Biomass Gasification and Pyrolysis: Principles, Optimization, and Advanced Applications for Sustainable Energy

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of biomass thermochemical conversion, focusing on gasification and pyrolysis.

Biomass Gasification and Pyrolysis: Principles, Optimization, and Advanced Applications for Sustainable Energy

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of biomass thermochemical conversion, focusing on gasification and pyrolysis. Tailored for researchers and scientists, it explores the fundamental mechanisms, operational methodologies, and optimization strategies for these processes. The content covers foundational principles, reactor design, key operational parameters, and advanced approaches like catalytic applications and feedstock co-processing. It further examines current research trends, including kinetic studies and synergistic effects, offering a critical perspective on technology validation and comparative performance for producing hydrogen-rich syngas and high-value biofuels.

Understanding Thermochemical Conversion: The Science Behind Biomass Pyrolysis and Gasification

Biomass pyrolysis and gasification are two pivotal thermochemical conversion processes at the forefront of renewable energy and sustainable fuel research. As the global community intensifies its search for alternatives to fossil fuels, understanding the core principles, operational parameters, and distinct outputs of these technologies becomes paramount for researchers, scientists, and industry professionals [1]. These processes enable the conversion of abundant, renewable organic materials—from agricultural residues to municipal solid waste—into valuable energy carriers, biofuels, and chemicals, thereby supporting decarbonization strategies and circular economy models [2] [3].

Framed within a broader thesis on biomass conversion research, this guide provides a detailed technical examination of pyrolysis and gasification. It delves beyond superficial descriptions to explore fundamental reaction mechanisms, quantitative process parameters, and advanced experimental methodologies. The content is structured to serve as a comprehensive reference, equipping professionals with the knowledge needed to navigate the technical complexities and research challenges inherent in these technologies, from laboratory-scale investigations to industrial-scale implementation [2] [4].

Core Principles and Process Fundamentals

Defining Pyrolysis: Mechanism and Products

Pyrolysis is the thermal decomposition of carbon-based biomass occurring in the complete absence of an oxidizing agent (oxygen) [5] [6]. The process relies on external heating to break down the complex polymeric structure of biomass—primarily cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—into smaller molecules across a temperature range typically between 250°C and 700°C [2] [7]. The fundamental objective is to maximize the yield of desired products—bio-oil, biochar, and syngas—by carefully controlling operational parameters.

The chemistry of pyrolysis involves a series of simultaneous and sequential reactions, including dehydration, depolymerization, fragmentation, and secondary cracking. The relative yields of the three main product fractions are highly dependent on the process conditions, particularly heating rate and temperature [3]. For instance, high heating rates and moderate temperatures favor liquid bio-oil, while slower heating rates and lower temperatures maximize solid biochar production. The gaseous product, or syngas, primarily consists of hydrogen (H₂), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and light hydrocarbons like methane (CH₄) [7].

Defining Gasification: Mechanism and Products

Gasification transforms carbonaceous feedstock into a combustible gaseous mixture known as synthesis gas (syngas) through partial oxidation with a controlled, limited amount of an oxidizing agent, such as oxygen, air, or steam [5] [2]. It is not a single-step process but rather a sequence of interconnected thermochemical stages that occur as the biomass travels through the gasifier. The core purpose of gasification is to maximize the yield and quality of syngas, which serves as a versatile platform for power generation, fuel synthesis, and chemical production [7].

The gasification process encompasses four distinct stages [2] [7]:

- Drying (below 150°C to ~250°C): Evaporates residual moisture from the feedstock.

- Pyrolysis (250°C to 700°C): Devolatilizes the dry biomass into char, tar, and pyrolysis gases. This step underscores that pyrolysis is an integral, inseparable sub-process within gasification.

- Oxidation (700°C to 1500°C): Exothermic reactions between the volatiles and the supplied oxidant release the heat necessary to drive the subsequent endothermic reactions.

- Reduction (800°C to 1100°C): The key syngas-producing stage where the hot char reacts with CO₂ and steam to form CO and H₂ via the Boudouard and water-gas reactions, respectively.

The final syngas is primarily composed of H₂, CO, CH₄, and CO₂, with its specific composition and heating value heavily influenced by the gasifying agent used [2]. For example, using oxygen or steam yields a medium-heating-value syngas (10-18 MJ/Nm³), whereas air gasification produces a low-heating-value gas (4-7 MJ/Nm³) due to nitrogen dilution [2].

Key Differences and Comparative Analysis

The primary distinction between pyrolysis and gasification lies in the oxygen environment and the consequent primary products [5] [6]. Pyrolysis occurs in a strictly oxygen-free environment, while gasification intentionally introduces a limited, sub-stoichiometric amount of an oxidant. This fundamental difference dictates the reaction pathways, energy balance, and final output of each process.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Biomass Pyrolysis and Gasification

| Feature | Pyrolysis | Gasification |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Presence | Complete absence [5] | Limited, controlled amount (partial oxidation) [5] |

| Primary Objective | Produce bio-oil, biochar, and syngas [6] | Maximize syngas production [5] [7] |

| Main Products | Bio-oil, biochar, syngas [5] | Syngas (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄), with smaller amounts of char and ash [5] [2] |

| Typical Operating Temperature | 250°C - 700°C [2] [7] | 800°C - 1100°C (Reduction zone) [2] |

| Energy Requirement | Endothermic (requires external heat) | Autothermal (heat from partial oxidation drives the process) |

| Key Applications | Bio-oil for fuel; biochar for soil amendment, industry; syngas for energy [3] [6] | Power generation, H₂ production, chemical synthesis (e.g., BioSNG, ammonia) [2] [7] |

It is crucial to recognize that the boundary between pyrolysis and gasification is not always absolute. Research indicates a seamless transition, as oxygen-containing species generated during pyrolysis (like H₂O and CO₂) can act as oxidizing agents in subsequent reactions, especially at higher temperatures [4]. Furthermore, gasification can only proceed after pyrolysis has occurred, highlighting their intrinsic linkage [4].

Table 2: Quantitative Product Yields and Efficiencies

| Parameter | Pyrolysis | Gasification |

|---|---|---|

| Syngas Yield | Lower | High; up to ~90% at elevated temperatures [2] |

| Syngas Heating Value | Varies with process | 4-7 MJ/Nm³ (air), 10-18 MJ/Nm³ (O₂/steam) [2] |

| Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE) | Not typically used as a metric | Typically 63-66%; up to 76.5% reported for specific feedstocks [2] |

| Char/Biochar Yield | Can be the primary product (e.g., 49% yield from rice husks [3]) | Smaller byproduct [5] |

| Mass/Volume Reduction of MSW | Not the primary focus | 70-80% mass reduction; 80-90% volume reduction [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A Standard Fixed-Bed Pyrolysis Protocol for Biochar Production

The following protocol, adapted from recent research, outlines a method for producing and characterizing biochar in a laboratory-scale fixed-bed reactor [3].

Objective: To convert a specified biomass feedstock (e.g., rice husks, woody biomass) into biochar and characterize the resulting products' yield and properties.

Materials and Equipment:

- Feedstock: Pre-dried and milled biomass (particle size 0.5-2.0 mm).

- Reactor: Tubular fixed-bed reactor (e.g., quartz or stainless steel).

- Furnace: Electric furnace with precise temperature controller (±5°C).

- Gas Supply: High-purity nitrogen (N₂) cylinder (>99.99%) with mass flow controller.

- Condensation System: Series of condensers maintained at low temperature (e.g., 0-4°C) to collect bio-oil.

- Gas Collection: Gas bags or a gasometer for non-condensable syngas collection.

- Analytical Instruments: Syringe for gas sampling, Gas Chromatograph (GC) with TCD/FID detectors, Surface Area and Porosity Analyzer (BET method), Ultimate Analyzer (CHNS/O).

Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: Dry the biomass at 105°C for 24 hours to determine baseline moisture content. Sieve to obtain the desired particle size fraction.

- Reactor Loading: Place a known mass of dried biomass (e.g., 20.0 g) into the reactor tube.

- System Purging: Seal the reactor and initiate a flow of N₂ (e.g., 0.5 L/min) for at least 30 minutes to ensure a complete inert atmosphere.

- Pyrolysis: Ramp the furnace temperature to the target set point (e.g., 500°C) at a defined heating rate (e.g., 10°C/min). Maintain the final temperature for a specified residence time (e.g., 30 minutes).

- Product Collection:

- Syngas: Collect the non-condensable gas in gas bags at regular intervals (e.g., every 5 minutes) for compositional analysis via GC.

- Bio-oil: The volatile vapors are passed through the condensation train where the condensable fraction (bio-oil) is collected. Weigh the total bio-oil collected after the experiment.

