Optimizing Biomass Supply Chains: Design, Logistics, and Strategic Management for Renewable Energy

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the design and logistics of biomass supply chains (BSC), a critical component for the commercial viability of bioenergy and the broader bioeconomy.

Optimizing Biomass Supply Chains: Design, Logistics, and Strategic Management for Renewable Energy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the design and logistics of biomass supply chains (BSC), a critical component for the commercial viability of bioenergy and the broader bioeconomy. It explores the foundational structure of BSC networks, from biomass sourcing to energy conversion. The piece delves into advanced methodological approaches for optimization, including Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) and hybrid simulation-optimization techniques. It further addresses key challenges such as supply uncertainty, logistical costs, and disruption risks, presenting robust optimization and strategic coordination as solutions. Finally, the article validates these approaches through comparative analyses of optimization algorithms and coordination strategies, offering insights for researchers and professionals in renewable energy and sustainable development.

The Building Blocks of a Biomass Supply Chain: From Feedstock to Energy

The Biomass Supply Chain (BSC) is a critical system for the commercialization of bioenergy, encompassing the integrated processes of biomass feedstock procurement, handling, transportation, preprocessing, conversion, and distribution of final energy products [1]. As global energy demand continues to grow alongside the urgent need to combat climate change, renewable energy sources like bioenergy have become pivotal in transitioning away from fossil fuels [1]. An efficiently designed BSC is fundamental to meeting the growing demand for renewable energy while reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1]. The BSC tackles significant challenges, including the low energy density of raw biomass, high logistics costs, variability in biomass composition, and potential environmental impacts, making its optimal design a complex but essential endeavor for researchers and industry professionals [1].

This guide provides a technical overview of the BSC's core components and network flow, framed within the broader context of supply chain design and logistics research. It is structured to offer scientists, researchers, and drug development professionals a comprehensive understanding of the strategic, tactical, and operational decisions involved in creating a robust, efficient, and sustainable biomass supply system.

Core Components of the Biomass Supply Chain

The biomass supply chain comprises several interconnected components, each performing a distinct function in the journey from raw organic material to usable energy. The major components are detailed below.

Biomass Feedstocks

Biomass feedstock refers to any organic material that can be used as a fuel or converted into energy. These materials are typically categorized by their origin and can include:

- Agricultural Residues: Waste from agricultural production, such as crop residues (e.g., corn stover, rice husks) and processing by-products [1] [2].

- Forestry Waste: Residues from forestry operations, including tree tops, branches, and sawdust [1].

- Energy Crops: Plants specifically cultivated for energy production, such as switchgrass or miscanthus [3].

- Animal Waste: Manure from livestock farms [1].

- Municipal Solid Waste (MSW): Organic fractions of solid waste from municipalities [3] [2].

- Industrial Byproducts: Waste streams from industrial processes [4].

A key trend in the sector is the exploration of non-traditional biomass sources, such as landscaping waste and municipal solid waste, to meet rising demand and create new opportunities for sourcing and innovation [4].

Collection and Harvesting Sites

These are the points of origin for biomass, often referred to as watersheds or biomass supply locations in modeling contexts [1]. The cost and efficiency of harvesting and initial collection are significant factors in the overall supply chain economics [1]. The geographical distribution and seasonal availability of biomass at these sites present a primary challenge for strategic network design [1].

Preprocessing Depots (Bio-Hubs)

Preprocessing facilities, often termed depots, terminals, or bio-hubs, are strategically located between biomass sources and energy conversion plants [1] [5]. Their core function is to improve the quality and handling characteristics of raw biomass, which is vital for facilitating efficient conversion to energy products [1]. Key processes at these facilities include:

- Size Reduction: Chipping or grinding to create uniform particles.

- Densification: Compressing biomass into pellets or briquettes to increase bulk density and reduce transportation costs [1].

- Drying: Reducing moisture content to improve combustion efficiency and energy density [1].

- Thermal Pretreatment: Using processes like torrefaction to improve quality, consistency, and energy density [1].

Bio-hubs act as centralized collection and distribution points, balancing local supply and demand, streamlining logistics, and adding value to biomass resources [5]. They are critical for supply chain resilience, acting as buffers to manage fluctuations in biomass supply caused by weather or seasonal changes [5]. Two main types of depots are used:

- Fixed Depots (FDs): Stable facilities with consistent preprocessing capabilities that benefit from economies of scale and ensure a reliable supply [1].

- Portable Depots (PDs): Mobile units that can be relocated to areas with seasonal or varying biomass availability, introducing remarkable flexibility and adaptability to reduce costs and maximize aggregated biomass volumes [1].

Storage Facilities

Storage is an integral part of the logistics chain, necessary for mitigating the discrepancies between the continuous demand for energy and the often-seasonal supply of biomass [5]. Storage can occur at the harvest site, at preprocessing bio-hubs, or at the conversion facility. Proper storage is essential to prevent biomass degradation and maintain feedstock quality.

Transportation and Logistics

Transportation connects all the physical components of the supply chain. The low bulk density of raw biomass makes transportation a major cost component [1]. Logistics involves selecting the appropriate modes of transport (e.g., truck, rail, barge) and optimizing shipment frequencies and routes to minimize cost and energy consumption [1]. The Biomass Logistics Model (BLM) is an example of a tool developed to estimate delivered feedstock cost and energy consumption for various biomass supply system designs [3].

Conversion Facilities

These are the plants where preprocessed biomass is converted into useful energy or energy carriers. Common conversion technologies include:

- Combustion: Burning biomass to generate electricity and/or heat [1].

- Anaerobic Digestion: Breaking down organic material in the absence of oxygen to produce biogas [6] [2].

- Fermentation: Converting biomass into liquid biofuels like ethanol [1].

- Gasification: Converting biomass into syngas, which can be used for power generation or synthesized into fuels and chemicals [2].

- Pyrolysis: Thermochemically decomposing biomass at high temperatures in the absence of oxygen to produce bio-oil [2].

A growing trend is the development of integrated biorefineries, where multiple products such as energy, fuels, and chemicals are produced from the same feedstock, maximizing value and minimizing waste [2].

Distribution and End Use

The final component involves distributing the energy products (e.g., electricity, biofuel, biogas) to end-users, which can include the electrical grid, industrial consumers, transportation sectors, or residential heating systems [6].

Table 1: Core Components of the Biomass Supply Chain

| Component | Primary Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Feedstocks | Provide raw organic material for energy conversion. | Availability, sustainability, composition, cost. |

| Collection Sites | Points of biomass origin and initial aggregation. | Geographic distribution, seasonal variability. |

| Preprocessing Depots | Improve biomass quality and energy density. | Type (Fixed/Portable), location, technology used. |

| Storage Facilities | Mitigate supply-demand mismatches. | Prevents degradation, maintains quality. |

| Transportation | Moves biomass between supply chain nodes. | Major cost factor; mode and route optimization. |

| Conversion Facilities | Transform biomass into usable energy/products. | Technology choice, efficiency, scale. |

| Distribution | Delivers final energy products to consumers. | Integration with existing energy infrastructure. |

