Anaerobic Digestion for Biogas Production: Microbial Insights, Process Optimization, and Future Bioenergy Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the anaerobic digestion (AD) process for biogas production, tailored for researchers and scientists in bioenergy and related fields.

Anaerobic Digestion for Biogas Production: Microbial Insights, Process Optimization, and Future Bioenergy Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the anaerobic digestion (AD) process for biogas production, tailored for researchers and scientists in bioenergy and related fields. It explores the foundational microbiology, detailing the complex microbial consortia and biochemical pathways involved. The review further examines methodological advances in process intensification, including co-digestion and pretreatment strategies, alongside practical troubleshooting for system stability. Finally, it validates process efficiency through microbial activity assessments and kinetic modeling, positioning AD within the broader context of renewable energy trends and policy frameworks to highlight its significant potential in the circular bioeconomy.

The Microbial Engine: Deconstructing the Biology and Biochemistry of Anaerobic Digestion

Anaerobic Digestion (AD) is a synergistic biological process wherein a consortium of microorganisms breaks down biodegradable material in the absence of oxygen, leading to the production of biogas, a renewable energy source primarily composed of methane and carbon dioxide [1]. This process is integral to sustainable waste management and renewable energy production, offering a pathway to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and valorize organic solid wastes [2] [3]. The biochemical transformation of complex organic matter into methane is achieved through four sequential and interdependent metabolic stages: hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis [1] [4]. Each stage is facilitated by distinct microbial communities and enzymatic activities, and their efficiency dictates the overall success of the biogas production process [2] [5]. These Application Notes provide a detailed experimental framework for researchers and scientists to investigate, monitor, and optimize these critical metabolic stages within a broader thesis on AD process optimization.

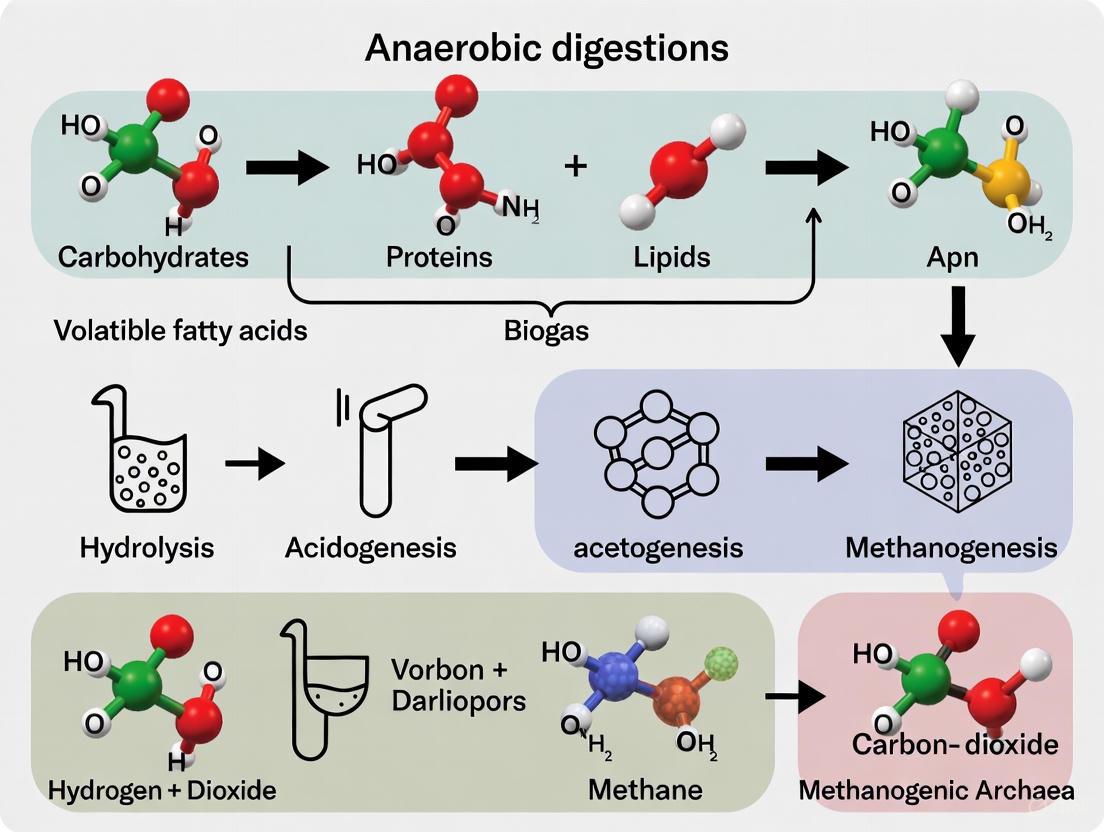

The AD process is a multi-stage biological reaction. The following diagram illustrates the sequential metabolic stages, key intermediates, and the microbial groups responsible for each transformation.

The entire process relies on syntrophy, a mutually dependent relationship where the products of one microbial group serve as substrates for the next [2]. Critical to this partnership is the maintenance of a low hydrogen partial pressure, which is thermodynamically regulated by hydrogen-consuming methanogens [2]. Electron transfer between syntrophic partners occurs via Interspecies Hydrogen Transfer (IHT) or more efficient Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer (DIET) [2]. The stability of the final methanogenesis stage is highly sensitive to environmental perturbations, such as pH shifts caused by volatile fatty acid accumulation [4].

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for investigating each metabolic stage, with a focus on quantitative analysis of key intermediates and microbial activity.

Protocol for Monitoring Hydrolysis Kinetics

Objective: To determine the hydrolysis rate constant of a specific organic solid waste (e.g., food waste, agricultural residue) by measuring the chemical oxygen demand (COD) solubilized over time.

Background: Hydrolysis is often the rate-limiting step for solid waste digestion, where complex polymers are broken into soluble monomers by extracellular enzymes [4]. Monitoring the release of soluble COD provides a direct measure of hydrolysis efficiency.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.2): For sample dilution and washing.

- Sodium Azide Solution (2% w/v): To inhibit biological activity for control samples.

- COD Digestion Reagents: Standard reagents for closed reflux colorimetric or titrimetric methods.

- Protease/Cellulase/Lipase Enzymes: For positive control experiments with enzymatic pre-treatment.

Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: The substrate is mechanically reduced to a particle size of 1-2 mm and homogenized.

- Experimental Setup: Set up batch reactors in triplicate with a working volume of 500 mL. Add 20 g of prepared substrate to 400 mL of anaerobic inoculum. Maintain mesophilic conditions (35 ± 2 °C) with continuous mixing at 100 rpm.

- Sampling: At time intervals (0, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24, 48 hours), withdraw 10 mL of slurry.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the sample at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4 °C.

- Filtration: Filter the supernatant through a 0.45 μm membrane filter.

- COD Analysis: Analyze the filtered supernatant for soluble COD using standard methods.

- Data Analysis: The hydrolysis rate is modeled using a first-order kinetic equation:

dS/dt = k_h * X, whereSis the concentration of solubilized COD,k_his the hydrolysis rate constant (day⁻¹), andXis the concentration of particulate COD.

Protocol for Profiling Acidogenesis and Acetogenesis Products

Objective: To quantify the dynamic profile of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) and other intermediates during acidogenesis and acetogenesis.

Background: Acidogenic bacteria ferment soluble monomers into VFAs, alcohols, and gases [6]. Acetogens then oxidize these products primarily to acetate, H₂, and CO₂ [2] [1]. The ratio and concentration of VFAs are critical indicators of process stability.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄, 2% v/v): For sample acidification prior to VFA analysis.

- Internal Standard Solution: 2-Ethylbutyric acid or 4-Methylvaleric acid in water.

- GC Calibration Standards: Certified VFA mix (C2-C6) in water at known concentrations.

- Carrier Gas: High-purity Helium or Hydrogen for GC operation.

Procedure:

- Reactor Operation: Operate a continuous stirred-tank reactor or a batch reactor with the feedstock of interest.

- Sampling: Collect liquid samples daily. Immediately centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes and filter through a 0.2 μm syringe filter.

- Sample Derivatization (if required): For some GC columns, acidify the sample and mix with an internal standard. No derivatization is needed for specialized columns (e.g., NUKOL).

- Gas Chromatography Analysis:

- Instrument: Gas Chromatograph equipped with a Flame Ionization Detector (FID).

- Column: Capillary column suitable for acid analysis (e.g., DB-FFAP, NUKOL).

- Oven Program: Ramp from 80°C to 200°C at 10°C/min.

- Injector/Detector Temperature: 250°C.

- Quantify acetate, propionate, butyrate, isobutyrate, valerate, and isovalerate concentrations against the calibration curve.

- Data Interpretation: Calculate the Acetate-to-Propionate ratio. A ratio below 1.5 or a propionate concentration above 1500 mg L⁻¹ may indicate potential inhibition [4].

Protocol for Investigating Methanogenesis Pathways

Objective: To differentiate between acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic methanogenic pathways and quantify their contribution to total methane yield.

