Optimizing Biomass-to-Energy Conversion: A Roadmap for Enhanced Efficiency, Integration, and Sustainability

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern strategies for optimizing biomass-to-energy conversion processes.

Optimizing Biomass-to-Energy Conversion: A Roadmap for Enhanced Efficiency, Integration, and Sustainability

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of modern strategies for optimizing biomass-to-energy conversion processes. It synthesizes foundational principles, advanced methodological applications, systematic troubleshooting, and rigorous validation frameworks essential for researchers and scientists. The content explores the integration of artificial intelligence for process optimization, the role of spatial planning in supply chain efficiency, and comparative assessments of thermochemical and biochemical pathways. By addressing key challenges and presenting data-driven optimization techniques, this review serves as a strategic guide for advancing biomass conversion technologies toward greater economic viability and environmental sustainability in the global energy landscape.

Biomass Conversion Fundamentals: Principles, Technologies, and Global Significance

Biomass, defined as the biological material from living or recently living organisms, is a cornerstone in the global transition towards sustainable and renewable energy systems [1]. Its pivotal role in reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and countering the critical crisis of global warming necessitates a systematic understanding of its diverse sources [1]. Biomass feedstocks represent a category of renewable resources that can be utilized directly as a fuel or converted into another form of energy product [2]. A comprehensive and optimized biomass-to-energy conversion process begins with the precise characterization and selection of appropriate feedstocks, which directly impacts the efficiency, economic viability, and environmental footprint of the resulting bioenergy [1]. This document details the classification of biomass resources and provides standardized protocols for their analysis, serving as a critical component within a broader research framework aimed at optimizing biomass conversion processes.

Biomass feedstocks can be broadly categorized based on their origin and inherent properties. The U.S. Department of Energy recognizes several key types, each with distinct characteristics and implications for the supply chain and conversion pathway selection [2]. The quantitative data on the global biomass market, valued at USD 134.76 billion in 2022 and projected to exceed USD 210.5 billion by 2030, underscores the economic significance of these feedstocks [1].

Table 1: Primary Categories of Biomass Feedstocks for Energy Conversion

| Feedstock Category | Key Examples | Characteristics & Advantages | Common Conversion Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dedicated Energy Crops | Switchgrass, Miscanthus, Hybrid Poplar, Willow [2] | Grown on marginal land; do not compete directly with food crops; improve soil and water quality [2]. | Gasification, Pyrolysis, Briquetting [3] |

| Agricultural Residues | Corn Stover, Wheat Straw, Barley Straw, Sorghum Stubble [2] | Abundant and widely distributed; generates additional revenue for farmers; utilizes existing waste streams [2]. | Anaerobic Digestion, Gasification [1] [3] |

| Forestry Residues | Logging Residues (limbs, tops), Culled Trees, Thinnings [2] | Reduces forest fire risk and aids restoration; utilizes otherwise unmerchantable material [2]. | Gasification, Pyrolysis [1] |

| Wood Processing Residues | Sawdust, Bark, Branches [2] | Convenient and low-cost as they are already collected at processing sites [2]. | Gasification, Pyrolysis [1] |

| Sorted Municipal Solid Waste | Food Wastes, Yard Trimmings, Paper, Textiles [2] | Diverts waste from landfills; solves waste-disposal problems [2]. | Anaerobic Digestion, Gasification [3] |

| Wet Waste | Manure, Biosolids, Food Processing Waste [2] | Transforms problematic waste streams into energy; produces biogas rich in methane [2]. | Anaerobic Digestion [3] |

| Algae | Microalgae, Macroalgae (Seaweed), Cyanobacteria [2] | High productivity; can grow in saline or wastewater; high lipid content [2]. | Biochemical Conversion, Thermochemical Conversion [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomass Characterization

Accurate characterization of biomass feedstocks is foundational for determining, designing, and optimizing their properties for end-uses in the bioeconomy [4]. The following protocols, adapted from standardized Laboratory Analytical Procedures (LAPs) maintained by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and the Feedstock-Conversion Interface Consortium (FCIC), ensure reproducible and high-quality data [4] [5].

Protocol: Compositional Analysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass

Objective: To quantitatively determine the structural carbohydrate, lignin, and ash content of a lignocellulosic biomass sample.

Principle: This method involves a two-stage sulfuric acid hydrolysis to break down polymeric carbohydrates into monomeric sugars, which are then quantified. The acid-insoluble residue is measured as Klason lignin [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- Milled biomass sample (particle size ≤ 1 mm)

- 72% (w/w) Sulfuric Acid (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„)

- Deionized Water

- Analytical Balance (accuracy ± 0.1 mg)

- Forced-air Oven

- Muffle Furnace

- Autoclave or Hot Bath

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system

Procedure:

- Moisture Content Determination: Pre-dry a separate sample aliquot at 105°C until constant weight to determine the dry weight of the biomass.

- Primary Hydrolysis: Precisely weigh 300.0 mg (± 0.1 mg) of dry biomass into a pressure tube. Add 3.00 mL of 72% H₂SO₄. Incubate in a water bath at 30°C for 60 minutes, stirring every 5-10 minutes.

- Secondary Hydrolysis: Dilute the acid mixture to 4% (w/w) concentration by adding 84 mL of deionized water. Seal the tube and place it in an autoclave at 121°C for 1 hour.

- Filtration and Solid Residue Analysis: After cooling, vacuum-filter the hydrolysis slurry through a pre-weighed coarse porosity crucible. Wash the solid residue with deionized water until the filtrate is neutral. Dry the crucible at 105°C and weigh to determine the acid-insoluble lignin. Ash the crucible in a muffle furnace at 575°C to determine the ash content.

- Liquid Filtrate Analysis: Analyze the liquid filtrate using HPLC to quantify the monomeric sugars (glucose, xylose, arabinose, etc.). The sugar concentrations are used to calculate the polymeric carbohydrate content (e.g., glucan, xylan).

Protocol: Higher Heating Value (HHV) Determination

Objective: To measure the total caloric content of a biomass feedstock using a bomb calorimeter.

Principle: A known mass of biomass is combusted in a high-pressure oxygen atmosphere within a sealed vessel (bomb). The heat released from combustion is absorbed by a known mass of water, and the resulting temperature rise is used to calculate the energy content.

Materials and Reagents:

- Benzoic acid (calorific standard)

- Pellet press

- Oxygen bomb calorimeter system

- Ignition fuse wire

Procedure:

- Calibration: Calibrate the calorimeter by combusting a certified benzoic acid pellet and determining the energy equivalent of the calorimeter (J/°C).

- Sample Preparation: Press approximately 1.0 g of the dry, milled biomass into a pellet.

- Combustion: Weigh the pellet precisely and place it in the sample cup along with a fuse wire. Assemble the bomb, charge it with pure oxygen to 25 atm, and submerge it in the calorimeter's water jacket.

- Measurement: After temperature equilibrium is reached, ignite the sample. Record the precise temperature change of the water.

- Calculation: Calculate the Higher Heating Value (HHV) in MJ/kg using the calibrated energy equivalent and the measured temperature rise, correcting for fuse wire contribution and acid formation.

