From Food Crops to Advanced Feedstocks: The Evolution of Modern Bioenergy

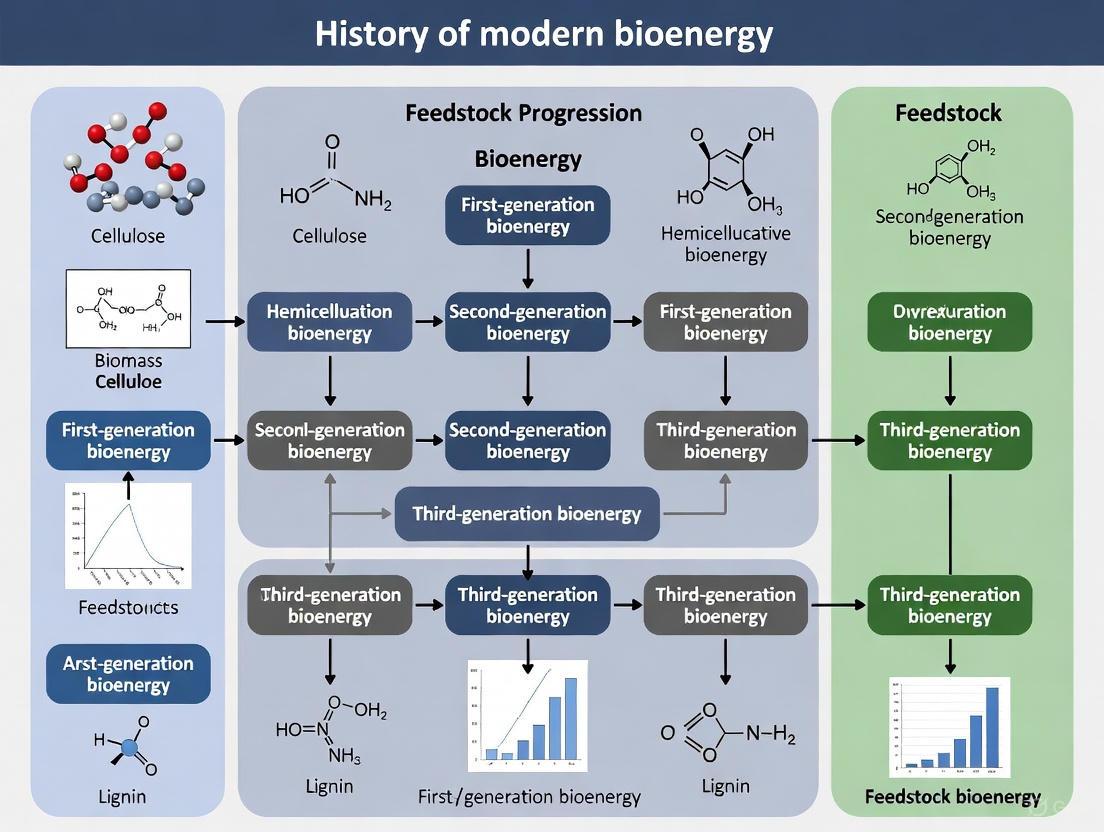

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the history and progression of modern bioenergy, charting the transition from first-generation food-based feedstocks to advanced lignocellulosic and waste resources.

From Food Crops to Advanced Feedstocks: The Evolution of Modern Bioenergy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the history and progression of modern bioenergy, charting the transition from first-generation food-based feedstocks to advanced lignocellulosic and waste resources. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it explores the foundational concepts, methodological advancements in conversion technologies, key challenges in scaling production, and the environmental and economic validation of bioenergy systems. Synthesizing the latest research and market trends up to 2025, the review offers a detailed perspective on the technological innovations and policy frameworks shaping the sustainable future of bioenergy within the global renewable energy landscape.

The Generational Shift: Defining Bioenergy and Feedstock Evolution

What is Bioenergy? Core Definitions and Significance in the Renewable Landscape

Bioenergy is a form of renewable energy derived from biological sources, known as biomass, which includes organic materials such as plants, agricultural residues, and animal waste [1] [2]. This energy source is distinct from fossil fuels, as the biomass used consists of recently living organisms and does not include fossilized materials embedded in geological formations [1]. The fundamental principle of bioenergy harnesses the natural process of photosynthesis, where plants capture solar energy and convert it into chemical energy, storing it in their structures [3]. This stored energy can then be released through various conversion processes to generate heat, electricity, or liquid fuels, positioning bioenergy as a potentially carbon-neutral alternative to fossil fuels when managed sustainably [3] [4].

The historical context of bioenergy reveals a long-standing human reliance on biological energy sources, with the combustion of wood for heat being one of the earliest forms of energy utilized by human civilizations [4]. In the modern energy landscape, bioenergy has evolved into a sophisticated component of the renewable energy mix, supported by technological advancements and policy frameworks aimed at decarbonizing energy systems [5]. According to the International Energy Agency's Net Zero by 2050 scenario, modern bioenergy's share in the global energy mix is expected to increase significantly, from 6.6% in 2020 to 13.1% in 2030 and 18.7% in 2050, highlighting its growing importance in climate change mitigation strategies [1].

Core Bioenergy Conversion Pathways and Technologies

The transformation of raw biomass into usable energy occurs through several distinct technological pathways, each with specific processes and output characteristics. These conversion methods can be broadly categorized into thermochemical, biochemical, and chemical processes, with each suited to different feedstock types and end-use applications [1].

Thermochemical Conversion Processes

Thermochemical conversion utilizes heat as the primary mechanism to transform biomass into more practical energy forms through controlled chemical reactions [1]. The specific process and output depend largely on temperature and oxygen availability:

Combustion: This is the most straightforward method, involving the direct burning of solid biomass such as wood logs, wood chips, or agricultural residues to produce heat [1] [4]. This heat can be used directly for warmth in residential or industrial settings, or to generate steam that drives turbines for electricity generation [4]. Biomass heating systems range from fully automated pellet-fired systems to combined heat and power (CHP) configurations that improve overall efficiency [1].

Gasification: This process converts biomass into a combustible gas mixture known as syngas (primarily carbon monoxide and hydrogen) by heating the feedstock in a controlled, oxygen-deficient environment at high temperatures (typically above 700°C) [1] [4]. The resulting syngas can be used to generate electricity in gas turbines, as a source of process heat, or as a building block for chemical synthesis [4]. Modern gasification systems are increasingly integrated with combined cycle power generation for enhanced efficiency.

Pyrolysis: In this process, biomass is thermally decomposed in the complete absence of oxygen at temperatures typically between 400°C and 600°C [1] [4]. The primary output is bio-oil, a liquid fuel that can be further refined, along with solid charcoal (biochar) and syngas as by-products [4]. Fast pyrolysis techniques maximize liquid yield and are the subject of ongoing research and development for commercial applications.

Torrefaction: Sometimes described as "mild pyrolysis," this process heats biomass to 200-300°C in an inert atmosphere, effectively roasting it to remove moisture and volatile components [5]. The resulting material has higher energy density, improved grindability, and better storage characteristics, making it more suitable for co-firing with coal in existing power plants [5].

Biochemical Conversion Processes

Biochemical conversion harnesses natural biological processes, typically employing microorganisms or enzymes to break down biomass into useful energy carriers [1]:

Anaerobic Digestion: This process utilizes microbial communities to decompose organic matter—such as animal manure, sewage sludge, food waste, and energy crops—in the absence of oxygen [1] [3]. The primary output is biogas, a mixture of methane (50-75%) and carbon dioxide that can be combusted to generate heat and electricity or upgraded to renewable natural gas (biomethane) for injection into gas grids or use as vehicle fuel [3]. The residual digestate serves as a valuable fertilizer, creating a circular nutrient system.

Fermentation: This well-established technology uses yeast strains to convert sugars from biomass feedstocks into ethanol through metabolic processes [1] [3]. Traditional fermentation employs food crops high in sugar (sugarcane) or starch (corn), which must first be hydrolyzed to simple sugars [3]. Advanced fermentation technologies are being developed to process lignocellulosic biomass through enzymatic hydrolysis, enabling the production of so-called second-generation biofuels that avoid competition with food supplies [1].

Chemical Conversion Processes

Chemical conversion pathways primarily focus on producing liquid transportation fuels through catalytic reactions:

Transesterification: This process converts vegetable oils, animal fats, or waste cooking oils into biodiesel (fatty acid methyl esters) through reaction with an alcohol (typically methanol) in the presence of a catalyst [3] [6]. The resulting biodiesel can be used in conventional diesel engines, either in pure form (B100) or blended with petroleum diesel at various ratios (e.g., B20 contains 20% biodiesel) [6].

