Life Cycle Assessment for Bioenergy Systems: Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) as applied to bioenergy systems, addressing the needs of researchers and professionals in the field.

Life Cycle Assessment for Bioenergy Systems: Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) as applied to bioenergy systems, addressing the needs of researchers and professionals in the field. It explores the foundational principles of LCA, detailing the critical methodological distinctions between attributional and consequential approaches. The content delves into persistent application challenges, including data quality, system boundary definition, and accounting for indirect land-use change. Furthermore, it reviews emerging trends such as social LCA and life cycle sustainability assessment, and offers insights into harmonization efforts and comparative analyses of different bioenergy pathways. This synthesis is designed to inform robust sustainability evaluations and guide strategic decision-making in bioenergy development.

The Role and Rising Importance of LCA in Bioenergy

Bioenergy, derived from organic materials, is a cornerstone of global strategies to transition toward renewable energy and mitigate climate change. However, its environmental benefits are not inherent; they are contingent on specific feedstock choices, supply chains, and conversion technologies. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic, data-driven methodology that is critical for quantifying the full environmental footprint of bioenergy systems, from raw material extraction to end-of-life, thereby moving beyond the carbon neutrality assumption [1]. For policymakers, LCA provides the scientific rigor necessary to distinguish between truly sustainable bioenergy pathways and those that merely shift environmental burdens, thus ensuring that bioenergy policies effectively contribute to long-term climate and sustainability goals rather than inadvertently exacerbating the problems they aim to solve [1].

This whitepaper details how LCA is indispensable for crafting evidence-based bioenergy policy. It outlines the core LCA methodology, demonstrates its application with quantitative data, and explores advanced visualization and data analysis techniques that are transforming the field. By adopting a comprehensive LCA framework, policymakers, researchers, and industry professionals can optimize bioenergy systems for genuine sustainability, avoiding the pitfalls of suboptimal decision-making.

The Core LCA Methodology: A Standardized Framework

The LCA methodology is internationally standardized by the ISO 14040 and 14044 series, ensuring consistency, transparency, and credibility [1]. The framework comprises four interlinked phases, creating a robust structure for comprehensive environmental assessment.

Figure 1: The Four Phases of LCA According to ISO 14040/14044

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

This initial phase establishes the study's purpose, intended audience, and the product system to be assessed. A critical element is defining the system boundary, which determines which life cycle stages and processes are included [1]. For bioenergy, this typically encompasses a cradle-to-grave approach, including:

- Feedstock Production: Cultivation, harvesting, and transportation of biomass.

- Feedstock Processing: Preparation and conversion of biomass (e.g., anaerobic digestion for biogas, fermentation for ethanol).

- Energy Conversion: Generation of electricity, heat, or fuel.

- Distribution & Use.

- End-of-Life: Management of co-products and wastes.

The functional unit—a quantified measure of the system's performance, such as "1 megajoule of energy"—is also defined here to enable fair comparisons [1].

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The LCI phase involves the meticulous collection and calculation of all input and output data associated with the product system within the defined boundary [1]. This includes:

- Resource consumption (e.g., water, fertilizer, land).

- Energy inputs (e.g., diesel for farming, electricity for processing).

- Emissions to air, water, and soil (e.g., CO₂, CH₄, N₂O, nutrients). For large-scale bioenergy LCA, this process is often automated, creating vast datasets for all potential configurations within a defined parameter space [2].

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

In the LCIA phase, the inventory data is translated into potential environmental impacts using scientifically established models [1]. Common impact categories relevant to bioenergy include:

- Global Warming Potential (GWP)

- Acidification Potential

- Eutrophication Potential

- Land Use

- Water Consumption

Phase 4: Interpretation

The final phase involves analyzing the results from the LCIA, checking their sensitivity and consistency, and drawing conclusions and recommendations to inform decision-making [1]. This phase is crucial for identifying environmental "hotspots," comparing design alternatives, and validating the underlying data, especially when dealing with large-scale results [2].

LCA's Critical Role in Bioenergy Policy Development

LCA moves bioenergy policy beyond simplistic carbon accounting by providing a multi-faceted evidence base for decision-making. Its applications are foundational to effective and credible policy instruments.

Table 1: Key Policy Applications of Bioenergy LCA

| Policy Application | LCA Function | Impact on Sustainable Bioenergy Policy |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Compliance & Certification | Provides the quantitative basis for regulations like the EU's Renewable Energy Directive (RED) and eco-labeling schemes [1]. | Ensures that only bioenergy pathways meeting strict sustainability and GHG savings thresholds receive government support or market access. |

| Identification of Hotspots | Pinpoints stages in the life cycle with the highest environmental impact (e.g., land-use change from feedstock cultivation) [2]. | Allows policymakers to target regulations and incentives to mitigate the most significant environmental damages. |

| Technology & Feedstock Benchmarking | Enables comparative assessment of different bioenergy pathways (e.g., biogas vs. renewable diesel) against each other and fossil fuels [1] [2]. | Guides R&D funding and market incentives toward the most promising and lowest-impact technologies and feedstocks. |

| Supply Chain Optimization | Evaluates the environmental footprint of logistics, transportation, and supplier processes [1]. | Informs infrastructure investments and sourcing strategies to minimize overall environmental impact. |

Quantitative LCA Data for Bioenergy Systems

The following tables synthesize illustrative LCA data for key bioenergy pathways, highlighting the comparative performance and critical data points that inform policy.

Table 2: Comparative Life Cycle Impact Assessment for Select Bioenergy Pathways (per MJ of Energy)

| Impact Category | Unit | Corn Ethanol | Sugarcane Ethanol | Renewable Diesel from Waste Oil | Biogas from Manure | Fossil Diesel (Reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | kg CO₂-eq | 0.06 - 0.10 | 0.02 - 0.05 | 0.02 - 0.04 | -0.05 - 0.02 | 0.08 - 0.10 |

| Acidification Potential | kg SO₂-eq | 0.0005 - 0.0015 | 0.0003 - 0.0008 | 0.0001 - 0.0003 | 0.0004 - 0.0007 | 0.0004 - 0.0006 |

| Eutrophication Potential | kg PO₄-eq | 0.0004 - 0.0010 | 0.0002 - 0.0006 | 0.00001 - 0.00005 | 0.0003 - 0.0008 | 0.00002 - 0.00004 |

| Land Use | m²a | 0.2 - 0.5 | 0.1 - 0.3 | 0.001 - 0.01 | 0.01 - 0.05 | 0.001 - 0.005 |

Table 3: Life Cycle Inventory Data for Key Bioenergy Feedstocks (per Functional Unit)

| Feedstock | Functional Unit | Water Consumption (L) | Fertilizer (N, kg) | Fertilizer (P₂O₅, kg) | Energy Input (MJ) | Net Energy Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn (for ethanol) | 1 kg of corn | 500 - 1200 | 0.12 - 0.20 | 0.06 - 0.10 | 2.5 - 4.5 | 1.2 - 1.6 |

| Sugarcane (for ethanol) | 1 kg of cane | 150 - 250 | 0.08 - 0.15 | 0.04 - 0.08 | 1.5 - 3.0 | 7.0 - 9.0 |

| Switchgrass | 1 kg of DM | 200 - 400 | 0.04 - 0.10 | 0.02 - 0.05 | 0.8 - 1.5 | 10.0 - 15.0 |

| Algae (open pond) | 1 kg of biomass | 500 - 2000 | 0.15 - 0.30 | 0.08 - 0.15 | 15 - 30 | 0.5 - 1.2 |

Advanced LCA: Visualization and Large-Scale Data Analysis

With the automation of LCA workflows, practitioners can generate millions of data points for a single product system [2]. Interpreting these large-scale results requires sophisticated visualization techniques to identify trends, hotspots, and outliers that might be missed in a conventional assessment.

Visual Analysis for Large-Scale LCA

A case study on an adaptive building façade, which generated 1.25 million LCA results, demonstrated the power of specific visualizations [2]:

- Box Plots: Effectively communicated the statistical distribution of results, identified hotspots, assessed parameter sensitivity, and provided benchmarks.

