benefit downstream gasification [29]:

- Increased Energy Density: It produces a more energy-dense feedstock, improving the energy output of the gasification process.

- Improved Feedstock Uniformity: It creates a more homogeneous and hydrophobic solid, which leads to more consistent and efficient gasification.

- Enhanced Syngas Quality: Gasification of torrefied and densified pellets is known to yield higher volumes of hydrogen (H₂) and carbon monoxide (CO), the primary components of syngas. Concurrently, it reduces the production of undesirable by-products like tars, methane (CH₄), and total hydrocarbons [29]. Operating the gasifier at higher temperatures (e.g., 900 °C) can further increase gas yield and calorific value [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Pellet Quality Across Different Biomass Feedstocks Potential Cause & Solution: Feedstock heterogeneity. Biomass from different sources (e.g., agricultural residues, forestry waste) has varying compositions of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which directly impact densification behavior [30]. Action Plan:

- Characterize Feedstock: Analyze the proximate composition (moisture, volatile matter, fixed carbon, ash) and elemental analysis of each feedstock type.

- Adjust Pretreatment: For high-moisture feedstocks, ensure adequate drying. Torrefaction pretreatment can be tuned (mild, medium, or severe at 210–300 °C) to standardize the properties of diverse feedstocks [30].

- Optimize Parameters Separately: Do not assume one set of pelletization parameters (temperature, pressure, binder type) will work for all feedstocks. Use design of experiments (DoE) to find the optimum for each major feedstock type [29].

Problem: High Energy Consumption During the Densification Process Potential Cause & Solution: Suboptimal particle size, moisture content, and excessive pressure. Action Plan:

- Preprocess Feedstock: Ensure biomass is ground to a consistent and appropriate particle size. A smaller, more uniform particle size can lead to better inter-particle bonding and require less force for compaction [14].

- Control Moisture: The moisture content must be carefully controlled to an optimal level (typically 8-15% for many feedstocks) to act as a natural binder and lubricant without causing steam generation and cracks during compression [32] [14].

- Calibrate Equipment: Use the minimum pressure necessary to achieve target density. Over-pressurization wastes energy and can sometimes damage the pellet mill die [29].

Problem: Excessive Dust Formation and Low Green Strength in Pellets with Organic Binders Potential Cause & Solution: The loss of strength due to the decomposition of organic binders before a permanent bond is formed in the pellet. Action Plan:

- Binder Formulation: Explore composite binders. Combining different organic binders or adding small amounts of inorganic additives (like low-iron oxides or nano-CaCO₃) can help mitigate high-temperature strength loss [32].

- Optimize Molecular Structure: Research indicates that improving the degree of substitution of functional groups (e.g., carboxyl groups) and the overall degree of polymerization of the organic binder can enhance its bonding performance and temperature resistance [32].

Table 1: Impact of Torrefaction on Biomass Fuel Properties

| Biomass Feedstock | Torrefaction Temperature | Key Property Changes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Caltrop Shell | Not Specified | Oxygen content ↓ 39.71%, Calorific value ↑ from 17.41 to 25.3 MJ/kg | [29] |

| Rice Husk | 300 °C | Calorific value ↑ 20.27% | [29] |

| General Lignocellulosic | 200 - 300 °C | Increased energy density, Improved grindability, Enhanced hydrophobicity | [30] |

Table 2: Optimized Pelletization Parameters for Selected Feedstocks (Based on RSM)

| Biomass Feedstock | Optimal Temperature Range | Optimal Pressure Range | Resulting Relaxed Density | Resulting Compressive Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn Stalk (CS) | 100 - 150 °C | 10 - 30 MPa | 1285.5 - 1412.13 kg/m³ | 38.0 - 49.45 MPa |

| Agaric Fungus Bran (AFB) | 100 - 150 °C | 10 - 30 MPa | 1281.38 - 1342.09 kg/m³ | 36.16 - 43.06 MPa |

| Spent Coffee Grounds (SCG) | 100 - 150 °C | 10 - 30 MPa | 1089.92 - 1200.55 kg/m³ | 12.25 - 17.50 MPa |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimization of Pelletization Parameters using Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

Objective: To systematically determine the optimal temperature and pressure for pelletizing a novel biomass feedstock to maximize relaxed density and compressive strength. Materials and Equipment:

- Torrefied biomass sample (e.g., corn stalk torrefied at 240°C) [29]

- Manual hydraulic press with heated die [29]

- Desiccator

- Analytical balance

- Universal testing machine for compressive strength testing

Methodology:

- Experimental Design: Use a Central Composite Design (CCD) within RSM. Define independent variables (e.g., Temperature: 100-150°C, Pressure: 10-30 MPa) and responses (Relaxed Density, Compressive Strength) [29].

