Computational Fluid Dynamics for Biomass Drying: A Comprehensive Guide to Simulation, Optimization, and Validation

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) applications in biomass drying processes, addressing critical needs for researchers and engineers in renewable energy and sustainable processing.

Computational Fluid Dynamics for Biomass Drying: A Comprehensive Guide to Simulation, Optimization, and Validation

Abstract

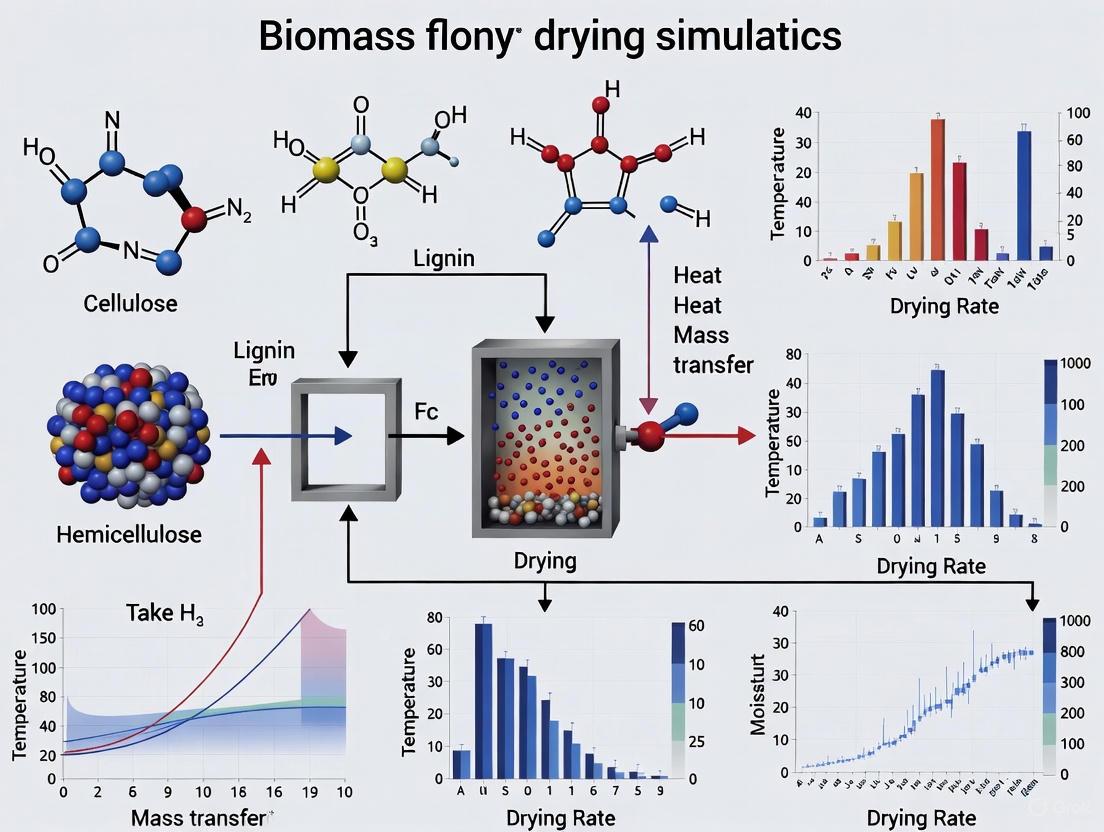

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) applications in biomass drying processes, addressing critical needs for researchers and engineers in renewable energy and sustainable processing. It explores foundational CFD principles governing multiphase heat and mass transfer in biomass systems, details methodological approaches for various dryer configurations including hybrid solar-biomass systems and fluidized beds, and presents advanced optimization strategies for tray design and operational parameters. The content further covers rigorous validation techniques through experimental comparison and machine learning integration, synthesizing cutting-edge research to enhance drying efficiency, product quality, and system design across agricultural and industrial applications.

Fundamentals of CFD in Biomass Drying: Principles and Multiphase Transport Phenomena

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) provides a powerful, cost-effective tool for analyzing and optimizing complex drying processes, which are critical in industries ranging from biomass energy to pharmaceuticals [1]. By solving systems of partial differential equations governing fluid flow, heat, and mass transfer, CFD enables researchers to prototype designs virtually and gain microscopic-scale insights that are difficult to obtain experimentally [1]. For biomass drying specifically, CFD modeling helps improve process efficiency, reduce pollutant emissions, and understand intra-particle phenomena like moisture transfer during thermal conversion [2]. This document establishes application notes and protocols for implementing CFD frameworks within biomass drying simulation research.

Fundamental Drying Models in CFD

The drying process in biomass particles involves complex heat and mass transfer mechanisms. CFD modeling typically approaches evaporation through several distinct theoretical frameworks, each with specific applications and limitations.

Table 1: Fundamental Drying Models for Biomass CFD Simulations

| Model Name | Governing Principle | Application Context | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium Model [2] | Liquid water exists in equilibrium with local water vapor in wood pores | Low-temperature drying models | Gas and solid phases share the same temperature inside the particle |

| Heat Sink Model [2] | Evaporation occurs at a constant rate when particle temperature reaches saturation point | Thermally thick particle simulations | Particle temperature remains constant at water saturation temperature during drying |

| Arrhenius Model [2] | Evaporation rate follows temperature-dependent Arrhenius equation | General drying processes with reaction kinetics | Immediate outflow of gas species from the reaction zone; no recondensation |

The selection of an appropriate drying model depends on specific particle characteristics and process conditions. For single biomass particles, user-defined functions (UDFs) can be employed to characterize the drying process by solving transport equations for solid temperature (Ts) and moisture mass fraction (Xm) [2].

CFD Protocol: Single Biomass Particle Drying

This protocol details the methodology for simulating drying behavior in a single biomass particle using ANSYS Fluent, based on established research practices [2].

Model Setup and Assumptions

- Geometry Creation: Generate three-dimensional geometries for common fuel shapes: cylindrical (standard wood pellet), cuboid, and spherical configurations [2].

- Key Assumptions:

- Energy and mass exchange occur only through boundary layers

- Solid particle consists solely of moisture and dry wood

- Particle porosity is considered, but movement during evaporation is ignored

- Volume shrinkage during drying is considered negligible [2]

Meshing Guidelines

- Generate appropriate meshes with sensitivity analysis

- Concentrate more grid nodal points near walls to resolve external radiation exposure

- Validate mesh density independence across different geometries [2]

Boundary Conditions

- Implement appropriate boundary conditions for heat and mass transfer

- For experimental validation setups, configure based on standardized conditions:

- Particle diameters: 10-12 mm

- Pressure: 2.4 bar

- Superheated steam temperature: 170°C

- Steam velocity: 2.7 m/s [3]

Solver Settings

- Implement User Defined Functions (UDFs) for characteristic drying processes

- Define two user defined scalars for:

- Solid temperature (Ts)

- Mass fraction of moisture (Xm) in both Heat Sink and Arrhenius models [2]

CFD Protocol: Vibrating Fluidized Bed Dryer Simulation

For industrial-scale applications, vibrating fluidized bed dryers represent advanced technology for biomass processing. This protocol outlines a DEM-CFD coupling approach for simulating these systems [3].

DEM-CFD Coupling Methodology

- Framework Selection: Implement a Discrete Element Method (DEM) coupled with CFD using OpenFOAM

- Particle Modeling: Describe processes inside each particle using one-dimensional, transient conservation equations of mass and energy

- Bed Representation: Model the arrangement of particles within surrounding gas as void space, with flow through voids represented as porous medium [3]

Governing Equations

- Solve coupled heat, mass, and momentum transfer between solid and gas phases

- Account for particle-to-fluid heat transfer using characteristic quantities:

- Appropriate length scales and velocities

- Geometrical functions

- Statistical parameters of the porous medium (void fraction) [3]

Operational Parameters

Primary Variables:

- Inlet gas temperature (300-400°C)

- Gas velocity (1-2 m/s)

- Initial dryer temperature

- Initial moisture content of particles (25-65%)

- Vibration intensity

- Particle size distribution [3]

Drying Medium: Superheated steam provides advantages over air:

- Increased efficiency

- Improved safety (reduced fire/explosion risk)

- Faster drying rates

- Combination of drying with material sterilization [3]

Simulation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Computational Tools for CFD Drying Research

| Reagent/Tool | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Feedstocks [3] [4] | Beechwood, Agave Bagasse; Particle size: 0.1-1mm | Primary material for drying simulations; agricultural residues most common |

| Drying Media [3] | Superheated steam, air, flue gas; Temperature: 300-400°C | Heat transfer fluid for convective drying |

| CFD Software [2] [3] [1] | ANSYS Fluent, COMSOL, OpenFOAM | Platform for solving transport equations |

| Colormap Tools [5] [6] | Perceptually uniform schemes (not rainbow) | Data visualization for interpretation |

| DEM-CFD Coupling [3] | OpenFOAM with discrete element method | Particle-level resolution in bed dryers |

Experimental Validation Protocol

CFD simulations require rigorous validation against experimental data to ensure predictive accuracy.

