Optimizing Biomass Combustion: Advanced Strategies for Residence Time Control and Efficiency Enhancement

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to optimize biomass combustion, focusing on the critical relationship between residence time and system efficiency.

Optimizing Biomass Combustion: Advanced Strategies for Residence Time Control and Efficiency Enhancement

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of strategies to optimize biomass combustion, focusing on the critical relationship between residence time and system efficiency. It explores foundational combustion science, advanced methodological approaches including Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and machine learning, troubleshooting for common operational challenges, and validation through comparative case studies. Tailored for researchers and engineers in renewable energy, this review synthesizes recent technological advancements in torrefaction pretreatment, air distribution optimization, and AI-assisted modeling to achieve superior combustion performance, reduced emissions, and enhanced economic viability for sustainable power generation.

The Science of Biomass Combustion: Understanding Residence Time and Efficiency Fundamentals

Fundamental FAQ: The Combustion Process

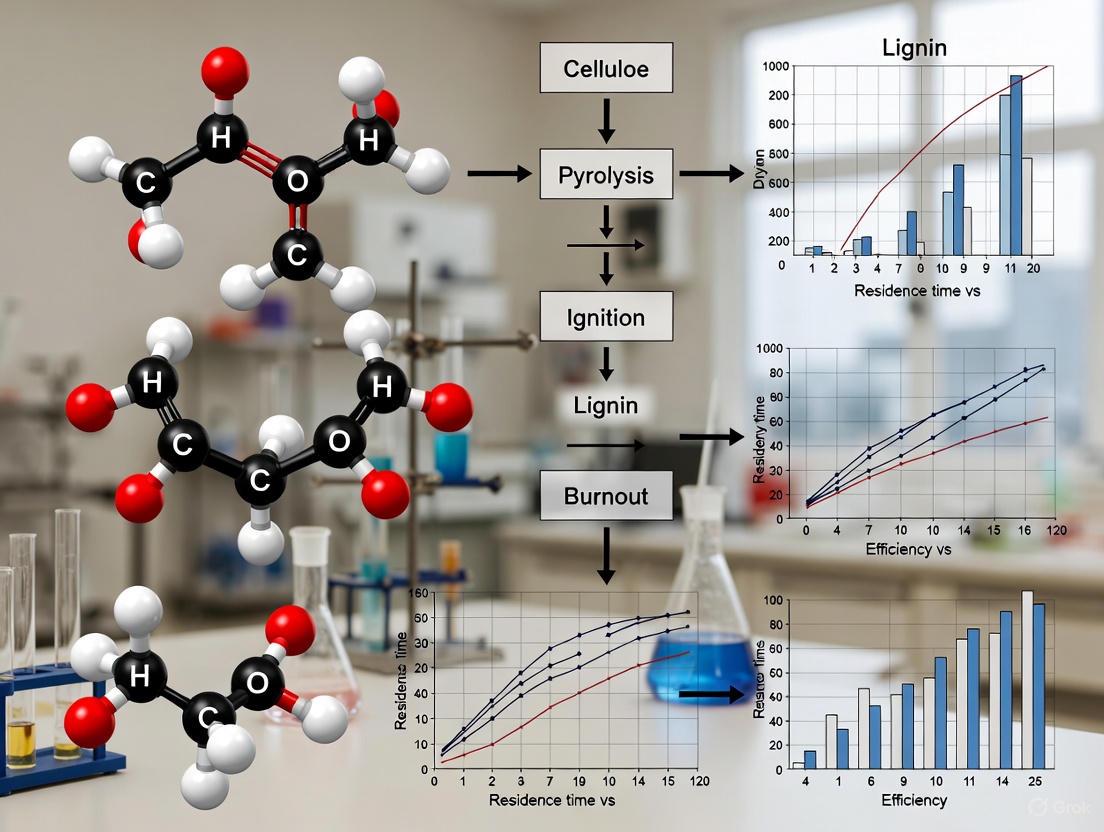

What are the distinct phases of the biomass combustion process? Biomass combustion is a complex thermochemical conversion that occurs in three sequential, sometimes overlapping, phases [1]:

- Drying and Devolatilization: The initial phase where biomass is heated, moisture is evaporated, and volatile gases are released from the solid fuel.

- Volatile Combustion: The released volatile gases mix with air and ignite, producing a visible flame. This is a high-temperature, flaming combustion stage.

- Char Burnout: The remaining solid carbonaceous material (char) undergoes surface oxidation. This stage is characterized by glowing embers and is typically the longest phase [1].

How does combustion efficiency relate to these phases? Efficiency is highly dependent on the control and completion of each phase. An unbalanced process can lead to excessive carbon monoxide (CO) emissions from incomplete volatile combustion or unburned carbon in the ash from incomplete char burnout. Stabilizing the combustion process, for instance through automated fuel feeding, has been shown to significantly reduce CO emissions and increase the Combustion Efficiency Index (CEI) [1].

What is the role of residence time in optimizing combustion? Adequate residence time in the high-temperature zone is critical, especially for the char burnout phase. If the char is not allowed sufficient time to fully combust, unburned carbon is lost as ash, reducing fuel efficiency and increasing emissions. Optimizing the gasification stage for 0.6 seconds at 1100°C has been shown to significantly improve syngas quality, demonstrating the importance of time-temperature relationships [2].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ: Our experiments are yielding inconsistent combustion efficiency and emission values. What could be causing this variability? Inconsistent results are often traced to unstable fuel properties or combustion conditions.

- Root Cause: Non-uniform fuel quality (e.g., variable moisture content, particle size, or density) and manual, batch-type fuel feeding can create a fluctuating combustion environment [1] [3].

- Solution: Implement an automated fuel feeding system. Research shows that switching from manual batch feeding to an automated gutter burner system stabilizes the process, balances combustion between different biomass types (herbaceous vs. woody), and significantly reduces disparities in CO₂ and CO emissions [1]. Furthermore, ensure the use of standardized, densified biofuels like pellets with consistent properties.

FAQ: We observe high carbon monoxide (CO) emissions and unburned fuel in the ash. What does this indicate and how can it be resolved? This is a classic sign of incomplete combustion, which can stem from several issues related to the core combustion phases [4] [1]:

- Insufficient Air Supply: Check that combustion air fans are functional and air vents are not blocked. Inadequate oxygen prevents complete oxidation of volatile gases and char [4].

- Restricted Airflow: Free passage of air and flue gases is essential. Check for blockages in the emissions path, as this can cause poor combustion and lead to unburned fuel in the ash chamber [4].

- Inadequate Temperature: Ensure the combustion chamber reaches and maintains a high enough temperature for volatile cracking and char oxidation. At 1100°C, tar cracking reactions proceed to completion [2].

FAQ: During gasification experiments, our H₂/CO ratio is too low for synthesis applications. How can we improve it? Traditional gasification often suffers from a low H₂/CO ratio. A process modification can effectively address this.

- Solution: Implement a three-stage gasification process. This involves separating pyrolysis products (volatiles and char) before the main gasification step. The char undergoes first-stage gasification, and the pyrolysis gas is introduced for a second gasification stage. This method prevents hydrogen in the volatiles from being consumed early by oxygen and has been shown to increase the H₂/CO ratio from 0.86 to 1.23, making it suitable for Fischer-Tropsch synthesis without needing extra process steps [2].

Quantitative Data for Experimental Comparison

The following tables summarize key experimental data from recent studies to serve as benchmarks for your research.

Table 1: Emission Profiles and Combustion Efficiency of Different Biofuels

| Fuel Type | Combustion System | CO (ppm) | NO (ppm) | SO₂ (ppm) | Combustion Efficiency Index (CEI) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Producer Gas (Optimized MILD) | Circular Chamber | ~5 ppm | ~11 ppm | - | - | [5] |

| Wheat Straw Pellets | Automated Gutter Burner | Low | High | - | High | [1] |

| Rye Straw Pellets | Automated Gutter Burner | Low | High | - | High | [1] |

| Oat Straw Pellets | Automated Gutter Burner | Low | High | - | High | [1] |

| Birch Sawdust Pellets | Automated Gutter Burner | Low | High | - | High | [1] |

Table 2: Characteristics of Selected Biomass Char for Injection

| Biomass Char Sample | Fixed Carbon (%) | Volatile Matter (%) | Ash Content (%) | Calorific Value (MJ·kg⁻¹) | Burnout Rate (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiangsu Suzhou Woodblock (B3) | - | - | Low | - | 77.12 | [6] |

| Jiangsu Changzhou Branch (B8) | - | - | Low | - | 67.03 | [6] |

| Herbaceous Biomass Pellets | - | - | 2-4x higher than wood | 15.47-16.29 | - | [1] |

| Birch Sawdust Pellets | - | - | Low | 16.34 | - | [1] |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Optimization of Combustion Residence Time and Staging

Objective: To maximize combustion efficiency and syngas quality (H₂/CO ratio) by controlling reaction residence time and separating pyrolysis and gasification phases.