Background: Methanogenesis is the terminal step where methanogenic archaea produce methane via two main pathways: acetoclastic (cleavage of acetate) and hydrogenotrophic (reduction of CO₂ with H₂) [2] [1]. Specific inhibitors can be used to delineate these pathways.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Sodium 2-Bromoethanesulfonate (BES, 20 mM): A specific inhibitor of methyl-CoM reductase, effectively blocking methanogenesis.

- Sodium Acetate Solution (1 M): Substrate for acetoclastic methanogens.

- H₂/CO₂ Gas Mix (80/20 v/v): Substrate for hydrogenotrophic methanogens.

- Anaerobic Basal Medium: A standard medium containing salts, vitamins, and trace elements, sparged with N₂/CO₂ to maintain anaerobiosis.

Procedure:

- Serum Bottle Preparation: In 120 mL serum bottles, add 50 mL of active anaerobic digester slurry. Create four sets in triplicate: (A) Control, (B) Acetate-Amended (20 mM), (C) H₂/CO₂-Amended (1 atm overpressure), (D) BES-Inhibited (10 mM).

- Incubation: Incubate bottles at 35°C on a shaker platform.

- Biogas Monitoring: Periodically measure biogas pressure and composition. Use a manometer for pressure and a gas chromatograph with a Thermal Conductivity Detector (TCD) to determine CH₄ and CO₂ percentages.

- Calculation: The methane yield from the acetate-amended bottles represents the activity of acetoclastic methanogens. The methane yield from the H₂/CO₂-amended bottles represents the hydrogenotrophic activity. The BES-inhibited set serves to confirm the specificity of methane production.

Data Presentation & Analysis

Table 1: Theoretical Methane Yield and Biodegradability of Common Feedstocks

Data adapted from Penn State EGEE 439 course materials and review literature [6] [4]. Yields are theoretical maximums under ideal conditions.

| Feedstock / Substrate | Elemental Formula | Theoretical Methane Yield (m³ CH₄/kg VS) | Relative Biodegradability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbohydrates | (CH₂O)ₙ | 0.37 | High |

| Proteins | C₁₀₆H₁₆₈O₃₄N₂₈S | 0.51 | Medium |

| Lipids / Fats | C₈H₁₅O | 1.00 | Very High |

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | C₅H₉O₂.₅NS₀.₀₂₅ | 0.48 | Low to Medium (rate-limited by hydrolysis) |

Table 2: Dominant Microbial Taxa and Key Functions in Anaerobic Digestion

Compiled from microbial community analyses using high-throughput sequencing [2] [5].

| Metabolic Stage | Key Microbial Groups (Phylum/Genus) | Primary Metabolic Function | Critical Inhibitors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi | Secretion of exoenzymes (cellulases, proteases, lipases) to solubilize complex polymers. | High lignin content, antibiotics (e.g., tetracycline) [3]. |

| Acidogenesis | Clostridium, Bacteroides, Eubacterium | Fermentation of monomers to VFAs, alcohols, H₂, and CO₂. | Low pH (<5.5), high sulfate levels. |

| Acetogenesis | Syntrophobacter, Syntrophomonas | Oxidation of VFAs and alcohols to acetate, H₂, and CO₂ (obligate syntrophs). | High H₂ partial pressure, ammonia. |

| Methanogenesis | Methanosaeta (acetoclastic), Methanosarcina (versatile), Methanobacterium (hydrogenotrophic) | Reduction of CO₂ (with H₂) or cleavage of acetate to produce CH₄. | Ammonia-N > 2000 mg/L, VFAs, BES, temperature shocks. |

The experimental workflow for a comprehensive analysis of the four stages, from setup to data interpretation, is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

This table details essential reagents, standards, and materials required for the experimental protocols outlined in this document.

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in AD Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium 2-Bromoethanesulfonate (BES) | Purity ≥ 95% | A specific inhibitor of methanogenesis; used to delineate methanogenic pathways and enrich non-methanogenic cultures. |

| Volatile Fatty Acid (VFA) Standard Mix | Certified reference material including C2-C6 acids (e.g., acetate, propionate, butyrate) | Calibration and quantification of acidogenesis and acetogenesis intermediates via Gas Chromatography. |

| Anaerobic Basal Medium | Standardized mix of minerals, vitamins, trace elements, and a reducing agent (e.g., Cysteine-HCl) | Provides essential nutrients for microbial growth while maintaining a strict anaerobic environment for culturing. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Substrates | ¹³C-Acetate, ¹³C-Bicarbonate, D₂O | Used in stable isotope probing (SIP) to trace carbon flow and identify active microbial populations in complex consortia. |

| DNA/RNA Extraction Kit | Optimized for complex environmental samples (e.g., sludge, manure) | Isolation of high-quality nucleic acids for downstream molecular analysis (qPCR, metagenomics, transcriptomics). |

| PCR Primers for Microbial Groups | e.g., Archaea 16S rRNA, bacterial functional genes (hydrolases) | Targeted amplification of specific microbial groups or genes to assess community structure and functional potential. |

| Granular Activated Carbon (GAC) | Particle size 0.5 - 2 mm | Used to facilitate Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer (DIET) by acting as a conductive material, potentially enhancing methanogenesis rates [2]. |

Anaerobic digestion (AD) is a microbial process that breaks down organic matter in the absence of oxygen, producing biogas primarily composed of methane (CH4) and carbon dioxide (CO2) [7]. The efficiency of this process is wholly dependent on complex, synergistic relationships within core microbial consortia, comprising specific bacterial phyla and archaeal methanogens [8] [9]. Understanding the composition and function of these core groups is paramount for optimizing biogas production and process stability in AD systems. This application note details the key microbial players, quantitative data on their abundance, standardized protocols for their identification, and the essential reagents required for research in this field.

Core Microbial Groups in Anaerobic Digestion

The core microbiome in AD systems consists of a consortium of bacteria responsible for hydrolysis, acidogenesis, and acetogenesis, and archaea that carry out the final step of methanogenesis [7]. The stability and performance of the digester are heavily influenced by the structure of this microbial community [8].

Table 1: Core Bacterial Phyla in Anaerobic Digestion Systems

| Phylum | Relative Abundance (%) | Primary Functional Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firmicutes | Highly Abundant | Hydrolysis, Fermentation, Syntrophic Acetate Oxidation | Often dominant; key in breaking down complex organics. |

| Bacteroidetes | Highly Abundant | Hydrolysis, Fermentation of proteins/ carbohydrates | |

| Chloroflexi | Abundant | Saccharolytic, syntrophic metabolism | Associated with decomposition of complex carbon [10]. |

| Proteobacteria | Variable | Diverse, including syntrophic metabolisms | Includes known hydrocarbon-degrading genera (e.g., Marinobacter) [11]. |

| Caldatribacteriota (JS1) | Present in specific environments | Metabolism of complex carbon | Found in consortia in energy-limited sediments like salt marshes [10]. |

| Planctomycetota | Present | Putative role in carbon cycling | Identified as part of core consortia in salt marsh sediments [10]. |

Table 2: Key Archaeal Methanogens in Anaerobic Digestion Systems

| Methanogen Order/Genus | Methanogenic Pathway | Preferred Conditions | Correlation with Biogas Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanobacteriales (e.g., Methanobacterium) | Hydrogenotrophic | Mesophilic to Thermophilic | Positively correlated; high explanatory power for production rates [8] [9]. |

| Methanobacteriales (e.g., Methanothermobacter) | Hydrogenotrophic | Thermophilic (55-70°C) | Dominant under high temperatures; crucial for ex-situ upgrading [9]. |

| Methanomassiliicoccus | Hydrogenotrophic | Mesophilic | Present in lab-scale upgrading systems [9]. |

| Methanomicrobiales | Hydrogenotrophic | Mesophilic to Thermophilic | Abundance correlated with biogas production performance (r=0.665) [8]. |

| Methanosarcinales (e.g., Methanosaeta) | Acetoclastic | Mesophilic | A persistently abundant and stable OTU in full-scale digesters [8]. |

The assembly and function of these core consortia are influenced by environmental parameters. Temperature is a crucial variable, significantly determining microbial community structures and causing a shift in dominant archaea from Methanobacterium to Methanothermobacter at higher temperatures [9]. The pH level also significantly interferes with the relative abundance of dominant archaea, with pH ~8.5 often being optimal for hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis [9]. Furthermore, syntrophic interactions are essential, particularly in energy-limited conditions, where the collective metabolic potential of core consortia enables the decomposition of complex carbon [10].

Quantitative Data on Microbial Abundance and Biogas Production

Quantitative data linking microbial abundance to system performance is critical for diagnostics and optimization.

Table 3: Quantitative Correlations Between Microbial Metrics and Biogas Production

| Metric | Finding | Statistical Significance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanogen Abundance vs. Genes | Relative abundances of methanogenic archaea and methanogenic genes are positively correlated. | r² = 0.530, P < 0.001 | [8] |

| Methanogen Variation vs. Biogas Production | Variations in methanogenic traits explain 55.7% of variation in biogas production rates. | Much higher than environmental parameters (16.4%) | [8] |

| Hydrogenotrophic Methanogens | Abundant Methanomicrobiales taxa correlate with biogas production performance. | r = 0.665, P < 0.001 | [8] |

| Functional Redundancy | Methanogens have lower functional redundancy than fermentative bacteria. | Makes process more sensitive to methanogen population shifts. | [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Enrichment of Specialized Microbial Consortia

This protocol is adapted from methods used to enrich terephthalate-degrading consortia from environmental sediments [12].