- Biochar: After the experiment, cool the reactor to room temperature under a continuous N₂ flow. Carefully remove and weigh the solid residue (biochar).

- Product Characterization:

- Calculate the product yields on a mass basis.

- Analyze the biochar for specific surface area (BET), pore volume, and elemental composition (Ultimate Analysis).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Pyrolysis Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Nitrogen (N₂) Gas | Creates and maintains an inert (oxygen-free) atmosphere inside the reactor, which is the defining condition for pyrolysis. |

| Biomass Feedstock | The raw material for conversion. Characterized by Proximate and Ultimate Analysis to understand its behavior during thermal decomposition. |

| Fixed-Bed or Fluidized-Bed Reactor | The core vessel where the thermal decomposition takes place. The design impacts heat transfer, residence time, and product spectrum. |

| Condensation Train | A series of cooled vessels that rapidly quench hot vapors to separate and collect the liquid bio-oil product. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) | Essential analytical equipment for separating and quantifying the components of the non-condensable syngas (e.g., H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄). |

| Catalysts (e.g., Ni-based, Zeolites) | Used in catalytic pyrolysis to lower activation energies, alter reaction pathways, and improve the quality/yield of desired products like bio-oil. |

A Protocol for Analyzing Operational Variables via Multivariate Regression

A recent study employed Multivariate Regression Analysis (MRA) to quantitatively rank the impact of various operational parameters on pyrolysis and gasification outputs [4]. This methodology provides a powerful, data-driven approach for process optimization.

Objective: To quantitatively determine which operational variable (e.g., temperature, catalyst, carrier gas type) has the most significant effect on a specific process output (e.g., H₂ yield, bio-oil yield).

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Data Sourcing: Collect a large dataset (e.g., 387 data points from literature) from peer-reviewed publications on biomass pyrolysis and gasification [4].

- Variable Definition: Independent variables include both continuous (e.g., temperature, H/C ratio) and categorical data (e.g., catalyst type: Ni-based, dolomite, none; carrier gas: N₂, CO₂, steam).

- Data Transformation: For a fair comparison, continuous variables are binned into categorical ranges (e.g., temperature ranges: <500°C, 500-700°C, >700°C).

Multivariate Regression Analysis (MRA):

- Model Formulation: The MRA model is structured as:

Output = β₀ + β₁(Var₁) + β₂(Var₂) + ... + βₙ(Varₙ), where β represents the regression coefficient. - Coefficient Interpretation: A positive β indicates a promoting effect on the output, while a negative β indicates an inhibitory effect. The magnitude of β reflects the strength of the influence.

- Statistical Validation: The p-value for each variable is calculated to determine the statistical significance of its impact (typically p < 0.05 is considered significant).

Key Findings from MRA: The analysis revealed that temperature is the most dominant and statistically significant parameter for increasing gas yield and H₂ concentration in syngas. The use of specific catalysts (e.g., Ni-based) and certain carrier gases (e.g., steam) also showed strong, positive effects, but their impact was generally secondary to temperature [4].

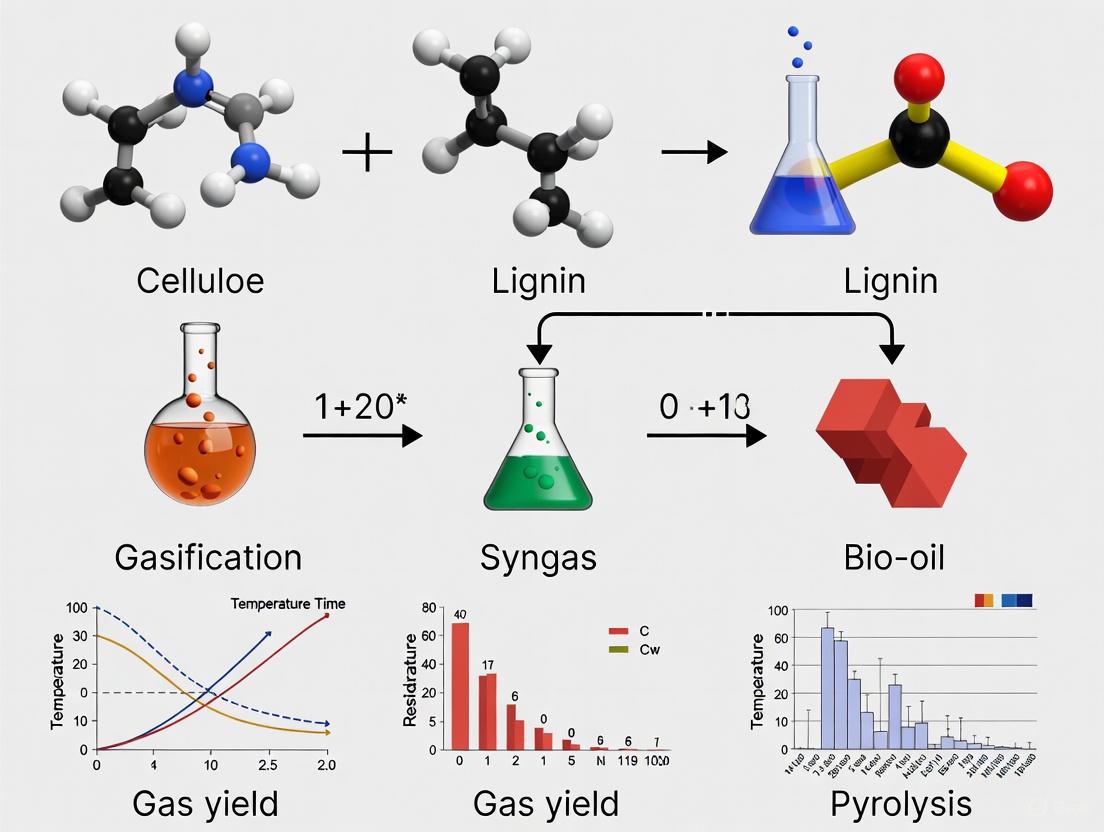

Process Visualization and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the logical sequence of stages within a gasification reactor and the experimental workflow for the data-driven analysis of operational parameters.

Gasification Process Stages

Experimental Analysis Workflow

Pyrolysis and gasification represent two distinct yet intrinsically linked pathways for the thermochemical valorization of biomass. The definitive factor differentiating them is the oxygen environment, which directly governs the chemical reactions, energy balance, and final product slate. Pyrolysis, an endothermic process occurring in an oxygen-free environment, is optimized for producing a trio of outputs: bio-oil, biochar, and syngas. In contrast, gasification, which is partially oxidative and often autothermal, is primarily engineered to maximize the yield of syngas for applications in power generation, hydrogen production, and chemical synthesis [5] [2] [6].

For researchers and engineers, the choice between these technologies is not merely academic but has profound practical implications. Process optimization hinges on a deep understanding of the influential parameters. Quantitative analyses consistently identify temperature as the most critical variable for controlling gas yield and composition, followed by the use of catalysts and the selection of the gasifying medium [4]. The ongoing advancement of these technologies is being accelerated by sophisticated modeling approaches, including computational fluid dynamics (CFD) and data-driven machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) techniques, which enhance predictive accuracy and operational control [2] [8] [9].

Despite the maturity of the underlying science, challenges in scaling and commercialization persist. Issues such as tar formation and management in gasification, the need for consistent feedstock quality, and achieving economic viability at scale remain active areas of research and development [2] [1] [10]. As global efforts to transition toward a circular, low-carbon economy intensify, pyrolysis and gasification are poised to play an increasingly critical role. They offer a technologically robust means of transforming abundant biomass and waste streams into clean, sustainable energy and valuable chemical precursors, thereby contributing significantly to energy security and environmental sustainability [3] [7].

Biomass conversion technologies represent a critical pathway for sustainable energy production and chemical synthesis in the context of global efforts to achieve carbon neutrality. Thermochemical processes, including drying, pyrolysis, and gasification, enable the transformation of diverse biomass feedstocks into valuable products such as biofuels, biochar, and syngas. These sequential stages form the foundational framework for biomass valorization, each contributing distinct chemical and physical transformations that ultimately determine the quality and application of the final products [11] [2]. Understanding the intricacies of these stages is essential for researchers and engineers working to optimize conversion efficiency, product yield, and economic viability.

The interdependence of these stages creates a complex system where operational parameters in one stage significantly influence downstream processes and outcomes. Within the broader context of biomass gasification and pyrolysis research, elucidating these sequential stages provides critical insights for reactor design, process optimization, and catalyst development [12] [11]. This technical guide examines the fundamental mechanisms, experimental methodologies, and technical parameters governing each conversion stage, providing a comprehensive reference for research and development in advanced biomass conversion systems.