Single Particle Validation

- Experimental Reference: Compare with drying experiments for spherical wet coal particles

- Parameters: Monitor particle core temperature progression over time

- Target: Achieve close agreement between predicted and measured temperature profiles [3]

Industrial System Validation

- Velocity Measurements: Use anemometry to measure airflow velocity distribution in drying chambers

- Acceptance Criteria: Maintain relative error less than 10% between simulation and experimental results [1]

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate coefficient of nonuniformity of airflow velocity (target: <10% after optimization) [1]

Application to Drying Chamber Design

CFD simulation enables optimization of drying chamber geometry for industrial applications through systematic analysis.

Chamber Optimization Protocol

- Base Model Development: Create simplified CAD model of drying chamber, removing non-essential components

- Geometric Modifications:

- Test various airflow path geometries

- Evaluate additional air guides

- Optimize inlet perforation distribution [1]

- Flow Uniformity Target: Achieve air velocity of at least 1 m/s in proximity to dried materials [1]

Performance Outcomes

- Successful Implementation: Optimized designs can reduce drying time by 50% with simultaneous reduction in energy consumption [1]

- Validation: Final designs require experimental verification through velocity measurements in the manufactured system [1]

In the computational modeling of biomass drying processes, the governing equations for mass, momentum, and energy conservation form the fundamental mathematical framework that describes the underlying physics. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) leverages these equations to simulate complex multiphase transport phenomena, enabling researchers to predict temperature distribution, moisture removal rates, and airflow patterns within drying systems [7] [8]. For biomass drying applications—ranging from agricultural grain drying to advanced pyro-gasification processes—accurately implementing these equations is crucial for optimizing dryer design, improving energy efficiency, and preserving product quality [9] [10]. This document establishes standardized application notes and protocols for implementing these governing equations within the specific context of biomass drying research, providing a reproducible framework for scientific investigation.

Fundamental Governing Equations in CFD

The foundation of any CFD simulation lies in solving a set of partial differential equations that govern the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy. These principles are universally applicable across various fluid flow and heat transfer scenarios, including biomass drying systems.

Mass Conservation (Continuity Equation)

The continuity equation states that mass cannot be created or destroyed within a closed system. For a fluid flow, the rate of mass entering a control volume equals the rate of mass exiting it, plus any mass accumulation within the volume.

The general form of the continuity equation is: [ \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v}) = 0 ] where ( \rho ) is the fluid density (( \text{kg/m}^3 )), ( t ) is time (s), and ( \vec{v} ) is the velocity vector (m/s).

In the context of porous media or biomass drying, where moisture transfer occurs, additional source terms may be incorporated to account for mass transfer between phases. During drying, the evaporation of moisture from the biomass surface or interior represents a critical mass transfer process that must be accurately modeled [10].

Momentum Conservation (Navier-Stokes Equations)

The momentum conservation equations, also known as the Navier-Stokes equations, describe how the velocity field of a fluid evolves under the influence of internal and external forces.

The general form of the momentum equation is: [ \frac{\partial (\rho \vec{v})}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v} \vec{v}) = -\nabla p + \nabla \cdot (\mu \nabla \vec{v}) + \rho \vec{g} + \vec{F} ] where ( p ) is the static pressure (Pa), ( \mu ) is the dynamic viscosity (Pa·s), ( \vec{g} ) is the gravitational acceleration vector (m/s²), and ( \vec{F} ) represents additional body forces (N/m³).

In biomass drying applications, these equations model airflow patterns around and through biomass particles, directly influencing convective heat and mass transfer rates. For systems involving particle-scale analysis, such as fluidized bed dryers, the Eulerian-Lagrangian approach incorporating the Discrete Element Method (CFD-DEM) is often employed to resolve individual particle motions and interactions [11].

Energy Conservation

The energy conservation equation, derived from the first law of thermodynamics, governs heat transfer within the system, including conduction, convection, and radiation.

The general form of the energy equation is: [ \frac{\partial (\rho h)}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v} h) = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + Sh ] where ( h ) is the specific enthalpy (J/kg), ( k ) is the thermal conductivity (W/m·K), ( T ) is the temperature (K), and ( Sh ) represents volumetric heat sources (W/m³).

In drying applications, the energy equation is coupled with mass transfer phenomena, as energy provides the latent heat required for moisture evaporation. The temperature distribution within both the drying medium and the biomass itself critically determines drying rates and efficiency [10] [8].

Table 1: Governing Equations for CFD Simulation of Biomass Drying

| Conservation Principle | Governing Equation | Key Variables | Role in Biomass Drying |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass | (\frac{\partial \rho}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v}) = S_m) | (\rho): Density, (\vec{v}): Velocity vector, (S_m): Mass source | Models airflow and moisture transport/evaporation [10] |

| Momentum | (\frac{\partial (\rho \vec{v})}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v} \vec{v}) = -\nabla p + \nabla \cdot (\mu \nabla \vec{v}) + \rho \vec{g} + \vec{F}) | (p): Pressure, (\mu): Viscosity, (\vec{g}): Gravity, (\vec{F}): Body forces | Predicts airflow patterns and velocity profiles around biomass [11] [8] |

| Energy | (\frac{\partial (\rho h)}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v} h) = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + S_h) | (h): Enthalpy, (k): Thermal conductivity, (T): Temperature, (S_h): Heat source | Calculates temperature distribution and heat transfer for evaporation [10] [8] |

Application in Biomass Drying: Protocols and Implementation

Workflow for CFD Modeling of Biomass Drying

The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for developing and validating CFD models of biomass drying systems, from problem definition to results validation.

Diagram 1: CFD modeling workflow for biomass drying systems, showing the sequential stages from problem definition to analysis.

Protocol 1: Implementing Governing Equations for Convective Drying

This protocol provides detailed methodology for setting up and solving the governing equations for a convective hot air drying process, commonly used in grain drying applications [10].

Objective: To simulate the convective drying of biomass in a packed or fluidized bed using CFD.

Experimental Setup:

- Dryer Type: Convective hot air dryer

- Biomass Material: Agricultural grains (e.g., wheat, maize) or agave bagasse [4]

- Drying Conditions: Temperature range: 40-120°C; Air velocity: 0.5-2.0 m/s

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Geometry Creation:

- Create a 2D or 3D computational domain representing the drying chamber.

- Include inlet, outlet, and boundaries representing biomass surfaces.

- For porous media approaches, define the biomass region with appropriate porosity.

Mesh Generation:

- Generate a structured or unstructured mesh with sufficient refinement near biomass surfaces to resolve boundary layers.

- Perform grid independence study to ensure solution accuracy.

Physics Setup - Governing Equations with Source Terms:

- Mass Conservation: Enable species transport to model moisture transfer. Include a source term for evaporation rate derived from drying kinetics.

- Momentum Conservation: Implement porous media model if treating biomass as a porous zone. Include resistance coefficients to account for pressure drop through the biomass bed.

- Energy Conservation: Couple energy equations with mass transfer to account for latent heat of vaporization. Implement temperature-dependent thermal properties.

Boundary Conditions:

- Inlet: Specify air velocity, temperature, and humidity ratio.

- Outlet: Set pressure outlet condition.

- Walls: Apply appropriate thermal conditions (adiabatic, constant heat flux, or convective).

- Biomass Surfaces: Define moisture content initial conditions and evaporation models.

Solver Settings:

- Select pressure-based solver.

- Use coupled scheme for pressure-velocity coupling.

- Set discretization schemes (second-order upwind recommended).

- Establish convergence criteria (typically 10⁻⁶ for energy, 10⁻⁵ for other variables).

Protocol 2: CFD Model Validation Against Experimental Data

This protocol outlines the procedure for validating CFD predictions of biomass drying using experimental measurements, essential for establishing model credibility [4] [12].

Objective: To validate CFD-predicted temperature, velocity, and moisture profiles against experimental data.

Experimental Setup:

- Instrumentation: Thermocouples, anemometers, humidity sensors, moisture analyzer

- Data Acquisition: Automated system for continuous monitoring

- Validation Metrics: Temperature distribution, airflow velocity, moisture content

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Experimental Data Collection:

- Conduct drying experiments under controlled conditions matching CFD boundary conditions.

- Measure temperature at multiple locations within the drying chamber using thermocouples.

- Record air velocity patterns using anemometry or Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) [12].

- Periodically sample biomass to determine moisture content evolution.