- Color-Coded Scatter Plots: Allowed for the visualization of complex parameter dependencies and correlations between different environmental impacts.

- Interactive Dashboards: Enabled users to directly engage with the data, filtering and drilling down into specific areas of interest for efficient analysis. This aligns with the "information seeking mantra of overview, zoom and filter, and details on demand" [2].

Figure 2: Workflow for Automated Large-Scale LCA and Visual Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Tools for LCA

LCA practice relies on a suite of software tools, databases, and methodologies. The following table details essential "research reagents" for conducting a robust bioenergy LCA.

Table 4: Essential Tools and "Reagents" for Bioenergy LCA Research

| Tool / "Reagent" | Category | Function in Bioenergy LCA |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software (e.g., OpenLCA, GaBi, SimaPro) | Software Platform | Provides the computational engine for modeling the product system, managing inventory data, and calculating impact assessment results. |

| Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Databases (e.g., ecoinvent, USDA LCA Commons) | Database | Contains validated, background data on common materials, energy, and processes, providing the foundational data for building the LCA model. |

| Impact Assessment Methods (e.g., ReCiPe, TRACI, CML) | Methodology | A set of characterization factors that translate inventory flows (e.g., kg of CO₂) into impact category results (e.g., Global Warming Potential). |

| Statistical Analysis Tools (e.g., R, Python with pandas) | Analysis Tool | Enables the processing, statistical analysis, and visualization of large-scale LCA datasets to identify patterns, trends, and sensitivities. |

| Uncertainty & Sensitivity Analysis | Methodology | A set of mathematical procedures to quantify the uncertainty in the results and test how sensitive they are to changes in key input parameters. |

Life Cycle Assessment is not merely an academic exercise; it is an indispensable, evidence-based tool for crafting sustainable bioenergy policy. By quantifying environmental impacts across the entire value chain, LCA provides the transparency and rigor needed to validate sustainability claims, avoid unintended consequences, and direct support toward the most beneficial bioenergy pathways. The ongoing advancement in LCA, particularly through automation and sophisticated data visualization, is enhancing its power to handle complex systems and provide clear, actionable insights. For policymakers committed to a genuinely sustainable energy future, integrating comprehensive LCA into the heart of regulatory frameworks and decision-making processes is not an option—it is a critical necessity.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic, scientific method used to evaluate the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life cycle, from raw material extraction to disposal, use, or recycling [1]. Recognized worldwide by the ISO 14040 and 14044 series, this tool is the gold standard for environmental impact assessment, enabling businesses and researchers to spot and improve products, services, and processes that harm the environment [1]. In the context of bioenergy systems research, LCA provides critical data to answer key questions about carbon emissions from production, impacts of raw material extraction, resource use in manufacturing, and optimization of end-of-life processes [1].

The methodology is built on the foundation of life cycle thinking, which emphasizes a cradle-to-grave perspective. This holistic view prevents problem shifting from one life cycle stage to another or from one environmental impact to another. For bioenergy systems, this is particularly crucial, as the environmental benefits can be significantly affected by choices made in feedstock cultivation, processing technologies, and transportation logistics.

The Four Phases of LCA According to ISO Standards

The international standards ISO 14040 and 14044 define a structured framework for conducting LCA, comprising four interdependent phases [3] [1]. This standardized format ensures that assessments are credible, transparent, and comparable—essential qualities for robust bioenergy research.

Diagram 1: The iterative four-phase framework of Life Cycle Assessment per ISO 14040/14044.

Goal and Scope Definition

The first phase establishes the foundation and boundaries of the study. Researchers must define clear objectives, specifying the product system under investigation, the intended application of the results, and the target audience [3]. For bioenergy systems, this includes defining the functional unit (e.g., 1 MJ of energy produced), which provides a standardized basis for comparison [4]. The system boundaries determine which processes are included, such as whether to account for carbon sequestration from atmosphere during feedstock growth or indirect land-use changes. A precisely defined scope is critical for ensuring the LCA's relevance and credibility, particularly when comparing different bioenergy pathways.

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The Life Cycle Inventory phase involves compiling and quantifying all relevant inputs and outputs throughout the product's life cycle [3]. This data-intensive step requires collecting information on energy consumption, raw material inputs, emissions to air and water, and waste generation for each process within the system boundaries. For bioenergy LCAs, this includes data on agricultural inputs (fertilizers, water), feedstock yields, transportation distances, conversion process efficiencies, and end-use emissions. Data quality is paramount; practitioners should prioritize primary data from suppliers and operational processes, supplemented by credible secondary databases when necessary [3]. Structured templates and standardized data collection methods ensure accuracy and facilitate verification.

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

In the LCIA phase, the inventory data is translated into meaningful environmental impact categories [3]. This involves selecting appropriate impact categories (e.g., global warming potential, acidification, water use) and applying standardized characterization factors to convert inventory data into common equivalents (e.g., CO₂-equivalents for climate change). The following table summarizes common impact categories and their characterization approaches particularly relevant to bioenergy systems:

Table 1: Common impact categories and characterization factors in LCIA

| Impact Category | Indicator | Common Unit | Relevance to Bioenergy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential | Radiative forcing | kg CO₂-equivalent | Carbon neutrality assessment, biogenic carbon accounting |

| Acidification | Hydrogen ion potential | kg SO₂-equivalent | Emissions from combustion and fertilizer application |

| Eutrophication | Nutrient enrichment | kg PO₄-equivalent | Fertilizer runoff from feedstock cultivation |

| Photochemical Oxidant Formation | Ozone creation potential | kg NMVOC-equivalent | Emissions from combustion processes |

| Land Use | Soil quality, biodiversity | Points/m²a | Direct and indirect land use change |

Interpretation

The final phase involves analyzing the findings from the inventory and impact assessment phases to reach conclusions and provide recommendations [3]. Researchers identify significant environmental hotspots, evaluate the completeness and sensitivity of the data, and assess the uncertainty of the results. For bioenergy research, this might reveal that the majority of a biofuel's climate impact comes from feedstock cultivation rather than processing, directing attention to more sustainable agricultural practices. The interpretation must be transparent about limitations and uncertainties to provide a reliable foundation for decision-making.

Core Principles of Life Cycle Thinking

Life Cycle Assessment is underpinned by several core principles that guide its methodology and application, especially in complex fields like bioenergy research.

- Cradle-to-Grave Perspective: LCA considers the entire value chain, from resource extraction ("cradle") through manufacturing, transportation, and use, to final disposal ("grave") [1]. This prevents burden shifting between life cycle stages and provides a comprehensive picture of the true environmental impacts.

- Reliance on Quantitative Data: As a science-based methodology, LCA prioritizes measurable, quantitative data over qualitative assertions [1]. This empirical foundation is crucial for objectively comparing different bioenergy pathways and validating environmental claims.

- Multi-Criteria Assessment: Unlike a carbon footprint which focuses on a single impact, LCA typically assesses multiple environmental impact categories simultaneously [3]. This prevents solutions that improve one environmental aspect while worsening others.

- Iterative Nature: The LCA process is inherently iterative [3]. As shown in Diagram 1, findings from later stages often necessitate refinements to the goal and scope definition, leading to a more robust and accurate assessment.

LCA Application in Bioenergy Research

In bioenergy systems, LCA serves as a critical tool for quantifying the environmental benefits and trade-offs of renewable energy alternatives to fossil fuels. The ARENA LCA Guidelines for Bioenergy Projects provide a specialized framework for these assessments, emphasizing alignment with international standards like the EU Renewable Energy Directive and CORSIA for sustainable aviation fuel [4].

