Managing Seasonal Biomass Feedstock Variability: Strategies for Stable Supply Chains in Bioenergy and Bioproducts

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the challenges and solutions associated with the seasonal availability of biomass feedstocks, a critical issue for researchers and professionals in bioenergy and bioproduct...

Managing Seasonal Biomass Feedstock Variability: Strategies for Stable Supply Chains in Bioenergy and Bioproducts

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the challenges and solutions associated with the seasonal availability of biomass feedstocks, a critical issue for researchers and professionals in bioenergy and bioproduct development. It explores the foundational impact of seasonal variability on biomass yield and quality, presents methodological frameworks for supply chain optimization, details troubleshooting and optimization strategies for operational challenges, and offers validation through case studies and comparative analyses of regional approaches. The content synthesizes current research and technological advances to guide the development of resilient, year-round biomass supply systems capable of supporting continuous biorefinery operations and meeting decarbonization goals.

Understanding Seasonal Biomass Variability: Impacts on Yield, Quality, and Supply Chain Stability

FAQs: Managing Seasonal Biomass Variability in Research

FAQ 1: How significantly can seasonality impact biomass yield and biochemical composition? Seasonality causes substantial variation in both the quantity and quality of biomass. Research on macroalgal species in the Red Sea showed that primary and secondary metabolites, including total sugars, amino acids, fatty acids, and phenolic contents, were consistently higher in samples collected during the summer [1]. A study on dairy slurry in pasture-based systems found that seasonal availability alone can lead to a 21% reduction in total annual biomethane production compared to a constant supply [2]. Furthermore, inter-annual yield variability for agricultural residues like corn stover can be severe, with one study noting that a major drought year in the U.S. caused an average 27% yield reduction [3].

Table 1: Impact of Season on Biochemical Composition of Dominant Macroalgae (Summer vs. Winter) [1]

| Biochemical Component | Impact of Season | Notable Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Total Sugars | Higher in summer | Varies by species; influences bio-conversion potential. |

| Amino Acids | Higher in summer | Affects nutritional value and protein-derived product yields. |

| Fatty Acids | Higher in summer | Impacts lipid-based product synthesis and fuel quality. |

| Phenolic Contents | Higher in summer | Influences antioxidant activity and may act as process inhibitors. |

| Minerals | Varies by species | Higher in winter for some species (C. prolifera, A. spicifera, T. ornata), higher in summer for others (C. myrica, C. trinodis). |

FAQ 2: What are the primary causes of biomass quality degradation during storage? The primary risk during storage is uncontrolled microbial activity, which leads to dry matter loss (DML) and detrimental changes in chemical composition [4].

- Aerobic Degradation: In the presence of oxygen, microbes consume the biomass, directly reducing its mass and potentially generating heat that poses a fire risk for dry feedstocks [4].

- Moisture Content: High moisture levels are directly correlated with increased DML. One study on corn stover found that the rate and extent of degradation increased significantly above 36% moisture (wet basis) [4].

- Biochemical Changes: Storage can induce structural changes to the plant cell wall and cause the degradation of valuable components like hemicellulose, increasing the material's recalcitrance and lowering subsequent conversion yields [4].

FAQ 3: How does spatial and temporal variability affect long-term biorefinery operations? Optimizing a supply chain based on a single year's data can lead to non-robust and costly operations. Research using 10 years of drought index data shows that ignoring multi-year yield and quality variation can lead to a significant underestimation of biomass delivery costs [3]. Years with extreme drought not only reduce yield but also result in lower carbohydrate content and higher ash content, which directly lowers biofuel conversion efficiency and increases operational costs due to downtime and equipment wear [3]. A resilient supply chain design must account for this long-term variability to ensure consistent feedstock quality and stable operating costs.

Table 2: Key Challenges in Biomass Supply Chains Caused by Seasonality and Variability [5] [3] [6]

| Challenge Category | Specific Operational Hurdles |

|---|---|

| Supply & Logistics | Seasonal variability leads to fluctuating supplies; bulky, low-energy-density biomass is costly to transport and store [5] [6]. |

| Quality Control | Biomass chemical composition (e.g., carbohydrate, ash content) varies with climate stressors, impacting conversion process stability and final product yields [3]. |

| Economic Viability | High feedstock acquisition and transportation costs, coupled with the need for significant capital investment in storage and pre-processing infrastructure, threaten profitability [5] [6]. |

| Environmental Impact | Seasonal feedstock availability can increase the greenhouse gas footprint of the final bio-product. For instance, seasonal slurry availability increased GHG emissions by ~11 g CO₂-eq per megajoule of biomethane produced [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Biomass Quality Affecting Experimental Reproducibility

- Potential Cause 1: Harvesting biomass at different seasonal time points without accounting for natural biochemical shifts.

- Solution: Establish a standardized harvesting calendar based on phenological stages rather than calendar dates. For each research project, determine the target metabolites or components and align harvesting with their peak abundance (e.g., summer for higher sugars and phenolics in macroalgae) [1].

- Potential Cause 2: Inadequate pre-storage processing leading to uncontrolled degradation.

- Potential Cause 3: Lack of a quality monitoring protocol for incoming feedstock.

- Solution: Develop a rapid assessment protocol for key quality parameters (e.g., Near-Infrared Spectroscopy for moisture and carbohydrate content) to screen batches before they enter the experimental workflow and log this metadata rigorously [3].

Problem: High Dry Matter Loss During Long-Term Storage

- Potential Cause 1: Aerobic storage of high-moisture biomass.

- Solution: Utilize anaerobic storage (ensiling) for high-moisture feedstocks. This method preserves dry matter and can lead to minor pre-processing of the biomass that may reduce recalcitrance [4].

- Potential Cause 2: Insufficient densification leading to low energy density and high degradation risk.

- Solution: Convert biomass into agropellets or briquettes. This increases bulk and energy density, reduces transportation costs, inhibits biodegradation, and simplifies long-term storage [5].

- Potential Cause 3: Blending of different biomass feedstocks can improve silage stability.

- Solution: For novel or difficult-to-preserve feedstocks, blend them with more easily ensiled materials (e.g., blending flower strips with corn stover). This can improve the overall silage quality and stability [4].

Experimental Protocols for Seasonal Variability Research

Protocol 1: Assessing Seasonal Impact on Biomass Biochemistry

This protocol outlines a methodology for quantifying seasonal changes in biomass composition, based on approaches used in macroalgal and agricultural residue studies [1] [3].

- Site Selection & Sampling: Identify representative biomass collection sites. During sampling, record key environmental data such as temperature, precipitation, and drought indices [3] [1].

- Sample Collection: Collect biomass samples at predetermined phenological stages (e.g., pre-flowering, maturity, post-senescence) across multiple seasons and years. Use quadrat techniques for field samples and ensure biological replicates [1].

- Morphological & Molecular Identification: For wild-sourced biomass, identify species using both morphological characteristics and molecular markers (e.g., 18s rRNA) for accurate and reproducible taxonomy [1].

- Biochemical Characterization:

- Primary Metabolites: Analyze for total sugars (via HPLC or GC-MS), amino acid profile (via amino acid analyzer), and fatty acid profile (via GC-MS) [1].

- Secondary Metabolites: Quantify total phenolic content (e.g., using the Folin-Ciocalteu method) [1].

- Mineral Content: Determine ash content and specific mineral profiles using techniques like Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) [1].

- Data Analysis: Statistically analyze the data to correlate seasonal parameters with biochemical composition changes. Multivariate analysis can identify the most significant seasonal factors.