Methodology:

- Setup: Utilize a high-temperature entrained-flow bed gasification system equipped with a separate pyrolysis unit, controlled feeding system, and syngas analysis (GC) [2].

- Pyrolysis: Subject biomass (e.g., sawdust) to pyrolysis. Analyze the resulting gas composition (typically containing H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) and produce char [2].

- Staged Gasification:

- Analysis: Continuously monitor the composition of the final syngas (H₂, CO, CO₂) and calculate the H₂/CO ratio. Compare results against a traditional single-stage gasification process.

Visual Workflow:

Protocol: Analysis of Combustion Efficiency and Emissions

Objective: To evaluate the combustion efficiency and ecological impact of different solid biofuels under varying operational modes (manual vs. automated feeding).

Methodology:

- Fuel Preparation: Prepare and characterize densified biofuels (pellets/briquettes) from various feedstocks (e.g., woody sawdust, wheat straw, rye straw). Conduct proximate and ultimate analysis [1].

- Combustion Testing: Burn fuels in a test boiler system with two configurations:

- Type A: Traditional grate-fired system with periodic manual fuel feeding.

- Type B: Modified system with an automatic gutter burner for continuous fuel feeding [1].

- Data Collection: During timed tests, continuously measure:

- Flue gas composition: CO₂, CO, NO, SO₂ concentrations.

- Temperatures: supplied air and exhaust gases [1].

- Calculation: Determine key performance indicators:

- Stack Loss (qA): Energy lost in the flue gases.

- Combustion Efficiency Index (CEI): Indicator of energy yield.

- Toxicity Index (TI): CO/CO₂ ratio, indicating completeness of combustion [1].

Visual Workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Analytical Tools for Biomass Combustion Research

| Item | Function / Relevance in Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Standardized Biomass Pellets | Ensure consistent fuel properties (size, density, moisture) for reproducible experiments. | Woody (e.g., Birch Sawdust), Herbaceous (e.g., Wheat Straw, Rye Straw) [1]. |

| Biomass Chars | Used to study the char burnout stage and as a potential clean injection fuel. | Pyrolysis-derived chars (e.g., Woodblock char, Branch char) with low ash and high fixed carbon [6]. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Essential for detailed analysis of syngas composition (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) during gasification experiments [2]. | - |

| Flue Gas Analyzer | Measures real-time concentrations of key emission species (O₂, CO, CO₂, NOx, SO₂) for efficiency and emissions calculations [1]. | - |

| Hardgrove Grindability Index (HGI) | Determines the ease of pulverizing biomass char, a critical property for injection fuel preparation [6]. | Standard grindability tester. |

| TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) Data | Satellite data can provide large-scale validation for combustion efficiency (ΔXNO₂/ΔXCO ratio) over different regions [7]. | Used for spatial analysis of flaming vs. smoldering dominance. |

For researchers and scientists focused on thermo-chemical conversion processes, residence time is a fundamental parameter defining the duration a fuel particle remains within a combustion or gasification zone. Achieving complete combustion and maximizing efficiency in biomass systems requires precise control over residence time, which directly influences fuel conversion rates, heat release profiles, and emission levels. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and methodological support to address common experimental challenges in measuring and optimizing residence time within biomass combustion research.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Residence Time Challenges

FAQ 1: How do I accurately measure biomass residence time in a fluidized bed reactor?

Challenge: Inaccurate measurement of solid fuel residence time leads to incomplete char burnout and unpredictable heat release.

Solution: Implement a bed temperature and pressure monitoring method to identify characteristic conversion phases.

- Experimental Protocol: Monitor and record bed temperature and fluid pressure over time during conversion. The characteristic temperature profile identifies two key phases [8]:

- Devolatilization Time: The initial rapid temperature rise indicating volatile release and combustion.

- Extinction Time: The point where temperature stabilizes, signaling the end of char combustion.

- Data Interpretation: The period between devolatilization and extinction represents the active char conversion residence time. Correlations show this time increases with decreasing air flowrate and increasing biomass load [8].

FAQ 2: Why does my biomass combustor have high unburned carbon despite adequate temperature?

Challenge: High unburned carbon (char) and suboptimal combustion efficiency.

Solution: Evaluate and optimize the relationship between residence time and operating conditions.

- Root Cause: The residence time of char particles is insufficient for complete conversion, often due to high air flowrates or poor solid circulation [8].

- Experimental Validation: In circulating fluidized bed (CFB) systems, monitor Unburned Carbon (UBC) levels. Correlations exist between UBC, air flowrate, and biomass load. For example, one CFB study achieved UBC as low as 0.7% with optimized co-firing conditions [9].

- Mitigation Strategy: To decongest accumulated char, determine the required solid circulation rate and adjust bed hydrodynamics (e.g., air staging, PA/TA ratios) to increase effective residence time [8].

FAQ 3: How does fuel blending impact required residence time and system stability?

Challenge: Co-firing biomass with other fuels (e.g., ammonia, coal) disrupts combustion stability and pollutant emissions.

Solution: Systematically adjust fuel ratios and injection positions to manage heat release and residence time profiles.

- Key Findings: Coal-biomass-ammonia co-firing experiments reveal that injection position significantly affects combustion. Ammonia injected into the dense bed zone (DBZ) can disrupt coal combustion, elevating CO emissions, whereas injection into the wind box (WB) can simultaneously reduce NO and CO without sacrificing efficiency [9].

- Protocol: For multi-fuel systems:

- Start with a lower biomass ratio (e.g., 8%) for stable temperature and pressure profiles.

- For carbon-free fuels like ammonia, optimize the injection position and velocity to ensure complete combustion without delaying solid fuel conversion [9].

Experimental Data & Operating Parameters

The following tables summarize key quantitative relationships from experimental studies to guide your parameter selection.

Table 1: Biomass Residence Time and Char Yield vs. Operating Conditions [8]

| Air Flowrate | Biomass Load | Devolatilization Time | Extinction Time | Unconverted Char Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreases | Increases | Increases | Increases | Increases |

| Increases | Decreases | Decreases | Decreases | Decreases |

Table 2: Impact of Fuel Moisture on Combustion Efficiency and Emissions [10]

| Moisture Content | Effective Heating Value | Boiler Thermal Efficiency | CO Emissions |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 16.8 MJ/kg | 90% | <200 mg/Nm³ |

| 20% | 15.2 MJ/kg | 85% | 250 mg/Nm³ |

| 30% | 13.5 MJ/kg | 80% | 350 mg/Nm³ |

| 40% | 11.6 MJ/kg | 72% | 500 mg/Nm³ |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Analytical Tools for Combustion Research

| Item | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| Circulating Fluidized Bed (CFB) System | Provides a versatile platform for studying solid fuel residence time, co-firing, and pollutant formation under conditions mimicking practical boilers [9]. |

| Silica Sand (Bed Material) | Serves as an inert heat transfer medium and reaction surface in fluidized bed combustion and gasification experiments [9]. |

| Portable Gas Analyzer | Measures real-time flue gas concentrations (O₂, CO, NOₓ, etc.) critical for calculating combustion efficiency and emission profiles [11]. |

| Biomass Pellets (Wood, Agro-residues) | Standardized solid fuel forms with varying volatile, ash, and moisture content for studying the impact of fuel properties on residence time and conversion [11] [10]. |

| Preheating System for Primary Air | An experimental variable used to study its effect on combustion stability and fuel-N conversion, particularly in ammonia or high-moisture biomass co-firing [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Characteristic Biomass Residence Time

This workflow details the method for measuring biomass residence time in a bubbling fluidized bed, based on proven experimental approaches [8].

Workflow for Measuring Biomass Residence Time

Objective: Determine the mean biomass residence time during the conversion period at a given air flowrate and biomass load [8]. Materials: Bubbling fluidized bed reactor, thermocouples, pressure sensors, data acquisition system, prepared biomass sample. Procedure:

- Charge Biomass into Pre-heated Bed: Introduce a known mass of biomass into the stabilized, pre-heated bed.

- Record Bed Temperature and Pressure: Continuously record the bed temperature and fluid pressure at high frequency throughout the conversion process.

- Identify Devolatilization Time: Analyze the temperature trace to identify the sharp peak corresponding to the maximum rate of devolatilization.

- Identify Extinction Time: Identify the point where the temperature stabilizes, marking the end of the significant char combustion phase.