The Fundamental Stages of Biomass Conversion

Biomass thermochemical conversion proceeds through three primary sequential stages: drying, pyrolysis, and gasification. Each stage occurs under specific temperature ranges and operational conditions that drive distinct physical and chemical transformations. The progression between stages involves complex heat and mass transfer phenomena that ultimately determine conversion efficiency and product distribution.

The following diagram illustrates the sequential relationship between these stages and their primary outputs:

Table 1: Operational Temperature Ranges for Biomass Conversion Stages

| Conversion Stage | Temperature Range | Primary Process | Atmosphere |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drying | <150°C - 250°C | Moisture evaporation | Inert or air |

| Pyrolysis | 250°C - 700°C | Devolatilization | Absence of oxygen |

| Gasification | 700°C - 1500°C | Partial oxidation | Controlled oxygen/steam |

The sequential nature of these processes is particularly evident in gasification systems, where drying and pyrolysis stages precede the final gasification reactions [2]. In integrated gasification systems, all three stages occur within a single reactor vessel, with temperature zones established to facilitate each transformation stage. The products from earlier stages undergo significant morphological and chemical changes as they progress through increasing temperature regimes, ultimately resulting in the synthesis gas characteristic of complete gasification [13] [2].

Stage 1: Drying

Process Mechanisms

The drying stage represents the initial thermal treatment of biomass, occurring at temperatures below 150°C to 250°C, during which moisture evaporates from the biomass structure [2]. This endothermic process removes both surface moisture (free water) and inherent moisture (bound water) through heat transfer mechanisms that supply the latent heat of vaporization. Efficient moisture removal is critical for subsequent thermochemical processes, as residual moisture negatively impacts energy efficiency by requiring additional thermal input during pyrolysis and gasification stages [13].

The drying kinetics are influenced by multiple factors including biomass particle size, porosity, initial moisture content, and the thermal properties of the specific biomass feedstock. The rate of moisture migration from the biomass interior to the surface, and subsequent evaporation from the surface, governs the overall drying efficiency. For biomass with high moisture content, such as sewage sludge (which can contain up to 98% water), pre-drying is essential to reduce moisture to below 15% for thermal processes [13].

Experimental Protocols

Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) for Drying Kinetics:

- Sample Preparation: Commence with biomass comminution to specific particle sizes (typically 0.5-2.0 mm). Precisely measure initial mass and moisture content.

- Instrument Setup: Utilize a thermogravimetric analyzer with precise temperature control. Employ inert purge gas (N₂) at 100 mL/min flow rate.

- Temperature Program: Implement a dynamic heating regime from ambient temperature to 250°C at rates of 10-50°C/min.

- Data Collection: Continuously monitor mass loss with temperature increase. Determine moisture content from mass differential between initial and post-drying samples.

- Kinetic Analysis: Apply thin-layer drying models to describe drying behavior and calculate effective moisture diffusion coefficients.

Stage 2: Pyrolysis

Process Mechanisms

Pyrolysis involves the thermal decomposition of biomass in the complete absence of oxygen at temperatures ranging from 250°C to 700°C [14] [2]. During this stage, complex organic polymers in biomass—cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—undergo irreversible thermochemical degradation through cleavage of chemical bonds, resulting in the production of solid (biochar), liquid (bio-oil), and gaseous products [14] [13]. The process consists of multiple simultaneous and consecutive reactions including dehydration, depolymerization, isomerization, aromatization, and decarboxylation [13].

The distribution of pyrolysis products depends significantly on process parameters, particularly temperature and heating rate. Cellulose decomposition occurs between 315-400°C, hemicellulose degrades at 220-315°C, while lignin—the most stable biomass component—decomposes across a broad temperature range from 160°C to 900°C [13]. Biochar production increases with higher lignin content, while cellulose and hemicellulose contribute more significantly to bio-oil yields [13]. At higher temperatures (600-900°C), biochar yield decreases to approximately 19% due to enhanced devolatilization, while surface area and carbon content increase [15].

Experimental Protocols

Kinetic Analysis of Biomass Pyrolysis:

- Reactor System: Employ a stainless steel semi-batch reactor with controlled atmosphere capability.

- Process Parameters: Set temperatures between 400-900°C, heating rate of 10°C/min, holding time of 45 minutes, and N₂ flow rate of 100 mL/min [15].

- Product Collection: Condense bio-oil using a condensation train maintained at 0-4°C. Collect non-condensable gases in gas bags or specialized containers.

- Characterization Techniques:

- Biochar: Conduct proximate analysis, ultimate analysis, heating value determination, BET surface area analysis, TGA, FTIR, and FE-SEM [15].

- Bio-oil: Analyze composition using GC-MS, determine water content via Karl Fischer titration, and measure viscosity and pH.

- Gas: Quantify composition using GC-TCD/FID.

Table 2: Pyrolysis Product Distribution vs. Temperature

| Temperature | Biochar Yield | Bio-Oil Yield | Gas Yield | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 400°C | High (~35%) | Moderate | Low | Biochar suitable for soil amendment [15] |

| 600°C | Moderate (~25%) | High | Moderate | Enhanced bio-oil production [14] |

| 900°C | Low (~19%) | Low | High | Biochar with high carbon content (76.02 wt.%), surface area, and HHV (36.97 MJ/kg) [15] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Pyrolysis Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pyrolysis Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen (N₂) Gas | Creates inert atmosphere | Prevents oxidative degradation during pyrolysis |

| Calcined Dolomite (CaMg(CO₃)₂) | Tar cracking catalyst | Reduces tar content in pyrolysis vapors [12] |

| Ni-Based Catalysts | Tar reforming catalyst | Enhances gas yield and quality through catalytic tar decomposition [12] |

| Alkali Metal Carbonates | Catalytic pyrolysis | Lowers tar yield and modifies product distribution [12] |

| Quartz Sand | Fluidizing medium | Provides heat transfer in fluidized bed reactors |

Stage 3: Gasification

Process Mechanisms

Gasification constitutes the final stage in the biomass conversion sequence, occurring at temperatures between 700°C and 1500°C through the partial oxidation of pyrolysis products with a controlled supply of oxygen, air, steam, or their mixtures [14] [2]. This complex process transforms the solid carbonaceous materials from pyrolysis into a combustible synthesis gas (syngas) primarily composed of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen (H₂), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and methane (CH₄) [14] [11]. Unlike pyrolysis, which occurs in the absence of oxygen, gasification involves controlled oxidation reactions that provide the necessary thermal energy for endothermic gasification reactions [14].

The gasification stage encompasses multiple heterogeneous and homogeneous reactions, including the Boudouard reaction (C + CO₂ 2CO), water-gas reaction (C + H₂O CO + H₂), water-gas shift reaction (CO + H₂O CO₂ + H₂), and methane reforming (CH₄ + H₂O CO + 3H₂) [11]. The composition of the resulting syngas depends on operational parameters including temperature, pressure, equivalence ratio (ER), gasifying agent, and catalyst presence. Gasification typically achieves 70-80% reduction in mass and 80-90% reduction in volume of the original feedstock [2].

Tar Formation and Catalytic Cracking

A significant challenge in biomass gasification is tar formation—complex hydrocarbons that condense at lower temperatures, causing operational problems in downstream equipment [12]. Tar content in syngas can vary from 0.5 to 100 g/m³, while most applications require tar levels below 0.05 g/m³ [12]. Catalytic tar cracking represents a crucial technology for addressing this challenge, with several catalyst classes demonstrating effectiveness:

Ni-Based Catalysts: Extensive application in tar reforming due to high activity in breaking C-C and C-H bonds. Commercial Ni-catalysts are available but susceptible to deactivation by sulfur compounds and carbon deposition [12].

Dolomite Catalysts: Natural calcium-magnesium ore (CaMg(CO₃)₂) that shows high efficiency for tar removal when calcined. Cost-effective but exhibits mechanical fragility [12].

Alkali Metal Catalysts: Carbonates, oxides, and hydroxides of alkali metals effectively decompose tar during catalytic gasification [12].

Novel Metal Catalysts: Rhodium, palladium, platinum, and ruthenium demonstrate high tar conversion rates and resistance to deactivation, though cost presents a limitation [12].

The following diagram illustrates the primary gasification reactor configurations and their operational principles:

Experimental Protocols

Catalytic Gasification with Tar Analysis:

- Reactor Configuration: Employ a fluidized bed gasification system with catalytic reformer unit.

- Process Parameters: Maintain temperature between 800-900°C for gasification zone and 700-900°C for catalytic reformer.

- Catalyst Preparation: Synthesize or procure catalysts (Ni-based, dolomite, etc.). Activate under specified conditions (e.g., reduction for Ni-catalysts, calcination for dolomite).

