Advanced Pretreatment Technologies for Lignocellulosic Biomass: Powering Sustainable Bioproducts and Biomedical Applications

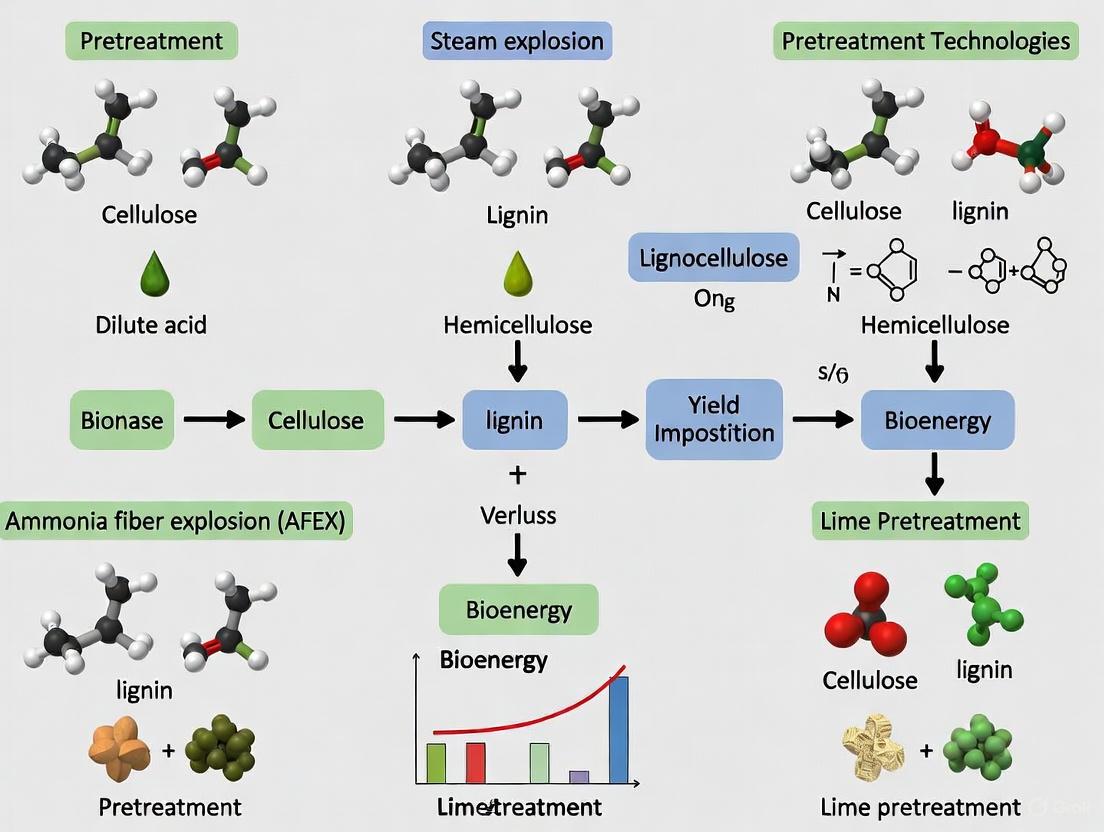

This article provides a comprehensive review of recent advancements in lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment technologies, a critical step for enabling the sustainable production of biofuels, biochemicals, and biomaterials.

Advanced Pretreatment Technologies for Lignocellulosic Biomass: Powering Sustainable Bioproducts and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of recent advancements in lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment technologies, a critical step for enabling the sustainable production of biofuels, biochemicals, and biomaterials. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental structure of biomass and the mechanisms of leading pretreatment methods. The scope extends to practical application strategies, troubleshooting of process inhibitors, and a comparative analysis of technological viability. By integrating foundational knowledge with methodological and optimization insights, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and advancing pretreatment processes to support innovations in biorefineries and the development of novel biomedical products like drug carriers and wound dressings.

Deconstructing Recalcitrance: The Structure of Lignocellulosic Biomass and the Imperative for Pretreatment

Lignocellulosic biomass represents one of the most abundant renewable resources for the production of biofuels and bio-based chemicals, serving as a critical alternative to fossil fuels. The complex architecture of plant cell walls, primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, creates a robust, recalcitrant structure that resists deconstruction [1] [2]. This inherent recalcitrance poses a significant challenge for efficient biomass conversion into fermentable sugars, making pretreatment an essential first step in any lignocellulose-based biorefinery process [3] [4]. The effectiveness of any pretreatment strategy hinges on a fundamental understanding of the physicochemical properties and interactions between these three primary constituents.

This Application Note provides a structured analysis of the composition and properties of lignocellulosic biomass. It includes detailed protocols for assessing key structural parameters and presents a case study on an advanced deep eutectic solvent (DES) pretreatment method. The information is designed to equip researchers with the practical knowledge and methodologies necessary to develop and optimize pretreatment technologies, thereby facilitating the efficient valorization of lignocellulosic feedstocks.

Quantitative Composition of Lignocellulosic Biomass

The proportion of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin varies significantly across different types of lignocellulosic biomass, directly influencing the selection and efficiency of pretreatment strategies. Cellulose is a linear homopolymer of glucose units linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, forming crystalline microfibrils that provide structural strength [5] [2]. Hemicellulose is a branched heteropolymer composed of various pentose and hexose sugars; its amorphous structure makes it more readily hydrolyzable than cellulose [5] [4]. Lignin, a complex three-dimensional aromatic polymer derived from phenylpropanoid units, imparts rigidity and hydrophobicity, and is a major contributor to biomass recalcitrance [1] [6].

Table 1: Representative Composition of Various Lignocellulosic Feedstocks

| Feedstock Type | Cellulose (%) | Hemicellulose (%) | Lignin (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn Stover | 38-40 | 28-30 | 7-21 | [4] |

| Wheat Straw | 35-45 | 25-30 | 15-20 | [4] |

| Sugarcane Bagasse | 40-45 | 30-35 | 20-25 | [4] |

| Pine (Softwood) | 40-45 | 25-30 | 26-34 | [4] |

| Eucalyptus (Hardwood) | 45-50 | 25-30 | 20-25 | [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Compositional Analysis and Pretreatment

Protocol: Two-Stage Acid Hydrolysis for Compositional Analysis

This standardized protocol determines the carbohydrate and lignin content of lignocellulosic biomass [7].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- 72% Sulfuric Acid: Primary hydrolyzing agent for initial disruption of cellulose crystalline structure.

- Deionized Water: Dilution medium for secondary hydrolysis of oligomers to monomers.

- Enzymes (Cellulase, Xylanase): Biological catalysts for polysaccharide hydrolysis under mild conditions [8].

Procedure:

- Milling and Drying: Mill the biomass feedstock to a particle size of 0.2-0.5 mm. Dry at 105°C until constant weight.

- Primary Hydrolysis: Weigh 0.3 g of dry biomass into a test tube. Add 3.0 mL of 72% (w/w) sulfuric acid. Incubate in a water bath at 30°C for 60 minutes with intermittent stirring.

- Secondary Hydrolysis: Dilute the acid mixture with 84 mL deionized water (resulting in a ~4% acid concentration). Autoclave the solution at 121°C for 60 minutes.

- Filtration and Separation: Filter the hydrolysate through a calibrated crucible. The solid residue is designated as acid-insoluble lignin (Klason lignin).

- Quantification:

- Wash the solid residue, dry at 105°C, and weigh to determine Klason lignin.

- Analyze the liquid filtrate for acid-soluble lignin by UV-spectrophotometry at 205-240 nm.

- Quantify the monomeric sugar content (glucose, xylose, arabinose, etc.) in the filtrate using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). Convert sugar concentrations to polysaccharide (cellulose and hemicellulose) content using appropriate stoichiometric calculations.

Protocol: DES Pretreatment for Enhanced Hemicellulose Retention

This protocol describes a pretreatment method using an ethylene glycol (EG)-regulated basic deep eutectic solvent (DES) to achieve high delignification while maximizing hemicellulose retention [9].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Choline Chloride (ChCl): A common, biodegradable hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) for DES formation.

- Diethanolamine (DEA): Hydrogen bond donor (HBD) that creates a basic environment for selective lignin removal.

- Ethylene Glycol (EG): Adjuvant that modulates DES action, stabilizing hemicellulose and preventing its degradation.

- Commercial Cellulase (e.g., Cellic CTec3): Enzyme cocktail for saccharification of pretreated biomass [9].

Procedure:

- DES Preparation: Synthesize the basic DES by mixing Choline Chloride and Diethanolamine at a molar ratio of 1:6 (HBA:HBD) at 80°C with stirring until a homogeneous, clear liquid forms.

- Solvent Regulation: Add Ethylene Glycol to the prepared DES at a mass ratio of DES:EG = 1:3.

- Biomass Treatment: Mix the regulated DES with corncob biomass (or other feedstock, 40-60 mesh) at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:15 (w/v).

- Pretreatment Reaction: React the mixture at 120°C for 60 minutes in a sealed reactor with constant agitation.

- Separation and Washing:

- After the reaction, cool the mixture and separate the solid residue by filtration.

- Wash the solid residue thoroughly with a water-ethanol mixture (e.g., 70% ethanol) to remove residual DES and dissolved lignin.