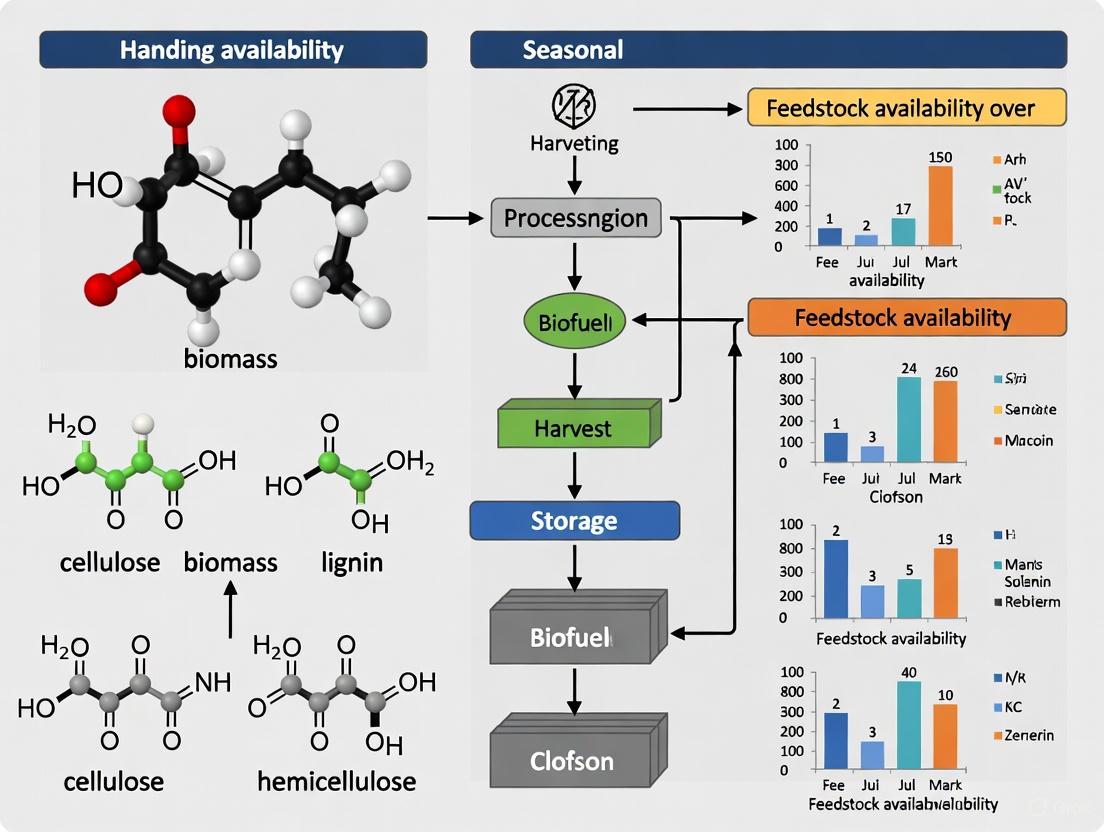

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol 2: Evaluating Storage Methods to Mitigate Seasonal Supply Issues

This protocol tests different storage strategies to preserve biomass quantity and quality for year-round experimental use, based on storage research for bioenergy crops [4].

- Feedstock Preparation: Harvest biomass at a consistent maturity. Split the biomass into representative batches for different storage treatments. Record initial moisture content, mass, and perform initial quality analysis.

- Storage Treatment Application:

- Treatment A (Aerobic): Store biomass in a loose or baled form, exposed to air. Monitor pile temperature.

- Treatment B (Anaerobic - Ensiling): Chop biomass and compact it in airtight containers (e.g., silos, plastic bags), potentially with additives.

- Treatment C (Pre-conditioned): Apply a pre-treatment like drying to <20% moisture, hot water extraction, or pelletization before aerobic storage [4].

- Storage Monitoring: Over the storage period (e.g., 30, 90, 180 days), monitor temperature and gas composition (if applicable). Use sensors placed at different depths in the storage pile.

- Post-Storage Analysis: At the end of each period, determine:

- Dry Matter Loss (DML): Calculate the percentage of dry mass lost.

- Biochemical Composition: Repeat the same biochemical analyses from Protocol 1 on the stored material.

- Conversion Efficiency: If applicable, perform a standard conversion assay (e.g., enzymatic hydrolysis for sugars, biomethane potential test) to assess functional quality [4].

- Statistical Evaluation: Compare DML, compositional changes, and conversion efficiency across storage treatments and durations to identify the optimal method.

The logical relationship of storage variables and outcomes is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Biomass Seasonality Research

| Item | Function & Application in Research |

|---|---|

| GC-MS / HPLC Systems | Essential for precise quantification of primary metabolites (sugars, fatty acids, organic acids) and secondary metabolites, enabling the tracking of compositional changes across seasons and storage. |

| ICP-OES / ICP-MS | Used for determining the mineral content and inorganic elemental profile of biomass, which can fluctuate with season and soil conditions [1]. |

| Molecular Biology Kits (DNA/RNA) | For accurate species identification of biomass feedstocks using genetic markers (e.g., 18s rRNA), ensuring taxonomic consistency in long-term studies [1]. |

| Anaerobic Storage Equipment | Includes airtight silos, plastic bags, and oxygen scavengers. Critical for conducting ensiling experiments to preserve biomass quality and study anaerobic storage effects [4]. |

| Portable Moisture Meter & Data Loggers | For rapid, in-field measurement of biomass moisture content (a key degradation factor) and for continuous monitoring of temperature and humidity in storage piles [4]. |

| Standardized Enzyme Assays | Pre-defined kits (e.g., for quantifying cellulase/hemicellulase activity) to assess the recalcitrance and biochemical conversion potential of biomass samples after different seasonal harvests or storage treatments [4]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequent Operational Disruptions

FAQ: What are common operational problems in biogas plants and how can they be resolved?

Operational disruptions in anaerobic digestion (AD) systems can significantly reduce biomethane yield. The table below summarizes frequent issues, their causes, and proven remedies [7].

| Problem | Primary Causes | Recommended Remedies |

|---|---|---|

| Scum Formation | Accumulation of floating solids and froth on digester liquid surface. [7] | Physically remove scum layer by scooping (floating drum) or using a water suction pump (fixed dome). Re-inoculate digester post-removal. [7] |

| Low Gas Production & Quality | Insufficient daily feeding depletes microorganisms. [7] | Ensure consistent daily feeding per design specifications. Maintain proper Carbon to Nitrogen (C/N) ratio in feedstock (ideal range: 20-30; optimum: 25). [7] |

| Ammonia Toxicity | High nitrogen content in feed (e.g., chicken manure) leads to ammonia accumulation. [7] | Keep ammonia content below 2000 ppm. Reduce organic loading rate if concentration rises. A well-adapted mesophilic digester can tolerate over 3000 ppm. [7] |

| Foam Production | Improper mixing, temperature variations, or inconsistent feedstock supply. [7] | Ensure consistent mixing, maintain stable temperature, and provide a uniform feedstock supply. Inspect and repair mixers or pumps as needed. [7] |

| Digester Temperature Fluctuations | Malfunctions in heating system or PLC controller. [7] | For mesophilic systems, maintain 35–37°C (95–98°F) with variation not exceeding ±0.6°C. Inspect heating system and PLC program. [7] |

| Struvite Deposits | Magnesium ammonium phosphate compound clogs pipes, valves, and heat exchangers. [7] | Use ferric chloride or ferrous chloride in digesters to prevent formation. Adjust pH or ratio of magnesium, ammonia, and phosphate to 1:1:1. [7] |

FAQ: What critical process parameters must be monitored to prevent system failure?

Maintaining a stable process requires vigilant monitoring of key parameters [7]:

- Volatile Fatty Acids (VFAs): Concentrations should remain below 2000 ppm. Levels exceeding 300 ml/L can cause digester overloading and failure.

- Heavy Metals: While trace amounts are beneficial, soluble concentrations should be kept below 0.5 mg/L to avoid toxicity.

- Salt (Sodium): Maintain sodium concentration between 3500 to 5500 ppm to prevent inhibition.

Case Study: Quantifying the Impact of Seasonal Biomass Availability

FAQ: What is the measurable impact of seasonal feedstock variation on biomethane production?

A study analyzing a pasture-based dairy system (100 cows, 10 ha of grass) quantified the severe impact of seasonal slurry availability, as summarized below [2].

| Performance Metric | Steady (Non-Seasonal) Feedstock Supply | Seasonal Feedstock Availability | Impact of Seasonality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Biomethane Production | Baseline (100%) | Reduced by 21% [2] | Significant annual energy loss |

| Digestate Recirculation Volume | Baseline level | Increased to over 12x the baseline requirement [2] | Higher operational energy/cost |

| Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions Intensity | Baseline | Increased by approx. 11 g CO₂-eq per MJ of biomethane [2] | Reduced environmental benefit |

| Digester Sizing & Operation | Stable organic loading rate | Smaller digester possible, but highly variable organic loading rate [2] | Complex operation and design |

Experimental Protocol for Quantifying Seasonal Impact:

Objective: To model and measure the reduction in biomethane production and operational parameters due to seasonal biomass availability.

Methodology [2]:

- System Definition: Define the farm system (e.g., 100 dairy cows, 10 ha dedicated grass).

- Scenario Modeling: Use Linear Programming (LP) optimization models to simulate two scenarios:

- Scenario A (Constant): Steady, year-round slurry and biomass availability.

- Scenario B (Seasonal): Seasonal slurry availability reflecting pasture-based farming.