- Pellet Preparation: For each experimental run, load a fixed mass of biomass into the pre-heated die. Apply the designated pressure and hold for a consistent time (e.g., 1-2 minutes).

- Ejection and Conditioning: Eject the pellet and allow it to cool to room temperature in a desiccator to prevent moisture absorption.

- Quality Testing:

- Relaxed Density: Measure the pellet's mass and dimensions after 24 hours to calculate its density.

- Compressive Strength: Use a universal testing machine to apply a crushing force until pellet failure. Record the maximum force sustained.

- Statistical Analysis: Input the data into statistical software to fit a regression model, analyze variance (ANOVA), and generate 3D response surface plots to identify the optimum conditions [29].

Protocol 2: Evaluating the Performance of Biomass-Based Binders

Objective: To assess the effectiveness of different organic binders (e.g., Lignosulfonate, CMC, CMS) on the strength of biomass pellets. Materials and Equipment:

- Iron ore concentrate or model biomass feedstock [32]

- Organic binders (Lignosulfonate, CMC, CMS) [32]

- Laboratory mixer

- Cylindrical pellet molds (e.g., 50 mm diameter)

- Curing chamber (25 ± 1 °C, 85 ± 2% humidity) [33]

- Unconfined Compression Strength (UCT) test apparatus [33]

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Mix the dry feedstock with the binder at a specified dosage (e.g., 0.5-2.0% by weight). Add a controlled amount of water to achieve the desired moisture content.

- Pellet Formation: Compact the mixture into cylindrical molds in multiple layers using a standardized rod or mechanical press [33].

- Curing: Seal the specimens to prevent moisture loss and cure them in a controlled environment for set durations (e.g., 7, 14, 28 days) [33].

- Strength Testing: After curing, test the pellets for unconfined compressive strength (qu) using a UCT machine. Compare the results against control samples (no binder or bentonite binder) and established standards (e.g., ACI-230, FHWA) [33].

Experimental Workflow and Pathways

Biomass Preprocessing and Conversion Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Biomass Pre-processing Research

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Lignosulfonate (LS) | Organic binder derived from lignin in papermaking waste streams [32]. | Adsorptive binder; relies on carboxyl groups for chemical adsorption and hydroxyl groups for hydrogen bonding [32]. |

| Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) | Water-soluble polymer derived from cellulose [32]. | Acts as an adsorptive binder; high viscosity and good adhesion to particle surfaces [32]. |

| Carboxymethyl Starch (CMS) | Modified starch-based binder [32]. | A renewable, adsorptive binder similar to CMC, often used as an alternative [32]. |

| Torrefied Biomass Char | The solid product from torrefaction, used as the primary material for densification [29]. | High energy density, hydrophobic, and improved grindability compared to raw biomass [29] [30]. |

| Wood Pellet Fly Ash (WA) | Byproduct from wood pellet combustion; can be used in blended binders for other applications [33]. | Rich in silica and alumina; high pH; reactive component when blended with materials like GGBS and cement [33]. |

Technical Support Center: FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to support researchers and scientists working to overcome challenges in biomass logistics and storage. The content is framed within the context of advanced biomass handling systems and the critical role of controlled environment warehousing in preserving material quality for research and development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary fire risks when storing biomass, and how are they mitigated in a Typhon Bale System?

Biomass materials are organic and prone to spontaneous combustion during storage [34]. In a Typhon Bale System, this inherent safety concern is mitigated through several key design and operational features:

- Totally Enclosed Handling: The system utilizes completely enclosed ship unloaders, conveyors, and processing equipment to minimize the creation of dust, which reduces both explosion risks and the fuel for fires [34].

- ATEX Compliance: The safety systems are designed to meet CE conformity and the latest ATEX directives, which provide standards for equipment intended for use in explosive atmospheres [34].

