Biomass vs. Fossil Fuels: A Comparative Life-Cycle Analysis of Environmental Impact

This article provides a systematic, evidence-based comparison of the environmental impacts of biomass and fossil fuels, tailored for researchers and scientific professionals.

Biomass vs. Fossil Fuels: A Comparative Life-Cycle Analysis of Environmental Impact

Abstract

This article provides a systematic, evidence-based comparison of the environmental impacts of biomass and fossil fuels, tailored for researchers and scientific professionals. It examines the foundational science of carbon cycles, methodologies for assessing emissions, solutions to key environmental trade-offs, and a validated comparative analysis. The synthesis offers critical insights for informing sustainable energy decisions in research and industrial applications, framing the discussion within the urgent context of climate change mitigation.

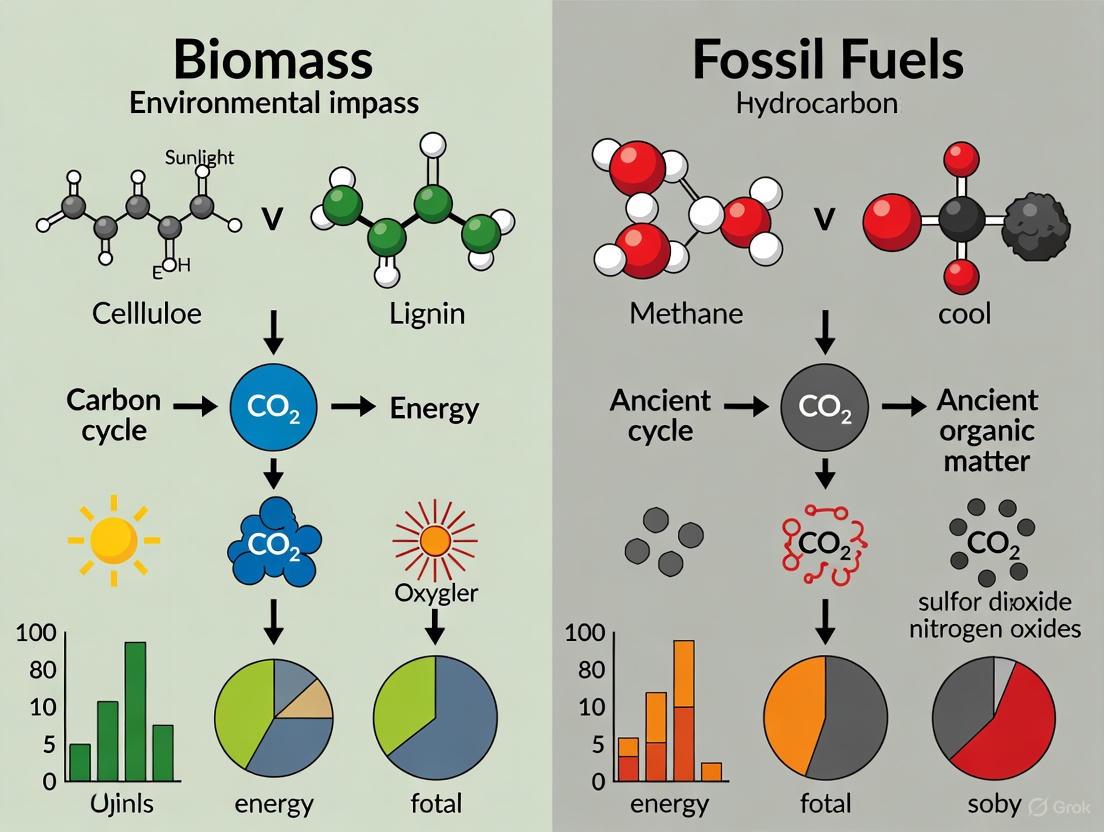

The Fundamental Science: Contrasting Carbon Cycles of Biomass and Fossil Fuels

The global energy landscape and strategies for mitigating climate change are fundamentally shaped by the sources of our fuels. This guide provides a comparative analysis of two distinct energy sources: renewable organic matter (biomass) and ancient geological deposits (fossil fuels). Understanding their origins, properties, and environmental impacts is crucial for researchers, scientists, and policymakers engaged in energy transition planning.

Biomass consists of organic material from living or recently living organisms, such as plants, agricultural residues, and organic waste [1]. It is part of a rapid carbon cycle, where carbon is continuously absorbed and released. In contrast, fossil fuels—including coal, crude oil, and natural gas—are derived from the decomposed remains of ancient plants and animals that have been subjected to heat and pressure deep within the Earth's crust over millions of years [2] [3]. These fuels represent a carbon sequestered in a long-term geological cycle, now being released rapidly through human extraction and combustion.

The formation pathways for these two resource types operate on vastly different timescales and involve distinct geological and biological processes.

Renewable Organic Matter (Biomass)

Biomass is a renewable energy source derived from organic materials. Its key characteristic is its participation in a short-term carbon cycle.

- Sources: Primary sources include wood, agricultural waste (e.g., crop residues), energy crops (plants grown specifically for energy), municipal solid waste, and algae [1] [4].

- Formation Process: Biomass is formed through photosynthesis in a cycle that takes place over months to years. Plants absorb CO₂ from the atmosphere, using solar energy to convert it into organic compounds. When this biomass is used for energy, the carbon is released back into the atmosphere, completing the cycle [1].

Ancient Geological Deposits (Fossil Fuels)

Fossil fuels are non-renewable resources that formed from ancient organic matter over geological timescales.

- Sources: The primary types are coal, petroleum (crude oil), and natural gas [2] [3].

- Formation Process: This process occurs over millions of years [2]:

- Coal: Originated from ancient plant matter in swamps, which was buried under layers of sediment and transformed by heat and pressure [3].

- Petroleum and Natural Gas: Formed from the remains of marine microorganisms (plankton) that settled on the ocean floor. Over time, they were buried under sedimentary layers, and the resulting heat and pressure converted the organic matter into hydrocarbons [2] [3]. These fuels are often found trapped in underground reservoirs by non-porous rock layers [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Energy Sources

| Characteristic | Renewable Organic Matter (Biomass) | Ancient Geological Deposits (Fossil Fuels) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Sources | Wood, agricultural waste, energy crops, algae [1] | Coal, crude oil, natural gas [2] |

| Formation Process | Photosynthesis (biological) | Geochemical transformation under heat and pressure |

| Formation Timescale | Months to years (short-term cycle) | Millions of years (long-term cycle) [2] |

| Inherent Renewability | Renewable; can be replenished within a human lifetime [1] | Non-renewable; finite within human time frames [2] [5] |

| Key Chemical Elements | Carbon, hydrogen, oxygen | Carbon, hydrogen [2] |

Comparative Environmental Impact Analysis

A critical component of the biomass vs. fossil fuels debate is a quantitative assessment of their environmental footprints, particularly regarding carbon emissions and land use.

Carbon Emissions and Climate Impact

The core difference in climate impact lies in the origin of the carbon emissions.

- Fossil Fuels: Burning fossil fuels releases "new" carbon that has been sequestered from the atmosphere for millions of years. This process directly increases the concentration of CO₂ in the atmosphere, contributing significantly to the greenhouse effect and global warming [2] [6]. The power sector, largely reliant on fossil fuels, was the largest source of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2023 [6].

- Biomass: When managed sustainably, biomass is often considered carbon-neutral over its lifecycle. The CO₂ released during combustion is approximately equal to the CO₂ absorbed by the plants during their growth [1]. However, this neutrality depends on sustainable harvesting and regrowth rates. Furthermore, some studies question this balance when accounting for supply chain emissions and the immediate carbon debt created by harvesting [7].

Land Use and Ecosystem Impacts

The extraction and cultivation of both energy sources have significant land-use implications.

- Fossil Fuel Extraction: Mining and drilling operations directly disturb land. A 2025 study on nickel mining (a critical metal for low-carbon energy technologies) revealed that land transformation factors for mining are often 4 to 500 times greater than previously reported, leading to substantial biomass carbon losses that are rarely accounted for [8]. This highlights that the environmental impact of extracting resources for energy systems extends beyond direct fuel use.

- Biomass Cultivation: Growing dedicated energy crops requires large areas of arable land. This can lead to direct and indirect land-use change, including deforestation, loss of biodiversity, and competition with food production [1] [7]. Converting natural landscapes for biofuel farms releases stored soil and plant carbon, potentially negating the climate benefits for decades [7].

Air Pollution and Public Health

Both fuel types produce air pollutants upon combustion, with serious health consequences.