- Parameter Calculation: For each scenario, the model calculates:

- Total annual biomethane production (MJ).

- Required digestate recirculation rates (m³/day).

- Digester sizing and organic loading rate profiles.

- Lifecycle GHG emissions (g CO₂-eq/MJ).

- Impact Quantification: Compare the results of Scenario B against Scenario A to determine the percentage or absolute reduction in gas yield and other key metrics.

This case study demonstrates that managing seasonality requires strategic operational adjustments, primarily optimized digestate recirculation, to mitigate its negative effects [2].

Workflow: Impact of Seasonal Feedstock

Case Study: Operational Disruption from a Lightning Strike

FAQ: Can external events cause major operational disruptions and how?

In October 2023, a lightning strike caused a major explosion and fire at the Severn Trent Green Power AD plant in Cassington, Oxfordshire [8]. The incident halted all plant operations.

- Cause: The lightning strike ignited biogas trapped under the gas collection domes [8].

- Impact: The explosion created a massive fireball, caused widespread power outages in local communities, and required a prolonged emergency response and site shutdown [8].

- Protocol for Safety: The incident highlights the critical need for robust safety measures, including [8]:

- Lightning Protection Systems: Installation of lightning rods to safely divert strikes to the ground.

- Regulatory Compliance: Strict adherence to explosion-risk regulations (e.g., ATEX, DSEAR in the UK).

- Comprehensive Risk Assessment (RA): Formal RA and procedures to manage identified risks.

Workflow: Operational Disruption Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

For researchers designing experiments to analyze biomethane reduction and process stability, the following tools and materials are essential.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Programmable Logic Controller (PLC) | Automates and monitors digester temperature and other critical process parameters to maintain optimal microbial activity. [7] |

| Volatile Fatty Acids (VFA) Analysis Kit | Measures VFA concentration (target <2000 ppm) to diagnose the health and stability of the anaerobic digestion process. [7] |

| Ammonia/Nitrogen Probe | Monitors ammonia levels to prevent toxicity (keep below 2000 ppm), especially when using nitrogen-rich feedstocks. [7] |

| Heavy Metal Test Kit | Ensures soluble heavy metal concentrations remain below the toxic threshold of 0.5 mg/L for the microbial community. [7] |

| Linear Programming (LP) Optimization Model | A computational tool used to determine the ideal substrate mixture that maximizes profitability and meets sustainability goals under varying market and feedstock constraints. [9] |

| Anaerobic Digestion Screening Tool (ADST) | An EPA-developed spreadsheet tool to estimate projected methane emissions reductions, biogas production, and economic feasibility for a given farm or facility. [10] |

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Variability

Protocol 1: Assessing Long-Term Yield Variability Using Drought Indices

Objective: To quantify the impact of climatic extremes, particularly drought, on the interannual yield and quality variability of biomass feedstocks.

- Data Collection: Utilize long-term (e.g., 10-year) datasets of county-level Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI) obtained from sources like the U.S. Drought Monitor. Calculate cumulative drought indices over growing degree days [3].

- Biomass Sampling: Collect biomass samples (e.g., corn stover) from multiple locations and years correlating with the drought index data. Key counties in agricultural regions like Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado can serve as model systems [3].

- Quality Analysis: Analyze the chemical composition of biomass samples, focusing on critical quality parameters such as carbohydrate content (glucan, xylan), ash content, and lignin levels using standard laboratory methods (e.g., NREL protocols) [3].

- Statistical Correlation: Perform regression analyses to correlate DSCI values with observed biomass yield and quality metrics (e.g., carbohydrate content) to model and predict variability [3].

Protocol 2: Spatially Explicit Economic Analysis of Land Use Change

Objective: To evaluate the economic viability of transitioning land to biomass feedstock production under climate uncertainty, moving beyond simple Net Present Value (NPV) calculations.

- Framework Selection: Employ a spatially explicit Real Options Analysis (ROA) model. This method incorporates investment irreversibility, price uncertainty, and flexibility in the timing of investment, which are often overlooked in NPV analysis [11] [12].

- Input Data:

- Spatial Data: Integrate high-resolution data on soil characteristics, historical rainfall, and temperature across the study region [11].

- Productivity Modeling: Use biophysical crop models (e.g., APSIM) to simulate agricultural and biomass productivity under baseline and future climate scenarios (e.g., warmer and drier conditions) [11].

- Economic Data: Collect data on establishment costs, commodity prices, and forecasted biomass prices [11].

- Model Simulation: Run the ROA model to calculate conversion thresholds—the level of revenue required to trigger land use change to biomass production. Map these thresholds across the landscape to identify economically viable areas under different climate and price scenarios [11] [12].

Protocol 3: Adaptive Management of Crop Growing Periods

Objective: To simulate and quantify the yield benefits of adapting sowing dates and cultivar choices to future climate conditions.

- Model Setup: Use a process-based global gridded crop model (e.g., LPJmL) driven by multiple General Circulation Models (GCMs) to project yields from a historical period (e.g., 1986-2005) to the end of the century (e.g., 2080-2099) [13].

- Management Scenarios: Define counterfactual management scenarios:

- No Adaptation: Fixed historical sowing dates and cultivars.

- Timely Adaptation: Sowing dates and cultivars are optimally adjusted to future climate for each 20-year period.

- Delayed Adaptation: Adaptation occurs with a 20-year delay [13].

- Crop Calendar Adaptation: Implement rule-based methods to simulate farmers' adaptive decisions on sowing and maturity dates based on agro-climatic principles (e.g., temperature for latitudes >30°N-S, precipitation seasonality for latitudes <30°N-S) [13].

- Cultivar Adaptation: For adapted scenarios, compute new thermal unit requirements (TUreq, °C day) for cultivars based on the simulated adapted sowing-to-maturity periods [13].

- Yield Comparison: Compare crop yields at the end of the century between the adaptation scenarios to quantify the potential yield increase from adaptive management [13].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our NPV analysis shows biomass production is profitable, yet we observe investment inertia among landowners. Why is this? Traditional NPV analysis often fails to account for sunk costs, investment irreversibility, uncertainty over future returns, and the value of flexibility in the timing of investment. A Real Options Analysis (ROA) framework demonstrates that the revenues required to trigger land use change must compensate for not only the establishment costs and foregone agricultural returns but also for the lost management flexibility and revenue uncertainty from the new biomass enterprise. This results in a higher investment threshold than NPV suggests [11].

Q2: How can we accurately model future biomass supply with climate change? Merely using historical average yields is insufficient. It is critical to incorporate spatial and temporal variability of both biomass yield and quality driven by climate factors. This involves:

- Long-Term Climate Data: Using multi-year time series (e.g., 10+ years) of climate data, including drought indices, to capture variability and extreme events [3].

- Spatially Explicit Modeling: Accounting for landscape heterogeneity in soil, rainfall, and temperature, which significantly affects the location and timing of viable biomass production [11].

- Adaptive Management: Modeling adaptive strategies such as shifts in sowing dates and use of later-maturing cultivars, which can significantly offset yield losses and harness potential benefits from CO₂ fertilization [13].

Q3: What is the primary cause of biomass quality variability, and how does it impact a biorefinery? Drought stress is a major driver of quality variability. Water deficit can alter the plant's biochemical pathways, leading to:

- Increased extractives (e.g., soluble sugars).

- Reduced structural carbohydrates (e.g., glucan, xylan), which are critical for biofuel conversion yields.

- Potential changes in lignin content and structure, affecting recalcitrance [3]. This variability directly impacts the maximum theoretical product yield (e.g., ethanol) and can increase operational costs due to equipment downtime, the need for more robust pre-processing, and handling of inconsistent feedstock [3].

Q4: Are there fundamental differences in how different forest types allocate biomass? Yes. Studies across China's forests show that coniferous forests have a significantly higher belowground biomass proportion (BGBP) compared to broadleaved forests. This indicates different resource allocation strategies. Furthermore, the primary drivers differ:

- Broadleaved Forests: Biomass allocation is influenced mainly by precipitation and soil nutrients.