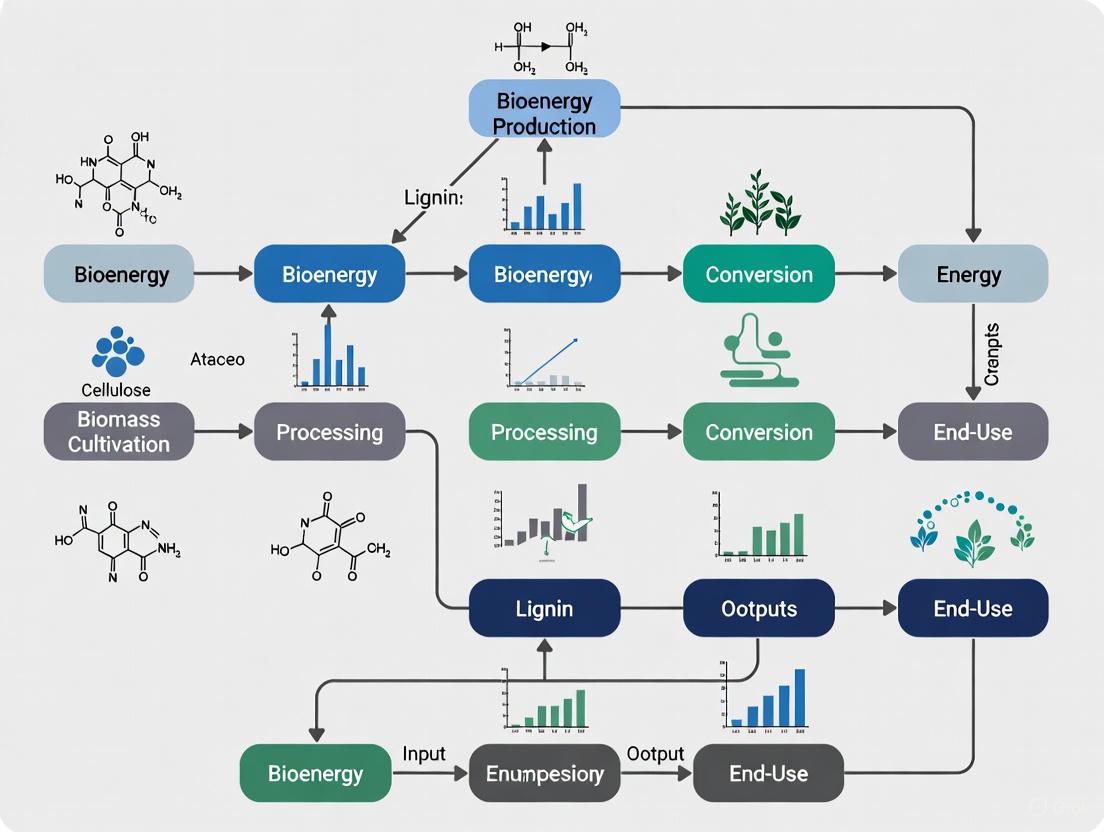

Bioenergy LCAs must address several unique methodological considerations, particularly concerning biogenic carbon cycles, land use change (both direct and indirect), and co-product allocation. The 2025 update to the ARENA guidelines offers flexibility through "commodity" and "project" specific LCA approaches, with decision trees to help researchers select the appropriate method [4]. The complex interrelationships in a bioenergy system's life cycle can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 2: Key interrelationships in a bioenergy system's life cycle, highlighting material and energy flows.

The application of LCA in bioenergy has revealed several critical insights. For instance, studies often show that while bioenergy systems can significantly reduce fossil fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions compared to conventional energy sources, they may contribute to other environmental impacts such as eutrophication and acidification due to agricultural practices. This underscores the importance of the multi-criteria approach inherent to LCA.

Conducting a robust LCA requires specialized tools and resources. The selection of appropriate software and databases is critical for efficiently managing complex calculations and ensuring compliance with international standards.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and tools for conducting Life Cycle Assessment

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software Platforms | Ecochain, OpenLCA, SimaPro, GaBi | Automate complex calculations, manage life cycle inventory data, facilitate impact assessment, and generate standardized reports [3]. |

| Specialized Databases | Ecoinvent, US LCI Database, ELCD | Provide validated secondary data for background processes (e.g., electricity grids, material production, transportation) when primary data is unavailable [3]. |

| Methodological Guidelines | ISO 14040/14044, ARENA LCA Guidelines, EU RED III | Ensure standardized, credible, and compliant assessments by providing mandatory principles, frameworks, and requirements [3] [4]. |

| Impact Assessment Methods | ReCiPe, CML, TRACI | Provide standardized characterization factors for translating inventory data into environmental impact scores across multiple categories [3]. |

LCA software platforms are particularly valuable for their ability to automate calculations, simplify data collection, and enable robust scenario modeling [3]. For example, open-source options like OpenLCA offer comprehensive modeling capabilities, while commercial solutions like SimaPro are known for robust analytics and precise impact assessments suitable for Environmental Product Declarations.

Mastering the core principles of Life Cycle Assessment—from the foundational concept of life cycle thinking to the detailed methodologies of impact assessment—is essential for advancing credible bioenergy research. The standardized four-phase framework (Goal and Scope, Inventory Analysis, Impact Assessment, and Interpretation) provides a rigorous structure for generating transparent, comparable, and actionable results. For the bioenergy sector, specifically, applying these principles through specialized guidelines like those from ARENA ensures that assessments accurately capture the unique aspects of bioenergy systems, from biogenic carbon cycles to land use implications. As a decision-support tool, LCA empowers scientists, engineers, and policymakers to make informed choices that genuinely advance sustainability goals in the energy transition.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as a critical scientific methodology for informing and implementing greenhouse gas (GHG) targets and renewable energy directives worldwide. For researchers and scientists working with bioenergy systems, understanding this policy-LCA nexus is essential for ensuring that climate strategies deliver genuine emissions reductions rather than merely shifting environmental burdens. The global push for decarbonization, particularly in energy systems, relies on robust, quantitative environmental assessments to guide decision-making and validate claims of sustainability. GHG Protocol Corporate Standard and ISO 14040/14044 standards provide complementary frameworks for measuring emissions, but they differ significantly in scope, boundaries, and application within policy contexts [5].

For bioenergy specifically, LCA plays an indispensable role in quantifying emissions across the entire value chain—from feedstock production and transportation through conversion processes and final energy utilization. This cradle-to-grave approach is particularly crucial for bioenergy systems due to the complex carbon dynamics, potential indirect land-use changes, and varied feedstock sources that can dramatically influence overall climate impacts. Circular economy principles further emphasize the importance of system-level thinking, where biomass energy transforms agricultural, municipal, and forestry wastes into value-added energy while minimizing environmental consequences [6]. As energy consumption is projected to increase by 50% by 2050, the integration of scientifically-grounded LCA into policy frameworks becomes increasingly critical for achieving long-term sustainability goals [6].

Foundational Policy Frameworks and Their LCA Requirements

The GHG Protocol: Corporate Emissions Accounting

The GHG Protocol Corporate Standard establishes a globally recognized framework for corporate GHG accounting that directly influences how organizations report emissions and demonstrate progress toward climate targets. This standard categorizes emissions into three scopes that determine accountability and reporting requirements [5]:

- Scope 1: Direct emissions from owned or controlled sources

- Scope 2: Indirect emissions from the generation of purchased electricity, steam, heating, and cooling

- Scope 3: All other indirect emissions that occur across the value chain, divided into 15 categories

For electricity-related emissions specifically, the GHG Protocol mandates dual reporting through location-based and market-based approaches. The location-based method reflects the average emissions intensity of the local grid, while the market-based approach accounts for an organization's specific procurement decisions, including Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) and Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) [5]. This distinction creates a direct policy mechanism that incentivizes renewable energy investment through improved emissions reporting.

Renewable Energy Directives and Certification Systems

Renewable energy directives typically incorporate LCA principles to establish sustainability criteria and ensure the credibility of renewable energy claims. These frameworks often recognize Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs) and analogous instruments like Guarantees of Origin (GOs) in Europe as tools for tracking and attributing renewable electricity generation to specific consumers [5]. Under the GHG Protocol's market-based approach, these instruments allow organizations to claim lower emissions from their purchased electricity, creating a direct policy driver for renewable energy procurement [5].

However, a significant challenge arises from the different treatment of these instruments across accounting frameworks. While the GHG Protocol explicitly recognizes RECs for reducing reported Scope 2 emissions, ISO LCA standards do not explicitly address whether RECs can be used to determine the "actual production mix" of electricity [5]. This creates methodological inconsistencies that researchers must navigate when conducting LCAs for policy compliance.