Biomass Supply Chain Network Flow

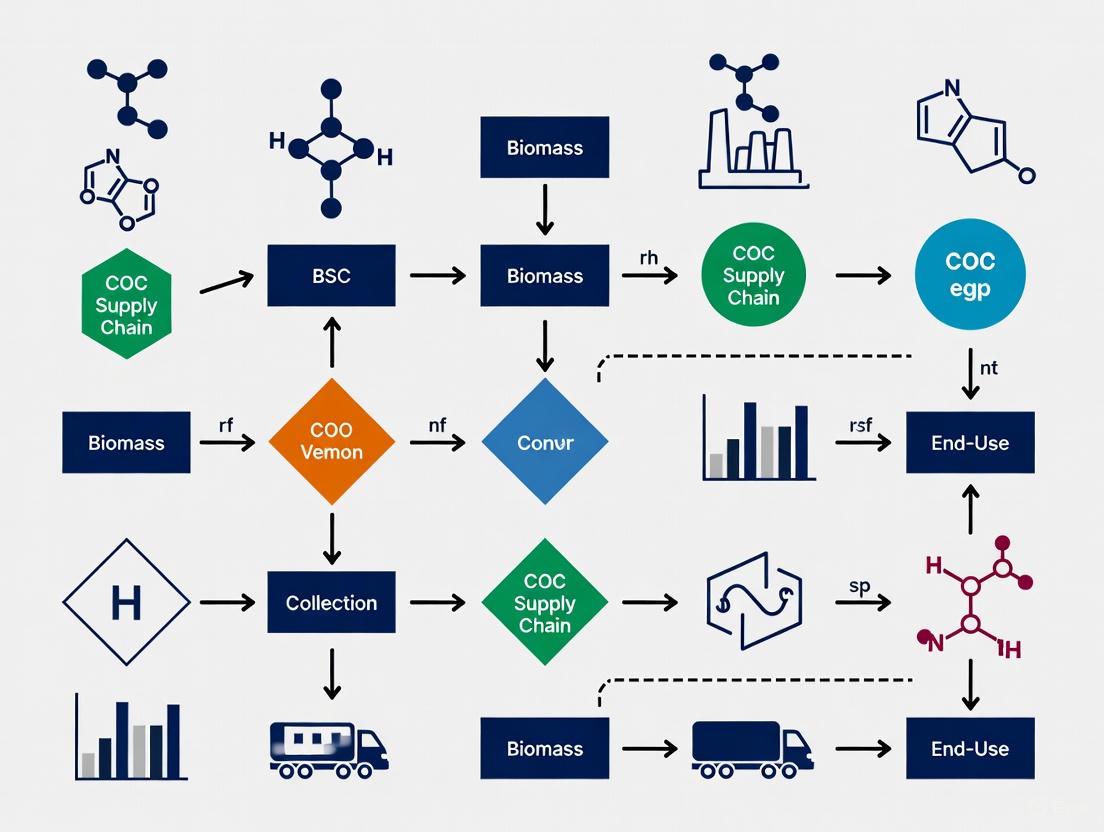

The flow of biomass through the supply chain is a sequential process that can be modeled and optimized. A typical network flow for a BSC involving both fixed and portable depots can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Biomass Supply Chain Network Flow. This diagram illustrates the typical movement of biomass from supply sources through optional preprocessing depots to conversion plants and finally to demand points.

The logical sequence of operations in a BSC generally follows these stages, which correspond to the nodes in the diagram above:

Biomass Production and Sourcing: The process begins with the procurement of biomass from various supply locations or watersheds (I) [1]. The cost and availability of biomass at these sources are foundational parameters for the supply chain.

Transportation to Preprocessing: Raw, low-density biomass is transported from supply locations to preprocessing facilities. The model must decide the optimal quantity of biomass to ship from each supply source

ito each depotj(whether fixed or portable) in a given time periodt[1].Preprocessing at Depots: At the depots (J), which include both Fixed Depots (FDs) and Portable Depots (PDs), biomass undergoes processing to enhance its properties [1]. Key decisions at this stage involve the strategic location of these depots and their operational capacity.

Transportation to Conversion Facility: The preprocessed biomass, now with higher energy density and more consistent quality, is transported to the energy conversion facility (K), such as a power plant or biorefinery [1] [6].

Energy Conversion: At the conversion facility, biomass is transformed into energy products, such as electricity or biofuels [6]. In the case of biogas production, this may involve additional steps where gas is transferred to condensers and transformers before becoming electricity [6].

Distribution to Demand Points: The final energy product is distributed to demand points, which are the end-users of the energy [6].

This network is subject to various constraints, including biomass availability at sources, capacity limitations at depots and conversion plants, and the need to meet demand [1]. The integration of both fixed and portable depots adds a layer of strategic complexity but offers significant advantages in cost efficiency and adaptability to biomass availability [1].

Quantitative Analysis and Market Data

A quantitative understanding of the biomass market and operational metrics is crucial for strategic planning and investment decisions in the BSC. The following tables consolidate key global market data and operational parameters.

Table 2: Global Biomass Market Overview and Forecasts

| Region | Market Size (2021) | Market Size (2025 Projected) | Market Size (2033 Projected) | CAGR (2021-2033) | Key Drivers & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global | $59.099 Billion [2] | $77.481 Billion [2] | $133.177 Billion [2] | 7.005% [2] | Supportive policies, tech advancements, circular economy. |

| Asia-Pacific | $18.025 Billion [2] | $24.187 Billion [2] | $43.549 Billion [2] | 7.628% [2] | Largest & fastest-growing region; abundant residues. |

| Europe | $16.666 Billion [2] | $21.455 Billion [2] | $35.558 Billion [2] | 6.519% [2] | Stringent EU carbon targets and established policies. |

| North America | $13.179 Billion [2] | $16.936 Billion [2] | $27.967 Billion [2] | 6.471% [2] | Federal incentives (e.g., U.S. Inflation Reduction Act). |

| South America | $4.728 Billion [2] | $6.250 Billion [2] | $10.920 Billion [2] | 7.225% [2] | Dominated by Brazil's bioethanol industry. |

| Africa | $3.723 Billion [2] | $4.936 Billion [2] | $8.523 Billion [2] | 7.066% [2] | Need for decentralized energy solutions. |

Table 3: Biomass Industrial Fuel Market Specifics

| Category | Data | Context and Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Global Market Value (2024) | USD 1,686 million [7] | Base year for biomass industrial fuel segment. |

| Projected Market Value (2031) | USD 3,316 million [7] | Demonstrates a strong growth trajectory for the sector. |

| CAGR (2025-2031) | 10.3% [7] | Highlights the rapid expected growth in the industrial fuel segment. |

| Primary Feedstocks | Wood, agricultural residues, palm kernel shells, rice husks [7] | Common organic materials used for solid industrial fuels. |

| Key Application | Industrial boilers, kilns, and steam generators [7] | Main industrial uses as a direct substitute for coal. |

Research Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Research and optimization of the BSC rely heavily on quantitative models and computational algorithms. The following section outlines prevalent methodologies cited in recent scientific literature.

Mathematical Optimization Modeling

A primary methodology for BSC design involves formulating the network as a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model [1]. The objective is typically to minimize total system cost or maximize profit, subject to a set of linear constraints that represent the physical and operational realities of the supply chain.

- Objective Function: A typical cost-minimization function aggregates costs across the supply chain, including harvesting (

H_it), transportation from supply to depots (C1_ij) and from depots to plants (C2_jk), processing at depots (P1_jt,P2_jt), and the fixed costs of establishing and operating depots (F_j,G_jt) [1]. - Key Decision Variables: These models determine strategic decisions (e.g., whether to open a depot at location

j(Y_j)) and tactical decisions (e.g., the flow of biomass from supplyito depotjin periodt(X1_ijt)) [1]. - Constraints: The model is bound by constraints such as biomass availability at each source, capacity limits at depots and conversion plants, and the requirement to meet the demand of the conversion facility [1].

Metaheuristic Solution Algorithms

For large-scale or complex problems where exact MILP solvers become computationally intensive, metaheuristic algorithms are employed.

- Genetic Algorithm (GA): This population-based algorithm mimics natural selection. In a BSC context, a solution (chromosome) might encode facility locations and flow decisions. The algorithm evolves a population of solutions over generations through selection, crossover, and mutation operations to find a near-optimal solution [6]. A study designing a sustainable BSC under disruption reported that GA provided better values with a deviation of 2.9% compared to other methods [6].

- Simulated Annealing (SA): This algorithm is inspired by the annealing process in metallurgy. It starts with an initial solution and iteratively explores the solution space by accepting not only improving moves but also, with a certain probability, moves that worsen the objective function. This probability decreases over time, allowing the algorithm to escape local optima and converge toward a global optimum [6].

Simulation and Techno-Economic Analysis

Engineering process models are integrated with economic analysis to evaluate specific supply chain designs.

- Biomass Logistics Model (BLM): The BLM is a hybrid engineering and supply chain accounting tool that simulates the flow of biomass through the entire supply chain [3]. It tracks changes in critical feedstock characteristics like moisture content, ash content, and dry bulk density as influenced by various operations, providing detailed estimates of delivered feedstock cost and energy consumption [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Models

For researchers engaged in BSC design and analysis, the following tools and models are essential for conducting robust and relevant investigations.