Hydrotreating: This refinery-based process uses hydrogen under high pressure and temperature to remove oxygen from triglycerides, producing renewable diesel that is chemically identical to petroleum diesel [6]. Unlike biodiesel, renewable diesel can be used unblended in existing diesel engines and transported through conventional fuel infrastructure, including pipelines [6].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Bioenergy Conversion Technologies

| Conversion Process | Primary Technology | Key Feedstocks | Main Output(s) | Technology Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermochemical | Combustion | Wood chips, agricultural residues, solid waste | Heat, Electricity | Commercial |

| Gasification | Wood, energy crops, organic waste | Syngas, Electricity, Heat | Demonstration/Commercial | |

| Pyrolysis | Wood, agricultural residues | Bio-oil, Biochar, Syngas | Pilot/Demonstration | |

| Biochemical | Anaerobic Digestion | Manure, food waste, sewage sludge | Biogas, Digestate | Commercial |

| Fermentation | Sugarcane, corn, wheat, lignocellulosic biomass | Ethanol, COâ‚‚ | Commercial (1st gen)/Demonstration (2nd gen) | |

| Chemical | Transesterification | Vegetable oils, animal fats, used cooking oil | Biodiesel (FAME), Glycerin | Commercial |

| Hydrotreating | Vegetable oils, animal fats, used cooking oil | Renewable Diesel | Commercial |

Feedstock Progression and Evolution

The development of bioenergy has been characterized by a progressive evolution in feedstock sources, commonly categorized into generations that reflect technological advancement and sustainability considerations [1] [6].

First-Generation Feedstocks

First-generation feedstocks consist primarily of food crops grown on arable land, including sugar-rich plants like sugarcane and sugar beet, starch-rich grains like corn and wheat, and oil-bearing crops like rapeseed, soybeans, and oil palm [1] [6]. These conventional biofuels benefit from established agricultural infrastructure and conversion technologies, leading to widespread commercialization, particularly in bioethanol production in the United States and Brazil, and biodiesel in Europe [1] [6]. In the United States, approximately 35% of domestic corn disappearance was used for ethanol production in the 2025 crop year, while almost 49% of soybean oil was directed toward biomass-based diesel production [6].

However, first-generation feedstocks face significant limitations, including competition with food production, potential impacts on food prices, and relatively modest greenhouse gas reduction benefits when indirect land-use changes are considered [1] [4]. The cultivation of these crops typically requires high inputs of water, fertilizers, and pesticides, creating additional environmental concerns [4].

Second-Generation Feedstocks

Second-generation, or "advanced" biofuels, utilize non-food biomass resources, including [1]:

- Agricultural residues: Corn stover, wheat straw, sugarcane bagasse

- Forestry residues: Wood chips, sawdust, thinning materials

- Dedicated energy crops: Fast-growing perennial grasses (switchgrass, miscanthus) and short-rotation woody crops (willow, poplar)

- Industrial and municipal waste: Organic fractions of municipal solid waste, waste wood, food processing residues

These feedstocks offer significant advantages by avoiding direct competition with food production, potentially utilizing marginal lands unsuitable for agriculture, and providing waste management solutions [1] [4]. The technical challenge lies in overcoming the recalcitrance of lignocellulosic materials—the natural resistance of plant cell walls to decomposition—which requires more complex pretreatment and conversion processes than first-generation alternatives [3].

Third and fourth-generation feedstocks represent the frontier of bioenergy research and development:

- Algae: Both microalgae and macroalgae offer high growth rates, high oil yield per unit area, and the ability to grow on non-arable land using saline or wastewater [3] [4]. Algal systems can potentially capture carbon dioxide from industrial emissions, though production costs remain challenging [4].

- Novel biological systems: Research is exploring genetically modified energy crops with reduced recalcitrance, enhanced biomass yield, or altered composition to improve conversion efficiency [3].

- Hybrid systems: Integrated approaches that combine biomass production with other functions, such as agrivoltaics (combining agriculture with solar power generation) or ecological restoration, represent promising directions for sustainable bioenergy development.

Table 2: Progression of Bioenergy Feedstock Generations

| Feedstock Generation | Example Feedstocks | Primary Advantages | Key Challenges | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Generation | Corn, sugarcane, soybeans, oil palm | Established supply chains, proven conversion technologies, economic viability | Food vs. fuel competition, limited GHG reduction potential, agricultural input requirements | Commercial |

| Second-Generation | Agricultural residues, forestry waste, energy crops (switchgrass, miscanthus) | Non-food biomass, higher GHG reduction potential, utilization of waste streams | Recalcitrance of lignocellulosic material, complex pretreatment requirements, logistics of dispersed resources | Early Commercial/Demonstration |

| Third-Generation | Microalgae, macroalgae | High growth rates and yield, minimal land requirements, utilization of marginal water sources | High production costs, energy-intensive processing, scaling challenges | R&D/Pilot |

| Fourth-Generation | Genetically optimized energy crops, integrated bioenergy systems with carbon capture | Enhanced efficiency, carbon-negative potential, multifunctional systems | Regulatory hurdles, public acceptance, technological complexity | Research Phase |

Experimental Framework for Biomass Analysis

For researchers investigating novel feedstocks and conversion processes, standardized experimental protocols are essential for generating comparable and reproducible results. The following methodologies provide a framework for characterizing biomass and evaluating conversion efficiency.

Biomass Compositional Analysis

Objective: To quantitatively determine the major structural components of lignocellulosic biomass. Materials and Reagents:

- Dried, milled biomass sample (particle size <1 mm)

- Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF) solution for cell wall fractionation

- Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF) solution for lignin and cellulose separation

- 72% Sulfuric acid for lignin determination

- Ethanol for solvent extraction

- Anthrone reagent for carbohydrate quantification

- Nitrogen analyzer for protein content

- Calorimeter for heating value determination

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Oven-dry biomass at 105°C until constant weight is achieved. Mill to pass through a 1-mm screen and store in a desiccator.

- Extractives Removal: Use ethanol in a Soxhlet apparatus for 6 hours to remove non-structural compounds.

- Structural Carbohydrate Analysis: a. Perform sequential fiber analysis using NDF and ADF solutions to isolate hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin fractions. b. Quantify cellulose as the difference between ADF and acid-insoluble lignin. c. Determine hemicellulose as the difference between NDF and ADF.

- Lignin Quantification: a. Treat the ADF residue with 72% sulfuric acid at 20°C for 3 hours. b. Dilute to 3% acid concentration and reflux for 4 hours. c. Filter and weigh the acid-insoluble (Klason) lignin. d. Measure acid-soluble lignin by UV spectrophotometry at 205 nm.

- Calorific Value Determination: Use an isoperibol calorimeter with benzoic acid calibration according to ASTM D5865 standards.

Enzymatic Hydrolysis Saccharification Assay

Objective: To evaluate the sugar release potential of pretreated biomass under standardized enzymatic conditions. Materials and Reagents:

- Pretreated biomass sample (at standardized solids loading)

- Commercial cellulase cocktail (e.g., CTec3, HTec3)

- Sodium citrate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.8)

- Sodium azide (0.03% w/v) as antimicrobial agent

- Dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) reagent for sugar quantification

- High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system with refractive index detector

- Shaking incubator with temperature control

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare reactions containing the equivalent of 1.0% (w/v) glucan in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks, using sodium citrate buffer.

- Enzyme Loading: Add commercial cellulase enzymes at standardized loading (e.g., 15-20 mg protein/g glucan).

- Hydrolysis Conditions: Incubate at 50°C with continuous agitation at 150 rpm for 72 hours.

- Sampling: Withdraw 1 mL aliquots at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 hours for sugar analysis.

- Sugar Quantification: a. Centrifuge samples at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes to remove solids. b. Analyze supernatant using DNS method for total reducing sugars. c. Perform detailed sugar profile analysis by HPLC using an aminex HPX-87P column with water as mobile phase at 0.6 mL/min and 85°C.

- Data Analysis: Calculate sugar yields as percentage of theoretical maximum based on initial biomass composition.

Anaerobic Digestion Biogas Potential Assay

Objective: To determine the biochemical methane potential (BMP) of organic feedstocks. Materials and Reagents:

- Inoculum from an active anaerobic digester

- Substrate sample (characterized for total solids, volatile solids, and elemental composition)

- Anaerobic serum bottles (100 mL to 500 mL capacity)

- Oxidation-reduction potential indicator (resazurin)

- Macro- and micronutrient solution according to standard protocols

- Gas chromatograph with thermal conductivity detector

- Water displacement system or automated gas measurement apparatus

Procedure:

- Bottle Preparation: Add inoculum and substrate to serum bottles at recommended inoculum-to-substrate ratio (typically 2:1 on volatile solids basis).