- Advanced Material Blending: Automated stacker-reclaimers are used not only for piling and retrieving material but also for blending it. This process is particularly important for organic commodities as it reduces fiber losses from microbial action and prevents dangerous heat build-up within storage piles [34].

Q2: Why is humidity control so critical in warehousing for biomass research materials, and how is it maintained?

Maintaining optimal humidity levels is crucial because fluctuations can lead to significant spoilage, mold growth, and degradation of biomass samples, ultimately compromising experimental integrity [35] [36].

- Preventing Mold and Spoilage: High humidity in summer can cause mold growth and product spoilage, while low humidity in winter can dry out materials, altering their physical properties [35].

- Systematic Regulation: Climate-controlled warehouses employ high-strength humidifiers and dehumidifiers to actively manage humidity levels [37]. These are often part of an integrated Automated Climate Monitoring system that uses sensors to provide real-time control over humidity, temperature, and air quality [35].

Q3: Our research facility handles diverse biomass feedstocks. Can a single unloading system process different types of biomass?

Yes, high-capacity, multi-fuel unloaders are designed for this exact purpose. For example, Siwertell unloaders can seamlessly alternate between handling coal, wood chips, and palm kernel shells without requiring adjustments to the machine [34]. This flexibility is essential for research facilities that work with various feedstock materials, as it ensures efficient and uninterrupted logistics while minimizing equipment investment costs.

Q4: What are the common signs of software instability in an automated biomass grinding and processing system?

While the search results do not detail software for biomass grinders specifically, general principles from industrial machine software troubleshooting can be applied. Common signs of instability include [38]:

- System Crashes: Frequent crashes or unresponsive interfaces, especially during specific actions like saving operational data or initiating a calibration cycle.

- Data Processing Glitches: Intermittent display freezes, incorrect calculations of output parameters, or delayed responses from the control system, potentially indicating memory overflow or corrupted firmware.

- Calibration Errors: Inconsistent measurement results or error messages related to "calibration failed," suggesting misaligned parameters between the software and the machine's physical configuration.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Temperature Inconsistencies in a Climate-Controlled Storage Warehouse

Maintaining a consistent temperature is fundamental for preserving the quality of biomass samples. Fluctuations can lead to spoilage, loss of efficacy, or altered material properties [35].

Problem: Inconsistent internal temperature, with hot or cold spots, leading to potential sample degradation.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Verify Sensor Calibration: Check the calibration of all temperature sensors throughout the facility. Use a trusted reference thermometer to verify readings.

- Map Airflow: Investigate if shelving or pallet arrangements are obstructing airflow, creating hot spots [37].

- Check Insulation and Seals: Inspect door seals and building insulation for damage, which can allow external temperatures to disrupt the internal environment, especially during seasonal extremes [37].

- Review System Logs: Analyze the climate control system's logs for error codes or records of compressor/heater failures.

Resolution Protocol:

- Re-calibrate Sensors: Follow manufacturer procedures to recalibrate any faulty sensors.

- Re-organize Storage: Rearrange storage layouts to ensure unobstructed airflow from HVAC systems.

- Install Door Seals: Apply or replace sealing strips around loading bay doors and other openings to prevent air leakage [37].

- System Upgrade: Consider upgrading to a system with forced, targeted air-cooling for faster temperature recovery after door openings [37].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical process for diagnosing and resolving temperature inconsistencies:

Guide 2: Addressing Reduced Throughput in a Biomass Grinding Circuit

A drop in the processing capacity of grinders and mills can create bottlenecks in the preparation of biomass feedstocks for analysis or conversion.

Problem: Biomass grinder is processing less than its rated capacity (e.g., metric tons per hour).

Diagnostic Steps:

- Inspect for Wear: Check the grinding tips, screens, and hammers for excessive wear, which is the most common cause of reduced throughput.

- Check for Clogs: Inspect the infeed conveyor and the area around the grinder's rotor for material clogs or jams.

- Verify Feedstock Consistency: Ensure the feedstock (e.g., stumps, wood residues) matches the specifications the grinder was configured for. Unexpectedly tough or contaminated material can slow processing.

- Monitor Power Draw: Check if the motor is drawing less than its rated amperage, which could indicate a drive or control system issue.