- Fossil Fuels: The burning of coal, oil, and gas is a major source of fine particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO₂), and sulfur oxides. According to the World Health Organization, 99% of the global population breathes air exceeding air quality limits, largely due to fossil fuel combustion, resulting in an estimated 7 million premature deaths annually [6].

- Biomass: Burning biomass also produces air pollutants, including tiny toxic particles, ozone, and nitrogen dioxide, which can cause respiratory irritation, asthma attacks, and other serious health issues [7]. The location of biomass processing facilities can exacerbate existing air pollution burdens on low-income communities and communities of color [7].

Table 2: Quantitative Comparison of Environmental Impacts

| Impact Parameter | Renewable Organic Matter (Biomass) | Ancient Geological Deposits (Fossil Fuels) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Climate Mechanism | Releases biogenic CO₂ (part of active cycle) | Releases fossil CO₂ (new to atmosphere) |

| Representative Land Use (per tonne of resource) | Varies by crop; can drive deforestation | Nickel mining: 4 - 398 m²/t (sulfide median: 30 m²/t) [8] |

| Key Air Pollutants | Particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide [7] | Particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide, sulfur oxides [6] |

| Public Health Burden | Respiratory illness, asthma attacks [7] | ~7 million premature deaths/year linked to air pollution [6] |

| Water & Soil Impact | Potential for soil erosion and water pollution from agrochemicals [7] | Water contamination risks from extraction (e.g., fracking), oil spills |

Experimental Protocols for Impact Assessment

To generate the data required for a comparative guide, researchers employ standardized analytical protocols. Two key methodologies are detailed below.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Protocol

Objective: To quantify the cumulative environmental impacts of a fuel or product from raw material extraction ("cradle") to end-of-life ("grave").

Methodology:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Define the purpose, functional unit (e.g., 1 MJ of energy), and system boundaries.

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): Compile an inventory of all energy and material inputs (e.g., water, fertilizer, diesel) and environmental releases (e.g., CO₂, CH₄, NOₓ, wastewater) for each process stage.

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Translate inventory data into impact category results, such as Global Warming Potential (GWP), acidification, eutrophication, and land use.

- Interpretation: Analyze results to draw conclusions, identify significant issues, and provide recommendations.

Key Considerations for Fuels:

- For fossil fuels, the LCA must include exploration, extraction, transport, refining, combustion, and any upstream emissions from infrastructure.

- For biomass, the LCA must include crop cultivation (including fertilizer and pesticide production), harvest, transport, conversion to biofuel, combustion, and crucially, land-use change emissions.

Biomass Carbon Stock Assessment Protocol

Objective: To quantify the carbon dioxide emissions resulting from vegetation clearance for resource extraction, such as mining or land conversion for energy crops. This protocol is based on methodologies used in recent studies of mining impacts [8].

Methodology:

- Site Delineation: Map the land footprint of the operation (e.g., mine site, new agricultural land) using satellite imagery or site plans.

- Land Transformation Factor Calculation: Calculate the land area disturbed per unit of resource produced (e.g., m² per tonne of nickel or per GJ of biofuel).

- Biomass Carbon Density Estimation:

- Use a globally harmonized biomass dataset (e.g., Spawn et al., 2020) to estimate aboveground and belowground biomass carbon density [8].

- Determine the baseline carbon stock by averaging biomass densities in undisturbed vegetation surrounding the site.

- Carbon Emission Calculation: Multiply the land transformation factor by the baseline biomass carbon density to estimate total CO₂ emissions from vegetation loss.

This methodology revealed that biomass carbon emissions from nickel mining are significant and often excluded from corporate sustainability reports, leading to a substantial underestimation of their environmental impact [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Research into fuel properties and environmental impacts relies on a suite of analytical tools and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Elemental Analyzer | Determines the carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur content of solid and liquid fuel samples, critical for calculating energy content and emission factors. |

| Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (GC-MS) | Separates, identifies, and quantifies complex mixtures of volatile compounds, such as those in crude oil, biofuels, or engine emissions. |

| Isotope-Labeled Tracers (e.g., ¹³CO₂) | Tracks the fate of specific carbon atoms through biological and chemical systems (e.g., in soil or combustion plumes) to study biogeochemical cycles. |

| Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Database | Provides standardized, peer-reviewed data on the energy and material inputs for common processes (e.g., Ecoinvent), ensuring consistency in LCA studies. |

| Global Biomass Carbon Datasets | Provides spatially explicit estimates of vegetation carbon stocks, used for assessing land-use change emissions from agriculture and mining [8]. |

The comparative analysis reveals a fundamental trade-off. Fossil fuels offer high energy density but are inextricably linked to long-term geological carbon release, severe air pollution, and significant, often underreported, ecosystem impacts from extraction [2] [8] [6]. Biomass, as a renewable resource, participates in an active carbon cycle and can reduce dependence on fossil fuels [1]. However, its sustainability is conditional on responsible cultivation that avoids detrimental land-use change, air pollution from combustion, and competition with food security [7].

For researchers and policymakers, the choice is not simplistic. The transition to a sustainable energy system requires a nuanced understanding of these trade-offs. Prioritizing the reduction of fossil fuel consumption remains paramount [6]. The role of biomass should be strategically limited to hard-to-electrify sectors and must be governed by robust sustainability criteria that safeguard ecosystems, the climate, and public health.

The concept of a closed-loop carbon cycle is central to understanding the potential climate benefits of biomass energy. In theory, the biogenic carbon cycle represents a balanced, circular system where carbon dioxide (CO₂) absorbed from the atmosphere by plants during growth is eventually released back through processes like decomposition or combustion, resulting in net-zero new atmospheric carbon over the cycle period [9]. This stands in stark contrast to the one-way flow of carbon from fossil fuels, where carbon stored for millions of years in geological reserves is permanently added to the active atmosphere [10].

This guide objectively compares the environmental performance of biomass and fossil fuels, focusing on the theory and practice of carbon cycling. The core thesis is that while the biogenic carbon cycle functions as a closed-loop system under ideal conditions of sustainable management, its real-world climate impact is determined by complex factors including temporal scale, land-use practices, and system boundary definitions in lifecycle assessment [11]. For researchers and scientists, accurately quantifying these factors is critical for validating the role of biomass in a low-carbon future.

Quantitative Comparison: Biomass vs. Fossil Fuels

Empirical data and lifecycle assessments provide a quantitative basis for comparing the climate impacts of biomass and fossil fuels. The following tables summarize key comparative data on emissions and carbon stocks.

Table 1: Comparative Lifecycle CO₂ Emissions and Reductions

| Fuel Type | Estimated CO₂ Emissions per Liter (kg) | Renewability | Estimated Emission Reduction vs. Fossil Fuels | Key Sources / Feedstocks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biofuels | 0.8 – 1.3 [12] | Renewable [12] | 50–70% [12] | Crops (e.g., corn, sugarcane, soybean), agricultural residues, forestry by-products [12] |

| Fossil Fuels | 2.5 – 3.2 [12] | Non-renewable [12] | Baseline | Crude oil, coal, natural gas [12] |

Table 2: Global Carbon Pools and Fluxes (Select Data)

| Pool or Flux | Quantity | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Average Global Above-Ground Biomass Carbon Stock | 378 PgC (1993-2020) [13] | Estimated from satellite radar data; shows slight gross increase of 1.18 PgC over the period [13]. |

| Atmospheric CO₂ Concentration (2025) | 425.7 ppm [14] | 52% above pre-industrial levels [14]. |

| Global Fossil CO₂ Emissions (2025) | 38.1 billion tonnes [14] | Projected record high; 1.1% rise from 2024 [15]. |

| Land & Ocean Sink Proportion | ~55% of total CO₂ emissions [16] | Historically, land (~25%) and ocean (~30%) sinks absorbed over half of human emissions [16]. |

Core Concepts and Methodologies

Conceptual Framework: The Green Carbon Cycle

In academic research, the subsystem of the global carbon cycle most relevant to biomass is often termed the "Green Carbon Cycle" (GCC) [11]. This framework encompasses the exchange of carbon between the atmosphere, the terrestrial biosphere (plants and soil), and the ocean over relatively short time scales (days to centuries) through the fundamental processes of photosynthesis, respiration, decomposition, and combustion [9].