LCA Methodologies for Bioenergy Systems

Standards and Harmonization Approaches

LCA methodologies for bioenergy systems primarily follow ISO 14040/14044 standards, which establish industry-wide rules for which processes are included and how to assign environmental burdens to products [5]. These standards provide the systematic framework necessary for conducting cradle-to-grave assessments that cover everything from raw material extraction ("cradle") through manufacturing/production ("gate") to disposal ("grave") [5].

Significant efforts have been made to harmonize LCA approaches across electricity generation technologies to reduce variability in published results and improve policymaking. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has conducted extensive LCA harmonization projects, reviewing approximately 3,000 life cycle assessments for utility-scale electricity generation, including storage technologies [7]. This work has demonstrated that while harmonization doesn't significantly change the central tendency of emissions estimates for any technology, it does substantially reduce variability, creating more reliable data for policy decisions [7].

Table: LCA Harmonization Impact on GHG Emission Estimates for Electricity Generation Technologies [7]

| Technology Type | Pre-Harmonization Variability | Post-Harmonization Variability | Central Tendency (median) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solar PV | High | Significantly Reduced | Unchanged |

| Wind | High | Significantly Reduced | Unchanged |

| Biomass | High | Significantly Reduced | Unchanged |

| Natural Gas | Moderate | Reduced | Unchanged |

| Coal | Moderate | Reduced | Unchanged |

Key Methodological Considerations for Bioenergy

Bioenergy systems present unique methodological challenges for LCA that researchers must address to ensure accurate policy-relevant results:

System Boundaries: Comprehensive bioenergy LCAs should include emissions from feedstock production, transportation, conversion processes, distribution, and end-use, while also accounting for co-products through allocation or system expansion [6].

Temporal Considerations: The timing of carbon emissions and sequestration is particularly important for bioenergy systems, as carbon neutrality assumptions may not hold over relevant policy timeframes [6].

Impact Categories: Beyond global warming potential, comprehensive bioenergy LCAs should evaluate a broader set of environmental impacts, including acidification potential, eutrophication potential, water consumption, land use, and biodiversity impacts [6]. Studies often overemphasize GWP while neglecting other critical impact categories, potentially leading to suboptimal policy decisions [6].

Indirect Effects: The most methodologically challenging aspect of bioenergy LCA involves accounting for indirect land-use change (ILUC) and other market-mediated effects that can significantly influence net emissions [6].

LCA Applications in Policy Implementation

Carbon Accounting and Emissions Reporting

LCA provides the foundational data for corporate carbon accounting under the GHG Protocol, particularly for Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions related to electricity consumption. The following table illustrates how different accounting approaches yield substantially different results for the same electricity consumption:

Table: Electricity-Related Emissions Reporting Under Different Accounting Frameworks [5]

| Electricity Source | GHG Protocol Scope 2 (g CO₂e/kWh) | GHG Protocol Scope 3.3 FERA (g CO₂e/kWh) | LCA (Cradle-to-Grave) (g CO₂e/kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Power (location-based) | 363 | 15.3 | 410 |

| Grid Power (market-based) | 363 | 15.3 | 410 |

| Grid Power (market-based with REC) | 0 | 15.3 | 410* |

| Utility-Scale Solar | 0 | 15.3 | Varies by technology |

*Good practice to calculate LCA results with electricity carbon intensity of 410 g CO₂e/kWh and cradle-to-grave carbon intensity of electricity type covered by contract [5]

For bioenergy systems, the policy implications of these accounting differences are significant. A company may report zero Scope 2 emissions from electricity consumption through REC purchases under the GHG Protocol, but a comprehensive LCA would still show emissions from the entire life cycle, including manufacturing, construction, and end-of-life phases of electricity generation infrastructure [5].

Advanced Bioenergy Systems and Policy Integration

Emerging bioenergy technologies present both opportunities and challenges for policy-driven LCA applications. Systems like bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), and renewable natural gas (RNG) offer potential carbon-negative pathways but require sophisticated LCA methodologies to accurately quantify net emissions [6].

The integration of LCA with energy system modeling tools represents an important methodological advancement for policy-relevant analysis. One study coupled LCA with the EnergyPLAN energy system modeling tool, using consequential LCA to provide decision-support in a national context [8]. This approach accounted for changes to marginal suppliers and included avoided impacts connected to sector integration, enabling waste heat utilization [8]. The results demonstrated that impacts on the broader energy system must be included when determining optimal integration pathways, as global warming impacts from electricity production almost doubled when using an average mix compared to the marginal mix from EnergyPLAN [8].

LCA-Policy Integration Framework for Bioenergy Systems

Current Challenges and Research Frontiers

Methodological Gaps and Standardization Needs

Despite advances in LCA methodologies, significant challenges remain in their application to bioenergy policy:

Geographical Limitations: Current LCA research focuses predominantly on developed regions like Europe and North America, creating gaps in our understanding of environmental impacts in developing regions where biomass utilization is often more critical due to energy access challenges [6].

Circular Economy Integration: Few studies successfully integrate CE principles into operational LCA frameworks with measurable links between environmental impact categories and CE pillars like resource recovery, system resilience, or circular input flows [6].

Impact Category Expansion: Most bioenergy LCAs overemphasize global warming potential while neglecting other critical impact categories such as human toxicity, ecotoxicity, water consumption, and resource depletion [6].

Temporal Dynamics: Conventional static LCAs struggle to account for temporal variations in grid electricity carbon intensity, particularly important for assessing intermittent renewable integration and flexible bioenergy systems [8].

Visualization and Interpretation for Policy Audiences

Effectively communicating LCA results to policymakers remains a significant challenge. While LCA is increasingly used for decision-making, most tools include some type of visualization, though there are currently no clear guidelines and no harmonized way of presenting LCA results [9]. Research shows a great variety in visualization options, with emerging approaches combining different kinds of visualizations within design environments, interactive dashboards, and immersive technologies like virtual reality showing potential for facilitating interpretation [9].

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

LCA Harmonization Protocol for Bioenergy Systems

Based on NREL's harmonization approach, the following experimental protocol enables comparable, policy-relevant LCA for bioenergy technologies [7]:

Literature Review and Meta-Analysis

- Identify and collect published LCA studies for target bioenergy pathways

- Extract key parameters: system boundaries, allocation methods, impact assessment methods

- Document variability in reported results and methodological approaches

Adjustment to Consistent Methods and Assumptions

- Define consistent functional unit (e.g., 1 kWh electricity)

- Harmonize system boundaries to include identical process stages

- Apply consistent allocation procedures for co-products

- Use standardized impact assessment methods (e.g., TRACI, ReCiPe)

Statistical Analysis

- Calculate central tendencies (median values) for GHG emissions

- Quantify variability reduction through harmonization

- Perform sensitivity analysis on key parameters

Consequential LCA Protocol for Policy Assessment

For evaluating specific bioenergy policies or projects, consequential LCA provides a more appropriate methodology [8]:

Goal and Scope Definition

- Define decision context and policy question

- Identify affected processes and market mechanisms

- Determine marginal suppliers through energy system modeling

System Boundary Specification

- Include processes affected by the policy intervention

- Account for market-mediated effects (e.g., indirect land-use change)

- Identify substitution effects and avoided burdens

Inventory Analysis

- Collect data on marginal technologies and affected systems

- Model system expansion to account for co-product displacement

- Quantify emissions from direct and indirect effects

Impact Assessment and Interpretation

- Calculate policy-induced emissions changes

- Evaluate trade-offs across impact categories

- Assess uncertainty in marginal data and market responses

Table: Key Research Resources for Bioenergy LCA and Policy Integration

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GREET Model | Provides standardized life cycle inventory data for energy systems | Calculating emissions factors for bioenergy pathways [5] |

| GLEAM (Greenhouse Gas Life Cycle Emissions Assessment Model) | Rapidly predicts life cycle GHG emissions from future electricity scenarios | Scenario analysis for policy planning [7] |

| EnergyPLAN Integration | Models hourly energy system operation with high temporal resolution | Consequential LCA with accurate marginal emissions [8] |

| TRACI and ReCiPe Methods | Standardized impact assessment methods covering multiple environmental categories | Comprehensive environmental footprint beyond carbon [6] |

| Contrast Checker Tools | Ensures accessibility of data visualization outputs | Creating policy-friendly visualizations that meet WCAG standards [10] |

LCA Protocol for Policy Decision Support

The integration of Life Cycle Assessment into GHG targets and renewable energy directives represents a critical evolution in environmental policy implementation. For bioenergy researchers and scientists, understanding this intersection is no longer optional—it is fundamental to producing relevant, actionable science that informs the transition to sustainable energy systems. The methodological frameworks and experimental protocols outlined in this technical guide provide a foundation for conducting policy-relevant LCA research that addresses the complex challenges of bioenergy systems in a carbon-constrained world.