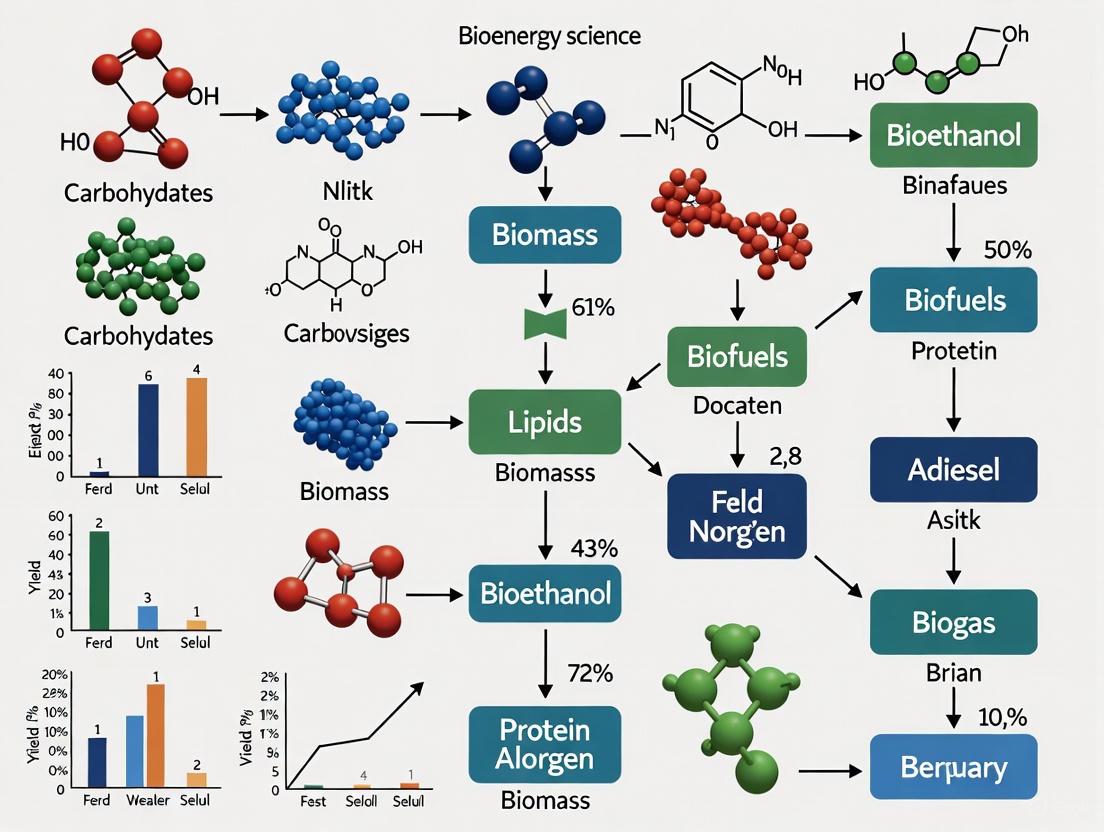

Workflow Visualization for Biomass Characterization and Conversion

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow from biomass feedstock selection to final energy product, highlighting the critical characterization and decision points.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful biomass characterization and conversion research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and equipment. The following table details key solutions and materials essential for the protocols described in this document.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomass Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfuric Acid (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„), 72% | Primary reagent for the acid hydrolysis of structural carbohydrates in the compositional analysis protocol [4]. | High purity is required for reproducible results. Must be handled with extreme care using appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE). |

| Laboratory Analytical Procedures (LAPs) | A suite of standardized methods for the comprehensive characterization of biomass feedstocks and process intermediates [4]. | Maintained by NREL; ensures data comparability across different laboratories and studies. |

| System Color Keywords | Used in data visualization and software interfaces to ensure accessibility and sufficient color contrast for all users [6] [7]. | Critical for creating inclusive scientific presentations and tools; enforced in high-contrast modes. |

| Certified Calorimetry Standards (e.g., Benzoic Acid) | Used to calibrate bomb calorimeters for the accurate determination of biomass Higher Heating Value (HHV) [4]. | Must be of certified purity and known energy content to ensure measurement traceability and accuracy. |

| Chromatography Standards (e.g., Sugar Monomers) | Pure compounds used to calibrate HPLC systems for the quantification of sugars released during biomass hydrolysis [4]. | Enables precise identification and quantification of individual sugar components in complex hydrolysates. |

| UCM710 | UCM710, MF:C19H34O3, MW:310.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| CALP1 | CALP1, MF:C40H75N9O10, MW:842.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Optimization: The Role of Artificial Intelligence

The optimization of biomass-to-energy conversion processes is being revolutionized by Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML). AI models such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Genetic Algorithms (GA) can analyze complex, non-linear relationships within conversion processes like anaerobic digestion, gasification, and pyrolysis [3]. These tools are instrumental in predictive modeling, real-time parameter adjustment, and scenario analysis, leading to enhanced methane yields, optimized syngas composition, and minimized environmental emissions [3]. The integration of AI facilitates the development of robust and efficient energy infrastructures by moving beyond traditional trial-and-error approaches, thereby addressing key challenges in the scalability and economic viability of biomass energy systems [1] [3].

Application Note: Life Cycle Assessment for Biomass-to-Energy Conversion

Within the broader research on optimizing biomass-to-energy conversion processes, conducting a systematic Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is paramount for quantifying the environmental benefits and trade-offs of different technological pathways. The LCA framework provides a comprehensive methodology for evaluating the carbon neutrality of biomass energy systems, from feedstock acquisition to end-use, ensuring that strategic decarbonization efforts are based on robust scientific analysis [8] [9]. This application note outlines standardized protocols for executing such assessments, enabling researchers to generate comparable and reliable data on the environmental impacts of biomass conversion technologies, including emerging pathways like Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) and sustainable aviation fuels [8].

Quantitative Environmental Impact Profiles

A holistic LCA moves beyond a singular focus on Global Warming Potential (GWP) to include a broad suite of environmental impact categories. This is critical for avoiding problem-shifting, where solving one environmental issue inadvertently exacerbates another [8] [9]. The following table summarizes key impact categories and representative findings from biomass system analyses, though results are highly sensitive to feedstock, technology, and regional context.

Table 1: Key Environmental Impact Categories for Biomass Energy LCA

| Impact Category | Description | Exemplary Biomass System Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | Net greenhouse gas emissions (COâ‚‚, CHâ‚„, Nâ‚‚O) over the life cycle. | Can be carbon-negative when BECCS is applied; highly dependent on supply chain and biogenic carbon accounting [8] [10]. |

| Acidification Potential | Emissions of acidifying gases (SOâ‚‚, NOâ‚“). | Can result from combustion processes; levels depend on fuel nitrogen content and emission control technology [8]. |

| Eutrophication Potential | Nutrient over-enrichment in water bodies. | Often linked to agricultural runoff from energy crop cultivation and fertilizer use [8]. |

| Photochemical Oxidant Formation | Potential for smog formation from volatile organic compounds. | Associated with volatile release during combustion and feedstock processing [8]. |

| Water Consumption | Total water withdrawn and consumed. | Varies significantly with feedstock type (e.g., irrigated crops vs. forest residues) and conversion technology [8]. |

| Land Use | Impacts related to land transformation and occupation. | Includes direct and indirect land-use change effects, which can significantly alter the carbon balance [8]. |

LCA Procedural Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standardized, iterative workflow for conducting an LCA of biomass-to-energy conversion systems, aligning with international standards (ISO 14040/14044).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Biomass Feedstock Compositional Analysis

Objective: To quantitatively determine the chemical composition of raw biomass feedstocks, which is a critical first step in understanding conversion efficiency and product yields [11].

Principle: This protocol uses a series of wet chemical analyses to fractionate and quantify the major components of lignocellulosic biomass, including structural carbohydrates, lignin, ash, and extractives, to achieve a summative mass closure [11].

Materials:

- Analytical Balance (precision ± 0.1 mg)

- Forced-Air Oven (105°C)

- Muffle Furnace (capable of 550-600°C)

- Water Bath (30°C ± 1°C)

- Autoclave (for operation at 121°C)

- Vacuum Filtration System with crucibles

- High-Pressure Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system equipped with a refractive index detector and appropriate column (e.g., Aminex HPX-87H)

- Biomass Samples, milled and sieved to a uniform particle size (e.g., 20-80 mesh).

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Determine the moisture content of the biomass by drying a representative sample at 105°C until constant weight. Mill and sieve the dried biomass to achieve a uniform particle size for analysis [11].

- Ash Content: Incinerate a known weight of the dried sample in a muffle furnace at 550-600°C for a minimum of 4 hours. Report the residual ash as a percentage of the dry sample weight [11].

- Extractives Content: Subject the dried biomass to sequential extraction with water and ethanol using a Soxhlet apparatus or similar. Dry the extracted biomass and report the mass loss as a percentage of extractives [11].

- Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin: a. Two-Stage Acid Hydrolysis: Add 72% sulfuric acid to the extractives-free biomass and incubate in a 30°C water bath with stirring for 1 hour. Subsequently, dilute the acid to 4% concentration with deionized water and hydrolyze in an autoclave at 121°C for 1 hour [11]. b. Filtration and Lignin Quantification: Filter the hydrolysate using a vacuum filtration system. The solid residue is the Acid-Insoluble Lignin (AIL), which is dried and weighed. The Acid-Soluble Lignin (ASL) is determined by measuring the UV absorbance of the liquid hydrolysate at 240 nm [11]. c. Sugar Quantification: The liquid hydrolysate is neutralized and analyzed via HPLC to quantify the monomeric sugars (glucose, xylose, arabinose, etc.). These sugar concentrations are converted to their polymeric forms (glucan, xylan, etc.) using anhydro corrections [11].

Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage of each component (glucan, xylan, lignin, ash, extractives) on a dry weight basis. The summative mass closure should approach 100%, validating the analytical procedure.

Protocol 2: Macro-Thermogravimetric Analysis of Biomass Conversion

Objective: To simulate and study the devolatilization and combustion behavior of large, thermally thick biomass particles under controlled, isothermal conditions, bridging the gap between fundamental kinetics and reactor-scale performance [12].

Principle: A macro-thermogravimetric reactor continuously monitors the mass loss of a centimeter-scale biomass particle under a controlled atmosphere and temperature, providing data on conversion rates and profiles relevant to industrial grate-fired boilers [12].

Materials:

- Macro-Thermogravimetric Reactor: A purpose-built system capable of housing large particles (e.g., 8-16 mm chips) and recording real-time mass loss [12].