- Calculate Residence Time: The biomass residence time is characterized by the period between the devolatilization time and the extinction time. Correlations can then be developed to predict this time based on air flowrate and biomass load [8].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does high moisture content negatively impact biomass combustion efficiency? High moisture content significantly reduces combustion efficiency by absorbing thermal energy to evaporate water before combustion of the solid matter can begin. This process lowers flame temperature, delays ignition, and increases stack heat losses. Fuels with 50-55% moisture content can experience efficiency losses of 20-25% compared to dry fuels with only 6-10% moisture content [12].

Q2: What operational problems are caused by high ash content in biomass fuels? High ash content leads to several operational challenges including slagging, fouling, clinker formation, and increased maintenance requirements. Ash composition is particularly important - fuels with high silica content (like rice husk) or alkaline compounds fuse at lower temperatures, creating molten slag deposits that can block grates and damage furnace walls [13] [12].

Q3: Why does biomass with high volatile matter require special combustion considerations? Biomass with high volatile matter (such as agricultural straw) ignites easily and burns quickly, which can lead to incomplete combustion and elevated CO emissions if not properly managed. These fuels require staged air injection systems and multi-zone air control to manage flame propagation and ensure complete combustion [12].

Q4: How does fuel calorific value affect boiler sizing and operation? Lower calorific value fuels require larger furnace volumes, higher fuel mass flow rates, and longer residence times to sustain the same steam production. For example, fresh bagasse with a calorific value of 7-9 MJ/kg requires 350-500 kg/h to produce 1 TPH of steam, while wood pellets at 16-19 MJ/kg only need 180-200 kg/h for the same output [12].

Troubleshooting Common Combustion Problems

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Biomass Combustion Issues

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions | Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| High CO Emissions | Insufficient combustion residence time, inadequate air staging, low furnace temperature | Increase secondary air supply, optimize air distribution zones, pre-heat combustion air | Staged air injection can reduce CO emissions by up to 50% [12] [14] |

| Slagging and Clinker Formation | High ash content with low melting point compounds (silica, alkali metals) | Use alternative biomass with lower ash content, install air-cooled ash systems, employ fuel blending | Rice husk (15-20% ash) high risk vs. wood pellets (<1% ash) minimal risk [12] |

| Low Combustion Efficiency | High moisture content, low calorific value, insufficient furnace volume | Implement fuel pre-drying, increase furnace size, optimize excess air ratio | 30-40% moisture causes 8-15% efficiency loss; 50-55% moisture causes 20-25% loss [12] |

| Incomplete Burnout | Insufficient residence time in high-temperature zone, poor fuel-air mixing | Increase combustion chamber volume, optimize burner design, ensure proper particle size reduction | MILD combustion optimization achieved 0.76 Damköhler number for complete combustion [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomass Property Analysis

Protocol: Determining Combustion Kinetics Using Two-Step Reaction Analysis

Purpose: To measure combustion characteristics and kinetic parameters of in-situ biomass char while avoiding reactivity changes caused by cooling processes [15].

Materials and Equipment:

- Two-step reaction analyzer (decouples pyrolysis and combustion)

- Biomass samples (50-150 μm particle size)

- Gas analyzers (CO, CO₂ measurement)

- Temperature control system (300-800°C range)

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) for ash structure analysis

Procedure:

- Prepare biomass samples by grinding and sieving to 50-150 μm particle size

- Load sample into two-step reaction analyzer

- Heat to pyrolysis temperature (600-700°C) under inert atmosphere

- Immediately introduce combustion atmosphere (air/O₂) without cooling

- Measure reaction rates at multiple temperatures (688K, 713K, 738K, 763K)

- Analyze gas composition continuously using IR gas analyzers

- Calculate carbon conversion rate using CO/CO₂ production data

- Collect ash samples for structural analysis using SEM

Data Analysis:

- Calculate activation energy using Arrhenius equation

- Compare reaction rates between in-situ char and traditionally prepared (cooled) char

- Analyze ash particle structure and residual carbon content

Protocol: Evaluating Biomass Pellet Performance in Domestic Boilers

Purpose: To determine combustion characteristics and emissions of various biomass pellets in small-scale heating systems [14].

Materials and Equipment:

- 10 kW domestic biomass boiler with pellet burner

- Biomass pellets (6-8 mm diameter)

- Flue gas analyzer (CO, CO₂, NOx measurement)

- Thermocouples (type K, range -200°C to +1200°C)

- Fuel consumption measurement system

Procedure:

- Obtain biomass pellets meeting EN-ISO-17225-2:2014 standard dimensions

- Set boiler thermostat to fixed temperature (60°C)

- Measure initial fuel mass

- Ignite pellets and operate boiler until stable combustion achieved

- Measure temperature distribution in combustion chamber (300-800°C range)

- Sample flue gases every 5 minutes for 30-minute period

- Analyze CO, CO₂, and NOx concentrations

- Measure final fuel mass to determine consumption rate

- Compare experimental results with numerical modeling (ANSYS Chemkin-Pro)

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table: Essential Research Materials for Biomass Combustion Studies

| Material/Reagent | Specification | Research Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wood Pellets | 6-8 mm diameter, <10% moisture, <1% ash content [12] | Baseline combustion studies | Reference fuel with consistent properties |

| Agricultural Biomass | Straw, corn stover, switch grass (8-25% moisture) [13] [14] | High-volatile fuel studies | Model for fast-igniting, high-volatile fuels |

| High-Ash Biomass | Rice husk (15-20% ash), barked wood pellets (>1.86% ash) [13] [12] | Slagging and fouling studies | Testing ash behavior and deposit formation |

| Coconut Husk | Low heating value, minimal emissions [16] | Low-emission combustion research | Fuel for achieving minimal CO₂ (2.03%) and CO (0.022%) |

| ANSYS Chemkin-Pro | Reaction kinetics simulation software [14] | Numerical modeling of combustion | Predicting pollutant formation using reaction mechanisms |

| Two-Step Reaction Analyzer | Decouples pyrolysis/combustion [15] | Kinetic parameter measurement | Analyzing in-situ char reactivity without cooling artifacts |

Biomass Property Relationships and Experimental Workflows

Biomass Property Impact on Combustion Performance

Biomass Combustion Experiment Workflow

Table: Comprehensive Biomass Property and Combustion Characteristics Data

| Biomass Type | Moisture (%) | Calorific Value (MJ/kg) | Ash Content (%) | CO Emissions | NOx Emissions | Combustion Efficiency | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood Pellets | 6-10 [12] | 16-19 [12] | <1 [12] | Low [14] | <368 ppm NO [14] | 69-75% [13] | Low availability, higher cost |

| Grass Pellets | 10-25 [12] | 12-16 [12] | 5-10 [12] | ~5000 ppm in some cases [13] | Similar to wood pellets [13] | 69-75% [13] | High ash, regular servicing required |

| Sunflower Husks | 8-20 [14] | 17.27 [14] | Medium | High CO₂ [14] | Medium NOx [14] | Similar to willow [14] | Variable composition |

| Coconut Husk | Not specified | Lower LHV [16] | Not specified | 0.022% [16] | Low | Not specified | Lower chamber pressure (20.84 bar) [16] |

| Agricultural Straw | 10-25 [12] | 12-16 [12] | 5-10 [12] | High without air staging [12] | Not specified | Reduced without optimization | High volatile matter, slagging |

| Palm Kernel Shells | 10-20 [12] | 17-20 [12] | 2-5 [12] | Not specified | Not specified | High with proper design | High alkali content, dense fuel |

This technical support resource is framed within a broader thesis on optimizing biomass combustion residence time and efficiency. A precise understanding of the four core thermochemical stages—Drying, Pyrolysis, Oxidation, and Reduction—is fundamental to troubleshooting experimental gasification systems, improving syngas quality, and achieving higher conversion efficiencies. The following guides and FAQs address specific, high-priority issues researchers encounter.

The Core Processes and Common Experimental Challenges

The following diagram illustrates the four main stages of biomass gasification and their key outputs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is the syngas from my lab-scale fluidized bed gasifier contaminated with high levels of tars that foul my analysis equipment and downstream catalysts?

High tar content typically results from inadequate temperature management in the pyrolysis and oxidation zones and/or insufficient residence time for cracking reactions. Tars are primary products of pyrolysis (Stage 2) that must be broken down in the subsequent oxidation and reduction stages [17] [18].

- Root Cause: The pyrolysis zone may be operating at a lower-than-optimal temperature, producing heavy tertiary tars that are difficult to crack. Furthermore, if the oxidation zone temperature is below approximately 800-900°C or gas mixing is poor, the tar cracking reactions (CnHm → nCO + (m/2)H2) will not proceed to completion [17] [19].

- Solution: Ensure your reactor's oxidation zone is maintained at high temperature. In fluidized bed systems, this often involves optimizing the air flow (Equivalence Ratio) and ensuring good bed material circulation to act as a heat vector. Introducing catalytic bed materials (e.g., dolomite, certain ashes) can also lower the activation energy required for tar cracking [20].