As policy frameworks continue to evolve toward more comprehensive accounting that includes Scope 3 emissions and system-wide impacts, the role of LCA will only grow in importance. The researchers who master both the technical aspects of LCA methodology and its policy applications will be best positioned to contribute meaningfully to the development of effective, scientifically-grounded climate strategies that leverage bioenergy's potential while avoiding unintended environmental consequences.

Life cycle assessment (LCA) for bioenergy systems faces significant challenges that cluster around credibility, transparency, and complexity. These interconnected challenges stem from methodological inconsistencies, incomplete impact assessments, and inadequate handling of bioenergy's multifaceted nature. Current LCA practices often suffer from inconsistent system boundaries, incomparable functional units, and a narrow focus on greenhouse gas emissions that obscures critical trade-offs in environmental performance. Furthermore, the integration of social dimensions and biodiversity impacts remains underdeveloped, while circular economy principles are often referenced without operational clarity. This technical guide diagnoses these methodological shortcomings and provides researchers with structured frameworks, standardized protocols, and visualization tools to enhance the rigor, reproducibility, and policy relevance of bioenergy LCA studies. Addressing these challenges is paramount for generating credible sustainability assessments that can guide the transition to carbon-neutral energy systems.

Life cycle assessment serves as a critical policymaking instrument for evaluating the environmental implications of bioenergy systems, which are projected to constitute more than 20% of global primary energy in climate mitigation pathways [11]. The credibility of these assessments directly influences investment decisions, policy design, and the strategic direction of bioenergy research and development. However, the application of LCA to bioenergy systems presents unique methodological hurdles due to the diversity of feedstocks (from food crops to algae), conversion technologies (from combustion to advanced biofuels), and temporal and spatial variations in production systems.

A systematic diagnosis of the literature reveals that methodological inconsistencies are pervasive across studies, complicating comparative analyses and meta-analyses [11] [6]. The push for more comprehensive assessments has exposed fundamental tensions between scientific rigor and practical applicability, particularly as assessments expand beyond greenhouse gas emissions to include biodiversity, social impacts, and circular economy indicators [12] [13]. This guide dissects these challenge clusters and provides actionable solutions for enhancing methodological integrity.

The Credibility Challenge: Methodological Inconsistencies and Limitations

Credibility in bioenergy LCA is undermined by several recurrent methodological flaws that introduce uncertainty and bias into sustainability claims. These flaws persist despite the publication of standardized guidelines such as ISO 14040/44/67.

Critical Deficiencies in Current LCA Practice

Table 1: Key Methodological Deficiencies Undermining LCA Credibility

| Deficiency Category | Manifestation in Bioenergy LCA | Impact on Credibility |

|---|---|---|

| System Boundary Inconsistency | Varying inclusion/exclusion of land use change, fertilizer production, infrastructure, and end-of-life processes | Precludes meaningful comparison between studies; system-level performance misunderstood |

| Functional Unit Variability | Use of diverse units (e.g., 1 MJ fuel, 1 km distance traveled, 1 hectare of land) | Results become incomparable across studies; conclusions highly dependent on unit selection |

| Multifunctionality Allocation | Inconsistent application of allocation methods (partitional, substitution, system expansion) for co-products | Significant variation in environmental impact assignment; arbitrary burden sharing |

| Impact Category Narrowness | Overemphasis on global warming potential (GWP) with neglect of other categories like water use, ecotoxicity, and biodiversity | Optimizes for single indicators while creating unintended consequences in other environmental domains |

| Uncertainty Analysis Omission | Few studies incorporate systematic uncertainty, sensitivity, or scenario analysis | Results presented as deterministic; robustness of conclusions unknown |

Quantitative Manifestations of Methodological Inconsistency

The empirical evidence for these credibility challenges is substantial. A critical review of 233 LCA studies across biomass combustion, biopower, and all four generations of biofuels found that inconsistency in system boundary definitions was the most prevalent methodological shortcoming [11]. This was particularly evident in assessments of first-generation biofuels, where studies considering fertilizer use, irrigation demands, and process emissions showed significantly different environmental profiles than those omitting these elements.

The incomparability of results due to various functional unit definitions creates substantial variability in reported carbon intensities. For instance, biofuels assessed per unit of energy versus per unit of agricultural land can suggest opposite conclusions about efficiency and sustainability [11]. Furthermore, the incomprehensiveness of impact categories means that critical trade-offs remain unquantified. While numerous studies focus on GWP, acidification potential, and eutrophication potential, they frequently neglect broader environmental impacts such as ozone depletion, abiotic resource depletion, human toxicity, and water consumption [6].

The Transparency Challenge: Modeling Decisions and Data Reporting

Transparency in LCA requires clear documentation of all methodological choices, data sources, and value judgments that influence results. In bioenergy LCA, opaque reporting practices hinder verification, reproducibility, and informed decision-making.

Modeling Decision Documentation

Critical modeling decisions often lack sufficient justification in published studies. These include:

- Timeframe considerations: The handling of temporal aspects, particularly for carbon debt in forest bioenergy and time-dependent climate impacts, is frequently underspecified [6].

- Geographical specificity: LCAs often fail to acknowledge how regional variations in feedstock production, soil types, climate conditions, and energy grids influence results [11].

- Technological representativeness: Many studies assess laboratory-scale or pilot technologies as if they were commercially deployed, overstating near-term potential [11].

Data Quality and Availability

Transparency is compromised when studies rely on proprietary data, outdated inventories, or non-representative secondary data. The lack of region-specific emission factors for agricultural inputs and soil carbon fluxes introduces significant uncertainty [6]. Furthermore, the underdeveloped state of social life cycle inventory data creates a structural barrier to comprehensive sustainability assessments [13].

The Complexity Challenge: Expanding Scope and Multidimensionality

Bioenergy LCA must contend with inherent complexities arising from technological diversity, spatial and temporal variations, and expanding assessment boundaries to include circular economy principles and social dimensions.

Technological and Feedstock Diversity

The bioenergy landscape encompasses a vast portfolio of technologies at different maturity stages:

- First-generation biofuels from food crops (e.g., corn, wheat) raise concerns about food-fuel competition and land use change [11].

- Second-generation biofuels from lignocellulosic biomass (herbaceous and wood plants, agricultural and forestry residues) present different sustainability trade-offs [11].

- Third and fourth-generation systems (algae, genetically modified algae) offer potential but face scalability challenges and uncertain environmental profiles [11].

Each technology pathway requires customized assessment approaches while maintaining methodological consistency for comparability.

Spatial and Temporal Dynamics

The environmental impacts of bioenergy systems are highly dependent on spatial context, including:

- Regional differences in agricultural practices, soil carbon stocks, and climate

- Variations in energy grids that influence conversion process emissions

- Location-specific biodiversity values and water stress conditions

Temporal considerations are equally critical, particularly regarding carbon neutrality assumptions, soil carbon flux dynamics, and technological learning curves [11].