- Recover the washed solid fraction (rich in cellulose and hemicellulose) for downstream applications like enzymatic hydrolysis.

Case Study: DES Pretreatment of Corncob

Background: Traditional acidic pretreatments often lead to significant hemicellulose loss, reducing the overall sugar yield. A study investigated an EG-regulated ChCl/DEA DES to overcome this limitation [9].

Methodology: Corncob was pretreated using the protocol in Section 3.2. The composition of the solid residue was analyzed, and its enzymatic digestibility was tested.

Table 2: Performance Data of EG-Regulated DES Pretreatment on Corncob

| Performance Metric | Result | Analysis Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulose Retention | 88.1% | High preservation of primary carbohydrate source. |

| Hemicellulose Retention | 77.9% | Significant improvement over acidic methods, preserving pentose sugars. |

| Delignification | 84.3% | Effective breakdown and removal of the recalcitrant lignin barrier. |

| Enzymatic Hydrolysis Glucose Yield | 90.3% | High conversion efficiency of retained cellulose to fermentable glucose. |

| Enzymatic Hydrolysis Xylose Yield | 81.3% | High conversion efficiency of retained hemicellulose to xylose. |

Mechanism Investigation: The study employed density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to elucidate the mechanism. The results indicated that the EG solvent molecules effectively disrupt the hydrogen-bonding network within the biomass structure. Concurrently, the basic DES selectively cleaves the β-O-4 ether linkages in lignin, which are the most abundant inter-unit bonds in the lignin polymer [9]. This synergistic action results in effective delignification while the EG stabilizes the hemicellulose fraction, preventing its excessive degradation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Lignocellulosic Biomass Pretreatment Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Choline Chloride | Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Formation of Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) for green fractionation [9]. |

| Lactic Acid / Diethanolamine | Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Component of acidic/basic DES for lignin solubilization or carbohydrate protection [9]. |

| Ethylene Glycol | Solvent Adjuvant / Stabilizer | Modulates DES action to enhance hemicellulose retention during pretreatment [9]. |

| Cellulase/Xylanase Cocktails | Enzymatic Hydrolysis | Saccharification of cellulose and hemicellulose in pretreated biomass to fermentable sugars [9] [8]. |

| Sulfuric Acid (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Acid Catalyst | Standard reagent for compositional analysis and acidic pretreatments [3] [7]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Alkaline Catalyst | Alkaline pretreatment for lignin removal and swelling of cellulose [1] [10]. |

| Acth (4-11) | Acth (4-11), CAS:67224-41-3, MF:C50H71N15O11S, MW:1090.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ammuxetine | Ammuxetine, MF:C15H17NO3S, MW:291.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Addressing the "tripartite challenge" posed by cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin is fundamental to unlocking the potential of lignocellulosic biomass. The intricate interplay between these components dictates biomass recalcitrance and necessitates tailored pretreatment approaches. As demonstrated by the EG-regulated DES case study, modern pretreatment strategies are evolving towards systems that not only disrupt the lignin-carbohydrate complex effectively but also preserve valuable carbohydrate fractions. The protocols and data outlined in this Application Note provide a foundational framework for researchers to systematically evaluate and develop next-generation pretreatment technologies, ultimately advancing the efficiency and economic viability of the lignocellulosic biorefinery.

Lignocellulosic biomass, primarily composed of cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin, represents a promising renewable resource for the production of second-generation biofuels and biobased chemicals, without compromising global food security [2] [11]. However, the inherent recalcitrance of plant cell walls to microbial and enzymatic deconstruction poses a major technical and economic challenge for its industrial valorization [2] [12]. This recalcitrance is largely attributed to the complex structural and chemical nature of lignin, a complex aromatic polymer that accounts for 15-40% of lignocellulosic biomass by dry weight [2] [13]. Lignin forms a robust, heterogeneous, three-dimensional network within the plant cell wall, embedding cellulose and hemicellulose and thereby reducing their accessibility to hydrolytic enzymes [2] [12]. This application note delineates the fundamental mechanisms by which lignin impedes enzymatic hydrolysis and provides detailed protocols for investigating these interactions, framed within the context of pretreatment technologies for lignocellulosic biomass research.

The Dual Mechanisms of Lignin Recalcitrance

Lignin inhibits the enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose through two primary, interconnected mechanisms: acting as a physical barrier and engaging in non-productive adsorption with cellulolytic enzymes [12] [13] [6]. The following diagram illustrates these core mechanisms and the strategies to mitigate them.

Physical Barrier and Steric Hindrance

Lignin forms a protective shield around cellulose and hemicellulose fibers through covalent and non-covalent bonds, creating lignin-carbohydrate complexes (LCCs) [12] [14]. This intricate matrix provides structural rigidity and significantly limits the accessible surface area of cellulose for enzymatic attachment and catalysis [2] [13]. The physical blockage is a major contributor to biomass recalcitrance, as it prevents cellulases from reaching their target substrates.

Non-productive Enzyme Adsorption

A critical challenge is the non-productive binding of cellulases to lignin surfaces. Unlike the productive binding to cellulose, this interaction renders the enzymes inactive and can lead to their irreversible deactivation [13] [15] [6]. The adsorption is driven by multiple forces:

- Hydrophobic interactions between non-polar regions of enzymes and the aromatic lignin polymer [15].

- Electrostatic interactions influenced by the surface charge of both lignin and enzymes, which is dependent on pH [15] [6].

- Hydrogen bonding between functional groups on lignin (e.g., phenolic hydroxyls) and the enzyme's protein structure [2] [13].

Quantitative Impact of Lignin on Hydrolysis Efficiency

The table below summarizes key lignin properties and their quantified impact on enzymatic hydrolysis, as established in recent literature.

Table 1: Correlation between Lignin Properties and Enzymatic Hydrolysis Efficiency

| Lignin Property | Impact on Enzymatic Hydrolysis | Quantitative Findings | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Content | Generally negative correlation | In bamboo, 15.3% lignin content vs. 21.0% resulted in significantly higher deconstruction efficiency. | [14] |

| S/G Ratio | Contradictory findings; depends on system | Higher S/G ratio negatively correlated with hydrolysis in untreated engineered poplar and eucalyptus. | [12] [16] |

| Hydrophobicity | Negative correlation | Increased condensation from severe pretreatments raises hydrophobicity and enzyme adsorption. | [12] [16] |

| Functional Groups | Varies by group | Phenolic hydroxyl groups cause reversible inhibition of cellulases; blocking them reduced inhibition by 65-91%. | [2] |

| Molecular Weight | Negative correlation for isolated lignin | Low molecular-weight, water-soluble lignins (e.g., lignosulfonates) can enhance hydrolysis, unlike high M.W. lignin. | [6] |

Table 2: Affinity of Trichoderma reesei Cellulases for Lignin-Rich Residues (Langmuir Model)

| Enzyme | Type | Binding Affinity Rank (L-HPS) | Binding Affinity Rank (L-HPWS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TrCel5A | Endoglucanase | 1 (Highest) | 1 (Highest) |

| TrCel6A | Cellobiohydrolase | 2 | 2 |

| TrCel7B | Endoglucanase | 3 | 3 |

| TrCel7A | Cellobiohydrolase | 4 (Lowest) | 4 (Lowest) |

L-HPS: Lignin from Hydrothermally Pretreated Spruce; L-HPWS: Lignin from Hydrothermally Pretreated Wheat Straw [15].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 4.1: Assessing Enzyme Adsorption on Lignin-Rich Substrates

This protocol quantifies the binding affinity and kinetics of monocomponent cellulases on lignin-rich residues (LRRs) [15].

1. Materials

- Lignin-Rich Residues (LRRs): Prepare from hydrothermally pretreated biomass (e.g., spruce, wheat straw) via extensive enzymatic hydrolysis followed by protease treatment to remove adsorbed proteins.

- Purified Monocomponent Cellulases: e.g., TrCel7A, TrCel6A, TrCel7B, TrCel5A from Trichoderma reesei.

- Buffer: Sodium acetate buffer (50 mM, pH 5.0).

- Equipment: Thermostatted water bath, microcentrifuge, SDS-PAGE apparatus, protein assay kit.

2. Method

1. Radiolabeling (Optional): Radiolabel purified enzymes to allow for highly sensitive quantification.

2. Adsorption Isotherm:

- Prepare a series of microcentrifuge tubes with a constant mass of LRRs.

- Add a gradient of enzyme concentrations to the tubes in sodium acetate buffer.

- Incubate at 4°C for a set time (e.g., 4 hours) with gentle agitation to reach equilibrium.

- Centrifuge to separate the solid LRRs from the liquid.

- Quantify the free protein concentration in the supernatant using a suitable assay.

- Calculate the adsorbed protein: q = (C_i - C_f) * V / m, where q is adsorbed protein (mg/g lignin), C_i and C_f are initial and final protein concentrations (mg/mL), V is volume (mL), and m is mass of LRRs (g).

3. Data Analysis: Fit the q vs. C_f data to the Langmuir adsorption model: q = (q_max * K * C_f) / (1 + K * C_f), where q_max is maximum adsorption capacity and K is the affinity constant.