- Control Setup: Include controls with inoculum only (blank) and reference substrate with known BMP (positive control).

- Anaerobic Conditions: Flush headspace with nitrogen gas (Nâ‚‚) for 2 minutes to establish anaerobic conditions.

- Incubation: Place bottles in temperature-controlled environment (35±2°C or 55±2°C for mesophilic or thermophilic conditions, respectively) with continuous gentle mixing.

- Gas Monitoring: Measure biogas production daily by pressure build-up using manometers or water displacement systems.

- Gas Composition: Analyze biogas composition (CHâ‚„, COâ‚‚, Hâ‚‚S) regularly by gas chromatography.

- Data Analysis: Calculate cumulative methane production and normalize to volatile solids added after subtracting blank values. Report as mL CHâ‚„/g VS added.

Research Reagent Solutions for Bioenergy Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biomass Conversion Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulase Enzymes | Hydrolyze cellulose to glucose | CTec3, HTec3 (Novozymes); Accellerase (DuPont); typically 100-150 FPU/mL |

| Hemicellulase Enzymes | Hydrolyze hemicellulose to pentose sugars | Xylanase, β-xylosidase, arabinofuranosidase activities |

| Lignin Modifying Enzymes | Modify or degrade lignin to reduce recalcitrance | Laccases, peroxidases, lignin peroxidases from fungal sources |

| Anaerobic Inoculum | Microbial consortium for biogas production | Active digestate from commercial anaerobic digesters, adapted to specific substrates |

| Antimicrobial Agents | Prevent microbial contamination in hydrolysis assays | Sodium azide (0.02-0.05%), cycloheximide (for fungal inhibition), tetracycline (for bacterial inhibition) |

| Detergent Solutions | Fiber analysis for biomass composition | Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF), Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF) solutions |

| Analytical Standards | Quantification of reaction products | Cellobiose, glucose, xylose, arabinose, acetic acid, furfural, HMF, phenolic compounds |

| Buffering Systems | pH control in enzymatic and microbial assays | Citrate buffer (pH 4.8-5.0), phosphate buffer (pH 6.5-7.5), bicarbonate buffer (anaerobic conditions) |

Quantitative Market Data and Future Outlook

The global bioenergy market has demonstrated consistent growth, driven by decarbonization policies, technological advancements, and increasing energy security concerns. The biomass power generation market was valued at US$90.8 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach US$116.6 billion by 2030, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.3% [5]. This growth trajectory underscores the increasing integration of bioenergy into global energy systems.

Regional analysis reveals distinct patterns of bioenergy adoption and development. Europe, North America, and Asia-Pacific represent the strongest markets, implementing favorable policies including feed-in tariffs, renewable energy credits, and carbon tax exemptions to support biomass adoption [5]. The United States market was valued at $6.6 billion in 2024, while China represents the most rapidly expanding market, forecast to grow at a 5.4% CAGR to reach $25.7 billion by 2030 [5].

Feedstock utilization trends show increasing diversification, with the forest waste segment expected to reach US$51 billion by 2030 at a 3.7% CAGR, while the agricultural waste segment is projected to grow at 4.7% CAGR over the same period [5]. This reflects efforts to utilize waste streams and reduce competition with food production, though first-generation feedstocks continue to dominate certain sectors, particularly transportation biofuels.

Technological advancements are enhancing the efficiency and economic viability of bioenergy systems. Key innovations include advanced gasification processes, torrefaction technologies that enhance biomass energy density, and the integration of carbon capture and storage (CCS) with bioenergy to create carbon-negative systems [5]. The latter approach, known as Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), represents a potentially significant carbon dioxide removal technology, though deployment remains limited with only three large-scale projects operating globally as of 2024 [1].

The expanding use of waste-to-energy (WTE) technologies represents another significant trend, addressing dual challenges of waste management and renewable energy generation [5]. Municipal solid waste generation worldwide is projected to increase from approximately 2.2 billion metric tons in 2020 to 3.5 billion metric tons by 2050, creating both challenges and opportunities for bioenergy applications [5].

Significance in the Renewable Energy Landscape

Bioenergy occupies a unique position within the renewable energy portfolio due to its distinctive characteristics and applications. Unlike intermittent renewable sources like solar and wind power, bioenergy can provide dispatchable electricity, making it a valuable resource for grid stability and base-load power generation [5]. Furthermore, bioenergy represents the primary renewable alternative for difficult-to-decarbonize sectors such as heavy transportation, aviation, and industrial heat processes that require high-energy-density fuels [1] [6].

The surface power production density of bioenergy systems is typically lower than other renewable technologies, with average lifecycle values of approximately 0.30 W/m² for biomass, compared to 1 W/m² for wind, 3 W/m² for hydro, and 5 W/m² for solar power production [1]. This land use requirement represents a significant constraint and underscores the importance of utilizing marginal lands, waste streams, and high-yield feedstocks to minimize land competition with food production and natural ecosystems.

When implemented with appropriate sustainability safeguards, bioenergy can contribute significantly to climate change mitigation. Most recommended pathways to limit global warming to 1.5°C or 2°C include substantial contributions from bioenergy, with an average projection of approximately 200 exajoules (EJ) of bioenergy utilization by 2050 in climate stabilization scenarios [1]. The current bioenergy production stands at approximately 58 EJ annually, compared to 172 EJ from crude oil, 157 EJ from coal, and 138 EJ from natural gas, indicating significant growth potential [1].

The socio-economic dimensions of bioenergy further reinforce its significance in the renewable landscape. Bioenergy systems can stimulate rural development and create employment opportunities in agricultural and forestry sectors [3]. By creating markets for agricultural residues and waste products, bioenergy can provide additional income streams for farmers while addressing waste management challenges [3] [4]. However, these potential benefits must be balanced against concerns about land tenure, food security, and equitable distribution of economic opportunities, particularly in developing regions [4].

Bioenergy represents a critical and expanding component of the global renewable energy portfolio, offering versatile applications across electricity generation, heating, and transportation sectors. Its core significance lies in its ability to utilize diverse biological resources—from traditional biomass to advanced waste streams—while providing dispatchable power that complements intermittent renewables. The progression from first-generation to advanced feedstocks demonstrates an ongoing evolution toward more sustainable and efficient systems that minimize competition with food production and maximize environmental benefits.

The experimental frameworks and analytical methodologies presented provide researchers with standardized approaches for characterizing biomass and evaluating conversion processes, enabling comparable assessment of emerging bioenergy technologies. As global markets continue to expand—projected to reach $116.6 billion by 2030—ongoing technological innovations in conversion processes, feedstock development, and system integration will further enhance the economic and environmental performance of bioenergy systems.

For bioenergy to realize its full potential within a sustainable energy future, continued research, thoughtful policy frameworks, and careful consideration of sustainability dimensions will be essential. When developed with attention to environmental, social, and economic factors, bioenergy can make substantial contributions to climate change mitigation, energy security, and the transition toward a circular bioeconomy.

The classification of bio-based feedstocks into generations provides a critical framework for understanding the evolution of modern bioenergy systems. First-generation feedstocks represent the foundational biomass sources used in biofuel and bioproduct production, primarily derived from food crops rich in carbohydrates, sugars, and oils. These feedstocks include corn, wheat, sugarcane, potato, sugar beet, rice, and plant oils [7]. The terminology of "first-generation" emerged largely from the biofuel sector, where these materials served as the initial renewable alternatives to petroleum-based transportation fuels [7].

The historical significance of first-generation feedstocks lies in their role as pioneers in the transition toward a bio-based economy. They established the technological pathways for converting biological materials into energy and products, creating the foundation upon which advanced bio-refining concepts were built. Within research on feedstock progression, first-generation sources represent the starting point from which more specialized and sustainable feedstock generations have evolved [7].

From a technical perspective, first-generation feedstocks are characterized by their high annual carbohydrate yield per hectare and land use efficiency relative to other feedstock generations [7]. This efficiency, combined with well-established agricultural infrastructure and processing technologies, has maintained their relevance in current bioeconomy discussions despite the emergence of advanced alternatives.