Expanding Assessment Boundaries

Modern LCA must integrate traditionally neglected dimensions to provide comprehensive sustainability assessments:

Biodiversity Impact Assessment Growing awareness of the biodiversity crisis has prompted development of quantitative assessment methods, though these face methodological hurdles [12]. The absence of a universal biodiversity indicator should not justify exclusion of biodiversity assessments from LCA [12]. Promising approaches include:

- Developing adequate biodiversity indicators that reflect important ecological features

- Integrating remote sensing methodologies for life cycle inventory data

- Applying quantitative tools to understand trade-offs across biomass supply chains

Social Life Cycle Assessment Social dimensions remain the least analyzed pillar of bioenergy sustainability [13]. A systematic review found only 17 of 30 social impact studies explicitly utilized S-LCA methodologies [13]. Common limitations include:

- Misclassification of non-social metrics as social indicators

- Limited stakeholder participation in assessment processes

- Overreliance on employment as the primary social indicator due to its quantifiability

Circular Economy Integration While circular economy principles are frequently referenced, their operationalization in LCA remains challenging [6]. Most studies lack structured categorization of environmental impacts aligned with circular economy objectives and fail to establish measurable links between impact categories and circularity pillars like resource recovery and system resilience [6].

Experimental Protocols and Standardized Methodologies

To address the credibility, transparency, and complexity challenges, researchers should adopt standardized experimental protocols for bioenergy LCA. The following methodologies provide structured approaches for critical assessment components.

Protocol for Comprehensive System Boundary Definition

Objective: Establish consistent, justified system boundaries that enable comparable assessments across bioenergy pathways.

Methodology:

- Apply a tiered boundary framework:

- Tier 1 (Minimum): Cradle-to-gate analysis including feedstock production, transportation, and conversion

- Tier 2 (Comprehensive): Cradle-to-grave including distribution, use phase, and end-of-life

- Tier 3 (Economy-wide): Consequential assessment including market-mediated effects

Mandatory inclusion criteria:

- All direct energy and material inputs

- Land use and land use change emissions

- Process emissions from conversion facilities

- Infrastructure for feedstock production and processing

- Transportation between all major lifecycle stages

Documentation requirements:

- Justification for all excluded processes

- Sensitivity analysis for boundary decisions

- Transparent accounting of co-product allocation

Protocol for Biodiversity Impact Assessment

Objective: Quantify biodiversity impacts across bioenergy supply chains using standardized indicators.

Methodology:

- Indicator selection:

- Species richness (number of species per unit area)

- Mean species abundance relative to reference ecosystem

- Threatening processes impact index

Spatial explicit assessment:

- Georeference all land use activities

- Apply characterization factors based on ecosystem type and region

- Differentiate between management practices (intensive vs. extensive)

Implementation workflow:

Biodiversity Assessment Workflow

Protocol for Social Life Cycle Assessment

Objective: Integrate social indicators into bioenergy LCA using stakeholder-informed approaches.

Methodology:

- Stakeholder categorization:

- Workers (throughout supply chain)

- Local communities

- Consumers

- Value chain actors

Indicator measurement:

- Conduct stakeholder surveys for subjective indicators

- Collect quantitative data on employment, wages, injuries

- Assess community impacts through case studies

Impact assessment framework:

- Apply social hotspot database methodology

- Conduct context-specific verification

- Report positive and negative impacts separately

Visualization of Bioenergy LCA Systems

Effective visualization clarifies complex relationships in bioenergy LCA systems. The following diagrams map key methodological approaches and system components.

Integrated Sustainability Assessment Framework

Multi-Criteria Assessment Integration

Bioenergy LCA System Components

Bioenergy System Life Cycle Stages

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Methodological Tools for Robust Bioenergy LCA

| Tool Category | Specific Tool/Approach | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software | openLCA | Open-source platform for modeling complex bioenergy systems with transparent supply chain visualization [14] |

| Impact Assessment | ReCiPe, TRACI | Comprehensive methodology covering multiple environmental impact categories at midpoint and endpoint levels [6] |

| Allocation Methods | System expansion, Partitional allocation, Substitution | Address multifunctionality in bioenergy systems; system expansion generally preferred for avoiding arbitrary partitioning [11] |

| Uncertainty Analysis | Monte Carlo simulation, Scenario analysis, Sensitivity analysis | Quantify uncertainty in LCA results and identify key parameters influencing outcomes [11] |

| Spatial Modeling | GIS integration, Geographically-specific inventory data | Incorporate regional variations in feedstock production, soil carbon, and environmental impacts [11] |

| Social Indicators | S-LCA guidelines, Stakeholder engagement protocols | Assess social impacts across worker, community, and consumer stakeholder groups [13] |

| Biodiversity Metrics | Species richness, Mean species abundance, Threatening processes index | Quantify biodiversity impacts of land use and management practices in bioenergy systems [12] |

Addressing the interconnected challenges of credibility, transparency, and complexity in bioenergy LCA requires concerted methodological advancement. The frameworks, protocols, and tools presented in this guide provide actionable pathways for researchers to enhance their assessment practices. Key priorities include adopting consistent system boundaries, expanding impact assessment beyond greenhouse gases, rigorously addressing uncertainty, and integrating social and biodiversity dimensions through standardized methodologies.

Future research should focus on developing region-specific life cycle inventory data, advancing dynamic modeling approaches for temporal effects, and creating integrated assessment frameworks that seamlessly combine environmental, economic, and social dimensions. The 2025 ARENA LCA Guidelines represent a step forward in standardizing practice, but widespread adoption of such frameworks across the research community is essential [4]. Only through such comprehensive and methodologically rigorous approaches can LCA fulfill its potential as a reliable decision-support tool for navigating the transition to sustainable bioenergy systems.

The Evolution from Retrospective to Forward-Looking Policy Tool

Life cycle assessment (LCA) has undergone a fundamental transformation in its role within environmental policy and bioenergy systems research. Originally developed as a retrospective analysis tool for quantifying environmental impacts of existing products, LCA has evolved into a critical forward-looking instrument for anticipating consequences of policy decisions and emerging technologies [15]. This paradigm shift represents a response to the complex demands of bioenergy governance, where policymakers require robust methods to project potential sustainability outcomes of different technology pathways and policy frameworks [16]. The transition from analyzing "what is" to projecting "what could be" places LCA at the center of sustainable bioenergy development and climate policy implementation.

This evolution has been particularly driven by the bioenergy sector's need to assess complex, system-level questions about greenhouse gas balances, land use change, and resource competition [15] [11]. As bioenergy gained prominence in climate mitigation strategies, traditional attributional LCA (aLCA) proved insufficient for addressing policy-relevant questions about market-mediated effects and indirect consequences [16]. This limitation stimulated methodological advances toward consequential LCA (cLCA) and prospective approaches that integrate future-oriented modeling, with bioenergy serving as a pioneering testbed for these developments [15].

Historical Trajectory of LCA Methodology

Phases of LCA Development

The development of LCA methodology has passed through three distinct phases characterized by different drivers and applications [15]. The table below summarizes this historical trajectory:

Table 1: Historical Evolution of LCA Methodology

| Time Period | Primary Driver | Scope & Methodology | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s-1980s | Corporate resource management | Single-issue, energy-focused analyses | Internal company decision-making, resource efficiency |

| 1990s-early 2000s | Rise of global environmental issues | Standardized, multi-impact frameworks (SETAC, ISO) | Eco-labeling, packaging legislation, integrated product policy |

| Mid-2000s-present | Climate policy and bioenergy targets | Consequential, prospective approaches | Bioenergy policy, carbon accounting, technology foresight |

LCA emerged in the late 1960s as a tool developed and used by companies for resource management, predominantly focused on single issues such as waste or energy [15]. These early analyses, often called Resource and Environmental Profile Analyses (REPAs), were frequently conducted as internal company studies and rarely published due to commercial sensitivities [15]. The methodology began to formalize in the 1990s with the development of Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) standards, later adopted and amended into the ISO 14040 series [15]. This period marked LCA's transition from an internal corporate tool to one with regulatory applications, though it remained primarily retrospective in orientation.

The mid-2000s witnessed a significant turning point with the rise of bioenergy as a climate mitigation strategy [15]. Complex policy questions surrounding biofuels—particularly the "food versus fuel" debate and concerns about indirect land use change—demanded a more expansive analytical approach that could project potential consequences of policy decisions [15] [16]. This period saw the emergence of consequential LCA as a distinct methodology designed to address these broader questions, representing a fundamental shift from LCA's original purpose.