3. Interpretation

- A higher

Kvalue indicates stronger binding affinity. - Compare affinities across different enzymes and LRR sources (see Table 2).

Protocol 4.2: Evaluating the Impact of Lignin Blocking Additives

This protocol tests the efficacy of additives in mitigating non-productive adsorption [6].

1. Materials

- Pretreated lignocellulosic substrate.

- Cellulase enzyme cocktail.

- Additives: Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), Tween 80.

- Buffer: Sodium citrate buffer (50 mM, pH 4.8).

2. Method 1. Set up hydrolysis reactions containing a fixed load of substrate and enzyme. 2. Introduce varying concentrations of the selected additive to the reaction tubes. 3. Incubate at 50°C with agitation for 24-72 hours. 4. Withdraw samples at defined time intervals, centrifuge, and analyze the supernatant for released reducing sugars (e.g., using DNS method or HPLC).

3. Interpretation

- Compare the sugar yield and hydrolysis rate of additive-supplemented reactions against a control (no additive).

- A significant increase in sugar yield indicates that the additive is successfully blocking non-productive binding sites on lignin.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Lignin-Enzyme Interactions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Monocomponent Cellulases | To study specific enzyme-lignin interactions and binding affinities for individual enzyme types. | Adsorption isotherm experiments (Protocol 4.1). |

| Lignin-Rich Residues (LRRs) | A substrate with high lignin content used to investigate non-productive adsorption in a controlled manner. | Studying fundamental lignin-enzyme interactions without cellulose interference. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A blocking agent that adsorbs to lignin, reducing non-productive binding of cellulases. | Additive screening to boost saccharification yield (Protocol 4.2). |

| PEG & Tween 80 | Surfactants that reduce hydrophobic interactions between enzymes and lignin. | Mitigating enzyme deactivation and improving hydrolysis efficiency. |

| Lignosulfonate | A water-soluble, sulfonated lignin. At low M.W., it can compete with residual lignin for enzyme binding, promoting hydrolysis. | Investigating the paradoxical positive effects of specific lignin types. |

| AChE-IN-68 | AChE-IN-68, MF:C23H22N4O3S, MW:434.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| (+)-Picumeterol | (+)-Picumeterol, MF:C21H29Cl2N3O2, MW:426.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Lignin's role as a natural barrier to hydrolysis is multifaceted, involving complex physical and chemical interactions that severely impede the enzymatic deconstruction of lignocellulosic biomass. A deep understanding of its structural characteristics—such as content, composition, functional groups, and hydrophobicity—is crucial for developing advanced pretreatment technologies and targeted mitigation strategies. The protocols and data summarized in this application note provide a foundation for researchers to systematically investigate these interactions. Overcoming lignin recalcitrance is a keystone in the development of economically viable lignocellulosic biorefineries, enabling the sustainable production of biofuels and biomaterials.

Lignocellulosic biomass (LCB), the most abundant renewable biological resource on Earth, presents a paradoxical challenge: its robust structural integrity, essential for plant survival, fundamentally limits its industrial utilization for biofuel and bioproduct production [17] [18]. This inherent recalcitrance stems from the complex composite structure of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, which collectively form a physical and chemical barrier that severely restricts enzyme accessibility to polysaccharides [19] [20]. The core objective of pretreatment is therefore to disrupt this lignocellulosic matrix, modify its physicochemical properties, and ultimately create a substrate amenable to efficient enzymatic hydrolysis [21].

The structural basis of recalcitrance lies in the organization of the plant cell wall. Cellulose, a linear polymer of glucose linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, forms crystalline microfibrils with both highly ordered and amorphous regions [17] [18]. These microfibrils are embedded in a matrix of hemicellulose, a branched heteropolymer of various pentose and hexose sugars, and cross-linked by lignin, a complex three-dimensional phenolic polymer that acts as a natural waterproof glue [17] [21]. This architecture creates a formidable barrier where lignin physically blocks enzyme access to cellulose and hemicellulose while also irreversibly binding and deactivating hydrolytic enzymes [18]. Effective pretreatment must consequently achieve several key outcomes: disrupt lignin seal, increase biomass surface area and porosity, reduce cellulose crystallinity, and minimize the generation of fermentation inhibitors [20].

Key Structural Modifications and Their Mechanisms

Primary Mechanisms of Matrix Disruption

Pretreatment technologies employ diverse mechanisms to deconstruct the lignocellulosic matrix, with the specific approach dictating the resultant substrate characteristics and subsequent hydrolysis efficiency [22]. These mechanisms can be broadly categorized based on their primary mode of action:

Lignin Removal/Solubilization: Methods like organosolv, alkaline, and ionic liquid pretreatments primarily target the lignin fraction by breaking ester and ether bonds cross-linking lignin to carbohydrates, thereby removing the physical barrier and exposing the polysaccharide framework [23] [20]. For instance, organosolv pretreatment using ethanol-water mixtures with an acid catalyst effectively cleaves aryl-ether linkages in lignin, allowing fragments to solubilize through hydrogen bonding with the solvent [23].

Hemicellulose Hydrolysis: Dilute acid and hydrothermal pretreatments predominantly solubilize the hemicellulose fraction, disrupting the connection between lignin and cellulose and increasing pore accessibility [24] [20]. This process often involves the hydrolysis of glycosidic bonds in hemicellulose chains, which can also generate inhibitory compounds like furfural and acetic acid if conditions are too severe [17].

Structural Destabilization: Physical methods like extrusion and mechanical milling, as well as biological pretreatment using white-rot fungi, primarily act by reducing particle size, cellulose crystallinity, and polymerization degree, thereby creating more amorphous regions susceptible to enzymatic attack [25] [20]. Extrusion employs shear force and temperature to physically tear apart the biomass structure, while fungal enzymes like lignin peroxidases and manganese peroxidases selectively degrade lignin [25].

Table 1: Key Mechanisms of Different Pretreatment Categories

| Pretreatment Category | Primary Mechanism | Key Structural Changes |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical (Alkali) | Solubilization of lignin, saponification of intermolecular esters | Lignin removal, increased porosity, cellulose swelling |

| Chemical (Acid) | Hydrolysis of hemicellulose, depolymerization of cellulose amorphous regions | Hemicellulose removal, increased cellulose accessibility |

| Physico-chemical (Organosolv) | Solvent cleavage of lignin-carbohydrate complexes, lignin dissolution | High-purity lignin removal, cellulose and hemicellulose fractionation |

| Physico-chemical (Extrusion) | Shear-induced deformation, thermal disruption of matrix | Particle size reduction, crystallinity decrease, fibrillation |

| Biological (Fungal) | Enzymatic lignin degradation via peroxidases and laccases | Selective delignification, minimal carbohydrate loss |

Quantitative Impact on Biomass Properties and Hydrolysis Efficiency

The efficacy of a pretreatment method is quantitatively reflected in parameters such as delignification percentage, cellulose crystallinity index (CrI), and the resulting sugar yields from enzymatic hydrolysis. Combined pretreatment strategies often demonstrate superior performance by addressing multiple recalcitrance factors simultaneously.

Research on an extrusion-biodelignification (Ex-SSF) approach for black spruce and corn stover demonstrated the power of combined pretreatments. The sequential process achieved delignification of 59.1% and 65.4% for black spruce and corn stover, respectively, far exceeding the maximum 17% achieved with biological pretreatment alone [25]. This dramatic lignin removal directly enhanced enzymatic digestibility, with sugar recovery from pretreated black spruce being 2.3 times that of the raw biomass [25]. Furthermore, the study highlighted a shift in the primary delignification mechanism; while lignin peroxidase was dominant in negative controls, manganese peroxidase (MnP) became the main contributor in the Ex-SSF process, with activities reaching 32.0 U/L for corn stover [25].

Similarly, a comparison of hydrothermal, ammonia, and ionic liquid pretreatments for transgenic sugarcane bagasse revealed significant differences in sugar yields and subsequent ethanol production. Soaking in aqueous ammonia (SAA) generated hydrolysates containing 253.73 g/L of sugars, supporting an ethanol titer of 100.62 g/L [26]. The superior fermentability of ammonia-pretreated hydrolysate was attributed to lower concentrations of inhibitory compounds like acetic acid compared to hydrothermal pretreatment [26].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Advanced Pretreatment Strategies

| Pretreatment Method | Feedstock | Delignification (%) | Sugar Yield | Ethanol Titer/Product Yield |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrusion-Biodelignification (Ex-SSF) | Black Spruce | 59.1% | 2.3x increase vs. raw biomass | - |

| Extrusion-Biodelignification (Ex-SSF) | Corn Stover | 65.4% | 44% improvement vs. raw biomass | - |

| Soaking in Aqueous Ammonia (SAA) | Oilcane Bagasse | - | 253.73 g/L | 100.62 g/L |

| Hydrothermal | Oilcane Bagasse | - | 213.10 g/L | 64.47 g/L |

| Ionic Liquid (Cholinium Lysinate) | Oilcane Bagasse | - | 154.20 g/L | 52.95 g/L |

| Two-Stage Oxalic Acid/Organosolv | Multi-Feedstock Mixture | 44.69% (Lignin Recovery) | - | - |

Experimental Protocols for Pretreatment and Analysis

Protocol 1: Two-Stage Acid-Organosolv Pretreatment for Lignin Recovery

This protocol describes a sequential fractionation method to first remove hemicellulose using dilute organic acid, followed by organosolv delignification to recover a relatively pure lignin stream [23].