1. Application: To obtain a microbial consortium capable of degrading a specific, potentially recalcitrant organic compound (e.g., terephthalamide, hydrocarbons).

2. Reagents & Materials:

- Bushnell Haas Broth (or other minimal salt media)

- Target carbon source (e.g., disodium terephthalate, terephthalamide)

- Environmental samples (sediment, soil, sludge)

- 125 mL Erlenmeyer flasks

3. Procedure:

- Inoculation: Add 0.5 g of environmental sample to 50 mL of Bushnell Haas media supplemented with the target carbon source (e.g., 10 g/L disodium terephthalate) in a 125 mL flask [12].

- Incubation: Incubate at a relevant temperature (e.g., 25°C) on an orbital shaker at 130 rpm [12].

- Subculturing: Every 14 days, transfer 5 mL of the enrichment culture into 50 mL of fresh media containing the same carbon source [12].

- Monitoring: Repeat this transfer process multiple times to select for a stable, specialized consortium. Monitor substrate degradation via HPLC [12].

- Analysis: After several transfers, collect biomass for 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing to identify the dominant taxa in the enriched consortium [12].

Protocol 2: DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing for Community Analysis

This protocol describes the standard method for characterizing microbial community composition, as used in multiple studies of anaerobic digesters and enriched cultures [11] [12] [9].

1. Application: To profile the taxonomic composition of a microbial community from an environmental sample or enrichment culture.

2. Reagents & Materials:

- PowerSoil DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen)

- E.Z.N.A. Mag-Bind Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek)

- PCR reagents (e.g., KAPA HiFi Hot Start ready mix)

- Primers for 16S rRNA gene (e.g., 341F/805R for Bacteria, 340F/1000R for Archaea)

3. Procedure:

- DNA Extraction:

- Extract genomic DNA from 0.25 g of homogenized sediment/sludge using a commercial kit like the Qiagen PowerSoil DNA kit or Omega Bio-tek Mag-Bind Soil DNA Kit, following the manufacturer's instructions [10] [9].

- Quantify DNA concentration using a fluorimeter (e.g., Qubit 2.0) and assess quality with a bioanalyzer (e.g., Agilent 2100) [9].

- PCR Amplification:

- Amplify the hypervariable V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene using primers 341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and 805R (GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC) [9].

- For Archaea, use primers such as 340F (CCCTAYGGGGYGCASCAG) and 1000R (GGCCATGCACYWCYTCTC) [9].

- Use a thermocycler with an appropriate program: initial denaturation (95°C, 3 min); 25-35 cycles of denaturation (95°C, 30 s), annealing (50-55°C, 30 s), elongation (72°C, 30 s); final extension (72°C, 5 min) [9].

- Sequencing and Analysis:

- Purity and pool PCR products for sequencing on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq) [10] [9].

- Process raw sequences through quality filtering, clustering into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) or Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs), and assign taxonomy by comparing to reference databases (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes) [11].

Metabolic Pathways and Syntrophic Interactions

The process of anaerobic digestion involves a sequence of metabolic stages—hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis—that are interconnected through syntrophic relationships. The following diagram illustrates the flow of metabolites and the key microbial groups involved in these pathways, highlighting the critical syntrophic partnerships, particularly between bacteria and archaea.

Diagram 1: Metabolic Pathways and Microbial Consortia in Anaerobic Digestion. The diagram shows the sequential breakdown of organic matter, highlighting the key functional groups of bacteria (red) and archaea (blue) involved at each stage. Critical syntrophic interactions, involving the transfer of H₂ between bacteria and hydrogenotrophic archaea, are emphasized with dashed red lines.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Kits for Microbial Consortia Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Product/Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Extraction of high-quality genomic DNA from complex environmental samples like sludge or sediment. | PowerSoil DNA Kit (Qiagen), E.Z.N.A. Mag-Bind Soil DNA Kit (Omega Bio-tek) [10] [9] |

| 16S rRNA Primers | Amplification of taxonomic marker genes for high-throughput sequencing of bacterial and archaeal communities. | 341F/805R (Bacteria), 340F/1000R (Archaea) [9] |

| PCR Master Mix | Robust and high-fidelity amplification of target DNA sequences for sequencing library preparation. | KAPA HiFi Hot Start Ready Mix (TaKaRa) [9] |

| Minimal Salt Media | Enrichment of specific microbial consortia by providing essential nutrients while making a target compound the sole carbon source. | Bushnell Haas Media [12] |

| Standards for qPCR | Absolute quantification of functional genes (e.g., mcrA, dsrA, acsB) to quantify specific microbial guilds. | Custom gBlocks Gene Fragments (IDT) [13] |

Influence of Feedstock on Microbial Community Structure and Diversity

Within the framework of anaerobic digestion (AD) for biogas production, the microbial community is the fundamental engine driving the conversion of organic matter into methane. The composition and structure of this microbial consortium are not static; they are profoundly shaped by the chemical nature of the feedstock introduced into the system. Understanding this relationship is critical for optimizing process stability and biogas yield. This Application Note synthesizes current research to elucidate how different feedstocks influence the microbial ecology within anaerobic digesters. It provides a structured overview of key findings, detailed experimental protocols for investigating these communities, and visualizations of the underlying metabolic pathways, serving as a practical resource for researchers and scientists in the field of bioenergy and environmental biotechnology.

Feedstock-Dependent Microbial Community Dynamics

The substrate introduced to an anaerobic digester acts as a primary selective pressure, determining which microbial populations will thrive. Feedstock composition varies widely in terms of complexity, nutrient balance, and the presence of inhibitory compounds, all of which directly shape the community structure.

Feedstock Type as a Selective Force: Research has conclusively demonstrated that the feedstock type strongly influences the microbial community structure, particularly in the first-stage (acidogenic) reactors. A study investigating communities enriched on various high-strength wastewaters found that feed type was a major driver of carbon removal efficiency and microbial community structure for 1st-stage fermenting communities [14]. Conversely, the second-stage (methanogenic) communities, which are fed the effluent from the first stage (primarily volatile fatty acids and alcohols), showed less variation based on the original feedstock [14]. This indicates that the chemical environment directly selects for specific functional groups.

Community Response to Feedstock Change: Microbial communities demonstrate a significant capacity to adapt to changing feedstock conditions. A study investigating the response of biogas microbiomes to a profound feedstock change from maize silage to sugar beet silage, and vice versa, observed a smooth adaptation of the microbial communities without a profound negative impact on the overall biogas production [15]. The bacterial community showed dynamic shifts, with taxa like Bacteroidetes and Sporochaetales increasing with the shift to the more easily degradable sugar beet silage. Notably, the archaeal community responsible for methanogenesis remained largely unchanged, highlighting the functional redundancy and stability of this critical functional group [15].

Absence of Universal Keystone Species: The search for universal "keystone species" directly tied to organic carbon degradation across all feed types has proven challenging. In a detailed analysis of suspended microbial cultures, it was shown that only one core genus and no unique genera were positively and significantly correlated to soluble COD (sCOD) removal across different feedstocks [14]. This suggests that excellent reactor performance is not dependent on a single, specific microbial population but is likely achieved by a consortium of organisms with overlapping functional roles that can assemble in response to the available substrate.

Table 1: Impact of Feedstock Type on Microbial Community Structure and Reactor Performance

| Feedstock Category | Impact on Bacterial Community | Impact on Archaeal Community | Key Performance Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Rich Wastewater | Enriches for proteolytic bacteria (e.g., Clostridium, Bacteroidetes) [2]. | Supports acetoclastic methanogens (e.g., Methanosaeta, Methanosarcina) from amino acid degradation [2]. | High ammonia/ammonium levels; potential inhibition at high concentrations [15]. |

| Lipid-Rich Wastewater | Enriches for syntrophic fatty acid-oxidizing bacteria (e.g., Syntrophomonas) [2]. | Requires close syntrophy with hydrogenotrophic methanogens (e.g., Methanoculleus, Methanobacterium) [16]. | High theoretical methane potential; risk of LCFA inhibition and foaming [16]. |

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Enriches for hydrolytic specialists (e.g., Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi) [2]. | Community shaped by hydrolysis products (sugars, acetate); mix of acetoclastic and hydrogenotrophic [17]. | Hydrolysis rate is often limiting; pretreatment can enhance digestibility [17]. |

| Simple Sugars (Whey Permeate) | Rapid acidogenesis; dominance of lactic acid bacteria and Trichococcus [16]. | Shift from acetoclastic (e.g., Methanosarcina) to hydrogenotrophic (e.g., Methanobacterium) under high load [16]. | High risk of acidification; requires careful control of OLR and pH [16]. |

Table 2: Core Microbial Functional Groups in Anaerobic Digestion and Their Roles

| Functional Group | Key Taxa (Examples) | Primary Metabolic Function | Sensitive To |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolytic Bacteria | Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi [2] | Secrete extracellular enzymes to break down polymers (proteins, carbs, lipids) into monomers [2]. | Feedstock particle size, lignin content, temperature. |

| Acidogenic Bacteria | Bacteroidetes, Clostridium [2] | Ferment monomers into volatile fatty acids (VFAs), alcohols, hydrogen, and carbon dioxide [2]. | pH, type of monomeric substrate. |

| Syntrophic Acetogens | Syntrophobacter, Syntrophomonas [2] | Oxidize VFAs (e.g., propionate, butyrate) to acetate, H₂, and CO₂ (obligate syntrophs) [2]. | H₂ partial pressure, temperature, ammonia. |

| Acetoclastic Methanogens | Methanosaeta, Methanosarcina [2] | Cleave acetate to form methane and carbon dioxide [2]. | Ammonia, VFA concentration, pH, temperature. |

| Hydrogenotrophic Methanogens | Methanobacterium, Methanobrevibacter, Methanoculleus [2] | Reduce CO₂ with H₂ to form methane [2]. | H₂ availability, trace metals (e.g., Nickel, Cobalt). |

Experimental Protocols for Microbial Community Analysis

To investigate the influence of feedstock on microbial communities, a combination of reactor operation, molecular biology techniques, and analytical chemistry is required. The following protocols provide a standardized approach for such investigations.

