Biomass Energy: A Foundational Guide to Sources, Conversion, and Integration in Modern Renewable Portfolios

This article provides a comprehensive overview of biomass energy, detailing its foundational principles as a renewable resource derived from organic materials.

Biomass Energy: A Foundational Guide to Sources, Conversion, and Integration in Modern Renewable Portfolios

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of biomass energy, detailing its foundational principles as a renewable resource derived from organic materials. It explores the diverse methodologies for converting biomass into usable energy, including thermal, chemical, and biological processes. The content addresses key challenges in optimizing biomass supply chains and system integration, supported by current data on global capacity and growth. Finally, it presents a comparative analysis of biomass against other renewables, validating its unique role in providing dispatchable power and sustainable fuels, with specific implications for enhancing sustainability in the research and development sector.

What is Biomass Energy? Unpacking the Renewable Resource and Its Global Potential

Biomass energy, derived from living or recently living organisms, represents one of humanity's oldest and most versatile energy sources. Since the earliest hominids first made wood fires for cooking or keeping warm, people have utilized biomass energy—energy from living things [1]. In the contemporary energy landscape, biomass is categorized as a semi-renewable energy resource that comes from plants and animals, requiring careful management to ensure it is not used faster than it can be replenished [2].

Biomass is organic material that contains stored chemical energy from the sun, which plants produce through photosynthesis [1] [2]. This process allows plants to absorb the sun's energy and convert carbon dioxide and water into nutrients (carbohydrates) [1]. The energy from these organisms can be transformed into usable energy through direct and indirect means, including burning biomass to create heat or electricity, or processing it into biofuel [1]. Within the context of a renewable energy portfolio, biomass contributes to diversifying energy resources, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and mitigating climate change [3].

Table: Global Bioenergy Statistics (Commercial/Modern Bioenergy)

| Metric | World | United States |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Energy Mix | 2% | 5% |

| Electricity Generation | 2% | 1% |

| Transportation Energy | 4% | 7% |

| Heat Generation | 8% | 8% |

Source: [2]

Biomass Feedstocks and Classification

Biomass feedstocks represent the raw materials used to produce bioenergy and can be categorized in several ways based on their origin, composition, and use. The most common biomass materials used for energy are plants, wood, and waste, though the specific feedstocks utilized have evolved significantly [1].

Traditional vs. Commercial Biomass

A fundamental distinction exists between traditional and commercial biomass. Traditional biomass includes wood, peat, or animal waste gathered and burned by people for cooking and heating. While easy to store, traditional biomass has a low energy density and generates severe indoor air pollution with significant human health effects (responsible for almost 3 million deaths in 2023) [2]. Globally, over 2 billion people (approximately 25% of the world's population) still rely on traditional biomass, though energy statistics generally exclude it because it is not commercially bought and sold, making it difficult to track [2]. Traditional biomass provides approximately 7% of primary energy consumed worldwide [2].

Commercial biomass (or modern bioenergy) is bought and sold and provides heat and electricity in homes, businesses, and industry, as well as liquid fuels for transportation [2]. Commercial biomass accounts for approximately 6% of total end-use energy consumed worldwide and can be further divided into three main categories [2]:

- Solid Biomass: Woody material, crops, municipal solid waste (MSW), and animal and agricultural waste that can be directly burned to produce heat or to generate electricity [2].

- Liquid Biofuels: Primarily ethanol, biodiesel, and renewable diesel produced from processing plant matter or waste such as cooking oil into substitutes for or additives to traditional vehicle fuels [2].

- Biogas: Collected from decomposing plants, animal manure, human sewage, and municipal solid waste, which can be combusted for direct heat use or electricity generation [2].

Table: Commercial Biomass Supply Breakdown (Global)

| Feedstock Type | Percentage of Global Supply |

|---|---|

| Solid Biomass | 86% |

| Liquid Biofuels | 7% |

| Municipal Waste | 3% |

| Biogas | 2% |

| Industrial Waste | 2% |

Source: [2]

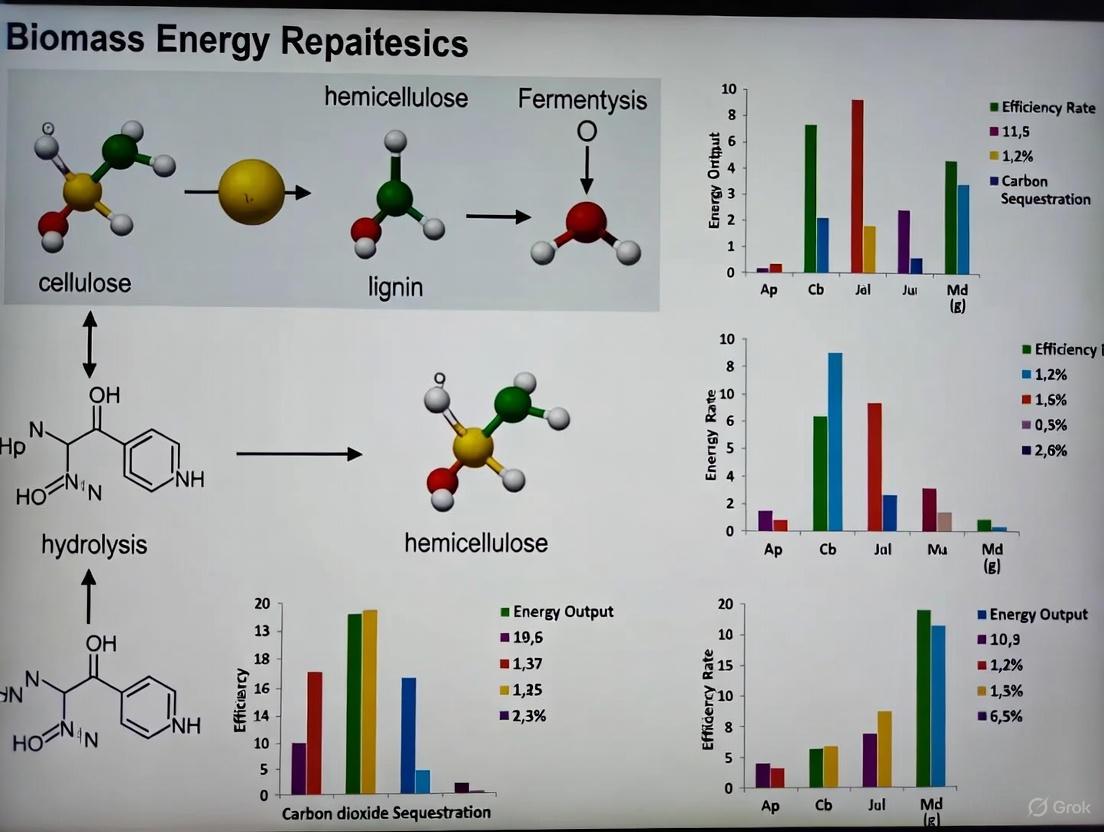

Figure 1: Biomass Feedstock Classification

The specific sources of biomass feedstocks are diverse and include:

- Forest Wood: The nation's largest biomass energy resource, including natural woodlands, managed forests, and fuelwood plantations [4] [2].

- Agricultural Residues: Such as corn stover (the stalks, leaves, and husks of the plant) and wheat straw [4].

- Energy Crops: Dedicated energy crops, such as fast-growing trees and grasses, and algae, which can grow on land that will not support intensive food crops [4].

- Municipal Solid Waste (MSW): The organic component of municipal and industrial wastes [4] [1].

- Processing Byproducts: Sawdust and chips from sawmills, black liquor from paper production, and other industrial waste streams [1] [5].

- Landfill Gases: Fumes from landfills that contain methane, the main component in natural gas [4].

Algae represents a particularly unique feedstock with enormous potential as a source of biomass energy. Algae, whose most familiar form is seaweed, produces energy through photosynthesis at a much quicker rate than any other biofuel feedstock—up to 30 times faster than food crops [1]. It can be grown in ocean water, so it does not deplete freshwater resources, and does not require soil, therefore not reducing arable land that could potentially grow food crops [1].

Biomass Conversion Technologies

The transformation of raw biomass feedstocks into usable energy occurs through multiple technological pathways, each with distinct processes and outputs. These technologies can be broadly categorized into thermal conversion, chemical/biological conversion, and gasification.