Table 4: Essential Research Tools and Models for BSC Analysis

| Tool/Model Name | Type/Platform | Primary Function in BSC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | Mathematical Programming | Provides a framework for optimal strategic/tactical decision-making in network design (e.g., facility location, biomass flow) [1]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Metaheuristic Algorithm | Solves complex, large-scale BSC optimization problems where exact methods are computationally prohibitive [6]. |

| Simulated Annealing (SA) | Metaheuristic Algorithm | Offers an alternative heuristic approach for finding near-optimal solutions to complex BSC design problems [6]. |

| Biomass Logistics Model (BLM) | C#, Powersim / Hybrid Simulation | Estimates delivered feedstock cost and energy consumption while tracking changes in feedstock quality throughout the supply chain [3]. |

| Bio-Hub Concept | Strategic Framework | Serves as a model for designing centralized, multi-functional preprocessing facilities that optimize logistics and add value to biomass [5]. |

| Azido-PEG5-azide | Azido-PEG5-azide, CAS:356046-26-9, MF:C12H24N6O5, MW:332.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Oct4 inducer-1 | 4-fluoro-N-(1H-indol-5-yl)benzamide | RUO | Supplier | High-quality 4-fluoro-N-(1H-indol-5-yl)benzamide for research use only (RUO). Explore its applications in kinase & cancer signaling research. Not for human use. |

The biomass supply chain is a sophisticated system with defined core components—feedstocks, collection, preprocessing depots (bio-hubs), storage, transportation, conversion, and distribution—that interact in a sequential network flow. The design and operation of this network are paramount to achieving cost efficiency, sustainability, and resilience [1] [5] [8]. The field is supported by advanced mathematical modeling techniques, primarily MILP and metaheuristics like GA and SA, which serve as critical decision-support tools for strategic planning [1] [6]. As the global biomass market continues its robust growth, driven by regulatory policies and technological innovation, the importance of sophisticated logistics and network design will only intensify. Future research is likely to focus increasingly on managing uncertainties and disruptions, with emerging technologies like machine learning and agent-based simulation offering promising avenues for creating more robust and adaptable biomass supply chains [8].

Strategic Importance of BSCs for Renewable Energy and Bioeconomy Goals

The global transition towards a sustainable, low-carbon economy has positioned biomass as a cornerstone of the renewable energy sector. Biomass Supply Chains (BSCs) are critical infrastructures responsible for the movement of organic material from its source to the point of conversion and finally to the end-user, transforming raw biomass into valuable energy, fuels, and biochemicals [9]. The strategic design and optimization of these chains are not merely logistical exercises but are fundamental to realizing global renewable energy and bioeconomy ambitions. BSCs enable the utilization of a diverse range of feedstocks—including agricultural residues, forestry waste, municipal solid waste, and energy crops—offering a carbon-neutral alternative to fossil fuels while simultaneously addressing waste management challenges [2] [9]. Their role is multifaceted, impacting energy security, rural development, and industrial decarbonization. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the strategic importance of BSCs, framed within the context of broader research on their design and logistics. It synthesizes current market data, explores advanced methodological frameworks for optimization, and details the essential tools and reagents required by researchers and development professionals to advance this critical field.

Global Market Context and Strategic Drivers

The biomass market is experiencing significant expansion, driven by concerted global efforts to mitigate climate change and enhance energy security. The market's robust growth trajectory underscores its strategic importance in the global energy landscape.

Table 1: Global Biomass Market Size Projections

| Market Segment | Base Year/Value | Projected Year/Value | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Biomass Market | 2021: $59.099 Billion | 2033: $133.177 Billion | 7.005% (2025-2033) | [2] |

| Overall Biomass Market | 2025: $79.26 Billion | 2035: $157.38 Billion | 7.1% (2026-2035) | [10] |

| Biomass Power Generation | 2024: $90.8 Billion | 2030: $116.6 Billion | 4.3% (2024-2030) | [11] |

Table 2: Regional Market Dynamics (Projected 2025 Market Share and Key Characteristics)

| Region | Approx. Global Share (2025) | Key Growth Drivers | Leading Countries/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia-Pacific (APAC) | 31.22% | Soaring energy demand, abundant agricultural residues, government waste-to-energy initiatives [2]. | China (9.34% global share), India (6.00%), Japan (5.89%) [2]. |

| Europe | 27.69% | Ambitious decarbonization goals (e.g., EU Green Deal), stringent carbon pricing [2]. | Germany (5.05%), UK (3.76%), France (3.73%) [2]. |

| North America | 21.86% | Strong federal & state incentives (e.g., Inflation Reduction Act), demand for renewable fuels [2]. | USA (17.46%), Canada (3.62%) [2]. |

| South America | 8.07% | Vast agricultural sector providing ample feedstock [2]. | Brazil (3.54%, world-leading bioethanol) [2]. |

| Africa | 6.37% | Need for decentralized & off-grid energy solutions to improve energy access [2]. | Nigeria (2.81%), South Africa (2.43%) [2]. |

The growth of the biomass market is propelled by several key strategic drivers:

- Supportive Regulatory Frameworks: Governments worldwide are implementing policies such as feed-in tariffs, tax credits, renewable portfolio standards, and carbon pricing mechanisms to incentivize biomass adoption and meet climate targets [2] [11].

- Advancements in Conversion Technologies: Technological evolution from traditional combustion to advanced methods like gasification, pyrolysis, and anaerobic digestion is improving efficiency and enabling the production of higher-value products such as advanced biofuels (e.g., Sustainable Aviation Fuel) and biochemicals [2] [11].

- Integration into Circular Economy Models: The increasing use of waste-to-energy (WTE) technologies allows municipalities and industries to address growing waste management challenges while simultaneously generating electricity, aligning biomass with the circular economy concept [2] [11].

Technical Composition and Methodologies for BSC Analysis

A Biomass Supply Chain is a complex system involving multiple interconnected stages and stakeholders. Its core objective is to ensure a continuous, cost-effective, and quality-controlled supply of biomass to conversion facilities [9].

Diagram 1: Biomass Supply Chain Structure and Influences. MSW: Municipal Solid Waste.

Core Methodological Framework: Mathematical Optimization

The design and management of BSCs are fundamentally reliant on mathematical optimization to navigate inherent complexities such as feedstock seasonality, geographical dispersion, and cost trade-offs [9] [12] [13]. The most prevalent approach is Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP), which is used to model decisions that involve discrete choices (e.g., facility location, technology selection) and continuous variables (e.g., biomass flow quantities) [12] [13].

Experimental/Methodological Protocol: Formulating a BSC Optimization Model

Problem Scoping and Objective Definition:

- Objective Function: Typically aims to maximize net present value (NPV) or minimize total supply chain cost [12]. The objective must encompass capital expenditures (CAPEX), operational expenditures (OPEX), transportation costs, and revenue from product sales.

- System Boundaries: Define the spatial (geographical region) and temporal (single-period vs. multi-period) scope of the model [13].

Model Formulation:

- Decision Variables:

- Constraints:

- Mass Balance: Flow of biomass into a node must equal flow out, accounting for conversion efficiencies [12].

- Capacity: Total biomass processed at a facility cannot exceed its installed capacity [12] [13].

- Demand: Production of end-products must meet specified demand [9].

- Resource Availability: Biomass sourced from a location cannot exceed its sustainable yield [12] [13].

- Logical: Transportation can only occur if corresponding facilities exist [13].

Data Acquisition and Parameterization:

- Collect data on biomass yield profiles (which can be non-linear to reflect growth cycles), moisture content, and spatial distribution [12] [13].

- Determine economic parameters: feedstock cost, investment and operating costs for technologies, transportation costs, and product prices [12].

- Incorporate Geographical Information System (GIS) data to accurately model transportation distances and costs [13].

Model Solving and Validation:

- Solve the MILP using optimization solvers (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi).

- Conduct sensitivity analysis on key parameters (e.g., biomass availability, product prices, transportation costs) to test the robustness of the solution and understand the impact of uncertainties [12].