The core of the theoretical closed loop is a mass balance: carbon released at end-of-life (e.g., from combustion) is assumed to be re-sequestered by new plant growth, creating a net-neutral flow over the harvest rotation period. The critical academic distinction lies between this fast, biological cycle and the slow, geological cycle of fossil fuels. Burning fossil carbon represents a net addition to the atmospheric pool, while burning biomass, in theory, only recycles carbon already part of the active, terrestrial-atmospheric system [10] [9].

Key Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Methodologies

Life Cycle Assessment is the standard tool for quantifying and comparing the environmental impacts of products and fuels. Several methodological approaches have been developed to model biogenic carbon flows, each with distinct strengths and weaknesses [11].

- The

-1/+1Method: This common method, endorsed by standards like PAS 2050 and ISO 14067, tracks biogenic carbon flows across the product lifecycle. A-1is assigned when carbon is removed from the atmosphere (sequestration during growth), and a+1is assigned when it is released back (combustion/decomposition). If the system is balanced, the sum is zero, indicating carbon neutrality [11]. - Dynamic LCA: This approach incorporates the timing of carbon emissions and removals, providing a more realistic climate impact profile over time. It is particularly useful for evaluating "carbon debt" – the temporary increase in atmospheric CO₂ that occurs when biomass is harvested and burned before regrowth has occurred [11].

- GWPbio: This metric aims to better represent the actual global warming potential (GWP) of biogenic CO₂ fluxes by accounting for the dynamic response of the global carbon cycle to a pulse emission of biogenic CO₂, often using a different characterization factor than fossil CO₂ [11].

Table 3: Comparison of Key LCA Methods for Biogenic Carbon

| Method | Core Principle | Handling of Time | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

-1/+1 Method |

Mass balance of carbon flows | Static; timing of flows is ignored | Compliance with carbon accounting standards; simplified assessments [11]. |

| Dynamic LCA | Models the atmospheric decay of CO₂ and regrowth of biomass | Explicitly accounts for the temporal profile of emissions and removals | Research to understand short-to-medium-term climate impacts and carbon debt [11]. |

| GWPbio | Applies a specific characterization factor for biogenic CO₂ | Incorporates time by modeling the perturbation to the global carbon cycle over a chosen timeframe (e.g., 100 years) | Research comparing the integrated radiative forcing of different bioenergy systems [11]. |

Experimental Protocols for Biomass Carbon Analysis

Research into biomass carbon stocks and fluxes relies on rigorous experimental and observational protocols.

Protocol 1: Satellite-Based Above-Ground Biomass Carbon Mapping

- Objective: To generate long-term, global datasets of Above-Ground Biomass Carbon (AGC) to understand carbon dynamics under climate change and land-use shifts [13].

- Methodology: AGC is estimated using satellite radar backscatter data (e.g., from 1993-2020). This data is integrated with ancillary information such as vegetation metrics (tree cover, tree density) and climate data to enhance mapping accuracy. The radar signal interacts with vegetation volume and structure, which can be correlated to AGC through models. The resulting global datasets are produced at resolutions such as 8 km and validated against ground measurements [13].

- Output: A spatially and temporally continuous AGC dataset quantifying stocks and changes, enabling identification of carbon gains (e.g., in boreal forests) and losses (e.g., in tropical forests) [13].

Protocol 2: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of Biofuel Pathways

- Objective: To quantify the lifecycle greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of a biofuel, from feedstock production to end-use (well-to-wheels), and compare it to a fossil fuel baseline [12].

- Methodology:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Define the functional unit (e.g., 1 MJ of energy) and system boundaries.

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): Collect data on all material and energy inputs/outputs for each stage:

- Feedstock Cultivation: Inputs of fertilizers, pesticides, fuel for machinery.

- Processing: Energy for fermentation, transesterification, distillation.

- Transportation: Fuel for moving feedstock and final fuel.

- Combustion: Direct emissions from burning the fuel.

- Biogenic Carbon Accounting: Apply a chosen method (e.g.,

-1/+1, dynamic LCA) to model CO₂ flows from biomass growth and combustion. - Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Calculate the total global warming potential, typically in kg CO₂-equivalent per functional unit [12] [11].

- Output: A comprehensive emissions profile supporting claims of emission reductions (e.g., "biofuels can cut agricultural carbon emissions by up to 70%") [12].

Research Tools and Visualization

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Biogenic Carbon Cycle Analysis

| Tool / Resource | Category | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Global Carbon Budget Annual Report [14] | Data Resource | Provides the latest authoritative data on global fossil and land-use CO₂ emissions, sinks, and atmospheric concentrations. Critical for contextualizing research. |

| Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Software (e.g., openLCA, SimaPro) | Analytical Software | Enables modeling of complex product systems, including biogenic carbon flows, to calculate environmental impacts using various methods. |

| Bookkeeping Models (e.g., as used in GCB) [15] | Analytical Model | Tracks carbon stocks and fluxes from land-use and land-use change over time, helping attribute emissions to specific activities. |

| Biogenic Carbon Project Guidance [17] | Methodological Framework | Aims to provide harmonized recommendations for modeling biogenic carbon in LCA, bringing stability and credibility to results. |

| Satellite Radar Backscatter Data [13] | Remote Sensing Data | Used to derive large-scale, long-term estimates of above-ground biomass, crucial for verifying carbon stock changes and model outputs. |

Visualizing the Carbon Cycles

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference between the theoretical closed loop of the biogenic carbon cycle and the linear, additive nature of the fossil fuel carbon cycle.

Carbon Cycle Theory: Closed Loop vs. Linear Flow

Critical Analysis and Research Gaps

The idealized model of a closed loop faces significant challenges in practice. A primary complication is the carbon debt incurred when biomass is harvested. The immediate release of CO₂ from combustion is only re-sequestered over the years or decades required for regrowth, creating a temporal imbalance with near-term climate consequences [9]. The "time to carbon parity" – the period needed for the carbon savings from bioenergy to offset this initial debt – is a critical metric that varies significantly based on feedstock and supply chain [11].

Furthermore, the assumption of carbon neutrality often ignores system-level effects. These include:

- Indirect Land-Use Change (ILUC): Clearing land for biomass production can displace existing activities, potentially causing deforestation and releasing large soil carbon stocks elsewhere [11].

- Albedo Effects: Changes in surface reflectivity from land-cover change (e.g., replacing a dark forest with a lighter-colored crop) can introduce non-carbon warming or cooling effects, complicating the simple carbon balance [11].

- Non-Biogenic Emissions: The lifecycle of biofuels includes fossil carbon emissions from equipment used in farming, transportation, and processing, which can erode the net climate benefit [12] [9].

Ongoing research efforts, such as the Biogenic Carbon Project by the Life Cycle Initiative, aim to harmonize assessment methods and address these complexities to provide more stable and credible guidance for policymakers and researchers [17]. As of 2025, this project is developing a consensus on best practices for modeling biogenic carbon in LCA [17].

The fossil carbon cycle describes the anthropogenic process of transferring carbon that was sequestered over geological timescales—millions of years—into the atmosphere over an extremely short period—decades. This represents a fundamental alteration of the natural carbon cycle, where carbon slowly moved between atmosphere, oceans, biosphere, and geological reservoirs. In the contemporary cycle, human activities, primarily fossil fuel combustion and cement production, create a dominant, unidirectional flow of carbon from geological storage to the atmospheric pool [18]. This transfer is the primary driver of the rapid increase in atmospheric CO₂ concentration, which is projected to reach 425.7 parts per million (ppm) in 2025, 52% above pre-industrial levels [14] [19].

Understanding the mechanisms, rates, and impacts of this transfer is crucial for climate change mitigation. This guide objectively compares the central "performance" of this process—its quantitative contribution to atmospheric change—against the backdrop of natural carbon cycles and alternative systems like biomass energy, providing researchers with structured data and methodologies for environmental impact assessment.

Quantitative Analysis of Fossil Carbon Transfer

The transfer of sequestered carbon is quantified through annual emissions inventories. The following tables summarize the latest global and regional data on these fluxes.