Protocol 1: Establishing Feedstock-Specific Enrichment Cultures

This protocol is adapted from the methodology used to determine how feed type influences community structure and carbon removal [14].

1. Reactor Setup and Inoculation:

- Use suspended flow-through reactors (e.g., continuous stirred-tank reactors, CSTRs) with a working volume of 1-2 L.

- Maintain mesophilic conditions (35-37°C) using a water jacket or incubator.

- Inoculate all reactors with the same anaerobic biomass, obtained from a stable full-scale digester. Sieve (e.g., 2 mm mesh) and pre-incubate the inoculum to reduce endogenous activity [16].

- Set an initial organic loading rate (OLR) of 2.0 g VS L⁻¹ d⁻¹ and a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 20-40 days, adjustable based on feedstock degradability [15].

2. Feedstock Preparation and Operation:

- Select contrasting feedstocks (e.g., synthetic starch-rich, protein-rich, lipid-rich wastewater, real brewery wastewater, and real dairy wastewater) [14].

- Standardize the chemical oxygen demand (COD) concentration of all feedstocks to ~8 g/L by dilution or concentration to ensure comparability.

- Feed reactors once daily. Continuously monitor biogas production, composition (CH₄, CO₂, H₂S), and pH.

- Regularly sample the digestate for analysis of volatile fatty acids (VFAs), total ammonium nitrogen (TAN), and COD to track process stability and performance.

3. Sampling for Microbial Community Analysis:

- Collect triplicate biomass samples (e.g., 50 mL of digestate) from each reactor during stable operation.

- Centrifuge samples at 10,000 × g for 10 minutes to pellet biomass. Discard the supernatant.

- Flash-freeze the pellet in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C until DNA extraction.

Protocol 2: DNA Extraction and 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing

This protocol details the molecular biological analysis of the collected samples [14] [15].

1. DNA Extraction:

- Extract genomic DNA from frozen biomass pellets using a commercial kit (e.g., DNeasy PowerSoil Kit, Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions.

- Perform extraction in triplicate for each sample to account for heterogeneity and ensure sufficient DNA yield.

- Quantify the extracted DNA using a fluorometric method (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) and check quality via agarose gel electrophoresis or spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio).

2. 16S rRNA Gene Amplification and Sequencing:

- Amplify the hypervariable regions of the bacterial and archaeal 16S rRNA gene via PCR. For bacteria, use primers such as 27F (5'-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3') and 926R (5'-CCGTCAATTCCTTTRAGTTT-3') [15].

- Include a fluorescent label (e.g., Cy5) on the forward primer if subsequent analysis by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (TRFLP) is planned [15].

- For high-throughput sequencing, use a platform like Illumina MiSeq with a standardized protocol (e.g., 515F/806R for both bacteria and archaea).

- Purify the PCR products and pool equimolar amounts of each sample for sequencing.

3. Bioinformatic and Statistical Analysis:

- Process raw sequencing data using a pipeline like QIIME 2 or mothur. Steps include quality filtering, denoising, chimera removal, and clustering of sequences into Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) or Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs).

- Assign taxonomy to ASVs/OTUs using a reference database (e.g., SILVA, Greengenes).

- Perform statistical analysis to correlate microbial community composition (e.g., via PCoA, NMDS) with process parameters (e.g., sCOD removal, VFA profile) and feedstock type. Use indicator species analysis to identify taxa significantly associated with specific feedstocks.

Metabolic Pathways and Microbial Interactions

The anaerobic digestion process is governed by a complex network of metabolic pathways and syntrophic interactions between bacteria and archaea. The following diagrams illustrate the flow of carbon and electrons from complex feedstock to methane, highlighting key pathways and microbial interactions.

Carbon Flow and Key Metabolic Pathways

Figure 1: Carbon flow from complex feedstock to biogas. The diagram shows the four key stages of anaerobic digestion: Hydrolysis, Acidogenesis, Acetogenesis, and Methanogenesis, and the primary substrates utilized by methanogens.

Interspecies Electron Transfer Mechanisms

A critical interaction for stable digestion, especially of fatty acids, is syntrophy, which relies on efficient interspecies electron transfer (IET) to maintain thermodynamic feasibility.

Figure 2: Interspecies electron transfer mechanisms. Syntrophic bacteria transfer electrons to methanogenic partners indirectly via hydrogen (IHT) or formate (IFT), or directly (DIET) through conductive materials or pili, which is more efficient.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Community Analysis in AD

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Protocol Use |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (Qiagen) | DNA extraction from complex digestate samples; effective lysis of tough microbial cells and removal of PCR inhibitors. | DNA extraction for 16S rRNA sequencing [15]. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Primers (27F/926R) | Amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA gene for community fingerprinting (TRFLP) or sequencing. | PCR amplification for microbial community analysis [15]. |

| Illumina MiSeq Reagent Kit | High-throughput sequencing of 16S rRNA amplicons to profile community composition and diversity. | 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing [14]. |

| Standardized Synthetic Wastewater | Defined feedstock for controlled experiments; allows isolation of the effect of specific components (starch, protein, lipids). | Enrichment cultures on specific feed types [14]. |

| Gas Chromatography (GC) System | Quantification of biogas composition (CH₄, CO₂) and volatile fatty acids (VFAs) in digestate. | Process monitoring and performance analysis [16] [17]. |

| pH & VFA/Alkalinity Test Kits | Rapid, on-site monitoring of process stability. Titration to determine VFA concentration and alkalinity. | Daily reactor monitoring and stability assessment [17]. |

Within the framework of research on anaerobic digestion (AD) for biogas production, the precise control of operational parameters is fundamental to optimizing process efficiency, stability, and metabolic outcomes. Temperature and pH are two of the most critical parameters, acting as primary regulators of microbial metabolism, community structure, and biochemical pathways. Anaerobic digestion can be conducted under different temperature regimes, primarily mesophilic (35–37 °C) and thermophilic (50–55 °C) conditions, each imparting distinct characteristics on the process [18]. Concurrently, pH dynamics serve as a key indicator of metabolic balance, particularly between acid-forming and methane-producing microorganisms [18]. This Application Note details the comparative effects of mesophilic and thermophilic temperatures, the critical role of pH, and their interrelationship. It provides validated protocols and datasets to guide researchers and scientists in the systematic optimization of anaerobic digestion systems for enhanced biogas production.

Comparative Analysis: Mesophilic vs. Thermophilic Digestion

The choice between mesophilic and thermophilic operation involves a trade-off between process stability and reaction rate. The table below summarizes the core performance characteristics of the two temperature regimes.

Table 1: Comparative performance of mesophilic and thermophilic anaerobic digestion.

| Parameter | Mesophilic (35-37 °C) | Thermophilic (50-55 °C) |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal Methane Yield | Lower yield compared to thermophilic | Peak yield of 363.3 mL/g VS reported at OLR of 4.5 g VS/(L·d) [19] |

| Hydrolysis Rate | Lower; often the rate-limiting step | Approximately twice as high as mesophilic, accelerating the initial breakdown [20] |

| Process Stability | More stable; less sensitive to perturbations [18] | Less stable; more prone to acidification and ammonia inhibition [21] [20] |

| Pathogen Reduction | Less effective | Enhanced destruction of viral and bacterial pathogens [19] [20] |

| Microbial Diversity | Higher diversity | Lower diversity and distinct community structure [20] |

| Energy Requirement | Lower heating requirement | Higher energy input needed to maintain temperature [21] [18] |

| Sensitivity to Ammonia | Less sensitive | More sensitive due to shift in ammonium/ammonia equilibrium [20] |

Thermophilic digestion offers significant advantages in terms of reaction kinetics and pathogen inactivation. The heightened metabolic activity at higher temperatures leads to a hydrolysis rate approximately double that of mesophilic systems, which can allow for shorter retention times or higher organic loading rates (OLRs) [20]. Furthermore, thermophilic conditions provide superior hygienization, which is a critical consideration for the land application of digestate [19]. However, this comes at the cost of reduced process stability. Thermophilic systems are more susceptible to inhibition from free ammonia (NH₃), which is more prevalent at elevated temperatures and can be toxic to methanogenic archaea, particularly aceticlastic methanogens [20]. They are also more sensitive to fluctuations in feeding regimes and temperature itself [18].