Advanced Optimization Frameworks and Experimental Insights

Building on the core MILP methodology, researchers are developing increasingly sophisticated frameworks to address specific BSC challenges.

Integrated Biomass Supply Network and Process Optimization

A notable advancement is the simultaneous optimization of the supply chain network and the internal process variables of the conversion plant. This is often formulated as a Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) problem to capture the nonlinear relationships between process variables and performance [12].

Case Study Application: A hypothetical case study in Slovenia optimized a supply chain for heat and power generation using a steam Rankine cycle. The model co-optimized the supply network (biomass supply zones, storage locations, transportation links) and key process variables (considering variable heat demand). The results demonstrated economic viability with an NPV of nearly 300 MEUR, generating about 4 MW of electricity and 65 MW of heat. The sensitivity analysis highlighted the significant impact of biomass supply uncertainty and product price fluctuations on economic performance [12].

Decentralized Processing with Mobile Facilities

To overcome the high costs of transporting low-density biomass over long distances, decentralized processing models using mobile conversion facilities (e.g., for fast pyrolysis) have been proposed [13].

Diagram 2: Decentralized BSC Model with Mobile Pretreatment.

Experimental Protocol for Decentralized BSC Modeling:

- Technology Selection: Choose a suitable mobile technology, such as fast pyrolysis, which converts biomass into a denser, liquid bio-oil that is more economical to transport over long distances [13].

- Incorporate Relocation Logistics: The MILP model must include decisions on the optimal scheduling and routing of mobile units between biomass supply points. This involves calculating relocation costs based on distance travelled [13].

- Model Trade-offs: Analyze the trade-off between the capital savings from fewer large-scale fixed facilities and the increased transportation and relocation costs associated with mobile units. The model should determine the optimal mix of fixed and mobile facilities [13].

- Case Study Insight: Application of this methodology to marginal lands in Scotland planted with Miscanthus showed that storage capacity is crucial for widening the operational time window of processing facilities. Scenarios with restricted storage led to higher-capacity facilities operating for shorter periods, increasing investment costs. Relocation costs were found to be a minor component of total transportation costs [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for BSC Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Reagents for BSC Experimentation

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Description | Application in BSC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Programming Software | Platforms like GAMS, AMPL, or AIMMS used to codify and solve MILP/MINLP models. | The core computational environment for formulating and solving supply chain optimization problems [12] [13]. |

| GIS Datasets & Software | Geographic Information Systems provide spatial data on biomass availability, land use, and transportation networks. | Critical for accurate geospatial modeling, determining transport costs, and optimal facility siting [13]. |

| Process Simulation Software | Tools like Aspen Plus or similar to simulate biomass conversion processes (e.g., gasification, pyrolysis). | Used to generate techno-economic data (yields, efficiencies, costs) required for parameterizing the optimization models [12]. |

| Biomass Feedstock Samples | Physical samples of target feedstocks (e.g., Miscanthus, corn stover, wood chips) with characterized properties. | Essential for laboratory-scale experiments to determine proximate/ultimate analysis, moisture content, and conversion yields for model inputs [12] [13]. |

| Life Cycle Assessment Database | Databases containing environmental impact data for various processes and materials. | Integrated with optimization models for multi-objective analysis that minimizes environmental impact (e.g., GHG emissions) alongside cost [9]. |

| mTOR inhibitor WYE-28 | mTOR inhibitor WYE-28, MF:C30H34N8O5, MW:586.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Z-D-Ser(TBu)-OH | Z-D-Ser(TBu)-OH, CAS:65806-90-8, MF:C15H21NO5, MW:295.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The strategic importance of robustly designed and optimized Biomass Supply Chains is unequivocal for achieving global renewable energy and bioeconomy goals. BSCs are the critical link that transforms the potential of abundant biomass resources into tangible, dispatchable energy and sustainable bioproducts. The field is supported by sophisticated methodological approaches, primarily MILP and MINLP optimization, which are continuously evolving to integrate geospatial data, process variables, and innovative logistical concepts like mobile preprocessing. For researchers and drug development professionals operating in the bioeconomy space, a deep understanding of these BSC frameworks is not ancillary but central to ensuring the economic viability and environmental integrity of the bio-based solutions of the future. The tools and methodologies outlined in this whitepaper provide a foundation for advancing research, overcoming key challenges related to feedstock logistics and costs, and ultimately unlocking the full potential of biomass as a pillar of a sustainable economy.

Biomass feedstocks, derived from organic materials, form the foundational input for producing bioenergy and bioproducts, playing a critical role in the transition toward a circular bioeconomy. Within the context of Biomass Supply Chain (BSC) design and logistics, understanding the characteristics, availability, and inherent properties of different feedstock types is paramount for optimizing supply chain efficiency, ensuring economic viability, and minimizing environmental impact. These feedstocks are primarily categorized into agricultural residues, forestry products, and various waste resources. The global solid biomass feedstock market, valued at an estimated $26.6 billion in 2024 and projected to reach $36.2 billion by 2029, underscores the growing economic and strategic importance of these materials [14]. This growth is propelled by stringent environmental regulations, increasing demand for biofuels, and a global emphasis on renewable energy sources [15] [14] [16]. The effective integration of these diverse feedstocks into a resilient supply chain is a central challenge and objective of modern bioenergy research and commercial deployment.

Classification and Characteristics of Biomass Feedstocks

Biomass feedstocks can be systematically classified based on their origin, physical properties, and conversion suitability. The following table provides a comparative overview of the primary feedstock categories, highlighting key characteristics relevant to supply chain and logistics planning.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Major Biomass Feedstocks

| Feedstock Category | Specific Examples | Key Characteristics | Common Applications/Forms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Residues | Rice husks, sugarcane bagasse, corn stover, straw, coconut shells [15] [7] [16]. | Abundant availability, cost-effective, often seasonal, requires collection logistics [15] [16]. | Chips, briquettes, direct combustion for heat/power, biofuel production [16]. |

| Forest Waste & Residues | Wood chips, sawdust, tree bark, logging residues [17] [14] [16]. | Higher energy density, established forestry sector, sustainable management practices [16]. | Wood pellets, chips, briquettes for electricity, heat, and biofuel [14] [16]. |

| Municipal Solid Waste | Organic fraction of municipal waste [14]. | Heterogeneous composition, requires processing, aligns with waste management goals [14]. | Processed Solid Recovered Fuels (SRF) for electricity and heat generation [14]. |

| Densified Biomass | Wood pellets, agro-residue briquettes [7]. | High energy density, uniform shape, improved storability and transport efficiency [7] [14]. | Standardized fuel for residential heating and industrial power generation [7] [16]. |

The "wood and agricultural residues" segment is a dominant force, expected to account for 42.7% of the biomass fuel market share in 2025 due to their widespread availability and cost-effective nature [15]. These materials, often considered waste products, provide a dual benefit of waste management and the creation of a valuable energy resource [15] [14]. The selection of a specific feedstock for a given bioenergy project is influenced by regional availability, technological compatibility with conversion processes, and the overarching economic and environmental constraints of the biomass supply chain.

Biomass Supply Chain Workflow: From Feedstock to Energy

The biomass supply chain is a multi-stage process that transforms raw organic materials into usable energy. The design of this network must carefully balance efficiency, cost, and sustainability, often considering potential disruptions. The following diagram synthesizes the core workflow, from feedstock collection to final energy delivery, illustrating the key nodes and material flows essential for effective BSC design and logistics.

Biomass to Energy Supply Chain

This workflow outlines the primary logistics operations within a BSC. The process begins with the collection of raw biomass from diverse sources, which often undergoes pre-processing (e.g., drying, size reduction) at or near the source to improve transport efficiency and stability [6] [14]. The material is then transported to centralized storage hubs, which are critical for buffering the seasonality and variability of feedstock supply [6]. A key logistics challenge is managing the low energy density and irregular shape of raw biomass, which can lead to increased transportation costs [14]. From storage, the feedstock is conveyed to a conversion facility (reactor) where it is transformed into an energy carrier, such as producer gas via gasification [6]. This energy intermediate subsequently passes through a condenser and transformer (e.g., a generator) to be converted into a readily usable form like electricity, which is finally distributed to end-users [6]. Designing this network to be resilient to disruptions—such as feedstock variability or transportation delays—is a primary focus of advanced BSC research and modeling [6].