Table 1: Global Carbon Budget (2025 Projections) [14] [15] [19]

| Budget Component | 2025 Projected Value | Annual Change | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fossil CO₂ Emissions | 38.1 billion tonnes CO₂ | +1.1% | Growth in coal (+0.8%), oil (+1%), and natural gas (+1.3%) use. |

| Land-Use Change Emissions | 4.1 billion tonnes CO₂ | -9.8% | Reduced deforestation in South America; sensitive to fires. |

| Atmospheric CO₂ Concentration | 425.7 ppm | +2.3 ppm | Result of total emissions minus sink uptake; 52% above pre-industrial. |

| Remaining 1.5°C Carbon Budget | 170 billion tonnes CO₂ | ~4 years at current emissions | Virtually exhausted; necessitates immediate, rapid emission reductions. |

Table 2: National and Regional Contributions to Fossil CO₂ Emissions (2025 Projections) [14] [15] [20]

| Country/Region | Projected Emission Change | Share of Global Emissions | Primary Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | +0.4% | 32% | Moderate energy demand growth offset by extraordinary renewable energy expansion. |

| United States | +1.9% | 13% | Colder weather conditions and higher energy consumption. |

| European Union | +0.4% | ~8% | Reversal of previous declining trends due to weather and consumption factors. |

| India | +1.4% | ~8% | Slower growth due to strong renewables growth and an early monsoon reducing cooling demand. |

| Rest of World | +1.1% | ~39% | Persistent global dependence on all fossil fuel types. |

Table 3: Sector-Specific Contributions to the Fossil Carbon Transfer [14] [19]

| Sector | Contribution | Trend & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| International Aviation | 6.8% increase in emissions | Now exceeds pre-COVID pandemic levels. |

| International Shipping | Emissions remain flat | - |

| Cement Production | Included in fossil CO₂ totals | The cement carbonation sink is accounted for in the overall budget. |

Methodologies for Quantifying Carbon Flows

Accurately tracking the fossil carbon cycle requires robust, multi-faceted experimental and observational protocols. The scientific community relies on several key methodologies, synthesized by the Global Carbon Project and other institutions.

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

1. Protocol for Estimating Fossil CO₂ Emissions (EFOS)

- Primary Data Sources: National energy statistics from entities like the International Energy Agency (IEA), data on cement production, and data on gas flaring [21].

- Methodology: A mass-energy balance approach. Fuel production data (e.g., tons of coal, barrels of oil) are combined with fuel-specific carbon content and oxidation factors to calculate the total carbon dioxide released upon combustion. Cement production emissions are calculated based on the stoichiometry of the calcination process [21].

- Uncertainty Handling: Uncertainties are quantified using country- and fuel-specific emission factor uncertainties and energy data uncertainties, typically reported as ±1σ [21].

2. Protocol for Measuring Atmospheric CO₂ Growth Rate (GATM)

- Primary Data Sources: Direct, high-precision measurements of atmospheric CO₂ concentration from a global network of surface stations (e.g., Mauna Loa Observatory, NOAA's Global Monitoring Laboratory) [21].

- Methodology: The global growth rate is computed from the annual change in the globally averaged CO₂ concentration. The global average is calculated by carefully weighting the measurements from different stations to represent the entire atmosphere [21].

- Uncertainty Handling: Uncertainty is small relative to other budget terms, estimated at ±0.2 GtC yr⁻¹ (±0.1 ppm yr⁻¹) [21].

3. Protocol for Estimating Ocean Carbon Sink (SOCEAN)

- Primary Data Sources: Surface ocean CO₂ partial pressure (pCO₂) measurements from the Surface Ocean CO₂ Atlas (SOCAT) and ocean biogeochemistry models [21].

- Methodology:

- Observation-based: Uses over 40 million surface ocean pCO₂ measurements to compute global air-sea CO₂ fluxes.

- Model-based: Global ocean biogeochemistry models (GOBMs) are forced by atmospheric reanalysis data to simulate the ocean's physical and biological processes that govern CO₂ uptake.

- Uncertainty Handling: The uncertainty range is determined from the spread across multiple models and methods [21].

4. Protocol for Estimating Land Carbon Sink (SLAND)

- Primary Data Sources: Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs), atmospheric inversions, and forest inventory data [14] [21].

- Methodology:

- DGVM Approach: Process-based models simulate vegetation and soil carbon dynamics in response to environmental drivers like atmospheric CO₂, climate, and land-use change.

- Atmospheric Inversion: Uses atmospheric transport models and CO₂ concentration measurements to infer the location and magnitude of surface CO₂ fluxes.

- Uncertainty Handling: The land sink has the largest uncertainty among budget components (±1.1 GtC yr⁻¹), derived from the spread across multiple DGVMs and comparison with inversions [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials and Data Sources for Carbon Cycle Research

| Item/Resource | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Global Carbon Project (GCP) Data | The primary synthesized dataset for the global carbon budget, providing harmonized emissions and sink data [14] [21]. |

| Energy Statistics (IEA, EIA) | Foundational data on fossil fuel production, consumption, and trade, used as input for emission calculations. |

| Surface Ocean CO₂ Atlas (SOCAT) | A publicly available, quality-controlled database of surface ocean pCO₂ measurements, essential for quantifying the ocean sink [21]. |

| Atmospheric CO₂ Observatories | A global network (e.g., Mauna Loa, Barrow, South Pole) providing the fundamental time-series data for atmospheric CO₂ growth [21]. |

| Dynamic Global Vegetation Models (DGVMs) | Process-based computational models (e.g., ORCHIDEE, JULES) used to simulate the terrestrial carbon cycle and estimate the land sink [22] [21]. |

| Earth System Models (ESMs) | Complex coupled models (e.g., IPSL-CM6A-LR) that simulate the full climate system and carbon cycle, used for projecting future changes and understanding feedbacks [22]. |

| Satellite Data (e.g., for Land-Use Change) | Provides spatial data on deforestation, fire activity, and vegetation health to constrain land-use emission estimates. |

Comparative Pathways: Fossil vs. Biogenic Carbon Transfer

The critical distinction in environmental impact lies in the timescale and net effect of transferring carbon to the atmosphere. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference between the fossil carbon cycle and a sustainable biogenic carbon cycle.

Climate Feedback Mechanisms Intensified by Fossil Transfer

The massive and rapid CO₂ release from the fossil carbon cycle triggers feedback mechanisms that further amplify climate change. A key finding from recent research is that climate change itself is weakening the planet's natural carbon sinks. Approximately 8% of the rise in atmospheric CO₂ concentration since 1960 is attributed to this weakening, creating a dangerous positive feedback loop [14] [20]. Furthermore, non-CO₂ greenhouse gases like methane (CH₄) and nitrous oxide (N₂O), also released from fossil fuel systems, contribute to a carbon-climate feedback that further reduces the efficiency of land and ocean sinks [22].

The diagram below maps these critical feedback processes initiated by the fossil carbon transfer.

The fossil carbon cycle represents a high-impact, one-way transfer of sequestered carbon that is overwhelming the planet's natural regulatory systems. The quantitative data presented confirms this transfer is accelerating, with record-high emissions projected for 2025 driving atmospheric CO₂ to levels 52% above pre-industrial concentrations [14] [20]. The resultant climate change is now actively weakening the land and ocean sinks, creating a positive feedback that compounds the problem [14] [22]. The remaining carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5°C is virtually exhausted, equivalent to just four years of current emissions [14] [15]. This analysis underscores that disrupting the slow geological carbon cycle through fossil fuel combustion is the dominant factor in anthropogenic climate change, and halting this transfer is the most urgent priority for climate mitigation.

Within climate change research, understanding the distinct profiles of key greenhouse gases (GHGs)—carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and nitrous oxide (N₂O)—is fundamental. For investigators comparing the environmental impact of biomass versus fossil fuels, these profiles provide the critical metrics for objective assessment. Greenhouse gases differ significantly in their atmospheric lifetime, heat-trapping potential, and primary sources, factors that determine their overall contribution to global warming. This guide provides a structured comparison of these three principal gases, presenting standardized data and methodologies essential for rigorous environmental impact research.

The framing is particularly crucial for the bioenergy sector, where the classification of carbon emissions—as either part of the rapid biogenic carbon cycle or the slow geological carbon cycle—defines their net impact on the atmosphere [23]. The data and protocols that follow equip researchers with the tools to conduct precise, comparable analyses of energy systems and their climatic effects.

Gas Profiles and Comparative Analysis

The following profiles detail the characteristics of each greenhouse gas, with quantitative data structured for direct comparison. The accompanying table synthesizes these attributes, providing a clear reference for their relative impacts.

Carbon Dioxide (CO₂)

- Primary Sources: The dominant source of anthropogenic CO₂ is the combustion of fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas) for energy, heat, and transportation [24]. Additional significant sources include industrial processes (e.g., cement production) and land-use changes such as deforestation and soil degradation [24].

- Global Warming Potential (GWP): The baseline value of 1 over a 100-year timescale (GWP₁₀₀) [25].

- Atmospheric Lifetime: Ranges from centuries to thousands of years, making its impact on the climate exceptionally long-lived [25].