- Tar Sampling: Implement solid phase adsorption (SPA) method or tar protocol for representative sampling.

- Analytical Methods:

- Syngas Composition: Analyze using GC-TCD for permanent gases and GC-FID for hydrocarbons.

- Tar Characterization: Employ GC-MS for qualitative and quantitative analysis of tar compounds.

- Catalyst Characterization: Conduct BET surface area, XRD, SEM/EDS, and TPR/TPO analyses to assess catalyst properties and deactivation.

Integrated Process Analysis

The sequential stages of biomass conversion function as an integrated system where operational parameters in each stage significantly influence overall process efficiency and product distribution. The interconnection between pyrolysis and gasification is particularly critical, as the products from pyrolysis (char, vapors, and gases) become the feedstock for subsequent gasification reactions [13] [2]. Optimizing the complete sequence requires careful consideration of heat and mass transfer between stages, as well as the potential for catalytic interactions between biomass components and minerals present in the feedstock.

Advanced gasification systems often integrate all three stages within a single reactor with distinct temperature zones, while other configurations may employ separate reactors for pyrolysis and gasification to allow for independent optimization of each stage [2]. The choice between integrated and separated configurations depends on factors including feedstock characteristics, scale of operation, desired products, and economic considerations. Future research directions focus on enhancing process integration, developing multifunctional catalysts that operate across multiple stages, and implementing advanced process control strategies to optimize the entire conversion sequence [11] [2].

Primary Reactions and Chemical Mechanisms Governing Product Output

Biomass pyrolysis and gasification are thermochemical conversion processes that transform carbon-based feedstocks into valuable energy products through controlled heating in oxygen-limited environments. Within the broader context of biomass conversion research, understanding the primary reactions and chemical mechanisms is fundamental to optimizing product output, whether the target is syngas, bio-oil, or biochar. These processes involve a complex sequence of interrelated chemical reactions, largely governed by feedstock composition and operational parameters, which dictate the yield, composition, and quality of the final products. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of these core mechanisms, offering researchers and scientists a detailed framework for experimental design and process optimization. By systematically examining biomass composition, degradation pathways, staged process mechanisms, and critical reaction kinetics, this review establishes the scientific foundation necessary for advancing process efficiency and product valorization in renewable energy systems.

Biomass Composition and Degradation Pathways

Biomass is not a homogeneous substance but a complex composite of structural components and organic polymers, each with distinct thermal degradation behaviors. The six primary biomass components undergo characteristic reactions during thermal conversion, including dehydration, depolymerization, and decarboxylation, which collectively influence pyrolysis product yields and composition [16]. The proportional composition of these components varies significantly across different biomass feedstocks, directly impacting their thermal degradation kinetics and product distribution.

Table 1: Primary Biomass Components and Their Characteristic Degradation Reactions

| Biomass Component | Primary Degradation Reactions | Key Products Formed | Temperature Range (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose | Depolymerization, dehydration, decarboxylation | Levoglucosan, hydroxyacetaldehyde, CO, CO₂ | 300-400 |

| Hemicellulose | Deacetylation, depolymerization | Acetic acid, furfural, CO, CO₂ | 200-300 |

| Lignin | Demethoxylation, side-chain cleavage, dehydrogenation | Phenols, catechols, guaiacols, char | 250-500 |

| Extractives | Volatilization, fragmentation | Terpenes, fatty acids, sterols | Varies widely |

| Minerals (Ash) | Catalytic effects on other reactions | Inorganic residues | >500 |

The thermal decomposition of cellulose, a linear polymer of glucose, primarily proceeds through depolymerization to form levoglucosan, followed by secondary cracking reactions that produce lighter oxygenates and gases. Hemicellulose, a heterogeneous branched polymer, decomposes at lower temperatures due to its amorphous structure, predominantly yielding acetic acid through deacetylation. Lignin, a complex phenolic macromolecule, undergoes radical-driven decomposition across a broad temperature range, producing a wide spectrum of phenolic compounds and contributing significantly to char formation due to its aromatic structure. The distinct thermal stability and decomposition pathways of these components result in characteristic product signatures that can be targeted through controlled process conditions [16].

Staged Process Mechanisms

The thermochemical conversion of biomass proceeds through a series of sequential yet often overlapping stages. The complete process, from initial heating to final gasification, can be visualized as the following interconnected stages:

Biomass Conversion Stages

Drying and Pyrolysis

The initial drying stage occurs at temperatures below 150°C and completes around 250°C, physically removing moisture content from the biomass without significant chemical decomposition [2]. This endothemic process consumes substantial energy but is crucial for ensuring efficient subsequent thermochemical reactions.

The pyrolysis (devolatilization) stage follows, occurring between 250°C and 700°C, where the fundamental chemical transformation of dry biomass begins through heat-induced bond scission in the absence of oxygen [17] [2]. This complex network of parallel and consecutive reactions includes:

Primary Pyrolysis: The initial thermal breakdown of biomass polymers (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) into smaller fragments, producing primarily:

- Primary volatiles (condensable and non-condensable)

- Solid char (carbon-rich residue)

Secondary Reactions: The further cracking and reforming of primary volatiles either in the gas phase or through interactions with the hot char surface, significantly influencing the final product distribution.

The relative yields of gas, liquid (bio-oil), and solid (char) products are highly dependent on the heating rate, final temperature, and vapor residence time. Slow pyrolysis with low heating rates and long residence times maximizes char yield (10-35%), while fast pyrolysis at moderate temperatures (around 500°C), high heating rates, and short vapor residence times maximizes liquid bio-oil yield [17].

Gasification Stages

Gasification extends pyrolysis by introducing a controlled amount of oxidizing agent (air, oxygen, or steam), leading to subsequent oxidation and reduction stages that convert pyrolysis products into a combustible synthesis gas (syngas) [2].

The oxidation stage occurs between 700°C and 1500°C, where a portion of the volatile products and char from pyrolysis undergoes exothermic combustion with the supplied oxidant. Key oxidation reactions include:

These reactions release substantial heat that drives the overall endothermic gasification process. The reduction stage then follows at temperatures typically ranging from 800°C to 1100°C, where the primary gasification reactions occur in the absence of oxygen, converting the remaining carbonaceous material and combustion products into the final syngas [2]. The critical heterogeneous and homogeneous reactions governing this stage are detailed in Section 4.

Critical Gasification Reactions and Kinetics

Following pyrolysis, the resulting char and volatiles undergo further transformation through gasification reactions, which are critical for determining the final syngas composition and quality. These reactions occur primarily during the reduction stage and can be categorized as heterogeneous (gas-solid) or homogeneous (gas-gas).

Table 2: Primary Gasification Reactions and Their Thermodynamic Characteristics

| Reaction Name | Chemical Equation | ΔH (kJ/mol) | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boudouard Reaction | C + CO₂ ⇌ 2CO | +172 | High temperature (>800°C) favors CO production |

| Water-Gas Reaction | C + H₂O ⇌ CO + H₂ | +131 | Steam-to-carbon ratio, temperature |

| Methanation | C + 2H₂ ⇌ CH₄ | -75 | Favored at high pressure, low temperature |

| Water-Gas Shift | CO + H₂O ⇌ CO₂ + H₂ | -41 | Temperature, catalyst presence |

| Steam-Methane Reforming | CH₄ + H₂O ⇌ CO + 3H₂ | +206 | High temperature, steam concentration |

The Boudouard reaction (C + CO₂ 2CO) is a key endothermic pathway for CO production, becoming thermodynamically favorable above approximately 800°C. The water-gas reaction (C + H₂O CO + H₂) is equally critical, consuming steam to produce syngas with a high hydrogen content. The rate of these heterogeneous char gasification reactions is influenced by intrinsic carbon reactivity, ash catalytic effects, and pore diffusion limitations [17].

Homogeneous gas-phase reactions, particularly the water-gas shift reaction (CO + H₂O CO₂ + H₂), play a vital role in determining the final H₂/CO ratio in the syngas, which is crucial for downstream synthesis applications. Simultaneously, steam-methane reforming (CH₄ + H₂O CO + 3H₂) works to reduce tar and methane concentrations while increasing hydrogen yield, especially at temperatures exceeding 800°C [17] [2].

The overall gasification process efficiency and syngas composition are heavily influenced by operational parameters. Temperature is the dominant factor, with increased temperature generally enhancing reaction rates and gas yield while reducing tar and char formation. The choice of gasifying agent also significantly impacts the syngas heating value: air gasification produces low-calorific gas (4-7 MJ/Nm³), oxygen gasification yields medium-calorific gas (10-12 MJ/Nm³), while steam gasification can produce higher quality gas (15-20 MJ/Nm³) [17] [2].