- Coniferous Forests: Allocation is more strongly driven by temperature and soil composition [14]. In both types, climatic factors influence biomass partitioning by altering soil nutrients, particularly soil pH [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

Table 1: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biomass Variability Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| U.S. Drought Monitor DSCI Data | A standardized index to quantify and track drought severity and spatial coverage over time, used for correlating climate stress with biomass yield and quality [3]. |

| Real Options Analysis (ROA) Model | An advanced economic modeling framework that incorporates uncertainty, irreversibility, and the value of flexibility to more accurately assess the economics of land use change for biomass feedstocks [11] [12]. |

| Process-Based Crop Model (e.g., LPJmL, APSIM) | A biophysical simulation model used to predict crop growth, yield, and phenology under various management practices and climate scenarios [11] [13]. |

| Standardized Biomass Compositional Analysis Methods (e.g., NREL LAPs) | Laboratory analytical procedures for quantitatively determining the structural carbohydrate, ash, and lignin content of biomass feedstocks, essential for assessing quality variability [3]. |

Quantitative Data on Biomass Variability

Table 2: Documented Impacts of Climate Variability on Biomass Yield and Quality

| Parameter | Observed Change / Variability | Context / Cause | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn Stover Yield | Up to 48% reduction | Meta-analysis of drought and heat stress effects. | [3] |

| Corn Stover Carbohydrate Content | Highly variable, with lowest levels in high-drought years (e.g., 2012, 2013) | Correlation with high Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI). | [3] |

| Crop Yields (Maize, Rice, Sorghum, Soybean, Wheat) | ~12% potential increase | Global modeling study showing benefit of timely adaptation of sowing dates and cultivars to climate change. | [13] |

| Belowground Biomass Proportion (BGBP) | Significant decrease with increase in Mean Annual Temperature (MAT) and Mean Annual Precipitation (MAP) | Spatial analysis of 925 forest sites across China. | [14] |

Workflow Diagrams

Biomass Variability Assessment Workflow

Biomass Variability Assessment Workflow

Land Use Change Decision Framework

Land Use Change Decision Framework

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Biomass Research. This resource is designed for researchers and scientists grappling with the challenges of seasonal variability in biomass feedstocks. While availability is a well-known issue, this guide focuses on a more subtle but critical factor: seasonal fluctuations in biomass quality. These variations in chemical composition, driven by taxonomic shifts and environmental conditions, can significantly impact the efficiency and yield of downstream processes like anaerobic digestion and biofuel production. The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides provide targeted, evidence-based support for your experimental work.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How significant can seasonal variation in biomethane yield really be?

Seasonal variation is not just significant; it can be dramatic. The biochemical composition of biomass changes throughout the year, directly influencing its conversion efficiency.

- Evidence from Marine Biomass: A case study on phytoplankton biomass in the Bay of Gdansk found that the highest methane yield (270 ± 13 mL CH₄/g VS) was recorded in August, a period dominated by cyanobacteria with high contents of lipids and sugars. In contrast, the lowest biomethanation efficiency was observed in October when diatoms prevailed [15].

- Evidence from Agricultural Systems: Research on pasture-based dairy farming systems shows that the seasonal availability of slurry alone can lead to a 21% reduction in total biomethane production compared to constant year-round availability. This seasonality can also increase the greenhouse gas emissions intensity of the produced biomethane by approximately 11 g CO₂-eq MJ⁻¹ [2].

FAQ 2: Beyond yield, what specific biomass quality parameters change seasonally?

The chemical composition of biomass is highly dynamic. Key parameters that fluctuate include:

- Structural Components: The ratios of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin can vary [3].

- Elemental Composition: The Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C/N) ratio is a critical parameter for anaerobic digestion that changes with the season [15].

- Macronutrient Content: The content of lipids, proteins, and sugars in microalgal biomass has been shown to peak during different seasons, directly influencing methane production rates [15].

- Presence of Inhibitors: Drought stress, for example, can lead to the accumulation of compounds in some biomass feedstocks that may inhibit fermentation processes [3].

FAQ 3: What are the primary causes of seasonal biomass quality variability?

The fluctuations are driven by a combination of biological and environmental factors:

- Taxonomic Shifts: In algal communities, the dominant species change from green algae and dinoflagellates in spring, to cyanobacteria in summer, and diatoms in autumn. Each group has a distinct biochemical profile [15].

- Environmental Stressors: Climate factors, particularly drought and heat stress, significantly affect plant composition. Drought can reduce structural carbohydrates (e.g., glucan, xylan) and increase the concentration of soluble sugars and other extractives [3].

- Life Cycle and Maturity: The natural growth and senescence cycle of plants affects their composition, such as the lignin content and nutrient availability [16].

FAQ 4: How can I design a resilient supply chain that accounts for quality variability?

Designing for quality is as important as designing for quantity. Resilient strategies include:

- Multi-Sourcing: Sourcing biomass from multiple, geographically dispersed regions can help smooth out local variations in quality caused by weather events like drought [17].

- Blending Feedstocks: Strategically blending different biomass feedstocks can create a more consistent average composition, mitigating the poor quality of a single source [5].

- Advanced Planning: Use long-term (e.g., 10-year) data on yield and quality variability, correlated with factors like the drought index, to optimize supply chain strategy and avoid cost underestimation [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent Methane Yield from Anaerobic Digestion of Seasonal Biomass

Symptoms: Biogas production volumes and methane content fluctuate unpredictably despite a constant organic loading rate. You may observe periods of digester instability or even process inhibition.

Investigation & Solutions:

| Investigation Step | Methodology & Target | Interpretation & Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Characterize Feedstock | Chemical Analysis: Perform proximate analysis (TS, VS), elemental analysis (C, N), and biochemical analysis (lipid, protein, carbohydrate content) on each new batch of biomass [15]. | A low C/N ratio (<20) may indicate potential ammonia inhibition. High lignin content suggests slower hydrolysis. Adjust co-substrates to balance C/N or consider pretreatment. |

| 2. Monitor Digestion Kinetics | Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Tests: Conduct periodic batch assays to determine the ultimate methane yield and production rate of incoming feedstock [15]. | A lower-than-baseline BMP indicates poor feedstock quality. Use this data to adjust feedstock mixing ratios or digester retention time. |

| 3. Check for Inhibitors | Specific Compound Analysis: Test for common inhibitors like ammonia, sulfides, or specific salts. For drought-stressed biomass, target compounds like fermentation inhibitors [3]. | If inhibitors are identified, consider diluting the feedstock, increasing the inoculum-to-substrate ratio, or implementing a pre-treatment step. |

Problem: High Variability in Biofuel Conversion Efficiency from Lignocellulosic Biomass

Symptoms: Theoretical ethanol yield or sugar conversion efficiency varies significantly between batches of feedstock, leading to unpredictable biorefinery output and operational costs.

Investigation & Solutions:

| Investigation Step | Methodology & Target | Interpretation & Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Analyze Carbohydrate Profile | Compositional Analysis: Quantify the concentrations of glucan (cellulose), xylan (hemicellulose), and lignin using standard laboratory protocols (e.g., NREL methods) [3]. | A drop in glucan and xylan content directly reduces the maximum theoretical biofuel yield. A high ash content can increase equipment wear. Blend with higher-quality feedstock to meet a target composition. |

| 2. Assess Recalcitrance | Enzymatic Hydrolysis Assay: Subject a standardized sample of the biomass to enzymatic hydrolysis and measure the sugar release over time [3]. | Increased recalcitrance (lower sugar yield) requires more aggressive pre-treatment. Note that some drought-stressed biomass may actually show lower recalcitrance, which could be beneficial [3]. |

| 3. Review Harvest & Storage | Audit Practices: Evaluate if harvest timing (e.g., crop maturity) and storage conditions (e.g., exposure to rain, compaction) are introducing variability [5]. | Poor storage can lead to biodegradation and loss of valuable carbohydrates. Implement covered storage or pelletization to preserve quality [5]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Tracking Seasonal Biomass Quality and Anaerobic Digestion Performance

This protocol outlines a method for correlating seasonal changes in biomass composition with biomethane potential, as applied in marine biomass studies [15].

- 1. Sampling: Collect biomass samples at regular intervals (e.g., biweekly or monthly) from your source (e.g., water body, field).

- 2. Taxonomic & Quantitative Analysis:

- Identify and count the dominant species/taxonomic groups in each sample.

- Measure the bulk biomass yield (e.g., g TS/L for algae, tons/ha for crops).

- 3. Chemical Analysis:

- Total Solids (TS) and Volatile Solids (VS): Standard methods for moisture and organic content.

- Total Organic Carbon (TOC) and Total Nitrogen (TN): To calculate the C/N ratio.

- Lipids, Proteins, and Carbohydrates: Using appropriate extraction and quantification methods (e.g., colorimetric assays for sugars).

- 4. Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Assay:

- Use mesophilic (35-37°C) periodic bioreactors.

- Inoculate with an active anaerobic digester sludge.

- Monitor biogas production and composition (e.g., using a gas chromatograph for methane content) until production ceases.