Materials:

- Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., brewer's spent grain, agricultural residues)

- Oxalic acid (Hâ‚‚Câ‚‚Oâ‚„)

- Ethanol (absolute and aqueous solutions)

- Deionized water

- High-pressure tubular reactors or autoclave

Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: Oven-dry biomass at 85°C for 48 hours. Mill and screen to a particle size of 10 mesh or smaller.

- First Stage - Dilute Oxalic Acid Hydrolysis:

- Prepare an oxalic acid solution (e.g., 83.15 mg acid per gram of biomass) in a solid-to-liquid ratio of 100 g biomass per liter.

- Load the mixture into a pressurized reactor.

- Heat to 135°C and maintain for 180 minutes.

- Quench the reaction and separate the solid fraction (cellulose-rich) from the liquid hydrolysate (containing hemicellulose sugars and inhibitors like furfural).

- Wash the solids and dry at 48°C overnight.

- Second Stage - Oxalic Acid-Assisted Organosolv:

- Suspend the dried solids from Step 2 in a 75% (v/v) ethanol-water solution.

- Load the mixture into a pressurized reactor.

- Heat to 190°C and maintain for 120 minutes.

- After reaction, separate the solid fraction (cellulose-rich pulp) from the liquid stream (containing solubilized lignin).

- Recover lignin from the liquid by precipitating with water or evaporating the solvent.

- Analysis: Characterize the final solid fraction for chemical composition (cellulose, residual hemicellulose, lignin). Analyze the recovered lignin for purity and structural properties using techniques like HSQC NMR [23].

Protocol 2: Integrated Extrusion-Biodelignification (Ex-SSF) Pretreatment

This protocol combines thermo-mechanical extrusion with semi-solid fermentation (SSF) using fungi for enhanced delignification [25].

Materials:

- Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., wood chips, corn stover)

- White-rot fungal inoculum (e.g., Phanerochaete chrysosporium)

- Extruder with temperature control

- Fermentation vessels

- Reagents for enzyme assays (e.g., for Manganese Peroxidase)

Procedure:

- Extrusion Step:

- Mill raw biomass to a suitable particle size for feeding into the extruder.

- Optimize extrusion parameters (e.g., temperature profile, screw speed, and biomass moisture content) via experimental design. The mechanical shear and heat disrupt the biomass physical structure.

- Collect the extrudate.

- Semi-Solid Fermentation (SSF) Step:

- Inoculate the extrudate with the fungal culture in the fermentation vessel.

- Maintain moisture content and aeration suitable for fungal growth.

- Incubate at the fungus's optimal temperature (e.g., 28-30°C) for a predetermined period (typically several days to weeks).

- Monitor the activity of ligninolytic enzymes like Manganese Peroxidase (MnP) and Lignin Peroxidase (LiP) periodically.

- Termination and Analysis:

- Terminate the fermentation.

- Analyze the pretreated biomass for delignification percentage and cellulose crystallinity index (CrI) using X-ray Diffraction (XRD).

- Perform enzymatic digestibility tests on the pretreated solids to quantify sugar yield improvements [25].

Workflow and Pathway Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Pretreatment Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oxalic Acid | Organic acid catalyst for hemicellulose hydrolysis. Effective in sequential pretreatments due to high acidity (pKa₠≈ 1.23) and renewable nature [23]. | Used in dilute acid hydrolysis stage (e.g., 83.15 mg/g biomass) to solubilize hemicellulose prior to organosolv [23]. |

| Ethanol-Water Solvent | Medium for organosolv pretreatment. Facilitates lignin dissolution and fractionation upon heating under pressure. | A 75% (v/v) ethanol solution at 190°C for 120 minutes achieved 44.69% lignin recovery [23]. |

| Aqueous Ammonia | Alkaline agent for soaking pretreatment. Effectively solubilizes lignin with minimal sugar decomposition, leading to highly fermentable hydrolysates [26]. | Soaking in 18% ammonium hydroxide at 75°C for several hours produced hydrolysates supporting industrial ethanol titers [26]. |

| Ionic Liquids | Green solvent for biomass dissolution. Can effectively solubilize lignin and hemicellulose, but cost and potential inhibition require consideration [26] [22]. | Cholinium lysinate ([Ch][Lys]) pretreated biomass at 140°C; residual IL can inhibit hydrolysis/fermentation if not removed [26]. |

| Ligninolytic Enzymes | Analytical tools to monitor biological pretreatment efficiency and study delignification mechanisms. | Manganese Peroxidase (MnP) and Lignin Peroxidase (LiP) activity assays; MnP was identified as the main contributor in Ex-SSF process [25]. |

| Cellulase & Xylanase Cocktails | Standardized enzyme mixtures for saccharification efficiency testing post-pretreatment. | Commercial blends like Celluclast 1.5L (cellulase) and Novozyme 188 (β-glucosidase); synergistic effect of cellulase/xylanase crucial for high sugar yields [22] [24]. |

| Tau-aggregation-IN-3 | Tau-aggregation-IN-3, MF:C16H17N5O3S2, MW:391.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lumateperone-D4 | Lumateperone-D4, MF:C24H28FN3O, MW:397.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The fundamental goal of pretreating lignocellulosic biomass is the strategic deconstruction of its recalcitrant matrix to render cellulose accessible to enzymatic attack. As evidenced by advanced strategies, success is achieved through the coordinated disruption of lignin-hemicellulose interactions, reduction of cellulose crystallinity, and increase in surface area. The selection and optimization of pretreatment must be tailored to the specific feedstock and integrated seamlessly with downstream enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation processes. Continued research into combined and integrated pretreatment platforms promises to enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and support the sustainable valorization of lignocellulosic biomass in the biorefinery of the future.

Lignocellulosic biomass, derived from agricultural residues, forestry waste, and industrial by-products, represents a key renewable resource for producing biofuels, biochemicals, and bioproducts in the emerging circular bioeconomy. This diverse biomass source is pivotal for reducing reliance on fossil fuels and minimizing environmental impact. The global production of lignocellulose, including agricultural and forestry waste, exceeds 220 billion tons annually, highlighting its immense potential as a sustainable feedstock [17].

The composition of lignocellulose is remarkably consistent across different sources, consisting primarily of cellulose (30-50%), hemicellulose (20-43%), and lignin (15-25%), though the exact proportions vary by feedstock type and origin [17] [27]. This structural complexity, while providing natural resilience in plants, also creates significant challenges for efficient conversion to valuable products, necessitating specialized pretreatment technologies to fractionate these components into usable forms.

Feedstock Composition and Global Availability

Structural Composition of Lignocellulosic Biomass

The three primary components of lignocellulosic biomass form a complex, recalcitrant structure:

Cellulose: A linear polymer of glucose monomers connected by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, forming both crystalline and amorphous regions that provide structural strength [17]. The cellulose content typically ranges from 30% to 50% across different feedstock types [27].

Hemicellulose: A branched, heterogeneous polymer containing xylose, arabinose, mannose, and other sugars, with a lower molecular weight than cellulose and no crystalline regions [17]. It comprises 20-43% of lignocellulosic biomass and is more readily hydrolyzable than cellulose [27].

Lignin: A complex three-dimensional polyphenolic polymer composed of guaiacyl (G), p-hydroxyphenyl (H), and syringyl (S) units that provides structural support and resistance to microbial attack [17]. Lignin acts as the "glue" binding cellulose and hemicellulose through various chemical linkages, creating the recalcitrant nature of plant cell walls [17].

Global Feedstock Availability and Characteristics

Table 1: Global Availability and Composition of Major Lignocellulosic Feedstock Categories

| Feedstock Category | Primary Sources | Global Availability | Cellulose Content | Hemicellulose Content | Lignin Content |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural Residues | Wheat straw, corn stover, rice husks, sugarcane bagasse | Abundant in agricultural regions; wheat straw cellulose ~30% [17] | 30-45% | 20-35% | 15-25% |

| Hardwood Biomass | Birch, poplar, oak (from forestry operations) | Varies by region; strong growth in Northern Europe [28] | 40-50% | 20-30% | 20-25% |

| Softwood Biomass | Spruce, pine, fir (from forestry operations) | Varies by region; dynamic market changes [28] | 40-50% | 25-35% | 25-35% |

| Grasses & Energy Crops | Switchgrass, miscanthus, sugarcane bagasse | Expanding cultivation; sugarcane bagasse used in studies [29] | 30-50% | 20-40% | 10-20% |

| Industrial Waste | Paper pulp, food processing residues, agricultural processing byproducts | Growing with industrial activity; part of 220B tons annual biomass [17] | 30-60% | 15-35% | 10-30% |

The wood and agricultural residues segment dominates feedstock availability, expected to account for 42.7% of the biomass fuel market share in 2025 due to widespread availability and cost-effectiveness [30]. Europe shows strong timber market gains, particularly in Northern and Eastern regions, while Asia Pacific leads in market share with 44.5% of biomass fuel utilization, driven by escalating energy demand and government initiatives [30].