Thermal Conversion Processes

Thermal conversion involves heating the biomass feedstock to burn, dehydrate, or stabilize it [1]. The most familiar biomass feedstocks for thermal conversion are raw materials such as municipal solid waste (MSW) and scraps from paper or lumber mills [1]. Before biomass can be burned, it must typically be dried through a chemical process called torrefaction [1].

Table: Thermal Conversion Methods

| Method | Temperature Range | Process Description | Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Torrefaction | 200°-320°C (390°-610°F) | Biomass dried until it loses ability to absorb moisture | Dry, blackened material compressed into briquettes |

| Direct Firing | Varies | Direct combustion of biomass to produce steam | Steam powers turbines for electricity |

| Co-firing | Varies | Biomass burned with fossil fuel (typically coal) | Reduces coal demand and associated emissions |

| Pyrolysis | 200°-300°C (390°-570°F) | Heating without oxygen to prevent combustion | Pyrolysis oil, syngas, biochar |

Source: [1]

Direct Firing and Co-firing: Most biomass briquettes are burned directly, with the steam produced during the firing process powering a turbine that turns a generator and produces electricity [1]. Biomass can also be co-fired, or burned with a fossil fuel, which is most commonly done in coal plants [1]. Co-firing eliminates the need for new factories for processing biomass and eases the demand for coal, reducing the amount of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases released by burning fossil fuels [1].

Pyrolysis: This related method of heating biomass occurs without the presence of oxygen, which keeps it from combusting and causes the biomass to be chemically altered [1]. Pyrolysis produces a dark liquid called pyrolysis oil (sometimes called bio-oil or biocrude), a synthetic gas called syngas, and a solid residue called biochar [1]. All of these components can be used for energy: pyrolysis oil can be combusted to generate electricity and is also used as a component in other fuels and plastics; syngas can be converted into fuel such as synthetic natural gas or methane; and biochar is particularly useful in agriculture as it enriches soil and prevents it from leaching pesticides and other nutrients into runoff [1].

Gasification and Anaerobic Decomposition

Gasification: Biomass can be directly converted to energy through gasification, which involves heating a biomass feedstock (usually MSW) to more than 700°C (1,300°F) with a controlled amount of oxygen [1]. This process causes the molecules to break down and produce syngas (a combination of hydrogen and carbon monoxide) and slag [1]. The clean syngas can be combusted for heat or electricity, or processed into transportation biofuels, chemicals, and fertilizers, while slag can be used to make shingles, cement, or asphalt [1]. Industrial gasification plants are being built worldwide, with Asia and Australia currently constructing and operating the most plants [1].

Anaerobic Decomposition: This process occurs when microorganisms, usually bacteria, break down material in the absence of oxygen [1]. Anaerobic decomposition is an important process in landfills, where biomass is crushed and compressed, creating an anaerobic (or oxygen-poor) environment where biomass decays and produces methane, which is a valuable energy source [1]. This process can also be implemented on ranches and livestock farms, where manure and other animal waste can be converted to sustainably meet the energy needs of the farm [1].

Figure 2: Biomass Conversion Pathways

Biofuel Production

Biomass is the only renewable energy source that can be converted into liquid biofuels such as ethanol and biodiesel [1]. Biofuel is used to power vehicles and is being produced by gasification in countries such as Sweden, Austria, and the United States [1].

- Ethanol: Made by fermenting biomass that is high in carbohydrates, such as sugarcane, wheat, or corn [1]. About 1,515 liters (400 gallons) of ethanol is produced by an acre of corn, but this requires significant acreage that then becomes unavailable for growing crops for food or other uses [1].

- Biodiesel: Made from combining ethanol with animal fat, recycled cooking fat, or vegetable oil [1]. While biofuels do not operate as efficiently as gasoline, they can be blended with gasoline to efficiently power vehicles and machinery and do not release the emissions associated with fossil fuels [1].

Biomass in the Renewable Energy Portfolio

The integration of biomass into broader renewable energy portfolios represents a critical strategy for diversifying energy resources and achieving sustainability goals. A renewable energy portfolio is a strategic collection of investments in renewable energy sources, technologies, and projects that is essential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating climate change [3].

Portfolio Diversification Benefits

Biomass contributes unique attributes to renewable energy portfolios that complement other renewable sources:

- Dispatchability: Unlike intermittent sources like solar and wind, biomass power can be dispatched when needed, providing grid stability and reliability [3].

- Storage Potential: Solid biomass and liquid biofuels are easily stored, allowing energy to be available on demand without the immediate need for advanced storage technologies [2].

- Baseload Capacity: Biomass can provide continuous, reliable power similar to conventional thermal power plants [4].

- Waste Utilization: Biomass energy can tap waste streams as fuel (e.g., landfill, forestry industry, sewage), converting disposal problems into energy solutions [2].

The U.S. power system is currently undergoing a significant transition, with nearly 500 gigawatts (GW), or about half of the existing thermal generator fleet likely to retire by 2030 [6]. This creates a substantial capacity gap that biomass can help address as part of diversified clean energy portfolios [6].

Economic Considerations in Portfolio Optimization

Recent research has developed sophisticated approaches to optimizing renewable energy project portfolios (REPP). One study proposed a multi-objective mathematical model for identifying the optimal REPP, aiming to maximize net present value while minimizing investment risk while incorporating project lifetime and workforce employment considerations [7]. To optimize the objective functions of this mathematical model, researchers introduced a hybrid meta-heuristic algorithm combining Artificial Immune System (AIS) and Artificial Fish Swarm (AFS) algorithms [7].

Analysis comparing proposed natural gas-fired power plants with optimized, region-specific clean portfolios of renewable energy and distributed energy resources (including biomass) found that in three of four cases, an optimized clean energy portfolio would cost 8-60% less than the announced power plant [6]. Only in one case was the net cost of the optimized clean energy portfolio slightly (~6 percent) greater than the proposed power plant [6].

Government research and development decisions in the energy space are especially difficult due to numerous risks and uncertainties, and due to the complexity of energy's interactions with the broad economy [8]. The Stochastic Energy Deployment System (SEDS) was developed to support and improve public energy R&D decision-making by drawing from expert-elicited probability distributions for R&D-driven improvements in technology cost and performance and using Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate the likelihood of outcomes within a system dynamics energy-economy model [8].

Table: Biomass Energy Utilization by Country

| Application | Leading Countries | Penetration Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | Denmark, Finland | 20%, 14% of country's electricity consumption |

| Transportation | Sweden, Brazil | 24%, 22% of country's total transport energy |

| Heat | Denmark, Sweden | 30%, 25% of country's heat consumption |

Source: [2]

Experimental Protocols and Research Methodologies

Biomass Characterization Protocol

Objective: To determine the proximate composition of biomass feedstocks for energy conversion suitability.

Materials and Equipment:

- Analytical balance (±0.0001 g)

- Muffle furnace

- Crucibles

- Desiccator

- Oven

- Thermogravimetric analyzer

Procedure:

- Moisture Content: Weigh 1g of sample (W1), dry at 105°C for 24 hours, reweigh (W2). Calculate moisture % = [(W1 - W2)/W1] × 100

- Volatile Matter: Heat dried sample at 950°C for 7 minutes in covered crucible, cool in desiccator, weigh. Calculate volatile matter %.

- Ash Content: Heat residue from volatile matter test at 750°C for 6 hours, cool in desiccator, weigh. Calculate ash %.

- Fixed Carbon: Calculate by difference: 100% - (Moisture% + Volatile% + Ash%)

Anaerobic Digestion Experimental Protocol

Objective: To evaluate biogas production potential from different organic waste streams.

Materials and Equipment:

- Anaerobic digesters (batch or continuous)

- Gas collection system

- pH meter

- COD (Chemical Oxygen Demand) test kit

- Gas chromatograph

- Temperature-controlled environment

Procedure:

- Inoculum Preparation: Collect active digester material from wastewater treatment plant, acclimatize to experimental temperature (35°C for mesophilic, 55°C for thermophilic).

- Substrate Characterization: Determine total solids, volatile solids, and C/N ratio of feedstock.

- Reactor Setup: Fill reactors with inoculum-substrate mixture at recommended volatile solids loading rate.

- Monitoring: Daily measure biogas production by water displacement, biogas composition (CH4, CO2) by GC, and pH.