Experimental Methodologies for Feedstock and Supply Chain Analysis

Robust experimental and analytical protocols are essential for characterizing feedstocks and optimizing the Biomass Supply Chain. Researchers and industry professionals employ a suite of methodologies to assess material properties and model complex logistics networks.

Feedstock Characterization and Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA)

A critical first step in BSC design is the thorough characterization of the feedstock to determine its suitability for conversion processes. Key parameters include moisture content, calorific value, and ash composition. Furthermore, Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) is used to evaluate project viability.

- Proximate and Ultimate Analysis: This is a standard laboratory protocol for determining the fundamental composition of solid biomass. Proximate analysis measures moisture content, volatile matter, fixed carbon, and ash content, providing insights into combustion behavior. Ultimate analysis determines the elemental composition (Carbon, Hydrogen, Nitrogen, Sulfur, Oxygen), which is crucial for calculating energy content and estimating emissions [14]. Tools like advanced moisture sensors (e.g., the IR-3000 Series) are used in production to monitor and control moisture levels, reducing energy consumption and waste [18].

- Techno-Economic Modeling: This methodology involves developing a comprehensive process model for a biomass facility using software like Excel or specialized process simulators [6]. The model integrates data on capital expenditures (CAPEX), operating expenditures (OPEX), feedstock costs, and product revenues. The output is used to calculate key financial metrics such as Net Present Value (NPV) and Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE), which are vital for assessing the profitability and risk of bioenergy investments [6].

Supply Chain Modeling and Optimization

To address the logistical complexities of biomass, mathematical modeling approaches are employed to design efficient and resilient supply chains.

- Multi-stage Stochastic Programming for BSC Design: This advanced methodology accounts for uncertainty and disruption in the supply chain [6]. The experimental workflow begins with Problem Scoping, identifying key uncertain parameters such as feedstock availability, market prices, and potential facility disruptions. The next step is Model Formulation, which creates a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model. The objective function is typically to maximize total profit or minimize total cost, subject to constraints including capacity, demand, and sustainability criteria [6]. A critical phase is Scenario Generation, where a multitude of possible future states (scenarios) are defined for the uncertain parameters. Finally, Algorithmic Solving is performed using optimization software and metaheuristic algorithms like Genetic Algorithm (GA) and Simulated Annealing (SA) to find near-optimal solutions for the complex, large-scale problem [6]. Research has shown that GA can provide solutions with a deviation of just 2.9% from the optimal, proving its effectiveness for these problems [6].

Research and development in biomass feedstocks and supply chains rely on a suite of essential analytical tools, software, and reagents. The following table details critical components of the researcher's toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Biomass Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Relevance to BSC Research |

|---|---|---|

| Near-IR Moisture Sensor (e.g., IR-3000 Series) | Precisely measures moisture content in biomass during processing [18]. | Critical for quality control, optimizing drying processes, and ensuring feedstock stability during storage and transport [18] [14]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) & Simulated Annealing (SA) | Metaheuristic optimization algorithms [6]. | Used to solve complex BSC network design models, determining optimal locations for facilities and logistics routes under uncertainty [6]. |

| Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | A mathematical modeling framework for optimization [6]. | The primary methodology for formulating BSC design problems to maximize profit or minimize cost while adhering to physical and policy constraints [6]. |

| Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) Model | A integrated process and financial model [6]. | Evaluates the economic viability of biomass conversion pathways and the overall supply chain, informing investment decisions [6]. |

The diverse portfolio of biomass feedstocks—encompassing agricultural, forestry, and waste resources—provides a substantial foundation for advancing renewable energy and supporting a circular economy. The effective mobilization of these resources is entirely dependent on the meticulous design and robust operation of the Biomass Supply Chain. Key challenges such as feedstock seasonality, logistical complexities due to low energy density, and the need for cost-effective pre-treatment processes must be systematically addressed through integrated research approaches [14] [16]. The application of sophisticated modeling techniques, including multi-stage stochastic programming and metaheuristic optimization, is proving essential for developing BSCs that are not only economically efficient but also resilient to disruptions [6]. As the global market for solid biomass continues to expand, driven by policy and climate goals, future research will increasingly focus on integrating waste management systems, advancing pre-treatment technologies like torrefaction and pelletization, and leveraging computational tools to de-risk investments and enhance the sustainability of the entire bioenergy value chain [15] [14] [16].

The efficient design and management of the biomass supply chain (BSC) is a critical determinant for the economic viability and environmental sustainability of bioenergy and biofuel production. Biomass logistics encompasses the complete sequence of operations required to move biomass from its origin in the field or forest to the throat of a biorefinery or conversion facility, and subsequently to distribute the resulting energy products to end-users [19] [20]. These operations are characterized by significant complexities arising from the inherent properties of biomass, including its seasonal availability, scattered geographical distribution, low bulk density, and quality variations [19]. The inter-dependencies among logistics operations further complicate optimization efforts [19].

Logistics cost constitutes a major component of the total cost of bioenergy and biofuels; in certain cases, it can represent up to 90% of the total feedstock cost [19]. Consequently, improvements in logistics are paramount for advancing biomass utilization [19]. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of the four core processes—harvesting, preprocessing, transportation, and conversion—framed within the broader context of BSC design and logistics optimization for a research-oriented audience.

Harvesting and Collection

Harvesting and collection form the initial and foundational stage of the biomass supply chain. This process involves the gathering of raw biomass from its source points, which can include agricultural fields, forests, or dedicated energy crop plantations. The primary objective is to efficiently recover biomass in a form that minimizes initial losses and preserves quality for subsequent operations. Key decisions at this stage revolve around determining the optimal harvesting schedule, selecting the appropriate harvesting equipment and methods, and organizing the initial collection of biomass for transport to storage or preprocessing sites [19]. The specific techniques employed vary significantly between agricultural and forest-based biomass, requiring tailored modeling approaches [19].

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Research into optimizing harvesting and collection employs a variety of sophisticated methodologies:

- Mathematical Optimization Modeling: Linear and mixed-integer programming models are developed to determine the optimal harvest schedule that minimizes total cost while respecting constraints such as seasonal availability and equipment capacity [19]. For instance, a corn-stover harvest scheduling model was formulated to address the time-sensitive nature of residue collection [19].

- Integrated Simulation-Optimization Frameworks: Tools like the Integrated Biomass Supply Analysis and Logistics Model (IBSAL) use simulation to analyze the performance of collection operations, accounting for variable weather conditions and equipment availability, thereby providing data for strategic optimization [19].

- Life Cycle Assessment (LCA): LCA methodologies are applied to evaluate the environmental impacts of different harvesting techniques, considering factors like fuel consumption, soil health, and carbon emissions [6] [20].

Key Parameters and Performance Metrics

Critical parameters influencing harvesting efficiency are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in Harvesting and Collection

| Parameter | Typical Range/Impact | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture Content at Harvest | Varies by crop and season | Affects degradation rate, storage needs, and conversion efficiency [19]. |

| Biomass Yield per Area | e.g., tons/acre of straw or wood | A primary determinant of supply density and collection radius feasibility [19]. |

| Field or Forest Operation Efficiency | e.g., tons/hour | Influences equipment requirements and operational costs [19]. |

| In-field Dry Matter Loss | Can be significant without proper protocols | Directly impacts overall supply chain efficiency and biomass throughput [20]. |

Preprocessing and Storage

Preprocessing involves a series of operations designed to transform raw biomass into a higher-value, more handleable commodity. The core objectives are to increase the bulk density of the biomass for more economical transportation, improve handling characteristics, enhance homogeneity, and preserve quality during storage. Common preprocessing operations include size reduction (e.g., chipping, grinding), drying (to reduce moisture and prevent spoilage), and densification (e.g., pelleting, briquetting) [19] [5]. Storage acts as a critical buffer to reconcile the mismatch between seasonal biomass availability and the continuous demand of conversion facilities, but it introduces challenges related to dry matter losses and quality degradation [19].