CFD Simulation Under Identical Conditions:

- Implement the same geometry, boundary conditions, and initial conditions as the experimental setup.

- Run simulation to steady-state for airflow patterns and transient for drying evolution.

Quantitative Comparison:

- Extract CFD results at identical locations to experimental measurement points.

- Compare temperature, velocity, and moisture content profiles.

- Calculate statistical metrics: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), and correlation coefficient (R²).

Model Calibration:

- If discrepancies exceed acceptable thresholds (e.g., >10% deviation), calibrate model parameters.

- Adjust empirical coefficients in evaporation rate equations or porous media resistance models.

- Iterate until satisfactory agreement is achieved.

Table 2: Key Parameters for CFD Model Validation in Biomass Drying

| Parameter | Measurement Technique | CFD Output | Acceptable Deviation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Thermocouples, IR sensors | Contour plots, point values | ±5°C | Verification of heat transfer modeling [8] |

| Air Velocity | Anemometry, PIV [12] | Velocity vectors, streamlines | ±10% | Validation of momentum transport and flow patterns [8] [12] |

| Moisture Content | Gravimetric analysis, moisture analyzer | Contour plots, average values | ±5% (dry basis) | Validation of mass transfer and drying kinetics [10] |

| Gas Composition | Gas chromatography | Species concentration | ±3 vol.% | Pyro-gasification processes [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for CFD in Biomass Drying

| Item | Function | Application Example | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CFD Software (COMSOL) | Multi-physics simulation platform | Micro-scale mass and heat transfer phenomena in pyro-gasification | [4] |

| CFD Software (ANSYS Fluent) | General-purpose CFD solver | Airflow and thermal analysis in indirect solar dryers | [8] |

| Process Simulator (Aspen Plus) | Process modeling and simulation | Macro-scale process insights and thermodynamic analysis | [4] |

| Discrete Element Method (DEM) | Particle-scale modeling | CFD-DEM coupling for dense gas-solid reacting flows | [11] |

| Agave Bagasse Biomass | Model feedstock for validation | Pyro-gasification studies under controlled conditions | [4] |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer | Experimental kinetics data | Determination of reaction kinetics for model input | [4] |

| Particle Image Velocimetry | Flow field validation | Experimental measurement of velocity profiles for CFD validation | [12] |

Advanced Implementation: Coupled Heat and Mass Transfer

In biomass drying systems, heat and mass transfer processes are intrinsically coupled and must be solved simultaneously for accurate predictions.

Mathematical Framework for Coupled Phenomena

The coupled heat and mass transfer during drying can be described by the following equations [10]: [ \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \alphaT \nabla^2 T ] [ \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = \alphaC \nabla^2 C ] where ( \alphaT ) is the thermal diffusivity (m²/s), ( \alphaC ) is the mass diffusivity (m²/s), and ( C ) is the moisture concentration (kg/m³).

The moisture migration during drying is typically described by Fick's law of diffusion [10]: [ J = -D \frac{\partial C}{\partial x} ] where ( J ) is the diffusion flux (kg/m²·s), ( D ) is the mass diffusion coefficient (m²/s), and ( \frac{\partial C}{\partial x} ) is the moisture concentration gradient (kg/m³·m).

Protocol 3: Implementing Multiphase Models for Pyro-Gasification

This protocol extends the governing equations to more complex scenarios involving thermochemical conversion processes like pyro-gasification.

Objective: To simulate coupled pyrolysis and gasification processes incorporating reaction kinetics.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Reaction Mechanism Definition:

- Implement global reaction kinetics for biomass decomposition.

- Include homogeneous gas-phase reactions and heterogeneous char reactions.

Species Transport Equations:

- Solve conservation equations for each chemical species: [ \frac{\partial (\rho Yi)}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\rho \vec{v} Yi) = -\nabla \cdot \vec{J}i + Ri ] where ( Yi ) is the mass fraction of species ( i ), ( \vec{J}i ) is the diffusion flux, and ( R_i ) is the net rate of production.

Energy Equation with Reaction Source:

- Include heat of reaction terms in the energy equation: [ Sh = -\sum \Delta H{rxn} \cdot Ri ] where ( \Delta H{rxn} ) is the enthalpy of reaction.

Turbulence-Chemistry Interaction:

- Select appropriate turbulence-chemistry interaction model (e.g., finite-rate/eddy-dissipation).

- Account for the effect of turbulent fluctuations on reaction rates.

Diagram 2: Relationship between governing equations and physical mechanisms in biomass drying systems, showing how conservation principles translate to practical applications.

The governing equations for mass, momentum, and energy conservation provide the fundamental framework for simulating biomass drying processes using CFD. The protocols outlined in this document establish standardized methodologies for implementing these equations, validating model predictions, and applying them to both conventional drying and advanced thermochemical conversion systems. By adhering to these application notes and protocols, researchers can ensure reproducible, accurate simulations that advance the field of biomass drying optimization and contribute to more sustainable and efficient industrial processes.

In the broader context of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) research for biomass drying simulations, understanding multiphase transport is fundamental to optimizing process efficiency and product quality. Biomass thermochemical conversion processes, including gasification and pyrolysis, are significantly influenced by the complex interactions between the solid biomass matrix, liquid water, and gaseous phases [13] [7]. These interactions govern critical operational parameters such as drying kinetics, reaction rates, and ultimately, the composition of the synthesis gas (syngas) produced [13]. CFD has emerged as a vital modeling tool, enabling researchers to simulate these complex multiphase systems virtually, thereby reducing reliance on costly and time-consuming experimental pilot plants [13] [14] [7]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for simulating multiphase transport in biomass, with a specific focus on integrating these models into a comprehensive CFD framework for biomass drying and conversion.

Key Parameters in Multiphase Biomass Transport

The efficiency of biomass conversion processes and the composition of the resulting syngas are governed by several key physical and operational parameters. A thorough understanding of these factors is essential for accurate CFD model setup and validation. The table below summarizes the quantitative impact of critical biomass properties, as identified from experimental studies.

Table 1: Key Biomass Properties and Their Impact on Gasification Efficiency and Syngas Composition

| Parameter | Variation | Impact on Gasification Efficiency | Impact on Syngas H₂ Content | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water Content | Increase from 20% to 40% | Decrease by ~10% | Reduction | [13] |

| Temperature | Increase from 700°C to 900°C | Increase by ~20% | Decrease from 25% to 20% | [13] |

| Particle Size | Decrease from 1 mm to 0.5 mm | Increase by ~20% | Increase | [13] |

These parameters are critical for developing accurate sub-models within CFD software. For instance, particle size directly influences the surface-area-to-volume ratio, affecting heat and mass transfer rates, while moisture content dictates the energy required for the initial drying phase [13].

CFD Modeling Workflow and Experimental Protocols

The CFD modeling of multiphase biomass transport involves a structured workflow that integrates pre-processing, solving, and post-processing. The following protocol outlines the key steps for setting up and validating a simulation, such as for a downdraft gasifier or a drying process.

Protocol: CFD Model Setup for Biomass Gasification/Drying

Objective: To simulate the multiphase flow, heat transfer, and reaction kinetics within a biomass conversion reactor. Primary Software: ANSYS Fluent or OpenFOAM [13].

Methodology:

Geometry Creation and Mesh Generation (Pre-processing):

- Create a 2D or 3D computational domain representing the reactor geometry (e.g., downdraft gasifier with a throat/nozzle design) [13].

- Generate a high-quality mesh, ensuring sufficient resolution in critical regions like the nozzle and reaction zones. A mesh independence study must be conducted to ensure results are not grid-dependent.

Model Selection and Setup:

- Multiphase Model: Select the Dense Discrete Phase Model (DDPM) within ANSYS Fluent to simulate the discrete biomass particles moving through the continuous gas phase [13].

- Turbulence Model: Use standard k-ε or other appropriate models to capture turbulent flow.

- Species Transport: Enable the species transport model to simulate the evolution of chemical species (CO, CO₂, H₂, CH₄, H₂O, light hydrocarbons, tars) [13].

- Heterogeneous Reactions: Define reaction kinetics for solid-phase reactions (e.g., char oxidation). Use simplified, lumped global apparent kinetics suitable for reactor-scale simulation, such as those dividing products into biochar, bio-oil, and bio-gas [7].

- Homogeneous Reactions: Define gas-phase reaction kinetics for volatile combustion and reforming reactions.

Boundary and Initial Conditions:

- Inlet: Specify the velocity or mass flow rate of the gasification agent (e.g., air, steam).

- Inlet (Discrete Phase): Define the biomass feed rate, particle size distribution, and moisture content (see Table 1 for typical values).

- Walls: Set appropriate thermal conditions (e.g., adiabatic, fixed temperature, or heat flux).