- Gas Supply System: For delivering controlled atmospheres (e.g., Nâ‚‚, air, Oâ‚‚/Nâ‚‚ mixtures).

- Gas Analyzer: For online analysis of major gaseous products (e.g., CO, COâ‚‚, CHâ‚„) via FTIR or similar techniques [12].

- Temperature Controller: For precise maintenance of isothermal reactor conditions (e.g., 600-800°C).

- Biomass Feedstock: Wood chips (e.g., eucalyptus, pine) prepared and sieved to a specific size class (e.g., 8-16 mm) [12].

Procedure:

- Reactor Setup: Set the macro-TGA reactor to the desired isothermal temperature (e.g., 700°C) and purge with an inert gas (N₂) to establish an oxygen-free environment.

- Baseline Measurement: Tare the mass measurement system at the target temperature.

- Sample Introduction: Rapidly introduce a single, pre-weighed biomass particle into the hot zone of the reactor and start data acquisition.

- Mass Loss Recording: Continuously record the mass of the sample throughout the devolatilization and char combustion stages until mass stabilization.

- Gas Analysis: Simultaneously, sample the gaseous effluent from the reactor and analyze the composition (CO, COâ‚‚, etc.) over the duration of the experiment [12].

- Replication: Repeat the experiment at different temperatures and atmospheric conditions (e.g., in air) to study their effect on conversion rates and products.

Data Analysis: Plot mass loss versus time to determine devolatilization rates. Correlate the release profiles of major gaseous species with the mass loss data to understand reaction pathways. Compare the behavior of different biomass feedstocks under identical conditions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for conducting the compositional analysis and conversion studies described in the protocols above.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Biomass Conversion Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfuric Acid (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Primary catalyst for the two-stage acid hydrolysis in compositional analysis. | High purity (ACS grade), 72% w/w and 4% w/w concentrations [11]. |

| HPLC Standards | Calibration and quantification of sugars and degradation products in hydrolysates. | Certified reference materials for glucose, xylose, arabinose, furfural, hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), acetic acid [11]. |

| HPLC Columns | Separation of sugar monomers and oligomers in liquid samples. | Biorad Aminex HPX-87H column or equivalent, designed for carbohydrate analysis [11]. |

| De-ashing Cartridges | Pretreatment of hydrolysate samples to remove interfering ions prior to HPLC analysis. | Cartridges compatible with the HPLC system; required to eliminate false signals in refractive index detection [11]. |

| Certified Reference Biomass | Quality control and method validation for compositional analysis. | Standard reference materials (e.g., from NIST) with known composition to ensure analytical accuracy [11]. |

| Inert & Reactive Gases | Creating controlled atmospheres for macro-TGA and other conversion experiments. | High-purity Nitrogen (Nâ‚‚) for inert conditions; compressed Air or Oâ‚‚/Nâ‚‚ mixtures for oxidative conditions [12]. |

| (Rac)-Minzasolmin | (Rac)-Minzasolmin, MF:C23H31N5OS, MW:425.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (S,R,S)-Ahpc-O-CF3 | (S,R,S)-Ahpc-O-CF3, MF:C23H29F3N4O4S, MW:514.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The depletion of fossil fuels and the urgent need to mitigate climate change have intensified research into renewable energy sources. Biomass, as a renewable and carbon-neutral resource, plays a pivotal role in this transition, offering a sustainable alternative for producing fuels and value-added products [13]. The conversion of biomass, particularly agricultural and waste biomass, into bioenergy is achieved primarily through two distinct pathways: thermochemical and biochemical conversion. These technologies transform lignocellulosic materials, composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, into a spectrum of energy products including biogas, syngas, bio-oil, biochar, and bioethanol [13] [14]. The selection between thermochemical and biochemical processes depends on feedstock characteristics, desired end products, and economic and environmental considerations. This article provides a detailed comparison of these core pathways, supported by quantitative data, standardized protocols, and visual workflows, to inform research and development in optimized biomass-to-energy conversion.

Comparative Analysis of Conversion Pathways

Thermochemical Conversion

Thermochemical conversion utilizes heat and chemical processes to break down biomass in controlled environments with limited or no oxygen. Key technologies in this pathway include pyrolysis, gasification, and hydrothermal processes.

Pyrolysis involves the thermal decomposition of biomass at temperatures typically between 350–700 °C in the complete absence of oxygen, producing bio-oil, biochar, and syngas. Fast pyrolysis (450–600 °C with short vapor residence times <2 s) maximizes bio-oil yield, while slow pyrolysis favors biochar production [15].

Gasification converts biomass into a mixture of combustible gases—primarily hydrogen (H₂), carbon monoxide (CO), and methane (CH₄)—by reacting the feedstock at high temperatures (700–1000 °C) with a controlled amount of oxygen and/or steam [13] [15].

Hydrothermal processes, such as Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) and Hydrothermal Carbonization (HTC), are suitable for high-moisture feedstocks. HTL operates at 200–450 °C and pressures of 10–25 MPa to produce biocrude, while HTC, conducted at lower temperatures (180–230 °C), converts wet biomass into hydrochar [15].

Biochemical Conversion

Biochemical conversion relies on microorganisms and enzymes to metabolize biomass components under mild conditions, primarily yielding biogas and liquid biofuels.

Anaerobic Digestion (AD) is a series of biological processes where microorganisms break down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen. The process occurs in four stages—hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis—producing biogas (a mixture of CH₄ and CO₂) and digestate [13] [15].

Syngas Fermentation (SNF) is a hybrid process where syngas from gasification is fermented by acetogenic bacteria (e.g., Clostridium species) using the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway. This process converts CO, CO₂, and H₂ into ethanol, butanol, and other chemicals under milder conditions (30–40 °C) compared to catalytic synthesis [15].

Table 1: Operational Parameters and Product Yields of Major Conversion Technologies

| Conversion Process | Temperature Range (°C) | Pressure Conditions | Primary Products | Typical Yields |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fast Pyrolysis | 450 – 600 [15] | Atmospheric [15] | Bio-oil, Biochar, Syngas | Maximizes bio-oil [15] |

| Slow Pyrolysis | 350 – 700 [15] | Atmospheric [15] | Biochar, Bio-oil, Syngas | Higher biochar yield [15] |

| Gasification | 700 – 1000 [15] | Atmospheric [15] | Syngas (H₂, CO, CH₄) | N/A |

| Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL) | 200 – 450 [15] | 10 – 25 MPa [15] | Biocrude | Higher H₂ content, lower O₂ than pyrolysis oil [15] |

| Anaerobic Digestion (AD) | Mesophilic: ~35 [15] | Atmospheric | Biogas (CHâ‚„, COâ‚‚), Digestate | N/A |

| Syngas Fermentation | 30 – 40 [15] | Atmospheric [15] | Ethanol, Butanol | N/A |

Table 2: Financial and Environmental Performance Comparison (Based on NREL Process Models) [16]

| Performance Metric | Thermochemical Pathway | Biochemical Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Feedstock | Pine (low ash) [16] | Sweet Sorghum (low lignin) [16] |

| Challenging Feedstock | Switchgrass (high ash) [16] | Loblolly Pine (high lignin) [16] |

| Relative GHG Emissions | Somewhat lower per MJ of fuel [16] | Higher than thermochemical [16] |

| TRACI Single Score Impacts | Lower [16] | Higher [16] |

| Financial Performance | Highest with pine feedstock [16] | Highest with sweet sorghum [16] |

| Key Limitation | High processing costs, temperature requirements [14] | Long processing times, low product yields [14] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Biomass Feedstock Pre-Treatment and Compositional Analysis

Objective: To prepare and characterize the chemical composition of lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., wheat straw, corn stover) for conversion processes by determining the relative proportions of structural components [4].

Materials:

- Lignocellulosic Biomass: Air-dried and milled to a particle size of <2 mm.

- Reagents: Deionized water, sulfuric acid (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„, 72% w/w and 4% w/w), ethanol, acetone.

- Equipment: Analytical balance, Soxhlet extraction apparatus, forced-air oven, muffle furnace, Ankom Fiber Analyzer or similar system for detergent fiber analysis, HPLC system for sugar analysis.

Procedure:

- Biomass Milling and Sieving: Mill the biomass sample using a knife mill and sieve to achieve a homogeneous particle size of 0.5-2 mm.

- Extractive Removal: Place 2-5 g of biomass (Wextractive) into a cellulose thimble. Perform Soxhlet extraction with a 2:1 (v/v) ethanol-toluene mixture or 95% ethanol for 6-8 hours. Air-dry the extracted biomass overnight, followed by oven-drying at 105°C for 4-6 hours. Cool in a desiccator and weigh (Wextracted).