Technical Characterization of First-Generation Feedstocks

Composition and Key Characteristics

First-generation feedstocks are predominantly valued for their high concentrations of readily accessible macromolecules that can be converted into fuels and chemicals through biological and chemical processes. The primary components include:

- Starch-based materials (corn, wheat, potatoes): Contain amylose and amylopectin polymers that can be hydrolyzed to fermentable sugars [8]

- Sucrose-rich crops (sugarcane, sugar beet): Accumulate high concentrations of disaccharides directly available for microbial conversion

- Oilseed crops (rapeseed, soybean, palm): Produce triacylglycerol molecules suitable for transesterification to biodiesel [9]

The efficiency of these feedstocks is measured through specific technical parameters, including annual carbohydrate yield per hectare and land used per ton of bioplastics or biofuels [7]. These metrics have established first-generation feedstocks as some of the most land-efficient options for bio-based production, though this must be balanced against potential trade-offs in the food system.

Quantitative Profile of Major First-Generation Feedstocks

Table 1: Global Biofuel Feedstock Utilization Patterns (2021)

| Feedstock Category | Global Production Volume | Primary Biofuel Application | Percentage of Global Crop Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maize/Corn | 127 million metric tons (U.S., 2011/12) | Ethanol | 16% of global production [9] |

| Sugarcane | Not specified | Ethanol | 22% of global production [9] |

| Vegetable Oils | Not specified | Biodiesel | 15% of global production [9] |

| Wheat | Not specified | Ethanol | <2% of global production [9] |

| Sugar Beets | Not specified | Ethanol | <2% of global production [9] |

Table 2: Feedstock Efficiency and Technical Properties

| Feedstock | Carbohydrate Content | Conversion Pathway | Primary Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corn | High starch (60-68% of dry weight) | Enzymatic hydrolysis + fermentation | Ethanol, animal feed (DDGS) |

| Sugarcane | High sucrose (12-17% of fresh weight) | Direct fermentation | Ethanol, electricity from bagasse |

| Vegetable Oils | High lipid content (varies by crop) | Transesterification | Biodiesel, glycerol |

| Wheat | High starch (60-65% of dry weight) | Enzymatic hydrolysis + fermentation | Ethanol, animal feed |

The data reveals the significant proportion of global agricultural production dedicated to bioenergy, particularly for maize, sugarcane, and vegetable oils. This scale of utilization has triggered ongoing research into optimizing the efficiency and sustainability of these feedstock pathways [9].

Methodologies for Evaluating Feedstock Efficiency and Impact

Experimental Framework for Carbohydrate Yield Assessment

Objective: To quantitatively determine the annual carbohydrate yield per hectare for major first-generation feedstocks under standardized conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Standardized planting materials for target crops (corn, wheat, sugarcane)

- Analytical grade solvents for extraction (ethanol, hexane, distilled water)

- Enzymatic kits for starch and sucrose quantification (amyloglucosidase, glucose oxidase-peroxidase)

- Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) equipment for rapid composition analysis

- Field trial plots with controlled irrigation and nutrient management systems

Procedure:

- Establish replicated trial plots for each feedstock crop using randomized complete block design

- Implement standardized agricultural practices throughout growing season

- Harvest mature crops and record total biomass yield per hectare

- Subsample for compositional analysis using standardized laboratory protocols

- For starch-based crops: employ acid hydrolysis followed by HPLC quantification of glucose monomers

- For sucrose crops: utilize ethanol extraction and polarimetric determination of sucrose content

- Calculate total carbohydrate yield per hectare using standardized conversion factors

- Statistical analysis of variance to determine significant differences between feedstock efficiency

This methodological approach has generated the comparative data demonstrating the superior land use efficiency of first-generation feedstocks compared to emerging alternatives [7].

Life Cycle Assessment Protocol for Food-Fuel Systems

Objective: To evaluate the environmental and food system impacts of diverting first-generation feedstocks to bioenergy production.

System Boundaries: Cradle-to-gate analysis including agricultural production, transportation, processing, and co-product allocation

Data Collection Parameters:

- Direct land use change metrics

- Agricultural input inventories (fertilizers, pesticides, irrigation)

- Crop yield data under different management regimes

- Market price correlations between food and fuel sectors

- Co-product utilization rates in animal feed markets

Impact Assessment Categories:

- Global warming potential (carbon footprint)

- Land use efficiency (output per hectare)

- Food price indices

- Protein availability from co-products

This methodology has been applied in recent studies indicating that first-generation biomass in non-food applications can strengthen food security by improving market stability and generating protein-rich by-products [10] [11].

The Food vs. Fuel Debate: Scientific Evidence and Evolving Perspectives

The "food versus fuel" debate represents one of the most significant controversies in bioenergy policy, centering on the allocation of agricultural resources between food production and energy feedstocks. This debate gained prominence during the 2007/08, 2010/11, and 2012/13 global food price spikes, when critics highlighted the role of biofuel policies in diverting crops from food to fuel applications [9].

Historical Context and Market Dynamics

The scale of feedstock diversion is substantial: approximately 16% of global maize production and 22% of sugarcane are currently used for ethanol production, while 15% of vegetable oil supplies are directed to biodiesel [9]. This significant allocation has created complex interconnections between agricultural and energy markets, where policy mandates rather than pure market forces often determine crop utilization.

Research indicates that the relationship between biofuel production and food prices is multifaceted. While diversion of crops to energy uses potentially reduces food availability, the effect is mitigated by several factors:

- Co-product generation: Approximately one-third of corn used for ethanol is recovered as nutrient-rich animal feed (distillers' dried grains with solubles) [12]

- Market flexibility: The ability to shift crops between food, feed, and industrial markets enables responsive adaptation to supply and demand fluctuations [10]

- Price stabilization: Multiple market outlets can reduce farmers' exposure to sector-specific price crashes, supporting agricultural sustainability

Recent empirical analyses suggest the food price impact may be more moderate than initially feared. One study found that a 12.4% reduction in agricultural land utilization for biofuel would increase food prices by only 3.3% [12].

Evolving Policy Mechanisms and Market Adaptations

In response to food-versus-fuel concerns, policymakers have developed more sophisticated approaches to bioenergy governance:

- Mandate "off-ramps": Provisions to temporarily suspend blending requirements during periods of food price stress [9]

- Integrated food-energy systems: Designs that optimize both food and fuel output from agricultural landscapes

- Cascading use principles: Prioritizing food applications first, then extracting energy from processing residues and wastes

The European Union demonstrated adaptive policy response in 2022 when member states adjusted biofuel production to mitigate impacts on vegetable oil prices following supply disruptions from Ukraine [9].

Benefits and Advantages of First-Generation Feedstocks

Agricultural and Economic Benefits

Recent research has reaffirmed several strategic advantages of first-generation feedstocks within integrated bioeconomy systems:

- Farm economic resilience: Diversified market options for crops reduce farmers' exposure to price fluctuations in any single sector, encouraging investment in innovation and sustainable practices [11]

- Protein co-production: First-generation biorefining generates valuable protein-rich byproducts that address critical needs in human and animal nutrition [10]

- Emergency food reserve capacity: The infrastructure and production systems supporting first-generation biomass create a latent capacity that can be rapidly redirected to food production during supply emergencies [10]

- Agricultural modernization driver: Bioenergy markets provide economic incentives for adoption of precision agriculture and sustainable intensification practices

A 2025 analysis highlighted that using first-generation biomass for non-food applications strengthens overall food security by increasing feedstock availability and market stability [10]. This represents a significant evolution in the understanding of food-fuel systems beyond simple competition frameworks.

Environmental and Decarbonization Benefits

While often criticized for land use impacts, first-generation feedstocks provide substantive environmental advantages:

- Immediate decarbonization pathway: First-generation biofuels offer a readily deployable alternative to fossil fuels in transportation, with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimating corn ethanol reduces greenhouse gas emissions by 40-45% compared to gasoline [9]

- Agricultural biodiversity protection: High-yield first-generation crop production minimizes the land footprint required to meet bioeconomy targets, potentially sparing more land for natural ecosystems [11]

- Carbon sequestration co-benefits: When integrated with conservation agriculture practices, first-generation feedstock systems can enhance soil carbon sequestration while producing renewable energy

The nova-Institute emphasizes that food crops represent among the most efficient land uses for producing starch, sugar, and plant oils, thereby reducing the total agricultural area needed to meet both food and industrial demands [11].