In contrast, mesophilic digestion is characterized by robust process stability and is generally considered more forgiving to operational fluctuations, making it a widely adopted standard in industrial applications [18]. The microbial community under mesophilic conditions is typically more diverse, which can contribute to greater functional resilience. However, this stability is coupled with slower reaction rates and lower pathogen kill, necessitating longer retention times [19] [20].

A promising approach to harness the benefits of both regimes is the Temperature Phase Anaerobic Co-Digestion (TPAcD) system. This two-stage configuration employs a short, initial thermophilic phase (e.g., 2 days) to maximize hydrolysis, followed by a longer mesophilic phase for stable methanogenesis. Research has demonstrated that TPAcD can increase methane yield by 50.3% and 32.7% compared to single-stage mesophilic and thermophilic systems, respectively [21].

pH Dynamics and Process Control

pH is a master variable in anaerobic digestion, directly influencing enzyme activity and the equilibrium of metabolic pathways. The optimal pH range for methanogenic archaea, the key methane-producing microorganisms, is narrow, typically between 6.8 and 7.2 [18]. Deviations from this range can severely inhibit methanogenesis, leading to process failure.

The Role of Alkalinity and VFAs

The pH stability is governed by the balance between the production of volatile fatty acids (VFAs) during acidogenesis and the buffering alkalinity of the system. Alkalinity, primarily from bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻) derived from CO₂ dissolution, acts as a buffer against rapid pH drops by neutralizing produced acids [18]. A stable process maintains a sufficient alkalinity concentration to prevent acid accumulation.

Process imbalance is often signaled by a buildup of VFAs, which consumes alkalinity and causes a drop in pH. If the acid production rate exceeds the methane production rate, this can create a vicious cycle of further pH drop and greater methanogenic inhibition, ultimately leading to process failure [18]. Therefore, monitoring the ratio of VFA to alkalinity is a common practice for assessing digester health.

Managing pH Instability

Several strategies can be employed to correct and prevent pH instability:

- Chemical Buffering: Adding sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) is a direct method to increase alkalinity and raise pH without introducing inhibitory ions [18].

- Co-digestion: Combining substrates with high buffering capacity, such as dairy manure, with easily acidogenic substrates, like food waste, can naturally enhance system stability [18].

- OLR Management: Controlling the organic loading rate prevents the overwhelming shock of VFA production, allowing methanogens to maintain pace.

Table 2: Key parameters and reagents for monitoring and controlling pH dynamics.

| Parameter/Reagent | Optimal Range/Function | Experimental/Operational Significance |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 6.8 - 7.2 [18] | Primary indicator of process balance; must be monitored frequently. |

| Alkalinity | >2000 mg/L as CaCO₃ (typical) | Measures the system's buffering capacity against VFA accumulation. |

| VFA/Alkalinity Ratio | <0.3-0.4 (as acetic acid) | An early warning indicator for impending process imbalance. |

| Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) | pH buffer | Used to raise alkalinity and pH directly; preferred due to minimal side effects. |

| Ammonia Nitrogen (NH₃-N) | <200 mg/L (inhibitory level varies) | High levels, especially in thermophilic systems, can be inhibitory and affect pH equilibrium [20]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Comparing Methanogenic Performance Across Temperature Regimes

This protocol outlines a methodology for establishing lab-scale anaerobic digesters to systematically evaluate the effect of temperature and organic loading rate (OLR) on methane yield and process stability.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Inoculum: Collect anaerobic digestate from a continuously stirred tank reactor (CSTR). For mesophilic and thermophilic experiments, use sludge acclimated to 37 °C and 55 °C for over 90 days, respectively [19].

- Substrate: Use homogenous organic waste (e.g., food waste, sewage sludge). Characterize by determining Total Solids (TS), Volatile Solids (VS), and elemental composition (C, H, O, N) to calculate C/N ratio and theoretical methane potential via the Buswell equation [19].

- Anaerobic Digesters: Batch or continuous stirred-tank reactors (e.g., 5 L working volume) with gas-tight seals, ports for feeding/sampling, and biogas outlet [21].

- Support Equipment: Heated water baths or external circulation heating systems for temperature control; gas collection system (e.g., gas bags, liquid displacement); biogas analyzer (e.g., Geotech Biogas 5000) for CH₄/CO₂ composition; pH meter.

II. Methodology

- Preparation:

- Determine the initial TS and VS of the inoculum and substrate [19] [21].

- Mix the substrate and inoculum in the digester. For a 5 L digester, a common ratio is 2 L of mixture to 1 L of inoculated sludge [21].

- Adjust the initial pH to 7.0 using NaOH or HCl solutions [21].

- Purge the headspace of each reactor with an inert gas (e.g., N₂) to ensure anaerobic conditions.

Operation:

- Assign reactors to mesophilic (35 °C) or thermophilic (55 °C) temperature groups. Maintain temperature within ±0.5 °C.

- Apply a stepped OLR increase. A typical range is 2.5 to 6.5 g VS/(L·d) for food waste [19]. Allow sufficient time (e.g., 3 hydraulic retention times) for the system to stabilize at each OLR before data collection.

- Apply continuous or intermittent mixing at a low speed (e.g., 50 rpm) [21].

Monitoring and Data Collection:

- Biogas Production: Measure daily biogas volume using a gas meter or liquid displacement system.

- Biogas Composition: Analyze CH₄, CO₂, and H₂S content regularly using a biogas analyzer [21].

- Process Parameters: Sample digestate periodically to measure pH, VFA concentration, and ammonia nitrogen (NH₃-N) [19] [21].

- Performance Calculation: Calculate specific methane yield (mL CH₄/g VSadded) for each OLR and temperature condition.

Protocol: Assessing Process Stability via pH and VFA Dynamics

This protocol focuses on tracking key indicators of process imbalance and implementing corrective measures.

I. Materials and Reagents

- Same as Protocol 4.1, with the addition of:

- Analytical Equipment: Gas Chromatograph (GC) with Flame Ionization Detector (FID) for VFA speciation and quantification [21]; spectrophotometer or discrete analyzer for ammonia nitrogen measurement.

- Buffering Reagents: Sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) solution.

II. Methodology

- Baseline Establishment: Under stable operating conditions, establish baseline values for pH, VFA profile (acetic, propionic, butyric acids), and alkalinity.

- Induction of Stress: Induce a controlled imbalance by pulsing a high OLR of substrate or by temporarily ceasing mixing. Monitor the system response.

- High-Frequency Sampling: During the stress period and recovery, sample digestate every 12-24 hours for immediate pH and VFA analysis.

- Corrective Action:

- If the pH drops below 6.8 and VFAs are accumulating, initiate buffering by adding a pre-determined volume of NaHCO₃ solution to restore alkalinity [18].

- If instability is severe, temporarily reduce the OLR to decrease the acid loading rate.

- Data Analysis: Plot the temporal trends of pH, total VFA, and methane production rate to visualize the onset of imbalance and recovery trajectory.

The logical relationship between temperature, pH, and their combined effect on microbial communities and process outcomes is visualized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues critical reagents, substrates, and analytical standards essential for conducting rigorous anaerobic digestion research.

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for anaerobic digestion experiments.

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Inoculum Sludge | Source of anaerobic microbial consortium. | Should be acclimated to the target temperature (mesophilic or thermophilic) for >90 days for stable baselines [19]. |

| Standardized Substrate | Organic feedstock for digestion. | Characterize by Total Solids (TS), Volatile Solids (VS), and C/N ratio. Food waste (C/N ~21.5) and sewage sludge (C/N ~6.6) are common [21]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) / Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | pH adjustment during setup or imbalance. | Used to calibrate initial pH to 7.0 [21]. |

| Sodium Bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) | Alkalinity and pH buffer. | Critical for counteracting VFA accumulation and preventing acid crash [18]. |

| VFA Standard Mix | Calibration for GC analysis. | Contains salts of acetic, propionic, butyric acids for quantifying VFA concentrations [21]. |

| Gas Standard Mix | Calibration for biogas analyzer. | Contains known proportions of CH₄, CO₂, and H₂S for accurate biogas composition measurement [21]. |

| Elemental Analyzer | Determining C/H/O/N composition of substrate. | Used to calculate theoretical methane potential (via Buswell equation) and C/N ratio [19]. |

The strategic management of temperature and pH is paramount for advancing anaerobic digestion research and technology. Mesophilic digestion offers reliability, while thermophilic processes provide enhanced kinetics and pathogen control, albeit with greater operational complexity. The emerging two-stage TPAcD configuration demonstrates that a synergistic approach can harness the strengths of both temperature regimes, leading to significant gains in methane productivity. Maintaining pH within the optimal range for methanogens through diligent monitoring and buffering is non-negotiable for stable process operation. The protocols and data presented herein provide a foundation for researchers to systematically investigate these critical parameters, optimize bioreactor performance, and contribute to the development of robust, efficient, and sustainable biogas production systems.