- Contribution to Global GHG Emissions: As the most abundant anthropogenic GHG, fossil CO₂ alone accounted for 74.5% of global emissions in 2024 [26].

Methane (CH₄)

- Primary Sources: The main sources are agriculture (enteric fermentation from livestock and rice cultivation), fossil fuel production (fugitive emissions from oil and gas extraction), waste management (landfills), and biomass burning [25].

- Global Warming Potential (GWP): A value of 28-34 over a 100-year timescale (GWP₁₀₀). This means one tonne of methane generates 28-34 times the warming of one tonne of CO₂ over a century [25].

- Atmospheric Lifetime: Approximately 12 years, making it a relatively short-lived climate pollutant [25].

- Contribution to Global GHG Emissions: Accounted for 17.9% of global GHG emissions in 2024 [26].

Nitrous Oxide (N₂O)

- Primary Sources: Overwhelmingly from agriculture, specifically the application of synthetic and organic nitrogen fertilizers to soils, which stimulates microbial processes that produce N₂O [25] [27]. Other sources include industrial activities and fossil fuel combustion.

- Global Warming Potential (GWP): A value of 265-273 over a 100-year timescale (GWP₁₀₀), making it an extremely potent greenhouse gas [25] [27].

- Atmospheric Lifetime: Approximately 121 years [25].

- Contribution to Global GHG Emissions: Accounted for 4.8% of global GHG emissions in 2024 [26]. Despite its relatively small share of total emissions, its high GWP and long lifetime make it a critical target for mitigation. As of 2025, atmospheric concentrations reached a record 338.42 parts per billion [27].

Table 1: Comparative Profiles of Key Greenhouse Gases

| Characteristic | Carbon Dioxide (CO₂) | Methane (CH₄) | Nitrous Oxide (N₂O) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | CO₂ | CH₄ | N₂O |

| Primary Anthropogenic Sources | Fossil fuel combustion, industrial processes, land-use change | Agriculture, fossil fuel extraction, waste, biomass burning | Agricultural soil management, industrial activities |

| 100-Year Global Warming Potential (GWP₁₀₀) | 1 (Baseline) | 28-34 [25] | 265-273 [25] [27] |

| Atmospheric Lifetime | Centuries to millennia | ~12 years [25] | ~121 years [25] |

| Contribution to 2024 Global GHG Emissions | 74.5% (Fossil CO₂) [26] | 17.9% [26] | 4.8% [26] |

Experimental Protocols for Emission Measurement

Accurately quantifying greenhouse gas emissions and their climatic impact requires standardized methodologies. The following protocols are foundational for both inventory reporting and primary research.

Methodology for National GHG Inventories

- Purpose: To provide a consistent, transparent framework for countries to estimate and report their anthropogenic GHG emissions to the UNFCCC [26] [25].

- Protocol:

- Activity Data Collection: Gather nationwide data on the scale of human activities (e.g., tons of coal burned, number of livestock, hectares of fertilized cropland) [26].

- Emission Factor Application: Multiply the activity data by standardized emission factors (e.g., kg of CO₂ emitted per ton of coal burned). These factors are established by the IPCC [25].

- CO₂-Equivalent Calculation: Convert the mass of non-CO₂ gases (CH₄, N₂O) into CO₂-equivalents (CO₂e) using their respective 100-year Global Warming Potential (GWP) values, enabling the summation of total GHG impact [25].

- Data Application: This methodology is used to compile international datasets, such as the European Commission's EDGAR database, which reported 2024 global GHG emissions of 53.2 gigatonnes of CO₂ equivalent [26].

Protocol for Biomass Carbon Cycle Analysis

- Purpose: To determine the net carbon balance of using biomass for energy, a critical comparison in the "biomass vs. fossil fuels" debate [23].

- Protocol:

- System Boundary Definition: Define the spatial and temporal boundaries of the analysis, including the entire supply chain (cultivation, harvest, transport, processing, combustion).

- Biogenic Carbon Tracking: Model the flows of biogenic carbon, accounting for CO₂ uptake during plant growth and its release upon combustion [23].

- Reference Scenario Comparison: Compare the emissions from the bioenergy system against a reference scenario (e.g., continued use of fossil fuels), while also modeling the biogenic carbon flows in the absence of the bioenergy system [23].

- Timeframe Specification: Explicitly state the analysis timeframe, as net carbon benefits from bioenergy may only materialize over decades due to the time required for regrowth to re-absorb emitted carbon [28].

Methodology for Agricultural N₂O Flux Measurement

- Purpose: To directly measure nitrous oxide emissions from soils following fertilizer application, which is vital for refining emission factors and testing mitigation strategies [27].

- Protocol:

- Chamber Deployment: Place non-flow-through, non-steady-state chambers (closed chambers) on the soil surface in experimental plots.

- Gas Sampling: At regular intervals (e.g., pre-application, and daily/weekly post-application), use a syringe to collect air samples from the chamber headspace [27].

- Gas Chromatography Analysis: Analyze the concentration of N₂O in the gas samples using a gas chromatograph equipped with an electron capture detector (ECD).

- Flux Calculation: Calculate the N₂O flux rate based on the change in concentration inside the chamber over time, the chamber volume, and the surface area covered.

Experimental N₂O Workflow

The Researcher's Toolkit

This section outlines key reagents, tools, and methodologies essential for research in greenhouse gas emissions and climate science.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Gas Chromatograph with ECD | Essential for precise measurement of nitrous oxide (N₂O) concentrations in air samples due to high sensitivity [27]. |

| Standardized Emission Factors (IPCC) | Pre-calculated coefficients used to estimate GHG emissions from activity data, ensuring consistency in inventory compilation [26] [25]. |

| Carbon Dioxide Equivalents (CO₂e) | A standardized metric that allows for the comparison of the climate impact of different GHGs by converting them to the equivalent amount of CO₂ with the same warming potential [25]. |

| Static Chamber Systems | A common field apparatus for collecting gas samples from soil or water surfaces to measure the flux of GHGs like CH₄ and N₂O [27]. |

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | A dimensionless index representing the relative radiative forcing of a unit mass of a GHG compared to CO₂ over a chosen time horizon (e.g., 100 years) [25]. |

This guide has provided a comparative profile of CO₂, CH₄, and N₂O, detailing their sources, potency, and measurement. For researchers evaluating biomass against fossil fuels, these profiles underscore a critical distinction: while fossil fuel combustion moves carbon from the slow geological cycle to the atmosphere, biomass systems operate within the faster biogenic carbon cycle [23]. This framework, combined with the standardized data and experimental protocols presented, provides a solid foundation for conducting objective, data-driven assessments of energy technologies and their true impact on global climate.

The quantification of global warming contributions from major energy sources is a critical endeavor in climate science. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the environmental impacts of fossil fuels and biomass energy systems, two dominant contributors to global carbon dioxide emissions. Framed within a broader thesis on comparative environmental impact research, this article synthesizes the most current data on emission factors, carbon neutrality claims, and atmospheric effects. For researchers and scientists engaged in climate impact studies, this analysis offers a rigorous, data-driven comparison of these energy pathways, highlighting the significant differences in their influence on the global carbon budget and climate system.

The fundamental challenge in assessing these energy sources lies in accurately quantifying their complete climate impacts across different timescales and system boundaries. While fossil fuel emissions are relatively straightforward to measure, biomass emissions involve complex biogenic carbon cycles that require careful accounting methodologies. Understanding these distinctions is essential for developing effective climate mitigation strategies and energy policies.