- Structural Carbohydrate and Lignin Analysis (NREL LAP):

- Acid Hydrolysis: Weigh approximately 300 mg (W_sample) of extractive-free biomass into a pressure tube. Add 3.0 mL of 72% H₂SO₄, stir, and incubate in a water bath at 30°C for 60 minutes. Dilute the acid to 4% by adding 84 mL deionized water, seal the tube, and autoclave at 121°C for 1 hour.

- Filtration and Gravimetric Lignin: After hydrolysis, vacuum filter the solution through a pre-weighed crucible (Wcrucible). Wash the solid residue with deionized water until neutral pH, then dry at 105°C to constant weight (Washless). Ash the crucible in a muffle furnace at 575°C for 4-6 hours to determine acid-insoluble lignin by mass difference and ash content.

- Sugar Analysis by HPLC: Collect the filtrate and neutralize with calcium carbonate. Analyze the supernatant using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography equipped with a refractive index detector and a suitable column to quantify monomeric sugars (glucose, xylose, arabinose, etc.).

Calculations:

- % Extractives = [(Wextractive - Wextracted) / W_extractive] × 100

- % Acid-Insoluble Lignin = [(Washless - Wcrucible - Wash) / Wsample] × 100

- % Structural Carbohydrates: Calculate from HPLC sugar concentrations, applying anhydrous corrections (e.g., glucose × 0.9 for cellulose).

Protocol: Fast Pyrolysis for Bio-Oil Production

Objective: To convert lignocellulosic biomass into bio-oil via fast pyrolysis in a bench-scale fluidized bed reactor [15].

Materials:

- Pre-treated Biomass: Feedstock from Protocol 3.1, dried to <10% moisture.

- Reactor System: Fluidized bed reactor (e.g., 2" diameter), equipped with a biomass feeder, temperature controllers, and a condensation train.

- Fluidizing Gas: Nitrogen (Nâ‚‚), high purity.

- Bed Material: Inert sand (e.g., 300-400 μm particle size).

- Condensation System: Multiple condensers cooled by a mixture of dry ice and isopropanol (-70 to -80°C), electrostatic precipitator.

- Gas Collection: Tedlar bags or a gas meter.

Procedure:

- Reactor Preparation: Load the reactor with sand. Seal the system and perform a leak test. Set the fluidized bed temperature to 500 °C. Initiate N₂ flow to fluidize the sand bed at a predetermined rate.

- Biomass Feeding: Once stable temperature and fluidization are achieved, start the biomass feeder. Feed the milled biomass at a steady rate (e.g., 100-500 g/h) to achieve a high heating rate and short vapor residence time (<2 seconds).

- Product Collection: Direct the produced vapors and gases through the series of condensers to collect the liquid bio-oil. Use an electrostatic precipitator to capture aerosol droplets. Collect the non-condensable gases in gas bags. Note that solid biochar will be retained in the reactor or a subsequent cyclone.

- Product Separation and Quantification: Weigh the collected bio-oil from each condenser. Measure the volume and composition of the syngas using gas chromatography. Recover and weigh the biochar from the reactor and cyclone.

Calculations:

- Bio-oil Yield (wt%) = [Mass of bio-oil collected / Mass of dry biomass fed] × 100

- Biochar Yield (wt%) = [Mass of biochar collected / Mass of dry biomass fed] × 100

- Syngas Yield (wt%) = [Mass of syngas (calculated from composition) / Mass of dry biomass fed] × 100

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

Diagram Title: Biomass Conversion Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biomass Conversion Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfuric Acid (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Catalyst in dilute-acid pre-treatment; reagent for compositional analysis (72% for hydrolysis) [16] [4]. | High purity (ACS grade). Handling requires care due to corrosivity. |

| Cellulolytic & Xylanolytic Enzymes | Biological catalysts for hydrolyzing cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars in biochemical pathways [13] [17]. | From fungi (e.g., Trichoderma reesei) or bacteria. Activity (e.g., FPU/mL) must be standardized. |

| Molybdenum (Mo) Catalysts | Catalytic synthesis of mixed alcohols from syngas in thermochemical processes [16] [18]. | Effective for CO hydrogenation. Research focuses on improving selectivity and resistance to poisoning. |

| Anaerobic Digestion Inoculum | Source of microbial consortium (hydrolytic, acidogenic, acetogenic, methanogenic bacteria) for initiating/reactivating AD processes [15]. | Typically obtained from active anaerobic digesters treating similar waste streams. |

| Acetogenic Bacteria (e.g., Clostridium ljungdahlii) | Biological agents for syngas fermentation via the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, converting CO/COâ‚‚/Hâ‚‚ to ethanol and acetate [15]. | Require strict anaerobic culture conditions. |

| Biochar | Additive in Anaerobic Digestion to stabilize microbial communities, buffer pH, and improve electron transfer, boosting methane yield [15]. | Sourced from pyrolysis. Properties (surface area, porosity) are function of production conditions. |

| Zeolite Catalysts (e.g., ZSM-5) | Catalytic upgrading of pyrolysis vapors to deoxygenate bio-oil and improve its stability and heating value [17]. | Shape-selective catalysts. prone to coke deactivation. |

| Laboratory Analytical Procedures (LAPs) | Standardized protocols from NREL for biomass compositional analysis, ensuring reproducibility and accuracy [4]. | Found in NREL publications. Cover analysis of carbohydrates, lignin, extractives, and more. |

| (Rac)-BRD0705 | (Rac)-BRD0705, MF:C20H23N3O, MW:321.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lenalidomide-C6-Br | Lenalidomide-C6-Br, MF:C20H24BrN3O4, MW:450.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The optimization of biomass-to-energy conversion processes is a cornerstone of the global transition to a sustainable energy system. For researchers and scientists focused on process engineering, a precise understanding of the geographic distribution of biomass resources and their inherent characteristics is paramount. This application note provides a systematic, data-driven overview of global biomass potential, detailing regional variations and feedstock availability to inform experimental design and technology development for biomass valorization. The data synthesized here serves as a critical input for streamlining conversion protocols, from initial feedstock selection to final bioenergy output, within the broader context of a circular bioeconomy.

Global biomass potential is not uniformly distributed; it is shaped by regional climatic conditions, agricultural practices, industrial activity, and policy frameworks. The following analysis breaks down the key biomass-rich regions and their dominant feedstock profiles.

Table 1: Global Biomass Feedstock Analysis by Region

| Region | Estimated Market Share (2025) | Dominant Feedstock Types | Key Drivers & Regional Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia-Pacific | 44.5% [19] | Agricultural residues (e.g., rice husk, sugarcane bagasse), wood residues [19] | Escalating energy demand, supportive government policies, rapid industrialization, and extensive agricultural base [19] [20]. |

| North America | 22.8% (Fastest-growing region) [19] | Wood chips, pellets, agricultural waste, energy crops (e.g., switchgrass) [19] [21] [22] | Strong policy support (e.g., U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard), vast forestry and agricultural resources, and leading-edge technological advancements [19] [20]. |

| Europe | Leading in adoption [23] | Forest waste, agricultural residues, municipal organic waste [21] [22] | Stringent environmental regulations (e.g., EU Renewable Energy Directive), well-developed bioenergy infrastructure, and a strong focus on circular economy principles [19] [20]. |

| Latin America | Notable expertise [19] | Sugarcane bagasse, other agricultural residues [19] [21] | Long-standing bioenergy expertise, favorable agro-climatic conditions, and government biofuel blending mandates [19]. |

The theoretical global biomass potential is vast, with estimates ranging between 200 and 500 Exajoules (EJ) per year, though this is highly dependent on sustainability constraints and assessment methodologies [21]. Terrestrial biomass, comprising forestry residues, agricultural by-products, dedicated energy crops, and municipal organic waste, constitutes the predominant resource [21].

Feedstock Characterization and Conversion Pathways

Different feedstocks possess distinct physicochemical properties that dictate the optimal conversion pathway and pre-treatment protocol. The selection of biomass is a critical first step in designing an efficient conversion process.

Table 2: Feedstock Types, Characteristics, and Preferred Conversion Pathways

| Feedstock Category | Key Examples | Characteristics & Advantages | Recommended Conversion Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wood & Agricultural Residues | Wood chips, straw, rice husks, bagasse [19] [22] | Widespread availability, cost-effectiveness, addresses waste management issues [19]. | Combustion, Gasification, Pyrolysis, Briquetting [3] [22] |

| Dedicated Energy Crops | Switchgrass, Miscanthus [21] | High yield (10-20 tons/hectare annually), superior energy output [21]. | Gasification, Fermentation to Biofuels [21] |

| Aquatic Biomass | Microalgae [21] | High growth rates (20-50 tons/hectare/year), does not compete for arable land [21]. | Biodiesel production, Anaerobic Digestion [21] |

| Organic Waste Streams | Municipal solid waste, animal manure, food waste [21] [22] | Promotes circular economy, mitigates waste disposal issues [19] [22]. | Anaerobic Digestion (biogas), Thermal Conversion [3] |

The wood and agricultural residues segment represents a significant portion of the biomass resource, expected to account for 42.7% of the feedstock market share in 2025 [19]. Meanwhile, solid biomass feedstocks like chips, pellets, and briquettes are seeing growing demand, particularly for power generation and residential heating [22] [20].