Resolution Protocol:

- Replace Worn Parts: Schedule maintenance to replace worn grinding elements according to the manufacturer's guidelines.

- Clear Jams: Safely lock out the equipment and clear any obstructions in the infeed and grinding chambers.

- Pre-screen Material: Implement a pre-screening system to remove oversized or contaminating materials before they enter the grinder [34].

- Consult Technical Support: If the issue persists with power systems or software controls, contact the equipment manufacturer's support team with detailed error logs.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Evaluating the Shelf-Life Stability of Biomass Samples Under Various Storage Conditions

1. Objective: To determine the degradation rate of key biomass material properties under different temperature and humidity conditions to establish optimal storage parameters.

2. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Divide a homogeneous biomass sample (e.g., wood pellets, ground agricultural waste) into multiple identical aliquots.

- Experimental Groups: Place aliquots into different environmental chambers programmed to simulate various seasonal conditions (e.g., summer heat/high humidity, winter cold/low humidity) and one set at ideal control conditions [35].

- Monitoring: Use automated climate monitoring systems to continuously log temperature and humidity in each chamber [35] [36].

- Sampling & Analysis: At predetermined intervals (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 8 weeks), remove samples for analysis.

3. Key Parameters to Measure:

- Moisture Content: Gravimetric analysis.

- Calorific Value: Using a bomb calorimeter to assess energy content degradation.

- Microbial Load: Colony-forming unit (CFU) counts to quantify mold and bacterial growth.

Table 1: Quantitative Analysis of Biomass Sample Degradation Over Time

| Storage Condition (Temp °C / % RH) | Moisture Content (% Change from Baseline) | Calorific Value (MJ/kg) | Microbial Load (CFU/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (Day 0) | - | 18.5 | < 100 |

| 25°C / 60% RH (8 weeks) | +1.5% | 18.3 | 5,200 |

| 35°C / 80% RH (8 weeks) | +4.2% | 17.8 | 45,000 |

| 5°C / 30% RH (8 weeks) | -2.1% | 18.4 | 350 |

| Control (15°C / 50% RH) (8 weeks) | +0.3% | 18.5 | 150 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Biomass Logistics and Storage Research

| Item | Function / Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Automated Climate Monitoring System | Integrated sensor networks for real-time, continuous monitoring of temperature, humidity, and air quality in experimental storage environments [35] [36]. |

| Bomb Calorimeter | Standard apparatus for measuring the gross calorific value of biomass samples, a key metric for energy content and material quality [34]. |

| Horizontal Grinding System | Heavy-duty equipment (e.g., WSM Titan grinder) for processing diverse and challenging biomass feedstocks like stumps and root balls into a consistent, analyzable particle size [34]. |

| Air-Supported Conveyor | Equipment for transporting biomass materials with minimal degradation and dust generation, preserving sample integrity during laboratory-scale logistics simulations [34]. |

| IoT Integration Platform | Enables seamless integration of various sensors and systems, providing researchers with real-time data for predictive maintenance and remote monitoring of experiments [35] [36]. |

| Humidifiers/Dehumidifiers | High-strength units used to actively manage and precisely control humidity levels within storage chambers for stability studies [37]. |

The integration of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and the Internet of Things (IoT) creates a powerful digital toolset for overcoming biomass logistics and storage challenges. This system provides real-time visibility into the location, condition, and status of biomass feedstocks from source to processing plant.

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does IoT help detect potential biomass spoilage during storage? IoT devices like temperature and humidity sensors provide real-time visibility into storage conditions, enabling early detection of issues that could lead to spoilage [39]. These sensors monitor environmental conditions within storage facilities and trigger alerts if readings fall outside predefined safe ranges for your specific biomass type.

Q2: What are the most critical IoT metrics for biomass logistics? The most critical metrics for maintaining biomass quality and logistics efficiency are [39]:

- Asset Location and Movement: GPS location, transit, and dwell time.

- Environmental Conditions: Temperature and humidity levels.

- Equipment Health: Vibration and diagnostics of handling machinery.

- Exception Alerts: Automated flags for deviations from normal operating thresholds.

Q3: Our GIS shows inconsistent or outdated biomass source location data. How can we fix this? Inconsistent data is a common GIS challenge [40]. Implement a data validation and standardization protocol. For biomass sourcing, establish clear data collection standards for all suppliers and perform regular audits of location data against satellite imagery or recent land surveys.