- Analysis: Calculate biochemical methane potential (BMP) as mL CH4/g VS added over 30-day period.

Biofuel Quality Assessment Protocol

Objective: To determine key fuel properties of biodiesel produced from various feedstocks.

Materials and Equipment:

- Gas chromatography with FID

- Flash point tester

- Viscosity meter

- Acid number titration setup

- Oxidation stability apparatus

Procedure:

- Ester Content: Analyze by GC according to EN 14103 using methyl heptadecanoate as internal standard.

- Flash Point: Determine using closed cup flash point tester per ASTM D93.

- Viscosity: Measure at 40°C using viscometer per ASTM D445.

- Acid Value: Titrate with 0.1M KOH using phenolphthalein indicator per ASTM D664.

- Oxidation Stability: Conduct Rancimat test at 110°C with air flow of 10 L/h per EN 14112.

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomass Analysis

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Phenolphthalein Indicator | Acid-base titration endpoint detection | Biodiesel acid number determination |

| 0.1M KOH Solution | Titrant for acidity measurement | Free fatty acid quantification |

| Methyl Heptadecanoate | Internal standard for GC analysis | Biodiesel ester content determination |

| COD Digestion Solution | Oxidation of organic compounds | Chemical oxygen demand measurement |

| Van Soest Solution | Fiber fractionation | Biomass compositional analysis |

Sustainability Considerations and Environmental Impact

The environmental implications of biomass energy are complex and multifaceted, requiring careful analysis across its entire lifecycle.

Carbon Neutrality Debate

A central controversy surrounding biomass energy concerns its carbon neutrality. Advocates for biomass argue it is carbon neutral because the carbon released during combustion is reabsorbed by new plant growth through photosynthesis [2]. However, in many cases, this claim does not hold true [2]. Studies show it takes 40-100 years for forests clear-cut for commercial biomass to regrow and reabsorb carbon from the atmosphere, and regrowth is uncertain due to potential fire, insect damage, and re-harvest [2]. In the interim, the released carbon contributes to climate change [2].

Research indicates that biomass power plants emit 50-60% more CO2 per megawatt-hour than modern coal plants [5]. Even assuming trees grow back, net CO2 emissions from burning forest wood exceed emissions from fossil fuels for decades to over a century [5]. Generating electricity with wood is hugely resource-intensive, requiring more than an acre's worth of wood per hour to fuel a typical 50-MW power plant [5].

Air Quality Impacts

Biomass combustion, especially for residential heating, represents one of the largest sources of air pollution [5]. Traditional biomass use generates severe indoor air pollution with significant human health effects, responsible for almost 3 million deaths in 2023 [2]. Even modern commercial biomass systems can emit harmful pollutants, including particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, and sulfur dioxide, though advanced emission control technologies can mitigate these impacts.

Land Use and Ecosystem Impacts

The land requirements for biomass production present significant environmental challenges. Biomass energy can potentially compete with agricultural land and resources for food crops, particularly when dedicated energy crops are grown on arable land [2]. The practice of planting single crops (monoculture) for biomass degrades soil and reduces biodiversity [2]. Additionally, the use of pesticides and fertilizer for energy crop production harms water quality and can require substantial water usage [2].

In some regions, bioenergy crop production has induced deforestation; for example, in Southeast Asia, rainforests were converted to palm oil plantations to feed the EU's demand for biodiesel [2]. Similarly, the increase in fertilizer use for corn ethanol has contributed to the dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico [2].

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The future development of biomass energy faces both challenges and opportunities that will shape its role in the broader renewable energy portfolio.

Advanced Feedstocks

Algal biomass represents a promising frontier for bioenergy research. Algae can be grown in ocean water, avoiding competition with freshwater resources and arable land [1]. Its rapid growth rate—up to 30 times faster than food crops—makes it particularly attractive [1]. Research focuses on improving algal strain selection, cultivation systems, and harvesting techniques to enhance economic viability.

Dedicated energy crops bred specifically for high yield, low input requirements, and compatibility with marginal lands offer another promising pathway [4]. These include fast-growing trees such as willow and poplar, as well as perennial grasses like switchgrass and miscanthus [4].

Conversion Technology Innovations

Advanced biofuel production pathways, particularly those focusing on lignocellulosic biomass, hold potential for significantly expanding the feedstock base while reducing competition with food production [4] [1]. Gasification technologies that can efficiently convert diverse feedstocks into syngas for subsequent catalytic conversion to liquid fuels represent an active area of research and development [1].

The integration of biomass conversion with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) creates the potential for negative emissions, where more carbon is removed from the atmosphere than is released [1]. Biochar systems also offer carbon sequestration benefits when biochar is added to agricultural soils, where it can continue to absorb carbon and form large underground stores of sequestered carbon [1].

Portfolio Optimization Approaches

Future research will continue to refine methodologies for optimizing renewable energy project portfolios that include biomass resources. The hybrid AIS-AFS algorithm represents one approach to solving the complex multi-objective optimization problem of maximizing net present value while minimizing investment risk [7]. Such methodologies must balance technical, economic, and sustainability objectives while accounting for uncertainties in technology development, market conditions, and policy frameworks [7] [8].

As restrictions on fossil fuel usage become more stringent, investment in renewable energy projects presents an increasingly appealing opportunity [7]. The numerical results of recent research indicate that hybrid optimization algorithms can outperform individual algorithms in terms of profitability at specific investment risk thresholds [7]. Furthermore, the geographical distribution of selected projects reveals a deliberate effort to avoid concentration in any specific region, demonstrating a commitment to identifying optimal investment opportunities globally [7].

The Carbon Cycle and Renewable Credentials of Biomass

Biomass energy, derived from organic matter such as wood, agricultural residues, and waste, represents a significant component of the global renewable energy landscape. It accounts for approximately 4.8% of total U.S. energy consumption and about 12% of all U.S. renewable energy [9]. Globally, over 2 billion people still rely on traditional biomass for cooking and heating, while commercial biomass provides about 6% of total end-use energy consumed worldwide [2]. Biomass is classified as a semi-renewable resource because its sustainability depends critically on management practices that ensure replenishment rates exceed consumption [2].

The fundamental premise of biomass energy lies in its participation in the biogenic carbon cycle. Unlike fossil fuels, which transfer carbon from geological storage into the atmosphere, biomass energy utilizes carbon that is already actively circulating between the atmosphere, terrestrial vegetation, and soils [10]. This technical guide examines the carbon cycle dynamics of biomass systems, evaluates their renewable credentials through scientific assessment methodologies, and contextualizes their role within comprehensive renewable energy portfolios.

Biomass in the Carbon Cycle

Carbon Cycle Fundamentals

The Earth's carbon exists in two primary domains: the fast (active) domain and the slow (geologic) domain. The fast domain encompasses carbon stored in the atmosphere, oceans, land plants, animals, soils, freshwater, and biobased products, where carbon exchange occurs over periods ranging from years to centuries. In contrast, the slow domain involves geological formations where carbon turnover times exceed 10,000 years [10]. Fossil fuels belong to this slow domain, and their combustion represents a net addition of carbon to the active carbon cycle.

Biomass energy systems operate within the fast carbon domain. The carbon dioxide (CO₂) released during biomass combustion represents carbon recently removed from the atmosphere through plant photosynthesis. This creates a theoretically closed loop where subsequent plant growth can reabsorb the emitted carbon [10]. The net effect on atmospheric CO₂ levels, however, is determined by how the entire bioenergy system affects multiple carbon flows, including impacts on ecosystem carbon storage and the timing of emissions and removals [10].

Figure 1: Biomass Carbon Cycle Flow. Biomass energy operates within the fast carbon cycle (green/red), where combustion emissions can be recaptured by new plant growth. Fossil fuels (gray) transfer carbon from geological storage to the atmosphere, resulting in a net increase in atmospheric CO₂.

Comparative Carbon Dynamics: Biomass vs. Fossil Fuels

The critical distinction between biomass and fossil fuels lies in their different positions within the carbon cycle. While both release CO₂ when combusted, their net contributions to atmospheric CO₂ levels differ fundamentally:

- Fossil fuel combustion transfers carbon from geological storage (where it was isolated from the active carbon cycle) directly into the atmosphere, resulting in a net increase in atmospheric CO₂ concentrations [10]

- Biomass combustion returns to the atmosphere carbon that was recently sequestered by growing plants, creating a potential carbon cycle that could balance emissions with sequestration over time [10]

However, this theoretical carbon neutrality depends heavily on the timeframe considered, forest management practices, and the specific biomass feedstocks used [9]. The carbon debt created when biomass is harvested and burned may take decades to centuries to repay through regrowth, during which time atmospheric CO₂ levels remain elevated compared to alternative scenarios [9] [5].

Quantitative Assessment of Biomass Carbon Emissions

Global Warming Potential Comparison

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) represents the most rigorous methodology for evaluating the environmental sustainability of biomass energy systems. LCA quantifies all resource consumption and emissions associated with a product throughout its lifetime, from creation to disposal [11]. Research comparing poplar-produced jet fuel to conventional petroleum-based jet fuel demonstrates the potential greenhouse gas benefits of advanced biomass systems:

Table 1: Global Warming Potential (GWP) Comparison of Jet Fuel Production Pathways

| Fuel Type | Production Process | Net GWP | Key Contributing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Petroleum-based Jet Fuel | Conventional refining | High | Combustion emissions (positive), fossil fuel extraction and processing (positive) |

| Poplar-based Bio-jet Fuel | Biorefinery conversion | Significantly lower | CO₂ sequestration from growing poplar trees (negative), displacement of fossil electricity with wood waste combustion (negative), biorefinery combustion (positive), fuel use (positive) [11] |

Emission Factors Across Energy Technologies

The climate impact of biomass energy varies significantly depending on the feedstock, technology efficiency, and time horizon considered. Actual emissions at the point of combustion can exceed those from fossil fuels:

Table 2: Comparative CO₂ Emissions Across Electricity Generation Technologies

| Technology | CO₂ Emissions Relative to Modern Coal | CO₂ Emissions Relative to Natural Gas Combined Cycle | Primary Factors Influencing Emissions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modern Coal Plant | Baseline (100%) | 285% higher | Chemical composition of coal, plant efficiency |

| Natural Gas Combined Cycle | Approximately 65% lower | Baseline (100%) | Higher efficiency, lower carbon content of fuel |

| Biomass Power Plant | 50-65% higher [5] | 300-400% higher [5] | Lower energy density of wood, lower operating efficiencies (typically 24-29% for utility-scale plants) [5] |

| Biomass with CCS (BECCS) | Net negative (potential) | Net negative (potential) | Geological carbon storage, carbon capture from biogenic sources [10] |

The high stack emissions from biomass plants are compounded by the degradation of forest carbon uptake capacity when forests are harvested for fuel. This combined effect contributes to significant "net" emissions for biomass power that may persist for decades [5].

Methodologies for Assessing Biomass Sustainability

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Protocol

Life Cycle Assessment provides a standardized methodology for evaluating the comprehensive environmental impacts of biomass energy systems:

Goal and Scope Definition: Clearly define the assessment objectives, system boundaries, and functional unit (e.g., 1 megawatt-hour of electricity or 1 gigajoule of biofuel) [11]

Inventory Analysis: Quantify all resource inputs (water, fertilizer, energy) and emission outputs (CO₂, NOx, particulate matter) across the entire supply chain, including:

- Feedstock production and collection

- Transportation and processing

- Conversion to energy

- Distribution and end-use [11]

Impact Assessment: Evaluate potential environmental impacts using categorized indicators, with Global Warming Potential (GWP) being particularly crucial for biomass systems [11]

Interpretation: Analyze results to identify significant issues, evaluate sensitivity, and provide conclusions and recommendations limited by the study scope and methodology

Carbon Accounting Methodologies

Accurate carbon accounting for biomass energy requires consideration of several critical factors:

- Temporal Boundaries: Specify the time horizon for assessment (short-term vs. long-term carbon balance) [9]

- Spatial Boundaries: Account for direct and indirect land use changes, including potential international leakage effects [9]

- Baseline Scenarios: Establish appropriate counterfactual scenarios (what would happen to the biomass if not used for energy) [5]

- Carbon Stock Changes: Quantify impacts on carbon stored in forests, soils, and long-lived wood products [10]

The carbon neutral assumption for biomass has been scientifically challenged. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency determined that "carbon neutrality cannot be assumed for all biomass energy a priori" [9]. The timeframe for carbon parity varies significantly—from years for agricultural residues to decades or centuries for forest biomass—depending on feedstock type, forest management practices, and combustion technology [9].

Biomass in Renewable Energy Portfolios

Integration with Broader Renewable Energy Systems

Renewable Energy Portfolios represent strategic collections of investments in renewable energy sources, technologies, and projects designed to diversify energy resources, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and enhance energy security [3]. Within such portfolios, biomass can provide distinct advantages:

- Dispatchable Power: Unlike intermittent solar and wind resources, biomass can generate electricity on demand, providing grid stability and reliability services [6]

- Baseload Capacity: Biomass power plants can operate continuously, complementing variable renewable resources [6]

- Carbon Removal Potential: When combined with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), biomass energy can generate negative emissions, crucial for meeting climate targets [10]

Economic Considerations

Clean energy portfolios that include biomass can offer cost-effective alternatives to fossil fuel investments. Research indicates that optimized clean energy portfolios—including renewable energy and distributed energy resources—can often be procured at 8-60% lower cost than new natural gas plants while providing equivalent grid services [6]. These portfolios unlock significant market opportunities while avoiding billions of tons of CO₂ emissions [6].

Research Reagents and Tools for Biomass Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Biomass Carbon Cycle Analysis

| Research Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Application in Biomass Research |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Instruments | Elemental Analyzers, Gas Chromatographs, Mass Spectrometers | Quantify carbon content in biomass feedstocks, measure greenhouse gas emissions from combustion, analyze biofuel composition |

| Modeling Software | Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) software, Carbon accounting models, Forest growth models | Simulate carbon flows over time, calculate net carbon balance of biomass systems, project forest regrowth and carbon sequestration rates |

| Field Measurement Equipment | Soil carbon probes, Dendrometers, Leaf area indices, Eddy covariance towers | Monitor ecosystem carbon stocks, measure plant growth rates, quantify atmospheric carbon fluxes in biomass production landscapes |

| Laboratory Reactors | Anaerobic digesters, Gasifiers, Pyrolysis units, Fermentation systems | Convert biomass to energy carriers under controlled conditions, optimize conversion processes, characterize reaction products |

| Remote Sensing Technologies | LiDAR, Multispectral imagers, Satellite monitoring systems | Assess biomass availability at landscape scales, monitor land use changes, detect deforestation from unsustainable harvesting |

Advanced Biomass Pathways and Carbon Management

Carbon Capture and Storage/Utilization

Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) and Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Utilization (BECCU) represent advanced pathways that can transform biomass energy from a potentially carbon-neutral source to a carbon-negative technology:

- BECCS: Captures CO₂ emissions from bioenergy facilities and injects them into geological reservoirs for long-term storage, effectively removing CO₂ from the atmosphere [10]

- BECCU: Captures CO₂ and incorporates it into products, keeping carbon out of the atmosphere while creating valuable commodities [10]

- Biochar Production: Converts biomass into stable carbon-rich charcoal that can be applied to soils, sequestering carbon for decades to centuries while potentially improving soil health [10]

Sustainable Biomass Feedstock Management

The carbon impact of biomass energy depends fundamentally on feedstock management. Key considerations include:

- Waste Utilization: Using true waste residues (agricultural, forestry, municipal) typically offers better carbon outcomes than dedicated harvesting of standing trees [2]

- Forest Management: Appropriate rotation periods, protection of high-carbon stocks, and avoidance of conversion of natural ecosystems are critical for climate-beneficial biomass [9]

- Integrated Systems: Combining biomass production with other land uses can enhance sustainability, though potential competition with food production must be carefully managed [2]

The renewable credentials of biomass energy within the carbon cycle are complex and context-dependent. While biomass theoretically operates within a closed carbon loop, in practice, its climate impact varies significantly based on feedstock type, supply chain management, time horizon considered, and alternative land uses. When developed with rigorous sustainability standards and appropriate carbon accounting, biomass can contribute meaningfully to renewable energy portfolios, particularly through provision of dispatchable power and potential carbon removal via BECCS. However, current scientific evidence indicates that not all biomass is equally beneficial, and policies must differentiate between high-risk and climate-positive biomass pathways to ensure genuine greenhouse gas reductions.

Biomass, an abundant domestic resource, encompasses organic materials derived from agricultural residues, forestry byproducts, municipal waste, and other biological sources [4]. These resources have been utilized since humans first began burning wood for cooking and heating [4]. In the contemporary context of global carbon neutrality goals and circular bio-economy development, the accurate quantification and sustainable management of agricultural and forestry residues have become critical research priorities [12] [13]. The efficient use of these resources can significantly contribute to reducing greenhouse gas emissions, minimizing non-point pollution, and enhancing soil health while providing valuable feedstocks for bioenergy and bioproducts [14] [12].

Agricultural, fishery, forestry, and agro-processing activities generate substantial quantities of residues, by-products, and waste materials annually [12]. Inappropriate disposal and inefficient utilization of these resources contribute to environmental pollution and economic losses [12]. For instance, the burning of crop residues alone results in nearly complete loss of organic carbon and nitrogen, along with substantial losses of phosphorus (25%), potassium (20%), and sulfur (5–60%) [12]. In 2019, approximately 458 million metric tons of crop residue were burned globally, emitting 1,238 kilotons of methane (CH₄) and 32 kilotons of nitrous oxide (N₂O) [12]. Conversely, the strategic utilization of these residues can address waste management challenges while contributing to renewable energy portfolios and sustainable material flows [4] [13].

Global Quantification of Agricultural Residues

Agricultural Biomass Wastes (ABWs) consist of organic materials discarded during agricultural production processes, representing the difference between material and energy inputs and outputs within agricultural production and reproduction cycles [13]. These residues constitute the most plentiful and cost-effective organic waste obtained from agricultural processes and can be converted into various value-added products [13]. ABWs include residues from the growing and processing of raw agricultural products such as fruits, vegetables, meat, poultry, dairy products, and crops [13]. They are characterized by large output, diverse types, widespread distribution, potential for reuse, and susceptibility to cause environmental pollution [13].

The composition of ABWs varies significantly in terms of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content, which plays a crucial role in determining appropriate resource utilization technologies [13]. In a broad sense, ABWs represent the difference between resource inputs and outputs of material and energy across the entire agricultural chain, including planting, breeding, production, processing, and consumption [13]. These wastes can be in solid, liquid, or slurry form, depending on the nature of agricultural activities [13].

Quantitative Assessment of Global Agricultural Residues

Comprehensive data on global agricultural residue production has been limited until recent developments. The newly established Organic Matter Database (OMD) represents a significant advancement in consolidating global residue data from agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and related industries [12]. This database provides critical information on quantities and nutrient concentrations of residues and by-products globally, addressing a fundamental knowledge gap in biomass resource quantification [12].

Table 1: Global Agricultural Residue Production and Utilization Potential

| Residue Category | Annual Global Production | Current Utilization Status | Potential Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crop Residues | 458 million tons burned annually (2019 data) | Significant portion burned or inappropriately disposed | Soil amendment, bioenergy, animal feed, industrial applications |

| Livestock Manure | Large quantities (regionally variable) | Causes non-point pollution where disposal unregulated | Biogas production, organic fertilizer |

| Slaughterhouse Residues | Not fully quantified globally | Often disposed in open dumps and landfills | Bioenergy, specialized products |

| Agro-processing Wastes | Approximately 1.3 billion metric tons food waste annually | Inefficiently managed in many regions | Biorefinery feedstocks, value-added products |

The scale of agricultural residue generation is substantial, with at least one-third of global food production (approximately 1.3 billion metric tons) being squandered as waste each year [13]. This represents not only a significant resource loss but also a substantial environmental burden through greenhouse gas emissions and pollution pathways [13]. The OMD database continues to be updated as new production data becomes available through FAOSTAT and country-specific conversion coefficients are developed, enhancing the accuracy of global and regional assessments [12].

Global Quantification of Forestry Residues

Forestry residues encompass a diverse range of materials including woody biomass from natural woodlands, managed forests, fuelwood plantations, and processing byproducts from lumber and paper mills [4] [2]. These resources constitute the nation's largest biomass energy resource, with primary sources including paper mill residue, lumber mill scrap, and forest-derived materials [4]. Forestry biomass can be categorized into primary residues (generated during harvesting, such as branches, tops, and stumps) and secondary residues (generated during processing, such as sawdust, bark, and black liquor) [4] [5].

The quantification of forestry residues is complicated by varying forest management practices, ecological considerations, and competing uses for wood products. Current data indicates that global forests remain in crisis, with 8.1 million hectares of forest lost in 2024 alone—a level of destruction 63% higher than the trajectory needed to halt deforestation by 2030 [15]. Particularly concerning is the loss of humid primary tropical forests, which represent irreplaceable stores of carbon and biodiversity [15]. Additionally, forest degradation affected 8.8 million hectares in 2024, further eroding ecosystem integrity and climate resilience [15].

Quantitative Assessment of Global Forestry Residues

The accurate quantification of forestry residues faces significant challenges due to inconsistent reporting methodologies and varying conversion coefficients across countries [12]. However, emerging data sources and assessment methodologies are improving our understanding of global forestry residue availability.

Table 2: Forestry Residue Production and Carbon Impact

| Residue Category | Annual Availability | Carbon Sequestration Potential | Management Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Logging Residues (slash) | Regionally variable; often insufficient for proposed biomass plants | High uncertainty in regrowth carbon sequestration (40-100 years) | Scarcity for energy production, competing ecosystem services |

| Processing Mill Residues | Significant from paper and lumber mills | Better characterized than logging residues | Existing uses, market competition |

| Fuelwood Plantations | Increasing with dedicated energy crops | Dependent on species and management practices | Land use competition with food crops |

| Urban Wood Waste | Growing with construction and demolition activities | Waste diversion benefits | Contamination, collection logistics |

The utilization of forestry residues for energy generation has expanded significantly, with the United States dominating the wood pellet export market. In 2023, the U.S. exported 8.8 million metric tons, representing 29% of total global wood pellet exports [2]. Most exports go to Europe and originate mainly from forests in the Southeast U.S., where 85% (9.2 million tons/year) of the nation's wood pellet manufacturing capacity is located, primarily in North Carolina and Georgia [2].

Methodologies for Residue Quantification and Assessment

The Organic Matter Database (OMD) Framework

The Organic Matter Database (OMD) represents a groundbreaking methodological framework for consistent classification, estimation, and reporting of various residues and by-products [12]. Developed to address critical gaps in global biomass resource accounting, the OMD provides:

- Standardized Definitions and Typologies: Clear classifications for different categories of organic resources to aid consistent reporting [12]

- Global Consolidation of Residue Data: Comprehensive data on quantities and nutrient concentrations of residues from agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and related industries [12]

- Regional and Global Estimates: Assessment of residues and by-products potentially available for use in a circular bio-economy [12]

The methodology involves systematic compilation of production data from FAOSTAT and other authoritative sources, application of country-specific conversion coefficients, and continuous updating as new data becomes available [12]. This approach enables more accurate quantification of residue availability at national and sub-national levels, supporting evidence-based policies and actions in sustainable resource utilization [12].

Biomass Accumulation Assessment Techniques

Optimizing biomass accumulation is crucial for increasing crop yields and enhancing carbon sequestration. By 2025, proper management could increase average crop yields by up to 25% in sustainable agriculture systems [14]. Key assessment methodologies include:

Biomass Assessment Workflow

Satellite Monitoring and Remote Sensing: Advanced technologies utilizing multispectral satellite imagery and machine learning to monitor plant growth, vegetation health (NDVI), and soil conditions across agricultural lands and forests worldwide [14]. These systems enable real-time tracking of biomass accumulation and facilitate precision management practices.

Precision Nutrient Management: Using sensors and real-time monitoring to tailor fertilizer applications enhances biomass growth without environmental degradation [14]. This approach allows for site-specific management based on accurate vegetation and soil data.

Carbon Footprinting Tools: Quantitative methods that enable commercial foresters and policymakers to quantify the impact of forestry projects on carbon sequestration, promoting transparency and climate accountability [14].

Research Reagents and Analytical Tools

The accurate quantification and characterization of biomass resources requires specialized analytical tools and research reagents. The following table details essential materials and their applications in biomass research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Analytical Tools for Biomass Assessment

| Research Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multispectral Satellite Imagery | Monitors plant growth, vegetation health (NDVI), and soil conditions | Large-scale biomass accumulation monitoring [14] |

| Soil Sensors (IoT) | Measures real-time soil moisture, nutrient levels, and temperature | Precision agriculture for optimizing biomass growth [14] |

| Spectroscopic Analysis Kits | Rapid determination of nutrient content in plant tissues | Quality assessment of biomass resources [12] |

| Anaerobic Digestion Assays | Evaluates biogas production potential from organic residues | Bioenergy potential assessment [13] |

| Lignocellulose Composition Kits | Quantifies cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content | Determining appropriate utilization pathways [13] |

| Blockchain Traceability Systems | Ensures secure and traceable supply chains for biomass | Sustainability verification and supply chain transparency [14] |

Applications and Utilization Pathways

Bioenergy Production Technologies

Biomass resources can be converted into valuable energy carriers through several technological pathways:

Biopower Technologies: These convert biomass fuels into heat and electricity using processes including direct combustion, bacterial decay, and conversion to gas/liquid fuel [4]. Utility-scale plants typically operate at approximately 24% efficiency, with the largest plants reaching about 29% efficiency [5]. Combined heat and power (CHP) applications can increase overall plant efficiency by utilizing waste heat [5].

Biofuels Production: Transportation fuels such as ethanol and biodiesel are created by converting biomass into liquid fuels [4]. The most common feedstocks for biofuels are currently corn grain (for ethanol) and soybeans (for biodiesel), with ongoing development of advanced biofuels from lignocellulosic materials [4].

Bioproducts Manufacturing: Beyond energy applications, biomass can be converted into chemicals for making plastics and other products that are typically petroleum-based [4]. This includes the production of natural fibers, polymers, biosorbents, and reinforcement materials in composites [12].

Sustainable Management Practices

Optimizing biomass accumulation requires integrating traditional ecological knowledge with advanced technologies. Key strategies include:

Biomass Management Strategies

Agricultural Practices:

- Cover Cropping: Planting non-cash crops to increase total organic matter production, improve nutrient cycling, and protect soil [14]. This practice can increase biomass by 3-8 tons/ha and improve yields by 5-15% [14].

- Conservation Tillage: Reducing soil disturbance to allow more biomass residues to decompose and stabilize soil organic carbon stocks [14]. This approach can increase biomass by 2-6 tons/ha and sequester 0.4-0.9 tons CO₂e/ha/year [14].

- Agroforestry Systems: Integrating trees and mixed species with crops to diversify biomass, enhance microclimate regulation, and promote higher total productivity on farmland [14]. These systems can increase biomass by 8-20 tons/ha and improve yields by 10-25% [14].

Forestry Practices:

- Selective Harvesting and Thinning: Enabling the most vigorous trees to maximize growth and total biomass accumulation [14].

- Afforestation & Reforestation: Planting trees on degraded or cleared lands to rapidly improve biomass stocks and restore ecosystem function [14].

- Mixed-Species Plantations: Establishing diverse tree plantings that accumulate more biomass than monocultures by optimally utilizing available resources and increasing resilience to pests, diseases, and climate variability [14].

Environmental Impacts and Sustainability Considerations

Climate Change Implications

The climate impact of biomass utilization spans from low to high, depending on specific practices and feedstocks [2]. Key considerations include:

Carbon Neutrality Debate: While advocates for biomass argue it is carbon neutral because carbon released during combustion is reabsorbed by new plant growth, this is not always valid [2]. Studies show it takes 40-100 years for forests clear-cut for commercial biomass to regrow and reabsorb atmospheric carbon, with regrowth uncertain due to potential fire, insect damage, or re-harvest [2].

Emissions Profile: Biomass power plants emit 50-60% more CO₂ per megawatt-hour than modern coal plants [5]. Even assuming trees grow back, net CO₂ emissions from burning forest wood exceed emissions from fossil fuels for decades to over a century [5]. Typical CO₂ emissions at utility-scale biomass plants are 150% those of coal plants and 300-400% those of natural gas facilities [5].

Positive Potential: Despite these challenges, using waste streams for bioenergy can reduce climate and environmental impacts [2]. Improved biomass management could sequester up to 1.5 gigatons of CO₂ globally in forests by 2025 [14].

Environmental and Health Impacts

Biomass utilization carries medium to high environmental impacts, including:

Air Pollution: Biomass burning generates significant air pollutants, particularly from vehicles burning biofuels that deteriorate urban air quality and human health [2]. Traditional biomass use for cooking and heating generates severe indoor air pollution, causing almost 3 million deaths in 2023 [2].

Deforestation and Land Use: Bioenergy crop production may induce deforestation, as seen in Southeast Asia where rainforests were converted to palm oil plantations to meet EU biodiesel demand [2]. Agricultural processes can impact soil, water resources, and local biodiversity, with increased fertilizer use for corn ethanol contributing to dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico [2].

Water Resources: Biomass production can require substantial water usage and contributes to water pollution through agricultural runoff [2].

The quantification and sustainable management of global agricultural and forestry residues represent a critical component of renewable energy portfolios and circular bio-economy strategies. The development of comprehensive databases like the Organic Matter Database (OMD) marks significant progress in addressing previous data gaps and inconsistencies [12]. Current evidence indicates substantial potential for enhanced utilization of these resources, with agricultural residues alone encompassing approximately 1.3 billion metric tons of annual food waste globally [13].

The sustainable management of biomass resources requires careful consideration of trade-offs between energy production, environmental protection, and social benefits. While biomass offers promising pathways for reducing reliance on fossil fuels and utilizing waste streams, its climate benefits are not automatic and depend heavily on specific feedstocks, management practices, and time horizons [5] [2]. Practices such as cover cropping, agroforestry, conservation tillage, and advanced monitoring technologies demonstrate significant potential for optimizing biomass accumulation while delivering co-benefits for soil health, carbon sequestration, and ecosystem resilience [14].

Future research priorities should include refined quantification methodologies, development of efficient conversion technologies, and comprehensive sustainability assessments that account for temporal dimensions of carbon fluxes and ecosystem impacts. As global efforts to achieve carbon neutrality intensify, the strategic management of biomass resources will play an increasingly important role in renewable energy portfolios and circular economy transitions.

Within the context of renewable energy portfolio research, biomass energy derives from a wide array of organic materials, collectively known as feedstocks [16]. These resources are biological in origin, derived from living or recently living organisms, and are available on a renewable basis for conversion into heat, electricity, and transportation fuels [17] [18]. The strategic inclusion of diverse biomass feedstocks is crucial for building a resilient and sustainable renewable energy portfolio, as it diversifies energy resources, enhances energy security, and contributes to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions [3] [19]. A robust bioenergy industry can supply domestic energy sources, reduce dependence on foreign oil, generate jobs, and revitalize rural economies [19]. Understanding the characteristics, availability, and applications of these feedstocks is a fundamental component of biomass energy basics and essential for informed research and policy-making.

Classification and Characterization of Biomass Feedstocks

Biomass feedstocks can be categorized based on their origin, composition, and physical state. The primary categories include dedicated energy crops, agricultural residues, forestry residues, algae, wood processing residues, and various waste streams, including municipal solid waste and wet wastes [16]. The following table summarizes the key types of biomass feedstocks, their descriptions, and common examples.

Table 1: Classification of Biomass Feedstocks

| Feedstock Category | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Dedicated Energy Crops [16] | Non-food crops grown on marginal land specifically for biomass production. | Herbaceous crops: Switchgrass, Miscanthus, Bamboo. Short-rotation woody crops: Hybrid poplar, Hybrid willow. |

| Agricultural Residues [16] | Stalks, leaves, and other byproducts left in fields after harvest. | Corn stover, Wheat straw, Oat straw, Barley straw, Sorghum stubble. |

| Forestry Residues [16] | Material left after timber harvest or whole trees from forest management. | Logging residues (limbs, tops), culled trees, thinned biomass. |

| Algae [16] | A diverse group of highly productive aquatic organisms. | Microalgae, Macroalgae (seaweed), Cyanobacteria. |

| Wood Processing Residues [16] | Byproducts and waste streams from wood product manufacturing. | Sawdust, Bark, Branches. |

| Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) [16] | Mixed commercial and residential garbage. | Yard trimmings, Paper, Plastics, Rubber, Leather, Textiles, Food wastes. |

| Wet Wastes [16] | Organic-rich waste streams with high moisture content. | Food waste, Biosolids, Manure slurries, Industrial organic wastes. |

The versatility of these feedstocks is a key advantage. They can be converted into liquid transportation fuels equivalent to fossil-based fuels, used to generate biopower for heat and electricity, or manufactured into bioproducts like plastics and industrial chemicals [19]. This mimics the petroleum refinery model, where integrated biorefineries can produce bioproducts alongside biofuels, creating a more efficient and cost-effective approach to utilizing biomass resources [19].

Quantitative Data on Feedstock Potential and Conversion

The assessment of feedstock potential is critical for planning and scaling bioenergy development. The following table provides quantitative data on the potential yields and energy output for various feedstock categories, based on simulation parameters and literature reviews [18].

Table 2: Feedstock Potential and Energy Output Estimates

| Feedstock Category | Key Quantitative Metrics | Representative Energy Output/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Dedicated Energy Crops [18] | Average biomass yield (e.g., for switchgrass): ~10-15 dry tons/acre/year. | Biofuel yield, total bioenergy production (GJ/ha), gross electricity/heat production. |

| Agricultural Residues [18] | Residue-to-product ratio (RPR); e.g., Corn stover RPR ~0.8-1.2. | Biomethane yield via anaerobic digestion; biogas for heat/electricity. |

| Forest Plantations [18] | Tonnage of crop produced per specific land area (t/ha). | Solid biofuels for combustion; gross electricity production at plant gate. |

| Livestock Waste [18] | Biogas yield per unit mass of volatile solids (m³/kg VS). | Biogas for heating, electricity generation, or purified as transportation fuel. |

| Municipal Solid Waste [18] | Total biomass production from sorted MSW. | Energy output for electricity or heat via combustion or gasification. |

In the United States, the potential volume of biomass is significant. According to the U.S. Department of Energy’s 2023 Billion-Ton Report, at a cost of $70 per dry ton, the nation can produce approximately 0.7 to 1.7 billion dry tons of biomass annually. This level of production could support the manufacture of an estimated 60 billion gallons of low-emission liquid fuels, thereby substantially decarbonizing the transportation sector [19]. Furthermore, leveraging purpose-grown energy crops can achieve a net flux reduction of about 18 million metric tons of CO₂ [19].

Methodologies for Feedstock Assessment and Experimental Analysis

Technical assessment of biomass feedstocks requires standardized analytical procedures and sophisticated modeling tools. Researchers and scientists rely on a suite of methodologies to evaluate the economic and environmental impacts of biomass development options.

Core Analytical and Modeling Tools

The U.S. Department of Energy's Bioenergy Technologies Office and national laboratories provide several key online tools for data analysis and decision-making [20]:

- Bioenergy Knowledge Discovery Framework (KDF): A Geographic Information System (GIS)–based framework that allows for the synthesis, analysis, and visualization of vast amounts of information to analyze the economic and environmental impacts of biomass feedstocks and biorefineries [20].

- Biofuels Atlas: An interactive map that illustrates the locations of American feedstocks, bioenergy plants, and fossil fuel infrastructure, allowing for analysis of bioenergy resources and incentives [20].

- Biomass Scenario Model (BSM): A model that simulates the potential policy impacts on the domestic biofuels supply chain, testing the feasibility and side effects of incentives like tax credits and R&D funding [20].

- GREET (Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy use in Technologies) Suite: A suite of tools for life-cycle analysis to evaluate the energy and emission impacts of advanced vehicle technologies and new transportation fuels [20].

- Standard Laboratory Analytical Procedures: The National Renewable Energy Laboratory provides tested and accepted methods for performing analyses common in biofuels research, such as biomass compositional analysis and bio-oil analysis. These procedures are critical for determining the chemical makeup of feedstocks, which directly influences conversion efficiency and fuel yield [20].

Workflow for Biomass Resource Assessment

The International Renewable Energy Agency's (IRENA) Bioenergy Simulator outlines a standard methodology for assessing bioenergy potential. The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for conducting such an assessment, from defining the area of interest to interpreting the results.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers conducting experimental work on biomass feedstocks, particularly in conversion processes like anaerobic digestion or hydrolysis-fermentation, a standard set of reagents and materials is required. The following table details key items and their functions.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Biomass Conversion Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic Digestion Inoculum | Provides a consortium of microorganisms to initiate and sustain methane production. | Starting culture in biomethane potential (BMP) assays for wet waste feedstocks [18]. |

| Cellulase & Hemicellulase Enzymes | Catalyze the hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose into fermentable sugars. | Saccharification of agricultural residues (e.g., corn stover) for bioethanol production [18]. |

| Yeast (S. cerevisiae) / Bacteria | Ferments simple sugars into ethanol or other target chemicals. | Fermentation step in lignocellulosic ethanol production [18]. |

| Chemical Pretreatment Agents | Breaks down lignin and disrupts crystalline cellulose structure to improve digestibility. | Dilute acid, alkali, or ionic liquid pretreatment of woody biomass [17]. |

| Nutrient Media (N, P, K) | Provides essential nutrients for microbial growth in biological conversion processes. | Enhancing biogas yield in anaerobic digesters or promoting algae growth [16]. |

| Solvents for Extraction | Extracts lipids or other valuable components from biomass. | Lipid extraction from microalgae for biodiesel production [16]. |

Integration into a Renewable Energy Portfolio and Future Directions

The integration of biomass energy, derived from diverse feedstocks, is a critical element of a comprehensive renewable energy portfolio. Such a portfolio is a strategic collection of investments in renewable energy sources aimed at diversifying resources, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and mitigating climate change [3]. Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS), which are state or national policies requiring utilities to obtain a certain percentage of their electricity from renewable sources, have been a key driver in this deployment [21] [3]. Analyses indicate that the benefits of these policies, including increased renewable energy generation from sources like biomass, have exceeded their costs [21].

The future of biomass energy systems lies in greater efficiency and deeper integration with other renewable technologies [17]. Hybrid systems, such as those combining biomass with solar or wind, are particularly promising. Biomass can provide a consistent, dispatchable energy supply, compensating for the intermittency of other renewables and thereby enhancing grid stability and reliability [17]. This role as a flexible and reliable power source is essential for the transition to a decarbonized energy system. Continued research and optimization in supply chain logistics, conversion technologies, and sustainability metrics are imperative to fully realize the potential of diverse biomass feedstocks within the global renewable energy landscape [17].

Biomass power generation, the process of producing electricity from organic materials, has cemented its role as a vital component of the global renewable energy mix. As researchers and scientists seek sustainable solutions to meet rising electricity demand while reducing carbon emissions, biomass offers a reliable, dispatchable energy source that complements intermittent renewables like solar and wind. Derived from feedstocks including wood pellets, agricultural residues, and municipal solid waste, biomass serves as a renewable alternative to fossil fuels in electricity production [22]. The current market landscape reflects steady growth driven by technological advancements, supportive policies, and the increasing global emphasis on decarbonization and energy security. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive analysis of the current biomass power capacity, detailed market growth projections, and the methodological frameworks essential for research and development in this critical field.

Current Global Capacity and Market Size

The global biomass power sector has demonstrated substantial growth over the past decade, establishing a significant foundation for future expansion. As of early 2024, the world hosts approximately 4,971 active biomass power plants with a combined installed electrical capacity of 83.8 gigawatts (GW) [23]. This represents a remarkable increase from approximately 88 GW of installed biopower capacity in 2014, surging to about 150.3 GW by 2023—a increase of roughly 71% over that period [24].

The market valuation reflects this substantial infrastructure. In 2024, the global biomass power generation market was valued at US$90.8 billion [22], with more recent estimates for 2025 ranging from $146.58 billion [25] to $161.20 billion [24]. This variance stems from differing methodological approaches in market sizing but confirms a consistently upward trajectory. Regionally, North America has established itself as the dominant market, accounting for approximately 33.8% of the global share in 2025 [25]. The United States alone consumed about 4,978 trillion BTU of biomass energy in 2023, equivalent to roughly 5% of the nation's primary energy supply [24].

Table 1: Current Global Biomass Power Landscape (2023-2025)

| Metric | Value | Year | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Biomass Power Plants | ~4,971 | Early 2024 | [23] |

| Installed Electrical Capacity | 83.8 GW | Early 2024 | [23] |

| Global Installed Biopower Capacity | ~150.3 GW | 2023 | [24] |

| Market Valuation | USD 90.8 - 161.2 Billion | 2024-2025 | [22] [24] |

| North America Market Share | 33.8% | 2025 | [25] |

A key trend enhancing the sector's efficiency is the widespread integration of Combined Heat and Power (CHP) systems. In 2024, approximately 72% of biomass plants globally incorporated CHP technology, improving overall energy efficiency by roughly 15% [24]. Furthermore, the feedstock composition is dominated by solid biomass, which accounted for approximately 85% of the global biomass supply of 54 exajoules (EJ) in 2021 [24]. Pelletized biomass production reached roughly 48 million tons in 2022, facilitating easier transport and combustion [24].

Market Growth Projections and Future Outlook

The biomass power market is on a steady growth trajectory, fueled by global decarbonization efforts, technological innovations, and the pressing need for sustainable waste management solutions. Projections indicate the global market value will reach between US$116.6 billion and US$211.96 billion by 2030-2032, with Compound Annual Growth Rates (CAGR) ranging from 4.3% to 5.4% depending on the specific forecast period and methodology [22] [25]. Looking further ahead to 2035, market size valuations are projected to hit approximately US$157.38 billion [26].

Infrastructure growth mirrors this positive financial outlook. The number of operational biomass power plants is expected to rise to approximately 5,980 by 2033, with a corresponding installed capacity of about 96.8 GW [23]. This represents a significant expansion of the global biomass power infrastructure over the next decade.

Table 2: Biomass Power Market Growth Projections (2025-2035)

| Projection Metric | Base Year (2025) | Projected Year | Projected Value | CAGR | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Market Size Valuation | USD 90.8 Billion (2024) | 2030 | USD 116.6 Billion | 4.3% | [22] |

| Market Size Valuation | USD 146.58 Billion | 2032 | USD 211.96 Billion | 5.4% | [25] |

| Market Size Valuation | USD 79.26 Billion | 2035 | USD 157.38 Billion | 7.1% | [26] |

| Installed Capacity | 83.8 GW | 2033 | 96.8 GW | N/A | [23] |

| Active Power Plants | ~4,971 | 2033 | ~5,980 | N/A | [23] |

Regional dynamics are shifting, with the Asia-Pacific region emerging as the fastest-growing market [25] [26]. This growth is driven by eco-friendly energy initiatives, stringent regulations for CO₂ footprint reduction, and the presence of abundant agricultural residues. For instance, India's Ministry of New and Renewable Energy reported an annual biomass production of around 750 Million Metric Tons (MMT), with 228 MMT being surplus, creating a massive feedstock base for the country's energy needs [26]. Meanwhile, Europe continues to demonstrate considerable growth, supported by sustained policy support and advancements in biomass conversion technologies [26].

Key Technologies and Methodological Frameworks

The efficiency and viability of biomass power generation hinge on a suite of core conversion technologies. For researchers and industry professionals, understanding these methodologies is critical for optimizing existing systems and pioneering new approaches. The dominant technologies include combustion, gasification, and anaerobic digestion, each with distinct operational protocols and applications.

Combustion Technology

Combustion is the most established and widely deployed method, accounting for approximately 42.8% of the biomass power market share in 2025 [25]. The process involves the direct firing of biomass feedstock in a boiler to produce high-pressure steam, which then drives a turbine connected to a generator. Its operational simplicity, fuel flexibility, and technological maturity make it a cornerstone methodology. Furthermore, existing coal-fired power plant infrastructure can be retrofitted for biomass co-firing with minimal modifications, representing a significant strategic opportunity [25] [24]. A key experimental protocol for combustion efficiency analysis involves measuring the calorific value of various feedstocks, monitoring combustion temperature profiles, and analyzing flue gas composition to optimize excess air ratios and minimize pollutant formation.

Gasification Technology

Gasification is an advanced thermal conversion process that transforms solid biomass into a versatile synthetic gas (syngas)—a mixture primarily of carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and methane—by reacting the feedstock at high temperatures (typically 800-1200°C) with a controlled amount of oxygen and/or steam [22]. The resulting syngas can be purified and used in internal combustion engines, gas turbines, or fuel cells for power generation. This technology offers higher efficiency potential and lower emissions compared to direct combustion. A standard experimental workflow for gasification includes feedstock preparation (drying and sizing), proximate and ultimate analysis of the feedstock, bench-scale gasifier trials to determine optimal temperature and equivalence ratios, and syngas characterization using gas chromatography.

Anaerobic Digestion

Anaerobic Digestion (AD) is a biological process where microorganisms break down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen. It is particularly suitable for wet organic materials like animal manure, sewage sludge, and food waste. The process produces biogas (rich in methane) that can be used for power and heat generation in CHP units, along with a nutrient-rich digestate that can be used as fertilizer. The core experimental protocol for AD involves substrate characterization (e.g., chemical oxygen demand, carbon-to-nitrogen ratio), inoculum acclimation, continuous or batch-mode digester operation under mesophilic (35-37°C) or thermophilic (55-60°C) conditions, and continuous monitoring of biogas yield and composition.

The logical relationship and workflow between these primary conversion pathways and their outputs can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Biomass Conversion Pathways to Power.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For scientists and engineers developing and optimizing biomass power technologies, a specific toolkit of research reagents, analytical solutions, and essential materials is required. The table below details key solutions and their functions in experimental and operational contexts.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biomass Power Development

| Research Reagent / Material | Function & Application in Biomass Research |

|---|---|

| Solid Biofuel Feedstocks (Wood Chips, Pellets, Agricultural Residues) | Primary fuel source for combustion and gasification; studied for calorific value, ash content, and combustion characteristics. |

| Liquid Biofuels | Used in engine testing, fuel quality analysis, and as a reference for bio-crude oil from pyrolysis. |

| Biogas & Synthetic Gas (Syngas) Mixtures | Calibration standard for gas analyzers; used in engine and turbine performance testing for gasification and anaerobic digestion. |

| Anaerobic Digestion Inoculum | Specialized microbial culture to initiate and accelerate the anaerobic digestion process in laboratory-scale reactors. |

| Gas Chromatography (GC) Systems | Essential for precise quantification of syngas (H₂, CO, CH₄, CO₂) and biogas (CH₄, CO₂) composition. |

| Calorimeters (Bomb, Isoperibol) | Determine the Higher Heating Value (HHV) and Lower Heating Value (LHV) of solid, liquid, and gaseous biomass fuels. |

| Elemental Analyzers | Measure carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen content in feedstocks and residues (e.g., chars, ashes). |

| Thermogravimetric Analyzers (TGA) | Analyze thermal decomposition behavior, combustion kinetics, and ash content of biomass samples under controlled temperatures. |

Challenges and Opportunities in Biomass Power Development

Despite a promising growth trajectory, the biomass power sector faces significant challenges that require scientific and operational innovation. A primary restraint is the high capital cost of establishing new biomass power plants compared to conventional coal power facilities [25]. This includes substantial investment in logistics infrastructure for the collection, transportation, and storage of bulky and seasonally variable biomass feedstocks, which also contributes to price volatility [26] [24]. Furthermore, the sector faces increasing competition from other renewables like solar and wind, which accounted for approximately 92.5% of new global power capacity added in 2024 [24]. Regulatory uncertainty and the need to rigorously demonstrate sustainability and feedstock traceability present additional hurdles for project developers [24].

Conversely, these challenges are counterbalanced by robust opportunities. The retrofit and co-firing of existing fossil-fuel power plants presents a major strategic opportunity, enabling asset owners to leverage existing infrastructure while reducing carbon intensity. In 2023-2024, co-firing trials were present in approximately 18% of large-scale units globally [24]. The expanding adoption of waste-to-energy (WTE) technologies aligns with circular economy principles, addressing waste management crises while generating electricity [22]. Technological advancements in gasification, torrefaction, and the integration of Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) are steadily improving efficiency, fuel quality, and the potential for carbon-negative power generation [22]. Finally, the growth of decentralized biomass systems in rural and off-grid regions supports energy access initiatives, particularly in developing countries with abundant local biomass resources [22] [24].

From Feedstock to Fuel: A Practical Guide to Biomass Conversion Technologies and Applications