Microbial Synergies and Interspecies Electron Transfer Mechanisms

Within the engineered ecosystem of an anaerobic digester, the conversion of organic waste to biogas is accomplished through the coordinated activity of diverse microbial populations. This process is strictly dependent on syntrophic activities, defined as close cooperation between at least two organisms based on the transfer of metabolic products from one to another [22]. These microorganisms engage in complex networks of interspecies electron transfer (IET), which plays a crucial role in the methanogenesis process [23]. Three primary mechanisms of IET have been identified: interspecies hydrogen transfer (IHT), interspecies formate transfer (IFT), and direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) [23].

While IHT and IFT rely on hydrogen or formate as diffusive electron carriers, DIET represents a more efficient mechanism that utilizes conductive structures or materials to facilitate direct electron transfer between microorganisms [23]. DIET does not require hydrolysis or acidification and allows for direct conversion of organic matter into methane through syntrophic metabolism of DIET-active microorganisms, significantly improving anaerobic fermentation efficiency [23]. This application note details experimental approaches to study and enhance these microbial synergies, with particular focus on DIET mechanisms and their application in biogas production research.

Key Microbial Players and Electron Transfer Mechanisms

Microbial Communities in Anaerobic Digestion

Anaerobic digestion relies on a consortium of microorganisms operating through four main metabolic stages: hydrolysis, acidogenesis, acetogenesis, and methanogenesis [24] [22]. The microbial community in an anaerobic digester is characterized by complex networks of interactions, where each microorganism plays a specific role [24]. Syntrophic relationships between bacteria and archaea are particularly important, defined by their ability to transfer electrons at stable and fast rates to survive within the digester environment [24].

Table 1: Key Microbial Genera Involved in Interspecies Electron Transfer

| Microbial Group | Genus/Phylum | Function in AD | Role in Electron Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrogenic Bacteria | Geobacter | Organic acid oxidation | Direct electron donation via conductive pili and cytochromes [25] |

| Syntrophorhabdus | Syntrophic metabolism | Exhibits strong interaction strength with methanogens (0.14 ± 0.22) [26] | |

| Syntrophomonas | Butyrate oxidation | Limited interaction strength (0.01 ± 0.01) [26] | |

| Methanogenic Archaea | Methanosaeta | Acetoclastic methanogenesis | DIET participation; dominant with biochar amendment [24] [27] |

| Methanosarcina | Versatile methanogenesis | Accepts electrons via DIET; both hydrogenase-positive (M. barkeri) and cytochrome-dependent (M. acetivorans) types [25] | |

| Methanobacterium | Hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis | Dominant in electro-methanogenic communities [28] | |

| Methanomassiliicoccus | Hydrogen-dependent methylotrophy | Strong interaction partner for syntrophic bacteria [26] |

Molecular Mechanisms of Direct Interspecies Electron Transfer

DIET occurs through biologically conductive structures that form direct electrical connections between microbial cells. Geobacter species utilize conductive pili and outer-surface c-type cytochromes to transfer electrons to methanogenic partners [24]. In archaea, anaerobic methanotrophic (ANME) archaea like 'Candidatus Methanoperedens' engage in extracellular electron transfer using uncharacterized short-range electron transport protein complexes and OmcZ nanowires [29]. Electrochemical analyses of DIET-active communities reveal distinct redox potential signals at -0.18 V and +0.10 V (vs SHE), indicating at least two distinct redox protein complexes active in electron transfer from methane to electrodes [29].

Diagram 1: DIET Mechanisms. Solid blue lines show material-mediated DIET; dashed red line shows direct biological DIET.

Experimental Protocols for DIET Investigation

Protocol 1: Establishing DIET-Promoting Co-culture Systems

Principle: This protocol establishes defined synthetic microbial communities to investigate DIET mechanisms without interference from complex environmental microbiomes [25].

Materials:

- Strains: Geobacter metallireducens, Methanosarcina barkeri (Type I), Methanosarcina acetivorans (Type II)

- Culture media: Modified DSM 120 medium (see Table 4 for composition)

- Anaerobic chamber with N₂-CO₂ (80:20) atmosphere

- Serum bottles (110 mL) with thick butyl rubber stoppers

- Substrates: Ethanol (20 mM), methanol (100 mM), sodium acetate (50 mM)

Procedure:

- Pre-conditioning of G. metallireducens:

- Subculture G. metallireducens 3-5 times in ferric citrate medium with 20 mM ethanol replacing acetate

- Use 10% (v/v) inoculum transfer each time to ensure ethanol adaptation

Preparation of Methanosarcina pure cultures:

- Grow M. barkeri in modified DSM 120 with 0.2% NaCl and 100 mM methanol

- Grow M. acetivorans in modified DSM 120 with 0.2% NaCl (reduced from 0.5%) and 50 mM sodium acetate

- Incubate at 37°C until OD₆₀₀ reaches 0.4-0.6 (logarithmic growth phase)

Establishing co-culture systems:

- Under strict anaerobic conditions, inoculate cultures in DSM 120 medium at proportions below.

- Use 20 mM ethanol as substrate in 10 mL medium/110 mL anaerobic vial

- Incubate at 30°C for 38-70 days with three biological replicates

Table 2: Co-culture System Configurations

| System Type | Component Ratios | Key Characteristics | Expected Methane Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| SM-G (Single Methanosarcina) | M. barkeri + G. metallireducens (1:1) | Hydrogenase-positive metabolism; hydrogen cycling | Baseline (1x) [25] |

| SM-G (Single Methanosarcina) | M. acetivorans + G. metallireducens (1:1) | Cytochrome-dependent metabolism; Rnf complex energy metabolism | 3.0x increase over baseline [25] |

| DM-G (Dual Methanosarcina) | M. barkeri + M. acetivorans + G. metallireducens (1:1:1) | Metabolic complementarity; optimized electron allocation | 3.8x increase over baseline [25] |

Analytical Methods:

- Monitor headspace gas composition daily via gas chromatography

- Measure optical density at 600 nm for growth assessment

- Perform transcriptomic analysis to verify upregulation of DIET-related genes

Protocol 2: Bioelectrochemical Enrichment of Electroactive Communities

Principle: This protocol uses alternating polarity in bioelectrochemical systems to simultaneously enrich electroactive bacteria and electrotrophic methanogens for robust electro-methanogenesis [28].

Materials:

- Two-chamber bioelectrochemical systems (120 mL methanogenic chamber)

- Granular activated carbon (GAC, 50 g, particle size 2-3 mm)

- Potentiostat with three-electrode configuration

- Carbon brush working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, platinum counter electrode

- Substrate: Synthetic wastewater or organic waste streams

Procedure:

- System setup:

- Amend methanogenic chamber with 50 g GAC

- Add 60 mL substrate, creating 20 mL headspace

- Bury carbon brush working electrode in GAC

- Position Ag/AgCl reference electrode adjacent to working electrode

Alternating polarity program:

- Set potentiostat to alternate between +0.8 V and -0.4 V vs SHE

- Program with defined intervals (e.g., 6-hour cycles)

- Run enrichment for 4-6 weeks

Monitoring and analysis:

- Daily measurement of biogas production and composition

- Cyclic voltammetry scans (e.g., from -0.6 V to +0.2 V vs SHE at 1 mV/s)

- 16S rRNA gene sequencing of established communities

Expected Outcomes:

- Communities dominated by Methanobacterium (up to 74.3% abundance)

- Stable methane production rate of 0.18 mol CH₄/kg GAC/day

- Robust communities maintaining function after operational perturbations

Protocol 3: Conductive Material Amendment for DIET Enhancement

Principle: This protocol evaluates the enhancement of DIET in anaerobic digesters through amendment with carbon-based and iron-based conductive materials [23] [27].

Materials:

- Continuous stirred tank reactors (CSTRs) or batch reactors

- Conductive materials: Biochar, graphene, Fe₃O₄, Fe₃O₄@BC composite

- Substrate: Vegetable waste, thermo-chemically pretreated sludge

- Anaerobic inoculum from functioning digesters

Procedure:

- Material preparation:

- Biochar: Grind hardwood biochar to 1-8 mm particle size

- Fe₃O₄@BC synthesis: Prepare via co-precipitation method; load nano-Fe₃O₄ onto biochar surface

- Graphene: Prepare by exfoliating graphite using H₂SO₄/HNO₃ mixture, thermal shock at 1050°C, and ultrasonication

Reactor setup and operation:

- Use CSTRs with total volume 6 L (effective volume 4.5 L)

- Equip with temperature control, mechanical stirring, and pH monitoring

- Add conductive materials at varying concentrations:

- Biochar: 0-40 g/L

- Graphene: 50-1000 mg/L

- Fe₃O₄@BC: 100-300 mg/L

- Maintain organic loading rate (OLR) at 3.5-3.715 g VS/L·d

- Operate at mesophilic temperature (33-37°C)

Performance monitoring:

- Daily biogas production and composition analysis

- Volatile fatty acid (VFA) profiling via HPLC

- Microbial community analysis via 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing

- Specific methanogenic activity assays

Table 3: Performance Outcomes of Conductive Material Amendment

| Material | Optimal Dose | Methane Yield Increase | VFA Reduction | Key Microbial Shifts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochar | 20 g/L | 42.8% vs control [27] | Significant VFA degradation [24] | Methanothrix increased to 73.1% (vs 59.9% control) [27] |

| Graphene | 100 mg/L | 24.8% vs control [27] | Enhanced VFA transformation | Methanothrix increased to 85.4% [27] |

| Fe₃O₄@BC | 200 mg/L | Biogas production rate of 0.658 L/g VS [23] | Reduced VFA accumulation | Increased Christensenellaceae_R-7_group, Sphaerochaeta, Thermovirga [23] |

| Magnetite | Varies by system | Up to 70% improvement possible [30] | Accelerated propionate metabolism | Enriched Geobacter and Methanosarcina [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DIET Investigations

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Research Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified DSM 120 Medium | 0.5 mM sulfide, 1 mM cysteine, 0.22 g/L CaCl₂·2H₂O, 2 g/L NaHCO₃; no yeast extract, no Casitone [25] | Cultivation of DIET-relevant methanogens | Essential for synthetic co-culture systems; salinity adjustment needed for different Methanosarcina species [25] |

| Granular Activated Carbon (GAC) | Particle size 2-3 mm (6 mesh); high surface area | Electron conduit in DIET studies | Provides scaffold for microbial attachment and electron transfer; enhances community stability [28] |

| Biochar | Hardwood source, 1-8 mm particle size, specific surface area ~215 m²/g [27] | Low-cost conductive amendment | Enhances DIET while improving digestate dewaterability; optimal at 20 g/L [27] |

| Fe₃O₄@BC Composite | Nano-Fe₃O₄ loaded on biochar via co-precipitation | Synergistic DIET promotion | Combines conductivity of magnetite with microbial support of biochar; optimal at 200 mg/L [23] |

| Graphene | Exfoliated from graphite using H₂SO₄/HNO₃ treatment | High-conductivity DIET material | Superior conductivity but potential antimicrobial effects; use at low concentrations (100 mg/L) [27] |

| Anaerobic Serum Bottles | 110 mL volume with thick butyl rubber stoppers | Oxygen-free cultivation | Essential for maintaining strict anaerobic conditions for methanogen cultures [25] |

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for DIET Studies

Analytical Methods for DIET Validation

Electrochemical Techniques

Electrochemical analyses provide direct evidence of DIET activity in microbial systems:

Cyclic Voltammetry:

- Parameters: Scan from -0.6 V to +0.2 V vs SHE at 1 mV/s

- Interpretation: Identify redox peaks associated with electron transfer proteins

- Expected outcome: Distinct signals at -0.18 V and +0.10 V indicate active redox centers [29]

Chronoamperometry:

- Application: Monitor current production over time with methane as electron donor

- Validation: Compare current with and without methane supply

- Performance metrics: Methane-dependent current of 91-93% indicates high DIET activity [29]

Polarization Curves:

- Analysis: Determine onset potential of current production

- Validation: Onset near CH₄/CO₂ redox couple (-0.249 V at pH 7) confirms methane oxidation [29]

Microbial Community Analysis

Advanced molecular techniques elucidate DIET-associated microbial shifts:

16S rRNA Amplicon Sequencing:

- Target: Hypervariable regions (V3-V4) for bacteria and archaea

- Analysis: Track enrichment of DIET-relevant genera (Geobacter, Methanosarcina, Methanosaeta)

- Platform: Illumina MiSeq or NovaSeq with appropriate primers

Metatranscriptomics:

- Application: Identify upregulated DIET-related pathways

- Key targets: Conductive pili genes, multi-heme cytochromes, methanogenic enzymes

- Validation: Confirm expression of omcZ, pi1A, and methane metabolism genes [29]

Empirical Dynamic Modeling (EDM):

- Approach: Analyze daily time-series data to reconstruct microbial interaction networks

- Application: Quantify interaction strengths between syntrophic partners

- Outcome: Identify keystone species with strong syntrophic relationships (e.g., Syntrophorhabdus-Methanomassiliicoccus with interaction strength 0.14 ± 0.22) [26]

The protocols and methodologies detailed in this application note provide researchers with comprehensive tools for investigating and harnessing microbial synergies via interspecies electron transfer. DIET represents a promising mechanism to enhance anaerobic digestion efficiency, particularly in systems challenged by high organic loading, ammonia toxicity, or volatile fatty acid accumulation [30]. The experimental approaches outlined enable systematic study of DIET mechanisms, from defined co-culture systems to complex community reactors.

Future research directions should focus on optimizing conductive material properties, improving material reuse strategies, controlling potential metal toxicity, and validating scalability through pilot- and full-scale demonstrations [30]. Integration of novel cultivation strategies with advanced molecular analyses will continue to unravel the complexity of microbial electron transfer networks, enabling more efficient bioenergy recovery from organic wastes.

Enhancing Biogas Yield: Advanced Strategies for Process Intensification and System Design

Within the framework of anaerobic digestion (AD) research for biogas production, the pretreatment of organic substrates is a critical step for enhancing process efficiency and biogas yield. The complex lignocellulosic structure of many organic wastes, characterized by a resilient matrix of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, significantly limits their biodegradability and constitutes a major bottleneck, primarily during the hydrolysis phase [31] [32]. Pretreatment methods aim to disrupt this recalcitrant structure, thereby increasing the accessibility of organic compounds to microbial consortia in the digester. The choice of pretreatment is highly dependent on the chemical composition of the substrate, with lignocellulosic-, protein-, and lipid-rich feedstocks requiring distinct approaches for optimal bio-methanation [32]. This document details the primary pretreatment technologies—Cphysical, chemical, and biological—and provides specific application notes and experimental protocols for their implementation in a research setting.

Classification and Application of Pretreatment Methods

The efficacy of a pretreatment method is not universal but is intrinsically linked to the chemical dominance of the substrate. A meta-analysis of AD studies has demonstrated that grouping substrates by chemical composition (e.g., lignocellulosic-rich, protein-rich, lipid-rich) is fundamental for selecting a pretreatment that leads to a significant increase in methane yield, while inappropriate choices can result in non-significant or even adverse effects [32]. The following sections and tables summarize the key characteristics and applications of various pretreatment strategies.

Table 1: Overview of Pretreatment Methods for Different Substrate Types

| Pretreatment Category | Specific Methods | Primary Mechanism of Action | Ideal Substrate Types | Reported Methane Yield Increase (Examples) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical | Milling, Grinding, Extrusion, Ultrasonic, Hydrodynamic Cavitation | Reduces particle size, increases surface area, disrupts cell walls [31]. | Lignocellulosic biomass, sludge; often combined with other methods. | Varies with substrate and intensity; mechanical methods can be energy-intensive [31]. |

| Thermal | Thermal Hydrolysis, Steam Explosion, Hydrothermal | Disintegrates complex structures, solubilizes organic matter, breaks down lignocellulose [32]. | Protein-rich substrates (e.g., microalgae, slaughterhouse waste), lignocellulosics [32]. | Steam explosion: SMD=7.386; Hydrothermal: SMD=13.144 for protein-rich substrates [32]. |

| Chemical | Alkaline (e.g., NaOH), Acid, Deep Eutectic Solvents | Degrades lignin and hemicellulose, improves solubilization [31] [33]. | Lignocellulosic-rich substrates (e.g., agricultural residues) [33]. | Can exceed 100% increase in methane yield for lignocellulosics [31]. |

| Biological | Enzymatic (e.g., cellulase, protease, lipase), Fungal | Specific enzymatic hydrolysis of polymers (cellulose, proteins, lipids) [32]. | Protein-rich (enzymatic), Lignocellulosic-rich (fungal) [32] [33]. | Protease pretreatment for protein-rich: SMD=5.132; certain enzymatic blends can achieve up to 485% increase [31] [32]. |

| Hybrid | Thermo-Chemical, Bio-Physical (e.g., Enzymatic + Mechanical) | Combines mechanisms for synergistic effect, overcoming limitations of single methods [34] [33]. | Recalcitrant substrates like Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste (OFMSW) [34]. | Often superior to individual methods; co-pretreatment of thermal KOH and steam explosion shown effective for lignocellulosics [35]. |

Table 2: Advantages and Disadvantages of Pretreatment Categories

| Pretreatment Category | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages / Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | No inhibitory by-products, increases surface area [31]. | High energy consumption, one of the costliest phases [31]. |

| Thermal | Effective for cell disruption and pasteurization, full-scale application experience [32]. | High energy input, risk of forming recalcitrant or inhibitory compounds (e.g., Maillard products) [32]. |

| Chemical | Effective lignin removal, can be cost-efficient (e.g., alkaline) [36] [33]. | Possible formation of inhibitory by-products (e.g., furans from acids), need for pH neutralization, chemical cost [36]. |

| Biological | Low energy demand, high specificity, no toxic products, environmentally friendly [32]. | Can be slow, enzyme costs can be high, requires careful control of conditions [32]. |

| Hybrid | Can enhance overall efficiency, mitigate drawbacks of individual methods [31] [33]. | Increased process complexity, potentially higher combined costs. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Pretreatment Methods

Protocol: Alkaline Pretreatment for Lignocellulosic Substrates

Principle: Alkaline agents (e.g., NaOH) effectively break ester and glycosidic bonds between lignin, hemicellulose, and cellulose, leading to lignin solubilization and structural swelling, thereby enhancing enzymatic accessibility [36] [33].