Experimental Protocols for Feedstock Assessment

Protocol 1: Component Analysis of Lignocellulosic Feedstocks

Objective: To quantitatively determine the cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content in diverse lignocellulosic feedstocks.

Materials and Reagents:

- Air-dried, milled feedstock samples (particle size <1mm)

- Sulfuric acid (72% and 3%)

- Sodium hydroxide solution (0.5M)

- Acetone and ethanol for washing

- Crucibles, filtration apparatus, and drying oven

- Analytical balance (precision ±0.0001g)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Mill feedstock to pass through 1mm screen and air-dry to constant weight. Record exact moisture content for dry weight calculations.

Acid Hydrolysis for Structural Carbohydrates:

- Weigh 0.5g of sample (W1) into a digestion tube.

- Add 5mL of 72% H₂SO₄, stir thoroughly, and incubate at 30°C for 1 hour with occasional stirring.

- Dilute to 3% Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ concentration by adding 140mL distilled water.

- Autoclave at 121°C for 1 hour.

- Filter through pre-weighed crucible (W2); retain filtrate for carbohydrate analysis.

- Wash residue with distilled water and dry at 105°C to constant weight (W3).

Lignin Determination:

- Calculate acid-insoluble lignin: (W3 - W2)/W1 × 100%

- Analyze filtrate for acid-soluble lignin by UV spectrophotometry at 205nm.

Carbohydrate Analysis:

- Analyze filtrate for monomeric sugars (glucose, xylose, arabinose, etc.) using HPLC with refractive index detection.

- Convert sugar concentrations to polymeric forms using anhydrous correction factors (0.90 for hexoses, 0.88 for pentoses).

Ash Content:

- Incinerate residue at 575°C for 3 hours; calculate ash percentage.

Protocol 2: Fungal Secretome Analysis for Biomass Degradation

Objective: To profile the enzymatic response of filamentous fungi to different lignocellulosic substrates using quantitative proteomics.

Materials and Reagents:

- Test fungi: Aspergillus terreus, Trichoderma reesei, Myceliophthora thermophila, Neurospora crassa, Phanerochaete chrysosporium [29]

- Substrates: Grass (sugarcane bagasse), hardwood (birch), softwood (spruce), pure cellulose, glucose [29]

- Agar plates with permeable membrane collection system [29]

- Protein extraction and digestion reagents

- LC-MS/MS system for proteomic analysis

- CAZy database for carbohydrate-active enzyme identification [29]

Procedure:

- Fungal Cultivation:

- Grow each fungal strain on agar plates containing different substrates (grass, hardwood, softwood, cellulose, glucose).

- Use plate-based method with permeable membrane to collect cell-free secretomes [29].

- Incubate at optimal temperature for each species until sufficient growth is observed.

Secretome Collection:

- Collect secreted proteins from agar gel below the permeable membrane.

- This method minimizes intracellular protein contamination while capturing substrate-bound proteins [29].

Protein Processing and Analysis:

- Extract proteins and digest with trypsin following standard proteomic protocols.

- Analyze peptide mixtures using LC-MS/MS with quantitative labeling methods.

- Identify proteins by searching against fungal genome databases.

Data Analysis:

- Compare protein abundance across species and substrates.

- Identify carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), including glycoside hydrolases (GHs), carbohydrate esterases (CEs), and lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs) [29].

- Correlate enzyme expression patterns with substrate composition.

Visualization of Feedstock Assessment Workflow

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Feedstock Assessment Workflow

Advanced Pretreatment Methodologies

Protocol 3: Comparative Pretreatment Efficiency Assessment

Objective: To evaluate and compare the effectiveness of different pretreatment methods on various feedstocks.

Materials and Reagents:

- Uniformly prepared feedstock samples

- Chemicals for different pretreatment methods:

- Dilute acid (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„, 0.5-2%)

- Alkali (NaOH, 0.5-2%)

- Ionic liquids (e.g., 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate)

- Deep eutectic solvents (e.g., choline chloride-urea)

- Autoclave or pressurized reactors

- pH adjustment reagents

- Enzymatic hydrolysis reagents: commercial cellulase and hemicellulase cocktails

Procedure:

- Pretreatment Application:

- Apply 5 different pretreatment methods to each feedstock type in triplicate:

- Dilute Acid: 1% H₂SO₄, 160°C, 30 minutes

- Alkali: 1% NaOH, 121°C, 60 minutes

- Steam Explosion: 200°C, 5 minutes followed by rapid decompression

- Ionic Liquid: 10% biomass loading in [Câ‚‚Câ‚im][OAc], 120°C, 6 hours

- Biological: Fungal pretreatment with P. chrysosporium, 28°C, 21 days

- Apply 5 different pretreatment methods to each feedstock type in triplicate:

Post-Pretreatment Processing:

- Neutralize pH of liquid fractions where applicable.

- Wash solid fractions thoroughly with distilled water.

- Separate solid and liquid fractions; analyze both.

Efficiency Assessment:

- Determine solid mass recovery after each pretreatment.

- Analyze composition of pretreated solids.

- Quantify sugar monomers and degradation products in liquid fractions.

- Perform enzymatic hydrolysis of pretreated solids (1% substrate loading, 50°C, 72 hours).

- Calculate sugar yield and conversion efficiency.

Inhibitor Formation and Mitigation

Pretreatment processes generate by-products that act as inhibitors, including:

- Acetic acid: From acetyl group cleavage in hemicellulose [17]

- Furfural and HMF: From dehydration of pentoses and hexoses under high temperature and acidic conditions [17]

- Phenolic compounds: From lignin degradation [17]

Table 2: Inhibitor Profiles Across Pretreatment Methods and Feedstocks

| Pretreatment Method | Primary Inhibitors Generated | Agricultural Residues | Hardwood | Softwood | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dilute Acid | Furfural, HMF, acetic acid, phenolics | High furfural, moderate HMF | Moderate furfural, high HMF | Low furfural, moderate HMF | Overliming, activated charcoal, microbial detoxification |

| Alkaline | Phenolics, organic acids, limited sugars | Low sugar degradation | Moderate phenolics | High phenolics | Washing, extraction, adsorption resins |

| Steam Explosion | Furfural, HMF, acetic acid, phenolics | Moderate inhibitors | High inhibitors | Very high inhibitors | Venting, water washing, laccase treatment |

| Ionic Liquid | Minimal inhibitors if properly recycled | Very low | Very low | Very low | Solvent purification, nanofiltration |

| Biological | Minimal additional inhibitors | Very low | Very low | Low | Optimization of fungal strains |

These inhibitors negatively impact downstream processes by inhibiting enzymatic activity, disrupting microbial cell membranes, and causing fermentation toxicity, ultimately reducing bioresource yields [17]. Mitigation approaches include physical (evaporation, membrane filtration), chemical (overliming, extraction), and biological (microbial or enzymatic detoxification) methods [17].

Industrial Applications and Conversion Pathways

Diagram 2: Feedstock Conversion Pathways to Final Products

Major chemical companies, including BASF, Clariant, Covestro, LyondellBasell, and SUEZ, are backing research projects focused on direct conversion of waste into chemicals via sustainable routes [31]. The Global Impact Coalition (GIC) is collaborating with ETH Zurich to address key scientific and technical challenges in waste-to-chemicals conversion, including processing heterogeneous waste materials and integrating new feedstocks into existing chemical value chains [31].

Direct conversion technologies show particular promise for turning complex waste streams into valuable C2+ chemical compounds such as ethylene and propylene via gasification [31]. These compounds, conventionally produced from fossil-based feedstocks, are essential for producing everyday materials like plastics, detergents, paints, and textiles [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Lignocellulosic Feedstock Research

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Standards | Cellobiose, glucose, xylose, arabinose, furfural, HMF, phenolic compounds | HPLC/UPLC calibration for quantitative analysis | Purity >98%, prepare fresh solutions regularly |

| Enzyme Cocktails | Commercial cellulases (Cellic CTec), hemicellulases, lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases (LPMOs) | Enzymatic saccharification efficiency testing | Activity standardization, optimal temperature/pH profiling |

| Pretreatment Chemicals | Sulfuric acid, sodium hydroxide, ammonia, ionic liquids, deep eutectic solvents | Biomass fractionation and delignification | Concentration optimization, recycling potential, inhibitor formation |

| Microbial Strains | Trichoderma reesei, Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Enzyme production, lignin degradation, fermentation | Growth medium optimization, temperature requirements |

| Chromatography Supplies | HPLC columns (Aminex HPX-87P, HPX-87H), SPE cartridges, filters | Sugar, acid, and inhibitor analysis | Column temperature control, mobile phase preparation |

| Process Monitoring | DNA stains, protein assays, enzyme activity kits | Biomass degradation progression tracking | Standard curve preparation, interference minimization |

| Iperoxo | Iperoxo, MF:C10H17N2O2+, MW:197.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| MO-I-1100 | MO-I-1100, MF:C17H14ClNO5S, MW:379.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The toolkit must be tailored to specific feedstock characteristics, as different fungi demonstrate specialized adaptation to substrates. For example, quantitative proteomic analysis reveals that fungi secrete tailored enzyme mixtures when grown on grass (sugarcane bagasse), hardwood (birch), or softwood (spruce) [29]. The white-rot basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium secretes a wide range of oxidative and hydrolytic enzymes specifically adapted for degrading lignocellulosic biomass [29].