The Attributional-Consequential Divide

The distinction between attributional and consequential LCA represents a central conceptual division in LCA methodology. Attributional LCA (aLCA) employs static, linear models to describe the environmentally relevant physical flows to and from a life cycle and its subsystems, typically using historical data [15]. It addresses "what is" questions about existing systems. In contrast, consequential LCA (cLCA) models how environmentally relevant flows change in response to potential decisions, incorporating economic concepts such as marginal data and market-mediated effects [15] [16].

This methodological divergence has created significant challenges for the LCA community. The aLCA and cLCA communities often employ different terminology and conceptual frameworks, creating communication barriers [15]. Whereas aLCA operates at a micro-scale with project-specific boundaries, cLCA necessarily works at a macro-scale with highly aggregated global economic models [15]. Bridging these methodological perspectives remains non-trivial, with few examples of integrated a/cLCA teams and significant differences in how each community conceptualizes and addresses uncertainty [15].

The following diagram illustrates the key methodological evolution and distinguishing characteristics of these LCA approaches:

Methodological Framework for Forward-Looking LCA

Core Components of Prospective LCA

Forward-looking LCA methodologies incorporate several innovative components that differentiate them from traditional approaches. Prospective LCA aims to assess the potential environmental impacts of emerging technologies or policy decisions by integrating future scenarios, dynamic modeling, and technology forecasting [17]. This approach is particularly valuable for bioenergy systems, where technologies and their contexts may evolve significantly between development and deployment.

A key methodological innovation is the integration of qualitative scenarios with quantitative LCA [17]. This involves transforming narrative descriptions of potential future developments into quantitative data that can be incorporated into life cycle inventory (LCI) analysis. For example, scenarios describing changes in energy systems, agricultural practices, or climate policies can be operationalized through specific parameter adjustments in background systems [17]. This approach allows technology developers to evaluate the future potential of different bioenergy pathways and assess their environmental impacts under uncertain future developments.

Dynamic LCA represents another important methodological advancement, introducing temporal considerations into impact assessment [18]. Unlike static LCA approaches that use fixed, time-independent characterization factors, dynamic LCA accounts for the timing of emissions and their changing environmental effects over time. This is particularly relevant for bioenergy systems, where carbon sequestration and release may occur over varying timeframes, influencing their climate change mitigation potential [11].

Real-Time LCA Tools and Platforms

The emergence of real-time LCA platforms represents a significant technical advancement in forward-looking assessment. Tools such as FARMBENV demonstrate how dynamic, web-based LCA applications can provide immediate environmental impact assessments using real-time sensor data [19]. These tools integrate static background data from established databases (e.g., Ecoinvent) with dynamic, site-specific inputs from production systems, enabling more accurate and context-sensitive results than conventional tools [19].

For bioenergy systems, specialized calculation tools have been developed to support policy implementation. BioCalc, for instance, extends the capabilities of Brazil's RenovaCalc tool to enable life cycle assessment of solid biofuels within decarbonization frameworks [20]. This tool adopts a cradle-to-grave system boundary and incorporates location-specific emission factors, allowing biofuel producers to quantify carbon intensity and estimate potential carbon credits [20]. Such tools bridge the gap between LCA methodology and practical policy implementation, facilitating the integration of bioenergy into carbon pricing mechanisms.

Table 2: Advanced LCA Tools for Bioenergy Applications

| Tool Name | Primary Application | Key Features | Policy Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| FARMBENV | Agricultural bioenergy systems | Real-time data integration, user-friendly interface, EPD support | Environmental certification, sustainable agriculture policies |

| BioCalc | Solid biofuels in Brazil | Carbon intensity calculation, credit estimation, RenovaBio alignment | Brazilian GHG Emissions Trading System (SBCE) |

| RenovaCalc | Liquid biofuels in Brazil | Carbon accounting, decarbonization certificate issuance | RenovaBio National Biofuels Policy |

Applications in Bioenergy Policy and Research

Bioenergy as a Driver of Methodological Innovation

Bioenergy systems have served as a primary driver for the evolution of LCA from retrospective to forward-looking policy tool [15]. Several factors make bioenergy particularly conducive to this methodological development. First, bioenergy systems create complex interconnections between agricultural and energy systems, generating questions about indirect land use change, resource competition, and market-mediated effects that cannot be adequately addressed through traditional LCA [15] [16]. Second, the rapid expansion of bioenergy policies, including renewable energy targets, carbon pricing mechanisms, and sustainability criteria, created an urgent need for robust assessment methods to guide decision-making [20].

The charged policy environment surrounding biofuels, particularly the "food versus fuel" debate, accelerated methodological innovation by highlighting the limitations of conventional LCA approaches [15]. This controversy revealed that narrow, attributional assessments failed to capture important system-level consequences of bioenergy expansion, stimulating development of more comprehensive consequential approaches [16]. Additionally, the global nature of bioenergy markets, with international trade in feedstocks and finished biofuels, necessitated methodological frameworks capable of addressing transnational effects and leakage [11].

LCA in Bioenergy Policy Frameworks

LCA has become embedded in numerous bioenergy policy frameworks worldwide, reflecting its transition to a forward-looking decision support tool. Major policies incorporating LCA include the EU Renewable Energy Directive, US Renewable Fuel Standard, California's Low Carbon Fuel Standard, and Brazil's RenovaBio program [20] [16]. These policies employ LCA not merely for retrospective compliance assessment but as a prospective mechanism to guide technology development and investment decisions.

The Brazilian RenovaBio program exemplifies the sophisticated application of LCA in bioenergy policy [20]. This policy establishes a carbon intensity benchmarking system for biofuels, with LCA-based calculations forming the basis for decarbonization credits within a regulated market mechanism [20]. By creating economic value for greenhouse gas reduction, the program uses LCA prospectively to incentivize continuous improvement in biofuel production pathways. The development of tools like RenovaCalc (for liquid biofuels) and BioCalc (for solid biofuels) operationalizes this approach by providing standardized methodologies for calculating carbon intensity and estimating credit generation potential [20].

Research Reagents and Experimental Protocols

Essential Methodological Components for Forward-Looking LCA

Implementing forward-looking LCA for bioenergy systems requires specific methodological components that function as "research reagents" in the analytical process. These components enable researchers to address the distinctive challenges of prospective assessment.

Table 3: Essential Methodological Components for Forward-Looking Bioenergy LCA

| Component | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative Scenarios | Provide narrative descriptions of alternative future developments | Socioeconomic scenarios for energy transition pathways [17] |

| Economic Equilibrium Models | Project market-mediated effects of bioenergy expansion | Modeling indirect land use change from biofuel policies [15] |

| Technology Learning Curves | Represent cost and efficiency improvements over time | Forecasting environmental impacts of emerging bioenergy technologies [17] |

| Dynamic Characterization Factors | Incorporate temporal variations in impact assessment | Time-dependent global warming potential for biogenic carbon [11] |

| Real-Time Data Integration Systems | Capture operational data from production systems | Sensor networks for agricultural inputs in bioenergy crop production [19] |

Experimental Protocol: Integrating Qualitative Scenarios into LCA

The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for integrating qualitative scenarios into LCA, based on methodologies described in the literature [17]:

Scenario Selection and Analysis: Identify and analyze qualitative scenarios describing potential future developments relevant to the bioenergy system under study. These may include socioeconomic, technological, environmental, or policy scenarios.

Parameter Identification: Determine the LCI parameters most likely to be influenced by scenario developments. These typically include energy mix, agricultural yields, input efficiencies, and transportation patterns.

Quantification: Establish quantitative values for identified parameters corresponding to each scenario narrative. This may involve literature review, expert elicitation, or modeling exercises.

LCI Adaptation: Modify the background LCI to reflect scenario-specific parameter values. This adapts the entire environment in which the bioenergy technology is assumed to operate.

Impact Assessment: Conduct life cycle impact assessment using the adapted inventories for each scenario.

Robustness Analysis: Compare results across scenarios to identify robust technology options that perform well under different future conditions.

This protocol enables researchers to evaluate how bioenergy technologies might perform under alternative future framework conditions, providing valuable insights for technology development and policy design [17].