The Bio-Hub Model

A significant innovation in preprocessing logistics is the bio-hub concept. A bio-hub is a centralized facility that functions as a strategic nerve center for biomass logistics [5]. It consolidates feedstock from multiple suppliers and performs various value-adding functions:

- Processing: Converting low-density biomass into standardized, higher-quality products like pellets or torrefied biomass [5].

- Storage: Acting as an inventory buffer to smooth out supply fluctuations caused by seasonality or weather [5].

- Distribution: Coordinating the efficient transport of preprocessed biomass to multiple end-users [5]. This model enhances supply chain resilience and enables logistical optimization that would be impossible with a direct, point-to-point supply chain [5].

Experimental Protocols for Storage and Preprocessing

- Deterioration Rate Studies: Experiments involve storing biomass samples (e.g., wood chips, agricultural residues) under controlled and real-world conditions. Samples are periodically monitored for metrics like dry mass loss, moisture content re-absorption, and calorific value change to model degradation kinetics [19].

- Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA): This methodology is used to evaluate the economic feasibility of different preprocessing technologies (e.g., AFEX pretreatment, fast pyrolysis) and bio-hub configurations. It involves developing detailed cost models for capital and operating expenses and projecting revenue streams from multiple products [6].

- Densification Trials: These experiments test the efficacy of different pelleting or briquetting processes by measuring the resulting bulk density, mechanical durability, and energy consumption of the equipment, often optimizing parameters like particle size, pressure, and temperature.

Transportation

Transportation is a critical and costly link that connects all other elements of the biomass supply chain. The primary objective is to move biomass from fields or forests to preprocessing sites (e.g., bio-hubs) and finally to conversion reactors in the most cost-effective and reliable manner [19]. The low bulk density of most raw biomass forms makes transportation particularly expensive per unit of energy, necessitating optimization. Key decisions involve selecting transport modes (e.g., truck, rail, ship), scheduling shipments, managing fleet logistics, and designing the overall network topology to minimize costs and environmental impact [19] [20].

Methodologies and Optimization Approaches

- Multimodal Transport Optimization: Recent trends involve integrating multiple transportation modes into a single optimization model. For example, models have been developed that combine truck transport for local collection with rail or ship for long-distance hauls, significantly reducing specific transport costs, especially for international markets [19] [20].

- Dynamic Freight Routing: To manage congestion and uncertainties, dynamic routing models use real-time or simulated traffic data to reroute shipments, improving fleet utilization and reliability [19].

- Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP): This is a widely used technique for modeling the complex, discrete decisions in transportation network design, such as facility location, fleet allocation, and route selection, while considering constraints like capacity and time windows [19] [6].

Key Data and Transportation Metrics

The economic and environmental impact of transportation is quantified through several key metrics, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Parameters in Biomass Transportation

| Parameter | Impact on Supply Chain | Research Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk Density (pre/post-processing) | Directly influences transport cost per energy unit. | Densification (pelletizing, torrefaction) can dramatically improve this metric [19] [20]. |

| Transport Distance | A primary driver of cost and GHG emissions. | Optimization models seek to minimize total distance traveled through strategic facility placement [19]. |

| Mode-specific Costs | Truck (high variable cost), Rail/Ship (lower cost for large volumes). | Multimodal solutions are often optimal [19] [20]. |

| GHG Emissions from Transport | Contributes to the overall carbon intensity of the biofuel. | Critical for complying with sustainability criteria and certification schemes [20]. |

Conversion and Integration

Conversion is the process where preprocessed biomass is transformed into useful energy carriers, such as electricity, biofuels (e.g., ethanol, biodiesel), or biogas. While this process occurs in a reactor (e.g., anaerobic digester, gasifier, biorefinery), its integration with upstream logistics is a core focus of supply chain design [6]. The objective from a logistics perspective is to ensure a consistent, high-quality feedstock supply that meets the specific requirements of the conversion technology, thereby maximizing conversion yield and plant throughput.

Modeling Integrated Supply Chains

Advanced optimization models now integrate conversion processes with upstream logistics. For example:

- Multi-stage Stochastic Programming: These models account for uncertainties in biomass supply and quality, and optimize decisions from feedstock sourcing through to the final energy product, ensuring the reactor is supplied reliably despite fluctuations [19] [6].

- Sustainability-integrated Models: Recent research proposes mathematical models that simultaneously maximize profit from energy sales while incorporating environmental (e.g., GHG emissions) and social criteria directly into the supply chain design, ensuring the entire chain, including conversion, aligns with sustainability goals [6].

Visualization of Biomass Supply Chain Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected stages of the biomass supply chain, highlighting key logistics operations and material flows.

Biomass Supply Chain Workflow

Visualization of Bio-Hub Operations

The bio-hub model centralizes key logistics functions, as detailed in the diagram below.

Bio-Hub Operational Model

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Analytical Frameworks

Table 3: Essential Modeling and Analysis Tools for BSC Research

| Tool / Framework | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) | Optimizes complex decisions involving discrete (yes/no) and continuous variables. | Used for facility location (e.g., bio-hub placement), fleet sizing, and multi-period production planning [19] [6]. |

| Multi-stage Stochastic Programming | Models optimization under uncertainty across sequential decision stages. | Applied to manage risks from biomass supply uncertainty and price fluctuations over a planning horizon [19] [6]. |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | A metaheuristic inspired by natural selection to solve complex optimization problems. | Used to solve large-scale, non-linear supply chain design models where exact methods are computationally prohibitive [6]. |

| Techno-Economic Analysis (TEA) | Evaluates the technical and economic feasibility of a process or system. | Employed to assess the profitability of integrating new preprocessing technologies or a new biorefinery [6]. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | Quantifies the environmental impacts of a product or system throughout its life cycle. | Essential for calculating the carbon intensity of biofuels to ensure compliance with sustainability regulations [20]. |

| (tert-Butoxycarbonyl)methionine | (tert-Butoxycarbonyl)methionine, CAS:2488-15-5, MF:C10H19NO4S, MW:249.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| N-Acetyl-L-aspartic acid-d3 | N-Acetyl-L-aspartic acid-d3, CAS:1383929-94-9, MF:C6H9NO5, MW:178.158 | Chemical Reagent |

The key processes of harvesting, preprocessing, transportation, and conversion are deeply interconnected within the biomass supply chain. Optimizing this system requires a holistic approach that considers the unique characteristics and complexities of biomass, including seasonality, geographical dispersion, and material degradation. Current research trends are increasingly focused on addressing uncertainties, incorporating sustainability metrics, and developing innovative logistical structures like bio-hubs and multimodal transport networks. The use of advanced mathematical modeling, simulation, and analysis frameworks is essential for designing cost-effective, reliable, and sustainable biomass supply chains that can support the growing bioeconomy. Future research directions will likely involve greater integration of digital technologies and circular economy principles to further enhance the resilience and efficiency of these complex systems.

The biomass supply chain (BSC) encompasses all activities from biomass harvesting to the delivery of bio-based products, including transportation, storage, conversion, and distribution [9]. Within this chain, preprocessing depots serve as critical intermediary facilities that transform raw biomass into a conversion-ready feedstock, addressing fundamental challenges of biomass as a commodity: low bulk density, seasonal availability, and variable physical and chemical properties [9] [21]. These depots perform operations such as size reduction, densification (pelletizing, briquetting), drying, and ash reduction to create a stable, uniform, and transportable material [9] [22]. Integrating depot facilities mitigates significant operational risks for biorefineries, including handling difficulties, feedstock quality variability, and facility downtime, which are particularly detrimental in a low-margin, high-volume industry [21]. This technical guide analyzes the strategic implementation of preprocessing depots, with a focused comparison between fixed and portable facility designs, to provide researchers and supply chain designers with a foundation for optimizing biomass logistics systems.

The Function and Impact of Preprocessing Depots

Core Preprocessing Operations and Technologies

Preprocessing depots transform raw biomass through a sequence of operations to enhance its material handling properties. The core technologies can be categorized as follows:

- Densification: This process increases the bulk density of biomass to reduce transportation and storage costs and to improve handling. Pelletizing and briquetting are the two primary densification technologies [22]. Pelletizing produces small, cylindrical particles, while briquetting typically creates larger blocks. A third, less intensive process is grinding, which reduces particle size but results in a lower final density compared to densification [22].