The global feedstock potential from agricultural residues, forestry waste, and industrial byproducts represents a substantial resource for sustainable biorefining operations. Understanding the compositional variations, structural characteristics, and appropriate pretreatment methodologies for each feedstock type is fundamental to optimizing conversion processes and maximizing product yields.

Future research directions should focus on:

- Feedstock-Specific Optimization: Developing tailored pretreatment protocols that account for the unique compositional and structural features of different feedstocks.

- Inhibitor Management: Implementing integrated strategies to minimize inhibitor formation during pretreatment and develop robust microbial strains tolerant to existing inhibitors.

- Technology Integration: Combining biochemical and thermochemical conversion platforms to maximize resource utilization from diverse feedstocks.

- Circular Systems: Designing processes that utilize waste streams from one conversion step as inputs for other processes, mimicking the Global Impact Coalition's approach to direct waste conversion into chemical feedstocks [31].

As the field advances, the integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence approaches for predictive modeling of feedstock behavior and conversion efficiency will become increasingly valuable for optimizing biorefinery operations across the diverse spectrum of available lignocellulosic resources.

A Toolkit for Disassembly: Comparing Physical, Chemical, Biological, and Integrated Pretreatment Methods

Lignocellulosic biomass (LCB), the most abundant renewable organic resource on earth, represents a crucial feedstock for sustainable bioenergy and bioproduct production within the circular bioeconomy framework [17] [18]. With an annual global production exceeding 220 billion tons—including agricultural residues, forestry waste, and dedicated energy crops—LCB offers a low-cost, carbon-neutral alternative to fossil resources [17] [32]. However, its inherent recalcitrance, primarily imposed by the protective lignin matrix and crystalline cellulose structure, presents a significant challenge for conversion into fermentable sugars and value-added products [18] [20].

Pretreatment is a critical initial step in lignocellulosic biorefineries, accounting for up to 40% of total processing costs [33] [34]. Effective pretreatment disrupts the robust lignocellulosic structure, removes lignin, reduces cellulose crystallinity, increases surface area and porosity, and enhances enzymatic accessibility to carbohydrate polymers [17] [20]. Among various approaches, physical pretreatment methods provide distinct advantages, including no inhibitor formation, rapid processing, and environmental friendliness, though they may involve high energy consumption and specific equipment requirements [33] [34]. This application note details three key physical pretreatment technologies—mechanical comminution, ultrasound, and gamma irradiation—providing structured protocols and analytical data to guide researchers in implementing these methods.

Comparative Analysis of Physical Pretreatment Methods

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Physical Pretreatment Methods

| Parameter | Mechanical Comminution | Ultrasound | Gamma Irradiation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanisms | Particle size reduction via shear/impact forces; reduces crystallinity & polymerization [33] [34] | Acoustic cavitation: bubble formation & implosion generating micro-jets & shear forces [35] | Radical formation via ionization; polymer scission & depolymerization [36] |

| Key Operational Parameters | Milling type, speed (e.g., 250-400 rpm), duration, final particle size (e.g., 53-75 µm) [33] | Frequency (18-100 kHz), power (e.g., 100 W), duration, solvent flow (continuous systems) [35] | Radiation dose (e.g., 10-500 kGy), dose rate, biomass moisture, atmosphere [37] [36] |

| Impact on Biomass Structure | ↑ Specific surface area; ↓ Cellulose crystallinity & degree of polymerization [34] | Disrupts lignin structure; creates microscopic channels; ↑ enzymatic accessibility [35] | Cleaves glycosidic bonds; degrades lignin & hemicellulose; ↑ digestibility [36] |

| Typical Sugar Yield Improvements | Glucose yield: 78.7% (sugarcane bagasse); 89.7% (eucalyptus) [33] | Glucose yield increase up to 355% (corn stover) [35] | Varies with biomass & dose; 4-fold increase in reducing sugar (rice straw) [36] |

| Scalability & Energy Considerations | High energy consumption; industrially established but often combined with other methods to reduce energy cost [33] [20] | Challenges with power distribution & reactor design; continuous flow systems improve scalability [35] | Requires specialized, safe irradiation facilities (e.g., Cobalt-60 source); high capital cost [38] [36] |

| Inhibitor Generation | Negligible; no chemical byproducts [33] | Negligible; avoids furfurals & HMF [35] | Negligible; no chemical byproducts [38] |

| Ass234 | Ass234, MF:C29H37N3O, MW:443.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| (R,R)-Suntinorexton | (R,R)-Suntinorexton, MF:C23H28F2N2O4S, MW:466.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Table 2: Biomass-Specific Performance of Physical Pretreatment Methods

| Biomass Type | Pretreatment Method | Key Operational Conditions | Outcome & Sugar Yield | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn Stover | Gamma Irradiation | 2% NaOH pre-treatment + γ-irradiation ( unspecified dose) | Significant cellulose degradation; enhanced glucose recovery for bioethanol [37] | |

| Sugarcane Bagasse | Ball Milling | Ball milling at 250 rpm | Significant particle size reduction; improved enzymatic accessibility [33] | |

| Eucalyptus Wood | Ball Milling | Ball milling at 400 rpm for 120 min | Glucose saccharification yield of 89.7% [33] | |

| Rice Straw | Combined (Milling + γ-irradiation) | Milling, autoclaving, & γ-irradiation (70 Mrad) | Increased yield of total reducing sugar after pretreatment and saccharification [36] | |

| Pea Pods | Ultrasound | Continuous ultrasound bath (frequency & power unspecified) | Effective lignin removal; enhanced biomass valorization [35] | |

| Switchgrass | Low-Intensity Ultrasound | 20 kHz for 72 h | Sugar yield increased to 93% during enzymatic hydrolysis [35] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Mechanical Comminution via Ball Milling

Principle: This protocol employs a ball mill to reduce particle size through impact and shear forces generated by the motion of grinding media, effectively decreasing cellulose crystallinity and increasing surface area for enzymatic attack [33] [34].

Materials:

- Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., sugarcane bagasse, corn stover)

- Ball mill (e.g., planetary ball mill, vibratory mill)

- Sieves (e.g., 30-mesh, 100-mesh)

- Mechanical grinder (for initial size reduction)

- Moisture analyzer

- Safety equipment (gloves, dust mask, hearing protection)

Procedure:

- Biomass Preparation: Air-dry raw biomass to a constant weight. Use a mechanical grinder for initial coarse shredding to a particle size of approximately 1-2 cm.

- Loading: Load the pre-processed biomass into the ball mill's grinding jar, filling it typically to one-third of its volume. Add the grinding balls (e.g., stainless steel, ceramic), ensuring a recommended biomass-to-ball mass ratio between 1:10 and 1:20.

- Milling: Securely close the grinding jar and operate the ball mill at a defined speed (e.g., 250-400 rpm) for a predetermined duration (e.g., 30-120 minutes). The optimal time depends on the initial biomass and desired final particle size.

- Cooling: If the milling duration is long, implement intermittent cycles (e.g., 10 minutes milling, 5 minutes pause) to prevent excessive heat buildup, which can degrade biomass components.

- Harvesting: Carefully open the jar and separate the milled biomass from the grinding balls using a sieve.

- Characterization: Sieve the milled powder to determine particle size distribution. Analyze the product for moisture content, crystallinity index (via X-ray Diffraction), and specific surface area (via BET analysis) [33].

Notes: Milling speed and time are critical for energy efficiency. Combining ball milling with subsequent chemical or thermal pretreatment can significantly enhance overall effectiveness and reduce total energy consumption [20].

Protocol: Ultrasound Pretreatment Using a Continuous Bath System

Principle: This protocol utilizes a continuous ultrasound bath, where low-frequency ultrasonic waves (18-100 kHz) induce acoustic cavitation in a liquid medium. The implosion of cavitation bubbles generates localized extreme temperatures and pressures, along with micro-jets and shear forces that physically disrupt the lignocellulosic structure and create microscopic channels [35].

Materials:

- Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., pea pods, corn stover)

- Continuous flow ultrasound bath (e.g., 5 L capacity, frequency 20-40 kHz)

- Solvent reservoir and pump system (for continuous solvent replenishment)

- Thermostat to control processing temperature

- Filtration or centrifugation setup

Procedure:

- Biomass Preparation: Dry and mill the biomass to a standardized particle size (e.g., pass through a 30-mesh sieve) to ensure uniform exposure.

- Slurry Preparation: Prepare a biomass-liquid slurry at a defined solid loading (e.g., 5-10% w/v) using an appropriate solvent (e.g., water, buffer). The solvent choice depends on the target biomass components.

- System Priming: Fill the ultrasound bath with the solvent and activate the continuous flow system from the reservoir to ensure fresh solvent circulation, preventing saturation with dissolved extractives.

- Sonication: Immerse the biomass slurry container in the bath or feed the slurry directly through the flow cell. Treat the biomass at a defined ultrasonic frequency (e.g., 20 kHz) and power (e.g., 100 W) for a set duration (e.g., 30 minutes). Maintain a constant temperature (e.g., 30-50°C) using the thermostat.