FAQ 2: My experiments show low gasification efficiency and high char yield. Which process parameter should I investigate first regarding residence time?

The most critical parameter to investigate is the residence time of solid biomass and char particles during the pyrolysis and reduction stages, which is heavily influenced by your reactor's hydrodynamic conditions and air flowrate [8].

- Root Cause: Biomass conversion is characterized by devolatilization and extinction times. If the residence time of the fuel particles is too short, unconverted char particles will accumulate. Research confirms that biomass residence time increases with decreasing air flowrate, and the amount of unconverted char also increases with a lower Equivalence Ratio (ER) and higher biomass load [8].

- Solution: For a fluidized bed reactor, correlate the air flowrate and biomass feed rate to prevent char accumulation. A methodology using the variation of bed temperature and fluid pressure over time can be employed to measure the actual biomass residence time during conversion in your experimental setup [8].

FAQ 3: The produced syngas has a lower heating value than expected. How can the reduction stage be optimized to improve H₂ and CO content?

A weak reduction stage, often due to insufficient heat supply or a poor char bed structure, leads to poor conversion of CO₂ and H₂O into combustible CO and H₂ [17] [21].

- Root Cause: The reduction reactions (C + CO₂ → 2CO and C + H₂O → CO + H₂) are highly endothermic. The heat for these reactions is supplied by the oxidation zone. If the thermal linkage between the zones is inefficient or the hot char bed is too thin, the reactions cannot proceed effectively [17].

- Solution: Ensure the oxidation zone provides sufficient thermal energy to sustain the reduction zone temperatures between 700-900°C. Optimizing the ER is critical; too much air will over-oxidize the char, while too little will not provide enough heat. Furthermore, using biomass with a high fixed carbon content can create a more reactive char bed for the reduction reactions [17] [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: Key Operational Issues and Protocols

Problem: High Particulate Matter (SP) in Raw Syngas

- Observed Symptom: Rapid fouling of filters, abrasive wear on engine components or sampling systems, and opaque gas stream.

- Underlying Stage: Incomplete solid conversion across all stages; primarily an issue of solid-gas separation.

- Experimental Protocol for Mitigation:

- Pre-Filtration: Install a high-temperature cyclone upstream of sensitive equipment to remove coarse particulates [18].

- Barrier Filtration: Use sintered metal or ceramic candle filters operated above the dew point of tars (typically > 500°C) to prevent the formation of a sticky, tar-bonded filtration cake that clogs the filter [18].

- Feedstock Control: Analyze the ash content of your biomass. High ash content can lead to agglomeration in fluidized beds and increased particulate load. Consider blending feedstocks or using pre-washed biomass [21].

Problem: Incomplete Combustion and High CO Emissions in Syngas Burner

- Observed Symptom: Syngas flame is unstable or sooty; flue gas analysis shows high CO levels during combustion trials.

- Underlying Stage: This is a burner design and operation issue related to the combustion of the final syngas product.

- Experimental Protocol for Mitigation:

- Optimize Equivalence Ratio (ER): For near-complete combustion in a swirl burner, the ER (actual air to fuel ratio relative to stoichiometric) must be significantly greater than 1. One study achieved stable, clean combustion at an ER of 2.6 [22].

- Improve Mixing: Ensure the burner design promotes turbulent and thorough mixing of syngas with combustion air. Consider low-swirl burner designs [22].

- Temperature and Residence Time: Maintain a combustion chamber temperature between 1000°C and 1300°C and ensure sufficient residence time (e.g., > 0.5 seconds) to complete the oxidation of CO to CO₂ [22].

Quantitative Data for Experimental Planning

The table below summarizes critical parameters for the four gasification stages, essential for designing and optimizing experiments.

Table 1: Key Operational Parameters for the Four Gasification Stages

| Stage | Temperature Range (°C) | Primary Inputs | Primary Outputs | Reaction Enthalpy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drying | 100 - 200 °C [19] [21] | Wet Biomass | Dry Biomass, Water Vapor | Endothermic [21] |

| Pyrolysis | 200 - 700 °C [19] | Dry Biomass | Char, Tar, Volatiles (CO, CO₂, H₂, CH₄) [17] [19] | Endothermic [17] |

| Oxidation | 800 - 1200 °C (est.) | Char, Volatiles, O₂ | CO, CO₂, H₂O, Heat | Highly Exothermic [17] [21] |

| Reduction | 700 - 900 °C [21] | Char, CO₂, H₂O, Heat | CO, H₂ [17] | Endothermic [17] [21] |

The following table provides key metrics for designing and analyzing gasification experiments, particularly those focused on efficiency and output.

Table 2: Typical Gasification Performance Metrics and Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Range / Value | Relevance to Experimentation |

|---|---|---|

| Syngas LHV (Lower Heating Value) | 5,000 - 6,000 kJ/Nm³ [20] | Key indicator of gas quality and process performance. |

| Cold Gas Efficiency | ~70% [20] | Measure of the conversion efficiency from biomass energy to syngas energy. |

| Equivalence Ratio (ER) | ~0.29 (for fluidized bed air gasification) [20] | Critical operational parameter balancing gas quality and temperature. |

| Stoichiometric Air (Y) | ~5.27 Nm³ air/kg dry biomass [20] | Used to calculate the actual air flowrate required for a given ER and biomass feed rate. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Biomass Gasification Research

| Item | Function in Experimentation |

|---|---|

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) Foam | Used as an inert, high-temperature packing material in packed bed reactors to significantly enhance heat transfer efficiency from the external source (e.g., solar heater) to the biomass [23]. |

| Fluidized Bed Material (e.g., Silica Sand) | Acts as a heat transfer medium and fluidizing agent in fluidized bed reactors, ensuring isothermal conditions and preventing hot spots [20]. |

| Catalytic Bed Materials (e.g., Dolomite, Olivine) | In-situ catalysts for tar cracking and gas reforming, reducing the tar content in the product gas and altering the H₂/CO ratio [19]. |

| Gasifying Agents (Air, O₂, Steam) | The reactant medium for partial oxidation. The choice of agent (e.g., air vs. steam) drastically affects syngas heating value and composition [19] [21]. |

| Barrier Filters (Sintered Metal/Ceramic) | For high-temperature removal of solid pollutants (SP) from raw syngas, crucial for protecting downstream engines, turbines, or analytical equipment [18]. |

The pursuit of optimized biomass combustion—specifically, the fine-tuning of residence time and process efficiency—is fundamentally challenged by three inherent properties of raw biomass: its high volatile matter content, the subsequent formation of condensable tars, and the corrosive potential of its alkali metal constituents. Effective combustion requires distinct, well-controlled residence times for the sequential phases of devolatilization, volatile combustion, and char burnout [24]. High volatile content can lead to rapid gas release, disrupting this balance and consuming available oxygen, which in turn promotes incomplete combustion and tar formation [24]. These tars, a complex mixture of heavy hydrocarbons, can condense on reactor surfaces, fouling systems and impeding heat transfer [24]. Concurrently, alkali metals (primarily potassium) present in the biomass ash can form low-melting-point compounds that deposit on heat exchange surfaces and aggressively corrode metals, directly undermining the efficiency and longevity of combustion systems [25] [3]. This technical support center addresses these specific challenges, providing researchers with targeted troubleshooting and methodologies to isolate and overcome these barriers in experimental settings.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Core Challenges

FAQ 1: How do high volatiles and tar content disrupt the intended residence time in a combustion reactor?

High volatile matter causes a rapid, intense release of gases upon heating, which can shorten the effective residence time for the complete combustion of these gases if the reactor design and airflow are not optimized [24]. This can lead to incomplete combustion, characterized by high carbon monoxide (CO) emissions and the formation of tar aerosols. Tars can be transported through the system as vapors or aerosols and may not follow the same flow path as solid particles, further complicating residence time predictions [24]. In essence, the intended residence time for complete oxidation is compromised when the volatile release profile does not align with the reactor's mixing and temperature conditions.

FAQ 2: Why is herbaceous biomass (e.g., straw, hay) more prone to causing alkali corrosion than woody biomass?

Herbaceous biomasses typically contain significantly higher concentrations of alkali metals like potassium [1]. During combustion, these elements are released and can form compounds such as potassium chloride (KCl) or potassium hydroxide (KOH) in the flue gas [1]. These compounds can deposit on heat exchanger surfaces, and in combination with other flue gas constituents like sulfur, form sticky, low-melting-point ashes that directly corrode metal surfaces through high-temperature corrosion mechanisms [3]. Analyses show the ash content for herbaceous biomass can be 2 to 4 times higher than for woody biomass, with similarly elevated levels of sulfur and other problematic elements [1].

FAQ 3: What is the relationship between combustion efficiency and the emissions of CO and NOx?