- Quality Standardization: Beyond physical formatting, depots can incorporate processes to improve or standardize chemical characteristics. Torrefaction, a mild pyrolysis treatment, can be included to reduce moisture content, increase energy density, and improve hydrophobic properties, thereby enhancing long-term storage stability [9].

- Centralized Storage and Preprocessing (CSP): The depot functions as a CSP hub, decoupling the seasonal and geographically dispersed biomass harvest from the continuous, high-volume demand of the biorefinery [22] [21]. This decoupling is vital for managing supply uncertainty and ensuring a consistent, year-round feedstock flow to the conversion facility.

System-Level Benefits for Supply Chain Reliability

The incorporation of a depot network introduces resilience and efficiency at the system level. Research using the Integrated Biomass Supply Analysis and Logistics (IBSAL) simulation model demonstrates that an advanced "pellet-delivery" system, which employs depots, significantly reduces biomass supply risk and protects against catastrophic disruptions like drought or pest infestation [21]. By accepting and processing variable-quality biomass from diverse sources into a uniform commodity, depots allow the supply chain to diversify its supply portfolio, thereby enhancing overall system robustness [21]. Furthermore, moving the challenging tasks of processing inconsistent bales from the biorefinery to the depot minimizes operational disruptions and maintenance costs at the primary conversion facility, directly boosting its uptime and economic performance [21].

Comparative Analysis: Fixed vs. Portable Preprocessing Depots

The strategic decision between implementing fixed or portable preprocessing facilities has profound implications for the capital expenditure, operational flexibility, and overall economics of the biomass supply chain. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of these two paradigms.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Fixed and Portable Preprocessing Depots

| Characteristic | Fixed Depots | Portable Depots |

|---|---|---|

| Capital Investment | High (significant infrastructure) [21] | Low to Moderate (mobile equipment) |

| Operational Scope | Large, centralized hub serving a wide region [9] [21] | Small, decentralized unit deployed near harvest sites |

| Feedstock Logistics | Longer transportation of raw biomass to the facility | Minimizes raw biomass transport distance; "move the processor, not the biomass" |

| Economies of Scale | High potential for achieving lower per-unit processing costs [21] | Limited by smaller, modular capacity |

| Flexibility & Mobility | Permanent location; limited adaptability to changing supply zones | High mobility; can be relocated to follow biomass availability |

| Typical Technology | Large-scale pelletizing, briquetting, torrefaction lines [22] | Grinding, baling, and possibly small-scale pelletizing |

| Ideal Use Case | High-volume, stable biomass supply regions; long-distance transport to biorefinery [22] | Regions with dispersed, low-density biomass; early-stage or pilot projects |

Quantitative Cost and Logistics Implications

The choice between fixed and portable depots directly impacts total supply chain costs, with the optimal configuration being highly sensitive to transportation distance.

- Long-Distance Supply Chains: For supply chains involving long-distance transportation, such as moving biomass from Illinois to California, fixed depots producing densified pellets lead to lower overall biofuel production costs [22]. The higher capital and processing costs of a fixed depot are offset by the dramatic savings in transporting a high-density commodity. For this long-haul scenario, moving ethanol is approximately $0.24 per gallon less costly than moving even densified biomass, making a fixed depot that supplies a local biorefinery the most economical model [22].

- Short-Distance Supply Chains: In contrast, for localized supply chains where the biorefinery is near the biomass source, the high capital and processing costs of pelletization in a fixed depot can make it less economical than a portable system or a conventional bale-based system [22]. In these contexts, the cost of densification may not be justified by minimal transportation savings.

- The Portable Depot Advantage: The primary economic advantage of portable depots lies in reducing the cost of transporting raw, low-density biomass [9]. By moving preprocessing equipment directly to the field edge, the most massive and cumbersome form of biomass is handled locally, and only a more transportable product is shipped. This strategy is particularly effective for feedstocks with very low initial density, such as agricultural residues.

Table 2: Cost Comparison for Alternative Supply Chain Configurations (Illinois to California)

| Preprocessing Technology | Transportation Mode | Relative Cost Implication | Key Cost Driver |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelletizing | Rail | Lowest cost for long-distance biomass transport [22] | High depot cost offset by low transport cost |

| Briquetting | Rail | Moderate cost | Balance of depot and transport cost |

| Grinding | Truck | Higher cost | High transportation cost for low-density material |

| None (Bale Transport) | Truck | Highest cost for long-distance [22] | Very high transportation cost |

Experimental and Modeling Approaches for Depot Analysis

Spatial Analysis for Facility Siting

Objective: To identify optimal geographic locations for fixed depots or deployment zones for portable units based on biomass availability and transportation networks.

Methodology:

- Biomass Inventory Mapping: Utilize spatial data layers, such as the Cropland Data Layer (CDL) and soil databases, to map biomass yield (e.g., corn stover) with high resolution [21].

- Suitability Analysis: Conduct a multi-criteria analysis considering factors like proximity to roads, railways, and existing infrastructure, as well as land-use constraints, to determine suitable sites [21].

- Location-Allocation Modeling: Apply Geographic Information System (GIS)-based models, such as the "maximize capacitated coverage" problem. This algorithm selects facility sites and allocates biomass supply from farms to these facilities in a way that maximizes the total biomass utilized without exceeding the capacity of any single facility [21]. The output defines the service area for each depot.

Discrete Event Simulation for System Reliability

Objective: To evaluate the dynamic performance and reliability of depot-integrated supply chains under operational disruptions.

Methodology:

- Model Development: Create a database-centric discrete event simulation (DES) model, such as the Integrated Biomass Supply Analysis and Logistics (IBSAL) platform [21]. This model simulates the flow of biomass (in various forms like bales and pellets) through every node in the supply chain over multiple years.

- Scenario Definition: Formulate specific scenarios for comparison, such as:

- Scenario 1: Conventional bale-delivery system with varying biorefinery uptime (20-85%).

- Scenario 2: Advanced pellet-delivery system with fixed depot uptime and varying biorefinery uptime.

- Scenario 3: Advanced pellet-delivery system with high, stable uptime at both depot and biorefinery [21].

- Performance Metric Tracking: The simulation model tracks key output metrics, including:

- Total Delivered Cost (broken down by harvest, storage, transport, and preprocessing).

- Inventory Levels at storage sites and facilities.

- Facility Utilization and Uptime.

- Tonnage Discarded at the field edge due to system bottlenecks [21].

- Result Analysis: Analyze the output to understand cost drivers and the "cascading effect" of failures, where a disruption at one facility (e.g., a depot) propagates through the entire system, impacting inventory and production levels elsewhere [21].

Optimization Modeling for Strategic Planning

Objective: To determine the least-cost configuration of the supply chain network, including the number, location, and type of depots.

Methodology:

- Model Formulation: Develop a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model, often referred to as a BioScope model, to synthesize the four-stage biomass-biofuel supply chain [22]. The model encompasses biomass supply, CSP, biorefinery, and biofuel distribution.

- Objective Function: The typical objective is to minimize the total supply chain cost, which is a function of fixed costs for establishing facilities and variable costs for transportation, preprocessing, and conversion [9] [22].

- Constraint Definition: The model is subject to constraints including:

- Biomass availability at each supply location.

- Processing capacities at depots and biorefineries.

- Demand requirements at the product distribution points.

- Mass balance equations for all material flows [9].

- Scenario Evaluation: The optimization model is run for multiple scenarios combining different preprocessing technologies and supply chain configurations to identify the most economical system design for a given context [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for designing and analyzing a depot-integrated biomass supply chain, integrating the methodologies described above.