Materials:

- Substrate: Dried and milled lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn stover, wheat straw).

- Reagent: Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) pellets or solution.

- Equipment: Autoclave or temperature-controlled water bath, pH meter, magnetic stirrer, vacuum filtration setup, balance.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Mill the biomass to a particle size of 1-2 mm. Determine the initial Total Solids (TS) and Volatile Solids (VS) content.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 2-10% (w/v) NaOH solution. Mix the biomass with the NaOH solution at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 (w/v) in a sealed reactor vessel.

- Incubation: Incubate the mixture at a temperature range of 50-121°C for 15 minutes to 24 hours. For ambient temperature pretreatment, extend the duration to 24 hours or more.

- Neutralization & Washing: After incubation, cool the mixture to room temperature. Neutralize the pH to ~7.0 using hydrochloric acid (HCl) with constant stirring.

- Solid Recovery: Separate the pretreated solids via vacuum filtration and wash with deionized water to remove residual salts and inhibitors. The solid fraction is now ready for anaerobic digestion assays.

Protocol: Enzymatic Pretreatment for Protein-Rich Substrates

Principle: Protease enzymes specifically hydrolyze peptide bonds in proteins, breaking them down into peptides and amino acids, which are more readily available for acidogenic bacteria, thus accelerating the hydrolysis bottleneck [32].

Materials:

- Substrate: Protein-rich waste (e.g., microalgae biomass, slaughterhouse waste).

- Reagent: Commercial protease enzyme preparation.

- Equipment: Incubator or water bath, pH meter, orbital shaker, centrifuge.

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Homogenize the substrate. If using microalgae, a slurry with a VS concentration of 5-10% is typical.

- Enzyme Addition: Adjust the substrate pH to the optimum range for the specific protease (typically pH 7-8 for neutral/alkaline proteases). Add the enzyme at a dosage of 0.1-1.0% (w/w of VS).

- Hydrolysis Reaction: Incubate the mixture at the enzyme's optimal temperature (e.g., 40-50°C) with mild agitation (100-150 rpm) for 4-12 hours.

- Reaction Termination: After the incubation period, heat the mixture to 90°C for 10 minutes to denature and deactivate the enzyme.

- Digestion Inoculation: Cool the hydrolysate to the digestion temperature (e.g., 37°C for mesophilic digestion) and proceed directly to biogas potential tests.

Protocol: Combined Thermo-Alkaline Pretreatment for Enhanced Sludge Digestion

Principle: This hybrid method combines the synergistic effects of heat and alkali to aggressively disrupt extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and microbial cell walls in wastewater sludge, significantly improving biodegradability [36].

Materials:

- Substrate: Wastewater activated sludge (WAS).

- Reagents: NaOH or Ca(OH)₂ solution.

- Equipment: Autoclave, pH meter, fume hood (if using ammonia), filtration setup.

Procedure:

- Sludge Conditioning: Adjust the pH of the sludge to 10-12 using a concentrated NaOH solution.

- Thermal Treatment: Transfer the alkaline sludge to an autoclave and treat at 121°C (1 bar pressure) for 30-60 minutes.

- Cooling and Adjustment: After treatment, cool the sludge rapidly. The pH can be left as is or partially neutralized, depending on the subsequent AD process requirements and its buffering capacity.

- Biomethane Potential (BMP) Test: Use the pretreated sludge directly in BMP assays to evaluate the enhancement in methane production compared to raw sludge.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Pretreatment Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Alkaline catalyst for lignocellulose delignification and sludge disintegration [36] [33]. | Alkaline and Thermo-Alkaline Pretreatment. |

| Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | Acid catalyst for hemicellulose hydrolysis in lignocellulosic biomass. | Acid Pretreatment. |

| Protease Enzyme | Hydrolyzes proteins into amino acids and peptides [32]. | Enzymatic pretreatment of protein-rich substrates (e.g., microalgae, slaughterhouse waste). |

| Cellulase Enzyme | Hydrolyzes cellulose into glucose monomers. | Enzymatic pretreatment of cellulosic materials. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Green solvents for selective extraction of lignin [33]. | Chemical pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. |

| Magnetite (Fe₃O₄) Nanoparticles | Catalyze direct interspecies electron transfer (DIET) between bacteria and methanogens, enhancing process stability and methane yield [37]. | Additive in anaerobic digestion following pretreatment. |

Visualization of Pretreatment Workflows and Microbial Impacts

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the logical workflow for selecting a pretreatment method and the subsequent impact on microbial communities within the anaerobic digester.

Diagram 1: Substrate Pretreatment Selection Workflow

Diagram 2: Microbial Community Response to Pretreatment

Anaerobic co-digestion (AcoD) has emerged as a pivotal strategy for enhancing biogas production within the broader context of sustainable waste management and renewable energy generation. This process leverages the synergistic effects of combining multiple organic feedstocks to balance nutrient profiles, dilute inhibitory compounds, and improve overall process stability and methane yield. The carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio is a critical parameter, as it directly influences microbial metabolism, buffer capacity, and the long-term stability of the anaerobic digestion process [38]. Imbalanced C/N ratios can lead to process inhibition; for instance, high nitrogen availability causes ammonium inhibition, while low nitrogen leads to insufficient microbial growth and system acidification [38] [39]. This application note provides a consolidated framework of optimal C/N ratios, detailed experimental protocols, and advanced enhancement strategies to guide researchers and scientists in optimizing AcoD systems for maximum methane production.

Quantitative Analysis of C/N Ratios and Feedstock Performance

A synthesis of recent research reveals distinct optimal C/N ratios and performance outcomes for various feedstock combinations, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Optimal C/N Ratios and Methane Yields for Various Co-digestion Feedstocks

| Feedstock Combination | Optimal C/N Ratio | Methane Yield at Optimal C/N | Process Stability Notes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lignocellulosic Residues & Goat Manure | 33 | 244 ± 15 mLN gVS-1 d-1 | Stable and effective production. Failure at C/N of 52. | [38] |

| Food Waste (FW) & Green Waste (GW) | 17-24 (FW:GW 4:1) | Not specified | Marked improvement in process performance, 64% shorter lag phase. | [40] [41] |

| Olive Pomace & Pig Manure | ~25 (35% Pig Manure) | 283 mL CH₄ gVS-1 | Overcame complete inhibition of olive pomace mono-digestion. | [42] |

| Paper Waste (PW) & Food Waste (FW) | 25 | 350 mL CH₄ gVS-1 (Batch); 13 L gVS-1 (CSTR) | Superb performance, 96% VS reduction. | [43] |

| Ulva lactuca & Cow Manure | ~20 (2:1 Ratio) | 325.75 mL CH₄ gVS-1 | Modified Gompertz model best fit the data (R²=0.999). | [44] |

The boundaries of process stability are clearly defined by specific thresholds. For instance, a C/N ratio of 43 with lignocellulosic residues and goat manure leads to process hindrance, while a C/N of 52 causes failure, characterized by a drop in pH to 5.4 and a VFA-to-alkalinity ratio increase to 0.9 [38]. Similarly, in Food Waste digestion, organic loading rates (OLR) exceeding 3.0 g VS/L/d trigger VFA accumulation above 20,000 mg/L and acidification (pH 5.94), collapsing biogas production [45].

Experimental Protocols for AcoD Optimization

Protocol: Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Assays for Feedstock Screening

Objective: To determine the specific methane yield and biodegradability of individual substrates and their mixtures.

Materials:

- Inoculum: Anaerobically digested sludge from a functioning wastewater treatment plant or biogas reactor.

- Substrates: Pre-treated, homogenized, and characterized feedstocks (e.g., FW, GW, manure).

- Equipment: 160-1000 mL glass serum bottles, helium gas, septum caps, water bath or incubator (37°C), pressure transducer, gas chromatograph.

Procedure:

- Preparation: Clean and dry serum bottles. Use a working volume typically between 0.8 L (in a 1 L bottle) and 120 mL (in a 160 mL bottle) [42] [43].

- Loading: Add substrates and inoculum based on predetermined VS ratios. Maintain an inoculum-to-substrate ratio (ISR) of 2:1 (on a VS basis) to ensure sufficient microbial activity [42]. For co-digestion tests, create mixtures with varying VS or C/N ratios (e.g., 4:1, 3:1, 1:1 FW:GW) [40].

- Anaerobic Atmosphere: Flush the headspace of each bottle with helium for 3-5 minutes to establish anaerobic conditions and seal immediately with airtight rubber septa [42] [43].

- Incubation: Place bottles in a thermostatic incubator at 37 ± 1°C for the test duration (typically 30-40 days). Provide periodic manual or mechanical shaking [40] [42].

- Monitoring: Measure daily biogas production via water displacement or pressure build-up. Periodically sample the headspace gas using a gastight syringe for compositional analysis (CH₄, CO₂) via gas chromatography [42].