Q4: We face connectivity issues with IoT devices in remote biomass collection areas. What solutions exist? Remote connectivity challenges can be solved by [41]:

- Selecting a connectivity partner with robust multi-carrier global coverage.

- Using devices that support multiple network types (cellular, LPWAN).

- Implementing a platform that can gracefully handle intermittent connectivity and synchronize data when connections are restored.

Q5: How can we securely manage hundreds of IoT devices across our biomass supply chain? A robust IoT device management platform is crucial [42]. This should include:

- Secure device authentication and onboarding.

- Remote configuration and control capabilities.

- Continuous monitoring and diagnostics.

- Over-the-air (OTA) software and firmware update mechanisms.

Common IoT Connectivity Issues and Solutions

Table 1: IoT Connectivity Challenges in Biomass Logistics

| Challenge | Impact on Biomass Operations | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Network Coverage in Rural Areas [41] | Inability to track feedstock location and condition from remote sources | Deploy multi-carrier IoT devices; consider LPWAN (Low-Power Wide-Area Network) technologies like Sigfox [42] |

| Difficulty Managing Multiple Carrier Contracts [41] | Complex logistics and increased costs for wide-area operations | Partner with a single IoT provider that has pre-negotiated global multi-carrier coverage [41] |

| Device Security Vulnerabilities [41] | Risk of data tampering or system compromise | Use inherently more secure cellular networks over Wi-Fi; implement robust device authentication [41] [42] |

| Power Management for Long-Duration Transport | Sensor failure during critical logistics phases | Select low-power devices and optimize data transmission frequency to extend battery life |

Common GIS Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Table 2: GIS Implementation Challenges in Biomass Logistics

| Challenge | Impact on Biomass Logistics | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Prohibitive Cost [40] | Limits adoption, especially for smaller operations | Seek cloud-based, SaaS GIS solutions with scalable pricing instead of large upfront investments [40] |

| Inconsistencies in Data [40] | Poor decision-making due to unreliable maps | Implement automated data validation checks and establish clear data governance protocols [40] |

| Lack of Standardization [40] | Confusing visualizations and difficulty comparing regions | Create an internal style guide defining colors, icons, and data layers for consistent mapping [40] |

| Siloed Data Systems [40] | Inability to get a unified view of the entire supply chain | Use a GIS platform that can integrate data from multiple sources (IoT, ERP, supplier data) into a single map [40] |

Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Digital Tools for Biomass Logistics Research

| Tool Category | Example Products/Solutions | Specific Function in Biomass Research |

|---|---|---|

| IoT Device Management Platforms | Cisco Kinetic, Bosch IoT Suite [42] | Remotely monitor and control all sensors deployed across the biomass supply chain. |

| Industrial IoT Platforms | GE Predix [42] | Analyze machinery data to optimize biomass processing equipment performance and predict maintenance. |

| LPWAN Connectivity Solutions | Sigfox, Helium [42] | Enable long-range, low-power communication for sensors in remote biomass storage sites. |

| GIS Software Platforms | FuseGIS [40] | Map and analyze geographic data related to biomass sources, transport routes, and facility locations. |

| Fleet Management Solutions | Samsara [42] | Track biomass transport vehicles in real-time to optimize routes and monitor driver behavior. |

| Environmental Sensors | Omron's health monitoring devices (adapted) [42] | Track temperature, humidity, and other factors in biomass storage to prevent spoilage. |

Experimental Protocol: System Integration Test

Objective: To validate the integrated functionality of IoT sensors and GIS platform for monitoring biomass storage conditions.

Methodology:

- Sensor Deployment: Place at least three IoT sensor units in a biomass storage facility (e.g., silo, bale storage), ensuring coverage of different areas (top, middle, bottom layers) [39].

- Baseline Configuration: In the GIS platform, set acceptable threshold values for temperature and humidity specific to the stored biomass type.

- Data Integration: Configure the IoT platform to transmit sensor data (ID, GPS location, temperature, humidity, timestamp) to the GIS via a secure API every 15 minutes [42].

- Anomaly Simulation: Introduce a controlled change in storage conditions (e.g., use a localized heat source to slightly raise the temperature near one sensor).