Experimental Protocols for Biomass Potential Assessment

Accurate assessment of biomass potential at local and regional scales requires standardized methodologies. The following protocols outline robust procedures for resource evaluation.

Protocol: Bottom-Up Biomass Resource Inventory

Objective: To quantify the theoretical and technically available biomass feedstock within a defined geographic boundary.

- Principle: This method aggregates localized data on crop yields, forest productivity, and waste streams to estimate biomass availability, avoiding the overestimation common in top-down models [21].

- Materials:

- Regional agricultural and forestry production statistics.

- GIS (Geographic Information System) software.

- Crop-specific residue-to-product ratios (RPR).

- Land-use and land-cover maps.

- Procedure:

- Define System Boundaries: Clearly delineate the study area (e.g., country, state, watershed).

- Data Collection: Gather data for the target year on:

- Calculate Residue Generation: For each crop, multiply the production data by its established RPR to determine the total agricultural residue generated [21].

- Apply Availability Factors: Factor in technical, environmental, and socioeconomic constraints to estimate the fraction of total biomass that is realistically available for energy use (e.g., soil conservation needs may leave a portion of residues on land) [21].

- Spatial Mapping (Optional but Recommended): Use GIS to map the geographic distribution of biomass resources, which is critical for logistics and supply chain planning [21].

- Data Analysis: The final output is a quantified inventory, in tons per year, of available biomass feedstocks, segmented by type and location.

Protocol: Integrated Assessment Model (IAM) Analysis

Objective: To project future biomass potential and its role in energy systems under different climate and policy scenarios.

- Principle: IAMs integrate data from energy systems, economics, and land use to provide a holistic view of biomass availability and trade-offs [21].

- Materials:

- IAM software platform (e.g., IMAGE, GCAM, MESSAGE).

- Socioeconomic pathway scenarios (e.g., SSPs).

- Climate policy targets (e.g., RCPs).

- Procedure:

- Scenario Definition: Select or define future scenarios combining different levels of climate policy, economic growth, and technological change.

- Model Parameterization: Input data on current land use, energy demand, and resource potential into the IAM.

- Model Execution: Run the IAM to simulate energy and land-use systems over a multi-decadal timeframe.

- Output Extraction: Extract model outputs related to bioenergy production, land allocation for energy crops, and feedstock mix.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the results to understand how different drivers influence long-term biomass potential and to identify potential trade-offs with food security and biodiversity [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biomass Conversion Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Lignocellulolytic Enzymes | Catalyze the hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars during biochemical conversion [3]. |

| Metal Oxide Nanoparticles & Nanocomposites | Act as catalysts to enhance pre-treatment efficiency and breakdown of recalcitrant structures, particularly in algal and lignocellulosic biomass [21]. |

| Methanogenic Inoculum | Provides the consortium of microorganisms necessary for biogas production via Anaerobic Digestion [3]. |

| Gasification Agents (Oâ‚‚, Steam) | Used as feed gases in thermochemical gasification to partially oxidize biomass into syngas [3]. |

| Torrefaction Reactors | Equipment for mild pyrolysis pre-treatment, improving biomass grindability and energy density [20]. |

| BNS808 | BNS808, MF:C25H20Cl3N3O3S, MW:548.9 g/mol |

| CNX-1351 | CNX-1351, MF:C30H35N7O3S, MW:573.7 g/mol |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for assessing regional biomass potential and selecting appropriate conversion pathways, integrating the protocols and data outlined above.

Assessment Workflow

The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) models, such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and Support Vector Machines (SVMs), is emerging as a powerful tool to optimize conversion parameters (e.g., for anaerobic digestion, gasification) and enhance process yields, thereby improving the overall efficiency of the pathways selected in the workflow above [3].

The Energy Landscape Theory provides a comprehensive framework for understanding and optimizing the spatial dimension of energy systems, particularly the integration of biomass utilization within regional and local planning. This theory posits that energy transitions are not merely technological shifts but profound spatial transformations that require co-optimization of land use, energy infrastructure, and resource management. The theory bridges energy modeling with spatial planning through Geographic Information Science (GIS), remote sensing, spatial disaggregation techniques, and geovisualization [24]. Within this framework, biomass is recognized as a versatile but land-intensive renewable resource that requires careful spatial planning to balance its energy potential against competing land uses and environmental considerations [24] [25]. The deployment of biomass energy infrastructure must navigate complex trade-offs between technical potential, economic feasibility, social acceptance, and environmental protection—challenges that Energy Landscape Theory seeks to address through integrated assessment methodologies.

Background and Principles

Assessing the spatial potential of biomass resources is a foundational application of Energy Landscape Theory. This process involves evaluating theoretical, technical, and economically feasible biomass potentials across a landscape while considering spatial constraints and competing land uses [24]. Biomass possesses a significantly larger spatial footprint than other renewable carriers such as solar energy, making strategic spatial allocation particularly important [24]. This application note outlines a standardized protocol for conducting such assessments, enabling researchers and planners to identify optimal locations for biomass utilization within broader energy systems.

Experimental Protocol: GIS-Based Biomass Potential Mapping

Methodology Summary: This protocol employs a multi-criteria GIS analysis to map biomass availability and suitability across a defined study region.

Table 1: Data Requirements for Spatial Biomass Assessment

| Data Category | Specific Parameters | Data Sources | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass Resources | Agricultural residues, forestry waste, energy crops, organic municipal waste [26] | Agricultural statistics, forestry inventories, waste management reports | Municipal/parcel level |

| Land Use Constraints | Protected areas, prime farmland, flood zones, residential buffers | National land use databases, environmental agencies | ≤ 30m resolution |

| Infrastructure Factors | Road networks, existing energy plants, grid connection points | Transportation departments, energy regulators | Vector line/point data |

| Technical Parameters | Biomass yield coefficients, transport distances, conversion efficiencies [24] | Scientific literature, technology providers | Region-specific |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define Assessment Boundaries: Delineate the study region (e.g., municipal, regional, or national level) and establish a consistent coordinate reference system.

Compile Biomass Inventory: Quantify available biomass feedstocks using the following calculation:

Feedstock Availability (tons/year) = Production Quantity × Residue Generation Ratio × Collectability Factor

- Data should be georeferenced to specific parcels or administrative units [24].

Apply Exclusion Criteria: Identify and map exclusion zones where biomass development is prohibited or severely restricted (e.g., protected areas, steep slopes, urban cores).

Calculate Technical Potential: Apply technology-specific conversion efficiencies to the available biomass, accounting for spatial variability in feedstock characteristics.

Conduct Suitability Analysis: Develop weighted criteria for facility siting (e.g., proximity to roads, grid connections, feedstock sources) and generate suitability maps.

Model Economic Potential: Incorporate transport costs, infrastructure investments, and energy prices to identify economically viable resources [24].

Validate and Ground Truth: Conduct field verification at a sample of high-potential sites to confirm desk study findings.

Visualization: Spatial Assessment Workflow

Diagram 1: Spatial biomass potential assessment workflow for energy landscape planning.

Application Note 2: Optimizing Biomass Allocation Pathways

Background and Principles

Biomass is a limited resource with multiple competing applications across the energy system, including electricity generation, heat production, transportation fuels, and as a carbon source for industrial processes [27]. Energy Landscape Theory provides a framework for prioritizing these uses based on system-level value, particularly when combined with carbon capture technologies (BECC) to enable negative emissions (BECCS) or carbon utilization (BECCU) [27]. Research indicates that the provision of biogenic carbon often has higher value than bioenergy provision alone in decarbonized energy systems [27]. This application note outlines protocols for modeling optimal biomass allocation across sectors.

Experimental Protocol: Sector-Coupled Biomass Allocation Modeling

Methodology Summary: This protocol uses energy system optimization modeling to determine cost-effective biomass allocation pathways across electricity, heat, transport, and industry sectors under emissions constraints.

Table 2: Biomass Conversion Pathways and System Values

| Conversion Pathway | Primary Outputs | System Value Factors | Optimal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomass with CCS (BECCS) | Electricity/Heat + Negative emissions [27] | Carbon removal value, grid stability | High-priority for net-negative targets |

| Biofuel Production | Liquid fuels (aviation, marine) [27] | Limited renewable alternatives in hard-to-electrify sectors | Aviation, shipping, heavy transport |

| Biomass Gasification | Syngas, hydrogen, biofuels [26] [28] | Dispatchable energy, feedstock flexibility | Industrial heat, chemical production |

| Anaerobic Digestion | Biogas, biofertilizer [26] | Waste management, nutrient recycling | Agricultural regions, waste processing |

| Direct Combustion | Heat, electricity [26] | Simplicity, cost-effectiveness | Local heat demand, district energy |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Define System Boundaries: Establish temporal (e.g., hourly, annual) and spatial (e.g., regional, national) boundaries for the analysis.