Challenges and Future Research Directions

Methodological Limitations and Critical Challenges

Despite significant advances, forward-looking LCA methodologies face several persistent challenges. Uncertainty remains a fundamental concern, with prospective assessments inherently involving greater uncertainty than retrospective analyses [15] [16]. This uncertainty stems from multiple sources, including future technological developments, market responses, policy changes, and environmental variations. Effectively characterizing and communicating this uncertainty is essential for the credible application of forward-looking LCA in policy contexts [16].

Methodological consistency represents another significant challenge. The flexibility permitted within LCA standards, combined with the diversity of approaches to consequential and prospective modeling, can yield substantially different results for similar systems [11] [16]. Inconsistencies in system boundary definitions, functional unit selection, impact assessment methods, and allocation approaches complicate comparisons between studies and undermine policy clarity [11]. For bioenergy systems, specific methodological challenges include handling multifunctionality in biorefineries, accounting for biogenic carbon flows, and addressing indirect land use change [11].

The integration of spatial and temporal dynamics remains technically challenging. Most LCA models employ static, location-independent characterization factors, despite evidence that environmental impacts vary significantly across spatial and temporal dimensions [11]. Developing spatially explicit and dynamic assessment methods is particularly important for bioenergy systems, where feedstock production impacts depend heavily on local conditions and management practices [11].

Emerging Innovations and Future Trajectories

Future developments in forward-looking LCA are likely to focus on several promising innovation areas. The integration of digital technologies, including IoT sensors, digital twins, and artificial intelligence, enables more dynamic and data-rich assessments [19]. These technologies support real-time environmental impact monitoring and more sophisticated modeling of complex system behavior [19].

The expansion of assessment boundaries to encompass broader sustainability considerations represents another important trajectory. While traditional LCA focuses on environmental impacts, there is growing interest in integrating social and economic dimensions through life cycle sustainability assessment (LCSA) [17]. This approach combines environmental LCA with life cycle costing and social LCA, providing a more comprehensive evaluation of bioenergy systems [17].

The development of more sophisticated uncertainty handling methods is crucial for enhancing the credibility of forward-looking LCA. Approaches such as probabilistic modeling, scenario analysis, and robust decision-making provide frameworks for explicitly addressing uncertainty rather than ignoring or minimizing it [15] [17]. These methods acknowledge the inherent unpredictability of future developments while still providing valuable insights for decision-making.

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected challenges and future research priorities for forward-looking LCA:

The evolution of LCA from a retrospective to forward-looking policy tool represents a fundamental methodological transformation with significant implications for bioenergy research and policy. This shift has expanded LCA's scope from describing existing systems to anticipating potential consequences of decisions, enabling more proactive governance of bioenergy development. Methodological innovations such as consequential modeling, scenario integration, and dynamic assessment have enhanced LCA's ability to address complex, system-level questions relevant to bioenergy sustainability.

Despite substantial progress, important methodological challenges remain, particularly regarding uncertainty treatment, methodological consistency, and spatiotemporal dynamics. Future research should focus on developing more sophisticated approaches to these challenges while leveraging emerging digital technologies to enhance assessment capabilities. As bioenergy continues to play a crucial role in climate change mitigation strategies, further refinement of forward-looking LCA methodologies will be essential for guiding policy decisions and technology development toward truly sustainable outcomes.

Attributional vs. Consequential LCA: Choosing the Right Framework for Your Bioenergy System

In life cycle assessment (LCA) for bioenergy systems, the foundational stages of goal and scope definition establish the entire study's rationale, depth, and applicability. This phase dictates the assessment's credibility by explicitly defining the system under investigation and the basis for comparison. Two of the most critical methodological choices at this stage are the selection of the functional unit (FU) and the delineation of the system boundary. These elements are interdependent; the functional unit quantifies the performance of the system, while the system boundary defines which processes are included in the inventory analysis. Inconsistencies in these definitions are a primary source of incomparability between LCA studies, a challenge particularly acute in the complex and diverse field of bioenergy [11]. This guide provides a technical deep-dive into these components, framed within bioenergy research, to empower scientists and engineers in designing rigorous and comparable LCA studies.

Defining the Goal of the LCA Study

The goal of an LCA must be unambiguously stated, as it informs all subsequent methodological decisions. For bioenergy research, this involves specifying the following:

- Intended Application and Audience: Is the study for internal R&D, policymaking, or consumer communication? The audience influences the level of detail and communication strategy [21].

- Decision Context: The study must clarify whether it is an attributional LCA (ALCA), describing the environmentally relevant physical flows for a product system, or a consequential LCA (CLCA), modeling how these flows would change in response to a decision. CLCA is often relevant for policy-oriented bioenergy studies assessing large-scale deployment [11].

- Comparative Assertions: If the results will be used to make comparative claims disclosed to the public, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standards require critical review and heightened methodological rigor.

The Functional Unit (FU) in Bioenergy Systems

The functional unit provides a quantified reference to which all inputs and outputs are normalized, ensuring fair comparisons. An ill-defined FU renders an LCA meaningless.

Core Concepts and Common Challenges

The FU must represent the primary function of the bioenergy system. A critical review of bioenergy LCAs has identified a lack of comparability due to various FU definitions as a major methodological shortcoming [11]. For instance, comparing biofuels on a per-liter basis versus a per-megajoule basis will yield vastly different results for energy and greenhouse gas (GHG) metrics. The former reflects the production volume, while the latter reflects the energy service provided, which is the more common basis for fuel comparison.

Typology of Functional Units for Bioenergy

The table below categorizes common functional units used in bioenergy LCA, their applications, and associated methodological considerations.

Table 1: Common Functional Units in Bioenergy LCA

| Functional Unit Category | Specific Examples | Typical Bioenergy Application | Methodological Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy-Based | 1 MJ of lower heating value (LHV) of fuel; 1 kWh of electricity generated | Biofuels (e.g., biodiesel, bioethanol), biopower | Allows for comparison of energy carriers on an equivalent energy service basis. Critical for assessing energy efficiency and GHG intensity. |

| Mass-Based | 1 kg of dry biomass; 1 kg of produced bio-oil | Feedstock production; intermediate bio-products | Useful for upstream processes (e.g., agriculture, pre-treatment) but insufficient for final energy service comparison. |

| Area-Based | 1 hectare of land per year | Land-use change (LUC) assessments; perennial crop cultivation | Directly links environmental impacts (e.g., biodiversity, nutrient runoff) to land use. Must be used in conjunction with other FUs. |

| Economic-Based | 1 USD of economic value | High-value bio-chemicals; socio-economic LCA | Relevant for cost-benefit analyses and life cycle costing (LCC) but can be volatile due to price fluctuations. |

Experimental Protocol: Selecting and Applying a Functional Unit

- Identify the Primary Function: Clearly state the primary service of the system. For a biodiesel-powered vehicle, the function is "to provide vehicle propulsion," not "to produce biodiesel."

- Quantify the Function: Define a measurable parameter for the function. Following the example, this could be "to drive 1 kilometer."

- Define a Reference Flow: Determine the amount of product(s) needed to deliver the function. This involves accounting for energy densities and efficiencies. For instance, to drive 1 km, a specific vehicle might require 0.08 liters of biodiesel. This 0.08 liters is the reference flow for the 1 km FU.

- Document and Justify: Explicitly document the chosen FU and the rationale for its selection, especially if deviating from standard practice in the field.

Delineating the System Boundary

The system boundary specifies which unit processes are included in the product system. In bioenergy, this is often a cradle-to-grave approach, but the specific inclusions and exclusions vary significantly.

Core Life Cycle Stages

A generic cradle-to-grave system for bioenergy encompasses several stages, as illustrated in the workflow below.

Diagram 1: Bioenergy LCA System Workflow

Critical Review of Boundary Dilemmas in Bioenergy

A critical review of bioenergy LCAs highlights inconsistency of system boundary definitions as a pervasive issue [11]. Key controversies include:

- Land Use Change (LUC): The inclusion of direct and indirect LUC is a major differentiator. First-generation biofuels from food crops often show significant GHG penalties when LUC is accounted for, a factor sometimes omitted in earlier studies [11].