Quantitative Comparison of Emissions and Impacts

Global Emission Profiles and Carbon Budget Status

Table 1: Comparative Global Warming Contributions of Fossil Fuels and Biomass

| Parameter | Fossil Fuels | Biomass (Wood) | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 Emissions per Energy Unit | Coal: 205.3 lb CO2/MMBtu [28] | 213 lb CO2/MMBtu (bone dry) [28] | Direct combustion emissions |

| Efficiency of Power Generation | Coal: 33% (avg); Natural Gas: 43% [28] | ~24% (utility-scale biomass boiler) [28] | Average conversion efficiency |

| Actual CO2 per MWh | Natural gas: 510 lb/MWh [28] | 3,120 lb/MWh (Domtar plant example) [28] | Measured at power plant level |

| Carbon Neutrality Timeframe | Centuries to millennia (geologic timescale) | Decades to centuries (biogenic timescale) [28] | Time to re-sequester emitted CO2 |

| Atmospheric CO2 Contribution | 38.1 billion tonnes in 2025 (record high) [15] | Contributes to immediate atmospheric CO2 pulse [28] | Annual global emissions |

Table 2: Global Carbon Budget and Climate Impacts

| Metric | Current Status | Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Fossil CO2 Emissions (2025) | 38.1 GtCO2 (record high) [15] | 1.1% increase from 2024 [14] |

| Remaining 1.5°C Carbon Budget | 170 GtCO2 (4 years at current emissions) [15] | Virtually exhausted [14] |

| Atmospheric CO2 Concentration | 425.7 ppm (2025 projection) [15] | 52% above pre-industrial levels [14] |

| Historical Emission Growth | 0.3% per year (2014-2025) vs 1.9% (2004-2013) [15] | Progress in deceleration, but insufficient |

Regional and National Contributions

Table 3: National and Regional Emission Profiles (2025 Projections)

| Region | Share of Global Emissions | 2025 Projected Change | Key Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | 32% [15] | +0.4% [14] | Moderate energy growth with strong renewable expansion |

| United States | 13% [15] | +1.9% [14] | Colder weather increasing energy demand |

| European Union | ~8% | +0.4% [14] | Varied progress in decarbonization across member states |

| India | ~8% | +1.4% [14] | Early monsoon reduced cooling demand, strong renewable growth |

| Rest of World | ~39% | +1.1% [14] | Collective growth across developing economies |

Experimental Protocols for Emission Quantification

Global Carbon Budget Assessment Methodology

The Global Carbon Project employs a comprehensive methodology to quantify emissions and sinks across the global carbon cycle. The protocol integrates multiple data sources and modeling approaches to generate annual carbon budgets with uncertainty ranges [15].

Data Collection and Integration:

- National emission inventories from member countries

- Satellite observations of atmospheric CO2 concentrations

- Direct atmospheric measurements from ground stations

- Economic activity data correlated with emission factors

- Land-use change monitoring via remote sensing

Analytical Framework:

- Bottom-up inventories combined with top-down atmospheric constraints

- Multiple bookkeeping models for land-use change emissions

- Ocean and terrestrial biogeochemical models for sink quantification

- Statistical projections for current-year estimates based on energy data

Uncertainty Quantification:

- Multi-model ensembles to capture structural uncertainties

- Statistical analysis of inventory discrepancies

- Propagation of measurement errors through calculation chains

- Transparent reporting of confidence intervals for all estimates

Biomass Carbon Accounting Protocol

The Manomet Study approach provides a comprehensive framework for assessing biomass emissions across full lifecycle and temporal dimensions [28]. This methodology addresses the critical time-dependent factors in biomass carbon neutrality.

Temporal Accounting Framework:

- Establishment of baseline carbon stocks in biomass feedstocks

- Tracking of carbon flows through harvest, transport, and combustion

- Modeling of regrowth trajectories for different biomass sources

- Comparison against reference scenarios (fossil fuels and natural decay)

Key Experimental Metrics:

- Immediate combustion emissions versus natural decomposition rates

- Carbon debt calculation: time to achieve net emission reductions

- Albedo changes and other non-CO2 climate impacts

- Market-mediated impacts on land use and forest management

System Boundary Considerations:

- Direct land-use change emissions from biomass cultivation

- Indirect impacts on agricultural expansion and deforestation

- Fossil fuel inputs for harvesting, processing, and transportation

- Changes in soil carbon stocks from biomass removal

Visualization of Carbon Flow Pathways

Carbon Flow Pathways Comparison This diagram illustrates the fundamental differences between fossil fuel and biomass carbon pathways. The fossil fuel pathway represents a linear, one-way flow of geologically sequestered carbon to the atmosphere, creating a net addition to atmospheric CO2. In contrast, the biomass pathway operates as a cyclic system where carbon circulates between the atmosphere and biosphere, with the critical factor being the timescale of resequestration versus emissions.

Research Reagent Solutions for Emission Analysis

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Emission Quantification Studies

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Atmospheric CO2 Analyzers | Precisely measure CO2 concentrations in air samples | Monitoring atmospheric composition trends; validation of emission inventories [15] |

| Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometers | Distinguish fossil vs biogenic CO2 using carbon-14 dating | Attribution of emission sources; verification of biomass carbon claims [28] |

| Eddy Covariance Flux Towers | Measure net ecosystem exchange of CO2 | Quantifying land carbon sinks; validating terrestrial carbon models [15] |

| Remote Sensing Platforms | Monitor deforestation and land-use change | Tracking emissions from land-use change; assessing biomass feedstock impacts [15] |

| Life Cycle Assessment Software | Model cradle-to-grave environmental impacts | Comprehensive comparison of energy systems; policy decision support [29] |

| Global Climate Models | Project long-term climate responses to emissions | Assessing climate impacts of emission pathways; carbon budget calculations [15] |

Critical Analysis of Carbon Neutrality and Time Factors

The assumption of biomass carbon neutrality represents one of the most contentious issues in climate policy. Current evidence suggests this neutrality is conditional and time-dependent, with critical implications for climate mitigation strategies [28].

Timescale Considerations:

- Immediate emissions: Biomass combustion releases CO2 instantaneously, while natural decomposition occurs over years to decades

- Carbon debt period: The time required for regenerating biomass to resequester emitted carbon creates a temporary warming impact

- Climate urgency: Decades-long carbon debts conflict with immediate emission reduction needs to meet Paris Agreement goals

Systemic Impacts:

- Forest carbon stocks: Harvesting for biomass reduces standing carbon stocks that would otherwise continue sequestering carbon

- Efficiency disparities: Lower conversion efficiency of biomass systems compared to fossil alternatives increases overall emissions per unit energy

- Alternative scenarios: The critical comparison is between biomass emissions and the counterfactual of fossil fuel use plus forest conservation

The empirical data reveals that substituting biomass for fossil fuels typically increases atmospheric CO2 for extended periods, ranging from decades to centuries, depending on feedstock type and forest dynamics. This temporal mismatch between emission pulses and resequestration creates substantial carbon debts that may not be repaid within relevant climate policy timeframes.

The quantitative comparison of fossil fuel and biomass energy systems reveals complex tradeoffs in their global warming contributions. Fossil fuels continue to dominate global emissions, with record highs projected for 2025, while biomass energy systems present their own challenges through potential carbon debts and efficiency limitations. The most critical finding is that both energy sources contribute significantly to atmospheric CO2, albeit through different mechanisms and timescales.

For researchers and policymakers, this analysis underscores the importance of comprehensive carbon accounting that includes temporal dimensions, system efficiency, and alternative land-use scenarios. Meeting climate targets requires not only accelerating the transition from fossil fuels but also ensuring that alternative energy sources like biomass provide genuine emission reductions within relevant climate timeframes. The scientific tools and methodologies outlined here provide a foundation for more accurate assessment and comparison of energy technologies as part of a broader strategy to mitigate global warming.

Measuring Environmental Impact: Methodologies for Life-Cycle Assessment and Emissions Accounting

Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a systematic methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts of energy systems from raw material extraction through final energy conversion. For biomass and fossil fuel systems, this "cradle-to-grave" approach is particularly critical for generating comparable environmental impact data. LCA evaluates all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—including carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and nitrous oxide (N₂O)—across the entire lifespan, converting them into carbon dioxide equivalents (CO₂eq) using Global Warming Potential values for standardized comparison [30]. The standard functional unit for electricity generation is grams of CO₂eq per kilowatt-hour (gCO₂eq/kWh), enabling objective comparison across diverse energy technologies [30].

The application of LCA to biomass energy systems has revealed significant complexities that require careful methodological consideration. Current decision-making largely depends on regional feedstock availability and economic factors, but comprehensive environmental assessments are playing an increasingly critical role in policy and technology development [31]. For biomass systems, LCA must account for diverse factors including feedstock type (agricultural residues, forest residues, energy crops, municipal solid waste), conversion pathways (pyrolysis, gasification, anaerobic digestion), and system boundaries that may include carbon sequestration in soils [31] [32]. When properly harmonized, LCA results provide invaluable insights for policymakers, researchers, and energy professionals seeking to understand the true environmental costs and benefits of energy alternatives.

LCA Methodology and Framework

Standardized LCA Framework Components

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) outlines four distinct phases for conducting life-cycle assessments, ensuring comprehensive and comparable results across studies. The goal and scope definition phase establishes system boundaries, functional units, and impact categories, while the life cycle inventory phase quantifies energy and material inputs and environmental releases [32]. The life cycle impact assessment phase evaluates potential environmental consequences, and the interpretation phase summarizes findings and provides recommendations [32].