The combustion efficiency index (CEI) is often negatively impacted by high emissions of carbon monoxide (CO), which is a direct indicator of incomplete combustion [1]. An increase in CO signifies that the residence time, temperature, or mixing conditions in the combustor were insufficient to fully oxidize the fuel's carbon content. In contrast, nitrogen oxides (NOx) formation is complex; it is influenced by both fuel nitrogen content and combustion temperature. Research indicates that automating the fuel feed to stabilize the combustion process can significantly reduce CO emissions (improving efficiency) but may concurrently lead to an observed increase in NO emissions due to more stable, high-temperature conditions favorable to thermal NOx formation [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Setback and Solutions

Problem: Incomplete Combustion and High Tar Yields

- Observed Symptoms: High CO emissions, visible tar aerosols (yellow/brown deposits on filters or probe surfaces), and swirling patterns of different colored tars indicating separate combustion pathways [24].

- Underlying Mechanism: The combustion process is starved of oxygen or time in the volatile combustion phase. This is often due to a mismatch between the rapid devolatilization rate and the available air supply or combustion volume, leading to low-temperature, oxygen-deficient zones where tars form instead of fully oxidizing [24].

- Experimental Solutions:

- Staged Air Supply: Implement a multi-stage air injection system. Introduce primary air to maintain the fuel bed and secondary (or even tertiary) air higher in the combustion chamber to ensure turbulent mixing and complete oxidation of volatiles [24].

- Increase Residence Time: Modify the reactor geometry to create a larger post-combustion zone or incorporate a residence time extension chamber. This provides additional time and temperature for tar cracking and CO oxidation.

- Optimize Fuel Feed Rate: Avoid overfeeding the reactor. A steady, controlled feed rate prevents volatile overload and helps maintain a stable, high-temperature combustion environment. Automated feeding systems have been shown to stabilize the process and reduce CO emissions [1].

Problem: Alkali Metal Deposition and Corrosion

- Observed Symptoms: Glazed or fused deposits on probe tips, heat exchanger surfaces, and reactor liners; rapid thinning or pitting of metal components; and degraded heat transfer performance.

- Underlying Mechanism: Alkali metals (K) vaporize during combustion and then condense on cooler surfaces downstream, forming sticky deposits that capture other ash particles. These deposits can react with metal surfaces and protective oxide layers, leading to accelerated corrosion [3].

- Experimental Solutions:

- Fuel Blending: Blend herbaceous biomass with woody biomass, which has a lower alkali metal content, to dilute the concentration of corrosive elements in the fuel feed [1].

- Use Protective Materials: In critical areas, use reactors or sample probes constructed from corrosion-resistant alloys or apply protective coatings where feasible [25] [3].

- Control Combustion Temperature: Operate the combustor at temperatures below the melting point of the predominant ash-forming species to minimize the formation of sticky, adhesive slagging deposits.

Problem: Poor Fuel Conversion and Low Combustion Efficiency

- Observed Symptoms: High levels of unburned carbon in ash, pellets or half-burned fuel in the ash chamber, and low measured temperatures of exhaust gases [4].

- Underlying Mechanism: This can be caused by several factors, including insufficient air supply (especially under-fire/primary air), poor air-fuel mixing, low combustion temperatures, or a damaged grate system that allows fuel to fall through before complete burnout [4].

- Experimental Solutions:

- Inspect and Maintain the Grate: For grate-based systems, ensure the grate is intact and the gaps are not blocked or overly wide. A damaged grate can allow unburned fuel to fall into the ash pan [4].

- Verify Air Supply: Check that primary and secondary air fans are functioning correctly and that airflow pathways are not obstructed by ash buildup [4].

- Ensure Fuel Quality: Use fuel with consistent sizing and low moisture content. Oversized or wet fuel pieces can lead to uneven combustion and poor burnout [25].

Quantitative Data on Biomass Properties and Emissions

Table 1: Proximate and Emission Properties of Different Biomass Fuels

This table summarizes key characteristics of various biomass types, highlighting the differences that impact combustion behavior and emissions. Data is synthesized from experimental studies [1].

| Biomass Fuel Type | Calorific Value (MJ·kg⁻¹) | Ash Content (% w/w) | CO Emission Trend (vs. Wood) | NO Emission Trend (vs. Wood) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birch Sawdust (Woody) | 16.34 | Low (Baseline) | Baseline | Baseline |

| Wheat Straw | 16.29 | 2-4x Higher | Higher (Manual feed), Lower (Auto feed) | Higher |

| Rye Straw | 16.28 | 2-4x Higher | Higher (Manual feed), Lower (Auto feed) | Higher |

| Meadow Hay | 16.26 | 2-4x Higher | Higher (Manual feed), Lower (Auto feed) | Higher |

| Oat Straw | 15.47 | 2-4x Higher | Higher (Manual feed), Lower (Auto feed) | Higher |

Table 2: Impact of Fuel Feeding System on Combustion Efficiency and Emissions

This table compares the performance of periodic (e.g., grate) and automated (e.g., gutter burner) feeding systems, demonstrating how technology choice can alter combustion outcomes [1].

| Performance Parameter | Periodic Fuel Feeding (Grate) | Automated Fuel Feeding (Gutter Burner) |

|---|---|---|

| Process Stability | Less stable, fluctuating | More stable and balanced |

| Combustion Efficiency | Lower for herbaceous biomass | Increased for herbaceous biomass |

| CO Emissions | Higher, more variable | Significantly reduced and stabilized |

| NO Emissions | Lower | Increased (due to more stable, high-T conditions) |

| Suitability for Herbaceous Pellets | Poor | Good replacement for woody biofuels |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol: Determining Volatile Matter and Tar Content

Objective: To quantitatively assess the volatile matter and tar yield from a biomass sample under controlled pyrolysis conditions.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a representative sample of biomass feedstock, ground to a specified particle size (e.g., using a hammer shredder with a 10 mm sieve) [1]. Determine the initial moisture content using the dryer-weighing method per standard EN ISO 18134-3:2015 [1].

- Pyrolysis: Heat the dried sample (approximately 1g) in a cylindrical silica crucible to 900 ± 5 °C in a muffle furnace maintained in the absence of air [24]. Maintain this temperature for 7 minutes [24].

- Tar Aerosol Collection: The liberated volatile matter, which includes tars, should be transported by an inert gas (e.g., Nitrogen) into a cooling train or a series of filters (e.g., membrane filters) kept at low temperature to condense and collect the tar aerosol [24].

- Analysis: Weigh the collected tar. The volatile matter content is calculated as the percentage of mass loss from the original dry sample. The collected tar can be further analyzed using Field Ionization Mass Spectrometry (FIMS) to determine the proportion of volatile vs. non-volatile (heavy) tar components [24].

Protocol: Assessing Combustion Efficiency via Exhaust Gas Analysis

Objective: To calculate the Combustion Efficiency Index (CEI) and Toxicity Index (TI) during a biomass combustion experiment.

Methodology:

- Experimental Setup: Conduct combustion tests in a controlled reactor (e.g., a domestic grate-fired boiler or a lab-scale tube furnace) [1].

- Data Collection: During combustion, with simultaneous timing, continuously monitor the flue gas to measure the concentration of CO2, CO, NO, and SO2. Simultaneously, measure the temperature of the supplied air and the exhaust gases [1].

- Calculation:

- Stack Loss (qA): Calculate the heat loss through the stack based on the temperature and composition of the exhaust gases.

- Combustion Efficiency Index (CEI): This is derived from the energy input minus the stack loss (qA). A higher CEI indicates a more efficient combustion process [1].

- Toxicity Index (TI): Calculate as the ratio of CO to CO2 (CO/CO2) in the exhaust gas. This ratio indicates how clean the combustion process is, with a lower TI being more desirable [1].