- Outlet: Define a pressure outlet boundary condition.

Solution and Calculation:

- Initialize the flow field and begin iteration using a pressure-based solver.

- Employ user-defined functions (UDFs) if necessary to couple complex particle-scale models with the reactor-scale simulation, achieving a multi-scale modeling approach [13].

Model Validation:

- Validate the CFD model by comparing simulation results with experimental data from a pilot plant.

- Key validation metrics include syngas composition (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄), temperature profile along the reactor, and producer gas yield [7].

- A well-validated model should show good consistency with experimental data within a feasible computational time frame [13].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and the key interactions between the sub-models in this protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimental and computational analysis of multiphase biomass transport relies on a set of essential tools and reagents. The following table details key components for a research program in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biomass Transport Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ANSYS Fluent | Commercial CFD software for simulating fluid flow, heat transfer, and reactions. | Enables use of Dense Discrete Phase Model (DDPM) and UDFs for multi-scale modeling of reactor systems [13]. |

| OpenFOAM | Open-source CFD software package for customized simulations. | Offers flexibility for modeling complex chemical engineering fluid dynamics in reactors [13]. |

| MFiX (Multi-phase Flow with Interphase eXchanges) | Open-source software for multi-scale CFD simulations, particularly of fluidized beds. | Supports Eulerian-Eulerian and Eulerian-Lagrangian approaches for modeling fluid-particle interactions [7]. |

| Lumped Kinetic Model | Simplified reaction kinetics scheme for reactor-scale CFD. | Divides pyrolysis products into biochar, bio-oil, and bio-gas; essential for feasible computation [7]. |

| Downdraft Gasifier (Throat Design) | Experimental reactor system for model validation. | Features a narrowed throat (nozzle) to improve mixing and reaction efficiency; produces low-tar syngas [13]. |

| Non-Newtonian Viscosity Model | Describes the rheology of complex food/biomass fluids in processes like extrusion. | Critical for accurate simulation of mechanical processing operations where biomass behaves as a non-Newtonian fluid [14]. |

Advanced Application: Integrating Drying with Downstream Conversion

In a comprehensive CFD thesis, the drying model should not be developed in isolation but integrated with subsequent thermochemical processes like pyrolysis and gasification. The initial drying phase, where liquid water is converted to vapor, is a critical first step that consumes significant energy and influences the entire process chain [13] [14]. For instance, in a downdraft gasifier, the biomass moves downward through sequential zones of drying, devolatilization, and reduction [13]. A multiphase CFD model can track this progression, resolving gradients within the reactor and even within individual particles [13]. The protocol below outlines how to implement this integrated analysis.

Protocol: Coupled Drying and Gasification Simulation

Objective: To simulate the sequential stages of biomass conversion in a downdraft gasifier, from initial drying to final syngas production.

Methodology:

- Reactor Geometry: Utilize a downdraft gasifier geometry with a throat/nozzle design. Radially distributed nozzles in the throat area are conduits for secondary air, initiating oxidation and increasing bed temperature [13].

- Sequential Sub-models: Implement the following sub-models to represent the sequential conversion stages. These stages occur as the biomass and syngas move downward through the reactor [13]:

- Drying Zone: Water evaporates from the biomass, cooling the inlet and ensuring no hot spots.

- Devolatilization Zone: Due to heating, the biomass releases volatile gases (CO, CO₂, H₂, CH₄, H₂O, tars).

- Oxidation Zone: Char and volatiles are partially oxidized, releasing heat and increasing temperatures above 400°C, which disintegrates tars [13].

- Reduction Zone: In the absence of oxygen, endothermic gasification reactions (e.g., water-gas shift, Boudouard) occur, producing the final syngas.

- Analysis: Use the solved model to analyze temperature profiles, species concentration (especially H₂ and CO), and the effect of key parameters from Table 1 (e.g., how initial moisture content impacts the energy balance and final syngas composition).

The following workflow diagram maps the sequential stages of biomass conversion within a downdraft gasifier, which must be captured in a coupled simulation.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has become a cornerstone in the modeling and optimization of biomass drying processes, a critical unit operation in food engineering, pharmaceuticals, and biofuel production. Drying is a complex, multi-physics phenomenon involving simultaneous heat, mass, and momentum transfer across different spatial and temporal scales [15]. At the macro-scale, environmental conditions within a dryer, such as air velocity, temperature, and humidity, govern the overall process efficiency. At the micro-scale, within the biomass particle itself, moisture diffusion, cellular water transport, and structural changes determine the final product quality [15]. This multiscale nature presents a significant modeling challenge, as phenomena at each level are intrinsically linked.

The adaptability of CFD to model diverse flow processes with high spatial and temporal resolution facilitates an in-depth understanding of these transfers [16]. By simulating a range of complex flow problems, CFD complements traditional experimental and analytical approaches, enabling researchers to visualize and quantify parameters that are difficult to measure experimentally [16] [15]. This capability is crucial for advancing the design of drying systems, reducing energy consumption—which accounts for 12–20% of industrial energy use in developed nations—and preserving the quality and safety of dried products [15]. The following sections detail the fundamental principles, modeling protocols, and practical applications of multiscale CFD analysis for biomass drying.

Fundamental Principles of Multiscale CFD in Drying

A multiscale CFD approach for biomass drying integrates distinct yet interconnected models that operate at different spatial domains, from the entire dryer down to the cellular structure of a single biomass particle.

Dryer Scale (Macro-Scale): At this level, the focus is on the global environment within the drying chamber. The model solves the conservation equations for the continuous gas phase (drying air) to predict bulk flow patterns, temperature distribution, and humidity fields. This provides the boundary conditions (e.g., surface temperature, convective flux) for the particle-scale model.

Particle Scale (Meso-Scale): This scale models an individual biomass particle. It uses the boundary conditions from the dryer-scale model to solve for internal heat and moisture transfer. Key outputs include the particle's core temperature, moisture content distribution, and shrinkage behavior.

Cellular/Tissue Scale (Micro-Scale): This is the finest scale, which investigates the transport phenomena at the cellular level. It considers the complex microstructure of the biomass, including cell walls and pores, to model the fundamental mechanisms of liquid water and vapor transport. The properties determined here (e.g., effective diffusivity) inform the constitutive laws used in the particle-scale model.

Table 1: Key Governing Equations for Multiscale Drying CFD Models

| Scale | Governing Equations | Key Variables | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dryer (Macro) | Navier-Stokes, Energy, Species Transport | Velocity (u), Pressure (P), Temperature (T), Concentration (C) | Predicts bulk airflow, heat transfer, and humidity distribution in the dryer chamber. |

| Particle (Meso) | Energy, Mass (Moisture) Diffusion | Temperature (T), Moisture Content (M), Effective Diffusivity (D∗) | Simulates internal heat and moisture transfer within a single biomass particle. |

| Cellular (Micro) | Pore Network Models, Fickian Diffusion | Micro-Porosity, Cell Wall Permeability, Water Activity | Describes liquid and vapor moisture transport through the complex cellular structure of the biomass. |

The coupling between these scales is achieved through boundary conditions and property exchange. For instance, the temperature and humidity field from the dryer-scale simulation defines the convective boundary condition at the surface of a biomass particle. The particle-scale model, in turn, calculates the local moisture evaporation rate, which serves as a mass source term for the gas-phase species transport equation in the dryer-scale model [16] [15]. Similarly, effective properties like moisture diffusivity ((D^*)), which is strongly dependent on the material's microscopic pore structure and temperature, are often determined from micro-scale models or experiments and used as input for the particle-scale model [16].

Application Notes: Implementing a Multiscale CFD Drying Model

Workflow for a Coupled Simulation

A systematic workflow is essential for implementing a robust multiscale drying simulation. The following diagram outlines the logical sequence and data exchange between the different modeling scales.

Key Modeling Considerations and Best Practices

- Geometry and Mesh: For the dryer scale, a conformal mesh is sufficient. For the particle scale, a detailed geometry that includes key features is crucial. Mesh sensitivity analysis must be performed at all scales to ensure results are independent of grid size [16].

- Material Properties: Accurately defining temperature- and moisture-dependent properties (e.g., thermal conductivity, specific heat, diffusivity) is one of the most significant challenges. Use experimental data or validated correlations wherever possible [15].

- Turbulence and Multiphase Flow: Selecting an appropriate turbulence model (e.g., k-ε) is vital for accurately capturing the dryer airflow. For systems like fluidized bed dryers, a multiphase model (Eulerian-Eulerian or CFD-DEM) is required to simulate the solid-gas interactions [17].

- Solver Settings: Use a pressure-based coupled solver for better convergence. Second-order discretization schemes for momentum, energy, and species transport are recommended for higher accuracy.