Characterize Biomass Resources: Quantify available biomass feedstocks by type, energy content, and location using the methods from Application Note 1.

Model Technology Options: Include all relevant conversion technologies with their technical parameters (efficiency, capacity, flexibility), costs (capital, O&M), and carbon balances.

Define Energy Demands: Specify electricity, heat, transport, and industrial feedstock demands across the studied region.

Incorporate Policy Constraints: Implement carbon emissions targets (e.g., net-zero, net-negative) and other relevant policy frameworks.

Run Optimization Scenarios: Use energy system models (e.g., PyPSA-Eur-Sec [27]) to identify cost-optimal biomass allocation under different assumptions.

Conduct Sensitivity Analysis: Test model robustness against variations in key parameters (biomass availability, technology costs, carbon prices).

Explore Near-Optimal Solutions: Identify solution spaces within 1-25% of cost-optimality to understand flexibility in biomass allocation [27].

Visualization: Biomass Allocation Decision Framework

Diagram 2: Decision framework for optimizing biomass allocation across energy sectors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools for Energy Landscape Research

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Analysis Platforms | ArcGIS, QGIS, GRASS [24] | Biomass potential mapping, facility siting | Geospatial data processing, visualization, and analysis |

| Energy System Models | PyPSA-Eur-Sec, TIMES, OSeMOSYS [27] | Sector-coupled energy transition planning | Optimization of technology deployment and resource allocation |

| Machine Learning Libraries | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn [3] | Biomass conversion optimization, yield prediction | Pattern recognition, parameter optimization, predictive modeling |

| Biochemical Analysis | HPLC, GC-MS, NIR Spectroscopy [28] | Biomass characterization, process monitoring | Feedstock composition analysis, conversion product quantification |

| Life Cycle Assessment Tools | OpenLCA, SimaPro, GREET | Environmental impact assessment | Carbon accounting, sustainability metrics calculation |

| Carbon Capture Modeling | Aspen Plus, gCCS | BECCS/BECCU feasibility analysis | Process simulation, techno-economic assessment |

| NMDA agonist 1 | NMDA agonist 1, MF:C12H13N3O3S, MW:279.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Vinconate | Vinconate, CAS:767257-65-8, MF:C18H20N2O2, MW:296.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Application Note 3: AI-Enhanced Biomass Conversion Optimization

Background and Principles

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing the optimization of biomass conversion parameters across various technological pathways [3]. These approaches can analyze complex, non-linear relationships in conversion processes that are difficult to model with traditional statistical methods. AI techniques have demonstrated particular value in optimizing anaerobic digestion, gasification, pyrolysis, and enzymatic hydrolysis processes by identifying optimal operating conditions from large, multi-dimensional datasets [3] [28]. This application note details protocols for implementing AI-driven optimization in biomass conversion research.

Experimental Protocol: Machine Learning for Conversion Process Optimization

Methodology Summary: This protocol employs supervised machine learning algorithms to model biomass conversion processes and identify parameter combinations that maximize product yield and quality while minimizing energy inputs and emissions.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Collection and Curation:

- Compile experimental data on biomass characteristics (proximate/ultimate analysis, particle size), process parameters (temperature, pressure, retention time, catalysts), and output metrics (yield, quality, emissions).

- Clean dataset, handle missing values, and normalize features to prepare for ML processing.

Feature Selection:

- Identify the most influential input parameters using correlation analysis and domain knowledge.

- Reduce dimensionality while retaining predictive power.

Model Selection and Training:

- Test multiple ML algorithms (Artificial Neural Networks, Support Vector Machines, Random Forests) [3].

- Split data into training (70-80%) and testing (20-30%) sets.

- Train models to predict outputs from inputs using the training set.

Model Validation:

- Evaluate model performance on the testing set using metrics (R², RMSE, MAE).

- Compare model predictions against experimental results not used in training.

Process Optimization:

- Use genetic algorithms or other optimization techniques to identify parameter combinations that maximize desired outputs.

- Validate optimized conditions through laboratory-scale experiments.

Implementation:

- Deploy validated models for real-time process control or scale-up planning.

Visualization: AI-Optimized Biomass Conversion Workflow

Diagram 3: AI and machine learning workflow for optimizing biomass conversion processes.

The Energy Landscape Theory provides an essential framework for integrating spatial planning with biomass utilization in the transition to sustainable energy systems. The application notes and protocols presented here offer researchers and practitioners methodologies for assessing spatial biomass potentials, optimizing allocation across sectors, and enhancing conversion efficiencies through advanced computational approaches. Implementation of these protocols requires careful attention to local contexts, including biomass availability, land use constraints, energy system requirements, and policy frameworks. As research in this field advances, particularly through AI integration and improved spatial modeling, Energy Landscape Theory will continue to provide critical insights for balancing biomass utilization with other renewable energy sources and land use priorities in decarbonizing energy systems.

Application Notes: Current State and Quantitative Insights

This section details key performance data and technological focuses in the valorization of biomass for a circular bioeconomy, moving beyond traditional energy applications to high-value bioproducts.

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of Biomass Utilization and Conversion Efficiencies

| Metric | Region/System | Value/Figure | Context & Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forest Biomass in Renewable Energy | European Union | ~66% of total biomass energy [29] | Primary renewable source within the EU's bioeconomy. |

| Biomass in Renewable Energy Mix | Canada | ~18.7% of renewable energy [29] | Woody biomass constitutes the majority of the biomass share. |

| Biomass Power Generation | United States | ~6.7% of renewable electricity [29] | Contribution of woody biomass to the renewable electricity mix. |

| Projected Biomass Potential | Indonesia (by 2050) | 312 Mt (fulfilling 24% energy demand) [30] | National projection highlighting vast potential of waste-derived sources. |

| Technical Biomass Potential | Switzerland | 209 PJ/year [30] | 50% of this potential can be sustainably harnessed. |

| Gasification Process Efficiency | Various Systems | 70% to 85% [30] | Leading pathway in terms of energy yield and CO2 emission reduction. |

| AI-Optimized Methane Yield | Anaerobic Digestion | 28% increase [3] | Achieved via mechanical pretreatment (bead milling) optimized by AI models. |

| Photocatalytic Conversion | ZnIn2S4 System | 94% (furfural), 89% (HMF), 99% (DFF) [31] | Conversion rates of platform chemicals to biofuel additives. |

Table 2: Research Focus and Feedstock Trends in Wood-Based Circular Bioeconomy (2020-2025)

| Category | Primary Finding | Proportion of Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic Focus | European Institutions | 83.4% [29] |

| Primary Feedstock | Wood-Mixed Biomass Waste | 26% [29] |

| Secondary Feedstock | Forest Residues | 23% [29] |

| Technology Readiness | Lab-Scale Technologies | 33% [29] |

| Research Perspective | Technology/Product-Focused | 63% [29] |

| Primary Environmental Driver | Waste Reduction | 34% [29] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: AI-Optimized Anaerobic Co-Digestion for Enhanced Biogas Yield

This protocol outlines a methodology for optimizing biogas production from mixed organic wastes using artificial intelligence (AI), specifically backpropagation neural networks (BPNNs), to predict and control key process parameters [3].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Animal Manure | Primary substrate, providing a base nutrient profile and microbial inoculum. |

| Sewage Sludge | Co-substrate, introduces diverse microbial communities and additional organic matter. |

| Paper Waste | Co-substrate, high carbon content feedstock to balance the Carbon/Nitrogen (C/N) ratio. |

| Macronutrient Solutions | Aqueous solutions of Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), and Sulfur (S) for precise nutrient balancing. |

| pH Buffers (e.g., Sodium Bicarbonate) | To maintain digester stability and counteract Volatile Fatty Acid (VFA) accumulation. |

2. Methodology

2.1. Feedstock Preparation and Characterization:

- Physical Pretreatment: Subject paper waste to mechanical bead milling to reduce particle size, thereby increasing the surface area for microbial attack [3].

- Chemical Characterization: Analyze the initial total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS), and elemental composition (C, N, P, S) of each substrate (animal manure, sewage sludge, and pretreated paper waste) to establish baseline data for the AI model [3].

2.2. Experimental Setup and Inoculation:

- Use multiple lab-scale anaerobic digesters (e.g., 5L working volume) with continuous stirring.

- Maintain a constant mesophilic temperature range of 32–35°C using a water bath or heating jacket [3].

- Inoculate digesters with an active anaerobic sludge.

2.3. AI Model Integration and Process Optimization:

- Data Inputs: Feed the BPNN model with real-time and historical data, including feedstock mixing ratios, C/N ratio, pH, temperature, and hydraulic retention time (HRT) [3].