Research Tools and Methodologies

Essential Analytical Techniques for Feedstock Characterization

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Feedstock Analysis

| Research Reagent/Kit | Application in Feedstock Research | Technical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Amyloglucosidase Enzyme | Starch hydrolysis in grain feedstocks | Catalyzes breakdown of starch to glucose monomers for yield quantification |

| Glucose Oxidase-Peroxidase Assay Kit | Sugar quantification in processing streams | Enzymatic determination of glucose concentrations for mass balance calculations |

| Neutral Detergent Fiber Solution | Fiber analysis in feedstock and co-products | Quantifies lignocellulosic components to assess digestibility and process efficiency |

| Lipase Enzymes | Transesterification efficiency studies | Catalyzes biodiesel production from oil feedstocks for process optimization |

| Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Calibrations | Rapid composition analysis | Non-destructive determination of carbohydrate, protein, and moisture content |

| Yeast Strains for Fermentation | Ethanol yield optimization | Saccharomyces cerevisiae variants engineered for specific feedstock sugars |

Experimental Workflow for Comprehensive Feedstock Evaluation

First-generation feedstocks continue to play a pivotal role in global bioenergy systems despite the emergence of advanced alternatives. Their high land-use efficiency, established supply chains, and technological maturity maintain their competitive position within evolving bioeconomy strategies. Current research indicates an evolving understanding of their role—from simple competitors in the food system to potential components of integrated agricultural systems that enhance both energy and food security.

The future trajectory of first-generation feedstocks will likely involve increased integration with second-generation systems through biorefinery concepts that utilize both the starch/oil and lignocellulosic fractions of crops. This integrated approach represents the next frontier in feedstock progression research, potentially resolving the food-versus-fuel dilemma through technological innovation and system design optimization.

For researchers continuing investigation in this field, priority areas include development of high-yield crop varieties specifically designed for dual-purpose food-fuel systems, precision agriculture technologies to minimize environmental impacts, and circular bioeconomy models that optimize resource utilization across food, feed, and industrial sectors.

The history of modern bioenergy is characterized by a continuous evolution of feedstock sources, driven by the urgent need to balance energy demands with environmental and societal needs. First-generation biofuels, derived from edible biomass such as corn, sugarcane, and vegetable oils, initially offered a promising alternative to fossil fuels [13] [14]. However, these traditional feedstocks created an unsustainable "fuel versus food" paradigm, competing directly with agricultural land and resources needed for food production [13]. This competition, coupled with limitations in achieving significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions, compelled researchers to explore more sustainable alternatives, thereby catalyzing the transition to advanced feedstocks [13].

The expansion into next-generation feedstocks—including lignocellulosic biomass (agricultural residues, energy crops), municipal solid waste, algae, and captured carbon dioxide—represents a strategic pivot toward a circular bioeconomy [15] [16]. This shift is not merely technological but fundamental, moving from resource-intensive systems to ones that valorize waste, utilize marginal lands, and offer profound decarbonization benefits. With the global bioeconomy projected to reach $30 trillion by 2050, this transition is as much an economic imperative as an environmental one [17]. This whitepaper examines the multifaceted drivers, key methodologies, and future outlook of this critical expansion in feedstock research.

The Catalysts for Innovation: Drivers Behind the Feedstock Transition

Environmental and Climate Imperatives

The pressing need to decarbonize industrial and transportation sectors stands as a primary driver. The chemical industry, for instance, faces a significant challenge as over two-thirds of its emissions are embedded in the carbon content of its products, necessitating a shift to renewable carbon sources [15]. Next-generation feedstocks are crucial for hard-to-electrify sectors like aviation, shipping, and heavy-duty transport [18]. The International Maritime Organization's 2050 decarbonization targets and the EU's ReFuelEU Aviation regulation, which mandates a 6% sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) blend by 2030, are creating enforceable demand signals that first-generation biofuels cannot meet sustainably [18].

Addressing the Food-Fuel Conflict

Systematic research has quantified the limitations of first-generation feedstocks, with 56% of 224 reviewed studies reporting negative impacts on food security [13]. Critically, the analysis found no significant relationship between whether a feedstock was edible or inedible and its impact on food security (P value = 0.15), highlighting that the issue extends beyond mere edibility to broader land and resource competition [13]. This evidence has driven the focus toward inedible, waste-based, and residual resources that circumvent these conflicts entirely, supporting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals to end hunger while ensuring access to sustainable energy [13].

Economic Opportunities and Regulatory Tailwinds

The robust regulatory support is catalyzing significant market growth. Renewable diesel capacity is forecast to grow at a 16% CAGR between 2025 and 2030, while sustainable aviation fuel is set to expand at an even faster 36% CAGR over the same period [18]. Concurrently, the production capacity for chemicals from next-generation feedstocks is projected to grow at a 16% CAGR from 2025-2035, reaching over 11 million tonnes by 2035 [15]. This growth is underpinned by corporate commitments from leaders like Maersk, which has over 25 methanol-fueled vessels on order, and United Airlines, targeting 10% SAF by 2030 [18].

Table 1: Projected Global Growth of Next-Generation Fuel and Feedstock Capacity

| Fuel/Feedstock Type | Projected CAGR (2025-2030/2035) | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) | 36% (2025-2030) | EU ReFuelEU Aviation Regulation, Airline Commitments |

| Renewable Diesel | 16% (2025-2030) | Heavy-Duty Transport Decarbonization |

| Chemicals from Next-Gen Feedstocks | 16% (2025-2035) | Corporate Sustainability Commitments, Carbon Taxes |

Classifying Next-Generation Feedstocks and Their Applications

Lignocellulosic Biomass

Lignocellulose, the most abundant form of terrestrial biomass, accounts for approximately 57% of the planet's biogenic carbon [16]. Its components—cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—are utilized across diverse applications:

- Cellulose: Traditionally used for paper, it now enables advanced applications like nanocelluloses for energy storage, biomedical scaffolds, and reinforced composites [16].

- Hemicellulose: A heterogeneous polymer converted into platform chemicals like sorbitol, xylitol, and 2,3-Butanediol, with emerging uses in films, aerogels, and carbon quantum dots [16].

- Lignin: The most challenging component due to its complexity, is the subject of advanced valorization research. Methods like hydrogenolysis and acidolysis are being developed to convert it into valuable phenol aldehydes (e.g., vanillin) and polymer precursors (e.g., for nylon) [16].

Waste and Residual Feedstocks

This category includes municipal solid waste (MSW), agricultural residues, and waste oils. Their appeal lies in enabling a circular economy by converting waste streams into valuable products. Companies like Dow Chemical are investing in technologies to process plastic waste into chemical products, with one project aiming to process 21 kilotonnes annually [15].

Novel Biological Feedstocks

Algae and other engineered microorganisms represent the third generation of feedstocks. They offer high yield potential without competing for arable land and can be cultivated using industrial COâ‚‚ emissions, providing a dual carbon sequestration and utilization pathway [18].

Carbon Dioxide and Greenhouse Gases

The direct utilization of COâ‚‚ as a chemical feedstock is an emerging frontier. Technologies are being developed to transform captured carbon into fuels and chemical intermediates, potentially closing the carbon loop in industrial systems [15] [19].

Table 2: Next-Generation Feedstock Classification and Characteristics

| Feedstock Class | Specific Examples | Key Advantages | Current Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Agricultural residues (e.g., corn stover), energy crops (e.g., switchgrass), woody biomass | Abundant, non-food competing, carbon-neutral potential | Recalcitrance to breakdown, requires advanced processing |

| Waste & Residuals | Municipal Solid Waste (MSW), used cooking oil, agricultural waste, plastic waste | Circular solution, reduces waste disposal, widely available | Heterogeneous composition, requires sorting/separation |

| Novel Biological | Algae, engineered microorganisms | High yield per acre, does not require arable land | High capital costs, scalability of cultivation |

| Carbon Dioxide | Industrial flue gases, direct air capture | Utilizes GHG emissions, potential for carbon-negative processes | Energetically demanding conversion processes |

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

The conversion of next-generation feedstocks into valuable products relies on sophisticated experimental protocols that integrate biological, chemical, and engineering principles.

Lignocellulosic Biomass Conversion Workflow

Feedstock Selection and Preparation

The process begins with the selection of appropriate biomass, such as agricultural residues (corn stover, wheat straw) or dedicated energy crops (switchgrass, Miscanthus) [16]. The feedstock is prepared through communition (chipping, grinding, milling) to achieve a uniform particle size, increasing the surface area for subsequent processing steps [16].

Pretreatment Protocols

Pretreatment is critical for overcoming the recalcitrance of lignocellulose. Common methods include:

- Steam Explosion: Biomass is treated with high-pressure saturated steam (160-260°C) for several minutes, followed by rapid decompression.

- Dilute Acid Pretreatment: Uses sulfuric or sulfurous acid (0.5-1.5%) at elevated temperatures (130-210°C) to hydrolyze hemicellulose.

- Alkaline Pretreatment: Employing sodium, calcium, or ammonium hydroxide at milder temperatures to remove lignin. The effectiveness of pretreatment is evaluated by measuring cellulose digestibility, hemicellulose sugar recovery, and inhibitor formation [16].