Visualizing Combustion Challenges and Workflows

Biomass Combustion Challenge Pathway

Experimental Efficiency Analysis Workflow

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

This table lists essential materials and their functions for setting up and conducting biomass combustion experiments focused on the core challenges.

| Item Name | Function / Application in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Silica Crucible | Used for standard proximate analysis (volatile matter determination) at high temperatures (900°C+). | Inert, withstands repeated high-temperature heating without reacting with the sample [24]. |

| Membrane Filters | Collection of tar aerosols from the flue gas stream for mass yield calculation and subsequent chemical analysis (e.g., FIMS). | Pore size should be selected to capture fine aerosol particles; allows for visual inspection of tar swirls [24]. |

| Electrochemical Gas Sensors | Continuous monitoring of flue gas composition (CO, CO2, NO, SO2) for efficiency and emission calculations. | Require regular calibration; placement in the flue gas stream is critical for representative sampling [1]. |

| Corrosion-Resistant Alloy Probes | Construction of sample probes or reactor components exposed to high temperatures and corrosive flue gases. | Materials like stainless steel or Inconel resist degradation from alkali deposits and acidic gases, extending experimental apparatus life [25] [3]. |

| Leister Ignition Gun | Provides a reliable and controlled hot-air source for igniting biomass fuel in experimental burners. | Ensures consistent startup conditions across multiple experimental runs [4]. |

Advanced Methods for Monitoring and Controlling Combustion Parameters

This technical support center provides comprehensive guidance for researchers utilizing customized high-temperature flat flame furnace systems for real-time combustion analysis. These advanced systems are specifically designed to address critical gaps in biomass combustion research, enabling high-resolution monitoring of thermochemical conversion processes. The core innovation of this setup lies in its integration of a customized Hencken flat flame furnace with simultaneous thermogravimetric analysis and two-color photometry imaging. This powerful combination facilitates the capture of real-time combustion dynamics and time-resolved interactions between heat transfer, mass loss, and flame characteristics that conventional systems cannot detect [26].

For researchers focused on optimizing biomass residence time and combustion efficiency, this diagnostic approach provides unprecedented insights into fundamental combustion behaviors, including volatile ignition, char burnout, and flame temperature evolution under various temperature conditions. The system is particularly valuable for comparative analysis of raw and torrefied biomass pellets, allowing direct observation of how different pretreatment methods affect combustion performance at temperatures ranging from 1100°C to 1300°C [26].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Material Preparation and Torrefaction Protocol

Biomass Selection and Preparation:

- Material: Begin with lignocellulosic wood biomass (e.g., Pine Wood-PW)

- Processing: Grind and sieve the raw biomass to achieve a uniform particle size of 600μm

- Drying: Place samples in a dryer box at 105°C for 12 hours to remove residual moisture [26]

Torrefaction Pretreatment (Mild Pyrolysis):

- Equipment: Utilize a horizontal tube furnace (e.g., SK-G06125K)

- Atmosphere: Maintain an inert environment using nitrogen gas with a flow rate of 500 mL/min

- Temperature Parameters: Process samples at different temperature ranges (200°C, 250°C, 300°C) with residence times varying from 15 to 45 minutes

- Labeling Convention:

- PW: Raw biomass

- T-200°C: Torrefied at 200°C

- T-250°C: Torrefied at 250°C

- T-300°C: Torrefied at 300°C [26]

Pelletization Process:

- Equipment: Employ a hydraulic press with a customized mold

- Pressure: Apply 20 MPa of pressure for 3 minutes

- Binding Agent: Add 5-10% moisture as a binding agent to facilitate pellet formation

- Final Product: Produce cylindrical pellets with approximately 8mm diameter and 10mm height [26]

Flat Flame Furnace Operation Protocol

System Configuration:

- Furnace Type: Customized Hencken flat flame furnace

- Temperature Settings: Conduct experiments at 1100°C, 1200°C, and 1300°C to simulate various industrial conditions

- Sample Placement: Position individual pellets on a custom-designed sample holder introduced vertically into the furnace

- Combustion Atmosphere: Maintain consistent oxidizing conditions throughout experiments [26]

Real-Time Diagnostic Setup:

- Weight Loss Monitoring: Implement a customized system capable of tracking mass changes with high temporal resolution

- Two-Color Photometry: Deploy calibrated high-speed imaging to measure flame temperature and characteristics

- Synchronization: Ensure all diagnostic systems are temporally aligned to correlate mass loss with flame behavior [26]

Data Collection Parameters:

- Sampling Rate: Acquire weight loss data at minimum 10 Hz frequency

- Imaging Specifications: Capture flame images at high frame rates (minimum 100 fps)

- Experimental Duration: Continue each test until complete pellet combustion is achieved [26]

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Operational Issues and Solutions

Problem: Unstable Flame During Combustion Experiments

- Symptoms: Flame flickering, irregular flame shape, or incomplete combustion

- Potential Causes:

- Inconsistent fuel properties (moisture content, particle size)

- Improper combustion air distribution

- Fluctuations in furnace temperature

- Solutions:

- Ensure uniform pellet density and composition through standardized preparation

- Verify primary and secondary air supply systems for consistent flow

- Check furnace temperature controllers and heating elements

- Preheat combustion air to stabilize flame conditions [27]

Problem: Inconsistent Weight Loss Measurements

- Symptoms: Erratic mass readings, unexpected mass fluctuations, or signal dropout

- Potential Causes:

- Mechanical vibrations affecting the measurement system

- Thermal expansion of components at high temperatures

- Sample holder interference or contact issues

- Solutions:

- Implement vibration damping systems around the measurement apparatus

- Calibrate weight measurement at operational temperatures to account for thermal effects

- Ensure sample holder moves freely without contacting furnace walls

- Verify data acquisition system grounding and shielding [26]

Problem: Poor Reproducibility Between Experiments

- Symptoms: Significant variation in combustion characteristics between identical pellet types

- Potential Causes:

- Biomass feedstock variability

- Inconsistent torrefaction conditions

- Pellet density variations

- Solutions:

- Source biomass from consistent batches and storage conditions

- Monitor and control torrefaction parameters precisely (temperature, residence time, atmosphere)

- Implement quality control checks for pellet density and dimensions

- Use statistical analysis with adequate sample sizes (minimum n=5 per condition) [26]

Diagnostic System Performance Issues

Problem: Inaccurate Flame Temperature Measurements

- Symptoms: Temperature readings inconsistent with expected values, poor measurement repeatability

- Potential Causes:

- Improper calibration of two-color photometry system

- Particle interference in flame region

- Incorrect emissivity settings

- Solutions:

- Recalibrate two-color photometry using standard reference sources

- Ensure clean optical paths and lenses

- Verify appropriate emissivity values for biomass flame conditions

- Implement background subtraction for particle interference [26]

Problem: Data Synchronization Errors

- Symptoms: Time misalignment between weight loss and flame characteristics

- Potential Causes:

- Variable latency in different measurement systems

- Improper trigger configuration

- Data acquisition timing errors

- Solutions:

- Implement unified trigger system with precise timestamping

- Measure and compensate for system latencies

- Use common time reference across all instruments

- Verify synchronization with standardized test procedures [26]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key advantages of using a flat flame furnace compared to conventional thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) for biomass combustion studies?

Flat flame furnace systems provide several critical advantages over conventional TGA: (1) They enable high heating rates (up to 10⁴-10⁵ K/s) that more accurately simulate industrial combustion conditions; (2) They permit real-time observation of combustion dynamics including ignition delay, volatile flame duration, and char burnout; (3) They allow simultaneous measurement of mass loss and flame characteristics through integrated diagnostics; (4) They accommodate larger sample sizes that better represent bulk biomass behavior compared to milligram-scale TGA samples [26].

Q2: How does torrefaction temperature impact combustion performance in the flat flame furnace?

Torrefaction temperature significantly influences combustion characteristics. Research shows that increasing torrefaction temperature from 200°C to 300°C: (1) Reduces mass yield from approximately 75% to 45% while increasing energy density; (2) Shortens ignition delay by up to 30% due to increased thermal stability; (3) Decreases volatile combustion duration while prolonging char burnout phase; (4) Enhances combustion efficiency by improving fuel uniformity and reducing moisture content [26].

Q3: What flame characteristics indicate optimal combustion conditions in the flat flame furnace?

Optimal combustion is indicated by: (1) Stable blue flame during volatile combustion phase; (2) Consistent flame temperature profiles with minimal fluctuations; (3) Progressive char conversion without abrupt changes in combustion rate; (4) Minimal particle ejection or fragmentation during burning. Poor combustion is characterized by yellow tipping, flame flickering, or unstable combustion rates, which often indicate improper air-fuel mixing or fuel quality issues [28].

Q4: How can researchers minimize experimental variability when comparing different biomass feedstocks?

To minimize variability: (1) Standardize pellet preparation using consistent pressure, moisture content, and dimensions; (2) Control storage conditions to prevent moisture absorption before testing; (3) Implement replicate testing with sufficient sample size (minimum 3-5 repetitions per condition); (4) Randomize testing order to prevent systematic bias; (5) Include reference materials with known combustion characteristics in each experimental session [26].

Q5: What safety protocols are essential when operating high-temperature flat flame furnace systems?

Critical safety protocols include: (1) Proper ventilation to handle combustion products and potential gas releases; (2) High-temperature insulation and shielding to prevent accidental contact with hot surfaces; (3) Emergency shutdown procedures for power failure or system malfunctions; (4) Personal protective equipment including heat-resistant gloves, face shields, and lab coats; (5) Gas monitoring systems to detect leaks in the inert gas supply or combustion products [26].