- Model Training: Train the model with a dataset where the output is the corresponding methane yield and digester stability (measured via VFA-to-alkalinity ratio).

- Process Control: Use the AI model's predictions to automatically adjust the feedstock mixing ratio and the dosing of pH buffers in response to real-time sensor data to prevent VFA accumulation and maximize the specific methane yield [3].

2.4. Monitoring and Analysis:

- Gas Analysis: Continuously monitor the volume and composition (CHâ‚„, COâ‚‚) of the produced biogas using gas meters and gas chromatography.

- Digestate Analysis: Regularly sample the digestate to measure VFA levels, pH, and alkalinity to assess process stability and validate AI predictions.

Protocol: Photocatalytic Upgrading of Biomass Platform Chemicals to Fuel Additives

This protocol describes the photocatalytic acetalization of furfural (FFaL) and 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) into biofuel additives using a ternary metal chalcogenide (ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„) catalyst, which simultaneously produces Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ [31].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„ Photocatalyst | Ternary metal chalcogenide semiconductor; absorbs light, provides acidic sites for acetalization, and generates Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚. |

| Furfural (FFaL) | Biomass-derived platform chemical; primary reactant. |

| 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) | Biomass-derived platform chemical; primary reactant. |

| Ethylene Glycol (EG) | Alcohol reactant for acetalization reaction. |

| Solvent (e.g., Acetonitrile) | Reaction medium. |

2. Methodology

2.1. Photocatalyst Preparation:

- Synthesize ZnIn₂S₄ nanoflakes via a hydrothermal method. Confirm the crystal structure and presence of acidic sites using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and ammonia-temperature-programmed desorption (NH₃-TPD), respectively [31].

2.2. Photocatalytic Reaction Setup:

- In a round-bottom flask, prepare a reaction mixture containing the biomass substrate (e.g., 1 mmol Furfural), solvent, excess ethylene glycol, and the ZnInâ‚‚Sâ‚„ catalyst (e.g., 20 mg).

- Seal the reactor and purge with an inert gas (e.g., Nâ‚‚ or Ar) to remove oxygen.

- Irradiate the mixture under visible light using a suitable LED or Xe lamp with a UV cutoff filter. Maintain constant magnetic stirring.

2.3. Reaction Monitoring and Product Analysis:

- Kinetics: Withdraw aliquots at regular intervals.

- Conversion and Selectivity: Analyze the aliquots using gas chromatography (GC) or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) to determine substrate conversion and product selectivity. Target conversions of 94% for furfural [31].

- Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ Quantification: Measure the concurrent production of Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ using established spectrophotometric methods (e.g., titanium oxalate assay).

2.4. Mechanistic Investigation (Optional):

- Perform controlled experiments with radical scavengers to identify active species.

- Use in situ Electron Paramagnetic Resonance (EPR) and electrochemical studies to corroborate the reaction mechanism and charge carrier dynamics [31].

Protocol: Catalytic Pyrolysis of Lignocellulosic Biomass Using Natural Mineral Catalysts

This protocol details the ex-situ catalytic pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., pulper rejects, microalgae) using low-cost natural mineral catalysts like clinoptilolite to enhance the yield and quality of bio-oil [32].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Primary feedstock (e.g., pulper rejects, forest residues, energy crops). |

| Natural Mineral Catalysts | e.g., Clinoptilolite, Sepiolite, Bentonite; catalyze cracking reactions to deoxygenate bio-oil. |

| Nitrogen Gas (Nâ‚‚) | Inert atmosphere gas to prevent combustion during pyrolysis. |

2. Methodology

2.1. Feedstock and Catalyst Preparation:

- Biomass Preparation: Dry the biomass feedstock (e.g., pulper rejects) to a constant weight and grind to a particle size of 2–5 mm [32].

- Catalyst Activation: Crush the natural mineral (e.g., clinoptilolite) and activate by calcination (e.g., at 500°C for 3 hours) to remove impurities and enhance acidity [32].

2.2. Fixed-Bed Pyrolysis Reactor Setup:

- Use a fixed-bed reactor system consisting of two zones: a biomass pyrolysis zone and a separate, downstream catalytic upgrading zone (ex-situ configuration).

- Load the biomass into the first zone. Place the activated catalyst in a fixed bed in the second zone.

- Purge the entire system with Nâ‚‚ at a flow rate of 50 mL/min to ensure an oxygen-free environment [32].

2.3. Pyrolysis and Catalytic Upgrading:

- Heat the biomass zone to the pyrolysis temperature of 500°C at a fast heating rate.

- The evolved vapors are carried by the Nâ‚‚ gas into the catalytic zone, where they contact the catalyst (e.g., activated clinoptilolite).

- Maintain the catalytic zone at the desired temperature (e.g., 450-500°C) to facilitate cracking and deoxygenation reactions.

2.4. Product Collection and Analysis:

- Condensable Liquids: Use a condenser system downstream of the catalytic zone to collect the upgraded bio-oil. Measure the yield.

- Non-Condensable Gases: Collect the syngas in a gas bag for subsequent volume and composition analysis (e.g., by GC).

- Solid Residue: Measure the yield of biochar remaining in the biomass and catalyst zones.

- Bio-oil Analysis: Characterize the bio-oil for its Higher Heating Value (HHV), oxygen content, and chemical composition to confirm quality improvement [32].

Advanced Conversion Technologies and Implementation Frameworks

Within the broader research objective of optimizing biomass-to-energy conversion processes, thermochemical technologies represent a cornerstone for enhancing efficiency, product yield, and sustainability. Gasification, pyrolysis, and torrefaction are pivotal in transforming diverse biomass feedstocks into a range of energy carriers and valuable products, from electricity and heat to solid biofuels and chemical precursors [33] [34]. These processes are integral to climate change mitigation strategies and the transition toward a circular bioeconomy, as they enable the valorization of agricultural residues, forestry waste, and municipal solid waste [35] [36]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for these key thermochemical conversion pathways, focusing on recent technological advancements and standardized methodologies to support research and development efforts.

Process Fundamentals and Product Spectrum

The selection of a specific thermochemical conversion pathway is dictated by the desired end product, feedstock characteristics, and overall energy efficiency targets.

- Torrefaction: A mild thermochemical pretreatment process conducted at 200–300 °C in an inert or low-oxygen environment. It is primarily used to upgrade raw biomass into a carbon-rich, hydrophobic, and energy-dense solid known as torrefied biomass or "bio-coal" [35] [36]. The solid product exhibits improved grindability and pelletability, making it an superior feedstock for subsequent gasification or co-firing processes [33].

- Pyrolysis: Involves the thermal decomposition of biomass at 300–650 °C in the complete absence of oxygen. Depending on the operating conditions (heating rate, temperature, and residence time), it can be tuned to maximize different products: biochar (slow pyrolysis), bio-oil (fast pyrolysis), or syngas (flash pyrolysis) [33] [37]. The bio-oil produced can be further upgraded into transportation fuels or chemicals.

- Gasification: Converts biomass into a combustible syngas (primarily CO, H₂, CH₄, and CO₂) by reacting the feedstock at high temperatures (700–1500 °C) with a controlled amount of oxygen and/or steam [38]. The syngas can be utilized for power generation, further synthesized into liquid fuels (e.g., methanol, Fischer-Tropsch diesel), or used for hydrogen production [33] [38].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Thermochemical Conversion Processes

| Parameter | Torrefaction | Pyrolysis | Gasification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Range | 200–300 °C [35] [36] | 300–650 °C [37] | 700–1500 °C [38] |

| Atmosphere | Inert or low-oxygen [36] | Absence of oxygen [39] | Controlled oxygen/steam [38] |

| Primary Product | Solid (Torrefied Biomass/Bio-coal) [35] | Liquid (Bio-oil) / Solid (Biochar) [37] | Gas (Syngas) [38] |

| Residence Time | ~1 hour (can vary) [36] | Varies (seconds for fast, hours for slow) [33] | Seconds to minutes [38] |

| Key Application | Solid fuel production, pretreatment [35] | Bio-oil for fuel/chemicals, biochar for soil amendment [37] [39] | Syngas for power, fuel synthesis, hydrogen [33] [38] |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Critical performance metrics provide a basis for techno-economic analysis and process optimization.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics and Efficiencies

| Metric | Typical Range | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Torrefaction Mass Yield | ~80% of dry initial mass [39] | Varies with severity; about 20% mass loss. |

| Torrefaction Energy Yield | ~90% of initial energy [39] | Confirms high energy retention in the solid product. |

| Gasification Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE) | 63–76% [38] | Depends on feedstock and gasifier type (e.g., 76.5% for plywood). |

| Heating Value of Syngas (Air) | 4–7 MJ/Nm³ [38] | Lower heating value (LHV) when air is the gasifying agent. |

| Heating Value of Syngas (O₂/Steam) | 10–18 MJ/Nm³ [38] | Higher heating value (LHV) when using oxygen and steam. |

| Global Biomass Power Capacity (2020) | 122 GW [1] | Led by Asia (66 GW) and Europe (32 GW). |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Laboratory-Scale Biomass Torrefaction

Objective: To produce torrefied biomass with enhanced fuel properties from a selected lignocellulosic feedstock.