Enzymatic Hydrolysis

Pretreated biomass is subjected to enzymatic saccharification using cellulase enzymes (e.g., from Trichoderma reesei) and hemicellulases. This is typically performed at 45-50°C and pH 4.5-5.0 for 24-72 hours. The resulting hydrolysate contains monomeric sugars (glucose, xylose, arabinose) ready for subsequent upgrading [16].

Lignin Valorization Techniques

Lignin valorization employs specialized methods to depolymerize the complex polymer:

- Hydrogenolysis: Uses hydrogen gas with catalysts (e.g., Ni, Ru, Pd) at elevated temperatures and pressures (200-300°C, 20-100 bar H₂) to break β-O-4 linkages.

- Oxidative Depolymerization: Employs oxidants (oxygen, peroxide) with catalysts to break lignin into aromatic aldehydes (vanillin, syringaldehyde).

- Biological Depolymerization: Utilizes microorganisms (e.g., Rhodococcus, Pseudomonas species) or enzymes (laccases, peroxidases) for selective lignin degradation [16].

Analytical and Characterization Methods

Advanced characterization is essential for understanding feedstock composition and conversion efficiency:

- NREL Standard Methods: For determining structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass.

- HPLC: For quantifying sugar monomers, degradation products, and fermentation inhibitors.

- GC-MS: For identifying and quantifying lignin-derived phenolic compounds.

- NMR Spectroscopy: (²³C, ²D HSQC) for elucidating lignin structure and linkage composition [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Next-Generation Feedstock Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Genome editing of feedstocks and microbes to improve traits | Enhancing biomass yield, climate resilience, or microbial substrate utilization [16] |

| Specialized Enzymes | Breakdown of complex biomass polymers | Cellulases (Cellic CTec), Hemicellulases, Laccases for lignin modification [16] |

| Ionic Liquids | Green solvents for biomass pretreatment and fractionation | Effective for lignin extraction; e.g., Sonichem's ultrasonic cavitation process [15] |

| Heterogeneous Catalysts | Catalyze depolymerization and upgrading reactions | Metal catalysts (Ni, Ru) for hydrogenolysis; Zeolites for catalytic fast pyrolysis [16] |

| Engineered Microbes | Fermentation of mixed sugar streams to target molecules | E. coli, S. cerevisiae engineered to produce biopolymers (PHA), nylon precursors [16] |

| AI/ML Platforms | Accelerate feedstock engineering and process optimization | Machine learning models to guide CRISPR editing; predictive models for process scaling [16] |

| 3a-Epiburchellin | 3a-Epiburchellin, MF:C20H20O5, MW:340.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Bulleyanin | Bulleyanin, MF:C28H38O10, MW:534.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technological Pathways and System Integration

The conversion of next-generation feedstocks occurs through two primary pathways: biological and thermochemical, with increasing integration into biorefinery concepts.

Integrated Biorefineries

The biorefinery concept represents the full integration of farming and conversion processes to produce bioenergy and biomaterials, analogous to petroleum refineries but based on renewable resources [16]. These facilities aim to maximize value extraction by processing various feedstock components into multiple products—fuels, power, chemicals, and materials—enhancing overall economics and sustainability [16].

Emerging Conversion Technologies

- Catalytic Fast Pyrolysis: Thermochemical conversion of biomass at moderate temperatures (400-600°C) in the absence of oxygen, using catalysts to produce upgraded bio-oil.

- Hydrothermal Liquefaction: Uses supercritical water (350-400°C, 180-250 bar) to convert wet biomass (including algae) into biocrude.

- Gasification and Syngas Fermentation: Thermal conversion to syngas (CO+Hâ‚‚) followed by biological fermentation to ethanol or other chemicals using specialized microbes (e.g., Clostridium ljungdahlii) [14].

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The advancement of next-generation feedstocks is poised to accelerate with convergence of multiple disruptive technologies:

- AI and Machine Learning: These tools are revolutionizing feedstock development by predicting optimal genetic modifications, modeling catalytic processes, and optimizing biorefinery operations [16]. Democratized AI resources enable sophisticated machine learning models that guide next-generation mutagenesis and breeding [16].

- Synthetic Biology: Advanced genome editing and metabolic engineering allow for the design of customized feedstocks with enhanced traits and engineered microbes for more efficient conversion processes [15] [19].

- Advanced Catalysis: Research continues to develop more selective and stable catalysts for lignin depolymerization and sugar upgrading, with nanomaterials playing an increasing role [16].

The transition to next-generation feedstocks represents a generational opportunity, with the U.S. and other nations positioned to leverage agricultural strength into bioeconomic leadership [17]. However, success will require coordinated national strategies, significant investment—estimated between $440 billion and $1 trillion through 2040—and workforce development to build talent fluent in biology, chemical engineering, AI, and advanced manufacturing [17] [19]. With these elements in place, next-generation feedstocks will fundamentally reshape the production of chemicals, materials, and fuels, supporting a more sustainable and circular industrial ecosystem.

Lignocellulosic biomass, the most abundant renewable organic resource on Earth, represents a critical feedstock in the global transition toward sustainable energy and a circular bioeconomy [20] [16]. Comprising primarily agricultural and forestry residues, this biomass source is gaining prominence as a sustainable alternative to first-generation feedstocks that compete with food production [21] [22]. The inherent complexity of lignocellulosic structure, while presenting processing challenges, offers a versatile platform for producing biofuels, biochemicals, and bioproducts [16]. Within the broader historical context of modern bioenergy, lignocellulosic residues mark a significant progression in feedstock development, moving from food-grade resources to abundant waste streams and dedicated energy crops, thereby addressing concerns over food security and land use [21] [22]. This shift aligns with global decarbonization goals and circular economy principles, positioning lignocellulosic biomass as a cornerstone of renewable energy strategies and sustainable industrial transformation [23] [16].

Composition and Structural Characteristics

Lignocellulosic biomass forms the structural framework of plants and consists primarily of three polymeric components: cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [20]. The composition varies significantly based on plant species, geographical location, and growing conditions [21].

Table 1: Typical Composition of Lignocellulosic Biomass from Various Sources (Dry Weight Percentage)

| Biomass Source | Cellulose (%) | Hemicellulose (%) | Lignin (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Residues | 30-50 | 20-35 | 15-25 |

| Woody Biomass | 40-60 | 20-30 | 20-30 |

| Grasses | 30-50 | 25-40 | 10-20 |

Data synthesized from [21] [20]

Cellulose, the dominant component (30-60% of dry weight), is a linear polymer of β-D-glucose units connected by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds [20]. These chains form organized microfibrils with crystalline regions that provide structural strength but also contribute to biomass recalcitrance [21] [20].

Hemicellulose (20-35% of dry weight) is a heterogeneous, amorphous polymer containing various sugar monomers including pentoses (xylose, arabinose) and hexoses (mannose, galactose, glucose) [21] [20]. Unlike cellulose, hemicellulose exhibits branching and lower polymerization degree, making it more susceptible to hydrolysis [21].

Lignin (15-30% of dry weight) is a complex, cross-linked phenolic polymer that provides structural integrity and microbial resistance [21] [20]. This non-carbohydrate component acts as a physical barrier, impeding access to cellulose and hemicellulose, and must be disrupted during pretreatment [21].

The intricate association of these components through covalent and non-covalent interactions creates a robust composite material that is highly resistant to deconstruction, a property known as recalcitrance [20]. This structural complexity fundamentally influences all subsequent processing methodologies and conversion efficiencies.

Figure 1: Structural Composition of Lignocellulosic Biomass. The diagram illustrates the three primary polymeric components and their contributions to biomass recalcitrance, which presents the fundamental challenge in biofuel production.

Global Market Context and Projections

The lignocellulosic biomass market demonstrates substantial growth potential, driven by increasing global demand for renewable energy and sustainable materials. Current market analysis projects the global lignocellulosic biomass market to grow from USD 4.61 billion in 2025 to USD 9.76 billion by 2035, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.8% [24]. This expansion is fueled by several factors, including supportive government policies, technological advancements in conversion processes, and growing emphasis on decarbonizing energy systems [24].