Experimental Methodologies for Mechanism Investigation

Reactor Configurations and Experimental Setups

Investigating primary reactions requires carefully designed experimental systems that enable control over key parameters and accurate product characterization. Different reactor configurations are employed based on the specific research objectives:

- Fixed-Bed Reactors: Ideal for fundamental kinetic studies of reaction mechanisms due to well-defined flow patterns and simpler modeling. Configurations include updraft, downdraft, and cross-draft, differing in the direction of fuel and gas flows [2].

- Fluidized-Bed Reactors: Provide excellent heat and mass transfer, enabling nearly isothermal conditions and better temperature control, which is crucial for studying intrinsic kinetics [17].

- Entrained-Flow Reactors: Feature very short residence times (seconds), suitable for studying primary pyrolysis reactions and fast kinetics at high temperatures [2].

A representative experimental setup for pyro-gasification studies, as described in the MR system, typically includes several key components: a feeding system, a main reactor (e.g., a rotary pyro-gasifier), a methane combustor for external heating, a secondary combustion chamber for tar/syngas combustion, and an exhaust gas treatment unit [18]. The system processes solid waste with a residence time of 30-40 minutes, enabled by an internal spiral transport mechanism.

Analytical Techniques and Product Characterization

Comprehensive analysis of reaction products is essential for understanding governing mechanisms:

- Gas Analysis: Gas chromatography (GC) with thermal conductivity (TCD) and flame ionization (FID) detectors provides quantitative composition data (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, C₂-C₃ hydrocarbons) of the syngas, enabling calculation of lower heating values (LHV) [18].

- Tar Characterization: Tar sampling followed by GC-MS analysis identifies heavy hydrocarbon compounds, which is critical for understanding secondary reaction pathways and optimizing tar reduction strategies [17].

- Char Analysis: Proximate and ultimate analysis of solid residue determines fixed carbon, volatile matter, and ash content, while surface area analyzers (BET) characterize pore structure development during gasification [17].

Advanced experimental approaches combine thermochemical modeling with experimental validation. For instance, vector optimization methodologies can calibrate numerical models against experimental data to estimate unknown feedstock compositions and identify optimal process conditions, reducing the need for extensive experimental trials [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biomass Conversion Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Gasifying Agents | Reactants for gasification; determine syngas composition & heating value | Air (for 4-7 MJ/Nm³ gas), O₂ (for 10-12 MJ/Nm³ gas), Steam (for 15-20 MJ/Nm³ gas) [17] |

| Biomass Reference Materials | Standardized feedstocks for comparative studies | Cellulose, lignin, xylan; characterized by proximate/ultimate analysis [16] |

| Catalytic Materials | Tar cracking, syngas reforming, reaction rate enhancement | Dolomite, Ni-based catalysts, alkali metals (K, Na), char itself [17] |

| Calibration Gas Standards | GC calibration for quantitative syngas analysis | Certified mixtures of H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, C₂H₄, C₂H₆ in N₂ balance |

| Sorbent Materials | In-situ contaminant removal (H₂S, HCl, NH₃) | ZnO, CaO, dolomite for acid gas capture [18] |

Beyond the reagents listed, sophisticated modeling approaches represent crucial analytical "tools" for modern researchers. Thermodynamic equilibrium models (comprising ~60% of studies, with 72.5% using non-stoichiometric approaches) predict maximum achievable yields under ideal conditions. Kinetic models incorporate reaction rates and residence times for more realistic predictions, while computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models simulate complex multiphase flows, heat transfer, and chemical reactions within reactors. Recently, data-driven models using artificial neural networks (ANN) have demonstrated high accuracy in predicting syngas composition from operational parameters [2].

Effective experimental design in this field requires careful consideration of multiple interrelated parameters: feedstock selection (composition, particle size, ash content), gasifying agent type and flow rate, reaction temperature profile, heating rate, pressure, and catalyst presence. The complex interactions between these parameters necessitate systematic experimental designs such as response surface methodology (RSM) to elucidate their effects on reaction mechanisms and product distributions [17].

Biomass gasification and pyrolysis are pivotal thermochemical conversion processes that transform renewable biomass into valuable energy products and chemical feedstocks. These technologies support the transition toward a circular bioeconomy by converting agricultural residues, energy crops, and organic waste into syngas, bio-oil, and biochar. The composition and properties of these products are highly influenced by feedstock characteristics and process parameters, necessitating advanced analytical techniques for precise characterization. This technical guide provides researchers and scientists with comprehensive methodologies for analyzing the complex chemical compositions of gasification and pyrolysis products, enabling optimization of conversion processes and downstream applications.

Analytical Techniques for Product Characterization

Syngas Composition Analysis

Syngas, primarily composed of H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, and N₂, requires precise monitoring for process optimization and quality control. Advanced spectroscopic and mass spectrometric techniques enable real-time quantitative analysis of these multicomponent gas mixtures.

Raman Spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for rapid analysis of syngas composition. The technique utilizes contour fit methodology where experimental Raman spectra of gas mixtures are compared with synthetically calculated spectra for component quantification. This approach allows simultaneous determination of multiple gas components (CO, H₂, CH₄, CO₂, N₂) in syngas mixtures. Research indicates that pressure variations and environmental effects on band contours can introduce measurement errors significantly higher than those caused by signal intensity deviations [19]. The method offers advantages for continuous process monitoring without requiring complex sample preparation.

Process Mass Spectrometry provides an alternative approach for syngas characterization. The Extrel MAX300-RTG quadrupole mass spectrometer, for instance, demonstrates capability for quantitative analysis of syngas components across concentration ranges from 100% down to 10 ppb. This technology enables rapid measurement cycles (under 0.4 seconds per analysis) and automated monitoring of multiple sample points throughout gasification systems. The sensitivity to trace components at ppm levels and ability to analyze complete syngas arrays makes mass spectrometry suitable for replacing complicated multi-instrument analysis systems [20].

Table 1: Analytical Techniques for Syngas Composition Analysis

| Technique | Detection Range | Key Measured Components | Analysis Speed | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy | Major components | CO, H₂, CH₄, CO₂, N₂ | Fast | Contour fit method; affected by pressure changes |

| Process Mass Spectrometry | 100% to 10 ppb | H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, trace contaminants | <0.4 seconds per measurement | ppm-level trace detection; multi-point automation |

Bio-oil Chemical Characterization

Bio-oil produced from biomass pyrolysis represents a highly complex mixture containing hundreds of organic compounds across various chemical classes. Comprehensive characterization requires complementary analytical techniques to overcome the limitations of individual methods.

Chromatographic and Spectroscopic Techniques provide orthogonal information for bio-oil composition analysis. Gas Chromatography (GC) enables separation and quantification of volatile and semi-volatile components, while High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) resolves thousands of compounds based on exact mass measurements. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy identifies functional groups and chemical bonds through characteristic absorption frequencies, providing information about carbonyl, hydroxyl, and aromatic compounds. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy, particularly ¹H and ¹³C NMR, offers quantitative information about carbon distribution and functional groups without requiring component separation [21].

The complexity of bio-oil necessitates this multi-technique approach, as no single method can comprehensively characterize the complete spectrum of components ranging from non-polar hydrocarbons to highly polar oxygenated compounds such as carboxylic acids, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, esters, furfurals, phenolic compounds, sugar-like material, and lignin-derived compounds [21].

Biochar Surface and Structural Analysis

Biochar properties vary significantly based on feedstock and pyrolysis conditions, requiring sophisticated analytical approaches to characterize surface functionality, carbon stability, and structural attributes.

Diffuse Reflection Infrared Fourier Transform Spectroscopy (DRIFTS) enables investigation of biochar surface functional groups. Statistical analysis of DRIFTS spectra through multiple regression models and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reveals relationships between biochar characteristics and functional group presence. Research demonstrates that pyrolysis temperature represents the dominant parameter affecting functional groups, followed by H/C ratio, specific surface area, and ash content. Regression models can explain 60-90% of data variance for specific infrared spectral peaks. Studies of 92 different biochars reveal that functional groups in biochars from lignin-rich feedstock exhibit higher temperature resistance, with pyrolysis at 300°C and 450°C producing similar infrared spectra, while temperatures of 600°C lead to partial and 750°C to nearly complete loss of surface functional groups [22].

FTIR-Microscopy with Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy provides insights into carbon stabilization mechanisms in biochar-amended soils. This combined approach reveals the spatial reorganization of carbon within soil particles following biochar application. Research shows accumulation of aromatic-C in discrete spots within microaggregates and its co-localization with clay minerals. Biochar application consistently reduces the co-localization of aromatic-C with polysaccharides-C, suggesting reduced carbon metabolism as a crucial mechanism for carbon stabilization in biochar-amended soils. Fluorescence analysis of dissolved organic matter further indicates that biochar application increases a humic-like fluorescent component associated with biochar-C in solution [23].