For energy systems, LCA encompasses three primary lifecycle stages: upstream processes (resource extraction, feedstock cultivation, and transportation), core conversion processes (combustion, pyrolysis, or other conversion technologies), and downstream processes (waste management, decommissioning, and disposal) [30]. A particular challenge in LCA studies is the variation in methodological choices, which can significantly impact results. Recent harmonization efforts by organizations like the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) have worked to reduce variability in published LCA results by adjusting estimates to consistent sets of methods and assumptions specific to each technology [33].

Critical Methodological Considerations

Several methodological aspects require careful attention in comparative LCAs of biomass and fossil fuels. The treatment of biogenic carbon remains contentious, with debates centering on whether carbon emitted during biomass combustion should be considered carbon-neutral or if timing and sequestration factors should be incorporated [31]. Land use changes—both direct and indirect—can significantly impact carbon stocks and biodiversity, particularly for biomass systems dedicated to energy crops [31]. System boundary delimitation must consistently address by-products, waste streams, and multi-functional processes across all compared systems [32].

Recent research has highlighted the limitations of focusing exclusively on global warming potential (GWP) in LCA studies. A comprehensive review of biomass energy systems identified numerous additional environmental impact categories that must be considered, including acidification potential, eutrophication potential, ozone depletion potential, human toxicity potential, water consumption, and ecotoxicity potential [31]. Standardized LCA frameworks such as ReCiPe and TRACI provide methodologies for evaluating these broader environmental impacts, enabling more holistic comparisons between energy systems [31].

Quantitative Comparison of Biomass and Fossil Fuel Systems

Lifecycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Comprehensive LCA data reveals significant differences in greenhouse gas emissions between energy sources. The following table summarizes harmonized lifecycle GHG emissions for major electricity generation technologies:

Table 1: Lifecycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Electricity Generation Technologies

| Energy Technology | Median GHG Emissions (gCO₂eq/kWh) | Key Emission Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Coal | 1001 [30] | Mining, processing, transportation, combustion |

| Natural Gas | 486 [30] | Extraction, processing, transportation, combustion, methane leakage |

| Oil/Petroleum | 840 [30] | Extraction, refining, transportation, combustion |

| Biomass | Varies significantly by feedstock and technology | Feedstock cultivation, processing, conversion, potential soil C sequestration |

| Nuclear | 13 [30] | Uranium mining, enrichment, plant construction/decommissioning |

| Hydropower | 20-24 [30] | Construction, reservoir emissions (site-dependent) |

| Solar PV | 28-43 [30] | Silicon purification, module manufacturing |

| Wind | 10-14 [30] | Blade, tower, and nacelle production |

Biomass systems demonstrate highly variable emissions profiles depending on multiple factors. NREL's harmonization efforts found that while renewable technologies generally show lower lifecycle GHG emissions than fossil fuels, the central tendencies of all renewable technologies are between 400 and 1,000 g CO₂eq/kWh lower than their fossil-fueled counterparts without carbon capture and sequestration [33].

Comprehensive Environmental Impact Assessment

Beyond greenhouse gas emissions, LCA evaluates multiple environmental impact categories that reveal important trade-offs between energy systems. The following table synthesizes findings across these categories for biomass and fossil fuel systems:

Table 2: Comparative Environmental Impact Profiles Across Multiple LCA Categories

| Impact Category | Fossil Fuel Systems | Biomass Energy Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential | Consistently high across all fossil fuels [30] | Highly variable; can be net-negative with BECCS [31] |

| Acidification Potential | Significant, primarily from sulfur and nitrogen oxides | Can be elevated from fertilizer use in feedstock cultivation [31] [34] |

| Eutrophication Potential | Generally lower than biomass systems | Often significant due to agricultural runoff [31] [34] |

| Water Consumption | High for cooling in thermoelectric plants | Highly variable; irrigation requirements for energy crops [31] |

| Land Use | Primarily for extraction infrastructure | Significant for feedstock cultivation; potential competition with food crops [31] |

| Human Toxicity | Emissions of heavy metals, particulates | Potential pesticide exposure, combustion emissions [31] |

Recent research emphasizes that overemphasizing GWP as the primary impact category risks obscuring significant trade-offs in other environmental areas such as water use, ecotoxicity, and human health [31]. Comprehensive LCA frameworks address these multiple impact categories to provide a more complete picture of environmental performance.

Experimental Protocols for LCA in Energy Research

Standardized LCA Methodology

The experimental protocol for conducting life-cycle assessments of energy systems follows internationally recognized standards with specific adaptations for energy technologies. The goal and scope definition must explicitly state the study's purpose, intended audience, system boundaries, and functional unit—typically 1 kWh of electricity delivered to the grid [32]. The life cycle inventory phase involves collecting quantitative data on all energy and material inputs (feedstock, fuels, electricity, water, fertilizers) and environmental outputs (air emissions, water discharges, solid waste) for every process within the system boundaries [32].

For the life cycle impact assessment, researchers apply characterization factors to convert inventory data into impact category indicators using standardized methods such as TRACI or ReCiPe [31]. The interpretation phase involves evaluating results through sensitivity analysis, uncertainty analysis, and hotspot identification to draw robust conclusions and recommendations [32]. For comparative analyses, all systems must be evaluated using consistent methodological choices, including equivalent system boundaries, impact assessment methods, data quality, and allocation procedures.

Biomass-Specific Methodological Considerations

Experimental protocols for biomass LCA require special considerations beyond standard methodology. Feedstock-specific variations must be accounted for, as agricultural residues, forest residues, energy crops, and algal biomass have distinct environmental profiles [31] [32]. The treatment of soil carbon dynamics significantly influences results, particularly for no-tillage practices that enhance carbon sequestration [34]. Temporal considerations are crucial, as the timing of emissions and sequestration varies across biomass systems, potentially impacting climate change metrics [31].

For biomass conversion technologies, LCA must account for process-specific factors including conversion efficiency, by-product generation, and energy integration [32]. Pyrolysis systems, for instance, produce biochar that may sequester carbon in soils, requiring careful allocation of emissions between multiple products [32]. Technological maturity also influences performance data, with pilot-scale facilities typically showing different environmental profiles than commercial-scale operations.

Diagram: LCA Workflow for Energy Systems

LCA Methodology Workflow - The iterative process of life-cycle assessment follows international standards with feedback loops for refinement.

Biomass Conversion Pathways and Technologies

Major Biomass Conversion Technologies

Biomass can be converted to energy through multiple technological pathways, each with distinct environmental profiles. Thermochemical conversion processes include combustion for heat and power, pyrolysis for bio-oil and biochar production, and gasification for syngas generation [31]. Biochemical conversion pathways utilize anaerobic digestion for biogas production and fermentation for bioethanol generation [31]. Chemical conversion methods include transesterification for biodiesel production from vegetable oils and animal fats [31].

Different conversion technologies yield diverse energy carriers with varying applications. Biomass combustion directly produces heat and electricity, while advanced biofuels like sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) and renewable natural gas (RNG) can displace fossil fuels in hard-to-electrify sectors like aviation and heavy transport [31]. Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) generates negative emissions by combining bioenergy with geological carbon sequestration [31]. The environmental performance of each pathway depends on factors including feedstock type, conversion efficiency, scale of operation, and energy integration.

Diagram: Biomass Conversion Pathways

Biomass Conversion Technology Pathways - Diverse technological routes transform biomass into various energy carriers and products with distinct applications.

Agricultural Management and LCA

Agricultural practices significantly influence the LCA results of biomass energy systems. Research has demonstrated that tillage practices substantially impact environmental outcomes, with reduced tillage and no-tillage systems generally showing better environmental performance due to lower diesel fuel consumption and enhanced carbon sequestration in soils [34]. Fertilizer application represents a major environmental hotspot in biomass production, contributing to eutrophication, acidification, and global warming through nitrous oxide emissions [34].