Materials:

- Feedstock: Milled and sieved biomass (e.g., wood chips, agricultural residues), moisture content pre-determined.

- Reactor: Fixed-bed or tubular reactor capable of operating up to 300 °C with an inert gas supply (N₂).

- Equipment: Analytical balance, oven for moisture determination, calorimeter for Higher Heating Value (HHV) analysis.

Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: Dry the biomass at 105 °C for 24 hours to determine baseline moisture content. Sieve to obtain a uniform particle size (e.g., 0.5–1.0 mm).

- Reactor Setup: Load a predetermined mass (e.g., 20 g) of dry biomass into the reactor chamber. Seal the system and purge with nitrogen (N₂) at a flow rate of 0.5–1 L/min for 15 minutes to establish an inert atmosphere.

- Process Execution: Heat the reactor to the target torrefaction temperature (e.g., 250 °C, 275 °C, 300 °C) at a controlled heating rate (e.g., 10 °C/min). Maintain the temperature and N₂ flow for a set residence time (e.g., 30 or 60 minutes).

- Product Collection & Quenching: After the residence time, stop the heating and continue Nâ‚‚ flow to cool the solid product. Collect the torrefied biomass and weigh it to determine mass yield.

- Product Analysis:

- Mass Yield (MY): ( MY (\%) = \frac{Mass{torrefied}}{Mass{dry, initial}} \times 100 )

- Energy Yield (EY): ( EY (\%) = MY \times \frac{HHV{torrefied}}{HHV{initial}} \times 100 )

- Analyze the HHV, proximate analysis (moisture, volatiles, ash, fixed carbon), and grindability of the product.

Optimization Note: Pretreatments like water or acid washing can be applied before torrefaction to reduce ash content and improve product quality [35]. Catalytic torrefaction, using catalysts like K₂CO₃ or ZnCl₂, can be employed to alter reaction pathways and enhance efficiency [35].

Protocol: Fixed-Bed Biomass Gasification with Syngas Analysis

Objective: To gasify biomass and analyze the composition and yield of the produced syngas.

Materials:

- Feedstock: Torrefied biomass or raw biomass (pelletized or crushed).

- Reactor: Laboratory-scale downdraft or fluidized-bed gasifier.

- Gasifying Agent: Air, oxygen, or steam supply system with mass flow controllers.

- Analytical Equipment: Online gas chromatograph (GC) with TCD and FID detectors, tar sampling train, gas flow meters.

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Calibrate all gas flow meters and the GC. Load the reactor with biomass feedstock. Ensure all connections are gas-tight.

- Start-up and Stabilization: Purge the reactor with an inert gas. Initiate heating of the reactor to the target gasification temperature (e.g., 800 °C). Once the temperature is stable, introduce the gasifying agent (e.g., air) at a predetermined equivalence ratio (ER, typically 0.2–0.4).

- Syngas Sampling and Analysis: Allow the system to stabilize for 30 minutes. Connect the gas output to the online GC. Collect syngas samples at regular intervals (e.g., every 10 minutes) for at least one hour to ensure data reproducibility.

- Tar Content Determination: Use a standardized tar sampling protocol (e.g., cold solvent trapping) to collect condensable tars from a known volume of syngas. Gravimetric analysis determines the tar concentration (g/Nm³).

- Data Calculation:

- Carbon Conversion Efficiency (CCE): ( CCE (\%) = \frac{Carbon \ in \ syngas}{Carbon \ in \ feedstock} \times 100 )

- Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE): ( CGE (\%) = \frac{LHV{syngas} \times Syngas \ Flow \ Rate}{LHV{feedstock} \times Feedstock \ Feed \ Rate} \times 100 )

Advanced Modeling: For process design, thermodynamic equilibrium models (e.g., using Aspen Plus) or computational fluid dynamics (CFD) can be developed to predict gas composition and reactor performance [38].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Primary feedstock for conversion processes. | Standardize particle size (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mm). Pre-dry to constant mass. Characterize HHV, proximate, and ultimate analysis [40]. |

| Inert Gas (Nâ‚‚ or Ar) | Creates an oxygen-free environment for torrefaction and pyrolysis. | High purity (>99.99%). Flow rate must be controlled and monitored [36]. |

| Gasifying Agents (Oâ‚‚, Air, Steam) | Reactants in the gasification process. | High-purity Oâ‚‚ or steam generators are used. The Equivalence Ratio (ER) is a critical control parameter [38]. |

| Catalysts (e.g., K₂CO₃, ZnCl₂, Dolomite) | Enhance reaction rates, alter product distribution, and reduce tar formation. | Used in catalytic torrefaction [35] or in-situ catalytic gasification/pyrolysis. Loading and dispersion are key. |

| Tar Sampling Train | Quantifies condensable hydrocarbons in syngas. | Typically follows a standard protocol involving cold solvent traps (e.g., isopropanol) and particulate filters [38]. |

| Solid Sorbents | Cleaning and conditioning of product gases (syngas). | Used for removing contaminants like Hâ‚‚S, HCl, and other acid gases [33]. |

| EGCG Octaacetate | EGCG Octaacetate, MF:C38H34O19, MW:794.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| VAV1 degrader-3 | VAV1 degrader-3, MF:C22H17ClN2O3, MW:392.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Optimization and Data Modeling Approaches

Optimization of biomass-to-energy conversion extends beyond the reactor to encompass the entire supply chain and process modeling.

- Supply Chain Optimization: Geographic Information Systems (GIS) are used for strategic planning of biomass collection, storage, and transport logistics. Linear programming (LP) models are applied to minimize costs or emissions across the supply chain [40].

- Process Modeling: Machine Learning (ML) techniques, particularly Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), are increasingly used to predict process outcomes like syngas composition and yield based on input parameters, offering advantages in handling non-linear relationships [38].

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): A critical tool for evaluating the environmental footprint of thermochemical processes, from feedstock acquisition to end-use, ensuring that sustainability goals are met [35] [36].

Anaerobic digestion (AD) and fermentation are cornerstone technologies for converting biomass into renewable energy, playing a critical role in the global transition towards a circular bioeconomy. The optimization of these biomass-to-energy conversion processes is a dynamic field of research, driven by the dual needs of sustainable waste management and renewable energy production [41]. The number of scientific publications related to AD peaked in 2021 with 3,554 papers, reflecting sustained and significant scientific interest [42]. These biochemical conversion pathways effectively transform diverse organic feedstocks—including agricultural residues, municipal waste, wastewater, and energy crops—into valuable energy carriers such as biogas, methane, and biohydrogen, while simultaneously reducing greenhouse gas emissions and diverting waste from landfills [42] [41].

Recent innovations have dramatically shifted our understanding of these biological systems. Once considered "black box" processes, advances in molecular techniques and analytical technologies have illuminated the complex syntrophic microbial interactions that underpin degradation efficiency [42]. The discovery of approximately 30 new archaeal phyla and candidate bacterial phyla like Cloacimonetes (WWE1)—frequently found in anaerobic systems but not yet cultivated—highlights the vast unexplored microbial diversity that presents both challenges and opportunities for process optimization [42]. This application note details cutting-edge protocols and analytical frameworks designed to leverage these biological and technological advances, providing researchers with practical methodologies to enhance biomass conversion efficiency, product yield, and process stability.

Advanced Technologies in Biomass Conversion

The optimization of anaerobic digestion and fermentation systems has been accelerated through several innovative technological approaches. These intensification strategies address inherent limitations of conventional processes, such as slow reaction rates during hydrolysis and methanogenesis, and system sensitivity to operational parameters [43].

Table 1: Innovative Intensification Technologies for Anaerobic Digestion

| Technology | Mechanism of Action | Key Performance Gains | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Electrolysis Cells (MEC) | Applied voltage enhances microbial metabolism and electron transfer rates. | Improved biogas upgrading and yield; enhanced organic removal [43]. | High capital cost; system scalability. |

| Conductive Functional Materials | Facilitate direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) between syntrophic communities. | Accelerated methane production; improved process stability [43]. | Long-term material stability and cost. |

| Micro-aeration | Limited oxygen introduction promotes hydrolytic enzyme activity without inhibiting anaerobes. | Enhanced hydrolysis rates; reduced volatile fatty acid accumulation [43]. | Precise oxygen dosing control required. |

| Hydrogen Injection | Exogenous hydrogen promotes hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis and alters microbial pathways. | Increased methane yield; higher conversion efficiency [43]. | Hydrogen production and storage logistics. |