Table 2: Analytical Techniques for Bio-oil and Biochar Characterization

| Material | Primary Techniques | Key Information Obtained | Statistical Methods | Technical Insights |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-oil | GC, HRMS, FTIR, NMR | Molecular speciation, functional groups, compound classes | - | Complementary techniques needed for comprehensive characterization |

| Biochar | DRIFTS, FTIR-Microscopy, CLSM | Surface functional groups, carbon distribution, spatial organization | Multiple regression, PCA | Pyrolysis temperature > H/C ratio > surface area > ash content |

Experimental Methodologies

Raman Spectroscopy for Syngas Analysis Protocol

Sample Introduction System: Utilize a gas-tight sampling cell with controlled temperature and pressure capabilities. Implement pressure regulation to maintain consistent measurement conditions, as pressure variations significantly impact measurement accuracy.

Instrument Calibration: Establish reference spectra for pure components (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, N₂) under identical instrument configurations. Develop a synthetic spectrum library covering expected concentration ranges and mixture ratios.

Spectral Acquisition: Employ laser excitation sources appropriate for Raman scattering cross-sections of syngas components. Optimize exposure times to balance signal-to-noise ratio with measurement frequency requirements.

Data Analysis: Apply contour fit algorithms to compare experimental spectra with synthetic references. Quantify components based on characteristic peak intensities and shapes after background subtraction and normalization.

Quality Control: Implement periodic validation with certified standard gas mixtures. Monitor system performance through control charts for key component measurements.

Biochar Functional Group Analysis Protocol

Sample Preparation: Grind biochar samples to consistent particle size (typically <100 μm) to ensure representative sampling and spectral reproducibility. Dry samples at 105°C to remove moisture interference.

DRIFTS Measurement: Acquire infrared spectra in diffuse reflection mode across 4000-400 cm⁻¹ range. Co-add multiple scans to improve signal-to-noise ratio. Use potassium bromide (KBr) as background reference material.

Spectral Processing: Apply Kubelka-Munk transformation to reflectance data. Perform baseline correction and vector normalization to enable quantitative comparisons between samples.

Multivariate Analysis: Execute Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify dominant factors influencing spectral variance. Develop multiple linear regression models correlating spectral features with biochar properties (pyrolysis temperature, elemental composition, surface area).

Validation: Employ cross-validation techniques to assess model robustness. Verify predictions against independent characterization data (elemental analysis, surface area measurements).

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Biomass Conversion Product Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Application | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Standard Gas Mixtures | Syngas analysis | Calibration and validation of analytical instruments |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | DRIFTS analysis | IR-transparent matrix for biochar analysis |

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆) | NMR spectroscopy | Solvent for bio-oil analysis without proton interference |

| Derivatization Reagents | GC analysis of bio-oil | Enhance volatility and detectability of polar compounds |

| Reference Biochars | Method validation | Certified materials for quality control in biochar analysis |

| Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges | Bio-oil fractionation | Separate compound classes for simplified analysis |

Analytical Workflow Visualization

Biomass Product Analysis Workflow

Biochar Functional Group Analysis Protocol

Advanced analytical techniques are indispensable for elucidating the complex compositions of syngas, bio-oil, and biochar derived from biomass gasification and pyrolysis. Raman spectroscopy and process mass spectrometry enable precise, real-time monitoring of syngas components, essential for process optimization. Bio-oil characterization requires complementary techniques including GC, FTIR, NMR, and HRMS to resolve its complex mixture of oxygenated compounds. Biochar analysis benefits from DRIFTS with multivariate statistics to correlate surface functionality with production parameters and application performance. The integrated analytical workflows presented in this guide provide researchers with robust methodologies for comprehensive product characterization, supporting advancements in biomass conversion technologies and sustainable biorefinery development.

Reactor Technologies and Process Design for Efficient Biomass Conversion

Biomass gasification, a thermochemical conversion process, has emerged as a pivotal technology in the global transition to renewable energy and decarbonization. It provides a pathway for converting diverse biomass feedstocks into syngas—a mixture primarily of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, and methane—which can be utilized for power generation, chemical synthesis, and the production of liquid fuels [2] [7]. Within the broader context of biomass gasification and pyrolysis research, the selection of gasifier technology fundamentally influences process efficiency, syngas composition, economic viability, and environmental impact. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis and comparison of the three principal gasifier types: Fixed Bed, Fluidized Bed, and Entrained Flow [2] [24]. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this guide synthesizes current operational data, experimental methodologies, and technical criteria to support informed decision-making in research and development projects.

Core Gasification Technologies

The gasification process involves several sequential stages—drying, pyrolysis, oxidation, and reduction—that occur within a reactor vessel. The design of this vessel, dictating the flow dynamics of the solid feedstock and gaseous agents, is the primary differentiator between gasifier types [7].

- Fixed Bed Gasifiers: Characterized by a relatively stationary bed of biomass, these gasifiers are traditionally classified into updraft, downdraft, and cross-draft configurations based on the flow direction of the gasifying agent [24]. The reaction rate is slower, and the temperature distribution can be uneven, but their simple structure allows for robust operation [24].

- Fluidized Bed Gasifiers: These suspend feedstock particles in an oxygen-rich gas, causing the bed to behave like a fluid. This ensures excellent mixing, uniform temperature distribution, and high heat transfer rates [25]. They are particularly suited for reactive, low-rank fuels like biomass [25].

- Entrained Flow Gasifiers: Operating at very high temperatures and velocities, these gasifiers process finely ground feedstock that is entrained with the gas flow. They are known for high carbon conversion, very low tar production, and a compact design, but require significant feedstock pretreatment [26] [27].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow and logical decision points for selecting and operating a biomass gasification system, from feedstock to final application.

Technical Comparison and Quantitative Data

A critical evaluation of technical parameters is essential for selecting the appropriate gasifier technology for a specific research or commercial application. The following tables summarize key performance indicators, operational characteristics, and economic factors.

Table 1: Performance and Operational Parameters of Gasifier Types

| Parameter | Fixed Bed | Fluidized Bed | Entrained Flow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Scale | Small to Medium [24] | Medium to Large [24] | Large (≥100 MWth) [26] |

| Operating Temperature | ~1000 °C [24] | Moderate (Below ash fusion point) [25] | High (>1200 °C) [26] [27] |

| Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE) | ~66-81% (for fluidized bed, as reference) [26] | 66% - 81% [26] | 77% - 82% [26] |

| Carbon Conversion | 90% - 99% [24] | ~90% - 95% [24] [25] | Very High (>99%) [26] [27] |

| Syngas Tar Content | High (Updraft: up to 100 g/Nm³; Downdraft: ~1 g/Nm³) [10] | Lower than fixed bed [24] | Very low [26] [27] |

| Feedstock Flexibility | Low; requires uniform shape/size [24] | High; accepts diverse materials [24] [25] | Low; requires fine, pulverized feed [26] |

| Gas & Solid Residence Time | Long solids, short gas [24] | Short for both [24] | Very short for both |

Table 2: Economic and Application-Based Analysis

| Criteria | Fixed Bed | Fluidized Bed | Entrained Flow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Cost | Low (simple structure) [24] | High (complex system) [24] | Very High (high-pressure design, feed systems) [26] |

| Operational Flexibility | High (20-110% of design load) [24] | Moderate (50-120% of design load) [24] | Low, best at base load |

| Key Applications | Small-scale power, heat [24] [10] | Power, BioSNG, chemicals [26] [7] | Large-scale liquid fuels (e.g., SAF), chemicals [26] [27] |

| Environmental Impact | Low fly ash in gas [24] | High fly ash in gas, requires cleaning [24] | Slagging ash, potentially easier disposal |

Experimental Protocols for Gasification Research

For researchers investigating gasifier performance, standardized experimental protocols are crucial for generating comparable and reproducible data. Below are detailed methodologies for key areas of gasification research.

Protocol for Assessing Feedstock Suitability and Pretreatment

Objective: To evaluate the gasification reactivity of a biomass feedstock and determine the necessary pretreatment steps. Background: Biomass variability significantly impacts syngas yield and quality. Pretreatment like torrefaction can improve grindability and energy density for entrained flow systems [26]. Materials:

- Biomass sample (e.g., wood chips, agricultural residue)

- Jaw crusher, hammer mill, and sieve shaker

- Drying oven

- Torrefaction reactor (for advanced pretreatment)

- Calorimeter (for LHV/HHV analysis)

- Proximate and ultimate analyzers

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Reduce the biomass sample to a particle size of <2 mm for analysis using a jaw crusher and hammer mill. Use a sieve shaker to ensure uniformity.