Table 2: Lignocellulosic Biomass Market Overview and Projections

| Parameter | Value | Timeframe |

|---|---|---|

| Market Size 2025 | USD 4.61 billion | 2025 |

| Projected Market Size 2035 | USD 9.76 billion | 2035 |

| CAGR | 7.8% | 2025-2035 |

| Dominant Source Segment | Wood (38% market share) | 2025 |

| Leading Application Segment | Bioenergy (15% market share) | 2025 |

Data sourced from [24]

Wood is projected to capture 38% of the lignocellulosic biomass market share by 2025, representing the most commonly used feedstock due to its wide availability, high energy content, and suitability for various industrial applications [24]. Major companies involved in wood-based lignocellulosic biomass supply include UPM-Kymmene, Georgia-Pacific, and West Fraser Timber [24]. Bioenergy production is expected to account for 15% of the market share, with leading companies like Bioenergy DevCo, POET, and Abengoa converting lignocellulosic biomass into biofuels and biogas for industrial and commercial applications [24].

Regional growth patterns vary significantly, reflecting local resource availability, policy frameworks, and industrial priorities. The United States market is projected to rise at a 5.0% CAGR through 2035, influenced by the shale gas revolution and supportive regulations like the Renewable Fuel Standard [24]. Brazil demonstrates strong growth potential (4.5% CAGR), leveraging its unparalleled biomass resources, particularly sugarcane bagasse from its thriving sugarcane industry [24]. China leads growth projections with a 6.5% CAGR, driven by emphasis on rural revitalization and technological leadership in biorefinery processes [24]. Canada anticipates a 4.0% CAGR, focusing on diversifying its energy mix and reducing reliance on conventional fossil fuels [24].

Experimental Methodologies for Biomass Processing

Biomass Pretreatment Protocols

Pretreatment is essential to overcome lignocellulosic recalcitrance by disrupting the lignin-carbohydrate complex, increasing porosity, and making cellulose more accessible to enzymatic attack [21]. Various pretreatment methods have been developed, with biological approaches gaining prominence for their environmental benefits.

Biological Pretreatment Methodology

- Objective: Partial delignification and reduction of cellulose crystallinity using microorganisms and their enzymatic systems [21].

- Microbial Strains: Fungal species including Aspergillus spp. and Trichoderma spp. are most effective at industrial scale due to their superior ability to produce multiple extracellular enzymes [21]. White-rot fungi (Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Ceriporiopsis subvermispora) are particularly efficient for lignin degradation [21].

- Protocol:

- Biomass Preparation: Reduce biomass to 2-5 mm particle size to increase surface area for microbial attack [21].

- Moisture Adjustment: Adjust moisture content to 70-80% to create optimal conditions for fungal growth while maintaining aerobic conditions [21].

- Inoculation: Inoculate with fungal spores or mycelium at 10â¶-10⸠spores per gram dry biomass [21].

- Incubation: Maintain temperature at 25-30°C for fungi (mesophilic range) for 15-30 days, with periodic mixing for aeration [21].

- Enzyme Production: Fungi secrete ligninolytic enzymes (laccases, peroxidases) and hydrolytic enzymes (cellulases, xylanases) that progressively degrade lignin and hemicellulose [21].

- Process Termination: Heat treatment at 90-100°C for 30 minutes to terminate biological activity [21].

- Advantages: Low energy requirement, mild operating conditions, no chemical inhibitors formation, environmentally friendly [21].

- Limitations: Slow process rate, potential carbohydrate loss, requires strict control of growth conditions [21].

Enzymatic Hydrolysis and Microbial Conversion

Following pretreatment, enzymatic hydrolysis converts polysaccharides into fermentable monosaccharides, which can subsequently be transformed into valuable products through microbial fermentation [21].

Enzymatic Hydrolysis Protocol

- Objective: Depolymerize cellulose to glucose and hemicellulose to pentose sugars using enzyme cocktails [21].

- Enzyme Systems: Commercial enzyme preparations containing endoglucanases, exoglucanases, β-glucosidases, and hemicellulases (xylanases) [21]. Optimal enzyme loading typically ranges from 5-20 FPU/g cellulose [21].

- Reaction Conditions:

- Synergistic Approach: Incorporation of xylanases with cellulolytic enzymes enhances hydrolysis efficiency through synergistic interaction, particularly for agricultural residues with high hemicellulose content [21].

Microbial Lipid Production via Oleaginous Microorganisms

- Objective: Convert hydrolysate sugars to microbial oils (triacylglycerols) for biodiesel production [21].

- Microbial Strains: Oleaginous yeasts (Rhodosporidium toruloides, Lipomyces starkeyi, Yarrowia lipolytica), fungi (Mortierella isabellina), and algae [21].

- Culture Conditions:

- Carbon source: Lignocellulosic hydrolysate containing glucose, xylose, and other sugars [21]

- C:N ratio: High ratio (>50:1) to trigger lipid accumulation [21]

- Temperature: 28-30°C for most oleaginous yeasts [21]

- pH: 5.5-6.5 [21]

- Aeration: High oxygen transfer required for efficient lipid production [21]

- Lipid Extraction: Biomass harvesting, drying, and lipid extraction using organic solvents (hexane or chloroform-methanol mixture) [21].

- Transesterification: Conversion of microbial oils to biodiesel (fatty acid methyl esters) using alkaline catalysts [21].

Figure 2: Biomass Conversion Workflow. The diagram outlines the key steps in converting lignocellulosic biomass to biofuels, highlighting biological pretreatment and microbial oil production as critical stages.

Advanced Research Reagents and Materials

The field of lignocellulosic biomass research utilizes specialized reagents and materials to enable efficient biomass deconstruction and conversion. The following table details key research tools and their applications in experimental protocols.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Lignocellulosic Biomass Conversion

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aspergillus spp. Enzymes | Produces extracellular cellulase, xylanase, and β-glucosidase cocktails | Most effective for agricultural residues; works synergistically with bacterial enzymes [21] |

| Trichoderma spp. Enzymes | Secretes complete cellulase system for cellulose hydrolysis | Industrial standard for cellulose degradation; requires supplementation with β-glucosidase [21] |

| Oleaginous Yeasts (R. toruloides, L. starkeyi) | Accumulates lipids (TAGs) under nutrient stress | Capable of utilizing both C5 and C6 sugars; high carbon-to-nitrogen ratio triggers lipid production [21] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Systems | Genome editing for enhanced feedstock traits | Improces biomass yield, reduces recalcitrance; informed by machine learning models [16] |

| Ionic Liquids | Green solvents for biomass pretreatment | Effective for lignin dissolution; offers energy-efficient, selective separation [25] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents | Low-cost alternative to ionic liquids | Exhibits high selectivity for lignin removal; enhances enzymatic digestibility [25] |

| Nanocellulose Materials | High-value product from cellulose | Used in composites, packaging, medical applications; represents biorefinery valorization [16] |

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Beyond bioenergy, lignocellulosic biomass is increasingly utilized in diverse applications that support circular bioeconomy objectives. The conversion of lignocellulosic residues to single-cell protein (SCP) represents a promising approach for sustainable food and feed production [20]. With protein content ranging from 60-82% of dry cell weight and containing all essential amino acids, SCP derived from microorganisms grown on lignocellulosic hydrolysates offers a nutritional profile comparable to traditional protein sources [20]. This application simultaneously addresses waste management and protein security challenges.

In the materials sector, nanocellulose derived from lignocellulosic fibers is enabling new generations of sustainable materials with applications in energy storage, medical devices, and functional packaging [16]. These nanomaterials retain the inherent advantages of cellulose while exhibiting unique properties derived from their nano-scale dimensions, including large surface area and versatile reactive sites [16]. Advanced wood engineering techniques are producing novel materials such as densified wood, transparent wood, and thermally modified wood with enhanced properties for construction and specialty applications [16].

Lignin valorization remains a significant challenge and opportunity. While currently primarily burned for energy, research efforts are advancing conversion methods including hydrogenolysis, acidolysis, and biological depolymerization to transform lignin into value-added products such as biopolymers, polymer precursors, and specialty chemicals [16]. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning in feedstock development and process optimization is accelerating these advancements, enabling predictive models for biomass traits and conversion efficiency [16].

The transition to wood-based circular bioeconomy is gaining momentum, with research focusing on cascading use of wood products whereby materials are first used in high-value applications before being recycled or converted into energy [23]. This approach maximizes value retention and minimizes waste throughout the product lifecycle, supporting climate change mitigation through carbon sequestration and substitution of fossil-based products [23].

The evolution of modern bioenergy has been characterized by a continuous search for sustainable, non-food feedstocks that avoid the food-versus-fuel dilemma associated with first-generation biofuels. This progression has advanced from food crops to lignocellulosic materials, and now to third-generation feedstocks including algae and the organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW). These emerging feedstocks represent a transformative approach to waste management and energy production, aligning with circular economy principles by converting waste streams into valuable bio-based products [26] [22]. The integration of algae and MSW within biorefinery concepts demonstrates potential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, promoting resource efficiency, and contributing to multiple United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities), SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), and SDG 13 (Climate Action) [27] [28].