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

CFD models are powerful, but their predictions must be validated against experimental data to ensure reliability. The following protocol outlines a standard method for collecting validation data for a convective drying process.

Protocol 1: Determination of Drying Kinetics and Moisture Diffusivity

1.1 Objective: To experimentally determine the drying kinetics and effective moisture diffusivity of a biomass sample for the purpose of validating a multiscale CFD model.

1.2 Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Fresh Biomass Sample (e.g., anchovies, wood chips, algae) | The core material whose drying behavior is under investigation. |

| Laboratory Convective Oven / Solar Dryer | Provides controlled drying conditions (temperature, air velocity, humidity). |

| Analytical Balance (±0.001 g) | Measures mass loss of the sample at regular intervals to track moisture ratio. |

| Data Logging Thermocouples / Hygrometers | Monitors real-time temperature and relative humidity at critical locations in the dryer and within the sample. |

| Image Analysis System | Quantifies particle shrinkage and structural changes during drying. |

1.3 Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare biomass samples of uniform size and shape. Record the initial mass ((mo)), dimensions, and initial moisture content ((Mo)).

- Experimental Setup: Place the sample in the drying apparatus (e.g., tray in a convective oven). Install sensors to record the drying air temperature ((T)), relative humidity, and velocity.

- Drying Experiment: Commence drying at the desired operating conditions. At predetermined time intervals, quickly remove and weigh the sample to record its mass ((m_t)). Return the sample to the dryer immediately. Repeat until mass equilibrium is reached (i.e., no further mass loss).

- Data Processing:

- Calculate the Moisture Ratio (MR) at each time point: ( MR = (Mt - Me)/(Mo - Me) ), where (Mt) is the moisture content at time (t), and (Me) is the equilibrium moisture content.

- Fit the experimental MR data to thin-layer drying models (e.g., Henderson and Pabis, Midilli et al.) to obtain a mathematical description of the drying kinetics [18].

- Determination of Effective Moisture Diffusivity ((D{eff})): For a thin-layer geometry, (D{eff}) can be estimated from the slope ((K)) of a linearized drying curve (ln(MR) vs. time) using Fick's second law of diffusion, often simplified for long drying times: ( MR = A \exp(-K \cdot t) ). The value of (D_{eff}) is then derived from (K) [18]. Reported values for anchovies, for example, range from ~6.4e-10 to 1.02e-09 m²/s depending on the drying method [18].

1.4 Data Integration with CFD: The experimentally determined moisture ratio curve and effective moisture diffusivity serve as direct validation targets for the particle-scale model within the multiscale CFD simulation. The CFD-predicted moisture loss over time and the spatial moisture distribution within a virtual particle should align with these experimental findings.

Advanced Modeling: Integrating Reaction Kinetics

For many biomass types, drying is merely the first step in a thermochemical conversion process, such as gasification or combustion. In these cases, the CFD model must integrate drying with subsequent reaction stages. The following diagram illustrates the sequential nature of these processes in a comprehensive model, such as for a fluidized bed gasifier.

The kinetics for each stage are modeled differently. The drying rate can be expressed as an Arrhenius-type equation [17]: ( rd = 5.13 \times 10^{10} \exp(-10585/Tp) X ) where (X) is the moisture mass per kilogram of biomass, and (T_p) is the particle temperature.

Devolatilization (pyrolysis) follows drying, releasing volatile gases, and is often modeled using competing multi-step reaction schemes. Finally, the remaining char undergoes heterogeneous reactions with surrounding gases (combustion and gasification) [17] [19]. Integrating these kinetics into a CFD-DEM (Discrete Element Method) framework allows for a high-fidelity simulation of reactive biomass particles in systems like fluidized beds, tracking individual particle histories and their interactions with the gas phase and other particles [17].

Multiscale CFD analysis provides an unparalleled framework for deconstructing and understanding the intricate phenomena in biomass drying. By systematically bridging the dryer, particle, and cellular scales, researchers and engineers can move beyond empirical correlations to a physics-based design and optimization paradigm. This approach not only predicts overall dryer performance but also illuminates the internal state of the biomass, enabling strategies to enhance drying efficiency, reduce energy consumption, and ultimately preserve critical product quality attributes. The integration of experimental protocols for validation ensures the model's fidelity, making CFD an indispensable tool in the advancement of sustainable and efficient drying technologies for biomass processing.

In computational fluid dynamics (CFD) for biomass drying simulation research, accurately modeling the process hinges on a precise understanding of key biomass properties. Porosity, permeability, and temperature-dependent parameters govern the complex, multi-physics phenomena of heat and mass transfer during drying. These properties are not constants; they dynamically change with temperature and the physical transformation of the biomass structure itself, influencing moisture transport, heating rates, and final product quality. This application note details the critical property data and experimental protocols necessary to parameterize and validate robust CFD models for biomass drying.

Quantitative Property Data for CFD Modeling

The following tables summarize essential quantitative data for key biomass properties, compiled from experimental and modeling studies.

Table 1: Typical Porosity and Permeability Ranges of Biomass Materials

| Biomass Type / System | Porosity (ε) | Permeability (κ) | Notes / Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wood Particle (General) | ~80-90% [20] | Model-dependent | Comprises 40-50% cellulose, 10-30% hemicellulose, 10-30% lignin. |

| Porous Media with Non-motile Biofilm | - | Reduction of 94% ± 4% [21] | Causes severe clogging of pore space. |

| Porous Media with Motile Biofilm | - | Reduction of 78% ± 7% [21] | Motility limits spatial accumulation, less reduction. |

| Biomass Feedstock (General) | Considered in models [2] [17] | Anisotropic [22] | Particle permeability is a complex, direction-dependent property. |

Table 2: Temperature-Dependent Parameters in Biomass Thermal Conversion

| Parameter | Value / Expression | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Drying Temperature Range | 370 K - 430 K [17] | Biomass gasification process. |

| Drying Rate ((r_d)) | ( rd = 5.13 \times 10^{10} \exp\left(-\frac{10585}{Tp}\right) X ) [17] | Evaporation rate of moisture from a biomass particle; (T_p) is particle temperature (K), (X) is moisture mass per kg biomass. |

| Devolatilization Rate (1-step) | ( k = A \exp(-E_a / RT) ) [22] | Single-step global devolatilization reaction kinetic rate. |

| Fast Pyrolysis Temperature | Moderate (~500 °C) [22] | Aimed at producing bio-oil and chemicals. |

Experimental Protocols for Property Characterization

Protocol: Microfluidics for Biomass-Induced Permeability Reduction

Objective: To quantify how microbial biomass growth and spatial organization alter the intrinsic permeability of a porous structure under a constant pressure gradient.

Background: This protocol is adapted from porous media research, which has demonstrated that spatial organization of biomass, not just total amount, is the primary factor controlling permeability [21].

Materials:

- Microfluidics Device: A chip designed as a porous media analog (e.g., with a random distribution of vertical cylinders).

- Pressure Control System: Capable of imposing a constant macroscopic pressure drop (e.g., ElveFlow OBI-1).

- Fluid Delivery System: For continuous injection of nutrient medium.

- Analytical Scale: To monitor effluent flow rate at the outlet over time.

- Time-Lapse Microscopy System: For visualizing biomass distribution within the pore space.

Procedure:

- Porous Structure Characterization: Prior to inoculation, characterize the clean chip's intrinsic permeability using Darcy's law by applying a known pressure drop and measuring the resulting flow rate.

- System Inoculation: Infect the device with a prepared bacterial suspension.

- Continuous Flow Operation: Switch to a continuous injection of a sterile nutrient solution. Maintain a constant pressure drop across the device for the experiment's duration.

- Data Acquisition:

- Continuously monitor the fluid flow rate at the outlet using the analytical scale. The permeability at any time ( t ) is proportional to this flow rate under constant pressure conditions.

- Use time-lapse microscopy to capture the spatial distribution and accumulation of biomass within the pore network over time.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the normalized permeability as a function of time.

- Correlate the degree of permeability reduction with the observed biomass spatial patterns (e.g., uniform clogging vs. localized accumulation).

Protocol: Calibrating Drying Models via Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Objective: To obtain experimental data on mass loss and temperature profiles during biomass drying for validating and calibrating drying sub-models in CFD.

Background: TGA provides precise measurement of mass change as a function of temperature or time, which is fundamental for characterizing the drying stage of biomass thermal conversion [2] [4].

Materials:

- Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA)

- Biomass Sample: Dried and milled to a uniform particle size (e.g., 0.1-1 mm).

- Inert Gas Supply: (e.g., Argon, Nitrogen) for non-oxidative environments.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dry the biomass sample at 105 °C for 24 hours to establish a dry-weight baseline. Mill and sieve to achieve a consistent particle size.