- Proximate & Ultimate Analysis: Determine the moisture, volatile matter, fixed carbon, and ash content (proximate) as well as the carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen content (ultimate) of the prepared sample.

- Drying: Dry a separate, larger batch of feedstock in an oven at 105°C until constant weight is achieved to reduce moisture to 10-20% [7].

- Size Reduction for Specific Gasifiers:

- Fixed Bed: Process to a uniform, coarse size (e.g., 10-50 mm) [24].

- Fluidized Bed: Process to a smaller particle size (<6 mm) [25].

- Entrained Flow: Pulverize the dried feedstock to <1 mm. Optionally, conduct torrefaction (heating to 200-300°C in an inert atmosphere) to improve grindability and hydrophobicity [26].

- Analysis of Treated Feedstock: Re-analyze the calorific value and chemical composition of the pretreated feedstock to quantify the impact of pretreatment.

Protocol for Determining Cold Gas Efficiency and Syngas Composition

Objective: To measure the performance of a gasifier by calculating its Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE) and analyzing the composition of the produced syngas. Background: CGE is a key performance indicator, defined as the ratio of the chemical energy in the syngas to the chemical energy in the input fuel [26]. Materials:

- Bench-scale or pilot-scale gasifier unit

- Gasifying agent supply (air, O₂, steam)

- Syngas sampling and conditioning system

- Online Gas Chromatograph (GC) or mass spectrometer

- Gas flow meters

- Data acquisition system

Procedure:

- System Calibration: Calibrate all sensors, including temperature, pressure, and gas flow meters. Calibrate the GC using standard gas mixtures.

- Reactor Startup: Heat the gasifier to the target operating temperature under an inert gas flow. For fluidized beds, this requires pre-heating the bed material [25].

- Steady-State Operation: Feed the pretreated biomass into the reactor at a constant, predetermined rate. Introduce the gasifying agent (e.g., air, oxygen, steam) at the desired flow rate. Maintain operational parameters (temperature, pressure) until steady state is achieved (typically indicated by stable temperature and gas composition readings for >30 minutes).

- Data Collection: Once at steady state, record the mass flow rate of the biomass feedstock and the gasifying agent. Simultaneously, collect syngas samples for immediate analysis via GC. Record the volumetric flow rate and temperature of the product syngas.

- Calculation:

- Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE): Calculate using the formula:

η_CGE = (ṁ_syngas × LHV_syngas) / (ṁ_biomass × LHV_biomass) × 100%[26] whereṁis mass flow rate andLHVis the lower heating value. - Composition: Report the molar or volumetric fractions of H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄, and N₂ from the GC data.

- Cold Gas Efficiency (CGE): Calculate using the formula:

Protocol for Tar Measurement and Analysis

Objective: To quantify and characterize the tar content in the raw syngas produced by a gasifier. Background: Tar is a complex mixture of condensable hydrocarbons that can clog and damage downstream equipment. Its concentration is highly dependent on the gasifier type and operating conditions [10]. Materials:

- Tar sampling train (e.g., based on CEN/TS 15439: a series of impinger bottles kept in an isothermal bath)

- Solvent (e.g., acetone, isopropanol)

- Gas meter

- Vacuum pump

- Rotary evaporator

- Analytical balance

- GC-MS (for tar speciation)

Procedure:

- Sampling Train Setup: Cool the impinger bottles in an ice bath. Fill several bottles with a known volume of solvent. Connect the sampling train to the syngas line, ensuring a leak-free setup.

- Isokinetic Sampling: Draw a known volume of syngas through the train at a controlled, isokinetic rate using a vacuum pump and gas meter. The tars and other condensables will be trapped in the solvent.

- Sample Recovery: After sampling, carefully recover the solvent from all impingers and rinse them thoroughly. Combine all washes into a single container.

- Gravimetric Analysis: Evaporate the solvent from an aliquot of the sample using a rotary evaporator. Dry the residual tar to a constant weight in a desiccator. Weigh the mass of the tar.

- Calculation & Speciation:

- Tar Concentration: Calculate as

Tar (g/Nm³) = (Mass of Tar / Sampled Gas Volume)[10]. - Speciation (Optional): Dissolve the residual tar in a suitable solvent and analyze it via GC-MS to identify the specific tar compounds present.

- Tar Concentration: Calculate as

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Gasification Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Feedstocks (Wood, agricultural residues, MSW) | Primary reactant for syngas production. Variability in composition (H/C, O/C ratios) directly influences syngas yield and quality [7]. | Used across all gasifier types; pretreatment requirements vary significantly [26] [24]. |

| Gasifying Agents (Air, O₂, Steam, CO₂) | Medium for partial oxidation and gasification reactions. The choice of agent defines the oxidant-to-fuel ratio, process thermodynamics, and final syngas composition (e.g., H₂/CO ratio) [2] [7]. | Air is common for simple systems; O₂/steam blends are used for high-quality, N₂-free syngas in synthesis applications [26]. |

| Bed Material (Silica sand, Olivine, Dolomite) | In fluidized bed gasifiers, provides a heat transfer medium and a stable fluidized bed. Certain materials (e.g., Olivine, Dolomite) can act as in-situ catalysts for tar cracking [25]. | Exclusive to fluidized bed gasifiers. Selection is critical for achieving desired tar reduction and operational stability. |

| Catalysts (Ni-based, Zeolites) | Used in downstream catalytic reactors (e.g., reformers) to convert tars and light hydrocarbons into additional syngas (H₂ and CO), thereby improving gas quality and efficiency [26]. | Essential for advanced gas cleaning trains, particularly when targeting synthesis applications like BioSNG or Fischer-Tropsch fuels. |

| Solvents (Acetone, Isopropanol) | Used in tar sampling trains to absorb and dissolve tars from the hot syngas for subsequent gravimetric and chemical analysis [10]. | Critical for quantitative tar measurement protocols in experimental setups. |

The comparative analysis presented in this whitepaper underscores that there is no universally superior gasifier type. The optimal selection is a complex function of project-specific constraints and objectives, including scale, feedstock characteristics, desired syngas application, and economic considerations.

- Fixed-bed gasifiers offer simplicity and reliability for small-to-medium-scale applications but are constrained by feedstock requirements and syngas quality, particularly tar content [24] [10].

- Fluidized-bed gasifiers provide an excellent balance of feedstock flexibility, good efficiency, and reasonable syngas quality, making them a prominent choice for medium-to-large-scale power and BioSNG production [26] [24] [7].

- Entrained-flow gasifiers, while capital-intensive and requiring extensive feedstock pretreatment, deliver the highest quality, tar-free syngas and are the benchmark for large-scale biomass-to-liquid fuel projects, such as Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) production [26] [27].

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating advanced modeling techniques like machine learning and computational fluid dynamics to optimize gasifier design and operation [2], developing more robust and cheaper tar-cracking catalysts, and creating innovative gasification systems such as hybrid solar-biomass reactors to improve sustainability and efficiency. For scientists and engineers, the choice of gasifier remains a foundational decision that dictates the trajectory of research and development in the pursuit of decarbonizing the energy and chemical sectors.

Within the broader research on biomass gasification and pyrolysis, pyrolysis stands out as a versatile thermochemical conversion process for transforming diverse biomass feedstocks into valuable biofuels, namely bio-oil, biochar, and syngas [28] [29]. The strategic selection and optimization of reactor configurations are paramount, as they directly influence the complex interplay of heat and mass transfer, reaction kinetics, and ultimately, the yield and quality of the target products [28]. This guide provides an in-depth technical analysis of pyrolysis reactor technologies, focusing on the engineering principles and operational parameters that enable researchers to direct product distribution towards maximizing the yield of bio-oil, gas, or char, thereby supporting advanced biofuel production and sustainable resource recovery.

Pyrolysis Process Fundamentals and Product Spectrum

Pyrolysis involves the thermal decomposition of biomass in an inert atmosphere at temperatures typically ranging from 300°C to 900°C [30] [31]. The process leads to the production of three primary products: a solid (biochar), a liquid (bio-oil), and a gaseous phase (syngas) [28]. The distribution of these products is predominantly governed by the process conditions, particularly temperature, heating rate, and vapor residence time [29].

Bio-oil is a complex emulsion of oxygenated hydrocarbons, water, and various other compounds. It can be upgraded into transportation fuels or used as a source of chemicals [30] [29]. Biochar is a carbon-rich solid with applications as a soil amendment, for carbon sequestration, and as an industrial adsorbent [2] [32]. Its quality and properties are highly dependent on the pyrolysis temperature [29]. Syngas is a mixture of non-condensable gases, including hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO), carbon dioxide (CO2), and methane (CH4), which can be utilized for heat and power generation or further synthesized into fuels like methane and ammonia [2] [33].

Table 1: Influence of Key Pyrolysis Parameters on Product Yields

| Parameter | Bio-oil Yield | Biochar Yield | Syngas Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| Increasing Temperature | Increases to an optimum (typically 450-550°C), then decreases [29] [32] | Consistently decreases [29] | Consistently increases [29] |

| Faster Heating Rate | Favors higher yield [28] [29] | Reduces yield [28] | Favors higher yield [28] |

| Shorter Vapor Residence Time | Favors higher yield by minimizing secondary cracking [28] | Minimal direct effect | Reduces yield by limiting gas-phase reactions [28] |

Reactor Configurations for Targeted Product Yields

The design of the pyrolysis reactor is the critical engineering element that controls the core process parameters. Different reactor types are engineered to create specific thermal environments that favor the formation of a desired product.

Fluidized Bed Reactors

Fluidized bed reactors, including bubbling and circulating fluidized beds, are highly effective for high-yield bio-oil production due to excellent heat transfer and rapid heating rates [28].

- Operating Principle: A bed of inert material (e.g., sand) is fluidized by a preheated gas, creating a violently mixed, isothermal environment. Biomass feedstock, finely ground and rapidly injected, undergoes very fast pyrolysis.

- Maximizing Bio-oil Yield: The high heating rates (100-1000 °C/s) and short vapor residence times (0.5-2 s) are key to maximizing liquid yield by rapidly quenching the primary pyrolysis vapors before they crack into gaseous products [28]. These reactors are well-suited for catalytic pyrolysis, where the bed material can be replaced with a catalyst (e.g., zeolites) to improve bio-oil quality and selectivity towards specific fuels like hydrogen [31].

- Typical Yields: Bio-oil yields can reach 60-75 wt% under optimal conditions [28].

Fixed Bed Reactors

Fixed bed reactors, also known as packed bed reactors, are a simpler technology often employed for slow pyrolysis, making them ideal for maximizing biochar production [28] [29].

- Operating Principle: Biomass is packed into a static bed, and heat is supplied externally. The design promotes longer solid and vapor residence times.

- Maximizing Biochar Yield: The slow heating rates (0.1-1 °C/s) and long residence times (minutes to hours) allow for extensive secondary char-forming reactions through repolymerization of intermediate vapors [29]. A study on the slow pyrolysis of Prosopis juliflora demonstrated that biochar yield decreases with increasing temperature (from 300°C to 600°C), but its fixed carbon content and heating value improve [29].

- Typical Yields: Slow pyrolysis in fixed beds can achieve biochar yields of 30-35 wt% [34] [29].

Auger (Screw) Reactors

Auger reactors provide a continuous process that can be tuned for various product slates, often offering a balance between bio-oil and biochar production [28].

- Operating Principle: Biomass is transported through a heated tube by a screw, with heat transferred through the reactor wall. The residence time is controlled by the screw speed.

- Maximizing Versatility: This configuration can be operated for intermediate pyrolysis, which offers flexibility in product distribution. It is particularly suitable for feedstocks with a tendency to slag, such as sewage sludge, and for co-pyrolysis applications [28]. The use of an internally heated screw, where a heat carrier like steel balls is mixed with the biomass, can significantly improve heat transfer efficiency.

Entrained Flow and Spouted Bed Reactors

These reactors are designed for very high reaction rates and are suitable for maximizing gas yield or for fast pyrolysis of challenging feedstocks.

- Entrained Flow Reactors: Biomass particles are entrained in a hot gas stream and undergo rapid pyrolysis during their short transit. This design is characterized by very short residence times (<1 s) and is effective for maximizing bio-oil yield from fine particles [2] [28].

- Conical Spouted Bed Reactors: Particularly effective for processing irregular, sticky, or coarse particles that are difficult to fluidize. The unique gas-spouting pattern ensures excellent particle mixing and heat transfer, minimizing char agglomeration and making them suitable for the catalytic pyrolysis of plastic wastes for hydrogen production [31].

Advanced and Hybrid Reactor Systems

- Microwave Reactors: Utilize microwave radiation for volumetric heating, which can lead to faster and more selective heating compared to conventional methods, potentially improving bio-oil quality and process efficiency [29].

- Plasma Reactors: Use thermal plasma torches to achieve extremely high temperatures (>>1000°C), designed primarily for complete gasification of feedstock into syngas with high hydrogen and carbon monoxide content, and for waste treatment [2] [29].

Table 2: Comparative Summary of Pyrolysis Reactors for Yield Maximization

| Reactor Type | Target Product | Heating Rate | Residence Time | Key Advantages | Technological Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluidized Bed | Bio-oil | Very High | Short (0.5-2 s) | Excellent heat transfer, high bio-oil yield, continuous operation | High (Commercial) [28] |

| Fixed Bed | Biochar | Slow | Long (10-100 min) | Simple design, high char yield, easy operation | High (Pilot/Commercial) [28] [29] |

| Auger / Screw | Bio-oil / Biochar | Moderate | Medium | Handles heterogeneous feedstocks, good for co-pyrolysis, continuous | Medium to High [28] |

| Entrained Flow | Bio-oil | Very High | Very Short (<1 s) | Simple design, rapid heating | Medium [2] |

| Microwave | Bio-oil / Biochar | Very High | Variable | Selective heating, rapid startup, improved oil quality | Low to Medium (R&D) [29] |

| Plasma | Syngas | Extreme | Short | Very high temperatures, high syngas purity, handles hazardous waste | Medium (Niche applications) [2] |

Experimental Protocols for Reactor Performance Evaluation

Protocol: Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) for Kinetic Studies

Thermogravimetric analysis is a fundamental tool for understanding biomass decomposition kinetics and designing larger-scale reactors [35].

- Sample Preparation: Dry and mill the biomass feedstock to a fine particle size (< 200 µm) to minimize heat and mass transfer limitations [35].

- Experimental Setup: Load a small sample (5-20 mg) into a TGA crucible. Purge the system with an inert gas (N₂) at a constant flow rate (e.g., 100 mL/min) to maintain an oxygen-free environment.

- Temperature Program: Subject the sample to a predefined temperature program. This can be:

- Dynamic/Non-Isothermal: Heat at a constant rate (e.g., 10, 20, 30 K/min) from ambient to a final temperature (e.g., 900°C).

- Isothermal: Rapidly heat to a set of target temperatures (e.g., 400, 500, 600°C) and hold for a duration.

- Data Analysis: Record mass loss (TG) and mass loss rate (DTG) as a function of time and temperature. Model the data using kinetic models like the Random Pore Model (RPM) to determine apparent activation energy and pre-exponential factors, which are crucial for reactor scale-up [35].

Protocol: Catalytic Pyrolysis for Enhanced Bio-Oil or Hydrogen Yield

This protocol outlines the steps for integrating a catalyst into the pyrolysis process to improve fuel quality and selectivity [31].

- Catalyst Selection and Preparation: Choose a catalyst based on the target product (e.g., Zeolites (ZSM-5) for deoxygenation of bio-oil; Ni-based catalysts for hydrogen-rich gas production). The catalyst can be used in-situ (mixed with biomass) or ex-situ (in a secondary reactor bed) [31].

- Reactor Configuration: Set up a two-stage reactor system. The first stage is a typical pyrolysis reactor (e.g., fluidized bed). The second stage is a fixed-bed catalytic reactor placed immediately downstream to treat the hot vapors/gases.

- Experimental Procedure:

- Pre-heat both reactors to the desired temperatures (e.g., Pyrolysis: 500°C; Catalysis: 600°C).

- Feed biomass into the first reactor at a controlled rate.

- Direct the produced vapors and gases through the catalytic bed.

- Maintain an inert atmosphere throughout the system.

- Product Collection and Analysis: Condense the vapors after the catalytic reactor to collect liquid product. Use an online gas analyzer or gas chromatography (GC) to quantify the composition and yield of non-condensable gases (H₂, CO, CO₂, CH₄) [35] [31]. Analyze the bio-oil for oxygen content and chemical composition using GC-MS.

Protocol: Co-Pyrolysis for Synergistic Yield Enhancement

Co-pyrolysis of two or more feedstocks can improve overall conversion and product quality through synergistic interactions [32].

- Feedstock Blending: Select and characterize the primary and secondary feedstocks (e.g., Sewage Sludge (SS) and Sugarcane Residue (SR)). Blend them at different mass ratios (e.g., 90:10, 70:30, 50:50 SS:SR) [32].

- Reactor Operation: Use a fixed-bed or fluidized bed reactor. Conduct pyrolysis experiments at a set temperature (e.g., 500°C) for each blend ratio.