Data Interpretation Guidelines

Combustion Characteristic Analysis

Table 1: Typical Combustion Parameters for Raw and Torrefied Biomass Pellets

| Parameter | Raw Biomass | Torrefied at 200°C | Torrefied at 250°C | Torrefied at 300°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ignition Delay (s) | 2.1-2.5 | 1.8-2.2 | 1.5-1.9 | 1.2-1.6 |

| Volatile Combustion Duration (s) | 4.5-5.5 | 4.0-4.8 | 3.5-4.2 | 3.0-3.7 |

| Char Burnout Time (s) | 8.5-10.5 | 9.0-11.0 | 9.5-11.5 | 10.0-12.5 |

| Peak Flame Temperature (°C) | 1250-1350 | 1300-1400 | 1350-1450 | 1400-1500 |

| Total Combustion Time (s) | 15-18 | 14-17 | 14-17 | 14-17 |

Data compiled from experimental results using pine wood pellets at 1200°C furnace temperature [26]

Diagnostic Measurement Standards

Table 2: Acceptable Ranges for Key Combustion Diagnostics

| Measurement Type | Acceptable Range | Optimal Performance Range | Calibration Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight Loss Resolution | ±0.1 mg | ±0.05 mg | Before each experiment series |

| Temperature Measurement Accuracy | ±25°C | ±10°C | Weekly with reference source |

| Time Synchronization Accuracy | ±100 ms | ±10 ms | Before each experiment |

| Image Capture Rate | 50-100 fps | 100-500 fps | Verify before each session |

| Data Sampling Rate | 5 Hz minimum | 10-50 Hz | Continuous monitoring |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Materials and Their Experimental Functions

| Material/Reagent | Function in Experiment | Specifications | Handling Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Primary fuel source for combustion studies | Uniform particle size (600μm), controlled moisture content (<10%) | Store in dry conditions to prevent moisture absorption |

| Nitrogen Gas | Create inert atmosphere for torrefaction | High purity (≥99.5%), controlled flow rate (500 mL/min) | Secure cylinders, check for leaks regularly |

| Calibration References | Validate temperature measurement systems | Certified melting point standards or blackbody references | Handle with clean gloves to prevent contamination |

| Binding Agent (Water) | Facilitate pellet formation during densification | Deionized water, controlled percentage (5-10%) | Measure precisely for consistent pellet quality |

| Standard Reference Materials | Quality control and inter-laboratory comparison | Certified biomass samples with known properties | Store according to supplier specifications |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Biomass Combustion Analysis Workflow

Diagram 2: Flat Flame Furnace Diagnostic System

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) for Modeling Temperature Fields and Flue Gas Dynamics

Troubleshooting Guides for Common CFD Challenges in Biomass Combustion

Frequent CFD Solution Divergence and Stability Issues

Problem: CFD simulation of the biomass combustion chamber aborts unexpectedly or produces unstable, diverging residuals.

- Possible Cause 1: Inappropriate mesh quality or resolution.

- Diagnosis: Check mesh metrics (orthogonal quality, skewness) in your pre-processor. Low orthogonal quality (below 0.1) or high skewness (above 0.95) can cause divergence.

- Solution: Refine the mesh, especially in critical regions like near inlets, the fuel bed, and heat exchanger tubes. Ensure the mesh has sufficient inflation layers near walls. A grid sensitivity test, as performed in one study that used 575,500 elements with an average orthogonal quality of 0.85, is recommended [29].

- Possible Cause 2: Overly aggressive under-relaxation factors for complex reactions.

- Diagnosis: Divergence occurs immediately after initialization or when combustion reactions begin.

- Solution: Reduce under-relaxation factors for species, energy, and momentum. Start with factors 20-30% lower than default settings. Gradually increase them as the solution stabilizes.

Inaccurate Prediction of Temperature and Species Profiles

Problem: Simulated temperature fields or species concentrations (O₂, CO, CO₂) do not match experimental data.

- Possible Cause 1: Incorrect boundary condition definition for the biomass fuel bed.

- Diagnosis: Compare the defined volatile release rate and composition to published data for your specific biomass type.

- Solution: Implement a realistic fuel bed model. Simplified approaches, such as dividing the fuel into water vapor, volatiles, and fixed char released from specific zones, have shown good agreement with experimental flue gas data [30]. Ensure the devolatilization model (e.g., single-step Arrhenius, Kobayashi's two-step model) and its kinetic parameters are appropriate for wood/biomass [31].

- Possible Cause 2: Faulty turbulence-chemistry interaction model.

- Diagnosis: Large discrepancies in CO emissions, indicating poor mixing prediction.

- Solution: The Eddy Dissipation Concept (EDC) model can be used for turbulent, non-premixed flames common in biomass boilers [29]. For strongly swirling flows, consider using the k-ω SST turbulence model instead of the standard k-ε model for better accuracy [29].

High Particulate Matter (PM) Emissions in Results

Problem: The model predicts acceptable gas-phase emissions but fails to capture the formation and trajectory of particulate matter (PM).

- Possible Cause: Inadequate modeling of particle transport and separation within the system.

- Diagnosis: Particle tracks show no interaction with baffles or collection surfaces.

- Solution: To study PM reduction, incorporate a Discrete Phase Model (DPM) to track particle trajectories. Model baffles or deflectors in the flue gas tract, as these have been shown to capture particles larger than 100 µm effectively by altering flow direction and creating settling zones [29]. The forces on particles (gravity, drag, electrostatic if applicable) must be correctly defined [32].

Poor Convergence in Species Transport Equations

Problem: The simulation runs but residuals for species equations (e.g., CO, CH₄) stall at a high value, preventing a converged solution.

- Possible Cause: Insufficient resolution of reaction zones and steep species gradients.

- Diagnosis: High residuals are localized in the combustion zone or near the secondary air inlets.

- Solution: Implement mesh adaptation based on species gradients in the combustion chamber and flue gas tract. This locally refines the grid in areas with high reaction rates, improving the accuracy of species and temperature predictions [29].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which turbulence model is most suitable for simulating flue gas flow in a biomass furnace? A: The choice depends on the flow characteristics. The k-ε realizable model is often a good starting point for its robustness and reasonable accuracy for many internal flows. However, for flows with strong swirl, separation, or stagnation points—common in combustion chambers—the k-ω Shear Stress Transport (SST) model is more accurate as it provides superior performance in predicting flow separation and behavior in near-wall regions [29].

Q2: How can I optimize the air supply system in my biomass boiler model to reduce CO emissions? A: Computational studies show that optimizing the secondary air distribution is key. This involves:

- Ensuring Uniform Air Distribution: A poorly designed air manifold can lead to uneven air velocity across outlets, causing incomplete mixing and high CO. CFD can be used to redesign the manifold (e.g., by bending the main duct) to achieve uniform flow [33].

- Strategic Nozzle Placement: Using more distribution pipes with smaller diameters and optimizing their location and angle can significantly improve the mixing of air with unburned gases, leading to more complete combustion and lower CO [33].

Q3: What is a practical way to model the solid biomass fuel bed in a grate boiler simulation? A: A common and practical approach is to treat the fixed bed as a porous zone and simplify the fuel conversion process. This involves:

- Dividing the biomass fuel into distinct components: water vapor, volatiles, and fixed char.

- Assigning the release of each component to separate zones on the grate. Volatiles and vapor can be modeled as being released from the log's outer layer, while char burnout occurs in the firebed [30].

- This method reduces computational cost while providing quite good agreement with experimental data for temperature and major flue gas species [30].

Q4: My model shows incorrect temperature peaks in the combustion chamber. What should I check? A: First, verify the radiation model. Surface-to-surface (S2S) or Discrete Ordinates (DO) models are critical for capturing heat transfer in combustion applications. Second, check the heating value and composition of the volatiles defined in your devolatilization model, as this is the primary energy source. Inaccurate values here will directly lead to wrong flame temperatures.

Q5: How can I use CFD to design a system that reduces particulate matter emissions? A: CFD can model the trajectory of particles in the flue gas. You can test the effectiveness of different baffle placements and geometries within the flue gas tract. Simulations have demonstrated that strategically placed baffles can force the flue gas to change direction, causing larger particles (e.g., >100 µm) to separate from the flow due to inertia and be captured [29]. Analyzing particle trajectories helps optimize the number, angle, and position of these baffles.

Essential Experimental Protocols and Data

Protocol for CFD Model Setup and Validation

This protocol outlines the key steps for establishing a reliable CFD model for biomass combustion systems, based on established methodologies [30] [29].

Geometry and Mesh Creation:

- Use parametric CAD software for geometry creation.

- Generate a computational mesh with sufficient density, particularly near walls and inlets. For small-scale boilers, mesh sizes can range from several hundred thousand to over a million elements [30].

- Perform a grid sensitivity test by comparing results (e.g., temperature, velocity) from a significantly denser mesh. Differences below ~3% typically indicate grid independence [29].

Model Selection:

- Turbulence: Choose between k-ε (e.g., realizable) or k-ω SST models based on flow characteristics.

- Combustion: Use a non-premixed combustion model or finite-rate/Eddy Dissipation model.

- Radiation: Activate the Discrete Ordinates (DO) or Surface-to-Surface (S2S) model.

- Discrete Phase: If modeling particles, enable the Discrete Phase Model (DPM).

Boundary Condition Definition:

- Inlets: Define primary, secondary, and (if applicable) tertiary air inlets with measured or calculated mass flow rates and turbulence parameters.

- Fuel Bed: Implement a simplified bed model, defining zones for volatile and char combustion with appropriate source terms [30].

- Walls: Set thermal boundary conditions (e.g., convective heat transfer) based on material properties and operating conditions [29].

- Outlet: Use a pressure outlet boundary condition, often with a slight negative gauge pressure (e.g., -12 Pa) to simulate chimney draft [29].

Solution and Validation:

- Start with a cold flow simulation before activating reactions.

- Compare steady-state results (flue gas temperature, O₂, CO, CO₂) against experimental measurements from the boiler or stove to validate the model [30].

Quantitative Data from CFD Studies

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from various CFD investigations relevant to biomass combustion optimization.

Table 1: Summary of Key Quantitative Findings from CFD Studies

| Aspect | Finding | CFD Tool / Method | Significance for Efficiency/Residence Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flue Gas Tract Baffles | Effective at capturing particles with diameter >100 µm [29]. | DPM, k-ω SST & k-ε models | Increases effective residence time for particles by trapping them, reducing PM emissions. |

| Secondary Air System | Optimizing manifold design to ensure uniform velocity across outlets improves mixing [33]. | Finite Volume Method, ANSYS Fluent | Enhances mixing of air and volatiles, leading to more complete combustion and higher efficiency. |

| Turbulence Model Choice | The k-ω SST model achieved significantly better results in swirling flows compared to the k-ε model [29]. | Model comparison | Accurate flow prediction is foundational for correct temperature and species field modeling. |

| Grid Sensitivity | A test with 6.7x denser mesh showed differences of ~2.4% in particle number, justifying a coarser mesh [29]. | Grid convergence study | Ensures results are not dependent on mesh resolution, saving computational time without sacrificing accuracy. |

Research Workflow and Pathways

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for using CFD to optimize biomass combustion systems, integrating troubleshooting and validation steps.

Diagram Title: CFD-Based Biomass Combustion Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential CFD Research Reagents

This table details the key "research reagents" – in this context, software tools and physical models – essential for conducting CFD studies on biomass combustion systems.

Table 2: Essential Tools and Models for Biomass Combustion CFD

| Tool / Model | Function | Application Example in Biomass Combustion |

|---|---|---|

| ANSYS Fluent | A commercial finite-volume based CFD solver. | Used for simulating the complex coupled phenomena of fluid flow, heat transfer, and chemical reactions in boilers and furnaces [30] [33] [31]. |

| Devolatilization Models | Sub-models that describe the thermal decomposition of solid biomass into gases and char. | Critical for accurately predicting the release of volatiles, which form the main flame. Models range from simple one-step to complex multi-step schemes (e.g., Kobayashi) [31]. |

| k-ω SST Turbulence Model | A two-equation turbulence model that provides accurate predictions of flow separation in adverse pressure gradients. | Recommended for simulating flows with strong swirl or separation, such as in the secondary combustion chamber of a wood log boiler [29]. |

| Discrete Phase Model (DPM) | A Lagrangian approach for tracking discrete particles (e.g., dust, droplets) through the flow field. | Used to model the trajectory and fate of particulate matter (PM) in flue gases, allowing for the evaluation of baffle and precipitator efficiency [29] [32]. |

| Eddy Dissipation Concept (EDC) | A turbulence-chemistry interaction model for non-premixed combustion. | Suitable for modeling the combustion of volatile gases in the turbulent flame zone of a biomass furnace [29]. |

Machine Learning (ML) Models for Predicting Syngas Yield and Optimizing Process Parameters

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most effective machine learning models for predicting syngas composition from biomass gasification?

Multiple ML models have been successfully applied. Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) often demonstrates superior performance, especially with smaller datasets, achieving R² values greater than 0.983 for predicting components like H₂, CO, CO₂, and CH₄ in plasma gasification systems [34]. Random Forest (RF) models also excel, particularly for predicting syngas composition and its Lower Heating Value (LHV), achieving R-squared values close to 1 [35]. The optimal model can depend on your dataset size and the specific output variable of interest.

FAQ 2: Which process parameters are most critical for optimizing syngas yield and composition?

Machine learning feature importance analyses reveal that the steam-to-biomass ratio (SBR) is a consistently critical parameter for enhancing hydrogen production in steam gasification [35]. Furthermore, temperature is a dominant factor, with one study attributing an importance value of 0.65 to it in a methanol synthesis prediction model, aligning with Arrhenius kinetics [36]. For chemical looping gasification, the oxygen-to-biomass ratio is a key control parameter, with values between 0.33 and 0.38 required for auto-thermal operation [37].

FAQ 3: How can I build a reliable ML model with a limited amount of experimental gasification data?

When large datasets are not available, Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) is highly recommended as it is specifically designed to provide robust predictions and uncertainty estimates from small datasets [38]. Employing validation techniques like leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) is also crucial for reliably estimating model performance when data is scarce [38].

FAQ 4: How does biomass residence time in the reactor impact conversion efficiency?

Biomass conversion is characterized by devolatilization and extinction times, which together define the biomass residence time. This residence time increases with a decreasing air flowrate and increasing biomass load [8]. A longer residence time can lead to a higher accumulation of unconverted char, thereby affecting the overall conversion efficiency and heat loss [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Model Performance and Generalization

Problem: Your ML model shows high accuracy on training data but performs poorly on unseen test data (overfitting).

Solution:

- Action 1: Implement Cross-Validation. Use k-fold cross-validation during model training to ensure your model generalizes well. This technique provides a more realistic performance estimate by repeatedly training and validating the model on different data subsets [34] [35].

- Action 2: Apply Regularization. For regression models, use regularized methods like Lasso regression (L1 regularization), which penalizes model complexity and can perform feature selection by forcing less important coefficients to zero [35].

- Action 3: Leverage Models for Small Datasets. If your dataset is small, switch to algorithms like Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), which provides uncertainty estimates and is less prone to overfitting with limited data [38].

Uninterpretable "Black-Box" Model Predictions

Problem: The ML model's predictions are accurate but not interpretable, making it difficult to gain scientific insights or trust the results.

Solution:

- Action 1: Perform SHAP Analysis. Use SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), a model-agnostic method, to quantify the contribution of each input feature (e.g., temperature, SBR) to a specific prediction. This identifies the most influential process parameters [35].

- Action 2: Choose Interpretable Models. When possible, use models that offer inherent interpretability, such as Decision Trees or Random Forests, which can provide feature importance scores [34] [35].

Suboptimal Syngas Yield and Hydrogen Concentration

Problem: Experimental results show lower-than-expected syngas yield, particularly hydrogen content.

Solution:

- Action 1: Optimize the Steam-to-Biomass Ratio. SHAP analysis has identified SBR as the most critical factor for hydrogen yield. Systematically adjust this ratio within your reactor's operational limits [35].

- Action 2: Control the Oxygen Flow. In chemical looping gasification (BCLG), maximize syngas yield by controlling the oxygen flow fed to the air reactor. Maintaining an oxygen-to-biomass ratio between 0.33 and 0.38 is crucial for achieving auto-thermal operation and high cold gas efficiency (79.8–86.2%) [37].

- Action 3: Ensure Proper Residence Time. Monitor and optimize biomass residence time. Increasing biomass load or decreasing air flowrate can increase residence time, but be aware this may also increase char accumulation [8].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Developing an ML Model for Syngas Composition Prediction

This protocol outlines the workflow for creating a machine learning model to predict syngas outcomes from experimental data.

1. Data Collection and Pre-processing:

- Input Features: Collect data on biomass properties (ultimate and proximate analysis) and operating parameters (temperature, pressure, steam-to-biomass ratio, air flowrate, etc.) [35] [38].

- Output Targets: Obtain measured values for syngas components (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, N₂, O₂) and other relevant outputs like gas yield or Lower Heating Value (LHV) [38].

- Data Cleansing: Address missing data, normalize features, and reduce correlated features to improve model stability and performance [34].

2. Model Selection and Training:

- Algorithm Choice: Select appropriate algorithms. Common high-performers include Random Forest (RF), Gaussian Process Regression (GPR), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Decision Tree Regression (DTR) [34] [35].