- Experiment Setup: Load a small, precise mass of the prepared sample into the TGA crucible.

- Temperature Program:

- Non-Isothermal Drying: Heat the sample from ambient temperature to a high temperature (e.g., 700-1000 °C) at a constant heating rate (e.g., 20 °C/min) under an inert gas atmosphere.

- Isothermal Drying: Rapidly heat the sample to a target drying temperature (e.g., 900 °C or 950 °C) and hold for a defined period.

- Data Acquisition: Continuously record the sample mass, temperature, and time throughout the experiment.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot mass loss (or moisture content) versus temperature or time.

- Use the data to fit parameters for drying models, such as the Arrhenius-type rate equation, by determining the activation energy ((E_a)) and pre-exponential factor ((A)) that best match the experimental mass loss profile.

Visualization of Workflows and Modeling Approaches

Biomass Drying and Conversion Workflow

Multiscale CFD Modeling Approach for Biomass

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Biomass Permeability and Drying Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Microfluidic Porous Chips | Serves as a transparent, well-defined analog for natural porous media (e.g., soils, filters) to study biomass-flow interactions. | Chip with random cylinder arrangement (pore sizes 0.01-0.2 mm) [21]. |

| Precision Pressure Controller | Imposes and maintains a constant pressure gradient across the porous medium, mimicking in-situ conditions. | ElveFlow OBI-1 [21]. |

| Pseudomonas putida Strains | Model soil bacteria used to study the impact of microbial motility on biomass spatial organization and clogging. | Wild-type (motile) and ΔfliC mutant (non-motile) strains [21]. |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzer (TGA) | Precisely measures mass loss as a function of temperature/time, critical for calibrating drying and devolatilization kinetics. | Used for non-isothermal and isothermal analysis [4]. |

| CFD Software Packages | Provides the simulation environment for modeling complex reactor hydrodynamics, heat transfer, and chemical reactions. | ANSYS Fluent, COMSOL Multiphysics, MFiX, OpenFOAM [13] [7] [4]. |

Current Challenges in Modeling Complex Biomass Drying Behavior

Biomass drying is a critical preprocessing step in the conversion of biomass to biofuels and valuable chemicals, directly impacting the efficiency and cost of subsequent thermochemical processes like pyrolysis and gasification [13] [7]. The high moisture content of raw biomass feedstocks can lead to increased boiler heat loss, material corrosion, and reduced overall thermal efficiency during combustion and conversion [23]. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has emerged as a powerful tool for simulating and optimizing these complex drying processes, offering a cost-effective method for predicting key parameters such as temperature distribution, moisture content, and gas-flow patterns [13] [7]. However, accurately modeling biomass drying presents significant challenges due to the complex multiphase physics, the heterogeneous nature of biomass, and the intricate coupling between heat transfer, mass transfer, and fluid dynamics [24] [13]. This application note details the primary challenges in modeling biomass drying behavior and provides standardized protocols for experimental validation, specifically framed within broader CFD research for biomass drying simulation.

Current Challenges in CFD Modeling of Biomass Drying

The modeling of biomass drying using CFD is fraught with complexities that stem from the intrinsic properties of biomass and the multifaceted nature of the drying process itself. The table below summarizes the core challenges and their specific impacts on model fidelity.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Computational Modeling of Biomass Drying

| Challenge Category | Specific Modeling Hurdle | Impact on Simulation Accuracy & Practicality |

|---|---|---|

| Multiphase Physics | Coupling of heat transfer, mass transfer, and fluid flow in a porous media [24] [13]. | High computational cost; simplified models may fail to capture critical phenomena like the movement of the drying front [24]. |

| Biomass Heterogeneity | Variability in composition, particle size, shape, and initial moisture distribution [13] [25]. | A "one-model-fits-all" approach is ineffective; requires extensive characterization for each feedstock type [25]. |

| Reaction Kinetics & Sub-models | Implementation of accurate drying kinetics, devolatilization, and porous media models [13] [7]. | Inaccurate sub-models are a major source of error, leading to poor predictions of final moisture content and drying times [13]. |

| Experimental Validation | Difficulty in obtaining high-quality, spatially resolved experimental data for model validation [24]. | Without robust validation, the predictive capability of CFD models remains uncertain for scale-up and design [24] [7]. |

Essential Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

To address the validation challenge, consistent and detailed experimental methodologies are required. The following protocols provide a framework for generating reliable data for CFD model calibration and validation.

Protocol: Fixed-Bed Drying with Drying Zone Analysis

This protocol, adapted from bed drying studies, is designed to characterize the movement and shape of the drying front within a biomass bed, a critical parameter for validating CFD models of fixed-bed dryers [24].

1. Principle: A batch of wet biomass is dried by a controlled flow of heated air. Continuous temperature measurements throughout the bed are used to track the velocity and width of the drying zone, where the majority of moisture evaporation occurs. This data provides direct insight into the drying dynamics that a model must replicate [24].

2. Materials:

- Biomass Sample: e.g., wooden chips, peanut shells, or straw. Particle size and shape should be documented.

- Drying Apparatus: Cylindrical drying chamber (e.g., 0.25 m³ capacity) with a perforated base for air distribution.

- Air Handling System: Centrifugal fan, electrical air heater, and airflow measurement.

- Data Acquisition: Thermocouples (K-type recommended) positioned at multiple heights (e.g., top, middle, bottom) within the biomass bed and a data logger [24] [23].

3. Procedure: 1. Sample Preparation: Prepare biomass to a known, uniform initial moisture content (e.g., 40%). For woody biomass, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) Laboratory Analytical Procedure (LAP) for "Determination of Total Solids in Biomass" is recommended [25]. 2. Bed Loading: Load the wet biomass into the drying chamber to a specified bed height (e.g., 600 mm). Ensure uniform packing density. 3. Instrumentation: Insert thermocouples at designated height positions to monitor temperature profiles. 4. Drying Run: Initiate drying by activating the fan and heater. Set and maintain constant drying air temperature and velocity. 5. Data Recording: Continuously record temperatures from all thermocouples and the outlet air humidity at regular intervals until the bed is fully dried. 6. Final Moisture Analysis: Upon completion, take dry weight samples from the top, middle, and bottom of the bed to determine the final moisture content distribution [24].

4. Data Analysis:

- Drying Zone Velocity: Calculate the velocity at which the temperature front (drying zone) moves through the bed by analyzing the time taken for the temperature rise at successive thermocouples [24].

- Drying Zone Width: Determine the spatial extent of the active drying zone from the temperature profiles.

- Key Findings for Modeling: Studies using this method have shown that the drying zone velocity increases with increasing drying temperature and air velocity, while the zone width increases with air velocity and height position in the bed. These quantitative relationships are essential for validating the transport phenomena in a CFD model [24].

Protocol: Spherical Heat Carrier (SHC) Drying

This protocol describes a mixed direct-contact drying method using heated steel balls (SHCs), which is highly relevant for industrial processes utilizing waste heat. It provides data on rapid, high-heat-transfer drying [23].

1. Principle: High-moisture biomass is mixed with pre-heated spherical heat carriers in a stirred device. The intense direct contact and mixing result in rapid heat transfer and dewatering. The thermal efficiency and dewatering rate are key metrics for model validation [23].

2. Materials:

- Biomass Sample: e.g., peanut shells, straw, or woody debris.

- Spherical Heat Carriers: Solid steel balls (e.g., 12 mm diameter).

- Drying Device: A multi-layer mixed-drying device with an insulated stainless-steel main body, a variable-speed agitator, and a ventilation fan.

- Heating System: Muffle furnace for heating the SHCs to the target temperature (e.g., 1200°C).

- Measurement: Thermocouple, electronic balance, and stopwatch [23].

3. Procedure:

1. Sample Preparation: Adjust biomass moisture content to a specific level (e.g., 40%) and allow water to equilibrate for 24 hours.

2. SHC Heating: Heat a known mass of SHCs (m1) in a muffle furnace to the set temperature and hold for 10 minutes to ensure thermal uniformity.

3. Mixing and Drying: Quickly mix the hot SHCs with a known mass of wet biomass (m2) at a specified mass ratio (e.g., 2:1) within the drying device. Start the agitator immediately.

4. Process Monitoring: Record the temperature of the mixture in real-time.

5. Process Termination: Once the mixture temperature cools to 30°C, discharge the mixture and weigh the total mass (m3).

6. Analysis: Perform industrial analysis (moisture, ash, volatiles, fixed carbon) on the dried biomass [23].

4. Data Analysis:

- Material Dewatering Rate (MR): Calculate using the formula:

MR = (m2 - (m3 - m1)) / m2 * 100%[23]. - Drying Thermal Efficiency (DE): Calculate using the formula:

DE = (m2 - (m3 - m1)) * ΔH / (m1 * Ci * ΔT) * 100%, whereΔHis the latent heat of vaporization of water (2257 kJ/kg),Ciis the specific heat capacity of the SHC, andΔTis the temperature change of the SHC [23]. - Key Findings for Modeling: This method has been shown to effectively reduce moisture content and significantly promote combustion performance. The thermal efficiency and dewatering rate provide critical data for modeling direct-contact heat transfer and the phase change of water in a dynamic, mixed system [23].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomass Drying Experiments

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Spherical Heat Carriers (SHC) | Solid steel balls used as a medium for direct-contact heat transfer in mixed drying processes, often utilizing waste heat [23]. |

| K-Type Thermocouple | A temperature sensor for real-time monitoring of temperature profiles within a biomass bed or mixture during drying [24] [23]. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy | A rapid, non-destructive analytical technique for predicting the chemical composition and moisture content of biomass, correlated with wet chemical data [25]. |

| NREL Laboratory Analytical Procedures (LAPs) | A suite of standardized methods for the precise characterization of biomass, including total solids, extractives, and structural carbohydrates, essential for sample preparation and validation [25]. |

Workflow for CFD Model Development and Experimental Validation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, iterative process of developing a CFD model for biomass drying and validating it against experimental data.

CFD Model Development Workflow

The path to accurate and predictive CFD modeling of biomass drying is complex, requiring careful consideration of multiphase physics, biomass heterogeneity, and reaction kinetics. The challenges outlined in this document underscore the necessity of a disciplined, iterative approach that tightly couples model development with rigorous experimental validation. The standardized protocols for fixed-bed and SHC drying provide a foundation for generating the high-quality data essential for calibrating and verifying CFD models. By adhering to such structured methodologies and leveraging tools like the essential research reagents listed, researchers can enhance the reliability of their simulations, thereby accelerating the development of more efficient and cost-effective biomass drying technologies for bioenergy and biorefining applications.

CFD Modeling Approaches and Real-World Biomass Drying Applications

DEM-CFD Coupling for Discrete Particle Systems in Fluidized Beds

The coupling of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and the Discrete Element Method (DEM) has emerged as a fundamentally important method for studying dense gas-solid fluidized beds. This hybrid approach enables researchers to investigate complex multiphase flow phenomena with unprecedented detail by leveraging the complementary strengths of both methodologies. Within the DEM framework, the motion behavior of each individual particle is tracked based on Newton's laws of motion, while CFD qualitatively and quantitatively describes the fluid evolution process through the solution of volume-averaged Navier-Stokes equations [26]. This powerful combination has facilitated the discussion of fluidized beds across multiple scales—from small laboratory setups to large engineering systems—making it particularly valuable for biomass drying simulation research where understanding particle-level phenomena is crucial for process optimization.

The applicability of DEM-CFD coupling has been verified through multi-scale studies confirming its reliability for predicting particle motion in fluidized beds [26]. For biomass processing applications, this capability is essential because the drying, direct combustion, and thermochemical transformation of cylindrical biomass particles (CBPs) in fluidized beds are significantly influenced by their unique geometric structures and the resulting heat transfer characteristics [27]. The DEM-CFD approach provides a computational framework to capture these complex interactions, offering insights that are often difficult or impossible to obtain through experimental methods alone.

Core Mathematical Framework

Governing Equations for Fluid Phase

The gas phase in DEM-CFD simulations is treated as a continuous medium governed by the volume-averaged Navier-Stokes equations. The continuity equation ensures mass conservation:

[ \frac{\partial}{\partial t}(\varepsilonf \rhof) + \nabla \cdot (\varepsilonf \rhof \mathbf{u}) = 0 ]

The momentum equation accounts for forces acting on the fluid:

[ \frac{\partial}{\partial t}(\varepsilonf \rhof \mathbf{u}) + \nabla \cdot (\varepsilonf \rhof \mathbf{u} \mathbf{u}) = -\nabla p + \nabla \cdot (\varepsilonf \boldsymbol{\tau}) + \varepsilonf \rhof \mathbf{g} + \mathbf{F}s ]

where (\varepsilonf) represents the fluid volume fraction, (\rhof) is the fluid density, (\mathbf{u}) is the fluid velocity vector, (p) is pressure, (\boldsymbol{\tau}) is the viscous stress tensor, (\mathbf{g}) is gravity, and (\mathbf{F}_s) represents the momentum exchange with particles [27].

The thermal energy balance for the fluid phase is given by:

[ \frac{\partial \varepsilonf \rhof C{p,f} Tf}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\varepsilonf \rhof \mathbf{u} C{p,f} Tf) = \nabla \cdot (\varepsilonf kf \nabla Tf) - \frac{\sum{i=1}^n Q{fp}}{Vc} ]

where (C{p,f}) is the specific heat capacity of the fluid, (Tf) is the fluid temperature, (kf) is the thermal conductivity, and (Q{fp}) represents the heat transfer between fluid and particles within a computational cell of volume (V_c) [27].

For modeling moisture transport during biomass drying, the gas-phase moisture mass fraction is calculated according to:

[ \frac{\partial \varepsilonf \rhof Y}{\partial t} + \nabla \cdot (\varepsilonf \rhof \mathbf{u} Y) = \nabla \cdot (\varepsilonf \rhof D{eff} \nabla Y) + Sm ]

where (Y) is the moisture mass fraction, (D{eff}) is the effective diffusivity, and (Sm) represents the source term for gas-particle mass transfer [28].

Governing Equations for Particle Phase

The particle phase is modeled using the Discrete Element Method, where each particle's motion follows Newton's second law:

[ mp \frac{d\mathbf{v}}{dt} = mp \mathbf{g} + \sum \mathbf{F}c + \mathbf{F}d + \mathbf{F}_{b} ]

[ \mathbf{I} \cdot \frac{d\boldsymbol{\omega}}{dt} = \sum \mathbf{T}_c ]

where (mp) is particle mass, (\mathbf{v}) is particle velocity, (\mathbf{F}c) represents contact forces, (\mathbf{F}d) is the drag force, (\mathbf{F}{b}) is the buoyancy force, (\mathbf{I}) is the moment of inertia tensor, (\boldsymbol{\omega}) is the angular velocity, and (\mathbf{T}_c) represents torques arising from contact forces [27].

The heat balance for an individual particle is given by:

[ mp c{p,p} \frac{dTp}{dt} = \sum Q{pp} + \sum Q{pw} + Q{fp} ]

where (c{p,p}) is the specific heat capacity of the particle, (Tp) is the particle temperature, (Q{pp}) represents conductive heat transfer between particles, (Q{pw}) is conductive heat transfer between particle and wall, and (Q_{fp}) is convective heat transfer between fluid and particle [27].

For biomass drying applications, the particle mass (m_i) depends on the liquid mass, and the liquid evaporation rate is calculated as:

[ \frac{dm{l,i}}{dt} = -k{p,i} A{p,i} (w^* - Y\infty) ]

where (m{l,i}) is the liquid mass of particle (i), (k{p,i}) is the mass transfer coefficient, (A{p,i}) is the particle surface area, (w^*) is the partial vapor content at the particle surface, and (Y\infty) is the bulk gas phase moisture mass fraction [28].

Table 1: Key Variables in DEM-CFD Governing Equations

| Variable | Symbol | Description | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid volume fraction | (\varepsilon_f) | Fraction of volume occupied by fluid | - |

| Fluid density | (\rho_f) | Mass per unit volume of fluid | kg/m³ |

| Fluid velocity | (\mathbf{u}) | Velocity vector of fluid phase | m/s |

| Particle velocity | (\mathbf{v}) | Velocity vector of particle | m/s |

| Particle temperature | (T_p) | Temperature of individual particle | K |

| Fluid temperature | (T_f) | Temperature of fluid phase | K |

| Moisture mass fraction | (Y) | Mass fraction of moisture in gas | - |

| Drag force | (\mathbf{F}_d) | Force exerted by fluid on particle | N |

| Contact force | (\mathbf{F}_c) | Force from particle-particle contacts | N |

Application to Biomass Drying in Fluidized Beds

Biomass Particle Modeling Approaches

The geometric representation of biomass particles significantly influences the accuracy of DEM-CFD simulations. While spherical particles are computationally efficient, real biomass often consists of cylindrical particles (CBPs) with complex geometric structures that affect fluid mechanics and heat transfer characteristics [27]. Two primary approaches exist for modeling non-spherical biomass particles:

Multi-Sphere Model (MSM): This method aggregates multiple spherical particles into a single entity using specific algorithms. Although MSM can theoretically construct particles with any shape, it faces challenges in balancing computational efficiency and accuracy. With a limited number of sub-spheres, accuracy in representing CBP geometry is compromised, while using an adequate number significantly increases computational load [27].