- Calculate the ultimate methane yield (mL CH₄/g VS) and production kinetics.

The workflow for this integrated analysis is summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol 2: Assessing the Impact of Environmental Stress on Feedstock Quality

This protocol is adapted from studies on the effect of drought on lignocellulosic biomass [3].

- 1. Correlate with Historical Data:

- Obtain long-term (multi-year) biomass yield and compositional data for your region of interest.

- Correlate this data with historical climate data, such as the Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI) during the growing season.

- 2. Controlled Stress Studies:

- Grow model energy crops (e.g., switchgrass, miscanthus) under controlled conditions.

- Apply defined water stress regimes to different test groups.

- At harvest, analyze the biomass for key quality parameters: glucan, xylan, lignin, and ash content, as well as the presence of specific extractives or inhibitors.

- 3. Conversion Efficiency Testing:

- Subject the stress-induced biomass samples to standardized pre-treatment and saccharification/fermentation protocols.

- Precisely measure the resulting sugar or biofuel yields and compare them to the control group.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Essential materials and analyses for investigating seasonal biomass quality.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Ergosterol | An index molecule used to estimate living fungal biomass on decaying plant litter, helping to quantify the microbial component of decomposition across seasons [16]. |

| [1-¹⁴C]Acetate | A radioactive tracer used to measure the in-situ production rate of fungi on biomass by tracking its incorporation into ergosterol [16]. |

| Standard Enzymes for Compositional Analysis | Specific cellulase, hemicellulase, and ligninase cocktails used to quantify structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass, enabling tracking of compositional changes [3]. |

| Meso- or Thermophilic Inoculum | Active anaerobic digester sludge used in Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) assays to determine the biomethanation potential of seasonal biomass samples [15]. |

| Solvents for Lipid/Extractive Analysis | Mixtures of chloroform, methanol, etc., used in Soxhlet or Folch extraction methods to determine the lipid content of biomass, a key quality parameter [15]. |

The table below synthesizes key quantitative findings on seasonal impacts from the literature.

| Biomass Type | Seasonal Period / Condition | Key Quality Parameters & Change | Impact on Output | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phytoplankton (Bay of Gdansk) | August (Cyanobacteria dominance) | TOC: 51.4% TSSugars: 599 mg/g TSLipids: 126 mg/g TS | Methane Yield: 270 ± 13 mL CH₄/g VS (Highest) | [15] |

| Phytoplankton (Bay of Gdansk) | October (Diatom dominance) | N/A (Lower sugar/lipid content implied) | Methane Yield: Lowest recorded | [15] |

| Dairy Slurry | Seasonal availability (Pasture-based system) | N/A (Overall biomethane potential reduced) | Total Biomethane Production: 21% reduction vs. constant supply | [2] |

| Corn Stover | Drought-stressed years (e.g., 2012 in US) | Carbohydrate Content: Significantly lower and more variable | Theoretical Ethanol Yield: Reduced; increases operational cost | [3] |

Economic and Sustainability Implications of Unmanaged Seasonal Variation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary economic impacts of seasonal variation in biomass feedstock supply? Seasonal availability leads to significant price volatility and operational inefficiencies. Key economic impacts include supply chain disruptions, increased storage and pre-treatment costs, and reduced profitability due to idled processing capacity during off-season periods. The solid biomass feedstock market identifies feedstock availability and seasonality as a major market restraint, which can lead to erratic supply and complicate resource management [18].

Q2: How does seasonality affect the chemical composition of biomass feedstocks? Seasonal shifts cause notable changes in nutrient dynamics and moisture content, directly impacting conversion process efficiency and biofuel yield. Long-term studies on organic materials show progressive rises in temperature and declining oxygen concentrations can alter nutrient stoichiometry, which is critical for biochemical conversion processes [19].

Q3: What strategies can mitigate seasonal supply challenges? Effective strategies include diversifying feedstock portfolios (agricultural residues, forest waste, municipal waste), developing advanced storage protocols, and implementing supply chain modeling tools. The integration of multi-feedstock flexible biorefineries has proven successful in industrial applications, allowing plants to switch between different biomass types based on seasonal availability [20] [18].

Q4: How does unmanaged seasonality affect sustainability metrics? Unmanaged seasonal variation can undermine sustainability through increased transportation emissions (from sourcing distant feedstocks), soil nutrient depletion (from improper residue harvesting), and inefficient energy conversion. Life Cycle Assessment studies highlight that optimal harvest timing and post-harvest management are crucial for maintaining carbon neutrality across biomass energy systems [20] [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inconsistent Conversion Yields Due to Seasonal Feedstock Variation

Symptoms

- Fluctuating bio-oil yields from thermochemical processes

- Variable biogas production in anaerobic digestion

- Inconsistent ethanol concentrations in fermentation

Diagnostic Procedures

- Feedstock Characterization: Conduct proximate and ultimate analysis to determine seasonal variation in moisture, ash, and elemental content.

- Process Parameter Monitoring: Track conversion efficiency against feedstock batches using standardized protocols.

- Comparative Testing: Run parallel experiments with feedstocks from different seasonal collections.

Solutions

- Blending Strategy: Create optimized mixtures of feedstocks from different seasonal sources to achieve consistent properties. Industrial case studies show blending can reduce yield variability by up to 30% [20].

- Pre-treatment Adjustment: Adapt pre-processing parameters based on seasonal characteristics:

- Summer-harvested biomass: Often requires less intensive drying

- Winter-collected residues: May need additional size reduction

Prevention

- Develop seasonal-specific operating protocols

- Establish feedstock stockpiling strategy with rotation system

- Implement rapid assessment techniques for incoming biomass

Problem 2: Supply Chain Disruptions from Seasonal Availability

Symptoms

- Processing facility downtime due to feedstock shortages

- Increased procurement costs during low-availability periods

- Quality degradation in stored biomass

Diagnostic Procedures

- Supply-Demand Analysis: Map seasonal availability patterns against processing requirements

- Inventory Assessment: Evaluate storage capacity and preservation efficiency

- Logistical Analysis: Identify transportation bottlenecks during transition periods

Solutions

- Feedstock Diversification: Incorporate complementary feedstocks with opposing seasonal availability:

| Feedstock Type | Peak Availability | Complementary Feedstock |

|---|---|---|

| Agricultural residues | Late summer/fall | Forest waste (year-round) |

| Energy crops | Summer | Municipal solid waste (year-round) |

| Algae biomass | Spring/summer | Agricultural residues (fall) |

- Strategic Partnerships: Develop contracts with multiple suppliers across different geographical regions [18]

Prevention

- Develop annual procurement plan with seasonal mapping

- Invest in flexible pre-processing equipment for multiple feedstock types

- Establish collaborative networks with other biorefineries for resource sharing

Experimental Protocols for Seasonal Variation Research

Protocol 1: Assessing Seasonal Impact on Biomass Composition

Objective Quantify variations in key biomass properties across seasonal collection periods to establish correlation with conversion efficiency.

Materials

- Biomass samples from consistent locations across multiple seasons

- Analytical balance (±0.0001 g precision)

- Moisture analyzer

- Calorimeter for heating value determination

- Fiber analysis system (NDF/ADF)

- Spectrophotometer for nutrient analysis

Procedure

- Sample Collection: Collect biomass samples monthly from designated locations using standardized harvesting techniques

- Immediate Processing:

- Divide samples for fresh and preserved analysis

- Record ambient conditions at collection

- Laboratory Analysis:

- Determine moisture content (105°C until constant weight)

- Ash content (575°C for 3 hours)

- Higher heating value (bomb calorimetry)

- Structural carbohydrates (NREL protocol)

- Data Normalization: Express all results on dry weight basis

Expected Outcomes

- Seasonal profile of compositional variation

- Correlation models between seasonal factors and biomass quality

- Predictive algorithms for process adjustment

Protocol 2: Storage Stability Across Seasonal Conditions

Objective Evaluate preservation methods for maintaining biomass quality during seasonal transitions.