The global urgency for this transition is underscored by staggering statistics: municipal solid waste generation is projected to reach 3.40 billion tonnes annually by 2050, while unsustainable linear food systems result in approximately 1.3 billion tonnes of food loss and waste each year [27] [28] [29]. Without intervention, global waste could reach 4.54 billion tons by 2050, with direct economic costs of $400 billion and roughly 2.38 billion tons of COâ‚‚-equivalent emissions annually [27]. Simultaneously, algae have emerged as a promising feedstock due to their high proliferation rates, minimal land requirements, and ability to thrive in wastewater or saline conditions without competing with food supplies [30] [31]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical examination of these emerging feedstocks within the historical context of bioenergy development, detailing characterization methods, conversion pathways, experimental protocols, and research frameworks essential for advancing their integration.

Technical Characterization of Feedstocks

Composition and Biofuel Potential of Algal Biomass

Algal biomass is categorized into microalgae (unicellular) and macroalgae (multicellular seaweeds), each with distinct compositional profiles and conversion potentials. Microalgae demonstrate remarkable biochemical versatility, with composition varying significantly by species and cultivation conditions:

- Lipids: 7-65% of dry weight, with certain strains like Botryococcus braunii accumulating up to 80% lipids under stress conditions [30] [31]

- Proteins: Up to 70% of dry weight in specific species [31]

- Carbohydrates: 10-25% of dry weight, including starch and β-glucans [31]

Macroalgae exhibit different compositional patterns, being generally rich in carbohydrates (32-60% dry weight) but containing lower lipid content (2-13% dry weight) [31]. The predominant carbohydrates vary by algal group: brown algae synthesize alginate, laminarin, and mannitol; red algae produce galactans such as agar and carrageenan; and green seaweeds contain ulvan and other glucans [31]. Notably, both microalgae and macroalgae lack lignin, significantly reducing recalcitrance compared to terrestrial biomass and facilitating downstream processing for biofuel production [31].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Algal Feedstock Composition and Key Characteristics

| Parameter | Microalgae | Macroalgae |

|---|---|---|

| Lipid Content | 7-65% (dry weight) | 2-13% (dry weight) |

| Protein Content | Up to 70% (dry weight) | 7-31% (dry weight) |

| Carbohydrate Content | 10-25% (dry weight) | 32-60% (dry weight) |

| Lignin Content | Negligible | Negligible |

| Growth Rate | High (double biomass in hours) | Moderate to High |

| Land Requirement | 1.2×10ⶠha for 41.5×10â¹ Lyrâ»Â¹ biofuels | Varies by species |

| CO₂ Sequestration | 10-50× faster than terrestrial plants | Moderate |

Municipal Solid Waste Composition and Valorization Potential

The organic fraction of municipal solid waste (OFMSW) presents a heterogeneous but valuable feedstock stream comprising food waste, paper, cardboard, and other biodegradable materials. The compositional variability of MSW necessitates sophisticated characterization and sorting systems for effective biorefinery integration:

- Organic Content: Approximately 46% of total MSW, comprising carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids from food waste and biodegradable materials [29]

- Global Generation: Projected to reach 3.40 billion tonnes by 2050, a significant increase from current levels of approximately 2.01 billion tonnes [29]

- Current Disposition: Over 50% of MSW is currently sent to landfills in many countries, with about 70% of globally collected waste destined for landfills [27] [32]

Advanced sorting technologies utilizing spectroscopy, computer vision, and machine learning enable rapid identification and characterization of MSW components, determining calorific value and directing materials to appropriate conversion pathways [27] [32]. This smart MSW management system can be coupled with robotic systems to redirect organic fractions in real-time at multiple conveyor speeds to conversion-ready feedstock destinations [32].

Table 2: Municipal Solid Waste Characterization and Management Metrics

| Parameter | Current Value | Projected 2050 |

|---|---|---|

| Global MSW Generation | 2.01 billion tonnes/year | 3.40 billion tonnes/year |

| Organic Fraction (OFMSW) | 46% of total MSW | Similar or higher percentage |

| Recycling Rate (EU) | 49% (2021) | Target: 65% by 2035 |

| Landfill Disposition | >50% (US); ~70% (global) | Target: Significant reduction |

| Food Waste GHG Contribution | 8-10% of global emissions | Dependent on management improvements |

Integrated Biorefinery Configurations and Methodologies

Experimental Framework for MSW-Valorizing Biorefineries

The URBIOFIN project demonstrates an innovative modular biorefinery concept for transforming OFMSW into new bio-based products through three interconnected modules [29]:

Module 1: Bioethanol and Bioethylene Production

- Feedstock Preparation: OFMSW undergoes mechanical pre-treatment (shredding, homogenization) and enzymatic hydrolysis to break down complex carbohydrates into fermentable sugars.

- Fermentation Process: Utilizing Saccharomyces cerevisiae or other robust yeast strains under controlled conditions (30°C, pH 5.0) for 48-72 hours.

- Downstream Processing: Distillation and dehydration to produce fuel-grade bioethanol (99.5% purity).

- Catalytic Conversion: Vapor-phase catalytic dehydration of bioethanol to bioethylene using γ-alumina catalyst at 300-400°C.

Module 2: Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) Production

- Acidogenic Fermentation: OFMSW and vinasse (by-product from Module 1) undergo two-stage anaerobic digestion to produce volatile fatty acids (VFAs).

- VFA Recovery: Extraction and concentration of VFAs through membrane separation or centrifugation.

- PHA Accumulation: Fed-batch cultivation of PHA-accumulating bacteria (e.g., Cupriavidus necator) under nitrogen-limited conditions to promote polymer accumulation.

- PHA Extraction: Solvent-based extraction using chlorinated solvents or green solvents under optimized conditions.

Module 3: Biomethane and Biofertilizer Production

- Anaerobic Digestion: OFMSW processing in continuous stirred tank reactors (35-37°C, hydraulic retention time 20-30 days).

- Biogas Upgrading: Microalgae-based COâ‚‚ capture from biogas to produce biomethane (>95% CHâ‚„).

- Microalgae Cultivation: Chlorella vulgaris or Scenedesmus species grown in digestate-rich medium.

- Biofertilizer Production: Hydrolysis of microalgae biomass to produce amino acid-rich liquid fertilizer; solid digestate processing into granulated biofertilizer.

Diagram 1: URBIOFIN modular biorefinery concept for MSW valorization. AT: 76 characters

Experimental Protocols for Food Waste Valorization via Microalgae

The integration of food waste and microalgae cultivation represents a promising circular bioeconomy approach. The following detailed methodology outlines key processes for utilizing food waste as a nutrient source for microalgae cultivation targeting lipid production [28]:

Food Waste Pre-treatment and Hydrolysate Preparation

- Collection and Characterization: Gather food waste from controlled sources (households, restaurants, food processing facilities) and characterize nutritional composition (total carbohydrates, proteins, lipids).

- Size Reduction: Employ mechanical grinding or homogenization to achieve particle size <2 mm for enhanced surface area.

- Enzymatic Hydrolysis:

- Apply commercial enzyme cocktails (amylases, proteases, cellulases) at optimal conditions (45-50°C, pH 4.5-5.5 for amylases; 50-55°C, pH 7.0-8.0 for proteases).

- Maintain hydrolysis for 12-24 hours with continuous agitation at 150-200 rpm.

- Terminate enzymatic activity by heat treatment (90°C for 10 minutes).

- Solid-Liquid Separation: Centrifuge at 8,000×g for 15 minutes and filter through 0.2 μm membranes to obtain clear hydrolysate.

- Nutrient Analysis: Quantify reducing sugars (DNS method), total nitrogen (Kjeldahl method), total phosphorus (ascorbic acid method), and micronutrients (ICP-MS).

Microalgae Cultivation in Food Waste Hydrolysate

- Strain Selection: Employ oleaginous microalgae strains such as Chlorella vulgaris, Scenedesmus obliquus, or Nannochloropsis sp.

- Medium Formulation:

- Blend food waste hydrolysate with basal salt medium to achieve optimal C/N/P ratio (approximately 100:10:1).

- Adjust pH to 7.0-7.5 using NaOH or HCl.

- Sterilize by autoclaving at 121°C for 15 minutes.

- Inoculum Preparation: Pre-culture microalgae in standard medium to late exponential phase, harvest by centrifugation, and wash with sterile medium.

- Cultivation Conditions:

- Photobioreactor operation: Temperature 25±2°C, light intensity 100-200 μmol photons/m²/s, photoperiod 16:8 light:dark cycle.