Figure 1: BSC Design and Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Tools and Models for Biomass Supply Chain Research

| Tool/Model Name | Type | Primary Function in Depot Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| GIS (ArcMap, QGIS) | Spatial Analysis Software | Mapping biomass availability, conducting suitability analysis, and solving location-allocation problems for depot siting [21]. |

| MILP/MINLP Solver | Optimization Algorithm | Determining the least-cost network design, including the optimal number, location, and capacity of depots [23] [24]. |

| IBSAL Model | Discrete Event Simulation | Dynamically modeling material flow and quantifying the impact of operational disruptions (downtime, quality variance) on system costs and reliability [21]. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) | Sustainability Evaluation Tool | Quantifying the environmental impacts (e.g., GHG emissions) of different depot strategies and supply chain configurations [9] [24]. |

| Tool for Sustainability Impact Assessment (ToSIA) | Impact Assessment Framework | Evaluating the socio-economic and environmental impacts of different forest wood value chains, including those involving preprocessing depots [24]. |

| 4-Methoxy PCE hydrochloride | 4-Methoxy PCE hydrochloride, CAS:1933-15-9, MF:C15H24ClNO, MW:269.81 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 3-Hydroxyisopentyl-CoA | 3-hydroxy-3-methylbutyl-CoA|High-Purity Reference Standard | Research-grade 3-hydroxy-3-methylbutyl-CoA for biochemical studies. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or personal use. |

The integration of preprocessing depots is a pivotal strategy for developing a robust and economically viable biomass supply chain. The decision between fixed and portable facilities is not universal but must be guided by specific regional and operational contexts. Fixed depots are the cornerstone of large-scale, centralized bioenergy production, offering economies of scale and cost-effective logistics for long-distance transport, particularly when integrated with rail systems [22]. Conversely, portable depots provide a flexible, low-capital solution for tapping into geographically dispersed or low-density feedstock resources, effectively reducing the costs and challenges of moving raw biomass [9].

For researchers and supply chain designers, the path forward requires a systems-level approach. As simulation studies have revealed, mitigating risk at a single facility is insufficient; one must account for the cascading effects of disruptions that propagate from depots to biorefineries [21]. Therefore, future research and deployment should leverage the combined power of spatial analysis, optimization, and simulation modeling to design depot networks that are not only cost-minimized but also resilient to the inherent uncertainties of biomass supply. This holistic approach is critical for unlocking the full potential of advanced biofuels and bio-based products.

Advanced Modeling and Optimization Techniques for Efficient BSC Design

The design and management of a Biomass Supply Chain (BSC) is a complex process involving multiple strategic, tactical, and operational decisions. Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) has emerged as a powerful mathematical tool for optimizing these systems, enabling researchers and practitioners to address challenges related to cost efficiency, sustainability, and operational reliability. The BSC encompasses all activities from biomass harvesting to its conversion into energy or bio-based products, including collection, transportation, preprocessing, storage, and final conversion. Biomass, as a renewable resource, includes forest residues, agricultural waste, energy crops, and livestock waste, which can be transformed into various energy forms like chips, pellets, and briquettes. The inherent challenges of biomass—such as low energy density, seasonal availability, geographical dispersion, and variable composition—make optimization approaches particularly valuable for improving economic viability and environmental performance.

MILP models are exceptionally suited for BSC optimization because they can simultaneously handle continuous variables (e.g., biomass quantities, flow rates) and discrete integer variables (e.g., facility location decisions, technology selection, unit activation). This allows for the modeling of complex decisions involving yes/no choices, such as whether to open a preprocessing facility in a specific location, alongside continuous decisions about biomass flow between network nodes. The application of MILP spans all planning levels: strategic (facility location, capacity sizing), tactical (inventory planning, procurement strategies), and operational (production scheduling, transportation routing). Within the broader context of renewable energy systems research, MILP provides a quantitative foundation for evaluating trade-offs between economic objectives, environmental impacts, and social considerations in BSC design, supporting the transition toward more sustainable energy systems.

Core Components of Biomass Supply Chain Modeling

Fundamental System Structure

A typical biomass supply chain network is structured across multiple spatial and functional echelons, which are interconnected through material, information, and financial flows. The optimization of this network requires a systematic representation of all critical components and their interrelationships. The core echelons generally include biomass supply sources, collection points, preprocessing facilities, storage locations, conversion plants, and final demand centers. Biomass feedstock can originate from diverse sources such as agricultural residues, forestry waste, energy crops, and agro-industrial by-products, each with distinct characteristics affecting their logistical handling and processing requirements.

The spatial distribution of biomass resources presents a significant challenge for supply chain optimization. Biomass is often scattered across large geographical areas with varying availability densities, necessitating careful planning of collection and transportation routes to minimize costs. Furthermore, temporal factors such as seasonality of biomass availability and fluctuations in energy demand introduce additional complexity that must be incorporated into optimization models. MILP approaches excel at capturing these spatial and temporal dimensions through appropriate indexing and constraint formulation, enabling the development of comprehensive supply chain designs that remain feasible and efficient under real-world conditions.

Table: Key Echelons in Biomass Supply Chain Networks

| Echelon | Components | Function | Decision Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supply Sources | Agricultural fields, Forests, Processing plants | Generate biomass feedstocks | Harvest scheduling, Procurement planning |

| Collection & Preprocessing | Fixed depots, Portable depots, Storage facilities | Aggregate, preprocess, and store biomass | Technology selection, Facility location, Capacity planning |

| Transportation | Trucks, Trains, Barges | Move biomass between echelons | Mode selection, Route planning, Fleet sizing |

| Conversion | Biorefineries, Power plants, Combined heat and power (CHP) facilities | Transform biomass into energy/bio-products | Technology selection, Capacity expansion, Production planning |

| Demand Centers | Grid injection points, Fuel distributors, Industrial consumers | Utilize final bio-based products | Demand allocation, Inventory management |

Mathematical Formulation Framework

A generalized MILP formulation for BSC optimization typically includes an objective function to be minimized or maximized, subject to a set of constraints that define the system's operational and strategic limitations. The most common objective is cost minimization, though profit maximization and multi-objective approaches incorporating environmental and social criteria are increasingly prevalent. The core constraints in BSC MILP models encompass mass balance equations, capacity limitations, technology selection relationships, and demand fulfillment requirements.

The mass balance constraints ensure the conservation of biomass flow throughout the network, linking successive echelons and accounting for transformation factors during preprocessing and conversion operations. Capacity constraints define the upper and lower limits of processing, storage, and transportation capabilities across the network. Logical constraints enforce the relationship between discrete facility location decisions and continuous flow variables, typically using big-M formulations that activate or deactivate flow possibilities based on facility status. Additional constraints may address temporal aspects through multi-period formulations, inventory balancing equations, and seasonal availability restrictions.

The mathematical representation generally takes the following form:

- Objective: Minimize Total Cost = Harvesting Cost + Transportation Cost + Processing Cost + Storage Cost + Fixed Investment Cost

- Subject to:

- Biomass availability constraints at supply locations

- Flow conservation constraints at each node

- Capacity constraints for processing, storage, and transportation

- Demand fulfillment constraints for final products

- Logical constraints linking facility opening decisions to flows

- Non-negativity and integrality conditions

MILP Model Formulation for Biomass Supply Chain Design

Sets, Parameters, and Decision Variables

A comprehensive MILP formulation for BSC design begins with the definition of sets, parameters, and decision variables that mathematically represent the supply chain network. The sets define the structural elements of the system, including geographical locations, technology options, and time periods. Parameters quantify the economic and technical characteristics of the system, while decision variables represent the choices available to the supply chain designer.

Table: Essential Components of BSC MILP Formulation

| Component Type | Notation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sets | (i \in I) | Set of biomass supply locations (watersheds, fields) |

| (j \in J) | Set of potential preprocessing depot locations | |

| (k \in K) | Set of energy conversion facilities | |

| (t \in T) | Set of time periods | |

| (m \in M) | Set of portable depot types | |

| Parameters | (H_{it}) | Cost of harvesting at watershed (i) in period (t) |

| (C_{ij}) | Cost of transporting biomass from (i) to (j) | |

| (F_j) | Fixed cost of establishing facility at location (j) | |

| (P_{kt}) | Price of final product at conversion facility (k) in period (t) | |

| (Cap_j) | Processing capacity at facility (j) | |

| (A_{it}) | Biomass availability at supply location (i) in period (t) | |

| Decision Variables | (x_{ijt}) | Continuous: Quantity of biomass shipped from (i) to (j) in period (t) |

| (y_j) | Binary: 1 if facility (j) is established, 0 otherwise | |