Experimental Design

| Storage Method | Testing Intervals | Parameters Measured |

|---|---|---|

| Open-air stacking | 0, 30, 60, 90 days | Dry matter loss, Composition changes, Microbial activity |

| Covered storage | 0, 30, 60, 90 days | Moisture absorption, Temperature profile, Quality degradation |

| Ensiled biomass | 0, 30, 60, 90 days | pH, Organic acids, Nutrient preservation |

- Replicates: Minimum 3 per treatment

- Control: Fresh biomass analyzed at initiation

Analysis Methods

- Dry Matter Recovery: Weight tracking with moisture correction

- Compositional Stability: Monitor lignin, cellulose, hemicellulose ratios

- Biological Activity: Microbial counts and respiration rates

Research Workflow: Managing Seasonal Variation

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Seasonal Biomass Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ANKOM Fiber Analyzer | Determines neutral/acid detergent fiber content | Critical for tracking seasonal changes in structural carbohydrates; requires monthly calibration |

| NREL Standardized Protocols | Laboratory analytical procedures for biomass characterization | Provides reproducible methods for cross-seasonal comparison |

| Portable Moisture Meter | Field assessment of biomass moisture content | Essential for real-time quality assessment during seasonal transitions |

| Sterilization Equipment | Prevents microbial degradation during storage studies | Maintains experimental integrity in preservation trials |

| Gas Chromatography System | Analyzes volatile components and process intermediates | Detects seasonal variations in extractives and conversion inhibitors |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer | Measures thermal decomposition behavior | Tracks seasonal changes in biomass reactivity for thermochemical processes |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kits | Microbial community analysis in stored biomass | Identifies seasonal variations in degradation patterns |

Economic Impact of Seasonal Variation in Biomass Systems

| Parameter | Managed Seasonality | Unmanaged Seasonality | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedstock price fluctuation | 10-15% annual variation | 25-40% annual variation | Solid Biomass Feedstock Market Analysis [18] |

| Processing capacity utilization | 85-90% year-round | 60-75% (seasonal lows) | Biorefinery Case Studies [20] |

| Storage losses | 3-7% dry matter | 15-25% dry matter | Biomass Storage Research [20] |

| Transportation cost premium | 5-8% (optimized routing) | 15-30% (emergency sourcing) | Supply Chain Analysis [18] |

| Conversion efficiency range | ±2% seasonal variation | ±8-12% seasonal variation | Process Performance Data [21] |

Sustainability Metrics for Seasonal Management Strategies

| Strategy | Carbon Impact | Cost Efficiency | Implementation Timeline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedstock blending | Low improvement (5-10% reduction) | High (15-25% cost saving) | Short-term (3-6 months) |

| Multi-feedstock biorefinery | Medium improvement (15-25% reduction) | Medium (requires capital investment) | Medium-term (1-2 years) |

| Advanced storage systems | High improvement (25-40% reduction) | Low to medium (high initial cost) | Long-term (2-3 years) |

| Seasonal operational planning | Medium improvement (10-20% reduction) | High (operational changes only) | Immediate (1-3 months) |

Methodological Frameworks and Advanced Modeling for Seasonal Supply Chain Design

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support resource addresses common challenges researchers face when developing and applying Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) and Mixed Integer Non-Linear Programming (MINLP) models for planning under seasonal biomass constraints.

FAQ 1: Handling Biomass Seasonality in Optimization Models

Q1: What is the core challenge of biomass seasonality for optimization models? The primary challenge is the temporal mismatch between biomass availability and energy demand. Seasonal slurry availability can lead to a 21% reduction in total biomethane production and requires over twelve times the digestate recirculation compared to constant availability scenarios, causing significant operational inefficiencies and complicating long-term planning [2].

Q2: How does biomass quality variability impact my model's feasibility? Biomass quality, such as carbohydrate and ash content, is highly variable and directly affects conversion yields and operational costs. For instance, high drought stress years can reduce carbohydrate content, lowering theoretical ethanol yield. Models ignoring this variability can significantly underestimate true feedstock costs and overestimate biorefinery productivity [3].

Q3: Which optimization approach is better for seasonal planning, MILP or MINLP? The choice depends on your system's nature:

- MILP (Mixed Integer Linear Programming) is suitable when relationships between variables are linear, solving with methods like branch-and-bound. It's widely used for design and operation optimization of integrated energy systems [22] [23].

- MINLP (Mixed Integer Non-Linear Programming) is necessary for capturing nonlinear cost functions or device dynamics, such as the operational cost of solar PV in a hybrid renewable energy system. It is more computationally challenging but can provide a more realistic representation [24].

FAQ 2: Troubleshooting Model Formulation and Implementation

Q1: My large-scale MILP model for annual planning is computationally expensive. How can I solve it? For seasonal storage problems with many integer variables, use a time interval halving approach:

- Start by optimizing the annual operation with a small number of time steps (e.g., 26).

- Fix the storage state at the period's start, middle, and end.

- Bisect the annual period into two intervals and re-optimize each separately, again with a small number of time steps.

- Repeat the bisection and re-optimization until time steps reach the desired resolution [25]. This method manages computational load while maintaining solution accuracy.

Q2: How can I make my supply chain model more resilient to yield variability? Incorporate spatial and temporal yield and quality data over multiple years (e.g., 10+ years) into a multi-period stochastic optimization framework. Using long-term data, including drought indices, helps design robust supply chains that account for climate variability, preventing cost underestimation and supply disruptions [3].

Q3: My model does not converge to a feasible solution when I incorporate seasonal gas demand. What should I check? Facilitating seasonal gas demand often leads to larger digester sizes and large peaks/troughs in biogas flow rates [2]. Ensure your model includes:

- Adequate storage sizing constraints to buffer between production and demand.

- Realistic organic loading rate constraints that can handle the increased variation from seasonal feedstock.

- Operational flexibility such as optimized digestate recirculation to manage solids content [2].

Table 1: Impact of Seasonal Biomass Availability on Anaerobic Digestion Performance (Case Study: 100 dairy cows, 10 ha grass)

| Performance Metric | Impact of Seasonal vs. Constant Slurry Availability |

|---|---|

| Total Biomethane Production | 21% reduction [2] |

| Required Digestate Recirculation | Increased by over 12 times [2] |

| Greenhouse Gas Emissions | Increase of ~11 g CO₂-eq per MJ biomethane produced [2] |

| Digester Sizing | Smaller digester sizes possible, but with highly variable organic loading rate [2] |

Table 2: Key Economic and Environmental Findings from Integrated Energy System (IES) Case Studies

| Case Study / System Type | Key Finding | Optimization Method Used |

|---|---|---|

| IES with Seasonal Thermal Energy Storage [22] | Incorporating seasonal storage improved system flexibility, reduced total annual costs, and lowered CO₂ emissions compared to traditional systems. | MILP |

| RES-Hybrid System for EV Charging [24] | Over 24 hours, the optimal energy dispatch was: Solar PV (51.29%), Battery (13.5%), Grid (29.92%), and Wind (8.29%). | MINLP |

| Biorefinery Feedstock Supply [26] | Feasibility is highly sensitive to payment structures and yield variability. Scalable contracts that adjust to yield can improve adoption by farmers. | Nonlinear Land Allocation Model |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Baseline MILP Model for Integrated Energy System Design

Objective: To define the core structure of an MILP model for optimizing the design and operation of an urban energy system with seasonal biomass and energy demands [23].

Methodology:

- Define the Superstructure: Map all possible resources (biomass, electricity, heat), conversion technologies (boilers, CHP), storage (tanks, hydrogen), and transport technologies.

- Formulate the Objective Function: Typically, minimize total annualized cost, including capital, operational, and emission costs.

- Set Constraints:

- Demand Satisfaction: Total energy supplied must meet electricity and heat demand at each time step.

- Technology Capacity: Resource flow is limited by the installed capacity of each technology.

- Storage Balance: Storage inventory at time t equals inventory at t-1 plus input minus output.

- Resource Availability: Biomass supply is constrained by its seasonal profile.

- Logical Constraints: Use binary variables to model on/off states or technology selection.

- Implementation: Solve the model using MILP solvers (e.g., GAMS/BARON, MATLAB's

intlinprog).

Protocol 2: Integrating Long-Term Biomass Variability into Supply Chain Optimization

Objective: To create a resilient biomass supply chain model that accounts for multi-year spatial and temporal variability in yield and quality [3].

Methodology:

- Data Collection: Gather at least 10 years of historical data for:

- Biomass yield (e.g., corn stover tons/acre).

- Biomass quality (e.g., carbohydrate, ash content).

- Drought indices (e.g., DSCI - Drought Severity and Coverage Index).

- Scenario Generation: Use the historical data or statistical methods (e.g., Generative Adversarial Networks - GANs) to generate multiple plausible future scenarios representing climate variability [22].

- Model Formulation: Develop a multi-stage stochastic programming model.

- First-Stage Decisions: Strategic choices like biorefinery location, made before uncertainty is realized.

- Second-Stage Decisions: Tactical choices like biomass transport and storage, adapted to each yield scenario.

- Solution: The model is solved to minimize expected total cost across all scenarios, ensuring the supply chain design is robust against poor yield years.

Model Workflows and Pathways

Diagram 1: Model Selection and Application Workflow

Diagram 2: Resilient Biomass Supply Chain Planning

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Modeling Components

| Item / "Reagent" | Function in "Experiment" (Model) | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

MILP Solver (e.g., intlinprog) |

Finds optimal solutions to linear problems with integer constraints (e.g., on/off decisions). | Use an interval halving approach to manage computational load for long-term, high-resolution models [25]. |

| Stochastic Programming Framework | Incorporates uncertainty (e.g., in biomass yield) into optimization via multiple scenarios. | Requires multi-year historical data to generate realistic scenarios for yield and quality [3]. |

| Seasonal Storage Component | Balences seasonal supply-demand mismatches (e.g., hydrogen, thermal storage). | Crucial for increasing on-site utilization of renewable energy and improving economic feasibility [22] [25]. |

| Nonlinear Cost Function | Represents real-world, non-proportional costs (e.g., solar PV generation, device efficiency curves). | Necessitates the use of MINLP, which is more complex but provides higher model fidelity [24]. |

| Spatial Land Allocation Model | Models farmers' decisions to adopt energy crops based on contracts, yield risk, and land quality. | Critical for accurate near-term assessment of biomass feedstock availability for a biorefinery [26]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Biomass Supply Chain Optimization

Problem: Biofuel conversion yields are inconsistent, and operational costs are higher than projected. Primary Issue: This is often caused by unaccounted spatial and temporal variability in biomass yield and quality. Factors like drought stress can reduce crop yields by up to 48% and significantly alter chemical composition, impacting the theoretical ethanol yield [3]. Solution: Implement a supply chain optimization framework that incorporates multi-year climate and biomass quality data.

- Investigate Data: Collect long-term spatial data on key variability factors. The primary factor is the Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI) during growing degree days, available at a county level from the U.S. Drought Monitor [3]. Also, gather data on biomass quality, particularly carbohydrate, ash, and moisture content [3].

- Optimize Strategy: Use this data to optimize the location of biorefineries or biomass processing depots. A distributed supply system can reduce operational risk by 17.5% compared to a centralized one [3].

- Validate Model: Ensure your optimization model is calibrated with data from extreme weather years (e.g., the significant 2012 drought) to avoid underestimating long-term supply chain costs [3].

Diagram: Biomass Supply Chain Optimization

Guide 2: Troubleshooting GIS Performance for Large-Scale Analysis

Problem: GIS software (e.g., ArcGIS Pro) runs slowly when visualizing or analyzing multi-year, high-density biomass data. Primary Issue: Performance bottlenecks are common when handling large datasets and can stem from hardware limitations, data location, or non-optimized project settings [27]. Solution: A systematic approach to identify and resolve performance constraints.

- Hardware and Data Check:

- Run Assessment Tools: Use utilities like the ArcGIS Pro Performance Assessment Tool (PAT) to benchmark your system [27].

- Collocate Data and Client: Store your file geodatabases on a local solid-state drive (SSD). Avoid cloud storage drives (e.g., One Drive) for active projects and ensure your client is in the same data center as your enterprise database [27].

- Software and Map Optimization:

- Adjust Display Settings: Navigate to Project > Options > Display and lower the Rendering quality, set Antialiasing to "Fast," and disable "Enable hardware antialiasing" [27].

- Apply Map Best Practices:

- Use a visible scale range to prevent drawing all features at all zoom levels [28] [27].

- Generalize geometry for smaller scales [27].

- Ensure all data is in the same projection as the map to avoid on-the-fly projection calculations [27].

- Use definition queries or display filters to show only relevant data [27].

Guide 3: Troubleshooting High-Density Biomass Data Visualization

Problem: Maps of biomass location data are cluttered, with overlapping points that hide spatial patterns. Primary Issue: The default "draw all features" approach is ineffective for high-density data, especially when viewed at a small scale (zoomed out) [28]. Solution: Use aggregation and density-based visualization techniques available in GIS software like Map Viewer.

- Use Clustering: For point data, apply clustering to group nearby points into a single symbol. The symbol size should represent the number of features (e.g., biomass quantity) [28].

- Create a Heat Map: Display point features as a raster surface to emphasize areas with a higher relative density of biomass. This is ideal for showing "hotspots" [28].

- Apply Transparency: For overlapping polygons (e.g., yield by county), apply high transparency (90-99%) so that areas with more overlapping features appear darker, indicating higher density [28].

- Implement Binning: Aggregate point features into summary polygons (bins) of equal size. This provides a summarized view of the data within each geographic cell [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My biomass data has geographical components, but when is a map not the best visualization choice? A map should only be used if the primary story is geographical [29]. If the goal is to compare precise values between different geographical areas, a bar chart is often more effective. To show the rise and fall of a variable (e.g., regional yield over time), a line chart is superior. For comparing two variables for each area, a scatter plot is more appropriate [29].

Q2: What is the most accurate way to map biomass sample locations? Always use latitude and longitude coordinates [29]. Using partial or inexact geographical information (like just a city name) can lead to misplacement, such as confusing Cambridge, MA, with Cambridge, England [29].

Q3: For long-term strategic planning, why is it critical to use multi-year data instead of a single year's data? Optimizing a supply chain based on a single year's data, especially one with atypical weather, can lead to a non-robust strategy. For example, the nationwide drought in 2012 caused a 27% yield reduction for corn grain. If your model is not calibrated with such data, the cost of delivering biomass may be significantly underestimated, jeopardizing long-term biorefinery operations [3].

Q4: How can I improve the performance of geoprocessing tools when analyzing multi-year biomass data?

- Ensure your data has valid spatial and attribute indexes [27].

- When possible, write outputs to memory instead of disk [27].

- Use pairwise tools and leverage parallel processing where supported [27].

- For feature services and enterprise geodatabases, use SQL expressions in the Field Calculator, as they send a single request to the server, significantly speeding up calculations [27].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Factors Contributing to Biomass Variability

| Factor | Description | Impact on Biomass | Data Source/Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drought Stress | Low precipitation and soil water deficit during growing season. | Yield losses up to 48%; Alters chemical composition (e.g., reduced starch, lower structural sugars). | U.S. Drought Monitor (DSCI Index) [3] |

| Heat Stress | High mean air temperatures during critical growth stages. | Shortens crop life cycles; Reduces yield and harvest index. | Mean Air Temperature, Growing Degree Days [3] |

| Soil Characteristics | Properties like nutrient content, pH, and soil temperature. | Affects overall plant health and yield potential. | Soil surveys, historical management data [3] |

| Field Management | Practices such as irrigation, fertilizer use, and crop history. | Can mitigate or exacerbate the effects of environmental stressors. | Farm records, agricultural extension data [3] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomass Analysis

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| ArcGIS Pro | Desktop GIS software for advanced spatial analysis, modeling, and map authoring for biomass supply chain design [27]. |

| QGIS | Free, open-source desktop GIS software, cross-platform compatible, for general management and processing of geospatial data [30]. |

| Esri Geonet | Online community to ask questions and find authoritative answers specific to ArcGIS software and platforms [30]. |

| GIS StackExchange | Question-and-answer platform for specific GIS issues, particularly strong for open-source software like QGIS, GeoServer, and R [30]. |

| U.S. Drought Monitor | Provides weekly Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI) data at the county level, crucial for quantifying temporal variability [3]. |

| Python Scripts | For creating reproducible, updatable, and shareable geospatial workflows, ideal for complex or frequently re-run analyses [30]. |

Experimental Protocol: Integrating Spatiotemporal Variability into Biomass Supply Chain Models

Objective: To develop a resilient biomass supply chain strategy that accounts for spatial and temporal variability in yield and quality.

Methodology:

- Data Collection and Compilation:

- Yield Data: Gather at least 10 years of historical biomass yield data (e.g., corn stover) for the target supply region at the highest spatial resolution available (e.g., county level) [3].

- Quality Data: Collate corresponding data on biomass chemical composition (e.g., carbohydrate, ash, and moisture content) for the same years and regions [3].

- Climate Data: Obtain spatial-temporal climate data, focusing on the Drought Severity and Coverage Index (DSCI) during the growing season for each year in the dataset [3].

Data Integration and Model Formulation:

- Develop an optimization model that incorporates the compiled multi-year data as input parameters.

- The model should aim to minimize total supply chain cost while ensuring a consistent biomass supply to the biorefinery. Key decision variables include the location of biorefineries or processing depots and biomass sourcing strategies [3].