- Processing: After treatment, terminate ultrasound and stop the flow system.

- Separation: Recover the pretreated biomass by filtration or centrifugation. Wash the solid residue with clean solvent to remove any dissolved compounds and air-dry for further analysis or enzymatic hydrolysis [35].

Notes: The continuous flow design is superior to static baths as it prevents solvent saturation with inhibitors, maintaining pretreatment efficiency. Key parameters to optimize are frequency, power, treatment time, and solid loading.

Protocol: Gamma Irradiation Pretreatment

Principle: This protocol uses high-energy gamma photons from a radioactive source (e.g., Cobalt-60) to irradiate biomass. The ionizing radiation creates radicals within the lignocellulosic polymers, leading to chain scission, depolymerization of cellulose and hemicellulose, and modification/delignification of the cell wall, thereby increasing its digestibility [37] [36].

Materials:

- Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn stover, rice straw)

- Gamma irradiation facility (Cobalt-60 or Cesium-137 source)

- Sealed containers or bags for sample holding

- Dosimetry system to measure absorbed dose

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) or other chemicals for combined pretreatment

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Air-dry biomass to a constant weight and grind to a uniform particle size (e.g., pass through a 30-mesh sieve). For wet irradiation, adjust the moisture content to a specific level (e.g., 50-70%).

- Optional Alkali Pre-treatment (for combined method): To enhance irradiation efficacy, pre-treat biomass with a mild alkali solution (e.g., 2% w/v NaOH) at moderate temperature (e.g., 80°C) for 1-2 hours. This pre-treatment removes some lignin and hemicellulose, exposing more cellulose to radiation [37].

- Packaging: Weigh a specific amount of biomass (e.g., 100 g) and pack it into sealed containers or bags, ensuring a uniform thickness for consistent radiation penetration.

- Irradiation: Place the samples in the gamma irradiation chamber. Irradiate at a predetermined dose (e.g., 10-500 kGy). The required dose depends on biomass type and moisture content; wet biomass often requires significantly lower doses (e.g., 10 kGy) than dry biomass for the same effect [36].

- Dosimetry: Use a calibrated dosimeter to verify the actual absorbed dose.

- Post-Irradiation Handling: After irradiation, safely retrieve the samples. The pretreated biomass can be directly subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis or further processed [37] [36].

Notes: Combining gamma irradiation with chemical pretreatment (e.g., with alkali or urea) often has a synergistic effect, allowing for lower radiation doses and higher sugar yields. Safety protocols for handling irradiated materials must be strictly followed.

Visualization of Pretreatment Workflow

Diagram 1: Workflow of Physical Pretreatment Methods. This diagram illustrates the parallel application of three physical pretreatment methods on raw lignocellulosic biomass, their primary mechanisms of action, and the common outcome of producing pretreated biomass amenable to enzymatic hydrolysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Physical Pretreatment Research

| Item | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Planetary Ball Mill | High-energy reduction of particle size and cellulose crystallinity [33] | Look for controllable speed (e.g., 100-600 rpm) and various grinding jar materials (e.g., agate, stainless steel). |

| Ultrasound Bath (Continuous Flow) | Induces cavitation for biomass disintegration; continuous flow prevents solvent saturation [35] | Optimal frequency range 20-40 kHz; ensure temperature control and flow pump integration. |

| Cobalt-60 Irradiation Source | Gamma ray source for polymer scission and depolymerization of biomass components [36] | Housed in specialized, shielded facilities; dose rate and uniformity are critical parameters. |

| Standardized Biomass Powder | Ensures consistent, comparable results across pretreatment experiments [37] | Prepare by drying and milling to specific particle size (e.g., 20-60 mesh); store in dry conditions. |

| Dosimetry System | Measures absorbed radiation dose during gamma irradiation for process validation [36] | Includes chemical or physical dosimeters calibrated for the relevant dose range (kGy). |

| Milling Balls (Grinding Media) | Imparts mechanical energy for size reduction in ball milling [33] | Available in various materials (e.g., zirconia, stainless steel) and diameters; selection affects energy input. |

| 1-Octanol-d5 | 1-Octanol-d5, MF:C8H18O, MW:135.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ganglioside GM1-binding peptides p3 | Ganglioside GM1-binding peptides p3, MF:C86H135N23O18, MW:1779.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Lignocellulosic biomass (LCB), primarily composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, represents a vast and sustainable carbon source for producing biofuels and biobased chemicals [18]. However, its inherent recalcitrance, stemming from the complex cross-linked network of these polymers, poses a significant challenge to efficient bioconversion [39] [17]. Pretreatment is therefore a critical first step in any biorefinery process, aimed at disrupting this robust structure, removing lignin, and increasing the accessibility of cellulose and hemicellulose for subsequent enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation [40] [41].

Among the various pretreatment strategies, chemical methods are highly effective. This application note provides a detailed overview of four prominent chemical pretreatment technologies: acid, alkali, ionic liquids (ILs), and deep eutectic solvents (DES). It summarizes their mechanisms, operational parameters, and advantages, and provides standardized protocols to aid researchers in their implementation.

Mechanism and Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Chemical Pretreatment Methods

| Pretreatment Method | Primary Mechanism | Key Operational Parameters | Impact on Biomass Components | Key Advantages | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acid | Hydrolyzes hemicellulose to xylose and other sugars; disrupts lignin structure [17]. | - Acid type (e.g., H₂SO₄, HCl) - Concentration (e.g., 0.05-0.15 g/g biomass) [42] - Temperature (e.g., 121°C for DLCA) [42] - Time (e.g., 15-60 min) [42] | - Solubilizes hemicellulose - Alters lignin structure - Exposes cellulose [17] | - Effective for high hemicellulose biomass - High sugar recovery [17] | - Equipment corrosion - Inhibitor formation (e.g., furfural, HMF) [17] - Negative ash buffering effect [42] |

| Alkali | Disrupts lignin structure by breaking ester and glycosidic side chains; solubilizes lignin [17] [43]. | - Alkali type (e.g., NaOH, Ca(OH)₂) - Concentration (e.g., 1-5% w/w NaOH) [43] - Temperature (e.g., 90°C) [43] - Time (e.g., 15-60 min) [43] | - Significant delignification - Solubilizes some hemicellulose - Swells cellulose [43] | - Effective delignification - Lower inhibitor formation vs. acid [43] | - Long processing times - Salt generation - Positive ash buffering effect [42] |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Dissolves biomass by disrupting hydrogen bonding and lignocellulosic matrix [44] [45]. | - IL type (e.g., [Emim][OAc], [TEA][HSOâ‚„]) - Temperature (varies) - Solid loading - Time | - Dissolves lignin and hemicellulose - Can decrystallize cellulose [45] | - High solvation power - Tunable properties - Low volatility [45] | - High cost - Challenges in recovery/recycle (<97% target) [45] - Potential toxicity [45] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Similar to ILs; disrupts lignin and hemicellulose matrix via hydrogen bonding [43]. | - DES composition (HBD/HBA) - Molar ratio - Temperature - Time | - Selective delignification - Dissolves hemicellulose [43] | - Lower cost than ILs - Biodegradable components - Low toxicity [43] | - High viscosity - Emerging recovery methods - Long pretreatment times possible |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data from Recent Studies

| Pretreatment Method | Biomass Feedstock | Optimal Conditions | Key Performance Outcomes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkali (NaOH) | Xyris capensis (energy grass) | 4% w/w NaOH, 90°C, 20 min | Biomethane Yield: 328.20 mL CH₄/gVSadded (143% increase over untreated) | [43] |

| Alkali (Ca(OH)â‚‚) | Mixed substrate for Pleurotus ostreatus cultivation | 8% Ca(OH)â‚‚, room temperature | Fruiting Body Yield: 28.30% increase Biological Efficiency: 18.47% increase | [39] |

| Ionic Liquid (EMIAc) | Date Palm Waste Biomass (Pedicels) | 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([Emim][OAc]) | Biomethane Potential (BMP): ~200 mL CHâ‚„/g VS (higher than ammonia pretreatment) | [44] |

| Deep Eutectic Solvent | Corn Stover | 1:2 solid-to-liquid ratio, 100°C, 60 min | Biomethane Yield: 48% improvement | [43] |

| DLCA (Densifying with Chemicals + Autoclave) | Corn Stover | H₂SO₄ or Ca(OH)₂, 121°C autoclave | Sugar Concentration: Up to 255 g/L after enzymatic hydrolysis Ethanol Production: Up to 66.5 g/L | [42] |

The Role of Ash Content

The inorganic ash content (3-20%) in biomass significantly influences pretreatment efficacy. Ash exerts a buffering capacity that can neutralize acid or alkali catalysts [42]. In acid pretreatment, high ash content consumes the acid, reducing the available catalyst and leading to lower delignification and digestibility. Conversely, in alkali pretreatment, the basic anions in ash can complement the process, with studies showing a positive correlation between ash content and enzymatic digestibility after alkali pretreatment [42]. Pre-washing biomass to reduce ash content can be a crucial step for optimizing acid-based pretreatments.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Alkali (NaOH) Pretreatment for Enhanced Biomethane Production

This protocol is adapted from the pretreatment of Xyris capensis for anaerobic digestion [43].