Super-Ellipsoid Model: This approach provides an ideal alternative for describing CBP morphology, offering improved balance between computational accuracy and efficiency. The governing equation for the super-ellipsoid surface is:

[ f(x,y,z) = \left[ \left( \frac{x}{a} \right)^{s2} + \left( \frac{y}{b} \right)^{s2} \right]^{\frac{s1}{s2}} + \left( \frac{z}{c} \right)^{s_1} - 1 = 0 ]

where (a), (b), and (c) are the semi-principal axes, and (s1), (s2) are shape parameters [27].

Coarse-Graining for Computational Efficiency

A significant limitation of conventional DEM-CFD is the computational cost, which restricts system size. Coarse-grained CFD-DEM addresses this limitation through scaling laws that reduce computational costs while maintaining accuracy, enabling simulation of larger fluidized beds relevant to industrial biomass drying applications [28].

In coarse-graining simulations, one computational particle represents (l^3) original particles, where (l) is the coarse-graining ratio. Consequently, the particle diameter is multiplied by (l) ((d{p,c} = l dp)), and the number of particles is reduced by a factor (l^{-3}) compared to the original system [28].

For heat and mass transfer in coarse-grained systems, scaling relationships ensure physical fidelity:

- Particle mass scales with (l^3): (m{c,j} = l^3 m{i})

- Liquid mass scales with (l^3): (m{l,c,j} = l^3 m{l,i})

- Mass transfer coefficient scales with (l^2): (k{c,j} = \frac{l^2}{l^3} k{p,i} A{p,i} = \frac{1}{l} k{p,i} A_{p,i})

- Heat transfer coefficient follows analogous scaling: (h{c,j} = \frac{1}{l} h{p,i})

These scaling relationships preserve the Sherwood and Nusselt numbers, which use the Reynolds number based on the original particle diameter, ensuring consistent representation of transfer processes [28].

Table 2: Coarse-Graining Scaling Relationships

| Property | Scaling Law | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Particle diameter | (d{p,c} = l dp) | Linear scaling |

| Number of particles | (N_c = N/l^3) | Reduced count |

| Particle mass | (m{c,j} = l^3 m{i}) | Mass conservation |

| Liquid mass | (m{l,c,j} = l^3 m{l,i}) | Mass conservation |

| Mass transfer coefficient | (k{c,j} = \frac{1}{l} k{p,i}) | Area-to-volume ratio |

| Heat transfer coefficient | (h{c,j} = \frac{1}{l} h{p,i}) | Area-to-volume ratio |

| Simulation time | Significant reduction | Enables larger systems |

Implementation Protocols

Simulation Setup for Biomass Drying

System Configuration:

- Implement a 3D fluidized bed reactor with dimensions 0.2 × 0.035 × 0.02 m (height × width × depth) [28]

- Utilize superficial gas velocities of 0.30, 0.35, and 0.40 m/s for comprehensive analysis

- Initialize with wet particles having uniform temperature of 328.15 K and density of 1650.8 kg/m³

- Position particles in a lattice structure before simulation commencement

- Apply uniform superficial velocity boundary condition at the bottom using moisture-free nitrogen gas

Computational Parameters:

- Set CFD time step to 2.5 × 10⁻⁵ s for numerical stability

- Set DEM time step to 2.5 × 10⁻⁶ s for accurate contact resolution

- Configure computational grid with 28 (width) × 16 (depth) × 160 (height) cells

- Simulate for 180 s real-time to capture drying dynamics [28]

Interphase Force and Heat Transfer Models

Drag Force Model: For cylindrical biomass particles, the drag force is closely related to fluid flow direction:

[ \mathbf{F}d = \frac{1}{2} \rhof \varepsilonf^{1-\gamma} Cd A_\perp |\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{v}| (\mathbf{u} - \mathbf{v}) ]

where the correction factor (\gamma) is given by:

[ \gamma = 3.7 - 0.65 \exp\left[ -\frac{(1.5 - \log Re_p)^2}{2} \right] ]

The drag coefficient (C_d) for non-spherical particles incorporates sphericity (\phi):

[ Cd = \frac{8}{Rep} \frac{1}{\phi\perp} + \frac{16}{Rep} \frac{1}{\phi} + \frac{3}{\sqrt{Rep}} \frac{1}{\phi^{3/4}} + 0.42 \times 10^{0.4(-\log \phi)^{0.2}} \frac{1}{\phi\perp} ]

where (Re_p) is the particle Reynolds number [27].

Heat Transfer Correlations: The convective heat transfer coefficient is obtained through the Nusselt number correlation:

[ Nup = \frac{h{p,i} dp}{kf} = (7 - 10\varepsilonf + 5\varepsilonf^2)(1 + 0.7Rep^{0.2} Pr^{1/3}) + (1.33 - 2.4\varepsilonf + 1.2\varepsilonf^2) Rep^{0.7} Pr^{1/3} ]

where (Pr) is the Prandtl number [28].

The mass transfer coefficient follows an analogous correlation through the Sherwood number:

[ Shp = \frac{k{p,i} dp}{D} = (7 - 10\varepsilonf + 5\varepsilonf^2)(1 + 0.7Rep^{0.2} Sc^{1/3}) + (1.33 - 2.4\varepsilonf + 1.2\varepsilonf^2) Re_p^{0.7} Sc^{1/3} ]

where (Sc) is the Schmidt number [28].

Diagram 1: DEM-CFD Biomass Drying Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for DEM-CFD Biomass Drying Research

| Tool/Software | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| OpenFOAM | Open-source CFD platform | Implementation of distribution kernel method (DKM) for numerical stability | Finite volume method, multiphase flow solvers, customization capability [29] |

| MercuryDPM | Discrete Particle Method software | Particle dynamics simulation coupled with CFD | Advanced contact models, complex boundary handling, parallel computing [28] |

| FoxBerry | CFD code specialized for DEM coupling | Fluidized bed drying simulations | Efficient Eulerian-Lagrangian coupling, heat and mass transfer models [28] |

| Coarse-Graining Algorithm | Computational scaling method | Enlarging simulation system size | Reduces particle count while preserving physics, scaling laws for transfer processes [28] |

| Super-Ellipsoid Model | Non-spherical particle representation | Cylindrical biomass particle modeling | Balance between computational accuracy and efficiency for CBPs [27] |

| Distribution Kernel Method (DKM) | Numerical stability enhancement | Remedying coarse-grain particle stiffness | Spreads solid volume and source terms to prevent cell over-loading [29] |

Diagram 2: Heat Transfer Mechanisms in Biomass Fluidized Beds

Validation and Experimental Correlation

Model Verification Approaches

Successful implementation of DEM-CFD for biomass drying requires rigorous validation against experimental data. Recent research has demonstrated several effective verification approaches:

Infrared Thermography Measurements: Comparison of numerical results with experimental infrared thermography measurements provides accurate verification of temperature evolution in cylindrical biomass particles. This approach validates the heat transfer model, including particle-particle, particle-wall, and fluid-particle interactions [27].

Laboratory-Scale Reactor Data: Validation using data from different lab-scale reactors confirms the model's ability to capture transient heat transfer processes under varying fluidization velocities and sand loads [29]. This includes assessing the model's performance in predicting bed temperature distribution and fluctuation processes.

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis: Comprehensive investigation of effects from gas velocity, inlet temperature, and particle thermal conductivity on heat transfer behaviors provides critical validation of model robustness [27]. Studies show that gas velocity improves bed temperature distribution uniformity, while thermal conductivity of particles has no obvious influence on bed temperature or convective heat transfer rate.

Performance Metrics

Key performance indicators for DEM-CFD biomass drying simulations include:

- Sherwood Number Accuracy: Coarse-graining simulations must accurately capture the Sherwood number, which governs mass transfer rates during drying [28]

- Particle Temperature Profile: Model predictions should match experimental measurements of particle temperature evolution over time [27]

- Moisture Content: Simulation results for moisture removal rates should correlate with experimental drying curves

- Fluidization Behavior: Predicted particle motion and mixing characteristics should match observed fluidization dynamics

Table 4: Validation Parameters for Biomass Drying Simulations

| Parameter | Validation Method | Acceptance Criterion | Reference Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle temperature | Infrared thermography | ±5% deviation | Experimental measurement [27] |

| Sherwood number | Mass transfer analysis | ±10% deviation | Correlation prediction [28] |

| Bed temperature distribution | Thermocouple arrays | Qualitative match | Experimental observation [27] |

| Drying rate | Moisture measurement | ±15% deviation | Gravimetric analysis [28] |

| Particle orientation | High-speed imaging | Statistical agreement | 60-90° range proportion [27] |

Solar-Biomass Hybrid Dryer Simulation and Design Optimization