Model Validation and Scenario Analysis:

- Run the optimization model using data from different individual years to observe how the optimal supply chain configuration changes with climate conditions.

- Calibrate the final model using the full multi-year dataset to create a robust strategy that is resilient to climate variability [3].

Diagram: Multi-Year Data Integration

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary consequences of feedstock seasonality on anaerobic digestion (AD) operations?

Feedstock seasonality significantly impacts both the output and environmental footprint of AD systems. Key consequences include:

- Reduced Biomethane Production: Seasonal slurry availability can lead to a 21% reduction in total biomethane production compared to systems with constant feedstock availability [2].

- Increased Operational Demands: Managing seasonal feedstocks requires over 12 times the required digestate recirculation to maintain operational stability [2].

- Higher Greenhouse Gas Emissions: AD systems relying on pasture-based slurry can experience an increase in greenhouse gas emissions of approximately 11 g CO₂-eq per megajoule of biomethane produced [2].

- Supply Chain Complexity: Temporal variability in biomass yield and quality can lead to an underestimation of true biomass delivery costs and disrupt consistent biorefinery operations if not properly planned for [3].

FAQ 2: How can co-digestion (AcoD) improve process stability and methane yield?

Anaerobic co-digestion involves using multiple feedstocks with complementary properties [31].

- Synergistic Effects: Blending different substrates can create synergistic effects, boosting methane production and improving biodegradability. Some studies report methane yield increases of 30% or more through optimal co-digestion [31].

- Nutrient Balancing: AcoD allows for the balancing of critical parameters like the Carbon-to-Nitrogen (C/N) ratio and nutrient content (e.g., nitrogen, potassium, phosphorous), leading to more reliable and stable digestion processes compared to using a single feedstock [31].

FAQ 3: What strategies can mitigate biomass quality degradation during storage?

Effective storage is critical to preserving biomass quantity and quality.

- Moisture Control: For aerobic storage, the rate and extent of degradation increase significantly above 36% moisture (wet basis). Proper drying and moisture management are essential to limit dry matter loss [4].

- Anaerobic Storage (Ensiling): Ensiling corn stover and other biomasses is an effective long-term storage method. Research shows it results in only minor structural losses in carbohydrates and maintains bioconversion requirements [4].

- Blending for Preservation: Blending less stable feedstocks (e.g., flower strips) with more stable ones (e.g., corn stover) can significantly improve the overall silage quality and preserve dry matter during anaerobic storage [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Biogas/Methane Yield During Seasonal Feedstock Transitions

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Gradual decrease in gas production as one feedstock season ends. | • Imbalanced C/N ratio in new feedstock mix.• Lack of essential nutrients.• Inhibitory compounds in new feedstock. | 1. Analyze Feedstock: Determine the C/N ratio and key nutrients of incoming feedstocks [31].2. Optimize Blend: Use a data-driven model to calculate the optimal blending ratio to maximize the Biomethane Potential (BMP). A sample protocol is provided below [31].3. Monitor Digester: Closely monitor pH, volatile fatty acids (VFAs), and alkalinity during the transition period. |

| Sudden drop in gas production after introducing a new feedstock. | • Toxic compounds (e.g., ammonia, sulfides).• Sharp change in organic loading rate (OLR).• Significant temperature fluctuation. | 1. Stop Feeding: Immediately halt the introduction of the new feedstock.2. Assess Toxicity: Review the composition of the new feedstock for potential inhibitors.3. Re-inoculate: Consider re-inoculating the digester with fresh sludge to re-establish a healthy microbial community.4. Gradual Re-introduction: If the feedstock is deemed safe, re-introduce it at a very low inclusion rate and increase gradually. |

Problem 2: Handling and Clogging Issues with Thickened or High-Solid Digestate

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Increased viscosity of digestate, making it difficult to pump. | • Over-recirculation of digestate to manage seasonal slurry.• High solids content in the feedstock. | 1. Optimize Recirculation: While recirculation is necessary, monitor and adjust the rate to prevent excessive solids buildup [2].2. Use Appropriate Equipment: Ensure pumps and syringes are designed for thick, viscous fluids. O-ring syringes are recommended over standard rubber grommet plungers, which stick and are hard to push [32].3. Dilution: If temporarily necessary, use a controlled amount of process water to reduce viscosity, being mindful of its impact on digester volume and OLR. |

| Frequent clogging of feed lines and injectors. | • Presence of fibrous, non-degraded material.• Incomplete blending or particle size reduction. | 1. Pre-processing: Improve feedstock pre-treatment (e.g., shredding, milling) to reduce particle size.2. High-Power Blending: Use industrial-grade blenders (e.g., Vitamix, Blendtec) that can completely liquify fibrous materials to prevent clogs [32].3. Line Maintenance: Implement a regular flushing and maintenance schedule for all feed lines. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol: Data-Driven Feedstock Blending Optimization for BMP Maximization

This protocol is based on a model designed to support decision-making for anaerobic co-digestion layouts [31].

1. Objective: To determine the optimal mass fractions of up to three different substrates in a blend that maximizes the biochemical methane potential (BMP).

2. Materials:

- Feedstock Database: A compiled database of substrate characteristics, including C/N ratio, Biodegradability (BD), and lignin/lipid content [31].

- Mathematical Model: The objective function and constraints as described below [31].

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Select Substrates. Choose up to three candidate substrates from the database (e.g., Manure, Agricultural Waste, Organic Waste).

- Step 2: Define Constraints. Input the operational constraints, which are typically the availability or maximum volume capacity of each substrate.

- Step 3: Run Optimization. The model uses the following objective function to calculate the optimal mass fractions (x₁, x₂, x₃):

fobj = x₁*EBMP₁ + x₂*EBMP₂ + x₃*EBMP₃ + (x₁x₂ + x₁x₃ + x₂x₃ + x₁x₂x₃)*BMPmixwhereEBMPis the expected BMP for each substrate, andBMPmixis a synergistic factor for the mixture [31]. - Step 4: Validate and Apply. The model's output is the recommended blending ratio. This should be validated through small-scale batch testing before full-scale implementation.

Quantitative Data on Seasonal and Storage Impacts

Table 1: Impact of Seasonal Feedstock Availability on AD System Performance [2]

| Performance Metric | System with Constant Slurry | System with Seasonal Slurry | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Biomethane Production | Baseline | Reduced by 21% | -21% |

| Digestate Recirculation | Baseline Requirement | >12x baseline requirement | >1200% |

| Greenhouse Gas Emissions | Baseline | Increased by ~11 g CO₂-eq/MJ | +11 g CO₂-eq/MJ |

Table 2: Biomass Storage Conditions and Dry Matter Loss [4]

| Storage Condition | Key Parameter | Impact on Dry Matter Loss |

|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Storage | Moisture Content | Increases significantly above 36% moisture (wet basis) |

| Summer vs. Winter | Ambient Temperature | Higher losses during summer storage regardless of feedstock |

| Anaerobic Storage (Ensiling) | Pre-treatment | Hot water extracted wood chips had much lower losses after 180 days vs. fresh chips |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Feedstock Blending Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| High-Performance Blender | To completely liquify fibrous biomass and seeds, preventing clogs in experimental feeding systems. Essential for creating homogenous blends [32]. |

| O-Ring Syringes | For reliably pumping and dispensing thicker, blended feedstocks in lab-scale reactors without the sticking associated with standard rubber grommet plungers [32]. |

| Feedstock Database | A curated collection of substrate properties (TS, VS, C/N, lipids, lignin). Critical for informing blending models and understanding substrate interactions [31]. |

| Data-Driven Optimization Model | A computational tool that uses polynomial objective functions to calculate optimal feedstock blends to maximize BMP, incorporating supply chain constraints [31]. |

Process Visualization

Feedstock Blending Optimization Workflow

Seasonal Biomass Management Strategy

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent Feedstock Quality Due to Seasonal Variation

- Problem: Biomass moisture and ash content fluctuate with seasons, causing ignition stability issues, reduced flame temperature, and negative impacts on conversion process efficiency [33].

- Solution:

- Pre-processing Protocol: Implement a mandatory drying and compositional analysis step for all incoming seasonal feedstock.

- Blending Procedure: Develop a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) for blending feedstocks from different seasons to achieve a consistent average moisture and ash content. Refer to the Biomass Pre-processing Blending Table below for guidelines.

- Validation: Use a bomb calorimeter to check the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of blended batches to ensure consistency before conversion.

Issue 2: Supply Disruptions and Inventory Shortfalls

- Problem: Seasonal unavailability or disruption at collection facilities risks biorefinery operations [34].

- Solution: