Advanced Neural Networks for Higher Heating Value (HHV) Prediction: From Foundational Concepts to Research Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of artificial neural networks (ANNs) for predicting the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of fuels and biomass, a critical parameter in energy system design.

Advanced Neural Networks for Higher Heating Value (HHV) Prediction: From Foundational Concepts to Research Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of artificial neural networks (ANNs) for predicting the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of fuels and biomass, a critical parameter in energy system design. Tailored for researchers and scientists, the content spans from foundational principles to advanced methodological applications. It systematically covers the optimization of network architectures and training algorithms, compares the performance of various machine learning models against traditional methods, and validates approaches using robust, large-scale datasets. The review synthesizes current trends and future directions, offering a valuable resource for professionals aiming to implement accurate and efficient HHV prediction models in bioenergy and sustainable fuel research.

Understanding HHV and the Fundamental Role of Neural Networks in Prediction

Defining Higher Heating Value (HHV) and Its Critical Importance in Energy Systems

The Higher Heating Value (HHV), also known as the gross calorific value, represents the total amount of heat released when a specified quantity of fuel undergoes complete combustion with oxygen under standard conditions, and the combustion products are cooled back to the original pre-combustion temperature (typically 25°C) [1] [2]. This measurement includes the recovery of the latent heat of vaporization contained in the water vapor produced during combustion, meaning the water component is condensed to liquid state at the process end [1] [3]. The HHV defines the upper limit of available thermal energy producible from complete fuel combustion and serves as the true representation of a fuel's total chemical energy content [1] [2].

In energy systems, the HHV contrasts fundamentally with the Lower Heating Value (LHV), which describes the useful heat available when water vapor from combustion remains uncondensed and exits the system in gaseous form [1] [4]. The distinction arises because the combustion of hydrogen-rich fuels (particularly those containing hydrogen or moisture) produces water that subsequently evaporates in the combustion chamber, a process that "soaks up" some of the heat released by fuel combustion [3]. This temporarily lost heat—the latent heat of vaporization—does not contribute to work done by the combustion process unless specifically recovered through condensation [3].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between HHV and LHV

| Characteristic | Higher Heating Value (HHV) | Lower Heating Value (LHV) |

|---|---|---|

| Water State in Products | Liquid | Vapor |

| Latent Heat Recovery | Included | Not Included |

| Energy Content | Higher | Lower |

| Typical Applications | Systems with flue-gas condensation, theoretical energy content | Internal combustion engines, boilers without secondary condensers |

| Measurement Reference Temperature | 25°C (77°F) | 150°C (302°F) or 25°C with vaporization adjustment |

Theoretical Foundations and Calculation Methodologies

Thermodynamic Principles

The theoretical foundation for HHV centers on the enthalpy change between reactants and products during complete combustion. By definition, the heat of combustion (ΔH°comb) represents the heat of reaction for the process where a compound in its standard state completely combusts to form stable products in their standard states: carbon converts to carbon dioxide gas, hydrogen converts to liquid water, and nitrogen converts to nitrogen gas [1]. Mathematically, the relationship between HHV and LHV can be expressed as:

HHV = LHV + H~v~(n~H₂O,out~/n~fuel,in~) [1]

where H~v~ represents the heat of vaporization of water at the datum temperature (typically 25°C), n~H₂O,out~ is the number of moles of water vaporized, and n~fuel,in~ is the number of moles of fuel combusted [1].

For hydrocarbon fuels, the complete combustion reaction follows the general form:

C~c~H~h~N~n~O~o~ (std.) + (c + h⁄4 - o⁄2) O~2~ (g) → cCO~2~ (g) + h⁄2H~2~O (l) + n⁄2N~2~ (g) [1]

This stoichiometric relationship provides the basis for calculating both theoretical and experimental heating values.

Experimental Determination Protocols

Bomb Calorimetry Method

The primary method for experimental determination of HHV utilizes a bomb calorimeter, which operates under standardized conditions (ASTM D-2015) [1] [2]. The detailed experimental protocol involves:

Apparatus Setup: Prepare a sealed steel combustion chamber (bomb) capable of withstanding high pressures, oxygen supply system, ignition unit, precision temperature measurement system, and water jacket with regulated temperature control [1].

Sample Preparation: Precisely weigh a representative fuel sample (typically 0.5-1.5g) and place it in the sample cup within the bomb. For homogeneous fuels, a single sample may suffice, but heterogeneous fuels require multiple representative samples to ensure accuracy [1].

Combustion Initiation: Pressurize the bomb with pure oxygen to approximately 30 atm to ensure complete combustion. Initiate the reaction using an electrical ignition system. The combustion of a stoichiometric mixture of fuel and oxidizer produces water vapor as a primary product [1].

Heat Measurement: Allow the vessel and its contents to cool back to the original 25°C reference temperature. Measure the temperature change of the surrounding water jacket with precision instrumentation. Account for heat contributions from auxiliary materials like ignition wires [1].

Calculation: Apply the temperature correction factor and calculate the heat capacity of the system to determine the total heat released per unit mass of fuel, which represents the experimentally determined HHV [1].

The critical aspect of HHV measurement is ensuring all water vapor produced during combustion fully condenses, thereby capturing the latent heat of vaporization that distinguishes HHV from LHV [1].

Computational Determination Using Cantera

For fuels where experimental measurement is impractical, computational thermodynamics provides an alternative approach. The Cantera software platform enables calculation of both HHV and LHV using thermodynamic data [5]. The protocol involves:

Reactant State Definition: Initialize the fuel-oxidizer mixture at standard reference conditions (298K, 1 atm) with stoichiometric oxygen for complete combustion [5].

Enthalpy Calculation: Compute the enthalpy of reactants prior to combustion using appropriate thermodynamic models (e.g., ideal gas mixture) [5].

Product State Definition: Define the complete combustion products composition (CO~2~, H~2~O, N~2~) and calculate their combined enthalpy at the same temperature and pressure [5].

Water Phase Adjustment: For HHV, account for the enthalpy difference between gaseous and liquid water states using non-ideal equation of state models [5].

Result Normalization: Calculate the heating value by dividing the negative enthalpy change by the mass fraction of fuel in the initial mixture [5].

Table 2: Experimentally Determined Heating Values for Common Fuels

| Fuel | HHV (MJ/kg) | LHV (MJ/kg) | Percentage Difference | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen (H₂) | 141.78 [5] | 119.95 [5] | 18.2% [1] | Fuel cells, rocket propulsion |

| Methane (CH₄) | 55.51 [5] | 50.03 [5] | 10.9% [1] | Natural gas systems, heating |

| Ethane (C₂H₆) | 51.90 [5] | 47.51 [5] | 9.2% [1] | Chemical feedstock, fuel blending |

| Propane (C₃H₈) | 50.34 [5] | 46.35 [5] | 8.6% [1] | Portable heating, transportation |

| Methanol (CH₃OH) | 23.85 [5] | 21.10 [5] | 12.9% [1] | Alternative fuels, fuel cells |

| Ammonia (NH₃) | 22.48 [5] | 18.60 [5] | 20.6% [1] | Carbon-free fuel, hydrogen carrier |

Predictive Equations and Empirical Correlations

For biomass and solid fuels, several empirical correlations enable HHV estimation from compositional data. The Dulong Formula provides a fundamental approach:

HHV [kJ/g] = 33.87m~C~ + 122.3(m~H~ - m~O~/8) + 9.4m~S~ [1]

where m~C~, m~H~, m~O~, and m~S~ represent the mass fractions of carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, and sulfur, respectively, on any basis (wet, dry, or ash-free) [1].

A more comprehensive unified correlation developed by Channiwala and Parikh (2002) applies to diverse fuel types:

HHV = 349.1C + 1178.3H + 100.5S - 103.4O - 15.1N - 21.1ASH (kJ/kg) [2]

where C, H, S, O, N, and ASH represent percentages of carbon, hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, nitrogen, and ash from ultimate analysis on a dry basis [2]. This correlation remains valid within the ranges: 0 < C < 92%, 0.43 < H < 25%, 0 < O < 50%, 0 < N < 5.6%, and 0 < ASH < 71% [2].

Neural Networks for HHV Prediction: Advanced Methodologies

ANN Architecture for Biomass HHV Prediction

Recent advances in Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in predicting HHV values from proximate analysis data, achieving superior performance compared to traditional empirical correlations [6]. The optimal ANN architecture identified for wood biomass HHV prediction employs a 4-11-11-11-1 structure, featuring:

Input Layer: Four neurons corresponding to proximate analysis parameters: moisture content (M), volatile matter (VM), ash content (A), and fixed carbon (FC) [6]

Hidden Layers: Three hidden layers with 11 neurons each, utilizing nonlinear activation functions to capture complex relationships between biomass properties and heating values [6]

Output Layer: Single neuron generating the predicted HHV value [6]

Training Algorithm: Backpropagation with optimization to minimize prediction error between experimental and calculated HHVs [6]

This ANN architecture achieved an exceptional adjusted R² value of 0.967 with low mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean squared error (RMSE) values when trained on 252 wood biomass samples from the Phyllis database (177 training, 75 testing) [6]. The model significantly outperformed 26 existing empirical and statistical models in both accuracy and generalization capability [6].

Data Preparation and Feature Analysis

The development of robust ANN models requires comprehensive data preparation and understanding of feature correlations:

Data Sourcing: The Phyllis database (maintained by TNO Biobased and Circular Technologies) provides standardized physicochemical properties of diverse biomass types [6]

Feature Selection: Proximate analysis parameters (moisture, volatile matter, ash, fixed carbon) serve as optimal inputs due to their strong correlation with HHV and relative ease of measurement compared to ultimate analysis [6]

Correlation Analysis: Pearson correlation coefficients reveal strong positive relationships between fixed carbon and HHV (p-value ≈ 0.836), and strong negative correlation between ash content and HHV (p-value = -0.856) [6]

Data Partitioning: Appropriate training-testing splits (typically 70:30) ensure model generalizability beyond the training dataset [6]

Implementation and Validation Protocol

The implementation of ANN models for HHV prediction follows a rigorous validation protocol:

GUI Development: Creation of user-friendly graphical interfaces for real-time HHV prediction across diverse biomass types [6]

Cross-Validation: Employ k-fold cross-validation techniques to assess model stability and prevent overfitting [6]

Benchmarking: Compare ANN predictions against established empirical models (Boie, Dulong, Moot-Spooner, Grummel-Davis, IGT) originally developed for coal but commonly applied to biomass [6]

Error Metrics: Utilize multiple validation metrics including adjusted R², Pearson correlation coefficient (r), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean squared error (RMSE) [6]

Explainability Enhancement: Implement feature importance analysis and correlation heatmaps to interpret model decisions and enhance researcher trust in predictions [6]

Practical Applications in Energy Systems

Efficiency Calculations and System Design

The selection between HHV and LHV as reference values fundamentally impacts efficiency calculations and system design across energy technologies:

Condensing Boilers and Power Plants: Systems equipped with flue-gas condensation technology can recover latent heat from water vapor, making HHV the appropriate benchmark for calculating true thermal efficiency. These systems can potentially achieve efficiency values exceeding 100% when calculated using LHV, violating First Law of Thermodynamics principles if not properly referenced [2] [3]

Internal Combustion Engines: Conventional engines without secondary condensers cannot utilize the latent heat in water vapor, making LHV the correct basis for efficiency calculations and performance projections [1] [4]

Fuel Cell Systems: High-temperature fuel cells (molten carbonate, solid oxide) achieve electrical efficiencies exceeding 60% based on LHV, outperforming comparable combustion-based systems. Their ability to utilize internal heat for steam reforming further enhances effective efficiency [7]

Combined Heat and Power (CHP): Systems that recover waste heat for thermal applications achieve significantly higher overall efficiency when calculated using HHV, particularly when recovered heat displaces separate fuel consumption in boilers [7]

Commercial and Regulatory Implications

The choice between HHV and LHV carries significant commercial and regulatory consequences:

Fuel Billing and Trading: Natural gas suppliers typically bill customers based on HHV measurements, as this represents the total available energy content delivered. This practice provides economic advantage to suppliers while potentially disadvantaging consumers whose equipment cannot utilize the latent heat component [4] [7]

Efficiency Reporting Standards: Regional differences exist in efficiency reporting conventions, with North American systems typically using HHV while many European countries use LHV. This creates challenges in cross-border technology comparisons and requires careful attention to the basis of efficiency claims [2]

Emissions Calculations: Accurate carbon accounting and emissions intensity calculations require proper HHV/LHV alignment, as the same physical process will show different efficiency and therefore different emissions per unit output depending on the heating value basis used [8]

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for HHV Determination

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Specifications | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bomb Calorimeter | Experimental HHV measurement | ASTM D-2015 compliant, 30 atm oxygen capability, precision temperature sensor | Laboratory fuel characterization |

| Ultimate Analyzer | Elemental composition determination | Measures C, H, O, N, S percentages with ±0.3% accuracy | Empirical correlation input data |

| Proximate Analyzer | Moisture, volatile matter, ash, fixed carbon measurement | TGA-based, ±0.2% repeatability | ANN model input parameter generation |

| Cantera Software | Thermodynamic calculation of HHV/LHV | Open-source platform with detailed species databases | Computational fuel analysis |

| Phyllis Database | Biomass property reference | 252+ validated biomass samples with full characterization | ANN training and validation dataset |

| MATLAB with ANN Toolbox | Neural network development and training | Deep Learning Toolkit, neural network fitting app | Custom predictive model implementation |

The precise definition and application of Higher Heating Value remains fundamental to energy system design, efficiency optimization, and accurate fuel characterization across research and industrial contexts. While traditional determination methods like bomb calorimetry provide experimental measurements, emerging artificial neural network approaches demonstrate superior predictive capability from proximate analysis data, achieving remarkable accuracy (R² = 0.967) in biomass HHV prediction. The integration of these computational methods with thermodynamic fundamentals enables researchers and engineers to optimize energy systems with unprecedented precision, particularly as renewable biomass fuels gain prominence in sustainable energy strategies. Proper understanding of the distinction between HHV and LHV, along with consistent application in efficiency calculations, remains essential for meaningful cross-system comparisons and advancement of energy technologies.

The Limitations of Traditional Experimental Measurement and Empirical Correlations

The accurate determination of the Higher Heating Value (HHV) is a fundamental prerequisite in designing efficient bioenergy systems and evaluating solid fuel quality for energy applications [9]. For researchers, scientists, and development professionals, the traditional pathways for obtaining this critical parameter—direct experimental measurement and empirical correlations—present significant limitations that can hinder research progress and application scalability. This application note details these constraints, framing them within the advancing context of neural network-based prediction as a robust alternative. The inherent complexity and variability of biomass composition, further compounded in diverse waste streams like municipal solid waste (MSW), makes accurate HHV estimation a non-trivial challenge that traditional methods struggle to address consistently [9] [10].

Limitations of Traditional Experimental Measurement

The conventional method for HHV determination is direct measurement using an adiabatic oxygen bomb calorimeter [11] [12]. While this technique is considered a standard, it is beset with practical limitations that impact its utility in modern, high-throughput research and development environments.

Practical and Operational Constraints

The bomb calorimetry process is time-consuming and expensive, requiring specialized equipment and controlled laboratory conditions [11] [9]. This creates a significant barrier to accessibility, particularly for researchers in developing nations [11]. Furthermore, the method requires a small, representative sample mass (around 1 gram), which poses a major challenge for accurately representing the substantial volume and heterogeneity of materials like Municipal Solid Waste (MSW) [10]. The results are also susceptible to various experimental errors, and the entire procedure is not conducive to rapid iteration or large-scale screening of potential fuel feedstocks [10].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Bomb Calorimetry for HHV Determination

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on Research & Development |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Intensity | Time-consuming procedures; high equipment costs [11] [9] | Slows research progress; creates accessibility barriers |

| Sample Representation | Difficulty in obtaining a small mass representative of heterogeneous materials like MSW [10] | Questions the validity and scalability of results for real-world feedstocks |

| Operational Factors | Susceptibility to experimental error; lack of infrastructure in many facilities [10] | Introduces uncertainty and limits widespread adoption for routine analysis |

Visual Workflow of Traditional Experimental Measurement

The following diagram illustrates the complex and resource-intensive workflow required for traditional experimental HHV measurement, highlighting points where limitations are introduced.

Limitations of Empirical Correlations

To circumvent the challenges of direct measurement, numerous empirical correlations have been developed to predict HHV from more easily obtained data, such as proximate analysis (moisture, ash, volatile matter, fixed carbon) and ultimate analysis (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur) [9] [12]. Despite their convenience, these models possess fundamental flaws.

Inherent Model Inadequacies

The relationship between biomass composition and its HHV is inherently nonlinear and complex [9] [12]. Traditional analytical equations, often linear or polynomial, fail to capture these intricate relationships, leading to a lack of accuracy and generality across a wide range of biomass feedstocks [9]. A recent study benchmarking a neural network model against 54 published analytical correlations found that the neural network achieved substantially higher R² and lower prediction error than any fixed-form formula [9]. These models often rely on a single type of analysis (proximate or ultimate), neglecting the complementary information that a combined dataset provides [9].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of HHV Prediction Models

| Model Type | Example Models / Techniques | Reported Performance (R²) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Empirical Correlations | 54 Published linear & polynomial models [9] | Lower than ANN/ML models [9] | Computational simplicity; fast estimation | Fails to capture nonlinearity; lacks generality & accuracy [9] |

| Machine Learning (Tree-Based) | Random Forest (RF), XGBoost, Extra Trees [11] [10] | RF Test R²: >0.94 [10]XGBoost Test R²: 0.7309 [11]Extra Trees Test R²: 0.979 [10] | High accuracy; handles complex relationships | Requires significant computational power & data |

| Neural Networks (NN) | Backpropagation ANN, Elman RNN [9] [12] | ANN Validation R²: ≈0.81 [9]ENN Test R: 0.82255 [12] | Superior with nonlinearity; high predictive accuracy | "Black box" nature; requires large datasets & tuning [9] |

Visual Workflow and Limitations of Empirical Models

The workflow for developing and applying empirical correlations, while simpler than experimental methods, contains inherent bottlenecks that limit predictive performance.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To contextualize the discussion, this section outlines standard protocols for both traditional measurement and modern data-driven approaches to HHV determination.

Protocol 1: Traditional HHV Measurement via Bomb Calorimetry

This protocol is based on standardized ASTM methods [9].

- Sample Preparation: The biomass sample is first air-dried and then ground to a uniform particle size of 1 mm using a mill.

- Representative Sampling: A small mass (approximately 1 gram) of the prepared sample is precisely weighed. For heterogeneous materials, this step is critical and may require homogenization of a larger quantity before sub-sampling.

- Calorimeter Setup: The weighed sample is placed in a crucible inside the bomb of an IKA Werke C 5000 control calorimeter (or equivalent). The bomb is pressurized with excess oxygen to 25-30 atmospheres.

- Combustion and Measurement: The bomb is placed in a water-filled container equipped with a precise thermometer. The sample is ignited electrically, and the subsequent temperature rise of the water is measured.

- Calculation: The HHV (on a dry basis in MJ/kg) is calculated based on the measured temperature change, the heat capacity of the system, and the mass of the sample, in accordance with ASTM E711 [9].

Protocol 2: Developing a Neural Network Model for HHV Prediction

This protocol details the methodology for creating a Backpropagation Artificial Neural Network (ANN) model, as described in recent literature [9].

- Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Compile a dataset of biomass samples with known HHV (measured via bomb calorimetry) and their corresponding proximate and ultimate analyses [9].

- Preprocess the data by removing outliers (e.g., samples with implausible HHV values) [9].

- Normalize all input (e.g., M, A, VM, FC, C, H, O, N, S) and output (HHV) data to a consistent range (e.g., [0.1, 0.9]) to ensure stable and efficient network training [9].

- Model Architecture and Training:

- Define the network architecture. A proven configuration is a 9-6-6-1 structure (9 inputs, two hidden layers with 6 neurons each, 1 output) [9].

- Set the hyperparameters: learning rate (e.g., 0.3), momentum (e.g., 0.4), and number of training epochs (e.g., 15,000) [9].

- Use a nonlinear activation function like the logistic sigmoid for all neurons.

- Split the dataset into training (~75%) and testing (~25%) sets.

- Train the network using the backpropagation algorithm to minimize the error between predicted and actual HHV values.

- Model Validation and Sensitivity Analysis:

- Validate the model's performance on the unseen test set, reporting metrics like R², Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Mean Squared Error (MSE) [9].

- Perform a sensitivity analysis (e.g., Index of Relative Importance) to interpret the model and confirm that learned relationships (e.g., HHV increases with carbon content) are chemically intuitive [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Analytical Techniques for HHV Research

| Item / Technique | Function in HHV Research | Relevance / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bomb Calorimeter | Directly measures the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of a solid fuel sample via combustion in an oxygen-rich environment [9]. | Gold-standard method for generating experimental HHV data; required for validating predictive models. |

| Proximate Analyzer | Determines bulk fuel properties: Moisture (M), Ash (A), Volatile Matter (VM), and Fixed Carbon (FC) content using standardized thermogravimetric methods [12]. | Provides key input features for both empirical correlations and machine learning models. Faster and less expensive than ultimate analysis [12]. |

| Elemental Analyzer | Conducts ultimate analysis to determine the elemental composition of biomass: Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H), Nitrogen (N), Sulfur (S), and Oxygen (O) content [9]. | Provides fundamental chemical input data for more accurate HHV prediction models. |

| Data Preprocessing Tools | Software for data normalization, outlier detection, and dataset partitioning (training/test sets) [9]. | Critical step for preparing high-quality datasets to ensure robust and reliable machine learning model development. |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Software libraries (e.g., Python's Scikit-learn, TensorFlow) for implementing algorithms like ANN, XGBoost, and Extra Trees [11] [9] [10]. | Enables the development of high-accuracy, nonlinear predictive models that surpass the capabilities of traditional empirical equations. |

Traditional pathways for HHV determination are fraught with constraints. Experimental measurement via bomb calorimetry is resource-intensive and impractical for large-scale screening, while empirical correlations suffer from a fundamental lack of accuracy and generalizability due to their inability to model complex, nonlinear relationships [11] [9] [10]. Within the context of modern bioenergy and waste valorization research, these limitations are increasingly unacceptable. The emergence of data-driven approaches, particularly neural networks and other machine learning models, represents a paradigm shift. These models, which leverage combined proximate and ultimate analysis data, have demonstrated superior predictive performance, offering a computationally efficient, robust, and highly accurate alternative for rapid HHV estimation, thereby accelerating research and development in sustainable energy [9] [12].

Theoretical Foundations of Artificial Neural Networks

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are computational models inspired by the biological nervous systems of the human brain, designed to solve complex data-driven problems by learning from predefined datasets [13]. As universal approximators, ANNs can represent a wide variety of interesting functions when given appropriate parameters, with theoretical foundations established by the Universal Approximation Theorem [14]. This theorem states that a feed-forward network with a single hidden layer containing a finite number of neurons can approximate any Borel measurable function from one finite-dimensional space to another with any desired non-zero amount of error, provided the network has enough hidden units [14]. This property makes ANNs particularly valuable for modeling the complex, non-linear relationships prevalent in scientific domains, including biomass energy research for Higher Heating Value (HHV) prediction.

The fundamental processing unit of an ANN is the artificial neuron, which receives inputs, applies mathematical operations, and produces an output [13]. Key components include: Inputs (the set of features fed into the model), Weights (parameters that determine the importance of each feature), Transfer Function (combines multiple inputs into one output value), Activation Function (introduces non-linearity to handle varying linearity with inputs), and Bias (shifts the value produced by the activation function) [13]. When multiple neurons are stacked together in a row, they constitute a layer, and multiple layers piled next to each other form a multi-layer neural network [13].

ANN architectures are broadly categorized by their connection patterns. Feed-Forward Neural Networks represent the simplest architecture where information moves in only one direction—from input nodes through hidden nodes (if any) to output nodes, without any cycles or loops [13]. More sophisticated architectures include Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) which contain cycles and can maintain an internal state, making them suitable for sequential data processing, and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) which are particularly effective for processing grid-like data such as images [13]. The design of neural network architectures involves careful consideration of depth (number of layers) and width (number of units per layer), with deeper networks generally capable of achieving complex tasks with fewer units per layer but potentially more difficult to optimize [14].

ANN Applications in Biomass HHV Prediction

The application of ANNs for predicting biomass Higher Heating Value represents a significant advancement over traditional linear and empirical modeling approaches. Accurate HHV estimation is crucial for evaluating biomass's energy potential as a renewable energy material and for designing efficient bioenergy systems [6] [9]. Conventional experimental methods to determine biomass heating value are laborious and costly, creating a need for reliable predictive models [15] [9].

Traditional correlations based on proximate analysis (moisture, ash, volatile matter, fixed carbon) or ultimate analysis (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur) often rely on linear or polynomial relationships that fail to capture the complex, non-linear nature of biomass properties [6] [9]. ANN models address this limitation by learning directly from input data without assuming a predetermined functional structure, enabling them to model the intricate relationships between biomass composition and energy content with remarkable accuracy [9].

Multiple studies have demonstrated the superiority of ANN approaches for HHV prediction. A comprehensive study predicting the HHV of 350 biomass samples from proximate analysis found that ANNs trained with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm achieved the highest accuracy, providing improved prediction accuracy with higher R² and lower RMSE compared to previous models [15]. Another study developed a backpropagation ANN using both proximate and ultimate analysis data from 99 diverse Spanish biomass samples, achieving validation R² ≈ 0.81 and mean squared error ≈ 1.33 MJ/kg—representing a substantial improvement over 54 traditional analytical models [9].

Recent research has also explored feature selection to optimize ANN inputs for HHV prediction. One study combining feature selection scenarios and machine learning tools justified that volatile matter, nitrogen, and oxygen content of biomass samples have slight effects on HHV and could potentially be ignored during modeling [16]. The multilayer perceptron neural network emerged as the best predictor for biomass HHV, presenting outstanding absolute average relative error of 2.75% and 3.12% and regression coefficients of 0.9500 and 0.9418 in the learning and testing stages [16].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ANN Models for Biomass HHV Prediction

| Study Focus | Data Size | Input Variables | Optimal Architecture | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General Biomass HHV Prediction [15] | 350 samples | Proximate analysis | Not specified | Highest R² with Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm |

| Spanish Biomass Samples [9] | 99 samples | Proximate + Ultimate analysis (9 inputs) | 9-6-6-1 | Validation R² ≈ 0.81, MSE ≈ 1.33 MJ/kg |

| Wood Biomass [6] | 252 samples | Proximate analysis | 4-11-11-11-1 | Adjusted R² of 0.967 |

| Feature Selection Study [16] | 532 samples | Selected features | Multilayer Perceptron | R² of 0.9500 (learning), 0.9418 (testing) |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Collection and Preprocessing Protocol

The foundation of any successful ANN model lies in rigorous data collection and preprocessing. For biomass HHV prediction, data typically comes from standardized laboratory measurements of biomass properties. One study sourced 252 wood biomass samples from the Phyllis database, which compiles physicochemical properties of lignocellulosic biomass and related feedstocks [6]. Another study utilized 99 distinct Spanish biomass samples including commercial fuels, industrial waste, energy crops, and cereals, with complete proximate and ultimate analysis values obtained following ASTM guidelines [9].

Data preprocessing follows a systematic protocol to ensure model robustness:

- Data Cleaning: Identify and remove outliers that may distort model training. For instance, one study removed vegetal coal with an extremely high HHV value that was physically implausible and inconsistent with the rest of the dataset [9].

- Data Normalization: Apply min-max normalization to rescale all inputs and outputs to a standardized range (typically [0.1, 0.9]) to prevent large differences in value magnitudes and facilitate numerical stability during training [9]. The normalization formula used is: ( Xn = \frac{X - X{\text{min}} \times 0.8}{X{\text{max}} - X{\text{min}}} + 0.1 ), where ( X ) is the original value, ( X{\text{min}} ) and ( X{\text{max}} ) are the minimum and maximum values of the feature, and ( X_n ) is the normalized value [9].

- Data Splitting: Partition the dataset into training and testing subsets, typically using a 75%/25% split, ensuring both sets preserve the overall distribution of HHV and compositional variables [9].

ANN Architecture Design and Training Protocol

The design of ANN architecture requires careful consideration of multiple factors:

- Input Layer Configuration: Determine the number of input neurons based on selected features. Studies have used varying inputs ranging from 4 proximate analysis parameters [6] to 9 combined proximate and ultimate analysis parameters [9].

- Hidden Layers Design: Experiment with different numbers of hidden layers and neurons per layer. Common practice involves testing architectures with 1-3 hidden layers, with neurons ranging from 6 to 20 per layer [6] [9]. One study found optimal performance with a 4-11-11-11-1 architecture for wood biomass HHV prediction [6], while another identified a 9-6-6-1 architecture as optimal for diverse Spanish biomass samples [9].

- Activation Function Selection: Choose appropriate activation functions to introduce non-linearity. The logistic sigmoid function is well-suited for continuous regression problems with normalized objectives and is commonly used in multilayer neural networks for HHV prediction [9].

- Training Algorithm Selection: Select supervised learning algorithms for network training. The Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm has demonstrated superior performance for feed-forward backpropagation in HHV prediction, showing the best fit with highest R and R² values and lowest error metrics [15].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize hyperparameters including learning rate (typically 0.3) and momentum (typically 0.4) through analytical tuning based on iterative performance evaluation [9].

The training process involves using the backpropagation algorithm to adjust connection weights to minimize prediction error, with model validation performed using performance metrics such as adjusted R², Pearson r, MAE, and RMSE [6].

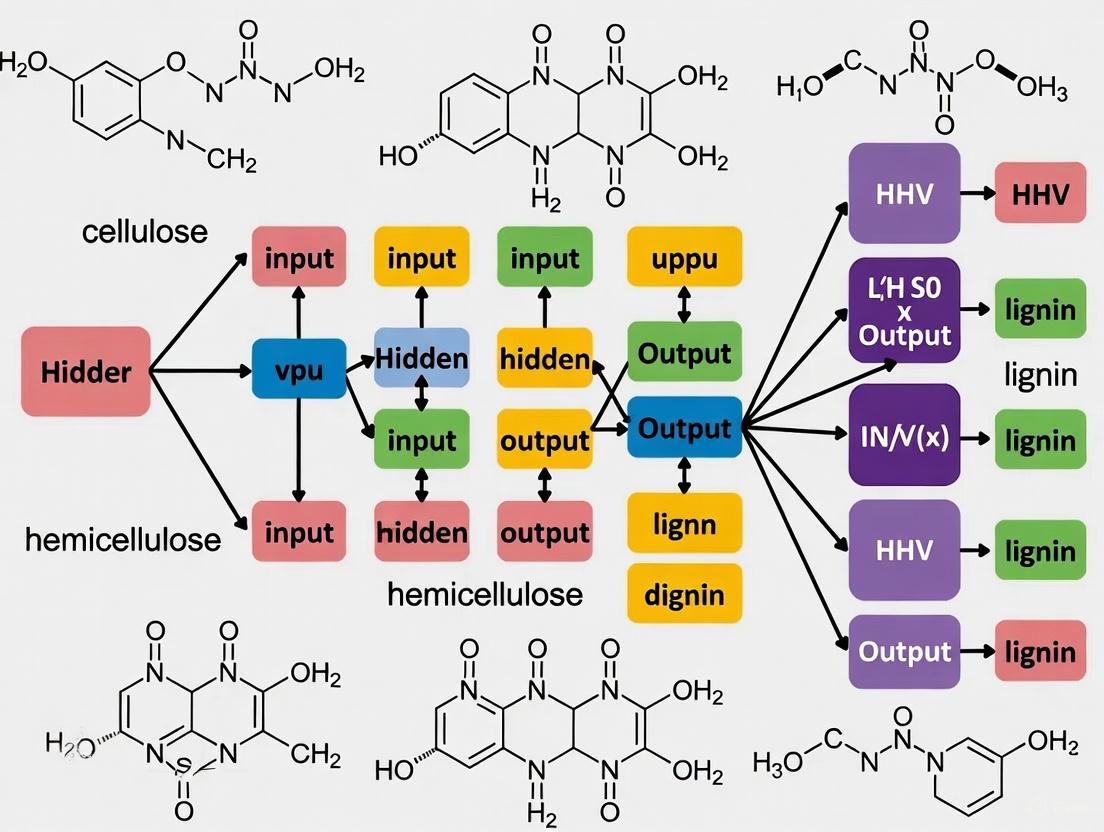

ANN Architecture for HHV Prediction

Advanced Implementation Considerations

Feature Selection and Optimization

Advanced ANN implementations for HHV prediction incorporate sophisticated feature selection techniques to optimize model performance. Research indicates that combining feature selection scenarios with machine learning tools establishes more general models for estimating biomass HHV [16]. Multiple linear regression and Pearson's correlation coefficients can identify parameters with slight effects on HHV, such as volatile matter, nitrogen, and oxygen content, which might be ignored during modeling to improve efficiency [16].

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithms integrated with ANNs provide powerful multi-objective optimization capabilities for biochar production metrics, simultaneously optimizing yield, HHV, and carbon content across diverse feedstocks [17]. This approach converts feature importance into nonlinear thresholds and actionable operating windows for thermochemical processes, demonstrating the potential of hybrid methodologies that combine predictive models with evolutionary optimization [17].

Model Validation and Interpretation

Robust validation protocols are essential for ensuring ANN model reliability. Beyond standard training-testing splits, rigorous 5-fold cross-validation helps identify optimal architectures that balance accuracy and generalizability [17]. Sensitivity analysis through tools like Index of Relative Importance (IRI) can quantify each input's influence on HHV prediction, enhancing model interpretability and confirming chemically intuitive trends [9].

Recent studies have incorporated explainability tools such as SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) and partial-dependence plots to interpret ANN predictions, addressing the common criticism of neural networks as "black boxes" [17]. These approaches help validate that models learn meaningful fuel-property relationships, such as the expected positive correlations between carbon content/fixed carbon and HHV, and negative correlations between ash content and HHV [6] [9].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ANN-Based HHV Prediction

| Category | Specific Tool/Technique | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Phyllis Database [6] | Provides standardized physicochemical data for diverse biomass samples |

| Experimental Protocols | ASTM Standards [9] | Ensure consistent measurement of proximate/ultimate analysis parameters |

| Analysis Instruments | Bomb Calorimeter [9] | Empirically determines HHV values for model training and validation |

| Feature Selection | Pearson Correlation [16] | Identifies most influential biomass parameters for HHV prediction |

| Optimization Algorithms | Levenberg-Marquardt [15] | Training algorithm for feedforward-backpropagation networks |

| Validation Methods | k-Fold Cross-Validation [17] | Assesses model generalizability across different data subsets |

| Implementation Tools | MATLAB GUI [6] | Provides user-friendly interface for real-time HHV prediction |

Workflow for ANN-Based HHV Prediction

Successful implementation of ANN models for HHV prediction requires specific technical considerations. The computational framework typically involves mathematical operations represented by: ( Z = \sum w x + b ), where ( x ) is the input signal, ( w ) is the weight vector, and ( b ) is the bias term that specifies the neuron's output [16]. Activation functions transform this combined input, with common choices including linear functions (( \Psi(Z) = Z )), radial basis functions (( \Psi(Z) = \exp(-0.5 \times Z^2 / s^2) )), logarithmic sigmoid (( \Psi(Z) = 1 / (1 + \exp(-Z)) )), and hyperbolic tangent sigmoid (( \Psi(Z) = 2 / (1 + \exp(-2 \times Z)) - 1 )) [16].

Training efficiency depends on appropriate hyperparameter configuration. Studies have successfully used learning rates of 0.3, momentum of 0.4, and training durations of 15,000 epochs to achieve convergence [9]. Network architectures vary by application, with research demonstrating optimal performance using configurations such as 4-11-11-11-1 (4 inputs, 3 hidden layers with 11 neurons each, 1 output) for wood biomass [6], and 9-6-6-1 (9 inputs, 2 hidden layers with 6 neurons each, 1 output) for diverse biomass samples [9].

Implementation platforms range from specialized MATLAB software [6] to custom-developed graphical user interfaces (GUIs) that enable real-time HHV prediction across diverse biomass types [6] [9]. These tools enhance accessibility and practical application of ANN models in both research and industrial settings, facilitating the transition from experimental models to operational decision-support systems for bioenergy applications.

The accurate prediction of the Higher Heating Value (HHV) is a cornerstone in developing efficient bioenergy systems. As a key metric defining the energy content of biomass, HHV is traditionally measured via bomb calorimetry, a precise but time-consuming and costly experimental method [16] [9]. The pursuit of alternative predictive methodologies has positioned machine learning, particularly Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), as a powerful tool for estimating HHV from biomass compositional data [17] [6].

The central question in constructing these data-driven models is the selection of input variables. The primary candidates are parameters from proximate analysis (moisture, ash, volatile matter, and fixed carbon) and ultimate analysis (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur content) [18] [9]. Proximate analysis offers a practical, rapid characterization of fuel behavior during thermal conversion, while ultimate analysis provides fundamental insights into the elemental composition governing combustion energy release [18] [16]. This Application Note systematically explores the application of these two analytical approaches as inputs for ANN-based HHV prediction, providing a structured comparison of their performance and practical guidance for researchers in the field of biomass energy.

Comparative Analysis of Input Variable Sets

The choice between proximate and ultimate analysis, or their combination, significantly influences the predictive accuracy, computational complexity, and practical feasibility of an HHV model. The table below summarizes the core parameters, advantages, and limitations of each approach.

Table 1: Comparison of Proximate and Ultimate Analysis for HHV Modeling

| Aspect | Proximate Analysis Inputs | Ultimate Analysis Inputs | Combined Analysis Inputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Parameters | Moisture (M), Ash (A), Volatile Matter (VM), Fixed Carbon (FC) [6] | Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H), Oxygen (O), Nitrogen (N), Sulfur (S) [16] | All parameters from both analyses (e.g., M, A, VM, FC, C, H, O, N, S) [9] |

| Primary Advantages | - Faster and less expensive analysis [16]- Directly related to thermal conversion behavior [6] | - Fundamentally linked to energy content via bond energies [18]- High predictive potential | - Provides the most comprehensive feedstock characterization [9]- Typically achieves the highest model accuracy [17] |

| Key Limitations | - May capture less of the fundamental energy relationship compared to elemental data [16] | - Ultimate analysis can be more costly and complex than proximate analysis [16] | - Maximizes data acquisition cost and time- Increased model complexity and risk of overfitting |

| Reported Model Performance | ANN R² up to 0.967 [6] | Superior performance over proximate-only models in comparative studies [16] | ANN Validation R² ≈ 0.81, outperforming 54 analytical models [9] |

Experimental Protocols for HHV Modeling

Data Sourcing and Preprocessing Protocol

A critical first step in developing a robust ANN model is the assembly and preparation of a high-quality dataset.

- Data Acquisition: Source data from publicly available databases such as the Phyllis database (maintained by TNO) or from peer-reviewed literature that provides standardized experimental measurements [6] [9]. The dataset should be curated for a specific biomass type (e.g., wood) to ensure consistency.

- Data Cleaning and Outlier Removal: Examine the dataset for missing values and physiologically implausible outliers. For instance, one study removed a "vegetal coal" sample with an HHV far exceeding typical lignocellulosic biomass ranges to maintain dataset homogeneity [9].

- Data Normalization: Apply feature scaling to preprocess the input data. Min-max normalization is a standard technique that rescales all features to a defined range (e.g., [0.1, 0.9]), preventing features with larger original scales from disproportionately influencing the model and improving training stability [9]. The formula is: ( X{\text{norm}} = \frac{X - X{\text{min}}}{X{\text{max}} - X{\text{min}}} \times (0.9 - 0.1) + 0.1 )

- Data Splitting: Partition the dataset randomly into a training set (~75-80%) for model development and a testing set (~20-25%) for evaluating the model's generalization performance on unseen data [6] [9].

ANN Model Configuration and Training Protocol

The following protocol outlines the process for building and training an ANN for HHV prediction, adaptable for different input variable sets.

- Input Feature Selection: Choose the input variables based on the comparison in Table 1. For a combined model, use all nine parameters from proximate and ultimate analysis (M, A, VM, FC, C, H, O, N, S) [9].

- ANN Architecture Selection: Start with a feedforward network (multilayer perceptron) and experiment with 1 to 3 hidden layers. The number of neurons per layer can be optimized empirically; architectures such as 4-11-11-11-1 (for 4 proximate inputs) and 9-6-6-1 (for 9 combined inputs) have shown high performance [6] [9].

- Activation Function and Training Algorithm: Use the logistic sigmoid function as the non-linear activation function in hidden layers, as it has been demonstrated to yield better predictions than linear functions for HHV modeling [9]. Employ the backpropagation algorithm to train the network by minimizing the prediction error [6] [9].

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Manually tune key hyperparameters. A reported effective configuration includes a learning rate of 0.3, a momentum of 0.4, and training for up to 15,000 epochs [9]. The optimal configuration should be determined by evaluating model performance on a validation set.

- Performance Validation: Validate the final model using the held-out test set. Key performance metrics include the Coefficient of Determination (R²), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). The model's robustness can be further tested via cross-validation and benchmarking against existing empirical correlations [6] [16].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials and Analytical Equipment for HHV Modeling Research

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specifications / Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Biomass Samples | Source material for analysis and model development. | Agricultural residues, forestry outputs, energy crops, organic wastes [9]. |

| Bomb Calorimeter | Experimental measurement of reference HHV values. | IKA Werke C 5000 control; ASTM E711 standard method [9]. |

| Proximate Analyzer | Determination of moisture, ash, volatile matter, and fixed carbon content. | Follows standardized ASTM guidelines [9]. |

| Elemental Analyzer | Determination of ultimate analysis (C, H, N, S, O content). | Standard ASTM-based procedures [9]. |

| Data Analysis Software | For data preprocessing, feature engineering, and machine learning model development. | Python with libraries (e.g., Featuretools), MATLAB [6] [19]. |

Both proximate and ultimate analyses provide a viable foundation for developing ANN models to predict biomass HHV. The choice is a trade-off between analytical cost and predictive accuracy. Proximate analysis offers a practical and cost-effective path for rapid screening, while ultimate analysis, or a combination of both, delivers superior accuracy by capturing the fundamental chemistry of energy content, making it suitable for high-precision applications. Researchers should select their input variables based on the specific requirements of their project, considering the available resources and the desired level of predictive performance. Future work will likely focus on expanding model datasets, incorporating the effects of thermal pretreatments, and enhancing model interpretability to solidify ANNs as an indispensable tool for the bioenergy industry.

The Shift from Linear to Non-Linear Predictive Models in Fuel Characterization

The accurate characterization of fuel properties, such as the Higher Heating Value (HHV), is a critical component in the design and optimization of bioenergy systems and combustion technologies. Traditional reliance on linear models and costly experimental measurements, like bomb calorimetry, has given way to more sophisticated, data-driven approaches. This shift is driven by the recognition that the relationships between fuel composition and its energy content are inherently non-linear and complex. Framed within the broader context of neural network research for HHV prediction, this document details the application protocols and experimental methodologies that enable researchers to leverage non-linear predictive models effectively, ensuring more accurate, efficient, and cost-effective fuel characterization.

From Linear Correlations to Non-Linear Models

The evolution from linear to non-linear modeling represents a paradigm shift in fuel property prediction.

- Limitations of Linear Models: Traditional empirical correlations, often based on linear or polynomial relationships derived from proximate analysis (e.g., fixed carbon, volatile matter, ash) or ultimate analysis (e.g., carbon, hydrogen, oxygen content), have been widely used [12] [9]. While simple to implement, these models often lack accuracy and generalizability across diverse fuel types because they cannot capture the complex, interactive nature of the underlying compositional parameters [9].

- The Non-Linear Advantage: Non-linear machine learning models, particularly Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), excel at modeling these complex relationships without requiring a pre-defined functional form [9]. Research has consistently demonstrated the superiority of non-linear methods. One study concluded that "Nonlinear methods proved their superiority over linear ones," with neural networks being the most suitable for creating a calibration model between near-infrared spectra and gasoline properties [20]. In biomass HHV prediction, ANNs have shown substantially higher accuracy (R² ≈ 0.81-0.95) compared to a wide array of traditional linear correlations [16] [9].

Table 1: Comparison of Model Types for Fuel Property Prediction

| Feature | Linear Models | Non-Linear Models (e.g., ANN) |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Assumes a linear relationship between inputs and output [20] | Capable of learning complex, non-linear interactions [9] |

| Model Complexity | Low (e.g., Multiple Linear Regression) | High (e.g., multilayer perceptron) |

| Handling of Complexity | Poor for sophisticated, multicomponent systems [20] | Robust for systems with intrinsic nonlinearities [20] |

| Typical Performance | Lower accuracy and generalizability [9] | Superior predictive accuracy and robustness [16] [9] |

| Data Efficiency | Requires less data | Requires larger, representative datasets [16] [12] |

Key Non-Linear Models and Performance Data

Various non-linear models have been deployed for fuel characterization. The following table summarizes the performance of several prominent models used for predicting biomass HHV, allowing for direct comparison.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Non-Linear Models for Biomass HHV Prediction

| Model Type | Data Points | Key Input Features | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) ANN | 532 | Proximate & Ultimate Analysis | R²: 0.9500 (learning), 0.9418 (testing); AARD%: 2.75% (learning), 3.12% (testing) [16] | Scientific Reports (2023) |

| Elman Recurrent NN (ENN-LM) | 532 | Proximate & Ultimate Analysis | MAE: 0.67; MSE: 0.96; R: 0.88335 (training) [12] | Int. J. Mol. Sci. (2023) |

| Backpropagation ANN | 99 | Proximate & Ultimate Analysis | R² ≈ 0.81 (validation); MSE ≈ 1.33 MJ/kg; MAE ≈ 0.77 MJ/kg [9] | Energies (2025) |

| Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) | 200 | Proximate & Ultimate Analysis | R²: 0.9683 (training), 0.7309 (test); RMSE: 0.3558 [11] | Scientific Reports (2024) |

| Random Forest (RF) | 200 | Proximate & Ultimate Analysis | High accuracy, excels at capturing non-linear relationships [21] | Scientific Reports (2025) |

Sensitivity analyses on these high-performing models have confirmed chemically intuitive trends, validating their decision-making processes. For instance, increased carbon content and fixed carbon consistently lead to a higher HHV, while higher moisture, ash, and oxygen content reduce it [11] [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: HHV Prediction using ANN

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for developing an Artificial Neural Network to predict the Higher Heating Value (HHV) of biomass fuels from proximate and ultimate analysis data.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Data Collection: Compile a database of biomass samples with known HHV (measured via standard bomb calorimetry, e.g., ASTM E711) and their corresponding compositional analyses [9].

- Input Features: The standard input features are Moisture (M), Ash (A), Volatile Matter (VM), Fixed Carbon (FC), Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H), Nitrogen (N), Sulfur (S), and Oxygen (O) [9].

- Data Cleaning: Remove outliers that are physically implausible or inconsistent with the dataset (e.g., vegetal coal with an extremely high HHV) to maintain dataset homogeneity [9].

- Feature Selection/Optimization: Employ feature selection techniques like Multiple Linear Regression and Pearson’s correlation coefficients to identify and potentially exclude features with a slight effect on HHV, such as volatile matter, nitrogen, and oxygen [16].

Data Normalization: Rescale all input and output values to a uniform range (e.g., [0.1, 0.9]) using min-max normalization. This prevents large differences in value magnitudes and facilitates stable and efficient network training [9]. The formula is:

(Xn = \frac{X - X{min}}{X{max} - X_{min}} \times 0.8 + 0.1)

where (X) is the original value and (Xn) is the normalized value.

- Data Splitting: Split the entire dataset randomly into a training set (~75-80%) for model development and a testing set (~20-25%) for evaluating the model's generalization performance [9].

Neural Network Design and Training

- Architecture Selection: Begin with a feedforward network (e.g., MLP). Start with a single hidden layer and a small number of neurons [22]. The input layer must have as many neurons as there are input features (e.g., 9). The output layer has a single neuron for the HHV prediction [9].

- Topology Tuning: Systematically vary the number of hidden layers (1-5) and neurons per layer (1-100) to find the optimal architecture. The goal is to find a model that is sufficiently complex without overfitting. A common approach is the "overfit, then regularize" method: start with a large network and then apply regularization to reduce overfitting [22]. As per recent studies, architectures like 9-6-6-1 (input-hidden-hidden-output) have proven effective [9].

- Activation Function: For hidden layers, use non-linear activation functions like ReLU, Leaky ReLU, or the logistic sigmoid function, which is well-suited for regression problems with normalized targets [9]. For the output layer, no activation function is typically used for regression, allowing the output to take any value [22].

- Training Algorithm and Hyperparameters:

- Training Algorithm: Use the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm for medium-sized datasets, as it has been shown to yield high accuracy (e.g., MAE of 0.67) [12]. For very large datasets, Scaled Conjugate Gradient (SCG) or other optimizers may be considered.

- Learning Rate and Momentum: Manually tune the learning rate (a common starting point is 0.3) and momentum (a common starting point is 0.4) based on iterative performance evaluation [9]. Using a learning rate finder method is also a recommended practice [22].

- Epochs: Train for a large number of epochs (e.g., 15,000) and employ Early Stopping to halt training when performance on a validation set stops improving, thus preventing overfitting [22] [9].

- Model Evaluation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out testing set using statistical metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Squared Error (MSE), and the Coefficient of Determination (R²) [16] [9].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials, software, and analytical tools required for conducting research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Fuel Characterization and Modeling

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specifications/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Bomb Calorimeter | Experimental measurement of the Higher Heating Value (HHV) for model training and validation. | e.g., IKA Werke C 5000 control; operated per ASTM E711 [9]. |

| Elemental Analyzer | Conducts ultimate analysis to determine the carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur content of fuel samples. | Standard ASTM-based procedures [9]. |

| Proximate Analyzer | Determines moisture, ash, volatile matter, and fixed carbon content following standardized guidelines. | ASTM guidelines [9]. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectrometer | Rapid, non-destructive data collection for building calibration models between spectral data and fuel properties. | Device used for gasoline property prediction [20]. |

| Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs) | Precisely control fuel and air flow rates in combustion characterization experiments. | Sizes selected based on required flow rates (e.g., 40 L/min for CH₄, 200 L/min for air) [23]. |

| Gas Chromatograph (GC) / Mass Spectrometer (MS) | Analysis of combustion exhaust species concentration (e.g., CO, H₂, CO₂) for model fuel development. | Used to characterize fuel-rich combustion exhaust [23]. |

| Neural Network Software Library | Framework for building, training, and evaluating non-linear predictive models. | PyTorch (with PyTorchViz for visualization), Keras (with plot_model utility) [24]. |

Advanced Visualization and Model Interpretation

Understanding how non-linear models, especially neural networks, arrive at their predictions is crucial for their adoption in rigorous scientific research. Techniques like feature visualization and sensitivity analysis are key.

- Feature Visualization: This involves optimizing an input (e.g., creating an image) to maximize a model's response, revealing what the model has learned to detect. A challenge is that optimization can produce "adversarial examples"—nonsensical, high-frequency patterns that the model strongly reacts to. To get useful visualizations, regularization (e.g., imposing naturalistic constraints on the input) is essential to guide the optimization toward interpretable results [25].

- Activation Heatmaps: These are visual representations of the inner workings of a neural network, showing which neurons are activated layer-by-layer. They can identify which parts of the input data the model is sensitive to and reveal regions of the network that rarely activate and could be pruned [24].

- Sensitivity Analysis and IRI: Post-modeling, a sensitivity analysis or Index of Relative Importance (IRI) can be conducted to quantify the influence of each input feature on the predicted HHV, confirming chemically intuitive trends and validating the model's logic [9].

The process for interpreting and debugging a trained model is illustrated below.

Implementing Neural Network Architectures and Feature Engineering for HHV Prediction

In the pursuit of accurate Higher Heating Value (HHV) prediction models for biomass and solid fuels, the selection of input features is a critical step that directly impacts model complexity, generalizability, and performance. Within the broader context of neural network applications for HHV prediction, understanding the relative importance of specific biomass components—particularly volatile matter (VM), nitrogen (N), and oxygen (O)—enables researchers to construct more efficient and robust models. This application note synthesizes current research findings to provide evidence-based protocols for optimal feature selection, helping researchers avoid redundant inputs that contribute minimal predictive value while prioritizing those with significant impact on HHV estimation accuracy.

Key Findings on Feature Significance

Recent comprehensive studies employing feature selection techniques and sensitivity analyses have consistently demonstrated that not all biomass components contribute equally to HHV prediction accuracy. The table below summarizes the quantitative impact of excluding volatile matter, nitrogen, and oxygen content on model performance.

Table 1: Impact of Feature Selection on HHV Prediction Model Accuracy

| Feature | Reported Impact on HHV | Recommended Handling | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volatile Matter (VM) | Slight effect [26] | Consider excluding from models [26] | Multiple linear regression and Pearson’s correlation coefficients justified ignoring VM [26] |

| Nitrogen (N) | Slight effect [26] | Consider excluding from models [26] | Feature selection techniques identified N as less important [26] |

| Oxygen (O) | Slight effect [26]; Reduces HHV [9] | Consider excluding; Sensitivity analysis shows inverse relationship with HHV [26] [9] | ANN sensitivity analysis confirmed chemically intuitive trend of higher O reducing HHV [9] |

| Carbon (C) | Strong positive correlation with HHV [9] | Essential inclusion | Sensitivity analysis confirmed higher C increases HHV [9] |

| Hydrogen (H) | Strong positive correlation with HHV [9] | Essential inclusion | Sensitivity analysis confirmed higher H increases HHV [9] |

| Fixed Carbon (FC) | Strong positive correlation with HHV [9] | Essential inclusion | Sensitivity analysis confirmed higher FC increases HHV [9] |

The feature selection process has demonstrated that models utilizing only the most significant components can achieve comparable or superior accuracy to those incorporating all potential inputs. One study combining feature selection scenarios with machine learning tools established that excluding VM, N, and O provided more streamlined models without sacrificing predictive capability [26]. The resulting multilayer perceptron neural network achieved outstanding performance with an absolute average relative error of 2.75% and R² of 0.9500 in the learning stage [26].

Experimental Protocols for Feature Selection

Correlation-Based Feature Pre-Screening Protocol

Purpose: To identify and exclude features with minimal impact on HHV prior to model development.

Materials:

- Biomass dataset with proximate and ultimate analysis components alongside experimentally measured HHV values

- Statistical software (R, Python, or MATLAB)

Procedure:

- Compile a comprehensive dataset of biomass samples with complete proximate (moisture, ash, volatile matter, fixed carbon) and ultimate (C, H, N, S, O) analyses alongside experimentally determined HHV values [26] [9]

- Calculate Pearson's correlation coefficients between each compositional feature and the HHV [26]

- Perform multiple linear regression with all potential input features [26]

- Identify features with statistically insignificant coefficients (p > 0.05) and low correlation magnitudes (<0.2) as candidates for exclusion [26]

- Validate findings using multivariate adaptive regression splines (MARS) for non-linear relationship assessment [27]

Expected Outcomes: Identification of VM, N, and O as features with slight effect on HHV, justifying their exclusion from final models without significant accuracy loss [26].

ANN Model Development with Optimized Features

Purpose: To develop a high-accuracy neural network for HHV prediction using only the most significant input features.

Materials:

- Pre-processed biomass dataset with selected features

- Neural network framework (Python Keras/TensorFlow, MATLAB Deep Learning Toolbox)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

Network Architecture Selection:

Training Configuration:

Validation:

Expected Outcomes: Streamlined ANN model with reduced complexity and maintained high accuracy (R² > 0.94, AARE < 3%) comparable to models with full feature sets [26].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for feature selection and model optimization in HHV prediction:

Figure 1: Workflow for Feature Selection in HHV Prediction Modeling

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Analytical Tools for HHV Prediction Research

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Biomass grinding equipment | Particle size reduction to 1mm [9] | Standardized sample preparation for proximate analysis |

| Proximate Analysis | ASTM E711-compliant apparatus [9] | Determines moisture, ash, volatile matter, fixed carbon | Provides essential bulk property inputs |

| Ultimate Analysis | Elemental analyzer [9] | Quantifies C, H, N, S, O content | Supplies elemental composition data |

| Reference Measurement | Bomb calorimeter (e.g., IKA Werke C 5000) [9] | Experimentally determines reference HHV values | Ground truth for model training and validation |

| Data Processing | Statistical software (R, MATLAB, Python) | Implements correlation analysis and feature selection | Identifies significant predictors |

| Model Development | Neural network frameworks | Builds and trains ANN architectures | Creates predictive HHV models |

Strategic selection of input features significantly enhances the efficiency and performance of neural network models for HHV prediction. The evidence consistently indicates that excluding volatile matter, nitrogen, and oxygen content—features identified as having minimal impact on HHV—streamlines model architecture without compromising predictive accuracy. The provided protocols enable researchers to implement correlation-based feature pre-screening and develop optimized ANN models, ultimately advancing the state of HHV prediction research through more sophisticated input feature selection.

The Higher Heating Value (HHV) is a fundamental property defining the energy content of biomass and municipal solid waste (MSW), playing a critical role in the design and operation of thermochemical conversion systems like combustion, gasification, and pyrolysis [12] [10]. While the adiabatic oxygen bomb calorimeter is the traditional method for measuring HHV, the process is often time-consuming, expensive, and requires significant laboratory infrastructure [29] [10]. To circumvent these challenges, researchers have turned to computational methods, with artificial neural networks (ANNs) emerging as a powerful, data-driven tool for accurate HHV prediction [30] [16].

The selection of an appropriate neural network architecture is paramount for developing a robust predictive model. This application note provides a detailed comparative analysis of three key neural network architectures—Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Cascade Feedforward Neural Network (CFFNN), and Recurrent Networks, specifically the Elman Neural Network (ENN)—within the context of HHV prediction research. We summarize quantitative performance data, outline detailed experimental protocols, and provide visual workflow diagrams to serve as a practical guide for researchers and scientists in the bioenergy field.

Neural Network Architectures for HHV Prediction

Multilayer Perceptron (MLP)

The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) is a classical, feedforward artificial neural network known for its ability to model complex, non-linear relationships. It is highly suitable for tabular datasets, such as those derived from proximate and ultimate analyses of biomass [31] [16].

- Architecture and Application: An MLP consists of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. In HHV prediction, the input layer typically receives data from proximate analysis (fixed carbon, volatile matter, ash) and/or ultimate analysis (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur) [30] [32]. For instance, Olatunji et al. developed an MLP model to predict the HHV of municipal solid waste using moisture content, carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, and ash as inputs [32].

- Performance: MLP models have demonstrated outstanding performance. One study utilizing a feature selection approach reported that an MLP achieved an absolute average relative error of 2.75% during training and 3.12% during testing, with correlation coefficients (R²) of 0.9500 and 0.9418, respectively, outperforming other machine learning models [16]. Another comprehensive comparison of machine learning models found that ANN (typically MLP) was the most suitable for estimating biomass HHV, achieving an R² of 0.92 [30].

Cascade Feedforward Neural Network (CFFNN)

The Cascade Feedforward Neural Network (CFFNN) is a modified and often more powerful version of the standard MLP.

- Architecture and Application: The key differentiator of the CFFNN is the presence of direct connections from the input layer to the output layer and to every subsequent hidden layer [16]. This cascade structure allows the network to leverage both raw input features and progressively complex features constructed by the hidden layers, potentially capturing underlying relationships more effectively.

- Performance: In a study that compared several machine learning techniques for HHV estimation, the CFFNN was evaluated alongside MLP and other models. While the study concluded that the MLP demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy for the task, the CFFNN remains a viable and powerful architecture worthy of investigation for complex modeling tasks [16].

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) - Elman Neural Network (ENN)

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), such as the Elman Neural Network (ENN), are a class of neural networks designed to handle sequential data. Their internal memory (context units) makes them dynamic systems, which can be advantageous for capturing temporal dependencies or complex dynamic relationships in data [12] [31].

- Architecture and Application: The ENN includes a feedback loop from the hidden layer back to itself, creating a short-term memory. This allows the network to use information from previous inputs when processing the current input. While not strictly sequential, HHV prediction data can contain complex, inter-dependent relationships between compositional variables that a dynamic network like ENN can model. Aghel et al. (2023) successfully employed an ENN to predict biomass HHV from both proximate and ultimate analyses [12].

- Performance: The cited study found that a single hidden layer ENN with only four nodes, trained with the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, was highly accurate. The model predicted 532 experimental HHVs with a low mean absolute error of 0.67 and a mean square error of 0.96 [12]. This demonstrates that ENNs, though less commonly applied than MLPs, are a potent tool for HHV prediction.

The following diagram illustrates the structural differences and data flow between these three key neural network architectures.

Comparative Analysis of Architectural Performance

The table below provides a consolidated summary of the predictive performance of the different neural network architectures as reported in the literature for HHV prediction.

Table 1: Comparative performance of neural network architectures for HHV prediction

| Neural Network Architecture | Reported Performance Metrics | Dataset & Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | R²: 0.92 (Highest among compared models) | Biomass HHV from proximate analysis | [30] |

| Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) | AARD%: 2.75% (Learning), 3.12% (Testing)R²: 0.9500 (Learning), 0.9418 (Testing) | Biomass HHV with feature selection (532 samples) | [16] |

| Cascade Feedforward (CFFNN) | Evaluated but found to be less accurate than MLP in a comparative study | Biomass HHV estimation | [16] |

| Elman Neural Network (ENN) | MAE: 0.67, MSE: 0.96, R: 0.87566 (Whole data) | Biomass HHV from proximate & ultimate analysis (532 samples) | [12] |

| MLP (for MSW) | R: 0.986 (LM algorithm) | Municipal Solid Waste HHV (123 samples) | [32] |

AARD%: Absolute Average Relative Deviation Percent; MAE: Mean Absolute Error; MSE: Mean Squared Error; R: Correlation Coefficient; R²: Coefficient of Determination.

Experimental Protocol for HHV Prediction Modeling

This section outlines a generalized, step-by-step protocol for developing a neural network model to predict the Higher Heating Value.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Step 1: Data Collection. Compile a comprehensive database from peer-reviewed literature. For instance, the studies cited collected data ranging from 123 records for MSW [32] to 532 and 872 records for biomass [12] [30]. Ensure each record includes the ultimate and/or proximate analysis components as inputs and the corresponding experimentally measured HHV as the output.

- Step 2: Data Cleaning and Normalization. Remove any duplicate records and handle missing data. Normalize or standardize the input data to a common scale (e.g., 0 to 1 or -1 to 1) to ensure all input variables contribute equally to the model training and to improve convergence during training [30] [16].

- Step 3: Data Partitioning. Randomly split the entire dataset into three subsets:

Model Configuration and Training

- Step 4: Architecture Selection. Choose an architecture (MLP, CFFNN, ENN) based on the problem complexity and data structure. Start with a simple MLP as a baseline.

- Step 5: Topology Tuning. Determine the optimal number of hidden layers and neurons. This is often done iteratively. For example, one study found an ENN with a single hidden layer of 4 neurons to be optimal [12], while another used an MLP with 2 layers (10 neurons in the first) [30].

- Step 6: Algorithm and Activation Function Selection.

- Training Algorithm: The Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm is frequently reported as one of the best-performing algorithms for HHV prediction due to its fast convergence [12] [29] [32]. Bayesian Regularization (BR) is another top-performing algorithm, known for its effectiveness in preventing overfitting [29] [33].

- Activation Function: Sigmoidal functions (e.g.,

tansig,logsig) in hidden layers generally outperform linear functions for HHV prediction [29]. A linear function is typically used in the output layer for regression tasks.

Model Evaluation and Validation

- Step 7: Performance Assessment. Evaluate the trained model on the testing set using multiple statistical metrics to ensure a comprehensive assessment. Key metrics include:

- Coefficient of Determination (R²)

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

- Mean Squared Error (MSE) / Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

- Step 8: Model Validation. Compare the predictions of your model against experimental data not used in training and, if possible, against existing empirical correlations or models from the literature to establish its relative performance [16].

The following workflow provides a visual summary of this experimental protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents & Materials

In the context of computational HHV prediction, "research reagents" refer to the essential data inputs and software tools required to build and train the neural network models.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for HHV prediction modeling

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example in HHV Research |

|---|---|---|

| Ultimate Analysis Data | Serves as primary input features; measures elemental composition. | Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H), Oxygen (O), Nitrogen (N), Sulfur (S) content [12] [10] [16]. |

| Proximate Analysis Data | Serves as primary input features; measures bulk compositional properties. | Fixed Carbon (FC), Volatile Matter (VM), Ash content [12] [30] [16]. |

| Experimental HHV Database | Serves as the target output for supervised learning; used for model training and validation. | Experimentally measured HHV values compiled from literature (e.g., 532 biomass samples) [12] [16]. |

| Training Algorithms | The optimization method used to adjust neural network weights and biases. | Levenberg-Marquardt (LM), Bayesian Regularization (BR), Scaled Conjugate Gradient (SCG) [12] [29] [33]. |

| Activation Functions | Introduces non-linearity into the network, enabling it to learn complex patterns. | Sigmoidal functions (tansig, logsig) are highly effective for HHV prediction [29]. |