Studies comparing different cropping systems have found that double cropping systems (two crops per year) can demonstrate better environmental performance for certain impact categories despite more frequent field operations, due to higher total yield and potentially reduced fertilizer requirements [34]. The integration of legume crops in rotations can reduce synthetic nitrogen fertilizer needs, thereby lowering eutrophication and global warming impacts [34]. These agricultural factors must be carefully considered when evaluating the complete lifecycle of biomass energy systems.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Materials for Energy LCA Studies

| Research Tool/Material | Function in LCA Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LCA Software (OpenLCA, SimaPro, GaBi) | Models inventory data and calculates environmental impacts | All LCA phases; provides standardized impact assessment methods [31] |

| Environmental Databases (Ecoinvent, EDGAR) | Provides secondary data for background processes | Inventory phase; supplies emission factors and resource use data [35] |

| Soil Carbon Models | Quantifies carbon sequestration in agricultural systems | Biomass LCAs; estimates soil organic carbon dynamics [34] |

| Gas Chromatographs | Measures methane and nitrous oxide emissions from soils | Experimental validation; field measurements for agricultural stages [34] |

| Elemental Analyzers | Determines carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen content in feedstocks | Feedstock characterization; essential for combustion calculations [32] |

| Bioassay Kits | Assesses ecotoxicity potential of emissions and wastes | Impact assessment; measures human and ecological toxicity [31] |

The selection of appropriate research tools and materials is critical for generating reliable LCA results. LCA software platforms enable researchers to model complex energy systems, apply standardized impact assessment methods, and conduct sensitivity analyses [31]. Environmental databases provide essential background data for electricity mixes, material production, and transportation systems, ensuring consistent inventory development [35]. For biomass-specific studies, agricultural monitoring equipment is necessary to collect primary data on soil emissions and nutrient cycling, reducing reliance on generic emission factors [34].

Specialized analytical equipment supports the characterization of biomass feedstocks and conversion products. Elemental analyzers quantify carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and oxygen content, enabling accurate heating value determinations and combustion calculations [32]. Gas chromatographs with appropriate detectors measure methane and nitrous oxide fluxes from agricultural soils, providing critical primary data for global warming impact assessments [34]. Bioassay kits help evaluate ecotoxicity potential, addressing an impact category that has often been neglected in earlier LCA studies of energy systems [31].

Life-Cycle Assessment provides an indispensable framework for objectively comparing the environmental performance of biomass and fossil fuel energy systems. The standardized methodology of LCA—encompassing goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation—enables comprehensive evaluation of multiple environmental impact categories beyond global warming potential [31] [32]. Current research indicates that while biomass energy systems generally offer advantages over fossil fuels in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, they often involve trade-offs in other impact categories such as eutrophication, acidification, and land use [31] [34].

Methodological harmonization efforts have reduced variability in LCA results, enabling more reliable comparisons across technologies [33]. Nevertheless, important challenges remain in addressing spatial and temporal variations, accounting for soil carbon dynamics, and evaluating the circular economy potential of biomass systems [31]. Future research directions should prioritize the development of standardized methodologies for emerging technologies like BECCS, expand assessment to include a broader range of environmental impact categories, and improve integration of spatial and temporal considerations in LCA models [31]. As the global community strives to address climate change while meeting growing energy demands, LCA will continue to provide critical insights for evidence-based energy policy and technology development.

The classification of biomass as "carbon neutral" is a foundational concept in climate policy and life cycle assessment (LCA), often justifying the substitution of fossil fuels with bio-based energy sources. However, this classification frequently overlooks a critical scientific nuance: the time dependency of carbon neutrality. The common assumption that bioenergy inherently achieves net-zero emissions simplistically compares it to fossil fuels, which introduce new carbon into the atmospheric cycle. In reality, the climate impact of biogenic carbon is governed by the dynamic interplay between the timing of carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions from biofuel combustion and the timing of its re-sequestration through subsequent plant growth [11]. This temporal discrepancy can lead to a period of increased atmospheric CO₂ concentration, a "carbon debt," which may persist for years to decades depending on the biomass source and regeneration cycle [36]. Framing this within comparative environmental impact research of biomass versus fossil fuels reveals that the critical distinction is not merely the source of carbon, but the timescales over which carbon cycles between the atmosphere and the biosphere. This guide objectively compares the performance of biogenic and fossil carbon systems, highlighting the methodological frameworks and quantitative data essential for rigorous research.

Methodological Frameworks for Biogenic Carbon Accounting

Accounting for biogenic carbon in Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) requires specific methodologies to track carbon flows accurately. Researchers have developed several approaches, each with distinct strengths and applications for handling the temporal aspect of biogenic carbon.

Common Accounting Methodologies

0/0 Approach (Carbon Neutrality Approach): This method operates on the default assumption that the amount of CO₂ absorbed during biomass growth is equivalent to the amount released at end-of-life (e.g., through decomposition or combustion), resulting in a net-zero balance. It is simple to apply but ignores the timing of emissions and sequestration, effectively assuming instantaneous carbon cycling [37]. This approach is often embedded in policy frameworks but is increasingly criticized for its oversimplification.

-1/+1 Approach (Flows Accounting): This method meticulously tracks all biogenic carbon flows throughout a product's life cycle. Carbon uptake during biomass growth is recorded as a negative emission (-1), while carbon release at end-of-life is recorded as a positive emission (+1) [37]. This provides a more complete inventory of carbon flows and avoids the potential for misleading results if only the uptake phase is considered. It is widely embraced by standards such as the ILCD handbook, PAS 2050, and ISO 14067 [11].

Dynamic LCA: This approach explicitly accounts for the timing of greenhouse gas emissions and removals. Instead of aggregating emissions over a fixed period (like 100 years), it models the atmospheric decay and impact of emissions over time, providing a more realistic representation of the global temperature response [11]. This is particularly important for systems with long rotation periods, such as forestry.

GWPbio Method: This method, related to Dynamic LCA, incorporates the specific rotation period of the biomass into the characterization factor for biogenic CO₂ emissions. It adjusts the Global Warming Potential (GWP) metric to reflect the fact that the emission of one tonne of biogenic CO₂ has a different impact than one tonne of fossil CO₂, depending on the growth and harvest cycle of the feedstock [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Biogenic Carbon Accounting Methodologies

| Methodology | Core Principle | Handling of Time | Primary Application Context | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0/0 Approach | Assumes net-zero balance between uptake and release. | Static; time is ignored. | Policy frameworks, simplified screenings. | Simplicity and ease of application. | Fails to represent real-world climate impacts over time. |

| -1/+1 Approach | Tracks all biogenic carbon inflows and outflows. | Static inventory; timing is not modeled. | Compliance with EN 15804, PAS 2050, ISO 14067. | Completeness and transparency of carbon flows. | Does not differentiate between short and long-term carbon storage. |

| Dynamic LCA | Models the atmospheric load of GHGs over time. | Explicitly dynamic; time is a central variable. | Research on forestry products, long-lived biomaterials. | Most accurate representation of temporal climate impact. | High data intensity and computational complexity. |

| GWPbio | Adjusts the GWP factor based on biomass rotation period. | Semi-dynamic; incorporates growth cycle duration. | Comparative assessment of different biomass feedstocks. | Improves accuracy over static methods with less complexity than full Dynamic LCA. | Still a simplified model of a complex biogeochemical system. |

Reporting Standards and Guidelines

Reporting frameworks have evolved to demand greater transparency in biogenic carbon accounting. The revised EN 15804+A2 standard, a core reference for Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), now requires that the Global Warming Potential (GWP) is reported in disaggregated categories: GWP-fossil, GWP-biogenic, and GWP from land use change (luluc) [37]. This separation prevents the netting-out of biogenic flows from fossil emissions, allowing researchers to assess their impacts independently. Furthermore, major reporting protocols like the Greenhouse Gas Protocol (GHGP) and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) require organizations to disclose biogenic emissions separately, often "outside of scopes," to provide a complete picture of a company's carbon footprint and its dependence on biomass [38].

Quantitative Comparison: Biomass vs. Fossil Fuels

A rigorous comparison requires examining quantitative data on emissions, resource use, and environmental impact across the entire life cycle.

Lifecycle Emissions and Carbon Cycle Dynamics

The fundamental difference between biomass and fossil fuels lies in their participation in the carbon cycle. Fossil fuel combustion releases geologically ancient carbon that has been sequestered for millions of years, representing a net addition of CO₂ to the atmosphere [12] [39]. In contrast, biofuels are part of a faster, "green carbon cycle" where carbon is continuously cycled between the atmosphere and the biosphere [11]. When sourced and managed sustainably, biofuels can offer significant emission reductions.

Lifecycle assessments indicate that sustainably produced biofuels can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50% to 70% compared to conventional fossil fuels [12]. For instance, sugarcane ethanol, particularly from Brazil, shows some of the highest emission reductions due to its efficient growth profile [12]. However, these benefits are contingent on sustainable land-use practices. Conversely, the U.S. EPA notes that depending on the feedstock and production process, biofuels can sometimes emit more GHGs than fossil fuels on an energy-equivalent basis, particularly if their production induces land-use change [40].