Principle: Sodium hydroxide disrupts the lignin structure, swells the cellulose, and removes acetyl groups from hemicellulose, enhancing enzymatic accessibility.

Materials:

- Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., energy grass, straw)

- Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) pellets

- Autoclave

- Heating mantle or water bath

- pH meter

- Filtration setup

- Drying oven

Procedure:

- Feedstock Preparation: Mill the biomass to a particle size of 1-2 mm and dry at 60°C to constant weight.

- NaOH Solution Preparation: Prepare a 4% (w/w) NaOH solution in distilled water.

- Pretreatment Reaction: Mix the biomass with the NaOH solution at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 (w/v). Load the mixture into a sealed reactor.

- Heating: Heat the mixture to 90°C and maintain for 20 minutes with constant stirring.

- Neutralization and Washing: After the reaction, cool the mixture and neutralize the slurry to a pH of ~7.0 using a dilute acid (e.g., HCl).

- Solid Recovery: Filter the neutralized slurry to separate the pretreated solid residue. Wash the solid residue thoroughly with distilled water to remove any residual salts and inhibitors.

- Analysis: The solid fraction can be analyzed for composition changes or used directly for enzymatic hydrolysis and subsequent anaerobic digestion.

Protocol: Acid Densification with Autoclave (DLCA) Pretreatment

This protocol is based on the DLCA (Densifying Lignocellulosic biomass with acidic Chemicals and Autoclave) process for high-solids loading biorefining [42].

Principle: Concentrated acid is evenly distributed and densified with the biomass, followed by a mild autoclave step to efficiently break down the lignocellulosic structure with low energy consumption and inhibitor formation.

Materials:

- Lignocellulosic biomass (e.g., corn stover)

- Sulfuric acid (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„, 98%)

- Densification machine (e.g., pellet press)

- Autoclave

- pH meter

Procedure:

- Chemical Addition: Uniformly mix the biomass with sulfuric acid at a dosage of 0.05-0.15 g per gram of dry biomass.

- Densification: Immediately densify the acid-impregnated biomass using a pellet press to achieve a high-bulk-density solid.

- Storage/Transport: The densified biomass is stable and can be stored or transported without risk of microbial contamination.

- Autoclave Treatment: Subject the densified pellets to steam autoclaving at 121°C for a specified duration (e.g., 20-60 minutes).

- Hydrolysis Readiness: The resulting DLCA-pretreated biomass can be directly used for high-solids enzymatic hydrolysis without extensive washing, yielding very high sugar concentrations.

Workflow Visualization

Chemical Pretreatment Workflow for Lignocellulosic Biomass

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Chemical Pretreatment

| Item | Specification / Example | Primary Function in Pretreatment |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfuric Acid (Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Concentrated (98%), analytical grade | Catalyst for hemicellulose hydrolysis and lignin alteration in acid pretreatment [42]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Pellets or solution, analytical grade | Alkali agent for breaking lignin bonds and solubilizing lignin [43]. |

| Calcium Hydroxide (Ca(OH)â‚‚) | Powder, technical or analytical grade | A cheaper alkali alternative for delignification, often used in agricultural applications [39]. |

| Ionic Liquids | e.g., 1-Ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([Emim][OAc]) | Solvent for dissolving lignocellulosic components; tunable for selective fractionation [44] [45]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | e.g., Choline Chloride:Urea (1:2) | Green solvent for selective delignification and hemicellulose removal [43]. |

| Lignocellulosic Biomass | Milled and sieved to 1-2 mm particle size | Standardized feedstock to ensure consistent pretreatment results across experiments. |

| Enzyme Cocktails | Cellulases, Hemicellulases (e.g., from Trichoderma reesei) | For saccharification of pretreated biomass to evaluate pretreatment efficiency [41]. |

| Neutralizing Agents | e.g., HCl for alkali slurry, NaOH for acid slurry | To adjust pH of pretreated biomass to optimal range for downstream enzymatic or microbial processes [43]. |

| PDK1-IN-3 | PDK1-IN-3, MF:C25H15N5, MW:385.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| DN5355 | DN5355, MF:C11H7N3OS2, MW:261.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Biological delignification using fungi and bacteria presents an environmentally friendly pretreatment strategy for lignocellulosic biomass within biorefinery processes. Unlike energy-intensive thermal, chemical, or physico-chemical methods, biological pretreatment utilizes microbial enzymes to selectively degrade the recalcitrant lignin polymer that protects cellulose and hemicellulose in plant cell walls [46] [47]. This approach significantly reduces energy consumption, requires minimal chemical inputs, and generates fewer inhibitory by-products that can hinder subsequent saccharification and fermentation stages [20] [17]. The integration of biological delignification into lignocellulosic biomass valorization is therefore pivotal for developing sustainable, cost-effective biorefining systems aligned with circular bioeconomy principles [5].

The fundamental objective of biological delignification is to disrupt the complex lignin-carbohydrate matrix, thereby enhancing enzyme accessibility to structural polysaccharides during enzymatic hydrolysis [47]. Successful pretreatment increases biomass porosity, exposes cellulose fibers, and ultimately improves reducing sugar yields for biofuel production [20]. While biological methods typically require longer incubation times compared to conventional pretreatments, their economic and environmental advantages make them a compelling research focus, particularly when integrated with complementary pretreatment technologies in combined approaches [20] [25].

Microbial Agents for Delignification

Fungal Systems

White-rot fungi (WRF) represent the most efficient lignin-degrading microorganisms in nature, producing powerful extracellular lignin-modifying enzymes [46] [48]. These fungi are categorized based on their decay patterns: selective delignifiers that preferentially degrade lignin over carbohydrates, and simultaneous rot fungi that degrade all lignocellulose components concurrently [48].

Table 1: Key White-Rot Fungi for Biological Delignification

| Fungal Species | Decay Type | Key Enzymes | Delignification Efficiency | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceriporiopsis subvermispora | Selective | Manganese peroxidase (MnP), lignin peroxidase (LiP) | 31.6% lignin removal in corn stover in 35 days [48] | Preferred for pretreatment; minimal cellulose loss [48] |

| Phanerochaete chrysosporium | Simultaneous | Lignin peroxidase (LiP), manganese peroxidase (MnP) | 51.4% delignification of corn stover in 30 days [48] | High delignification but significant cellulose loss [48] |

| Trametes versicolor | Simultaneous | Laccase, manganese peroxidase (MnP) | 12% lignin decrease in bamboo after 120 days [48] | Moderate delignification capacity [48] |

| Lentinula edodes | Selective | Lignin-modifying enzymes | Extensive lignin degradation with carbohydrate preservation [49] | Improves nutritive value for ruminant feed [49] |

| Pleurotus eryngii | Selective | Lignin-modifying enzymes | Extensive lignin degradation with carbohydrate preservation [49] | Effective for agricultural residues [49] |

Bacterial and Actinomycete Systems

Various bacterial species, particularly actinomycetes such as Streptomyces, also exhibit lignin-degrading capabilities, although they are generally less efficient than white-rot fungi [50] [47]. These microorganisms produce lignocellulolytic enzyme systems that can attack, depolymerize, and degrade lignin polymers [47]. Bacterial pretreatment offers potential advantages including faster growth rates and easier cultivation compared to fungal systems [47]. For instance, treatment of hardwood residues with Streptomyces griseus isolated from leaf litter resulted in 23.5% lignin loss while also producing high levels of cellulase complexes [47].

Enzymatic Mechanisms of Delignification

Microorganisms employ specialized enzyme systems to break down the complex, heterogeneous structure of lignin. The primary enzymes involved belong to the following classes:

- Lignin Peroxidases (LiP): Heme-containing peroxidases that catalyze the oxidative cleavage of non-phenolic lignin subunits, which constitute approximately 90% of the lignin polymer [50] [48].

- Manganese Peroxidases (MnP): Heme-peroxidases that utilize Mn²⺠as a redox mediator to oxidize phenolic lignin structures [50] [48].

- Laccases: Multi-copper oxidases that catalyze the oxidation of phenolic lignin units using molecular oxygen as an electron acceptor [50] [48].

- Versatile Peroxidases (VP): Hybrid enzymes with combined catalytic properties of both MnP and LiP, capable of degrading phenolic and non-phenolic lignin units [50].

These enzymes operate synergistically with accessory enzymes and mediators to disrupt the complex lignin matrix through radical-based reaction mechanisms [50]. Fungal systems often deploy these enzymes within multi-enzyme complexes called cellulosomes, which enhance degradation efficiency up to 50-fold compared to freely-secreted enzymes by maintaining enzyme proximity and substrate channeling [50].

Diagram 1: Enzymatic Pathways in Microbial Delignification. This diagram illustrates the targeted action of different lignin-modifying enzymes on specific structural units within the lignin polymer, resulting in various degradation products.

Experimental Protocols

Fungal Pretreatment of Lignocellulosic Biomass

Principle: This protocol utilizes white-rot fungi to selectively degrade lignin in lignocellulosic biomass, thereby enhancing enzymatic saccharification yield for biofuel production. The method is adapted from established procedures with corn stover and woody biomass [25] [48].

Materials: