BECCS: The Promise and Challenges of Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage for a Net-Zero Future

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), a critical negative emissions technology.

BECCS: The Promise and Challenges of Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage for a Net-Zero Future

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), a critical negative emissions technology. It explores the foundational science behind BECCS, detailing its processes and theoretical potential to achieve net-negative emissions. The review covers the methodological spectrum of BECCS technologies—from post-combustion to oxy-fuel capture—and their application across industries like power generation and bioethanol production, illustrated by real-world projects in Stockholm and Illinois. A critical troubleshooting section addresses significant sustainability challenges, including land-use conflicts, carbon accounting complexities, and impacts on biodiversity. Finally, the article offers a validation of BECCS by comparing it with alternative carbon dioxide removal (CDR) strategies and assessing its projected role in meeting international climate targets, providing researchers and scientists with a balanced perspective on its viability and integration into climate mitigation portfolios.

Understanding BECCS: The Science and Theory of Negative Emissions

Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) represents a pivotal technological approach within climate change mitigation portfolios, transforming carbon-neutral bioenergy into a carbon-negative system capable of actively removing atmospheric CO₂. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical analysis of BECCS fundamentals, system components, and methodological frameworks for assessment. By integrating the latest research findings and quantitative data, we examine BECCS implementation pathways, technical requirements, and economic viability. The analysis underscores BECCS's dual role in delivering renewable energy while generating net-negative emissions, positioning it as an essential component for achieving long-term climate targets as outlined by the IPCC. For researchers and scientists engaged in climate solution development, this work offers both foundational knowledge and advanced technical guidance for evaluating BECCS systems within integrated decarbonization strategies.

Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) is an integrated climate mitigation technology that combines bioenergy production from biomass with carbon capture and storage processes. The fundamental innovation of BECCS lies in its capacity to generate net-negative carbon emissions—removing more CO₂ from the atmosphere than it releases—when implemented with sustainable biomass sourcing and permanent geological storage [1] [2]. This transformative potential positions BECCS as a critical technology for achieving the temperature goals established in the Paris Agreement, particularly for offsetting residual emissions from hard-to-abate sectors like aviation and heavy industry [3].

The core principle enabling BECCS's negative emissions capability resides in the natural carbon cycle of biomass. During growth, biomass feedstocks photosynthetically absorb atmospheric CO₂, creating a temporary carbon sink. When this biomass is converted to energy, the carbon is released but can be captured before reaching the atmosphere through various technological means. The captured carbon is then permanently sequestered in geological formations, effectively creating a one-way transfer of carbon from the atmosphere to underground storage [1] [4]. This process differentiates BECCS from fossil-based CCS, which merely reduces additional carbon emissions but does not provide atmospheric carbon drawdown.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has identified BECCS as a key component in most climate mitigation pathways limiting warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Modeled scenarios that limit warming to 1.5°C with no or limited overshoot typically require cumulative BECCS deployment removing 30-780 gigatonnes of CO₂ globally between 2020-2100 [5]. This substantial range reflects uncertainties in future policy environments, technological advancement rates, and sustainable biomass availability. Current deployment remains limited, with fewer than 20 facilities in planning phases globally and less than 2 million tonnes of CO₂ removed annually—far below the scale required to meet climate targets [5].

Technical Components of BECCS Systems

Biomass Feedstock Production and Specification

The foundation of any BECCS system lies in its biomass feedstock, which determines both the technical design parameters and overall carbon balance. Biomass sources for BECCS applications fall into three primary categories, each with distinct characteristics and sustainability considerations, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Biomass Feedstock Classification for BECCS Applications

| Feedstock Category | Examples | Carbon Intensity | Technical Considerations | Sustainability Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dedicated Energy Crops | Miscanthus, switchgrass, short-rotation forestry | Low to Moderate | High yield potential; consistent quality | Land-use competition; water requirements; biodiversity impacts |

| Agricultural Residues | Straw, corn stover, rice husks | Very Low | Dispersed availability; collection logistics | Soil health maintenance; nutrient cycling |

| Forestry Residues | Thinnings, bark, sawdust, wood chips | Low | Established supply chains; heterogeneous composition | Sustainable harvest rates; forest ecosystem integrity |

| Organic Waste Streams | Municipal solid waste, food processing waste, algae | Variable | Contaminant removal; preprocessing requirements | Waste management synergies; emission avoidance |

Sustainable biomass sourcing represents a critical determinant of BECCS's net carbon negativity. Lifecycle assessments must account for direct and indirect land-use changes, as converting natural forests or grasslands to energy crop plantations can release stored terrestrial carbon, potentially negating the carbon removal benefits of BECCS [6] [2]. Additionally, sustainable practices must address biodiversity impacts, water resource management, and soil health preservation. Responsible sourcing decisions should be science-based and ensure that forests continue to grow and maintain or increase their carbon storage capacity over time [1].

Energy Conversion Technologies

Biomass conversion processes transform raw feedstock into usable energy forms (electricity, heat, or biofuels) while producing a concentrated CO₂ stream amenable to capture. The selection of conversion technology significantly influences overall system efficiency, capture readiness, and economic viability, with the primary options characterized in Table 2.

Table 2: Energy Conversion Technologies for BECCS Applications

| Conversion Technology | Process Description | Energy Outputs | TRL | Carbon Capture Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combustion | Direct burning of biomass in boilers or furnaces to produce high-pressure steam | Electricity, heat | 9 (Mature) | Post-combustion capture; oxy-fuel combustion |

| Gasification | Thermal conversion of biomass to synthetic gas (syngas) at high temperatures with limited oxygen | Electricity, biofuels, chemical feedstocks | 7-8 (Demonstration) | Pre-combustion capture |

| Pyrolysis | Thermal decomposition in absence of oxygen to produce bio-oil, biochar, and syngas | Bio-oil, biofuels, biochar | 6-7 (Pilot/Demo) | Post-combustion capture from flue gases |

| Anaerobic Digestion | Biological breakdown of wet biomass by microorganisms in oxygen-free environment | Biogas (methane), heat | 9 (Mature) | Post-combustion capture |

Combustion-based systems represent the most mature conversion pathway, with applications ranging from combined heat and power (CHP) facilities to utility-scale power generation. Modern biomass power plants can achieve electrical efficiencies of 30-40% for dedicated biomass facilities, with CHP configurations reaching overall efficiencies of 80-90% through thermal energy utilization [7]. Gasification and pyrolysis technologies offer potential efficiency advantages and product flexibility but face greater technological and economic barriers to commercial deployment at scale. The integration of carbon capture systems typically reduces net electrical efficiency by 7-12 percentage points due to energy requirements for capture processes, though configuration optimization can mitigate these penalties [7].

Carbon Capture Methodologies

Carbon capture technologies for BECCS applications separate CO₂ from process gas streams, creating a concentrated product suitable for transport and storage. The dominant capture approaches include post-combustion, pre-combustion, and oxy-fuel combustion systems, each with distinct operational principles and technical considerations.

Post-combustion capture represents the most readily deployable option for existing bioenergy facilities, as it can be retrofitted to conventional combustion systems. This approach employs chemical solvents, typically amine-based compounds, to selectively absorb CO₂ from flue gases after combustion. The solvent is subsequently regenerated through heating, releasing a high-purity CO₂ stream while the solvent is recycled [1] [2]. Current amine-based systems can achieve 85-95% capture rates with CO₂ purity exceeding 99% [7]. The primary technical challenge involves the significant energy penalty for solvent regeneration, which typically consumes 15-30% of a plant's energy output.

Pre-combustion capture operates upstream of the energy conversion process, typically following biomass gasification. The resulting syngas (primarily CO and H₂) undergoes a water-gas shift reaction to convert CO to CO₂, which is then separated using physical solvents or adsorbents at elevated pressures [2]. This approach generally offers higher capture efficiencies and lower energy penalties compared to post-combustion systems but requires more complex and capital-intensive integrated gasification combined cycle (IGCC) infrastructure.

Oxy-fuel combustion utilizes nearly pure oxygen instead of air for biomass combustion, producing a flue gas consisting primarily of CO₂ and water vapor, which simplifies subsequent separation. This approach requires an air separation unit to produce oxygen, introducing significant energy demands and capital costs [2]. While offering theoretical advantages in capture efficiency, oxy-fuel systems remain at earlier stages of commercial development for biomass applications.

Carbon Transport and Geological Storage

Captured CO₂ must be transported to suitable geological formations for permanent sequestration. Transportation typically occurs via pipeline in a dense-phase supercritical state, optimizing volume efficiency and flow characteristics [1]. For regional BECCS deployment, transport infrastructure development represents a significant logistical and economic consideration, often requiring coordinated development of CO₂ pipeline networks.

Geological storage involves injecting CO₂ into deep subsurface formations at depths typically exceeding 800 meters, where conditions maintain CO₂ in a supercritical state with high density. Suitable geological formations include depleted oil and gas reservoirs, unmineable coal seams, and deep saline aquifers—porous rock formations saturated with saltwater [1] [2]. The United Kingdom alone possesses an estimated 70 billion tonnes of potential CO₂ storage capacity, far exceeding anticipated domestic requirements [1].

Multiple trapping mechanisms ensure long-term storage security. Initially, structural trapping occurs when impermeable caprock (such as shale or clay) forms a physical barrier preventing upward CO₂ migration. Over time, residual trapping immobilizes CO₂ within pore spaces by capillary forces, while solubility trapping dissolves CO₂ into formation waters. On millennial timescales, mineral trapping progressively converts dissolved CO₂ into stable carbonate minerals through geochemical reactions with host rocks [3]. Current scientific consensus indicates that appropriately selected and managed geological reservoirs can permanently isolate >99% of injected CO₂ over millennium timescales [5].

BECCS Process Flow and System Integration

The integration of BECCS components into a coherent system enables the transformation of carbon-neutral bioenergy into a carbon-negative technology. The logical progression from biomass cultivation to permanent carbon storage encompasses multiple stages that must be optimized collectively to maximize system performance and carbon removal efficiency.

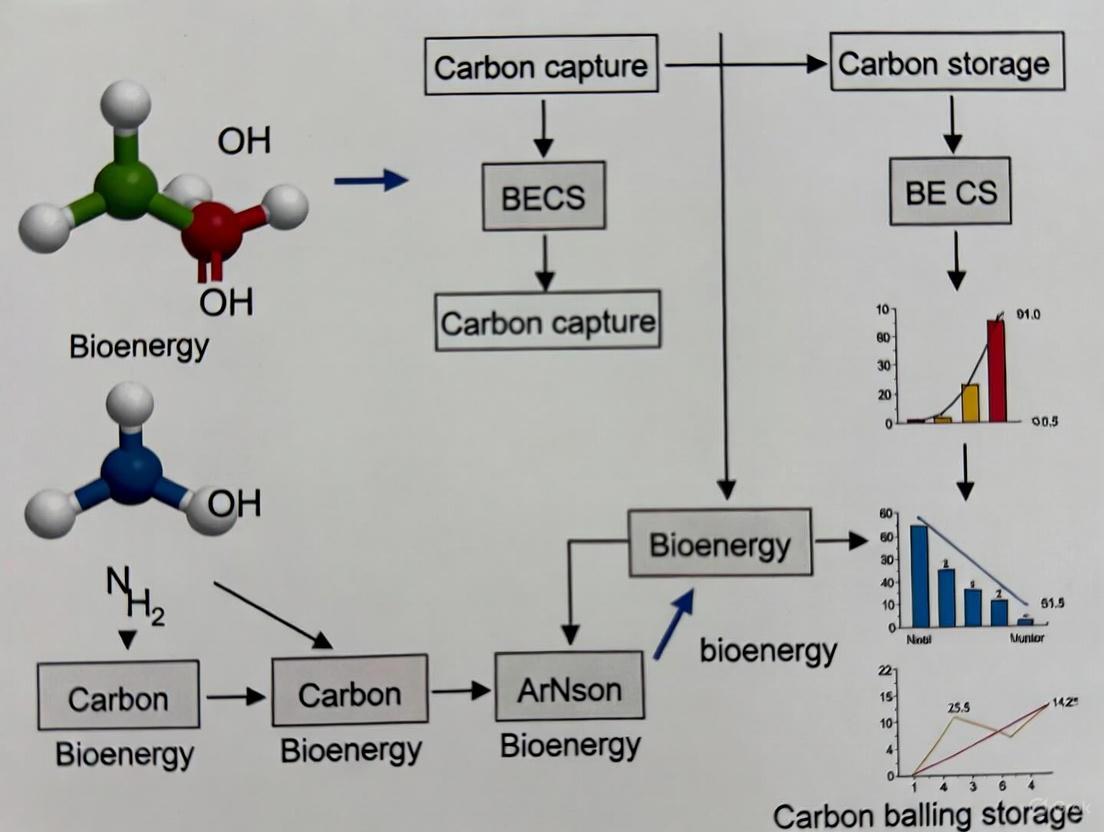

Diagram 1: BECCS System Integration and Carbon Flow. The process illustrates the transformation of atmospheric CO₂ into geologically stored carbon through integrated bioenergy and carbon capture systems.

The BECCS value chain begins with biomass production, where photosynthetic CO₂ absorption from the atmosphere establishes the foundation for negative emissions. Sustainable management of biomass resources is essential to maintain the carbon neutrality of this initial stage [2]. Following feedstock preparation and transport, energy conversion processes transform the chemical energy stored in biomass into usable energy carriers while releasing biogenic carbon in a form amenable to capture.

Carbon capture unit operation determines the fraction of process emissions diverted from the atmosphere, with modern systems typically capturing 85-95% of the carbon in biomass feedstocks [7]. The captured CO₂ undergoes compression and purification before pipeline transport to geological storage sites, where injection operations and monitoring programs ensure permanent sequestration. System-wide carbon accounting must address residual emissions across the value chain, including those from biomass cultivation, transport, and processing, to accurately quantify net carbon removal [6].

Experimental and Assessment Methodologies

Techno-Economic Assessment Framework

Techno-Economic Assessment (TEA) provides a systematic methodology for evaluating the financial viability and resource requirements of BECCS systems. Conventional TEA approaches typically demonstrate challenging economics for BECCS, with one study of a wheat-straw-fuelled CHP BECCS facility showing negative net present value (NPV = -$460 million) under standard financial assumptions [7]. This analysis revealed that carbon credit prices must exceed $240/tCO₂ for BECCS electricity to achieve cost parity with conventional renewable energy sources.

Emerging assessment frameworks incorporate broader societal benefits through Techno-Socio-Economic Assessment (TSEA), which monetizes indirect emission displacement and job creation through the social cost of carbon and opportunity cost of labor [7]. Applying this methodology to the same case study transformed the economic outlook, with the electricity-maximizing operational mode achieving a positive NPV of $2.28 billion. This dramatic shift underscores the importance of assessment methodology selection when evaluating BECCS projects.

Sensitivity analyses consistently identify carbon pricing, biomass feedstock costs, and capital investment requirements as the primary determinants of financial viability. The strong dependence on assumed social cost of carbon values highlights the policy-sensitive nature of BECCS economics and the need for compensation mechanisms that recognize the full societal value delivered by these systems [7].

Lifecycle Assessment Protocol

Robust lifecycle assessment (LCA) represents a critical methodology for quantifying the net climate impact of BECCS systems, requiring comprehensive accounting of all greenhouse gas flows across the value chain. The International Energy Agency's methodology provides guidance for key methodological choices, including reference land use, spatial and temporal system boundaries, co-product handling, and climate forcers considered [6].

Table 3: Critical Lifecycle Assessment Considerations for BECCS

| Assessment Element | Methodological Options | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Reference System | Alternative land use without bioenergy; conventional energy displacement | Select reference consistent with study objectives; account for indirect land use changes |

| System Boundaries | Cradle-to-gate; cradle-to-grave; spatial boundaries for land use impacts | Include all significant life cycle stages; ensure temporal consistency |

| Time Horizon | 20-year; 100-year; multi-decadal carbon debt analysis | Align with policy context; consider timing of emissions and removals |

| Co-product Handling | Mass allocation; economic allocation; system expansion | Apply consistent method; sensitivity analysis with different approaches |

| Climate Forcers | CO₂ only; multiple greenhouse gases with global warming potentials | Include all significant climate forcers; use latest characterization factors |

A critical LCA consideration involves the timing of carbon flows, as biomass growth occurs over years to decades while combustion and capture happen instantaneously. This temporal mismatch can create temporary carbon debts that must be accounted for in comprehensive assessments [6]. Additionally, indirect land-use change (iLUC) effects—where biomass cultivation displaces previous land uses to new locations—can introduce significant emissions not captured in direct process-based accounting. Advanced LCA methodologies incorporate iLUC factors based on economic modeling of agricultural and forestry market dynamics.

Research Reagent Solutions for BECCS Investigation

Experimental research on BECCS component technologies requires specialized materials and analytical approaches. The following reagent solutions represent essential methodologies for advancing BECCS development across multiple research domains.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for BECCS Development

| Research Domain | Reagent/Methodology | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Development | Amine-based solvents (e.g., MEA, MDEA, AMP) | CO₂ chemisorption in post-combustion capture; benchmark for novel solvent evaluation |

| Advanced Sorbents | Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs); porous polymer networks | Selective CO₂ adsorption with lower regeneration energy requirements |

| Biomass Characterization | Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA); proximate/ultimate analysis | Quantification of biomass composition; prediction of conversion behavior |

| Catalyst Systems | Zeolite catalysts; nickel-based reforming catalysts | Tar reforming in gasification; optimization of syngas composition |

| Monitoring Solutions | Stable carbon isotopes (¹³C); tracers (e.g., perfluorocarbons) | Verification of stored CO₂ origin; leakage detection in geological formations |

| Biomass Processing | Enzymatic hydrolysis cocktails; fermentation microorganisms | Biochemical conversion of lignocellulosic biomass to advanced biofuels |

Innovative solvent systems represent a particularly active research domain, with advanced amine blends, ionic liquids, and phase-change solvents demonstrating potential for reduced energy penalties compared to conventional monoethanolamine (MEA) benchmarks. Simultaneously, solid sorbents based on metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and porous carbon materials offer alternative capture pathways with distinct regeneration characteristics. For biological conversion pathways, specialized enzyme cocktails enable efficient deconstruction of recalcitrant lignocellulosic biomass into fermentable sugars, while engineered microorganisms expand the range of available biofuel products.

Economic Viability and Policy Frameworks

The economic competitiveness of BECCS remains challenged under conventional financial metrics, but evolving policy frameworks and comprehensive valuation approaches demonstrate improving viability. Current economic assessments highlight several interconnected factors influencing investment attractiveness.

Financial incentives significantly impact BECCS deployment economics. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act enhanced the Section 45Q tax credit to $85/tonne of CO₂ permanently stored, substantially improving project economics [8]. Similarly, the European Union's emissions trading system and innovation fund provide financial support mechanisms. However, analyses indicate that even enhanced credit levels may remain insufficient, with breakeven carbon prices estimated at $240/tCO₂ for certain BECCS configurations [7].

A holistic policy blueprint for responsible BECCS development encompasses eight key elements: national policy planning with BECCS targets; financial incentives beyond current tax credits; sustainable feedstock provisions in farm legislation; wildfire mitigation integration; rural community development; greenhouse gas accounting standards; environmental justice safeguards; and targeted innovation programs [8]. This comprehensive approach addresses both deployment barriers and sustainability concerns while maximizing socio-economic co-benefits.

The manufacturing and research sectors require specialized materials and analytical systems to advance BECCS technologies. High-performance solvent systems for carbon capture include advanced amine blends and ionic liquids that reduce regeneration energy requirements compared to conventional monoethanolamine. Solid sorbents based on metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) offer potential for lower energy penalties through pressure-swing adsorption cycles. For biomass conversion research, specialized enzyme cocktails enable efficient breakdown of lignocellulosic feedstocks, while catalyst systems optimize biofuel production pathways. Advanced monitoring solutions utilizing stable carbon isotopes (¹³C) provide verification of carbon storage integrity and origin.

BECCS represents a critical technological pathway for achieving climate stabilization targets, transforming carbon-neutral bioenergy into a carbon-negative system through integrated capture and geological storage. The technology's unique capacity to deliver both renewable energy and atmospheric carbon removal positions it as an essential component of comprehensive climate mitigation strategies, particularly for offsetting residual emissions from hard-to-abate sectors.

Significant challenges remain in scaling BECCS deployment to climate-relevant levels, including economic competitiveness, sustainable biomass availability, and infrastructure development. However, evolving policy frameworks, technological innovations, and comprehensive assessment methodologies that recognize BECCS's full societal value are progressively addressing these barriers. For researchers and scientific professionals, advancing BECCS implementation requires continued refinement of conversion efficiencies, capture technologies, and monitoring protocols while maintaining rigorous sustainability safeguards.

As global emissions reduction efforts intensify, BECCS stands ready to contribute to deep decarbonization pathways. With coordinated policy support, scientific innovation, and responsible deployment practices, BECCS can fulfill its potential as a scalable carbon dioxide removal technology, supporting transition to a net-negative carbon economy and climate stabilization.

The pursuit of climate change mitigation has catalyzed the development of advanced technologies designed to achieve net-negative carbon emissions. Among the most promising is Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), which integrates the natural carbon-sequestering power of photosynthesis with engineered geological storage to create a closed carbon loop. This whitepaper delineates the core principles of BECCS, detailing how biomass converts atmospheric CO₂ into usable energy while the resulting carbon emissions are captured and sequestered underground. We provide a technical analysis of the biological, industrial, and geological processes involved, supported by quantitative data, experimental methodologies, and visualizations of key pathways. The synthesis presented herein is intended to equip researchers and scientists with a comprehensive understanding of BECCS concepts, its potential, and its constraints within the broader climate solution portfolio.

The Earth's carbon cycle consists of two primary domains: the fast, or active, domain and the slow, or geologic, domain [9]. The fast domain involves the continuous exchange of carbon between the atmosphere, oceans, and biosphere—a cycle measured in years to centuries. In contrast, the geologic domain, where carbon is stored in rocks and fossil fuels, operates over tens to hundreds of thousands of years. The combustion of fossil fuels disrupts this natural balance by transferring vast quantities of geologic carbon into the atmosphere, leading to a net increase in atmospheric CO₂ concentrations [9].

Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) presents a framework for reversing this flow. It leverages the fast carbon cycle, wherein photosynthesis in biomass removes CO₂ from the atmosphere, and combines it with carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology to divert the carbon into long-term geologic storage. When managed effectively, this process can create a closed-loop system: carbon is cycled from the atmosphere to biomass, converted into energy, and the emissions are returned to the geologic domain from which fossil fuels were originally extracted [9]. The overall impact on atmospheric CO₂ levels depends on three factors: the extent of fossil fuel displacement, the effect of bioenergy systems on carbon storage in the fast domain, and the proportion of biogenic CO₂ that is captured and stored [9].

The Photosynthetic Engine: Biological Carbon Capture

The initial phase of the BECCS loop is biological carbon fixation via photosynthesis. Plants absorb atmospheric CO₂ and, using solar energy, convert it into organic biomass. The stoichiometric equation of photosynthesis and cellulose biosynthesis indicates that for every 44 grams of CO₂ fixed, approximately 27 grams of dry biomass are produced [10]. The natural global capacity for this process is immense, with estimates suggesting photosynthesis in forests fixes over 50 to 100 billion tonnes of CO₂ annually [10].

Enhancing Natural Photosynthesis

A major focus of contemporary research is improving the efficiency of this biological capture, as natural photosynthesis is constrained by processes like photorespiration that re-release CO₂ [11]. A breakthrough in synthetic biology, published in Science in September 2025, demonstrates a pathway to significantly higher efficiency. Researchers at Academia Sinica successfully engineered a synthetic carbon fixation cycle, the Malyl-CoA glycerate (McG) cycle, into the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana [11].

This novel cycle functions alongside the native Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle, creating a dual-cycle carbon fixation system that reduces carbon loss from photorespiration and lipid synthesis. The resulting "synthetic C2 plants" exhibited a 50% increase in carbon fixation efficiency, accelerated growth, and biomass increases of two to three times compared to wild-type plants [11]. This enhancement not only boosts the carbon input for BECCS but also offers co-benefits for food security and sustainable biofuel feedstocks.

Table 1: Quantitative Overview of Global Carbon Flows and Storage

| Parameter | Value | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Annual Global Industrial CO₂ Emissions (c. 2020) | 35 billion tonnes | [10] |

| Estimated Annual CO₂ Fixation by Forests | 50-100 billion tonnes | [10] |

| Global Prudent Geologic CO₂ Storage Limit | 1,460 Gt (1,290-2,710 Gt range) | Risk-based assessment [12] [13] |

| Reported Global Technical Storage Potential | 8,000-55,000 Gt | Older, less constrained estimates [13] |

| Maximum Potential Temperature Reduction from Full Geologic Storage Use | 0.7 °C (0.35–1.2 °C range) | Based on prudent storage limit [12] [13] |

Experimental Protocol: Engineering Synthetic Carbon Fixation

The following methodology summarizes the key experimental workflow used to create and validate the synthetic C2 plants, as detailed by Academia Sinica [11].

1. Cycle Design and In Vitro Testing:

- The Malyl-CoA glycerate (McG) cycle was designed in silico to metabolically bypass photorespiratory CO₂ release.

- The cycle was first constructed and tested in a bacterial model system to confirm its functionality and kinetic properties.

2. Plant Transformation and Generation:

- Genes encoding the key enzymes of the McG cycle were cloned into plant expression vectors.

- Arabidopsis thaliana was transformed using the floral dip method with Agrobacterium tumefaciens harboring the recombinant vectors.

- Transgenic plants were selected using antibiotic resistance, and homozygous lines (T3 generation) were established for phenotyping.

3. Physiological and Metabolic Phenotyping:

- Growth Analysis: Wild-type and transgenic plants were grown under controlled conditions. Biomass was measured as dry weight after 4-6 weeks of growth.

- Gas Exchange Measurements: Net photosynthetic rate and the rate of photorespiration were quantified using an infrared gas analyzer (IRGA) system.

- Metabolomic Profiling: Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) was used to profile intermediate metabolites of both the CBB and McG cycles, confirming the in vivo operation of the synthetic pathway.

- Lipid Analysis: Total lipids were extracted from plant tissues and quantified gravimetrically after solvent evaporation.

4. Validation and Microscopy:

- Electron Microscopy: Leaf ultrastructure was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to observe any morphological changes in chloroplasts or other organelles.

- Genetic Stability: The stability of the introduced traits was monitored over multiple generations.

The Engineering Bridge: From Biomass to Captured Carbon

Once biomass is produced, it can be processed in bioenergy facilities to generate electricity, heat, or liquid biofuels. The critical second step in BECCS is capturing the CO₂ released during this conversion process. Unlike fossil fuel emissions, which represent a net addition of carbon to the atmosphere, CO₂ from biomass combustion is biogenic—it is part of the active carbon cycle [9]. Capturing it effectively withdraws it from the active cycle.

Carbon capture technologies, typically employing amine-based solvents or other sorbents to separate CO₂ from the flue gas stream, are deployed at the bioenergy facility. The captured, high-purity CO₂ is then compressed for transport. Two primary configurations exist:

- Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS): The captured CO₂ is injected into deep geological formations for permanent isolation [9].

- Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Utilization (BECCU): The captured CO₂ is used as a feedstock for producing goods such as synthetic fuels or building materials, which delays its return to the atmosphere [9].

An alternative pathway involves producing biochar alongside bioenergy. When applied to soils, biochar sequesters carbon for decades to centuries while potentially improving soil health [9].

The Geological Anchor: Long-Term Carbon Storage

The final, anchoring component of the closed loop is the durable storage of captured CO₂. Suitable geological formations include depleted oil and gas reservoirs and deep saline aquifers, typically located 1 to 2.5 kilometers below the surface [12]. At these depths, high pressure and temperature maintain CO₂ in a supercritical state, increasing storage density and stability.

A pivotal 2025 study in Nature established a prudent planetary limit for geologic carbon storage of approximately 1,460 Gt of CO₂ (with a range of 1,290–2,710 Gt) [12] [13]. This risk-based, spatially explicit analysis excluded areas with high potential for seismic activity, those within a 25 km buffer of human settlements to mitigate leakage risks, sensitive environmental zones, and regions with policy restrictions on CCS [12]. This limit is drastically lower than previous technical estimates of 8,000–55,000 GtCO₂ [13], indicating that geologic storage is a valuable and finite resource. The study concluded that fully utilizing this prudent storage capacity could reduce global temperatures by a maximum of about 0.7 °C [13].

Table 2: Key Geological Formations for CO₂ Storage and Their Characteristics

| Formation Type | Key Characteristics | Considerations & Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Depleted Oil & Gas Reservoirs | Well-understood geology and sealing capacity; potential use of existing infrastructure. | Finite capacity linked to extracted resource volumes; potential for well-integrity issues. |

| Deep Saline Aquifers | Very large theoretical storage capacity; widespread global distribution. | Less characterized than hydrocarbon fields; requires careful site selection and monitoring. |

| Basalt Formations | CO₂ can react with minerals to form stable carbonates, offering potentially permanent fixation. | Technology is less mature; injection rates and long-term reaction kinetics are areas of active research. |

Integrated Pathways and System Trade-offs

The effectiveness of BECCS is not measured by its individual components but by their integration into a cohesive system that results in net atmospheric CO₂ removal. The following diagram illustrates the core closed-loop logic of the BECCS process.

However, the deployment of BECCS is not without significant trade-offs, primarily concerning land and resource use. Integrated assessment models reveal a clear inverse relationship between the scale of BECCS deployment and afforestation/reforestation (A/R) [14]. Large-scale cultivation of bioenergy crops can compete directly with land needed for food production or for natural forests that act as carbon sinks themselves. One analysis found that in a 2°C scenario with no specific land mitigation policy, BECCS could provide 540 GtCO₂ of removal, but the land use sector could become a net source of 230 GtCO₂ emissions. Conversely, with a strong land mitigation policy, BECCS removal was 360 GtCO₂, complemented by 150 GtCO₂ of removal from A/R [14]. This underscores the critical need for integrated policy that manages these trade-offs.

The Researcher's Toolkit

The following table details key reagents, materials, and tools essential for research in the fields of enhanced photosynthesis and BECCS.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Photosynthesis & BECCS Research

| Item/Category | Function/Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Transformation Vectors | Delivery of synthetic pathway genes into the plant genome. | pCAMBIA, pGreen series with tissue-specific promoters. |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | A biological vector for stable plant transformation. | Strain GV3101 for Arabidopsis transformation. |

| Gas Exchange System | Precise measurement of photosynthetic and photorespiratory rates. | Infrared Gas Analyzer (IRGA) systems (e.g., LI-COR 6800). |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Identification and quantification of metabolic intermediates. | Used for metabolomic profiling to validate synthetic cycle flux. |

| Amino-based Sorbents | Chemical capture of CO₂ from flue gas streams in lab-scale CCS. | Monoethanolamine (MEA) is a common benchmark solvent. |

| Geological Core Samples | Experimental analysis of CO₂-brine-rock interactions and injectivity. | Sandstone or basalt cores for laboratory sequestration experiments. |

| Stable Isotope ¹³CO₂ | Tracing the fate of fixed carbon through metabolic pathways and ecosystems. | Essential for validating the novel carbon flux in synthetic C2 plants. |

The core principle of BECCS—creating a closed carbon loop through the synergy of photosynthesis and geological storage—offers a scientifically-grounded pathway for achieving net-negative emissions. The system's efficacy is contingent upon continuous innovation across its constituent domains: enhancing the carbon fixation efficiency of biomass, optimizing carbon capture processes, and prudently managing the finite resource of geologic storage space. Recent advances in synthetic biology, such as the development of dual-cycle carbon fixation plants, demonstrate a significant potential to amplify the input to this loop [11]. Simultaneously, a more realistic and risk-aware understanding of geologic storage capacity underscores that it is a precious, limited resource that must be strategically allocated [12] [13]. For the research community, the path forward requires an integrated, interdisciplinary approach that addresses the critical technical and socio-ecological trade-offs, particularly around land use, to responsibly unlock the potential of BECCS within the global portfolio of climate solutions.

The Critical Role of BECCS in IPCC Climate Models and 1.5°C Scenarios

Most Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to project pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C rely heavily on Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) technologies [15] [16]. Among these, Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) represents a pivotal negative emission technology that combines bioenergy production with permanent geological carbon storage [17] [18]. BECCS is strategically important because it offers the dual capability of supplying energy while simultaneously removing CO₂ from the atmosphere, effectively creating a carbon-negative system [18]. When biomass grows, it absorbs atmospheric CO₂ through photosynthesis; when this biomass is converted to energy and the resulting emissions are captured and stored geologically, the net effect is a reduction in atmospheric carbon levels [17]. This technical brief examines the foundational role of BECCS within climate mitigation scenarios, the quantitative demands placed upon it, the methodological frameworks for its assessment, and the critical research gaps that must be addressed to realize its potential.

BECCS in IPCC Climate Pathways: A Quantitative Analysis

Integration in Climate Categories

IPCC mitigation pathways are categorized based on their 21st-century warming outcomes, with BECCS deployment varying significantly across these categories [15]. The table below summarizes key characteristics of these climate categories and the role of CDR, establishing the context for BECCS demand.

Table 1: IPCC Climate Pathway Categories and Carbon Dioxide Removal Context

| Category | Description | 2100 Warming (°C) | Net-Zero CO₂ Year (Median) | Cumulative Net-Negative Emissions (GtCO₂, Median) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Below 1.5°C with no or limited overshoot | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.5) | 2050-2055 | -220 |

| C2 | Below 1.5°C with high overshoot | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.5) | 2055-2060 | -360 |

| C3 | Likely below 2°C | 1.6 (1.5 to 1.8) | 2070-2075 | -40 |

| C4 | Below 2°C | 1.8 (1.5 to 2.0) | 2080-2085 | -30 |

Scenarios that limit warming to 1.5°C, particularly those with high overshoot (C2), involve substantial cumulative net-negative emissions over the 21st century, achieved primarily through CDR technologies like BECCS [15]. These pathways require net-zero CO₂ emissions to be achieved by the early 2050s, creating a narrow window for deployment.

Projected Deployment Scale and Feasibility Constraints

The scale of BECCS envisioned in many IPCC pathways presents significant feasibility challenges, as analyzed against historical technology deployment rates [19].

Table 2: BECCS Deployment Scale and Feasibility Analysis

| Metric | IPCC 1.5°C Pathways (Median) | Current Deployment (2024) | Feasibility Constraints from Historical Analogues |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual CDR by 2030 | 0.9 GtCO₂ (IQR 0.4-1.5) | ~0.002 GtCO₂ [17] | Upper feasible bound for all CCS (including BECCS): 0.37 GtCO₂/yr [19] |

| Global Removal Potential by 2050 | 0.5 to 5.0 GtCO₂ per year [17] | ||

| Cumulative CO₂ Captured by 2100 | Up to 700 GtCO₂ by 2070; 1,400 GtCO₂ by 2100 in some pathways [19] | Only 10% of IPCC pathways meet tri-phase feasibility constraints, depicting <600 GtCO₂ by 2100 [19] |

A 2024 feasibility study found that only 10% of mitigation pathways (IPCC categories C1-C4) depict CCS (including BECCS) capacity growth compatible with optimistic assumptions, requiring plans to double by 2025 with failure rates cut by half, followed by accelerated growth [19]. This highlights a significant feasibility gap between modelled pathways and practical deployment potential.

Technical Workflow and System Components of BECCS

End-to-End BECCS Process Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the complete technical workflow for BECCS, from biomass growth to carbon storage, highlighting the integration points for research reagent solutions.

Diagram 1: BECCS Technical Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Research and development of BECCS technologies requires specialized materials and analytical tools. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in experimental BECCS research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for BECCS Investigation

| Research Reagent/Material | Technical Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Feedstock Samples | Variable carbon content, growth rate, and chemical composition for process optimization | Feedstock selection studies; determining optimal biomass characteristics for different conversion pathways |

| Chemical Solvents (e.g., Amines) | Selective absorption of CO₂ from flue gas streams in post-combustion capture | Capture efficiency testing; solvent degradation and regeneration cycle analysis |

| Solid Sorbents | Physical or chemical adsorption of CO₂; often metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) or zeolites | Development of lower-energy capture systems; capacity and longevity testing |

| Catalysts | Accelerate specific biochemical or thermochemical reactions during conversion | Gasification process optimization; biofuel synthesis; tar reforming |

| Tracers (e.g., perfluorocarbons, isotopic labels) | Monitor and verify the movement and containment of stored CO₂ | Geophysical monitoring at storage sites; detection of potential leakage |

| Culture Media for Microbial Consortia | Support growth of engineered microorganisms for enhanced fermentation processes | Bioethanol production optimization; conversion yield improvement |

Methodological Framework for BECCS Research and Assessment

Experimental Protocol for BECCS Lifecycle Assessment

A robust Lifecycle Assessment (LCA) is fundamental to validating the carbon negativity of BECCS systems. The following protocol provides a standardized methodology:

System Boundary Definition: Establish a cradle-to-grave boundary encompassing biomass cultivation (including land-use change emissions), feedstock transport, energy conversion, CO₂ capture, transport, and permanent geological storage [16].

Data Inventory Collection:

- Biomass Production: Quantify inputs (fertilizers, water, energy) and direct emissions from agricultural operations.

- Conversion Process: Measure energy output and capture efficiency of the CO₂ capture technology.

- Carbon Transport & Storage: Account for energy use for compression, pipeline transport, and injection.

Carbon Balance Calculation: Calculate the net carbon removal using the formula: Net CO₂ Removal = (Biogenic CO₂ Captured and Stored) - (Lifecycle Emissions from Supply Chain). A system is carbon-negative only when the result is positive.

Spatially Explicit Modeling: Implement high-resolution spatial analysis to account for regional variations in biomass yield, soil carbon, transportation networks, and proximity to suitable storage sites, which are critical for accurate capacity estimates [16].

Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis: Perform Monte Carlo simulations to assess the impact of key variables (e.g., biomass yield, capture rate, transport distance) on the net carbon balance.

Integrated Assessment Modeling Logic

The following diagram outlines the logical structure for integrating BECCS into IAMs to project climate pathways, highlighting critical data inputs and feedback loops.

Diagram 2: IAM Integration Logic

Critical Challenges and Research Frontiers

Despite its projected importance, the large-scale deployment of BECCS faces significant challenges that constitute active research frontiers:

Sustainability of Biomass Supply: The potential competition for land between energy crops and food production poses risks to food security and can induce indirect land-use change (ILUC) that may release large quantities of stored carbon [20] [16]. Research focuses on sustainable residue use and regenerative agriculture.

Techno-Economic Uncertainty: Current models show high uncertainty in estimating BECCS costs, with projections often failing to fully account for biomass and CO₂ transportation logistics and complete lifecycle emissions [16].

Geological Storage Capacity and Infrastructure: The feasibility of BECCS is contingent upon the availability of suitable geological formations and the development of extensive CO₂ transport infrastructure [19] [16]. This requires significant investment and social license.

Feasibility-Implementation Gap: Analysis indicates that over 90% of IPCC 1.5°C pathways depict CCS (including BECCS) growth that exceeds even optimistic historical analogues for technology deployment, suggesting a significant feasibility gap between modelled pathways and real-world implementation potential [19].

BECCS occupies a critical, though contentious, position in the portfolio of climate mitigation strategies assessed by the IPCC. It is a key technology enabling pathways that limit warming to 1.5°C, particularly those that temporarily overshoot this target [15] [16]. However, the scale of deployment envisioned in many IAMs presents profound technical, economic, and sustainability challenges [19] [16]. Closing the gap between the modelled demand for BECCS and its feasible potential requires concerted innovation in biomass supply chains, carbon capture efficiency, transport infrastructure, and robust policy frameworks. For the research community, priorities include refining spatially explicit lifecycle assessments, reducing cost uncertainties, and developing sustainable biomass management protocols to ensure that BECCS can fulfill its theorized role as a cornerstone of deep decarbonization without incurring unacceptable environmental or social costs.

Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) represents a critical technological pathway for achieving gigatonne-scale carbon dioxide removal (CDR), playing an indispensable role in global climate mitigation strategies. As a negative emissions technology, BECCS combines sustainable bioenergy production with carbon capture and storage processes to permanently remove atmospheric CO₂ while simultaneously generating usable energy [7] [17]. The integrated system operates through a fundamental natural-technological synergy: biomass feedstocks absorb CO₂ from the atmosphere through photosynthesis during growth, and this carbon is subsequently captured during energy conversion processes before being stored securely in geological formations [17] [21]. This creates a closed-loop carbon cycle that results in net-negative emissions when implemented effectively [17].

The technology's dual capacity to deliver renewable energy provision and atmospheric carbon drawdown makes it particularly valuable for decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors such as heavy industry, long-distance transportation, and aviation, where direct electrification remains technologically challenging or economically prohibitive [22]. Current applications span multiple industries including bioenergy production, bioethanol processing, waste-to-energy facilities, and pulp and paper manufacturing [17]. Within climate modeling scenarios aiming to limit global warming to 1.5-2°C above pre-industrial levels, BECCS features prominently as the most promising carbon dioxide removal technology for counterbalancing residual emissions from sectors where complete decarbonization is technically unfeasible [23]. Its capacity to provide firm, dispatchable power further enhances grid stability alongside variable renewable sources like solar and wind [23].

Global Carbon Removal Potential: Quantitative Assessment

The carbon removal potential of BECCS operates at a scale that justifies its central position in climate mitigation pathways. Current global deployment remains at approximately 2 megatonnes of CO₂ removal per year according to International Energy Agency data [17]. However, projections indicate significant scalability, with estimates suggesting BECCS could remove between 0.5 to 5 gigatonnes of CO₂ annually by 2050 [17]. This represents a potential thousand-fold increase in deployment capacity over the next quarter-century, positioning BECCS as a cornerstone technology for achieving net-negative emissions in the second half of the 21st century.

Table 1: Global Carbon Removal Potential of BECCS

| Metric | Current Deployment | 2050 Potential | Key Determinants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Removal Capacity | 2 MtCO₂/year [17] | 0.5-5 GtCO₂/year [17] | Policy support, biomass sustainability, infrastructure development |

| Cumulative Potential (2100) | - | <600 GtCO₂ (feasible constraint) [19] | Growth rates, failure rates of planned projects |

| Market Position | Leading durable CDR method by volume sold (2024) [17] | 60% of total CDR credits transacted to date [24] | Corporate procurement, carbon credit pricing |

The feasibility of reaching BECCS's upper potential range depends critically on overcoming current deployment barriers. Historical analysis of technology analogies suggests that for CCS technologies overall, only 10% of climate mitigation pathways depict growth compatible with optimistic assumptions [19]. To remain on-track for 2°C climate targets, CCS (including BECCS) would need to accelerate at least as fast as wind power did in the 2000s during 2030-2040, and then grow faster than nuclear power did in the 1970s-1980s after 2040 [19]. Under these feasibility constraints, virtually all compatible pathways depict less than 600 GtCO₂ captured and stored by 2100 across all CCS technologies, with BECCS expected to constitute a substantial portion given its negative emissions potential [19].

Technical Methodology: BECCS Implementation Framework

Core Technological Process

The BECCS technological chain comprises four integrated subsystems that transform biomass into energy while delivering permanent carbon sequestration:

Biomass Production and Sourcing: Biomass feedstocks absorb atmospheric CO₂ through photosynthesis during growth, creating a biogenic carbon reservoir. Sustainable sourcing is critical and includes agricultural residues (rice straw, sugarcane waste), energy crops (fast-growing tree species like willows), algae, and municipal solid waste [22].

Bioenergy Conversion with Carbon Capture: Biomass undergoes thermochemical (combustion, gasification) or biochemical (fermentation, anaerobic digestion) conversion to produce energy in the form of electricity, heat, or biofuels. Point-source carbon capture technologies intercept CO₂ emissions before atmospheric release. Capture rates can reach 90% of contained carbon, as demonstrated by the Stockholm Exergi project [21].

Carbon Transportation and Compression: Captured CO₂ is purified, compressed into a dense supercritical fluid, and transported via pipeline or ship to suitable geological storage sites. Shipping provides economically efficient transport alternatives for dispersed coastal facilities, as planned in Swedish BECCS projects [21].

Geological Sequestration: Compressed CO₂ is injected into deep geological formations (>800 meters underground) such as depleted oil and gas reservoirs or deep saline aquifers capped by impermeable rock layers. Over time, the CO₂ undergoes mineral trapping or structural immobilization, enabling permanent storage [17] [21].

Figure 1: BECCS Technical Process Flow - This diagram illustrates the integrated carbon removal and energy production pathway, from atmospheric CO₂ absorption to permanent geological sequestration.

Assessment Methodologies

Techno-Economic Assessment (TEA) Framework

Traditional Techno-Economic Assessments evaluate BECCS viability through standard financial metrics including Net Present Value, Levelized Cost of Electricity, and internal rate of return. Conventional TEA approaches typically show poor financial attractiveness for BECCS systems, with one case study revealing negative profitability (NPV = -$460 million) without accounting for broader societal benefits [7]. These analyses indicate that carbon credit prices must exceed $240/tCO₂ for BECCS electricity to reach cost parity with conventional renewable energy sources [7].

Techno-Socio-Economic Assessment (TSEA) Framework

The emerging TSEA framework addresses limitations of conventional TEAs by integrating and monetizing societal co-benefits through established economic valuation methods. Key integrated factors include:

- Indirect Emission Displacement: Monetized using the social cost of carbon to quantify avoided climate damages from fossil fuel replacement [7].

- Employment Creation: Valued through the opportunity cost of labour to quantify economic benefits from job generation across the biomass supply chain, conversion facilities, and carbon management infrastructure [7].

- Energy Security Enhancement: Qualitative assessment of diversification benefits and reduced price volatility exposure.

- Air Quality Improvements: Health cost avoidance from reduced conventional pollutant emissions.

Application of TSEA demonstrates dramatic improvements in BECCS viability, with one analysis showing a shift from negative NPV (-$460 million) under conventional TEA to strongly positive NPV ($2.28 billion) under TSEA for electricity-maximizing operational modes [7].

Economic Viability and Market Dynamics

BECCS economics have improved substantially through policy support mechanisms and emerging carbon markets, though significant variability exists across project configurations and regional contexts.

Table 2: BECCS Economic Indicators and Market Dynamics

| Economic Factor | Current Value/Range | Context & Determinants |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Credit Price | Average $387/tonne CDR credit [24] | Voluntary carbon market transactions, typically ~500,000 tonnes per deal |

| Policy Support (US 45Q) | $85/tonne tax credit [24] | Stackable with REC markets and CDR credits, unique US advantage |

| Capital Investment | €455 million (Stockholm Exergi project) [21] | Scale-dependent, higher for greenfield vs. retrofit applications |

| Subsidized LCOE | As low as -$57.82/MWh [24] | With stacked incentives (45Q, RECs, CDR credits) at plant level |

| EU Innovation Funding | €180 million (Stockholm Exergi project) [21] | Competitive allocation, covers ~40% of capital expenditure |

The voluntary carbon market has demonstrated particularly strong growth for BECCS, experiencing an 84% volume increase and 156% transaction growth year-over-year in 2024 [25]. BECCS currently dominates the engineered carbon removal segment, comprising 60% of total CDR credits transacted to date [24]. Corporate procurement led by technology firms has driven this expansion, with Microsoft executing the largest CDR purchase of all time at 6.75 million tons from a BECCS project [25]. The overall CDR market has experienced a remarkable 688% compound annual growth rate since 2019, reflecting accelerating corporate climate commitments and anticipated regulatory developments [24].

Economic analyses reveal that BECCS opportunities are particularly lucrative in the United States, where the 45Q tax credit can be stacked alongside renewable energy credits and carbon dioxide removal credits [24]. This policy configuration creates a capacity-weighted average benefit of $13.34/MWh across existing biomass power plants in the Lower 48 states, potentially facilitating CCS commercialization at scale [24]. Projected load growth driven by data center demand (3.7-4.4 GW by 2035) positions the Southeastern and MISO regions as particularly favorable for greenfield BECCS deployment [24].

Implementation Barriers and Sustainability Considerations

Despite promising economics under supportive policy environments, BECCS deployment faces significant implementation barriers spanning technical, environmental, and social dimensions.

Technical and Economic Challenges

High Capital and Operational Costs: Carbon capture infrastructure remains complex and energy-intensive, with estimated costs ranging from €86 to €172 per tonne of CO₂, making BECCS economically challenging without substantial public subsidies or carbon credit revenues [22].

Energy Penalty: CCS processes consume significant additional energy, though leading projects like Stockholm Exergi have reduced this to approximately 2% through integration with district heating networks that utilize excess heat [21].

Infrastructure Requirements: BECCS implementation requires integrated infrastructure spanning biomass supply chains, conversion facilities, and CO₂ transport networks to suitable geological storage sites [25].

Environmental and Social Considerations

Land Use Impacts: Meeting climate targets with BECCS could require land areas potentially up to twice the size of India for dedicated energy crops, creating competition with food production and elevating food security risks [22].

Biomass Sustainability: Emissions from land-use change, fertilizer application, harvesting, processing, and transportation must be accounted for in lifecycle assessments to ensure net-negative emissions [22]. Monoculture energy plantations can reduce ecosystem diversity and cause habitat destruction [22].

Community Engagement: Project development requires early and meaningful community engagement to ensure equitable benefit sharing and avoid land rights conflicts, particularly in vulnerable or marginalized communities [25] [22].

Permanence and Leakage Risks: Potential leakage from underground storage reservoirs, while rare, could pose public health risks or trigger seismic activity near injection sites [22].

Policy Framework and Future Development Pathways

Supportive policy environments emerge as critical enablers for BECCS deployment at climate-relevant scales. Multiple governance levels play complementary roles in creating favorable investment conditions and addressing implementation risks.

Current Policy Mechanisms

Carbon Pricing Instruments: Carbon credits averaging $387/tonne for BECCS projects provide essential revenue streams, though prices must exceed $240/tCO₂ for conventional renewable energy parity [7] [24].

Tax Incentives: The US 45Q tax credit of $85/tonne represents a particularly effective policy mechanism that can be stacked with additional revenue streams to dramatically improve project economics [24].

Direct Funding Programs: The EU Innovation Fund provides substantial capital grants, covering approximately 40% of the €455 million capital expenditure for the Stockholm Exergi project [21].

Regulatory Frameworks: The European Union's carbon removal and carbon farming regulation creates standardized accounting methodologies, while Verra's release of methodology VMD0059 specifically supports carbon accounting and verification for BECCS initiatives [22] [21].

Research and Development Priorities

Advancing BECCS to gigatonne-scale deployment requires strategic research investments across multiple technology domains:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Methodological Solutions

| Research Domain | Key Reagents/Solutions | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Characterization | Sustainable biomass certification standards | Traceability and verification of carbon-negative feedstocks |

| Capture Process Optimization | Non-toxic chemical absorbents (e.g., amine alternatives) | High-performance CO₂ capture with reduced environmental impact |

| Geological Storage Assessment | Advanced seismic monitoring technologies | Pre-injection site characterization and post-injection leakage monitoring |

| Lifecycle Analysis | Integrated sustainability assessment frameworks | Comprehensive carbon accounting across biomass and capture value chains |

| Policy Design | Techno-socio-economic assessment (TSEA) models | Monetization of societal co-benefits in project evaluation |

Future policy development must establish mechanisms that ensure stakeholders are fairly compensated for the broader social benefits delivered by BECCS, including indirect emission displacement and job creation [7]. Additionally, robust international coordination is needed to harmonize carbon accounting methodologies, particularly regarding the co-claimability of carbon removals between host countries (claiming against Nationally Determined Contributions) and corporate purchasers (claiming against corporate emissions footprints) [25].

BECCS stands at a critical inflection point, with demonstrated technical feasibility and improving economics but significant deployment barriers remaining. The technology's potential to deliver gigatonne-scale carbon removal by mid-century depends on strategic policy support, sustainable biomass sourcing, and continued technological innovation. Current market signals are increasingly positive, with BECCS dominating the engineered carbon removal segment and major corporate offtake agreements validating the technology pathway.

Future development should prioritize several key areas: advancing carbon capture efficiency while reducing costs, establishing robust sustainability certifications for biomass feedstocks, developing integrated infrastructure for CO₂ transport and storage, and implementing equitable benefit-sharing mechanisms for host communities. With comprehensive policy frameworks and strategic public-private partnerships, BECCS can fulfill its potential as a cornerstone technology in the global portfolio of climate solutions, enabling the achievement of net-negative emissions essential for climate stabilization.

In the face of escalating climate change, Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) has emerged as a critical technology for achieving global climate targets. Its prominence in climate models developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) underscores its potential role in offsetting residual emissions from hard-to-decarbonize sectors and removing historical carbon dioxide from the atmosphere [3]. For researchers and scientists engaged in climate intervention technologies, a precise understanding of three fundamental concepts is essential: biogenic CO₂, negative emissions, and Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs). This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these core concepts, framing them within the context of BECCS research and development to establish a common foundation for scientific discourse and innovation.

Core Terminology

Biogenic CO₂: Carbon Cycling within the Biosphere

Biogenic carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions originate from the combustion, decomposition, or processing of biologically based materials, as opposed to fossil fuels [26] [27]. This distinction is fundamental to assessing the climate impact of bioenergy systems.

- Origin and Cycle: Plants remove CO₂ from the atmosphere through photosynthesis, storing it as carbon. When this biomass is combusted for energy, the stored carbon is re-released as CO₂ [28] [27]. This process operates within the Earth's natural, or "fast," carbon cycle, where carbon circulates between the atmosphere, vegetation, and soils over relatively short timescales (years to centuries) [29] [28].

- Contrast with Fossil CO₂: The critical difference lies in the carbon's origin. Burning fossil fuels transfers carbon that was locked away in geologic reservoirs (the "slow" carbon cycle) for millions of years into the atmosphere, resulting in a net increase of carbon in the atmosphere-biosphere system. In contrast, biogenic CO₂ emissions simply recycle carbon that was already part of this active system [28].

- Accounting and Reporting: Leading frameworks like the Greenhouse Gas Protocol require organizations to report biogenic CO₂ emissions separately from scope 1 emissions [27]. This is because the net addition of CO₂ to the atmosphere from sustainable bioenergy is considered zero over the harvest-regrowth cycle, although the timing of sequestration and emission can create temporary carbon debts. Completing this picture requires separate reporting of biogenic flows to understand a company's true dependence on biomass and the sustainability of its feedstock sources [27].

Negative Emissions: Achieving Net Carbon Removal

Negative emissions, also referred to as carbon dioxide removal (CDR), are achieved when a process or technology results in the net removal of CO₂ from the atmosphere and its subsequent durable storage [29] [3].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental difference between carbon-neutral systems and a negative emissions system like BECCS.

The concept of negative emission technologies (NETs) represents a paradigm shift in climate mitigation, moving beyond merely reducing the rate of CO₂ emissions to actively decreasing the atmospheric CO₂ concentration [3]. BECCS achieves this by integrating the natural carbon cycle of biomass with technological carbon capture and storage. The biomass feedstock absorbs atmospheric CO₂ as it grows. When this biomass is converted to energy, the resulting biogenic CO₂ emissions are captured, transported, and injected into secure geologic formations for permanent storage, thereby creating a net flux of carbon out of the atmosphere [29].

Technology Readiness Levels (TRL): A Metric for Maturity

Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) are a systematic metric used to assess the maturity of a particular technology, from basic principles to proven operation. The scale ranges from 1 to 9, with 9 being the most mature [30] [31]. This framework enables consistent communication of technical maturity across different types of technology and among researchers, funding agencies, and policymakers.

Table 1: Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) Definitions

| TRL | Description (NASA) | Description (European Union) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Basic principles observed and reported | Basic principles observed |

| 2 | Technology concept and/or application formulated | Technology concept formulated |

| 3 | Analytical and experimental critical function and/or characteristic proof-of-concept | Experimental proof of concept |

| 4 | Component and/or breadboard validation in laboratory environment | Technology validated in lab |

| 5 | Component and/or breadboard validation in relevant environment | Technology validated in relevant environment |

| 6 | System/subsystem model or prototype demonstration in a relevant environment | Technology demonstrated in relevant environment |

| 7 | System prototype demonstration in a space environment | System prototype demonstration in operational environment |

| 8 | Actual system completed and "flight qualified" through test and demonstration | System complete and qualified |

| 9 | Actual system "flight proven" through successful mission operations | Actual system proven in operational environment |

The progression of a technology through these levels is not merely linear but involves complex development pathways. The following workflow visualizes the key stages and decision points in the technology maturation process.

Integrated Analysis within the BECCS Context

The Convergence of Concepts in BECCS

BECCS is the operational integration of biogenic CO₂ and negative emissions at a technological scale. It combines bioenergy production (which operates within the biogenic carbon cycle) with carbon capture and storage (a technological process) to create a system that can generate energy while removing CO₂ from the atmosphere [29]. The carbon negativity of the entire system is contingent upon sustainable biomass management; the biomass must regrow to re-absorb the CO₂ emitted during the process's supply chain, and the captured biogenic CO₂ must be permanently isolated from the atmosphere [29] [32].

TRL Assessment of BECCS and Competing NETs

The maturity of BECCS and other Negative Emission Technologies (NETs) varies significantly. A comparative assessment of their TRLs, scalability, and costs is essential for research prioritization and policy development.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Negative Emission Technologies (NETs)

| Technology | Estimated TRL | Scalability (GtCO₂/year) | Estimated Costs (USD/tCO₂) | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BECCS | 5-7 [33] [32] | 0.5 - 11 [32] | $40 - $400 [33] [32] | Land-use competition, sustainable biomass supply, high initial costs [32] |

| Direct Air Capture (DAC) | 5-6 [3] | Not specified | >$120 [33] | High energy demands, cost efficiency [3] |

| Afforestation/Reforestation | 9 (mature) | 0.5 - 10 [3] | Lower cost | Saturation, reversibility, land use [3] |

| Biochar | 5-6 [3] | 0.5 - 6 [3] | $15 - $120 [3] | Feedstock availability, application logistics [3] |

| Enhanced Weathering | 3-4 [3] | 2 - 4 [3] | $50 - $500 [3] | Mining energy, slow verification [3] |

BECCS is currently positioned at a TRL of 5-7, indicating it has been validated in a relevant environment and is at the stage of system prototype demonstration in an operational environment [33] [32]. Specifically, oxy-fuel combustion (OFC) configurations in fluidized bed systems have achieved CO₂ recovery rates of up to 96.24% in research settings [33]. There are an estimated 20 BECCS projects globally spanning various methods and fuels, confirming its progression beyond pure laboratory validation [33].

Experimental Protocols & Research Toolkit

Key Experimental Methodology: Oxy-Fuel Combustion for BECCS

Oxy-fuel combustion is a leading carbon capture pathway for BECCS. The following protocol details a methodology for investigating this process in a fluidized bed system, a common technology for biomass conversion [33].

Objective: To determine the CO₂ recovery rate and characterize pollutant emissions (NOₓ, SOₓ, particulate matter) from biomass combustion under oxy-fuel conditions.

Materials and Setup:

- Fluidized Bed Combustor: A laboratory-scale or pilot-scale fluidized bed reactor equipped with controlled feeding systems for biomass and sorbents (e.g., limestone for desulfurization).

- Gas Supply System: Precise control systems for oxygen (O₂), and a flue gas recirculation loop to create the oxy-fuel atmosphere (typically ~70% recirculated flue gas).

- Biomass Feedstock: Prepared and characterized biomass (e.g., waste residues from forestry, agriculture, or dedicated energy crops), pulverized to a consistent particle size.

- Analytical Instrumentation:

- Online Gas Analyzers: For continuous measurement of O₂, CO, CO₂, NOₓ, and SO₂ concentrations in the flue gas.

- Particulate Matter (PM) Sampling System: A cascade impactor or similar device to collect and size-fractionate PM (e.g., PM₁ and PM₁₀).

- Elemental Analysis: Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) or X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) for analyzing the elemental composition of fly ash and captured PM.

Procedure:

- System Pre-Test: Calibrate all gas analyzers and establish baseline operation with air combustion.

- Oxy-Fuel Transition: Initiate the oxy-fuel mode by introducing a mixture of high-purity oxygen (~30%) and recirculated flue gas (~70%) to the combustor, maintaining a stable temperature.

- Combustion and Data Acquisition:

- Conduct a series of tests with varying biomass feed rates and oxygen concentrations.

- Continuously monitor and record the concentrations of CO₂, CO, NOₓ, and SO₂ in the exhaust.

- Collect PM samples for subsequent mass and compositional analysis.

- Emission Control Strategies:

- Implement gas and oxygen staging to assess its impact on NOₓ reduction.

- Inject limestone (e.g., CaCO₃) as a sorbent to evaluate in-situ SOₓ capture efficiency.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the CO₂ recovery rate based on the concentration and volume of the captured flue gas stream.

- Correlate operational parameters (O₂ concentration, temperature) with the production of CO and other pollutants.

- Analyze the composition of PM and ash to understand the fate of alkali metals (K, Na), heavy metals, and other inorganics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Research and development in BECCS, particularly in optimizing combustion and capture processes, rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for BECCS Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Feedstocks (e.g., forestry residues, agricultural waste, energy crops) | The primary source of biogenic carbon; its composition dictates combustion behavior and flue gas profile. | Served as the fuel in fluidized bed combustion experiments; variability in composition (e.g., K, Cl, S content) is a key research variable [33]. |

| High-Purity Oxygen (O₂) | Creates the oxy-fuel combustion environment by replacing air, resulting in a flue gas rich in CO₂ and H₂O. | Used in the oxy-fuel combustion protocol to establish an atmosphere conducive to efficient CO₂ capture [33]. |

| Limestone (CaCO₃) | A sulfur sorbent used for in-situ desulfurization during combustion. | Injected into the fluidized bed to react with SO₂ and form solid calcium sulfate, reducing SOₓ emissions [33]. |

| Ammonium Chloride-Modified Biomass Char (NH₄Cl) | A sorbent for mercury (Hg) removal from flue gas. | Used in fixed-bed or injected sorbent systems to capture and immobilize volatile heavy metals like mercury, addressing a key pollutant [33]. |

| Gas Mixture Standards (e.g., calibrated CO₂, NO, SO₂ in N₂) | Calibration of online gas analyzers for accurate and quantitative gas concentration measurements. | Essential for the initial calibration and periodic validation of all gas analysis equipment in the experimental setup. |

The precise differentiation of biogenic CO₂ from fossil CO₂, a clear understanding of the mechanics behind negative emissions, and a rigorous application of the TRL scale are indispensable for advancing BECCS from a promising concept to a deployable climate solution. BECCS represents the synergistic combination of these three concepts: it leverages the biogenic carbon cycle, engineered to achieve net-negative emissions, and is currently at a maturity level where real-world demonstration and system integration are critical. As of 2025, significant challenges in scaling BECCS remain, particularly concerning sustainable biomass supply chains, economic viability, and the development of robust policy and financing frameworks to support its deployment [34] [32]. Future research must focus on optimizing the entire BECCS value chain—from sustainable biomass production and efficient gas separation to secure geological storage—while refining TRL assessments and life-cycle analyses to ensure that this technology can fulfill its potential role in achieving global climate targets.

BECCS in Practice: Technologies, Systems, and Real-World Deployment

Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) technologies are critical components in the global effort to mitigate climate change and achieve net-zero emissions. These technologies are particularly vital within the context of Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS), which offers the dual benefit of producing energy while generating negative emissions. For researchers and scientists working on BECCS concepts, understanding the fundamental capture pathways is essential for system integration and optimization. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of the three primary carbon capture approaches—post-combustion, pre-combustion, and oxy-fuel combustion—focusing on their operational principles, technological maturity, and application within BECCS frameworks. The growing importance of these technologies is reflected in market activity, with tech-based carbon removal credit retirements surging to 57,417 metric tons in September 2025, predominantly driven by BECCS projects which comprised 86% of this volume [35].

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and challenges of the three main carbon capture pathways:

| Parameter | Post-Combustion Capture | Pre-Combustion Capture | Oxy-Fuel Combustion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Process Description | Separates CO₂ from flue gases after fuel combustion [36] | Converts fuel to syngas (H₂ + CO) before combustion; CO₂ is separated after water-gas shift reaction [37] | Fuel combustion in pure oxygen instead of air, producing flue gas mainly of CO₂ and H₂O [38] |

| CO₂ Concentration | Dilute: 3-15% [36] [39] | High: 15-50% [37] | Very High: >80% (after water condensation) [38] |

| Operating Pressure | Low (near atmospheric) [39] | High [37] [39] | Low to Medium [38] |

| Primary Separation Methods | Chemical solvents (e.g., amines), adsorption, membranes [36] | Physical solvents (e.g., Selexol), sorbents, membranes [39] | Cryogenic air separation, chemical looping combustion [38] |

| Technology Readiness | High (commercially deployed) [36] | Medium to High (demonstrated at pilot scale) [37] | Medium (under development for power plants) [38] |

| Key Advantages | Retrofit potential to existing plants [36] | High efficiency due to higher CO₂ pressure/concentration [37] | High purity CO₂ stream; low NOx emissions [38] |